Comparative Evidence on Negative Pressure Therapy and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review of Independent Effectiveness and Clinical Applicability

Abstract

1. Introduction

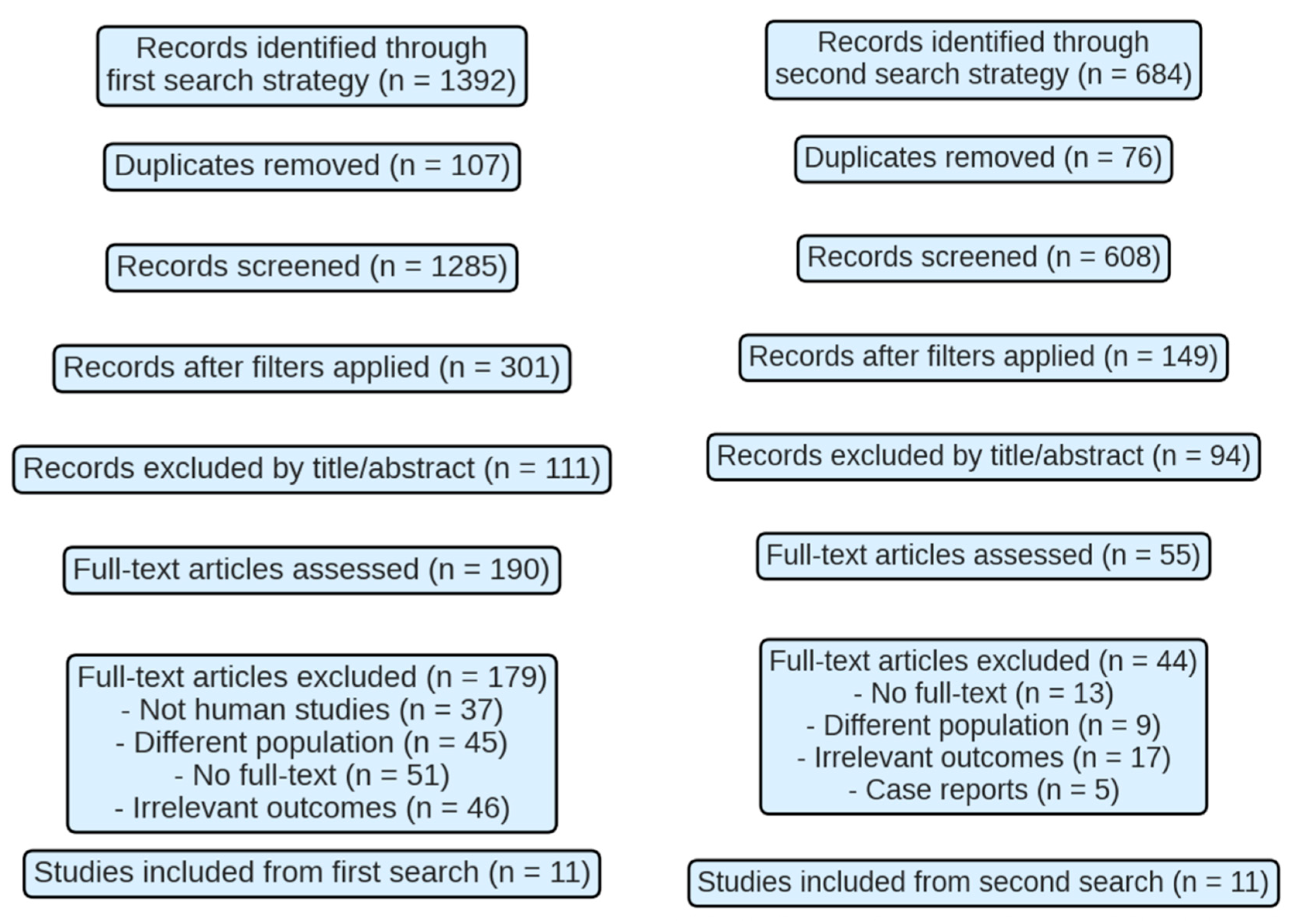

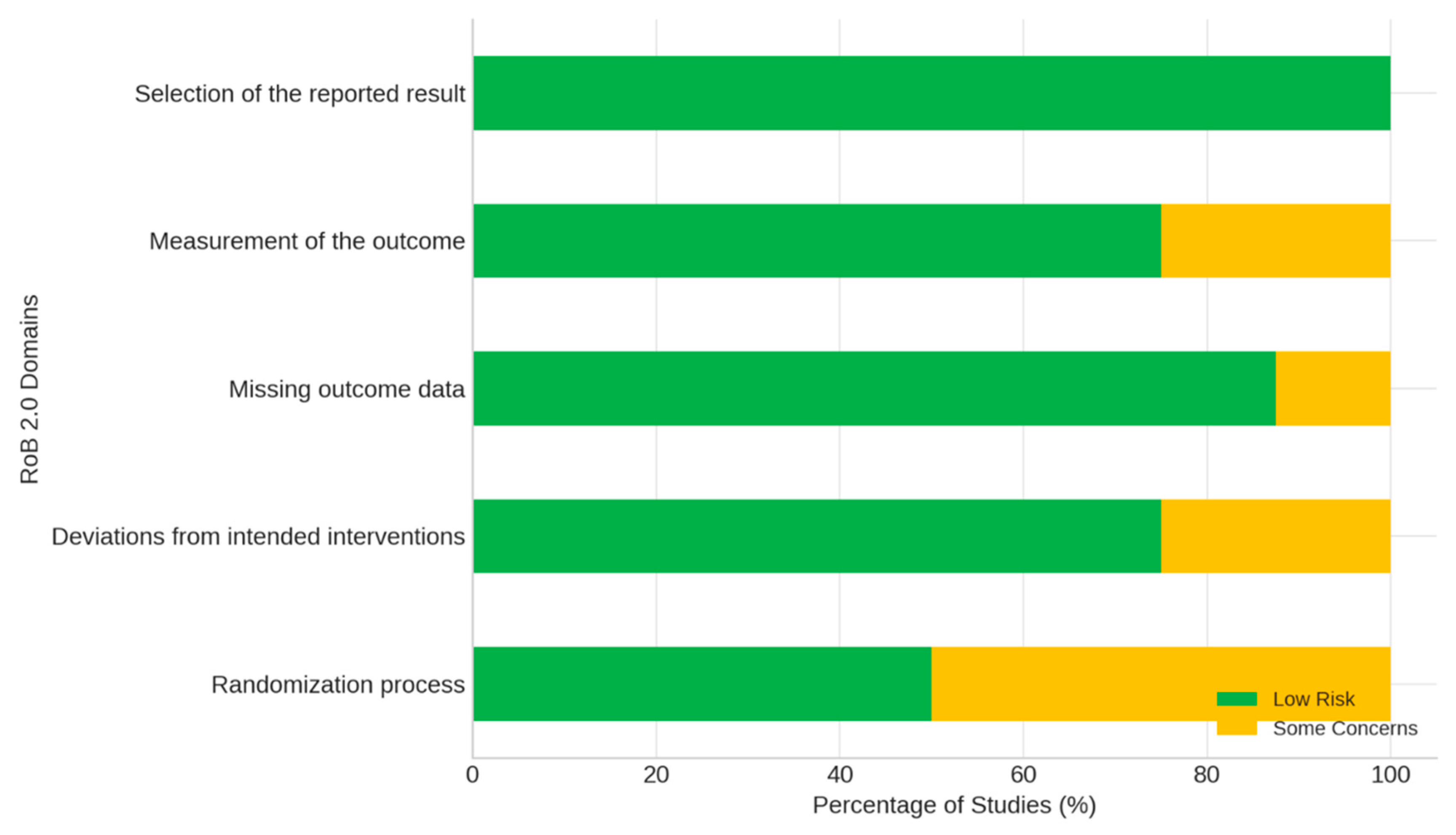

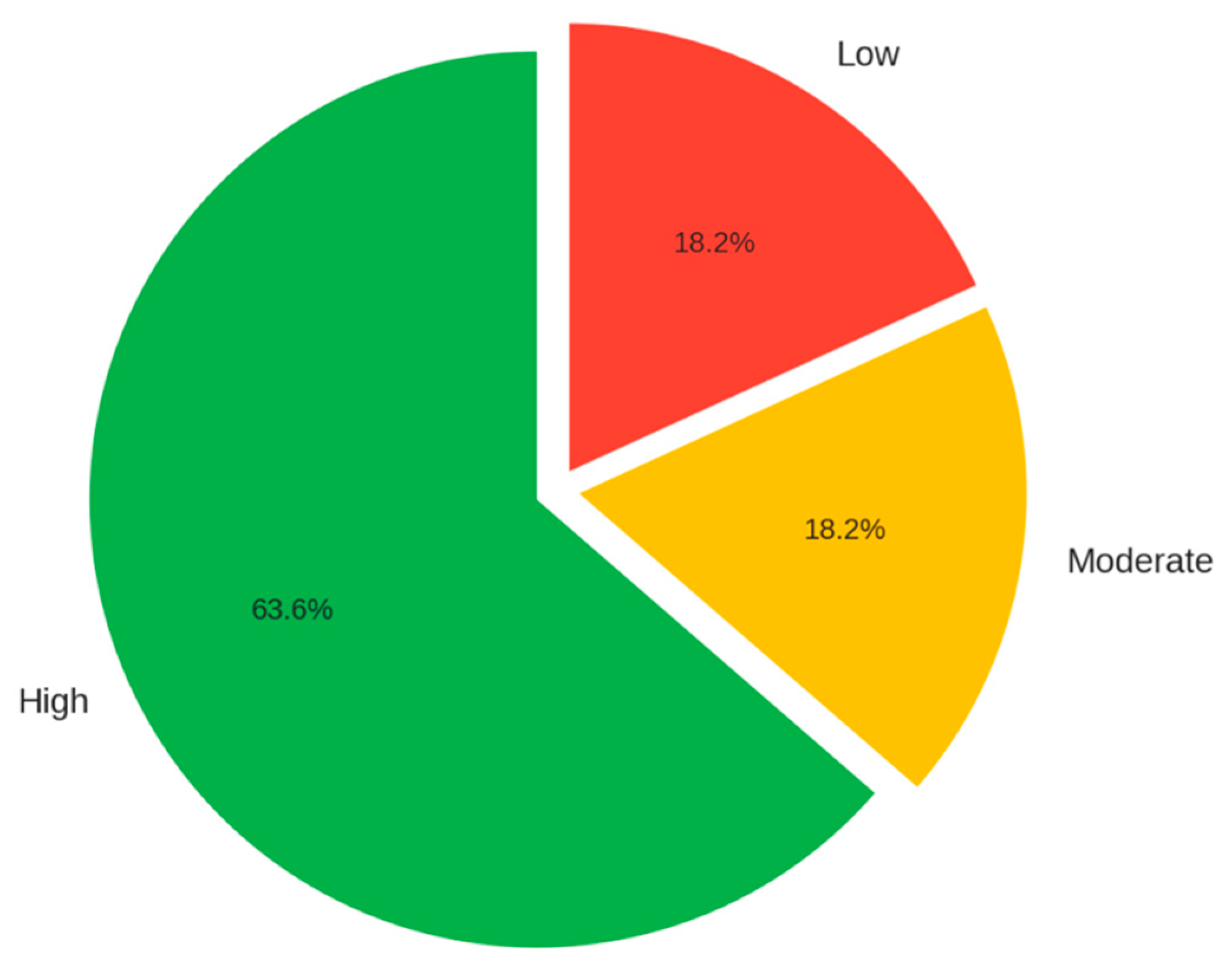

2. Methodology

| Element | Description |

| P (Population) | Patients with diabetes mellitus presenting with active diabetic foot ulcers. |

| I (Intervention) | NPWT or HBOT. |

| C (Comparison) | Conventional treatment. Direct comparison between NPWT and HBOT was not possible due to absence of eligible head-to-head studies. |

| O (Outcomes) | Healing rate, reduction in complications, and improvement in quality of life. |

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Future studies should focus on:

- Standardizing treatment protocols for both NPWT and HBOT.

- Conducting large-scale randomized controlled trials with long-term follow-up.

- Evaluating cost-effectiveness and quality-of-life outcomes.

- Exploring the molecular and immunologic mechanisms behind treatment efficacy.

- Investigating combination therapies and personalized approaches based on wound etiology and patient profile.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Zhong M et al. [33] | Wu Y et al. [34] | Seidel D et al. [35] | Lavery LA et al. [36] | Chen CY et al. [37] | El-Deen HAB et al. [38] | Kumar A et al. [39] | Nik Hisamuddin NAR et al. [40] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1: Bias in the randomization process | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D2: Bias due to deviations from the intended interventions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D3: Bias due to missing outcome data | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D4: Bias in outcome measurement | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D5: Bias in the selection of the reported outcome | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Overall assessment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chen