Switching to Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine in Turkey: Perspectives from People Living with HIV in a Setting of Increasing HIV Incidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Age, 18 years or older;

- -

- Receiving a stable oral ART regimen for at least 6 months;

- -

- Having at least two documented HIV RNA measurements <50 copies/mL within the past 6 months.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- A documented or suspected genotypic resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) (except K103N) or to INSTIs;

- -

- History of virologic failure with any ART regimen;

- -

- Pregnancy;

- -

- Presence of chronic HBV co-infection;

- -

- Presence of a hip implant or filler;

- -

- Body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30;

- -

- Use of concomitant medications with potential interactions with LA-CAB/RPV;

- -

- Infection with HIV-1 subtype A1 or A6.

2.2. Data Collection

- (1)

- Sociodemographic Data: Age, gender, educational status (participants with no formal literacy were analyzed separately due to distinct patterns in understanding and interpreting informed consent and treatment-related information), place of residence, residential proximity to the healthcare center, housing status, and HIV status disclosure.

- (2)

- Clinical Data: Smoking status and alcohol use, presence or history of substance use disorder, BMI, presence of comorbidities, polypharmacy and the number of drug classes used, route of HIV transmission, duration of ART use, history and number of ART switches, current ART regimen, CD4+ T-cell count at diagnosis and current level, HIV RNA level at diagnosis, history of opportunistic infections, and HIV-associated malignancies.

- (3)

- Awareness of LA-CAB/RPV: Participants were asked whether they had prior knowledge of LA-CAB/RPV therapy and what their sources of information were. Regardless of their initial level of knowledge, all participants were provided with standardized information on LA-CAB/RPV, including evidence-based data and administration procedures, using a uniform treatment information sheet (Supplementary File S2) across all study centers.

- (4)

- Treatment Choice: Participant preference to either continue current oral ART or switch to LA-CAB/RPV.

- (5)

- Treatment Choice Motivations: The role of motivational factors, including perceived efficacy, perceived safety and tolerability, convenience and adherence, privacy and confidentiality, and cost-related concerns, was evaluated in relation to treatment preferences using structured questions designed in line with the literature and formulated to be easily understandable by all participants.

