Abstract

Sucrose is a key quality trait in peanuts, yet high-sucrose varieties are scarce. Although sucrose transporters (SUT/SUC) play crucial roles in sucrose transport and accumulation during seed development, systematic analyses in peanuts are limited. This study conducted a genome-wide analysis of the SUC gene family in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Sixteen AhSUC genes were identified and characterized for genomic distribution, phylogeny, and expression across tissues and developmental stages. The genes are unevenly distributed across the genome with clustered chromosomal localization. All AhSUC proteins contain the conserved sucrose/proton co-transporter domain (IPR005989), exhibit the typical 12 transmembrane α-helical structure of the major facilitator superfamily, are hydrophobic, and predicted to localize to the membrane. Promoter analysis revealed cis-regulatory elements associated with growth, development, light, hormone, and stress responses. Expression profiling showed tissue-specific patterns, with eight AhSUC genes being highly expressed in cotyledons and embryos. Comparative analysis between high-sugar and conventional varieties showed higher expression of AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 in the high-sugar variety, correlating with increased sucrose accumulation. Functional validation using a sucrose transport-deficient yeast mutant confirmed the sucrose transport activity of these genes. These findings provide insight into sucrose accumulation mechanisms and offer genetic targets for breeding high-sugar peanut varieties.

1. Introduction

The cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), commonly known as the “longevity nut” and also referred to as groundnut or earthnut, is an allopolyploid legume crop. It originated in the Andes Mountains of South America and can be traced back to the wild diploid ancestors, Arachis duranensis (AA genome) and Arachis ipaensis (BB genome), and was formed through hybridization and domestication [1,2,3]. Not only is it rich in protein resources [4], but it is also a major oilseed crop [5]. Based on their morphology and growth habits, groundnuts (A. hypogaea L.) are classified into two subspecies, A. hypogaea ssp. hypogaea and A. hypogaea ssp. fastigiata, and six varieties [1,3,4]. Peanuts cultivated worldwide today are primarily oil crops, and peanut oil is highly valued for its higher smoke point and milder flavor compared with those of other vegetable oils [6]. Peanuts have garnered significant attention because of their bioactive components that exhibit potential for cancer prevention and anti-inflammatory effects, showing promise for disease prevention and treatment [5]. As of 2023, China’s annual peanut planting area was approximately 4.83 million hectares, accounting for 25% of the global total, with a total output of approximately 19 million tons, representing 35% of the global peanut production [7].

Recently, fresh peanuts have gained widespread popularity in the consumer market. Peanuts can be consumed directly, preserving nutrients to the greatest extent possible, and are characterized by their sweet and crisp texture, aromatic and non-greasy taste, and easy digestibility. Carbohydrates in peanut kernels are a crucial component of dry matter, playing a vital role in determining flavor quality and directly affecting the quality of deep-processed products, such as candies and baked goods containing peanuts [8,9]. Sucrose is the primary soluble carbohydrate in peanut kernels. Pattee et al. found that the sucrose content in 52 peanut varieties ranged between 20.32 and 42.28 mg/g [8]. Among the 185 popular peanut varieties in China, the lowest sucrose content was only 10.20 mg/g, whereas the highest was 84.80 mg/g [9]. Currently, high-sucrose-content peanut varieties are relatively few in China, because of which meeting the market demand has become challenging. Therefore, breeding of and research on high-sucrose and sweet-tasting edible peanut varieties have garnered increasing attention, and controlling sucrose accumulation in peanut kernels is a key direction for breeding high-sucrose varieties [10].

Sucrose is the most important and widely distributed disaccharide required for plant growth and development. It acts not only as a product of photosynthesis in higher plants, but also as a primary form of carbohydrate storage and accumulation [11,12]. Plant growth and development depend on nutrient supply, which in turn relies on the dynamic regulation of source-sink relationships. This relationship constitutes a highly complex and finely tuned transport process that ensures that plants maintain normal physiological functions across different growth stages and environmental conditions [13]. Therefore, the synthesis, transport, and utilization of sucrose are tightly regulated, and alterations in these processes can profoundly affect plant growth and development [14,15].

Sucrose transport pathways primarily include the apoplastic and symplastic pathways [16,17]. Long-distance transport and distribution of photosynthetic nutrients from the source to the sink require sugar transporters. Three key types of sugar transporters exist in most plants: sucrose transporters (SUT/SUC), sugar-exported transporters (SWEET), and monosaccharide transporters (MST) [18]. Among these, SUCs are a class of membrane-bound proteins with sucrose transport capability and are widely distributed in tissues and cells of higher plants. They actively load sucrose onto the sieve element-companion cell complex in phloem sieve tubes, making SUCs crucial for photosynthetic carbon allocation between source and sink tissues [19,20]. Typically containing 12 transmembrane (TM) α-helices, a characteristic of major facilitator superfamily (MFS) proteins, SUCs are widely distributed throughout plants. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that angiosperm SUCs form three major clades, designated by Aoki et al. as types I, II, and III [21]. Type II SUCs are subdivided into ancestral forms, specifically Type IIA SUCs, which are present in all land plants. Type IIB SUCs are unique to monocotyledons and include phloem-loading transporters in these species [22].

Most SUTs function as energy-dependent proton-coupled sucrose/H+ symporters, utilizing proton motive force to transport sucrose across membranes against concentration gradients. Arabidopsis thaliana’s AtSUC1 represents one of the earliest identified H+-coupled sucrose transporters in plants [23]. Spinach SoSUC1 was the first SUC to be isolated [24]. With the gradual release of plant genomic data and rapid development of molecular biology, breakthroughs have been made in elucidating the functions of SUCs in various plants. The functions and regulatory mechanisms of SUCs have been reported in numerous model plants, including Arabidopsis [25,26,27], maize [28,29], sorghum [30,31], and rice [32,33]. Additionally, functions of SUCs have been studied in some fruits, including strawberries [34], apples [35], and peaches [36]. These studies have laid the foundation for studying the SUC gene family while also providing insights into the molecular mechanisms of sugar accumulation in plants.

Considering that SUC plays a crucial role in regulating sugar accumulation in fruits, studying the function of SUC in sugar accumulation in peanut kernels is important for breeding high-sucrose peanut varieties. However, current reports on peanut SUC genes remain limited, particularly with respect to genome-wide identification of the peanut SUC gene family and their roles in sucrose accumulation in peanut seeds. To address this, we conducted genome-wide identification of the SUC gene family in cultivated peanut (A. hypogaea) by analyzing gene structure, conserved motifs, phylogenetic relationships, synteny, promoter cis-regulatory elements, and tissue expression patterns. In addition, we investigated the expression characteristics of SUC genes and their sucrose transport functions in high-sugar peanut varieties. The objective of this study was to systematically characterize the SUC gene family in peanut at the whole-genome level and to elucidate their roles in sucrose accumulation in seeds. Our findings will provide a theoretical foundation and technical support for understanding the molecular mechanisms of sugar transport and accumulation in peanut, which will be useful for breeding high-sugar varieties. This advancement will promote diversification of the peanut industry from traditional oilseed production to fresh consumption, processing, and other applications, thereby enhancing economic benefits and market competitiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of SUC Genes in Peanut

The genome of A. hypogaea cv. Shitouqi was obtained from the Peanut Genome Resource (PGR) database (https://pgr.itps.ncku.edu.tw/download_genomic_data.php, accessed on 18 July 2025) [37]. Use nine Arabidopsis thaliana AtSUC proteins to align with the peanut genome and screen candidate AhSUC protein sequences. Candidate proteins containing sucrose/proton co-transporter (GPH_sucrose, IPR005989) conserved domains were then identified using an NCBI Batch CD Search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi, accessed 20 July 2024). Additionally, TM structures were predicted using TMHMM-2.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/, accessed 20 July 2025) to screen for members containing the typical 12 TM α-helical structure of the MFS proteins [38].

