Abstract

Lectins are proteins with a remarkably high affinity and specificity for carbohydrates. Many organisms naturally produce them, including animals, plants, fungi, protists, bacteria, archaea, and viruses. The present report focuses on lectins produced by marine or freshwater organisms, in particular algae and cyanobacteria. We explore their structure, function, classification, and antimicrobial properties. Furthermore, we look at the expression of lectins in heterologous systems and the current research on the preclinical and clinical evaluation of these fascinating molecules. The further development of these molecules might positively impact human health, particularly the prevention or treatment of diseases caused by pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus, influenza, and severe acute respiratory coronaviruses, among others.

1. Introduction

1.1. Lectins, Their Structure, Function, and Carbohydrate-Binding Specificity

The Latin root for “lectin” means to choose or select, an appropriate meaning given that lectins are proteins that “choose”: to bind carbohydrates in glycolipids or glycoproteins and that the interaction of lectins with carbohydrates can be very selective and as specific as the antigen/antibody interactions. In addition to binding to oligosaccharides, they might also bind to monosaccharides, although with less affinity. Lectins are ubiquitous and can be produced by different organisms, including animals, plants, fungi, protists, and microorganisms such as bacteria, archaea, or viruses. There are different types of lectins shown in Table 1 that have been classified based on structural and functional similarities. The different types of lectins include C-type lectins (selectins, collectins, and endocytic lectins), S-type lectins (galectins), siglecs (sialic acid-binding Ig-like lectins), L-type lectins, P-type lectins, M-type lectins, Jacalin-related lectin (JRL), Cyanovirin-N homologs (CVNHs), Oscillatoria agardhii agglutinin homolog (OAAH), and Galanthus nivalis agglutinin-like (GNA-like) lectins, among others [1].

Table 1.

Marine and freshwater lectins produced by algae and cyanobacteria.

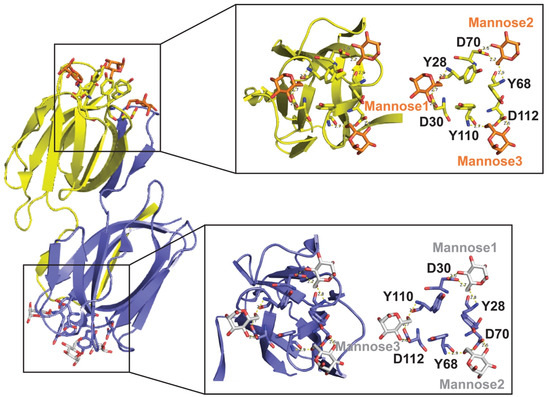

Each lectin molecule usually contains several binding sites for the simultaneous binding to multiple units of the carbohydrates they target. The three-dimensional structures of these proteins and their binding to carbohydrates can be very different among various lectins. For example, griffithsin (GRFT; Table 1) comprises 121 amino acids, where residue 31 does not appear to correspond to any standard amino acid [2]. GRFT adopts a β-prism I motif [3] observed in a variety of lectins and other proteins [4]. This motif consists of three repeats of a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet forming a triangular prism [5]. Different from other related lectins, GRFT is defined by a domain-swapped homodimer where the first 2 β-strands of one monomer are linked to 10 β-strands of the other monomer, and vice versa [6]. Several X-ray crystal structures of GRFT in complex with monosaccharides and disaccharides have been solved. These include mannose (PDB IDs 2GUC, 2GUD, and 3LL2), N-acetylglucosamine (PDB ID 2GUE), 1→ 6α−mannobiose (PDB ID 2HYQ), and maltose (PDB ID 2HYR) [6,7,8]. For example, Figure 1 shows the complex between GRFT and six mannoses corresponding to six carbohydrate (mannose)-binding sites. Each GRFT mannose-binding site encloses Tyr and Asp residues in which both amino acids form three hydrogen bonds with each mannose. The three GRFT mannose-binding sites in each monomer are arranged to create an almost perfect equilateral triangle.

Figure 1.

Three-Dimensional Structure of Griffithsin (GRFT)-Mannose Complex (PDB ID 2GUD at 0.94 Å resolution). Left-Panel: GRFT domain-swapped dimer. Six carbohydrate (mannose)-binding sites are shown; three for each monomer in yellow and purple, respectively. Right-Panel: Magnification of the GRFT six mannose-binding sites shown in the presence (left) and absence (right) of the β-strands cartoon representation. GRFT-Mannoses main interactions via hydrogen bonds are shown as yellow dashed lines. The three GRFT mannose-binding sites together form an almost perfect equilateral triangle.

Similarly, cyanovirin-N (CV-N; Table 1) is an elongated lectin and consists of two similar domains, each with five β-strands and two helical turns. These two domains are formed after domain swapping and are connected by helical turns [5]. This domain swapping is present in both CV-N and GRFT; however, CV-N dimers swap half of the molecule, while in GRFT only 2 β-strands out of 12 are swapped. Additionally, CV-N has been naturally isolated in monomeric and dimeric forms; whereas other lectins, such as Microcystis viridis lectin (MVL; Table 1) and GRFT, are naturally produced only in their dimeric form. Furthermore, other lectins such as scytovirin (SVN; Table 1) seem to be produced in the monomeric form [5].

The role lectins play varies in the different organisms that produce them; they are involved in various biological processes. For example, in mammalians, lectins can be involved in cell-to-cell self-recognition, gamete fertilization, embryonic development, cell differentiation, apoptosis, immunomodulation, and inflammation, among other functions. In the case of marine or freshwater organisms, the main topic of this review, the functions that lectins play have been associated with cell-to-cell recognition, attachment, and bioflocculation, providing a competitive advantage over other organisms in their natural habitat [9].

1.2. Algal and Cyanobacterial Lectins: Their Classification and Characteristics

Marine species account for about half of total biodiversity and thus have received significant attention for their ability to produce natural molecules with potential biomedical properties [10,11]. One type of these molecules comprises lectins, proteins with a high affinity for carbohydrates, particularly those found on the surface of many pathogens. Significant sources of biomedical lectins include cyanobacteria (17%), green algae (22%), and red algae (61%) [12].

Cyanobacteria are a diverse group of oxygenic photosynthetic prokaryotes commonly found in a broad range of aquatic and terrestrial environments. They flourish at the surfaces of lakes and oceans and form mats in benthic environments. They can tolerate higher temperatures than eukaryotic cells, and can tolerate high salinity environments, desiccation, and water stress. Cyanobacteria are also known as blue-green algae because they produce phycocyanin pigment, which gives the cells a bluish color when present in high concentrations [13]. In addition to playing a pivotal role in changing the composition of the planet’s atmosphere, several species have been studied for their ability to produce biomolecules of importance in the biomedical field.

Marine algae are diverse organisms: Rhodophyta (red algae) and Chlorophyta (green algae) differ in their pigments, anatomy, and reproduction. They are one of the oldest types of marine organisms on earth and require salty/brackish water and sunlight. They are usually found attached to rocky surfaces. Like cyanobacteria, marine algae constitute an essential source of biomolecules, particularly lectins, that have promising applications in biomedicine [14]. Table 1 summarizes some of the most relevant lectins identified in these marine species.

