Abstract

Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) and fibromyalgia (FM) are underestimated painful musculoskeletal conditions that could impact function and quality of life. A consensus about the most appropriate therapeutic approach is still not reached. Considering the long course of the diseases, prolonged assumption of drugs, such as NSAIDs and pain killers, could increase the risk of adverse events, often leading affected patients and physicians to prefer non-pharmacological approaches. Among these, radial and focused extracorporeal shock waves therapies (ESWT) are widely used in the management of painful musculoskeletal conditions, despite the fact that the mechanisms of action in the context of pain modulation should be further clarified. We performed a scoping review on PubMed using Mesh terms for analyzing the current evidence about the efficacy and effectiveness of ESWT for patients with MPS or FM. We included 19 clinical studies (randomized controlled trials and observational studies); 12 used radial ESWT, and 7 used focused ESWT for MPS. Qualitative analysis suggests a beneficial role of ESWT for improving clinical and functional outcomes in people with MPS, whereas no evidence was found for FM. Considering this research gap, we finally suggested a therapeutic protocol for this latter condition according to the most recent diagnostic criteria.

1. Introduction

Myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) and fibromyalgia (FM) are musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions that significantly affect function and quality of life (QoL). Myofascial pain syndrome has been defined as a regional pain characterized by the presence of one or more myofascial trigger points (MTrPs), or ‘taut bands’, that are a limited number of hyperirritable muscle fibers organized in nodules that can cause spontaneous and referred pain on palpation [1]. The pathophysiology of myofascial pain is not well defined [2]. It has been hypothesized that the sensitization of low-threshold mechanosensitive afferents triggered by a local dysfunction of the motor endplates in the MTrPs area [3] is one of the main pathogenetic mechanisms, as also suggested by the local increase in inflammatory mediators, neuropeptides, cytokines and catecholamines in the tissue around the active MTrPs [4]. These metabolites may contribute to nerve dysfunction, particularly autonomic and sensory small fiber, leading to local vasoconstriction and decreased blood flow as well as referred pain, allodynia, and hyperalgesia [2]. This condition seems to hesitate in characteristic findings at ultrasound evaluation, where trigger points appearing as hyperechoic (hypoperfused) spots in hypoechoic areas [5].

Fibromyalgia is a chronic disease characterized by widespread MSK pain with specific limited soft tissue areas of hyperalgesia and/or allodynia (i.e., tender points). Moreover, affected patients complain of fatigue, sleep disorders, and other somatic and cognitive symptoms [6]. It should be underlined that MPS and FM are often characterized by challenging differential diagnoses because of possible overlaps in pain distribution, duration of symptoms, and physical findings.

Several interventions have been proposed to treat FM and MPS, such as drug therapy, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, and needling (dry needling, trigger point injection). However, the most appropriate and effective approach for these conditions is still debated [7]. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) is a non-invasive physical modality used for several painful MSK disorders [8]. This intervention should exert numerous biological effects with potential clinical benefits in patients with MSK diseases. It was hypothesized that the main biological effect on treated tissue by ESWT is an increase in the permeability of cell membranes and the release of several molecules stimulating tissue regeneration [9], such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF), Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) and the activation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) with angiogenic effects [10]. Finally, ESWT has an important role in pain relief by modulating the release of anti-inflammatory mediators and endorphins that activate descending inhibitory system [11].

The aim of this scoping review is to summarize current evidence about the efficacy and effectiveness of ESWT in patients with FM or MPS.

2. Materials and Methods

In performing this scoping review, we followed the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines [12].

2.1. Search Strategy

We planned a search on PubMed (Public MedLine, run by the National Center of Biotechnology Information, NCBI, of the National Library of Medicine of Bethesda, Bethesda, MD, USA) with ad hoc search strings with selected keywords for FM, MPS, and ESWT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy.

2.2. Study Selection

According to the study objective, we defined the characteristics of the sources of evidence, considering for eligibility any research published in the medical literature until 31 December 2021 and including only those in the English language and conducted on humans (Table 2).

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Clinical research, including interventional (randomized or non-randomized controlled clinical trials) and observational studies, were selected. Research findings from each included study were qualitatively analyzed.

