Abstract

The study objective is to empirically examine the mediating role of organizational culture on entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and business performance relationships in Algerian manufacturing SMEs. A sample of 180 Algerian Small medium enterprise (SME) owners/managers was collected for the year 2021 by using structured questionnaires. This study has contributed to the existing theory by evaluating the mediating role of Organizational Culture (OC) by using interaction effect in partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The results have supported the hypothesized direct and mediate relationship: Entrepreneurial Orientation has the highest effect on the Organizational culture. On the other hand, Entrepreneurial Orientation has a medium influence on business performance. In addition, Organizational culture has a medium influence on business performance. Additionally, Entrepreneurial orientation and organizational culture together explain 50.2% of the variances for the business performance construct. On the other hand, 38.9% of the variances are explained by the entrepreneurial orientation for the organizational culture construct. Their relationship receives considerable scholarly attention in the literature, but few studies have been conducted among Algerian manufacturing SMEs. Hence, this investigation’s purpose is to add to the research in the newer context of Algeria. Thus, this study was an attempt to bridge this gap in the literature. This study can be used to supplement existing theories on organizational culture and small-business performance. This paper discovers an excellent link between entrepreneurial orientation and small and medium enterprise performance, with organizational culture as a partial mediating factor. This research also has significant implications for academics and practitioners to understand better entrepreneurial orientation, organizational culture perspectives, and organizational performance. The conclusions have been empirically intended to help SME authorities and future academics understand the function of entrepreneurial orientation and culture in improving the organizational performance of SMEs, particularly in North Africa.

1. Introduction

Despite the fact that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) dominate the economy in terms of size and employment, they produce low-value-added products/services and exports.

However, resource constraints, informal strategies, and flexible structures are common, diminishing their resilience and placing them at danger from growing competition [1]. The lack of innovation and creativity in SMEs is one of the reasons for these difficulties [2]. According to [3,4], a large number of SMEs fail as a result of their failure to implement an Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) strategy. Consequently, SMEs may have been left out of regulatory and social pressures. Nonetheless, the time has come when disregarding SMEs’ environmental implications is no longer an option [5]. Entrepreneurship activity in Algeria has witnessed a surge in the establishment of companies and the openness of the state sector to private initiatives, starting with the first investment law in Algeria in 1993 and so on. At present, Algeria is encouraging entrepreneurs and supporting them in establishing small businesses to absorb unemployment and to create a general economic climate conducive to the establishment of businesses (finance, taxation, regulation) and stimulate business leadership through a set of specific stimulus measures [6]. The term entrepreneurship originates from the French word “entreprendre”, meaning to undertake. Idrus et al. (2020) [7] predict that entrepreneurship can be explained as a combination of recourses in new ways to create something valuable [8]. According to [9], one of the most widely used constructs to assess firm entrepreneurship is EO. EO can be defined as “a firm strategic posture toward entrepreneurship” and is a vibrant topic in entrepreneurship research [10]. SMEs apply entrepreneurial orientation as their entrepreneurial strategy and put it into their strategic planning, then their business may grow significantly [2].

Entrepreneurial orientation literature discusses a relationship between firms’ EO attitudes and organizational performance [11], but few studies have been conducted among Algerian manufacturing SMEs. Thus, EO–performance relationship suggests the need for further research from an Algerian perspective. Hence, this paper’s scope offers a deeper assessment of the mediating role of organizational culture between EO and business performance in Algerian manufacturing SMEs.

Based on the above discussion, our research questions are: Does EO influence firm performance? To what extent does the context of organizational culture mediate the relationship between EO and business performance?

2. Related Work: Entrepreneurial Orientation, SME Performance, and Organizational Culture

2.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation

Entrepreneurial orientation has its origins in the literature on the strategy-making process [12,13]. Because of the attention, it has received from researchers in business and management, and it has produced a considerable lot of knowledge [4,14,15,16,17]. The importance of aggressively seeking new market opportunities is more highly valued in an entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurial orientation is traditionally assessed using three criteria: innovativeness, risk-taking, and pro-activeness. [2,14,16,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Whereas company behavior reflects innovativeness and pro-activeness, entrepreneurial attitude reflects risk-taking. [24]. Other elements, such as autonomy and competition, are included in a broader approach to entrepreneurial orientation [12,17,25,26,27,28,29]. A one-dimensional approach, in which a company can only be described as entrepreneurial if all elements of its entrepreneurial posture are highly developed, and a multidimensional approach, in which a company can be treated as entrepreneurial even if not all components of its entrepreneurial stance are highly developed [26]. Entrepreneurial orientation, defined as a strategy-making process that provides businesses with a framework for making entrepreneurial decisions and taking action to attain a competitive edge, is one technique to develop entrepreneurial thinking [28]. The term EO refers to a company’s attitude of promoting excellent performance to obtain a competitive advantage. Entrepreneurially oriented companies encourage their staff to decide on their own, actively propose innovations, take measured risks, act proactively, and compete aggressively with competitors [19]. This study will concentrate on Miller’s three EO factors: innovativeness, pro-activeness, and risk-taking, deemed sufficient to reflect entrepreneurial orientation as a one-dimensional construct. Organizations could benefit from adopting an EO from a conceptual standpoint since a fast-changing environment makes future earnings from existing enterprises unclear, and firms must constantly find new opportunities [30]. EO is a market-driving method that businesses utilize to develop business prospects and markets in various industries [23]; as a result, it is an essential antecedent to firm-level entrepreneurship and performance [31]. Similarly, many authors see this perspective as a managerial trait that might help businesses enhance decision making [17,32].

