Abstract

The beneficial effects of polyphenols on metabolic disorders have been extensively reported. The interaction of these compounds with the gut microbiota has been the focus of recent studies. In this review, we explored the fundamental mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of polyphenols in relation to the gut microbiota in murine models of metabolic disorders. We analyzed the effects of polyphenols on three murine models of metabolic disorders, namely, models of a high-fat diet (HFD)-induced metabolic disorder, dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, and a metabolic disorder not associated with HFD or DSS. Regardless of the model, polyphenols ameliorated the effects of metabolic disorders by alleviating intestinal oxidative stress, improving inflammatory status, and improving intestinal barrier function, as well as by modulating gut microbiota, for example, by increasing the abundance of short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria. Consequently, polyphenols reduce circulating lipopolysaccharide levels, thereby improving inflammatory status and alleviating oxidative imbalance at the lesion sites. In conclusion, polyphenols likely act by regulating intestinal functions, including the gut microbiota, and may be a safe and suitable therapeutic agent for various metabolic disorders.

1. Introduction

Polyphenols, widely distributed in fruits, vegetables, and plant-based beverages, such as tea, coffee, and wine, have health benefits, which have been thought to be due to their antioxidative activity. Polyphenols, alone or as part of mixtures, have been shown to prevent and alleviate oxidative stress-related metabolic disorders due to their intrinsic ability to scavenge free radicals by providing an electron or a hydrogen atom [1,2]. Although polyphenols have low oral bioavailability mainly because of their extensive biotransformation in the intestine and liver, as well as by the gut microbiota [3,4,5], they exert remarkable beneficial effects, which lead to the low bioavailability/high bioactivity paradox.

The human body provides an ecosystem for the habitation of trillions of microbial cells, most of which reside in the gastrointestinal tract; the gut microbiota is most likely associated with metabolic events related to health and disease [6]. The involvement of the gut microbiota in several pathophysiological conditions has been suggested [7], leveraging the advances in genomic techniques, such as 16S and 18S ribosomal RNA sequencing and metagenomic sequencing [8,9].

Besides their effects on oxidative stress-related metabolic disorders, polyphenols substantially interact with the gut microbiota [10,11]. Because an imbalance in the quantity and quality of gut bacteria is associated with several metabolic disorders, the interaction of polyphenols and gut microbiota has been focused upon [1], and in the past decade, several studies have been carried out in this regard. However, the fundamental mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of polyphenols in relation to the gut microbiota have not yet been fully elucidated. Therefore, this review is aimed at describing the beneficial effects of polyphenols on metabolic disorders in light of their interactions with the gut microbiota.

As data on the effect of polyphenols on human gut microbiota based on human intervention studies are limited, we searched for studies on murine models of metabolic disorders in the PubMed database using the keywords “polyphenol AND gut microbiota AND (rat OR mouse)”. We selected articles from the last decade (2012–2021) discussing the relationship between the heath benefit action of polyphenols and the gut microbiota. Although polyphenols have a variety of compounds, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, and lignans, we focused on polyphenols in general including plant extracts. Additionally, we excluded the literature discussing the prebiotic action and phytoestrogenic action of polyphenols.

2. Beneficial Effects of Polyphenols on Metabolic Disorders in Relation to the Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet (HFD)-Fed Murine Models

HFD-fed mice and rats have been used as in vivo models of chronic metabolic disorders, such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, liver injury, and inflammatory dysfunction, and the beneficial effects of polyphenols have been studied using these models in relation to the modulation of the gut microbiota [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] as summarized in Table 1. In particular, as indicated by a previous study [30], oxidative stress, inflammation, and gut microbial disorders can be induced by long-term HFD. Therefore, an HFD model seems to be suitable for evaluating the putative modes of the action of polyphenols. Of polyphenols, resveratrol, a well-known sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) agonist, has been intensively studied. Resveratrol, alone or in combination with other polyphenolic compounds such as quercetin and sinapic acid or probiotics such as Bifidobacterium longum, alleviates effects of obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in HFD-fed mice [17,21,26,28,29,31]. Collectively, the beneficial effects of resveratrol are likely attributable to improved oxidative stress and gut microbial composition. Because the bioavailability of many polyphenols, including resveratrol, is low [35,36], they can be located in the bowel lumen when orally administered. Resveratrol can directly alter the composition of the gut microbiota by increasing the abundance of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria, such as Bacteroides and Blautia, and by decreasing the abundance of harmful bacteria, such as Desulfovibrio and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A316_group, as well as improving intestinal oxidative stress by preventing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and improving antioxidant defense mechanisms, for example, by enhancing superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione (GSH) levels [28,29]. The increase in these SCFA-producing bacteria could lead to the anti-obesity effects of resveratrol because these bacteria reportedly correlate negatively with inflammation, insulin resistance, and obesity [37,38]. Indeed, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from resveratrol-treated mice to HFD-fed mice resulted in decreased weight gain and increased insulin sensitivity in the latter [26]. Furthermore, resveratrol could improve the integrity of the gut intestinal barrier through the repair of intestinal mucosal morphology possibly due to improved intestinal redox status, which leads to amelioration of HFD-induced NAFLD [28], because the development of HFD-induced NAFLD is closely associated with a loss of tight junction proteins in the small intestine [39,40].

Table 1.

Beneficial effects of polyphenols in metabolic disorders in relation to the gut microbiota in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed murine models.

Aside from resveratrol, other polyphenols and polyphenol-rich extracts and substances also alleviate obesity, hyperlipidemia, liver injury, and inflammatory status secondary to the alteration of the gut microbiota composition [12,13,14,15,16,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,27,30,32,33,34]. Sinapine, a rapeseed polyphenol, ameliorated NAFLD, suppressed intestinal nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) expression, and enhanced adipose tissue insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) expression in HFD-fed mice [22]. Sinapine possibly manifested its effect by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota by decreasing the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes and increasing the abundance of probiotics. Phylum-level analyses of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes have revealed that a reduced population of Bacteroidetes or an increased population of Firmicutes is associated with obesity [41,42,43,44,45]. Among plant-origin polyphenol-rich extracts, the extracts of pomegranate peel, cranberry, cinnamon bark, grape and grape pomace, brown macroalga Lessonia trabeculata, Lonicera caerulea L. berries, and red pepper could attenuate obesity, hyperglycemia, or liver injury by alleviating oxidative stress and modulating the gut microbiota [12,14,15,19,24,25,27,32]. Polyphenol-rich beverages, food, and their ingredients also show beneficial effects on metabolic disorders in relation to the gut microbiota [13,16,18,23,30,33,34]. Tea, a popular beverage consumed worldwide, is known to contain catechins, such as epicatechin, epicatechin-3-gallate, epigallocatechin, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) [46]. Oral administration of tea polyphenols, such as polyphenols from fermented Pu-erh tea and fermented Fu brick tea mainly produced in China, ameliorated obesity and hyperlipidemia by ameliorating effects of inflammation and oxidative stress in the intestine, and improved intestinal barrier function, leading to reduced circulation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and modulation of the gut microbiota [16,18,23,34]. The tea polyphenols decreased the abundance of Proteobacteria, a source of LPS, and the Fu brick tea polyphenols increased phylogenetic diversity and decreased the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. Pu-erh tea polyphenols reduced circulation of LPS via restoration of gut barrier function and restored HFD-induced gut microbial community structural shift. Chronic consumption of commercially available instant caffeinated coffee also ameliorated obesity and decreased the Firmicutes/Bacteroides ratio [13]. Polyphenol extracts from Shanxi-aged vinegar showed similar effects [30]. Polyphenol-rich whole red grape juice could reduce oxidative stress and inflammatory status by activating the body’s antioxidant system, preventing free radical action, and beneficially modulating the gut microbiota, although it slightly affected the body composition such as body mass, fat mass, and lean mass, and body bone area [33].