3. Results

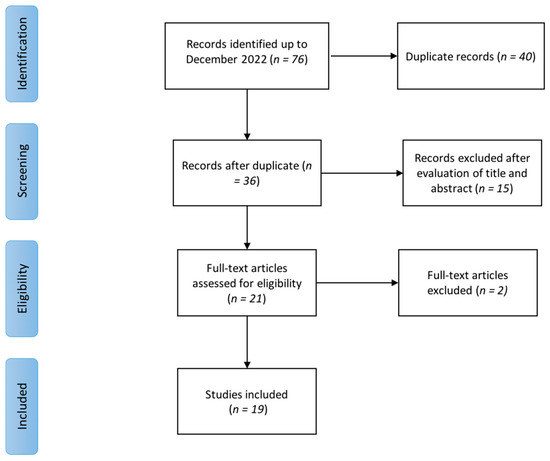

Seventy-six items were initially found. After duplicate removal, 35 records remained. We screened them on the basis of titles and abstracts for inclusion/exclusion criteria, and 14 studies were excluded. After full-text reading, we excluded another two articles because the authors did not specify the type of ESWT used. Finally, we included in this review 19 studies published between 2012 and 2021. None of the trials involving people with FM met the eligibility criteria. Among those including people with MPS, 12 used radial ESWT (rESWT), and 7 used focused ESWT (fESWT). Figure 1 summarizes the selection process of the included papers. Table 3 and Table 4 report the characteristics and main findings of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature review process.

Table 3.

Main characteristics and key findings of the included studies about Radial ESWT for myofascial pain syndrome.

Table 4.

Main characteristics and key findings of the included studies about Focused ESWT for myofascial pain syndrome.

3.1. Radial ESWT

Of the 12 studies investigating the effectiveness of rESWT for the management of patients with MPS, 10 are RCTs (1 pilot) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22], one is a case-control study [23], and one is a retrospective study [24] (see Table 3 for further details). Two RCTs compared rESWT with laser therapy reporting a reduction in pain and disability with both modalities [13,14]. Two RCTs compared rESWT with ultrasound therapy (US), showing that rESWT was equally effective to US in reducing pain, reducing disability, and improving QoL and that both techniques were more effective than sham treatment or exercise alone [15,16]. Another RCT compared rESWT to a combination of hot packs, Trans Cutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), and US and showed that rESWT was more effective in reducing pain and improving sleep quality, disability, depression, and QoL [17]. Taheri et al. 2021 compared rESWT with phonophoresis and reported that both techniques effectively decreased pain and neck disability with the superiority of rESWT [18]. Three RCTs compared rESWT with dry needling (DN) reporting that both interventions were effective in reducing pain and disability [19,20,21]. One of these trials reported that DN could be associated with post-treatment soreness [19]. Another RCT compared rESWT with corticosteroid trigger point injection (TPI) and reported that after one month of treatment, rESWT was more effective in reducing pain and disability and improving QoL [22].

3.2. Focused ESWT

Of the seven studies investigating the efficacy and effectiveness of fESWT, five were RCT [25,26,27,28,29], and two were retrospective studies [30,31] (see Table 4 for further details). Most RCTs [25,26,27,28] investigated the efficacy of fESWT on neck pain, particularly in the upper trapezius, while only one study [29] analyzed the treatment on gastrocnemius–soleus muscle. Ji et al. [26] and Park et al. [27] compared fESWT with ineffective and low energy fESWT, respectively, reporting a significant improvement in pain and NDI score in the intervention groups, although using different treatment protocols. At the same time, Kamel et al. [28] found that combined treatment with 1% topical diclofenac gel and fESWT significantly improved pain, neck ROM, and PPT compared to 1% topical diclofenac gel only in the same population. The results of the study by Jeon et al. [25] suggest no significant between-group difference in terms of pain measures and neck mobility 1 week after the first and the third treatment. Finally, Moghtaderi et al. [29] reported that the treatment of gastroc–soleus trigger points in patients with plantar fasciitis showed better results on pain (VAS) and activity (modified Roles and Maudsley score) at 8 weeks after the last treatment compared to control group where only heel region was treated.

Two observational studies investigated the effectiveness of fESWT in the treatment of MPS in the low back (quadratus lumborum) [30] and the upper part of the unilateral trapezius [31]. Hong et al. [30] compared an interventional protocol of fESWT with corticosteroids (CS) TPI. Authors found that fESWT was more effective than control in reducing pain and increasing PPT at the end of treatment and at 1-month follow-up, but no difference was found for disability measures (ODI, RM score, QBS). Yalcin [31] compared ESWT plus exercise with kinesiotaping (KT) plus exercise and exercise, only reporting better results for patients receiving ESWT plus exercise in terms of pain and contralateral neck lateral flexion.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first PRISMA-driven scoping review aiming to investigate the efficacy and effectiveness of ESWT in the treatment of patients with MPS or FM.