2.1.1. Innovativeness

The process of creative destruction, according to [33], leads to innovation. Muriithi et al. (2019) [34] emphasized the importance of innovation in EO [4]. The support of new ideas, innovation, experimentation, newness or improvement to processes or items, or the search of new markets is defined as innovativeness in an organization [28]. Organizational techniques and routines are more likely to be developed by innovative companies [35]. Entrepreneurial enterprises concentrate on innovative processes and concepts that can help organizations increase their innovation skills and improve their innovation performance to meet their consumers and markets [23].

2.1.2. Risk-Taking

The propensity of entrepreneurs and managers to take risks in favor of change and innovation affects the extent to which a firm displays entrepreneurial orientation, according to [36]. The degree to which managers will make significant and dangerous resource commitments, i.e., those with a reasonable likelihood of costly failures, is characterized as risk-taking [22]. A risk-taking mindset refers to the extent to which managers are ready to use corporate resources to accomplish projects with unclear outcomes and significant failure costs [19]. Taking risks causes developing bold initiatives that require enormous resources [16]. As a result, controlling the risk of introducing innovative products causes entrepreneurs to succeed [37].

2.1.3. Proactiveness

Proactiveness is defined as “seeking new opportunities which may or may not be related to the present line of operations, introduction of new products and brands ahead of the competition, strategically eliminating operations which are in the mature or declining stages of the life cycle” [22]. Proactivity can also be defined as the capacity to mobilize resources to provide innovative products and services ahead of the competition [16]. Proactive businesses might identify new opportunities through inter-organizational activities such as knowledge sharing [35,38]. Proactivity demonstrates a company’s ability to spot and capitalize on lucrative market possibilities before its competitors [19].

2.2. SME Performance

SME is well-known over the world as a source of economic liberty [39]. In SMEs, business is primarily personal, with frequent direct contact between its owners and clients [40]. The current competitive environment has prompted SMEs to seek strategies to boost their innovativeness and competitiveness [41]. Furthermore, the SME sector’s survival and improved performance depend on supportive policies, enhanced organizational culture (OC), and entrepreneurial abilities to drive and build the industry [39]. Similarly, a recent study found that SMEs’ ability to provide more excellent customer value and seek entrepreneurial opportunities affects their success; however, to do so, SMEs must combine EO with market orientation [32]. According to [42], choosing an EO strategy inside an organization, particularly in SMEs, will positively affect performance if the enterprise (EO) considers various business factors setting the managers’ objectives. In most situations, the CEO’s or other managers’ responses to the survey are used to assess the firm’s performance. Slater et al. (1998) [43] suggested that the owner/general manager’s self-reports of firm success were highly associated with archival data in the same setting [44]. There is no consensus on firm performance. According to [45], Organizational performance is a metric that measures and evaluates a company’s ability to create and deliver value to its internal and external customers [46].

Furthermore, as the outputs of organizational actions, company performance can be measured in financial and non-financial terms [47]. Non-financial measures include goals such as satisfaction and worldwide success ratings made by owners or business management. Financial metrics include sales growth and return on investment [13]. Many researchers argue that financial performance indicators are too historical to provide a clear picture of an enterprise’s performance. Still, looking objectively at the situation, we can see that the first thing that defines the state of the enterprise is the level of profit and turnover, according to [48,49]. Although corporate performance has generally been measured using account-based measurements, it is difficult to dismiss the arguments of those who advocated for non-financial indicators, arguing that financial measures lack a strategic focus, which could lead to errors in anticipating future performance [46]. Existing business metrics (sales growth and market share), as well as the firm’s future posture (new product development and diversification), are used to determine market-related elements, including growth, market share, diversification, and product development [50]. In agreement with this, the firm’s overall performance (PER) in the previous 24 months was measured on 8 factors, precisely 5 financial performance metrics (sales growth, profit growth, return on investment, net income, and market value) and 3 market performance measures, according to [50] (Speed to market, market share, and penetration rate). Objective and subjective metrics were employed in the evaluation of company performance, according to the proposal of [42], which was based on the work of [51,52]. Because respondents are often hesitant to share financial information, and because objective data for some of the performance dimensions we want to measure are not available, it prefers to use subjective measures, as suggested by [51], the business performance is divided into four categories: There are three aspects to financial performance (revenue growth, employed growth, and profit margin). There is only one metric for measuring community performance. There are three aspects of customer performance (customer service quality, variety of customer service, customer satisfaction). In the current study, we rely on these four performance metrics for sustainable development performance (environmental respect and sustainable development).

2.3. Organizational Culture

According to [53], culture determines how people behave; hence, it is unquestionably essential to understand an organization’s culture [54]. OC was defined in a variety of ways, according to a thorough review of the literature. However, there is agreement on group values, beliefs, practices, and assumptions that guide organization members in day-to-day work activities [55,56]; however, it is difficult to decipher because it includes “values, beliefs, and assumptions” that are not easily measurable [10]. “A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be valid and, thus, to be taught to new members as the correct way you perceive, think, and feel about those problems,” according to [4,49,57,58,59,60,61,62]. The functionalist paradigm assumes that all companies’ cultures serve the same functions: It influences behavior, such as decisions about digital technology adoption, and provides organizational members with a feeling of self. As a result, new technology may alter behavior and impact company culture [63]. In addition, the OC is regarded as a distinctive and inimitable capability of an organization [56]. According to the literature, organizational culture is defined by core principles, behavioral norms, and behaviors/artifacts; these levels are inextricably linked [18]. The artifact is the most visible and conscious level [59]. In SMEs, it is tough to tell the difference between management and ownership. The owner-manager influences the company’s principles or culture and strategic approach [40,49]. Small businesses have a more organic culture than large corporations because shared beliefs and values frequently bond small individuals. Changing the corporate culture in SMEs should be a priority [49]. Furthermore, according to [64], the culture of small businesses is more informal but not necessarily more relaxed [4]. To fully grasp the complexity of the cultural phenomenon, we rely on four organizational culture types that have been used in recent literature [4,10,60,65,66,67,68]. Zaheer and Zaheer (2006) [69] devised the competing value framework CVF, which comprises analytical values of an organization [67] that may be formed by crossing two major value dimensions: The first dimension indicates how much flexibility they provide versus how much control they provide [70]; the second dimension shows whether an organization emphasizes an internal orientation that emphasizes integration and collaboration or an external orientation that emphasizes differentiation and competition [68]. Each form of organizational culture is defined by a set of conflicting values that, in turn, describe the HRM environment [66].