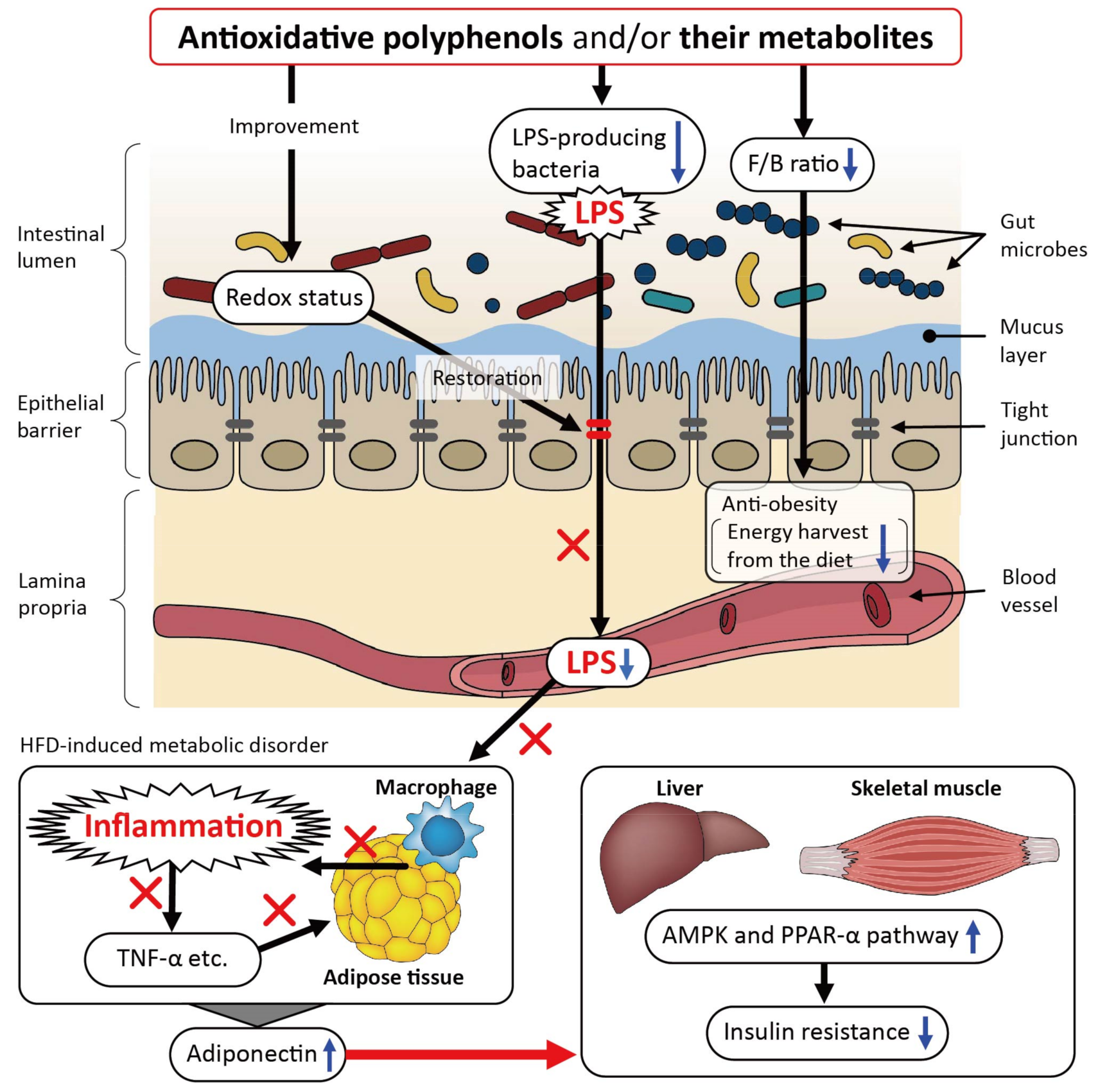

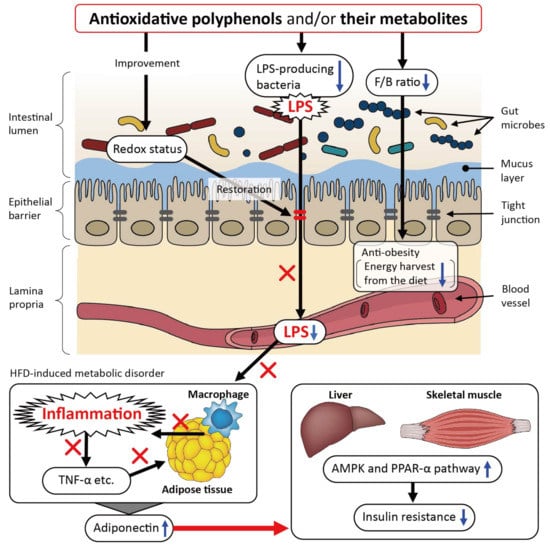

The proposed mode of action of polyphenols in HFD-induced metabolic disorders is illustrated in Figure 1. As reported previously, metabolic endotoxemia dysregulates the inflammatory tone mediated by infiltrated macrophages and triggers body weight gain and diabetes [47], and a previous meta-analysis revealed that elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines (interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-18, C-reactive protein) and TNF-α and low levels of adiponectin, an antidiabetic and antiatherogenic adipokine, are risk factors for type 2 diabetes [48]. Polyphenols decrease the abundance of bacteria, which are a source of LPS, and restore impaired intestinal tight junctions, possibly by improving the intestinal redox status, leading to lowered circulating LPS levels and alleviated inflammation in the adipose tissue. Subsequently, the levels of circulating adiponectin, an antidiabetic and antiatherogenic adipokine, can be restored, resulting in mitigating insulin resistance. This effect of adiponectin on insulin resistance appears to be mediated, at least in part, by an increase in fatty acid oxidation through activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and also through the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α in the muscles and liver [49,50,51,52,53]. The polyphenols also decrease the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, leading to an anti-obesity effect by depressing the increased capacity for energy harvest from the diet associated with obesity [44].

Figure 1.

The proposed mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of polyphenols on metabolic disorders in high-fat diet (HFD)-fed murine models. LPS: lipopolysaccharide; ROS: reactive oxygen species; F/B ratio: Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; PPAR-α: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α.

3. Beneficial Effects of Polyphenols on Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis in Relation to the Gut Microbiota in Murine Models

