Abstract

Every woman needs to know about the importance of the function of pelvic-floor muscles and pelvic organ prolapse prevention, especially pregnant women because parity and labor are the factors which have the biggest influence on having pelvic organ prolapse in the future. In this article, we searched for methods of training and rehabilitation in prepartum and postpartum periods and their effectiveness. The search for publications in English was made in two databases during the period from August 2020 to October 2020 in Cochrane Library and PubMed. 77 articles were left in total after selection—9 systematic reviews and 68 clinical trials. Existing full-text papers were reviewed after this selection. Unfinished randomized clinical trials, those which were designed as strategies for national health systems, and those which were not pelvic-floor muscle-training-specified were excluded after this step. Most trials were high to moderate overall risk of bias. Many of reviews had low quality of evidence. Despite clinical heterogeneity among the clinical trials, pelvic-floor muscle training shows promising results. Most of the studies demonstrate the positive effect of pelvic-floor muscle training in prepartum and postpartum periods on pelvic-floor dysfunction prevention, in particular in urinary incontinence symptoms. However more high-quality, standardized, long-follow-up-period studies are needed.

1. Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) affects about 50% of women undergoing routine gynecological examination [1]. It is a common condition among parous women and has negative effect on the quality of life in general and especially affecting sexual life and self-confidence. The amount of POP is likely to increase in the future. It is thought that in 2050 the number of women with POP in the USA will increase by about 46% [2].

Main POP risk factors are parity, advancing age, obesity, and others—race and ethnicity, collagen abnormalities, hysterectomy, elevated intraabdominal pressure, and family history [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Most of the POP risk factors are unchangeable, which emphasizes the role of POP prevention. Even though the incidence of POP increases with age, women at young age should start intervening to prevent this condition from happening in the future [3,5,9]. Every woman needs to know about the importance of the function of pelvic-floor muscles (PFM) and POP prevention, especially pregnant women since parity and labor are the factors which have the biggest influence on having POP in the future [3,4,9,11]. Compared to natural delivery, Cesarean delivery mode is not completely protective [12]. There are other health problems such as urinary incontinence (UI), anal incontinence (AI), or sexual disfunction which usually goes with POP and has similar risk factors and etiology. POP is one of the most common diagnoses composing pelvic-floor dysfunction (PFD). According to the International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) and the International Continence Society (ICS), who made a joint report on the terminology for Female Pelvic-Floor Dysfunction, PFD is a wider term covering the following diagnosis: POP, urodynamic stress incontinence (SUI), detrusor overactivity, bladder oversensitivity, voiding dysfunction, recurrent urinary tract infections, and also symptoms such as anal incontinence, dyspareunia, vaginal laxity, and perineal and pelvic pain [13]. Every pregnant woman should learn how to prevent pelvic-floor trauma during labor and how to rehabilitate PFM after labor. PFM training (PFMT) has promising results in POP and PFD prevention and even treatment in early stages of these conditions. Although there is a lack of long-term follow-up studies, existing clinical trials and consensus of experts shows compliance with the use of PFMT [14,15]. In some countries, there are pregnancy and post-partum-orientated pelvic-floor rehabilitation (PFR) programs which contain PFMT. According to the “International Survey Questionnaire on Pelvic-Floor Rehabilitation After Childbirth”, countries in Europe are much more likely to recommend and fund pelvic-floor rehabilitation programs after birth than USA or Asian countries [16]. In Lithuania, we do not have national programs of pelvic physical therapy for patients before and early after birth. In this review, we explored methods of training and rehabilitation in prepartum and postpartum periods and their effectiveness.

2. Search Methods

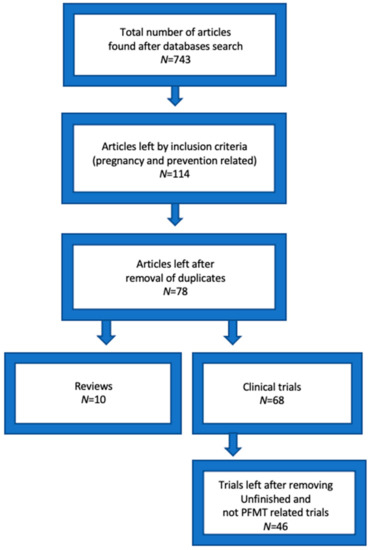

The search for publications in English was made in two databases during the period from August 2020 to October 2020 in Cochrane Library and PubMed. Keywords for the search were different combinations of the following phrases: “woman pelvic-floor rehabilitation” and “prolapse prevention after delivery”. The selected articles met the following criteria: prepartum, delivery, or postpartum-related (words: pregnancy, obstetric, antenatal, postnatal, delivery, prepartum, postpartum, primiparous, childbirth, obstetrical perineal tears were mentioned in the article title) and prevention-related (words: training, exercise, prevention, treatment, physiotherapy, pelvic-floor interventions, rehabilitation). The titles of selected articles, abstracts, and full-text articles were screened by two independent reviewers.