2.3. Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Treatment Preference

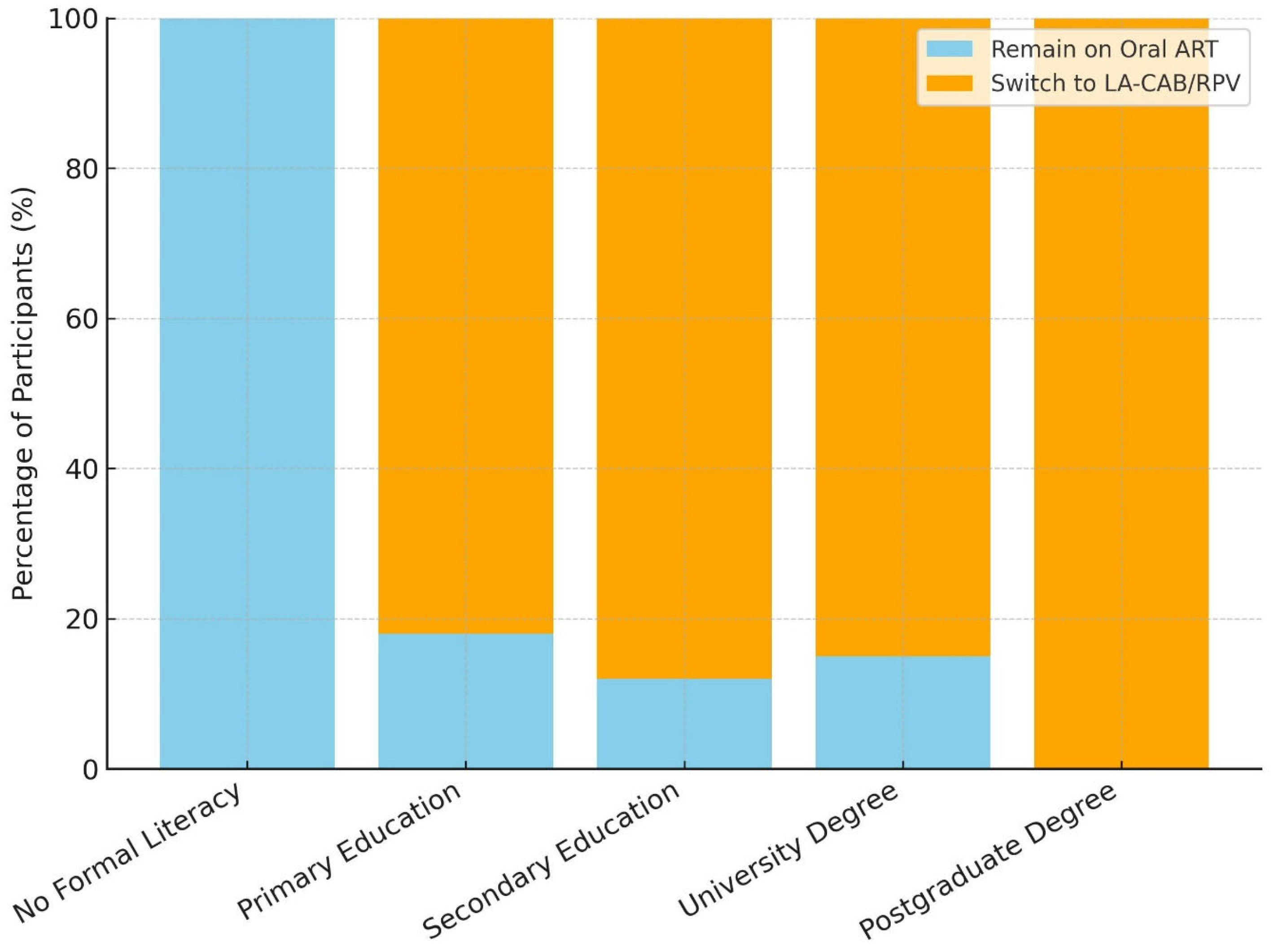

3.2. Sociodemographic, Clinical Characteristics, and Residential Factors

3.3. HIV Transmission, ART Use, and Clinical Follow-Up

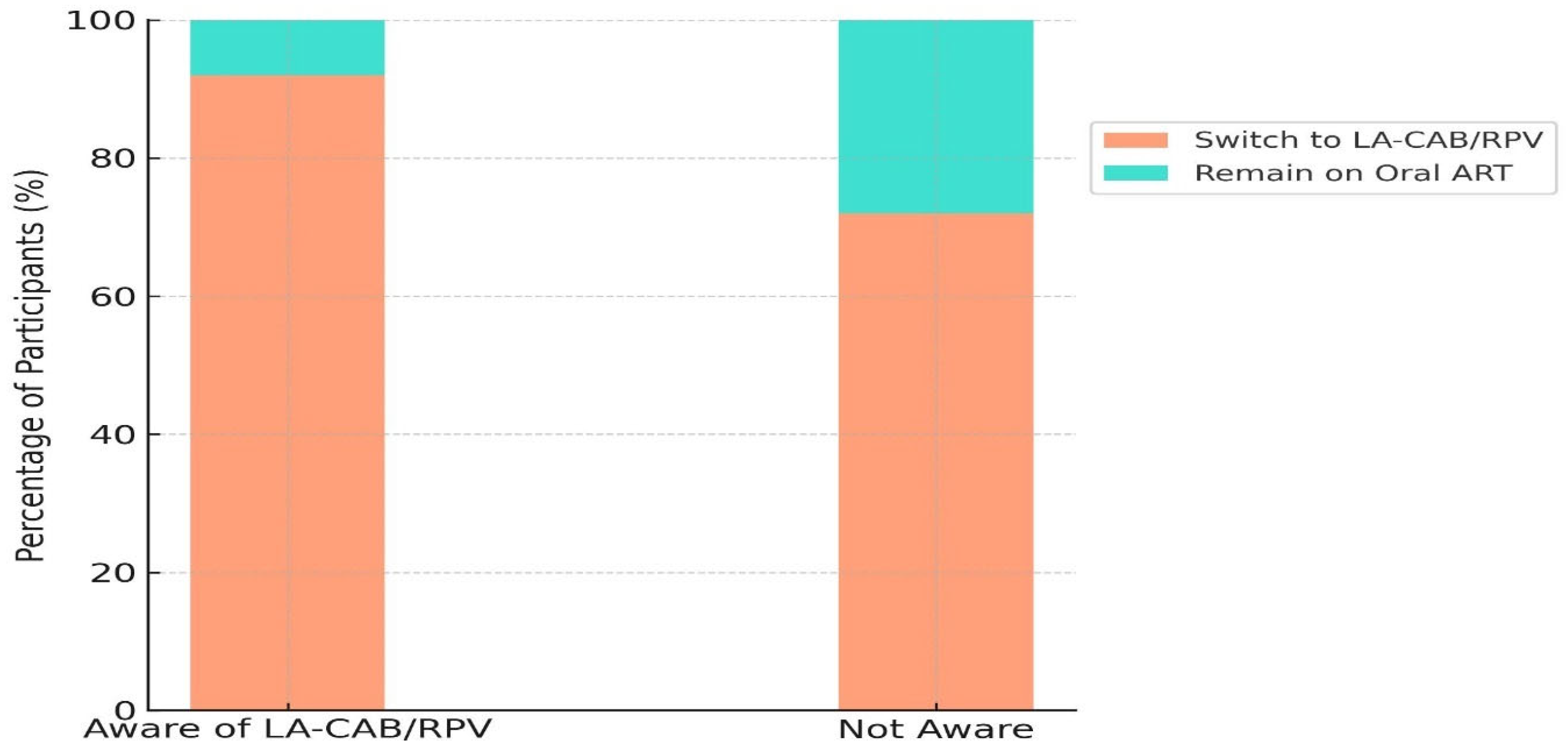

3.4. Awareness and Motivational Factors Influencing Treatment Preference

3.5. Impact of Hypothetical Six-Monthly Dosing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3TC | Lamivudine |

| ABC | Abacavir |

| ART | Antiretroviral Therapy |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BIC | Bictegravir |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| DTG | Dolutegravir |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EVG | Elvitegravir |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FTC | Emtricitabine |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HIVDB | Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| INSTI | Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitor |

| LA-CAB/RPV | Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine Injection Therapy |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| NIAAA | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