First of all, we must stress that although there are numerous studies dealing with the efficacy of ESWT in patients with MPS in the literature, no paper has aimed to evaluate this intervention in people with FM.

Of note, starting from an overview of included studies, a substantial issue concerned the heterogeneity of treatment protocols, particularly in terms of the number of sessions, intervals between sessions, number of SW administered per TrP, and intensity. About rESWT, shock waves number ranged from 1000 to 4500 (most authors administered 2000 SW; Aktürk et al., 2018, Luan et al., 2019, Rahbar M. et al., 2021, Taheri P. et al., 2021). This intervention was usually provided once a week for 3 weeks or sometimes for four sessions, while only Gezginaslan et al. carried out seven sessions with 3-day intervals. For fESWT, the number of SW used ranged from 1000 to 3000, while the intensity ranged from 0.056 to 0.25 mJ/mm2. Considering the number of sessions, authors generally performed one session per week for 3 weeks (Jeon et al., 2012, Moghtaderi et al., 2014, Hong et al., 2017, Kiraly et al., 2018, Ümit Yalçın 2021).

Among studies included in our review (15 RCTs, four observational studies), 16 compared ESWT to other interventions, while two studies compared this intervention to sham ESWT. Moreover, in an observational retrospective study, no treatment was administered to the control group.

Observational studies comparing ESWT to another intervention reported that both focused and radial modalities were more effective than TPI, KT, and physical agents in MPS patients in terms of pain, mobility, and disability.

On the other hand, results from clinical trials investigating the efficacy of ESWT in MPS people are conflicting. In the RCTs comparing ESWT versus placebo (sham, ineffective ESWT for intensity or application site), both radial and focused modalities seem to significantly improve pain in people with MPS.

Regarding evidence about rESWT in comparison with DN, laser therapy combined with stretching, and therapeutic exercise, no significant differences were reported in terms of pain relief and disability, while rESWT seemed significantly more effective than TPI or a combination of physical agents (HP + TENS + US therapy or US therapy + hot pack) in terms of improvements of pain, fatigue, depression, sleep quality, disability, and QoL in patients with MPS.

RCTs investigating the efficacy of fESWT versus other interventions reported that this treatment modality was not better than TPI combined with TENS in terms of pain relief and mobility, while it was more effective than laser therapy in improving pain, disability, and QoL in patients with trapezius MPS. Moreover, the same intervention significantly improved pain and mobility compared to topical NSAIDs.

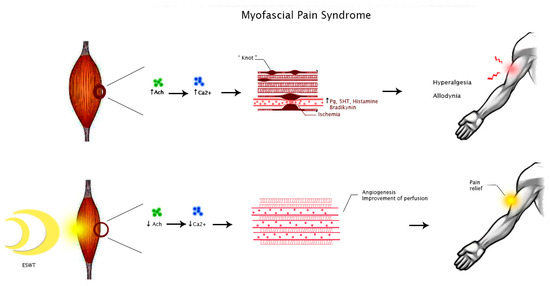

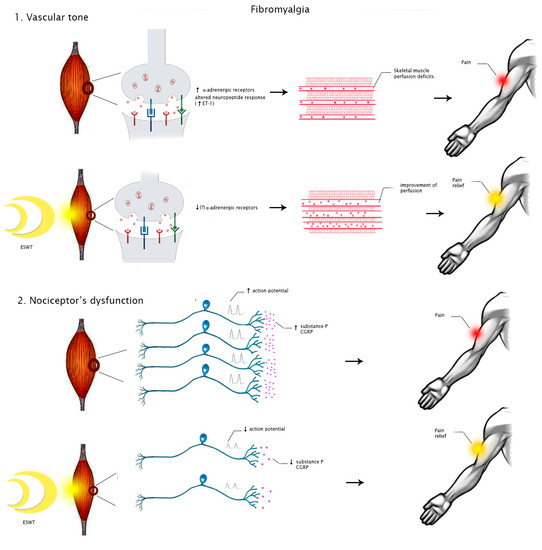

It was hypothesized that several mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of clinical manifestations of MPS and FM might be addressed by different ESWT modalities.