L et al. [23] | Dalmedico MM et al. [24] | Liu Z et al. [25] | Elraiyah T et al. [26] | Brouwer RJ et al. [27] | Chen HR et al. [28] | OuYang H et al. [29] | Sharma R et al. [30] | Kranke P et al. [32] | Moreira DA Cruz DL et al. [31] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1: PICO Question | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| D2: Pre-established Method | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D3: Justification of Study Designs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D4: Search Strategy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D5: Selection of Studies in Duplicate | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D6: Data Extraction in Duplicate | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D7: List and Justification of Excluded Studies | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D8: Description of Included Studies | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D9: Assessment of Risk of Bias | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D 10: Sources of Funding for Studies | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| D11: Statistical Methods in Meta-Analysis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D12: Impact of Bias in Meta-Analysis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D13: Consideration of Bias in Interpretation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D14: Explanation of Heterogeneity | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D15: Research on Publication Sessions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D16: Conflict of Interest and Funding | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Confidence | Medium | High | High | High | High | Medium | High | High | High | High |

| García-Oreja S et al. [21] | Lázaro-Martínez JL et al. [22] | Palomar-Llatas F et al. [41] | Lavery LA et al. [42] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1: Bias due to confounding factors | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D2: Bias due to participant selection | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D3: Bias in the classification of interventions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D4: Bias due to deviations from the planned interventions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D5: Bias due to missing data | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D6: Bias in the measurement of results | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| D7: Bias in the selection of the reported outcome | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Overall assessment | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Author/Year | Objective | Key Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen L, Zhang S, Da J, Wu W, Ma F, Tang C, Li G, Zhong D, and Liao B/2021 [23] | The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers (DF). | Data were collected from 9 randomized controlled trials (943 patients) comparing NPWT (intervention group) with conventional wound care (control group) in patients with DF. | NPWT significantly accelerates wound healing and reduces the time to granulation tissue formation compared with conventional treatment, without increasing the incidence of adverse events or the amputation rate. |

| Zhong M, Guo J, Qahar M, Huang G y Wu J/2024 [33] | The aim of this study was to analyze the efficacy and underlying mechanisms of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and antibiotic-loaded bone cement (ALBC) in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. | In this trial, 28 patients were randomly assigned to two groups: one received NPWT alone (16 individuals) and the other received NPWT combined with ALBC (12 patients). | The group treated with NPWT and ALBC showed a better quality wound bed, with less inflammation, higher collagen quality, and improved vascularization compared to the group that received NPWT alone. In addition, the results indicated a reduction in IL-6 levels and an increase in the expression of healing-related markers. |

