Abstract

Background and Objectives: Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an aggressive tumor that originates in the biliary tract and is subdivided anatomically into intrahepatic (iCCA) and extrahepatic (perihilar-pCCA and distal-dCCA). Diagnosis remains challenging, particularly for extrahepatic forms (pCCA and dCCA). We aimed to assess the relation between systemic inflammatory markers—specifically lymphocyte-related ratios—and tumor characteristics in a Romanian cholangiocarcinoma cohort. Materials and Methods: We conducted an exploratory single-center study including adult patients with a confirmed CCA histopathological diagnosis. We excluded patients with an uncertain diagnosis or tumors of the ampulla of Vater or gallbladder. Demographic and clinical data were retrospectively collected from medical records. Results: Tumor localization was the strongest predictor of metastatic disease. The odd of metastasis was 7.3 times higher for iCCA than dCCA and 4.5 times higher for iCCA than pCCA. Although several evaluated inflammatory biomarkers showed statistically significant associations, their clinical relevance was limited. The odds ratios for these biomarkers were characterized by lower bounds near the null value and wide confidence intervals, reflecting considerable patient heterogeneity, model instability, and inconclusive effect sizes. Conclusions: Our findings suggest a potential biological link between systemic inflammation, metastatic spread, and tumor differentiation grade that deserves further investigation using more accurate systemic inflammation biomarkers than those routinely collected.

1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a tumor that originates in the biliary tract and can be subdivided anatomically into two main types: intrahepatic (iCCA), which develops between the bile ductules and the bile ducts of second order, and extrahepatic (eCCA), which arises distally of those mentioned above. The eCCA can be categorized as perihilar (pCCA), which emerges in the left and/or right hepatic duct and/or at their confluence and distal cholangiocarcinoma (dCCA), which involves the main bile duct. The iCCA is considered the second most prevalent primary hepatic tumor, after hepatocellular carcinoma. As treatment options differ, a distinction between pCCA and dCCA must be made [1,2]. Cholangiocarcinoma is considered a rare cancer in most parts of the world, with an incidence of less than 6 cases per 100,000 people. However, incidence on the Asian continent is higher, with reports of up to 85 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in Thailand [3], where Opisthorchis viverrini, a liver fluke associated with bile duct inflammation is endemic [4]. Cholangiocarcinomas are aggressive tumors, with a median overall survival from diagnosis that ranges from 16.1 to 18 months, depending on whether or not there is a possibility to perform surgery with curative intent [5,6], but between 48.5% and 55% of iCCA patients undergoing surgery associated with adequate lymphadenectomy (retrieval of ≥6 lymph nodes) have metastatic lymph nodes [7]. Median overall survival in patients with biliary tract cancers (including gallbladder cancer) in a metastatic state is 4.5 months [8]. Mortality rates for iCCA per 100,000 person-years are higher than mortality rates for eCCA in Europe, with Ireland having the highest recorded rates of 2.67/100,000 person-years for the intrahepatic forms. Moreover, mortality trends are presenting an ascending tendency for iCCA in most European countries, with the highest average annual percentage change (AAPC) of 18.87% recorded in the Lithuanian population [9].

Multiple risk factors have been linked to CCA, some of the most notable are choledochal cysts with an odd ratio (OR) of 26.71 (95% confidence interval (CI) 15.8–45.16) for the development of iCCA and an OR of 34.49 (95% CI 24.36–50.12) for eCCA [10], Caroli disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) [11].Infection with liver flukes such as Opisthorchis viverrini, more characteristic for the Asian population, presents an OR of 6.35 (95% CI: 2.87–14.05) for the development of CCA, irrespective of its anatomical location [12]. History of choledocholithiasis is considered a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, with 2.64% of patients being diagnosed with CCA during a 10-year follow-up from the moment choledochal lithiasis was diagnosed [13]. Cholelithiasis, cirrhosis, infection with hepatitis B (HBV) and C viruses (HCV) have also been mentioned as risk factors for CCA, alongside other more common diseases such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), obesity, hypertension, and habits such as smoking or alcohol intake [10,11]. The presence of either systemic or local inflammation is the common point of some of the above-mentioned risk factors, which also leads to the assumption that inflammation itself could be a risk factor for tumorigenesis and, in turn, for the development of CCA and for the distant dissemination of tumoral tissue with several types of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors playing a role in this process [14,15,16].

