Abstract

Chitosan (CS) has emerged as a versatile biopolymer for designing drug delivery systems (DDS) in colorectal cancer (CRC) therapy due to its biocompatibility, mucoadhesive properties, and ability to be surface-functionalized. This scoping review systematically analyzed current experimental studies on CS-based DDS for CRC, comparing non-targeted formulations with ligand-modified systems to identify advances in targeting efficiency, drug release behavior, and biological outcomes. Among the twenty-five initially identified studies, divided into two categories, non-targeted CS-based DDSs and ligand-modified CS-DDSs, five fulfilled the inclusion criteria for ligand-functionalized systems. These incorporated targeting moieties, such as folic acid (FA), hyaluronic acid (HA), and galactose (Gal), to achieve receptor-mediated uptake via FRα, CD44, and ASGP receptors, respectively. Ligand modification consistently enhanced cellular uptake, reduced IC50 values, and improved tumor-selective cytotoxicity compared to non-targeted systems. However, in vivo validation remains scarce, with only one study confirming tumor accumulation in xenograft models. Moreover, no clinical trials currently assess CS-based nanocarriers for the treatment of CRC. Overall, CS represents a promising modular platform for targeted nanomedicine, but translational progress requires bridging preclinical success with comprehensive in vivo and clinical evaluation.

1. Introduction

Cancer is one of the leading causes of illness and death worldwide. Approximately 10 million new cases are estimated each year. Standard cancer treatment methods include chemotherapy, administered as neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, and radiotherapy, particularly when surgical removal of the tumor is impossible. However, chemotherapy and radiotherapy regimens are often ineffective due to their lack of specificity for cancer cells. The lack of specificity of conventional chemotherapeutic agents leads to the destruction of not only cancer cells but also healthy cells, consequently causing serious side effects. For this reason, new drug delivery systems (DDSs) for anticancer drugs are being intensively developed [1,2,3].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies. In its early stages, the disease causes no symptoms and is most often detected during screening tests, such as colonoscopy. The vast majority (approximately 90%) of CRC cases are adenocarcinomas of the large intestine. Chemotherapy and modern targeted molecular therapies are used in both the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings for CRC treatment. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy aims to reduce tumor burden, facilitating surgical resection and enhancing the likelihood of complete disease remission [4]. Adjuvant chemotherapy, in turn, is intended to improve patient survival by targeting and eliminating residual cancer cells that may remain after surgery [5].

Treatment for CRC includes chemotherapy (e.g., 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin (Oxa)) and targeted therapy (e.g., cetuximab (CTX), bevacizumab (BVC), encorafenib (ENC)), as well as immunotherapy (e.g., pembrolizumab (PEM), nivolumab (NIVO)) [6]. The choice of drug depends on the stage of the disease, tumor characteristics (e.g., genetic mutations), and the patient’s treatment history. Combination therapies, such as dual therapy with trifluridine/tipiracil (FTD/TPI), are also used to inhibit tumor growth. In recent years, intensive research has been conducted on new polymeric DDSs containing the previously mentioned active substances [7,8].

Given the limitations of conventional therapies, particularly their lack of specificity and associated side effects, increasing attention has been devoted to the development of advanced DDSs that can enhance treatment outcomes.

One way to improve the anticancer effects of drugs is to develop carriers that enable the delivery of effective drug concentrations to diseased sites without affecting normal cells. Examples of nanocarriers include chitosan (CS) nanoparticles (NPs) [9,10].

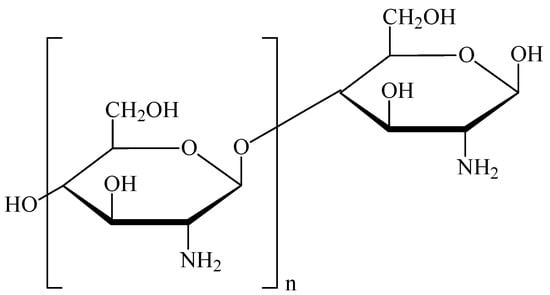

CS is a non-toxic, biodegradable polymer characterized by high biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and mucoadhesive as well as absorption-enhancing properties. Its chemical structure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of chitosan.

Although CS has numerous valuable advantages, it also has several limitations that affect its use in the delivery of anticancer drugs. These include low thermal stability [11,12] and ductility [13,14], poor solubility of CS above pH 6.5 [15,16], high hydrophilicity and swelling properties, which may lead to premature drug release and reduced structural stability. Moreover, CS exhibits considerable batch-to-batch variability due to differences in source material, degree of deacetylation, and purity, making reproducibility challenging. Its solubility and viscosity are also sensitive to pH and temperature, respectively, which can further impact formulation stability and processing [17,18,19]. Limitations in sterilization methods also present challenges. Yang et al. [20] demonstrated that steam sterilization significantly darkens CS powder, gamma irradiation causes strong depolymerization above 10 kGy, and ethylene oxide induces only minor changes in crystallinity and structure.

Despite the above limitations, many CS-based DDSs in the form of NPs, hydrogels, and polymeric hydrogel membranes have been developed for oral, ocular, nasal, pulmonary, buccal, periodontal, vaginal, dermal, and transdermal applications, as well as for wound healing, and for vaccine and gene delivery. Among these types of CS-based DDSs, NPs are the most promising formulations for pharmaceutical applications [21,22]. To date, CS-based DDSs have been confirmed to have excellent anticancer properties [23]. Among other things, they are effective against oral cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer, glioblastoma multiforme, liver cancer, and colon cancer, while also demonstrating satisfactory biocompatibility with typically developing cells and/or tissues. The resulting CS-based DDSs were evaluated for controlled release kinetics and system activation using pH changes [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37].

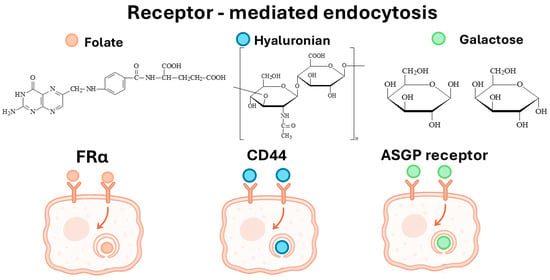

Importantly, these systems are also being developed as targeted therapies employing a range of common ligands, such as folic acid (FA), hyaluronic acid (HA), galactose (Gal), and antisense oligonucleotides, which enable receptor-specific interactions with the folate receptor (FR), CD44, and the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR).

This scoping review aims to explore recent literature on the pharmacological potential of CS-based DDSs for targeted chemotherapy in CRC.

2. Review Results

This scoping review identified and analyzed a total of 25 original research articles that met the inclusion criteria. These studies were grouped into two categories based on the design of the DDS: (1) CS-based DDS without active targeting ligands, and (2) ligand-modified CS-based DDS for selective drug delivery to CRC cells. This classification is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart showing the classification of the 25 included studies into non-targeted and ligand-modified CS-based DDSs.

2.1. Chitosan-Based DDS

The reviewed literature underscores the versatility of CS as a platform for CRC drug delivery. A total of 20 studies were included in this group, focusing on CS-based delivery systems such as NPs, microparticles (MPs), micelles, and nanogels loaded with various chemotherapeutic and bioactive agents. These included camptothecin (CPT), α-mangostin, irinotecan (CPT-11), curcumin (CUR), imatinib mesylate (IMT), and others. These systems employed diverse formulation strategies to enhance drug stability, enable colon-targeted delivery, and achieve sustained or stimuli-responsive release. Approaches included pH-sensitive coatings, enzyme-triggered mechanisms, magnetic targeting, and polymeric blends.