Myofascial pain syndrome was described as muscle pain in different body regions reproduced by pressure on TrP, which are localized hardenings in skeletal muscle tissue. This condition may originate from muscular injury due to intense contractions or repetitive low-intensity overload, inducing an excessive release of acetylcholine by the neuromuscular endplate [32]. This event triggers a prolonged depolarization of muscle fibers, increasing calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and maintaining contraction with the formation of a so-called “knot”, which compresses local capillaries producing ischemia [33]. Ischemia, in turn, furtherly damages the dysfunctional endplate as well as induces the release of inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin, prostaglandins, serotonin, and histamine, leading to peripheral sensitization with hyperalgesia and allodynia [34].

On the contrary, pathogenic mechanisms underlying FM are still unclear. The characteristic tender points are considered as areas of tenderness symmetrically located in specific body parts that do not cause referred pain after stimulation. Recent studies suggest that various agents acting on central (psychological and cognitive-emotional factors) and peripheral nervous systems, including small nerve fibers (inflammatory mediators), can lead to neuromorphological modifications and pain dysperception [35]. Small fiber neuropathy can impair small blood vessels’ function through upregulation of α-adrenergic receptors and altered neuropeptide responses. This mechanism could explain impaired skeletal muscle perfusion, pain, and fatigue in patients with FM [36].

Considering that FM and MPS share some clinical and pathophysiological features, there might be a rationale for using physical agents, including ESWT, in the management of these conditions. Indeed, ESWT has documented effects on several MSK disorders, including the stimulation of angiogenesis with consequently improved perfusion of ischemic tissues.

However, the biological effects of SW targeting pathogenic mechanisms of FM and MPS are still unclear. It is possible to speculate that ESWT may modulate ion influx, particularly of calcium, with consequent improvement of perfusion and promoting angiogenesis. These events might reduce local ischemia, enhancing tissue healing [37]. Moreover, this intervention seems to directly modulate nociception by producing a transient dysfunction of the nociceptor action potential [38]. Therefore, these mechanisms might justify the clinical benefits of this treatment on pain relief in people with MPS or FM (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Hypothesized mechanisms of action of ESWT in people with MPS. Abbreviations: Ach, acetylcholine; Ca2+, calcium ion; Pg, prostaglandins; 5HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

Figure 3.

Hypothesized mechanisms of action of ESWT in people with FM. Abbreviations: ET-1, endothelin 1; CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Despite our scoping review being the first comprehensive analysis of the role of both ESWT modalities in MPS and FM, some years ago, Ramon et al. already published an article dealing with this topic, proposing an ESWT protocol for a small cohort of FM patients [33]. In particular, the authors suggested performing from 1000 to 1500 SW for each of the three most painful points selected. Therefore, the patient should receive from 3000 to 4500 SW overall. However, this paper dates back before the publication of the new diagnostic criteria for FM, where pain must be present in at least four or five body regions [39]. If we applied this protocol to FM patients according to new diagnostic criteria, this approach would be too intense, thus compromising treatment compliance. We propose, according to available treatment protocols for MPS, that the suggested number of SW (3000 for fESWT, 4500 for rESWT) should be equally distributed for each painful region (i.e., 600–900 SW for five regions or 750–1100 SW for four regions, respectively) with SW intensity tailored according to patient tolerability. However, the evidence gaps about the minimum number of SW and ESWT intensity to obtain clinical benefits in different MSK disorders still persist. Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify the role and the best ESWT modality and parameters for the treatment of patients affected by MPS and FM.

