Abstract

The incidence of multiple myeloma is higher in males. The underlying mechanisms may be related to differences in immune system orchestration in males and females. LAG3 and CTLA4 are immune checkpoint proteins and inhibitory regulators of T cells. Here, we analyzed the prevalence of the common LAG3 gene variant rs870849 and the common CTLA4 gene variant rs231775 in myeloma patients eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation. CTLA4 rs231775 was prevalent at normal allele frequencies. In contrast, LAG3 rs870849 was prevalent at elevated allele frequencies in myeloma patients, with allele frequency 0.61 in male and 0.53 in female patients compared to 0.39 in the European population. The gene risk analysis of rs870849 indicated an odds ratio 6.8 in male and 3.6 in female patients. Moreover, treatment outcomes differed in the three genetic LAG3 subgroups with median progression-free survival of 2.6, 3.3 and 3.4 and median overall survival of 7, 15 and 18 years in the I455hom, I455Thet and T455hom subgroups, respectively. LAG3 rs870849 may affect survival and treatment outcome after autologous stem cell transplantation in myeloma patients with favorable outcomes in rs870849 carriers.

1. Introduction

The incidence of hematological malignancies increases significantly with age and the incidence rates are generally higher in men than women [1]. Male predominance is thought to be due to a combination of factors, including environmental exposures and hormonal and immune system differences [2,3]. Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell malignancy characterized by clonal proliferation of terminally differentiated B cells in the bone marrow, leading to monoclonal protein production, bone destruction and immunodeficiency [4]. Despite major therapeutic advances MM remains largely incurable [5]. Treatment resistance has been linked to clonal evolution and support from the immunosuppressive bone marrow microenvironment [6,7].

Extensive real-world cohorts have confirmed heterogeneous outcomes and poor long-term survival in some transplant-eligible MM patients, emphasizing the need for improved risk stratification and molecularly guided therapies [8,9]. Within the bone marrow microenvironment, malignant plasma cells create conditions that impair antitumor immunity through effector T cell exhaustion and expansion of regulatory T cells [7]. Several immune checkpoint molecules—such as programmed death-1 (PD-1), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4, CD152) and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG3, CD223)—play central roles in orchestrating these immune interactions [10]. Among them, LAG3 has emerged as a key regulator of T cell exhaustion and a promising target in next-generation tumor immunotherapy [10,11].

The LAG3 gene, located on chromosome 12p13.31, encodes a type I transmembrane protein expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells and dendritic cells [11]. LAG3 binds to major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and to fibrinogen-like protein 1 (FGL1), transmitting inhibitory signals that reduce T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion [12]. Overexpression of LAG3 on T cells has been observed in patients with MM and correlates with disease activity and diminished immune surveillance [13,14]. In preclinical models, LAG3 blockade restores T cell cytotoxicity and enhances anti-myeloma responses, particularly when combined with PD-1 inhibition [15]. These findings suggest that LAG3 contributes to T cell exhaustion and disease progression in MM [13,15].

LAG3 gene variants may have differential impact on immune checkpoint signaling. LAG3 gene single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can alter transcription, splicing and receptor conformation, thereby modifying immune tolerance thresholds [16]. The common germline missense variant rs870849 (C>T; I455T) and the intron variant rs2365095 (A>G) have been linked to immune dysregulation and variable disease susceptibility [17]. Genetic polymorphisms in immune-regulatory genes such as CD19, CTLA4 and LAG3 have been reported to affect treatment response in hematological malignancies treated with CAR-T cell therapy [18,19,20]. These findings indicate that germline variation in immune-related genes may affect immune modulation and therapy responses. Donor LAG3 rs870849 genotypes have been linked to adverse outcomes following allogeneic stem cell transplantation, while other LAG3 polymorphisms have been associated with altered immune recovery in bone marrow failure syndromes [16,17]. LAG3 acts in concert with other inhibitory receptors—including PD-1, TIM-3 and TIGIT—to form co-inhibitory networks that tightly regulate immune activation and tolerance, as reviewed in [21,22]. In this context, germline LAG3 variation may represent a stable genetic factor predisposing to inadequate immune surveillance and tumor persistence. The broad clinical application of combined PD-1/LAG3 blockade underscores the translational relevance of this pathway [23]. Understanding the genetic landscape of LAG3 polymorphisms may thus provide novel insights into MM pathogenesis and support the development of individualized immunotherapeutic strategies.