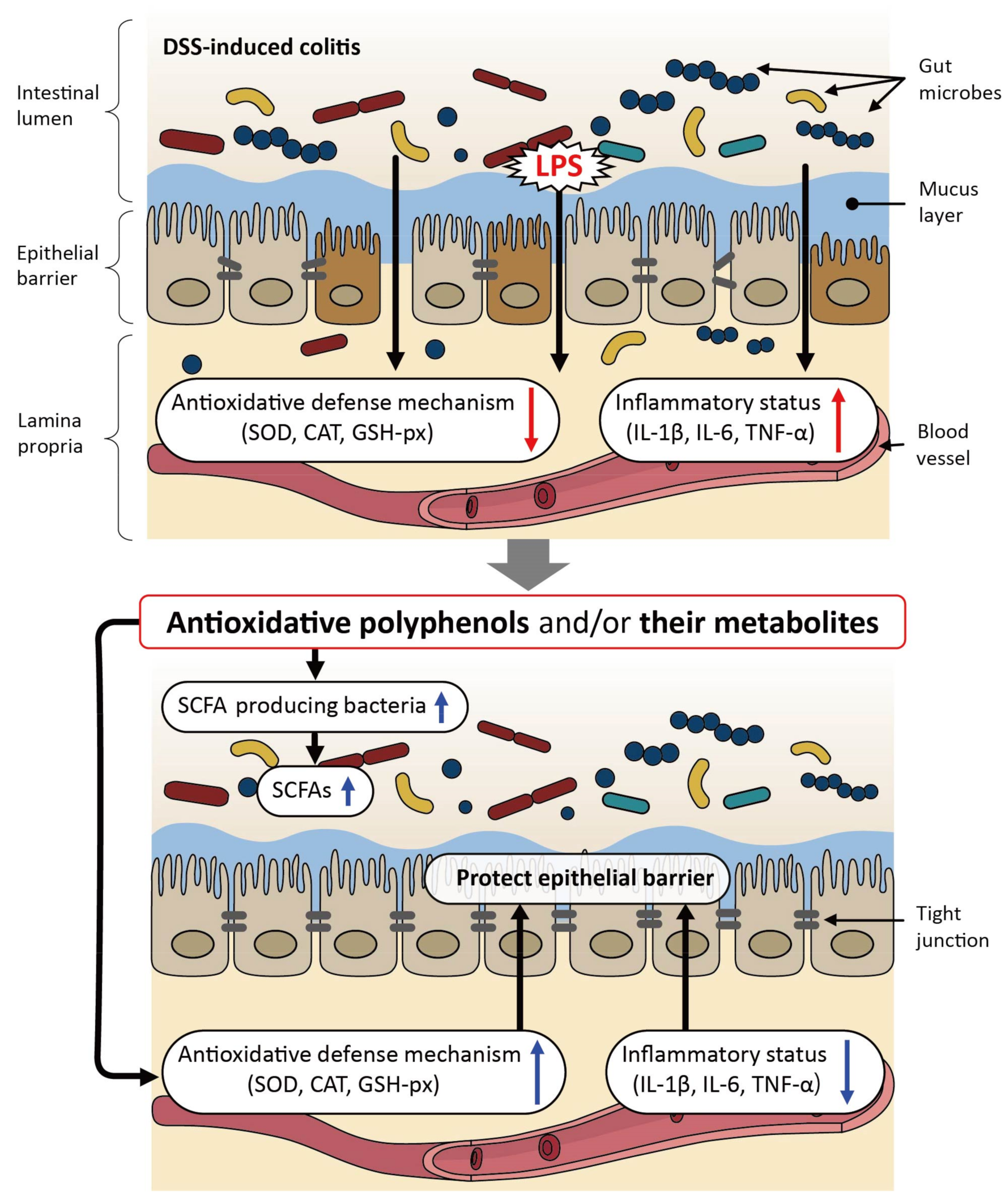

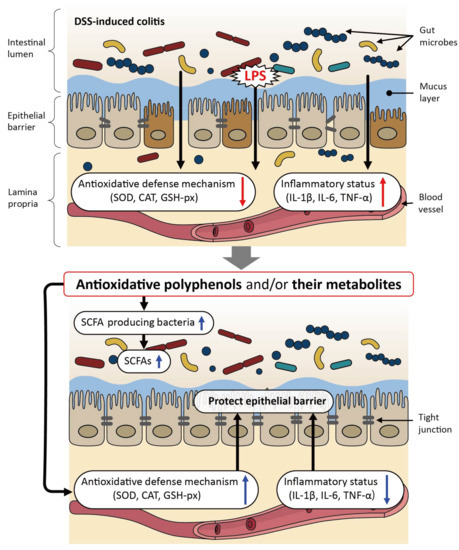

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is a recurrent and multifaceted inflammatory disorder requiring long-term medication [54,55]. DSS-induced colitis is an animal model of IBD, which has been used to study the beneficial effects of polyphenols in relation to the modulation of the gut microbiota [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65] as shown in Table 2. In these studies, the oral intake of single polyphenolic compounds, polyphenol-rich extracts, or polyphenol-rich food substances ameliorated DSS-induced colitis, enhanced colonic barrier integrity, improved oxidative balance and inflammatory status in the blood and/or colon, and modulated the gut microbiota. As for the prophylactic effects, oral pretreatment with bronze tomato extract, quercetin, quercetin monoglycosides, taxifolin, flavanonol, or EGCG prevented the development of DSS-induced colitis, suggesting that these polyphenols can prevent DSS-induced oxidative imbalance and changes in the microbial composition in the colon [58,60,63,64]. A study showed that rectal administration of EGCG tended to exacerbate DSS-induced colitis, indicating that the direct effects of this compound are unlikely to play a primary role in vivo [64]; we presume that biotransformed metabolite(s) of EGCG could be the main driver for its action. In contrast, FMT from EGCG-treated mice to DSS-treated mice (EGCG-FMT) resulted not only in the amelioration of colitis but also in an increased abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Akkermansia, which showed a positive correlation with antioxidative indices and a negative correlation with inflammatory indices [64]. These results suggest that gut microbiota modulation, especially an increase in SCFA-producing bacteria, and, subsequently, in functional SCFAs, plays a pivotal role in EGCG-treated mice with colitis. The proposed mode of action of polyphenols in DSS-induced colitis is illustrated in Figure 2. The DSS-induced intestinal and systemic oxidative imbalance can be ameliorated by polyphenols, leading to the restoration of the impaired epithelial barrier of the intestine. In addition, polyphenols can increase the number of SCFA-producing bacteria with a subsequent increase in SCFA production, further enhancing the epithelial barrier function.

Table 2.

Beneficial effects of polyphenols on dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in relation to the gut microbiota in murine models.

Figure 2.

The proposed mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of polyphenols on dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in murine models. SOD: superoxide dismutase; CAT: catalase; GSH-px: glutathione peroxidase; IL: interleukin; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; SCF: short-chain fatty acid.

4. Beneficial Effects of Polyphenols on Metabolic Disorders Not Associated with HFD or DSS in Relation to the Gut Microbiota in Murine Models

