Abstract

Background and Objectives: The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic posed a new challenge to hospital infection prevention measures and to the antimicrobial therapies adopted. The present study aimed to assess the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the dynamics of surgical site infection (SSI) rates and the variations in the microbiological profiles of the SSI. Materials and Methods: A retrospective, single-center study was conducted to examine data from patients who underwent conventional surgical procedures and developed SSI. The study was conducted at the First Surgery Clinic of the “Pius Brinzeu” Clinical Emergency Hospital, Timisoara, Romania. Data from 173 patients were analyzed over six years (from 26 February 2018 to 25 February 2024). The selected time interval was divided into three periods: pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic. Results: During the pandemic, the average patient age was significantly lower than in the other periods. The average length of stay decreased consistently over the six-year study period. Among the 173 patients included in the study, 71.1% had a monobacterial infection, while the remaining 28.9% had infections involving at least two different bacteria. The two most commonly identified bacteria in more than 50% of the cases were Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp. There was a significant decrease in bacterial resistance to levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin over the study period, with resistance dropping from 50% (pre-pandemic) and 53.3% (pandemic) to just 9.1% (post-pandemic). Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic substantially altered the SSI profile in our institution. The temporary increase in SSI frequency during the pandemic was likely related to shifts in surgical case mix and care delivery, rather than decreased infection control performance. Post-pandemic restoration of surgical flow coincided with improved antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, particularly for fluoroquinolones. Microbiological surveillance, the use of infection prevention measures, and robust stewardship initiatives remain essential to maintain these favorable trends and mitigate the emergence of future resistance.

1. Introduction

Surgical Site Infections are among the most common types of Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAI) [1,2,3]. SSIs are known to have not only immediate but also long-term consequences. They often lead to life-threatening complications, prolongation of hospitalization, and an increase in recurrence rate and low survival rates, adding to the overall treatment costs [2,3,4,5].

Along with physical impairment resulting from SSI as a surgical complication, there is also a significant impact on patients’ mental well-being, resulting in anxiety and depression, and ultimately affecting their quality of life [4,6].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition of SSI is the most widely accepted, dividing SSIs into three groups: superficial, deep, and organ site infections [7].

Superficial SSIs occur within 30 days following the surgical procedure. They involve only the skin or subcutaneous tissue at the site of the incision and must meet at least one of the following criteria: purulent drainage from the surgical incision; a positive microbiological culture; or the presence of one or more signs and symptoms of infection, such as tenderness, swelling, heat, or redness [7,8].

Deep SSIs can develop within 30 to 90 days after surgery and involve the fascial and muscular layers. For a deep SSI to be identified, the patient must exhibit one or more of the following: purulent drainage from the deep incision; a deep incision that either spontaneously dehisces or is deliberately opened by a physician, accompanied by a positive microbiological culture from the deep soft tissue; or evidence of infection involving the deep surgical incision [7].

Organ/Space SSI can occur within the first 30 to 90 days after surgery. It affects the tissues of the organ or space manipulated during the procedure and is related to the surgery. A patient may have one or more of the following signs indicating an infection or abscess involving the organ or space tissue: evidence of infection detected through a physical examination, imaging tests, or histopathological analysis; purulent drainage from the organ or space tissue drain; a positive microbiological culture from fluid or tissue in the affected organ or space [7,8].

Different countries have varying rates of SSIs, which are primarily influenced by their level of economic development and overall healthcare conditions. Generally, high-income countries report lower SSI rates compared to low- and middle-income countries. Among all types of surgeries, abdominal surgery has the highest incidence of SSI. Moreover, elective abdominal surgeries tend to have a lower SSI rate than emergency abdominal surgeries [9].

Beyond incidence rates, the clinical burden of SSIs is increasingly shaped by the global rise in antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which complicates therapeutic management and worsens patient outcomes. Regional AMR data from the World Health Organization (WHO) European Region burden analysis (2019) estimated approximately 541,000 deaths associated with bacterial AMR, with the highest resistance burden observed in Eastern and Southern Europe, including Romania. Particularly concerning resistance patterns were reported for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [10]. Several studies conducted in western regions of Romania have identified a higher incidence of infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella spp., alongside a lower incidence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp., albeit with heterogeneous antimicrobial resistance profiles [11,12,13,14]. Isolated Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains were predominantly resistant to cephalosporins, carbapenems, and fluoroquinolones [14,15], while Enterococcus spp. commonly exhibited resistance to cefuroxime, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides but remained susceptible to glycopeptides and linezolid [13]. Notably, certain carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains demonstrated an enhanced capacity for biofilm formation, emphasizing the importance of accurate strain identification and characterization [16].

An often-overlooked contributor to the AMR burden is represented by water-borne microorganisms, which are frequently multidrug-resistant (MDR). Most P. aeruginosa strains isolated from hospital wastewater systems have been identified as carriers of metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) and extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) [17,18]. Additionally, the long-term persistence of MDR organisms on hospital surfaces represents a continuous infection control challenge, with pathogens such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Cutibacterium acnes, and Staphylococcus epidermidis frequently detected across various hospital environments [19].

In this context of rising MDR pathogen prevalence, well-implemented and adequately funded AMR action plans are essential. Addressing limitations in microbiological diagnostic capacity, improving AMR awareness, and strengthening antimicrobial stewardship programs can significantly reduce mortality attributable to antimicrobial resistance [10,20].

Antimicrobial stewardship programs have already demonstrated a substantial impact on reducing the development of multidrug-resistant bacteria and on overall costs of patients’ antiinfective treatment, reducing drug costs, length of stay, and readmission rates [21,22]. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic posed a new challenge to infection prevention measures within hospitals and to the antimicrobial therapies adopted, significantly influencing antimicrobial stewardship programs [23,24].

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted healthcare services worldwide. To safeguard patients and healthcare personnel and prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2, many surgical procedures had to be postponed. In Romania, authorities implemented recommendations from the World Health Organization (WHO), adopting measures similar to those seen in other countries affected by COVID-19 to curb the virus’s rapid transmission [25].