Most formulations exhibited controlled or pH-responsive release profiles. In vitro assays consistently demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity of CS-encapsulated drugs compared to their free forms, and several in vivo studies reported superior tumor suppression, reduced systemic toxicity, and prolonged survival in CRC models. The detailed characteristics of these systems are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of chitosan-based drug delivery systems for colorectal cancer treatment.

2.1.1. Routes of Administration and Physiological Barriers

Non-targeted CS-based DDS developed for CRC therapy utilize two principal administration routes: oral colon-targeted delivery and parenteral (intravenous) delivery. Each route encounters distinct physiological barriers. Oral systems must overcome gastric acidity, digestive enzymes, thick intestinal mucus, and first-pass metabolism combining pH-dependent matrices with mucoadhesive or enzyme-responsive components [58,59]. Intravenous formulations, in contrast, face rapid opsonization and clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), restricted vascular permeability, and the acidic, enzyme-rich tumor microenvironment (TME), which may hinder diffusion or destabilize carriers prematurely [60,61,62]. Effective CRC targeting therefore requires DDS able to withstand early degradation while enabling controlled drug release within colonic or tumoral compartments which are characterized by excessive ROS levels, distinct enzyme activity, and a higher pH compared to the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [63].

Oral CRC-Targeted Delivery

A substantial proportion of the included non-targeted systems were designed for oral, colon-targeted delivery. Across eight studies, a total of 15 distinct pH-responsive or colon-directed formulations were identified, incorporating polysaccharide matrices, CS derivatives, enteric coatings, and micro-/macroparticle platforms. These systems included CPT-loaded mPEG-CS-OA micelles [38], CS/Alg and TCS/Alg NPs with GP or L100 coatings [39], Yarrow-extract MPs/NPs [41], CUR-loaded CS/NaCMC-PLGA hybrids [45], SMV CS ES100 MPs [46], CS-NPs embedded in RS/P MPs [50], ALG-CS MPs/macroparticles [53] and CL-NBSCS systems [57].

Most of these formulations exhibited minimal drug release under gastric conditions and preferential release at colonic pH. For instance, SMV-CS-ES100 MPs prevented significant release until exposure to pH 7.4, achieving complete drug release within 24 h and confirmed colonic deposition via radiographic imaging [46]. Similarly, 5-FU CS-NPs embedded in RS/P MPs prolonged retention in the cecum and colon in vivo while reducing systemic exposure [50]. GP-crosslinked and L100-coated CS/Alg NPs maintained up to 15% release at pH 1.2 and reached 80% release at pH 7.4 within 8 h, demonstrating effective protection of α-mangostin during transit through the upper GIT [39].

Structural modifications of CS further amplified therapeutic efficacy. PEG-OA-modified CS micelles enhanced CPT pharmacokinetics and reduced tumor volume by 50% in murine CRC models [38]. Thiolated CS matrices promoted strong mucoadhesion and resulted in enhanced cytotoxicity compared to free etoposide (ETP) in HCT116 cells [49].

Multiple particulate formulations (both micro- and macroparticles) enabled precise colonic targeting, confirmed by radiographic imaging and biodistribution analyses. These systems ensured controlled systemic exposure and minimized accumulation in non-target tissues [46,50,53].

Collectively, these findings indicate that dual-layer protection, combining an enteric polymer with a CS matrix, provides substantially greater stability and colon-targeting precision than CS-NPs alone, which otherwise exhibit faster release kinetics and measurable systemic absorption.

Intravenous Delivery and Systemic Barriers

A total of 13 CS-based DDS across 12 studies were administered intravenously, primarily to enhance systemic circulation time, improve tumor accumulation through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, or integrate external or physicochemical triggers to achieve localized drug release within the TME. These systems included polymeric NPs such as IMT-loaded CS-NPs [42] and BEV-loaded CS NPs [47], hybrid CS-based nanocomposites, including CS-polyglutamic acid SN-38 systems co-administered with Bifidobacterium bifidum [43], surface-modified CS carriers [44,47], dual-ligand system (ETP-CS-LF-MLT NPs) [49], magnetic polyelectrolyte complexes (MPECs) for magnetically guided targeting [48], metal-CS hybrids [51], CS-stabilized nanostructures, such as CTB-loaded PS-CS-NPs [52] and EV-β-CD-HA-CS-Au nanoclusters (NCs) [56], enzyme- or pH/ultrasound-responsive nanocarriers [54] and charge-reversal Oxa-R-NGs [55].

Following intravenous injection, CS-based DDS must overcome several systemic barriers, including rapid opsonization, RES clearance, vascular endothelial permeability, and the acidic, enzyme-rich TME. Many included systems sought to address these limitations through PEGylation, lipid/CS hybridization, magnetic components, charge-reversal coatings, or enzyme-responsive linkages.

The integration of magnetic elements facilitated both targeted delivery and imaging capabilities. CPT-11-loaded MPECs and SN-38-loaded CS/polyglutamic acid (PGA) nanocomposites demonstrated enhanced tumor localization under magnetic guidance, resulting in higher tumor inhibition with minimal off-target toxicity [40,48].

Advanced nanogels incorporating charge-reversal properties and ultrasound responsiveness achieved 77% oxaliplatin (Oxa) release under tumor-mimicking pH conditions with low-intensity ultrasound, yielding the most pronounced tumor suppression in CT26 xenografts without systemic toxicity [55].

Metal-CS hybrid nanostructures, such as CS-Ag nanourchins (NUs) and CS-Au NCs, further enhanced intracellular uptake through redox-sensitive interactions, improving apoptotic activity while maintaining acceptable biocompatibility profiles [51,56]. BEV-CS-NPs prolonged the half-life of the drug and increased colonic tumor retention, with reduced liver distribution and minimal systemic toxicity in in vivo studies [47].

Safety assessments generally confirmed the high biocompatibility of unmodified CS carriers. However, some hybrid DDSs, such as EV-β-CD-HA-CS-AuNCs, exhibited marginal additive toxicity [56].

Overall, intravenous CS-based DDS demonstrated improved tumor targeting, controlled release within the TME, and enhanced therapeutic efficacy compared with free drugs. However, translation remains limited by the scarcity of immunocompetent animal models, minimal pharmacokinetic and immunogenicity characterization, and high variability in CS composition across studies.

2.1.2. Limitations, Evidence Quality, and Translational Barriers in Non-Targeted Chitosan-Based Drug Delivery Systems

Despite promising efficacy, the overall level of biological evidence supporting non-targeted CS-based DDS remains limited. A significant methodological limitation across studies was the predominant reliance on two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cell cultures (e.g., HT-29, HCT116), with limited exploration of three-dimensional (3D) models or metastatic CRC cell lines. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic and immunogenicity profiles remain underreported for most systems. Only a minority included in vivo validation, and the depth of pharmacokinetic or immunogenicity analyses was generally insufficient to support translational development. For example, capecitabine (CTB)-loaded CS NPs resulted in approximately 72% tumor reduction within 21 days in a DMH-induced CRC mouse model, while concurrently downregulating pro-angiogenic and inflammatory mediators [52], yet such promising outcomes remain isolated and insufficiently validated across independent studies.

Another concern relates to the credibility and robustness of reported efficacy data. In microbiome-assisted delivery, SN-38 CS-based systems co-administered with Bifidobacterium bifidum, achieved approximately 80% tumor suppression, doubling the efficacy observed without probiotic co-treatment [43]. However, such high inhibition rates were often reported from short-duration studies with unclear or unreported sample sizes, and lacking key methodological details. Consequently, these outcomes should be interpreted with caution until verified in larger, statistically powered in vivo experiments. In many cases, studies lacked appropriate comparator groups, such as standard chemotherapeutic regimens, making it difficult to determine the true clinical relevance of the observed improvements.