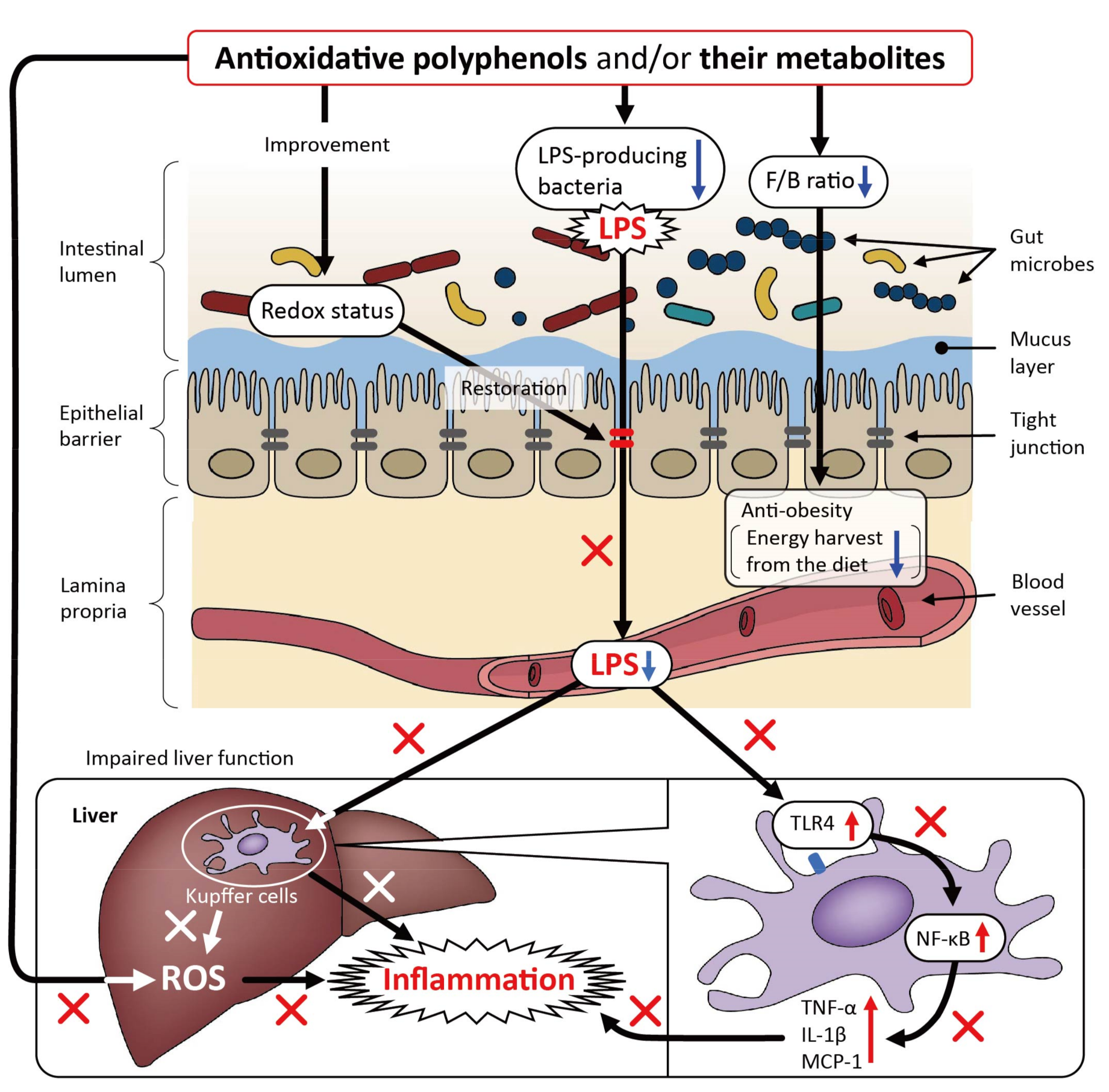

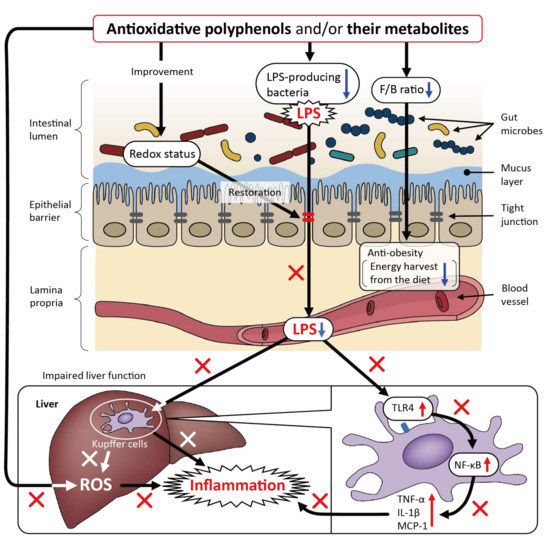

The beneficial effects of polyphenols on metabolic disorders not associated with HFD or DSS are summarized in Table 3. Several studies have explored the beneficial effects on liver injury in relation to the gut microbiota. They showed that regardless of the hepatic disorder induced by different factors, such as fructose- or western diet-induced NAFLD, and alcohol-, LPS-, or L-carnitine-induced liver injury, polyphenols could prevent or alleviate liver injuries, ameliorate oxidative stress and inflammatory status, and modulate the composition of the gut microbiota or maintain its normal composition [66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. Polyphenol-treated animals show improved intestinal barrier function and reduced blood LPS levels, with the latter likely contributing to the prevention of necrotic damage to the liver. Four of the six studies on the taxonomic analysis of gut bacteria at the phylum level showed a clear decrease in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [66,67,68,71]. In studies on fructose- and ethanol-induced liver dysfunction [66,68], it was observed that the LPS content and Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression in the liver were decreased by oral intake of polyphenols. The latter study also showed that the abundance of Bacteroidetes was negatively correlated with parameters of oxidative stress and inflammation and that of Firmicutes was positively correlated; however, the role of the decreased Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio in reduced liver inflammation was not discussed. Based on these results, a proposed mode of action of polyphenols on liver injuries induced by various factors is illustrated in Figure 3. Polyphenols can decrease the abundance of bacteria that are a source of LPS and enhance intestinal barrier function, possibly by improving intestinal redox status and lowering circulating LPS levels, which can, in turn, attenuate inflammation in the liver by suppressing the LPS-TLR4 signaling pathway in sinusoidal Kupffer cells.

Table 3.

Beneficial effects of polyphenols on metabolic disorders not associated with a high-fat diet (HFD) or dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in relation to the gut microbiota in murine models.

Figure 3.

The proposed mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of polyphenols on murine liver injuries induced by various factors, except for a high-fat diet. LPS: lipopolysaccharide; ROS: reactive oxygen species; F/B ratio: Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio; TLR: toll-like receptor; NF: nuclear factor; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; IL: interleukin; MCP: monocyte chemotactic protein.

Regarding metabolic disorders other than the liver injuries listed in Table 3, beneficial effects of polyphenols were reported on diabetic db/db mice, particulate matter ≤ 2.5 μm (PM2.5)-induced visceral adiposity, cafeteria diet-induced obesity, spontaneous hypertension, doxorubicin (an anti-cancer drug)-induced heart failure, and potassium oxonate-induced hyperuricemia [73,74,75,76,77,78]. Regardless of the experimental conditions and pathological sites, local and/or systemic oxidative stress-induced inflammation was reduced by polyphenol intake, along with altered gut microbiota. Regarding the involvement of gut microbiota in the actions of polyphenols, while in some studies it has been suggested that altered gut microbiota is the primary mechanism underlying the pharmacological actions of polyphenols [74,76], in others, it has been mentioned that further exploration is required to elucidate whether their beneficial effects are mediated by the gut microbiota [74,75,77].

5. Effects of Polyphenols on the Gut Microbiota in Healthy Mice and Rats

The effects of polyphenols on the gut microbiota of healthy animals have been reported [79,80,81,82] and are summarized in Table 4. A study showed that dietary supplementation of polyphenol-rich Jaboticaba (Plinia jaboticaba) peel extract altered the gut microbiota, increasing the abundance of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Enterobacteriaceae without disturbing the antioxidant system [79]. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium were reported to exert inhibitory actions against harmful bacteria, likely via pH reduction [83]. Three other studies reported that polyphenol-rich dietary plant materials enhanced the hepatic antioxidant capacity and positively modulated the gut microbiota, even in healthy animals. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was significantly reduced by the dietary supplementation of whole golden kiwifruit with peel [80] and by oral gavage of polyphenol-rich Penthorum chinense extract [81]. Long-term oral gavage of anthocyanin-rich Lycium ruthenicum Murray was reported to increase SCFA-producing bacteria and enhance the intestinal barrier function [82]. These studies indicate that beneficial effects on the gut microbiota along with enhanced intestinal barrier function and/or antioxidant capacity could be exerted even in healthy animals.

Table 4.

Effects of polyphenols on the gut microbiota in healthy mice and rats.

