Abstract

Background and Objectives: Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a common orthopedic procedure. It helps restore mobility and reduce pain in patients with hip joint disorders. Periprosthetic femoral fracture (PFF) is an acute complication that may occur after primary THA. The rate of PFFs after primary total hip replacement is approximately 1%. The aim of this study was to assess the overall quality of life of patients following PFF surgery. Materials and Methods: This cross-sectional study included 60 patients with PFFs of Vancouver type B (32 females and 28 males, respectively), with a mean age of 73.02 ± 8.97 years and 30 controls who underwent primary THA. Quality of life was assessed at least 12 months postoperatively using the validated Serbian SF-36 questionnaire and clinical examination. Results: Older age correlated with declines in Physical and Emotional functioning, Vitality (Energy/fatigue), and Social activities (overall SF-36: r = −0.619, p < 0.01). Patients who underwent femoral stem revision with osteosynthesis (B2 and B3) showed better quality of life compared to those who underwent osteosynthesis alone (B1) in General health perceptions (t = −2.266, p = 0.027) and Physical functioning (t = 2.526, p = 0.014). Patients after PFF surgery had lower postoperative quality of life compared to those who underwent primary THA (overall SF-36: 66.68 ± 15.60 vs. 84.10 ± 14.65, t = −5.092, p < 0.0005). Conclusions: Patients with PFF have a lower quality of life than those after primary THA, while combined stem revision and osteosynthesis yield better outcomes than osteosynthesis alone.

1. Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is one of the most common procedures in orthopedic surgery, which helps restore mobility and reduce pain in patients with hip joint disorders [1]. The demand for THA is expected to increase by 43% to 70% by 2030 [2].

Periprosthetic femoral fracture (PFF) is an acute complication that may occur after primary THA [3]. The rate is approximately 1% [4], and is estimated to increase by 4.6% every 10 years over the next 30 years [5].

As the number of THA procedures increases, so does the incidence of complications. PFF accounts for 3.5–5.0% of all THA-related complications [6]. The most frequent causes are aseptic implant loosening, instability, and infection [7]. PFF can occur intraoperatively or postoperatively (1% vs. 5%) and is more common with uncemented prostheses (cemented 0.3%, uncemented 5.4%) [6]. Fractures typically occur in elderly patients with pre-existing health issues, often after a ground-level fall. Risk factors for PFF include osteoporosis, age ≥ 64 years, obesity, prior femoral fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, aseptic stem loosening, heart disease, peptic ulcers, and multiple previous hip surgeries [8,9,10].

The management of PFFs requires an experienced trauma and orthopedic surgeon due to its complexity and high risk of postoperative complications. These complex surgeries are often accompanied by a high complication rate (failure rate) and a high mortality rate (9% in the first year and 60% after 5 years) [8]. Patients diagnosed with PFFs are at risk of developing infection, pressure ulcers, fracture nonunion, prosthesis loosening, thromboembolic complications, depression, and other psychological disorders [8,9,10,11,12]. PFFs are classified according to the Vancouver Classification System, which stratifies them based on location, implant stability and bone quality, thus providing the treatment recommendations according to the specific fracture type (Table 1) [13,14,15].

Table 1.

Modified Vancouver classification system for periprosthetic fractures.

Most PFFs are type B (B1: 29%, B2: 53%, B3: 4%), as they are extremely challenging to treat [16]. The recommended treatment approach for all type B fractures is surgery; type B1 requires open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), while types B2 and B3 necessitate a revision prosthesis in conjunction with ORIF. However, numerous factors guide treatment in everyday clinical practice, including the patient’s condition with comorbidities, functional status, the surgeon’s experience, bone quality, and the type of fracture.

PFFs often lead to a decreased quality of life [17]. The most common outcome measures for PFFs are mortality, healing rate, wound healing time, and surgery-specific outcomes (blood loss, operative time, and adverse events) [18]. A large number of studies have analyzed functional outcomes and quality of life after PFF [5,17,19,20,21,22,23] yet there is still a gap in understanding the quality of life of patients with these fractures [18,24,25]. Most of them have a retrospective design, with limited sample sizes. Qualitative studies are poorly represented [21], and most research focuses predominantly on orthopedic scores and quantitative indicators of functionality. Therefore, this study aimed not only to examine the orthopedic recovery of patients with Vancouver type B PFF, but also to evaluate their quality of life, encompassing their subjective experience of the recovery process, including fear, duration of recovery, the impact of prolonged stays in orthopedic and rehabilitation clinics, in order to assess whether and to what extent patients return to their pre-fracture daily activities.

The 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)

The 36–Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) is a widely used instrument designed to measure health outcomes. Originally developed as part of the Medical Outcomes Study, its primary purpose is to provide an objective assessment of an individual’s quality of life [26]. The SF-36 consists of thirty-six questions. Thirty-five are grouped into eight domains: Physical activity limitations due to health problems; Social activity limitations due to physical or emotional problems; Role activity limitations due to physical health problems; Bodily pain; General mental health; Role activity limitations due to emotional problems; Vitality (energy and fatigue); and General health perceptions [26].