At the beginning, a keyword search was conducted in “Medical subject headings” (MeSH) tree, keywords “pelvic floor dysfunction” and “pelvic organs prolapse” were suggested, but no keywords related with pelvic-floor rehabilitation during or after pregnancy were found. Keywords such as “pelvic floor dysfunction prevention prepartum”; “pelvic floor rehabilitation postpartum”; were used while researching Cochrane Library and PubMed, but the search results were small numbers of publications and did not suit the desirable theme. The most promising results appeared after looking for the most suitable keywords for this research “woman pelvic floor rehabilitation”, “pelvic floor dysfunction prevention after delivery”.

By using “woman pelvic floor rehabilitation” in the Cochrane library database, 5 Cochrane reviews from the period from 2008 to 2018 were found but none of them were prepartum, delivery, or postpartum and prevention-related. 213 clinical trials from the period from 1991 to 2020 were found, of which only 30 were prepartum, delivery, or postpartum and prevention-related.

By using “pelvic floor dysfunction prevention after delivery” no reviews were found, only 39 clinical trials of which 17 met the above-mentioned criteria.

By using “woman pelvic floor rehabilitation” in the PubMed database and using a systematic review filter, 92 articles from the period from 1998 to 2020 were found. Only 9 of them met the criteria. There were 380 clinical trials found, using clinical trial filter from 1984 to 2020 period. 51 of them were prepartum, delivery or postpartum-related.

By using “pelvic floor dysfunction prevention after delivery” 4 systematic reviews were found, 3 of them were related to prolapse and delivery, but none of them were related to prevention. There were 10 clinical trials, of which 6 met the criteria.

After comparing selected articles from two databases and removing repeating articles, 77 articles were left in total as well as 9 systematic reviews and 68 clinical trials. Existing full-text papers were reviewed after this selection. Unfinished clinical trials, those which were designed as strategies for national health systems and those which were not PFMT-specific were excluded, for example: “general fitness classes in pregnancy effect on postpartum period” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Studies selection flow.

Most of the clinical trials were studies of intervention group (for example: PFMT supervised by specialist, PFMT using various rehabilitation devices) versus control group (for example: PFMT at home, no PFMT) in pregnant and postpartum women, most of them were analyzed by intention-to-treat principle. Randomized clinical trials (RCT) were grouped by the symptoms they treated (Table 1). For assessing risk of bias, RoB 2 tool was used in RCTs. Most of the trials were unclear risk of selection bias because of insufficient information provided on random sequence generation and high to moderate overall risk, due to low numbers of participants, participants, and personnel blinding errors, and short follow-up terms.

Table 1.

Clinical trials characteristics.

3. PFMT and Sexual Life Quality

PFMT effect on women’s sexual life was analyzed in 7 RCTs. All the RCTs analyzed the postpartum period. Only 4 RCTs used questionnaires or scales to evaluate sexual function (SF): Marinoff Dyspareunia Scale, female sexual index (FSFI), sexual self-efficacy questionnaire, International consultation on incontinence (ICIQ) modular questionnaire—vaginal symptoms (ICIQ-VS), and ICIQ sexual matters module ICIQ-FLUTSsex. There was a tendency of improvement in SF postpartum by doing PFMT or PFMT combined with intravaginal transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), there was improvement in vaginal laxity, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and dyspareunia, no evidence of improvement found of using far-infrared radiation (FIR) device. There was an improvement in desire and pain symptoms in control group (no PFMT) within a 3-month period from the 4th to 7th month postpartum in one trial, but another trial showed improvement in pain symptoms with intensive PFMT, where both trials used FSFI questionnaires [17,18]. There were no major differences in vaginal symptoms between PFMT and control groups in one trial, but the PFMT group showed improvement in vaginal laxity symptoms, especially when there were levator ani muscle defects [17]. There is only low quality of evidence due to small sample sizes, short follow-up, randomization and blinding errors, and lack of standardized training reporting [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

