Abstract

Background and Objectives: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) increases the risk of coronary artery disease (CAD), and vitamin D deficiency—particularly reduced levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], the biologically active form of vitamin D that declines early in CKD due to impaired renal conversion—may be a contributing factor. This study aimed to assess the relationship between 1,25(OH)2D levels and the presence and severity of CAD in CKD patients. Materials and Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 398 non-dialysis CKD patients (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) who underwent elective coronary angiography. Serum 1,25(OH)2D and 25(OH)D levels were measured, and CAD severity was assessed using the Gensini score. Results: Lower 1,25(OH)2D levels were independently associated with both the presence and se-verity of CAD. Logistic regression revealed that each 1 pg/mL increase in 1,25(OH)2D was linked to an 11% reduction in odds of significant CAD (OR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.86–0.93; p < 0.001). In contrast, 25(OH)D was not significantly related to CAD. Linear regression showed an inverse correlation between 1,25(OH)2D and Gensini scores (β = −0.329, p < 0.001), indicating reduced disease severity with higher vitamin D levels. Subgroup analyses confirmed consistent associations across age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, and LDL-cholesterol categories. ROC analysis demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D alone had good predictive ability for CAD (AUC = 0.818), which improved to 0.925 when combined with traditional risk factors. The optimal cutoff for 1,25(OH)2D was ≤16.6 pg/mL, yielding 73.3% sensitivity and 83.5% specificity. Conclusions: Serum 1,25(OH)2D is an independent predictor of both the presence and extent of CAD in CKD patients and may serve as a valuable non-traditional biomarker for cardiovascular risk assessment.

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) represents a major health concern, leading to adverse patient outcomes and substantial healthcare expenditures [1,2]. In individuals with CKD, cardiovascular disease (CVD) stands as the predominant cause of mortality, with even mild declines in renal function being strongly correlated with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications and death [3]. This trend is also evident in the development of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) in CKD patients [4]. Despite intensive efforts to control traditional CAD risk factors, such as high blood glucose levels and hypertension, CAD continues to occur more frequently and with higher mortality rates in CKD patients compared to those without CKD [4]. This suggests that additional, non-traditional risk factors unique to CKD may contribute to CAD development. Therefore, identifying CKD-specific risk factors, in addition to established traditional risk factors, is essential for improving CAD outcomes in this population.

Vitamin D deficiency is frequently observed in individuals with CKD and results from both reduced levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] and impaired function of 1α-hydroxylase, the enzyme responsible for converting 25(OH)D into its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D] [5]. Previous research has highlighted the diverse physiological roles of vitamin D beyond its well-established involvement in bone and mineral metabolism, with deficiency in this vitamin being linked to increased mortality and unfavorable cardiovascular outcomes in both the general population and CKD patients [6,7]. Among CVDs, an elevated incidence and mortality of CAD have been associated with vitamin D deficiency in individuals undergoing coronary angiography (CAG) [6]. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests a correlation between vitamin D deficiency and both the presence and severity of CAD in patients undergoing CAG [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. However, the precise relationship between vitamin D status and CAD in CKD patients remains unclear.

Most previous studies investigating the relationship between vitamin D status and CAD have focused on serum 25(OH)D levels. However, 25(OH)D primarily reflects vitamin D stores and does not necessarily indicate biological activity, particularly in patients with CKD. In CKD, impaired renal 1α-hydroxylase activity leads to reduced conversion of 25(OH)D to its active form, 1,25(OH)2D, even when circulating 25(OH)D levels are relatively preserved. As a result, 1,25(OH)2D may serve as a more physiologically relevant marker of vitamin D status in this population. Despite this, limited data are available regarding the association between 1,25(OH)2D levels and the presence or severity of coronary artery disease in patients with CKD. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the relationship between serum 1,25(OH)2D concentrations and both the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in individuals with CKD.