3. Antibacterial Activity of Marine and Freshwater Lectins

Though there are several examples in the literature of algal lectins as antivirals and several reports of lectins from many different sources that have antibacterial activity, there are relatively few studies in the literature that specifically address the potential usefulness of algal or cyanobacterial lectins as antibacterial agents [40,113,114]. This section will review the relevant information available. In all cases, standard microbiological methods were employed by researchers to test for inhibition of bacterial growth, including disk diffusion and culture density assays.

In one study, Liao et al. [115] showed that purified lectins isolated from two red algal species, Eucheuma serra (ESA) and Galaxaura marginate (GMA), strongly inhibited the growth of the pathogenic marine Gram-negative Vibrio vulnificus, although it showed no activity against two other Vibrio species, V. peagius and V. neresis. Selective inhibition was attributed to differences in bacterial surface carbohydrates. In addition, this study showed that whereas saline and ethanol extracts of several algal species exhibited antibacterial activity against both V. vulnicius and V. peaguius, this activity was inhibited by pre-treatment with lectin-binding sugars and glycoproteins, suggesting that lectins present in the algal extracts were the active inhibitory agents. Hung et al. [116] further demonstrated that lectins isolated from the red algae Eucheuma denitculatum (EDA) exhibit activity against another pathogenic marine vibrio, V. alginolyticus, but not against V. parahaemolyticus or V. harveyi. Binding assays suggested that selective activity was through binding of the EDA lectins to high-mannose N-glycans.

Holanda and colleagues reported differential activity of lectins from the marine red alga S. filiformis against human pathogenic bacteria [117]. In this study, isolated lectins inhibited the growth of Gram-negative bacteria Salmonella typhi, Serratia marcescens, Enterobacter aerogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus sp. There was no inhibitory effect, however, on Gram-negative S. typhimurium or Escherichia coli, nor was there any inhibition of Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, or Bacillus cereus. For inhibited strains, bacterial cell density was significantly reduced in the presence of lectin at high concentrations (1 mg/mL), but cell density assays showed that bacteria exhibited all phases of cell growth. The investigators suggested that mannan present on cell walls of Gram-negative bacteria might bind to lectin and alter the flow of nutrients, thereby causing inhibition of growth [45,113].

Vasconcelos et al. tested the effect of isolated lectins from two species of red algae, Bryothamnion seaforthii (BSL) and Hypnea musciformis (HML), for their ability to inhibit growth in biofilms of Gram-positive S. epidermidis and S. aureus, and of Gram-negative Klebsiella oxytoca, P. aeruginosa, Candida albicans, and Candida tropicalis. Whereas HML and BSL both caused weak growth reductions in S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and P. aeruginosa, only HML reduced the growth of K. oxytoca [118]. For S. aureus, BSL decreased the biofilm mass at all concentrations used; however, HML caused only a small decrease at the highest concentration tested (250 µg/mL). In addition, these lectins caused only a small decrease in the number of viable S. aureus cells. The biofilm mass of K. oxytoca was also reduced in the presence of these lectins, but with no decrease in the number of viable cells [118].

Collectively, these investigators have suggested the potential usefulness of marine lectins as natural alternatives to conventional antibiotics in therapeutic interventions for infections by Gram-negative pathogens [117] and for the protection of marine species susceptible to marine vibrio infection [40,113,114]. With the global rise in antibiotic resistance over the past century, there has been a pressing need to find alternative sources of antibiotic agents for therapeutic use. As demonstrated in the studies reviewed here, the ability of algal lectins to inhibit the growth of various pathogenic bacteria makes them potential candidates for medicinal use and is worth further investigation.

4. Antiprotozoal Activity of Marine Lectins

Although metabolite extracts obtained from some marine algae have been shown to exhibit antiprotozoal activity, there are few reports in the literature of activity specifically attributed to algal or cyanobacterial lectins. Reports include the activity of algal extracts from Bostrychia tenella against Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania amazonensis [119]; from various species of brown algae against T. cruzi, Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, L. donovani, Sargassaceae sp. [120]; and from Anadyomene saldanhae, Caulerpa cupressoides, Canistrocarpus cervicornis, Dictyota sp., Ochtodes secundiramea, and Padina sp. against L. braziliensis. Chatterjee et al. further report that GRFT exhibits anti-protozoal activity against T. vaginalis and Tritichomonas foetus in a vaginal mouse model [17]. This is the only report of an algal lectin having such activity. Investigation into the possible activity of other marine lectins might yield novel insights into therapeutic uses against parasitic protozoan infections.

5. Expression of Marine Lectins in Heterologous Systems

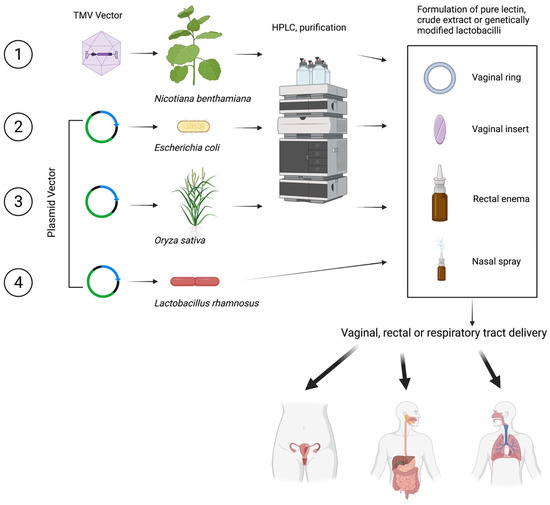

Expressing lectins in heterologous systems can lead to a cost-effective production for pharmaceutical purposes. The heterologous systems provide higher yields than conventional purification and reduce the production cost and time [121]. Several models have been used for the heterologous production of lectins, such as bacteria, yeast, plants, mammalian, and insect cells. Figure 2 shows different strategies used for the expression and purification of GRFT and their intended use.

Figure 2.

Strategies to produce and purify GRFT in heterologous systems. Created with BioRender.com.

GRFT is the marine lectin in which expression in heterologous systems has been more widely explored. The expression of GRFT in tobacco plants (Nicotiana benthamiana) has been one of the choices. For this purpose, a synthetic cDNA (GenBank no. FJ594069) encoding the 121 amino acids of GRFT has been cloned into a tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) vector in which GRFT is expressed under the control of a duplicated coat protein subgenomic promoter. N. benthamiana seedlings are inoculated with infectious recombinant TMV, and the infected leaf biomass is processed 12 days after infection to extract GRFT [31]. The studies have shown that GRFT becomes the most abundant protein in the plant material and can be purified through filtration and chromatography. Through this process, GRFT accumulates at more than 1 g of GRFT per kilogram of N. benthamiana leaf material, providing a final product at concentrations above 20 mg/mL, and allowing production of more than 60 g of pure GRFT in a single 5000-square-foot enclosed greenhouse. The manufacturing cost of GRFT using this plant-based system has been estimated to be USD $0.32/dose. This assumes a commercial launch volume of 20 kg GRFT/year for 6.7 million doses of GRFT at 3 mg/dose, a recovery efficiency of 70%, and purity of >99%. This manufacturing process was also found to have a favorable environmental output with minimal risks to health and safety [122]. Additionally, gene-silencing suppressors for high-level production of GRFT in N. benthamiana have resulted in a higher accumulation of GRFT with a yield of 400 μg g−1 fresh weight or 287 μg g−1 after purification, representing a recovery of 71.75% [123].