The Physical Component Summary (PCS) includes Physical functioning, Role limitations due to physical health problems, Bodily pain, and General health perceptions. The Mental Component Summary (MCS) includes Vitality, Social functioning, Role limitations due to personal or emotional problems, and Emotional well-being. One question is intended to compare general quality of life now compared to a year ago.

Through this comprehensive approach, the SF-36 provides a detailed understanding of an individual’s overall health and well-being.

The results of each domain (1–5 points) are transformed into standardized values 0–100. Scoring is calculated for each domain, where a higher score indicates a better quality of life. For each domain, a score of 0–33 indicates poor quality of life, 33–66 is considered good quality of life, and 66–100 as excellent quality of life [27].

The reliability and validity of the SF-36 have been confirmed in numerous studies, making it one of the most reliable and most frequently used research instruments for assessing the quality of life of patients with various diseases [28,29,30].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

This was a cross-sectional observational study conducted at the Clinic for Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology, University Clinical Center of Vojvodina.

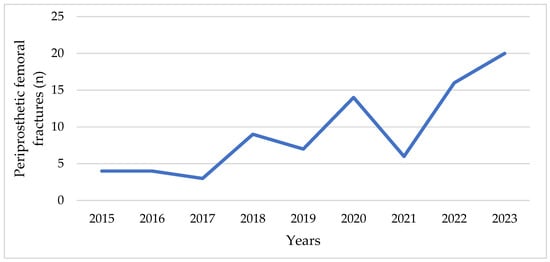

An increase in the number of PFFs has also been observed at our Clinic over the last years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of periprosthetic fractures at the Clinic for Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology of the University Clinical Center of Vojvodina in the period from 2015 to 2023.

Inclusion criteria (experimental group—PFF):

- Age ≥ 65 years

- Vancouver type B proximal PFF

- Surgical treatment at our clinic between January 2016 and December 2022

- Voluntary consent to participate

Exclusion criteria (experimental group—PFF):

- Age < 65 years

- Death prior to follow-up

- Intraoperative fractures

- Cognitive impairment preventing independent survey completion

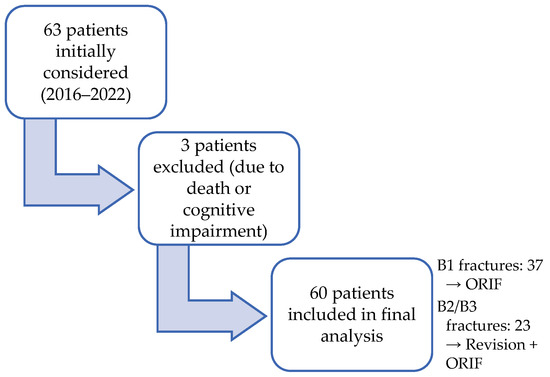

A total of 63 consecutive patients with Vancouver type B periprosthetic femoral fractures were initially screened for eligibility. Three patients were excluded due to death prior to follow-up or cognitive impairment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient recruitment flow (experimental group).

A final sample included 60 patients with PFFs of Vancouver type B (32 females and 28 males, 53% and 47%, respectively), with a mean age of 73.02 ± 8.97 years) who underwent surgery between January 2016 and December 2022 at our center.

The Vancouver classification was used to assess fracture types [14,15]. B1 fractures were surgically treated with ORIF using locking compression plates (LCP). B2 and B3 fractures were treated with revision prosthesis combined with ORIF. The sample included 37 patients with B1, 19 with B2, and 4 with B3-type fractures.

The control group consisted of 30 consecutive patients over 65 years from the same clinic who underwent primary THA for traumatic femoral neck fractures between 2016 and 2022 (17 females, 13 males; mean age 71.36 ± 8.53 years). Patients were matched to the PFF group by age, sex, ASA Physical Status Classification System [31], and trauma status to ensure sample homogeneity.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient baseline characteristics and follow-up.

2.2. Quality of Life Assessment and Data Collection

Quality of life was measured using the validated Serbian translation of 36-Item Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-36) [26,32] with a clinical examination at least 12 months after surgery. The study was conducted by surveying patients during routine follow-up visits at the specialist polyclinic of the University Clinical Center of Vojvodina. Patients completed the questionnaire in a private room. A registered nurse was available to assist if needed.

Patient data were collected from medical records (hospital files, the Clinical Information System—internal hospital system, and the Picture Archiving and Communication System—PACS).

2.3. Statistical Data Analysis

Statistical data processing and analysis were performed using SPSS Statistics version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were calculated for all variables. All SF-36 domain raw scores (1–5) were transformed to standardized 0–100 scores according to the scoring manual.

Pearson correlation was used to determine the correlation between SF-36 domains. The normality of data distribution was checked with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and independent samples t–tests were conducted to compare differences in quality of life between subgroups according to sex, operated leg, and PFF type (B1 vs. B2/B3), as well as between the experimental group (periprosthetic fracture) and the control group (primary THA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Age and Quality of Life

Pearson’s correlation analysis (Table 3) showed significant associations between age and most quality of life domains.