Given the high prevalence of both CAD and vitamin D deficiency in CKD patients, we recognized the need to further explore this potential connection. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the association between vitamin D levels and the presence and severity of CAD in individuals with CKD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Cohort

This investigation retrospectively analyzed the medical records of 398 individuals aged 18 years or older who underwent CAG between 2010 and 2023, with available serum 1,25(OH)2D and 25(OH)D measurements. Only first-time elective CAG cases were included, while those who had undergone emergency CAG were excluded. Participants with a prior history of coronary revascularization, congenital cardiac anomalies, or cardiomyopathy were not considered. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was determined utilizing the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. All included patients had CKD, with an eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, and none were receiving dialysis. Individuals who had taken vitamin D supplements, calcimimetics, or other agents that could alter endogenous vitamin D level were omitted from the study. The research protocol adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical guidelines, with approval granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital (IRB No. 55-2025-105, approval date: 29 August 2025). Given the retrospective nature of the study, which utilized anonymized clinical data, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent.

2.2. Collected Data

Demographic and clinical details, including age, sex, smoking status, diabetes, and hypertension, were recorded. Body mass index (BMI) was computed using weight and height and expressed as kg/m2. Hypertension was characterized by either antihypertensive medication use or blood pressure exceeding 140/90 mmHg. Diabetes was defined by the use of antidiabetic medication, a fasting blood glucose level of at least 126 mg/dL, or a hemoglobin A1c reading of 6.5% or higher. Laboratory parameters such as albumin, uric acid, calcium, phosphate, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, hemoglobin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), 25(OH)D, and 1,25(OH)2D levels were measured concurrently. The urinary albumin concentration was determined using the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (mg/g Cr). Serum 25(OH)D concentrations were quantified via a chemiluminescence immunoassay (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy; reference range: 4.8–52.8 ng/mL), while 1,25(OH)2D levels were assessed with a radioimmunoassay (DIAsource ImmunoAssays, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; reference range: 19.6–54.3 pg/mL).

2.3. Coronary Angiographic Assessment

All participants underwent elective CAG, meeting the inclusion criteria. Three experienced cardiologists independently reviewed the angiographic findings. CAD was classified as significant if at least one major coronary artery exhibited lumen narrowing of 50% or more. The extent of CAD severity was quantified using the Gensini score. Scores were assigned based on the degree of luminal obstruction: 1 point for 1–25% stenosis, 2 for 26–50%, 4 for 51–75%, 8 for 76–90%, 16 for 91–99%, and 32 for total occlusion. Each score was further adjusted using weighting factors based on lesion location, such as 5 for the left main artery, 2.5 for the proximal left anterior descending and left circumflex arteries, and 1 for the proximal right coronary artery. The final Gensini score represented the cumulative sum of all lesion scores.

2.4. Statistical Approach

Continuous variables were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges and compared using Kruskal–Wallis tests. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test. The relationship between different variables and significant CAD was assessed through univariable and multivariable logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The correlation between clinical parameters and Gensini score was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation for univariable analysis and a multivariable linear regression model. Variables found to be significant in univariable analyses were included, along with clinically relevant covariates, for multivariable adjustments. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to determine the area under the curve (AUC), while the Youden index was utilized to establish the optimal threshold for serum 1,25(OH)2D levels in identifying significant CAD. Logistic regression was used to assess the AUC for combined factors, with predictive probabilities calculated accordingly. ROC curves were generated based on these probabilities, and AUC comparisons were conducted using the methodology proposed by DeLong et al. A two-tailed p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical computations were performed using SPSS version 27.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc Statistical Software version 22.023 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

Table 1 illustrates the demographic and clinical features of participants categorized by serum 1,25(OH)2D concentrations. Individuals with higher serum 1,25(OH)2D levels were generally older. There were no notable differences among the groups regarding gender distribution or smoking habits. Those in the upper tertiles exhibited a lower prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. Moreover, eGFR progressively increased with rising serum 1,25(OH)2D levels. Participants with elevated serum 1,25(OH)2D had higher hemoglobin concentrations but demonstrated lower urinary albumin, phosphate (p < 0.001), LDL-cholesterol, hsCRP, and intact PTH levels. Regarding CAD severity, individuals with greater serum 1,25(OH)2D concentrations exhibited a reduced likelihood of significant CAD (prevalence: 95.5% vs. 69.9% vs. 43.6%, p < 0.001) and had lower Gensini scores (median values: 74 vs. 32 vs. 10, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to tertiles of serum 1,25(OH)2D values (n = 398).

