Prevalence of Down Syndrome in Croatia in the Period from 2014 to 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holmes, G. Gastrointestinal Disorders in Down Syndrome. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2014, 7, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Down, J.L.H. Observations on an Ethnic Classification of Idiots. Lond. Hosp. Rep. 1866, 3, 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, M.J.; Trotter, T.; Santoro, S.L.; Christensen, C.; Grout, R.W.; Burke, L.W.; Berry, S.A.; Geleske, T.A.; Holm, I.; Hopkin, R.J.; et al. Health Supervision for Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2022057010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; Salehi, M.; Kheirollahi, M. Down Syndrome: Current Status, Challenges and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2016, 5, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonarakis, S.E.; Skotko, B.G.; Rafii, M.S.; Strydom, A.; Pape, S.E.; Bianchi, D.W.; Sherman, S.L.; Reeves, R.H. Down Syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mégarbané, A.; Ravel, A.; Mircher, C.; Sturtz, F.; Grattau, Y.; Rethoré, M.O.; Delabar, J.M.; Mobley, W.C. The 50th Anniversary of the Discovery of Trisomy 21: The Past, Present, and Future of Research and Treatment of Down Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2009, 11, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, T.R.; Bhise, A.; Feingold, E.; Tinker, S.; Masse, N.; Sherman, S.L. Investigation of Factors Associated with Paternal Nondisjunction of Chromosome 21. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2009, 149, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, E.G.; Freeman, S.B.; Druschel, C.; Hobbs, C.A.; O’Leary, L.A.; Romitti, P.A.; Royle, M.H.; Torfs, C.P.; Sherman, S.L. Maternal Age and Risk for Trisomy 21 Assessed by the Origin of Chromosome Nondisjunction: A Report from the Atlanta and National Down Syndrome Projects. Hum. Genet. 2009, 125, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.K.; Stallings, E.B.; Cragan, J.D.; Pabst, L.J.; Alverson, C.J.; Oster, M.E. Narrowing the Survival Gap: Trends in Survival of Individuals with Down Syndrome with and without Congenital Heart Defects Born 1979 to 2018. J. Pediatr. 2023, 260, 113523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, E.J.; Jacques, A.; Wong, K.; Bourke, J.; Leonard, H. Improved Survival in Down Syndrome over the Last 60 Years and the Impact of Perinatal Factors in Recent Decades. J. Pediatr. 2016, 169, 214–220.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzoni, M.; Kinsner-Ovaskainen, A.; Morris, J.; Martin, S. EUROCAT—Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies in Europe: Epidemiology of Down Syndrome 1990–2014; La Placa, G., Spirito, L., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, G.; Buckley, F.; Skotko, B.G. Correction to: Estimation of the Number of People with Down Syndrome in Europe. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Jieping, S.; Tianshu, Z.; Zhijun, Z.; Jingxuan, Z.; Bo, W. Incidence of Down Syndrome by Maternal Age in Chinese Population. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 980627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resta, R.G. Changing Demographics of Advanced Maternal Age (AMA) and the Impact on the Predicted Incidence of Down Syndrome in the United States: Implications for Prenatal Screening and Genetic Counseling. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2005, 133A, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Porodi u Zdravstvenim Ustanovama u Hrvatskoj u 2023. Godini [Births in Health Institutions in Croatia in 2023]; Croatian Institute of Public Health: Zagreb, Croatia, 2024; Available online: https://www.hzjz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/HZJZ_-_porodi_2023._g..pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025). (In Croatian)

- Republic of Croatia. Zakon o Registru Osoba s Invaliditetom [Law on the Register of Persons with Disabilities]; Narodne Novine, No. 63/2022. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2022_06_63_907.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Croatian Institute of Public Health. Međunarodna Klasifikacija Bolesti i Srodnih Zdravstvenih Problema—Deseta Revizija, Svezak 1, 2nd ed.; Translation of: ICD-10—International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Volume 1, Croatian Institute of Public Health: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Croatia. Uredba o Metodologijama Vještačenja [Regulation on Assessment Methodologies]; Narodne novine, No. 96/2023. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2023_08_96_1430.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics. Procjene Stanovništva za 2021. Godinu [Population Estimates for the Year 2021]. Available online: https://podaci.dzs.hr/2022/hr/29032 (accessed on 15 June 2025). (In Croatian).