4. PFMT and Pelvic-Floor Dysfunction

A mix of symptoms—POP, UI, and AI—were analyzed in 10 RCTs. Most of the RCTs trained women during the postpartum period. There were PFMT used together with rehabilitation devices such as: Direct Vagina Low Voltage Low Frequency Electric Stimulation (DES), transvaginal electrical stimulation (TVES), EMG-triggered neuromuscular stimulation, electrical stimulation (ES) with biofeedback treatment, sacral neuromodulation, bipolar vaginal radiofrequency device (VotivaTM, InMode), EmbaGYN, Magic Kegel Master devices. Other treatment procedures included injections of collagen. In addition, there was classical PFMT versus control group RCTs. ES with biofeedback and DES showed promising results in decreasing POP symptoms. In one trial, a group of patients, whose POP and UI symptoms improved the most, and started PFMT very early second day postpartum, regardless of whether they had episiotomy or second-degree perineum laceration, they received DES therapy 6 weeks postpartum [25]. TVES showed no evidence of improvement in PFD questionnaires or muscle strength, but there was a higher rate of correct PFM contraction in the group with weak PFM, which received TVES 5 times in 7 to 14 weeks postpartum [27]. Sacral neuromodulation showed improvement in AI, UI, and life-quality symptoms. Vaginal radiofrequency devices showed no evidence of improvement in POP, UI, or AI symptoms. EmbaGYN and Magic Kegel Master devices showed significant improvement in UI symptoms. Three PFMT versus control group RCTs showed no significant improvement in any of symptoms. One RCT with a high sample size and long follow-up showed promising results in UI symptoms, but the effect did not last for 12 months (Glazener C M 2001 and 2017). PFMT together with rehabilitation devices may improve PFD symptoms, but the results should be evaluated with care, due to small samples, selective reporting, and selection and performance biases.

One RCT analyzed PFMT effect in postnatal AI treatment. There was a significant difference in the reduction of St. Mark’s scores in favor of PFMT.

One RCT analyzed the PFMT effect on prevention of POP postpartum, but there was no significant improvement [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

5. PFMT and Obstetrical Injuries

Three RCTs analyzed various techniques to avoid obstetrical injury and/or episiotomy. Two RCTs analyzed antenatal use of Epi No device; neither found significantly lower incidence of anal sphincter, levator ani muscle injury or episiotomy in the Epi No group. One RCT compared antenatal perineal massage with PFMT to standard care. There was a significant reduction in episiotomy rates in the intervention group, also less third- to fourth-degree tears and less postpartum perineal pain. Two RCTs analyzed postpartum PFMT, one when there was an obstetrical anal sphincter injury (OASIS) and another when there was third-degree tears. None of them found statistically significant improvement after intervention [37,38,39,40,41].

6. PFMT and UI Prevention and Treatment

The highest number of RCTs—22—analyzed prepartum and/or postpartum PFMT effect on UI. To evaluate the effect of PFMT, six of them used specialized questionnaires: International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Overactive Bladder (ICIQ-OAB), Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI), Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ), International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-short form (ICIQ-UI SF), International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life Module (ICIQ-LUTSqol), and in most of them there was a statistically significant difference in favor of PFMT. Five used self-reported symptoms of UI. Two RCTs used Pad test to evaluate UI, one used bladder neck mobility. Most of the trials showed the positive effect of PFMT on UI, and PFMT group had less UI events in late pregnancy. One trial showed that written instructions of how to perform PFMT gives similar result as PFMT with specialist follow-up. Three trials showed the great effect of combined rehabilitation methods, e.g., PFMT with ES. Positive PFMT together with ES had long-lasting effect on UI; follow-up one year after intervention was conducted in one trial [42]. Preventative PFMT effect on UI was still present after 7 years in one trial [43]. One big sample (723 patients recruited, 234 included in trial) trial found that PFMT was non-effective in preventing future incontinence [44]. Only three RCTs followed up women after more than 6 months [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63].

7. Systematic Reviews about Antenatal and Postnatal PFMT

Systematic review characteristics are shown in Table 2. For assessing quality of evidence, the GRADE tool was used in systematic reviews. Many of the reviews were downgraded to low or very low quality of evidence, due to small samples of RCTs, low evidence quality of RCTs, high heterogeneity, and selective reporting biases. The main systematic review, which is continuous and is regularly updated and provides the highest level of evidence is Woodley et al. in Cochrane Systematic Review. The main conclusions from the reviews were that there is a lack of high-quality randomized and standardized studies. It is very hard to avoid randomization bias in PFMT-based interventions, due to difficulties of blinding. Despite clinical heterogeneity among the RCTs, PFMT shows promising results in reducing UI and improving quality of life, SF, and AI scores after pregnancy [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72].