Similarly, Nicotiana tabacum has been transformed with a vector containing the gene encoding CV-N. Through this process, the plant-derived CV-N can be recovered at 130 ng per mg of fresh leaf tissue. CV-N is expressed in the desired monomeric form using this plant-based system. Hydroponic culturing of transgenic plants results in CV-N rhizosecretion at 0.64 mg/mL hydroponic media after 24 days [124]. The transplastomic plants allow a highly efficient and cost-effective production platform for lectins, and dried tobacco can serve as a source material for the purification of lectins [125].

Oryza sativa (rice plant) has been used to express GRFT. For this purpose, GRFT has been expressed in the endosperm of transgenic rice plants. The yield of GRFT in this system can reach 223 g/g dry seed weight, and through a one-step purification protocol, can achieve a recovery of 74% and a purity of 80% [126].

Other host organisms for the economical and efficient production of lectins include bacteria. Hexa-histidine-tagged GRFT (His-GRFT) has been successfully produced in E. coli. Production in a fermenter with an auto-inducing medium allows the total amount of His-GRFT per liter to be increased by about 45-fold [127]. Similarly, recombinant expression in engineered E. coli results in GRFT concentrations of 2.5 g/L. This could translate into production volumes of >20 tons per year at the cost of goods sold below USD $3500/kg [128].

Finally, probiotic lactobacilli have been studied for the expression of lectins. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and GR-1 have been engineered to express GRFT [129], while Lactobacillus jensenii and Lactobacillus plantarum have been used to express CV-N [130,131,132] and SVN [133], respectively. The idea behind this strategy is that lectin-producing lactobacilli could colonize the mucosal epithelium and produce the lectin in vivo to protect the host if exposed to HIV or other pathogens.

6. Preclinical and Clinical Safety Studies of Marine and Freshwater Lectins

In addition to the potent antimicrobial activity, the safety of potential lectin-based products is of paramount importance. Comprehensive preclinical and clinical safety evaluations must be performed as part of product development [134]. This section reviews the preclinical and clinical studies that have been performed for these lectins.

CV-N: CV-N has been of particular interest for the development of a topical anti-HIV microbicide. Prolonged production of recombinant CV-N by L. jensenii vaginally in nonhuman primates did not induce any observable adverse effects or inflammatory biomarkers [135]. However, there are some safety concerns over the use of CV-N. CV-N affected PBMCs morphology, induced mitogenic activity in PBMCs, and increased expression of cellular activation markers and several cytokines following prolonged exposure [136,137]. CV-N can bind to cellular proteins and might induce potential toxic effects [89]. Furthermore, some paradoxical effects of CV-N enhancing R5 HIV infection at low concentrations were reported [138]. CV-N has been modified by site-specific conjugation with polyethylene glycol in a reaction called PEGylation to improve the drug-like properties of this lectin [139]. When administered intravenously, the PEGylated CV-N was significantly less immunogenic than CV-N [139]. The safety concerns observed in vitro have reduced the enthusiasm for this lectin.

MVN and MVL: MVN isolated from Microcystis aeruginosa shares partial homology with CV-N, has a potent but narrow anti-HIV profile, and demonstrates a better safety profile than CV-N [72]. However, several cytokines were significantly increased in PBMCs after exposure to this lectin [72]. The incubation of PBMCs with MVN leads to weak induction of expression of activation markers but did not activate or enhance viral replication in pretreated cells [72,140].

Like CV-N, MVL binds to the target cell surface and the viral envelope [89]. Cytotoxic effects triggered by the lectin might occur because of MVL interaction with cellular proteins. Indeed, MVL inhibited cell viability in several cell lines, including Hep-G2 (human hepatocellular liver carcinoma), HT-29 (human colon cancer), SGC-7901 (stomach cancer), and SK-OV-3 (human ovarian cancer) (IC50 40–53 µg/mL)) [141].

OAA: OAA is a stable protein [142]. However, the development of OAA-based products might be problematic because it exerts cytotoxic effects such as CV-N, MVN, and MVL [44].

GRFT: GRFT has an excellent safety profile. In contrast to CV-N, GRFT, with its broad and potent antiviral activity, does not have stimulatory properties [143]. The lectin inhibits HIV infection in human cervical explant tissues with no proinflammatory cytokine production. GRFT has an excellent safety profile when tested in a rabbit vaginal irritancy model [31] or when administered in single or chronic subcutaneous doses in mice and guinea pigs [144]. GRFT is safe and minimally absorbed after repeated vaginal application. Repeated dosing of GRFT and GRFT/CG gel in small animal models revealed no adverse findings at any dose levels tested and showed that a GRFT/CG gel is non-irritating. Seven days of daily vaginal application of 0.1% GRFT/CG gel did not enhance the susceptibility of mice to HSV-2 infection. Fourteen days of daily intravenous administration of GRFT up to 8.3 mg/kg/day in rats resulted in no detectable anti-drug-antibodies (ADA) and a no adverse effect level (NOAEL) of 8.3 mg/kg/day despite high systemic levels of GRFT. Fourteen days of daily vaginal GRFT/CG gel dosing (up to 0.3% GRFT) in rats resulted in a NOAEL of 0.3% GRFT and little or no vaginal irritation. This regimen also resulted in little or no systemic detection of GRFT. A related study in rabbits also found a NOAEL of 0.3% GRFT and little or no vaginal irritation [18].

GRFT’s preclinical safety, lack of systemic absorption after vaginal administration in animal studies, and lack of cross-resistance with existing antiretroviral drugs prompted its development for topical HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The Population Council investigated the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity of a vaginal gel (PC-6500: 0.1% GRFT in a CG gel) in healthy women after vaginal administration. In this first-in-human trial of GRFT, no significant adverse events were recorded in clinical or laboratory results or histopathological evaluations in cervicovaginal mucosa. Additionally, no anti-drug (GRFT) antibodies were detected in serum, and no cervicovaginal proinflammatory responses or changes in the ectocervical transcriptome were evident. Decreased levels of proinflammatory chemokines in CVLs were observed, while GRFT was not detected in plasma after vaginal application. GRFT and GRFT/CG in CVL samples inhibited HIV and HPV, respectively, ex vivo in a dose-dependent manner. This study suggested that GRFT formulated in combination with CG is a safe and promising multipurpose prevention technology product that warrants further investigation (Teleshova et al. submitted). The Population Council is currently investigating fast-dissolving inserts and vaginal rings containing Q-GRFT alone or in combination with CG. Q-GRFT is a version of GRFT in which a methionine has been substituted by another amino acid (M78Q) to reduce the potential oxidation of this lectin. An additional phase 1 clinical trial (PREVENT), led by the University of Louisville and the University of Pittsburgh, was planned to look at a GRFT-based rectal microbicide safety. This trial was terminated, and the study enrollment was prematurely halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The trial was designed to study if a single dose of an enema containing Q-GRFT was safe, well tolerated, and acceptable in healthy adults practicing receptive anal intercourse [145].