- Republic of Croatia. Zakon o Profesionalnoj Rehabilitaciji i Zapošljavanju Osoba s Invaliditetom [Law on Professional Rehabilitation and Employment of Persons with Disabilities]; Narodne novine, No. 32/2020. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2020_03_32_696.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Republic of Croatia. Pravilnik o Profesionalnoj Rehabilitaciji i Centrima za Profesionalnu Rehabilitaciju Osoba s Invaliditetom [Ordinance on Professional Rehabilitation and Centers for Professional Rehabilitation of Persons with Disabilities]; Narodne novine, No. 44/2014. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2014_04_44_823.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Republic of Croatia. Pravilnik o Profesionalnoj Rehabilitaciji i Centrima za Profesionalnu Rehabilitaciju Osoba s Invaliditetom [Ordinance on Professional Rehabilitation and Centers for Professional Rehabilitation of Persons with Disabilities]; Narodne novine, No. 75/2018. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/full/2018_08_75_1548.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Republic of Croatia. Zakon o Inkluzivnom Dodatku [Inclusive Allowance Law]; Narodne novine, No. 156/2023. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2023_12_156_2383.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Republic of Croatia. Zakon o Povlasticama u Prometu [Law on Traffic Privileges]; Narodne novine, No. 133/2023. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2023_11_133_1816.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Boyd, P.A.; Devigan, C.; Khoshnood, B.; Loane, M.; Garne, E.; Dolk, H.; EUROCAT Working Group. Survey of Prenatal Screening Policies in Europe for Structural Malformations and Chromosome Anomalies, and Their Impact on Detection and Termination Rates for Neural Tube Defects and Down’s Syndrome. BJOG 2008, 115, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomac, V.; Pušeljić, S.; Kos, M.; Dorner, S.; Pavišić Kezan, R.; Wagner, J. Epidemiološka, citogenetička i klinička obilježja djece sa sindromom Down u području Istočne Hrvatske—Petnaestogodišnje postnatalno iskustvo [Epidemiological, Cytogenetic and Clinical Characteristics of Children with Down Syndrome in Eastern Croatia: Fifteen-Year Postnatal Experience]. Paediatr. Croat. 2021, 65, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EUROCAT Data—Prevalence Charts and Tables. Available online: https://eu-rd-platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/eurocat/eurocat-data/prevalence_en (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Presson, A.P.; Partyka, G.; Jensen, K.M.; Devine, O.J.; Rasmussen, S.A.; McCabe, L.L.; McCabe, E.R. Current Estimate of Down Syndrome Population Prevalence in the United States. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtovic-Kozaric, A.; Mehinovic, L.; Malesevic, R.; Mesanovic, S.; Jaros, T.; Stomornjak-Vukadin, M.; Mackic-Djurovic, M.; Ibrulj, S.; Kurtovic-Basic, I.; Kozaric, M. Ten-Year Trends in Prevalence of Down Syndrome in a Developing Country: Impact of the Maternal Age and Prenatal Screening. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 206, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, D.; Tomić Vrbić, I.; Pucko, S.; Marciuš, A. Down Sindrom: Vodič za Roditelje i Stručnjake [Down Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals]; 4th Revision and Expanded ed. Croatian Down Syndrome Association: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014; pp. 41–83. Available online: https://www.zajednica-down.hr/attachments/article/100/prirucnik_down_sindrom_04_web.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025). (In Croatian)