In this study, we analyzed the potential gene risk of the common LAG3 gene variant rs870849 in the emergence of MM and differences in treatment efficacies depending on the LAG3 genetic background. By genotyping well-defined patient and control cohorts and correlating allelic variants with clinical parameters, we aimed to clarify the contribution of LAG3 genetic variation to MM susceptibility and treatment response. Identification of risk-associated LAG3 variants may elucidate disease mechanisms and improve personalized immunotherapy strategies in MM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Sequence and Risk Analysis

The CTLA4 and LAG3 genes were analyzed by Sanger sequencing as previously described [18,19]. Gene risk was analyzed on a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium calculator [24].

2.2. Clinical Data

We conducted a retrospective single-center study at the Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, Switzerland. The patient cohort comprised 171 patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma in the two decades from July 2003 to June 2022. All 171 patients received induction therapy, 156 patients received HDCT/ASCT. The study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Commission of the Canton of Bern (decision number 2025-00853, date of approval 24 April 2025). All patients signed a written informed consent form. Clinical Data were analyzed as previously described [25].

3. Results

3.1. Elevated Allele Frequency of LAG3 rs870849 in Patients with Multiple Myeloma

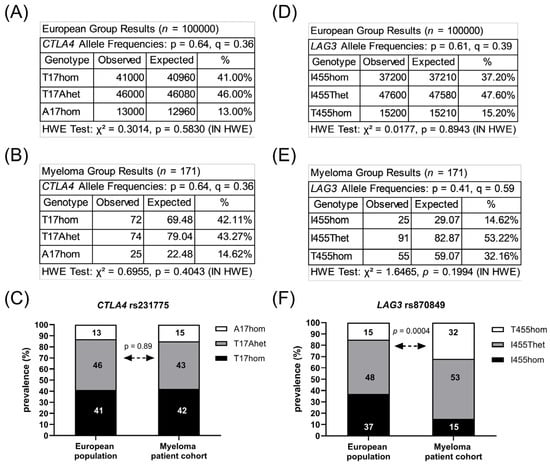

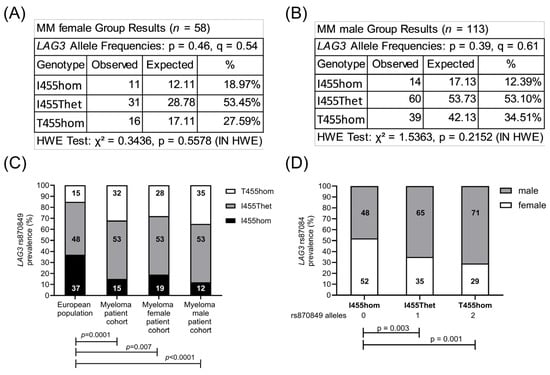

The sequence of the CTLA4 gene exon one and the LAG3 gene exon seven were determined in the peripheral blood cells of 171 MM patients. In total, 72 patients (42%) carried two major CTLA4 alleles encoding CTLA4 T17 (T17hom), 74 patients (43%) had one allele rs231775 (T17Ahet) and 23 patients (14%) carried two alleles rs231775 (A17hom). Further, 25 patients (15%) carried two major LAG3 alleles encoding LAG3 I455 (I455hom), 91 patients (53%) had one allele rs870849 (I455Thet) and 55 patients (32%) carried two alleles rs870849 (T455hom). Allele frequencies and genetic risks were analyzed for the MM cohort on a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium calculator [24], compared to allele frequencies in the European population with CTLA4 rs231775 and LAG3 rs870849 allele frequencies of 0.36 and 0.39, respectively (ALFA sample size 588,090, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/, access date 22 August 2025). The observed CTLA4 rs231775 allele frequency 0.36 in the MM group was identical to the European control group (Figure 1A–C), while the LAG3 rs870849 allele frequency 0.59 was significantly higher in the MM group than in the European control group with rs870849 allele frequency 0.39 (Figure 1D–F). The MM cohort consisted of 110 (64%) males and 61 (36%) females, an m/f ratio of 1.8 (Table 1). The LAG3 rs870849 allele frequency was 0.54 in MM female and 0.61 in MM male groups (Figure 2A,B). Males predominated within the T455hom group with m/f ratio of 2.24 (71% males), while the m/f ratio was 1.84 (65% males) in the I455Thet and 0.93 (48% males) in the I455hom group, respectively (Figure 2C,D).