2.3.1. Clan Culture

Clan culture is defined by teamwork, employee involvement programs, and corporate commitment to the employee, according to [4,62]. It emphasizes ideals such as cohesion, participation, and personal atmosphere through organic processes (e.g., flexibility and spontaneity) and internal maintenance (e.g., integration) [60]. Due to restricted borders that prevent external interactions, fresh ideas may not be generated [10].

2.3.2. Adhocracy Culture

An Adhocracy culture give an external orientation and flexibility, and organizational characteristics that enable adhocracy culture include creativity, entrepreneurship, and risk-taking [70]. It has resulted in a high level of experimentation commitment [67]. Producing innovative products and services and quickly adapting to new opportunities is crucial for these firms [62].

2.3.3. Hierarchy Culture

Work standards, systematic processes, explicit norms, and policies to regulate internal operations characterize a hierarchical culture [62,65]. Stability, predictability, and efficiency are the organization’s long-term concerns, maintaining efficient, reliable, rapid, and smooth-flowing production at the center of the Key values [62].

2.3.4. Market Culture

Market culture emphasizes stability and control, creates a workplace with competitive driving efficiency, and concentrates on external transactions with suppliers and customers, intending to obtain CA [65]. It attempts to reduce the market’s level of uncertainty [10]. Leaders in this type of company are demanding, challenging, and have well-defined goals [67]. According to [62], the primary organizational cultures are hierarchy, clan, market, and adhocracy corporate culture [4].

2.4. Entrepreneurial Orientation and SME Performance

Over the years, the relationship between the entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance has received a lot of attention. Researchers have identified EO as a strong predictor of company performance, and more research is needed [11,24]. Given the effect of EO on corporate performance, scholarly theory suggests that firms gain from developing risk-taking, proactiveness, and innovativeness attitudes. However, not all dimensions affect business performance in the same way. Indeed, the potential for EO dimensions to be combined and the ramifications that arise are highly diverse [14]. In the same vein, Hernández-Linares (2019) [20] concluded that blindly pursuing universal adoption of EO dimensions is not an effective method to gain an edge. Del Rosario and René (2017) [71] stated that EO might help a company move faster and stay ahead of the competition. EO is frequently thought of as a higher-order concept. The performance factors may differ from each component of the EO construct (i.e., pro-activeness, innovativeness, risk-taking, and resource-leveraging) [39]. While SMEs and their business performance are essential to the Owner/CEO/Manager, the research suggests an absence of accurate understanding and information about which entrepreneurial aspects influence SMEs’ performance and performance [17]. Prior studies have looked into how EO affects organizational performance in depth [13,22,23,32]. Most research have discovered that EO has a beneficial impact on firm performance [14,15,17,22,32,39]. Many of these researchers treat EO as if it were a single entity. They show that EO has a similar impact on firm performance in various settings, including diverse countries, marketplaces, and types of businesses [22]. According to [72], there is a skewed link between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. Instead, it takes the shape of an inverted U [17,37,73], signaling that either a high or low entrepreneurial orientation is undesirable [17]. It implies that additional factors may act as mediators or moderators in the relationship [37]. In new ventures, the association between entrepreneurial inclinations and performance is inverse U-shaped, whereas, in established enterprises, the relationship is positive [73]. The strength of the association between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance has been seen to vary depending on the type of performance measurements used [17]. Alternatively, Rauch (2009) [18] suggested that the positive association between EO and performance is resistant to alternative measures of EO, as well as changes in performance measurement (financial versus nonfinancial). Kashan et al. (2021) [74] discovered evidence of a direct link between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. Their meta-analysis [13] empirically confirms the favorable association between EO and company performance. However, they do see a lot of variation in impact sizes, and they recommend that future studies look into how EO interacts with other variables in their relationship with performance [30]. Wiklund and Shepherd (2003) [75] noted that creative ideas, inventive behavior, and entrepreneurial-oriented knowledge are essential variables in generating industry-based SME activities. A more robust entrepreneurial spirit resulted in higher risk-taking capacity and improved SME success [24]. SMEs should achieve the strongest growth results with an entrepreneurial strategic posture that holds temporally salient market information, is more structurally adaptive (e.g., is younger), and has an intangible resource advantage relative to their industry rivals [76]. SMEs with higher EO “will do better in overseas markets because they possess the competencies needed to design new strategies that provide an edge in the foreign market,” according to [77] (p. 1165), “discover and use technologies that better correspond with the needs of foreign market customers, and are prepared to assume the business risks that come with implementing new strategies and technology in new markets” [77].

The following relationship is hypothesized.

Hypothesis 1.

There is a positive effect of entrepreneurial orientation on Algerian SME Performance.