It is estimated that approximately 28.4 million elective surgical procedures were globally canceled during this time period [26,27]. These delays presented both advantages and disadvantages. On the positive side, postponing surgical interventions helped reduce the risk of patients contracting a SARS-CoV-2 infection during the perioperative period, which could have put about half of these patients at risk for developing pulmonary complications after surgery [26]. However, for specific patient groups, such as those with cancer, venous ulcers, or soft-tissue infections, delaying treatment could significantly worsen their conditions and potentially lead to life-threatening complications, considerably reducing the survival rate [28,29,30,31,32].

Conventional open surgical procedures carry the highest risk of infectious complications [8,33]. This six-year retrospective study aims to evaluate the trends in surgical site infections following conventional surgical interventions across three distinct timeframes, including the COVID-19 pandemic. A key objective of the study is to identify shifts in the microbiological profiles and antimicrobial resistance patterns of SSI-associated pathogens, highlighting the importance of ongoing antimicrobial surveillance to optimize postoperative outcomes.

Although previous studies have examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical activity and SSIs, data specifically addressing conventional surgeries and antimicrobial resistance trends before, during, and after the pandemic remain limited. Furthermore, there is a paucity of regional data regarding antimicrobial surveillance of SSIs in Western Romania. By analyzing resistance patterns over six years, this study seeks to provide valuable insights into the local AMR landscape, to support infection control strategies, guide antimicrobial therapy, and ultimately improve patient safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This is a retrospective, single-center, cross-sectional observational study conducted in the First Surgery Clinic, a General Surgery Unit within the Emergency County Hospital of Timișoara, Romania. The hospital is a tertiary referral center providing emergency and elective general surgical care for the city of Timișoara and the surrounding region.

The study analyzed data from inpatients who developed SSIs following conventional surgical procedures performed at the First Surgery Clinic of the “Pius Brînzeu” Clinical Emergency Hospital, Timișoara, Romania. A total of 173 consecutive patients hospitalized between 26 February 2018 and 25 February 2024 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Data extraction and validation were performed over five months (October 2024–February 2025).

The date 26 February 2020 was selected as the index point marking the first confirmed COVID-19 case in Romania, while 8 March 2022 represented the lifting of all pandemic-related restrictions. Based on these epidemiological milestones, patients were stratified into three consecutive observational cohorts for comparative analysis of SSI incidence, clinical outcomes, microbiological characteristics, and antimicrobial resistance profiles:

- Pre-pandemic period: 26 February 2018–25 February 2020;

- Pandemic period: 26 February 2020–25 February 2022;

- Post-pandemic period: 26 February 2022–25 February 2024.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Participant Selection

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they met all of the following criteria:

- Underwent conventional surgical procedures in the clinic during the study period and subsequently developed an SSI.

- Had available microbiological cultures from the surgical wound and corresponding antibiotic susceptibility data (antibiograms).

- Tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 both at admission and throughout hospitalization.

Patients were excluded if they lacked complete microbiological or clinical data, had undergone reoperation during the same admission, or were transferred from another facility after surgery.

All eligible consecutive patients meeting the predefined criteria during the study period were included. No sampling, matching, or randomization procedures were applied.

SSIs were defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria, encompassing superficial, deep incisional, and organ/space infections [7].

2.3. Patient Screening and Hospital Protocol

During the pandemic, all patients scheduled for elective surgery underwent SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) testing using nasopharyngeal swabs in accordance with national and institutional guidelines. Negative RT-PCR results obtained externally within 24 h before admission were accepted, though infrequently used due to cost considerations. Rapid antigen tests were not accepted.

Patients awaiting RT-PCR results were isolated in dedicated rooms, temporarily reducing hospital capacity, as four rooms were reserved exclusively for pre-admission isolation. Patients testing negative were transferred to standard wards for preoperative preparation. In contrast, positive cases were redirected to designated COVID-19 treatment units (moderate/severe cases) or instructed to isolate at home for 14 days (mild/asymptomatic cases).

Following the lifting of restrictions on 8 March 2022, the clinic progressively resumed regular activity, with standard admission and hospitalization protocols reinstated.

2.4. Ethical Approval, Data Collection, and Management

Ethical approval was obtained from the Hospital Ethics Committee (548/23 June 2025), and the investigation adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient data were retrieved from the institutional Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system. Three independent researchers manually extracted data, and all variables were entered into a standardized Microsoft Excel® database (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). To ensure data integrity, two independent researchers performed double data entry, followed by a random cross-check by a third investigator. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus before final database consolidation.

Only patients meeting the predefined inclusion criteria were analyzed. All data were anonymized before analysis and handled in compliance with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR).

Moreover, the reporting of this study is in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies [34].

2.5. Variables Collected

The dataset included the following categories:

- Demographic variables: age, sex, and residence (urban/rural).

- Clinical data: length of hospitalization, interval between admission and wound sampling, surgery type (emergency vs. elective), postoperative ICU admission, and in-hospital mortality.

- Primary diagnosis: categorized into seven groups—abdominopelvic neoplasms, acute abdomen, abdominal wall defects, chronic limb-threatening ischemia, soft-tissue infections, venous leg ulcers, and other conditions.

- Comorbidities: assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [35,36].

- Microbiological findings: pathogen identification, monomicrobial vs. polymicrobial infection status, and antibiotic susceptibility profiles.

The primary outcome of the study was the distribution of surgical site infection–associated pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance patterns across the three predefined study periods (pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic). Secondary outcomes included temporal changes in the frequency of surgical site infections over the study period; patient demographic and clinical characteristics, such as age, sex, comorbidity burden, and primary admission diagnosis; hospitalization-related outcomes, including length of hospital stay, postoperative intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital mortality; as well as the distribution of SSI-associated pathogens according to diagnostic category and type of surgical intervention (emergency versus elective).

2.6. Microbiological Analysis

Bacterial isolates were identified by the hospital’s microbiology laboratory using standard diagnostic methods, and antibiotic susceptibility was interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. Microbiological identification techniques and susceptibility testing protocols remained unchanged throughout the study period, ensuring consistency and comparability across all cohorts.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were summarized as absolute values and percentages (%).

