Abstract

The upgraded knowledge of tumor biology and microenviroment provides information on differences in neoplastic and normal cells. Thus, the need to target these differences led to the development of novel molecules (targeted therapy) active against the neoplastic cells’ inner workings. There are several types of targeted agents, including Small Molecules Inhibitors (SMIs), monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), interfering RNA (iRNA) molecules and microRNA. In the clinical practice, these new medicines generate a multilayered step in pharmacokinetics (PK), which encompasses a broad individual PK variability, and unpredictable outcomes according to the pharmacogenetics (PG) profile of the patient (e.g., cytochrome P450 enzyme), and to patient characteristics such as adherence to treatment and environmental factors. This review focuses on the use of targeted agents in-human phase I/II/III clinical trials in cancer-hematology. Thus, it outlines the up-to-date anticancer drugs suitable for targeted therapies and the most recent finding in pharmacogenomics related to drug response. Besides, a summary assessment of the genotyping costs has been discussed. Targeted therapy seems to be an effective and less toxic therapeutic approach in onco-hematology. The identification of individual PG profile should be a new resource for oncologists to make treatment decisions for the patients to minimize the toxicity and or inefficacy of therapy. This could allow the clinicians to evaluate benefits and restrictions, regarding costs and applicability, of the most suitable pharmacological approach for performing a tailor-made therapy.

1. Introduction

Targeted therapies are developed to encompass the nonspecific toxicity associated to standard chemo-drugs and also to ameliorate the efficacy of treatment. Biological agents can be used alone, but very often a combination of targeted molecules and conventional anti-tumor drugs is used. This new strategy aims to a selectively killing of malignancy cells by targeting either the expression of specific molecules on cancer cell surface or the different activated molecular pathways that directed to tumor transformation [1]. New therapeutic approaches include a combination of “old” anticancer drugs (i.e., chemotherapies) and innovative molecules (targeted agents). These procedures are planned to mark both primary and metastatic cancer cells. The current classification of cancer-hematology targeted drugs includes monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), small-molecule inhibitors (SMIs), interfering RNA (iRNA), microRNA, and oncolytic viruses (OV). Their mechanisms of action can be either tumor specific (by interfering with cancer cell membrane biomarkers, cell-signaling pathways, and DNA or epigenetic targets), or systemic, through triggering of the immune responses [2,3,4].

Currently, scientific evidence is still low, to address therapeutic drug monitoring of mAbs and SMIs. In this scenario, their combination with adjuvant therapies may represent a promising cancer treatment approach [5].

In 2001, the first selective ABL Tyrosin Kinase inhibitor (TKI, Imatinib) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [6]. This was quickly followed by the monoclonal antibody marking the CD20 antigen (anti-CD20mAb, Rituximab) [7]. Both agents accounted the revolution in the management of patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), respectively. These drugs guarantee around 80% response rate; on the other hand, drug-resistance is still a limitation, and new generation TKIs are being developed to by-pass these matters.

Currently, various new molecules are developed against specific tumor cell targets. Among these, histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) and DNA hypomethylating agents target genetic/epigenetic determinants central for tumor growth ablation. New peptide vaccines targeting novel tumor-associated antigens, alternative checkpoint inhibitors, and chimeric antigen against T receptor (CAR-T) of the lymphocytes are being developed for the patients who have failed classical immunotherapy (often anti-PD1/anti-PD-L1). Newer SMIs targeting a variety of oncogenic signaling are being advanced to overcome the emerging of resistance phenomena to the existing targeted drug procedures [8]. Above Table 1 reviews currently open phase I/II/III clinical trials for onco-hematologic patients. The data in the table were collected from clinicaltrils.gov (accessed on June 2019). It may provide a useful implement to oncologist who treat relapsed refractory hematology malignancy.

Table 1.

The most common agents suitable for onco-hematology targeted therapy.

Thanks to unique mechanisms of action these drugs are part of the therapy for many anticancer protocols, including lung, breast, pancreatic, and colorectal tumors, as well as lymphomas, leukemia, and multiple myelomas (MM). Also, targeted therapies call for new approaches to evaluating treatment effectiveness, and to assess the patients’ adherence to treatment [9].

Although targeted drugs, primarily the mAbs administration, are better tolerated than conventional chemotherapy, they are recorded numerous adverse events, such as cardiac dysfunction, hypertension, acneiform rash, thrombosis, and proteinuria [10]. Since, SMIs are metabolized preferentially by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP450), the pharmacokinetics variation and multiple drug interactions should be present [11].

Finally, targeted therapy has raised new questions about the tailoring of cancer treatments to each patient’s tumor profile, the estimation of drug response, and the public reimbursement of cancer care. In agreement with these and other criticisms, the intention of this review is to provide information about the overall biology and mechanism of action of target drugs for onco-hematology, including overall pharmacodynamics due toxicities, and eventually inefficacy of the therapy [12]. The well-noted correlation between the individual genomics profile and overall pharmacokinetic are reported below. In addition, the economic impact of these drugs, which can exceed several-fold the cost of traditional approaches, may become a major issue in pharmacoeconomics; an early evaluation of outcomes and challenges are also reported in this issue.