2.5. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organizational Culture

Many recent studies that have indicated that the EO strategy has a significant impact on SME culture support the association between EO strategy and OC [4,29,39]. As a result, in entrepreneurship studies, OC is recognized as an essential progenitor of entrepreneurial decision making [39]. “To build an innovative culture, certain requirements must be met,” “involving six types of attitudes: the ability of managers to take risks, encouraging creativity, participation of all employees in building an innovative culture, the responsibility of both managers and employees for their actions, allowing employees to develop their interests and use their unique skills” [4]. Organizational culture is viewed as a critical strategic resource that can help a company gain a competitive edge by encouraging and sustaining entrepreneurial initiatives [18]. The dimension of flexibility-discretion of action influences EO because it allows employees freedom and autonomy, allowing them to build a new mindset, create new ways of working, producing, and thinking creatively interchange more ideas and develop entrepreneurial behavior. According to entrepreneurship studies, organizational culture is a crucial antecedent of entrepreneurial decision-making in the same environment. It is also offered when EO might or might not appear [31].

Furthermore, in an organizational setting, innovation is frequently manifested through specific behaviors such as learning, information sharing, and experimenting, all of which are ultimately tied to a concrete action or result. Innovative firms, it is believed, embed an innovation orientation in their organizational culture to ensure that the intensity and consistency of creative behaviors are strengthened throughout the organization’s many locations, administrative units, and workers [70]. We can state that:

Hypothesis 2.

There is a significant positive effect of entrepreneurial orientation on organizational culture.

2.6. Mediating Role of Organizational Culture on Entrepreneurial Orientation and SME Performance Relationship

According to contingency theory, the amount of a third variable influences the relationship between two variables [13]. Contingency techniques focus on a single variable and investigate how the Entrepreneurial Orientation-performance links are affected by a specific component [71]. However, a few studies have focused on specific internal firm aspects that play a role in the relationship between EO and firm performance; these studies focus on internal factors such as functional performances [22], national culture [62], Managerial Power [44], The Financing Structure [12]. When aligned with company culture, entrepreneurial orientation guides strategy and approach toward establishing new market products, developing market niches, and growing commercial operations [37]. Furthermore, the country’s diverse cultural origins make it possible to replicate and test the EO–performance relationship [11]. Schein (1992) [63] polled project managers, engineers, and executives from 76 companies in the United States. According to the findings, a clan or group culture fosters a cohesive, high-performing teamwork environment, which leads to an improved project and business outcomes [73]. Both practitioners and researchers should be interested in studying the culture–performance relationship [46,49,54,68]. Studies in strategy and organizational behavior have highlighted the importance of corporate culture for business growth, effectiveness, and competitive advantage since the 1980s [31]. However, Dess and Robinson (1984) [56]’s research emphasizes the organizational culture’s importance in enhancing organizational performance. Engelen et al. (2014) [65] also stressed the importance of OC, claiming that it significantly affects employee attitudes and contributes considerably to organizational performance [65]. In this sense, corporate culture may be critical to a company’s success [68]. Articulating the “right” set of cultural values will: generate excitement, high morale, and intense commitment to a company and its goals; clarify the behaviors expected of employees; galvanize their potential productivity. The primary role of leaders within organizations originates from the formation and maintenance of culture to build a culture of workplace suitability. As a result, employee satisfaction and organizational performance may improve [55], and businesses with excellent sustainability performance exhibit a distinct organizational culture [63].

We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3.

Organizational culture has positive effect on business performance.

Hypothesis 4.

Organizational culture mediates the relationship between EO and business performance.

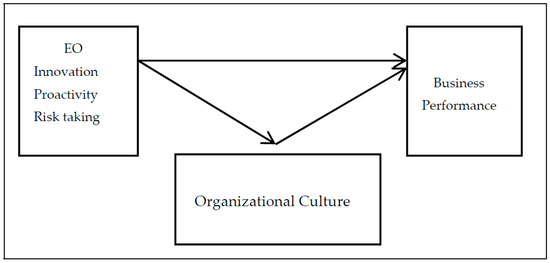

The following Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual framework of our study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Research Methodology

Authors face a variety of challenges when collecting data, including non-response to mail surveys. To get around this, authors conducted face-to-face interviews and used structured questionnaires to collect data.

According to previous research that have examined the correlation between Entrepreneurial Orientation and firm performance, we adjusted the questionnaire to the Algerian context. There were three sections in the questionnaire. The first part (A) comprises the respondent’s and firm’s profiles. The second part (B) contains the questions relative to EO, while the last part (C) includes measuring Firm performance. We select a sample of 180 Algerian manufacturing SMEs business owners/managers. Our sample of firms is drawn from a list compiled by the Ministry of Industry and Mines, with an emphasis on manufacturing firms. These companies’ responses to 101 questionnaires were examined and evaluated, with a response rate of 56.11%.

We see that the dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (innovation, risk-taking, and proactivity), as well as the independent variable are more important in industrial SMEs than in other sectors of activity. We have focused on this sector because there is a greater need and/or potential for innovation and local/national/global competition for customers.

3.1. Variables Measurement

3.1.1. Measurement of the Dependent Variable

According to the literature, there is no agreement on the notion of performance measurement. In our instance, we use four indicators: Financial Performance, Community Performance, Sustainable Development Performance, and Customer Performance, as proposed by [42] based on the study of [51,52].

3.1.2. Measurement of the Independent Variable

Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO): this term has been assessed using a widely used and validated in earlier research [13,36, measuring the business’s emphasis on risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity. In our research, we utilized a five-point Likert scale to assess these three aspects of EO (5 = strongly agree and 1 = strongly disagree).

Azeem et al. (2021) [70] developed the organizational culture assessment instrument (OCAI) to measure the mediating influence of culture. These sorts of organizational cultures are referred to as Adhocracy culture, Clan culture, Hierarchy culture, and Market culture are all terms used to describe these types of corporate cultures [69].

In order to operationalize the variables of our research, we will use a 5-level Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The following Table 1 explains the operationalization of the variables.

Table 1.

