Abstract

Dexmedetomidine is a commonly used sedative because it has minimal adverse effects on respiratory function. Nevertheless, its cardiovascular safety profile, particularly bradycardia risk and drug–drug interactions (DDIs), remains incompletely understood. Additionally, current studies, including our previous analysis using the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS), hold several limitations. In this study, the electronic health record (EHR) platform TriNetX was utilized for pharmacovigilance analyses of dexmedetomidine. The significantly elevated incidence of bradycardia in dexmedetomidine-treated patients was demonstrated compared to other prevalent anesthetics. Age-stratified analyses revealed pronounced susceptibility in geriatric patients, while a slightly increased susceptibility in male patients was observed. In addition, elevated DDIs of dexmedetomidine with risperidone and albuterol were identified using disproportionality analysis with propensity score matching. Finally, to investigate molecular mechanisms of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia, analyses were conducted on a public microarray dataset, and nine differentially expressed miRNAs were identified following dexmedetomidine administration. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of target genes of all five up-regulated miRNAs revealed rhythmic process and muscle tissue development as potential explanations. Notably, the target genes of the up-regulated miRNAs miR-26a-5p and miR-30c-5p were significantly enriched in GO terms associated with bradycardia. Together, this study identified bradycardia as a significant adverse drug event (ADE) of dexmedetomidine administration, observed possible clinically meaningful DDIs with dexmedetomidine, demonstrated a greater risk in elderly patients, and provided transcriptomic evidence that miRNA-mediated pathway dysregulation may contribute to dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia.

1. Introduction

Dexmedetomidine, commercially available under the brand name Precedex, is a potent and highly selective α2-adrenergic receptor agonist [1,2]. Its pharmacological effects are mediated through suppression of sympathetic nervous system activity and inhibition of norepinephrine release, leading to a reduction in blood pressure and the induction of sedation [3]. Dexmedetomidine also demonstrates analgesic effects. Dexmedetomidine produces its pharmacological effects primarily through potent and highly selective activation of the α2-adrenergic receptor, with particularly strong affinity for the α2A subtype. Centrally, dexmedetomidine acts on α2-adrenergic receptors located in the locus coeruleus, resulting in suppression of noradrenergic neuronal firing and a corresponding reduction in sympathetic outflow [4]. This mechanism accounts for its distinctive sedative profile [5].

Clinically, dexmedetomidine is primarily indicated for procedural sedation [6], and is also utilized as an adjunct in the management of delirium, opioid-sparing strategies, and neuroprotection [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. For intensive care unit (ICU) sedation, the dosages are 1 mcg/kg IV over 10 min and 0.2–0.7 mcg/kg/h titration for maintenance. For procedural sedation, the dosages are 1 mcg/kg IV over 10 min and 0.6 mcg/kg/h titration for maintenance [14,15]. Since its approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999 [5], the use of dexmedetomidine has been increasing substantially, owing to its favorable sedation profile characterized by easy arousability and minimal impact on spontaneous respiration [16,17]. Dexmedetomidine exhibits approximately 1620:1 selectivity for α2-adrenergic receptors over the α1 isoform, thereby minimizing adverse respiratory effects [18,19]. In addition, dexmedetomidine pretreatment has exerted cardioprotective effects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [20,21]. Retrospective studies conducted in the United States have documented a marked increase in its utilization, with ventilated adult ICU use reaching 8.6% in 2020 [22], and pediatric ICU use increasing from 6.2% to 38.2% from 2007 to 2013 [23]. Moreover, dexmedetomidine is frequently co-administered with other sedatives, anesthetic agents to help maintain hemodynamic stability by decreasing the dose of other agents, and adjunctive medications [24,25,26], which amplifies the need for a comprehensive safety profile and careful evaluation of potential drug–drug interactions (DDIs) to ensure patient safety during polypharmacy sedation strategies.

Despite its therapeutic advantages and prevalence, dexmedetomidine use is restricted by its frequently reported adverse drug events (ADEs) and unclear safety profile. Notably, bradycardia is the most common side effect of dexmedetomidine across randomized trials and meta-analyses [22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Bradycardia, defined as a resting rate below 60 bpm in adults (and variably adjusted by age in pediatric patients), is the most encountered bradyarrhythmia in anesthesia and sedation contexts [35]. While often asymptomatic, bradycardia could escalate to significant hemodynamic compromise, potentially culminating in hypotension, syncope, cardiac arrest, or even death. A review of nearly 4000 anesthesia-related ADEs has reported that bradycardia was implicated in 25% of cases leading to cardiac arrest [36]. A clinical review found that bradycardia occurred in approximately 6.5 per 1000 procedural sedation settings [37]. Regarding dexmedetomidine, pediatric studies among mechanically ventilated children have reported a significantly elevated risk of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia (Odds ratio (OR) = 6.14, 95% CI: 2.20–17.12) compared to other sedatives [29]. Another meta-analysis has demonstrated an increased incidence of bradycardia (OR = 5.13, 95% CI: 0.96–27.47) after dexmedetomidine administration in post anesthesia care unit (PACU) patients [38]. However, most of the current systematic reviews and meta-analyses of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia are constrained by several methodological and contextual limitations that complicate inference and lead to divergent conclusions. First, much of the evidence arises from single-region or single-center cohorts and narrowly defined clinical settings (e.g., cardiac surgery, sedation in ICU, or pediatric imaging), limiting external generalizability [33,34,39]. Second, modest patient numbers or event counts reduce the statistical power to detect ADEs and contribute to imprecision [40,41]. For example, several studies reported large deviations with sometimes insignificance for the OR of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia [38]. Third, for real-world observational studies, heterogeneity of populations in exposed and control groups for comparison could lead to bias and distort the relationship between exposure and outcomes. Lastly, the lack of a DDIs’ safety profile of dexmedetomidine in current studies underscores the need for a systematic assessment of the co-administration of dexmedetomidine with other agents on cardiovascular effects.

Our previous work, entitled “The Association Between Dexmedetomidine and Bradycardia: An Analysis of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Data and Transcriptomic Profiles”, employed a multidisciplinary approach that integrated pharmacovigilance and transcriptomic analyses [30]. Bradycardia was demonstrated as the most frequent ADE associated with dexmedetomidine, followed by hypotension and cardiac arrest, by association rule mining and disproportionality analysis of FAERS reports. In addition, transcriptomic analysis using a public RNA-seq dataset revealed eight genes related to cardiac muscle contraction that were significantly downregulated in mouse cardiac cells exposed to dexmedetomidine. Potential DDIs were also identified, notably with Lactated Ringer’s Solution, bupivacaine, risperidone, and albuterol [30].

Despite these findings, this study was limited by several factors. First, the pharmacovigilance analysis relied on a relatively small number of FAERS reports (n = 1611), which restricted the statistical power. Second, the lack of propensity score matching raised concerns about residual confounding and possible bias in the observed associations. These limitations motivated the present study, which utilizes electronic health record (EHR) data to validate and expand upon our previous findings. EHR refers to a digital version of a patient’s medical chart maintained by hospitals or clinics, usually containing real-time and longitudinal patient data, including demographics, diagnoses, medications, lab results, and clinical notes. The rich clinical context allows tracking of drug exposure and outcomes over time and supports real-world evidence-based analyses [42]. Compared to FAERS, EHR offers a vastly larger sample size (on the order of 100 million records) enabling more robust and comprehensive analyses. The incorporation of propensity score matching minimizes bias by eliminating confounding factors. Moreover, the scope of transcriptomic investigation was broadened by introducing miRNA-based studies, which complement our prior mRNA-level analyses.