The diagnostic approach in patients with pCCA or dCCA, as per the latest European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines, includes a definitive histopathological diagnosis, in all cases deemed feasible, regardless of the initial appreciation of the tumor’s resectability. Current recommendations consider the possibility of a multidisciplinary tumor-board-based diagnosis in cases of patients under suspicion for eCCA with no histopathological confirmation. In patients with intrahepatic forms of cholangiocarcinoma, the diagnosis is also based on histopathological confirmation [2]. Imagistic staging should include both magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) for local assessment and computed tomographic (CT) for evaluation of systemic disease in cases of iCCA and eCCA. Tumor markers are not routinely recommended to support the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, but bear a negative prognostic value [2,17].

Information regarding Romanian cholangiocarcinoma patients is scarce, and the latest article available dates to 2021. Prognosis is reduced in this population, with a 2-year survival rate of up to 5.5% for dCCA [18]. Diagnostic sensitivity of ultrasound for all three subtypes of cholangiocarcinoma was 73.5% in Romanian patients. The lowest sensitivity was recorded for patients with dCCA, with 33.3% [19]. One of the main issues in the management of patients with cholangiocarcinoma was the difficulty of obtaining an accurate histopathological diagnosis, which aligns with challenges described in other populations [20,21].

We aimed to evaluate the lymphocyte-related ratios in patients with cholangiocarcinoma, taking into account the presence of metastases at diagnosis and tumor localization. Secondly, an exploratory analysis of lymphocyte-related ratios according to tumor differentiation grade as outcome was also conducted.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Iuliu Haţieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca (No. 150/10.06.2025) and by the Ethics Committee of the “Professor Doctor Octavian Fodor” Regional Institute of Gastroenterology-Hepatology (No. 7202/17.06.2025). The ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent as the study involved only the analysis of pre-existing, routinely collected healthcare data.

2.1. Study Design

Our study is conducted using routinely collected health data on patients with definitive histopathological diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma who received medical treatment at the “Professor Doctor Octavian Fodor” Regional Institute of Gastroenterology-Hepatology.

We included in the sample adult patients (≥18 years of age) with a histopathological diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, irrespective of the anatomical location, with complete white blood count (WBCs) and platelet data available in the electronic hospital system. We targeted patients who were hospitalized between 1 January 2018, and 31 December 2022, regardless of the year of diagnosis. Patients with tumors of the gallbladder or the ampulla of Vater, those with inconclusive biopsy results, or incomplete CBC data were excluded.

The applied methodology adheres to the RECORD guideline [22].

2.2. Data Collection and Cleaning

The hospital electronic system was the source for data collection. The search was done using the following diagnostic codes included in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10): C22.1—Intrahepatic bile duct carcinoma, C24.0—Malignant neoplasm of extrahepatic bile duct, C24.8—Malignant neoplasm of overlapping sites of biliary tract, and C24.9—Malignant neoplasm of biliary tract, unspecified.

The following variables were collected retrospectively: demographic data (sex, age at diagnostic, residence), co-morbidities (obesity, Diabetes Mellitus-DM, hypertension), related diseases (cholangitis, cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis), WBCs (leukocyte-WBC, lymphocytes-LYM, monocytes-MON, and neutrophils-NEU; expressed as 109/L), platelets (PLT), and, whenever available, CRP (C-reactive protein, mg/dL). The following pathology-related variable data were collected: cholangiocarcinoma type (intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal), metastases at diagnosis, and differentiation grade (G1—well differentiated, G2—moderately differentiated, G3—poorly differentiated) whenever available. All collected data were at the time of diagnosis.

The 109/L format was used for all blood cell counts to ensure consistency in units. Data accuracy was verified by checking if quantitative values fall within expected ranges and no contradictions within or between fields (e.g., WBCs are no less than the sum of LYM, MON, and NEU). Verification was conducted when inconsistencies were observed, and data were corrected accordingly. After verification of accuracy, all personally identifiable information (e.g., names, patient IDs, addresses) was removed in compliance with data protection regulations (e.g., GDPR). Missing data were reported as missing and were not subjected to any imputation or handling procedure.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Nine derived variables were created using blood cell counts routinely collected as input data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Derived lymphocyte-related ratios and other inflammation ratios.

Statistical analysis was conducted in an exploratory manner. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and compared using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The distribution of quantitative variables was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test for each group and was considered distant from the theoretical normal distribution when p-values were less than 0.05. Median and interquartile range (defined as [Q1 to Q3], where Q is the value of the first-Q1 quartile and third-Q3 quartile) were reported when the distribution proved far away from the theoretical normal distribution. Consequently, non-parametric tests were used to compare non-normally distributed data: the Mann–Whitney test for metastasis status as the dependent variable, and the Kruskal–Wallis test for tumor localization and tumor grade.