3.2. Gene Risk Analysis

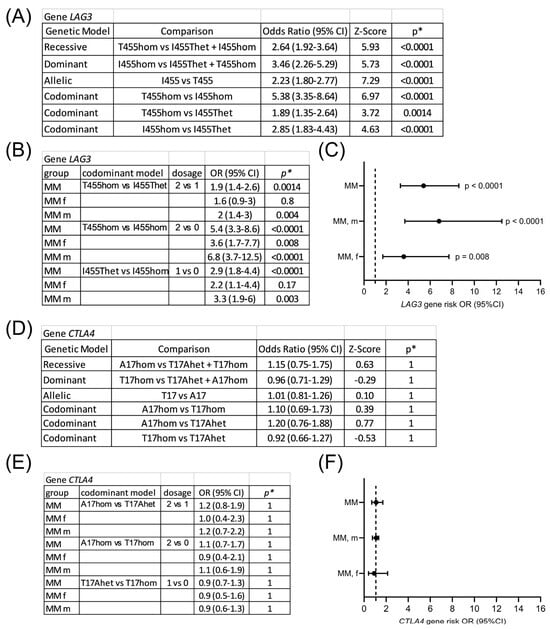

Gene risk associated with LAG3 rs870849 and CTLA4 rs231775 variants was analyzed on Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium calculator in different genetic models including dominant, codominant and recessive [24]. In all genetic models LAG3 rs870849 was significantly associated with risk for multiple myeloma (Figure 3A). LAG3 protein variants may form heterodimers and all combinatorial effects are possible including dominant, codominant and recessive dimer function. The gene risk associated with LAG3 rs870849 4 in the codominant model was dose-dependent with OR 5.4 at dosage 2 vs. 0, OR 2.9 at dosage 1 vs. 0 and OR 1.9 at dosage 2 vs. 1 (Figure 3B). In the stratified analysis male-specific risk was higher with OR 6.8 compared to female-specific risk OR 3.6 (Figure 3C). In contrast, CTLA4 rs231775 was not associated with risk for MM with an OR of 1.1, with male-specific OR 1.1 and female-specific OR 0.9 (Figure 3D–F).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of CTLA4 rs231775 and LAG3 rs870849. Allele frequencies of CTLA4 rs231775 in the European population (A) and in the local MM cohort (B). Prevalence of CTLA4 rs231775 in the local MM cohort compared to the European population (C). Allele frequencies of LAG3 rs870489 in the European population (D) and in the local MM cohort (E). Prevalence of LAG3 rs870849 in the local MM cohort compared to the European population (F). HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. p: major allele, q: minor allele.

Figure 2.

Male predominance of LAG3 rs870849 in the MM cohort. Allele frequencies were analyzed according to the LAG3 genetic variants in the MM female (A) and MM male (B) subgroups. Prevalence of LAG3 rs870849 in the MM subgroups compared to the European population (C) and gender distribution in the LAG3 genetic subgroups of myeloma patients (D). HWE: Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. p: major allele, q: minor allele.

Figure 3.

Gene risk associated with LAG3 rs870849 and CTLA4 rs231775 in multiple myeloma. LAG3 gene risk analysis in different genetic models (A) and in codominant models, stratified for males and females (B). Forest plot of gene risk associated with LAG3 T455hom vs. I455hom (C). CTLA4 gene risk analysis (D,E). Forest plot of gene risk associated with CTLA4 A17hom vs. T17hom (F). OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. * p values with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (α = 0.05/7 = 0.00714).