3.2. Relationship Between Vitamin D Levels and CAD

Table 2 outlines factors correlated with the presence of significant CAD. In the univariate logistic regression model, serum 1,25(OH)2D levels (per 1 pg/mL, OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.87–0.91, p < 0.001) showed a strong inverse relationship with significant CAD, whereas 25(OH)D levels did not exhibit a similar association. Additional factors linked to significant CAD included age, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, eGFR, urinary albumin, phosphate, LDL-cholesterol, hsCRP, and intact PTH. When adjusting for multiple variables, serum 1,25(OH)2D levels (per 1 pg/mL, OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.86–0.93, p < 0.001) remained significantly associated with the presence of CAD. Other independent factors included age (per year increase, OR: 1.08, 95% CI: 1.02–1.09), smoking (current vs. non-smoker, OR: 7.36, 95% CI: 2.41–22.46, p < 0.001), diabetes (yes vs. no, OR: 3.85, 95% CI: 1.91–7.77, p < 0.001), hypertension (yes vs. no, OR: 3.52, 95% CI: 1.79–6.95), and LDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL, OR: 1.02, 95% CI: 1.10–1.03).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable analyses for variables associated with significant CAD * in the study participants (n = 398).

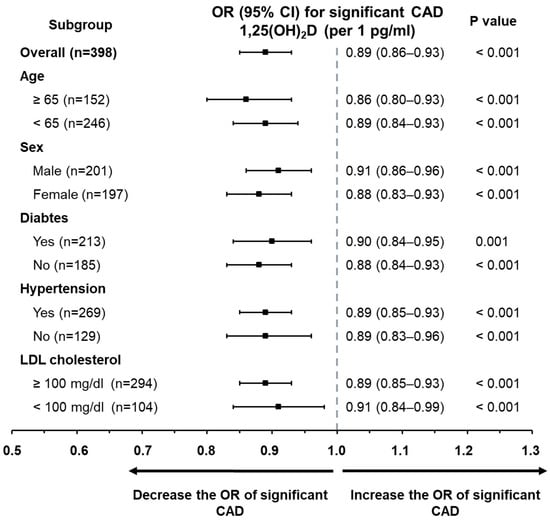

Further subgroup analyses (Figure 1) confirmed that serum 1,25(OH)2D concentrations maintained an independent inverse association with significant CAD across different stratifications, including age (≥65 vs. <65 years), sex, presence of diabetes or hypertension, and LDL-cholesterol levels (≥100 mg/dL vs. <100 mg/dL).

Figure 1.

Subgroup analysis displaying the odds ratios of 1,25(OH)2D for predicting clinically significant CAD. Through multivariate logistic regression, 1,25(OH)2D emerged as an independent factor associated with significant CAD across various predefined subpopulations. These included distinctions based on age (≥65 vs. <65 years), gender (male vs. female), diabetic status, presence of hypertension, and levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (≥100 mg/dL vs. <100 mg/dL).

Table 3 demonstrates the factors related to Gensini scores among participants. In the univariate linear regression analysis, serum 1,25(OH)2D levels were significantly inversely correlated with Gensini scores (r = −0.539, p < 0.001), whereas 25(OH)D levels did not show a similar correlation. Other variables related to Gensini scores included age, gender, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, eGFR, urinary albumin, phosphate, LDL-cholesterol, hemoglobin, hsCRP, and intact PTH. In the multivariate linear regression analysis, serum 1,25(OH)2D concentrations (β = −0.329, p < 0.001) remained strongly associated with Gensini score. Additional significant factors included age (β = 0.203, p < 0.001), smoking status (β = 0.126, p < 0.001), diabetes (β = 0.187, p < 0.001), hypertension (β = 0.149, p < 0.001), and LDL-cholesterol (β = 0.162, p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analyses for variables associated with Gensini score in the study participants (n = 398).