Table 2.

Systematic reviews characteristics.

8. Discussion

Most of the studies agree with the use of PFMT in PFD prevention in prepartum and postpartum periods, although more high-quality studies are needed.

Good results are demonstrated by using biofeedback therapy, which allows patients to see and evaluate their progress. Studies which have used biofeedback training also had longer follow-up period from 6 months to 7 years [26,43,53].

Higher-quality studies are needed to investigate SF. Higher sample sizes, randomization of participants, and at least 3 to 12 months of follow-up is needed. No results of SF in prepartum period are known, although this period is hard to evaluate because of physical and psychological changes in women. PFMT improves muscle mass and tone, which is the opposite for looseness or laxity. PFMT helps to reach targeted results if patients experience symptoms such as “vagina feels loose or lax” [21]. If patients experience dyspareunia symptoms, additional effects could be reached by adding TENS to the PFMT program [22]. Some of the symptoms may improve within the time after delivery without PFMT, but PFMT groups in most of the trials reached improvement in greater variety of symptoms. Also, PFMT effectively improved SF when there were muscle defects, and intensive PFMT may help to reduce pain during intercourse and painful perineal scar formation [17,18].

Higher-quality evidence is needed about rehabilitation device (ES, TVES, FIR, sacral neuromodulation, radiofrequency, Kegel trainers) usage to treat prepartum and postpartum PFD. ES may be useful to relieve pain and muscle hypertonus; in this way it may improve dyspareunia symptoms. ES and TVES may be not that effective in improving muscle mass and tonus but it may help to teach patients with extremely weak perineal muscles how to perform a correct PFM contraction [20,27].

Kegel training devices may improve PFD symptoms and increase muscle tone; it is comfortable for patients, because they can use the devices at home, but there is a lack of strong scientific evidence. Usage of the device should be precisely documented, which is hard when patients are training at home all by themselves, therefore training time and number and strength of contractions and other parameters important for device effect evaluation may be poorly documented and not suitable to compare between study participants [33]. The Epi No device does not significantly reduce perineal trauma and episiotomy rates. Perineal massage and PFMT may give promising results in reducing perineal tears and episiotomy rates, but more high-quality studies with well documented technique and study protocols are needed to evaluate perineal muscle relaxation techniques’ additional effects in avoiding perineal trauma [37,38,39,40,41].

There are established results that antenatal PFMT helps to prevent UI in late pregnancy and reduce UI rates after delivery. Preventative PFMT effect is long-lasting. The best results are in continent women when they start structured PFMT at early pregnancy. The highest numbers of studies evaluate this symptom and here we have highest quality of evidence. Both antenatal and postnatal PFMT may improve quality of life, reduce urogenital distress and urinary symptoms after delivery [45,46,66,70]. Patients should get at least written instructions how to do PFMT. There is a big variety of questionnaires and methods used to evaluate UI symptoms in RCTs; less than a half of analyzed trials used certified questionnaires. Also, follow-up time after intervention was relatively short. Only a few trials followed patients longer than half a year. More standardized, high sample and longer follow-up studies are needed [66].

Too few trials analyzed PFMT effect on AI and POP prevention. More studies are needed in this field. Late pregnancy is associated not only with higher incidence of UI, but also AI and involuntary loss of flatus. External anal sphincter muscle might be trained the same way as other perineal muscles. Most studies evaluating PFD lack data about involuntary loss of flatus or stool during late pregnancy and postpartum and PFMT effect on this condition. POP reduction in RCT control groups shows that regeneration after delivery improves this condition even without PFMT in a short period (6 weeks to 1 year after delivery), but what is still unclear is whether there a difference between PFMT groups and control groups after a longer time [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,43]. Pelvic-floor rehabilitation including various rehabilitation methods and PFMT is recommended as a POP treatment, and there were more severe degrees of POP prevention method in middle-aged women with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic minor degree POP [73,74]. One of the reasons—that analyzed trials and reviews cannot provide strong evidence of the use of PFMT in POP prevention—might be that there is an increase in intensity of physical activity and weight-lifting in the postpartum period, due to returning to pre-pregnancy lifestyle and additionally baby-care routine which includes baby and baby-stroller lifting. These activities, if performed incorrectly, may increase severity of POP [36,75]. Other possible reason is follow-up period; if patients start training about 6 weeks postpartum and the last follow-up point is 6 months postpartum, the time interval is too short to evaluate the preventative effect of PFMT. There is also a lack of studies with PFMT and perineal rehabilitation timing; according to one trial, there might be a positive effect in POP prevention when PFMT is started very early—second day after delivery—regarding the episiotomy or perineal lacerations [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,74].