Furthermore, most in vivo studies relied on xenograft models in immunocompromised mice, which do not replicate the human immune response, stromal architecture, or cytokine profile influencing NPs clearance and tumor penetration. As a result, tumor accumulation and antitumor efficacy may be overestimated compared with immunocompetent hosts. Models lacking intact immune surveillance also fail to predict potential immunogenicity or long-term biosafety of CS-based DDS.

A substantial barrier is the heterogeneity of CS materials used across formulations. Formulations varied widely in molecular weight, degree of deacetylation, viscosity grade, type of cross-linking agents, density, and purification source, critically affect solubility, charge distribution, mucoadhesion, and cellular uptake. Due to inconsistent reporting, direct comparisons between formulations are limited and broader generalization is not possible.

Although non-targeted CS systems demonstrated several CRC-relevant functionalities, such as pH-responsive release, magnetic guidance, mucoadhesion, and microbiome-assisted delivery, the absence of standardized experimental methodologies and heterogeneous in vivo endpoints further undermine comparability and reproducibility.

Across diverse drug classes, including fluoropyrimidines, kinase inhibitors, topoisomerase inhibitors, and phytochemicals, CS-based carriers consistently improved antitumor activity through better drug retention, controlled release, and preferential tumor targeting in preclinical screening, but current evidence is insufficient to support translation. Their favorable safety profiles further support CS as a promising core material for next-generation CRC delivery platforms. Reported improvements in tumor inhibition or IC50 reduction must therefore be regarded as preliminary signals, not definitive therapeutic advantages.

Nonetheless, clinical translation is currently constrained by methodological inconsistencies, limited long-term toxicity data, and insufficient pharmacokinetic characterization. Addressing these gaps through standardized evaluation protocols and more rigorous in vivo testing is imperative to facilitate the advancement of CS-based systems toward clinical application.

2.2. Ligand-Modified CS-Based DDS

To improve the specificity of CS-DDSs, various ligands have been incorporated to enable receptor-mediated targeting of CRC cells. Among the most commonly used are FA, HA, Gal, and antisense oligonucleotides, which enable receptor-specific interactions with the FR, CD44, and the ASGP receptor (Figure 3). These ligand-functionalized systems consistently demonstrated enhanced cellular uptake, improved cytotoxicity, and stronger tumor localization compared to non-targeted CS carriers. Accordingly, IC50 values were significantly reduced, and therapeutic efficacy was improved both in vitro and, in one instance, in vivo.

Figure 3.

Receptor-mediated endocytosis in colorectal cancer cells via FRα, CD44, and ASGP receptors, showing ligand binding preferences and internalization pathways.

Although nine studies were initially identified, two review articles [64,65] were excluded as non-original research. Among the remaining seven experimental papers, two were removed during full-text screening due to the absence of active ligand-receptor targeting. Both employed passive targeting mechanisms, such as EPR or physicochemical selectivity, rather than specific molecular interactions. The gold nanocomposite system developed by Tan et al. [56] was reclassified under non-targeted DDSs owing to its passive physicochemical targeting. In contrast, the mesoporous silica NPs described by AbouAitah et al. [66] relied solely on EPR-driven tumor accumulation and were excluded from the comparative analysis.

The five ligand-modified CS-based DDS that met the inclusion criteria and demonstrated receptor-mediated active targeting are summarized in Table 2, along with their key design characteristics, release behavior, and biological outcomes.

Table 2.

Summary of ligand-modified chitosan-based delivery systems for targeted colorectal cancer therapy.

2.2.1. Folic Acid

FA is a targeting ligand composed of pteroic acid and glutamic acid connected via an amide bond [72]. It is one of the most extensively explored ligands in DDSs, providing an efficient strategy for the treatment and imaging of various cancers and inflammatory diseases. Due to its small molecular weight and high affinity for the FR, which is overexpressed in malignant cells but minimally expressed in healthy tissues, FA enables selective delivery of therapeutic and diagnostic agents to pathological cells without affecting normal ones [73].

Hamed et al. [74] reported the formation of metal complexes with the folate anions. Their results indicated that two FA complexes were formed in a 1:2 molar ratio (metal:FA), where FA acted as a bidentate ligand through both carboxyl groups. Polarized light studies confirmed that the FA complexes possessed a symmetric geometry. The authors concluded that transition metal-FA complexes are more suitable as therapeutic agents than free FA, owing to their higher absorption efficiency in biological systems.

Kola et al. [75] used NMR and spectroscopic studies to elucidate the interaction of FA with Cu(II) and other metal ions at varying concentrations. They observed that Cu2+ primarily coordinated with the pteridine ring (PTE) of FA, with minimal involvement of the glutamic acid moiety. This interaction was concentration-dependent: at lower FA concentrations, Cu2+ effectively bound to the PTE, whereas at higher concentrations, intermolecular interactions between FA molecules hindered copper coordination. Pronounced paramagnetic effects were detected on the PTE and p-aminobenzoic acid regions, with negligible influence on Glu signals. These findings provide new structural insight into FA-Cu2+ complexation, advancing the understanding of folate coordination behavior as a ligand in solution.

McMullon et al. [76] synthesized folate conjugates with stable lanthanide complexes, highlighting their potential application as luminescent and MRI-active probes for targeting FR-expressing cells.

Ragab et al. [77] developed binuclear Mn(II) complexes incorporating FA and co-ligands (Bpy/Phen), which exhibited significant cytotoxic activity against FR-positive cancer cell lines, particularly HCT116 colorectal cancer cells. The study also investigated the anticancer mechanisms, including wound-healing inhibition, cell cycle arrest, regulation of apoptotic proteins, and morphological alterations. These results lay the groundwork for future research exploring the therapeutic and diagnostic potential of FA-based metal chelates as targeting ligands.

Overall, FA conjugation significantly improved selective drug internalization into FRα-overexpressing CRC cells, reduced off-target toxicity, and enhanced cytotoxicity for agents such as 5-FU, IMT, and polyphenols.

Consistent with these findings, FA-conjugated CS NPs demonstrated superior internalization in FR-overexpressing colorectal cancer cells and significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity of 5-FU and RSV/FER combinations compared with non-targeted CS carriers [67,69].

Similarly, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNPs) functionalized with FA exhibited strong FR-mediated uptake and selective cytotoxicity toward HT-29 cells, confirming the effectiveness of FA as a targeting ligand for site-specific CRC therapy [68].

These findings collectively confirm the critical role of FR-mediated targeting in improving the selectivity and potency of CS-based DDS against CRC. To visualize the uptake behavior of folate-targeted CS-based DDSs, Figure 4 presents the FRα-mediated endocytic pathway responsible for their selective internalization into CRC cells.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of FRα-mediated internalization of folate-targeted CS-based DDSs. FA on the nanocarrier surface binds to overexpressed folate receptors on CRC cells, triggering receptor-mediated endocytosis and facilitating intracellular delivery of the encapsulated drug.

However, the therapeutic benefit of FA-based targeting strongly depends on the heterogeneous expression of folate receptors across CRC subtypes. Moreover, surface binding limits deeper tumor penetration, a phenomenon not addressed in current studies [78].

2.2.2. Hyaluronic Acid

HA is a naturally occurring linear polysaccharide belonging to the glycosaminoglycan family. It is a significant component of the ECM in connective, epithelial, and neural tissues of the human body, with over half of its total content found in the skin. Its chemical structure consists of repeating disaccharide units of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine linked by β-1,4 and β-1,3 glycosidic bonds [79,80].