Logistic regression or ordinal regression analysis was conducted to test the prediction potential of lymphocyte-related ratios and the outcomes of interest whenever statistically significant differences were observed between subgroups. Crude (unadjusted) and adjusted ORs (odd ratios) with associated 95% confidence intervals [lower bound to upper bound] were reported. The overall fit of the regression model was evaluated using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with lower values indicating a better model fit.

All statistical analyses, including descriptive and inferential methods, were conducted using the Jamovi software (v. 2.6.26.0). Figures were generated using Microsoft Excel or Jamovi, and the significance level was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

Three hundred twenty-seven patients, aged between 36 and 89 years, were included in the study. Most participants were male (193, 59.0%), lived in an urban area (211/327, 64.5%), and had hypertension as a comorbidity (175/327, 53.5%). A quarter (82/327, 25.1%) had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, 42 (12.8%) were obese, and 27 (8.3%) also had other types of cancer. Eighty-six patients (26.3%) had a medical history of cholelithiasis, and 22 (6.7%) had choledocholithiasis. Fifty-nine patients (18.0%) had cholangitis at the time of diagnosis. One hundred and fifteen patients (35.2%) had metastases at time of the diagnosis. No preponderance of pathology was recorded according to tumor location: 116 (35.5%) were intrahepatic (iCCA), 112 (34.3%) perihilar (pCCA), and 99 (30.3%) distal cholangiocarcinoma (dCCA). Information regarding the differentiation grade was available for 214 patients (65.4%), with a preponderance of moderately differentiated tumors (97, 45.3%) and poorly differentiated (64, 29.9%), opposite to well differentiated (53, 24.8%).

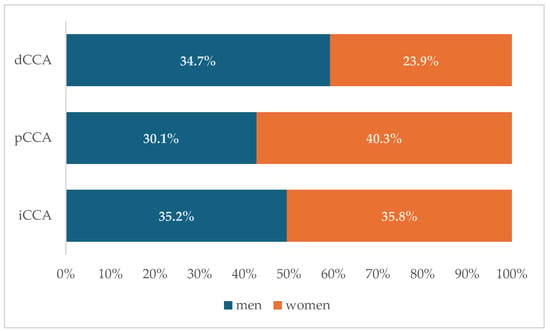

The age at diagnosis was statistically significant different (Mann–Whitney test: p = 0.027), when men (median = 66 years, IQR = [61 to 71]) were compared to women (median = 64.5 years, IQR = [56 to 70]). A higher percentage of women had metastases at diagnosis (54/134, 40.3%) compared to men (61/193, 31.6%), the difference being statistically significant (Chi-squared test: χ2 = 2.62, p-value = 0.105). Localization of tumor was uniform among men (68, 35.2% iCCA, 58, 30.1% pCCA, and 67, 34.7% dCCA), with most of the cases as pCCA (54, 40.3%) and iCCA (48, 35.8%), and less frequent dCCA (32, 23.9%) among women (Chi-squared test: χ2 = 5.50, p = 0.064). The distribution of differentiation grade was similar among men and women (Chi-squared test: χ2 = 0.52, p-value = 0.768, n = 214). The values of LMR were higher in women (3.1 [2.3 to 4.5]) than in men (2.3 [1.6 to 3.3]), with statistically significant differences (Mann–Whitney test: p-value < 0.001). Men had higher values for N/LPR (1.5 [1 to 2.2]), MWR (7.6 [6.4 to 9.4]), and SIRI (2.5 [1.5 to 4.5]) than women (N/LPR: 1.2 [0.8 to 2]), MWR: 6.4 [4.9 to 8.1], and SIRI: 1.8 [1.2 to 3.3]), the differences being statistically significant (Mann–Whitney test: p-value = 0.027 for N/LPR, p-value < 0.001 for MWR, and p-value = 0.005 for SIRI).

3.1. Lymphocyte-Related Biomarkers of Metastases

The age of patients with metastases (65 years [58 to 68]) and those without (66 years [60 to 72]) at diagnosis, either at the lymph node or organ level, was similar (Mann–Whitney test: p-value = 0.109). Patients with metastases had more frequent intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and higher values of lymphocyte-related biomarkers than those without metastases, except for MWR, which exhibits lower values (Table 2). Only SIRI had similar values regardless of the presence or absence of metastases at diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients stratified by metastases at diagnosis.