Table 3.

Correlation between patient age and quality of life after PFF surgery.

Age correlated positively with General health perceptions (r = 0.768) and Bodily pain (r = 0.735). Negative correlations were observed between age and Physical functioning (r = −0.806), Role limitations due to physical health problems (r = −0.731), Role limitations due to personal or emotional problems (r = −0.687), Social functioning (r = −0.687), Vitality (Energy/fatigue) (r = −0.762), Emotional well-being (r = −0.827), and the Overall SF-36 score (r = −0.619). These findings indicate that older patients reported better subjective perceptions of general health and less bodily pain, with a decline in physical and emotional functioning, energy and social activities.

3.2. Sex Differences

Independent t–test results (Table 4) showed no significant differences in health status or treatment outcomes between males and females after PFF surgery. Mean SF-36 values were comparable across all domains, indicating that sex did not significantly affect postoperative quality of life in this sample.

Table 4.

Differences in quality of life of patients after PFF surgery by sex.

3.3. Differences in Quality of Life According to Operated Leg

No significant differences were observed between patients with left- and right-sided fractures (Table 5).

Table 5.

Differences in quality of life of patients by operated leg.

3.4. Quality of Life and the Type of PFF Revision

Patients who underwent femoral stem revision combined with osteosynthesis (B2 and B3 fractures) reported higher values in several quality of life domains compared to those who underwent osteosynthesis alone (B1 fractures) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Differences by type of PFF revision.

3.5. Comparison with Primary THA

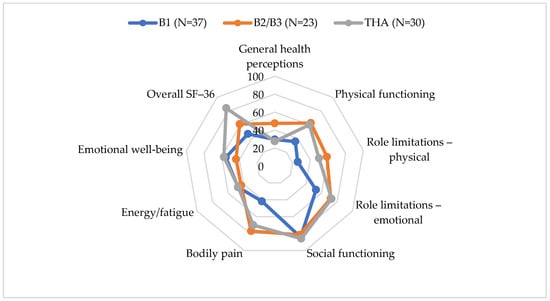

Patients after PFF surgery had significantly lower overall SF-36 scores compared to those who underwent primary THA (t = −5.092, p < 0.0005). The largest difference was observed in the General Health Perceptions domain (t = 4.717, p < 0.0005) (Figure 3, Table 7).

Figure 3.

SF-36 scores by PFF type and THA.

Table 7.

Differences in quality of life after PFF surgery (experimental group) and outcomes after THA (control group).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that the overall quality of life in patients following surgery for PFFs remained significantly lower than that of patients who underwent primary THA. Domains with the lowest scores were physical role limitations and pain. This highlights the enduring effects of complex trauma and revision surgery on physical functioning. Patients who underwent osteosynthesis combined with femoral stem revision (B2 and B3 fractures) reported better outcomes in terms of general health status, energy levels, and pain management than those who underwent osteosynthesis alone (B1 fractures). This suggests that appropriately selected and executed revision procedures may lead to improved functional recovery and enhanced self-perceived health status.

In our study, a total of 60 patients with PFF were included, along with 30 patients who underwent primary THA (control group). The average age of the patients in experimental group was 73 years and 71 years in the control group, which is significant enough to impact their overall quality of life. Some correlations in our study, such as older age being associated with better perceptions of general health and lower pain levels, may seem counterintuitive. This may be a consequence of changes in health expectations, the need for consistency in self-perception and the pursuit of positive self-enhancement, which are common in elderly adults and may evolve over time after treatment [33,34]. These findings can be explained by the concept of ‘response shift’, which is defined as a change in one’s self-evaluation resulting from changes in internal standards, values, or the conceptualization of the target construct [35].

The severity of the injury, the treatment method, and any comorbid conditions influence both treatment outcomes and the quality of life [36,37].

Recommended surgical treatments for PFFs include replacing the femoral shaft and using a longer implant to reconnect the fractured segments. ORIF alone has generally been contraindicated for B2 fractures due to the risk of non-union fracture associated with a loose stem, which often requires long-term immobilization and may lead to the need for further revisions. However, if ORIF could facilitate successful fracture healing without necessitating revision, it would significantly enhance treatment outcomes. Reducing operation time and simplifying the procedure may particularly benefit younger patients who are more likely to require subsequent revisions. Furthermore, ORIF could lower implant costs and decrease the time spent in the operating room [38].

In type B2 PFFs, particularly around cemented polished stems, implant stability can be significantly compromised even with minimal damage to the cement mantle. This occurs because the stabilizing force relies on the integrity of the cement mantle, which is responsible for transferring the load to the cortical walls. Consequently, this significantly impacts treatment outcomes, slows recovery, and diminishes the patient’s overall quality of life [39].

Timely surgery has been shown to significantly improve the prognosis of elderly patients with femoral fractures. It may contribute to reduced perioperative complications, better postoperative recovery, and improved quality of life [40].

In a study of 221 patients with PFFs, Pavlou et al. [41] reported that these fracture patterns require revision with a long stem prosthesis. The stem should span the fracture level by at least two cortical diameters, which is a general rule in surgical practice.

