Abstract

The protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) gene family plays vital roles in plant growth and stress responses, yet remains inadequately characterized in cotton, particularly in Gossypium barbadense renowned for its superior fiber quality. Here, we identified 152 GbPP2Cs in Gossypium barbadense through genome-wide analysis and comparative genomics with three related cotton species (G. arboreum, G. raimondii, and G. hirsutum), identifying 105, 105, and 204 GbPP2Cs, respectively. GbPP2Cs show uneven chromosomal distribution with notable clustering on A05, evolutionary conservation in gene structure and motif composition, and predominant nuclear/chloroplast localization. Phylogenetic analysis classified them into 15 subfamilies showing conserved evolution. Protein enrichment revealed 15 GbPP2Cs involved in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and hormone signaling pathways. Expression profiling revealed distinct members responsive to biotic/abiotic stresses, fiber development stages, and maturity. Notably, we discovered potential pleiotropic regulators including two genes (Gbar_D13G012000 and Gbar_A13G012360) co-regulating lint percentage and disease resistance, GbAIP1 coordinating fiber length-strength trade-off, and GbPP2C59 as a maturity negative candidate. These findings provide valuable genetic resources for cotton improvement.

1. Introduction

Sea Island cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.) is renowned for producing the finest quality natural fiber, prized in the textile industry for its exceptional length, strength, and fineness [1]. In China, its cultivation is predominantly confined to Xinjiang, where production is severely threatened by a combination of abiotic stresses, including salinity and drought [2], and biotic challenges such as Fusarium wilt [3]. Enhancing the resilience of G. barbadense without compromising its superior fiber quality and yield is therefore a critical breeding objective. Unraveling the genetic basis of these complex traits is essential for designing strategic crop improvement programs.

The type 2C protein phosphatase (PP2C) gene family, which is evolutionarily conserved and ubiquitous in virtually all organisms except viruses, is the most abundant among dephosphorylating enzymes in plants [4]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the PP2C family is expanded to 76 putative members [5,6,7]. Most PP2C genes in A. thaliana show close relationships with those from other plant species, clustering together into distinct clades [5]. In plants, most PP2C phosphatases possess a conserved catalytic domain at the C-terminus and a variable extension region at the N-terminus where they contain sequences associated with intracellular signaling, such as transmembrane domains and kinase interaction motifs, that confer diverse biological functions to PP2Cs [6]. For instance, in Arabidopsis, the abscisic acid insensitive (ABI)-type PP2C proteins contain an EF-hand motif extending from the N-terminus to the catalytic region, which binds Ca2+ and regulates the enzymatic activity controlled by the C-terminal catalytic domain [8].

The PP2C gene family plays versatile roles in plant stress adaptation and developmental regulation [9]. In stress responses, PP2Cs often modulate key signaling pathways. Arabidopsis HAI phosphatases (HAI1, HAI2, and HAI3) interact with mitogen-activated protein kinase 3/6 (MPK3/6) to mediate abscisic acid (ABA)-dependent immune suppression [10]. G. hirsutum GhDRP1s function as a negative regulator of drought tolerance through abscisic acid (ABA) and flavonoid pathway [11]. G. barbadense GbPP2C80s negatively modulate the resistance to wilt diseases through MPK3 and reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathways [3]. Such regulatory roles extend to other species, including Apocynum and sugarcane, where specific PP2Cs respond to salt or cold stress [12,13]. PP2Cs also participate in developmental processes: SlPP2C silencing delays senescence in tomato [14], and BjuPP2C52 interacts with transcription factors to control flowering time in Brassica juncea [15], collectively highlighting the functional diversity and conservation of this gene family.

Given their potential to influence stress adaptation and developmental processes, we hypothesized that the PP2C gene family represents a valuable genetic resource for improving both resistance, fiber, and maturity in G. barbadense. Although the PP2C gene family has been systematically characterized in G. hirsutum [16], a comprehensive analysis in its allotetraploid relative, G. barbadense, renowned for superior fiber quality but characterized by a distinct genetic background, has been lacking. This study provides a comparative evolutionary analysis of the PP2C family across four Gossypium species and, importantly, integrates multi-omics data to identify members associated with key agronomic traits, including stress resilience, elite fiber properties, and early maturity, thereby offering novel insights and genetic resources for G. barbadense improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of the PP2C Gene Family in Four Cotton Genomes

The whole-genome sequences of four cotton species, G. barbadense (HAU), and G. hirsutum (HAU), G. arboreum (CRI), and G. raimondii (JGI), were downloaded from the CottonGen database (https://www.cottongen.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025)) [17]. A total of 76 known Arabidopsis PP2C protein sequences were retrieved from the TAIR website (http://www.Arabidopsis.org/ (accessed on 2 September 2025)) and used as queries to perform local BLASTP and BLASTN searches against the genomic databases of the four cotton species. An E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5 was applied to identify initial candidate PP2C genes. To further verify the presence of the conserved PP2C domain, all candidate protein sequences were subjected to a second screening using the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles of the PP2Cc domain (PF00481 and PF07228), which were obtained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2025)) [18]. This search was performed locally using the HMMER 3.4 with default E-value parameters.

2.2. Chromosomal Distribution, Gene Structure, Conserved Motifs of PP2C Genes

The chromosomal locations of all identified PP2C genes were mapped onto the four cotton genomes using TBtools v2.056 [19]. Conserved motifs were identified using the Multiple Expectation Maximization for Motif Elicitation (MEME) version 5.5.8 website (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme (accessed on 6 September 2025)), with the maximum number of motifs set to 10. Conserved protein domains were annotated using NCBI conserved domain database (CDD) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd (accessed on 8 September 2025)). All resulting gene structures, motifs, and domains were visualized using TBtools v2.056 [19].

2.3. Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localization of PP2C Family Members

Physicochemical properties, including the molecular weight (MW) and theoretical isoelectric point (pI), of the identified PP2C proteins were predicted using the Compute pI/Mw tool on the ExPASy online platform (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/ (accessed on 10 September 2025)) [20]. Subcellular localization predictions were performed using the WoLF PSORT tool (https://www.genscript.com/wolf-psort.html (accessed on 14 September 2025)) and TargetP-2.0 software (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TargetP-2.0/ (accessed on 16 September 2025)), which analyzes amino acid sequences for the presence of targeting signals indicative of specific cellular compartments.

2.4. Phylogenetic and Functional Protein Network Analyses of PP2C Family Members

The phylogenetic tree was inferred using Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 11, following multiple sequence alignment of the PP2C proteins with ClustalW [21]. The Poisson correction model was selected, and the robustness of the tree topology was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The final phylogenetic tree was visualized and annotated using the online tool Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6.7.6 (https://itol.embl.de/ (accessed on 15 October 2025)). Protein–protein interactive network prediction, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed using STRING version 12.0 (https://cn.string-db.org/ (accessed on 13 October 2025)).