HA exhibits distinctive physicochemical properties, including high hygroscopicity, viscoelasticity, biocompatibility, and non-immunogenicity. The biological role of HA depends strongly on its molecular weight: high-molecular-weight HA (HMW-HA, >1000 kDa) maintains hydration, lubrication, and tissue integrity, exerting anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects; conversely, low-molecular-weight HA (LMW-HA) fragments act as signaling molecules that activate inflammatory responses, promote angiogenesis, and facilitate cell migration during tissue repair [81,82].

In pharmaceutical applications, HA has been widely utilized as a carrier material due to its excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and specific interactions with cell surface receptors such as CD44. These characteristics make HA an attractive ligand and matrix component in the design of targeted DDSs [83,84,85].

Consistent with its biological affinity for the CD44 receptor, HA-based CS or PLGA nanocarriers exploited CD44 overexpression, a major driver of CRC stemness and metastasis, to achieve enhanced tumor uptake, robust anti-proliferative activity, and reduced cell migration compared with free apigenin or uncoated NPs [70]. In vivo imaging confirmed efficient tumor accumulation of HA-coated NPs with minimal off-target distribution, validating CD44-mediated active targeting as a powerful strategy for CRC therapy.

Nonetheless, CD44 expression varies widely between CRC stages [86,87]. This heterogeneity may limit uniform nanoparticle uptake across entire tumors. Additionally, high molecular weight HA may exhibit slower internalization rates, whereas low molecular weight HA may induce pro-inflammatory signaling—factors not systematically assessed in current studies [88].

2.2.3. Galactose

Gal is a monosaccharide found in lactose, glycoproteins, and glycolipids, and occurs in specific polysaccharides. In the human body, it can be metabolized to glucose. D-Gal has been extensively investigated as a targeting ligand in DDSs rather than as a primary carrier. Its main function is its specific affinity for ASGPR, which are abundantly expressed on hepatocytes and also present on specific cancer cells and macrophages. The covalent attachment of Gal to drug molecules or to NPs/liposomes enhances receptor-mediated uptake, thereby improving targeted delivery efficiency [89,90,91].

D’Souza et al. [92] provided a comprehensive overview of ligand-receptor strategies for hepatocyte-targeted delivery via ASGPR. They emphasized that sugar isomerism, Gal density and branching, spatial geometry, and glycosidic linkage patterns are key factors influencing receptor binding. Computational docking studies further support the design of synthetic multivalent Gal/GalNAc ligands tailored for improved receptor recognition and binding strength.

Ma et al. [93] developed a Gal-based fluorescent probe (Gal-MPA) to assess its binding affinity toward cancer cells. The probe exhibited markedly higher affinity for cancer cell lines (HepG2, MCF-7, A549) than for normal liver cells (L02), confirming the potential of Gal as a broad, tumor-targeting ligand for imaging and therapy.

Carbohydrate-mediated targeting was further demonstrated in galactosylated CS-functionalized MSNPs, which achieved selective cytotoxicity toward HT-29 colon cancer cells via ASGPR recognition, while exhibiting reduced toxicity toward normal fibroblasts [71]. These results support the application of Gal as an effective targeting ligand for site-specific CRC drug delivery.

However, ASGPR expression in CRC is heterogeneous within CRC lesions [94]. Therefore, while Gal enhances uptake in some CRC models, its broader applicability may be limited. Future studies should stratify CRC models by ASGPR status to clarify its true therapeutic value.

2.2.4. Summary and Challenges of Ligand-Modified CS-Based DDS

To provide a comparative overview of the main targeting strategies, Table 3 summarizes the ligands applied in CS-based DDS for CRC, their corresponding receptors, expression profiles, mechanisms of receptor-mediated uptake, and biological effects reported in the included studies [67,68,69,70,71]. The three principal ligands identified, FA, HA, and Gal, enable receptor-specific targeting of CRC-associated biomarkers, thereby improving drug localization and efficacy.

Table 3.

Summary of main ligands used in CS-based DDS for CRC targeting.

Overall, ligand modification of CS-based DDS consistently enhanced tumor-selective uptake, reduced IC50 values, and induced stronger apoptotic responses compared to non-targeted systems and free drugs. These findings underscore the versatility of CS as a modular platform for ligand conjugation and surface functionalization, enabling the exploitation of CRC-specific molecular signatures.

FA-conjugated CS NPs demonstrated superior internalization in FR-overexpressing CRC cells and significantly improved cytotoxicity of 5-FU and RSV/FER combinations compared with non-targeted systems [67,69]. Similarly, FA-functionalized CS-coated Zn–MOF nanocomposites exhibited pronounced FR-mediated uptake and vigorous proapoptotic and autophagic activity in HCT116 cells [68]. HA-based systems effectively targeted CD44, overexpressing CRC phenotypes, key drivers of stemness and metastasis, showing enhanced tumor accumulation, reduced migration, and selective cytotoxicity compared with free apigenin [70]. Carbohydrate-mediated targeting was also confirmed in galactosylated CS-functionalized MSNPs, which achieved selective cytotoxicity toward HT-29 cells through ASGPR recognition while sparing non-cancerous fibroblasts [71].

Across all ligand types, receptor heterogeneity, binding-site barrier effects, and variable ligand density present unresolved limitations that may diminish targeting consistency in vivo. None of the included studies systematically optimized ligand density or assessed saturation kinetics, which are crucial for translational performance.

Despite these promising in vitro results, the translational maturity of ligand-modified CS-based DDS remains limited. Most studies were restricted to 2D monolayer models, with only one demonstrating in vivo targeting efficiency. Data on pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and long-term biosafety are still lacking. Bridging the gap between enhanced molecular targeting and clinical relevance requires systematic evaluation in 3D tumor organoids and xenograft models, supported by in vivo validation to confirm whether receptor-mediated selectivity observed in vitro can translate into meaningful therapeutic benefit.

2.3. Comparative Analysis: Non-Targeted vs. Ligand-Modified CS-Based DDS

A comparative evaluation of the included studies revealed distinct performance differences between non-targeted and ligand-modified CS-based DDS in terms of cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, TME penetration, toxicity profile, and targeting efficiency.

These differences arise not only from the presence of a ligand but also from receptor density, ligand-receptor binding affinity, NPs surface charge, and steric accessibility of the targeting moiety, factors that were rarely controlled or compared across studies.

2.3.1. Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity

Ligand conjugation significantly enhanced receptor-mediated internalization efficiency compared to passive uptake mechanisms in non-targeted systems. FA- and HA-modified CS-DDS showed up to a 1.5–3-fold increase in cellular uptake in FRα+ and CD44+ colorectal cancer cells, respectively. Correspondingly, IC50 values were reduced by 40–70% relative to non-functionalized CS carriers, indicating enhanced intracellular drug accumulation and potency. In contrast, non-targeted CS NPs primarily relied on electrostatic interactions or EPR effects, yielding slower uptake kinetics and higher IC50 values.

2.3.2. Tumor Microenvironment Penetration

Ligand-modified DDSs exhibited superior penetration in TME-mimicking models, attributed to receptor-mediated internalization, enhanced mucoadhesion, and improved stability under acidic pH (6.5–6.8). FA and HA functionalization provided additional protection against premature drug release in neutral physiological conditions (pH 7.4) while enabling responsive release in mildly acidic or enzymatically active environments, consistent with CRC tumor pH gradients.

2.3.3. Toxicity Profile

Ligand-functionalized CS-based DDS generally exhibited lower systemic and off-target toxicity than free drugs and non-targeted systems. Enhanced tumor specificity reduced undesired cytotoxicity in normal fibroblast and epithelial cells. Moreover, the biocompatible nature of CS and its derivatives contributed to reduced gastrointestinal irritation and improved tolerability, as reported in both in vitro and limited in vivo assessments.