3.3. Clinical Characteristics in the Myeloma Cohort According to LAG3 rs870849

The MM cohort comprised 171 patients diagnosed with MM at a median age of 60 years, including 110 males and 61 females, indicating a sex ratio (m/f) of 1.8. Baseline clinical characteristics were analyzed for the entire cohort and for the three genetic subgroups with LAG3 rs870849 encoding isoleucine or threonine at the amino acid position of the LAG-3 protein (LAG3 I455hom, I455Thet, T455hom) (Table 1). The majority of patients were characterized by male gender, ISS II, standard cytogenetic risk, paraprotein types IgG and light chain kappa, normal hemoglobin, calcium and LDH levels, elevated beta-2-microglobulin levels, as well as high bone marrow infiltration rates. Half of the patients were anemic (Hb < 110 g/L) and had decreased serum albumin levels, with renal dysfunction observed in 40% of the patients. The clinical characteristics were comparable in the three genetic subgroups with the exception of the median age at diagnosis and the sex ratio; the median age at the time of initial diagnosis was 56 years in the I455hom and 60 years in the I455Thet and T455hom subgroups (p = 0.07). Male predominance was elevated in the T455hom subgroup with a sex ratio (m/f) of 2.44 (p = 0.02) and reduced in the I455hom subgroup with a sex ratio (m/f) of 0.92. Paraprotein composition differed in the three genetic subgroups: while IgG paraprotein prevailed in the I455hom and I455Thet subgroups (p = 0.03), the T455hom subgroup had the highest proportion of light chain only paraprotein (p = 0.05) and renal dysfunction (p = 0.04). Anemia and hypercalcemia prevailed in the LAG3 r2870849 carriers (T455hom and I455Thet).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics according to LAG3 genotype.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics according to LAG3 genotype.

| All Patients (N = 171) | I455hom (N = 25) | I455Thet (N = 91) | T455hom (N = 55) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio (m/f) | 1.8 | 0.92 | 1.84 | 2.44 | 0.02 |

| Female, n (%) | 61 (36%) | 13 (52%) | 32 (35%) | 16 (29%) | 0.14 |

| Male, n (%) | 110 (64%) | 12 (48%) | 59 (65%) | 39 (71%) | |

| Age at ID, median (range) | 60 (33–78) | 56 (42–73) | 60 (39–78) | 60 (33–74) | 0.07 |

| Initial disease stage (ISS) | N = 159 | N = 23 | N = 85 | N = 51 | 0.59 |

| I | 50 (31%) | 9 (39%) | 25 (30%) | 16 (31%) | 0.67 |

| II | 59 (38%) | 10 (44%) | 30 (35%) | 19 (38%) | 0.74 |

| III | 50 (31%) | 4 (17%) | 30 (35%) | 16 (31%) | 0.19 |

| Cytogenetic risk category | N = 120 | N = 18 | N = 62 | N = 40 | 0.36 |

| high risk * | 34 (28%) | 6 (33%) | 20 (32%) | 8 (20%) | |

| standard risk | 86 (72%) | 12 (67%) | 42 (68%) | 32 (80%) | |

| Cytogenetic aberrations | N = 120 | N = 18 | N = 62 | N = 40 | 0.85 |

| −13 | 34 (28%) | 6 (33%) | 21 (34%) | 7 (18%) | 0.17 |

| −14 | 8 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 3 (8%) | 0.99 |

| −16 | 5 (4%) | 2 (11%) | 3 (5%) | 0 | 0.11 |

| +1 q | 41 (34%) | 8 (44%) | 19 (31%) | 14 (35%) | 0.54 |

| del17p * | 13 (11%) | 1 (6%) | 8 (13%) | 4 (10%) | 0.78 |

| t(4;14) * | 19 (16%) | 3 (17%) | 12 (19%) | 4 (10%) | 0.48 |

| t(14;16) * | 8 (7%) | 2 (11%) | 5 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0.31 |

| t(11;14) | 27 (23%) | 3 (17%) | 16 (26%) | 8 (20%) | 0.72 |

| Paraprotein-type | 0.18 | ||||

| Heavy chain IgG | 111 (65%) | 19 (76%) | 64 (70%) | 28 (51%) | 0.03 |

| Heavy chain IgA | 33 (19%) | 4 (16%) | 16 (17%) | 13 (24%) | 0.64 |

| Light chain only | 26 (15%) | 2 (8%) | 10 (12%) | 14 (25%) | 0.05 |

| Light chain kappa | 112 (66%) | 15 (60%) | 60 (66%) | 37 (67%) | 0.86 |

| Light chain lambda | 59 (34%) | 10 (40%) | 31 (34%) | 18 (33%) | 0.86 |

| Anemia | N = 143 | N = 23 | N = 75 | N = 45 | |

| Hb (g/L), median (range) | 109 (46–167) | 114 (70–148) | 109 (46–164) | 106 (71–167) | 0.87 |