Prior to analysis, the distribution of continuous data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test to determine normality. Based on the outcome, parametric or non-parametric tests were applied following a structured decision process, as outlined in Figure 1 of Sayed AA [37]. For normally distributed data, comparisons between two groups were performed with Student’s t-test, while comparisons involving more than two groups used one-way ANOVA, with Levene’s test for variance homogeneity and Bonferroni post hoc correction where appropriate. For abnormally distributed data, the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test was applied.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test when expected cell counts were <5. Continuous variables were not arbitrarily categorized unless clinically justified. Missing data were managed through listwise deletion, without data imputation. All results were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). No sensitivity or subgroup analyses were performed.

3. Results

After applying the inclusion criteria, 173 patients who developed SSIs following conventional surgical interventions were included in the analysis.

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Across the six-year study period, the case distribution was as follows (Table 1): pre-pandemic: 72 patients (41.6%); pandemic: 48 patients (27.7%); post-pandemic: 53 patients (30.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

The mean age of the study population was 64.6 ± 12.4 years, with no statistically significant variation across the three periods (p = 0.117). However, pairwise comparison revealed that patients in the pandemic cohort were significantly younger than those in the pre-pandemic period (62.29 ± 14.72 vs. 66.92 ± 10.36 years, p = 0.046).

Gender distribution showed no significant differences (p = 0.149), with males representing 43.1%, 60.4%, and 45.3% of cases in the pre-, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods, respectively.

Similarly, the urban-to-rural ratio remained stable (p = 0.907), as did the proportion of patients with Charlson Comorbidity Index > 3 (51.4%, 39.6%, and 41.5%; p = 0.400).

3.2. Hospitalization Parameters

The mean length of hospital stay was 45.16 ± 26.08 days, showing a statistically significant reduction across the three periods (p = 0.003): pre-pandemic: 52.26 ± 28.85 days; pandemic: 44.27 ± 25.63 days; post-pandemic: 36.3 ± 19.21 days.

The time interval between admission and wound sampling did not differ significantly (p = 0.713): pre-pandemic: 16.55 ± 10.78 days; pandemic: 16.75 ± 11.39 days; post-pandemic: 15.18 ± 9.24 days.

3.3. Diagnostic Categories

Admission diagnosis of the patients is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Diagnostic Categories.

Primary admission diagnoses (presented in Table 2) varied significantly among the three study periods (p = 0.012) as follows:

- pre-pandemic: chronic limb-threatening ischemia (36 patients, 50.0%), abdominopelvic neoplasms (14, 19.4%), and abdominal wall defects (8, 11.1%);

- pandemic: chronic limb-threatening ischemia (14, 29.2%), soft-tissue infections (9, 18.8%), and venous leg ulcers (6, 12.5%);

- post-pandemic: chronic limb-threatening ischemia (15, 28.3%), soft-tissue infections (11, 20.8%), and abdominopelvic neoplasms (10, 18.9%).

3.4. Type of Surgical Intervention

Out of all patients, 99 (57.2%) required emergency surgical procedures, while 74 (42.8%) underwent elective surgery.

The distribution differed significantly across periods (p = 0.001): pre-pandemic: 37 patients (51.4%); pandemic: 21 patients (43.8%); post-pandemic: 41 patients (77.4%).

3.5. Microbiological Findings

Of the 173 SSI cases, 123 (71.1%) had monobacterial cultures, and 50 (28.9%) had polymicrobial cultures.

The proportion of monobacterial infections was comparable across the three cohorts (p = 0.737) and did not vary significantly: pre-pandemic: 70.8% (51/72), pandemic: 75.0% (36/48), post-pandemic: 67.9% (36/53).

Table 3 presents the distribution of bacterial species identified across the three periods, regardless of whether infections were mono- or polymicrobial, with percentages reflecting the relative frequency of each bacterial isolate.

Table 3.

Bacterial species distribution among the three studied timeframes.

The most frequently isolated pathogens throughout the study were Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp. (Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis), together accounting for approximately 45% of all isolates. Other common isolates included Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus mirabilis (Table 3).

Bacteria identified with a frequency of less than 2 were not included in the statistical analysis. These bacteria are: Coagulase-negative staphylococci, Corynebacterium striatum, Enterobacter cloacae, Streptococcus constellatus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Proteus vulgaris, Candida albicans, Citrobacter freundii, Bacillus cereus, Streptococcus anginosus, Providencia stuartii, Serratia marcescens, Proteus hauseri, and Providencia rettgeri.

3.6. Pathogen Distribution by Diagnostic Category

Across the entire six-year study period, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp. (Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis) were the most frequently isolated pathogens, together accounting for approximately 45% of all surgical site infections.

Given their high prevalence and clinical relevance, these two bacterial species were selected for a separate comparative analysis of diagnostic distribution across the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods.

Table 4 summarizes the findings in Pseudomonas aeruginosa incidence in all 7 diagnoses, across the three studied periods.

Table 4.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa incidence over the studied periods.

Table 5 summarizes the findings in Enterococcus spp. incidence across the three studied periods.

Table 5.

Enterococcus spp. incidence over the studied periods.

3.7. Antibiotic Resistance Profiles

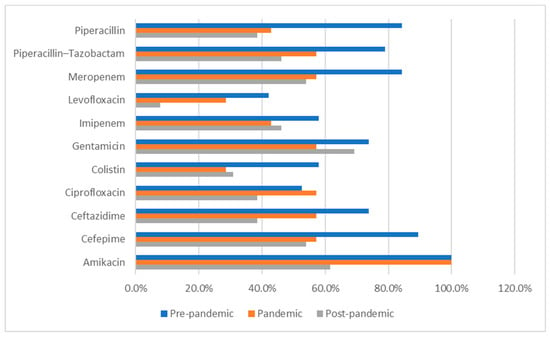

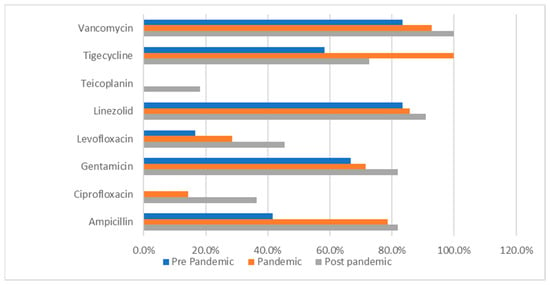

The following data (presented in Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11) summarizes the antibiotic resistance profile for the most frequently encountered bacterial species identified over the study period, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (39 positive cultures) and Enterococcus spp. (38 positive cultures). Their antibiotic susceptibility is presented in Figure 1 (for Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and Figure 2 (for Enterococcus spp.).