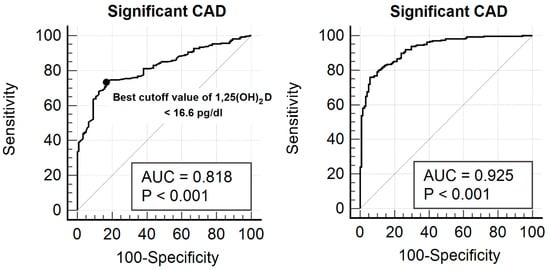

3.3. Diagnostic Performance of 1,25(OH)2D for Significant CAD

ROC analysis assessed the effectiveness of serum 1,25(OH)2D in identifying significant CAD (Figure 2). The AUC for 1,25(OH)2D in detecting significant CAD was 0.818 (95% CI: 0.777–0.855). The optimal threshold for 1,25(OH)2D was ≤16.6 pg/mL, with a sensitivity of 73.3% and a specificity of 83.5%. To construct the combined predictive model, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed including serum 1,25(OH)2D levels and other independent predictors of significant coronary artery disease identified in the multivariable analysis, namely age, current smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, and LDL-cholesterol. Predicted probabilities derived from this logistic regression model were then used to generate the ROC curve for the combined model. Notably, incorporating additional independent risk factors improved the predictive model, increasing the AUC to 0.925 (95% CI: 0.895–0.949), which significantly outperformed 1,25(OH)2D alone (0.818 vs. 0.925, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

ROC curve illustrating the diagnostic performance of serum 1,25(OH)2D concentration for identifying significant CAD in the study cohort. The calculated AUC was 0.818 (95% confidence interval: 0.777–0.855). The best cut-off value for 1,25(OH)2D was determined to be ≤16.6 pg/mL, yielding a sensitivity of 73.3% and specificity of 83.5%. When additional independent risk variables—such as age, tobacco use, diabetes, hypertension, and LDL cholesterol—were included in the predictive model, the AUC rose to 0.925 (95% CI: 0.895–0.949), indicating a significantly better performance compared to using 1,25(OH)2D alone (0.818 vs. 0.925, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

Conventional strategies for controlling cardiovascular risk factors, which have demonstrated efficacy in the general population, have shown only limited effectiveness in individuals with CKD [3]. Gaining a more comprehensive understanding of nontraditional contributors to cardiovascular disease, particularly those that emerge in the early stages of CKD, may facilitate the development of novel therapeutic interventions. Among these factors, vitamin D deficiency is commonly observed in CKD patients, as evidenced by decreased serum concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D and 25(OH)D. Notably, suboptimal vitamin D levels have been associated with an elevated risk of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in CKD, a trend that parallels observations in the general population [6,7]. Given this context, our study investigates the link between vitamin D levels and the occurrence and severity of CAD in CKD patients. In an analysis of 398 individuals undergoing CAG, we identified a significant and independent correlation between serum 1,25(OH)2D levels—and not 25(OH)D concentrations—and both the presence and extent of CAD. This association remained robust across various patient subgroups, independent of established CAD risk factors such as age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and LDL cholesterol levels. These findings build upon previous studies highlighting an independent association between vitamin D status and cardiovascular disease in CKD patients.

The key conclusion of our study is that lower serum 1,25(OH)2D levels independently correlate with both the presence and severity of CAD in CKD patients. Several previous studies have explored the connection between vitamin D deficiency and CAD in populations without CKD. Investigations by Akin et al., Liew et al., and Verdoia et al. have demonstrated an association between reduced serum 25(OH)D levels and the presence or extent of CAD in individuals undergoing CAG [8,9,14]. Similarly, Joergensen et al. reported a link between low 25(OH)D levels and asymptomatic CAD in high-risk type 2 diabetes patients [10], while Somuncu et al. found that 25(OH)D deficiency serves as an independent predictor of severe CAD in individuals with myocardial infarction [12]. Unlike these prior studies, which focused on 25(OH)D, our research specifically examined the association between 1,25(OH)2D and CAD, with a particular emphasis on CKD patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the relationship between 1,25(OH)2D levels and CAD in this patient population.

Our study demonstrated an independent association between serum 1,25(OH)2D levels and both the presence and severity of CAD, even after adjusting for major traditional risk factors. This suggests that low serum 1,25(OH)2D levels may serve as nontraditional risk factors contributing directly to CAD development in CKD patients. However, the precise pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this association remain incompletely understood. Several potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain this relationship. Atherosclerosis, a key driver of CAD, is closely linked to inflammation, and vitamin D is thought to exert protective effects against CAD by modulating the inflammatory response [15,16,17]. Specifically, vitamin D reduces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to decreased CRP levels and limiting macrophage-derived foam cell formation, a critical step in atherosclerosis progression [16,17,18]. Beyond its anti-inflammatory actions, 1,25(OH)2D is thought to impact lipid metabolism by inhibiting LDL uptake in macrophages, achieved through the suppression of scavenger receptor expression on their surfaces [17]. In addition to atherosclerosis, vascular calcification is another frequent pathological change observed in atherosclerotic coronary artery stenosis, with almost all angiographically significant lesions exhibiting some level of calcification [8,19]. While our study did not directly measure coronary artery calcification, previous studies have suggested that vitamin D deficiency may increase the risk of developing coronary calcification [20]. Collectively, our results imply that 1,25(OH)2D deficiency in CKD patients may promote CAD progression by enhancing both atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. Further research is needed to clarify the precise mechanisms behind this association in CKD patients.