2. The Biological Mechanism of Action of the Targeting Agents

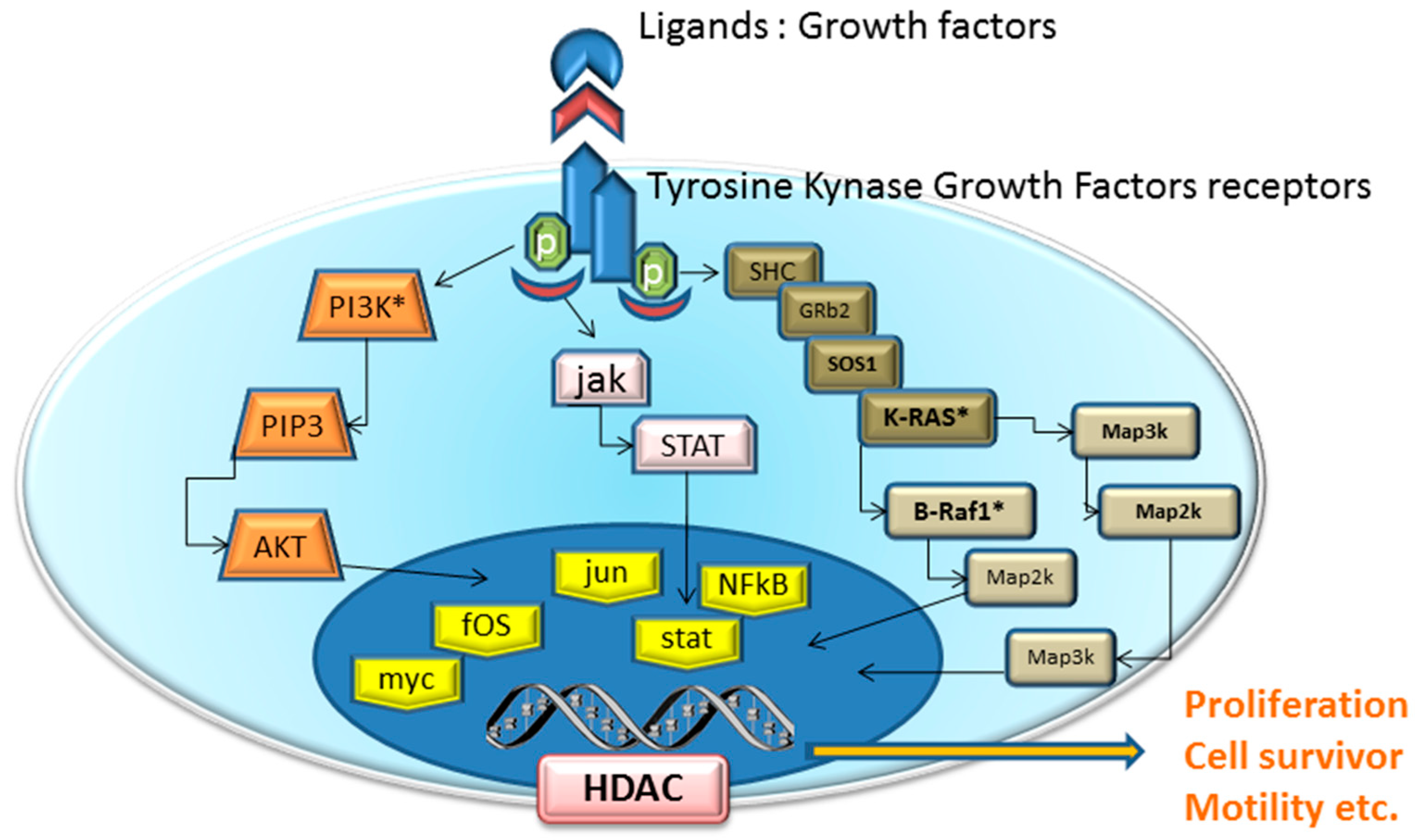

Traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy works mainly through the inhibition of cell division like as cytoskeleton inhibitors (i.e., tecans, vincristine)analogues of nucletides (i.e., 5-Fluorouracil, Gemcitabine). So, each normal cell in mitotic stage (e.g., hair, gastrointestinal epithelium, bone marrow) is affected by these drugs. In contrast, the mechanism of action of targeted agents block specifically the proliferation of neoplastic cells by interfering with specific pathways essential for tumor progression and growth (Figure 1). It is true that some of these molecular targets could be present also in normal tissues, but they are often abnormally expressed in cancer tissues because of genic alterations.

Figure 1.

Schematic of pathway inhibition by targeted agents and their effects on cell proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis and angiogenesis. Receptors for growth factors (VEGFR, FGFR, PDGFR) activate intracellular receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and the downstream RAS/RAF/mitogen-activated protein extracellular kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling pathway, and promote the growth, migration, and morphogenesis of vascular endothelial cells, thus increasing vascular permeability.

2.1. Monoclonal Antibodies

In the last decade, about 30 mAbs have been approved, almost the 50% of them for the hematology-cancer therapy. The backbone of a mAb includes the fragment antigen binding (Fab), which recognizes and engage antigens, thus targeting the specific counterpart on cancer cells which is the objective of such therapies [13]. These antibodies agent, either as native molecules or conjugated to radioisotopes or toxins (viral molecules to interfere with cell vitality) exert their antineoplastic effects through different mechanisms: by engaging and arming host immune effectors (i.e., natural killer cells and the complement) against target cells; by binding to receptors or ligands, thereby interfering with essential cancer cell proliferation pathways; or by carrying a “lethal cargo”, such as a radioisotope or toxin, to the target cell [14,15]. Because they are protein in structure, mAbs denatured in the gastrointestinal tract, and for this reason, they are administered intravenously. In this way, they do not undergo hepatic metabolism thus escaping significant drug interactions via CYP450 pathway.

Latest 30 years, as biotechnology has evolved, the design of mAbs has changed. Immunized mice developed early molecules in this class against target antigens. The resulting mAbs comprised the entire murine immunoglobulins (Igs), which were, hypothetically, carrying a risk of antigenic reaction during parenteral administration. The primary adverse events for patients treated with these new drugs is forming anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies, which could counteract the effect of the therapeutic mAbs. To decrease these adverse reactions, was developed mAbs contain an enlarged proportion of human Ig components to reducing murine Ig components. So mAbs are defines as: chimeric antibodies (about 65% human), humanized antibodies (95% human), and human antibodies (100% human) [16].

General precautions of mAbs include: (a) Co-administrations of vaccines may be avoided; (b) Herpes and Pneumocystis prophylaxis recommended in therapy influencing the immune surveillance system (i.e., Anti-CD52);

The mAbs were designed to affect several cellular pathways. An angiogenic inhibitor (i.e., Anti-VEGF) was currently investigated in NHL, MM, and myeloproliferative disorders [17]. The major side effect regardless the risk of ischemic events.

Immunomodulators aimed to achieve blocking of inhibitory molecules on the cell surface of immune effectors (i.e., Anti PD-1, anti-CD30, anti CD52, anti-CTLA-4, and anti-CD80), were approved for the treatment of patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL).

The first targeted therapies have developed through the study of the over/expression of markers on the surface of tumor cells (on lymphoma and leukemia cells) including the cluster of differentiation 20, 33, and 52 (CD20, CD33, and CD52). Targeting this molecule affects the overall humoral immune response, as CD20 is also expressed on normal lymphocyte B. This estimation has led to the administration the anti-CD20 mAb Rituximab for the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [18], and NHL [19].

Moreover, mAbs might induce tumor cell death through direct and indirect mechanisms, all prominent in blocking several and different oncogenic pathways. mAbs are effective at multiple levels: surface molecules (neutralizing ligand-specific receptor interaction), receptors (competitive with a ligand for binding); receptor signaling (signal blocking), or intracellular molecules. Therapeutic mAbs, which are typically water soluble and large molecular weight (about 160 kDa), target extracellular molecule-inducing signals, such as receptor-binding sites and ligands.

Noteworthy, Brentuximab vedotin have a new peculiar mechanism of action. It is an anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate (mAbC) that delivers an anti-tubulin toxin that induces apoptotic cell death in CD30-expressing tumor cells. Brentuximab vedotin is a mAb with a regular action involving a multi-step progression: binding to CD30 on the cell surface recruits internalization of the mAbC-CD30 complex, which then transfers to the cytoskeleton structures, where the released toxin, the monoauristatin-E, rescinds the microtubule complex, inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptotic death of the CD30-expressing cell in replication stage. However, classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and T-anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) express CD30 as an antigen on the surface of their malignant cells [20].

2.2. Small Molecule Inhibitors

SMIs are chemical agents with low molecular weight (inferior to 1 kDa) capable of entering into the targeted cells, thus blocking signaling pathway and interfering with downstream intracellular protein systems (i.e., TK signaling). These molecules consist of TKI, BKI, Aurora Kinase Inhibitors (AKI), proteosome Inhibitors and HDAC inhibitors. Tyrosine Kinases phosphorylate specific amino acid residues of intracellular substrates affecting angiogenesis and cell growth in normal and malignant tissues.

The SMls differ from mAbs in many ways: (i) they are usually orally administered rather than parenterally infused; (ii) they are generated via a step-by-step chemical practice, a method that is often much less expensive than the bioengineering (i.e., recombinant DNA techniques) required for mAbs generation [18]; (iii) they reach fewer definite targeting than mAbs, as marked in the multitargeting nature of the kinase inhibitors [21].

In contrast to mAbs, most of the SMIs are metabolized by the CYP450 enzymes family, which may consequence in drug-drug interactions with molecules such as warfarin, azole antimicotics, viral anti-protease, and the St. John’s wort, known as unyielding CYP450-inhibitors [22].

The mAbs have administered once every one-to-four weeks due to pharmacokinetic of T1/2 ranging from few days to few weeks. While most SMIs have half-lives of few hours and necessitate daily dosing., with the exception of few molecules (i.e., bortezomib) which is given intravenously, SMIs are administered per os (orally).