Table 6.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic resistance profile.

Table 7.

Enterococcus spp. antibiotic resistance profile.

Table 8.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistance profile.

Table 9.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa intermediate resistance profile.

Table 10.

Enterococcus spp. resistance profile over the three timeframes.

Table 11.

Antibiotic intermediate sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa antibiotic resistance profile across the studied periods. Percentages represent antimicrobial susceptibility rates and refer to the proportion of tested isolates that were susceptible to each antibiotic during each study period.

Figure 2.

Enterococcus spp. antibiotic resistance profile across the studied periods. Percentages represent the proportion of Enterococcus spp. isolates resistant to each antimicrobial agent among the isolates tested in each study period.

Susceptibility to key antibiotics decreased gradually over time, as depicted in Table 6. Although not statistically significant (p > 0.05), clinically relevant changes were noted as follows:

- Amikacin: 100% (pre- and pandemic) → 61.5% (post-pandemic);

- Cefepime: 89.5% → 57.1% → 53.8%;

- Ceftazidime: 73.7% → 57.1% → 38.5%;

- Piperacillin/Tazobactam: 78.9% → 57.1% → 46.2%.

A slight decline in carbapenem susceptibility (imipenem, meropenem) was also observed (Table 6).

Intermediate resistance was most frequent for ceftazidime, piperacillin/tazobactam, and ciprofloxacin during the post-pandemic period (Table 6).

Enterococcus spp. isolates maintained high resistance rates to linezolid (83.3% → 90.9%) and vancomycin (83.3% → 100%), as presented in Table 7 and Figure 2.

Table 10 presents a comparative analysis of the bacterial resistance profile across the 3 timeframes for Enterococcus spp.. It revealed statistically significant differences in the resistance profiles to 2 fluoroquinolones. For ciprofloxacin, the resistance rate was 50.0% in the pre-pandemic period, 53.3% in the pandemic period, and 9.1% in the post–pandemic period (p = 0.030). The same trend was observed for levofloxacin, with the resistance rate decreasing from 50.0% and 53.3% in the first two timeframes to 9.1% in the post-pandemic period (p = 0.030). These results indicate a notable decline in bacterial resistance to fluoroquinolones following the pandemic.

Resistance to beta-lactams (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ampicillin) fluctuated without statistical significance.

The antibiotic intermediate sensitivity is presented in Table 11.

3.8. Clinical Outcomes

After analyzing the collected data, five cases (2.89%) required postoperative ICU hospitalization. In the pre-pandemic period, four patients (5.6%) required ICU postoperative monitoring; during the pandemic, only one patient (2.1%) was moved to the ICU; and post-pandemic, none of the post-surgical patients required monitoring. The results show a significant difference across the three studied periods, but they must be interpreted cautiously due to low representation (frequency < 5).

During the study, five patients died in the postoperative period. In the first period, no deaths were recorded. During the pandemic, three patients (6.3%) died, and after the COVID period, two deaths (3.8%) were recorded. The results show a significant difference between the three studied periods (p = 0.034), but these results must be interpreted cautiously due to the low representation (frequency < 5).

4. Discussion

This six-year retrospective study investigated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence, microbiological profiles, and antimicrobial resistance patterns of SSIs among patients undergoing conventional surgical procedures at a tertiary center in Romania. To eliminate potential confounding factors related to SARS-CoV-2-induced immunosuppression and an increased risk of postoperative complications, patients with a history of or current COVID-19 were excluded from the study [38,39,40,41].

The incidence of SSIs increased significantly during the pandemic and later declined. This rise was likely due to a shift in the types of cases being treated rather than a decrease in aseptic standards. Between 2020 and 2022, elective surgeries were suspended, leading to a predominance of emergency cases such as perforated appendicitis and chronic limb-threatening ischemia, which are associated with a higher risk of SSIs [42]. Similar reports suggest that the increased SSI rates during the pandemic were linked to delayed presentations and a greater number of urgent or contaminated procedures [43,44]. After elective surgeries resumed in March 2022, both the number of SSIs and the length of hospital stays decreased, indicating improved perioperative organization and a return to established infection-prevention protocols.

The age of patients also decreased during the pandemic, likely because older adults avoided hospital care due to fears of SARS-CoV-2 exposure, a trend reported in other studies [45]. The average length of hospital stay decreased after the pandemic, from 52.3 days to 36.3 days. This change aligns with improved perioperative management and more stringent recovery protocols in hospitals. Similar international data indicate that hospital stays were shortened during this time, particularly with the implementation or enhancement of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) measures [46,47,48]. Throughout all three periods studied, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp. were the most common pathogens, collectively accounting for nearly half of the isolates. The high incidence of P. aeruginosa is associated with a preference for moist, ischemic tissues, which are often found in cases of limb-threatening ischemia and chronic ulcers [49,50]. Although some studies indicated lower rates of P. aeruginosa infections during the pandemic [51,52], our findings demonstrate that this pathogen persisted. This underscores the necessity for targeted surveillance in high-risk surgical units.

Recent multicenter surveillance studies and systematic reviews have reported heterogeneous trends regarding the incidence and antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during the COVID-19 pandemic. While some institutions described a transient decline in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa during interwave periods [51,53], others reported increased resistance to carbapenems and fluoroquinolones, particularly in the post-pandemic phase [52,54]. Extensive ecological analyses and meta-analyses further suggest that pandemic-related disruptions amplified regional variability in P. aeruginosa epidemiology rather than producing uniform global trends, with resistance increasing predominantly in settings where antimicrobial stewardship and infection control programs were compromised [55,56].

In contrast to studies reporting a pandemic-associated decline, our data show a persistent presence of P. aeruginosa across all three periods, with no statistically significant reduction during the pandemic. This finding is consistent with reports focusing on high-risk surgical populations and SSI cohorts [57,58] and may be explained by the specific case mix of our cohort, which included a high proportion of patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia, venous leg ulcers, and soft-tissue infections. These conditions provide a favorable microenvironment for P. aeruginosa colonization and biofilm formation and may outweigh the potential impact of intensified infection control measures implemented during the pandemic [43,49].