2.2. Chromosomal Localization and Physicochemical Properties

Based on annotated peanut genome data, TBtools (version 2.376) [39] was used to perform chromosomal physical mapping and visualization of AhSUC gene family members. AhSUC genes were named according to their chromosomal order. Protein molecular weight and isoelectric point predictions for peanut AhSUC candidate genes were performed using ExPASy (version 3.0) (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 25 July 2025). Subcellular localization was predicted using ProtComp (version 9.0) (http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=protcomppl&group=programs&subgroup=proloc, accessed on 25 July 2025).

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of the SUC Gene Family

Multiple alignments of SUC amino acid sequences from peanut, Arabidopsis, and rice were performed using the MEGA11 (version 11) [40]. The alignment results were used to construct a phylogenetic tree using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized using the iTOL online tool (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 21 August 2025).

2.4. Gene Structure and Analysis of Conserved Motifs

Conserved motif analysis of the AhSUC protein sequence was performed using the online tool, MEME Suite 5.5.8 (https://meme-suite.org/meme/, accessed on 21 August 2025) [41]. The maximum number of motifs was set to 10, and all other parameters were set to their default values. Based on the MEME results, motif patterns were redrawn using TBtools (version 2.376) [39]. An NJ phylogenetic tree was constructed using the MEGA11 (version 11). Genome annotation files were analyzed for gene structure using TBtools [39], integrating phylogenetic analysis of all AhSUCs and conserved motif analysis for a more detailed representation. Batch CD Search analysis was performed on 16 target sequences, and TBtools [39] was used to visualize conserved structural domains.

2.5. Protein Structure Analysis of Peanut AhSUCs

To gain more insights into the structural characteristics of AhSUCs in peanut, the online tool SOPMA (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/, accessed on 23 August 2025) was used to predict and analyze their secondary structures. Following secondary structure analysis, SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/, accessed on 23 August 2025) was used for tertiary structure modeling.

2.6. Promoter Cis-Element Analysis

The upstream sequence (2 kb) of the peanut AhSUC coding region was retrieved from the genome sequence using TBtools (version 2.376) [39]. This sequence was then submitted to PlantCARE [42] (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 24 August 2025) to identify regulatory elements. The data obtained were visualized using TBtools (version 2.376) [39].

2.7. Collinearity Analysis

Genome and annotation information for soybean and A. thaliana were downloaded from the NCBI database. Based on the genomic annotation of the peanut AhSUC gene, collinearity analysis with Arabidopsis and soybean was performed using the multiple collinearity scanning tool (MCScanX) in TBtools (version 2.376) [39]. The collinearity relationships of AhSUC were visualized using the advanced Circos tool in TBtools (version 2.376) [39]. The Ka/Ks values for homologous gene pairs of peanut AhSUCs were calculated and analyzed using the simple Ka/Ks Calculator tool in TBtools (version 2.376) [39].

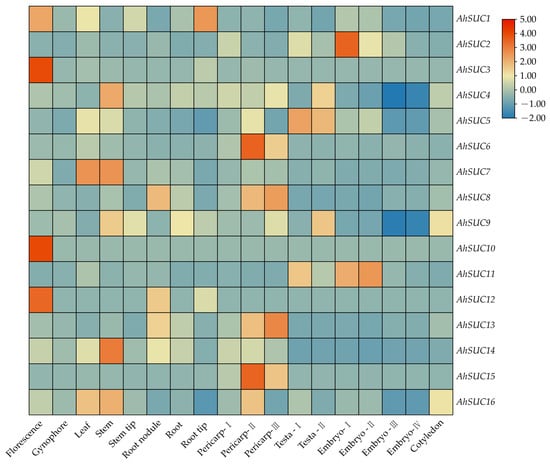

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis

Based on the gene IDs of the peanut SUC gene family, expression levels in different tissues and developmental stages of the peanut cultivar Shitouqi were retrieved from the PGR database (https://pgr.itps.ncku.edu.tw/transcriptome.php, accessed on 30 July 2025). The analyzed tissues included cotyledon, embryo-I, embryo-II, embryo-III, embryo-IV, florescence, gynophore, leaf, pericarp-I, pericarp-II, pericarp-III, root, root and stem, root nodule, root tip, stem, stem tip, testa-I, and testa-II.

2.9. Plant Materials and Determination of Sucrose Content

In this study, two peanut varieties with contrasting sugar contents were used: Zhongkaihua 1 (low-sugar variety, ZKH) and Nanbeihong (high-sugar variety, NBH), both bred by the Zhongkai Agricultural Engineering College. The plants were cultivated under open-field conditions at the experimental base of the Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology, with each variety planted in separate plots spaced 20 cm × 30 cm apart. Approximately 100 plants per variety were grown to ensure that biological replicates were available. Sampling was conducted at three critical stages of seed development: early development (20 days after pollination, DAP, S1), seed-filling stage (40 DAP, S2), and physiologically mature stage (60 DAP, S3). Thirty seeds from the same developmental stage were pooled as one biological sample, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Three biological replicates were used for each developmental stage.

Approximately 100 mg of the peanut sample was ground in liquid nitrogen, followed by the addition of 2 mL of deionized water. The mixture was extracted at 80 °C for 30 min in a water bath. After cooling, the extract was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. The sucrose content of the supernatant was determined using the resorcinol spectrophotometric method [43].

2.10. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from the three varieties at all three stages using a FastPure Universal plant total RNA isolation kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Reverse transcription was performed following the protocol of the HiScript® II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) kit (Vazyme). Using cDNA synthesized from the reverse transcription as the template and AhActin as the internal reference gene, qRT-PCR analysis was performed on the peanut AhSUC gene. The primer sequences are shown in Table S1 (primers were synthesized by Guangzhou Tianyi Huiyuan Gene Technology Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China)).

The qRT-PCR system of 20.0 μL consisted of 10.0 μL of 2× ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR master mix (Vazyme), 0.4 μL each of the forward primer and reverse primer, 2.0 μL cDNA, and 7.2 μL ddH2O. The PCR program was as follows: 95 °C pre-denaturation for 30 s; 95 °C denaturation for 10 s, 60 °C extension for 30 s, repeated for 40 cycles. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [44].