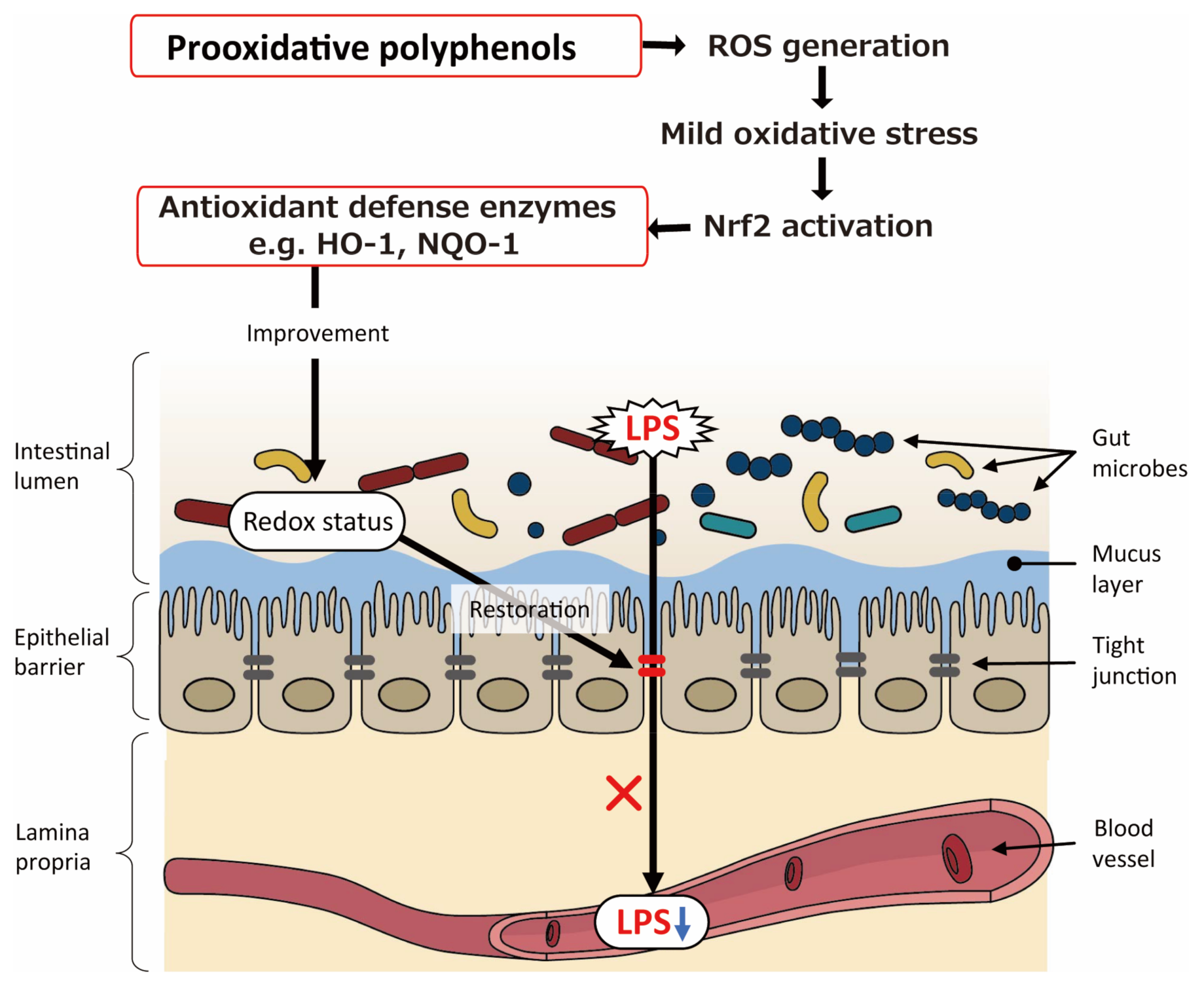

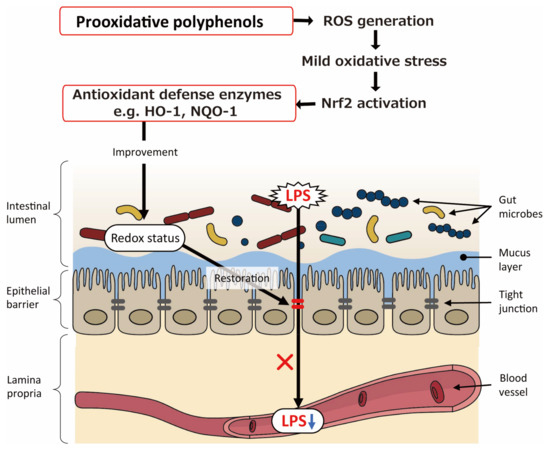

6. Possible Involvement of Prooxidative Potential of Polyphenols in Intestinal Barrier Function

As described above, improved intestinal barrier function is likely a key player for polyphenols’ ameliorative action on metabolic disorders. It has been questioned if polyphenols directly exert antioxidative action in situ [84,85]. Aside from polyphenols’ direct antioxidative action, they possess prooxidative potential; e.g., antibacterial activity of catechins [86] and cytocidal action of plant polyphenols on cancer cells [87], both of which are exerted by cytotoxic ROS generated by oxidation of phenolic hydroxyl moiety coupled with the reduction of dissolved oxygen. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) assumes the pivotal role in protecting cells, tissues, and organs owing to various genes encoding antioxidant proteins [88,89,90]. During ROS production by polyphenols, cells may activate the Nrf2 pathway independently of the polyphenols’ inherent antioxidant activity. This idea drove us to illustrate on possible involvement of prooxidative potential of polyphenols in intestinal barrier function (Figure 4). ROS generated by prooxidative polyphenols induces mild oxidative stress, which in turn activates Nrf2 followed by induction of antioxidant defense enzymes such as heme oxygenase 1 and NAD(P)H quinine oxidoreductase 1. These antioxidant enzymes could improve intestinal redox status, resulting in potentiated intestinal barrier function that prohibits LPS leakage to blood stream.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the possible involvement of prooxidative potential of polyphenols in intestinal barrier function. ROS: reactive oxygen species; Nrf2: nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; HO-1: heme oxygenase 1; NQO-1: NAD(P)H quinine oxidoreductase 1; LPS: lipopolysaccharide.

7. Future Perspective on Studies on Interaction of Polyphenols and Gut Microbiota

There are several issues that should be elucidated in the future studies. Given polyphenols’ poor absorbability from the digestive tract, their beneficial activity seems to be mediated through interaction with gut microbiota [91]. Accordingly, the number of studies on the interaction of polyphenols’ health beneficial effects and gut microbiota has gradually increased throughout this decade. Although many studies have shown that polyphenols could modulate gut microbiota, most studies failed to show how the polyphenols affected the microbiota on the basis of experimental evidence. In addition, while there have been many studies of polyphenol-rich plant extracts on this matter, there have been relatively a few studies of pure polyphenols. In other words, the possibility that components other than polyphenols could interact with gut microbiota still remains in the effects of plant extracts. Most of the studies performed chemical analyses of the polyphenols on the extracts; one study, for example, determined only the total polyphenol content along with carotenoid and capsinoid content, leaving us with the question of which component was a key player [32]. Next, despite the poor bioavailability of polyphenols, there have been very few reports on the in vivo fate of polyphenols in the literature we cited. To elucidate fundamental mechanisms, information on the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination (ADME) of target polyphenols would be essential. Finally, future studies should also investigate whether polyphenol prooxidant properties are involved in improving intestinal barrier function along with the modulation of gut microbiota via the activation of Nrf2 pathway. Although meaningful findings have been accumulated through the efforts of many researchers, solving the above problem would give a new perspective to the in vivo effects of polyphenols in relation to gut microbiota.

Lastly, we also address the critical reviewing of the literature listed in the tables. Although replace, refine, reduce—the 3 Rs of ethical animal research—are globally accepted, researchers are required to formulate experiments based on enough statistical power to ensure the results of animal experiments, e.g., the message from UK funding agencies is that some experiments use too few animals, a problem that leads to wastage and low-quality results [92]. The National Institutes of Health also sounded a warning that some irreproducible reports using animal models are probably the result of coincidental findings that happen to reach statistical significance, coupled with publication bias [93]. In the tables, the number of animals per group in some papers were five or less, without stating the validity of the sample size [20,58,67,74]. We have to carefully interpret the data in such studies from the point of view of reproducibility.

8. Conclusions

There have been many reports on the beneficial effects of polyphenols on metabolic disorders, and recent studies have focused on their interaction with the gut microbiota. In HFD-fed murine models, polyphenols could ameliorate obesity, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia by the alleviation of oxidative stress and inflammation in the intestine, the improvement of the intestinal barrier function, and the modulation of the gut microbiota, including a reduction in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio. In murine models of DSS-induced colitis, polyphenols could prevent or ameliorate oxidative imbalance, inflammatory status, and changes in the colonic microbial composition, with an increased abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria, leading to the protection of the intestinal epithelial barrier. In murine models of liver injuries not associated with HFD or DSS, polyphenols could improve the intestinal barrier function and reduced the blood LPS levels, which likely contributes to the prevention of necrotic damage in the liver, along with altered gut microbiota, including a reduction in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. Although some studies with FMT indicate a direct involvement of gut microbiota in the health benefits of polyphenols, further exploration is required in this regard.