| Hb < 110 g/L, n (%) | 72 (51%) | 8 (35%) | 38 (51%) | 26 (58%) | 0.21 |

| Hypercalcemia | N = 117 | N = 18 | N = 62 | N = 37 | |

| Ca (mmol/L), median (range) | 2.42 (1.4–4.2) | 2.35 (2.1–2.8) | 2.45 (1.4–4.2) | 2.43 (2.1–4.2) | 0.13 |

| >2.6 mmol/L, n (%) | 24 (21%) | 1 (6%) | 14 (23%) | 9 (24%) | 0.24 |

| Beta-2-microglobulin | N = 143 | N = 23 | N = 74 | N = 46 | |

| B2M (mg/L), median (range) | 3.3 (1.18–38) | 3.2 (1.8–7.3) | 3.4 (1.18–30) | 3.1 (1.51–38) | 0.77 |

| >2.2 mg/L, n (%) | 104 (73%) | 20 (87%) | 54 (73%) | 30 (65%) | 0.16 |

| Lactate-dehydrogenase | N = 103 | N = 21 | N = 49 | N = 33 | |

| LDH (U/L), median (range) | 274 (110–1366) | 272 (162–644) | 276 (110–1366) | 259 (145–526) | 0.46 |

| >480 U/L, n (%) | 11 (11%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (10%) | 4 (12%) | 0.99 |

| Serum albumin | N = 133 | N = 22 | N = 70 | N = 41 | |

| g/dL, median (range) | 3.6 (1.8–29) | 3.6 (1.8–8) | 3.4 (1.8–29) | 3.6 (2.5–5) | 0.45 |

| <3.5 g/dL, n (%) | 62 (47%) | 7 (32%) | 35 (50%) | 14 (34%) | 0.16 |

| Bone marrow infiltration | N = 167 | N = 25 | N = 89 | N = 53 | |

| Percent, median (range) | 60 (3–100) | 60 (10–90) | 70 (5–100) | 55 (3–100) | 0.37 |

| 40–100%, n (%) | 122 (73%) | 19 (76%) | 68 (76%) | 35 (66%) | 0.39 |

| Osteolytic lesions | 122 (74%) | 16 (67%) | 65 (73%) | 41 (79%) | 0.52 |

| Renal dysfunction | 51 (40%) | 6 (33%) | 26 (37%) | 20 (50%) | 0.04 |

ISS: international staging system; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase. * High risk cytogenetics include del17p, t(4;14), t(14;16).

3.4. Clinical Response to HDCT/ASCT According to LAG3 rs870849

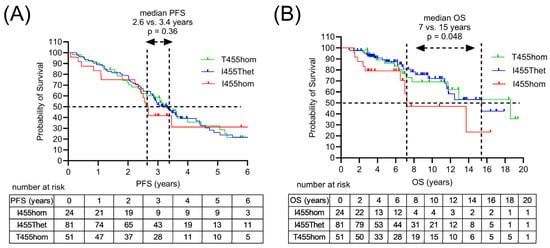

All 171 patients diagnosed with MM received induction therapy, consisting of proteaseome inhibitor bortezomib (velcade) and dexamethasone in combination with lenalidomide (revlimid) or cyclophosphamide (Table 2). More recently, the monoclonal antibody daratumumab was added to induction therapy (Dara-VRD). Clinical response to induction therapy included 11–13% complete response (CR) and 58–62% partial response (PR) in the I455Thet and T455hom subgroups, with 88% PR in the I455hom subgroup. Relapsed patients were treated with immuno-chemotherapy (ICT). Patients with multiple relapses received multiple ICT lines. A total of 156 patients received high-dose chemo-therapy (HDCT) followed by autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). Clinical responses to HDCT/ASCT differed in the three genetic subgroups with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 2.6, 3.3 and 3.4 years and a median overall survival (OS) of 7, 15 and 18 years in the I455hom, I455Thet and T455hom subgroups, respectively (Figure 4). In the multivariate analysis, the LAG3 variant was not associated with survival outcome, with initial disease stage, high risk cytogenetics and age as confounding predictors (Table 3).