2.11. Verification of Sucrose Transport Capacity of Peanut AhSUC

The sucrose transport capacity of peanut AhSUCs was verified by heterologous expression in the sucrose transport-deficient yeast strain, SUSY7/ura3, using the yeast expression vector, pDR196. PCR was performed using peanut cDNA as the template (primer sequences are shown in Table S1). pDR196 was digested using EcoRI and XhoI. The pDR196-AhSUCs recombinant plasmid was constructed using the ClonExpress II One Step cloning kit (Vazyme). The plasmid was transformed into SUSY7/ura3 using the PEG/LiAc method (30 min heat shock at 30 °C, followed by 15 min heat shock at 42 °C), plated on SC/–Ura medium (Coolaber, Beijing, China), and incubated at 29 °C. Single clones were selected and cultured in SC/–Ura broth containing 2% glucose until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.6–0.8. Serial dilutions of the cultures were prepared, and 1.5 μL of each dilution was dispersed onto both SC/–Ura medium containing 2% sucrose and SC/–Ura medium containing 2% glucose. The plates were incubated at 29 °C for 3–4 days. Colony growth was observed using SUSY7/ura3 cells carrying an empty pDR196 vector as the control.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All experimental data were obtained in triplicate. Data organization, analysis, and chart generation were performed using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 10.2.3. Duncan’s multiple range test was used to perform multiple comparison analyses of sucrose content and gene expression.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Physicochemical Analysis of SUC Genes in Peanut

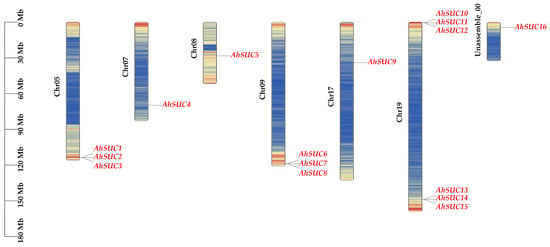

Sixteen AhSUC genes were identified in the cultivated peanut genome and sequentially named AhSUC1 to AhSUC16 based on their chromosomal localization (Figure 1). All 16 AhSUCs encode proteins containing the conserved sucrose/proton co-transporter domain and exhibit 12 TM α-helical structures, consistent with the characteristics of the MFS proteins (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of AhSUC genes on peanut chromosomes. Chr05, Chr07, Chr08, Chr09, Chr17, Chr19, and Unassemble-00 represent the chromosome designations of peanut. The scale on the left indicates chromosome length. Different colors in the figure represent gene density.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of AhSUC genes.

The AhSUC genes are distributed across chromosomes A05, A07, A08, A09, A17, A19, and Unassemble-00. Among these, chromosome A19 harbored the highest number of AhSUC genes (six), followed by chromosomes A05 and A09 (three each), whereas chromosomes A03, A07, A08, A13, A17, and Unassemble-00 each contained only one member. The results indicated that SUC genes were widely but unevenly distributed across the peanut genome.

The physicochemical properties of AhSUCs were predicted. The 16 AhSUC genes encode proteins ranging in length from 499 to 521 amino acids. The molecular weights of these AhSUC proteins fall between 52,994.20 and 55,019.54, with their theoretical isoelectric points ranging from 7.58 to 9.53. All proteins were classified as basic proteins. The results of predicted subcellular localization indicated that all 16 SUC proteins were possibly localized in the plasma membrane. All AhSUC proteins exhibited positive Grand Average of Hydropathy (GRAVY) values (ranging from 0.494 to 0.596), suggesting that these proteins are hydrophobic (Table 1).

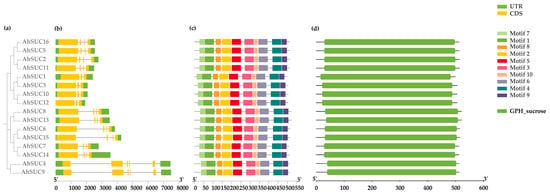

3.2. Analysis of AhSUC Protein Motifs and Gene Structure

To gain deeper insight into the structural diversity of peanut SUT genes, we analyzed their exon-intron organization based on genomic sequences. The results revealed significant variation in the number of exons and introns among the three peanut SUT genes, ranging from three to five exons and two to five introns (Figure 2a,b). Notably, a substantial proportion of the peanut SUT genes contained four exons (10 of 16, 62.5%). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that peanut SUT genes within the same clade shared similar gene structures. These findings demonstrated the structural conservation and diversity of peanut SUC genes.

Figure 2.

Analysis of AhSUC protein motifs and gene structure in peanut. (a) Phylogenetic relationships. (b) Gene structure of AhSUC proteins. Exons are shown in yellow, and introns are indicated by black lines. (c) Conserved motif analysis. (d) Analysis of conserved domains in AhSUC proteins.

Further analysis of the conserved motifs in cultivated peanut AhSUC proteins revealed that all 16 peanut AhSUC genes contained identical conserved motifs (Figure 2c). Parallel analysis of conserved domains confirmed that all peanut AhSUCs possessed a sucrose/proton co-transporter (GPH_sucrose, IPR005989) domain (Figure 2d), indicating high domain conservation in peanut SUC proteins.

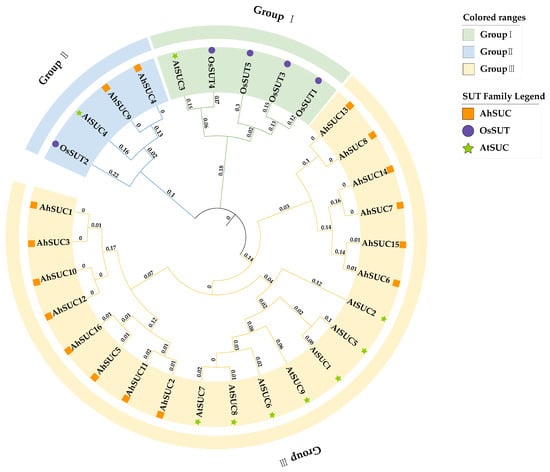

3.3. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis in Peanut

Previous studies on Arabidopsis and rice have shown that SUTs can be classified into three groups: Group III includes AtSUC1, AtSUC2, AtSUC5, AtSUC7, AtSUC8, and AtSUC9; Group I includes AtSUC3, OsSUT1, OsSUT3, OsSUT4, and OsSUT5; and AtSUC4 and OsSUT2 belong to Group II [22,31]. Phylogenetic analysis based on the amino acid sequences of peanut SUCs (AhSUCs) in comparison with those from Arabidopsis and rice revealed that most AhSUC genes belong to Group III SUTs, with only AhSUC4 and AhSUC9 classified as Group II SUTs (Figure 3). No Group I SUT genes were identified.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of SUC proteins in Arachis hypogaea, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa. The phylogenetic analysis of SUC-related gene families from the three species was constructed using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method. In the final phylogenetic tree, different colored backgrounds indicate distinct clades, whereas differently colored shapes represent the species included in the analysis: Ah—Arachis hypogaea (light green, star); Os—Oryza sativa (purple, circle); At—Arabidopsis thaliana (orange, square).