Therefore, this study aimed to validate the association between dexmedetomidine and bradycardia using large-scale EHR data, assess the impact of demographic confounders, identify clinically meaningful DDIs, and explore potential molecular mechanisms using miRNA expression profiling. By integrating real-world evidence with transcriptomic analyses, we sought to provide a more comprehensive and mechanistically informed evaluation of the cardiovascular safety profile of dexmedetomidine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. EHR Data and Propensity Score Matching

EHRs were accessed and analyzed the using real-world data network TriNetX (http://www.trinetx.com/ (accessed on 15 November 2025)). US Collaborative Network of the database was selected in this study.

Cohorts were defined by the following terms: “ICD-10-CM R00.1 Bradycardia, unspecified”, “48,937 dexmedetomidine”, “8782 Propofol”, “6130 Ketamine”, “6960 Midazolam”, “35,636 risperidone”, “435 albuterol”, “J7120 Ringers lactate infusion, up to 1000 cc”, and “1815 bupivacaine” in the TriNetX databases. Bradycardia events were identified using the terms “ICD-10-CM R00.1 Bradycardia, unspecified”. In TriNetX, exposure-outcome relationships are defined using standardized time window. In this study, time window was set as “from 1 month to 1 day”.

Patient numbers, demographic data, and clinical outcomes were all accessed and compared through the TriNetX platform. For propensity score matching, cohorts were matched using propensity scores on age at index, gender (Male, Female), and race (White, Black or African American, and Asian). TriNetX applies 1:1 nearest-neighbor propensity score matching using the user-selected covariates. The platform performs matching automatically, and matched cohorts are balanced on these variables.

2.2. Disproportionality Analysis

For disproportionality analysis, exposed and control cohorts’ definitions were annotated specifically. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated to quantify the disproportionality using the standard formula:

where

OR = (a × d)/(b × c)

- a = number of events in the exposed group,

- b = number of events in the control group,

- c = number of non-events in the exposed group,

- d = number of non-events in the control group.

2.3. FAERS Data Analysis

Adverse event reports submitted through FAERS were accessed using the publicly available FAERS dashboard tool. Both generic drug terms and the most common brand names were used as input search terms (dexmedetomidine: dexmedetomidine, dexmedetomidine hydrochloride, Precedex; Propofol: Propofol, Diprivan; Ketamine: Ketamine, Ketamine hydrochloride, Ketalar; Midazolam: Midazolam, Midazolam hydrochloride, Vesed).

To avoid repeated reports, indirect reports extracted from publications were excluded from analysis. Data analysis was performed using R statistical software version 4.5.0.

2.4. Transcriptomic Data Analysis

A public microarray dataset from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GEO id: GSE126106) was analyzed to explore the differentially expressed miRNAs in rat hearts of control groups (saline infusion for 30 min) and dexmedetomidine groups (dexmedetomidine infusion for 30 min). Differentially expressed genes were identified using the Limma package, which computes Benjamini–Hochberg (BH)-adjusted p-values to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Only miRNAs with an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and the absolute value of fold change >2 were considered significantly differentially expressed. GO enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler package with annotations from org.Hs.eg.db. Gene symbols were converted to Entrez Gene identifiers via the bitr function, and enrichment results were calculated with the BH method for multiple testing correction. All analyses were conducted in R statistical software version 4.5.0. miRNA target prediction was performed on TargetScanHuman 8.0 (https://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/ (accessed on 15 November 2025)).

3. Results

3.1. Association Between Dexmedetomidine Administration and Increased Risk of Bradycardia

First, we identified bradycardia as a significant ADE associated with dexmedetomidine using TriNetX data. As shown in Table 1, bradycardia occurred in 10.972% of patients receiving dexmedetomidine (n = 3,261,825), compared to 2.257% in the control group (patients not receiving dexmedetomidine, n = 128,539,168). The incidence in the dexmedetomidine group was nearly four times higher than in the control group, indicating a strong association between dexmedetomidine and bradycardia. These findings are consistent with our previous analysis using FAERS data.

Table 1.

Bradycardia prevalence with dexmedetomidine treatment using EHR data.

To determine whether the observed association between dexmedetomidine and bradycardia was due to other general anesthetics commonly used in perioperative settings rather than dexmedetomidine itself, we compared ADE profiles for dexmedetomidine with three widely used anesthetics including propofol, ketamine, and midazolam [43,44,45,46,47], using both FAERS data (Table 2) and propensity score-matched TriNetX data (Table 3).

Table 2.

Disproportionality analysis of bradycardia as an ADE among five common anesthetics using FAERS data.

Table 3.

Disproportionality analysis of bradycardia as ADE among five common anesthetics using propensity score-matched EHR data.

FAERS data analysis showed that, using dexmedetomidine as the reference, all three comparators had significantly lower ORs, ranging from 0.165 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.132–0.207) for ketamine to 0.285 (95% CI: 0.242–0.335) for propofol, with CIs excluding 1. Additionally, the rank of bradycardia among reported ADEs for these drugs was consistently lower (propofol: rank 7; ketamine: rank 32; midazolam: rank 8) compared with dexmedetomidine, for which bradycardia ranked first. These findings indicate that dexmedetomidine showed a significantly higher risk of bradycardia than the other general anesthetics.

For EHR data analysis, demographic biases between cohorts could potentially lead to confounding conclusions [48,49]. Without controlling baseline differences, associations between medications and outcomes may reflect underlying population characteristics rather than true pharmacological effects. Therefore, in our analysis, propensity score matching was applied to two cohorts to control key demographic factors, including age, gender, and race, thereby minimizing potential confounding [49]. Across all matched comparisons, using dexmedetomidine as the reference, propofol, ketamine, and midazolam exhibited ORs below 1 with 95% CIs excluding 1 (propofol: OR = 0.519, 95% CI: 0.513–0.525; ketamine: OR = 0.711, 95% CI: 0.703–0.719; midazolam: OR = 0.576, 95% CI: 0.569–0.582). These findings, consistent across FAERS pharmacovigilance data and real-world EHR analyses, demonstrate a significantly stronger association between dexmedetomidine and bradycardia compared with other general anesthetics, confirming that the observed cases are not merely attributable to anesthetic or surgical conditions but represent an intrinsic safety signal of dexmedetomidine.