2.5. Expression Analysis of PP2C Family Members

For biotic-stress-related genes, fold-change values of differential expression genes from hypocotyls of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (Fov)-infected Fov7_knockout (KO)#5 versus J668 at 5 and 10 days post-inoculation (dpi) were retrieved [22]. For abiotic-stress-related genes, transcript per lilobase per million mapped reads (TPM) values of PP2C genes from G. barbadense cultivar H7124 treated by cold, heat, drought, and salt for 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h were also retrieved from the CottonMD database (https://yanglab.hzau.edu.cn/CottonMD (accessed on 17 September 2025)) [23]. For fiber-quality-related genes, fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped (FPKM) values of PP2C genes from different fiber developmental stages of G. barbadense cultivar XH37 (high fiber strength), XH58 (long fiber), XH33 (low lint percentage), LuoSaiNa (low fiber strength) and AShi (short fiber and high lint percentage) were retrieved [1]. For early-maturation-related genes, FPKM values of PP2C genes from shoot apical meristem (SAM) and flower mixture of early- and late-maturation G. barbadense cultivars were retrieved (unpublished). Differentially expressed genes were identified using adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 and |log2(fold change)| > 1. Expression levels were visualized in the form of a heatmap generated using R.

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification of the PP2C Gene Family in Four Cotton Species

To identify PP2C family members in cotton, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using the sequences of 76 Arabidopsis PP2C proteins (TAIR, http://www.arabidopsis.org/ (accessed on 2 September 2025)), which were classified into ten subfamilies (A–J) and six singles (Table S1). These protein sequences were used as queries for local BLASTP and BLASTN searches against the protein and genomic databases of G. barbadense (AD2), G. hirsutum (AD1), G. arboreum (A2), and G. raimondii (D5). A stringent E-value cutoff of <1 × 10−5 was applied to generate an initial set of candidate PP2C genes. For further validation, the hidden Markov models (HMMs) of the PP2C protein domain (Pfam: PF00481 and PF07228) were downloaded from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2025)), and used to scan the predicted protein datasets of the four cotton species via the HMMER software package. Candidates were retained only if they contained a complete PP2C domain with a length exceeding 100 amino acids and an E-value < 1 × 10−5. This rigorous process finally identified 105, 105, 204, and 152 putative PP2C genes in G. arboreum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, and G. barbadense, respectively (Table S2).

3.2. Chromosomal Distribution of PP2C Genes in Four Cotton Genomes

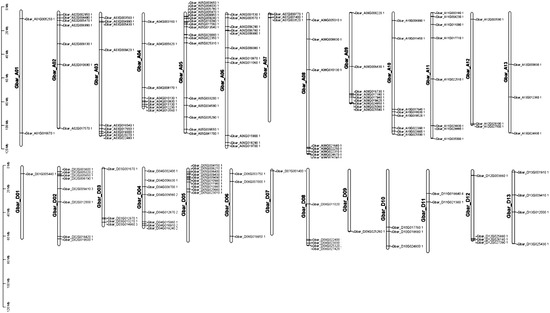

Chromosomal location analysis revealed that the 152 identified G. barbadense PP2C genes were unevenly distributed across all 26 chromosomes. The highest gene densities were observed on chromosomes A05 and D05, harboring 17 and 10 genes, respectively (Figure 1). Similarly, in G. hirsutum, all 204 PP2C genes were mapped to 26 chromosomes, with a notable abundance on chromosomes A05 and D05, involving 16 and 12 genes, respectively; the presence of numerous gene clusters in the G. hirsutum genome suggests that tandem duplication events have played a significant role in the expansion of the PP2C family in this species (Figure S1). In the diploid progenitors, the 105 G. arboreum (A2) PP2C genes were also predominantly located on chromosome Chr05, which contained 13 genes (Figure S2). Likewise, in G. raimondii (D5), the 105 PP2C genes were distributed across the chromosomes with the highest concentrations on chromosomes Chr05 that contained 13 genes (Figure S3). The strikingly similar distribution patterns between tetraploids G. barbadense, G. hirsutum and their diploid ancestors are likely attributable to evolutionary conservation, yet with divergent gains and losses in At and Dt subgenomes of G. barbadense and G. hirsutum.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution of PP2C genes in G. barbadense. The map was generated using TBtools [19].

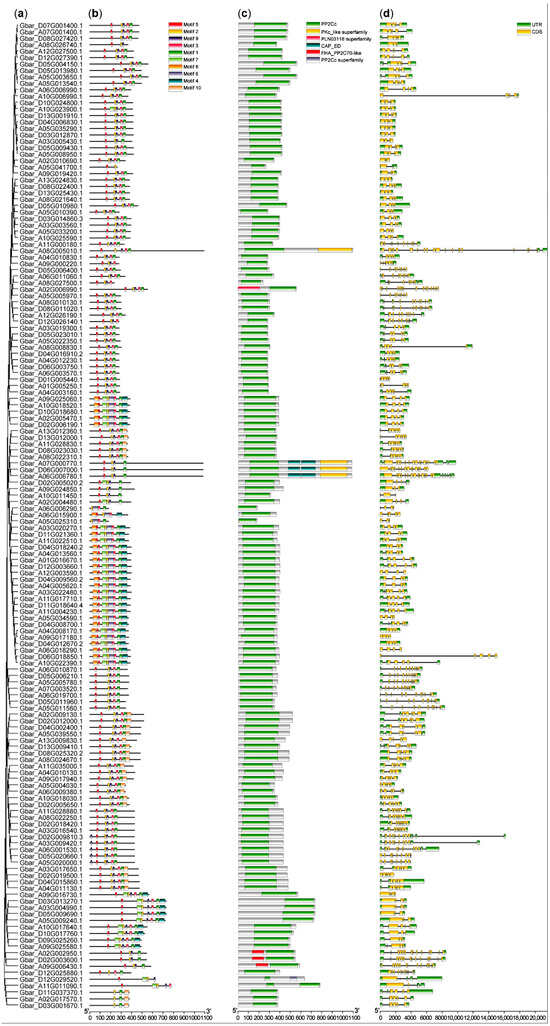

3.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of PP2Cs in Four Cotton Species

To investigate the structural conservation and divergence of cotton PP2C gene family during evolution, we analyzed the gene structures and conserved protein motifs of the identified members in G. barbadense (AD2), G. hirsutum (AD1), G. arboreum (A2), and G. raimondii (D5). Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on coding sequence (CDS) and DNA sequences, and the corresponding gene structure and motif composition diagrams were generated (Figure 2 and Figures S4–S6).

Figure 2.

Gene structure and motif composition of PP2Cs in G. barbadense. (a) Phylogenetic grouping. The tree was constructed using MEGA 11 [21]. (b) Conserved motifs. On the right side, the top group of icons represent conserved motifs (motif 1–10) predicted by the MEME website. (c) PP2C domains. The middle group of icons denote six conserved PP2C protein related domains annotated using NCBI-CDD website. (d) Gene structure. The last two icons at the bottom represent gene structures, UTR and CDS. All above were visualized using TBtools [19].