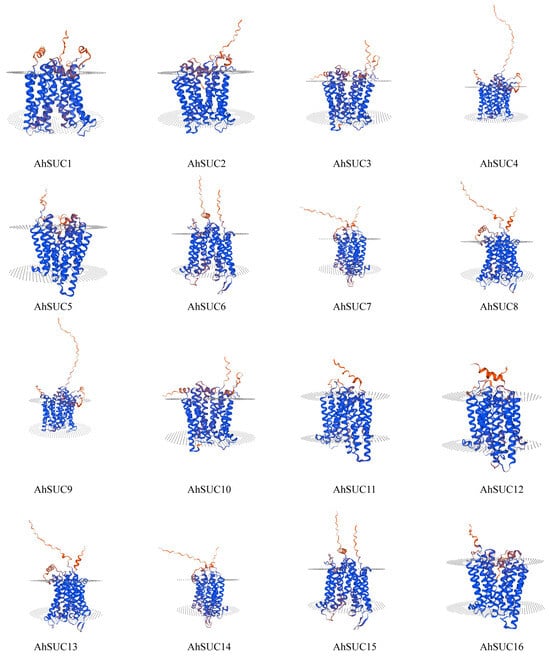

3.4. Prediction and Analysis of Peanut AhSUC Protein Structure

Next, we analyzed the structure of the peanut AhSUC proteins (Table S2). Analysis of the secondary structure revealed that it primarily consists of α-helices, extended chains, β-turns, and random coils. Among these four secondary structures, the proportion of biological secondary structures in the peanut AhSUC proteins was as follows: α-helices > random coils > extended chains > β-turns. The α-helix content ranged from 42.91% to 47.79%, extended chain content from 13.82% to 17.58%, β-turn content from 2.97% to 4.69%, and disordered coil content from 32.46% to 37.89%. β-Turns constituted the smallest proportion of secondary structures in the AhSUC proteins. The tertiary structures of the AhSUC family proteins were predicted using the SWISS-MODEL website (Figure 4). They were highly similar to the typical 12-TM α-helix proteins. Protein spatial structure is fundamentally determined by amino acid sequence, and each AhSUC protein possesses a distinct sequence with unique features. These sequence-specific variations give rise to differences in structural elements (including α-helices, β-turns, and random coils) among AhSUC proteins, ultimately leading to diversity in their tertiary folding patterns.

Figure 4.

Tertiary structure of the AhSUC proteins.

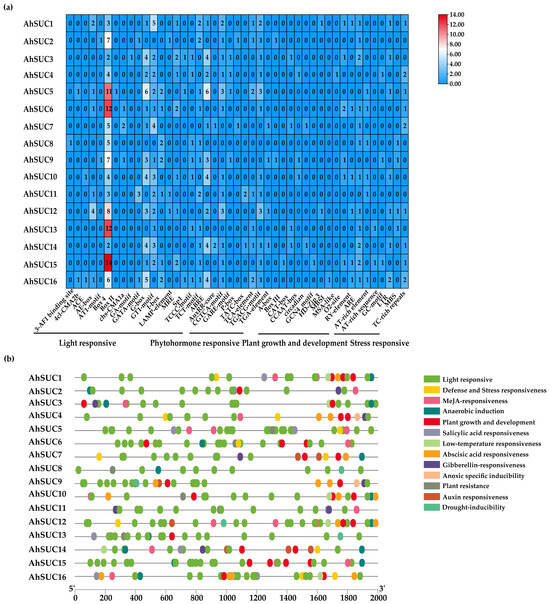

3.5. Cis-Acting Elements in the AhSUC Gene Promoter

Analysis of the 2000 bp upstream sequence of the AhSUC gene extracted from the peanut genome database revealed numerous basic cis-acting, light-responsive, hormone-responsive, and stress-responsive elements associated with growth and development (Figure 5a,b). Hormone-responsive cis-acting elements are primarily of five categories: abscisic acid response element (ABRE), gibberellin response element (GARE-motif/P-box/TATC-box), methyl jasmonate-responsive element (CGTCA-motif/TGACG-motif), auxin-responsive element (AuxRR-core/TGA-element), and salicylic acid-responsive element (TCA-element). Among these, ABRE and methyl jasmonate-responsive elements are particularly prevalent and present in over 70% of AhSUC gene promoters. Notably, AhSUC8 lacks hormone-responsive elements (Figure 5a). The cis-acting elements associated with stress responses are primarily of six categories: defense and stress response (TC-rich repeats), anaerobic induction response (ARE), plant resistance response (AT-rich sequence), drought-induced response (MBS), hypoxia-specific induction response (GC motif), and cold response (LTR). These findings suggest that members of the peanut AhSUC gene family play crucial roles in regulating seed development and enhancing stress resistance (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Cis-acting elements of the promoters of AhSUC genes. (a) Heat map showing the number of cis-acting elements in the putative promoters of AhSUC-related genes. Different colors indicate the abundance of cis-acting elements, with red representing the highest number and blue the lowest. (b) Distribution of cis-acting elements within the 2000 bp upstream promoter regions of AhSUC-related genes. Different types of cis-acting elements are represented by different colors.

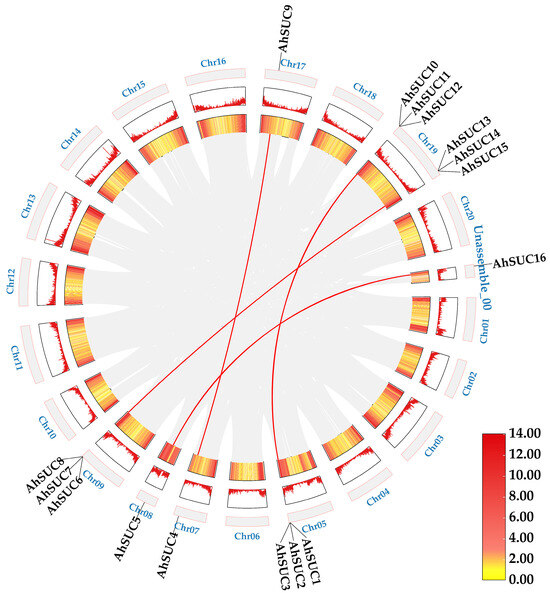

3.6. AhSUC Gene Collinearity Analysis

Results of the intragenomic collinearity analysis for the peanut AhSUC gene (Figure 6) revealed four SUC paralog pairs across the peanut genome, all arising from whole-genome duplication or segmental duplication events. The non-synonymous substitution rate (Ka) for the AhSUC gene pairs ranged from 0 to 0.2399 (mean, 0.0666), whereas the Ka/Ks ratio ranged from 0 to 0.1758 (mean, 0.0676) (Table S3). All Ka/Ks means were significantly less than 1 (p < 0.01), indicating the occurrence of a strong purifying selection event during evolution and highly conserved function.

Figure 6.

Regional collinearity of AhSUC genes in peanut. Red lines indicate duplicated AhSUC gene pairs.

Inter-species collinearity analysis of SUC between Arachis hypogaea, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Glycine max was performed using TBtools (Figure 7). Only two collinear gene pairs were detected between peanut and Arabidopsis, whereas 14 collinear gene pairs were identified between peanut and soybean. These results indicate a higher homology within the SUC gene family of peanut and soybean. Therefore, we speculated that these two species may be genetically close or may have undergone similar gene expansion events during the evolution of this gene family. This further indicates the presence of potential common features involved in the regulation of related biological functions.

Figure 7.