Table 2.

Therapy response according to LAG3 genotype.

Figure 4.

Survival outcomes of MM patients following HDCT/ASCT according to the LAG3 genotype. (A) Progression-free survival (PFS) according to LAG3 gene polymorphism rs870849 encoding LAG3 I455hom, I455Thet or T455hom. (B) Overall survival (OS) in the genetic subgroups LAG3 I455hom, I455Thet and T455hom.

Table 3.

Clinical outcome hazard ratios (HR), multivariate analysis.

4. Discussion

Risk factors for MM include age, sex and ethnicity. The median age at initial diagnosis of MM is 70 years. Men are more likely to develop MM than women. The incidence of MM is higher in people of African descent than in Caucasians. In our analysis of a European MM patient cohort, we defined a male-predominant risk allele for MM, a common human LAG3 germline variant. LAG3 rs870849 was prevalent at elevated allele frequencies in MM patients eligible for ASCT, with MAF 0.61 in male and MAF 0.53 in female MM patients compared to MAF 0.39 in the general European population, and MAF 0.45 in the African and African American population. In all genetic models, LAG3 rs870849 was a significant risk allele, in the codominant model at gene dosage 2 vs. 0 with an OR of 5.4, stratified into male-specific OR 6.8 and female-specific OR 3.6.

Sex-specific risk loci have been defined for other medical conditions with sex-specific differences in prevalence including asthma, coronary artery disease and colorectal cancer [26,27,28]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified common risk alleles for MM at 24 independent loci [29]. Other germline risk alleles may contribute to genomic instability and MM [30]. Risk alleles for MM were also defined in genes related to activation, detoxification and clearance of chemical carcinogens [31]. LAG3 rs870849 on 12p13 may be a significant male-predominant myeloma risk allele, possibly with a bias toward light chain myeloma with renal dysfunction.

LAG3 rs870849 was previously studied in DLBCL patients treated with CAR-T cell therapy where it was present at elevated frequencies and implicated in favorable treatment outcome [19]. In the current study the germline allele LAG3 rs870849 was detected at elevated frequencies in MM patients eligible for HDCT/ASCT and associated with favorable treatment outcome. The effects of LAG3 rs870849 were dose-dependent, indicating functional differences in the LAG3 protein variants due to the substitution of isoleucine to threonine in the LAG3 transmembrane domain (I455T). The molecular mechanisms underlying the opposing traits of promoting and impeding the same disease may be related to the appropriate balance of T cell activity and T cell exhaustion [32,33,34]. In the promotion of myeloma development, LAG3 rs870849 may increase the number of exhausted T cells with concomitant loss of immune surveillance. In stem cell-based therapy LAG3 rs870849 may promote T cell activity against myeloma cells.

Limitations of the study include the cohort size and composition with a large majority of patients who underwent HDCT/ASCT (90%). The LAG3 rs870849 allele frequencies were found to be elevated in MM patients eligible for ASCT but may be lower in MM patients not eligible for ASCT. This may represent a survivorship bias with the implication that LAG3 rs870849 may confer a survival advantage. Most patients diagnosed with MM are at an advanced age and eligibility for HDCT/ASCT has been limited. Traditionally, a cutoff of 65 years was implemented, but this is shifting to 75 years, with recent data showing improved outcomes for older patients undergoing ASCT [35]. However, the commonly applied induction therapy may impair the stem cells in MM patients leading to a reduced reconstitution potential after ASCT [36]. In stem cell-based therapies LAG3 rs870849 may promote stem cell function and reconstitution potential. The molecular mechanisms involving different LAG3 variants remain to be established in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization K.S. and T.P.; formal analysis, K.S., A.M., P.H. and I.S.; investigation K.S., A.M. and P.H.; resources, M.H. and U.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and T.P.; visualization, K.S.; project administration, T.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Commission of the Canton of Bern (decision number 2025-00853, date of approval 24 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the entire team involved in patient care at the University Hospital Bern, Switzerland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

Multiple myeloma (MM), Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT), autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), minor allele frequency (MAF).