Comparative analysis of exon-intron structures revealed significant diversity among PP2C genes. While most G. arboreum PP2C genes lacked untranslated regions (UTR) (Figure S5), genes in the other three species often contained UTR at both ends of the sequences (Figure 2, Figures S4 and S6). Furthermore, the number of exons varied considerably among different PP2C genes.

Conserved motif prediction using MEME version 5.5.8 software identified ten distinct motifs. Motif 1 was present in all four species and was found to overlap with the critical PP2Cc domain (PF00481), the primary functional region for phosphatase activity. The core sequence of this motif was identified as LTPEDEFLILASDGLWDVLSNZEAVDIVR (located between approximately 146–366 bp in the alignment). A combination of motifs 1, 2, 5, and 6, predominantly located in the central part of the proteins, forms a conserved domain of approximately 60 amino acid residues characteristic of the PP2C family. Notably, motif 5 was found in 98% and 96.6% of PP2C proteins in G. barbadense and G. hirsutum, respectively. Similarly, Motif 6 was present in 97% of G. barbadense PP2Cs and 100% of G. hirsutum PP2Cs. The high conservation and specific combination of these motifs suggest they are essential for the specific protein dephosphorylation functions of this gene family.

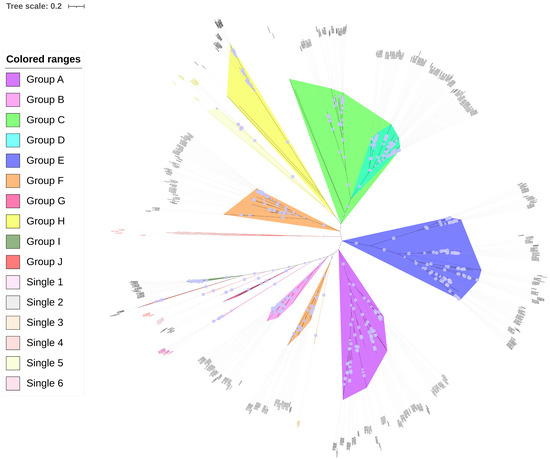

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of PP2C Genes in Gossypium

To investigate the evolutionary relationships of the PP2C gene family in Gossypium, a phylogenetic analysis was performed using the protein sequences of Arabidopsis PP2C proteins as an outgroup. Multiple sequence alignment was conducted with ClustalW, and the resulting alignment was used to construct a phylogenetic tree via the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 11.0 software. The Poisson correction was applied, and branch support was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Phylogenetic analysis grouped PP2C genes from G. barbadense (152), three other cotton species (G. hirsutum, 204; G. arboreum, 105; G. raimondii, 105), and Arabidopsis (76) into ten major clades (A–J) and six single clusters (Figure 3), indicating evolutionary conservation with cotton species and across different plant species. Most clades were monophyletic, except that clade F was divided into two distinct sections. Notably, Single 2 (containing AT1g75010) formed an outmost branch, while Single 3 (containing AT2g40860) was closely related to clade F, and Single 5 (containing AT4g11040) clustered near clade H. These clustering features suggest that the conventional 10-subfamily classification may warrant refinement in cotton, potentially expanding to up to 15 groups (Arranged clockwise in the circle diagram as: Single 2, F1, H + Single 5, C, D, E, A, F2 + Single 3, B, Single 1, G, Single 6, Single 4, J, I). Additionally, Single 1 (with AT5g19280) was positioned between clades B and G, whereas Singles 4 (AT4g27800) and 6 (AT1g18030) lay between clades G and J. Given their close phylogenetic relationships, these smaller groups (Single 1, G, Single 6, Single 4, J) could be consolidated, leading to a reduction in the total group number.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of PP2C proteins from G. barbadense and Arabidopsis. Bootstrap support values from 1000 replicates are shown by light blue dots on the branches. The larger the dot, the higher the bootstrap value. The tree was built and visualized using MEGA 11 and iTOL software.

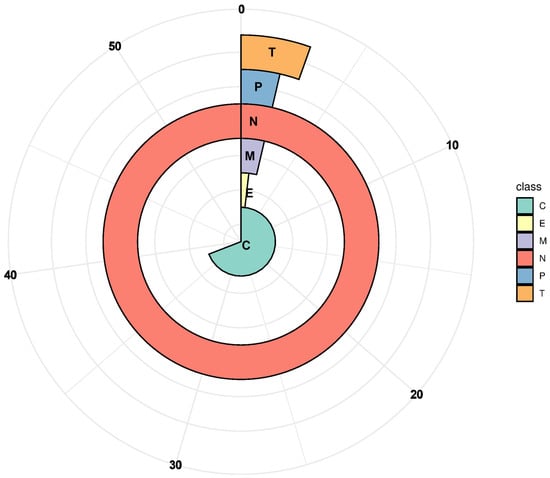

3.5. Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localization of PP2Cs in G. barbadense

The physicochemical properties of the 152 identified G. barbadense PP2C proteins were analyzed using the ExPASy online tool. The protein lengths ranged from 179 to 1091 amino acids, with predicted molecular weights varying between 20.30 and 121.45 kDa and theoretical isoelectric points ranging from 4.53 to 9.36 (Table S3). Subcellular localization predictions performed with WoLF PSORT indicated that the majority of GbPP2C proteins are predominantly localized to the nucleus and chloroplasts (Figure 4, Table S3).

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of PP2Cs in G. barbadense. N, nucleus; C, chloroplast; M, mitochondria; T, cytosol; E, endoplasmic reticulum; P, plastid membrane. Subcellular localizations were predicted and visualized using TargetP-2.0 and R-4.5.2 softwares.

3.6. Protein Interaction Networks and Functional Enrichment of GbPP2Cs

To explore the functional associations of the PP2C proteins in G. barbadense, we predicted protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks and performed Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses. Based on homology with G. hirsutum PP2C proteins, only one interactive pair was identified, namely, LOC107901268 (red, Gbar_A06G006780) and LOC107930842 (green, Gbar_A07G000770) (Figure S7). In contrast, analysis using A. thaliana homologs reveled three distinct networks associated with specific functional pathways: protein dephosphorylation (red, 18 PP2Cs), peptidyl-threonine dephosphorylation (green, 6 PP2Cs), and small network composed of “F17I5.110 and PAPP2C” (blue, 2 PP2Cs) (Figure S8). This discrepancy highlights the need for further experimental validation to elucidate the functional protein interactions of PP2Cs in cotton.