3.2. Age-Stratified Analysis of Dexmedetomidine-Associated Bradycardia Risk

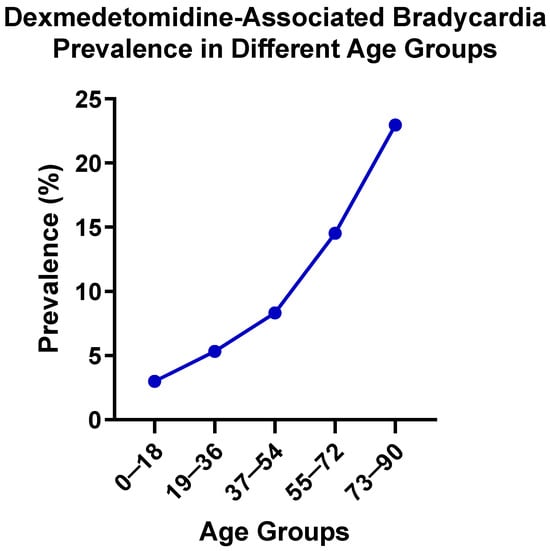

To find potential age- and gender-specific susceptibility to bradycardia in patients administered dexmedetomidine, age- and gender-stratified analyses of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia risk were conducted using EHR data. Figure 1 illustrates the age-stratified prevalence of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia across five age groups. The prevalence of bradycardia demonstrated a clear age-dependent gradient, rising steadily from 2.984% in patients aged 0–18 years to 22.976% in patients aged 73–90 years. The observed age-related trend suggests that older patients are at substantially greater risk of experiencing bradycardia, emphasizing the importance of the careful monitoring of bradycardia in elderly populations during dexmedetomidine treatment.

Figure 1.

Dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia prevalence in different age groups.

3.3. Gender-Stratified Analysis of Dexmedetomidine-Associated Bradycardia Risk

Table 4 presents the prevalence of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia by sex. The prevalence was slightly higher in males (12.084%) compared with females (9.840%), suggesting a modestly increased risk of bradycardia in male patients receiving dexmedetomidine. This finding highlights the potential need to consider sex as a factor when monitoring ADEs during dexmedetomidine treatment.

Table 4.

Dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia prevalence in different gender groups.

3.4. DDIs of Dexmedetomidine-Associated Bradycardia

Next, potential DDIs found in our previous study using FAERS were validated bby performing a disproportionality analysis of TriNetX EHR data. Table 5 summarizes the ORs of bradycardia in patients receiving dexmedetomidine in combination with one of four drugs (risperidone, albuterol, Lactated Ringer’s Solution, or bupivacaine) compared to those not receiving the respective co-medication, using data that were processed by propensity score matching. For each drug, ORs were calculated using the group that received dexmedetomidine without the secondary drug as reference. For risperidone, the OR for bradycardia in the dexmedetomidine plus risperidone group was 1.797 (95% CI: 1.688–1.913). A similar pattern was observed with albuterol (OR = 1.691, 95% CI: 1.664–1.719). These elevated ORs, with 95% CIs excluding 1, support the presence of DDIs between dexmedetomidine and these agents. In contrast, combinations with Lactated Ringer’s solution and bupivacaine yielded ORs of 0.863 (95% CI: 0.846–0.881) and 0.896 (95% CI: 0.882–0.910), respectively, indicating no evidence of DDIs associated with bradycardia based on TriNetX data.

Table 5.

Disproportionality analysis of risperidone, albuterol, Lactated Ringer’s Solution, and bupivacaine with dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia using propensity score-matched EHR data from the TriNetX database.

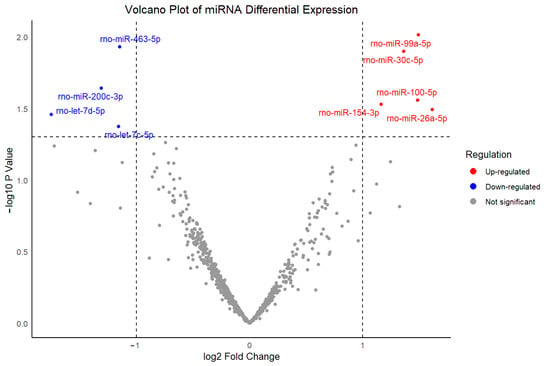

3.5. miRNA Profiling Analyses of Rat Hearts Treated with Dexmedetomidine

To investigate potential molecular mechanisms underlying dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia, transcriptomic analysis was conducted using a publicly available dataset (GEO ID: GSE126106) using the Limma package. This dataset profiled miRNA expression changes in rat hearts following dexmedetomidine administration compared to the control group using 3D-Gene Rat Oligo microarray chip 20 k V1.2.0. As is shown in Figure 2, 5 up-regulated (rno-miR-99a-5p, rno-miR-30c-5p, rno-miR-100-5p, rno-miR-154-3p, and rno-miR-26a-5p) and 4 down-regulated miRNAs (rno-miR-463-5p, rno-miR-200c-3p, rno-let-7d-5p, and rno-let-7c-5p) were identified among a total of 807 miRNAs, based on a p-value < 0.05 and a fold change > 2.

Figure 2.

Volcano plot of differentially expressed miRNAs between dexmedetomidine treatment and control at p-value < 0.05 and a fold change >2.

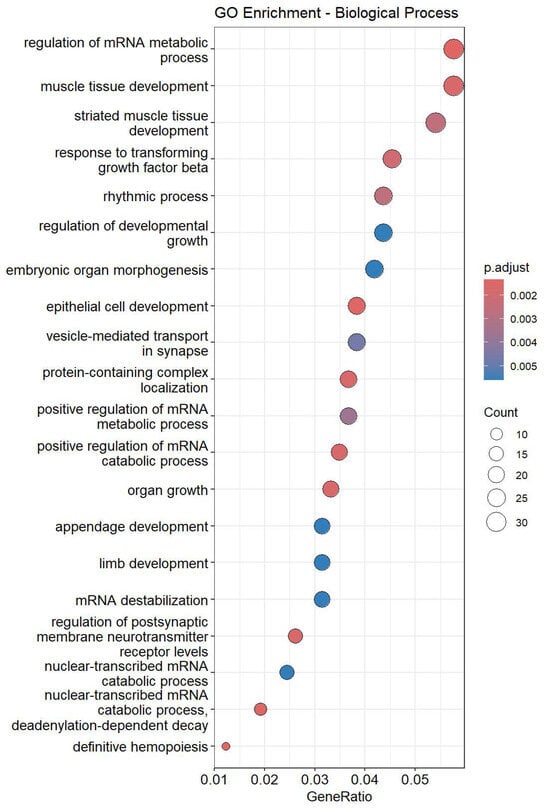

These findings highlight specific miRNAs as potential mediators of the observed cardiac rhythm disturbances caused by dexmedetomidine administration. Subsequently, targeted-mRNAs of up-regulated miRNAs were predicted using Target Scan Human 8.0, followed by Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses (Figure 3). GO analysis results indicated significant enrichment in processes related to rhythmic regulation, muscle tissue development, and striated muscle tissue development, all of which are closely linked to cardiac conduction and contractile function. The integration of these pathways supports a model in which dexmedetomidine-induced miRNA dysregulation contributes to altered molecular signaling, thereby leading to bradycardia.

Figure 3.

Top 20 enriched GO terms in rat hearts treated with dexmedetomidine.

To further identify individual miRNAs that are most strongly associated with dexmedetomidine-induced bradycardia, separate GO enrichment analyses were conducted. To systematically evaluate their potential contribution to bradycardia, a reference list of bradycardia-related GO terms was compiled first (Table S1). A bradycardia relationship score was calculated for each miRNA using the following formula:

score_sum = ∑ (−log10 (adjust p-value for bradycardia-related GO terms))

Thereby, the extent of each miRNA’s enrichment in bradycardia-relevant pathways was quantified.