In patients with CKD, systemic inflammation and vascular calcification represent key, interrelated mechanisms contributing to accelerated atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. CKD is characterized by a chronic pro-inflammatory state driven by uremic toxins, oxidative stress, and immune dysregulation, all of which promote endothelial dysfunction and plaque formation. In this context, reduced levels of 1,25(OH)2D may further exacerbate inflammation by increasing pro-inflammatory cytokine production and impairing macrophage and endothelial cell function. In addition, disturbances in mineral metabolism commonly observed in CKD, including phosphate retention and secondary hyperparathyroidism, contribute to vascular smooth muscle cell osteogenic transformation and vascular calcification. Although coronary artery calcification was not directly assessed in this study, the observed association between low 1,25(OH)2D levels and coronary artery disease severity may reflect, at least in part, the combined effects of enhanced inflammation and accelerated vascular calcification in CKD.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an independent association between serum 1,25(OH)2D levels and both the presence and severity of coronary artery disease specifically in patients with CKD. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on 25(OH)D, our findings highlight the potential clinical relevance of assessing the biologically active form of vitamin D in this population. From a clinical perspective, serum 1,25(OH)2D may serve as a non-traditional biomarker for cardiovascular risk assessment in patients with CKD. Measurement of 1,25(OH)2D could potentially aid in identifying high-risk individuals who may benefit from closer cardiovascular surveillance or targeted vitamin D-related interventions. In addition, 1,25(OH)2D levels may be useful for monitoring the biological response to active vitamin D supplementation, although prospective studies are required to determine whether such strategies can improve cardiovascular outcomes. While reduced eGFR is a major cardiovascular risk factor in CKD, the independent association of 1,25(OH)2D with coronary artery disease after adjustment for kidney function suggests that this biomarker captures additional CKD-specific pathophysiological information beyond eGFR alone.

Several important considerations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings of this study. First, given the retrospective and cross-sectional design, the observed association between serum 1,25(OH)2D levels and coronary artery disease should be interpreted as associative rather than causal. It is possible that reduced 1,25(OH)2D levels reflect disease severity or systemic inflammation in patients with advanced CAD, raising the possibility of reverse causality. Clarifying the temporal relationship between vitamin D metabolism and CAD progression will require prospective longitudinal studies and randomized controlled trials. Second, the study population consisted of patients with CKD who underwent elective coronary angiography for evaluation of chest pain or suspected myocardial ischemia. Consequently, the cohort may be enriched for individuals with symptomatic or more advanced CAD, and the present findings may not be directly applicable to asymptomatic patients or the broader CKD population. Third, serum 1,25(OH)2D is closely linked to kidney function and parameters of CKD–mineral bone disorder, including phosphate and PTH. Although the association between 1,25(OH)2D levels and CAD remained significant after multivariable adjustment, residual confounding related to kidney disease severity and disordered mineral metabolism cannot be fully excluded. In this context, 1,25(OH)2D may represent not only an independent risk factor but also an integrated biomarker reflecting the overall burden of CKD-related metabolic and vascular disturbances. In addition, CAD severity was assessed using conventional coronary angiography and the Gensini score, which primarily reflect luminal stenosis. In patients with CAD, angiographic findings may underestimate the total atherosclerotic burden due to diffuse disease, heavy vascular calcification, and microvascular dysfunction, which are not adequately captured by luminal assessment alone. Finally, the ROC-derived cut-off value for serum 1,25(OH)2D was intended to demonstrate discriminatory performance within the study population and should be regarded as exploratory. Given potential inter-assay variability and laboratory-specific reference ranges, this threshold should not be interpreted as a basis for clinical decision-making without prospective validation.