Description of variables.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

We used the non-probability method. The sample in this case is constituted according to a reasoned choice; it is made according to a certain number of criteria. (Mayrfoer, U, 2006, p45) In the case of our research, we sent the questionnaire to 180 manufacturing SMEs, and we received the answer of 101 companies from different Algerian states. (Relizane, Oran and Mostaghanem).

In this work, we use the face-to-face administration of the questionnaire for data collection. This is the preliminary step that encouraged us to make this choice since the other modes of administration (postal mail, telephone, e-mail) did not yield any results.

It is imperative to motivate this choice: the first argument we can use to justify the choice of the face-to-face meeting is the reliability of the information collected from the entrepreneurs.

The face-to-face administration is more appropriate to the specificities of the Algerian context and to the particularities of the population (SME managers).

Often, Algerian entrepreneurs almost never answer the questionnaires that are sent to them. This refusal to answer is explained by two main reasons:

- The information concerning the management of his company is considered as confidential.

- Information about their behavior is personal.

The face-to-face questionnaire helps to overcome these difficulties; by talking directly with the business owners, it is easier to convince them to respond. Among the arguments used to “attract” their agreement are the following:

- The questionnaire is not very long and does not require much time to answer.

- The questionnaire is anonymous: the names of the companies that responded are not published.

According to the Chamber of Commerce in Relizane, Mostaghanem and Oran (2020), the overall number of industrial SMEs is around 2000 small and medium enterprises. In order to calculate the sample size, we depend on the following:

The number of items is times the value between (5–10), which is determined by the researcher’s estimate [1]. So, 31 times 6, we have 186 individuals. In this context, only 101 of the received answers were approved. The sample size was therefore stabilized at 101, whereas the size of the community was estimated to be around 2000 industrial SMEs, of which the size of the sample exceeds 5%. Whereas the sample is purposive, it is representative of the research community.

Since the 2000s, the establishment of businesses in Algeria has accelerated dramatically. As of the end of the first half of 2019, SMEs in Algeria account for 1,171,945 businesses, making up a considerable economic component. The bulk of SMEs is engaged in services, handicrafts, and the BTPH, with industrial SMEs accounting for only 8.71 percent (Newsletter SME Statistics n°35, Ministry of Industry and Mines, Algeria).

The vast majority of SMEs employed between 51 and 200 people, indicating that they play a reasonably substantial role in Algerian employment; a similar conclusion was reached by the Ministry of Industry and Mines (2019). Moreover, while the World Bank’s annual ranking of business climate (Doing Business) places Algeria in a poor position (152nd out of 190 countries for 2020), we believe the government has made significant progress in the areas of entrepreneurship and business creation, taking into account the unique characteristics of the Algerian economy.

According to Table 1, the number of female entrepreneurs in Algeria is still deficient (20 percent). Moreover, Table 1 shows that the bulk of Algerian entrepreneurs polled are pretty old: 66 percent are between the ages of 41 and 50, while only 20% are between 30 and 40. A total of 57 percent of Algerian entrepreneurs questioned have completed vocational training. Algeria has the lowest percentage of people who feel they have the experience and skills to start a business (GEM, 2013).

4.2. Design and Type of Research

As a result, before testing the hypothesis, the procedure was to validate and confirm construct validity.

4.2.1. Measurement Model Assessment (Outer Model)

The outer model, also known as the measurement model, is responsible for evaluating latent variables in PLS Structural Equation Modeling. Each latent construct of the model comprises multiple reflective observations. The model’s latent structures are made up of several thoughtful observations.

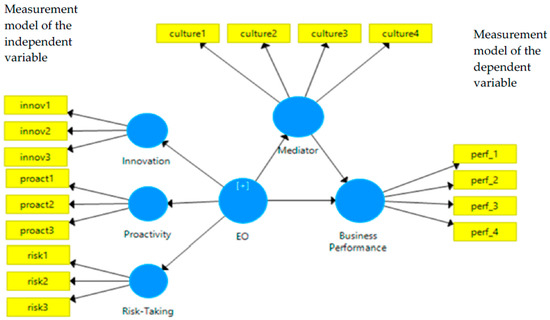

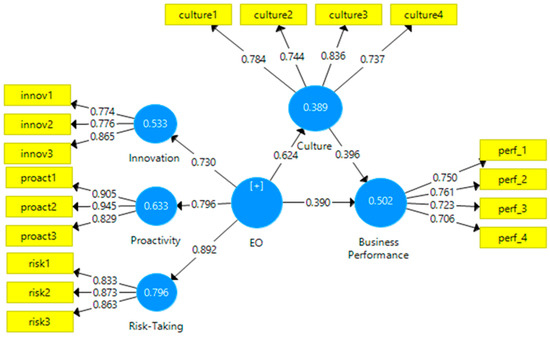

Figure 2 illustrates that EO has the highest effect on the Organizational culture (OC). On the other hand, Entrepreneurial Orientation has a medium impact on BP. In addition, Organizational culture has a moderate effect on BP. Additionally, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Organizational culture together explain 50.2% of the variances for the business performance construct. On the other hand, 38.9% of the variances are described by the entrepreneurial orientation for the Organizational culture construct.

Figure 2.

Research Model.

Figure 2 indicates that all items have a high load and significant on the concepts they intended to measure. As a result, the outer model’s content validity was confirmed.

Figure 3 presents the parameters measured in the model. Composite Reliability [49] is calculated for the constructs in PLS-SEM to ensure reliability. The CR of each construct in this model (see Table 2) is >0.8, sufficient for high-level study. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) value assesses the constructs’ convergent validity. For validating the concepts, AVE value ≥ 0.5 is appropriate. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the sample and Table 3 provides the results of factors loadings and convergent Validity analysis.

Figure 3.

Measurement Model.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

The Results of Factor Loadings and Convergent Validity Analysis.