2.3.4. Summary

A comparative synthesis of non-targeted (Table 1) and ligand-modified (Table 2) CS-based DDS is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative performance of non-targeted and ligand-modified CS-based DDS for CRC therapy.

In summary, ligand modification significantly outperformed non-targeted CS-DDS in terms of cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and tumor-specific accumulation, while maintaining excellent biocompatibility. Among active targeting ligands, FA-based systems exhibited the most substantial receptor-mediated uptake and cytotoxic response, followed by HA- and Gal-functionalized formulations. HA-CD44 targeting proved particularly effective against metastatic and stem-like CRC phenotypes, whereas Gal-ASGPR interactions enhanced selectivity and minimized fibroblast toxicity.

Despite these promising findings, the in vivo efficacy of active targeting remains insufficiently validated. Only one study demonstrated successful tumor accumulation in xenograft models, while the remaining investigations were restricted to 2D monolayer or co-culture systems. The absence of comprehensive in vivo data, pharmacokinetic profiling, and long-term biosafety evaluation continues to hinder clinical translation. Future comparative studies integrating 3D tumor organoids and relevant animal models are required to bridge this preclinical gap and confirm whether the enhanced molecular specificity of ligand-modified CS-DDS translates into meaningful therapeutic benefit.

3. Clinical Perspective

Only a few clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov, accessed 11 November 2025) involving CS in cancer therapy have been registered to date, and none directly evaluate CS-based nanocarriers for CRC. The identified studies include: prostate cancer (NCT03712371), cancer-related breakthrough pain (NCT02591017), post-surgical applications in breast cancer (NCT02967146), lung cancer prognosis (NCT04218188), and sellar reconstruction in skull base surgery (NCT03280849). Additional studies investigated the use of CS in laser-assisted immunotherapy for advanced breast cancer (NCT03202446), intratumoral injection following thermal ablation in advanced solid tumors (NCT03993678), and topical or local treatments for oral lesions, including oral lichen planus (NCT07114016, NCT06135259) and oral squamous cell carcinoma (NCT05893888). Collectively, these trials primarily focus on supportive, surgical, or topical therapeutic applications rather than systemic anticancer drug delivery, underscoring the lack of translational or clinical evaluation of CS-based DDS in oncology.

4. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [95]. The objective was to systematically map the research landscape concerning CS-based DDS for chemotherapy in CRC, focusing on both general DDS applications and ligand-mediated targeted systems.

4.1. Search Strategy

Two complementary literature search strategies were employed to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant studies. The first strategy focused on identifying research related to general CS-based DDSs for CRC treatment, without emphasizing active targeting. The second strategy targeted studies involving CS-based DDSs modified with active targeting ligands such as folic acid, hyaluronic acid, peptides, antibodies, or other tumor-specific molecules.

A two-stage approach was applied. First, a broad MeSH-based query retrieved all potentially relevant articles (Section 1 search string), ensuring sensitivity and a full landscape of available evidence. Second, a more specific Title/Abstract keyword search focused on ligand-based active targeting strategies (Section 2 search string), was conducted enhancing specificity and yielding the final screening pool.

Both searches were conducted in PubMed and limited to original research articles written in English, published between January 2020 and June 2025. This timeframe was selected to capture the most recent trends in CS-based DDSs for CRC. Reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and non-CRC studies were excluded.

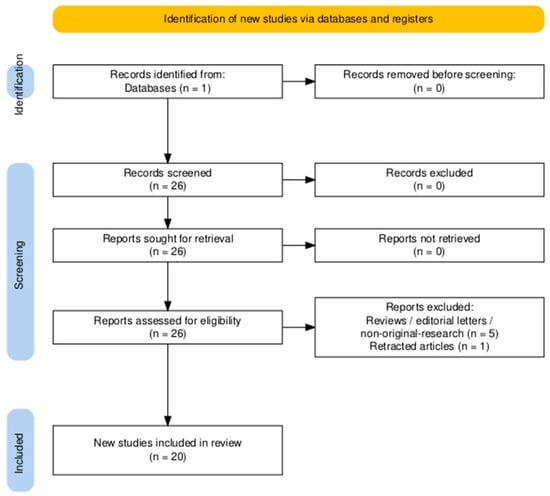

Full Boolean expressions are available in the Supporting Information (Table S1), with corresponding search trees illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram detailing the identification, screening and inclusion stages for studies investigating chitosan-based drug delivery systems for colorectal cancer. Diagram generated using the PRISMA2020 R package and the PRISMA Shiny app [96].

Figure 6.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening, and inclusion process for ligand-modified chitosan-based drug delivery systems for colorectal cancer. Diagram generated using the PRISMA2020 R package and the PRISMA Shiny app [96].

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, studies had to meet the following eligibility criteria: (1) they had to report on a CS-based DDS developed for the treatment of CRC, (2) include a chemotherapeutic payload, and (3) present experimental in vitro and/or in vivo evaluation of biological activity.

Studies were excluded if they were not focused on CRC, did not involve CS in the DDS composition, lacked a chemotherapeutic agent, or did not present any biological results. Additionally, review articles, book chapters, and papers written in languages other than English were excluded.

4.3. Data Screening and Extraction

After removing duplicates, all identified records were screened in a two-stage process. First, titles and abstracts were reviewed to eliminate irrelevant studies. Then, the full texts of potentially eligible articles were assessed. Four independent reviewers conducted the screening and data extraction, while discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a fifth reviewer.

Extracted data included the type and composition of the DDS, the presence and type of ligands used (if applicable), the chemotherapeutic agent, drug release methodology and outcomes, cytotoxicity results with specific cell lines, animal models used in vivo, and the biological effects observed.

The studies were then categorized into two thematic groups. The first group included CS-based DDS for CRC without necessarily incorporating targeting ligands and is discussed in Section 2.2 and summarized in Table 1. The second group comprised ligand-modified DDS designed for targeted therapy and is presented in Section 2.3, with corresponding data in Table 2.

5. Conclusions

Despite remarkable in vitro and preclinical progress, the clinical translation of CS-based DDSs, particularly those employing ligand-mediated targeting, still remains limited. None of the ligand-modified CS-based nanocarriers identified in this review has advanced beyond preclinical testing, underscoring the persistent challenges that impede transition from laboratory to clinical application.

The development of novel CS-based therapeutic systems containing anticancer drugs with effective therapeutic potential is a future challenge for modern oncology. By enhancing drug stability, bioavailability, and tumor selectivity, CS NPs in oncology present a significant opportunity to overcome the shortcomings of standard therapies, enabling early and effective treatment. Further intensification of scientific and development work in this area is expected in the coming years.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/md23120467/s1, Table S1: Boolean search expressions used for the literature search (January 2020–June 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.P.; methodology, U.P., formal analysis, U.P., E.K. and M.O.; investigation, U.P., J.S., A.N., E.K. and M.O.; data curation, U.P., J.S. and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, U.P., E.K., M.O. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, U.P. and M.S.; visualization, U.P. and M.S.; supervision, U.P.; project administration, U.P.; funding acquisition, U.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in whole or in part by National Science Centre, Poland [2022/47/D/NZ7/01403]. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| AgNUs | Silver Nanourchins |

| ALG | Alginate |

| AO/EB | Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide |

| API | Apigenin |

| ASGPR | Asialoglycoprotein Receptor |

| AUC | Area Under The Curve |

| AuNCs | Gold Nanoclusters |

| BVC | Bevacizumab |

| CD31 | Cluster of Differentiation 31 |

| CD44 | Cluster of Differentiation 44 |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| CL | Cyqualone |