Limited preclinical safety data are available for several promising lectins, including SVN, BCA, KAA-2, and HRL40.

7. Conclusions

The sui generis mode of action of mannose-binding lectins such as GRFT, SVN, CV-N, OAA, and MVL against important pathogens has prompted the development of these molecules as potential therapeutics or prophylactic drugs to target single or multiple infectious diseases. Lectins are highly specific, might show broad-spectrum activity, are locally (topically) delivered, and are relatively potent. As such, they deserve additional investigation. That said, there are safety concerns with some lectins that induce mitogenic activity after prolonged exposures, and mass production of lectins is a relatively nascent field. GRFT might be an especially promising candidate. GRFT has activity that seems to be among the broadest of any yet-evaluated lectin, is an exception to the mitogenic activity, has been tested in phase 1 clinical trials with promising results regarding its safety in topical formulations, and appears to be producible in cost-effective doses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.F.R.; visualization, Y.R. and J.A.F.R.; writing—original draft preparation J.A.F.R., M.G.P., C.P., A.K., Y.R., J.S. and N.T.; writing—review and editing J.A.F.R., M.G.P., C.P., A.K., Y.R., J.S. and N.T.; funding acquisition J.S. and J.A.F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by The Population Council.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ghazarian, H.; Idoni, B.; Oppenheimer, S.B. A glycobiology review: Carbohydrates, lectins and implications in cancer therapeutics. Acta Histochem. 2011, 113, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Sowder, R.C., 2nd; Bringans, S.; Gardella, R.; Berg, S.; Cochran, P.; Turpin, J.A.; Buckheit, R.W., Jr.; McMahon, J.B.; et al. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 9345–9353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chothia, C.; Murzin, A.G. New folds for all-beta proteins. Structure 1993, 1, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Morikawa, K. The beta-prism: A new folding motif. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996, 21, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolkowska, N.E.; Wlodawer, A. Structural studies of algal lectins with anti-HIV activity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2006, 53, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolkowska, N.E.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Mori, T.; Zhu, C.; Giomarelli, B.; Vojdani, F.; Palmer, K.E.; McMahon, J.B.; Wlodawer, A. Domain-swapped structure of the potent antiviral protein griffithsin and its mode of carbohydrate binding. Structure 2006, 14, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaei, T.; Shenoy, S.R.; Giomarelli, B.; Thomas, C.; McMahon, J.B.; Dauter, Z.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Wlodawer, A. Monomerization of viral entry inhibitor griffithsin elucidates the relationship between multivalent binding to carbohydrates and anti-HIV activity. Structure 2010, 18, 1104–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziolkowska, N.E.; Shenoy, S.R.; O’Keefe, B.R.; McMahon, J.B.; Palmer, K.E.; Dwek, R.A.; Wormald, M.R.; Wlodawer, A. Crystallographic, thermodynamic, and molecular modeling studies of the mode of binding of oligosaccharides to the potent antiviral protein griffithsin. Proteins 2007, 67, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, H.; Poduval, P.B. Chapter 9—Microbial lectins: Roles and applications. In Advances in Biological Science Research: A Practical Approach; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Aneiros, A.; Garateix, A. Bioactive peptides from marine sources: Pharmacological properties and isolation procedures. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2004, 803, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, R.C.; Wong, J.H.; Pan, W.; Chan, Y.S.; Yin, C.; Dan, X.; Ng, T.B. Marine lectins and their medicinal applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 3755–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.S.; Thakur, S.R.; Bansal, P. Algal lectins as promising biomolecules for biomedical research. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 41, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Y.; Gurevitz, M. The Cyanobacteria—Ecology, physiology and molecular genetics. In The Prokaryotes; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pagarete, A.; Ramos, A.S.; Puntervoll, P.; Allen, M.J.; Verdelho, V. Antiviral potential of algal metabolites—A comprehensive review. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, K.B.; Gray, E.S.; Pantophlet, R.; Moore, P.L.; McMahon, J.B.; Chakauya, E.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Chikwamba, R.; Morris, L. Binding of the mannose-specific lectin, griffithsin, to HIV-1 gp120 exposes the CD4-binding site. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 9039–9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaidi, S.; Cornejal, N.; Mahoney, O.; Melo, C.; Verma, N.; Bonnaire, T.; Chang, T.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Sailer, J.; Zydowsky, T.M.; et al. Griffithsin and carrageenan combination results in antiviral synergy against SARS-CoV-1 and 2 in a pseudoviral model. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Ratner, D.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Johnson, P.J.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Secor, W.E.; Anderson, D.J.; Robbins, P.W.; Samuelson, J. Anti-retroviral lectins have modest effects on adherence of trichomonas vaginalis to epithelial cells in vitro and on recovery of tritrichomonas foetus in a Mouse Vaginal Model. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135340. [Google Scholar]