Among the 5 up-regulated miRNAs, 2 miRNAs, miR-26a-5p and miR-30c-5p, demonstrated markedly higher scores for GO terms compared with others, for which the scores were zero (Table 6). Regulation of heart rate and regulation of cardiac muscle contraction were found enriched in miR-26a-5p targeted mRNAs, while cardiac muscle cell action potential, heart process, and heart contraction were found enriched in miR-30c-5p targeted mRNAs.

Table 6.

Top 2 miRNAs with the highest bradycardia-related GO scores.

Together, miRNA analyses identified 9 differently expressed miRNAs under dexmedetomidine treatment. Rhythmic regulation and muscle development pathways were found to be enriched in the 5 up-regulated miRNA-targeted mRNAs. Furthermore, two miRNAs, miR-26a-5p and miR-30c-5p, were identified as candidates that are potentially involved in dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia.

4. Discussion

This study employed a multidisciplinary approach integrating large-scale EHR analyses with transcriptomic profiling to evaluate bradycardia as a clinically significant ADE associated with dexmedetomidine. Stratified analyses by age and gender revealed distinct risks of dexmedetomidine-induced bradycardia, with particularly elevated risk observed among elderly patients. In addition, risperidone and albuterol were observed as being associated with higher bradycardia risk, when co-administered with dexmedetomidine. Furthermore, miRNA analyses identify possible miRNAs and their target genes that may be involved in the process by which dexmedetomidine treatment is associated with bradycardia. These findings suggest potential risks of dysregulated heart rate control associated with the use of dexmedetomidine, emphasizing the importance of careful risk assessment and clinical monitoring, particularly in geriatric patients and cases of co-administration with other medications.

The pronounced increase in bradycardia prevalence observed with advancing age among patients treated with dexmedetomidine may reflect a convergence of age-related physiological, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic changes. First, aging is characterized by reduced autonomic flexibility, including diminished baroreceptor sensitivity, decreased β-adrenergic receptor responsivity, and increased vagal predominance [50,51,52,53], which may amplify the bradycardia effect of α2-adrenergic agonists like dexmedetomidine. Second, structural and electrophysiological remodeling of the aging myocardium, including sinoatrial node fibrosis, loss of pacemaker cells, altered ion channel expression, and slowed conduction pathways [54,55,56,57], making the older heart inherently more sensitive to suppression of nodal automaticity and conduction delays induced by dexmedetomidine. Third, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes in older patients, such as decreased hepatic clearance, increased volume of distribution, and altered receptor sensitivity [58,59,60,61], may exacerbate the systemic and cardiac effects of dexmedetomidine. Finally, older patients often harbor comorbidities, for example, conduction system diseases that blunt heart rate, and polypharmacy [62,63,64]. Both may act as potential factors for dexmedetomidine-induced bradycardia. Collectively, these mechanisms provide a plausible explanation for the age-dependent gradient of dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia risk observed in this study. These findings emphasize the importance of precise monitoring and dose adjustment of dexmedetomidine in elderly populations to avoid cardiovascular complications. However, it should be noted that TriNetX does not provide detailed patient-level information on comorbidities, concurrent cardio-depressant medications, dexmedetomidine infusion dose, or duration. As older patients may have a higher burden of cardiac disease and may receive longer or higher-dose infusions, as well as more concomitant medications that can depress heart rate, these factors, which are not incorporated into the stratified models, may lead to the observed increase in bradycardia prevalence with increased age being a product of either residual confounding or clinical practice patterns, rather than an independent age effect. These findings are therefore exploratory and hypothesis-generating, and future studies with full patient-level EHR data will be required to validate these age effects.

The observed DDI between dexmedetomidine and risperidone may be attributed to addictive pharmacodynamic effects mediated by central autonomic modulations. As a potent α2-adrenergic receptor agonist, dexmedetomidine diminishes sympathetic tone through vagal activation and baroreflex suppression, resulting in bradycardia and hypotension [5,31]. Risperidone is an antagonist of dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, of which are associated with QT-interval prolongation and arrhythmogenic risk, including torsade de pointes and sudden cardiac death [65,66]. Consequently, co-administration of dexmedetomidine and risperidone could produce additive effects that impair both heart rhythm regulation and myocardial repolarization, increasing vulnerability to bradyarrhythmia. Furthermore, both agents exert central autonomic suppression: dexmedetomidine via inhibition of central noradrenergic pathways and risperidone via dopaminergic and serotonergic modulation, potentially exacerbating bradycardia by compounding decreases in sympathetic output. At the molecular level, dexmedetomidine has been reported to influence gene expression linked to cardiac contraction, ion channels, and neurotransmitter regulation [67,68], while animal studies suggest that risperidone could induce proteomic alterations in cardiac myocytes, affecting calcium-handling proteins and gap junction constituents critical to conduction integrity [69]. Although direct evidence of combined transcriptional or translational changes is limited, it is plausible that co-exposure could amplify disruption of ion channel function and intercellular electrical coupling, thereby promoting susceptibility to conduction delays and arrhythmias.

The DDI between dexmedetomidine and albuterol is possibly characterized by pharmacodynamic opposition and potential electrolyte-mediated modulation of conduction. Albuterol is a β2-agonist with the primary function of promoting bronchodilation. It can exert sympathomimetic effects, including increased heart rate and myocardial contractility [70,71], which are antithetical to the pronounced bradycardia and hypotension of dexmedetomidine. However, this “tug-of-war” between autonomic branches may disturb normal cardiac conduction and exacerbate arrhythmic risk. During bradycardic states induced by dexmedetomidine, the sudden sympathetic push from albuterol may precipitate ectopic foci or conduction disturbances. Additionally, albuterol is known to induce serum hypokalemia and occasionally prolong QT interval, particularly at high doses or with repeated administration [72,73]. Hypokalemia compromises repolarization reverse, and when overlapped with bradycardia, may amplify QT prolongation and predispose to severe ventricular arrhythmias. Thus, the co-administration of dexmedetomidine and albuterol increases the risk of bradycardia through both antagonistic autonomic influences and electrolyte imbalance that can destabilize cardiac electrophysiology.

Despite this hypothesis, the observed association between albuterol and bradycardia may reflect residual confounding and clinical context. For example, albuterol is frequently administered to severely ill patients, such as those with respiratory failure, hypoxia, or sepsis, who may have a higher baseline risk of bradycardia due to disease severity and concomitant sedatives, or procedures such as intubation. Because TriNetX does not allow adjustment for ICU status, illness severity, or detailed medication patterns, these factors cannot be fully controlled. Therefore, the albuterol signal should be viewed as an exploratory association rather than a physiological effect, and further patient-level studies will be necessary to investigate this unexpected finding. Another limitation for the explanation of DDI between albuterol and dexmedetomidine is that TriNetX does not provide patient-level timestamps for medication administration. As a result, the precise temporal relationship between exposures cannot be established. For example, we cannot determine whether albuterol was administered before, after, or concurrently with dexmedetomidine, nor can we link bradycardia onset to a specific sequence of therapies. This lack of temporal resolution limits our ability to distinguish confounding by indication, acute illness severity, or procedural timing, and therefore the DDI findings, particularly the unexpected association with albuterol, should be interpreted with caution.