References

- Mafra, A.; Laversanne, M.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Chaves, H.V.S.; Mcshane, C.; Bray, F.; Znaor, A. The Global Multiple Myeloma Incidence and Mortality Burden in 2022 and Predictions for 2045. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2025, 117, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarian, M.A.; Fatahichegeni, M.; Ren, J.; Wang, X. Sex and Gender in Myeloid and Lymphoblastic Leukemias and Multiple Myeloma: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Outcomes. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulou, R.; Fiste, O.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Andrikopoulou, A.; Zagouri, F.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Kastritis, E.; Terpos, E.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Occupational Exposure and Multiple Myeloma Risk: An Updated Review of Meta-Analyses. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, S.V. Multiple Myeloma: 2020 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-Stratification and Management. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, S.V.; Kumar, S. Multiple Myeloma Current Treatment Algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.; Caetano, J.; Ferreira, B.; Barahona, F.; Carneiro, E.A.; João, C. The Immune Microenvironment in Multiple Myeloma: Friend or Foe? Cancers 2021, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visram, A.; Dasari, S.; Anderson, E.; Kumar, S.; Kourelis, T.V. Relapsed Multiple Myeloma Demonstrates Distinct Patterns of Immune Microenvironment and Malignant Cell-Mediated Immunosuppression. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kündgen, L.J.; Akhoundova, D.; Hoffmann, M.; Legros, M.; Shaforostova, I.; Seipel, K.; Bacher, U.; Pabst, T. Prognostic Value of Post-Transplant MRD Negativity in Standard Versus High- and Ultra-High-Risk Multiple Myeloma Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechbühl, S.; Bacher, U.; Jeker, B.; Pabst, T. Real-World Outcome in the Pre-CAR-T Era of Myeloma Patients Qualifying for CAR-T Cell Therapy. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 13, e2021012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L.P.; Marciscano, A.E.; Drake, C.G.; Vignali, D.A.A. LAG3 (CD223) as a Cancer Immunotherapy Target. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 276, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruhashi, T.; Sugiura, D.; Okazaki, I.-M.; Okazaki, T. LAG-3: From Molecular Functions to Clinical Applications. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Datar, I.; Su, T.T.; Ji, L.; Sun, J.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, G.; Yin, W.; et al. Fibrinogen-like Protein 1 Is a Major Immune Inhibitory Ligand of LAG-3. Cell 2019, 176, 334–347.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkovic, S.; Purton, L.E.; Harrison, S.J.; Quach, H. Multiplex Immunohistochemistry Elucidates Increased Distance between Cytotoxic T Cells and Plasma Cells in Relapsed Myeloma, and Identifies Lag-3 as the Most Common Checkpoint Receptor on Cytotoxic T Cells of Myeloma Patients. Haematologica 2024, 109, 1487–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q. PD-1 and LAG-3-Positive T Cells Are Associated with Clinical Outcomes of Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma Patients. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, C.; Perez, C.; Larrayoz, M.; Puig, N.; Cedena, M.-T.; Termini, R.; Goicoechea, I.; Rodriguez, S.; Zabaleta, A.; Lopez, A.; et al. Large T Cell Clones Expressing Immune Checkpoints Increase During Multiple Myeloma Evolution and Predict Treatment Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, D.; Rodríguez-Romanos, R.; González-Bartulos, M.; García-Cadenas, I.; de la Cámara, R.; Heras, I.; Buño, I.; Santos, N.; Lloveras, N.; Velarde, P.; et al. LAG3 Genotype of the Donor and Clinical Outcome after Allogeneic Transplantation from HLA-Identical Sibling Donors. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1066393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Liu, C.; Shao, Z. Lymphocyte Activation Gene 3 Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Bone Marrow Failure Diseases. Anal. Cell Pathol. 