- Derby, N.; Lal, M.; Aravantinou, M.; Kizima, L.; Barnable, P.; Rodriguez, A.; Lai, M.; Wesenberg, A.; Ugaonkar, S.; Levendosky, K.; et al. Griffithsin carrageenan fast dissolving inserts prevent SHIV HSV-2 and HPV infections in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emau, P.; Tian, B.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Mori, T.; McMahon, J.B.; Palmer, K.E.; Jiang, Y.; Bekele, G.; Tsai, C.C. Griffithsin, a potent HIV entry inhibitor, is an excellent candidate for anti-HIV microbicide. J. Med. Primatol. 2007, 36, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferir, G.; Palmer, K.E.; Schols, D. Synergistic activity profile of griffithsin in combination with tenofovir, maraviroc and enfuvirtide against HIV-1 clade C. Virology 2011, 417, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoorelbeke, B.; Xue, J.; LiWang, P.J.; Balzarini, J. Role of the carbohydrate-binding sites of griffithsin in the prevention of DC-SIGN-mediated capture and transmission of HIV-1. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishag, H.Z.; Li, C.; Huang, L.; Sun, M.X.; Wang, F.; Ni, B.; Malik, T.; Chen, P.Y.; Mao, X. Griffithsin inhibits Japanese encephalitis virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishag, H.Z.; Li, C.; Wang, F.; Mao, X. Griffithsin binds to the glycosylated proteins (E and prM) of Japanese encephalitis virus and inhibit its infection. Virus Res. 2016, 215, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levendosky, K.; Mizenina, O.; Martinelli, E.; Jean-Pierre, N.; Kizima, L.; Rodriguez, A.; Kleinbeck, K.; Bonnaire, T.; Robbiani, M.; Zydowsky, T.M.; et al. Griffithsin and carrageenan combination to target herpes simplex virus 2 and human papillomavirus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7290–7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, P.; Albecka, A.; Belouzard, S.; Vercauteren, K.; Verhoye, L.; Wychowski, C.; Leroux-Roels, G.; Palmer, K.E.; Dubuisson, J. Griffithsin has antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 5159–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micewicz, E.D.; Cole, A.L.; Jung, C.L.; Luong, H.; Phillips, M.L.; Pratikhya, P.; Sharma, S.; Waring, A.J.; Cole, A.M.; Ruchala, P. Grifonin-1: A small HIV-1 entry inhibitor derived from the algal lectin, Griffithsin. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15214–15219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaei, T.; Alexandre, K.B.; Shenoy, S.R.; Meyerson, J.R.; Krumpe, L.R.; Constantine, B.; Wilson, J.; Buckheit, R.W., Jr.; McMahon, J.B.; Subramaniam, S.; et al. Griffithsin tandemers: Flexible and potent lectin inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus. Retrovirology 2015, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, B.; Stefanidou, M.; Mesquita, P.M.; Fakioglu, E.; Segarra, T.; Rohan, L.; Halford, W.; Palmer, K.E.; Herold, B.C. Griffithsin protects mice from genital herpes by preventing cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6257–6269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, B.R.; Giomarelli, B.; Barnard, D.L.; Shenoy, S.R.; Chan, P.K.; McMahon, J.B.; Palmer, K.E.; Barnett, B.W.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Wohlford-Lenane, C.L. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family Coronaviridae. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 2511–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, B.R.; Vojdani, F.; Buffa, V.; Shattock, R.J.; Montefiori, D.C.; Bakke, J.; Mirsalis, J.; d’Andrea, A.L.; Hume, S.D.; Bratcher, B.; et al. Scaleable manufacture of HIV-1 entry inhibitor griffithsin and validation of its safety and efficacy as a topical microbicide component. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 6099–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, Y.; Saucedo, C.J.; Lund, G.; Uenishi, R.; Hase, S.; Tsuchiura, T.; Kneteman, N.; Ramessar, K.; Tyrrell, D.L.; Shirakura, M.; et al. Antiviral lectins from red and blue-green algae show potent in vitro and in vivo activity against hepatitis C virus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Gao, Y.; Hoorelbeke, B.; Kagiampakis, I.; Zhao, B.; Demeler, B.; Balzarini, J.; Liwang, P.J. The role of individual carbohydrate-binding sites in the function of the potent anti-HIV lectin griffithsin. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 2613–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Hoorelbeke, B.; Kagiampakis, I.; Demeler, B.; Balzarini, J.; Liwang, P.J. The griffithsin dimer is required for high-potency inhibition of HIV-1: Evidence for manipulation of the structure of gp120 as part of the griffithsin dimer mechanism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3976–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.; Boo, S.M. Evidence for two independent lineages of Griffithsia (Ceramiaceae, Rhodophyta) based on plastid protein-coding psaA, psbA, and rbcL gene sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004, 31, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, L.G.; Lasala, F.; Otero, J.R.; Sanchez, A.; Delgado, R. In vitro evaluation of cyanovirin-N antiviral activity, by use of lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with filovirus envelope glycoproteins. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, 1440–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, L.G.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Bray, M.; Sanchez, A.; Gronenborn, A.M.; Boyd, M.R. Cyanovirin-N binds to the viral surface glycoprotein, GP1,2 and inhibits infectivity of Ebola virus. Antivir. Res. 2003, 58, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.; Lerner, D.L.; Lusso, P.; Boyd, M.R.; Elder, J.H.; Berger, E.A. Multiple antiviral activities of cyanovirin-N: Blocking of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 interaction with CD4 and coreceptor and inhibition of diverse enveloped viruses. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 4562–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, B.R.; Smee, D.F.; Turpin, J.A.; Saucedo, C.J.; Gustafson, K.R.; Mori, T.; Blakeslee, D.; Buckheit, R.; Boyd, M.R. Potent anti-influenza activity of cyanovirin-N and interactions with viral hemagglutinin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2518–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.; Walia, A.K.; Khattar, J.S.; Singh, D.P.; Kennedy, J.F. Cyanobacterial lectins characteristics and their role as antiviral agents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smee, D.F.; Bailey, K.W.; Wong, M.H.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Gustafson, K.R.; Mishin, V.P.; Gubareva, L.V. Treatment of influenza A (H1N1) virus infections in mice and ferrets with cyanovirin-N. Antivir. Res. 2008, 80, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smee, D.F.; Wandersee, M.K.; Checketts, M.B.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Saucedo, C.; Boyd, M.R.; Mishin, V.P.; Gubareva, L.V. Influenza A (H1N1) virus resistance to cyanovirin-N arises naturally during adaptation to mice and by passage in cell culture in the presence of the inhibitor. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2007, 18, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gremberghe, I.; Leliaert, F.; Mergeay, J.; Vanormelingen, P.; Van der Gucht, K.; Debeer, A.E.; Lacerot, G.; De Meester, L.; Vyverman, W. Lack of phylogeographic structure in the freshwater cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa suggests global dispersal. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Okuyama, S.; Hori, K. Primary structure and carbohydrate binding specificity of a potent anti-HIV lectin isolated from the filamentous cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11021–11029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holanda, M.L.; Melo, V.M.; Silva, L.M.; Amorim, R.C.; Pereira, M.G.; Benevides, N.M. Differential activity of a lectin from Solieria filiformis against human pathogenic bacteria. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2005, 38, 1769–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, M.; Shibata, H.; Imamura, K.; Sakaguchi, T.; Hori, K. High-mannose specific lectin and its recombinants from a carrageenophyta kappaphycus alvarezii represent a potent anti-HIV activity through high-affinity binding to the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120. Mar. Biotechnol. 2016, 18, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Hirayama, M.; Hori, K. High mannose-specific lectin (KAA-2) from the red alga Kappaphycus alvarezii potently inhibits influenza virus infection in a strain-independent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 405, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Kubo, T.; Sakaguchi, T.; Nishizono, A.; Hirayama, M.; Hori, K. Entry inhibition of influenza viruses with high mannose binding lectin ESA-2 from the red alga eucheuma serra through the recognition of viral hemagglutinin. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3454–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Hirayama, M.; Morimoto, K.; Yamamoto, N.; Okuyama, S.; Hori, K. High mannose-binding lectin with preference for the cluster of alpha1-2-mannose from the green alga Boodlea coacta is a potent entry inhibitor of HIV-1 and influenza viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 19446–19458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Hirayama, M.; Sato, Y.; Morimoto, K.; Hori, K. A novel high-mannose specific lectin from the green alga halimeda renschii exhibits a potent anti-influenza virus activity through high-affinity binding to the viral hemagglutinin. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, A.R.; Giomarelli, B.G.; Lear-Rooney, C.M.; Saucedo, C.J.; Yellayi, S.; Krumpe, L.R.; Rose, M.; Paragas, J.; Bray, M.; Olinger, G.G., Jr.; et al. The cyanobacterial lectin scytovirin displays potent in vitro and in vivo activity against Zaire Ebola virus. Antivir. Res. 2014, 112, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, K.B.; Gray, E.S.; Lambson, B.E.; Moore, P.L.; Choge, I.A.; Mlisana, K.; Karim, S.S.; McMahon, J.; O’Keefe, B.; Chikwamba, R.; et al. Mannose-rich glycosylation patterns on HIV-1 subtype C gp120 and sensitivity to the lectins, Griffithsin, Cyanovirin-N and Scytovirin. Virology 2010, 402, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, J. Targeting the glycans of gp120: A novel approach aimed at the Achilles heel of HIV. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, P.M.; Elliott, T.; Cresswell, P.; Wilson, I.A.; Dwek, R.A. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science 2001, 291, 2370–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, C.N.; Saunders, K.O. Chapter 2: Antibody responses to the HIV-1 envelope high mannose patch. Adv. Immunol. 2019, 143, 11–73. [Google Scholar]