Pavlou et al. [41] and Gitajn et al. [42] report on the benefits of revision surgery for Vancouver B fractures, with better functional outcomes and lower mortality. In contrast, Antoniadis et al. [43] and Joestl et al. [44] reported more favorable outcomes in patients who underwent osteosynthesis alone, with sufficient fragment stability and without the need for prosthesis replacement. Solomon et al. [38] point out that osteosynthesis can achieve similar results to revision surgery in carefully selected patients with a stable femoral stem.

These different findings underscore the importance of an individualized approach: the assessment of prosthesis stability, bone quality and the general condition of the patient remains crucial for the treatment decision. The literature suggests that the choice of fixation technique and stem type significantly influence the outcome. For example, TFMT (Tapered Fluted Modular Titanium) stems have better biomechanical stability compared to standard cemented CB prostheses, which reduces the risk of reoperation and allows a faster return to physical activity. In line with these findings, the results indicate a statistically significant improvement in quality of life in patients undergoing stem replacement compared to those who underwent osteosynthesis alone, which has important clinical implications [39].

A similar age distribution of the patients was also found in the study by Olivo-Rodríguez et al. [11] where the mean age for PFF was 74, but with a significantly smaller number of subjects, 15. These findings are in line with the predictions from the study by Poulsen et al. [45] who indicated an expected increase in the number of patients undergoing primary THA, and therefore an increase in the incidence of PFFs. Thien et al. [46] suggest that the increased incidence of this pathology may be partly attributed to older patients with poorer bone quality, as well as younger patients with greater physical activity demands.

The application of newer surgical techniques, such as stem replacement and osteosynthesis of the femur, leads to better outcomes of surgical treatment and a better quality of life [47,48,49,50].

Patients with osteosynthesis without femoral stem revision have a poorer quality of life than those who undergo osteosynthesis with femoral stem revision. Khan et al. [51] performed a systematic review of 22 studies including 510 fractures classified as B2 and B3 and found that 12.6% of B2 and 4.8% of B3 fractures underwent IF alone. These were associated with a higher reoperation rate compared with revision arthroplasty. This highlights the importance of assessing stem stability during preoperative workup and intraoperative stem testing and ensuring that revision implants are available during surgery.

Ricci et al. reported that the results after surgery for distal PFFs are poorer and associated with a high mortality rate [52].

A large registry-based epidemiological study of over 3 million patients found that revision total hip arthroplasty (rTHA) had a significantly higher complication rate than primary THA (39.46% vs. 27.32%). Postoperative anemia was the most common complication in both groups. The most common indications for rTHA were also dislocation/instability (21.85%) and mechanical loosening (19.74%). The authors point out that the increased risk of complications in revision surgery is partly due to the higher number of comorbidities (e.g., high blood pressure, chronic lung disease) and the technically more complex nature of the procedure itself. Therefore, rTHA is a much more complex procedure with higher risks for the patient, which is to some extent comparable to results of this study. In patients after PFFS (which usually require a revision prosthesis), the results indicate lower scores in several domains of quality of life compared to the control group after primary THA [2].

We further analyzed whether gender, age, and the operated side affect the quality of life. Considering the operated side, in our study the incidence of right hip disease is 56.6%. On the other hand, left-sided fractures were less frequent (43.4%) compared to right-sided (56.6%), and based on the results obtained in relation to the operated leg, there are no significant differences in the quality of life. No statistically significant differences were observed in the total SF-36 score between males and females, (males 68.64/100, females 64.96 ± 15.91, respectively).

Although we did not use the EQ-5D-3L scale, we can compare our results with those of Nieboer et al. [18], who reported that male patients had slightly better postoperative outcomes than women, whereas in our case, there were no such differences. Pavlović et al. [25] showed that patients with revision arthroplasty for Vancouver B2/B3 fractures usually regain mobility and a higher quality of life, with an EQ-5D-5L index of around 0.8, which is consistent with our finding that patients with B2/B3 fractures and combined osteosynthesis have better SF-36 scores than patients with B1 fractures and osteosynthesis alone.

In a study by Zampelis et al. [53], which was conducted on 45 patients (27 males and 18 females), the results showed that men had better functional outcomes than women. As a possible explanation for this result, they stated that men and women value their health differently, as well as that their postoperative expectations are different. Compared with the findings of study by Märdian et al. [54], who analyzed the quality of life after periprosthetic knee fractures, significant differences are observed. In their study, the average SF-36 score was 41 ± 6, indicating a more pronounced impaired quality of life compared to our study group. Also, only 20% of the patients from that study were able to move independently, while the rest required some kind of assistance, which further confirms a greater functional deficit after a knee fracture. Their WOMAC scores also indicate high levels of pain, stiffness, and limitations in daily activities. In contrast to our study, they did not find a significant influence of the type of fracture or comorbidity on the final outcome, while we clearly identified a difference in outcomes depending on the method of treatment and type of fracture. This difference can be partially explained by the larger number of subjects in our study (total of 90 patients vs. 25), but both studies confirm that PFFs significantly impair quality of life, especially in the domain of physical functioning.