A set of elements’ ability to distinguish one construct from another is referred to as discriminant validity. According to the authors, the average variances ratings, which should be greater than 0.50, should be examined at this point.

When it comes to assessing validity for reflective items, the Fornell–Larcker approach is more appropriate. The diagonal values indicated that validity tests have a higher value than any other constructs’ correlation. The outputs of Table 4 showed that the discriminant validity is verified.

Table 4.

Discriminant Validity.

4.2.2. Structural Model Results (Inner Model)

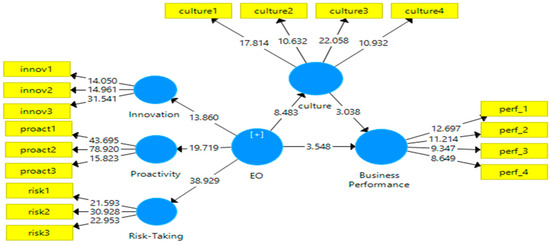

After establishing the measurement model’s validity and reliability, the next phase evaluated the hypothesized correlation using Smart PLS 2.0’s and Bootstrapping algorithms, whose the representation is in the Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The hypothesized correlation.

In Table 5, the PLS-SEM algorithm gives path coefficient or model relationships among the concepts, which describes the hypothesized relationship between the constructs. The path coefficient offers standard values greater than zero, indicating a positive relationship between the constructs, while the t-value or p-value suggests the degree of relationship. EO and Business performance have a path coefficient of 0.390, meaning a positive relationship. So, the outcomes of the study demonstrate the presence of a link between EO and Business performance, which is supported by earlier research [9].

Table 5.

Path coefficient of the research Hypotheses.

Similarly, the path coefficient between OE and Organizational culture is 0.624, which represented positive relation between them. At the same time, Organizational culture has a significant impact on performance (path coefficient = 0.396). The p-value of all the relationships is statistically significant (p < 0.01).

The variance in the dependent variable described by the exogenous latent variable of the model is called the coefficient of determination (R2). The interpretive ranges to be considered are as follows: A value greater than 0.67 is deemed substantial, a moderate explanatory value is in the range 0.66–0.33, and a low value is in the range of 0.32 to 0.19 (see Table 6). The adjusted R2 value helped avoid bias in the complex model where the outcomes deal with many exogenous latent construct data sets. In general, the number of explanatory constructs and the sample size is subtracted from the adjusted R2 value. As a result, while the adjusted R2 cannot be interpreted like R2, it can be used to gain a general understanding of how it delivers outcomes in different setups.

Table 6.

R2 and adjusted R2 of the structural model.

4.2.3. Evaluation of the Overall Model

To ensure the overall validity of our model, we calculated the goodness-of-fit index (GOF), which is a global validation index. It is the geometric mean of the extracted average variance (AVE) and the average R2 of the dependent constructs. This index must be greater than 0.25 to be considered average and more excellent than 0.36 to be considered very large:

After calculation, GoF = 0.5706. The GOF is more significant than 0.36, which means the model’s goodness-of-fit is oversized. Our model is valid and very well fitted.

4.2.4. Mediating Effects Assessment

According to Cuevas-Vargas et al. (2019) [37], the mediator is a component that accounts for all or part of the link between a predictor and a result. We used the approach of Ciampi et al. (2021) [24] to analyze the mediator effect between the variables, which is based on two main steps [24]:

(1) Bootstrap the whole effect (indirect effect);

(2) Bootstrap Confidence Interval (Lower and Upper Level):

a. Bootstrap the whole effect (indirect effect).

From Table 7 and Table 8, we notice that the p values are significant. Therefore, we can evaluate the mediating effect between the variables.

Table 7.

Indirect Effects.

Table 8.

Total Effects.

b. Bootstrap Confidence Interval (Lower and Upper Level)

This is the 95% confidence interval in the “Indirect effect(s) of X on Y because the confidence interval excludes 0 [0.102064; 0.392144] as explained in the Table 9 and Table 10.

Table 9.

Bootstrap Confidence Interval.

Table 10.

Summary of study results.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Our empirical results support previous works [9,17,32,39]. We note that corporate culture plays a mediating role through which EO can influence the performance of Algerian manufacturing SMEs [55].

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Our work attempts to fill this gap, especially in the Algerian context, by suggesting that the OCAI measure’s organizational culture [69] mediates the OE–Performance relationship in Algerian manufacturing SMEs. Moreover, our study offers contributions to advancing knowledge in different streams of literature on the phenomena addressed: entrepreneurial orientation, organizational performance, and organizational culture, and suggests that SMEs can perform through a robust entrepreneurial orientation based on innovation, proactively, and risk-taking within a corporate culture mainly focused on bureaucratic and ad-hocratic culture. In addition, it raises the awareness and visibility of EO, which helps deconstruct any misconceptions. As education is also found as an antecedent of innovative and pro-active EO, entrepreneurship courses could be introduced in formal and informal educational institutes [2]. Scholars have treated EO as a strategic posture reflecting strategy-making practices, management philosophies, and firm-level behaviors that are entrepreneurial in nature [3], which helps university researchers who are looking for an opportunity to lead and implement entrepreneurial projects and thus reinforce the studies on entrepreneurial orientation and culture as valuable constructs to explain organizational performance in a variety of contexts.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our scientific curiosity led us to verify the effect of the OE on the performance of SMEs in the Algerian context. To our knowledge, by reviewing previous studies, this is the first empirical study that tests this issue in this context.

EO can be promoted in the organization through several means. Therefore, Ferreras-Méndez et al. (2022) [3] suggest that decision makers in SMEs should invest time and resources in promoting an entrepreneurial mindset inside their firm’s boundaries if their strategic objective is to reap first-mover advantage benefits [3].