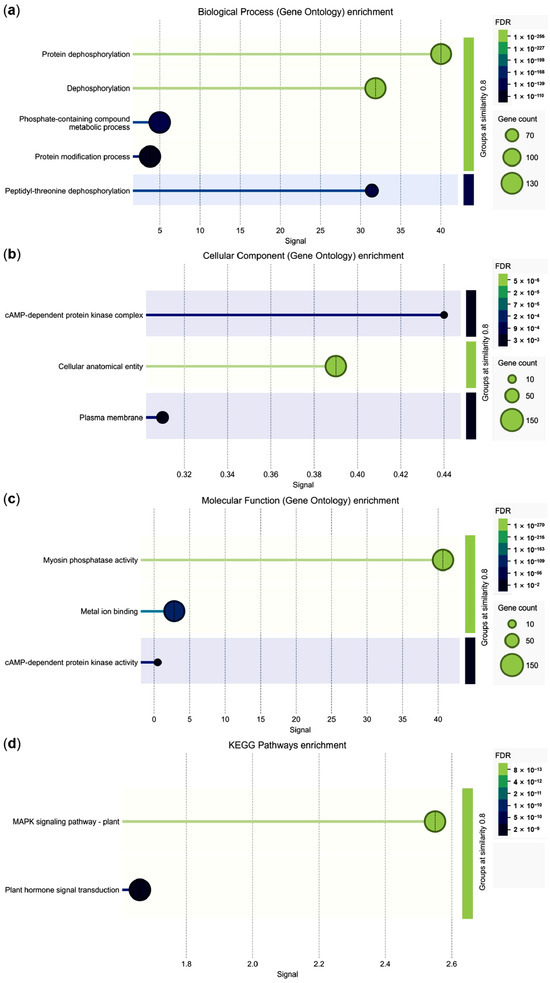

Functional enrichment analysis demonstrated that GbPP2Cs were most strongly associated with protein dephosphorylation in the biological process category (Figure 5a). For cellular components, they were significantly enriched in the cAMP-dependent protein kinase complex (Figure 5b). Molecular function analysis indicated that most GbPP2Cs possess myosin phosphatase activity (Figure 5c). Notably, a subset of 15 GbPP2C members showed concurrent enrichment in both the plant MAPK signaling pathway and plant hormone signal transduction, with particularly strong signals in the former (Figure 5d; Table S4). These findings provide valuable insights for further functional characterization of GbPP2Cs in these key signaling pathways.

Figure 5.

Functional enrichment analysis of GbPP2C proteins. (a) Biological process GO terms. (b) Cellular component GO terms. (c) Molecular function GO terms. (d) KEGG pathway enrichment. False discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05. The x-axis “Signal” represents the weighted harmonic mean of -log(FDR) and the observed/expected ratio. Signal > 0.01. GO and KEGG enrichment were analyzed and visualized using STRING software.

3.7. Screening of GbPP2C Genes Related to Stress Resistance

Given the documented roles of PP2C members in plant disease resistance, we investigated which GbPP2Cs are associated with disease responses in G. barbadense. To identify genes involved in fungal resistance, we used RNA-seq data from hypocotyl tissues of G. hirsutum accession J668 following inoculation with Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum (Fov) [22]. Knocking out Fov7 gene resulted in G. hirsutum lines (including KO#5) extremely susceptible to Fov race 7 [22], suggesting that Fov7 is a positive regulator of Fusarium wilt (FW) resistance in cotton. Comparison between the susceptible Fov7-knockout line Fov7_KO#5 and the resistant genotype J668 at 10 days post-inoculation revealed four homologous GbPP2C genes (Gbar_A04G010130, Gbar_A09G017940, Gbar_A13G012360, and Gbar_D13G012000) that were significantly down-regulated in the susceptible Fov-infected Fov7_KO#5 line (Table 1). Therefore, we speculated that these four GbPP2Cs are also potential positive regulators of FW resistance.

Table 1.

Downregulated GbPP2Cs in hypocotyls of Fov-infected Fov7_KO#5 versus J668 at 10 dpi.

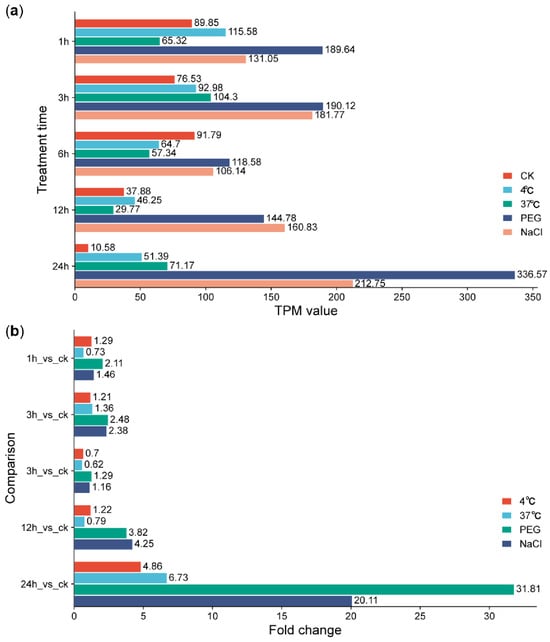

We further explored the involvement of GbPP2Cs in abiotic stress responses using expression data from G. barbadense accession H7124 subjected to cold, heat, drought, and salt treatments over a 24 h time course (0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h) [23]. Phylogenetic analysis identified three distinct clades of GbPP2Cs preferentially induced by cold (48 genes), heat (12 genes), or both drought and salt (11 genes) (Figure S9a). Among these, Gbar_D02G005650 emerged as a prominent candidate, showing markedly elevated expression levels under both drought (PEG) and salt (NaCl) stress, especially at 24 h (Figure S9b and Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Expression level (a) and change fold (b) of GbPP2C gene Gbar_D02G005650 after cold (4 °C), heat (37 °C), drought (PEG), and salt (NaCl) treatments in G. barbadense accession H7124. Expression levels were visualized using R software.

3.8. Identification of Candidate GbPP2Cs Associated with Fiber Development

G. barbadense is a major source of premium natural fibers due to its excellent fiber quality. Therefore, we sought to identify specific GbPP2C genes involved in fiber development. RNA-seq was performed on fibers at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days post-anthesis (DPA) from five G. barbadense accessions with contrasting fiber traits: XH37 (high strength), XH58 (long fiber), XH33 (low lint percentage), LuoSaiNa (low strength), and AShi (short fiber, high lint percentage) [1].