| NNRTI | Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor |

| PLWH | People Living with HIV |

| R | R Statistical Software |

| TAF | Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate |

| TDF | Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Derin, O. Gender and Age Trends in HIV Incidence in Turkey between 1990 and 2021: Joinpoint and Age–Period–Cohort Analyses. Medicina 2024, 60, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNAIDS. Understanding Fast-Track: Accelerating Action to end the AIDS Epidemic by 2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/201506_JC2743_Understanding_FastTrack_en.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Broder, S. The development of antiretroviral therapy and its impact on the HIV-1/AIDS pandemic. Antivir. Res. 2010, 85, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, R.T.; Bedimo, R.; Hoy, J.F.; Landovitz, R.J.; Smith, D.M.; Eaton, E.F.; Lehmann, C.; Springer, S.A.; Sax, P.E.; Thompson, M.A.; et al. Antiretroviral Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2022 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 2023, 329, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandgenett, D.P.; Engelman, A.N. Brief Histories of Retroviral Integration Research and Associated International Conferences. Viruses 2024, 16, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, N.; Maggiolo, F. Single-Tablet Regimens in HIV Therapy. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2014, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffi, F.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Fagnani, F.; Laurendeau, C.; Lafuma, A.; Gourmelen, J. Persistence and adherence to single-tablet regimens in HIV treatment: A cohort study from the French National Healthcare Insurance Database. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Rios, P.; Young, B.; Marcotullio, S.; Punekar, Y.; Koteff, J.; Ustianowski, A.; Murungi, A. 1329. Experiences and Emotional Challenges of Antiretroviral Treatment (ART)—Findings from the Positive Perspectives Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6 (Suppl. S2), S481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubber, Z.; Mills, E.J.; Nachega, J.B.; Vreeman, R.; Freitas, M.; Bock, P.; Nsanzimana, S.; Penazzato, M.; Appolo, T.; Doherty, M.; et al. Patient-Reported Barriers to Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.T.; Ryu, A.E.; Onuegbu, A.G.; Psaros, C.; Weiser, S.D.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Tsai, A.C. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: Systematic review and meta-synthesis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16 (Suppl. S2), 18640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swindells, S.; Flexner, C.; Fletcher, C.V.; Jacobson, J.M. The critical need for alternative antiretroviral formulations, and obstacles to their development. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacob, S.A.; Iacob, D.G.; Jugulete, G. Improving the Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy, a Difficult but Essential Task for a Successful HIV Treatment-Clinical Points of View and Practical Considerations. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, C.; Arasteh, K.; Górgolas Hernández-Mora, M.; Pokrovsky, V.; Overton, E.T.; Girard, P.M.; Oka, S.; Walmsley, S.; Bettacchi, C.; Brinson, C.; et al. Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine after Oral Induction for HIV-1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindells, S.; Andrade-Villanueva, J.F.; Richmond, G.J.; Rizzardini, G.; Baumgarten, A.; Masiá, M.; Latiff, G.; Pokrovsky, V.; Bredeek, F.; Smith, G.; et al. Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for Maintenance of HIV-1 Suppression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, E.T.; Richmond, G.; Rizzardini, G.; Jaeger, H.; Orrell, C.; Nagimova, F.; Bredeek, F.; García Deltoro, M.; Swindells, S.; Andrade-Villanueva, J.F.; et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with HIV-1 infection (ATLAS-2M), 48-week results: A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3b, non-inferiority study. Lancet 2021, 396, 1994–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Sarafianos, S.G.; Sönnerborg, A. Long-Acting Anti-HIV Drugs Targeting HIV-1 Reverse Transcriptase and Integrase. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). First Long-Acting Injectable Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Recommended for Approval. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/first-long-acting-injectable-antiretroviral-therapy-hiv-recommended-approval (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Approves Cabenuva and Vocabria for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv/fda-approves-cabenuva-and-vocabria-treatment-hiv-1-infection (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NIH). Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS). EACS Guidelines Version 12.1. November 2024. Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Turkish Medicines and Medical Devices Agency (TİTCK). List of Authorized Human Medicinal Products. Updated 13 June 2025. Available online: https://www.titck.gov.tr (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Garris, C.P.; Czarnogorski, M.; Dalessandro, M.; D’Amico, R.; Nwafor, T.; Williams, W.; Merrill, D.; Wang, Y.; Stassek, L.; Wohlfeiler, M.B.; et al. Perspectives of people living with HIV-1 on implementation of long-acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine in US healthcare settings: Results from the CUSTOMIZE hybrid III implementation-effectiveness study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e26006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwunmi, B.; Buchenberger, D.; Scherzer, J.; Bode, M.; Rizzini, P.; Vecchio, F.; Roustand, L.; Nachbaur, G.; Finkielsztejn, L.; Chounta, V.; et al. Factors associated with interest in a long-acting HIV regimen: Perspectives of people living with HIV and healthcare providers in four European countries. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2021, 97, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisk-Hoffman, R.J.; Ranger, S.S.; Gracy, A.; Gracy, H.; Manavalan, P.; Widmeyer, M.; Leeman, R.F.; Cook, R.L.; Canidate, S. Perspectives Among Health Care Providers and People with HIV on the Implementation of Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir/Rilpivirine for Antiretroviral Therapy in Florida. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2024, 38, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carillon, S.; Gallardo, L.; Linard, F.; Chakvetadze, C.; Viard, J.P.; Cros, A.; Molina, J.M.; Slama, L. Perspectives of injectable long acting antiretroviral therapies for HIV treatment or prevention: Understanding potential users’ ambivalences. AIDS Care 2020, 32, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrigan, D.; Mantsios, A.; Gorgolas, M.; Montes, M.L.; Pulido, F.; Brinson, C.; Devente, J.; Richmond, G.J.; Beckham, S.W.; Hammond, P.; et al. Experiences with long acting injectable ART: A qualitative study among PLHIV participating in a Phase II study of cabotegravir + rilpivirine (LATTE-2) in the United States and Spain. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database. Available online: https://hivdb.stanford.edu (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. HIV Drug Resistance Surveillance Guidance 2021 Update; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking & Tobacco Use: Fast Facts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Drinking Levels Defined. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Varghese, D.; Ishida, C.; Patel, P.; Koya, H.H. Polypharmacy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532953/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult BMI Calculator. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/adult-calculator/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/english_bmi_calculator/bmi_calculator.html (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Moreno, C.; Izquierdo, R.; Alejos, B.; Hernando, V.; Pérez de la Cámara, S.; Peraire, J.; Macías, J.; Bernal, E.; Albendín-Iglesias, H.; Alcaraz, B.; et al. Acceptability of Long-Acting Injectable Antiretroviral Treatment for HIV Management: Perspectives of Patients and Physicians in Spain. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2024, 38, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celesia, M.; Moscatt, V.; Tzannis, A.; Trezzi, M.; Focà, E.; Errico, M.; Cinque, P.; Nozza, S.; Cingolani, A.; Ceccarelli, M.; et al. Long-acting drugs: People’s expectations and physicians’ preparedness. Are we readying to manage it? An Italian survey. Medicine 2022, 101, e30052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelhorn, H.; Garris, C.; Arthurs, E.; Spinelli, F.; Cutts, K.; Chua, G.N.; Collacott, H.; Lebouché, B.; Lowman, E.; Rice, H.; et al. Patient and Physician Preferences for Regimen Attributes for the Treatment of HIV in the United States and Canada. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutner, C.A.; van der Valk, M.; Portilla, J.; Jeanmaire, E.; Belkhir, L.; Lutz, T.; DeMoor, R.; Trehan, R.; Scherzer, J.; Pascual-Bernáldez, M.; et al. Patient Participant Perspectives on Implementation of Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine: Results From the Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine Implementation Study in European Locations (CARISEL) Study. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 2024, 23, 23259582241269837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cordon, A.; Imaz, A.; Llibre, J.M.; Mallolas, J.; Martín-Carbonero, L.; Martínez, E.; Masiá, M.; Moltó, J.; Montejano, R.; Montero, M.; et al. Characteristics of Persons Starting Cabotegravir and Long-Acting Rilpivirine. Presented at the GeSIDA 2023 Congress, Poster P-004, Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Luc, C.M.; Max, B.; Pérez, S.; Herrera, K.; Huhn, G.; Dworkin, M.S. Acceptability of Long-Acting Cabotegravir + Rilpivirine in a Large, Urban, Ambulatory HIV Clinic. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2024, 97, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussini, C.; Cazanave, C.; Adachi, E.; Eu, B.; Alonso, M.M.; Crofoot, G.; Chounta, V.; Kolobova, I.; Sutton, K.; Sutherland-Phillips, D.; et al. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes after 12 months of maintenance therapy with cabotegravir + rilpivirine long-acting compared with bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in the phase 3b SOLAR study. AIDS Behav. 2025, 29, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandachi, D.; Garris, C.; Richardson, D.; Sinclair, G.; Cunningham, D.; Valenti, W.; Sherif, B.; Reynolds, M.; Nelson, K.; Merrill, D.; et al. Clinical Outcomes and Perspectives of People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Twelve Months After Initiation of Long-acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine in an Observational Real-world US Study (BEYOND). Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chounta, V.; Overton, E.T.; Mills, A.; Swindells, S.; Benn, P.D.; Vanveggel, S.; van Solingen-Ristea, R.; Wang, Y.; Hudson, K.J.; Shaefer, M.S.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes Through 1 Year of an HIV-1 Clinical Trial Evaluating Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine Administered Every 4 or 8 Weeks (ATLAS-2M). The patient 2021, 14, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.; Ward, T.; Hayward, O.; Jacob, I.; Arthurs, E.; Becker, D.; Anderson, S.J.; Chounta, V.; Van de Velde, N. Cost-effectiveness of the long-acting regimen cabotegravir plus rilpivirine for the treatment of HIV-1 and its potential impact on adherence and viral transmission: A modelling study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, S.; Rivero, A.; Ventayol, P.; Falcó, V.; Torralba, M.; Schroeder, M.; Neches, V.; Vallejo-Aparicio, L.A.; Mackenzie, I.; Turner, M.; et al. Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine Long-Acting Antiretroviral Therapy Administered Every 2 Months is Cost-Effective for the Treatment of HIV-1 in Spain. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 2039–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Aydın, Ö.A.; Karaosmanoğlu, H.K. Seroprevalence of HBsAg and Anti-HCV among HIV Positive Patients. Viral Hepat. J. 2021, 27, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerdali, E.; Nakir, I.Y.; Surme, S.; Yildirim, M. Hepatitis B virus prevalence, immunization and immune response in people living with HIV/AIDS in Istanbul, Turkey: A 21-year data analysis. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayan, M.; Sargin, F.; Inan, D.; Sevgi, D.Y.; Celikbas, A.K.; Yasar, K.; Kaptan, F.; Kutlu, S.; Fisgin, N.T.; Inci, A.; et al. HIV-1 Transmitted Drug Resistance Mutations in Newly Diagnosed Antiretroviral-Naive Patients in Turkey. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2016, 32, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadad, N.; Hashempour, A.; Nazar, M.M.K.; Ghasabi, F. Evaluating HIV drug resistance in the middle East and North Africa and its associated factors: A systematic review. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n (%) 1 | Switch to LA-CAB/RPV n (%) 1 | Remain on Oral ART n (%) 1 | p Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Median (IQR)) | 38.50 (29.00–47.00) | 37.50 (29.75–46.25) | 41.00 (30.00–52.00 | 0.367 |