Taken together, these observations indicate that pandemic-era trends in P. aeruginosa incidence and resistance are highly context-dependent and influenced by underlying patient pathology, environmental persistence, and continuity of antimicrobial stewardship. Our findings, therefore, complement existing literature by highlighting that reductions in P. aeruginosa incidence reported during the pandemic may not be generalizable to surgical units managing predominantly ischemic or chronic wound-related conditions [59,60].

A relative increase in Enterococcus spp. was observed during the pandemic, consistent with the organism’s environmental resilience and tolerance to disinfectants heavily used during this period [55,61,62,63,64]. Post-pandemic patterns suggest a partial return toward baseline microbiological ecology. More specifically, several studies have reported an increased prevalence of Enterococcus spp. during the COVID-19 pandemic, frequently linked to intensified disinfectant use, prolonged hospitalization, and increased exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics [55,61,62,63,64]. Conversely, other reports did not observe significant changes in Enterococcus incidence but described marked shifts in antimicrobial resistance patterns, particularly toward glycopeptides and oxazolidinones [55,63,64].

A significant finding is the marked decline in fluoroquinolone resistance among Enterococcus spp. following the pandemic, with p-values of 0.030 for both ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin. This contrasts with global reports of increasing resistance, often linked to antibiotic overuse in COVID-19 wards [26,65]. Contributing factors to this decline may include improved antimicrobial stewardship and a decrease in the empirical use of fluoroquinolones after the pandemic. However, resistance to vancomycin and linezolid remains high, exceeding 80%, which is consistent with global trends [55].

P. aeruginosa showed a gradual loss of susceptibility to β-lactams (ceftazidime, piperacillin-tazobactam, carbapenems), consistent with international surveillance [57], although differences were not statistically significant. The rise in imipenem resistance reported in other settings underscores the species’ adaptability and the need for continuous local monitoring [51,52,54].

Only 2.9% of patients required postoperative intensive care, and mortality remained low, though small numbers limit definitive conclusions. Notably, extensive international collaborative studies have demonstrated that postoperative mortality was significantly higher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period. The STARSurg and COVIDSurg Collaborative study showed that the adjusted odds of death following surgery were higher during the pandemic, primarily driven by pulmonary complications, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infection could have acted as a major confounding factor for postoperative outcomes, including surgical site infections [66]. This evidence supports our methodological decision to exclude patients with active or prior SARS-CoV-2 infection to minimize confounding and enable a more accurate assessment of SSI-related epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance patterns.

The study’s retrospective, single-center design limits its generalizability. Additionally, the lack of data on operative volumes prevented normalization of the SSI incidence. Reliance on electronic medical records introduces the potential for information bias. Furthermore, wound classification and prophylactic strategies were not analyzed, and the causal link between the COVID-19 pandemic and the observed changes cannot be established. Another limitation is that the predefined study periods may not perfectly reflect real-world surgical activity, as the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical scheduling and hospital workflows may not have aligned precisely with the selected timeframes. Finally, only patients diagnosed with SSIs were included in the analysis, which precluded calculation of SSI subtype rates relative to the total surgical population. Future prospective studies including all surgical patients, regardless of infection status, would allow a more detailed evaluation of temporal trends in SSI subtypes. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the epidemiology of SSIs and trends in resistance across the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods.

The post-pandemic increase in fluoroquinolone susceptibility highlights the importance of structured antimicrobial stewardship. To maintain these improvements, continuous surveillance and adaptive stewardship strategies are necessary. Reinforcing CDC-aligned surgical site infection prevention bundles—such as timely prophylaxis, maintaining normal body temperature, and controlling blood sugar—remains essential [7,67].

These findings further emphasize the need for close and continuous monitoring of surgical site infections and antimicrobial resistance patterns. Our results resonate with reports by Rubulotta et al., who highlighted the role of innovative point-of-care diagnostics (SPOCD) in monitoring infection rates during the COVID-19 pandemic [68]. Their work demonstrated that, even in low-resource settings, the judicious use of diagnostic technology can sustain effective microbiological surveillance and stewardship, enabling timely clinical decision-making and improved infection control strategies.

In this context, reinforcing perioperative antimicrobial stewardship, targeted prophylaxis, antiseptic wound care strategies, and microbiological monitoring remain essential to mitigate a post-pandemic resurgence in SSI. The persistence of resistant Gram-negative pathogens such as P. aeruginosa underscores the importance of sustained surveillance and adaptive stewardship strategies beyond pandemic periods [55].

Future multicenter studies are necessary to validate these findings, connect SSI trends to surgical activity, and assess the durability of post-pandemic reductions in resistance.

5. Conclusions

This six-year retrospective analysis demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the dynamics of SSIs in patients undergoing conventional surgeries.

During the pandemic period (2020–2022), the number of SSIs increased, followed by a decline afterward, reflecting the disruption and subsequent recovery of surgical services. Notably, patients during the pandemic were younger. They had shorter hospital stays, which may be associated with changes in healthcare-seeking behavior and the implementation of stricter inpatient management policies, although demographic and comorbidity profiles remained stable.

The most prevalent pathogens were Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterococcus spp., which together accounted for nearly half of all infections throughout the study periods. Their predominance, particularly in cases of chronic limb-threatening ischemia and soft-tissue infections, highlights the persistence of opportunistic and environment-adapted bacteria in surgical wounds.

Importantly, there was a statistically significant decline in fluoroquinolone resistance among Enterococcus spp. post-pandemic, dropping from over 50% to less than 10% (p = 0.030). This observation coincided with the post-pandemic period and may reflect changes in antimicrobial prescribing practices; however, a causal relationship cannot be established in this observational study.

Although the frequency of emergency surgeries and the severity of cases increased during the pandemic, postoperative ICU admissions and mortality rates remained low, indicating that overall surgical outcomes were maintained despite operational challenges.