Our work is useful for researchers to understand which empirically based determinants contribute to the performance of SMEs and their sustainability. Through practical entrepreneurial orientation, SME managers can achieve better results. In addition, politicians, decision makers, and economic sector managers can have an idea and orientation on the state of affairs and how to build cooperative and exchange relations in the field of entrepreneurship, especially among manufacturing SMEs. In addition, we note that the present work has underlined that the entrepreneurial orientation presents a decisive factor for companies to have a good performance thanks to a positive organizational culture. This contribution has made a significant advance by pointing out that the organizational culture plays a somewhat important role in the relationship OE–Performance of Algerian manufacturing SMEs. So, the creative industry is a business activity that focuses on creation and innovation [4].

Recently, SMEs are supported several economy since such companies offer usefulness for growth and the employment. In addition, the majority of new jobs opportunities are offered by entrepreneurships [5]

5.3. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

Despite the efforts of the authors, this article has some limitations. The first limitation is the sample size. Future studies should use a bigger sample size to a better understanding of the research phenomena. Second, the generality of our empirical results to other sectors remains uncertain. Using a model that contains some moderators and mediators variables in future research could provide more precise explanations on the relationship between OE and performance. Third, the study only treated entrepreneurial orientation as an independent variable; future researchers could test the relationship of other entrepreneurial variables such as innovation orientation, market orientation, customer orientation, and the overall performance of small and medium enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.A., A.S., M.B. and M.E.A.A.; methodology, Z.A., A.S. and M.B.; formal analysis, Z.A., A.S., M.B. and M.E.A.A.; investigation, Z.A., A.S., M.B. and M.E.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and L.A.; writing—review and editing, L.A., M.B. and C.P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper does not receive any funding from any agency.

Data Availability Statement

The supportive data will be provided on responsible request.

Conflicts of Interest

There is not any conflict of interest between any authors of this paper.

References

- Wacheux, F.; Roussel, P. Management des Ressources Humaines: Méthodes de Recherche en Sciences Humaines et Sociales; De Boeck Education: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mozumdar, L.; Hagelaar, G.; Materia, V.C.; Omta, S.W.F.; Van der Velde, G.; Islam, M.A. Fuelling Entrepreneurial Orientation in Enhancing Business Performance: Women Entrepreneurs’ Contribution to Family Livelihood in a Constrained Context, Bangladesh. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2022, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreras-Méndez, J.L.; Llopis, O.; Alegre, J. Speeding up new product development through entrepreneurial orientation in SMEs: The moderating role of ambidexterity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudjijah, S.; Surachman, S.; Wijayanti, R.; Andarwati, A. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Talent Management on Business Performance of the Creative Industries in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kanaan-Jebna, A.; Baharudi, A.S.; Alabdullah, T.T.Y. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Market Orientation, Managerial Accounting and Manufacturing SMEs Satisfaction. J. Account. Sci. 2022, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, N.; Al-Tabbaa, O. Inter-organizational collaboration and SMEs’ innovation: A systematic review and future research directions. Scand. J. Manag. 2020, 36, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrus, S.; Abdussakir, A.; Djakfar, M. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation and technology orientation on market orientation with education as moderation variable. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, A.; Ahmad, Z.A.B.; Subari, K.A.B.; Asghar, A.R.B.S. Entrepreneurial orientation among Bumiputera small and medium agro-based enterprises (BSMAEs) in West Malaysia: Policy implication in Malaysia. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzomonda, O.; Fatoki, O. Evaluating the impact of organisational culture on the entrepreneurial orientation of small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Bangladesh e-J. Sociol. 2019, 16, 82–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nulkar, G. SMEs and environmental performance—A framework for green business strategies. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 133, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghima, A.; Djema, H. PME et Innovation en Algérie: Limites et Perspectives. Marché Organ. 2014, 1, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Waldinger, R. Ethnicity and entrepreneurship. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1990, 16, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku-Dushi, N.; Dana, L.-P.; Ramadani, V. Entrepreneurial marketing dimensions and SMEs performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Miller (1983) revisited: A reflection on EO research and some suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 873–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostain, M. The impact of organizational culture on entrepreneurial orientation: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2021, 15, e00234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtulmuş, B.E.; Warner, B. Entrepreneurial orientation and perceived financial performance. Does environment always moderate EO performance relation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Floreani, J.; Miani, S.; Beltrame, F.; Cappelletto, R. Understanding the impact of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs’ performance. The role of the financing structure. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basco, R.; Hernández-Perlines, F.; Rodríguez-García, M. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on firm performance: A multigroup analysis comparing China, Mexico, and Spain. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Linares, R.; Kellermanns, F.W.; López-Fernández, M.C.; Sarkar, S. The effect of socioemotional wealth on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and family business performance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Cisneros, M.A.I. Analysis of the moderating effect of entrepreneurial orientation on the influence of social responsibility on the performance of Mexican family companies. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1408209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.N.; Nag, D.; Venkateswarlu, P. A Study on the Relationship of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance in the SMEs of Kurunegala District in Sri Lanka. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2019, 9, 2324–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brettel, M.; Chomik, C.; Flatten, T.C. How organizational culture influences innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking: Fostering entrepreneurial orientation in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.; Demi, S.; Magrini, A.; Marzi, G.; Papa, A. Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on business model innovation: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rigtering, J.P.C.; Hughes, M.; Hosman, V. Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 770–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Ortt, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The mediating role of functional performances. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 878–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Ma, X.; Yu, H. Entrepreneurial orientation, interaction orientation, and innovation performance: A model of moderated mediation. SAGE Open 2019, 9, 2158244019885143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.S.; Liu, H.-H.J.; Ng, Y.-L. Investigation of entrepreneurial orientation development with airline employees: Moderating roles of a cooperation-competition mechanism. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102074. [Google Scholar]