- Bull, M.J. Down Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2344–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weijerman, M.E.; de Winter, J.P. Clinical Practice: The Care of Children with Down Syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, E.J.; Sullivan, S.G.; Hussain, R.; Petterson, B.A.; Montgomery, P.D.; Bittles, A.H. The Changing Survival Profile of People with Down’s Syndrome: Implications for Genetic Counselling. Clin. Genet. 2002, 62, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.X.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Du, Y. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Defects in People with Down Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2025, 79, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilber, D.; Šarić, D.; Bartoniček, D.; Mihalec, M.; Bakoš, M.; Anić, D.; Belina, D.; Đurić, Ž.; Planinc, M.; Rubić, F.; et al. Izvješće o Radu Referentnog Centra za Pedijatrijsku Kardiologiju Ministarstva Zdravstva Republike Hrvatske [Report on the Work of the Reference Centre for Paediatric Cardiology of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia]. Liječ. Vjesn. 2023, 145 (Suppl. 5), 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilber, D.; Šarić, D.; Bartoniček, D.; Mihalec, M.; Bakoš, M.; Anić, D.; Belina, D.; Đurić, Ž.; Planinc, M. Prikaz Novih Metoda Intervencijskog Liječenja u Referentnom Centru za Pedijatrijsku Kardiologiju Republike Hrvatske [Overview of New Interventional Treatment Methods at the Reference Centre for Paediatric Cardiology of the Republic of Croatia]. Liječ. Vjesn. 2024, 146, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Croatia. Zakon o Potvrđivanju Konvencije o Pravima Osoba s Invaliditetom i Fakultativnog Protokola uz Konvenciju o Pravima Osoba s Invaliditetom [Law on Ratification of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Optional Protocol]; Narodne novine, No. 6/2007. Available online: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/medunarodni/2007_06_6_80.html (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Croatian).

- Chicoine, B.; Rivelli, A.; Fitzpatrick, V.; Chicoine, L.; Jia, G.; Rzhetsky, A. Prevalence of Common Disease Conditions in a Large Cohort of Individuals with Down Syndrome in the United States. J. Patient Cent. Res. Rev. 2021, 8, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