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic reshaped the epidemiology of SSIs by altering the mix of surgical cases, bacterial ecology, and patterns of antimicrobial resistance. These findings underscore the need for continuous microbiological surveillance, adaptable infection control measures, and reinforced antibiotic stewardship to sustain the observed improvements in resistance profiles after the pandemic. Future multicenter, prospective studies are needed to validate these trends and to elucidate better the factors underlying changes in resistance patterns in surgical settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V.I.F., A.T., V.B., D.M. and M.M.; methodology, C.V.I.F., V.B., C.M. and M.M.; software, C.V.I.F.; validation, D.M., V.G., M.M. and C.M.; formal analysis, A.T., O.C.F., C.I.C. and C.M.; investigation, C.V.I.F., V.G. and M.M.; resources, C.V.I.F. and C.M.; data curation, C.V.I.F., A.T., V.G. and N.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T., V.B. and N.J.; writing—review and editing, D.M., C.M. and C.V.I.F.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, C.V.I.F.; funding acquisition, C.V.I.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge “Victor Babeș” University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Timișoara for their support in covering the publication costs for this research paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Pius Bbrinzeu Emergency County Clinical Hospital in Timisoara, Romania (548/23 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

As this study was purely retrospective, with no supplementary interventions or personal data collection, the need for additional informed consent was waived. Patients had previously granted consent for the use of their clinical data for scientific purposes at the time of admission.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CDC | The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CI | Confidence intervals |