Interspecific collinearity of SUC genes among Arachis hypogaea, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Glycine max. Red bands represent Arabidopsis thaliana chromosomes, blue bands represent Arachis hypogaea chromosomes, and green bands represent Glycine max chromosomes. The numbers above the bands indicate chromosome labels. Purple lines indicate collinear gene pairs. The triangles indicate the positions of AhSUC on the chromosomes.

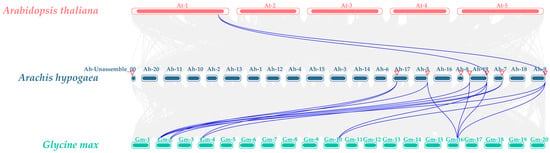

3.7. Analysis of AhSUC Gene Expression Datasets

Analysis of AhSUC expression across different tissues and developmental stages of peanut revealed significant tissue-specific differences (Figure 8). AhSUC1 expression was very low in all tissues and developmental stages. AhSUC2 was predominantly expressed in the embryo, whereas AhSUC3 and AhSUC10 were mainly expressed in flowers, with almost no expression in other tissues. AhSUC4 was primarily expressed in stems, roots, pericarps, testa, and cotyledons. AhSUC5 was highly expressed in all tissues at all stages. AhSUC6 was predominantly expressed in the pericarp, whereas AhSUC7 was highly expressed in the leaves and stems. AhSUC8 was highly expressed in root nodules, pericarps, flowers, stems, and cotyledons. AhSUC9 was highly expressed in stems, roots, pericarps, testa, and cotyledons. AhSUC11 was mainly expressed in the testa and embryos, whereas AhSUC12 showed negligible expression across all tissues or stages. AhSUC13 was highly expressed in the root nodules, roots, pericarps, and cotyledons. AhSUC14 was highly expressed in the stems, and AhSUC15 was predominantly expressed in the pericarp. AhSUC16 was highly expressed in stems, leaves, pericarps, and cotyledons.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of AhSUC gene expression across different tissues and developmental stages in the peanut cultivar Shitouqi. The heatmap displays normalized FPKM values.

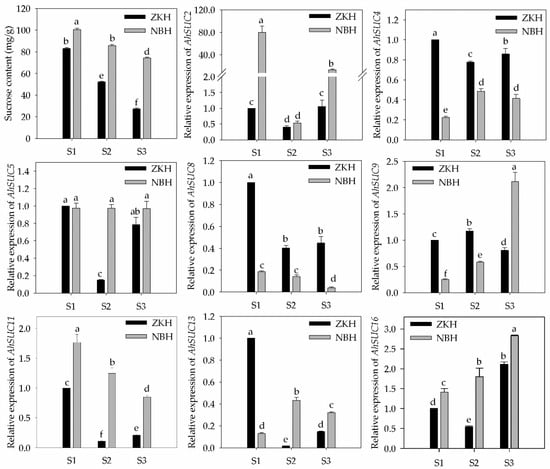

3.8. Sucrose Content and AhSUC Expression During Peanut Development

The sucrose content in peanut seeds decreased continuously during development, with Zhongkaihua 1 showing a rapid decline, whereas the high-sugar variety, Nanbeihong, exhibited a slower decrease and maintained significantly higher levels than Zhongkaihua 1 throughout the growth period (Figure 9). We analyzed the expression of eight AhSUCs that were highly expressed in the cotyledon and embryo of the two varieties, defining differential gene expression as a relative expression fold change >2, with statistical significance between varieties (Figure 9). AhSUC2 expression in Nanbeihong was significantly higher than that in Zhongkaihua 1 at S1 and S3, whereas Zhongkaihua 1 showed higher AhSUC4 expression at all three stages. Difference in AhSUC5 expression was not observed between the two varieties at S1 and S3, although Nanbeihong showed higher expression in S2. AhSUC8 expression decreased over time and was consistently higher in Zhongkaihua 1 than in Nanbeihong. AhSUC9 expression in Zhongkaihua 1 increased initially and then declined, whereas AhSUC2 expression in Nanbeihong increased and was significantly higher at stage S3. AhSUC13 expression in Zhongkaihua 1 was significantly higher at S1, whereas that in Nanbeihong was higher at S2, with no difference at S3. AhSUC16 expression increased over time, with no difference between S1 and S3; however, Nanbeihong showed higher expression in S2. These results showed that the expression of AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 was significantly higher in the high-sugar varieties, which was related to increased sucrose accumulation.

Figure 9.

Sucrose content and relative expression of AhSUC genes in seeds of two peanut varieties at three developmental stages. ZKH, Zhongkaihua 1 (low-sugar variety); NBH, Nanbeihong (high-sugar variety). S1, 20 days after pollination (early developmental stage); S2, 40 days after pollination (seed-filling stage); S3, 60 days after pollination (physiologically mature stage). Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Duncan’s multiple range test.

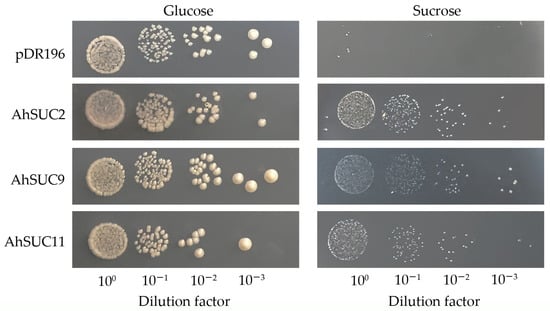

3.9. Sugar Transport Capacity of Peanut AhSUC9

The yeast sucrose transport-deficient mutant, SUSY7/ura3, is an invertase-deficient strain that cannot grow on SC-Ura medium with sucrose as the sole carbon source but grows normally on SC-Ura medium supplemented with glucose. To verify the sugar transport activities of AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11, the genes encoding these three proteins were heterologously expressed in SUSY7/ura3. SUSY7/ura3 transformed with the empty vector did not grow on SC/-Ura medium containing 2% sucrose, whereas the yeast transformed with recombinant vectors containing AhSUC2, AhSUC9, or AhSUC11 grew normally, indicating that these three proteins possess sucrose transport capabilities (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Validation of the functional complementation by AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 in a yeast mutant (SUSY7/ura3). Strains were cultured on SC/–Ura/glucose (left) and SC/–Ura/sucrose (right) media, with the empty vector (pDR196) used as a negative control. Ten-fold serial dilutions were inoculated onto solid media for incubation and imaging.

4. Discussion

Sucrose acts not only as a central depot for carbon storage and energy supply but also as a regulator of various physiological processes in plants, such as carbohydrate metabolism, storage protein accumulation, anthocyanin accumulation, and flower induction. In this study, we aimed to provide a comprehensive genome-wide analysis of the SUC gene family in cultivated peanut (A. hypogaea L.), as information on sucrose transport in peanut is limited. SUTs belong to the MFS superfamily of transporters and are characterized by 12 highly hydrophobic TM domains [21,45]. All 16 AhSUC genes identified in the cultivated peanut genome contain the 12-TM α-helical structure characteristic of the MFS superfamily. These were concentrated on chromosomes A05, A07, A08, A09, A17, A19, and Unassemble-00, exhibiting a markedly uneven distribution pattern. Notably, chromosome A19 harbored six members, accounting for 37.5% of the total family. Compared to the nine AtSUC genes in Arabidopsis [26,27], five OsSUT genes in rice [13,21,32], and 18 GhSUT genes in cotton [46], the number of AhSUC genes in peanut is approximately double that in Arabidopsis. Expansion of the SUT gene family may be a key factor responsible for the accumulation of carbohydrates and lipids in seeds.