The association between CCA type and sex had a tendency towards statistical significance (Chi-squared test: χ2 = 5.5, p-value = 0.064, n = 327), while statistically significant differences were observed regarding the age between men and women. Considering these observations, these two factors were considered covariates in logistic regression analysis. The risk of metastases was 7.3 times higher for patients with intrahepatic tumors, and 4.5 times higher for patients with perihilar localization compared to those with distal CCA (Table 3). Although lymphocyte-related biomarkers showed potential, the ORs around the value of one (Table 3) indicate limited clinical performance.

Table 3.

Factors associated with the risk of metastases: crude and adjusted models for metastases at diagnosis.

3.2. Lymphocyte-Related Biomarkers of Cholangiocarcinoma Localization

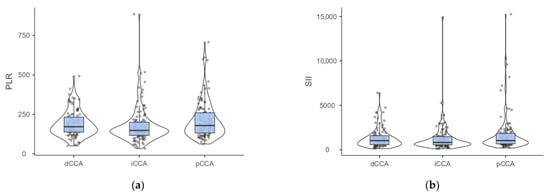

No preponderant localization was observed in our cohort (Figure 1). Similar patient characteristics were observed regardless of the localization (Table 4), but with a higher percentage of patients with cholelithiasis and higher values of PLR (Figure 2a) and SII (Figure 2b) among those with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Figure 1.

Distribution of cholangiocarcinoma subtypes by sex. (dCCA—distal cholangiocarcinoma; pCCA—perihilar cholangiocarcinoma; iCCA—intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma).

Table 4.

Patient’s characteristics stratified by tumor localization.

Figure 2.

(a) Distribution of PLR by cholangiocarcinoma localization. (Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner pairwise comparisons: p-value = 0.011 for iCCA vs. pCCA, p-value = 0.067 for iCCA vs. dCCA, p-value = 0.752 for pCCA vs. dCCA). (b) Distribution of SII by cholangiocarcinoma localization. (Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner pairwise comparisons: p-value = 0.05 for iCCA vs. pCCA, p-value = 0.433 for iCCA vs. dCCA, p-value = 0.759 for pCCA vs. dCCA; iCCA—intrahepatic; pCCA—perihilar; dCCA—distal cholangiocarcinoma).

Post hoc analysis of PLR showed statistically significant differences between patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and those with perihilar localization (Figure 2a). Similarly, the tendency towards statistical significance observed for SII (Table 4) was also observed in comparison of iCCA with pCCA (Figure 2b).

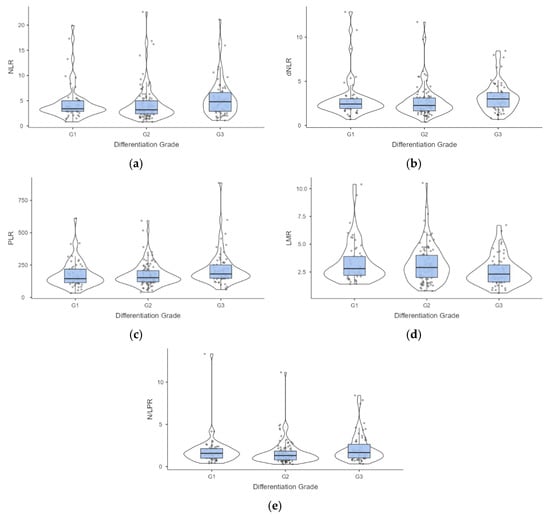

3.3. Lymphocyte-Related Biomarkers and Differentiation Grade of Cholangiocarcinoma

The information regarding the differentiation grade was available for 214 patients aged from 36 to 89 years old, half of them older than 65 years old. Most intrahepatic tumors are moderately or poorly differentiated, and at least half of patients with poorly differentiated tumors had metastases at diagnosis (Table 5). The values of NLR, dNLR, PLR, LMR, and N/LPR proved statistically significant differences by differentiation grade (Table 5), reflected by significant differences between G1 and G3 (Figure 3).

Table 5.

Characteristics stratified by differentiation grade.

Figure 3.

Distribution of values associated with evaluated lymphocyte-related biomarkers by differentiation grade of the cholangiocarcinoma. Post hoc analysis (a) NLR—neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: p = 0.020 G2 vs. G3; (b) dNLR—derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: p = 0.033 G2 vs. G3; (c) PLR—platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio: p = 0.036 G1 vs. G3, and p = 0.021 G2 vs. G3; (d) LMR—lymphocyte-to-monocytes ratio: p = 0.025 G1 vs. G3, and p = 0.035 G2 vs. G3; (e) N/LPR—neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet ratio: p = 0.030 G2 vs. G3.