Proposals for research: there is high heterogeneity in RCTs. It is recommended to use more standardized measures—approved questionnaires to evaluate symptoms, use of validated terminology, for example joint IUGA-ICS terminology reports, PFMT reporting, for example use of a Consensus on Exercise reporting template, more attention to antenatal exercises effects, and longer follow-up [15,66]. Still, more evidence is needed about the best timing of PFMT in the postpartum period [25]. There are also some methods that were useful in treating middle-aged women with UI or POP symptoms; however, their effect on prepartum and postpartum women is unknown, for example extracorporeal magnetotherapy [76].

Proposals for practice: prepartum patient counseling about pelvic-floor anatomy and functions and how to prevent PFD during pregnancy and after labor is a necessary point of PFD prevention. Women should be encouraged to perform PFMT in prepartum and postpartum periods, because of the proven positive effect on UI prevention and treatment. National strategies for pregnancy and postpartum PFR programs orientated to PFD prevention should be a priority in national healthcare systems due to the high prevalence of POP and UI and the prediction for them to increase in general female population [2,11,16,66].

9. Study Limitations

This study had some limitations: limited number of databases used for literature search; article language was only English; short period of time for article selection; reporting bias due to selective reporting; and exclusion of incomplete articles.

This study did not receive any funding. The authors of the review declare no conflict of interests.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Swift, S.E. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 183, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.M.; Hundley, A.F.; Fulton, R.G.; Myers, E.R. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mant, J.; Painter, R.; Vessey, M. Epidemiology of genital prolapse: Observations from the Oxford Family Planning Association Study. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1997, 104, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, S.; Woodman, P.; O’Boyle, A.; Kahn, M.; Valley, M.; Bland, D.; Wang, W.; Schaffer, J. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): The distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 192, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinelli, A.; Malvasi, A.; Rahimi, S.; Negro, R.; Vergara, D.; Martignago, R.; Pellegrino, M.; Cavallotti, C. Age-related pelvic floor modifications and prolapse risk factors in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2010, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.; Hartmann, K.E.; Hellwege, J.N.; Velez Edwards, D.R.; Edwards, T.L. Obesity and pelvic organ prolapse: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 217, 11–26.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, E.L.; Rortveit, G.; Brown, J.S.; Creasman, J.M.; Thom, D.H.; Van Den Eeden, S.K.; Subak, L.L. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moalli, P.A.; Shand, S.H.; Zyczynski, H.M.; Gordy, S.C.; Meyn, L.A. Remodeling of vaginal connective tissue in patients with prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106 Pt 1, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mothes, A.R.; Radosa, M.P.; Altendorf-Hofmann, A.; Runnebaum, I.B. Risk index for pelvic organ prolapse based on established individual risk factors. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.; Falconer, C.; Cnattingius, S.; Granath, F. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery following hysterectomy on benign indications. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 572.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sze, E.H.; Sherard, G.B., 3rd; Dolezal, J.M. Pregnancy, labor, delivery, and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 100 Pt 1, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geelen, H.; Ostergard, D.; Sand, P. A review of the impact of pregnancy and childbirth on pelvic floor function as assessed by objective measurement techniques. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2018, 29, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haylen, B.T.; De Ridder, D.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Berghmans, B.; Lee, J.; Monga, A.; Petri, E.; Rizk, D.E.; Sand, P.K.; et al. An international urogynecological association (IUGA)/international continence society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2010, 29, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodley, S.J.; Boyle, R.; Cody, J.D.; Mørkved, S.; Hay-Smith, E.J.C. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 12, CD007471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P.; Andersson, K.-E.; Apostolidis, A.; Birder, L.; Bliss, D.; Brubaker, L.; Cardozo, L.; Castro, D.; O’Connell, P.R.; Cottenden, A.; et al. 6th International Consultation on Incontinence. Recommendations of the International scientific Committee: Evaluation and treatment of Urinary Incontinence, Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Faecal Incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 2271–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICS. ICS Standards; Blurb, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 351–416. [Google Scholar]