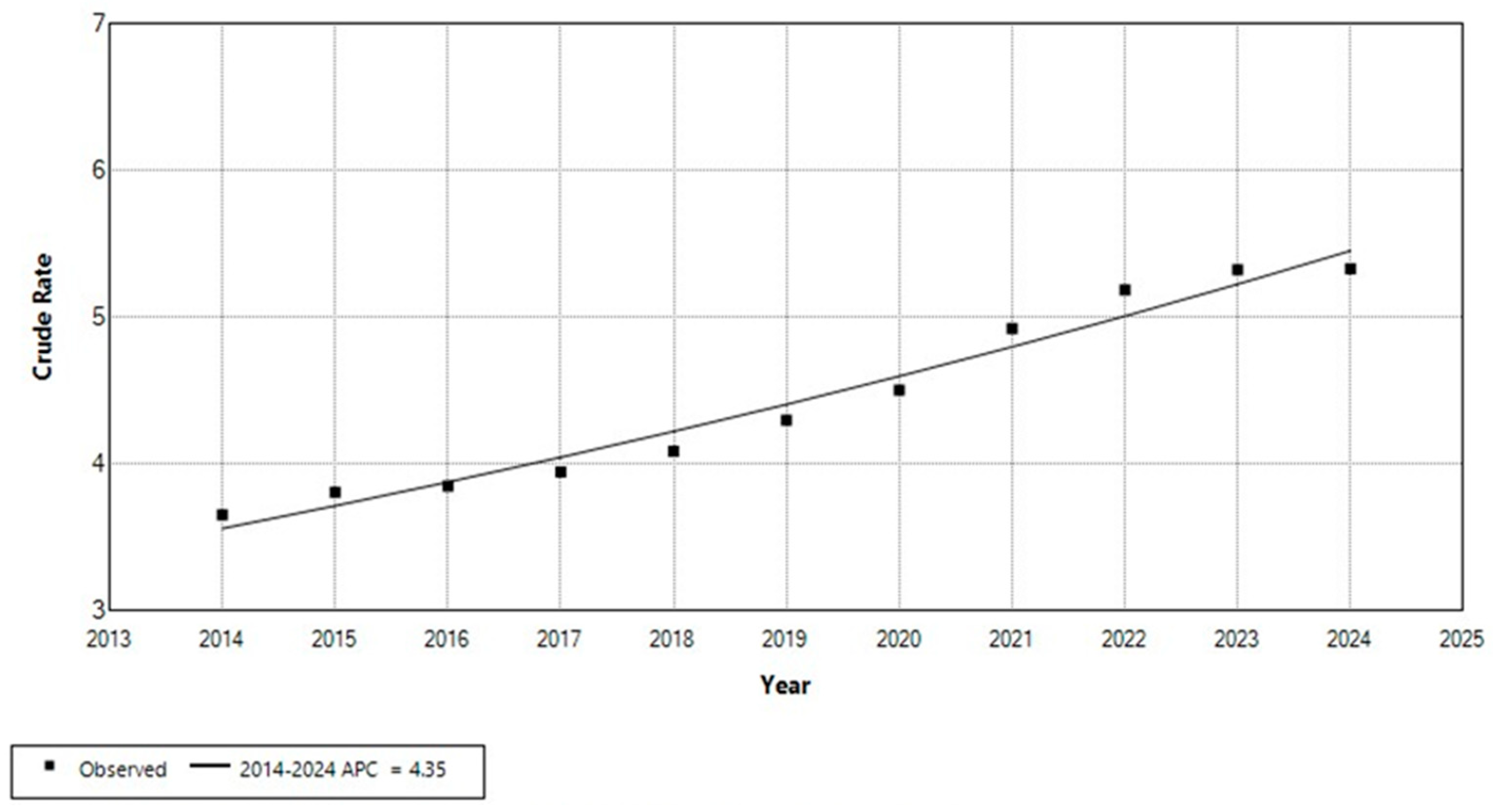

| Year | Total Number of Registered Individuals with Down Syndrome in the Registry of Persons with Disabilities | Total Population of the Republic of Croatia by Year | Prevalence of Down Syndrome in the Total Population of the Republic of Croatia by Year/Per 10,000 Inhabitants | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014. | 1550 | 4,238,389 | 3.7 | 3.475 | 3.839 |