| Cl | Clearance |

| COL | Colchicine |

| CPT | Camptothecin |

| CPT-11 | Irinotecan |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| CRT | Calreticulin |

| CS | Chitosan |

| CTB | Capecitabine |

| CTX | Cetuximab |

| CUR | Curcumin |

| DAPI | 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DCQAs | Dicaffeoylquinic Acids |

| DCS | Deacetylated Chitosan |

| DDSs | Drug Delivery Systems |

| DiR | 1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide |

| DMH | 1,2-Dimethylhydrazine |

| ENC | Encorafenib |

| EPR | Enhanced Permeability and Retention |

| ES100 | Eudragit S100 |

| ETP | Etoposide |

| EV | Everolimus |

| FA | Folic Acid |

| FER | Ferulic Acid |

| FRα | Folate Receptor-α |

| FTD/TPI | Trifluridine/Tipiracil |

| Gal | Galactose |

| GCS | Galactosylated Chitosan |

| GEL | Gelatin |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GP | Genipin |

| HA | Hyaluronic Acid |

| HCT-116 | Human Colorectal Carcinoma Cell Line |

| HCTO | Human Colon Tumor Organoids |

| HET CAM | Hen’s Egg Test On Chorioallantoic Membrane |

| HMGB1 | High-Mobility Group Protein B1 |

| HMW-HA | High Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid |

| HT-29 | Human Colorectal Adenocarcinoma |

| HUVEC | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial |

| ICG | Indocyanine Green |

| IMT | Imatinib Mesylate |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| Kp | Partition Coefficient |

| L100 | Eudragit L100 |

| LF | Lactoferrin |

| LIU | Low-intensity Ultrasound |

| LMW-HA | Low Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid |

| LNA | Locked Nucleic Acid |

| M | miRNA |

| MCTS | MultiCellular Tumor Spheroid |

| MFI | Mean Fluorescence Intensity |

| MLT | Melatonin |

| MMP | Mitochondrial Membrane Potential |

| MPECs | Magnetic Polyelectrolite complexes |

| MPs | Microparticles |

| MRT | Mean Residence Time |

| MSNPs | Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NaCMC | Sodium Carboxymethylcellulose |

| NBSCS | N-benzyl-N,O-succinyl Chitosan |

| NCs | Nanoclusters |

| NIR | Near-infrared Radiation |

| NIVO | Nivolumab |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| OA | Oleic Acid |

| Oxa | Oxaliplatin |

| P | Pectin |

| PA | Phytic Acid |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| PECs | Polyelectrolite complexes |

| PEG | Polyethylene Glycol |

| PEM | Pembrolizumab |

| PGA | Polyglutamic Acid |

| PLGA | Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PNPs | Polymeric Nanoparticles |

| PS | Potato Starch |

| PTE | Pteridine Ring |

| RES | Reticuloendothelial System |

| R-NG | Charge Reversible Nanogel |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RS | Retrograded Starch |

| RSV | Resveratrol |

| RTCA | Real-Time Cell Analysis |

| SCF | Simulated Colonic Fluid |

| SGF | Simulated Gastric Fluid |

| SIF | Simulated Intestinal Fluid |

| SLNs | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles |

| SMV | Simvastatin |

| t1/2 | Half-life |

| TCS | Thiolated Chitosan |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TPGS | D-α-Tocopheryl Polyethylene Glycol 1000 Succinate |

| TUNEL | Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling |

| US | Ultrasound |

| Vd | Volume Distribution |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| Zn-NMOF | Zinc-based Nanoscale Metal–Organic Framework |