2022, 2022, 3528598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, K.; Shaforostova, I.; Nilius, H.; Bacher, U.; Pabst, T. Clinical Impact of CTLA-4 Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism in DLBCL Patients Treated with CAR-T Cell Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, K.; Spahr, S.M.; Shaforostova, I.; Bacher, U.; Nilius, H.; Pabst, T. Clinical Impact of LAG3 Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism in DLBCL Treated with CAR-T Cell Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, K.; Abbühl, M.; Bacher, U.; Nilius, H.; Daskalakis, M.; Pabst, T. Clinical Impact of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism in CD-19 on Treatment Outcome in FMC63-CAR-T Cell Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Li, Y.; Tan, J.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Targeting LAG-3, TIM-3, and TIGIT for Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 101, Erratum in J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 105. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-023-01503-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.C.; Joller, N.; Kuchroo, V.K. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-Inhibitory Receptors with Specialized Functions in Immune Regulation. Immunity 2016, 44, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawbi, H.A.; Schadendorf, D.; Lipson, E.J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Matamala, L.; Castillo Gutiérrez, E.; Rutkowski, P.; Gogas, H.J.; Lao, C.D.; De Menezes, J.J.; et al. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudershan, A.; Singh, K.; Kumar, P. GeneRiskCalc: A Web-Based Tool for Genetic Risk Association Analysis in Case–Control Studies. BMC Bioinform. 2025, 26, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, K.; Veglio, N.Z.; Nilius, H.; Jeker, B.; Bacher, U.; Pabst, T. Rising Prevalence of Low-Frequency PPM1D Gene Mutations after Second HDCT in Multiple Myeloma. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 8197–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dungan, J.R.; Qin, X.; Gregory, S.G.; Cooper-Dehoff, R.; Duarte, J.D.; Qin, H.; Gulati, M.; Taylor, J.Y.; Pepine, C.J.; Hauser, E.R.; et al. Sex-Dimorphic Gene Effects on Survival Outcomes in People with Coronary Artery Disease. Am. Heart J. Plus 2022, 17, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.; Himes, B. Gene-Based Analysis Reveals Sex-Specific Genetic Risk Factors of COPD. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2021, 2021, 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.L.; Plummer, S.J.; Acheson, L.S.; Tucker, T.C.; Casey, G.; Li, L. Association of Common Genetic Variants in SMAD7 and Risk of Colon Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertesi, M.; Went, M.; Hansson, M.; Hemminki, K.; Houlston, R.S.; Nilsson, B. Genetic Predisposition for Multiple Myeloma. Leukemia 2020, 34, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, S.; Zhan, F.; Sun, F.; Cheng, Y.; Pisano, M.; Yang, Y.; Goldschmidt, H.; Hari, P. Germline Risk Contribution to Genomic Instability in Multiple Myeloma. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scionti, F.; Agapito, G.; Caracciolo, D.; Riillo, C.; Grillone, K.; Cannataro, M.; Di Martino, M.T.; Tagliaferri, P.; Tassone, P.; Arbitrio, M. Risk Alleles for Multiple Myeloma Susceptibility in ADME Genes. Cells 2022, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Liu, K.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Ma, W.; Xu, W.; Wu, J.; Sun, C. Tumor Accomplice: T Cell Exhaustion Induced by Chronic Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 979116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelle-Rieser, C.; Thangavadivel, S.; Biedermann, R.; Brunner, A.; Stoitzner, P.; Willenbacher, E.; Greil, R.; Jöhrer, K. T Cells in Multiple Myeloma Display Features of Exhaustion and Senescence at the Tumor Site. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, D.J.; Pronschinske, K.B.; Shyer, J.A.; Sharma, S.; Leung, S.; Curran, S.A.; Lesokhin, A.M.; Devlin, S.M.; Giralt, S.A.; Young, J.W. T-Cell Exhaustion in Multiple Myeloma Relapse after Autotransplant: Optimal Timing of Immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stettler, J.; Novak, U.; Baerlocher, G.M.; Seipel, K.; Mansouri Taleghani, B.; Pabst, T. Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in Elderly Patients with Multiple Myeloma: Evaluation of Its Safety and Efficacy. Leuk. Lymphoma 2017, 58, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumhardt, T.M.; Amoah, A.; Hoenicka, M.; Liebold, A.; Sakk, V.; Soller, K.; Vollmer, A.; Kull, M.; Kronke, J.; Mallm, J.-P.; et al. Functional and Molecular Analyses Reveal Impaired HSPCs in Multiple Myeloma Patients Post-Induction. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2025, 14, szaf061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.