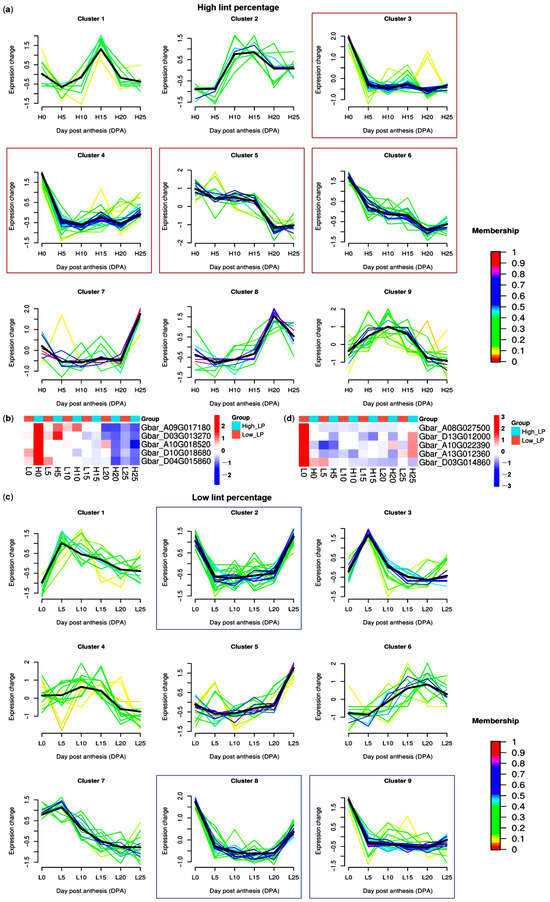

Fiber initiation stage (especially 0 DPA) is vital for lint formation. Here, we first performed mfuzz time series analysis of GbPP2C genes during different fiber development stages of high-lint-percentage G. barbadense accession. 96 GbPP2Cs highly expressed in 0 DPA were retrieved (clusters 3–6; Figure 7a). Among these, five genes (Gbar_A09G017180, Gbar_D03G013270, Gbar_A10G018520, Gbar_D10G018680, and Gbar_D04G015860) showed the highest expression and a fold change more than 2 at 0 DPA of high-lint-percentage genotype than low one (Figure 7b). Conversely, we obtained another five genes (Gbar_A08G027500, Gbar_D13G012000, Gbar_A10G022390, Gbar_A13G012360, and Gbar_D03G014860) with highest expression and more than 2 fold-change expression difference at 0 DPA of low lint-percentage (LP) accession (clusters 2, 8, 9; Figure 7c,d), suggesting roles as potential negative regulators of lint percentage. Notably, two genes (Gbar_D13G012000 and Gbar_A13G012360) were also identified as potential positive regulators of FW resistance, implying the negative correlation between yield and disease resistance.

Figure 7.

Identification of GbPP2C genes related to lint percentage (LP). (a) Mfuzz time series of GbPP2C genes during different fiber development stages of high-lint-percentage G. barbadense accession. Red boxes highlighted the candidates that positively regulated lint percentage. (b) Expression levels (z-scored FPKM values) of five potential LP-positive-regulator GbPP2Cs during different fiber development stages between low- and high-lint-percentage G. barbadense accessions. (c) Mfuzz time series of GbPP2C genes during different fiber development stages of low-lint-percentage G. barbadense accession. Blue boxes highlighted the candidates that negatively regulated lint percentage. (d) Expression levels (z-scored FPKM values) of five potential LP-negative-regulator GbPP2Cs during different fiber development stages between low- and high-lint-percentage G. barbadense accessions. Mfuzz time series and expression heatmaps were visualized using R software.

A similar strategy was adopted to mine the candidate GbPP2C genes regulating fiber length and strength, with highest expression at 5–20 and 25 DPA stages, respectively. For fiber length (FL), ten GbPP2C genes (Gbar_D13G025430, Gbar_A13G024830, Gbar_A09G019420, Gbar_A08G026740, Gbar_A07G001400, Gbar_D07G001400, Gbar_A11G004230, Gbar_D08G027420, Gbar_A06G001530, and Gbar_D05G020660) exhibited peak expression at 5 DPA and were identified as potential positive regulators of fiber length (Figure S10a,e). In contrast, five potential negative regulators (Gbar_A05G004030, Gbar_A09G000220, Gbar_A03G005430, Gbar_D03G012870, and Gbar_A05G005780) showed maximal expression at 15 and 20 DPA (Figure S10b,f). Amongst, we found three potential FL positive regulators (Gbar_A09G019420, Gbar_D07G001400, and Gbar_D08G027420) and one potential FL negative regulators (Gbar_D03G012870) that were enriched in two pathway, MAPK signaling pathway-plant and plant hormone signal transduction (Table S4), implying these genes might regulate FL via tuning MAPK and hormone signals. Regarding fiber strength (FS), only one positive regulator, Gbar_A03G005430 (annotated as GbAIP1, encoding an AKT1-interacting phosphatase 1), met the criteria (FPKM > 1, fold change > 2; Figure S10c,d,g). Intriguingly, GbAIP1 was also identified as a potential negative regulator of fiber length, indicating a potential trade-off between fiber length and strength. This expression trend was consistent across accessions with extreme fiber phenotypes (Figure S10f,g).

3.9. GbPP2C59 Might Negatively Regulate Early Maturity of G. barbadense

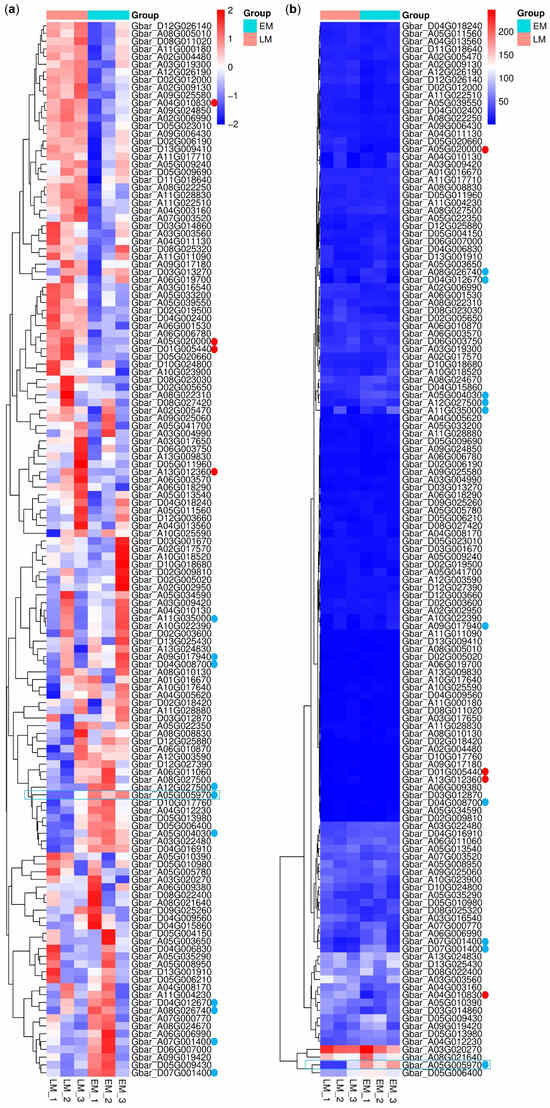

Given the roles of PP2C genes in various aspects of plant growth, we sought to identify specific PP2C family members potentially involved in regulating maturity in G. barbadense. This investigation aims to provide valuable genetic resources for breeding early-maturing cotton cultivars, a trait of particular importance for production in regions like Xinjiang. To this end, we conducted RNA-seq analyses on flowers and shoot apical meristems (SAM) from two G. barbadense accessions exhibiting extreme maturity phenotypes: the extremely late-maturity (LM) accession 5476-И (growth period: 137 days) and the extremely early-maturity (EM) accession KkH-8660 (growth period: 121 days). Gene expression levels were quantified and normalized as FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million mapped reads) values.