| García-Oreja S, Navarro-González Moncayo J, Sanz-Corbalán I, García-Morales EA, Álvaro-Afonso FJ, and Lázaro-Martínez JL/2017 [21] | The objective of this study was to evaluate the complications associated with negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Retrospective observational study. | In this study, 57 patients with diabetic foot ulcers were included. They were treated with surgical debridement and subsequently received NPWT at a pressure of 125 mmHg for 7 to 10 days. | Regarding the results, 48 patients experienced some complication, with perilesional maceration being the most common (49%), followed by bleeding (14%), necrosis (12%), local infection (7%), and pain (2%). Only 9 patients (16%) did not experience any complications. Despite this, 80% of patients had favorable results after treatment. |

| Lázaro-Martínez JL, García-Morales E, Aragón-Sánchez J, García-Álvarez Y, Matilla AC, and Álvaro-Afonso FJ/2014 [22] | The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the postoperative management of severe infections in diabetic foot ulcers. | In After surgical debridement, NPWT was applied to control infection and bleeding. Subsequently, dressings were changed every 48–72 h, assessing the need to continue therapy. Once bone coverage and complete granulation were achieved, moist wound healing was continued. | Regarding the results, of the 42 patients treated, 38 (90.5%) achieved healing after using VAC® therapy, with a mean healing time of 13 weeks. Patients with neuropathic ulcers healed in 13.38 ± 8.77 weeks, while those with neuroischemic ulcers healed in 16.69 ± 8.84 weeks. 9.5% (4 patients) were referred to the hospital due to serious complications. |

| Dalmedico MM, do Rocio Fedalto A, Martins WA, de Carvalho CKL, Fernandes BL e Ioshii SO/2024 [24] | The aim of this study was to analyze the effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the management of diabetic foot ulcers compared to different types of dressings or placebo. | Fourteen randomized controlled trials were analyzed in which NPWT was applied to patients with diabetic foot ulcers using variable pressures, comparing the results with conventional treatments, such as moist dressings or bovine collagen. | The results showed a higher healing rate and a more significant reduction in wound area with NPWT compared to conventional treatments in most cases. Three studies indicated a lower incidence of amputations in the NPWT group, although one did not find a significant difference. Heterogeneity in the studies and variations in the applied pressure limited the generalizability of the results. |

| Palomar-Llatas F, Fornes-Pujalte B, Sierra-Talamantes C, Murillo-Escutia A, Moreno-Hernández A, Díez-Fornes P, Palomar-Fons R, Torregrosa-Valles J, Debón-Vicent L, Marín-Bertolín S, Carballeira-Braña A, Guerrero-Baena/2015 [41] | The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of topical negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in the healing of acute wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, venous ulcers, and pressure ulcers. | The study included a sample of 57 patients who received topical NPWT. The FEDPALLA and EVA scales were used to assess the lesions, and a planimetric and dimensional analysis of each lesion was performed. | Regarding the results, all cases treated with topical TPN showed a considerable reduction in lesion size, as well as improved preparation of the wound bed for epithelialization. This intervention proved beneficial both for patients, by providing them with comfort, and for nursing professionals, by improving the efficiency of direct care management. |

| Wu Y, Shen G, and Hao C/2023 [34] | The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of NPWT and alginate dressings in wound bed preparation prior to skin grafting surgery in patients with chronic diabetic foot ulcers. | In this trial, 103 patients were assigned to two groups: the NPWT group (n = 52) and the control group (alginate dressings, n = 51). Both groups received treatment until healthy granulation tissue was achieved in the wound bed at the time of grafting. Fifty patients in each group were analyzed at the end of the trial. | The group treated with TPN showed shorter surgery time, higher graft survival rates, better blood perfusion, less neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype, compared to the control group. |

| Seidel D, Storck M, Lawall H, Wozniak G, Mauckner P, Hochlenert D, Wetzel-Roth W, Sondern K, Hahn M, Rothenaicher G, Krönert T, Zink K, and Neugebauer E/2020 [35] | The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in patients with diabetic foot ulcers by comparing this therapy with standard wound care. | In this trial, 368 patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio, considering the study site and the severity of the ulcer. | Regarding the results, no significant differences were observed in the wound closure rate or time to closure between the two groups. The wound closure rate was low in both groups. |

| Liu Z, Dumville JC, Hinchliffe RJ, Cullum N, Game F, Stubbs N, Sweeting M, and Peinemann F/2018 [25] | The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) on foot ulcers in people with diabetes mellitus (PD), compared with standard treatment or alternative therapies. | This meta-analysis included 11 randomized controlled trials with 972 participants. Most studies compared NPWT with bandages for the treatment of ulcers in PD, except for one that compared low-pressure NPWT with high-pressure NPWT. | Regarding the results, low-certainty evidence suggests that NPWT may increase the proportion of healed wounds and reduce the healing time of ulcers and postoperative wounds in PD. Furthermore, it has not been determined with certainty whether there are differences between low- and high-pressure NPWT in terms of the number of closed wounds or the occurrence of adverse events. |

| Lavery LA, Murdoch DP, Kim PJ, Fontaine JL, Thakral G, and Davis KE/2014 [42] | The objective of this study was to analyze the effect of low-pressure (80 mmHg) negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) on wound area reduction in diabetic foot ulcers. | In this study, 30 patients with foot ulcers were treated with low-pressure NPWT for up to 5 weeks. | Regarding the results, 43.3% of the patients achieved at least a 50% reduction in wound area after 4 weeks of treatment. |