2.2.1. Kinase-Based Signaling Inhibitors

Agents developed for blocking the signaling pathway includes: Tyrosin Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs), Bruton Kinase Inhibitors (BTKIs), Aurora Kinase Inhibitors (AKI) and SYK, PI3K Inhibitors.

Imatinib is the first FDA-approved SMIs (since 2002) for the treatment of CML. It inhibits a constitutive TK activities resulting from the translocation of chromosomes 9 and 22 (the Philadelphia chromosome), involving BCR and Abl genes. Because this molecular anomaly occurs in essentially all patients with CML, imatinib therapy results in a complete hematologic response in 98% of them [23]. Novel TKI molecules to overcome the imatinib resistance due to ABL T315I was developed, Bosutinib [24], Dasatinib [25], Nilotinib [26], and Ponatinib [27]. Furthermore, these small molecules are not able to prevent cerebral metastasis [28].

Other altered TK pathway, involved in myeloid and lymphoproliferative disorders are the Janus Kinase receptors (JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), MET mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), RET, and RAF.

JAK family (JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3) members mediate cytokine signaling via downstream activation of the STAT family of transcriptional regulators. Activated STATs endorse multiple cellular actions, like differentiation, proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. In particular, JAK2 is mediated hematopoiesis via GM-CSF, leptin, IL3, erythropoietin, and thrombopoietin [29]. Activation of JAKs are induced conformational changes of ligand-binding to cytokine receptors, which engage phosphotyrosine-binding domains and/or SRC homology-2, which leads to activation of STAT, Ras–MAPK, and PI3K–AKT signaling pathways. Mutations in JAK2 exon 12 in pseudokinase domain (JH2) and JAK2 Val617Phe in exon 14 have been identified in approximately 4% and 90% of PV cases respectively. Several agents to interfere with JAK/STAT pathway were deigned: Itacitinib is a selective JAK1 inhibitor [30]; Momelotinib and Ruxolitinib are both JAK1-2 inhibitor [31,32].

MET, is a receptor tyrosine kinase that, after binding with hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), activates the PI3K and MAPK pathways. Over-expression of MET gene and exon-14-skipping mutations are characteristic abnormalities causing increased MET signaling progression. Cabozantinib is unique MET Inhibitor studied in phase 1b study in patients with relapsed MM [33].

The PI3K pathway is an essential mediator of cell survival signals. Several molecules PI3K-p110 α,γ,δ sub unit inhibitor were under trial phase 1–2 for NHL, like as AMG319 [34], Buparlisib [35,36], Copanlisib [37], CUDC-907 with additional inhibition of HDAC [38], Dactolisib with additional inhibition on mTOR-p70S6K [39], Duvelisib [40], Getadolisib is a pan-PI3K, mTOR inhibitor. Its safety and maximum tolerated dose have been recently established in a phase 2 study of AML and CML [41]. Idelalisib currently approved use for CLL [42,43], INCB040093 [44], Pictilisib [45], and Taselisib the ultra-selective isoform-sparring PI3K-p110 α,γ,δ [46], TGR-1202 [47] also tested in combination with brentuximab in HL [48] and Voxtalisib [49].

The RET proto-oncogene encodes a receptor TK for members of the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family. Vandetanib [50], sorafenib [51,52], sunitinib [53], and cabozantinib are multi-targeted TKIs with RET-blocking activity. They are currently tested in phase 2 trials for MM and ALL [54].

BRAF is a downstream signaling mediator of KRAS, which activates the MAP kinase pathway. BRAF mutations are found in about 99% of cases of hairy cell leukemia [55] and in several cases of MM. To date, Dabrafenib and Vemurafenib are FDA-approved for BRAF V600E-positive malignant melanomas, but clinical trials of phase 1–2 were currently performed [55].

2.2.2. Bruton’s Tyrosin Kinase Inhibitor

BTK is a cytoplasmic TK essential for B-lymphocyte development, differentiation, and signaling. As known, humans X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) caused by mutations in the BTK gene (usually D43R and E41K). Activation of BTK triggers step by step signaling events that culminates in the cytoskeletal rearrangements by Ca2+ recruitments and transcriptional regulation involving nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). In B lymphocytes, NF-κB bind the BTK 5′UTR gene promoter and active gene transcription, whereas the B-cell receptor-dependent NF-κB signaling pathway requires functional BTK [56,57].

Based on these issues several molecules were developed to target BTK: Ibrutinib [58], and idelalisib [42].

2.2.3. Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors

Gene expression is regulated primarily by histone acetylation and deacetylation mechanism; this process is essential for relaxing the condensed chromatin and exposes the promoter regions of genes to transcription factors. On the contrary, deacetylation catalyzed by histone deacetylases (HDACs) results in gene silencing [59]. In leukemic cells, this equilibrium is disturbed, and therefore, HDAC inhibitors emerged as a striking therapeutic approach to revise therapy. Unlike, clinical activity of monotherapy with an HDAC inhibitor was low, with ORR of 17% for vorinostat and 13% for mocetinostat [60], and no clinical response was achieved with entinostat monotherapy [61]. In addition, Belinostat has been tested in elderly patients with relapsed AML [62]. Since it is primarily metabolized by UGT1A1; the initial dose should be reduced if the beneficiary is acknowledged to be homozygous for the UGT1A1*28 allele [63]. Therefore, current studies focus on combination regimens of HDAC inhibitors with other epigenetic agents are still ongoing.

2.2.4. Proteosome Inhibitors

The proteasome is the latest promising molecular target for cancer therapy, a large multimeric [64]. The proteasome is a protein complex that degrades the damaged proteins, and neoplastic cells are highly needy on increased protein production and degradation. It has a crucial role in cell signaling, cell survival, and cell-cycle progression. For these issues, proteasome inhibition is a core of therapy in lymphoid malignancies. Furthermore, proteasome inhibitors, such as bortezomib [65] and carfilzomib [66], are currently integrated into major regimens for multiple myeloma (MM) and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients. Recently, proteasome inhibitors have also been used for the treatment of the relapsed/refractory setting for other NHLs, such as follicular cell lymphoma (FCL) [67,68].

3. Pharmacogenetics, Overall Pharmacokinetics

Genetic tests for targeted cancer therapy detect either acquired mutations in the DNA of cancer cells and or polymorphisms in all germinal cells. Genotyping the cancer cells can help guide the type of targeted treatment, and it can predict who may respond to planned therapy and who is not likely to have benefited.

Researchers have extensively studied these variants in genes in order to better understand cancer and to develop drugs to interfere with a specific step in cancer growth while doing minimal damage to normal cells. The first example was Dasatinib and Nilotinib designed to by-pass the acquired mutation T315I in Abl gene in LMC patients. Unluckily, not every cancer has these acquired mutations, and various hematologic-cancers cells without this genetic signature cannot benefit to personalized treatments.

Pharmacogenomic tests are important, also, for the pharmacoeconomic issue: targeted drugs are expensive, and they generally work efficacy only in cancer patients who carried a genetic marker. Genetic testing prior to beginning therapy is necessary to match the treatment up with the patients and cancers likely to benefit from them. In contrast, chemotherapic drugs are cheaper, but it based on the paradigm of the “trial and error” leading the hospitalization during treatments. Recently, to reduce pharmaceutical expenditure, a combination of 2 SMIs blocking 2 mutated genes (BRAF and MET) are performed in the unique formulation (encorafenib + binimatenib) for melanoma therapy. So, the route is also drawn for the onco-hematology [137].