Among the 152 identified G. barbadense PP2C (GbPP2C) genes, 137 were reliably expressed (FPKM > 0) in the sampled tissues and thus retained for subsequent differential expression analysis. Comparative analysis between LM and EM accessions revealed 45 GbPP2C genes exhibiting higher expression in the LM accession (putative positive regulators of maturity), of which four genes showed a |log2(Fold Change)| > 1 with statistical significance (Figure 8, red dots). Conversely, 92 GbPP2C genes displayed higher expression in the EM accession (putative negative regulators of maturity), with ten of these genes exhibiting a |log2(Fold Change)| > 1 (Figure 8, blue dots).

Figure 8.

Expression profile of GbPP2C genes in LM and EM G. barbadense accessions. (a) Z-scored FPKM values. (b) Raw FPKM values. Dots, |log2(fold change)| > 1; blue, negative; red, positive. Blue box, the optimal negative candidate for maturity regulation of G. barbadense. Expression heatmaps were visualized using R software.

Notably, the gene Gbar_A05G005970, annotated as encoding a probable protein phosphatase 2C 59 (named GbPP2C59), emerged as a particularly strong candidate. It displayed the most substantial difference (|log2(fold change)| = 1.89, p = 0.000195) among the differentially expressed PP2Cs and was also characterized by relatively high expression abundance across the dataset (Figure 8, highlighted by blue box). Its significant upregulation in the early-maturity accession suggests a potential negative regulatory role in delaying maturation, making it a high-priority target for further functional validation studies aimed at manipulating maturity timing in G. barbadense.

4. Discussion

4.1. Expansion, Losses, and Conservatism of Cotton PP2C Gene Family During Evolution

Cotton is a classic example of an allotetraploid plant and serves as an excellent model for studying evolutionary analysis and polyploidization processes [24]. The PP2C gene family has been previously identified and characterized in several plant species, including Arabidopsis [5], rice [4], maize [25], Brachypodium [26], and banana [27]. While previous studies on the PP2C gene family in Gossypium species exist, our study employed distinct and more domain models, resulting in the identification of a larger repertoire of PP2C genes compared to prior report (147, 181, 87, and 99) [16]. In comparison, our study identified 152, 204, 105, and 105 PP2C genes in G. barbadense (AD2), G. hirsutum (AD1), G. arboreum (A2), and G. raimondii (D5) respectively. Given that the D5 and A2 genomes are considered putative donors of the allotetraploid cottons, the differences in gene numbers suggest that the PP2C gene family has undergone significant expansion from diploids to tetraploids. Furthermore, the variation in gene numbers between G. barbadense/G. hirsutum and the sum of diploid ancestors (G. arboreum and G. raimondii) implies that different degrees of gene losses have occurred during tetraploid formation and divergency. Additionally, our conserved motif analysis revealed that most PP2C proteins contain motifs 1, 5, and 6, confirming that all identified members exhibit typical family characteristics. Exon-intron organizations unveiled that PP2C genes within the same subgroup tend to exhibit similar gene structures. Our comprehensive phylogenetic analysis, which included PP2Cs from four cotton species and Arabidopsis, resolved the gene family into 15 distinct groups, thereby establishing a more detailed and robust classification system than was previously possible using only G. hirsutum and Arabidopsis sequences [16]. Protein functional enrichment analyses confirmed their shared role in protein dephosphorylation, together implying a broad conservation of core PP2C functions during the evolution of different plant species.

4.2. PP2C-Mediated Biotic and Abiotic Stress Adaptation in G. barbadense

The PP2C gene family, as the largest group of protein phosphatases in plants, serves as a key regulator of dephosphorylation events in various signaling pathways, including those involved in disease responses [9]. Previous studies have established their importance in plant immunity. In Arabidopsis, double mutants lacking AtPP2C62 and AtPP2C26 exhibited reduced disease symptoms and suppressed bacterial multiplication upon infection with Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae [28]. Similarly, three Arabidopsis PP2Cs (HAI1, HAI2, and HAI3) were essential for ABA-mediated MPK3/MPK6 inactivation and immune suppression [10]. In G. barbadense, we previously identified a disease-resistance gene GbPP2C80 that interacted with GbWAKL14 to negatively co-regulate resistance to Fusarium and Verticillium wilt through MPK3 and ROS signaling [3]. In upland cotton (G. hirsutum), a major-effect loci, Fov7, was identified as a positive FW-resistance regulator [22]. The present study further identified four GbPP2C genes as potential positive regulators of FW resistance, based on their significant down-regulation in the susceptible Fov7-knockout line compared to the resistant genotype J668 at 10 days post-inoculation. The shared GO annotation of these four genes in protein dephosphorylation suggests a potential mechanism whereby they contribute to disease resistance through the dephosphorylation of key signaling components, such as MPKs.

Beyond biotic stress, PP2Cs are crucial mediators of abiotic stress adaptation, such as drought, salt, cold, and hot, etc. In G. hirsutum, PP2C protein GhDRP1 has been reported to function as a negative regulator of drought tolerance through ABA and flavonoid metabolism [11]. Similarly, GhHAI2, GhAHG3, and GhABI2 also negatively modulated osmotic stress via ABA pathway [29]. Furthermore, 30 GhPP2C genes were induced by different abiotic stresses, including heat, cold, drought, and salt [16]. However, the role of PP2Cs in abiotic stress adaptation in G. barbadense remained unexplored. Herein, our expression profiling of G. barbadense under cold, heat, drought, and salt treatments revealed 48, 12, and 11 GbPP2C genes preferentially induced by cold, heat, and both drought/salt stresses, respectively. Notably, Gbar_D02G005650 exhibited consistently elevated expression under all four stress conditions, particularly under PEG and NaCl treatments, highlighting its potential as a pleiotropic regulator for multi-stress tolerance breeding. Given the established role of PP2C-mediated ABA signaling in abiotic stress responses, it is plausible that the identified candidate gene modulates abiotic stress tolerance in G. barbadense through a similar regulatory pathway.