Collinearity analysis provided crucial insights into the evolutionary dynamics of the AhSUC gene family. The four pairs of paralogs detected within the peanut genome originate from whole-genome or segmental duplications [47]. Moreover, the mean Ka/Ks ratio (0.0676) for all gene pairs was significantly lower than 1, indicating that this gene family underwent strong purifying selection during evolution and exhibits highly conserved functions, consistent with observations in other species [48,49]. Cross-species collinearity analysis revealed 14 SUC collinear gene pairs between peanut and soybean, compared to only two pairs with Arabidopsis. This suggests that peanut and soybean may share a close genetic relationship in the evolutionary history of the SUC gene family or may have undergone similar gene amplification events. We speculated that these three species share common features in the regulation of biological functions related to sucrose transport, laying the foundation for subsequent comparative genomic research.

In recent years, phylogenetic analyses of SUC genes have been conducted across numerous species, and a common classification method divides plant SUCs into three clades (Groups I–III) [49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Group I can be further subdivided into two subgroups: Group IA consists of SUT genes from monocots and dicots, whereas Group IB is a monocot-specific subgroup. SUTs in Group II are found in all terrestrial plants, whereas SUTs in Group III are exclusive to dicots. Most AhSUCs in peanut belong to Group III SUTs, whereas AhSUC4 and AhSUC9 belong to Group II. The absence of Group I SUT genes is speculated to be related to plant-specific gene loss events, thus providing new clues for understanding the evolution of the SUT family in different plants.

Protein structure analysis revealed structural conservation and functional relevance within the AhSUC gene family. All AhSUC proteins exhibit a characteristic 12-TM α-helical structure, with six N-terminal and six C-terminal helices connected by cytoplasmic loops to form dual pseudo-symmetry. This structure was highly homologous to the structure of Arabidopsis AtSUC proteins [45,49], confirming the evolutionary stability of the protein structures of the MFS superfamily. Motif analysis indicated that all 16 AhSUC proteins contained ten conserved motifs in a consistent sequence and possessed a GPH sucrose conserved domain. These conserved elements form the core structural basis for maintaining the sucrose transport function. Furthermore, gene structure analysis revealed that the number of introns (3–5) closely correlated with the evolutionary subfamily classification: Group III genes predominantly contained 3–4 introns, whereas Group II genes primarily possessed five introns. Variations in intron number may influence gene transcription efficiency or mRNA processing, thereby contributing to functional differentiation among subfamilies.

Analysis of cis-acting elements in the promoter revealed multiple functions of AhSUC transcriptional regulation. Five hormone response elements were detected in the peanut sucrose transporters, with the ABRE and methyl jasmonate response element (CGTCA-motif/TGACG-motif) being the most widely distributed. AhSUC8 is a unique member of this family, owing to the absence of all hormone response elements. Notably, AhSUC8 may participate in basal sucrose transport via non-hormone-dependent pathways as its expression is not induced by stress. This functional differentiation is responsible for the ability of peanut to cope with complex environmental conditions. Hormone- and stress-responsive cis-acting elements form the core molecular basis determining the involvement of this gene in the regulation of stress resistance. For example, abscisic acid and gibberellin can induce MdSUT1 expression and enhance plant tolerance to abiotic stress [56]. The sucrose transporter, MdSUT2.2, promotes sugar accumulation and improves drought tolerance in apple [57]. The pineapple AcCBF1 directly binds to the CRT/DRE element in the AcSUT1B promoter and activates its expression, thereby enhancing cold tolerance [58]. Thus, cis-acting elements of AhSUC constitute a crucial defense system for peanut responses to abiotic stresses, providing key theoretical support for stress-resistance mechanisms and the development of stress-tolerant cultivars.

The tissue-specific expression of SUC genes confers distinct physiological functions. Transcriptome analysis revealed differential expression of AhSUC genes across various tissues, with AhSUC2, AhSUC4, AhSUC5, AhSUC8, AhSUC9, AhSUC11, AhSUC13, and AhSUC16 highly expressed in cotyledons and embryos. Phylogenetic tree analysis indicated that rice OsSUT4 and Arabidopsis AtSUC2 are closely related to AhSUC4 and AhSUC9, suggesting that they may perform conserved functions. OsSUT4 is predominantly expressed in rice mesophyll cells, primary lateral roots, pedicels of fertilized spikelets, seed coat transcellular layers, embryos, and aleurone layers; knockout of OsSUT4 reduces tiller number and yield in mutant rice lines [59,60]. DfSUT4 in Dendrocalamus farinosus is highly expressed in stems, and its overexpression in tobacco promotes plant growth, with transgenic plants exhibiting taller stems and larger leaves, flowers, and fruits [50]. Arabidopsis AtSUC5, together with AhSUC2, AhSUC5, AhSUC8, AhSUC11, AhSUC13, and AhSUC16, belongs to Group III. AtSUC5 is specifically expressed in the Arabidopsis endosperm and participates in the regulation of early seed development [61]. These findings suggest that the genes upregulated in peanut seeds may be involved in sugar accumulation and lipid synthesis. To further clarify the roles of these eight genes in sugar accumulation in peanut seeds, sucrose content and gene expression were compared between high-sugar and low-sugar varieties during fruit development. Sucrose content decreased during seed development in both varieties; however, the high-sugar variety maintained significantly higher sucrose levels than the conventional variety at all three stages. The expression levels of the eight genes also differed between the two peanut varieties during seed development. Among them, AhSUC2 expression in the high-sugar variety was higher than that in the low-sugar variety at stages S1 and S3. AhSUC11 exhibited higher expression in the high-sugar variety than in the low-sugar variety across all three developmental stages. Interestingly, although they are homologous genes, AhSUC4 and AhSUC9 showed distinct expression patterns between the two varieties: AhSUC4 expression was higher in the low-sugar variety, whereas AhSUC9 expression in the high-sugar variety was significantly higher than that in the low-sugar variety at stage S3. This differential expression between varieties may contribute to higher sucrose accumulation in the high-sugar variety, likely resulting from differences in promoter elements between AhSUC4 and AhSUC9, which in turn lead to expression divergence. Functional complementation assays in the sucrose transport-deficient yeast mutant, SUSY7/ura3, demonstrated that all three proteins (AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11) possessed sucrose transport activity. These results indicate that AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 play key roles in sugar accumulation in the seeds of high-sugar peanut varieties. This study reveals the potential roles of AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 in sucrose accumulation in peanut seeds, offering novel targets for breeding high-sugar varieties. However, this study has some limitations. First, the tissue-specific expression of these genes in the two varieties, particularly their expression patterns in different parts of the seed, requires further investigation. In addition, functional validation through overexpression or knockout experiments is needed, and the regulatory mechanisms of these genes remain unclear, especially in naturally high-sugar varieties. Second, the regulatory network of upstream transcription factors has not been systematically elucidated, hindering a comprehensive understanding of their expression regulation. Future research could explore the feasibility of enhancing seed sugar content by increasing the expression of AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 using gene-editing technologies, thereby providing theoretical foundations for the selection of high-quality peanut varieties.