The presence of metastases at the time of diagnosis was a statistically significant predictor for differentiation grade, with the odds of having a poorly differentiated tumor 2.5 times higher for patients with metastases at diagnosis. Similarly, perihilar and distal localization were significant predictors, indicating a lower odd of a poorly differentiated tumor (Table 6). Although PLR and LMR proved statistically significant, supporting their potential as predictors of differentiation grade, they had limited clinical relevance since the ORs values are around the value of one (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors associated with the differentiation grade: crude and adjusted models.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The risk of metastases in our cohort was higher for patients with intrahepatic (7.4) or perihilar (4.5) tumors compared to those with distal CCA. The values of PLR proved statistically significant for different tumor localizations (p-value = 0.009), with SII showing a tendency towards statistical significance (p-value = 0.065), as reflected in the comparison of intrahepatic and perihilar localization. Although lymphocyte-related biomarkers showed potential in the differentiation of CCA patients with and without metastases, and the patients with different differentiation grades, the unadjusted and adjusted ORs around the value of one indicate limited clinical relevance. Our findings provide a critical negative result that underscores the challenges of applying readily available lymphocyte-related ratios calculated from routinely measured biomarkers in patients with CCA, highlighting the potential for population-specific variations. Our negative results are of substantial clinical and scientific importance, suggesting that the pursuit of these biomarkers as standalone evaluation tools in CCA may be unproductive.

4.2. Findings Interpretation

Distribution of cholangiocarcinoma cases according to anatomical positioning in our cohort shows that all three anatomical subtypes exhibit similar incidence rates. In contrast with our findings, previous epidemiological data on European patients suggest that the most common subtype is pCCA, followed closely by dCCA, with iCCA less frequently [23]. This difference could be explained by our applied inclusion criteria, with evaluation only of the patients with a definitive histopathological diagnosis, while difficulties in tissue sampling have been reported. Sensitivity of 49% and specificity of 96.33% were reported for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with the acquisition of either brush cytology or forceps biopsy, and a sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 100%, respectively, was reported for endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle biopsies (EUS-FNA) [24]. Another plausible explanation could be the miscoding to the previous use of ICD-10, which did not include a specific diagnostic code for pCCA [25]. In a large retrospective study on the Thai population, only 21.6% of male and 23.1% of female patients with cholangiocarcinoma had a histopathological confirmation of the disease [26]. This finding underscores the technical challenges often encountered in obtaining adequate biopsy samples in this disease.

Our cohort reflected the well-documented male predominance in cholangiocarcinoma [27], with a male-to-female ratio of 1.44:1. Our finding shows that men are significantly older at diagnosis than women. Sex-related differences in patients with cholangiocarcinoma have been previously reported, but men had lower reported age medians at diagnosis than females (66 years vs. 68 years) in the Thai population [26]. Cholangiocarcinoma patients from the United States are similar to our results, with older males than females at diagnosis (mean age of 68.8 ± 0.14 years for men and 67.8 ± 0.14 years for women) [28]. Another sex-related difference in this cohort was that females were more likely to present with metastatic disease at any site (lymph nodes or other organs) at the time of diagnosis. Opposite to our results, male sex has previously been associated with a higher risk for lymph node metastases in patients with iCCA [29]. In our cohort, we observed that perihilar cholangiocarcinoma was significantly more common in women than in men. A higher incidence of iCCA and eCCA in men than in women was reported in American patients, but if stratified according to age, patients older than 80 years were predominantly female [30].

Patients with iCCA and pCCA in our cohort were diagnosed in a more advanced stage than those with dCCA (see Table 2). The presence of metastatic disease was previously reported as more commonly found in iCCA (43.5%), followed by pCCA (30.3%) and dCCA (30.1%) [31], results that partially align with the results of our study. This is an effect of the more clinically evident presentation of patients with eCCA, who are more prone to developing obstructive jaundice due to biliary obstruction. Patients with pCCA present with jaundice (the median of bilirubin of 3.3 mg/dL, IQR = [0.9 to 10.6]) compared to patients with iCCA (0.6 mg/dL, IQR = [0.4 to 1.1]) [32].

Modified systemic inflammation scores are linked to the presence of metastatic disease (Table 2 and Table 3), but are also linked to a poorer degree of tumor differentiation (Table 5, Figure 2). Systemic inflammation scores such as SII or NLR have been associated with the presence of metastases at the time of diagnosis and have been previously reported for prognostic evaluation of cholangiocarcinoma patients [33]. Also, PLR was an independent risk factor for lymph node metastases with OR = 5.14 (95% CI [1.21 to 21.7]), thus being suggested as a valuable tool for pre-surgical assessment of the presence of metastatic lymph nodes [34]. However, inflammation scores, such as SII, did not have any association with the degree of tumoral differentiation [35], a result also observed in our cohort (Table 5).