4.3. Roles of PP2Cs in Fiber Morphogenesis and Growth Regulation of G. barbadense

Although previous transcriptomic analyses in upland cotton revealed expression patterns of PP2Cs during fiber development [16], specific regulators of fiber traits remained unidentified. Our systematic screening using RNA-seq data from multiple developmental stages of G. barbadense accessions with extreme fiber performance identified potential GbPP2C regulators for lint percentage, fiber length and strength [1]. We discovered five potential positive and five potential negative GbPP2C regulators of lint percentage, among which two negative ones (Gbar_D13G012000 and Gbar_A13G012360) also function as potential positive regulators of FW resistance, suggesting their potential for balancing yield and disease resistance. For fiber length, ten GbPP2Cs were characterized as potential positive regulators and five as potential negative regulators. Notably, three positive (Gbar_A09G019420, Gbar_D07G001400, and Gbar_D08G027420) and one negative (Gbar_D03G012870) regulators of fiber length might function through MAPK and hormone signaling pathways. Similarity, silencing GhKRP6 (a cotton cell cycle-dependent kinase inhibitor) caused differential expression of genes related to cell wall biosynthesis, MAPK, and plant hormone transduction pathways—all of which are related to cell expansion [30]. Notably, Gbar_A03G005430 (GbAIP1) was identified as a positive regulator of fiber strength but a negative regulator of fiber length, indicating its role as a key hub gene coordinating these two critical quality attributes. Currently, no direct evidence links AIP1 genes to cotton fiber development. The sole functional report on AIP1 indicates its role in regulating ammonium transport by dephosphorylating AMMONIUM TRANSPORTER 1 (AMT1) proteins [31]. Expanding to the broader context of protein phosphatases in fiber development, previous studies show that Protein Phosphatase 2A (PP2A) influences fiber length by modulating end-binding protein 1C (GhEB1C) to regulate microtubule dynamics [32]. Additionally, Leafy Cotyledon1-Like 1 (GhL1L1) activates PHOSPHATASE 2AA2 (GhPP2AA2), which subsequently regulates GhPIN1 activity to determine cell fate specification [33]. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that AIP1 may influence fiber development through potential roles in ammonium transport, microtubule dynamics, and auxin distribution.

Beyond their roles in stress responses, PP2Cs actively participate in regulating various aspects of plant growth and development [9]. For instance, silencing of SlPP2C in tomato significantly delayed senescence and ripening in leaves, flowers, and fruits; although inducible by ethylene (ETH) and ABA, SlPP2C did not appear to interact directly with ABA receptors [14]. In Brassica juncea, BjuPP2C52 expression increased during reproductive growth stages, where it interacted with photoperiod regulator BjuFKF1 and seven other proteins to fine-tune flowering time [15]. Similarly, in upland cotton, higher expression of ABA-related PP2Cs genes correlated with lower plant height, and higher auxin and ABA levels, in a dwarf mutant of G. hirsutum [34]. Furthermore, GhPP2C1-5 genes may contribute to dwarfing regulated by Ammopiptanthus mongolicus C-repeat binding factor 1 (AmCBF1), and silencing of GhPP2C1/2 in R15 impaired cotton growth [35]. Despite these documented roles, the function of PP2Cs in regulating growth period in G. barbadense remained unexplored. Our comparison of extreme early- and late-maturity G. barbadense accessions identified Gbar_A05G005970 (GbPP2C59), which exhibited higher expression in early-maturity accession, suggesting it acted as a negative regulator of growth period. We hypothesize that GbPP2C59 may promote early maturation by modulating key signaling pathways, potentially through dephosphorylation of kinases in the ABA signaling cascade to release growth inhibition, and/or by regulating components of the photoperiod pathways to accelerate the vegetative-to-reproductive transition.