- Citak, N.; Cam, C.; Arslan, H.; Karateke, A.; Tug, N.; Ayaz, R.; Celik, C. Postpartum sexual function of women and the effects of early pelvic floor muscle exercises. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2010, 89, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iervolino, S.A.; Pezzella, M.; Passaretta, A.; Torella, M.; Colacurci, N. Postpartum female sexual dysfunction: Effects of two different degrees of pelvic floor muscle exercises. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017, 36, S37–S38. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, S.C.; Dionne, C.E.; Underwood, M.; Buchbinder, R. Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT): Explanation and Elaboration Statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-H.; Lai, Y.-F.; Chen, G.D.; Lee, M.-S.; Ng, S.-C. Effect of far-infrared radiation on perineal wound pain and sexual function in primiparous women undergoing an episiotomy. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennfjord, M.K.; Hilde, G.; Staer-Jensen, J.; Siafarikas, F.; Engh, M.E.; Bø, K.; Stær-Jensen, J. Effect of postpartum pelvic floor muscle training on vaginal symptoms and sexual dysfunction-secondary analysis of a randomised trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 123, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionisi, B.; Senatori, R. Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on the postpartum dyspareunia treatment. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2011, 37, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmakani, N.; Zare, Z.; Khadem, N.; Shareh, H.; Shakeri, M.T. The effect of pelvic floor muscle exercises program on sexual self-efficacy in primiparous women after delivery. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zare, Z.; Golmakani, N.; Khadem, N.; Shareh, H.; Shakeri, M.T. The effect of pelvic floor muscle exercises on sexual quality of life and marital satisfaction in primiparous women after childbirth. Iran. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Infertil. 2014, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Sang, W.; Feng, J.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Fan, H.; Tang, Z.; Gao, L. The effect of rehabilitation exercises combined with direct vagina low voltage low frequency electric stimulation on pelvic nerve electrophysiology and tissue function in primiparous women: A randomised controlled trial. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4537–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Zhu, L.; Lang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Chen, X.; Feng, S.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Postpartum pelvic floor rehabilitation on prevention of female pelvic floor dysfunction: A multicenter prospective randomized controlled study. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2015, 50, 420–427. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, F.; Xie, Z. Effect of different electrical stimulation protocols for pelvic floor rehabilitation of postpartum women with extremely weak muscle strength. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e19863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazener, C.M.A.; MacArthur, C.; Hagen, S.; Elders, A.; Lancashire, R.; Herbison, G.P.; Wilson, P.D. Wilson Twelve-year follow-up of conservative management of postnatal urinary and faecal incontinence and prolapse outcomes: Randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2014, 121, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekskulchai, O.; Wanichsetakul, P. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) during pregnancy on bladder neck descend and delivery. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2014, 97 (Suppl. 8), S156–S163. [Google Scholar]