5. Conclusions

Using systematic analysis of the peanut sucrose transporter (AhSUC) gene family, we identified 16 AhSUC genes. These genes exhibited clustered chromosomal distribution patterns, with their expansion primarily attributed to whole-genome or segmental duplication events, showing high homology with soybean SUC gene families. Promoter cis-element analysis revealed that the AhSUC genes contained various hormone-responsive elements (mainly ABRE and CGTCA-motif/TGACG-motif) and abiotic stress-responsive elements, suggesting their potential involvement in peanut abiotic stress defense systems. Eight AhSUC genes were highly expressed in peanut seed embryos and cotyledons. Further analysis indicated that high-sugar peanut varieties had significantly higher sucrose content in seeds than conventional varieties, with AhSUC2, AhSUC9, and AhSUC11 showing higher expression levels and sucrose transport activity in the high-sugar varieties. These findings suggest a potential role for these three genes in sucrose accumulation during peanut seed development. Our results have enhanced our understanding regarding the SUC gene family in peanut and offered theoretical insights into the mechanisms of sucrose transport, stress resistance, and breeding of high-sugar peanut varieties, thereby providing a foundation for future functional research regarding the role of these genes in sucrose accumulation in seeds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded from https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb48010029/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F. and Q.H.; methodology, Z.F. and Q.H.; software, Z.F. and Y.Z. (Yu Zhang); validation, Z.F., and X.C.; formal analysis, X.H. and J.L.; investigation, Z.F., and Q.H.; resources, Y.Z. (Yixiong Zheng); data curation, Z.F., Q.H. and X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.F., Q.H., and Y.Z. (Yu Zhang); writing—review and editing, Y.Z. (Yixiong Zheng), J.L. and X.H.; visualization, Z.F., X.C.; supervision, J.L. and X.H.; project administration, Y.Z. (Yixiong Zheng), X.H.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. (Yixiong Zheng), J.L. and X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The 2024 Special Fund for Rural Revitalization Strategy in Guangdong Province (2024-NPY-00-004). Special Fund for Talent Development Strategy of Guangdong Province, 2024 (YF2024NYRC03). Guangdong Science and Technology Innovation Strategy Special Project (Major Project and Task List) (2023S017083). Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project (71013513124232).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The yeast mutant (SUSY7/ura3) and vector (pDR196) were gifts from Xiaolei Sui of China Agricultural University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SUT | Sucrose transporters |

| SUC | Sucrose/H+ co-transporters |

| SWEET | Sugars Will Eventually Be Exported Transporters |

| MST | Monosaccharide Transporters |

| TM | Transmembrane |

| MFS | Major facilitator superfamily |

| NJ | Neighbor-joining |

| MCScanX | Multiple collinearity scanning tool |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| GPH_sucrose | Conserved sucrose/proton co-transporter |