| Gender (Male) | 177 (88.5) | 151 (85.3) | 26 (14.7) | 0.645 |

| BMI (Median (IQR)) | 25.00 (23.00–27.05) | 25.00 (23.00–27.05) | 25.30 (22.75–27.03) | 0.856 |

| Educational status | 0.510 | |||

| No formal education | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |

| Primary education | 45 (22.5) | 37 (82.2) | 8 (17.8) | |

| Secondary education (high school) | 65 (32.5) | 59 (90.8) | 6 (9.2) | |

| University degree | 84 (42) | 70 (83.3) | 14 (16.7) | |

| Postgraduate degree (Master/PhD) | 4(2) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Place of residence | 0.642 | |||

| Urban | 185(92.5) | 158 (85.4) | 27 (14.6) | |

| Rural | 15 (7.5) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Residential proximity to the healthcare centre | 0.018 | |||

| Same district | 105 (52.5) | 95 (90.5) | 10 (9.5) | |

| Different district, same province | 83 (41.5) | 70 (84.3) | 13 (15.7) | |

| Different province, same geographical region | 6 (3) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Different geographical region | 6 (3) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | |

| Housing Status | 0.306 | |||

| Living with family | 132 (66) | 113 (85.6) | 19 (14.4) | |

| Living alone | 47 (23.5) | 41 (87.2) | 6 (12.8) | |

| Living with partner(s) | 11 (5.5) | 11 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Living with others (non-family members) | 9 (4.5) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Residing in a nursing home | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| HIV Status Disclosure | 0.643 | |||

| Family Member(s) | 96 (48) | 83 (86.5) | 13 (13.5) | |

| Partner(s) | 64 (32) | 56 (87.5) | 8 (12.5) | |

| Close Friend(s) | 36 (18) | 29 (80.6) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Other(s) | 4(2) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Smoking Habit | 0.461 | |||

| Never Used | 89 (44.5) | 74 (83.1) | 15 (16.9) | |

| Former Smoker | 16 (8) | 15 (93.8) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Current Smoker | 95 (47.5) | 83 (87.4) | 12 (12.6) | |

| Alcohol Habit | 0.493 | |||

| Never Used | 112 (56) | 95 (84.8) | 17 (15.2) | |

| Low-risk Drinking | 85 (42.5) | 75 (88.2) | 10 (11.8) | |

| Risky Drinking | 3 (1.5) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| Substance Use Disorder | 18 (9) | 17 (94.4) | 1 (5.6) | 0.467 |

| Comorbidity | 34 (17) | 28 (82.4) | 6 (17.6) | 0.688 |

| Polypharmacy | 5 (2.5) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | |

| Number of Non-ART Drug Classes (Median (IQR)) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 1.00 (1.00–2.00) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 0.567 |

| n (%) 1 | Switch to LA-CAB/RPV n (%) 1 | Remain on Oral ART n (%) 1 | p Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Route | 0.371 | |||

| Sexual (Heterosexual) | 94 (47) | 78 (83) | 16 (17) | |

| Sexual (Bi/Homosexual) | 52 (26) | 45 (86.5) | 7 (13.5) | |

| Unknown | 46 (23) | 43 (93.5) | 3 (6.5) | |

| Percutaneus | 7 (3.5) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Other (Cupping Therapy) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Duration of ART Use (years (Median (IQR)) | 3.00 (2.00–5.00) | 3.00 (1.00–5.00) | 4.00 (3.00–4.25) | 0.240 |