| Lavery LA, La Fontaine J, Thakral G, Kim PJ, Bhavan K, and Davis KE/2014 [36] | The objective of this study was to compare two negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) methods for wounds: one with 125 mmHg pressure and a polyurethane foam dressing, and the other with 75 mmHg pressure and a silicone-coated dressing | In this trial, 40 patients with diabetic foot wounds were randomly assigned to receive NPWT with two different approaches: 75 mmHg with a silicone dressing or 125 mmHg with a polyurethane foam dressing, for 4 weeks or until surgical closure. | Regarding the results, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of wound healing. Although the proportions varied slightly, the percentage of surgically closed wounds, with a 50% reduction in area or volume, was similar between the 75 mmHg group and the 125 mmHg group. |

| Elraiyah T, Tsapas A, Prutsky G, Domecq JP, Hasan R, Firwana B, Nabhan M, Prokop L, Hingorani A, Claus PL, Steinkraus LW, and Murad MH/2016 [26] | The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), arterial pump devices, and pharmacological agents, such as pentoxifylline, cilostazol, and iloprost, in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. | In this meta-analysis, 18 interventional studies were analyzed, including 9 randomized controlled trials with a total of 1526 patients. | Regarding the results, HBOT combined with conventional treatment showed a higher healing rate and a reduction in major amputations compared to standard therapy. Arterial pump devices promoted healing in small trials, while neither iloprost nor pentoxifylline had a significant impact on the amputation rate. |

| Brouwer RJ, Lalieu RC, Hoencamp R, van Hulst RA, and Ubbink DT/2020 [27] | The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) as a treatment for patients with diabetic foot ulcers and peripheral arterial occlusive disease, particularly in reducing major amputations and other clinical outcomes. | In this meta-analysis, 11 studies (729 patients) were analyzed, including 7 randomized controlled trials, 2 controlled clinical trials, and 2 retrospective cohort studies; 4 were used for quantitative synthesis. Most studies applied a 90 min HBOT protocol, with pressures between 2.2 and 2.8 atmospheres absolute (ATA), administered 5 times per week, with a range of 20 to 60 sessions. | Regarding the results, HBOT reduced major amputations, but there were no significant differences in minor amputations, mortality, or healing time. |

| Chen CY, Wu RW, Hsu MC, Hsieh CJ, and Chou MC/2017 [37] | The aim of this study was to compare the effect of standard care in combination with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) versus standard care alone. | This was a randomized controlled trial. In this trial, 38 patients were randomly assigned to two groups: an experimental group (HBOT plus conventional treatment) and a control group (standard care). The experimental group received HBOT in a hyperbaric chamber for 120 minutes at 2.5 ATA, 5 days a week for 4 weeks. Standard care consisted of nutritional management, debridement, topical therapy, and medication. | Regarding the results, the experimental group achieved a total healing rate of 25% compared to 5.5% in the control group; the amputation rate was 5%, while the standard care group had an amputation rate of 11%. Finally, the TOHB group showed considerable improvements in terms of inflammation indices, blood flow and quality of life, with a significant decrease in HbA1c observed. |

| Chen HR, Lu SJ, Wang Q, Li ML, Chen XC, and Pan BY/2024 [28] | The objective of this study was to assess the efficacy and safety of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) as a treatment for diabetic foot ulcers. | This meta-analysis included 29 randomized controlled trials with a total of 1764 patients divided into two groups: one received HBOT (877 patients) and the other conventional treatment (887 patients). | Regarding the results, the HBOT group showed a considerable increase in the complete ulcer healing rate (46.76% vs. 24.46% with conventional treatment). A decrease in the amputation rate was also observed, but with an increase in the incidence of adverse effects (17.37% vs. 8.27%). |

| El-Deen HAB, Wadee AN, Eraky ZS, Elmasry HM, El-Sayed MS, and Fahmy SM/2023 [38] | The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy of low-intensity laser therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for treating chronic diabetic foot ulcers. | In this randomized controlled trial, 100 patients were randomly assigned to four groups: a) a control group (standard treatment), b) a low-intensity laser therapy group (3 times per week), c) an HBOT group (5 times per week), and d) a combined group (HBOT and low-intensity laser therapy), all for six weeks. | Regarding the results, the groups treated with low-intensity laser therapy, HBOT, and the combined group showed significant improvements in both ulcer area and volume reduction, unlike the control group, which showed no change. The hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) group achieved the greatest reduction in ulcer area, at 89.76%, while the laser treatment stood out with an 89.5% reduction in volume. The combination of both therapies proved no more beneficial than applying each one individually. |

| OuYang H, Yang J, Wan H, Huang J, Yin Y/2024 [29] | The aim of this study is to provide physicians with information on the risks and benefits of different treatment options when choosing different treatment strategies for UPD. | Fifty-seven RCTs involving 4826 patients with diabetic foot ulcers were included. Compared with standard of care (SOC), several interventions—particularly platelet-rich plasma (PRP), hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), topical oxygen therapy (TOT), acellular dermal matrix (ADM), and stem cells—significantly improved complete ulcer healing rates in both direct and network meta-analyses. Combined therapies, especially PRP plus negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), showed superior efficacy over NPWT alone. No significant differences were observed among interventions in ulcer area reduction. PRP and NPWT shortened healing time compared with SOC, with the greatest benefit observed for PRP combined with ultrasonic debridement and NPWT. PRP was also associated with reduced amputation rates and fewer adverse events. Overall ranking favored combination therapies (PRP + NPWT and UD + NPWT), while SOC consistently showed the poorest outcomes. | Due to the particularity of the wound of DFU, the standard of care is not effective, but the new treatment scheme has a remarkable effect in many aspects. And the treatment of DFU is not a single choice, combined with a variety of methods often achieve better efficacy, and will not bring more adverse reactions. |