- Coss, K.P.; Vasiljevic, S.; Pritchard, L.K.; Krumm, S.A.; Glaze, M.; Madzorera, S.; Moore, P.L.; Crispin, M.; Doores, K.J. HIV-1 glycan density drives the persistence of the mannose patch within an infected individual. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 11132–11144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bonsignori, M.; Hwang, K.K.; Chen, X.; Tsao, C.Y.; Morris, L.; Gray, E.; Marshall, D.J.; Crump, J.A.; Kapiga, S.H.; Sam, N.E.; et al. Analysis of a clonal lineage of HIV-1 envelope V2/V3 conformational epitope-specific broadly neutralizing antibodies and their inferred unmutated common ancestors. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 9998–10009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doria-Rose, N.A.; Bhiman, J.N.; Roark, R.S.; Schramm, C.A.; Gorman, J.; Chuang, G.Y.; Pancera, M.; Cale, E.M.; Ernandes, M.J.; Louder, M.K.; et al. New member of the V1V2-directed CAP256-VRC26 lineage that shows increased breadth and exceptional potency. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowska, E.; Le, K.M.; Ramos, A.; Doores, K.J.; Lee, J.H.; Blattner, C.; Ramirez, A.; Derking, R.; van Gils, M.J.; Liang, C.H.; et al. Broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies define a glycan-dependent epitope on the prefusion conformation of gp41 on cleaved envelope trimers. Immunity 2014, 40, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kang, B.H.; Pancera, M.; Lee, J.H.; Tong, T.; Feng, Y.; Imamichi, H.; Georgiev, I.S.; Chuang, G.Y.; Druz, A.; et al. Broad and potent HIV-1 neutralization by a human antibody that binds the gp41-gp120 interface. Nature 2014, 515, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Lee, J.H.; Doores, K.J.; Murin, C.D.; Julien, J.P.; McBride, R.; Liu, Y.; Marozsan, A.; Cupo, A.; Klasse, P.J.; et al. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejchal, R.; Doores, K.J.; Walker, L.M.; Khayat, R.; Huang, P.S.; Wang, S.K.; Stanfield, R.L.; Julien, J.P.; Ramos, A.; Crispin, M.; et al. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science 2011, 334, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharf, L.; Scheid, J.F.; Lee, J.H.; West, A.P., Jr.; Chen, C.; Gao, H.; Gnanapragasam, P.N.; Mares, R.; Seaman, M.S.; Ward, A.B.; et al. Antibody 8ANC195 reveals a site of broad vulnerability on the HIV-1 envelope spike. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoning, G.; Plonait, H. Metaphylaxis and therapy of the MMA syndrome of sows with Baytril. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 1990, 97, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L.M.; Phogat, S.K.; Chan-Hui, P.Y.; Wagner, D.; Phung, P.; Goss, J.L.; Wrin, T.; Simek, M.D.; Fling, S.; Mitcham, J.L.; et al. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 2009, 326, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, J.; Van Damme, L. Microbicide drug candidates to prevent HIV infection. Lancet 2007, 369, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Jin, W.; Griffin, G.E.; Shattock, R.J.; Hu, Q. Removal of two high-mannose N-linked glycans on gp120 renders human immunodeficiency virus 1 largely resistant to the carbohydrate-binding agent griffithsin. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 2367–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, K.B.; Gray, E.S.; Mufhandu, H.; McMahon, J.B.; Chakauya, E.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Chikwamba, R.; Morris, L. The lectins griffithsin, cyanovirin-N and scytovirin inhibit HIV-1 binding to the DC-SIGN receptor and transfer to CD4(+) cells. Virology 2012, 423, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, J.; Van Herrewege, Y.; Vermeire, K.; Vanham, G.; Schols, D. Carbohydrate-binding agents efficiently prevent dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN)-directed HIV-1 transmission to T lymphocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 71, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Du, T.; Li, C.; Luo, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Hu, Q. Sensitivity of transmitted and founder human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelopes to carbohydrate-binding agents griffithsin, cyanovirin-N and Galanthus nivalis agglutinin. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 3660–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, K.B.; Moore, P.L.; Nonyane, M.; Gray, E.S.; Ranchobe, N.; Chakauya, E.; McMahon, J.B.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Chikwamba, R.; Morris, L. Mechanisms of HIV-1 subtype C resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN. Virology 2013, 446, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskens, D.; Ferir, G.; Vermeire, K.; Kehr, J.C.; Balzarini, J.; Dittmann, E.; Schols, D. Microvirin, a novel alpha(1,2)-mannose-specific lectin isolated from Microcystis aeruginosa, has anti-HIV-1 activity comparable with that of cyanovirin-N but a much higher safety profile. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 24845–24854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferir, G.; Huskens, D.; Palmer, K.E.; Boudreaux, D.M.; Swanson, M.D.; Markovitz, D.M.; Balzarini, J.; Schols, D. Combinations of griffithsin with other carbohydrate-binding agents demonstrate superior activity against HIV Type 1, HIV Type 2, and selected carbohydrate-binding agent-resistant HIV Type 1 strains. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2012, 28, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellett, P.E.; Roizman, B. Herpesviridae. In Fields Virology, 6th ed.; Knipe, D.M., Howley, P.M., Eds.; Lippincott-Raven Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 1802–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, H.Y.; Cohen, G.H.; Eisenberg, R.J. Identification of functional regions of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein gD by using linker-insertion mutagenesis. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 2529–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leumi, S.; El Kassas, M.; Zhong, J. Hepatitis C virus genotype 4: A poorly characterized endemic genotype. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 6079–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, D.; Penin, F.; Rice, C.M. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.B.; Bukh, J.; Kuiken, C.; Muerhoff, A.S.; Rice, C.M.; Stapleton, J.T.; Simmonds, P. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: Updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource. Hepatology 2014, 59, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Structural biology of the hepatitis C virus proteins. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2012, 9, e175–e226.