| History of ART switches | 62 (31) | 54 (87.1) | 8 (12.9) | 0.936 |

| Number of ART switches (Median (IQR)) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.75) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00 | 0.478 |

| Current Oral ART Regimen | 0.092 | |||

| BIC/FTC/TAF | 129 (64.5) | 112 (86.8) | 17 (13.2) | |

| DTG/3TC | 26(13) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | |

| DTG/ABC/3TC | 17(8.5) | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | |

| DTG/FTC/TDF | 19(9.5) | 16 (84.2) | 3 (15.8) | |

| EVG/c/FTC/TAF | 9(4.5) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| HIV RNA Level (copies/mL) at Diagnosis (Median (IQR)) | 42,900 (11,400–157,000) | 42,600 (12,670–150,200) | 54,250 (490–309,750) | 0.867 |

| CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) at Diagnosis (Median (IQR)) | 416.50 (287.25–583) | 417.50 (291–594.5) | 391.5 (284.25–483.5) | 0.445 |

| Current CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) (Median (IQR)) | 729 (560.75–921.25) | 731 (565.5–921.25) | 680 (550–909.5) | 0.840 |

| History of Oppurtunistic Infection | 12 (6) | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | 0.677 |

| HIV-associated Malignancy | 5 (2.5) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.794 |

| n (%) 1 | Switch to LA-CAB/RPV n (%) 1 | Remain on Oral ART n (%) 1 | p Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness of LA-CAB/RPV treatment | 161 (80.5) | 148 (92) | 13 (8) | <0.0001 |

| Source of Information about LA-CAB/RPV | <0.0001 | |||

| Healthcare providers | 91 (45.5) | 80 (88) | 11 (12) | |

| Other PLWH | 7 (3.5) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Internet/Social Media | 38 (19) | 35 (92.1) | 3 (7.9) | |

| Internet/Health information websites | 27 (13.5) | 22 (81.5) | 5 (18.5) | |

| NGO/Community-based organization | 9 (4.5) | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | |

| Motivations for Treatment Choice | ||||

| Perceived efficacy | 169 (84.5) | 155 (91.7) | 14 (8.3) | <0.0001 |

| Perceived safety/tolerability | 144 (72) | 130 (90.3) | 14 (9.7) | 0.0102 |

| Convenience and adherence | 176 (88) | 157 (89.2) | 19 (10.8) | 0.0013 |

| Privacy | 167 (83.5) | 157 (94) | 10 (6) | <0.0001 |

| Cost | 120 (60) | 112 (93.3) | 8 (6.7) | 0.0006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dumlu, R.; Çiçek, Y.; Kapmaz, M.; Derin, O.; Akalın, H.; Önal, U.; Özdemir, E.; Ataman Hatipoğlu, Ç.; Tuncer Ertem, G.; Şener, A.; et al. Switching to Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine in Turkey: Perspectives from People Living with HIV in a Setting of Increasing HIV Incidence. Medicina 2025, 61, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081373

Dumlu R, Çiçek Y, Kapmaz M, Derin O, Akalın H, Önal U, Özdemir E, Ataman Hatipoğlu Ç, Tuncer Ertem G, Şener A, et al. Switching to Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine in Turkey: Perspectives from People Living with HIV in a Setting of Increasing HIV Incidence. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081373

Chicago/Turabian StyleDumlu, Rıdvan, Yeliz Çiçek, Mahir Kapmaz, Okan Derin, Halis Akalın, Uğur Önal, Egemen Özdemir, Çiğdem Ataman Hatipoğlu, Günay Tuncer Ertem, Alper Şener, and et al. 2025. "Switching to Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine in Turkey: Perspectives from People Living with HIV in a Setting of Increasing HIV Incidence" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081373

APA StyleDumlu, R., Çiçek, Y., Kapmaz, M., Derin, O., Akalın, H., Önal, U., Özdemir, E., Ataman Hatipoğlu, Ç., Tuncer Ertem, G., Şener, A., Akgül, L., Çağlar, Y., Ecer, D. T., Çelen, M. K., Oğuz, N. B., Yıldırım, F., Borcak, D., Şenoğlu, S., Arslan, E., ... Mert, A. (2025). Switching to Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine in Turkey: Perspectives from People Living with HIV in a Setting of Increasing HIV Incidence. Medicina, 61(8), 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081373