| Sharma R, Sharma SK, Mudgal SK, Jelly P, and Thakur K/2021 [30] | The objective of this study was to examine the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) as adjunctive treatment for diabetic foot ulcers, comparing its impact on complete ulcer healing and reduction in the amputation rate with standard treatment. | This meta-analysis analyzed 14 studies (12 randomized controlled trials and 2 controlled clinical trials) with a total of 768 participants (384 in the HBOT group and 384 in the standard treatment control group). Standard treatment consisted of glycemic control, antibiotics, and surgical debridement. | Regarding the results, HBOT showed a higher healing rate compared with standard treatment. A considerable reduction in major amputations was observed in the hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) group, while there were no significant differences in minor amputations or the overall amputation rate. However, patients treated with HBOT experienced more adverse events, such as oxygen toxicity, hypoglycemia, cataracts, and barotrauma. No significant differences were observed in mortality or wound area reduction. |

| Kumar A, Shukla U, Prabhakar T, Srivastava D/2020 [39] | The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) as an adjunct to standard therapy and to compare it with standard therapy alone in terms of diabetic foot ulcer healing. | Randomized controlled trial. In this trial, 60 patients were randomly assigned to two groups: group H, which received standard treatment plus HBOT, and group S, which received only standard treatment (glucose control, dressing changes, debridement, and infection control). HBOT was administered at a pressure of 2.4 ATA for 90 minutes, with 6 sessions. | Regarding the results, in group H, 78% of patients healed completely without surgical intervention, while in group S, no patients healed without surgery. Healing time was considerably shorter in group H. Regarding amputations, 7% of individuals in group H required distal amputation, while 11% in group S required proximal amputation. No major amputation was observed in group H. |

| Kranke P, Bennett MH, Martyn-St James M, Schnabel A, Debus SE, Weibel S/2015 [32] | The objective of this study was to analyze the benefits and risks of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in the healing of chronic lower limb ulcers and its impact on amputation reduction. | In this systematic review, 12 randomized clinical trials with 577 patients were analyzed; 281 received HBOT and 267 received control treatment. | Regarding the results, HBOT did not show a statistically significant reduction in the major and minor amputation rates. Several studies reported a significant increase in transcutaneous oxygenation in the HBOT group. A significant reduction in ulcer area and an improvement in quality of life, particularly in physical function and mental health, were also observed. Some studies reported minor adverse effects, such as ear barotrauma, claustrophobia, tinnitus, and headache, but no serious complications were reported. |

| Moreira DA Cruz DL, Oliveira-Pinto J, and Mansilha A/2022 [31] | The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers compared to conventional treatment. | This meta-analysis included a total of 13 randomized controlled trials comparing two groups of patients with ulcers: a conventional treatment group (glycemic control, wound debridement, dressings, pressure offloading, and antibiotic use) and a HBOT group (combination of standard treatment and oxygen therapy). | Regarding the results, patients treated with HBOT showed a lower rate of major amputations; however, no significant differences were found between the groups in minor and total amputations. Compared to standard treatment, HBOT quadrupled the chances of complete ulcer healing, significantly reducing ulcer size within two weeks. |

| Nik Hisamuddin NAR, Wan Mohd Zahiruddin WN, Mohd Yazid B, and Rahmah S/2019 [40] | The objective of this study was to determine the effects of HBOT on the healing of diabetic foot ulcers compared to conventional treatment. | This was a randomized controlled trial. Sixty-two patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and foot ulcers were included and randomly assigned to two groups: an intervention group, which received conventional treatment and HBOT at 2.4 ATA, 90 minutes per session, 5 days a week for 30 sessions; and a control group, which received only conventional treatment. | The intervention group treated with HBOT showed a significantly greater reduction in wound size compared to the control group. Furthermore, HBOT improved tissue oxygenation, promoted angiogenesis and reduced inflammation, favoring faster healing. |

References

- Álvarez-Seijas, E.; Mena-Bouza, K.; Faget-Cepero, O.; Conesa-González, A.I.; Domínguez-Alonso, E. El pie de riesgo de acuerdo con su estratificación. Rev. Cuba. Endocrinol. 2015, 26, 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Castillo-Tirado, R.A.; Fernández-López, J.A.; Del-Castillo-Tirado, F.J. Guía de Práctica Clínica en el pie diabético. Arch. Med. 2014, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bandyk, D.F. The diabetic foot: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 31, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas de P., E.; Molina, R.; Rodríguez, C. Definición, clasificación y diagnóstico de la diabetes mellitus. Rev. Venez. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; International Diabetes Federation. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycaemia; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; ISBN 9241594934. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/definition-and-diagnosis-of-diabetes-mellitus-and-intermediate-hyperglycaemia (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Almaguer-Herrera, A.; Miguel-Soca, P.E.; Será, C.R.; Mariño-Soler, A.L.; Oliveros-Guerra, R.C. Actualización sobre diabetes mellitus. Correo. Científico. Méd. 2012, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK581934/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Lovic, D.; Piperidou, A.; Zografou, I.; Grassos, H.; Pittaras, A.; Manolis, A. The Growing Epidemic of Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 18, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariadoss, A.V.A.; Sivakumar, A.S.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, S.J. Diabetes mellitus and diabetic foot ulcer: Etiology, biochemical and molecular based treatment strategies via gene and nanotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Olmedo, J.M.; Pozo-Mendoza, J.A.; Reina-Bueno, M. Revisión sistemática sobre el impacto de las complicaciones podológicas de la diabetes mellitus sobre la calidad de vida. Rev. Esp. Podol. 2017, 28, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Despaigne, O.L.; Palay Despaigne, M.S.; Rodríguez Cascaret, A.; Neyra Barros, R.M. La diabetes mellitus y las complicaciones cardiovasculares. Medisan 2015, 19, 675–683. [Google Scholar]