The findings related to Lactated Ringer’s Solution and bupivacaine should also be interpreted with caution. Both agents are closely tied to procedural or perioperative contexts, and their use likely reflects underlying clinical scenarios rather than true pharmacologic interactions with dexmedetomidine. Consistent with this, no significant increase in bradycardia risk was detected for those combinations in the EHR analysis. However, because TriNetX does not provide detailed procedural timing or contextual information, residual confounding due to clinical setting or co-interventions cannot be excluded.

The two up-regulated miRNAs identified in this study, miR-26a-5p and miR-30c-5p, may participate in molecular processes that are involved in known pharmacodynamic actions of dexmedetomidine. GO enrichment analysis revealed that regulation of heart rate and regulation of cardiac muscle contraction were enriched in miR-26a-5p targeted genes, while cardiac muscle cell action potential, heart process, and heart contraction were enriched in miR-30c-5p targeted genes. miR-26a-5p has been implicated in myocardial hypertrophy, inflammatory signaling, and arrhythmogenesis, which are processes that directly contribute to cardiac rhythm instability [74,75,76,77,78,79]. Similarly, the miR-30 family has been linked to cardiomyocyte survival, apoptosis regulation, and tissue remodeling, which modulate electrophysiological stability, thereby influencing susceptibility to bradycardia [80,81,82,83]. Altered expression of these two miRNAs may therefore increase susceptibility to bradycardia by modifying cardiomyocyte excitability or conduction system integrity, complementing the central and peripheral adrenergic mechanisms through which dexmedetomidine directly exerts its cardiovascular effects. The identification of these two miRNAs provides a potential molecular explanation for the elevated bradycardia susceptibility induced by dexmedetomidine observed in this study.

Although the microarray dataset used in this study was derived from rat cardiac tissue, targeted mRNA prediction was performed using the TargetScanHuman 8.0 database. This approach is justified by the high evolutionary conservation of most miRNA sequences between rodents and humans [84], where many mature miRNAs share identical or nearly identical sequences and nomenclature, including miR-26a-5p and miR-30c-5p [85]. Consequently, their biological roles, particularly in fundamental processes such as cardiac rhythm regulation, muscle contraction, and electrophysiological signaling, are generally preserved across species [86]. Furthermore, TargetScanHuman 8.0 provides more comprehensive annotation and coverage of predicted targets compared with rat-specific resources, thereby enhancing the functional interpretability of enrichment analyses. Nevertheless, certain species-specific differences in target gene networks may exist and limit direct extrapolation to human physiology. Future studies using human-derived samples or experimental validation are required to substantiate these predicted interactions.

An interesting question raised by our findings is whether related α2-adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine and guanfacine, would produce similar miRNA expression profiles in cardiac tissue, which would support an α2-receptor-dependent regulation of miRNA expression. Although this is a compelling hypothesis, our analyses relied on publicly available transcriptomic data. and comparable miRNA datasets derived from cardiac tissues were unavailable. Consequently, the comparison of miRNA profiles across different α2-adrenergic agonists and the determination of whether the two miRNAs identified in this study reflect a dexmedetomidine-specific or a broader class effect cannot be achieved. Further work incorporating parallel miRNA profiling of cardiac tissue after treatment with multiple and representative α2-adrenergic agonists will be crucial to validate this hypothesis.

Propensity score matching is a statistical technique designed to reduce confounding in observational studies by balancing baseline covariates between treatment and control groups [87]. By estimating the probability of receiving a given treatment conditional on observed covariates, propensity score matching allows for the construction of matched cohorts that mimic certain characteristics of randomized controlled trials. This approach has been widely applied in pharmacoepidemiology and clinical outcomes research to strengthen causal inference and mitigate bias arising from nonrandom treatment allocation [88,89,90,91]. The controversies between studies on FAERS and EHR in this study demonstrated that demographic or clinical imbalances could lead to spurious associations, such as the DDIs between dexmedetomidine and Lactated Ringer’s Solution or bupivacaine. As all analyses in this study were conducted within the TriNetX platform, which automatically applies propensity score matching, one limitation is that the underlying algorithm used by the platform is not transparent, preventing verification or customization of the matching procedure. To address this problem, we repeated the propensity score matching process ten independent times. Figure S1 presents the results of disproportionality analyses for bradycardia upon dexmedetomidine and risperidone, comparing outcomes before and after propensity score matching. Without propensity score matching, the ORs were 1.882, while the value decreased slightly to 1.759 after propensity score matching. Across 10 repeated runs, the ORs remained highly consistent, showing only minor fluctuations between iterations. The standard error of the mean (SEM) was 0.029, indicating minimal relative variability. The reduction in ORs suggests that the observed associations found using unadjusted EHR data are possibly attributed to demographic imbalances. In addition, the repeated matching trials yielded highly consistent results, as evidenced by the low SEM, indicating that the random selection process inherent to the propensity score matching algorithm in the TriNetX platform did not materially influence outcome estimates. These findings reinforce the internal consistency of the platform’s matching implementation.

Notably, several limitations of the TriNetX platform should be acknowledged. First, all EHR analyses were conducted using aggregated data available within the TriNetX platform, which does not provide access to raw, patient-level EHRs. Therefore, it is unable to manually verify diagnoses, assess clinical context, evaluate comorbidities in detail, or examine precise temporal relationships between drug administration and bradycardia onset. Second, although propensity score matching was applied to reduce confounding factors by age, sex, and race, residual from unmeasured variables, such as concurrent medications, severity of illness, or procedural factors, may still influence the observed associations. Third, the inconsistent and variable availability of comorbidity information across participating clinical sites makes incorporating comorbidities as matching variables lead to substantial reductions in sample size, thereby undermining the objective of investigating prevalence patterns in a large real-world population. Fourth, the platform does not provide detailed information about dosing, infusion rate, or duration. Because dexmedetomidine-induced bradycardia is highly dose-dependent, the absence of dosage data limits interpretation of risk magnitude. Fifth, the EHR-based disproportionality analyses cannot establish causality, and observed DDIs should be interpreted as signals requiring further mechanistic or clinical validation. Another limitation in statistics is the potential for Type I error inflation due to multiple subgroups and DDI analyses. Age-based and sex-based cohorts, as well as several DDI evaluations, were performed to explore clinically relevant modifiers of bradycardia risk. However, these exploratory analyses were not adjusted for multiple testing. The TriNetX platform does not offer built-in multiplicity correction for stratified or matched cohort comparisons, and these results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Further studies with dedicated statistical frameworks and access to raw patient-level data will be necessary to formally correct for multiple comparisons and validate these subgroup findings. Finally, because TriNetX uses automated cohort construction and matching algorithms that are not user-modifiable, some methodological details remain unclear. For example, the platform does not provide patient-level timestamps; users must select from predefined time windows rather than define a customized time-at-risk period. The lack of temporal data limits reproducibility and causal inference and should be considered when interpreting the findings. Further studies with full patient-level EHR access or institution-specific datasets will be important to incorporate more clinical covariates and to more rigorously assess the magnitude of confounding factors. Despite these limitations, the convergence of evidence across multiple analytic approaches strengthens the reliability of our findings.