Regarding the F/B ratio, it has been focused on by many researchers since the increased ratio was reported to be responsible for an increased capacity for energy harvest from diet [44]. Firmicutes and Bacteroides are the two main phyla of gut microbiota in mammals, playing important roles in maintaining gut microecological homeostasis [94]. Accordingly, it has been reported that alterations in the F/B ratio are associated with a variety of diseases [95,96,97]. However, there has been some inconsistency in the ratio even though similar experimental models were applied. For instance, in ovariectomized mice, one study showed an increased F/B ratio determined by a PCR analysis [98], but another one reported a decreased ratio determined by a 16s rDNA sequencing following DNA amplification by PCR [99]. In this review, five studies determined F/B ratios in Table 2, and among them one study revealed that the ratio increased [65], one study showed almost no change in the ratio [60], and the other three studies showed decreased ratios [56,58,63]. Thus, although the F/B ratio would be a good indicator to reflect gut microecological homeostasis, data should be carefully checked from the point of view of the following: which assay was applied for phylum level analysis, what timing of fecal sampling, how much the ratio changed, and so on.

Finally, the studies investigated thus far are limited to murine models, so that the findings cannot be extrapolated to humans. A review on the bioavailability of phytoestrogens such as isoflavones in murine models [100] noted that data should be carefully interpreted because of the large interspecies variability in the metabolism of phytoestrogens in murine models (e.g., their limited intestinal absorption and rapid excretion, compared to humans). Thus, data from murine models must be interpreted with great caution. In addition, given polyphenols’ poor absorbability in the digestive tract, their activity toward the human host seems to be mediated through interaction with intestinal microbes [101,102]. Considering transformation of dietary polyphenols by gut microbiota, reactions of polyphenols and bacteria are based on the reduction and/or hydrolysis because of anaerobic conditions. A typical well-known example is the bacterial transformation of the soya isoflavone daidzein to equal [103,104,105], which possesses high binding affinity to the estrogen receptor [106]. The O-deglycosylation of flavonoids by gut microbiota was also shown by many studies [102]. A typical example of flavonoid transformation is rutin to quercetin. As demonstrated, flavonoid aglycones, but not their glycosides, may inhibit growth of some intestinal bacteria [107], so that quercetin may have a more inhibitory influence on the intestinal bacteria than rutin. These direct effects of transformed polyphenols on gut microbiota have not been fully discussed in the literature listed in the tables. Since information on ADME of the polyphenols or the extracts is poor, further studies should be conducted in terms of ADME to obtain more information on the interaction between polyphenols and gut microbiota.

Funding

This study was partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP20K09996).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Shirato, Shishido, and Nakamura are members of the Academia–Industry Collaboration Laboratory at Tohoku University Graduate School of Dentistry, which receives funding from Luke Co., Ltd. (Sendai, Japan). This academia–industry collaboration was examined and approved by the Conflict of Interest Management Committee of Tohoku University. Luke Co., Ltd. and the grant funder had no role in the conception of the study design, data collection and interpretation, or in the decision to submit the work for publication.