| β-CD | Beta-Cyclodextrin |

References

- Tsai, C.-C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Chang, H.-H.; Chang, P.T.S.; Chang, C.-H.; Chu, T.Y.; Hsu, P.-C.; Kuo, C.-Y. Diagnostics and Therapy for Malignant Tumors. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; Gatenby, R.A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Pienta, K.J. Updating the definition of cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2023, 21, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masucci, M.; Karlsson, C.; Blomqvist, L.; Ernberg, I. Bridging the divide: A review on the implementation of personalized cancer medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.G.; Nilsson, P.J.; Shogan, B.D.; Harji, D.; Gambacorta, M.A.; Romano, A.; Brandl, A.; Qvortrup, C. Neoadjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer: Comprehensive review. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpin, B.M.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Mamon, H.J.; Mayer, R.J. Adjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2007, 57, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Gautam, V.; Sandhu, A.; Rawat, K.; Sharma, A.; Saha, L. Current and emerging therapeutic approaches for colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, E.; Tanis, P.J.; Vleugels, J.; Kasi, P.M.; Wallace, M. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 2019, 394, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkomy, M.H.; Ali, A.A.; Eid, H.M. Chitosan on the surface of nanoparticles for enhanced drug delivery: A comprehensive review. J. Control. Release 2022, 351, 923–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Aleahmad, M. Chitosan nanoparticles, as biological macromolecule-based drug delivery systems to improve the healing potential of artificial neural guidance channels: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 201, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, C.d.T.; Giacometti, J.A.; Job, A.E.; Ferreira, F.C.; Fonseca, J.L.C.; Pereira, M.R. Thermal analysis of chitosan based networks. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 62, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, J.; Kaczmarek, H. Thermal treatment of chitosan in various conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhe, P.; Kannan, R.M. Improvement in ductility of chitosan through blending and copolymerization with PEG: FTIR investigation of molecular interactions. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahba, M.I. Enhancement of the mechanical properties of chitosan. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2020, 31, 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Li, H.; Xiao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Du, Y. Water-solubility of chitosan and its antimicrobial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 63, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogias, I.A.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Williams, A.C. Exploring the factors affecting the solubility of chitosan in water. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010, 211, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhazi, M.; Desbrieres, J.; Tolaimate, A.; Alagui, A.; Vottero, P. Investigation of different natural sources of chitin: Influence of the source and deacetylation process on the physicochemical characteristics of chitosan. Polym. Int. 2000, 49, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E.; Winnicka, K. Stability of chitosan—A challenge for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 1819–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, C.; Bengoechea, C.; Carrillo, F.; Calero, N. Effect of deacetylation degree and molecular weight on surface properties of chitosan obtained from biowastes. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.M.; Zhao, Y.H.; Liu, X.H.; Ding, F.; Gu, X.S. The effect of different sterilization procedures on chitosan dried powder. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 104, 1968–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Vimal, A.; Kumar, A. Why Chitosan? From properties to perspective of mucosal drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, E. Progresses in targeted drug delivery systems using chitosan nanoparticles in cancer therapy: A mini-review. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 58, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, U.; Orzechowska, K. Advances in chitosan-based smart hydrogels for colorectal cancer treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousian, B.; Ghasemi, M.H.; Khosravi, A.R. Targeted chitosan nanoparticles embedded into graphene oxide functionalized with caffeic acid as a potential drug delivery system: New insight into cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, G.; Miao, Q.; Tan, W.; Li, Q.; Guo, Z. New synthetic adriamycin-incorporated chitosan nanoparticles with enhanced antioxidant, antitumor activities and pH-sensitive drug release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, J.; Tang, X.; Huang, K.; Chen, L. Polyelectrolyte three layer nanoparticles of chitosan/dextran sulfate/chitosan for dual drug delivery. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 190, 110925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajalakshmi, R.; Sivaselvam, S.; Ponpandian, N. Chitosan grafted Fe-doped WO3 decorated with gold nanoparticles for stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems. Mater. Lett. 2021, 304, 130664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, R.; Abbas, S.R. Evaluation of amygdalin-loaded alginate-chitosan nanoparticles as biocompatible drug delivery carriers for anticancerous efficacy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Bremner, D.H.; Ye, Y.; Lou, J.; Niu, S.; Zhu, L.-M. A dual-prodrug nanoparticle based on chitosan oligosaccharide for enhanced tumor-targeted drug delivery. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 619, 126512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Cardoso, V.M.; de Brito, N.A.P.; Ferreira, N.N.; Boni, F.I.; Ferreira, L.M.B.; Carvalho, S.G.; Gremião, M.P.D. Design of mucoadhesive gellan gum and chitosan nanoparticles intended for colon-specific delivery of peptide drugs. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 628, 127321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, B.N.; Pereira, M.N.; Bravo, M.d.O.; Cunha-Filho, M.; Saldanha-Araújo, F.; Gratieri, T.; Gelfuso, G.M. Chitosan nanoparticles loading oxaliplatin as a mucoadhesive topical treatment of oral tumors: Iontophoresis further enhances drug delivery ex vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 1265–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Tan, Z.; Zheng, D.; Qiu, X. pH-responsive magnetic Fe3O4/carboxymethyl chitosan/aminated lignosulfonate nanoparticles with uniform size for targeted drug loading. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohiya, G.; Katti, D.S. Carboxylated chitosan-mediated improved efficacy of mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based targeted drug delivery system for breast cancer therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-J.; Wang, T.-H.; Chou, Y.-H.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Hsu, T.-C.; Yow, J.-L.; Tzang, B.-S.; Chiang, W.-H. Hybrid PEGylated chitosan/PLGA nanoparticles designed as pH-responsive vehicles to promote intracellular drug delivery and cancer chemotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 210, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, S.; Meena, K.; Sharmili, S.A.; Govindarajan, M.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Alobaidi, A.S.; Alanzi, K.F.; Vaseeharan, B. Ulvan loaded graphene oxide nanoparticle fabricated with chitosan and d-mannose for targeted anticancer drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 65, 102760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandile, N.G.; Mohamed, H.M.; Nasr, A.S. Novel hydrazinocurcumin derivative loaded chitosan, ZnO, and Au nanoparticles formulations for drug release and cell cytotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 158, 1216–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idoudi, S.; Hijji, Y.; Bedhiafi, T.; Korashy, H.M.; Uddin, S.; Merhi, M.; Dermime, S.; Billa, N. A novel approach of encapsulating curcumin and succinylated derivative in mannosylated-chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 297, 120034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Castro, F.; Resende, C.; Lucio, M.; Schwartz Jr, S.; Sarmento, B. Oral delivery of camptothecin-loaded multifunctional chitosan-based micelles is effective in reduce colorectal cancer. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samprasit, W.; Opanasopit, P.; Chamsai, B. Mucoadhesive chitosan and thiolated chitosan nanoparticles containing alpha mangostin for possible Colon-targeted delivery. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2021, 26, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, R.; Yang, G. Superparamagnetic chitosan nanocomplexes for colorectal tumor-targeted delivery of irinotecan. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 584, 119394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siles-Sánchez, M.d.l.N.; Fernández-Jalao, I.; Jaime De Pablo, L.; Santoyo, S. Design of chitosan colon delivery micro/nano particles for an Achillea millefolium extract with antiproliferative activity against colorectal cancer cells. Drug Deliv. 2024, 31, 2372285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan-based polymeric nanoparticles of Imatinib for colorectal cancer targeting application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Fu, K.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Ji, Y.; Dai, Y.; Yang, G. Chitosan nanomedicines-engineered bifidobacteria complexes for effective colorectal tumor-targeted delivery of SN-38. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 659, 124283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhirud, D.; Bhattacharya, S.; Raval, H.; Sangave, P.C.; Gupta, G.L.; Paraskar, G.; Jha, M.; Sharma, S.; Belemkar, S.; Kumar, D. Chitosan nanoparticles of imatinib mesylate coated with TPGS for the treatment of colon cancer: In-vivo & in-vitro studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122935. [Google Scholar]