In addition, several limitations of the FAERS component of this study should be noted. As with all spontaneous reporting systems, FAERS is subject to under-reporting, and the absence of denominator data prevents estimation of true incidence rates. Reporting is influenced by stimulated reporting, publicity, severity of events, and clinician awareness, all of which introduce substantial reporting bias. Although, in this paper, efforts were made to exclude publication-derived indirect reports, duplicate submissions may still occur and cannot be completely ruled out. Additionally, FAERS entries lack detailed clinical context, such as medication timing, comorbidities, and concurrent therapies, limiting the ability to adjust for confounding. More importantly, FAERS supports only the identification of disproportionality signals and cannot establish causal relationships. These constraints emphasize the need to interpret FAERS findings cautiously and reinforce the value of validating signals using complementary real-world data, such as EHR, as performed in this study.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study identified the association between bradycardia and dexmedetomidine through large-scale EHR and FAERS analyses, independent of anesthetic or surgical confounding. Age- and gender-stratified analyses revealed a clear age-dependent increase in risk and a modest elevation in males. Propensity score-matched DDI analyses further identified risperidone and albuterol as possible pharmacological interactors with dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia, while observed associations with Lactated Ringer’s Solution and bupivacaine in FAERS were likely attributable to demographic confounding. Finally, transcriptomic profiling identified nine differentially expressed miRNAs, with miR-26a-5p and miR-30c-5p emerging as candidates mechanistically linked to cardiac rhythm regulation. Together, these findings provide clinical and molecular evidence for the bradycardia risks of dexmedetomidine, underscore the importance of demographic and DDI factors, and suggest potential molecular pathways contributing to its bradycardic effects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb47121028/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z., S.A.K., X.L., A.H. and F.C.; methodology, X.Z., L.B., X.L. and F.C.; software, X.Z. and F.C.; validation, X.Z., R.M. and F.C.; formal analysis, X.Z. and F.C.; investigation, X.Z., S.A.K. and F.C.; resources, F.C.; data curation, X.Z. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z., R.M. and F.C.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., R.M., X.L., A.H. and F.C.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, F.C.; project administration, F.C.; funding acquisition, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Florida Corridor Undergraduate Research Initiative 2024 to F.C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Under U.S. federal regulations (45 CFR 46), the database information used in this document does not involve any identifiable private information and therefore does not require IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Under U.S. federal regulations (45 CFR 46), the database information used in this document does not involve any identifiable private information and therefore does not require patient informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| DDI | Drug–Drug Interaction |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| ADE | Adverse Drug Event |

| FAERS | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| PACU | Postanesthesia Care Unit |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| 5-HT2A | 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor 2A |

| SEM | Standard Error of Mean |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| IV | Intravenous |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg Method |

References

- Kong, H.; Li, M.; Deng, C.M.; Wu, Y.J.; He, S.T.; Mu, D.L. A comprehensive overview of clinical research on dexmedetomidine in the past 2 decades: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1043956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, P.M. Current role of dexmedetomidine in clinical anesthesia and intensive care. Anesth. Essays Res. 2011, 5, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, L.; Wang, Z.; Shen, J.; Xing, X.; Yuan, H. Impact of Dexmedetomidine on Hemodynamics, Plasma Catecholamine Levels, and Delirium Incidence Among Intubated Patients in the ICU—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2024, 20, 689–700. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, T.H.; Chen, M.J.; Yang, Y.R.; Yang, J.J.; Tang, F.I. Action of dexmedetomidine on rat locus coeruleus neurones: Intracellular recording in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995, 285, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, R.; Brown, H.C.; Mitchell, D.H.; Silvius, E.N. Dexmedetomidine: A novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 2001, 14, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Grégoire, C.; De Kock, M.; Henrie, J.; Cren, R.; Lavand’homme, P.; Penaloza, A.; Verschuren, F. Procedural Sedation with Dexmedetomidine in Combination with Ketamine in the Emergency Department. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 63, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, A.; Duncan, A.; Leung, S.; Karimi, N.; Fang, J.; Mao, G.; Hargrave, J.; Gillinov, M.; Trombetta, C.; Ayad, S.; et al. Dexmedetomidine for reduction of atrial fibrillation and delirium after cardiac surgery (DECADE): A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liu, C.; Ma, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Perioperative dexmedetomidine reduces delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Can. J. Anaesth. 2019, 66, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Li, S.; Chen, Q.; Li, W.; Peng, S.; Ouyang, H.; Zhu, X.; Tan, L.; Zhang, Z. Dexmedetomidine for cancer pain: Mechanisms and opioid-sparing effects. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 4694–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, H.H.; Liou, J.Y.; Teng, W.N.; Hsu, P.K.; Tsou, M.Y.; Chang, W.K.; Ting, C.K. Opioid-sparing anesthesia with dexmedetomidine provides stable hemodynamic and short hospital stay in non-intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: A propensity score matching cohort study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Tsivitis, A.; Wang, A.; Murphy, J.; Khan, A.; Jin, Z.; Moore, R.; Tateosian, V.; Bergese, S. Anesthesia, the developing brain, and dexmedetomidine for neuroprotection. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1150135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaiani, G.; Silverton, N.; Fedorko, L.; Carroll, J.; Styra, R.; Rao, V.; Katznelson, R. Dexmedetomidine versus Propofol Sedation Reduces Delirium after Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2016, 124, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G.M. Dexmedetomidine: A Review of Its Use for Sedation in the Intensive Care Setting. Drugs 2015, 75, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, A.T.; Murphy, C.V. Sedation with dexmedetomidine in the intensive care setting. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2011, 3, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, S.; Ozair, E. Dexmedetomidine in current anaesthesia practice—A review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, GE01–GE04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Dexmedetomidine: Present and future directions. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, Y.; Hirata, N.; Terada, H.; Sawashita, Y.; Yamakage, M. Identification of Candidate Genes and Pathways in Dexmedetomidine-Induced Cardioprotection in the Rat Heart by Bioinformatics Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerink, M.A.S.; Struys, M.M.R.F.; Hannivoort, L.N.; Barends, C.R.M.; Absalom, A.R.; Colin, P. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Dexmedetomidine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 56, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannitti, J.A., Jr.; Thoms, S.M.; Crawford, J.J. Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists: A review of current clinical applications. Anesth. Prog. 2015, 62, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, C.; Jiang, J.; Qiu, L. Dexmedetomidine protects mice against myocardium ischaemic/reperfusion injury by activating an AMPK/PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017, 44, 946–953. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.H.; Jin, M.M.; Liu, J.T. Dexmedetomidine pretreatment protects the heart against apoptosis in ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats by activating PI3K/Akt signaling in vivo and in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110188. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Y.; Kelly-Hedrick, M.; Komisarow, J.; Hatfield, J.; Ohnuma, T.; Treggiari, M.M.; Colton, K.; Arulraja, E.; Vavilala, M.S.; Laskowitz, D.T.; et al. Association of Early Dexmedetomidine Utilization with Clinical Outcomes After Moderate-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Anesth. Analg. 2024, 139, 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Benneyworth, B.D.; Downs, S.M.; Nitu, M. Retrospective Evaluation of the Epidemiology and Practice Variation of Dexmedetomidine Use in Invasively Ventilated Pediatric Intensive Care Admissions, 2007–2013. Front. Pediatr. 2015, 3, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Kang, L.; Wang, Q. Recent Advances in the Clinical Value and Potential of Dexmedetomidine. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 7507–7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, R.; Forrest, L.K.; Kiser, T.H. Adjunctive dexmedetomidine therapy in the intensive care unit: A retrospective assessment of impact on sedative and analgesic requirements, levels of sedation and analgesia, and ventilatory and hemodynamic parameters. Pharmacotherapy 2007, 27, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Hang, L.H.; Wang, H.; Shao, D.H.; Xu, Y.G.; Cui, W.; Chen, Z. Intranasally Administered Adjunctive Dexmedetomidine Reduces Perioperative Anesthetic Requirements in General Anesthesia. Yonsei Med. J. 2016, 57, 998–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, B.L.; Harrison, D.L.; Gormley, A.K.; Johnson, P.N. Evaluation of adverse events noted in children receiving continuous infusions of dexmedetomidine in the intensive care unit. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 15, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Ahn, E. Risk factors for dexmedetomidine-associated bradycardia during spinal anesthesia: A retrospective study. Medicine 2022, 101, e31306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.K.; Lee, K.H.; Han, H.J.; Choi, I.Y.; Kim, N.J.; Kim, K. Dexmedetomidine in Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Yonsei Med. J. 2025, 66, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.; Kuppa, S.A.; Zhu, X.; Bu, K.; Han, W.; Cheng, F. The Association Between Dexmedetomidine and Bradycardia: An Analysis of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Data and Transcriptomic Profiles. Genes 2025, 16, 615. [Google Scholar]