Patients with metastases were more likely to have a poorly differentiated tumor (Table 5). Previous evidence showed that poorly differentiated tumors are more likely to have lymph node metastases [29].

Logistic regression revealed that tumor localization was significantly associated with metastasis at diagnosis in both unadjusted and age/sex-adjusted models (Table 3). However, the wide confidence intervals suggest considerable uncertainty in the effect size estimates and potential model instability. Similar results were also observed when differentiation grade was the outcome variable, with 2.5 times higher odds of presence of metastases at diagnosis in patients with poorly differentiated tumors (Table 6). In contrast, perihilar and distal tumor localizations were associated with a lower likelihood of poor differentiation with high variations when adjusted by sex (Table 6). Although some of the evaluated biomarkers showed statistical significance, the lower bounds of ORs close to the null value (one) indicate their limited clinical relevance. Furthermore, the wide confidence intervals around these ORs reflect considerable patient heterogeneity, model instability, and ultimately, inconclusive results for the broader population as expected in an exploratory study.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Our study brings substantial information on the Romanian population of CCA patients, with the largest demographic and clinical data, a previously under described population. Given the lower incidence of the disease in Europe overall and the conflicting previous results, there is a need for updated research in this specific group of patients. Diagnosis and management in CCA patients are highly time-sensitive because of their aggressive nature, and any new insight can improve clinical outcomes. Current guidelines recommend a definitive histopathological diagnosis or, in case of failure of diagnostic methods, to have a multidisciplinary decision for the diagnosis of CCA in suspicious cases [17]. Continuous updates of information on cholangiocarcinoma patients are essential due to the constantly changing characteristics of patients with this diagnosis and because of its aggressive nature.

Although the main strength of our study lies in the evaluation of a large-scale dataset in Romanian CCA patients, a series of limitations derived from study design and analysis of routinely collected data, and the study’s retrospective nature must be acknowledged. Targeting patients from a single hospital with a positive histopathological diagnosis using medical charts as a source of data, our study is susceptible to selection bias and unmeasured confounding. Data collection from medical charts is susceptible to incompleteness. The presence of missing data reduces the statistical power of our analysis and increases the uncertainty of our estimates, reflected in wide confidence intervals. In the absence of any treatment for missing data, the potential for residual bias is acknowledged, and the robustness of our findings should be interpreted accordingly. As an exploratory study, no multiple testing correction was applied. Thus, the risk of Type I errors is inflated, so the identified statistically significant results should be considered as preliminary results and must be validated in independent, confirmatory cohorts if considered relevant. Last but not least, our results must be interpreted beyond statistical significance. The wide confidence intervals and effect sizes near the null value indicate that our findings have limited clinical relevance, despite their statistical significance. While our study was not sufficiently powered to detect small effects, it provides valuable foundational data for future research.

5. Conclusions

In this Romanian cohort, we found that intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) was significantly associated with metastatic disease at diagnosis compared to other localizations of CCA. We also found that routinely collected lymphocyte-based ratios held limited value for the evaluation of patients with cholangiocarcinoma. This negative finding refines the utility of such biomarkers in CCA assessment. However, our results suggest a potential biological link between tumor aggressiveness and systemic inflammation that deserve further investigation in prospective studies, maybe considering dynamic measurements in the context of genetic and molecular tumor characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.V., S.D.B., A.S. and R.C.; methodology, S.D.B. and A.D.V.; validation, N.A.H., A.C., S.D.B. and V.A.I.; formal analysis, S.D.B.; investigation, A.D.V., N.A.H., A.C. and V.A.I.; resources, N.A.H., A.S. and A.C.; data curation, S.D.B. and A.D.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.V. and S.D.B.; writing—review and editing, N.A.H., R.C., A.C., V.A.I. and A.S.; visualization, S.D.B.; supervision, A.S., N.A.H. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Iuliu Hațiganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca (No. 150/10.06.2025) and by the Ethics Committee of the “Professor Doctor Octavian Fodor” Regional Institute of Gastroenterology-Hepatology (No. 7202/17.06.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this research. The two above-mentioned ethics committees have approved this.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCA | cholangiocarcinoma |

| iCCA | intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma |

| eCCA | extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma |

| pCCA | perihilar cholangiocarcinoma |

| dCCA | distal cholangiocarcinoma |

| OR | Odd Ratio |

| PSC | Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| ERCP | Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography |

| EUS | Endoscopic Ultrasound |

| FNB | Fine-Needle Biopsy |

| 95% CI | 95% confidence interval |

| CT | Computed Tomographic |

| MRCP | Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography |

| CA 19-9 | Carbohydrate Antigen 19-9 |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CA 125 | Cancer Antigen 125 |

| WBCs | White Blood Cells |

| WBC | Leukocyte |

| LYM | Lymphocytes |

| MON | Monocytes |

| NEU | Neutrophils |

| PLT | Platelets |

| CRP | C reactive protein |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| dNLR | derived Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| PLR | Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio |

| LMR | Lymphocyte-to-Monocytes Ratio |

| MWR | Monocyte-to-White blood cell Ratio |

| N/LPR | Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet Ratio |

| SIRI | Systemic Inflammatory Response Index |

| SII | Systemic Immune-inflammation Index |

| AISI | Aggregate Index of Systemic Inflammation |

References

- Kasper, D.L.; Fauci, A.S.; Hauser, S.L.; Longo, D.L.; Jameson, J.L.; Loscalzo, J. Harrison’s Gastroenterology and Hepatology; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alvaro, D.; Gores, G.J.; Walicki, J.; Hassan, C.; Sapisochin, G.; Komuta, M.; Forner, A.; Valle, J.W.; Laghi, A.; Ilyas, S.I.; et al. EASL-ILCA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 181–208, Erratum in J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banales, J.M.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Marzioni, M.; Andersen, J.B.; Invernizzi, P.; Lind, G.E.; Folseraas, T.; Forbes, S.J.; Fouassier, L.; et al. Expert consensus document: Cholangiocarcinoma: Current knowledge and future perspectives consensus statement from the European Network for the Study of Cholangiocarcinoma (ENS-CCA). Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaewpitoon, N.; Kaewpitoon, S.-J.; Pengsaa, P.; Sripa, B. Opisthorchis viverrini: The carcinogenic human liver fluke. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Zweigle, J.; Patel, P.; Tedder, B.; Khan, R.; Agrawal, S. Survival analysis of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma based on surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2023, 7, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, R.; Hemming, A.W.; Zendejas, I.; George, T.; Nelson, D.R.; Soldevila-Pico, C.; Firpi, R.J.; Morelli, G.; Clark, V.; Cabrera, R. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 29, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposito, C.; Cucchetti, A.; Ratti, F.; Alaimo, L.; Ardito, F.; Di Sandro, S.; Serenari, M.; Berardi, G.; Maspero, M.; Ettorre, G.M.; et al. Probability of Lymph Node Metastases in Patients Undergoing Adequate Lymphadenectomy during Surgery for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Liver Cancer 2024, 14, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, V.; Wood, S.; Ramachandran, R.; Williams, G.; Outlaw, D.; Paluri, R.; Kim, Y.-I.; Gbolahan, O. Short- and Long-Term Survival of Metastatic Biliary Tract Cancer in the United States From 2000 to 2018. Cancer Control 2023, 30, 10732748231211764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithayathil, M.; Khan, S.A. Current epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma in Western countries. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1690–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, O.; Eliahoo, J.; Kim, J.U.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D.; Khan, S.A. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.L.; Yang, B.; Altekruse, S.F.; Van Dyke, A.L.; Koshiol, J.; I Graubard, B.; McGlynn, K.A. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: A population-based study in SEER-Medicare. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamsa-ard, S.; Kamsa-ard, S.; Luvira, V.; Suwanrungruang, K.; Vatanasapt, P.; Wiangnon, S. Risk Factors for Cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, J.-C.; Hwang, J.-H. Choledocholithiasis as a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Giordano, D.M.; Maroni, L.; Marzioni, M. Role of inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines in cholangiocyte pathophysiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landskron, G.; De la Fuente, M.; Thuwajit, P.; Thuwajit, C.; Hermoso, M.A. Chronic Inflammation and Cytokines in the Tumor Microenvironment. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 149185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, A.; Andoh, A. The Role of Inflammation in Cancer: Mechanisms of Tumor Initiation, Progression, and Metastasis. Cells 2025, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzioni, M.; Maroni, L.; Aabakken, L.; Carpino, G.; Koerkamp, B.G.; Heimbach, J.; Khan, S.; Lamarca, A.; Saborowski, A.; Vilgrain, V.; et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 211–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, F.; Tantau, M.; Diaconu, B.; Acalovschi, M. Survival and quality of life of cholangiocarcinoma patients: A prospective study over a 4 year period. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2010, 19, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Albu, S.; Tantau, M.; Spârchez, Z.; Branda, H.; Suteu, T.; Badea, R.; Pascu, O. Diagnosis and treatment of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Results in a series of 124 patients. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2005, 14, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Navaneethan, U.; Njei, B.; Lourdusamy, V.; Konjeti, R.; Vargo, J.J.; Parsi, M.A. Comparative effectiveness of biliary brush cytology and intraductal biopsy for detection of malignant biliary strictures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 81, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiosu, T.; Voiosu, A.; Danielescu, C.; Popescu, D.; Puscasu, C.; State, M.; Chiricuţă, A.; Mardare, M.; Spanu, A.; Bengus, A.; et al. Unmet needs in the diagnosis and treatment of Romanian patients with bilio-pancreatic tumors: Results of a prospective observational multicentric study. Rom. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 59, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Smeeth, L.; Guttmann, A.; Harron, K.; Moher, D.; Petersen, I.; Sørensen, H.T.; von Elm, E.; Langan, S.M. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Sanchez, L.; Lamarca, A.; La Casta, A.; Buettner, S.; Utpatel, K.; Klümpen, H.-J.; Adeva, J.; Vogel, A.; Lleo, A.; Fabris, L.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma landscape in Europe: Diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic insights from the ENSCCA Registry. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moura, D.T.H.; De Moura, E.G.H.; Bernardo, W.M.; De Moura, E.T.H.; I Baraca, F.; Kondo, A.; Matuguma, S.E.; Artifon, E.L.A. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography versus endoscopic ultrasound for tissue diagnosis of malignant biliary stricture: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc. Ultrasound 2018, 7, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvadurai, S.; Mann, K.; Mithra, S.; Bridgewater, J.; Malik, H.; Khan, S.A. Cholangiocarcinoma miscoding in hepatobiliary centres. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahat, O.; Bilheem, S.; Lim, A.; Kamsa-Ard, S.; Suwannatrai, A.T.; Uadrang, S.; Leklob, A.; Chansaard, W.; Sriket, N.; Santong, C.; et al. Updated cholangiocarcinoma incidence trends and projections in Thailand by region based on data from four population-based cancer registries. Lancet Reg. Health Southeast Asia 2025, 35, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gad, M.M.; Saad, A.M.; Faisaluddin, M.; Gaman, M.A.; Ruhban, I.A.; Jazieh, K.A.; Al-Husseini, M.J.; Simons-Linares, C.R.; Sonbol, M.B.; Estfan, B.N. Epidemiology of Cholangiocarcinoma; United States Incidence and Mortality Trends. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2020, 44, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Tedder, B.; Waqar, S.H.; Mohamed, R.; Cate, E.L.; Ali, E. Changing incidence and survival of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma based on Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database (2000–2017). Ann. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2022, 26, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.P.; Ruff, S.; Diggs, L.P.; Drake, J.; Ayabe, R.I.; Brown, Z.J.; Wach, M.M.; Steinberg, S.M.; Davis, J.L.; Hernandez, J.M. Tumor grade and sex should influence the utilization of portal lymphadenectomy for early stage intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. HPB 2019, 21, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadeghi, S.; Liu, B.; Bhuket, T.; Wong, R.J. Sex-specific and race/ethnicity-specific disparities in cholangiocarcinoma incidence and prevalence in the USA: An updated analysis of the 2000–2011 Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registry. Hepatol. Res. 2016, 46, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, H.; Jeong, S.; Sha, M.; Kong, D.; Xi, Z.; Tong, Y.; Xia, Q. Cholangiocarcinoma: Anatomical Location-Dependent Clinical, Prognostic, and Genetic Disparities. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleo, A.; Colapietro, F.; Maisonneuve, P.; Aloise, M.; Craviotto, V.; Ceriani, R.; Rimassa, L.; Badalamenti, S.; Donadon, M.; Pedicini, V.; et al. Risk Stratification of Cholangiocarcinoma Patients Presenting with Jaundice: A Retrospective Analysis from a Tertiary Referral Center. Cancers 2021, 13, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Huang, R.; Gao, F.; Feng, X.; Lan, T.; Li, H.; Wu, H. Development and Validation of a New Prognostic Immune-Inflammatory-Nutritional Score for Predicting Outcomes after Curative Resection for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Multicenter Study. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1165510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-T.; Pang, J.-S.; Lin, P.; Chen, J.-M.; Wen, R.; Liu, C.-W.; Wen, Z.-Y.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Peng, J.-B.; Zhang, L.; et al. Preoperative Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: An Integrative Approach Combining Ultrasound-Based Radiomics and Inflammation-Related Markers. BMC Med. Imaging 2025, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, X.; Hua, L.; Yang, R. Prognostic and Clinical Value of the Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Biliary Tract Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 6988489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).