The most common targeted cancer drugs for which tests are available include:

Drugs that block growth signaling binding to receptors on the cell surface

Small molecules inhibitors are able to cross the cell membrane and block downstream the growing signals in the specific active site.

These pharmacogenetic tests are used to help adjust drug dosage for certain cancers. They help to inform the oncologist as to whether certain targeted cancer drugs may or may not work.

4. Outcomes and Challenges

Generally, chemotherapy is administered intravenously in an ensured infusion area. Therefore, patient adherence to treatment regimens is gladly reviewed. Delays and omissions in chemotherapy dosages, whether they are the result of patient preference or treatment-related either toxicities or resistance, are immediately recognized and documented. In contrast, most SMIs (almost all are oral formulation) administered at home on a long-term daily scheduling, could be difficult to recognize adverse events in real time. Thus, the task of assessing patient adherence more closely resembles that encountered with therapies for chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypercholesterolemia, and in so-called “frail patients”. Finally, a few studies published to date shown high variability and unpredictability about patient adherence to oral cancer treatment regimens [138].

Targeted therapy offers new means to determine the best possible treatment. Moreover, estimation of treatment success could not be based on the reduction in neoplastic volume and/or evaluation of toxicity through the degree of myelosuppression severity as well as traditional chemotherapy. Targeted therapies could convey a clinical benefit by stabilizing tumors, rather than reducing the progression of the neoplastic population cells. It also must necessitate to a paradigm shift in the evaluating the effectiveness of therapy. To set up the optimum of targeted drugs in terms of dosing and efficacy, must be evaluated progressively several endpoints, such as tumor metabolic activity on positron emission tomography (PET) scans, levels of circulating neoplastic cells, and following levels of target molecules in tumor tissue [139]. These actions introduce complexity and cost to medical activity. Also, repeated biopsies of tumor tissue may be untimely for patients and improper to institutional evaluation boards.

Even though these procedures introduces new economic considerations: (i) oral SMIs eliminate treatment costs associated with the hospitalized intravenous infusions; (ii) the biotechnical production of mAbs can improves costs exponentially; (iii) need to genotype or phenotype tumor tissue; and (iv) new competencies for oncologist about pharmacogenomic testing [140].

In term of the expenses, the targeted therapy is widely most expensive than traditional approaches. For example, in colon cancer, multidrug treatment regimens containing bevacizumab or cetuximab increase the cost to about 500-fold ($30,790 for 8 weeks of treatment), compared with fluorouracil/leucovorin-based regimen ($63 for the same period) [141].

Based on this consideration, clinicians and laboratorists have a duty to cooperate in evaluating the advantages and limitations, particularly regarding costs and applicability, of the pharmacogenomic tests most appropriate for routine incorporation in clinical practice [142].

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

For decades, the hallmark of anticancer treatments has based on the cytotoxic chemotherapy. These molecules rapidly target mitotic cells, including, unluckily, not only cancer cells but also, normal tissues in physiological growing phase. As a result, many patients develop the general adverse drug reaction (ADR) toxicities such as gastrointestinal symptoms, myelosuppression, and alopecia.

The medical approach based on chemotherapy alone, or in combination with surgical, and/or radiation, has reached doubtful therapeutic advances in spite of many significant enhancements in such treatments. While chemotherapy rests the primarily support of the current treatment in onco-hematology, it is limited by a narrow therapeutic index, noteworthy toxicity leading to treatment discontinuations and frequently acquired resistance.

The targeted molecules are drugs manufactured to interfere with specific proteins necessary for tumor growth and progression.

The new oncologic challenges of the 3rd millennium are based on the developments of the targeted therapy, including OV, interfering RNA molecules, and microRNA [143].

The OV is capable of selectively replicating in tumor cells, leading to their lysis. There is growing proof, in preclinical studies, on the combining synergistic effects of OV to several chemotherapies [144].

However, it is imperative to define the molecular mechanisms involved in the beneficial aspect of an individual therapy approach, despite the medicine adopted. This field is now translated in the clinical application for Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy. Moreover, microRNAs, a family of small noncoding RNAs implicated in the anti-cancer activity of many therapeutic agents, are shown to serve as attractive targets for the oncogene c-Myc-based combination therapy [145].

The mechanism of oxidative stress repeatedly described as a co-factor in cancer development could be a mechanism involved by cancer therapies. Many patients to decrease the side effect often need antioxidant supplementation to adjuvant therapy, which (i.e., Glutathione) [146], natural remedies [147], and other complementary and alternative medicines [148].

In this scenario, the genes encoding the familiar hallmarks of cancer must detect growth factor (GF) and GF receptors, apoptosis, multi-drug resistance, neovascularization, and invasiveness must be analyzed deeply. Also, the genetic predisposition related to factors promoting genome instability, inflammation, deregulation of metabolism and the immune system evasion/damaging must identify [149].

The ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs) are promising agents extracted from the plant with a complete damaging of the ribosomal activities [150].

Unlikely, no upgrading was seen for primary lymphoma central nervous system (PLCNS) in term of targeted therapy. The use of SMIs in PCNS and as preventing metastasis has failed [28]. Encouraging evidence supporting the addition rituximab to classical alkylating agents is growing, and a recent randomized trial (MATRix regimen) demonstrated a significantly better OS [151].

Based on this rationale, the oncologist should assess advantages and limits, regarding applicability and expenditure of the most fitting pharmacological approach to performing a customized therapy.

Finally, the Pharmacogenomic tests are mandatory for cancer targeted therapy; it can detect the variants that code mutant proteins markers, thus identifying tumors that may be susceptible to targeted therapy.

Author Contributions

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Fondazione Muto Naples, Italy for the invaluable bibliography research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Widmer, N.; Bardin, C.; Chatelut, E.; Paci, A.; Beijnen, J.; Leveque, D.; Veal, G.; Astier, A. Review of therapeutic drug monitoring of anticancer drugs part two--targeted therapies. Eur. J. Cancer 2014, 50, 2020–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Francia, R.; De Monaco, A.; Saggese, M.; Iaccarino, G.; Crisci, S.; Frigeri, F.; De Filippi, R.; Berretta, M.; Pinto, A. Pharmacological profile and Pharmacogenomics of anti-cancer drugs used for targeted therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2018, 18, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawanshi, Y.R.; Zhang, T.; Essani, K. Oncolytic viruses: Emerging options for the treatment of breast cancer. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, F.; Abadi, A.R.; Baghestani, A.R. Trends of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma cancer death rates with adjusting the effect of the human development index: The global assessment in 1990–2015. WCRJ 2019, 6, e1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.H. Gene therapy for cancer: Present status and future perspective. Mol. Cell. Ther. 2014, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firwana, B.; Sonbol, M.B.; Diab, M.; Raza, S.; Hasan, R.; Yousef, I.; Zarzour, A.; Garipalli, A.; Doll, D.; Murad, M.H.; et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors as a first-line treatment in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: A mixed-treatment comparison. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavanello, F.; Zucca, E.; Ghielmini, M. Rituximab: 13 open questions after 20 years of clinical use. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 53, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borran, M.; Mansouri, A.; Gholami K., H.; Hadjibabaie, M. Clinical experiences with temsirolimus in Glioblastoma multiforme; is it promising? A review of literature. WCRJ 2017, 4, e923. [Google Scholar]