- Pöyhiä, R.; Nieminen, T.; Tuompo, V.W.T.; Parikka, H. Effects of Dexmedetomidine on Basic Cardiac Electrophysiology in Adults; a Descriptive Review and a Prospective Case Study. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wan, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Dexmedetomidine: A real-world safety analysis based on FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1419196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Ye, H.; Wang, M.; Wang, T. Effect of Dexmedetomidine on Tachyarrhythmias After Cardiac Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2022, 79, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Kumar, A.; Deshmukh, A.; Bennett, C. Dexmedetomidine Reduces Incidences of Ventricular Arrhythmias in Adult Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2022, 2022, 5158362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.; Marine, J.E. Evaluating and management bradycardia. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 30, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runciman, W.B.; Morris, R.W.; Watterson, L.M.; Williamson, J.A.; Paix, A.D. Crisis management during anaesthesia: Cardiac arrest. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2005, 14, e14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellolio, M.F.; Gilani, W.I.; Barrionuevo, P.; Murad, M.H.; Erwin, P.J.; Anderson, J.R.; Miner, J.R.; Hess, E.P. Incidence of Adverse Events in Adults Undergoing Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, J.C.K.; Tabah, A.; Campher, M.J.J.; Laupland, K.B.; Eley, V.A. The Effect of Dexmedetomidine on Postanesthesia Care Unit Discharge and Recovery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth. Analg. 2022, 134, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, K.; Piticaru, J.; Chaudhuri, D.; Basmaji, J.; Fan, E.; Møller, M.H.; Devlin, J.W.; Alhazzani, W. Safety and Efficacy of Dexmedetomidine in Acutely Ill Adults Requiring Noninvasive Ventilation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials. Chest 2021, 159, 2274–2288. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, B.; Chang, E.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Intravenous administration of dexmedetomidine and quality of recovery after elective surgery in adult patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Anesth. 2020, 65, 109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, X.; Wei, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of dexmedetomidine on neurocognitive disturbance after elective non-cardiac surgery in senile patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Med. Res. 2021, 49, 3000605211014294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Feldman, S.S. The Value of Electronic Health Records Since the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act: Systematic Review. JMIR Med. Inform. 2022, 10, e37283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, T.S.; Parker, R.A.; Aitken, L.M.; McKenzie, C.A.; Emerson, L.; Boyd, J.; Macdonald, A.; Beveridge, G.; Giddings, A.; Hope, D.; et al. Dexmedetomidine- or Clonidine-Based Sedation Compared with Propofol in Critically Ill Patients: The A2B Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 334, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, Y.; Pruna, A.; Turi, S.; Borghi, G.; Lee, T.C.; Zangrillo, A.; Landoni, G.; Pasin, L. Propofol and survival: An updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroki, T.; Kotani, Y.; Yaguchi, T.; Shibata, T.; Fujii, M.; Fresilli, S.; Tonai, M.; Karumai, T.; Lee, T.C.; Landoni, G.; et al. Ketamine versus etomidate as an induction agent for tracheal intubation in critically ill adults: A Bayesian meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Qiu, D.; Gu, H.W.; Wang, X.M.; Hashimoto, K.; Zhang, G.F.; Yang, J.J. Efficacy and safety of perioperative application of ketamine on postoperative depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 2266–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolt, R.; Hyslop, M.C.; Herbert, E.; Papaioannou, D.E.; Totton, N.; Wilson, M.J.; Clarkson, J.; Evans, C.; Ireland, N.; Kettle, J.; et al. The MAGIC trial: A pragmatic, multicentre, parallel, noninferiority, randomised trial of melatonin versus midazolam in the premedication of anxious children attending for elective surgery under general anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2024, 132, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perets, O.; Stagno, E.; Yehuda, E.B.; McNichol, M.; Anthony Celi, L.; Rappoport, N.; Dorotic, M. Inherent Bias in Electronic Health Records: A Scoping Review of Sources of Bias. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sahab, B.; Leviton, A.; Loddenkemper, T.; Paneth, N.; Zhang, B. Biases in Electronic Health Records Data for Generating Real-World Evidence: An Overview. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2024, 8, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, J.R.; Levy, W.C.; Caldwell, J.H.; Jacobson, A.; May, J.; Matsuoka, D.; Madden, K. Effects of aging on cardiovascular responses to parasympathetic withdrawal. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 2077–2083. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A.U.; Radaelli, A.; Centola, M. Invited review: Aging and the cardiovascular system. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2003, 95, 2591–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Deng, J.; Amil, F.A.; Po, S.S.; Dasari, T.W. The role of age-associated autonomic dysfunction in inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Geroscience 2022, 44, 2655–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.H.; Kuo, T.B.J.; Li, J.Y.; Kuo, K.L.; Chern, C.M.; Yang, C.C.H.; Huang, H.Y. Effects of age and sex on vasomotor activity and baroreflex sensitivity during the sleep-wake cycle. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 22424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, E.D.; St Clair, J.R.; Sumner, W.A.; Bannister, R.A.; Proenza, C. Depressed pacemaker activity of sinoatrial node myocytes contributes to the age-dependent decline in maximum heart rate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18011–18016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadaccio, C.; Rainer, A.; Mozetic, P.; Trombetta, M.; Dion, R.A.; Barbato, R.; Nappi, F.; Chello, M. The role of extracellular matrix in age-related conduction disorders: A forgotten player? J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, C.H.; Sharpe, E.J.; Proenza, C. Cardiac Pacemaker Activity and Aging. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2020, 82, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.F.; Hou, C.; Jia, F.; Zhong, C.H.; Xue, C.; Li, J.J. Aging-associated atrial fibrillation: A comprehensive review focusing on the potential mechanisms. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14309. [Google Scholar]