References

- Marranzano, M.; Rosa, R.L.; Malaguarnera, M.; Palmeri, R.; Tessitori, M.; Barbera, A.C. Polyphenols: Plant sources and food industry applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 4125–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajha, H.N.; Paule, A.; Aragonès, G.; Barbosa, M.; Caddeo, C.; Debs, E.; Dinkova, R.; Eckert, G.P.; Fontana, A.; Gebrayel, P.; et al. Recent advances in research on polyphenols: Effects on microbiota, metabolism, and health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 66, e2100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, S.V.; Macovei, I.; Bujor, A.; Miron, A.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Trifan, A. Bioactivity of dietary polyphenols: The role of metabolites. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 626–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelli, A.; Biagi, M.; Corsini, M.; Baini, G.; Cappellucci, G.; Miraldi, E. Polyphenols: From theory to practice. Foods 2021, 10, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Aguirre, C.E.; Cortés-Martín, A.; Ávila-Gálvez, M.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; Selma, M.V.; González-Sarrías, A.; Espín, J.C. Main drivers of (poly)phenol effects on human health: Metabolite production and/or gut microbiota-associated metabotypes? Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10324–10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, S.; Sharma, D. The microbiome-estrogen connection and breast cancer risk. Cells 2019, 8, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Raka, F.; Adeli, K. The role of the gut microbiota in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Integrative HMP (iHMP) Research Network Consortium. The integrative human microbiome project: Dynamic analysis of microbiome-host omics profiles during periods of human health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saint-Georges-Chaumet, Y.; Edeas, M. Microbiota-mitochondria inter-talk: Consequence for microbiota-host interaction. Pathog. Dis. 2016, 74, ftv096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Q. Roles of the polyphenol-gut microbiota interaction in alleviating colitis and preventing colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyrinck, A.M.; Van Hée, V.F.; Bindels, L.B.; De Backer, F.; Cani, P.D.; Delzenne, N.M. Polyphenol-rich extract of pomegranate peel alleviates tissue inflammation and hypercholesterolaemia in high-fat diet-induced obese mice: Potential implication of the gut microbiota. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cowan, T.E.; Palmnäs, M.S.; Yang, J.; Bomhof, M.R.; Ardell, K.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Vogel, H.J.; Shearer, J. Chronic coffee consumption in the diet-induced obese rat: Impact on gut microbiota and serum metabolomics. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhê, F.F.; Roy, D.; Pilon, G.; Dudonné, S.; Matamoros, S.; Varin, T.V.; Garofalo, C.; Moine, Q.; Desjardins, Y.; Levy, E.; et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract protects from diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and intestinal inflammation in association with increased Akkermansia spp. population in the gut microbiota of mice. Gut 2015, 64, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collins, B.; Hoffman, J.; Martinez, K.; Grace, M.; Lila, M.A.; Cockrell, C.; Nadimpalli, A.; Chang, E.; Chuang, C.C.; Zhong, W.; et al. A polyphenol-rich fraction obtained from table grapes decreases adiposity, insulin resistance and markers of inflammation and impacts gut microbiota in high-fat-fed mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 31, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, B.; Zhang, X.; Liao, Z.; Gu, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Wei, H.; Fang, X. The effect of green tea polyphenols on gut microbial diversity and fat deposition in C57BL/6J HFA mice. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 4956–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, W.; Tian, F.; Shen, H.; Zhou, M. A combination of quercetin and resveratrol reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed rats by modulation of gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 4644–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xie, Q.; Kong, P.; Liu, L.; Sun, S.; Xiong, B.; Huang, B.; Yan, L.; Sheng, J.; Xiang, H. Polyphenol- and caffeine-rich postfermented Pu-erh tea improves diet-induced metabolic syndrome by remodeling intestinal homeostasis in mice. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00601-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Hul, M.; Geurts, L.; Plovier, H.; Druart, C.; Everard, A.; Ståhlman, M.; Rhimi, M.; Chira, K.; Teissedre, P.L.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. Reduced obesity, diabetes, and steatosis upon cinnamon and grape pomace are associated with changes in gut microbiota and markers of gut barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 314, E334–E352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hu, R.; Nakano, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, M.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; He, J.; Hou, D.X. Modulation of gut microbiota by Lonicera caerulea L. berry polyphenols in a mouse model of fatty liver induced by high fat diet. Molecules 2018, 23, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, C.; Deng, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Hu, C.; Tang, H.; Huang, F. Sinapic acid and resveratrol alleviate oxidative stress with modulation of gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed rats. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Su, Q.; Liu, Y. Sinapine reduces non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3637–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, B.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Qin, R.; Lv, S.; Wang, S. Correlation analysis of intestinal redox state with the gut microbiota reveals the positive intervention of tea polyphenols on hyperlipidemia in high fat diet fed mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7325–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Geng, Y.; Zou, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C. Polyphenol-rich extracts from brown macroalgae Lessonia trabeculate attenuate hyperglycemia and modulate gut microbiota in high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 12472–12480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Long, X.; Yang, J.; Du, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Hou, C. Pomegranate peel polyphenols reduce chronic low-grade inflammatory responses by modulating gut microbiota and decreasing colonic tissue damage in rats fed a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 8273–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, D.; Ke, W.; Liang, D.; Hu, X.; Chen, F. Resveratrol-induced gut microbiota reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed mice. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cheng, Z.; Sun, X.; Si, X.; Gong, E.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Shu, C.; Ma, F.; Li, D.; et al. Lonicera caerulea L. polyphenols alleviate oxidative stress-induced intestinal environment imbalance and lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in HFD-fed rats by regulating the Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 and MAPK pathways. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, e1901315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Ke, W.; Chen, F.; Hu, X. Targeting the gut microbiota with resveratrol: A demonstration of novel evidence for the management of hepatic steatosis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 81, 108363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Gao, J.; Ke, W.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Liu, R.; Jia, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, F.; et al. Resveratrol reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed mice via modulating the composition and metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 156, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Zhao, C.; Tu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, T.; Luo, J.; et al. GC × GC-MS analysis and hypolipidemic effects of polyphenol extracts from Shanxi-aged vinegar in rats under a high fat diet. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 7468–7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Yang, W.; Mao, P.; Cheng, M. Combined amelioration of prebiotic resveratrol and probiotic Bifidobacteria on obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinisgalli, C.; Vezza, T.; Diez-Echave, P.; Ostuni, A.; Faraone, I.; Hidalgo-Garcia, L.; Russo, D.; Armentano, M.F.; Garrido-Mesa, J.; Rodriguez-Cabezas, M.E.; et al. The beneficial effects of red sun-dried Capsicum annuum L. Cv Senise extract with antioxidant properties in experimental obesity are associated with modulation of the intestinal microbiota. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, e2000812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Fonseca Cardoso, L.M.; de Souza Monnerat, J.A.; de Medeiros Silva, I.W.S.; da Silva Ferreira Fiochi, R.; da Matta Alvarez Pimenta, N.; Mota, B.F.; Dolisnky, M.; do Carmo, F.L.; Barroso, S.G.; da Costa, C.A.S.; et al. Beverages rich in resveratrol and physical activity attenuate metabolic changes induced by high-fat diet. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2021, 40, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, K.B.; Huang, J.A.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhu, M.Z. Polyphenols from Fu brick tea reduce obesity via modulation of gut microbiota and gut microbiota-related intestinal oxidative stress and barrier function. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 14530–14543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbidelli, L. Polyphenol-based nutraceuticals for the control of angiogenesis: Analysis of the critical issues for human use. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 111, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Quintanar, L.; López Roa, R.I.; Quintero-Fabián, S.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.A.; Vizmanos, B.; Ortuño-Sahagún, D. Phytochemicals that influence gut microbiota as prophylactics and for the treatment of obesity and inflammatory diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 9734845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Xu, J.; Lian, F.; Yu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, X.; Shen, J.; Wu, S.; et al. Structural alteration of gut microbiota during the amelioration of human type 2 diabetes with hyperlipidemia by metformin and a traditional Chinese herbal frmula: A multicenter, randomized, open label clinical trial. mBio 2018, 9, e02392-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, D.; Hu, X.; Chen, F. Beneficial effects of ginger on prevention of obesity through modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmann, C.; Priebs, J.; Landmann, M.; Degen, C.; Engstler, A.J.; Jin, C.J.; Gärttner, S.; Spruss, A.; Huber, O.; Bergheim, I. Diets rich in fructose, fat or fructose and fat alter intestinal barrier function and lead to the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over time. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellmann, C.; Degen, C.; Jin, C.J.; Nier, A.; Engstler, A.J.; Hasan Alkhatib, D.; De Bandt, J.P.; Bergheim, I. Oral arginine supplementation protects female mice from the onset of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eckburg, P.B.; Bik, E.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Purdom, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Sargent, M.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Relman, D.A. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 2005, 308, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11070–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, X.; Xia, X.; Tang, R.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, K. Development of a real-time PCR method for Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in faeces and its application to quantify intestinal population of obese and lean pigs. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Hamady, M.; Yatsunenko, T.; Cantarel, B.L.; Duncan, A.; Ley, R.E.; Sogin, M.L.; Jones, W.J.; Roe, B.A.; Affourtit, J.P.; et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 2009, 457, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, C.S.; Prabhu, S.; Landau, J. Prevention of carcinogenesis by tea polyphenols. Drug Metab. Rev. 2001, 33, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.; Feng, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Hua, M. Adiponectin, TNF-α and inflammatory cytokines and risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cytokine 2016, 86, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S.; Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W. Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature 2000, 405, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Minokoshi, Y.; Ito, Y.; Waki, H.; Uchida, S.; Yamashita, S.; Noda, M.; Kita, S.; Ueki, K.; et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, E.; Tsao, T.S.; Saha, A.K.; Murrey, H.E.; Zhang, C.C.; Itani, S.I.; Lodish, H.F.; Ruderman, N.B. Enhanced muscle fat oxidation and glucose transport by ACRP30 globular domain: Acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibition and AMP-activated protein kinase activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 16309–16313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, B.B.; Alquier, T.; Carling, D.; Hardie, D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase: Ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okada-Iwabu, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Iwabu, M.; Honma, T.; Hamagami, K.; Matsuda, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Tanabe, H.; Kimura-Someya, T.