- Stafne, S.N.; Salvesen, K.Å.; Romundstad, P.R.; Torjusen, I.H.; Mørkved, S. Does regular exercise including pelvic floor muscle training prevent urinary and anal incontinence during pregnancy? A randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2012, 119, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydningen, M.; Dehli, T.; Wilsgaard, T.; Rydning, A.; Kumle, M.; Lindsetmo, R.O.; Norderval, S. Sacral neuromodulation compared with injection of bulking agents for faecal incontinence following obstetric anal sphincter injury-a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal. Dis. 2017, 19, O134–O144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, J.; Dayan, E.; Theodorou, S.; Westfall, L.; Ramirez, H. 090 Effects of Bipolar Radiofrequency Treatment on Subjective and Objective Endpoints in Post-Partum Pelvic Floor Disorders. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artymuk, N.V.; Khapacheva, S.Y. Device-assisted pelvic floor muscle postpartum exercise programme for the management of pelvic floor dysfunction after delivery. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazener, M.; Herbison, G.P.; Wilson, P.D.; MacArthur, C.; Lang, G.D.; Gee, H.; Grant, A.M. Conservative management of persistent postnatal urinary and faecal incontinence: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2001, 15, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, H.H.; Wibe, A.; Stordahl, A.; Sandvik, L.; Mørkved, S. Do pelvic floor muscle exercises reduce postpartum anal incontinence? A randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2017, 124, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bø, K.; Hilde, G.; Stær-Jensen, J.; Siafarikas, F.; Tennfjord, M.K.; Engh, M.E. Postpartum pelvic floor muscle training and pelvic organ prolapse—a randomized trial of primiparous women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 38.e1–38.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, K.L.; Chantarasorn, V.; Langer, S.; Phipps, H.; Dietz, H.P. Does the Epi-No® Birth Trainer reduce levator trauma? A randomised controlled trial. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2011, 22, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Larios, F.; Corrales-Gutierrez, I.; Casado-Mejía, R.; Suarez-Serrano, C. Influence of a pelvic floor training programme to prevent perineal trauma: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Midwifery 2017, 50, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.; Murphy, C.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Cassidy, M.; Daly, L.; O’Connell, P.R.; O’Herlihy, C. Randomised controlled trial comparing early home biofeedback physiotherapy with pelvic floor exercises for the treatment of third-degree tears (EBAPT Trial). BJOG 2013, 120, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, H.P.; Langer, S.; Kamisan Atan, I.; Shek, K.L.; Caudwel-Hall, J.; Guzman Rojas, R. Does the EPI-NO prevent pelvic floor trauma? A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2014, 33, 853–855. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, S.H.; Ghodsi, V.C.; Crisp, C.C.; Estanol, M.V.; Westermann, L.B.; Novicki, K.M.; Kleeman, S.D.; Pauls, R.N. Impact of Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy on Quality of Life and Function After Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 22, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, C.; Seaborne, D.E.; Quirion-DeGirardi, C.; Sullivan, S.J. Pelvic-floor rehabilitation, Part 2: Pelvic-floor reeducation with interferential currents and exercise in the treatment of genuine stress incontinence in postpartum women--a cohort study. Phys. Ther. 1995, 75, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dumoulin, C.; Martin, C.; Elliott, V.; Bourbonnais, D.; Morin, M.; Lemieux, M.-C.; Gauthier, R. Randomized controlled trial of physiotherapy for postpartum stress incontinence: 7-year follow-up. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2013, 32, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewings, P.; Spencer, S.; Marsh, H.; O’Sullivan, M. Obstetric risk factors for urinary incontinence and preventative pelvic floor exercises: Cohort study and nested randomized controlled trial. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2005, 25, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sut, H.K.; Kaplan, P.B. Effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise on pelvic floor muscle activity and voiding functions during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2016, 35, 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Mørkved, S.; Bø, K.; Schei, B.; Salvesen, K.A. Pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy to prevent urinary incontinence: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 101, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åhlund, S.; Nordgren, B.; Wilander, E.-L.; Wiklund, I.; Fridén, C. Is home-based pelvic floor muscle training effective in treatment of urinary incontinence after birth in primiparous women? A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013, 92, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocaöz, S.; Eroğlu, K.; Sivaslioglu, A.A. Role of Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises in the Prevention of Stress Urinary Incontinence during Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2013, 75, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumilewicz, A.; Kuchta, A.; Kranich, M.; Dornowski, M.; Jastrzębski, Z. Prenatal high-low impact exercise program supported by pelvic floor muscle education and training decreases the life impact of postnatal urinary incontinence: A quasiexperimental trial. Medicine 2020, 99, e18874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, E.T.C.; Freeman, R.M.; Waterfield, M.R.; Waterfield, A.E.; Steggles, P.; Pedlar, F. Prevention of postpartum stress incontinence in primigravidae with increased bladder neck mobility: A randomised controlled trial of antenatal pelvic floor exercises. BJOG 2014, 121 (Suppl. 