- Arz, C.; Kuckertz, A. Survey data on organizational culture and entrepreneurial orientation in German family firms. Data Brief 2019, 24, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzakiewicz, K.; Cyfert, S. Strategic orientations of the organization-entrepreneurial, market and organizational learning. Management 2019, 23, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamabolo, A.; Rose, E.; Mamabolo, M.A. Transformational leadership as an antecedent and SME performance as a consequence of entrepreneurial orientation in an emerging market context. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Muriithi, R.W.; Kyalo, T.; Kinyanjui, J. Assessment of the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, organisational culture adaptability and performance of Christian faith-based hotels in Kenya. Int. J. Entrep. Knowl. 2019, 7, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kock, A.; Gemünden, H.G. How entrepreneurial orientation can leverage innovation project portfolio management. RD Manag. 2021, 51, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherchem, N. The relationship between organizational culture and entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: Does generational involvement matter? J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2017, 8, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Vargas, H.; Parga-Montoya, N.; Fernández-Escobedo, R. Effects of entrepreneurial orientation on business performance: The mediating role of customer satisfaction—A formative–Reflective model analysis. SAGE Open 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J.A. American institutions and economic progress. J. Inst. Theor. Econ. 1983, 139, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Chang, X.; Kim, R.B. Entrepreneurial orientation and corporate social responsibility performance: An empirical study of state-controlled and privately controlled firms in China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantok, S.; Sekhon, H.; Sahi, G.K.; Jones, P. Entrepreneurial orientation and the mediating role of organisational learning amongst Indian S-SMEs. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 26, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Customer-led and market-oriented: Let’s not confuse the two. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, A. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on Bangladeshi SME performance: Role of organizational culture. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2018, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrizos, S.; Apospori, E.; Carrigan, M.; Jones, R. Is CSR the panacea for SMEs? A study of socially responsible SMEs during economic crisis. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Genc, E.; Dayan, M.; Genc, O.F. The impact of SME internationalization on innovation: The mediating role of market and entrepreneurial orientation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkanyou, B.B.; St-Jean, E.; LeBel, L. Cahier de Recherche; Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières: Quebec, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, G.N.; Hanks, S.H. Measuring the performance of emerging businesses: A validation study. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Bell, R.G.; Payne, G.T.; Kreiser, P.M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Managerial Power. Am. J. Bus. 2010, 25, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, J.P.; Bhattacharyya, S. Measuring organizational performance and organizational excellence of SMEs—Part 2: An empirical study on SMEs in India. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2010, 14, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrani, W.A.; Mahmood, R. Organizational Culture as Potential Moderator on the Relationship between Corporate Entrepreneurship and Business Performance: A Proposed Framework. J. Stud. Manag. Plan. 2015, 1, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Żur, A. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: Challenges for research and practice. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2013, 1, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F. Management control systems and strategy: A resource-based perspective. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 529–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidor, A.; Gelmereanu, C.; Baru, P.; Morar, L. Diagnosing organizational culture for SME performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 3, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Latifi, M.-A.; Nikou, S.; Bouwman, H. Business model innovation and firm performance: Exploring causal mechanisms in SMEs. Technovation 2021, 107, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Robinson, R.B., Jr. Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, H. La gestion stratégique et les mesures de la performance non financière des PME. In Proceedings of the 6° Congrès International Francophone sur la PME, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and organizations: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. In Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhoraif, A.; McLaughlin, P. Lean implementation within manufacturing SMEs in Saudi Arabia: Organizational culture aspects. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2018, 30, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eniola, A.A.; Olorunleke, G.K.; Akintimehin, O.O.; Ojeka, J.D.; Oyetunji, B. The impact of organizational culture on total quality management in SMEs in Nigeria. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umrani, W.; Kura, K.; Ahmed, U. Corporate entrepreneurship and business performance: The moderating role of organizational culture in selected banks in Pakistan. PSU Res. Rev. 2018, 2, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; Jossey-Bass Business & Management Series; Jossey Bass Incorporated: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. How Can Organizations Learn Faster?: The Problem of Entering the Green Room; MIT Sloan School of Management: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Barbars, L.D.A.; Dubkēvičs, L. The role of organizational culture in human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Ergon. 2010, 4, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Engelen, A.; Flatten, T.C.; Thalmann, J.; Brettel, M. The effect of organizational culture on entrepreneurial orientation: A comparison between Germany and Thailand. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2014, 52, 732–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardcopf, R.; Liu, G.J.; Shah, R. Lean production and operational performance: The influence of organizational culture. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Übius, Ü.; Alas, R. Organizational culture types as predictors of corporate social responsibility. Eng. Econ. 2009, 61, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Isensee, C.; Teuteberg, F.; Griese, K.M.; Topi, C. The relationship between organizational culture, sustainability, and digitalization in SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, S.; Zaheer, A. Trust across borders. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Haider, S.; Sajjad, M. Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosario, R.-S.M.; René, D.-P. Eco-innovation and organizational culture in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Nakara, W.A.; Gharbi, S.; Bahri, C. The relationship between organizational culture and small-firm performance: Entrepreneurial orientation as mediator. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, K.; Quinn, R. Diagnosing and Changing Culture Organizational Based on the Competing Values Framework; John Willey & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kashan, A.J.; Wiewiora, A.; Mohannak, K. Unpacking organisational culture for innovation in Australian mining industry. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Tang, Z.; Marino, L.D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q. Exploring an inverted U–shape relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance in Chinese ventures. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, M.S.; Rogo, H.B.; Mahmood, R. Knowledge management, entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of organizational culture. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; da Silva, D.; de Souza Bido, D. Structural Equation Modeling with the Smartpls. Rev. Bras. Mark. 2014, 13, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).