Although we did not directly examine risk factors for PFFs, findings from a retrospective cohort study by Ding et al. [8] suggest that some key factors, such as older age, osteoporosis, and previous femoral neck fractures, are associated with a higher incidence of PFF. These risk factors are important because they often occur in patients with reduced functional capacity and therefore may also affect quality of life after treatment. The reduced quality of life in patients with PFF may be partially explained by the presence of these risk factors and comorbidities, which further complicate recovery and affect perceptions of health and function.

It is important to emphasize that the choice of the appropriate surgical method can significantly affect functional recovery and therefore the quality of life of patients, which is consistent with our findings [55].

The results of this study are comparable with the findings of a study that analyzed the impact of fracture-related infections (FRI). That study showed that FRI leads to a significant deterioration in several domains of quality of life, including pain, mobility, and daily activities, as well as an increased rate of complications [56].

In addition, our results indicate that patients who underwent a combination of femoral stem replacement and osteosynthesis have significantly better outcomes in the domains of General health perceptions (p = 0.027), Physical limitations (p = 0.014), Bodily pain (p = 0.042), and Energy/fatigue (p = 0.009), compared to those who underwent osteosynthesis alone. These findings are consistent with the results of a study comparing different treatment methods for B2 fractures, where long-term stabilization (LSRIF) resulted in better outcomes in Harris Hip Score and SF-36 physical and mental scores compared to ORIF [3]. This indicates that the choice of surgical technique must be tailored to the individual patient’s condition, not just the fracture morphology.

The study by Cursaru et al. [57] highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary and personalized approach to the treatment of PFF, indicating the potential of cortical allografts, ORIF, or revision depending on bone quality and implant stability. These observations are consistent with our view that the therapeutic algorithm must be flexible and based on a comprehensive assessment.

Finally, our findings highlight the necessity for early, individualized surgical planning and comprehensive rehabilitation for patients with PFFs, particularly considering the unique characteristics of this population, which often includes elderly individuals. It is essential for healthcare professionals to address both the physical and psychological aspects of postoperative recovery. Standardized, valid, and reliable research instruments specifically designed to assess quality of life, such as the SF-36, can offer valuable insights into patient-centered outcomes.

4.1. Clinical Implications

Early surgery (within 48 h of hospital admission) is associated with significant benefits in terms of lower rates of postoperative complications and risk of death and may provide better functional outcomes [58].

In addition, an individualized treatment approach that takes into account risk factors such as osteoporosis and general health status can significantly improve the rehabilitation process. An adequate therapeutic approach to patients with osteoporosis can reduce the risk of PFF after THA, which emphasizes the need for early diagnosis and intervention in patients at increased risk [59].

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach has recently become essential for rehabilitation programs. Interdisciplinary teams optimize patients’ medical, psychosocial, and physical capacities, including plans for early discharge. Since most femoral fractures occur in older patients, a multidisciplinary rehabilitation strategy that incorporates various specialists is crucial. To ensure the best outcomes, this treatment should commence as soon as the patient is hospitalized and continue throughout the rehabilitation process after discharge [60].

There is a great need to standardize the surgical approach and integrate multidisciplinary protocols to improve functional treatment outcomes and quality of life in patients with PFFs.

4.2. Study Limitations

The relatively small number of patients in both groups may restrict the statistical power and generalizability of the findings to the broader population. The study population was limited to patients who survived and were able to complete the SF-36 survey. Therefore, the results may be influenced by survival and selection bias. Although multivariate analysis was not performed, unadjusted comparisons between groups may be influenced by other factors. Differences in outcomes between B1 and B2/B3 fracture types may be due in part to patient selection, rather than solely to the type of treatment. B2/B3 fractures usually occur in patients with a more complex clinical profile, the presence of comorbidities, poorer bone quality, as well as poorer preoperative functional status, which may contribute to less favorable outcomes regardless of the type of surgery.

Additionally, some patients may have been biased when self-assessing their quality of life. They may have been less precise, anxious during the examination conducted by healthcare professionals, or provided socially desirable responses. In the context of evaluating quality of life, it is crucial to consider socioeconomic factors and the availability of rehabilitation services, as these can significantly influence treatment outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Patients following PFF demonstrate a lower quality of life compared to a control group of patients who have undergone THA after treatment, primarily due to multiple comorbidities and poorer health status. Additionally, patients who underwent both prosthesis replacement and femur osteosynthesis reported significantly better quality of life after treatment reported a better quality of life compared to those who underwent femur osteosynthesis alone. The increase in the incidence of PFFs due to an aging global population requires a holistic approach, individualized surgical planning, and optimized postoperative rehabilitation, which are the basis for improving patients’ functional recovery and quality of life.