Although this study identified a relationship between vitamin D deficiency and CAD in individuals with CKD, it remains uncertain whether vitamin D supplementation can influence the progression or onset of CAD in this population. Previous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have largely failed to demonstrate a significant benefit of vitamin D therapy on CAD-related outcomes, including mortality [21]. However, some studies have suggested a possible protective effect of vitamin D in reducing CAD severity [21]. For instance, Wu et al. explored whether a six-month daily administration of 0.5 µg 1,25(OH)2D could improve CAD severity [22]. Their findings revealed a significant reduction in disease severity, as indicated by a notable decrease in SYNTAX scores (−3.9; p < 0.001). Importantly, this study was the only RCT that specifically evaluated the impact of 1,25(OH)2D administration, the active form of vitamin D, on CAD. Compared to cholecalciferol, this form of vitamin D is more biologically potent and may be better suited for correcting vitamin D insufficiency. Furthermore, our findings demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D, rather than 25(OH)D, was significantly associated with CAD severity, raising the possibility that supplementation with 1,25(OH)2D might have a greater impact on disease progression. Further research is necessary to determine whether treatment with 1,25(OH)2D can positively affect CAD outcomes, including disease severity.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, due to the retrospective design and inclusion of only patients who underwent elective coronary angiography, selection bias cannot be excluded, and the findings may not be generalizable to the broader CKD population. Second, vitamin D measurements were obtained as part of routine clinical practice rather than batch-analyzed samples, which may introduce some degree of assay variability. However, all assays were performed using standardized methods with consistent internal quality control. Third, quantitative coronary artery calcification data were not available; therefore, we were unable to directly evaluate the relationship between 1,25(OH)2D levels and coronary calcification, which may represent one of the proposed mechanistic pathways linking vitamin D deficiency to CAD. Finally, as this was a single-center study, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other populations or healthcare settings, and multicenter prospective studies are warranted to validate our results.

Nevertheless, this study offers several key strengths. First, instead of measuring 25(OH)D levels, we assessed serum 1,25(OH)2D concentrations. Since 1,25(OH)2D is the biologically active form of vitamin D that binds directly to the vitamin D receptor, it provides a more accurate representation of vitamin D’s physiological role, whereas 25(OH)D primarily serves as an indicator of vitamin D storage [5]. Therefore, our findings provide a more direct physiological insight compared to previous studies that focused on 25(OH)D. Second, the multivariable analysis incorporated adjustments for well-established risk factors of CAD, such as age, smoking, diabetes, hypertension and, LDL cholesterol, thereby reinforcing the independent association between 1,25(OH)2D and CAD in CKD patients. Third, beyond identifying this independent correlation, we also determined optimal threshold values for serum 1,25(OH)2D levels that may help predict significant CAD, suggesting its potential role as a biomarker in CKD patients.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that serum 1,25(OH)2D levels are independently associated with both the presence and severity of CAD in patients with CKD. These findings suggest that 1,25(OH)2D may represent a clinically relevant, non-traditional biomarker for cardiovascular risk stratification in this high-risk population. Future prospective studies and randomized controlled trials are warranted to determine whether assessment and targeted modulation of 1,25(OH)2D levels can improve cardiovascular outcomes and inform personalized preventive strategies in patients with CKD.