- Medrano Jiménez, R.; Gili Riu, M.M.; Díaz Herrera, M.A.; Rovira Piera, A.; Estévez Domínguez, M.; Rodríguez Sardañés, C. Identificar el pie de riesgo en pacientes con diabetes. Med. Fam. SEMERGEN 2022, 48, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ruiz, M.; Torres-González, J.I.; Pérez-Granda, M.J.; Leñero-Cirujano, M.; Corpa-García, A.; Jurado-Manso, J.; Gómez-Higuera, J. Efectividad de la terapia de presión negativa en la cura de úlceras de pie diabético: Revisión sistemática. Rev. Int. Cienc. Podol. 2018, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.M.; Whitehouse, R.W. The Diabetic Foot; Feingold, K.R., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; Endotext; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2023. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK409609/ (accessed on 28 December 2025).

- Gottfried, I.; Schottlender, N.; Ashery, U. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment—From Mechanisms to Cognitive Improvement. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, M.A.; Fraile-Martínez, O.; García-Montero, C.; Callejón-Peláez, E.; Sáez, M.A.; Álvarez-Mon, M.A.; García-Honduvilla, N.; Montserrat, J.; Álvarez-Mon, M.; Bujan, J.; et al. A General Overview on the Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: Applications, Mechanisms and Translational Opportunities. Medicina 2021, 57, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyboer, M.; Sharma, D.; Santiago, W.; McCulloch, N. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: Side Effects Defined and Quantified. Adv. Wound Care 2017, 6, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, J.P.; Snyder, J.; Schuerer, D.J.E.; Peters, J.S.; Bochicchio, G.V. Essentials of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: 2019 Review. Mo. Med. 2019, 116, 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara Goyo, N.; Miriamgeluis Lanzotti, S.; Aracelys Torrealba, A.; Felice, L.G.D. Aplicación de terapia de presión negativa en el manejo de pacientes con heridas complejas. J. Negat. No Posit. Results 2020, 5, 1490–1503. [Google Scholar]

- García-Oreja, S.; Navarro-González-Moncayo, J.; Sanz-Corbalán, I.; García-Morales, E.A.; Álvaro-Afonso, F.J.; Lázaro-Martínez, J.L. Complicaciones asociadas a la terapia de presión negativa en el tratamiento de las úlceras de pie diabético: Serie de casos retrospectiva. Rev. Esp. Podol. 2017, 28, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro-Martínez, J.L.; García-Morales, E.A.; Aragón-Sánchez, F.J.; García-Álvarez, Y.; Matilla, A.C.; Álvaro-Afonso, F.J. Efectividad de la terapia de presión negativa en el manejo postquirúrgico de úlceras de pie diabético complicadas con infección amenazante de la extremidad. Heridas Y Cicatrización 2014, 4, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Da, J.; Wu, W.; Ma, F.; Tang, C.; Li, G.; Zohng, D.; Liao, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 10830–10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmedico, M.M.; do Rocio Fedalto, A.; Martins, W.A.; de Carvalho, C.K.L.; Fernandes, B.L.; Ioshii, S.O. Effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy in treating diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Wounds Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 2024, 36, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Dumville, J.C.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Cullum, N.; Game, F.; Stubbs, N.; Sweeting, M.; Peinemann, F. Negative pressure wound therapy for treating foot wounds in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD010318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elraiyah, T.; Tsapas, A.; Prutsky, G.; Domecq, J.P.; Hasan, R.; Firwana, B.; Nabhan, M.; Prokop, L.; Hingorani, A.; Claus, P.L.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of adjunctive therapies in diabetic foot ulcers. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 63, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, R.J.; Lalieu, R.C.; Hoencamp, R.; van Hulst, R.A.; Ubbink, D.T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcers with arterial insufficiency. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 71, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.R.; Lu, S.J.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.L.; Chen, X.C.; Pan, B.Y. Application of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in diabetic foot ulcers: A meta-analysis. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OuYang, H.; Yang, J.; Wan, H.; Huang, J.; Yin, Y. Effects of different treatment measures on the efficacy of diabetic foot ulcers: A network meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1452192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Sharma, S.K.; Mudgal, S.K.; Jelly, P.; Thakur, K. Efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot ulcer, a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira DACruz, D.L.; Oliveira-Pinto, J.; Mansilha, A. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on limb amputation and ulcer healing. Int. Angiol. 2022, 41, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranke, P.; Bennett, M.H.; Martyn-St James, M.; Schnabel, A.; Debus, S.E.; Weibel, S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD004123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Guo, J.; Qahar, M.; Huang, G.; Wu, J. Combination therapy of negative pressure wound therapy and antibiotic-loaded bone cement for accelerating diabetic foot ulcer healing: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shen, G.; Hao, C. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is superior to conventional moist dressings in wound bed preparation for diabetic foot ulcers: A randomized controlled trial. Saudi Med. J. 2023, 44, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, D.; Storck, M.; Lawall, H.; Wozniak, G.; Mauckner, P.; Hochlenert, D.; Wetzel-Roth, W.; Sondern, K.; Hahn, M.; Rothenaicher, G.; et al. Negative pressure wound therapy compared with standard moist wound care on diabetic foot ulcers in real-life clinical practice: Results of the German DiaFu-RCT. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e026345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavery, L.A.; La Fontaine, J.; Thakral, G.; Kim, P.J.; Bhavan, K.; Davis, K.E. Randomized Clinical Trial to Compare Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy Approaches with Low and High Pressure, Silicone-Coated Dressing, and Polyurethane Foam Dressing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Wu, R.W.; Hsu, M.C.; Hsieh, C.J.; Chou, M.C. Adjunctive Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Healing of Chronic Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2017, 44, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deen, H.A.B.; Wadee, A.N.; Eraky, Z.S.; Elmasry, H.M.; El-Sayed, M.S.; Fahmy, S.M. Combined low-intensity laser therapy and hyperbaric oxygen therapy on healing of chronic diabetic foot ulcers: A controlled randomized trial. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. El Deporte 2023, 18, 710–715. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Shukla, U.; Prabhakar, T.; Srivastava, D. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an adjuvant to standard therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 36, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nik Hisamuddin, N.A.R.; Wan Mohd Zahiruddin, W.N.; Mohd Yazid, B.; Rahmah, S. Use of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in chronic diabetic wound. Med. J. Malays. 2019, 74, 418–424. [Google Scholar]