5. Conclusions

Myofascial pain syndrome and FM are two complex conditions requiring challenging management. By considering the hypothesized pathophysiological mechanisms, the administration of ESWT was proposed for improving pain and disability in patients affected by these conditions, particularly MPS. Indeed, our scoping review suggests that ESWT could have a role in relieving pain and improving functional outcomes by modulating biological mechanisms of pain, inflammation, and angiogenesis in MPS. However, our results show that a widely accepted therapeutic schedule for both radial and fESWT has not been defined so far. Finally, considering the lack of evidence about the use of ESWT in people with FM, we proposed a new treatment protocol, based on the most recent diagnostic criteria taking into account patients’ tolerability, that needs to be investigated in future trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., G.I., and M.P.; methodology, M.P., S.L., and F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., S.L., and G.T.; writing—review and editing, A.M., G.I., and F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Francesca Elsa Allibrio, Gabriella Serlenga, and Massimo Centaro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Poveda-Pagán, E.J.; Lozano-Quijada, C.; Segura-Heras, J.V.; Peral-Berna, M.; Lumbreras, B. Referred Pain Patterns of the Infraspinatus Muscle Elicited by Deep Dry Needling and Manual Palpation. J. Altern Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.W.; Peng, B.G.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.Q.; Jia, D.L.; Jiang, H.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.G.; Liu, R.G.; Li, Y.; et al. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of myofascial pain syndrome. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 2077–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, F.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Badughaish, A.; Pan, X.; Zhang, L.; Qi, F. The pathophysiological nature of sarcomeres in trigger points in patients with myofascial pain syndrome: A preliminary study. Eur. J. Pain. 2020, 24, 1968–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.P.; Danoff, J.V.; Desai, M.J.; Parikh, S.; Nakamura, L.Y.; Phillips, T.M.; Gerber, L.H. Biochemicals associated with pain and inflammation are elevated in sites near to and remote from active myofascial trigger points. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, D.F.; Boutin, R.D.; Chaudhari, A.J. Assessmen.nt of Myofascial Trigger Points via Imaging: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 100, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, M.J.; Krebs, E.E. Fibromyalgia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, ITC33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenhaver, S.L.; Walker, M.J.; Rettig, C.; Davis, J.; Nelson, C.; Su, J.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Hebert, J.J. The association between dry needling-induced twitch response and change in pain and muscle function in patients with low back pain: A quasi-experimental study. Physiotherapy 2017, 103, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rha, D.W.; Shin, J.C.; Kim, Y.K.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, Y.U.; Lee, S.C. Detecting local twitch responses of myofascial trigger points in the lower-back muscles using ultrasonography. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 1576–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryskalin, L.; Morucci, G.; Natale, G.; Soldani, P.; Gesi, M. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Pain-Relieving Effects of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy: A Focus on Fascia Nociceptors. Life 2022, 12, 743.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschermann, I.; Noor, S.; Venturelli, S.; Sinnberg, T.; Mnich, C.D.; Busch, C. Extracorporal Shock Waves Activate Migration, Proliferation and Inflammatory Pathways in Fibroblasts and Keratinocytes, and Improve Wound Healing in an Open-Label, Single-Arm Study in Patients with Therapy-Refractory Chronic Leg Ulcers. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017, 41, 890–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simplicio, C.L.; Purita, J.; Murrell, W.; Santos, G.S.; Dos Santos, R.G.; Lana, J.F.S.D. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy mechanisms in musculoskeletal regenerative medicine. J. Clin. Orthop Trauma. 2020, 11, S309–S318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taheri, P.; Vahdatpour, B.; Andalib, S. Comparative study of shock wave therapy and Laser therapy effect in elimination of symptoms among patients with myofascial pain syndrome in upper trapezius. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2016, 5, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, M.; Bender, T.; Hodosi, K. Comparative study of shockwave therapy and low-level laser therapy effects in patients with myofascial pain syndrome of the trapezius. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 2045–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktürk, S.; Kaya, A.; Çetintaş, D.; Akgöl, G.; Gülkesen, A.; Kal, G.A.; Güçer, T. Comparision of the effectiveness of ESWT and ultrasound treatments in myofascial pain syndrome: Randomized, sham-controlled study. J. Phys. Ther Sci. 2018, 30, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahbar, M.; Samandarian, M.; Salekzamani, Y.; Khamnian, Z.; Dolatkhah, N. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy versus standard care in the treatment of neck and upper back myofascial pain: A single blinded randomised clinical trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2021, 35, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezgİnaslan, Ö.; GÜmÜŞ Atalay, S. High-Energy Flux Density Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Versus Traditional Physical Therapy Modalities in Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Randomized-controlled, Single-Blind Trial. Arch. Rheumatol. 