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. A small-molecule AdipoR agonist for type 2 diabetes and short life in obesity. Nature 2013, 503, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostic, A.D.; Xavier, R.J.; Gevers, D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: Current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Danese, S.; Fiocchi, C.; Panés, J. Drug development in IBD: From novel target identification to early clinical trials. Gut 2016, 65, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Cao, S.; Cromie, M.; Shen, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, L. Chlorogenic acid ameliorates experimental colitis by promoting growth of Akkermansia in mice. Nutrients 2017, 9, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ohno, M.; Nishida, A.; Sugitani, Y.; Nishino, K.; Inatomi, O.; Sugimoto, M.; Kawahara, M.; Andoh, A. Nanoparticle curcumin ameliorates experimental colitis via modulation of gut microbiota and induction of regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scarano, A.; Butelli, E.; De Santis, S.; Cavalcanti, E.; Hill, L.; De Angelis, M.; Giovinazzo, G.; Chieppa, M.; Martin, C.; Santino, A. Combined dietary anthocyanins, flavonols, and stilbenoids alleviate inflammatory bowel disease symptoms in mice. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, K.; Jin, X.; Li, Q.; Sawaya, A.; Le Leu, R.K.; Conlon, M.A.; Wu, L.; Hu, F. Propolis from different geographic origins decreases intestinal inflammation and Bacteroides spp. populations in a model of DSS-induced colitis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Piao, M. Effect of quercetin monoglycosides on oxidative stress and gut microbiota diversity in mice with dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8343052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhao, H.; Cheng, N.; Cao, W. Rape bee pollen alleviates dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis by neutralizing IL-1β and regulating the gut microbiota in mice. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Cheng, N.; Zhou, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Gao, H.; Xue, X.; Wu, L.; Cao, W. Honey polyphenols ameliorate DSS-induced ulcerative colitis via modulating gut microbiota in rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Hu, M.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Ma, L.; Xu, Q. Dietary taxifolin protects against dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis via NF-κB signaling, enhancing intestinal barrier and modulating gut microbiota. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 631809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, S.; Li, T.; Li, N.; Han, D.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z.Z.; Zhang, S.; Pang, J.; Wang, S.; et al. Gut microbiota from green tea polyphenol-dosed mice improves intestinal epithelial homeostasis and ameliorates experimental colitis. Microbiome 2021, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Tsao, R.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, L.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, H. Green pea (Pisum sativum L.) hull polyphenol extracts ameliorate DSS-induced colitis through Keap1/Nrf2 pathway and gut microbiota modulation. Foods 2021, 10, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X. Polyphenol-rich loquat fruit extract prevents fructose-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by modulating glycometabolism, lipometabolism, oxidative stress, inflammation, intestinal barrier, and gut microbiota in mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7726–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; He, X.; Chen, K.; Sakao, K.; Hou, D.X. Ameliorative effects and molecular mechanisms of vine tea on western diet-induced NAFLD. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5976–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Duan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Geng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, M. Polyphenol-rich vinegar extract regulates intestinal microbiota and immunity and prevents alcohol-induced inflammation in mice. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 110064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Mehmood, A.; Soliman, M.M.; Iftikhar, A.; Iftikhar, M.; Aboelenin, S.M.; Wang, C. Protective effects of ellagic acid against alcoholic lver disease in mice. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 744520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Yan, T.; Tong, Y.; Deng, H.; Tan, C.; Wan, M.; Wang, M.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y. Gut microbiota modulation by polyphenols from Aronia melanocarpa of LPS-induced liver diseases in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3312–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, L.; Chen, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ren, D.; Yang, X. Chlorogenic acid inhibits trimethylamine-N-oxide formation and remodels intestinal microbiota to alleviate liver dysfunction in high L-carnitine feeding mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10500–10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezhibovsky, E.; Knowles, K.A.; He, Q.; Sui, K.; Tveter, K.M.; Duran, R.M.; Roopchand, D.E. Grape polyphenols attenuate diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis in mice in association with reduced butyrate and increased markers of intestinal carbohydrate oxidation. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 675267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.W.; Chen, H.P.; He, Y.Y.; Chen, W.L.; Chen, J.W.; Gao, L.; Hu, H.Y.; Wang, J. Effects of rich-polyphenols extract of Dendrobium loddigesii on anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and gut microbiota modulation in db/db mice. Molecules 2018, 23, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, N.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Yang, K.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; Wen, D. Hydroxytyrosol prevents PM(2.5)-induced adiposity and insulin resistance by restraining oxidative stress related NF-κB pathway and modulation of gut microbiota in a murine model. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 141, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guirro, M.; Gual-Grau, A.; Gibert-Ramos, A.; Alcaide-Hidalgo, J.M.; Canela, N.; Arola, L.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J. Metabolomics elucidates dose-dependent molecular beneficial effects of hesperidin supplementation in rats fed an obesogenic diet. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yao, Y.; Liu, T.; Yin, L.; Man, S.; Ye, S.; Ma, L. Polyphenol-rich extract from Litchi chinensis seeds alleviates hypertension-induced renal damage in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, N.; Kan, J.; Tang, S.; Sun, R.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Jin, C. Polyphenols from Arctium lappa L ameliorate doxorubicin-induced heart failure and improve gut microbiota composition in mice. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 46, e13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, E.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, N.; Cao, W. Impact of Camellia japonica bee pollen polyphenols on hyperuricemia and gut microbiota in potassium oxonate-induced mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva-Maia, J.K.; Batista, A.G.; Correa, L.C.; Lima, G.C.; Bogusz Junior, S.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Aqueous extract of berry (Plinia jaboticaba) byproduct modulates gut microbiota and maintains the balance on antioxidant defense system in rats. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, A.; Li, T.; Nisar, T.; Ren, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X. Consumption of two whole kiwifruit (Actinide chinensis) per day improves lipid homeostasis, fatty acid metabolism and gut microbiota in healthy rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Ren, W.; Wei, B.; Huang, H.; Li, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, A.; Xiao, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Characterization of chemical composition and prebiotic effect of a dietary medicinal plant Penthorum chinense Pursh. Food Chem. 2020, 319, 126568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wan, P.; Dong, W.; Huang, K.; Ran, L.; Mi, J.; Lu, L.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y. Effects of long-term intake of anthocyanins from Lycium ruthenicum Murray on the organism health and gut microbiota in vivo. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likotrafiti, E.; Rhoades, J. Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and foodborne illness. In Bioactive Foods in Health Promotion: Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Hollman, P.C.; Cassidy, A.; Comte, B.; Heinonen, M.; Richelle, M.; Richling, E.; Serafini, M.; Scalbert, A.; Sies, H.; Vidry, S. The biological relevance of direct antioxidant effects of polyphenols for cardiovascular health in humans is not established. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 989s–1009s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Croft, K.D. Dietary polyphenols: Antioxidants or not? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 595, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arakawa, H.; Maeda, M.; Okubo, S.; Shimamura, T. Role of hydrogen peroxide in bactericidal action of catechin. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, H.Y.; Zubair, H.; Faisal, M.; Ullah, M.F.; Farhan, M.; Sarkar, F.H.; Ahmad, A.; Hadi, S.M. Plant polyphenol induced cell death in human cancer cells involves mobilization of intracellular copper ions and reactive oxygen species generation: A mechanism for cancer chemopreventive action. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.O.; Kieran, N.E.; Howell, K.; Burne, M.J.; Varadarajan, R.; Dhakshinamoorthy, S.; Porter, A.G.; O’Farrelly, C.; Rabb, H.; Taylor, C.T. Reoxygenation-specific activation of the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 mediates cytoprotective gene expression in ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2624–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, L.M.; Park, B.K.; Copple, I.M. Role of Nrf2 in protection against acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 1090–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.E.; Tran, K.; Smith, C.C.; McDonald, M.; Shejwalkar, P.; Hara, K. The role of the Nrf2/ARE antioxidant system in preventing cardiovascular diseases. Diseases 2016, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milutinović, M.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M. Plant Extracts Rich in Polyphenols as Potent Modulators in the Growth of Probiotic and Pathogenic Intestinal Microorganisms. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 688843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, D. UK funders demand strong statistics for animal studies. Nature 2015, 520, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collins, F.S.; Tabak, L.A. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature 2014, 505, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahowald, M.A.; Rey, F.E.; Seedorf, H.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fulton, R.S.; Wollam, A.; Shah, N.; Wang, C.; Magrini, V.; Wilson, R.K.; et al. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5859–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Yadava, K.; Sichelstiel, A.K.; Sprenger, N.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Blanchard, C.; Junt, T.; Nicod, L.P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Santisteban, M.M.; Rodriguez, V.; Li, E.; Ahmari, N.; Carvajal, J.M.; Zadeh, M.; Gong, M.; Qi, Y.; Zubcevic, J.; et al. Gut dysbiosis is linked to hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, G.; Asou, Y.; Ishiyama, K.; Okawa, A.; Kanno, T.; Niwano, Y. Proanthocyanidin-Rich Grape Seed Extract Modulates Intestinal Microbiota in Ovariectomized Mice. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 1149–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhuge, A.; Li, L.; Ni, S. Gut microbiota modulates osteoclast glutathione synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis in mice subjected to ovariectomy. Cell Prolif. 2022, 55, e13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.; Faughnan, M.; Hoey, L.; Wähälä, K.; Williamson, G.; Cassidy, A. Bioavailability of phyto-oestrogens. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89 (Suppl. 1), S45–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T.; Satora, P.; Sroka, P. Interaction of dietary compounds, especially polyphenols, with the intestinal microbiota: A review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braune, A.; Blaut, M. Bacterial species involved in the conversion of dietary flavonoids in the human gut. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yokoyama, S.; Suzuki, T. Isolation and characterization of a novel equol-producing bacterium from human feces. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2008, 72, 2660–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matthies, A.; Blaut, M.; Braune, A. Isolation of a human intestinal bacterium capable of daidzein and genistein conversion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1740–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Setchell, K.D.; Clerici, C. Equol: History, chemistry, and formation. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1355s–1362s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Setchell, K.D.; Clerici, C.; Lephart, E.D.; Cole, S.J.; Heenan, C.; Castellani, D.; Wolfe, B.E.; Nechemias-Zimmer, L.; Brown, N.M.; Lund, T.D.; et al. S-equol, a potent ligand for estrogen receptor beta, is the exclusive enantiomeric form of the soy isoflavone metabolite produced by human intestinal bacterial flora. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duda-Chodak, A. The inhibitory effect of polyphenols on human gut microbiota. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 63, 497–503. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).