- Garattini, L.; Curto, A.; Freemantle, N. Personalized medicine and economic evaluation in oncology: All theory and no practice? Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2015, 15, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Martino, S.; Rainone, A.; Troise, A.; Di Paolo, M.; Pugliese, S.; Zappavigna, S.; Grimaldi, A.; Valente, D. Overview of FDA-approved anti cancer drugs used for targeted therapy. WCRJ 2015, 2, e553. [Google Scholar]

- Di Francia, R.; Rainone, A.; De Monaco, A.; D’Orta, A.; Valente, D.; De Lucia, D. Pharmacogenomics of Cytochrome P450 Family enzymes: Implications for drug-drug interaction in anticancer therapy. WCRJ 2015, 2, e483. [Google Scholar]

- Crisci, S.; Di Francia, R.; Mele, S.; Vitale, P.; Ronga, G.; De Filippi, R.; Berretta, M.; Rossi, P.; Pinto, A. Overview of Targeted Drugs for Mature B-Cell Non-hodgkin Lymphomas. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fajardo-Ramirez, O.R.; Ascacio-Martinez, J.A.; Licea-Navarro, A.F.; Villela-Martinez, L.M.; Barrera-Saldana, H.A. Technological Evolution in the Development of Therapeutic Antibodies. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2015, 67, 158–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Wang, W.; Fang, G. Targeting protein-protein interaction by small molecules. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, G.J. Building better monoclonal antibody-based therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, P. Improving the efficacy of antibody-based cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, R.; Buyukberber, S.; Uner, A.; Yamac, D.; Coskun, U.; Kaya, A.O.; Ozturk, B.; Yaman, E.; Benekli, M. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan-based therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients previously treated with oxaliplatin-based regimens. Cancer Investig. 2010, 28, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.; Cambridge, G.; Isenberg, D.A.; Glennie, M.J.; Cragg, M.S.; Leandro, M. Internalization of Rituximab and the Efficiency of B Cell Depletion in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 2046–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.F.; Wu, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, H.; Ke, C.H.; Xu, Z. Construction and characterization of an anti-CD20 mAb nanocomb with exceptionally excellent lymphoma-suppressing activity. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 4783–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.K.; McBride, A.; Lawson, S.; Royball, K.; Yun, S.; Gee, K.; Bin Riaz, I.; Saleh, A.A.; Puvvada, S.; Anwer, F. Brentuximab vedotin for treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphomas: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 109, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R., Jr. A historical overview of protein kinases and their targeted small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrés, F.; LLerena, A. Simultaneous Determination of Cytochrome P450 Oxidation Capacity in Humans: A Review on the Phenotyping Cocktail Approach. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2016, 17, 1159–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Shi, J.; Zheng, W.; Tan, Y.; Cai, Z.; Huang, H. Reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation combined with imatinib has comparable event-free survival and overall survival to long-term imatinib treatment in young patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2017, 96, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.E.; Khoury, H.J.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Lipton, J.H.; Kim, D.W.; Schafhausen, P.; Matczak, E.; Leip, E.; Noonan, K.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; et al. Long-term bosutinib for chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia after failure of imatinib plus dasatinib and/or nilotinib. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talpaz, M.; Shah, N.P.; Kantarjian, H.; Donato, N.; Nicoll, J.; Paquette, R.; Cortes, J.; O’Brien, S.; Nicaise, C.; Bleickardt, E.; et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2531–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadhi, S.; Akard, L.P.; Miller, C.B.; Jillella, A.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Ericson, S.G.; Lin, F.; Warsi, G.; Radich, J. Exploratory study on the impact of switching to nilotinib in 18 patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase with suboptimal response to imatinib. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2017, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, C.; Saglio, G. Ponatinib for chronic myeloid leukaemia: Future perspectives. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 546–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigeri, F.; Arcamone, M.; Luciano, L.; Di Francia, R.; Pane, F.; Pinto, A. Systemic dasatinib fails to prevent development of central nervous system progression in a patient with BCR-ABL unmutated Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. Blood 2009, 113, 5028–5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sonbol, M.B.; Firwana, B.; Zarzour, A.; Morad, M.; Rana, V.; Tiu, R.V. Comprehensive review of JAK inhibitors in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2013, 4, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NTC03320642. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Gupta, V.; Mesa, R.A.; Deininger, M.W.; Rivera, C.E.; Sirhan, S.; Brachmann, C.B.; Collins, H.; Kawashima, J.; Xin, Y.; Verstovsek, S. A phase 1/2, open-label study evaluating twice-daily administration of momelotinib in myelofibrosis. Haematologica 2017, 102, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeage, K. Ruxolitinib: A Review in Polycythaemia Vera. Drugs 2015, 75, 1773–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendvai, N.; Yee, A.J.; Tsakos, I.; Alexander, A.; Devlin, S.M.; Hassoun, H.; Korde, N.; Lesokhin, A.M.; Landau, H.; Mailankody, S.; et al. Phase IB study of cabozantinib in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2016, 127, 2355–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT01300026. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Ragon, B.K.; Kantarjian, H.; Jabbour, E.; Ravandi, F.; Cortes, J.; Borthakur, G.; DeBose, L.; Zeng, Z.; Schneider, H.; Pemmaraju, N.; et al. Buparlisib, a PI3K inhibitor, demonstrates acceptable tolerability and preliminary activity in a phase I trial of patients with advanced leukemias. Am. J. Hematol. 2017, 92, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massacesi, C.; Di Tomaso, E.; Urban, P.; Germa, C.; Quadt, C.; Trandafir, L.; Aimone, P.; Fretault, N.; Dharan, B.; Tavorath, R.; et al. PI3K inhibitors as new cancer therapeutics: Implications for clinical trial design. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, A.; Appleman, L.J.; Tolcher, A.W.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Beeram, M.; Rasco, D.W.; Weiss, G.J.; Sachdev, J.C.; Chadha, M.; Fulk, M.; et al. First-in-human phase I study of copanlisib (BAY 80-6946), an intravenous pan-class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, A.; Berdeja, J.G.; Patel, M.R.; Flinn, I.; Gerecitano, J.F.; Neelapu, S.S.; Kelly, K.R.; Copeland, A.R.; Akins, A.; Clancy, M.S.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and preliminary activity of CUDC-907, a first-in-class, oral, dual inhibitor of HDAC and PI3K, in patients with relapsed or refractory lymphoma or multiple myeloma: An open-label, dose-escalation, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civallero, M.; Cosenza, M.; Pozzi, S.; Bari, A.; Ferri, P.; Sacchi, S. Activity of BKM120 and BEZ235 against Lymphoma Cells. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 870918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Peluso, M.; Fu, M.; Rosin, N.Y.; Burger, J.A.; Wierda, W.G.; Keating, M.J.; Faia, K.; O’Brien, S.; Kutok, J.L.; et al. The phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)-delta and gamma inhibitor, IPI-145 (Duvelisib), overcomes signals from the PI3K/AKT/S6 pathway and promotes apoptosis in CLL. Leukemia 2015, 29, 1811–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, O.; Cordero, E.; Puissant, A.; Macaulay, L.; Ramos, A.; Kabir, N.N.; Sun, J.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; Haraldsson, K.; Hemann, M.T.; et al. Aberrant activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway promotes resistance to sorafenib in AML. Oncogene 2016, 35, 5119–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, J.C. Idelalisib for the treatment of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A review of its clinical potential. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sawaf, O.; Fischer, K.; Herling, C.D.; Ritgen, M.; Böttcher, S.; Bahlo, J.; Elter, T.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Eichhorst, B.F.; Busch, R.; et al. Alemtuzumab consolidation in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: A phase I/II multicentre trial. Eur. J. Haematol. 2017, 98, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT01905813. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Kong, D.; Yamori, T. Advances in development of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 2839–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubaku, C.O.; Heffron, T.P.; Staben, S.T.; Baumgardner, M.; Blaquiere, N.; Bradley, E.; Bull, R.; Do, S.; Dotson, J.; Dudley, D.; et al. Discovery of 2-{3-[2-(1-isopropyl-3-methyl-1H-1,2-4-triazol-5-yl)-5,6-dihydrobenzo[f]imidazo[1-2-d][1,4]oxazepin-9-yl]-1H-pyrazol-1-yl}-2-methylpropanamide (GDC-0032): A β-sparing phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor with high unbound exposure and robust in vivo antitumor activity. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 4597–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NTC03207256. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.Gov (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Locatelli, S.L.; Careddu, G.; Inghirami, G.; Castagna, L.; Sportelli, P.; Santoro, A.; Carlo-Stella, C. The novel PI3K-δ inhibitor TGR-1202 enhances Brentuximab Vedotin-induced Hodgkin lymphoma cell death via mitotic arrest. Leukemia 2016, 30, 2402–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, F.T.; Gore, L.; Gao, L.; Sharma, J.; Lager, J.; Costa, L.J. Phase Ib trial of the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor voxtalisib (SAR245409) in combination with chemoimmunotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, K.; Kim, G.; Maher, V.E.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Tang, S.; Moon, Y.J.; Song, P.; Marathe, A.; Balakrishnan, S.; Zhu, H.; et al. Vandetanib for the treatment of symptomatic or progressive medullary thyroid cancer in patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic disease: U.S. Food and Drug Administration drug approval summary. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3722–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, M.; Martino, M.; Recchia, A.G.; Vigna, E.; Morabito, L.; Morabito, F. Sorafenib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2016, 25, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, M.; Rinaldi, L.; Di Benedetto, F.; Lleshi, A.; De Re, V.; Facchini, G.; De Paoli, P.; Di Francia, R. Angiogenesis Inhibitors for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Sadek, I. Sunitinib: The antiangiogenic effects and beyond. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 5495–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, M.; Almahayni, M.H.; Ahmed, S.O.; Gaballa, S.; El Fakih, R. FLT3 Inhibitors for Treating Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016, 16, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falini, B.; Martelli, M.P.; Tiacci, E. BRAF V600E mutation in hairy cell leukemia: From bench to bedside. Blood 2016, 128, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.J.; Yu, L.; Bäckesjö, C.M.; Vargas, L.; Faryal, R.; Aints, A.; Christensson, B.; Berglöf, A.; Vihinen, M.; Nore, B.F.; et al. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk): Function, regulation, and transformation with special emphasis on the PH domain. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 228, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R., Jr. Ibrutinib inhibition of Bruton protein-tyrosine kinase (BTK) in the treatment of B cell neoplasms. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 113, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghia, P.; Cuneo, A. Ibrutinib in the real world patient: Many lights and some shades. Haematologica 2016, 101, 1448–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, F.L.R. Epigenetic regulators and their impact on therapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2016, 101, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, A.; Oki, Y.; Bociek, R.G.; Kuruvilla, J.; Fanale, M.; Neelapu, S.; Copeland, A.; Buglio, D.; Galal, A.; Besterman, J.; et al. Mocetinostat for relapsed classical hodgkin’s lymphoma: An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, Y.; Younes, A.; Copeland, A.; Hagemeister, F.; Fayad, L.E.; McLaughlin, P.; Shah, J.; Fowler, N.; Romaguera, J.; Kwak, L.W.; et al. Phase I study of vorinostat in combination with standard chop in patients with newly diagnosed peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 162, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.H.; Foon, K.A.; Frankel, P.; Ruel, C.; Pulone, B.; Tuscano, J.M.; Newman, E.M. A phase 2 study of belinostat (PXD101) in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia or patients over the age of 60 with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia: A california cancer consortium study. Leuk. Lymphoma 2014, 55, 2301–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragalone, D.L. Drug Information Handbook for Oncology 2016, 14th ed.; Bragalone, D.L., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, E.M.; Groll, M. Inhibitors for the immuno- and constitutive proteasome: Current and future trends in drug development. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 8708–8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citrin, R.; Foster, J.B.; Teachey, D.T. The role of proteasome inhibition in the treatment of malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorders. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2016, 9, 873–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Doshi, S.; Nguyen, A.; Jonsson, F.; Aggarwal, S.; Rajangam, K.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Stewart, A.K.; Badros, A.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; et al. Population Pharmacokinetics and Exposure-Response Relationship of Carfilzomib in Patients With Multiple Myeloma. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 57, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambley, B.; Caimi, P.F.; William, B.M. Bortezomib for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma: An update. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2016, 7, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygin, C.; Carraway, H.E. Emerging therapies for acute myeloid leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fu, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, D. AFM13: A first-in-class tetravalent bispecific anti-CD30/CD16A antibody for NK cell-mediated immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, T.; Spencer, A. Targeting HSP 90 induces apoptosis and inhibits critical survival and proliferation pathways in multiple myeloma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolly, S.O.; Wagner, A.J.; Bendell, J.C.; Kindler, H.L.; Krug, L.M.; Seiwert, T.Y.; Zauderer, M.G.; Lolkema, M.P.; Apt, D.; Yeh, R.F.; et al. Phase I Study of Apitolisib (GDC-0980), Dual Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase and Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2874–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassler, N.M.; Merrill, D.; Bichakjian, C.K.; Brownell, I. Merkel Cell Carcinoma Therapeutic Update. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2016, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, M.; Vigna, E.; Recchia, A.G.; Morabito, L.; Mendicino, F.; Giagnuolo, G.; Morabito, F. Bendamustine in multiple myeloma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 95, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, J.F.; Pfreundschuh, M.; Trnĕný, M.; Sehn, L.H.; Catalano, J.; Csinady, E.; Moore, N.; Coiffier, B. MAIN Study Investigators. R-CHOP with or without bevacizumab in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Final MAIN study outcomes. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebeler, M.E.; Knop, S.; Viardot, A.; Kufer, P.; Topp, M.S.; Einsele, H.; Noppeney, R.; Hess, G.; Kallert, S.; Mackensen, A.; et al. Bispecific T-Cell Engager (BiTE) Antibody Construct Blinatumomab for the Treatment of Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Final Results From a Phase I Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holla, V.R.; Elamin, Y.Y.; Bailey, A.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Litzenburger, B.C.; Khotskaya, Y.B.; Sanchez, N.S.; Zeng, J.; Shufean, M.A.; Shaw, K.R.; et al. ALK: A tyrosine kinase target for cancer therapy. Mol. Case Stud. 2017, 3, a001115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagouri, F.; Terpos, E.; Kastritis, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Emerging antibodies for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2016, 21, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H. Daratumumab improves survival in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, C. An update on the role of daratumumab in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2017, 8, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitman, R.J. Recombinant immunotoxins containing truncated bacterial toxins for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. BioDrugs 2009, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N.; Vadhan-Raj, S.; Willenbacher, W.; Terpos, E.; Hungria, V.; Spencer, A.; Alexeeva, Y.; Facon, T.; Stewart, A.K.; Feng, A.; et al. Evaluating results from the multiple myeloma patient subset treated with denosumab or zoledronic acid in a randomized phase 3 trial. Blood Cancer J. 2016, 6, e378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Patel, S.P.; Kurzrock, R. PD-1-PD-L1 immune-checkpoint blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanehbandi, D.; Majidi, J.; Kazemi, T.; Baradaran, B.; Aghebati-Maleki, L. CD20-based Immunotherapy of B-cell Derived Hematologic Malignancies. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2017, 17, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharman, J.; Hawkins, M.; Kolibaba, K.; Boxer, M.; Klein, L.; Wu, M.; Hu, J.; Abella, S.; Yasenchak, C. An open-label phase 2 trial of entospletinib (GS-9973), a selective spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2015, 125, 2336–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Z.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, F.Q.; Wang, Q.L.; Wu, C.T.; Hu, X.W.; Duan, H.F. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in acute myelogenous leukaemia is associated with clinical prognosis. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 30, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calimeri, T.; Ferreri, A.J.M. m-TOR inhibitors and their potential role in haematological malignancies. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 177, 684–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, K.; Chu, P.; Murphy, T.; Clanton, D.; Berquist, L.; Molina, A.; Ho, S.N.; Vega, M.I.; Bonavida, B. Galiximab (anti-CD80)-induced growth inhibition and prolongation of survival in vivo of B-NHL tumor xenografts and potentiation by the combination with fludarabine. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omodei, D.; Acampora, D.; Russo, F.; De Filippi, R.; Severino, V.; Di Francia, R.; Frigeri, F.; Mancuso, P.; De Chiara, A.; Pinto, A.; et al. Expression of the brain transcription factor OTX1 occurs in a subset of normal germinal-center B cells and in aggressive Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 2609–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekeres, M.A.; Maciejewski, J.P.; Erba, H.P.; Afable, M.; Englehaupt, R.; Sobecks, R.; Advani, A.; Seel, S.; Chan, J.; Kalaycio, M.E. A Phase 2 study of combination therapy with arsenic trioxide and gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 2011, 117, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, G.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Martinelli, V.; Ruggeri, M.; Nobile, F.; Specchia, G.; Pogliani, E.M.; Olimpieri, O.M.; Fioritoni, G.; Musolino, C.; et al. A phase, II study of givinostat in combination with hydroxycarbamide in patients with polycythaemia vera unresponsive to hydroxycarbamide monotherapy. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 161, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.; Winer, E.; Quesenberry, P. Newer monoclonal antibodies for hematological malignancies. Exp. Hematol. 2008, 36, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanazzi, A.; Grana, C.; Crosta, C.; Pruneri, G.; Rizzo, S.; Radice, D.; Pinto, A.; Calabrese, L.; Paganelli, G.; Martinelli, G. Efficacy of ⁹⁰Yttrium-ibritumomab tiuxetan in relapsed/refractory extranodal marginal-zone lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 32, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, D.; Korman, A.; Peck, R.; Feltquate, D.; Lonberg, N.; Canetta, R. The development of immunomodulatory monoclonal antibodies as a new therapeutic modality for cancer: The Bristol-Myers Squibb experience. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 148, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, S.M.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Koenig, P.A.; LaPlant, B.R.; Kabat, B.F.; Fernando, D.; Habermann, T.M.; Inwards, D.J.; Verma, M.; Yamada, R.; et al. Phase I study of ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, in patients with relapsed and refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6446–6453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, S.M.; Horwitz, S.M.; Engert, A.; Khan, K.D.; Lin, T.; Strair, R.; Keler, T.; Graziano, R.; Blanset, D.; Yellin, M.; et al. Phase I/II study of an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody (MDX-060) in Hodgkin’s lymphoma and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2764–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.G.; Moreau, P.; Laubach, J.P.; Gupta, N.; Hui, A.M.; Anderson, K.C.; San Miguel, J.F.; Kumar, S. The investigational proteasome inhibitor ixazomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. 2015, 11, 1153–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Tresckow, B.; Morschhauser, F.; Ribrag, V.; Topp, M.S.; Chien, C.; Seetharam, S.; Aquino, R.; Kotoulek, S.; de Boer, C.J.; Engert, A. An Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase I/II Study of JNJ-40346527, a CSF-1R Inhibitor, in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT01572519. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- May, R.D.; Fung, M. Strategies targeting the IL-4/IL-13 axes in disease. Cytokine 2015, 75, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT00441818. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Raedler, L.A. Revlimid (Lenalidomide) Now FDA Approved as First-Line Therapy for Patients with Multiple Myeloma. Am. Health Drug Benefits. 2016, 9, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Gribben, J.G.; Fowler, N.; Morschhauser, F. Mechanisms of Action of Lenalidomide in B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2803–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanale, M.; Assouline, S.; Kuruvilla, J.; Solal-Céligny, P.; Heo, D.S.; Verhoef, G.; Corradini, P.; Abramson, J.S.; Offner, F.; Engert, A.; et al. Phase IA/II, multicentre, open-label study of the CD40 antagonistic monoclonal antibody lucatumumab in adult patients with advanced non-Hodgkin or Hodgkin lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 164, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardarelli, P.M.; Moldovan-Loomis, M.C.; Preston, B.; Black, A.; Passmore, D.; Chen, T.H.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.; Kuhne, M.R.; Srinivasan, M.; et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of MDX-1401 for therapy of malignant lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3376–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimelius, I.; Diepstra, A. Novel treatment concepts in Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 281, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobinai, K.; Klein, C.; Oya, N.; Fingerle-Rowson, G. A Review of Obinutuzumab (GA101), a Novel Type II Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody, for the Treatment of Patients with B-Cell Malignancies. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 324–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidala, J.; Kim, J.; Betts, B.C.; Alsina, M.; Ayala, E.; Fernandez, H.F.; Field, T.; Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A.; Locke, F.L.; Mishra, A.; et al. Ofatumumab in combination with glucocorticoids for primary therapy of chronic graft-versus-host disease: Phase I trial results. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015, 21, 1074–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buske, C. Ofatumumab: Another way to target CD20 in Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia? Lancet Haematol. 2017, 4, e4–e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréan, A.; Lord, C.J.; Ashworth, A. PARP inhibitor combination therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 108, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, D. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ONO/GS-4059: From bench to bedside. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Farsani, M.A.; Khadem, P.; Khazaei, Z.; Mezginejad, F.; Shagerdi, N.E.; Khosravi, M.R.; Mohammadi, M.H. Evaluation of P14ARF, P27kip1 and P21Cip1, cell cycle regulatory genes, expression in acute myeloid leukemia patients. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1186. [Google Scholar]