More extensive prospective studies are needed to investigate long-term quality of life trends and to optimize treatment protocols for this growing and very sensitive patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.G., M.V. and A.Ć.; Methodology, N.G. and A.Ć.; Validation, N.G., M.V. and A.Ć.; Formal Analysis, N.G., I.L. and S.B.; Investigation, N.G., M.V. and A.Ć.; Resources, M.V.; Data Curation, I.L. and S.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, N.G. and A.Ć.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.V. and S.B.; Visualization, I.L.; Supervision, M.V.; Project Administration, A.Ć. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors’ personal financial means.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Clinical Center of Vojvodina in Novi Sad (decision No. 00-69 from 16 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank all study participants and the medical staff at the Clinic for Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology of the University Clinical Center of Vojvodina who contributed to the care of the patients included in this research. We sincerely thank Arijana Luburić-Cvijanović, Department of Anglistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad, for her professional English-language editing of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Garofalo, S.; Morano, C.; Bruno, L.; Pagnotta, L. A Comprehensive Literature Review for Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): Part 2—Material Selection Criteria and Methods. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, I.; Nham, F.; Zalikha, A.K.; El-Othmani, M.M. Epidemiology of Total Hip Arthroplasty: Demographics, Comorbidities and Outcomes. Arthroplasty 2023, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.-Q.; Li, X.-S.; Fan, M.-Q.; Yao, Z.-Y.; Song, Z.-F.; Tong, P.-J.; Huang, J.-F. Surgical Treatment of Specific Unified Classification System B Fractures: Potentially Destabilising Lesser Trochanter Periprosthetic Fractures. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aprato, A.; Tosto, F.; Comba, A.; Mellano, D.; Piccato, A.; Daghino, W.; Massè, A. The Clinical and Economic Burden of Proximal Femur Periprosthetic Fractures. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2022, 106, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Lanting, B.; Somerville, L.; Hunter, S.W. Evaluating the Functional and Psychological Outcomes Following Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture After Total Hip Arthroplasty. Arthroplast. Today 2022, 18, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Blom, A.; Boulton, C.; Brittain, R.; Clark, E.; Craig, R.; Dawson-Bowling, S.; Deere, K.; Esler, C. The National Joint Registry 16th Annual Report 2019; National Joint Registry: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.M.; Acuña, A.J.; Jan, K.; Forlenza, E.M.; Della Valle, C.J. Trends and Epidemiology in Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Large Database Study. J. Arthroplast. 2025, 40, S255–S261.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Liu, B.; Huo, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, T.; Ma, W.; Li, M.; Han, Y. Risk Factors Affecting the Incidence of Postoperative Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture in Primary Hip Arthroplasty Patients: A Retrospective Study. Am. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg-Larsen, M.; Jørgensen, C.C.; Solgaard, S.; Kjersgaard, A.G.; Kehlet, H. Increased Risk of Intraoperative and Early Postoperative Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture with Uncemented Stems. Acta Orthop. 2017, 88, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramavath, A.; Lamb, J.N.; Palan, J.; Pandit, H.G.; Jain, S. Postoperative Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture around Total Hip Replacements: Current Concepts and Clinical Outcomes. EFORT Open Rev. 2020, 5, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivo-Rodríguez, A.; Tapia-Pérez, H.; Jiménez-Ávila, J. Quality of Life of Patients after Periprosthetic Hip Fracture Surgery. Acta Ortop. Mex. 2012, 26, 174–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jaatinen, R.; Luukkaala, T.; Helminen, H.; Hongisto, M.T.; Viitanen, M.; Nuotio, M.S. Prevalence and Prognostic Significance of Depressive Symptoms in a Geriatric Post-Hip Fracture Assessment. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 1837–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, B.; Madanipour, S.; Subramanian, P. Vancouver B2 Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures around Cemented Polished Taper-Slip Stems—How Should We Treat These? A Systematic Scoping Review and Algorithm for Management. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2025, 111, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, O.H.; Garbuz, D.S.; Masri, B.A.; Duncan, C.P. CLASSIFICATION OF THE HIP. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 30, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, O.H.; Garbuz, D.S.; Masri, B.A.; Duncan, C.P. The Reliability of Validity of the Vancouver Classification of Femoral Fractures after Hip Replacement. J. Arthroplast. 2000, 15, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, H.; Malchau, H.; Herberts, P.; Garellick, G. Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures. J. Arthroplast. 2005, 20, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, A.; Lakra, A.; Murtaugh, T.; Shah, R.P.; Cooper, H.J.; Geller, J.A. The Effect of Periprosthetic Fractures Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty on Long-Term Functional Outcomes and Quality of Life. Arthroplast. Today 2024, 29, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieboer, M.F.; van der Jagt, O.P.; de Munter, L.; de Jongh, M.A.C.; van de Ree, C.L.P. Health Status after Periprosthetic Proximal Femoral Fractures. Bone Jt. J. 2024, 106, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Märdian, S.; Schaser, K.