2019, 35, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, P.; Naderi, M.; Khosravi, S. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Versus Phonophoresis Therapy for Neck Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Anesth Pain Med. 2021, 11, e112592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.; Kinsella, S.; McEvoy, J. The effects of dry needling and radial extracorporeal shockwave therapy on latent trigger point sensitivity in the quadriceps: A randomised control pilot study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2019, 23, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luan, S.; Zhu, Z.M.; Ruan, J.L.; Lin, C.N.; Ke, S.J.; Xin, W.J.; Liu, C.C.; Wu, S.L.; Ma, C. Randomized Trial on Comparison of the Efficacy of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy and Dry Needling in Myofascial Trigger Points. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manafnezhad, J.; Salahzadeh, Z.; Salimi, M.; Ghaderi, F.; Ghojazadeh, M. The effects of shock wave and dry needling on active trigger points of upper trapezius muscle in patients with non-specific neck pain: A randomized clinical trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2019, 32, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftekharsadat, B.; Fasaie, N.; Golalizadeh, D.; Babaei-Ghazani, A.; Jahanjou, F.; Eslampoor, Y.; Dolatkhah, N. Comparison of efficacy of corticosteroid injection versus extracorporeal shock wave therapy on inferior trigger points in the quadratus lumborum muscle: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wu, J. Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders by Ultrashort Wave and Extracorporeal Shock Wave: A Comparative Study. Med. Sci Monit. 2020, 26, e923461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, A.T.; Lima, M.D.C.; Dias, C.B. Predictive factors of response in radial Extracorporeal Shock-waves Therapy for Myofascial and Articular Pain: A retrospective cohort study. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2021, 34, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.H.; Jung, Y.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, J.S.; Mun, J.H.; Park, W.Y.; Seo, C.H.; Jang, K.U. The effect of extracorporeal shock wave therapy on myofascial pain syndrome. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 36, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, H.M.; Kim, H.J.; Han, S.J. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in myofascial pain syndrome of upper trapezius. Ann. Rehabil Med. 2012, 36, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, K.D.; Lee, W.Y.; Park, M.H.; Ahn, J.K.; Park, Y. High- versus low-energy extracorporeal shock-wave therapy for myofascial pain syndrome of upper trapezius: A prospective randomized single blinded pilot study. Medicine 2018, 97, e11432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, F.H.; Basha, M.; Alsharidah, A.; Hewidy, I.M.; Ezzat, M.; Aboelnour, N.H. Efficacy of Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy on Cervical Myofascial Pain Following Neck Dissection Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghtaderi, A.; Khosrawi, S.; Dehghan, F. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy of gastroc-soleus trigger points in patients with plantar fasciitis: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2014, 3, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.O.; Park, J.S.; Jeon, D.G.; Yoon, W.H.; Park, J.H. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Versus Trigger Point Injection in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain Syndrome in the Quadratus Lumborum. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 41, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yalçın, Ü. Comparison of the effects of extracorporeal shockwave treatment with kinesiological taping treatments added to exercise treatment in myofascial pain syndrome. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2021, 34, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwin, R. Botulinum toxin treatment of myofascial pain: A critical review of the literature. Curr. Pain. Headache Rep. 2012, 16, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramon, S.; Gleitz, M.; Hernandez, L.; Romero, L.D. Update on the efficacy of extracorporeal shockwave treatment for myofascial pain syndrome and fibromyalgia. Int J. Surg. 2015, 24, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travell, J.G.; Simons, D.G. Myofascial Pain Dysfunction the Trigger Point Manual, 2nd ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Marotto, D.; Atzeni, F. Fibromyalgia: An update on clinical characteristics, aetiopathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayston, R.; Czanner, G.; Elhadd, K.; Goebel, A.; Frank, B.; Üçeyler, N.; Malik, R.A.; Alam, U. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of small fiber pathology in fibromyalgia: Implications for a new paradigm in fibromyalgia etiopathogenesis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2019, 48, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, H.; Zwetzich, I.; Tilkorn, D.J.; Kolbenschlag, J.; Hauser, J.; Goertz, O.; Spindler, N.; Langer, S.; Ring, A. Effects of Extracorporeal Shock Waves on Microcirculation and Angiogenesis in the in vivo Wound Model of the Diver Box. Eur. Surg. Res. 2021, 62, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausdorf, J.; Lemmens, M.A.; Heck, K.D.; Grolms, N.; Korr, H.; Kertschanska, S.; Steinbusch, H.W.; Schmitz, C.; Maier, M. Selective loss of unmyelinated nerve fibers after extracorporeal shockwave application to the musculoskeletal system. Neuroscience 2008, 155, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Häuser, W.; Katz, R.L.; Mease, P.J.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Walitt, B. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 46, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).