- Platzbecker, U.; Al-Ali, H.K.; Gattermann, N.; Haase, D.; Janzen, V.; Krauter, J.; Götze, K.; Schlenk, R.; Nolte, F.; Letsch, A.; et al. Phase 2 study of oral panobinostat (LBH589) with or without erythropoietin in heavily transfusion-dependent ipss low or int-1 mds patients. Leukemia 2014, 28, 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, S.; Marotta, G.; Abbadessa, A.; Jianping, M.; Fulciniti, F.; Santorelli, A. B-cell polyclonal lymphocytosis in a woman with bone marrow involvement by breast cancer cells. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1040. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, E.D. Pembrolizumab: A Review in Advanced Melanoma. Drugs 2016, 76, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NTC03291288. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Merli, M.; Ferrario, A.; Maffioli, M.; Olivares, C.; Stasia, A.; Arcaini, L.; Passamonti, F. New uses for brentuximab vedotin and novel antibody drug conjugates in lymphoma. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2016, 9, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzeau, C.; Moreau, P. Pomalidomide in the management of relapsed multiple myeloma. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintas-Cardama, A.; Kantarjian, H.; Estrov, Z.; Borthakur, G.; Cortes, J.; Verstovsek, S. Therapy with the histone deacetylase inhibitor pracinostat for patients with myelofibrosis. Leuk. Res. 2012, 36, 1124–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, A.T.; Ang, J.E.; Lal, R.; Olmos, D.; Molife, L.R.; Kristeleit, R.; Parker, A.; Casamayor, I.; Olaleye, M.; Mais, A.; et al. First-in-human, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic phase I study of Resminostat, an oral histone deacetylase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5494–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, S.Z.; Bona, R.; Li, Z. 17 AAG for HSP90 inhibition in cancer—From bench to bedside. Curr. Mol. Med. 2009, 9, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrich, A.; Nabhan, C. Use of class I histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin in combination regimens. Leuk. Lymphoma 2016, 57, 1755–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongero, D.; Paoluzzi, L.; Marchi, E.; Zullo, K.M.; Neisa, R.; Mao, Y.; Escandon, R.; Wood, K.; O’Connor, O.A. The novel kinesin spindle protein (KSP) inhibitor SB-743921 exhibits marked activity in in vivo and in vitro models of aggressive large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2015, 56, 2945–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, N.L.; Younes, A.; Carabasi, M.H.; Forero, A.; Rosenblatt, J.D.; Leonard, J.P.; Bernstein, S.H.; Bociek, R.G.; Lorenz, J.M.; Hart, B.W.; et al. A phase 1 multidose study of SGN-30 immunotherapy in patients with refractory or recurrent CD30+ hematologic malignancies. Blood 2008, 111, 1848–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, T.; Hajek, R. Monoclonal antibodies—A new era in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Blood Rev. 2016, 30, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NTC02111200. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Irvine, D.A.; Zhang, B.; Kinstrie, R.; Tarafdar, A.; Morrison, H.; Campbell, V.L.; Moka, H.A.; Ho, Y.; Nixon, C.; Manley, P.W.; et al. Deregulated hedgehog pathway signaling is inhibited by the smoothened antagonist LDE225 (Sonidegib) in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh, A.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Mezginezhad, F.; Nezhad, H.A.; Parkhideh, S.; Khosravi, M.; Khazaei, Z.; Adineh, H.A.; Farsani, M.A. The expression of the TP53 gene in various classes of acute myeloid leukemia. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1178. [Google Scholar]