- Turnheim, K. When drug therapy gets old: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in the elderly. Exp. Gerontol. 2003, 38, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, U. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Drug Metab. Rev. 2009, 41, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, A.J.; Pont, L.G. Drug metabolism in older people—A key consideration in achieving optimal outcomes with medicines. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, D.; Ailabouni, N.; Mangoni, A.A.; Wiese, M.D.; Reeve, E. Alterations in drug disposition in older adults: A focus on geriatric syndromes. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2021, 17, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh-Taha, M.; Asmar, M. Polypharmacy and severe potential drug-drug interactions among older adults with cardiovascular disease in the United States. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delara, M.; Murray, L.; Jafari, B.; Bahji, A.; Goodarzi, Z.; Kirkham, J.; Chowdhury, M.; Seitz, D.P. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 601. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, G.V.; Marine, J.E.; Fleg, J.L. Epidemiology of arrhythmias and conduction disorders in older adults. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2012, 28, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieweg, W.V.; Hasnain, M.; Hancox, J.C.; Baranchuk, A.; Digby, G.C.; Kogut, C.; Crouse, E.L.; Koneru, J.N.; Deshmukh, A.; Pandurangi, A.K. Risperidone, QTc interval prolongation, and torsade de pointes: A systematic review of case reports. Psychopharmacology 2013, 228, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolet, B.; Yang, T.; Daleau, P.; Roden, D.M.; Turgeon, J. Risperidone prolongs cardiac repolarization by blocking the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2003, 41, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Li, J.; Qiu, L.; Jiang, C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Q.; Hong, H.; Ye, L. Dexmedetomidine Protects Human Cardiomyocytes Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Through α2-Adrenergic Receptor/AMPK-Dependent Autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 615424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Jia, T.; Sun, X.; Xing, Z.; Liu, H.; Yao, J.; Chen, Y. Dexmedetomidine prevents cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury via modulating tetmethylcytosine dioxygenase 1-mediated DNA demethylation of Sirtuin1. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 9369–9386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchemin, M.; Geguchadze, R.; Guntur, A.R.; Nevola, K.; Le, P.T.; Barlow, D.; Rue, M.; Vary, C.P.H.; Lary, C.W.; Motyl, K.J.; et al. Exploring mechanisms of increased cardiovascular disease risk with antipsychotic medications: Risperidone alters the cardiac proteomic signature in mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.; Chen, J. Changes in heart rate associated with nebulized racemic albuterol and levalbuterol in intensive care patients. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2003, 60, 1971–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.; Kennedy, A.; John, B.M.; Duane, B.; Lemanowicz, J.; Little, J. A comparison of heart rate changes associated with levalbuterol and racemic albuterol in pediatric cardiology patients. Ann. Pharmacother. 2013, 47, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, S.; Yuksel, H.; Tikiz, H.; Danahaliloğlu, S. Standard dose of inhaled albuterol significantly increases QT dispersion compared to low dose of albuterol plus ipratropium bromide therapy in moderate to severe acute asthma attacks in children. Pediatr. Int. 2001, 43, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.; Patel, K.; Cantu, R.; Akmyradov, C.; Irby, K. Hypokalemia Measurement and Management in Patients with Status Asthmaticus on Continuous Albuterol. Hosp. Pediatr. 2022, 12, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icli, B.; Dorbala, P.; Feinberg, M.W. An emerging role for the miR-26 family in cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2014, 24, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.E.; Kim, S.W.; Jeong, S.; Moon, H.; Choi, W.S.; Lim, S.; Lee, S.; Hwang, K.C.; Choi, J.W. MicroRNA-26a/b-5p promotes myocardial infarction-induced cell death by downregulating cytochrome c oxidase 5a. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; Xue, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Q. MiR-26a-5p alleviates cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction via targeting ADAM17. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Bi, S.; Wang, X.; Lu, Q. miR-26a-5p protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2020, 53, e9106, Erratum in Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2020, 53, e9106erratum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.H.; Huang, G.K.; Kang, C.H.; Cheng, Y.T.; Kao, Y.H.; Chien, Y.S. MicroRNA-26a-5p Restoration Ameliorates Unilateral Ureteral Obstruction-Induced Renal Fibrosis in Mice Through Modulating TGF-β Signaling. Lab. Investig. 2023, 103, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Sun, H.; Bo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y.; et al. MCPIP1 promotes atrial remodeling by exacerbating miR-26a-5p/FRAT/Wnt axis-mediated atrial fibrosis in a rat model susceptible to atrial fibrillation. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxhammer, E.; Paar, V.; Wernly, B.; Kiss, A.; Mirna, M.; Aigner, A.; Acar, E.; Watzinger, S.; Podesser, B.K.; Zauner, R.; et al. MicroRNA-30d-5p-A Potential New Therapeutic Target for Prevention of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy after Myocardial Infarction. Cells 2023, 12, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.O.; Park, J.H.; Kim, T.; Hong, S.E.; Lee, J.Y.; Nho, K.J.; Cho, C.; Kim, Y.S.; Kang, W.S.; Ahn, Y.; et al. A novel system-level approach using RNA-sequencing data identifies miR-30-5p and miR-142a-5p as key regulators of apoptosis in myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.B.; Niu, Q.H.; Zhang, M.; Feng, L.; Feng, J. Critical functions of microRNA-30a-5p-E2F3 in cardiomyocyte apoptosis induced by hypoxia/reoxygenation. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2021, 37, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, S.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, A.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhang, J. The microRNA in ventricular remodeling: The miR-30 family. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeary, S.E.; Lin, K.S.; Shi, C.Y.; Pham, T.M.; Bisaria, N.; Kelley, G.M.; Bartel, D.P. The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy. Science 2019, 366, eaav1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.C.; Farh, K.K.; Burge, C.B.; Bartel, D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacchi-Suzzi, C.; Hahne, F.; Scheubel, P.; Marcellin, M.; Dubost, V.; Westphal, M.; Boeglen, C.; Büchmann-Møller, S.; Cheung, M.S.; Cordier, A.; et al. Heart structure-specific transcriptomic atlas reveals conserved microRNA-mRNA interactions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeweiss, S.; Rassen, J.A.; Glynn, R.J.; Avorn, J.; Mogun, H.; Brookhart, M.A. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology 2009, 20, 512–522, Erratum in Epidemiology 2018, 29, e63–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Feng, W.; Zhang, P. Propensity score-adjusted three-component mixture model for drug-drug interaction data mining in FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Stat. Med. 2020, 39, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johara, F.T.; Benedetti, A.; Platt, R.; Menzies, D.; Viiklepp, P.; Schaaf, S.; Chan, E. Evaluating the performance of propensity score matching based approaches in individual patient data meta-analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.H.; Stuart, E.A. Propensity score methods for observational studies with clustered data: A review. Stat. Med. 2022, 41, 3612–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).