- Inphonlek, S.; Sunintaboon, P.; Léonard, M.; Durand, A. Chitosan/carboxymethylcellulose-stabilized poly (lactide-co-glycolide) particles as bio-based drug delivery carriers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 242, 116417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhakamy, N.A.; Fahmy, U.A.; Ahmed, O.A.; Caruso, G.; Caraci, F.; Asfour, H.Z.; Bakhrebah, M.A.; N. Alomary, M.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Okbazghi, S.Z. Chitosan coated microparticles enhance simvastatin colon targeting and pro-apoptotic activity. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uner, B.; Akyildiz, E.O.; Kolci, K.; Eskiocak, O.; Reis, R.; Beyaz, S. Nanoparticle formulations for intracellular delivery in colorectal cancer therapy. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, W.; Xu, S.; Yang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Yang, G. A biocompatible superparamagnetic chitosan-based nanoplatform enabling targeted SN-38 delivery for colorectal cancer therapy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 274, 118641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raval, H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bhirud, D.; Sangave, P.C.; Gupta, G.L.; Paraskar, G.; Jha, M.; Sharma, S.; Belemkar, S.; Kumar, D. Fabrication of lactoferrin-chitosan-etoposide nanoparticles with melatonin via carbodiimide coupling: In-vitro & in-vivo evaluation for colon cancer. J. Control. Release 2025, 377, 810–841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, A.M.; Meneguin, A.B.; Akhter, D.T.; Fletcher, N.; Houston, Z.H.; Bell, C.; Thurecht, K.J.; Gremião, M.P.D. Understanding the role of colon-specific microparticles based on retrograded starch/pectin in the delivery of chitosan nanoparticles along the gastrointestinal tract. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 158, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Joshi, A.; Beldar, V.; Mishra, A.; Sharma, S.; Khan, R.; Khan, M.R. Chitosan-Coated Silver Nanourchins for Imatinib Mesylate Delivery: Biophysical Characterization, In-Silico Profiling, and Anti-Colon Cancer Efficacy. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 1983–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Page, A.; Shinde, P. Capecitabine loaded potato starch-chitosan nanoparticles: A novel approach for targeted therapy and improved outcomes in aggressive colon cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 200, 114328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wezgowiec, J.; Tsirigotis-Maniecka, M.; Saczko, J.; Wieckiewicz, M.; Wilk, K.A. Microparticles vs. macroparticles as curcumin delivery vehicles: Structural studies and cytotoxic effect in human adenocarcinoma cell line (LoVo). Molecules 2021, 26, 6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciro, Y.; Rojas, J.; Di Virgilio, A.L.; Alhajj, M.J.; Carabali, G.A.; Salamanca, C.H. Production, physicochemical characterization, and anticancer activity of methotrexate-loaded phytic acid-chitosan nanoparticles on HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 243, 116436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, R.; Zhou, J.; Yang, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Tan, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, G.; Yu, J. Ultrasound-triggered nanogel boosts chemotherapy and immunomodulation in colorectal cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 17, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.F.; Chia, L.Y.; Maki, M.A.A.; Cheah, S.-C.; In, L.L.A.; Kumar, P.V. Gold nanocomposites in colorectal cancer therapy: Characterization, selective cytotoxicity, and migration inhibition. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 8975–9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripetthong, S.; Eze, F.N.; Sajomsang, W.; Ovatlarnporn, C. Development of pH-Responsive N-benzyl-N-O-succinyl Chitosan Micelles Loaded with a Curcumin Analog (Cyqualone) for Treatment of Colon Cancer. Molecules 2023, 28, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, A.L.; Mrsny, R.J. Transcellular uptake mechanisms of the intestinal epithelial barrier Part one. Pharm. Sci. Technol. Today 1999, 2, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R.; Vikal, A.; Patel, P.; Narang, R.K.; Kurmi, B.D. Enhancing oral drug absorption: Overcoming physiological and pharmaceutical barriers for improved bioavailability. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzi, S.; Hebda, J.K.; Gavard, J. Vascular permeability and drug delivery in cancers. Front. Oncol. 2013, 3, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilsed, C.M.; Fisher, S.A.; Nowak, A.K.; Lake, R.A.; Lesterhuis, W.J. Cancer chemotherapy: Insights into cellular and tumor microenvironmental mechanisms of action. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 960317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, U.; Tsoi, J.; Singh, P.; Banerjee, A.; Sobczak, M. 3D Bioprinting and Artificial Intelligence for Tumor Microenvironment Modeling: A Scoping Review of Models, Methods, and Integration Pathways. Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 5801–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Azad, M.; Fathi, M.; Cho, W.C.; Barzegari, A.; Dadashi, H.; Dadashpour, M.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R. Recent advances in targeted drug delivery systems for resistant colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhirud, D.; Bhattacharya, S.; Prajapati, B.G. Bioengineered carbohydrate polymers for colon-specific drug release: Current trends and future prospects. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2024, 112, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Joshi, K.; Singh, S. A shift in focus towards precision oncology, driven by revolutionary nanodiagnostics; revealing mysterious pathways in colorectal carcinogenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 16157–16177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouAitah, K.; Hassan, H.A.; Swiderska-Sroda, A.; Gohar, L.; Shaker, O.G.; Wojnarowicz, J.; Opalinska, A.; Smalc-Koziorowska, J.; Gierlotka, S.; Lojkowski, W. Targeted nano-drug delivery of colchicine against colon cancer cells by means of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Cancers 2020, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Azad, A.K.; Nawaz, A.; Shah, K.U.; Iqbal, M.; Albadrani, G.M.; Al-Joufi, F.A.; Sayed, A.A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. 5-fluorouracil-loaded folic-acid-fabricated chitosan nanoparticles for site-targeted drug delivery cargo. Polymers 2022, 14, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokri, N.; Sepehri, Z.; Faninam, F.; Khaleghi, S.; Kazemi, N.M.; Hashemi, M. Chitosan-coated Zn-metal-organic framework nanocomposites for effective targeted delivery of LNA-antisense miR-224 to colon tumor: In vitro studies. Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S.; Thangam, R.; Mary, S.A.; Kannan, P.R.; Arun, G.; Madhan, B. Targeted delivery and apoptosis induction of trans-resveratrol-ferulic acid loaded chitosan coated folic acid conjugate solid lipid nanoparticles in colon cancer cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 231, 115682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, B.; Peng, H. HA-coated PLGA nanoparticles loaded with apigenin for colon cancer with high expression of CD44. Molecules 2023, 28, 7565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Pang, J.; Pan, W. Galactosylated chitosan-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for efficient colon cancer cell-targeted drug delivery. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 181027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Wahed, M.; Refat, M.; El-Megharbel, S. Synthesis, spectroscopic and thermal characterization of some transition metal complexes of folic acid. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2008, 70, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgenbrink, A.R.; Low, P.S. Folate receptor-mediated drug targeting: From therapeutics to diagnostics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 2135–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, E.; Attia, M.; Bassiouny, K. Synthesis, spectroscopic and thermal characterization of copper (II) and iron (III) complexes of folic acid and their absorption efficiency in the blood. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2009, 2009, 979680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kola, A.; Valensin, D. NMR-Based Structural Insights on Folic Acid and Its Interactions with Copper (II) Ions. Inorganics 2024, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullon, G.T.; Ezdoglian, A.; Booth, A.C.; Jimenez-Royo, P.; Murphy, P.S.; Jansen, G.; van der Laken, C.J.; Faulkner, S. Synthesis and characterization of folic acid-conjugated terbium complexes as luminescent probes for targeting folate receptor-expressing cells. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 14062–14076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragab, M.S.; Soliman, M.H.; Sharaky, M.M.; Saad, A.; Shehata, M.R.; Shoukry, M.M.; Ragheb, M.A. Folate-based binuclear Mn (II) chelates with 2, 2′-bipyridine/1, 10-phenanthroline as targeted anticancer agents for colon cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Low, P.S. Folate-targeted therapies for cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 6811–6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaconisi, G.N.; Lunetti, P.; Gallo, N.; Cappello, A.R.; Fiermonte, G.; Dolce, V.; Capobianco, L. Hyaluronic acid: A powerful biomolecule with wide-ranging applications—A comprehensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, A.; Nunes, C.; Reis, S. Hyaluronic acid: A key ingredient in the therapy of inflammation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, A.; Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Sheng, Y.; Cao, C.; Zhang, K. Advances in hyaluronic acid for biomedical applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 910290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snetkov, P.; Zakharova, K.; Morozkina, S.; Olekhnovich, R.; Uspenskaya, M. Hyaluronic acid: The influence of molecular weight on structural, physical, physico-chemical, and degradable properties of biopolymer. Polymers 2020, 12, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, K.N.; Yap, W.H.; Lim, C.L.H.; Goh, B.H.; Lai, Z.W. Hyaluronic acid-mediated drug delivery system targeting for inflammatory skin diseases: A mini review. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Sun, T.; Yang, L. Hyaluronic acid-based nano drug delivery systems for breast cancer treatment: Recent advances. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 990145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Mansouri, K.; Valipour, E.; Abam, F.; Jaymand, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Dokaneheifard, S.; Mohammadi, M. Hyaluronic acid-based drug nanocarriers as a novel drug delivery system for cancer chemotherapy: A systematic review. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 29, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.W.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; Cho, S.H.; Joo, J.K. Expression of standard CD44 in human colorectal carcinoma: Association with prognosis. Pathol. Int. 2009, 59, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, A.; Xue, C.; Gu, Z.; Wang, K.; Zong, S. The prognostic and clinical value of CD44 in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayahin, J.E.; Buhrman, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Koh, T.J.; Gemeinhart, R.A. High and low molecular weight hyaluronic acid differentially influence macrophage activation. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battisegola, C.; Billi, C.; Molaro, M.C.; Schiano, M.E.; Nieddu, M.; Failla, M.; Marini, E.; Albrizio, S.; Sodano, F.; Rimoli, M.G. Galactose: A versatile vector unveiling the potentials in drug delivery, diagnostics, and theranostics. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Namazi, H.; Salehi, R. Dual anticancer drug delivery of D-galactose-functionalized stimuli-responsive nanogels for targeted therapy of the liver hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 167, 111061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Porterfield, J.E.; An, H.-T.; Jimenez, A.S.; Lee, S.; Kannan, S.; Sharma, A.; Kannan, R.M. Rationally designed galactose dendrimer for hepatocyte-specific targeting and intracellular drug delivery for the treatment of liver disorders. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 3574–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, A.A.; Devarajan, P.V. Asialoglycoprotein receptor mediated hepatocyte targeting—Strategies and applications. J. Control. Release 2015, 203, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, H.; Su, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.; Fida, G.; Cui, S.; Zhao, J.; Gu, Y. Galactose as broad ligand for multiple tumor imaging and therapy. J. Cancer 2015, 6, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, S.; Parkhideh, A.; Bhattacharya, P.K.; Farach-Carson, M.C.; Harrington, D.A. Beyond colonoscopy: Exploring new cell surface biomarkers for detection of early, heterogenous colorectal lesions. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 657701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).