- Soumyanarayanan, U.; Dymock, B.W. Recently discovered EZH2 and, EHMT2 (G9a) inhibitors. Future Med. Chem. 2016, 8, 1635–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, R.M. Temsirolimus: A safety and efficacy review. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2012, 11, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizaki, M.; Tabayashi, T. The Role of Intracellular Signaling Pathways in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Myeloma and Novel Therapeutic Approaches. J. Clin. Exp. Hematop. 2016, 56, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.J. A review of tositumomab and I (131) tositumomab radioimmunotherapy for the treatment of follicular lymphoma. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2005, 5, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolcher, A.W.; Patnaik, A.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Rasco, D.W.; Becerra, C.R.; Allred, A.J.; Orford, K.; Aktan, G.; Ferron-Brady, G.; Ibrahim, N.; et al. Phase I study of the MEK inhibitor trametinib in combination with the AKT inhibitor afuresertib in patients with solid tumors and multiple myeloma. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 75, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmi, N.; Asiri, B.; Al-jehani, W.; Al-hashmi, R.; Al-Gamdi, S.; Abdulsabour, R. Clinical feasibility of immunotherapy for acute leukemia—A review. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1176. [Google Scholar]

- Touzeau, C.; Le Gouill, S.; Mahé, B.; Boudreault, J.S.; Gastinne, T.; Blin, N.; Caillon, H.; Dousset, C.; Amiot, M.; Moreau, P. Deep and sustained response after venetoclax therapy in a patient with very advanced refractory myeloma with translocation t(11;14). Haematologica 2017, 102, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Matsui, W. Hedgehog pathway as a drug target: Smoothened inhibitors in development. OncoTargets Ther. 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, D.; Park, J.A.; Demock, K.; Marinaro, J.; Perez, A.M.; Lin, M.H.; Tian, L.; Mashtare, T.J.; Murphy, M.; Prey, J.; et al. Aflibercept exerts antivascular effects and enhances levels of anthracycline chemotherapy in vivo in human acute myeloid leukemia models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 2737–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zager, J.S.; Eroglu, Z. Encorafenib/binimetinib for the treatment of BRAF-mutant advanced, unresectable, or metastatic melanoma: Design, development, and potential place in therapy. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 9081–9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, M.; Di Benedetto, F.; Di Francia, R.; Lo Menzo, E.; Palmeri, S.; De Paoli, P.; Tirelli, U. Colorectal cancer in elderly patients: From best supportive care tocure. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Roda, D.; Yap, T.A. Strategies for modern biomarker and drug development in oncology. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2014, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francia, R.; Valente, D.; Catapano, O.; Rupolo, M.; Tirelli, U.; Berretta, M. Knowledge and skills needs for health professions about pharmacogenomics testing field. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 16, 781–788. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, D.A.; Chen, Q.; Ayer, T.; Howard, D.H.; Lipscomb, J.; El-Rayes, B.F.; Flowers, C.R. First- and second-line bevacizumab in addition to chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: A United States-based cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescente, G.; Di Iorio, C.; Di Paolo, M.; La Campora, M.G.; Pugliese, S.; Troisi, A.; Muto, T.; Licito, A. De Monaco, A. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) and its variants as simple and cost effective for genotyping method. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1116. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadian, M.; Pakzad, R.; Mohammadian-Hafshejani, A.; Salehiniya, H. A study on the incidence and mortality of leukemia and their association with the human development index (HDI) worldwide in 2012. WCRJ 2018, 5, e1080. [Google Scholar]

- Bressy, C.; Benihoud, K. Association of oncolytic adenoviruses with chemotherapies: An overview and future directions. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 90, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Zhou, H.; Qu, L. Attacking c-Myc: Targeted and combined therapies for cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 6543–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkovic, L.; Siems, W.; Siems, R.; Zarkovic, N. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in carcinogenesis and integrative therapy of cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 6529–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francia, R.; Siesto, R.S.; Valente, D.; Del Buono, A.; Pugliese, S.; Cecere, S.; Cavaliere, C.; Nasti, G.; Facchini, G.; Berretta, M. Current strategies to minimize toxicity of oxaliplatin: Selection of pharmacogenomic panel tests. Anticancer Drugs 2013, 24, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, M.; Della Pepa, C.; Tralongo, P.; Fulvi, A.; Martellotta, F.; Lleshi, A.; Nasti, G.; Fisichella, R.; Romano, C.; De Divitiis, C.; et al. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) in cancer patients: An Italian multicenter survey. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 24401–24414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembic, Z. Pharmaco-therapeutic challenges in cancer biology with focus on the immune—System related risk factors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 6652–6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santorelli, A.; Di Francia, R.; Marlino, S.; De Monaco, A.; Ghanem, A.; Rossano, F.; Di Martino, S. Molecular diagnostic methods for early detection of breast Implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma in plastic surgery procedures. WCRJ 2017, 4, e982. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri, A.J.; Cwynarski, K.; Pulczynski, E.; Ponzoni, M.; Deckert, M.; Politi, L.S.; Torri, V.; Fox, C.B.; Rosée, P.L.; Schorb, E.; et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: Results of the first randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 (IELSG32) phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e217–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).