Funding

This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant ethical guidelines, with approval granted by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital IRB No. 55-2025-105, approval date: 29 August 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Given the retrospective nature of the study, which utilized anonymized clinical data, the IRB waived the requirement for informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. American Society of, Nephrology, European Renal, Association, International Society of, Nephrology Chronic Kidney Disease and the Global Public Health Agenda: An International Consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Tuttle, K.R.; Abdellatif, D.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Fung, W.W.S.; Haris, A.; Hsiao, L.L.; Khalife, M.; Kumaraswami, L.A.; Loud, F.; et al. World Kidney Day Joint Steering Committee. Mind the Gap in Kidney Care: Translating What We Know into What We Do. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 44, e2024E007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Bohm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiological Insights and Therapeutic Options. Circulation 2021, 143, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shroff, G.R.; Carlson, M.D.; Mathew, R.O. Coronary Artery Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Need for a Heart-Kidney Team-Based Approach. Eur. Cardiol. 2021, 16, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervloet, M.G.; Hsu, S.; de Boer, I.H. Vitamin D Supplementation in People with Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2023, 104, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, N.; Campodonico, J.; Milazzo, V.; De Metrio, M.; Brambilla, M.; Camera, M.; Marenzi, G. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Disease: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.; Zelnick, L.R.; Bansal, N.; Brown, J.; Denburg, M.; Feldman, H.I.; Ginsberg, C.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Isakova, T.; Leonard, M.B.; et al. Vitamin D Metabolites and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: The Cric Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e028561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, F.; Ayça, B.; Köse, N.; Duran, M.; Sari, M.; Uysal, O.K.; Karakukcu, C.; Arinc, H.; Covic, A.; Goldsmith, D.; et al. Serum Vitamin D Levels Are Independently Associated with Severity of Coronary Artery Disease. J. Investig. Med. 2012, 60, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, J.Y.; Sasha, S.R.; Ngu, P.J.; Warren, J.L.; Wark, J.; Dart, A.M.; Shaw, J.A. Circulating Vitamin D Levels Are Associated with the Presence and Severity of Coronary Artery Disease but Not Peripheral Arterial Disease in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joergensen, C.; Reinhard, H.; Schmedes, A.; Hansen, P.R.; Wiinberg, N.; Petersen, C.L.; Winther, K.; Parving, H.H.; Jacobsen, P.K.; Rossing, P. Vitamin D Levels and Asymptomatic Coronary Artery Disease in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Elevated Urinary Albumin Excretion Rate. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algowhary, M.; Farouk, A.; El-Deek, H.E.M.; Hosny, G.; Ahmed, A.; Abdelzaher, L.A.; Saleem, T.H. Relationship between Vitamin D and Coronary Artery Disease in Egyptian Patients. Egypt Heart J. 2023, 75, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somuncu, M.U.; Serbest, N.G.; Akgul, F.; Cakir, M.O.; Akgun, T.; Tatar, F.P.; Can, M.; Tekin, A. The Relationship between a Combination of Vitamin D Deficiency and Hyperuricemia and the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease in Myocardial Infarction Patients. Turk Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2020, 48, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goleniewska, B.; Kacprzak, M.; Zielinska, M. Vitamin D Level and Extent of Coronary Stenotic Lesions in Patients with First Acute Myocardial Infarction. Cardiol. J. 2014, 21, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdoia, M.; Schaffer, A.; Sartori, C.; Barbieri, L.; Cassetti, E.; Marino, P.; Galasso, G.; De Luca, G. Vitamin D Deficiency Is Independently Associated with the Extent of Coronary Artery Disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 44, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Liberale, L.; Libby, P.; Montecucco, F. Vitamin D in Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Events. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 2078–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassi, E.; Adamopoulos, C.; Basdra, E.K.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Role of Vitamin D in Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2013, 128, 2517–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardin, M.; Verdoia, M.; Nardin, S.; Cao, D.; Chiarito, M.; Kedhi, E.; Galasso, G.; Condorelli, G.; De Luca, G. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Diseases: From Physiology to Pathophysiology and Outcomes. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, F.L.; Reardon, C.A.; Yoon, D.; Wang, Y.; Wong, K.E.; Chen, Y.; Kong, J.; Liu, S.Q.; Thadhani, R.; Getz, G.S.; et al. Vitamin D Receptor Signaling Inhibits Atherosclerosis in Mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, L.; Brundage, B.; Crouse, J.; Detrano, R.; Fuster, V.; Maddahi, J.; Rumberger, J.; Stanford, W.; White, R.; Taubert, K. Coronary Artery Calcification: Pathophysiology, Epidemiology, Imaging Methods, and Clinical Implications. A Statement for Health Professionals from the American Heart Association. Writing Group. Circulation 1996, 94, 1175–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, I.H.; Kestenbaum, B.; Shoben, A.B.; Michos, E.D.; Sarnak, M.J.; Siscovick, D.S. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels Inversely Associate with Risk for Developing Coronary Artery Calcification. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legarth, C.; Grimm, D.; Kruger, M.; Infanger, M.; Wehland, M. Potential Beneficial Effects of Vitamin D in Coronary Artery Disease. Nutrients 2019, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhu, S.; Li, L. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation as an Adjuvant Therapy in Coronary Artery Disease Patients. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2016, 50, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.