-D.; Gruner, J.; Scheel, F.; Perka, C.; Schwabe, P. Adequate Surgical Treatment of Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures Following Hip Arthroplasty Does Not Correlate with Functional Outcome and Quality of Life. Int. Orthop. 2015, 39, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinov, P.; Volpin, G.; Sevi, R.; Tanchev, P.P.; Antonov, B.; Hakim, G. Surgical Treatment of Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures Following Hip Arthroplasty: Our Institutional Experience. Injury 2015, 46, 1945–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risager, S.K.; Pedersen, T.A.; Viberg, B.; Odgaard, A.; Lindberg-Larsen, M.; Abrahamsen, C. Patient Experiences after Surgically Treated Periprosthetic Knee Fracture in the Distal Femur—An Explorative Qualitative Study. Int. J. Orthop. Trauma Nurs. 2025, 58, 101194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, G.; Tucker, A.; Black, N.D.; McDonald, S.; Molloy, M.; Wilson, D. Outcomes and Predictors of Mortality Following Periprosthethic Proximal Femoral Fractures. Injury 2019, 50, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolle, M.A.; Hörlesberger, N.; Maurer-Ertl, W.; Puchwein, P.; Seibert, F.-J.; Leithner, A. Periprosthetic Fractures of Hip and Knee–A Morbidity and Mortality Analysis. Injury 2021, 52, 3483–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demnati, B.; Chabihi, Z.; Boumediane, E.M.; Dkhissi, S.; Idarrha, F.; Fath Elkhir, Y.; Benhima, M.A.; Abkari, I.; Rafai, M.; Ibn moussa, S.; et al. Psychological Impact of Peri-Implant Fractures: A Cross-Sectional Study. Tunis. Med. 2024, 102, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlović, M.; Bliemel, C.; Ketter, V.; Lenz, J.; Ruchholtz, S.; Eschbach, D. Health-Related Quality of Life (EQ-5D) after Revision Arthroplasty Following Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures Vancouver B2 and B3 in Geriatric Trauma Patients. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 144, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J., Jr.; Sherbourne, C. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual Framework and Item Selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulić, L.; Vujović, M. Examination of the Impact of Characteristics of the Health Issues, Length of Time since Themyocardial Infarction and Comorbidity to the Quality of Life of Diseased of Myocardial Infarction. Prax. Medica 2019, 48, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucis, N.C.; Hays, R.D.; Bhattacharyya, T. Scoring the SF-36 in Orthopaedics: A Brief Guide. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2015, 97, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, Y.H.; Fong, W.W.S.; Lui, N.L.; Yong, S.T.; Cheung, Y.B.; Malhotra, R.; Østbye, T.; Thumboo, J. Validity and Reliability of the Short Form 36 Health Surveys (SF-36) among Patients with Spondyloarthritis in Singapore. Rheumatol. Int. 2016, 36, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, R. Reliability, Validity, and Sensitivity of Short-Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) in Patients with Sick Sinus Syndrome. Medicine 2023, 102, e33979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Statement on ASA Physical Status Classification System. Available online: https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-practice-parameters/statement-on-asa-physical-status-classification-system (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Nikolic, A.; Biocanin, V.; Rancic, N.; Duspara, M.; Djuric, D. Serbian Translation and Validation of the SF-36 for the Assessment of Quality of Life in Patients with Diagnosed Arterial Hypertension. Exp. Appl. Biomed. Res. (EABR) 2023, 24, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyamini, Y.; Burns, E. Views on Aging: Older Adults’ Self-Perceptions of Age and of Health. Eur. J. Ageing 2020, 17, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Gómez, E.; Vicente-Galindo, P.; Martín-Rodero, H.; Galindo-Villardón, P. Detection of Response Shift in Health-Related Quality of Life Studies: A Systematic Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawatzky, R.; Kwon, J.-Y.; Barclay, R.; Chauhan, C.; Frank, L.; van den Hout, W.B.; Nielsen, L.K.; Nolte, S.; Sprangers, M.A.G. Implications of Response Shift for Micro-, Meso-, and Macro-Level Healthcare Decision-Making Using Results of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 3343–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidler-Maier, C.C.; Waddell, J.P. Incidence and Predisposing Factors of Periprosthetic Proximal Femoral Fractures: A Literature Review. Int. Orthop. 2015, 39, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.S.; Caroom, C.T.; Wee, H.; Jurgensmeier, D.; Rothermel, S.D.; Bramer, M.A.; Reid, J.S. Tangential Bicortical Locked Fixation Improves Stability in Vancouver B1 Periprosthetic Femur Fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2015, 29, e364–e370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, L.B.; Hussenbocus, S.M.; Carbone, T.A.; Callary, S.A.; Howie, D.W. Is Internal Fixation Alone Advantageous in Selected B2 Periprosthetic Fractures? ANZ J. Surg. 2015, 85, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakaris, N.K.; Obakponovwe, O.; Krkovic, M.; Costa, M.L.; Shaw, D.; Mohanty, K.R.; West, R.M.; Giannoudis, P.V. Fixation of Periprosthetic or Osteoporotic Distal Femoral Fractures with Locking Plates: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, L.; Ablett, A.D.; Sargeant, H.W.; Smith, T.O.; Johnston, A.T. Does Early Surgery Improve Outcomes for Periprosthetic Fractures of the Hip and Knee? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, G.; Panteliadis, P.; Macdonald, D.; Timperley, J.A.; Gie, G.; Bancroft, G.; Tsiridis, E. A Review of 202 Periprosthetic Fractures—Stem Revision and Allograft Improves Outcome for Type B Fractures. HIP Int. 2011, 21, 021–029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitajn, I.L.; Heng, M.; Weaver, M.J.; Casemyr, N.; May, C.; Vrahas, M.S.; Harris, M.B. Mortality Following Surgical Management of Vancouver B Periprosthetic Fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2017, 31, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, A.; Camenzind, R.; Schelling, G.; Helmy, N. Is Primary Osteosynthesis the Better Treatment of Periprosthetic Fémur Fractures Vancouver Type B2? Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Joestl, J.; Hofbauer, M.; Lang, N.; Tiefenboeck, T.; Hajdu, S. Locking Compression Plate versus Revision-Prosthesis for Vancouver Type B2 Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Injury 2016, 47, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen, N.R.; Mechlenburg, I.; Søballe, K.; Lange, J. Patient-Reported Quality of Life and Hip Function after 2-Stage Revision of Chronic Periprosthetic Hip Joint Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. HIP Int. 2018, 28, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thien, T.M.; Chatziagorou, G.; Garellick, G.; Furnes, O.; Havelin, L.I.; Mäkelä, K.; Overgaard, S.; Pedersen, A.; Eskelinen, A.; Pulkkinen, P.; et al. Periprosthetic Femoral Fracture within Two Years After Total Hip Replacement. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2014, 96, e167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkovic, S.; Stanojlovic, M.; Mitkovic, M.; Radenkovic, M. Dynamic Internal Fixation of the Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures after Total Hip Arthroplasty. Acta Chir. Iugosl. 2004, 51, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenel, A.; Çirci, E.; Kalyenci, A.S.; Barış, A.; Öztürkmen, Y. Evaluation of Variables Influencing Mortality in Periprosthetic Femur Fractures: Do Fracture Type and Surgical Method Affect Mortality? Istanb. Med. J. 2024, 25, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachi, H.; Takegami, Y.; Okura, T.; Tokutake, K.; Nakashima, H.; Mishima, K.; Kasai, T.; Imagama, S. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes of Periprosthetic Fractures Between Cemented vs. Cementless Stem Methods After Initial Total Hip Arthroplasty or Bipolar Hemiarthroplasty: A Multicenter Analysis (TRON Study). Arthroplast. Today 2025, 33, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elashmawy, M.I.; Mostafa, M.A.R. Use of Cemented Standard Stem Arthroplasty for Unstable Intertrochanteric Fractures in Elderly Patients: A Pilot Study. J. Musculoskelet. Surg. Res. 2025, 9, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Grindlay, D.; Ollivere, B.J.; Scammell, B.E.; Manktelow, A.R.J.; Pearson, R.G. A Systematic Review of Vancouver B2 and B3 Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures. Bone Jt. J. 2017, 99, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, W.M. Periprosthetic Femur Fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2015, 29, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampelis, V.; Ornstein, E.; Franzén, H.; Atroshi, I. A Simple Visual Analog Scale for Pain is as Responsive as the WOMAC, the SF-36, and the EQ-5D in Measuring Outcomes of Revision Hip Arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2014, 85, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Märdian, S.; Schaser, K.; Scheel, F.; Gruner, J.; Schwabe, P. Quality of Life and Functional Outcome of Periprosthetic Fractures around the Knee Following Knee Arthroplasty. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cech. 2015, 82, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, K.; Blauth, M.; Joeris, A.; Blumenthal, A.; Rometsch, E. Fracture Fixation versus Revision Arthroplasty in Vancouver Type B2 and B3 Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures: A Systematic Review. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2020, 140, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, M.A.S.; Haidari, S.; IJpma, F.F.A.; Hietbrink, F.; Govaert, G.A.M. What Can They Expect? Decreased Quality of Life and Increased Postoperative Complication Rate in Patients with a Fracture-Related Infection. Injury 2024, 55, 111425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cursaru, A.; Popa, M.; Cretu, B.; Iordache, S.; Iacobescu, G.L.; Spiridonica, R.; Rascu, A.; Serban, B.; Cirstoiu, C. Exploring Individualized Approaches to Managing Vancouver B Periprosthetic Femoral Fractures: Insights from a Comprehensive Case Series Analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e53269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sire, A.; Invernizzi, M.; Baricich, A.; Lippi, L.; Ammendolia, A.; Grassi, F.A.; Leigheb, M. Optimization of Transdisciplinary Management of Elderly with Femur Proximal Extremity Fracture: A Patient-Tailored Plan from Orthopaedics to Rehabilitation. World J. Orthop. 2021, 12, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.S.; Agarwal, A.R.; Kinnard, M.J.; Thakkar, S.C.; Golladay, G.J. The Association of Postoperative Osteoporosis Therapy With Periprosthetic Fracture Risk in Patients Undergoing Arthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fractures. J. Arthroplast. 2023, 38, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-J.; Um, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-H. Postoperative Rehabilitation after Hip Fracture: A Literature Review. Hip Pelvis 2020, 32, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).