7), 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangsawang, B.; Sangsawang, N. Is a 6-week supervised pelvic floor muscle exercise program effective in preventing stress urinary incontinence in late pregnancy in primigravid women?: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 197, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinc, A.; Beji, N.K.; Yalcin, O. Effect of pelvic floor muscle exercises in the treatment of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.S.; Choi, E.S. Pelvic floor muscle exercise by biofeedback and electrical stimulation to reinforce the pelvic floor muscle after normal delivery. Taehan Kanho Hakhoe Chi. 2006, 36, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.; Botelho, S.; Pereira, L.C.; Lanza, A.H.; Amorim, C.F.; Palma, P.; Riccetto, C. Pelvic floor muscle training program increases muscular contractility during first pregnancy and postpartum: Electromyographic study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2012, 32, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsawang, B.; Serisathien, Y. Effect of pelvic floor muscle exercise programme on stress urinary incontinence among pregnant women. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 68, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldringh, C.; Wijngaart, M.V.D.; Albers-Heitner, P.; Nijeholt, A.A.B.L.À.; Lagro-Janssen, T. Pelvic floor muscle training is not effective in women with UI in pregnancy: A randomised controlled trial. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2006, 18, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumoulin, C.; Lemieux, M.-C.; Bourbonnais, D.; Gravel, D.; Bravo, G.; Morin, M. Physiotherapy for Persistent Postnatal Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 104, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morkved, S.; Bo, K. Effect of postpartum pelvic floor muscle training in prevention and treatment of urinary incontinence: A one-year follow up. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 107, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaez, M.; Gonzalez-Cerron, S.; Montejo, R.; Barakat, R. Pelvic floor muscle training included in a pregnancy exercise program is effective in primary prevention of urinary incontinence: A randomized controlled trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2013, 33, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.D.; Herbison, G.P. A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle exercises to treat postnatal urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. 1998, 9, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Assis, L.C.; Barbosa, A.M.P.; Santini, A.C.M.; Bernardes, J.M.; Vianna, L.S.; Dias, A. Effectiveness of an illustrated home exercise guide on promoting urinary continence during pregnancy: A pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Rev. Bras. Gynecol. Obstet. 2015, 37, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampselle, C.M.; Miller, J.M.; Mims, B.L.; Delancey, J.O.; Ashton-Miller, J.A.; Antonakos, C.L. Effect of pelvic muscle exercise on transient incontinence during pregnancy and after birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 91, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptak, M.; Ciećwież, S.; Brodowska, A.; Starczewski, A.; Nawrocka-Rutkowska, J.; Diaz-Mohedo, E.; Rotter, I. The Effect of Pelvic Floor Muscles Exercise on Quality of Life in Women with Stress Urinary Incontinence and Its Relationship with Vaginal Deliveries: A Randomized Trial. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, L.; Crivelatti, I.; De Oliveira, J.M.; Nygaard, C.C.; Dos Santos, T.G. Systematic review of pelvic floor interventions during pregnancy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemos, A.; de Souza, A.I.; Ferreira, A.L.C.G.; Figueiroa, J.N.; Cabral-Filho, J.E. Do perineal exercises during pregnancy prevent the development of urinary incontinence? A systematic review. Int. J. Urol. 2008, 15, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodley, S.J.; Lawrenson, P.; Boyle, R.; Cody, J.D.; Mørkved, S.; Kernohan, A.; Hay-Smith, E.J.C. Pelvic floor muscle training for preventing and treating urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD007471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagg, A.; Bunn, F. Unassisted pelvic floor exercises for postnatal women: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 58, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhgol, S.S.; Priddis, H.; Smith, C.A.; Dahlen, H.G. The Effect of Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercise on Female Sexual Function During Pregnancy and Postpartum: A Systematic Review. Sex. Med. Rev. 2019, 7, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadizadeh-Talasaz, Z.; Sadeghi, R.; Khadivzadeh, T. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training on postpartum sexual function and quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mørkved, S.; Bø, K. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy and after childbirth on prevention and treatment of urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 48, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; McInnes, N.; Leong, Y. Pelvic Floor Muscle Training Versus Watchful Waiting and Pelvic Floor Disorders in Postpartum Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 24, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driusso, P.; Beleza, A.C.S.; Mira, D.M.; Sato, T.D.O.; Cavalli, R.D.C.; Ferreira, C.H.J.; Moreira, R.D.F.C. Are there differences in short-term pelvic floor muscle function after cesarean section or vaginal delivery in primiparous women? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braekken, I.H.; Majida, M.; Engh, M.E.; Bø, K. Can pelvic floor muscle training reverse pelvic organ prolapse and reduce prolapse symptoms? An assessor-blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 203, 170.e1–170.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bent, A.E.; Ostergard, D.; Cundiff, G.; Swift, S. (Eds.) Ostergard’s Urogynecology and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, 5th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadephia, PA, USA, 2002; 587p, ISBN 0-7817-3384-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.; Hitchcock, R.; Niederauer, S.; Nygaard, I.E.; Shaw, J.M.; Sheng, X. Variables Affecting Intra-abdominal Pressure During Lifting in the Early Postpartum Period. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 24, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber-Rajek, M.; Strączyńska, A.; Strojek, K.; Piekorz, Z.; Pilarska, B.; Podhorecka, M.; Sobieralska-Michalak, K.; Goch, A.; Radzimińska, A. Assessment of the Effectiveness of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT) and Extracorporeal Magnetic Innervation (ExMI) in Treatment of Stress Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).