- Palomar-Llatas, F.; Fornes-Pujalte, B.; Sierra-Talamantes, C.; Murillo-Escutia, A.; Moreno-Hernández, A.; Díez-Fornes, P.; Palomar-Fons, R.; Torregrosa-Valles, J.; Debón-Vicent, L.; Marín-Bertolin, S.; et al. Evaluación de la terapia con presión negativa tópica en la cicatrización de heridas agudas y úlceras cutáneas tratadas en un hospital valenciano. Enferm. Dermatológica 2015, 9, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lavery, L.A.; Murdoch, D.P.; Kim, P.J.; Fontaine, J.L.; Thakral, G.; Davis, K.E. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy With Low Pressure and Gauze Dressings to Treat Diabetic Foot Wounds. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2014, 8, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemyng, E.; Dwan, K.; Moore, T.H.; Page, M.J.; Higgins, J.P. Risk of Bias 2 in Cochrane Reviews: A phased approach for the introduction of new methodology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 10, ED000148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciapponi, A. AMSTAR-2: Herramienta de evaluación crítica de revisiones sistemáticas de estudios de intervenciones de salud. Evid. Actual. En. Práctica Ambulatoria. 2018, 21, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, A.J.; Rigau, D.; Rotaeche, R.; Selva, A.; Marzo-Castillejo, M.; Alonso-Coello, P. Sistema GRADE: Metodología para la realización de recomendaciones para la práctica clínica. Aten. Primaria 2015, 47, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-De-La-Torre, H.; Mosquera-Fernández, A.; Quintana-Lorenzo Ma, L.; Perdomo-Pérez, E.; Quintana-Montesdeoca Ma, D.P. Clasificaciones de lesiones en pie diabético: Un problema no resuelto. Gerokomos 2012, 23, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar-Llatas, F.; Fornes-Pujalte, B.; Tornero-Pla, A.; Muñoz, A. Escala valoración FEDPALLA de la piel perilesional. Enferm. Dermatol. 2007, 1, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, C.; Muñoz, T.; Chamorro, C. Monitorización del dolor: Recomendaciones del grupo de trabajo de analgesia y sedación de la SEMICYUC. Med. Intensiv. 2006, 30, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Astasio-Picado, Á.; Jurado-Palomo, J.; Pozo-Aranda, B.; Cobos-Moreno, P. Comparative Evidence on Negative Pressure Therapy and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review of Independent Effectiveness and Clinical Applicability. Medicina 2026, 62, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010109

Astasio-Picado Á, Jurado-Palomo J, Pozo-Aranda B, Cobos-Moreno P. Comparative Evidence on Negative Pressure Therapy and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review of Independent Effectiveness and Clinical Applicability. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010109

Chicago/Turabian StyleAstasio-Picado, Álvaro, Jesús Jurado-Palomo, Belén Pozo-Aranda, and Paula Cobos-Moreno. 2026. "Comparative Evidence on Negative Pressure Therapy and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review of Independent Effectiveness and Clinical Applicability" Medicina 62, no. 1: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010109

APA StyleAstasio-Picado, Á., Jurado-Palomo, J., Pozo-Aranda, B., & Cobos-Moreno, P. (2026). Comparative Evidence on Negative Pressure Therapy and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review of Independent Effectiveness and Clinical Applicability. Medicina, 62(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010109