While our in silico analyses provide comprehensive insights into the PP2C gene family in G. barbadense, it is important to note that these predictions require experimental validation. Future work should include functional studies such as gene knockout/knockdown experiments, protein–protein interaction assays, and detailed phenotypic characterization under stress conditions to confirm the roles of the candidate genes identified in this study.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive genome-wide analysis of the PP2C gene family in G. barbadense, identifying 152 members that exhibit remarkable evolutionary conservation and lineage-specific expansion. Through systematic phylogenetic, structural, interactive network, functional enrichment, and expression analyses, we have elucidated the functional diversification of GbPP2Cs in regulating key agronomic traits. We identified multiple GbPP2Cs responsive to both biotic and abiotic stresses, including four genes associated with FW resistance and one gene (Gbar_D02G005650) showing induction under drought, salt, and temperature stresses at the same time. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that specific GbPP2Cs showed preferential expression during critical stages of lint initiation, fiber elongation, and secondary cell wall thickening. Particularly noteworthy is the discovery of pleiotropic regulators such as Gbar_A03G005430 (GbAIP1), which appears to coordinate the trade-off between fiber length and strength, and Gbar_D13G012000 and Gbar_A13G012360, which may simultaneously regulate lint percentage and disease resistance. Additionally, we also identified GbPP2C59 as a potential negative regulator of maturity in G. barbadense. These findings substantially expand our understanding of the PP2C family in cotton and provide valuable genetic resources for molecular breeding programs aimed at developing cotton varieties with enhanced stress resilience, superior fiber quality, and earlier maturity. Future research should focus on functional validation using approaches such as CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing, VIGS (virus-induced gene silencing), and transgenic overexpression in model plants and cotton. For breeding applications, the pleiotropic regulators identified in this study offer exciting possibilities, for instance, developing tissue-specific or inducible promoters to fine-tune GbAIP1 expression for optimal fiber quality, or pyramiding positive resistance regulators like Gbar_D13G012000 through marker-assisted selection to enhance multi-stress resilience without compromising yield.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb47120977/s1, Table S1: Information of Arabidopsis PP2Cs; Table S2: PP2C family members in four cotton species; Figure S1: Chromosomal distribution of PP2C genes in G. hirsutum; Figure S2: Chromosomal distribution of PP2C genes in G. arboreum; Figure S3: Chromosomal distribution of PP2C genes in G. raimondii; Figure S4: Gene structure and motif composition of PP2Cs in G. hirsutum; Figure S5: Gene structure and motif composition of PP2Cs in G. arboreum; Figure S6: Gene structure and motif composition of PP2Cs in G. raimondii; Table S3: Characteristics of PP2C genes in G. barbadense; Figure S7: Predicted protein–protein interactive networks of GbPP2Cs according to their homologous proteins in G. hirsutum; Figure S8: Predicted protein–protein interactive networks of GbPP2Cs according to their homologous proteins in A. thaliana; Table S4: KEGG enrichment of GbPP2Cs; Figure S9: Expression level of GbPP2C genes after cold (4 °C), heat (37 °C), drought (PEG), and salt (NaCl) treatments in G. barbadense accession H7124; Figure S10: Identification of GbPP2C genes related to fiber quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.Z. and J.K.; methodology, software, and formal analysis, N.Z.; resources, Z.Z., M.W., C.L., L.R., Y.L., J.L., Y.W. and Y.D.; data curation, J.Z., Z.L. and J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Z.; writing—review and editing, N.Z.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, N.Z. and J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Project of Fund for Stable Support to Agricultural Sci-Tech Renovation (xjnkywdzc-2025003-02-1), the Science and Technology Innovation Leading Talent Project-High Level Leading Talents for Alifu Aierxi (2022TSYCLJ0048), the Project of Fund for the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Tianchi Talent-Young Doctor for Nan Zhao (Gene mining and functional dissection of growth period in Sea Island cotton), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32401900), and the project of Arid Region Xinjiang Agriculture Xinjiang Research Institute (Hqny-2025002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. The raw data of fiber transcriptome sequencing can be obtained on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) website, with the accession number GSE184965. Further inquiries can be directed to the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the editors for processing the manuscript and to the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, N.; Wang, W.R.; Grover, C.E.; Jiang, K.Y.; Pan, Z.X.; Guo, B.S.; Zhu, J.H.; Su, Y.; Wang, M.; Nie, H.S.; et al. Genomic and GWAS analyses demonstrate phylogenomic relationships of Gossypium barbadense in China and selection for fiber length, lint percentage, and Fusarium wilt resistance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Ni, Z.; Wang, Y. Identification of the full-length GbERD7 gene family in Gossypium barbadense and functional analysis of the role of the GbERD7g gene in drought and salt tolerance. Plant Sci. 2025, 360, 112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Guo, A.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, K.; Aierxi, A.; Wang, B.; Adjibolosoo, D.; et al. GbPP2C80 interacts with GbWAKL14 to negatively co-regulate resistance to Fusarium and Verticillium wilt via MPK3 and ROS signaling in Sea Island cotton. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2309785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Giri, J.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K.; Pandey, G.K. Protein phosphatase complement in rice: Genome-wide identification and transcriptional analysis under abiotic stress conditions and reproductive development. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerk, D.; Bulgrien, J.; Smith, D.W.; Barsam, B.; Veretnik, S.; Gribskov, M. The complement of protein phosphatase catalytic subunits encoded in the genome of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 908–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweighofer, A.; Hirt, H.; Meskiene, I. Plant PP2C phosphatases: Emerging functions in stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerk, D. Genome-scale discovery and characterization of class-specific protein sequences: An example using the protein phosphatases of Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007, 365, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J. Mutational analysis of protein phosphatase 2C involved in abscisic acid signal transduction in higher plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, H.; Qamer, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A. The multifaceted roles of PP2C phosphatases in plant growth, signaling, and responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, A.; Berens, M.L.; Nobori, T.; Anver, S.; Fukumoto, K.; Winkelmüller, T.M.; Takeda, A.; Becker, D.; Tsuda, K. Pathogen exploitation of an abscisic acid- and jasmonate-inducible MAPK phosphatase and its interception by Arabidopsis immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7456–7461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.B.; Wei, N.; Liu, Z.H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.B. A type-2C protein phosphatase (GhDRP1) participates in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) response to drought stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Qiu, X.; Chen, J.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, H.; Chen, F.; Gao, G. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the PP2C gene family in Apocynum venetum and Apocynum hendersonii. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Harshavardhini, R.K.; Murugan, N.; Keerthana, S.; Aispriya; Vinayaka; Ramaswamy, A.; Prabhakaran, J.; Ramaswamy, M. Comparative genomics and synteny analysis of PP2C phosphatases in modern and wild sugarcane cultivars for insights into abiotic stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1596800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Liu, W.; Qi, M.; Xu, T.; Wu, Y.; Li, T. Silencing SlPP2C expression delayed plant senescence and fruit ripening in tomato. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175, e13925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zuo, T.; Liu, Y.; Tao, H.; Mo, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, L.; Gao, J. Phylogenetic analysis of PP2C proteins and interactive proteins analyze of BjuPP2C52 in Brassica juncea. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 179, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazadee, H.; Khan, N.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, C.C.; Zeng, J.G.; Huang, Z.Y.; Wang, X.Y. Identification and expression profiling of protein phosphatases (PP2C) gene family in Gossypium hirsutum L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jung, S.; Cheng, C.-H.; Lee, T.; Zheng, P.; Buble, K.; Crabb, J.; Humann, J.; Hough, H.; Jones, D.; et al. CottonGen: The community database for cotton genomics, genetics, and breeding Research. Plants 2021, 10, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Chuguransky, S.; Williams, L.; Qureshi, M.; Salazar, G.A.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L.; Tosatto, S.C.E.; Paladin, L.; Raj, S.; Richardson, L.J.; et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D412–D419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Sanchez, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Appel, R.D.; Hochstrasser, D.F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999, 112, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Zhang, X.J.; Xiao, S.H.; Ma, J.; Shi, W.J.; Qin, T.; Xi, H.; Nie, X.H.; You, C.Y.; Xu, Z.; et al. A single-nucleotide mutation in a GLUTAMATE RECEPTOR-LIKE gene confers resistance to Fusarium Wilt in Gossypium hirsutum. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wei, L.; Liu, D. CottonMD: A multi-omics database for cotton biological study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D1446–D1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, A.H.; Wendel, J.F.; Gundlach, H.; Guo, H.; Jenkins, J.; Jin, D.; Llewellyn, D.; Showmaker, K.C.; Shu, S.; Udall, J.; et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature 2012, 492, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Pan, S. Maize protein phosphatase gene family: Identification and molecular characterization. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Jiang, M.; Li, P.; Chu, Z. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analyses of the PP2C gene family with their expression profiling in response to multiple stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Yan, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, J.; Miao, H.; Tie, W.; Ding, Z.; Ding, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; et al. The core regulatory network of the abscisic acid pathway in banana: Genome-wide identification and expression analyses during development, ripening, and abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto-Tomiyama, C.; Tanabe, S.; Kajiwara, H.; Minami, E.; Ochiai, H. Loss of chloroplast-localized protein phosphatase 2Cs in Arabidopsis thaliana leads to enhancement of plant immunity and resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris infection. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 2018, 19, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazadee, H.; Khan, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. GhHAI2, GhAHG3, and GhABI2 negatively regulate osmotic stress tolerance via ABA-dependent pathway in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 905181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Qanmber, G.; Liu, Z.; Xing, K.; Lu, L.; Liu, L.; Ma, S.; Li, F.; et al. Cell cycle-dependent kinase inhibitor GhKRP6, a direct target of GhBES1.4, participates in BR regulation of cell expansion in cotton. Plant J. 2023, 115, 1729–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras-Murillo, R.; Straub, T.; Anthoney, T.; Stein, L.; Ludewig, U.; Neuhäuser, B. PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE 1–LIKE 8 and AKT1 INTERACTING PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE 1 are involved in ammonium transport regulation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Feng, P.; Song, J.; Jia, B.; Yang, S.; Zhang, W.; Wu, M.; Pei, W.; et al. EB1C forms dimer and interacts with protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) to regulate fiber elongation in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Li, B.; Chen, L.; Min, L.; Zhang, X. GhL1L1 affects cell fate specification by regulating GhPIN1-mediated auxin distribution. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Gong, W.; He, S.; Pan, Z.; Sun, J.; Du, X. MicroRNA and mRNA expression profiling analysis revealed the regulation of plant height in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, C.; Su, X.; Cheng, H.; Guo, H. AmCBF1 transcription factor regulates plant architecture by repressing GhPP2C1 or GhPP2C2 in Gossypium hirsutum. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 914206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).