- Dubuisson, J. Hepatitis C virus proteins. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 2406–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.W.; Chang, K.M. Hepatitis C virus: Virology and life cycle. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2013, 19, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krey, T.; d’Alayer, J.; Kikuti, C.M.; Saulnier, A.; Damier-Piolle, L.; Petitpas, I.; Johansson, D.X.; Tawar, R.G.; Baron, B.; Robert, B.; et al. The disulfide bonds in glycoprotein E2 of hepatitis C virus reveal the tertiary organization of the molecule. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedicto, I.; Gondar, V.; Molina-Jimenez, F.; Garcia-Buey, L.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Gastaminza, P.; Majano, P.L. Clathrin mediates infectious hepatitis C virus particle egress. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4180–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, E.; Belouzard, S.; Goueslain, L.; Wakita, T.; Dubuisson, J.; Wychowski, C.; Rouille, Y. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6964–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenbach, B.D.; Rice, C.M. The ins and outs of hepatitis C virus entry and assembly. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffard, A.; Callens, N.; Bartosch, B.; Wychowski, C.; Cosset, F.L.; Montpellier, C.; Dubuisson, J. Role of N-linked glycans in the functions of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 8400–8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieyres, G.; Thomas, X.; Descamps, V.; Duverlie, G.; Patel, A.H.; Dubuisson, J. Characterization of the envelope glycoproteins associated with infectious hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 10159–10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, F.; Wychowski, C.; Vu-Dac, N.; Gustafson, K.R.; Voisset, C.; Dubuisson, J. Cyanovirin-N inhibits hepatitis C virus entry by binding to envelope protein glycans. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 25177–25183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachko, A.; Loesgen, S.; Shahzad-Ul-Hussan, S.; Tan, W.; Zubkova, I.; Takeda, K.; Wells, F.; Rubin, S.; Bewley, C.A.; Major, M.E. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus by the cyanobacterial protein Microcystis viridis lectin: Mechanistic differences between the high-mannose specific lectins MVL, CV-N, and GNA. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 4590–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. Griffithsin, a highly potent broad-spectrum antiviral lectin from red algae: From discovery to clinical application. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusvarghi, S.; Bewley, C.A. Griffithsin: An antiviral lectin with outstanding therapeutic potential. Viruses 2016, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Alharbi, A.A.; Kayser, V. An overview of influenza viruses and vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders-Hastings, P.R.; Krewski, D. Reviewing the history of pandemic influenza: Understanding patterns of emergence and transmission. Pathogens 2016, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, D.P.; Balogun, R.A.; Yamada, H.; Zhou, Z.H.; Barman, S. Influenza virus morphogenesis and budding. Virus Res. 2009, 143, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moules, V.; Terrier, O.; Yver, M.; Riteau, B.; Moriscot, C.; Ferraris, O.; Julien, T.; Giudice, E.; Rolland, J.P.; Erny, A.; et al. Importance of viral genomic composition in modulating glycoprotein content on the surface of influenza virus particles. Virology 2011, 414, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamblin, S.J.; Skehel, J.J. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 28403–28409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skehel, J.J.; Wiley, D.C. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: The influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 531–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaymard, A.; Le Briand, N.; Frobert, E.; Lina, B.; Escuret, V. Functional balance between neuraminidase and haemagglutinin in influenza viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reading, P.C.; Tate, M.D.; Pickett, D.L.; Brooks, A.G. Glycosylation as a target for recognition of influenza viruses by the innate immune system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 598, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.; Han, B.; Peng, Z.; Ge, F.; Wei, B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Qian, C.; et al. Preparation of monoPEGylated Cyanovirin-N’s derivative and its anti-influenza A virus bioactivity in vitro and in vivo. J. Biochem. 2015, 157, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baseler, L.; Chertow, D.S.; Johnson, K.M.; Feldmann, H.; Morens, D.M. The pathogenesis of Ebola virus disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2017, 12, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuyama, W.; Marzi, A. Ebola virus: Pathogenesis and countermeasure development. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Lo Presti, A.; Giovanetti, M.; Montesano, C.; Amicosante, M.; Colizzi, V.; Lai, A.; Zehender, G.; Cella, E.; Angeletti, S.; et al. Genetic diversity in Ebola virus: Phylogenetic and in silico structural studies of Ebola viral proteins. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahelin, R.V. Membrane binding and bending in Ebola VP40 assembly and egress. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeffers, S.A.; Sanders, D.A.; Sanchez, A. Covalent modifications of the ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 12463–12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volchkov, V.E.; Feldmann, H.; Volchkova, V.A.; Klenk, H.D. Processing of the Ebola virus glycoprotein by the proprotein convertase furin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5762–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Fusco, M.L.; Hessell, A.J.; Oswald, W.B.; Burton, D.R.; Saphire, E.O. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature 2008, 454, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Saphire, E.O. Ebolavirus glycoprotein structure and mechanism of entry. Future Virol. 2009, 4, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, G.; Harvey, D.J.; Stroeher, U.; Feldmann, F.; Feldmann, H.; Wahl-Jensen, V.; Royle, L.; Dwek, R.A.; Rudd, P.M. Identification of N-glycans from Ebola virus glycoproteins by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight and negative ion electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 24, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barre, A.; Van Damme, E.J.M.; Simplicien, M.; Le Poder, S.; Klonjkowski, B.; Benoist, H.; Peyrade, D.; Rouge, P. Man-specific lectins from plants, fungi, algae and cyanobacteria, as potential blockers for SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) coronaviruses: Biomedical perspectives. Cells 2021, 10, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Xu, W.; Gu, C.; Cai, X.; Qu, D.; Lu, L.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, S. Griffithsin with a broad-spectrum antiviral activity by binding glycans in viral glycoprotein exhibits strong synergistic effect in combination with a pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting SARS-CoV-2 Spike S2 subunit. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 857–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, J.K.; Seron, K.; Labitt, R.N.; Danneels, A.; Palmer, K.E.; Whittaker, G.R.; Dubuisson, J.; Belouzard, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection is inhibited by griffithsin. Antivir. Res. 2016, 133, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, S.; Mazumdar, A.; Moulick, A.; Adam, V. Algal metabolites: An inevitable substitute for antibiotics. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenbach Barroso Coelho, L.C.; Marcelino Dos Santos Silva, P.; Felix de Oliveira, W.; de Moura, M.C.; Viana Pontual, E.; Soares Gomes, F.; Guedes Paiva, P.M.; Napoleao, T.H.; Dos Santos Correia, M.T. Lectins as antimicrobial agents. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.R.; Lin, J.Y.; Shieh, W.Y.; Jeng, W.L.; Huang, R. Antibiotic activity of lectins from marine algae against marine vibrios. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 30, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.D.; Hirayama, M.; Ly, B.M.; Hori, K. Purification, primary structure, and biological activity of the high-mannose N-glycan-specific lectin from cultivated Eucheuma denticulatum. J. Appl. Phycol. 2015, 27, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilljam, H.; Thiringer, G. The right to a smoke-free occupational environment is a reasonable and natural demand. Lakartidningen 1992, 89, 1977–1978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, M.A.; Arruda, F.V.; Carneiro, V.A.; Silva, H.C.; Nascimento, K.S.; Sampaio, A.H.; Cavada, B.; Teixeira, E.H.; Henriques, M.; Pereira, M.O. Effect of algae and plant lectins on planktonic growth and biofilm formation in clinically relevant bacteria and yeasts. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 365272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Felicio, R.; de Albuquerque, S.; Young, M.C.; Yokoya, N.S.; Debonsi, H.M. Trypanocidal, leishmanicidal and antifungal potential from marine red alga Bostrychia tenella J. Agardh (Rhodomelaceae, ceramiales). J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 52, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, E.M.; de Oliveira, S.Q.; Rigotto, C.; Tonini, M.L.; da Rosa Guimaraes, T.; Bittencourt, F.; Gouvea, L.P.; Aresi, C.; de Almeida, M.T.; Moritz, M.I.; et al. Anti-infective potential of marine invertebrates and seaweeds from the Brazilian coast. Molecules 2013, 18, 5761–5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Alarcon, D.; Blanco-Labra, A.; Garcia-Gasca, T. Expression of lectins in heterologous systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.; Jiang, L.; Kittleson, G.A.; Steadman, K.D.; Nandi, S.; Fuqua, J.L.; Palmer, K.E.; Tuse, D.; McDonald, K.A. Technoeconomic modeling of plant-based griffithsin manufacturing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, P.; Soccol, C.R.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Krumpe, L.R.H.; Wilson, J.; de Macedo, L.L.P.; Faheem, M.; Dos Santos, V.O.; Prado, G.S.; Botelho, M.A.; et al. Gene-silencing suppressors for high-level production of the HIV-1 entry inhibitor griffithsin in Nicotiana benthamiana. Process. Biochem. 2018, 70, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, A.; Drake, P.M.; Mahmood, N.; Harman, S.J.; Shattock, R.J.; Ma, J.K. Transgenic plant production of Cyanovirin-N, an HIV microbicide. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, D.M.; Cohen, R.J.; Glick, A.J. Soliton contributions to the third-order susceptibility of polyacetylene. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 1989, 39, 3442–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamvaka, E.; Arcalis, E.; Ramessar, K.; Evans, A.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Shattock, R.J.; Medina, V.; Stoger, E.; Christou, P.; Capell, T. Rice endosperm is cost-effective for the production of recombinant griffithsin with potent activity against HIV. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giomarelli, B.; Schumacher, K.M.; Taylor, T.E.; Sowder, R.C., 2nd; Hartley, J.L.; McMahon, J.B.; Mori, T. Recombinant production of anti-HIV protein, griffithsin, by auto-induction in a fermentor culture. Protein Expr. Purif. 2006, 47, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, J.S.; Menacho-Melgar, R.; Lynch, M.D. Low-cost, large-scale production of the anti-viral lectin griffithsin. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, M.I.; van den Broek, M.F.L.; Spacova, I.; Verhoeven, T.L.A.; Balzarini, J.; Vanderleyden, J.; Schols, D.; Lebeer, S. Engineering lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and GR-1 to express HIV-inhibiting griffithsin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Lagenaur, L.A.; Simpson, D.A.; Essenmacher, K.P.; Frazier-Parker, C.L.; Liu, Y.; Tsai, D.; Rao, S.S.; Hamer, D.H.; Parks, T.P.; et al. Engineered vaginal lactobacillus strain for mucosal delivery of the human immunodeficiency virus inhibitor cyanovirin-N. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 3250–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusch, O.; Boden, D.; Hannify, S.; Lee, F.; Tucker, L.D.; Boyd, M.R.; Wells, J.M.; Ramratnam, B. Bioengineering lactic acid bacteria to secrete the HIV-1 virucide cyanovirin. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2005, 40, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, H.S.; Xu, Q.; Fichorova, R.N. Homeostatic properties of Lactobacillus jensenii engineered as a live vaginal anti-HIV microbicide. BMC Microbiol. 2013, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janahi, E.M.A.; Haque, S.; Akhter, N.; Wahid, M.; Jawed, A.; Mandal, R.K.; Lohani, M.; Areeshi, M.Y.; Almalki, S.; Das, S.; et al. Bioengineered intravaginal isolate of Lactobacillus plantarum expresses algal lectin scytovirin demonstrating anti-HIV-1 activity. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 122, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Romero, J.A.; Teleshova, N.; Zydowsky, T.M.; Robbiani, M. Preclinical assessments of vaginal microbicide candidate safety and efficacy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 92, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagenaur, L.A.; Sanders-Beer, B.E.; Brichacek, B.; Pal, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, R.; Venzon, D.; Lee, P.P.; Hamer, D.H. Prevention of vaginal SHIV transmission in macaques by a live recombinant Lactobacillus. Mucosal. Immunol. 2011, 4, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffa, V.; Stieh, D.; Mamhood, N.; Hu, Q.; Fletcher, P.; Shattock, R.J. Cyanovirin-N potently inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in cellular and cervical explant models. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huskens, D.; Vermeire, K.; Vandemeulebroucke, E.; Balzarini, J.; Schols, D. Safety concerns for the potential use of cyanovirin-N as a microbicidal anti-HIV agent. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2008, 40, 2802–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzarini, J.; Van Laethem, K.; Peumans, W.J.; Van Damme, E.J.; Bolmstedt, A.; Gago, F.; Schols, D. Mutational pathways, resistance profile, and side effects of cyanovirin relative to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains with N-glycan deletions in their gp120 envelopes. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8411–8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappe, H.; Snell, M.E.; Bossard, M.J. PEGylation of cyanovirin-N, an entry inhibitor of HIV. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad-ul-Hussan, S.; Gustchina, E.; Ghirlando, R.; Clore, G.M.; Bewley, C.A. Solution structure of the monovalent lectin microvirin in complex with Man(alpha) (1–2) Man provides a basis for anti-HIV activity with low toxicity. J. Biol Chem. 2011, 286, 20788–20796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Recombinant microcystis viridis lectin as a potential anticancer agent. Pharmazie 2010, 65, 922–923. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, Y.; Murakami, M.; Miyazawa, K.; Hori, K. Purification and characterization of a novel lectin from a freshwater cyanobacterium, Oscillatoria agardhii. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2000, 125, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouokam, J.C.; Huskens, D.; Schols, D.; Johannemann, A.; Riedell, S.K.; Walter, W.; Walker, J.M.; Matoba, N.; O’Keefe, B.R.; Palmer, K.E. Investigation of griffithsin’s interactions with human cells confirms its outstanding safety and efficacy profile as a microbicide candidate. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, C.; Kouokam, J.C.; Lasnik, A.B.; Foreman, O.; Cambon, A.; Brock, G.; Montefiori, D.C.; Vojdani, F.; McCormick, A.A.; O’Keefe, B.R.; et al. Activity of and effect of subcutaneous treatment with the broad-spectrum antiviral lectin griffithsin in two laboratory rodent models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US National Library of Medicine. Griffithsin-Based Rectal Microbicide for PREvention of Viral ENTry (PREVENT) Clinical Trials Database. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04032717 (accessed on 31 October 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).