| EMR | Electronic Medical Record |

| ERAS | Enhanced Recovery After Surgery |

| EU GDPR | European Union General Data Protection Regulation |

| HAI | Hospital-Acquired Infections |

| IBM SPSS | IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| M ± SD | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| SSIs | Surgical site infections |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Gillespie, B.M.; Harbeck, E.; Rattray, M.; Liang, R.; Walker, R.; Latimer, S.; Thalib, L.; Erichsen Andersson, A.; Griffin, B.; Ware, R.; et al. Worldwide incidence of surgical site infections in general surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 488,594 patients. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 95, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.B.; Bosch, W.; O’Horo, J.C.; Girardo, M.E.; Bolton, P.B.; Murray, A.W.; Hirte, I.L.; Singbartl, K.; Martin, D.P. Surgical site infections during the COVID-19 era: A retrospective, multicenter analysis. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2023, 51, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losurdo, P.; Paiano, L.; Samardzic, N.; Germani, P.; Bernardi, L.; Borelli, M.; Pozzetto, B.; de Manzini, N.; Bortul, M. Impact of lockdown for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) on surgical site infection rates: A monocentric observational cohort study. Updat. Surg. 2020, 72, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdewsing, D.R.; Fahmy, N.S.C.; Chen, X.; Keuzetien, Y.K.; Silva, F.A.; Kang, H.; Xu, Y.; Al-Sharabi, A.; Jagdewsing, S.A.; Jagdewsing, S.A. Postoperative Surgical Site and Secondary Infections in Colorectal Cancer Patients With a History of SARS-CoV-2: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e78077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, M.; Jowett, S.; Pinkney, T.; Brocklehurst, P.; Morton, D.G.; Abdali, Z.; Roberts, T.E. Surgical site infection and costs in low- And middle-income countries: A systematic review of the economic burden. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, S.C.; Dumitru, C.Ș.; Radu, D. Measuring the Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Venous Disease before and Short Term after Surgical Treatment—A Comparison between Different Open Surgical Procedures. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC; Ncezid; DHQP. Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/ps-analysis-resources/ImportingProcedureData.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Bhakta, A.; Tafen, M.; Glotzer, O.; Ata, A.; Chismark, A.D.; Valerian, B.T.; Stain, S.C.; Lee, E.C. Increased Incidence of Surgical Site Infection in IBD Patients. Dis. Colon Rectum 2016, 59, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Lv, P.; Peng, X.; Wu, C.; Ren, J.; Wang, P. Prospective multicenter study on the incidence of surgical site infection after emergency abdominal surgery in China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. The burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in the WHO European region in 2019: A cross-country systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e897–e913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatian, O.; Balasoiu, A.T.; Balasoiu, M.; Cristea, O.; Docea, A.O.; Mitrut, R.; Spandidos, D.A.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Bancescu, G.; Calina, D. Antimicrobial resistance in bacterial pathogens among hospitalised patients with severe invasive infections. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 4499–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călina, D.; Docea, A.O.; Roșu, L.; Zlatian, O.; Roșu, A.F.; Anghelina, F.; Rogoveanu, O.; Arsene, A.L.; Nicolae, A.C.; Drăgoi, C.M.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance development following surgical site infections. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaha, D.C.; Bungau, S.; Uivarosan, D.; Tit, D.M.; Maghiar, T.A.; Maghiar, O.; Pantis, C.; Fratila, O.; Rus, M.; Vesa, C.M. Antibiotic consumption and microbiological epidemiology in surgery departments: Results from a single study center. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mişcă, O.M.; Maghiar, P.B.; Mişcă, L.C.; Totolici, B.D.; Neamţu, C.; Faur, I.F.; Dragomirescu, L.; Chioibaş, D.R.; Mişcă, C.D.; Neamţu, A.A.; et al. Resistance phenotypes of bacterial strains isolated from patients admitted to surgical wards. Chirurgia 2025, 120, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisavu, L.; Chisavu, F.; Marc, L.; Mihaescu, A.; Bob, F.; Licker, M.; Ivan, V.; Schiller, A. Bacterial resistances and sensibilities in a tertiary care hospital in Romania—A retrospective analysis. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vintilă, C.; Coșeriu, R.L.; Mare, A.D.; Ciurea, C.N.; Togănel, R.O.; Simion, A.; Cighir, A.; Man, A. Biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance profiles in carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative rods—A comparative analysis between screening and pathological isolates. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Barbu, I.C.; Popa, L.I.; Pîrcălăbioru, G.G.; Popa, M.; Măruțescu, L.; Niță-Lazar, M.; Banciu, A.; Stoica, C.; Gheorghe, Ș.; et al. Temporo-spatial variations in resistance determinants and clonality of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from Romanian hospitals and wastewaters. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennebique, A.; Monge-Ruiz, J.; Roger-Margueritat, M.; Morand, P.; Terreaux-Masson, C.; Maurin, M.; Mercier, C.; Landelle, C.; Buelow, E. The hospital sink drain biofilm resistome is independent of the corresponding microbiota, the environment and disinfection measures. Water Res. 2025, 284, 123902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MetaSUB Consortium; Chng, K.R.; Li, C.; Bertrand, D.; Ng, A.H.Q.; Kwah, J.S.; Low, H.M.; Tong, C.; Natrajan, M.; Zhang, M.H.; et al. Cartography of opportunistic pathogens and antibiotic resistance genes in a tertiary hospital environment. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery. Microbiology testing capacity and antimicrobial drug resistance in surgical-site infections: A post-hoc, prospective, secondary analysis of the FALCON randomised trial in seven low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1816–e1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaznadar, O.; Khaznadar, F.; Petrovic, A.; Kuna, L.; Loncar, A.; Omanovic Kolaric, T.; Mihaljevic, V.; Tabll, A.A.; Smolic, R.; Smolic, M. Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Stewardship: Before, during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 14, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.; Mahida, N.; Gray, J. Antimicrobial stewardship: A COVID casualty? J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 401–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshenawy, R.A.; Umaru, N.; Alharbi, A.B.; Aslanpour, Z. Antimicrobial stewardship implementation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in acute care settings: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahida, N.; Winzor, G.; Wilkinson, M.; Jumaa, P.; Gray, J. Antimicrobial stewardship in the post COVID-19 pandemic era: An opportunity for renewed focus on controlling the threat of antimicrobial resistance. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 127, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enciu, B.G.; Tănase, A.A.; Drăgănescu, A.C.; Aramă, V.; Pițigoi, D.; Crăciun, M.-D. The COVID-19 Pandemic in Romania: A Comparative Description with Its Border Countries. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assadian, O.; Golling, M.; Krüger, C.M.; Leaper, D.; Mutters, N.T.; Roth, B.; Kramer, A. Surgical site infections: Guidance for elective surgery during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic—International recommendations and clinical experience. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 111, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, A.S.D.; Weerasinghe, C.; Gokul, K.; Babu, B.H.; Ainsworth, P. Prospects of ERAS (Enhanced Recovery after Surgery) Protocols in the Post-Pandemic Era. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, e443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, M.; Sartelli, M.; Weigand, M.A.; Doppstadt, C.; Hecker, A.; Reinisch-Liese, A.; Bender, F.; Askevold, I.; Padberg, W.; Coccolini, F.; et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on emergency surgery services: A multinational survey among WSES members. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, D.; Socea, B.; Badiu, C.D.; Tudor, C.; Balasescu, S.A.; Dumitrescu, D.; Trotea, A.M.; Spataru, R.I.; Vancea, G.; Dascalu, A.M.; et al. Acute surgical abdomen during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical and therapeutic challenges. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, S.C.; Dumitru, C.Ș.; Fakhry, A.M.; Ilijevski, N.; Pešić, S.; Petrović, J.; Crăiniceanu, Z.P.; Murariu, M.-S.; Olariu, S. Bacterial Species Involved in Venous Leg Ulcer Infections and Their Sensitivity to Antibiotherapy—An Alarm Signal Regarding the Seriousness of Chronic Venous Insufficiency C6 Stage and Its Need for Prompt Treatment. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Siegel, J.B.; Mahvi, D.A.; Zhang, B.; Mahvi, D.M.; Camp, E.R.; Graybill, W.; Savage, S.J.; Giordano, A.; Giordano, S.; et al. What Is Elective Oncologic Surgery in the Time of COVID-19? A Literature Review of the Impact of Surgical Delays on Outcomes in Patients with Cancer. Clin. Oncol. Res. 2020, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, S.-C.; Matei, M.; Anghel, F.M.; Olariu, A.; Olariu, S. Great saphenous vein giant aneurysm. Acta Phlebol. 2022, 23, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, S.C.; Radu-Teodorescu, D.; Murariu, M.S.; Dumitru, C.A.; Olariu, S. Cryostripping Versus Conventional Safenectomy in Chronic Venous Disease Treatment: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Chirurgia 2024, 119, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STROBE Statement. STROBE Checklists for Observational Studies. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/checklists/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Roffman, C.E.; Buchanan, J.; Allison, G.T. Charlson Comorbidities Index. J. Physiother. 2016, 62, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A critical review of clinimetric properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, A.A. The Preparation of Future Statistically Oriented Physicians: A Single-Center Experience in Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2024, 60, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Pastor, A.; Moreno-Pérez, O.; Lobato-Martínez, E.; Valero-Sempere, F.; Amo-Lozano, A.; Martínez-García, M.-Á.; Merino, E.; Sanchez-Martinez, R.; Ramos-Rincón, J.-M. Association between Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) and Clinical Presentation and Outcomes in Older Inpatients with COVID-19. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keske, Ş.; Altunok, E.S.; Azak, E.; Gülten, E.; Gülen, T.A.; Hatipoğlu, Ç.A.; Asan, A.; Korkmaz, D.; Kaçmaz, B.; Kızmaz, Y.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Surgical Site Infections: A Multicenter Study Evaluating Incidence, Pathogen Distribution, and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2025, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, A.; Büyükkasap, A.Ç.; Altınier, S.; Gobut, H.; Kubat, Ö.; Yıldız, P.A.; Erdem, M.; Demir, Ö.; Şahin, M.; Çolak, O. The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Surgical Site Infections after Abdominal Surgery. Med. Sci. Int. Med. J. 2023, 12, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danwang, C.; Bigna, J.J.; Tochie, J.N.; Mbonda, A.; Mbanga, C.M.; Nzalie, R.N.T.; Guifo, M.L.; Essomba, A. Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infection after Appendectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mojtahedi, M.F.; Sepidarkish, M.; Almukhtar, M.; Eslami, Y.; Mohammadianamiri, F.; Behzad Moghadam, K.; Rouholamin, S.; Razavi, M.; Jafari Tadi, M.; Fazlollahpour-Naghibi, A.; et al. Global Incidence of Surgical Site Infections following Caesarean Section: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 139, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pararas, N.; Pikouli, A.; Papaconstantinou, D.; Bagias, G.; Nastos, C.; Pikoulis, A.; Dellaportas, D.; Lykoudis, P.; Pikoulis, E. Colorectal Surgery in the COVID-19 Era: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, Y.; Tsujimoto, H.; Sugasawa, H.; Mochizuki, S.; Okamoto, K.; Kajiwara, Y.; Shinto, E.; Takahata, R.; Kobayashi, M.; Fujikura, Y.; et al. How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Gastrointestinal Surgery for Malignancies and Surgical Infections? Nagoya J. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Maswime, S. Mitigating the Risks of Surgery during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet 2020, 396, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, A.A.; Kartha, A.B.; Masoodi, N.A.; Azad, A.M.; Asaad, N.A.; Alhomsi, M.U.; Saleh, H.A.H.; Bertollini, R.; Abou-Samra, A.-B. Hospital Admission Rates, Length of Stay, and In-Hospital Mortality for Common Acute Care Conditions in COVID-19 vs. Pre-COVID-19 Era. Public Health 2020, 189, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeates, E.O.; Grigorian, A.; Schellenberg, M.; Owattanapanich, N.; Barmparas, G.; Margulies, D.; Juillard, C.; Garber, K.; Cryer, H.; Tillou, A.; et al. Decreased Hospital Length of Stay and Intensive Care Unit Admissions for Non-COVID Blunt Trauma Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Surg. 2022, 224, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.; Scheib, S. Advantages of, and Adaptations to, Enhanced Recovery Protocols for Perioperative Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheus, G.G.; Chamoun, M.N.; Khosrotehrani, K.; Sivakumaran, Y.; Wells, T.J. Understanding the Pathophysiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Colonization as a Guide for Future Treatment for Chronic Leg Ulcers. Burn. Trauma 2025, 13, tkae083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivanmaliappan, T.S.; Sevanan, M. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Diabetes Patients with Foot Ulcers. Int. J. Microbiol. 2011, 2011, 605195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coșeriu, R.L.; Vintilă, C.; Mare, A.D.; Ciurea, C.N.; Togănel, R.O.; Cighir, A.; Simion, A.; Man, A. Epidemiology, Evolution of Antimicrobial Profile and Genomic Fingerprints of Pseudomonas aeruginosa before and during COVID-19: Transition from Resistance to Susceptibility. Life 2022, 12, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, P.; Bukarica, L.G.; Stevanovic, P.; Vitorovic, T.; Bukumiric, Z.; Vucicevic, O.; Milanov, N.; Zivanovic, V.; Bukarica, A.; Gostimirovic, M. Increased Antimicrobial Consumption, Isolation Rate, and Resistance Profiles of Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii during the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Tertiary Healthcare Institution. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altorf-van der Kuil, W.; Wielders, C.C.H.; Zwittink, R.D.; de Greeff, S.C.; Dongelmans, D.A.; Kuijper, E.J.; Notermans, D.W.; Schoffelen, A.F. Study Collaborators ISIS-AR Study Group. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Prevalence of Highly Resistant Microorganisms in Hospitalised Patients in the Netherlands, March 2020 to August 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28, 2300152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serretiello, E.; Manente, R.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Folliero, V.; Iervolino, D.; Casolaro, V.; Perrella, A.; Santoro, E.; Galdiero, M.; Capunzo, M.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, B.J.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Leung, V.; So, M.; Kwan, A.T.H.; Portnoff, J.S.; Bertagnolio, S.; Raybardhan, S.; MacFadden, D.R.; Daneman, N. Antibiotic resistance associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meschiari, M.; López Lozano, J.M.; Medioli, F.; Bacca, E.; Sarti, M.; Cancian, L.; Bertrand, X.; Sauget, M.; Rosolen, B.; Bingham, G.C. A time-series analysis approach to quantify change in incidence and antimicrobial resistance of clinical isolates during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicentre cross-national ecological study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 1500–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.-N.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chang, L.-L.; Lai, C.-H.; Lin, H.-L.; Lin, H.-H. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients with Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Bacteremias in the Emergency Department. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2011, 6, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Tong, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Luo, Y. Proportions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Anti-microbial-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa among Patients with Surgical Site Infections in China: A Systematic Review and Me-ta-Analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2024, 11, ofad647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Ong, N.Y.; Lee, D.Y.X.; Yau, C.E.; Lim, Y.L.; Kwa, A.L.H.; Tan, B.H. Trends in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) Bacteremia during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongiovanni, M.; Barda, B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bloodstream Infections in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toc, D.A.; Mihăilă, R.M.; Botan, A.; Bobohalma, C.N.; Risteiu, G.A.; Simut-Cacuci, B.N.; Steorobelea, B.; Troancă, S.; Junie, L.M. Enterococcus and COVID-19: The Emergence of a Perfect Storm? Int. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, A.A.; Yılmaz, Ş. Antibiotic Consumption in the Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic, Distribution of Bacterial Agents and Antimicrobial Resistance: A Single-Center Study. J. Surg. Med. 2021, 5, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagadinou, M.; Michailides, C.; Chatzigrigoriadis, C.; Erginousakis, I.; Avramidis, P.; Amerali, M.; Tasouli, F.; Chondroleou, A.; Skintzi, K.; Spiliopoulou, A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus bloodstream infections: A six-year study in Western Greece. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1656334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önal, U.; Tüzemen, Ü.; Kazak, E.; Gençol, N.; Souleiman, E.; İmer, H.; Heper, Y.; Yılmaz, E.; Özakın, C.; Ener, B.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare-associated infections, antibiotic resistance and consumption rates in intensive care units. Infez. Med. 2023, 31, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righi, E.; Lambertenghi, L.; Gorska, A.; Sciammarella, C.; Ivaldi, F.; Mirandola, M.; Sartor, A.; Tacconelli, E. Impact of COVID-19 and antibiotic treatments on gut microbiome: A role for Enterococcus spp. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STARSurg Collaborative; COVIDSurg Collaborative. Death following pulmonary complications of surgery before and during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 108, 1448–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Romero, F.J.; Fernández-Prada, M.; Navarro-Gracia, J.F.; Ruiz-Ruiz, A.; López-González, Á.A. Prevención de la infección de sitio quirúrgico: Análisis y revisión narrativa de las guías de práctica clínica. Cir. Esp. 2017, 95, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubulotta, F.; Soliman-Aboumarie, H.; Filbey, K.; Geldner, G.; Kuck, K.; Ganau, M.; Hemmerling, T.M. Technologies to optimize the care of severe COVID-19 patients for health care providers challenged by limited resources. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.