| 2015. | 1602 | 4,203,604 | 3.8 | 3.624 | 3.998 |

| 2016. | 1608 | 4,174,349 | 3.9 | 3.664 | 4.040 |

| 2017. | 1628 | 4,124,531 | 3.9 | 3.755 | 4.139 |

| 2018. | 1672 | 4,087,843 | 4.1 | 3.894 | 4.286 |

| 2019. | 1748 | 4,065,253 | 4.3 | 4.098 | 4.501 |

| 2020. | 1824 | 4,047,680 | 4.5 | 4.299 | 4.713 |

| 2021. | 1907 | 3,871,833 | 4.9 | 4.704 | 5.146 |

| 2022. | 2000 | 3,855,641 | 5.2 | 4.96 | 5.415 |

| 2023. | 2055 | 3,859,686 | 5.3 | 5.094 | 5.554 |

| 2024. | 2058 | 3,859,686 | 5.3 | 5.102 | 5.562 |

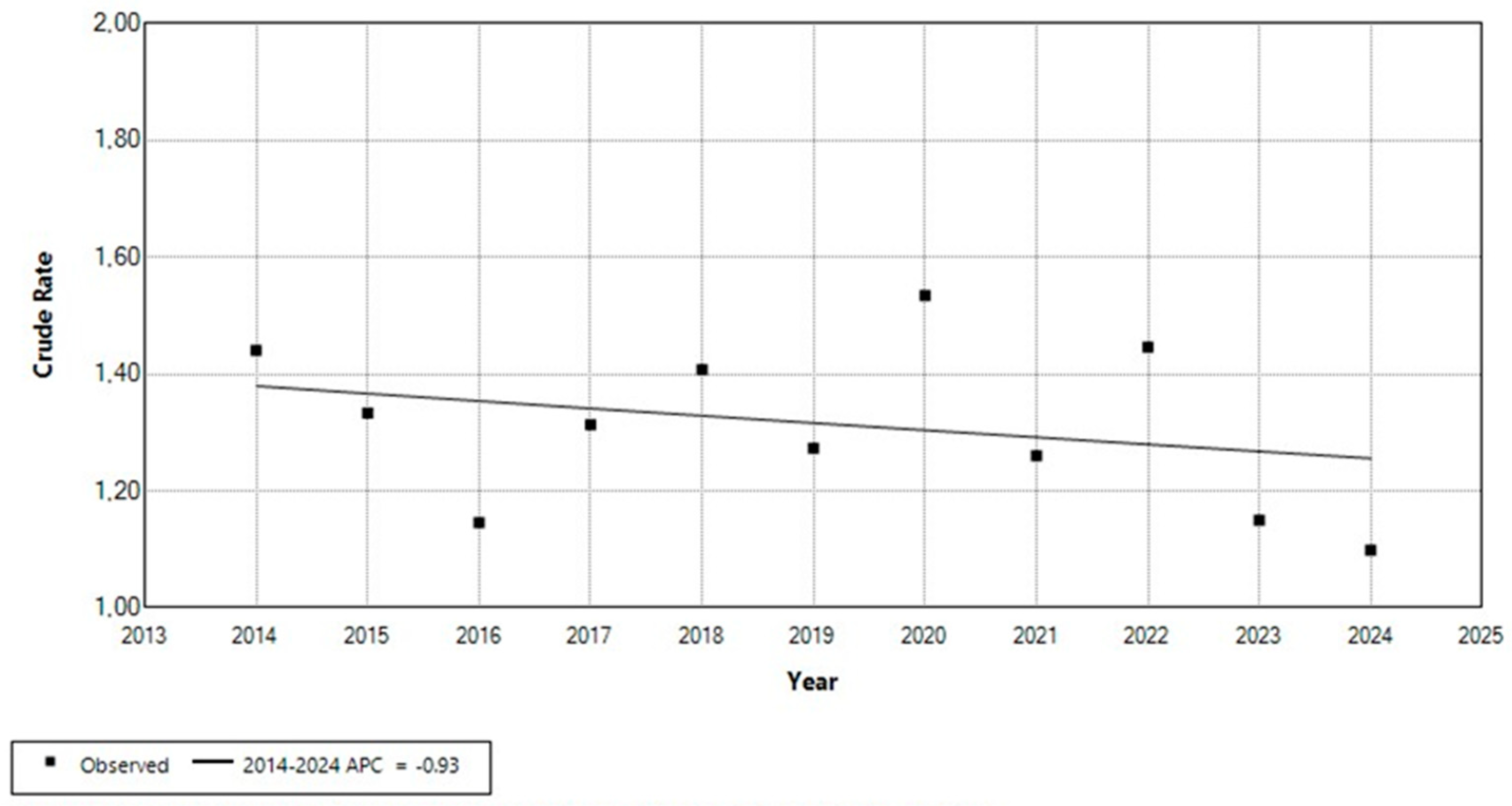

| Year | Number of Live-Born Children with Down Syndrome | Rate per 1000 Live-Born Children | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014. | 57 | 1.4 | 1.067 | 1.815 |

| 2015. | 50 | 1.3 | 0.964 | 1.703 |

| 2016. | 43 | 1.1 | 0.803 | 1.488 |

| 2017. | 48 | 1.3 | 0.942 | 1.685 |

| 2018. | 52 | 1.4 | 1.025 | 1.790 |

| 2019. | 46 | 1.3 | 0.905 | 1.641 |

| 2020. | 55 | 1.5 | 1.129 | 1.94 |

| 2021. | 46 | 1.3 | 0.896 | 1.624 |

| 2022. | 49 | 1.4 | 1.041 | 1.851 |

| 2023. | 37 | 1.2 | 0.78 | 1.521 |

| 2024. | 35 | 1.1 | 0.735 | 1.463 |

| Age Group | Age 0–19 | Age 20–64 | Age 65+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 907 | 1139 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benjak, T.; Vuljanić, A.; Draušnik, Ž.; Barišić, I.; Mach, Z.; Vuković, D.; Đidara, T.; Clarke, J.P.; Vuletić, G. Prevalence of Down Syndrome in Croatia in the Period from 2014 to 2024. Medicina 2025, 61, 1934. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111934

Benjak T, Vuljanić A, Draušnik Ž, Barišić I, Mach Z, Vuković D, Đidara T, Clarke JP, Vuletić G. Prevalence of Down Syndrome in Croatia in the Period from 2014 to 2024. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):1934. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111934

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenjak, Tomislav, Ana Vuljanić, Željka Draušnik, Irena Barišić, Zrinka Mach, Dinka Vuković, Tomislav Đidara, John Patrick Clarke, and Gorka Vuletić. 2025. "Prevalence of Down Syndrome in Croatia in the Period from 2014 to 2024" Medicina 61, no. 11: 1934. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111934

APA StyleBenjak, T., Vuljanić, A., Draušnik, Ž., Barišić, I., Mach, Z., Vuković, D., Đidara, T., Clarke, J. P., & Vuletić, G. (2025). Prevalence of Down Syndrome in Croatia in the Period from 2014 to 2024. Medicina, 61(11), 1934. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111934