| GRAVY | Grand Average of Hydropathy |

| PI | Isoelectric Point |

| NO. of TM | Number of Transmembrane Domains. |

| ABRE | Abscisic acid response element |

References

- Bertioli, D.J.; Jenkins, J.; Clevenger, J.; Dudchenko, O.; Gao, D.; Seijo, G.; Leal-Bertioli, S.C.M.; Ren, L.; Farmer, A.D.; Pandey, M.K.; et al. The genome sequence of segmental allotetraploid peanut Arachis hypogaea. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, F.C.; Nguepjop, J.R.; Ngalle, H.B.; Assaha, D.V.M.; Gessese, M.K.; Abtew, W.G.; Tossim, H.A.; Sambou, A.; Seye, M.; Rami, J.F.; et al. An Overview of Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci in Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Genes 2023, 14, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Varshney, R.K.; Zhuang, W.; Wang, X. Deciphering peanut complex genomes paves a way to understand its origin and domestication. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, L.; Zhou, J.; Li, R.; Pandey, M.K.; Han, Y.; Cui, F.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Chen, J.; et al. Genomic insights into the genetic signatures of selection and seed trait loci in cultivated peanut. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 42, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingrou, L.; Guo, S.; Ho, C.T.; Bai, N. Review on chemical compositions and biological activities of peanut (Arachis hypogeae L.). J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, Y.C.; de Oliveira Santos, G.; Machado, N.M.; Otoboni, A.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; Bishayee, A.; Fimognari, C.; Bishayee, A.; Barbalho, S.M. Corrigendum to Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) seeds and by-products in metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disorders: A systematic review of clinical studies Phytomedicine 123 (2024) 155170. Phytomedicine 2025, 136, 155870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/zh/#data (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Pattee, H.E.; Isleib, T.G.; Giesbrecht, F.G.; McFeeters, R.F. Investigations into genotypic variations of peanut carbohydrates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huai, D.; Gao, H.; Yan, L.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Kang, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Development and application of a near infrared spectroscopy model for predicting high sucrose content of peanut seed. Acta Agron. Sin. 2020, 47, 332–341. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, L.; Liu, N.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Yu, B.; Luo, H.; Zhou, X.; Huai, D.; Chen, W.; et al. Identification of a stable major sucrose-related QTL and diagnostic marker for flavor improvement in peanut. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.J.; Sun, M.H.; Liu, Y.J.; Lu, J.; Hu, D.G.; Hao, Y.J. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of the apple sucrose transporter gene MdSUT2. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 109, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommerrenig, B.; Müdsam, C.; Kischka, D.; Neuhaus, H.E. Treat and trick: Common regulation and manipulation of sugar transporters during sink establishment by the plant and the pathogen. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3930–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, I.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Pommerrenig, B. Improved resource allocation and stabilization of yield under abiotic stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 257, 153336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.F.; Leach, K.A.; Boyer, N.R.; Swyers, M.J.; Benitez-Alfonso, Y.; Skopelitis, T.; Luo, A.; Sylvester, A.; Jackson, D.; Braun, D.M. Sucrose Transporter ZmSut1 Expression and Localization Uncover New Insights into Sucrose Phloem Loading. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1876–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Fang, W.; Peng, W.; Jiang, M.; Chen, G.; Xiong, F. Sucrose transporter in rice. Plant Signal Behav. 2021, 16, 1952373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhungana, S.R.; Braun, D.M. Sugar transporters in grasses: Function and modulation in source and storage tissues. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 266, 153541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, B.T.; Leach, K.A.; Tran, T.M.; Mertz, R.A.; Braun, D.M. Sugar Transporters in Plants: New Insights and Discoveries. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1442–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, P.; Agarrwal, R.; Kajal; Gandass, N.; Manna, M.; Kaur, H.; Deshmukh, R. Sugar transporters and their molecular tradeoffs during abiotic stress responses in plants. Physiol. Plant 2022, 174, e13652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Bai, J.; Xie, Z.; Lian, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhao, F.; Liang, Y.; Huo, H.; Gong, H. Tomato sucrose transporter SlSUT4 participates in flowering regulation by modulating gibberellin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1080–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.T.; Cheng, S.C.; Chao, Y.T.; Lin, S.Y.; Yang, T.T.; Ho, Y.P.; Shih, M.C.; Ko, S.S. Sugars and sucrose transporters in pollinia of Phalaenopsis aphrodite (Orchidaceae). J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 2556–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, N.; Hirose, T.; Scofield, G.N.; Whitfeld, P.R.; Furbank, R.T. The sucrose transporter gene family in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinders, A.; Sivitz, A.B.; Ward, J.M. Evolution of plant sucrose uptake transporters. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasin, P.; Weise, A.; Reinders, A.; Ward, J.M. Arabidopsis Sucrose Transporter AtSuc1 introns act as strong enhancers of expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 2020, 61, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.F.; Qi, X.X.; Huang, X.S.; Xu, L.L.; Jin, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.L. Overexpression of sucrose transporter gene PbSUT2 from Pyrus bretschneideri, enhances sucrose content in Solanum lycopersicum fruit. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 105, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, M.; Mainson, D.; Porcheron, B.; Maurousset, L.; Lemoine, R.; Pourtau, N. Carbon source-sink relationship in Arabidopsis thaliana: The role of sucrose transporters. Planta 2018, 247, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottmann, T.M.; Fritz, C.; Lauter, A.; Schneider, S.; Fischer, C.; Danzberger, N.; Dietrich, P.; Sauer, N.; Stadler, R. Protoplast-Esculin Assay as a New Method to Assay Plant Sucrose Transporters: Characterization of AtSUC6 and AtSUC7 Sucrose Uptake Activity in Arabidopsis Col-0 Ecotype. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, J.; Reimann, T.M.; Fritz, C.; Schröder, C.; Knab, J.; Weber, W.; Stadler, R. How pollen tubes fight for food: The impact of sucrose carriers and invertases of Arabidopsis thaliana on pollen development and pollen tube growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1063765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, K.A.; Tran, T.M.; Slewinski, T.L.; Meeley, R.B.; Braun, D.M. Sucrose transporter2 contributes to maize growth, development, and crop yield. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017, 59, 390–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, B.; Bordoloi, D.; Parida, A. Diverse expression of sucrose transporter gene family in Zea mays. J. Genet. 2015, 94, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihmidine, S.; Baker, R.F.; Hoffner, C.; Braun, D.M. Sucrose accumulation in sweet sorghum stems occurs by apoplasmic phloem unloading and does not involve differential Sucrose transporter expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, R.J.; Reinders, A.; Ward, J.M.; Offler, C.E.; Patrick, J.W.; Grof, C.P.L. Contribution of sucrose transporters to phloem unloading within Sorghum bicolor stem internodes. Plant Signal Behav. 2017, 12, e1319030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, D.; Hu, Y. Rice SUT and SWEET Transporters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wen, J.; Chen, L.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, D. Transcriptome Analyses Show Changes in Gene Expression Triggered by a 31-bp InDel within OsSUT3 5′UTR in Rice Panicle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.T.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, S.H.; Gao, Q.H.; Zou, X.H.; Yang, J.; Dong, C.; Tan, J.H.; Ni, D.A.; et al. The sugar transporter system of strawberry: Genome-wide identification and expression correlation with fruit soluble sugar-related traits in a Fragaria × ananassa germplasm collection. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fan, W.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Functional analysis of MdSUT2. 1, a plasma membrane sucrose transporter from apple. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, W.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Xue, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.; et al. Major Facilitator Superfamily transporters balance sugar metabolism in peach. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, W.; Chen, H.; Yang, M.; Wang, J.; Pandey, M.K.; Zhang, C.; Chang, W.C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Tang, R. The genome of cultivated peanut provides insight into legume karyotypes, polyploid evolution and crop domestication. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; He, L.; Feng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, J.; Han, H.; Huang, X. Role of BraSWEET12 in regulating flowering through sucrose transport in flowering Chinese cabbage. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, D.; North, R.A.; Nagarathinam, K.; Tanabe, M. Structures and General Transport Mechanisms by the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS). Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 5289–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, U.P.; Evers, J.F.; Shaikh, M.A.; Ayre, B.G. Cotton phloem loads from the apoplast using a single member of its nine-member sucrose transporter gene family. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, W.; Zhu, F.; Wang, L.; Yu, Q.; Ming, R.; Zhang, J. Structure, phylogeny, allelic haplotypes and expression of sucrose transporter gene families in Saccharum. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Diao, W.; Liu, H.; Guo, Q.; Song, Q.; Guo, G.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. Molecular characterization of SUT gene family in Solanaceae with emphasis on expression analysis of pepper genes during development and stresses. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 14780–14798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, T.; Wu, L.; Ye, Z.; Ye, F. Plant SUT Sucrose Transporters: Structure, Evolution and Biological Functions. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2025, 26, e13892037372125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Gu, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Hao, S.; Wei, L.; Cao, Y.; Hu, S. Genome-wide analysis and characterization of Dendrocalamus farinosus SUT gene family reveal DfSUT4 involvement in sucrose transportation in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1118398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Gao, H.; Zhang, L.; Mao, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Hou, H. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of MST, SUT and SWEET transporters in Dendrobium catenatum. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, X.; Xing, L.; Ge, M.; Suo, N. Genome-Wide Identification, Plasma Membrane Localization, and Functional Validation of the SUT Gene Family in Yam (Dioscorea cayennensis subsp. rotundata). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; An, P.; Xia, C.; Ma, W.; Zhao, L.; Liang, T.; Liu, Q.; Xu, R.; Huang, D.; Xia, Z.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the SUT family from three species of Sapindaceae revealed their role in the accumulation of sugars in fruits. Plants 2024, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakkammal, K.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Shin, H.; Ramesh, M. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analysis of SUT genes reveals key regulators of drought stress response in finger millet (Eleusine coracana). J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.C.; Xu, Y.H.; Xi, R.C.; Zhao, X.L. Expression, subcellular localization and phytohormone stimulation of a functional sucrose transporter (MdSUT1) in apple fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 128, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.J.; Sun, M.H.; Kang, H.; Lu, J.; You, C.X.; Hao, Y.J. A CIPK protein kinase targets sucrose transporter MdSUT2.2 at Ser254 for phosphorylation to enhance salt tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Zhou, H.; Huang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, J.; Pu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, M.; Lu, X.; He, Y.; et al. The high-affinity pineapple sucrose transporter AcSUT1B, regulated by AcCBF1, exhibited enhanced cold tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.; Hsiao, H.H.; Chen, H.J.; Chang, C.W.; Wang, S.J. Influence of temperature on the expression of the rice sucrose transporter 4 gene, OsSUT4, in germinating embryos and maturing pollen. Acta Physiol. Plant 2014, 36, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, Z.; Ding, Y.; Ceng, L. Function analysis of sucrose transporter OsSUT4 in sucrose transport in rice. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2020, 34, 491–498. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, S.; Wuilleme, S.; Lemoine, R.; Kronenberger, J.; Caboche, M.; Lepiniec, L.; Rochat, C. The AtSUC5 sucrose transporter specifically expressed in the endosperm is involved in early seed development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005, 43, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.