Simple Summary

Extracts and bioactive compounds from Artemisia annua have demonstrated activity against SARS-CoV-2 in laboratory studies and cell-based assays. Compounds like artemisinin showed potential to inhibit key viral proteins like the main protease (Mpro), interfering with virus replication. Rutin and quercetin derivatives, present in Artemisia extracts, have antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses. Beyond direct antiviral activity, Artemisia extracts exhibit immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, potentially reducing COVID-19-associated inflammation and oxidative stress.

Abstract

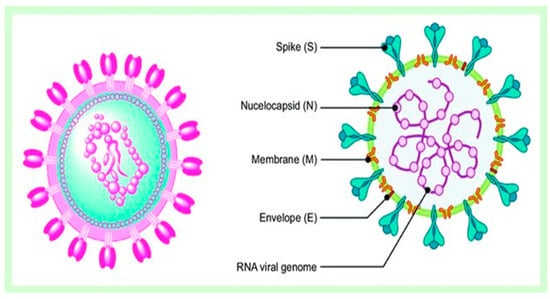

This review highlights Artemisia annua, a medicinal plant which grows in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, known for its abundant therapeutic properties. A. annua serves as a rich source of various bioactive compounds, including sesquiterpenoid lactones, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and coumarins. Among these, artemisinin and its derivatives are most extensively studied due to their potent antimalarial properties. Extracts and isolates of A. annua have demonstrated a range of therapeutic effects, such as antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antimalarial, and antiviral properties. Given its significant antiviral activity, A. annua could be investigated for the development of new nutraceutical bioactive compounds to combat SARS-CoV-2. Artificial Intelligence (AI) can assist in drug discovery by optimizing the selection of more effective and safer natural bioactives, including artemisinin. It can also predict potential clinical outcomes through in silico modeling of protein–ligand interactions. In silico studies have reported that artemisinin and its derivatives possess a strong ability to bind with the Lys353 and Lys31 hotspots of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, demonstrating their effective antiviral effects against COVID-19. This integrated approach may accelerate the identification of effective and safer natural antiviral agents against COVID-19.

1. Introduction

In traditional medicine, medicinal plants are a valuable source of drugs that are useful in treating a wide range of illnesses. Bioactive compounds are natural substances that can have beneficial effects on living organisms. In plants, these compounds act as a defense mechanism, helping to protect against pests, diseases, and harsh environmental conditions. For humans, bioactive compounds offer significant health benefits, including antioxidants, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties [1]. In Saudi Arabia, people have relied on medicinal plants alongside modern medicine for centuries to treat various health issues. For instance, Nigella sativa, commonly known as black seed, is traditionally used to boost the immune system and address respiratory problems [2]. Ziziphus spina-christi is well-known for its effectiveness in managing diabetes and digestive disorders [2]. Additionally, Aloe vera is frequently applied to relieve skin issues and promote healing. This combination of traditional herbal remedies and conventional treatments reflects the strong cultural trust in natural medicine throughout Saudi Arabia and highlights its significant role in healthcare today [3]. In real terms, traditional Islamic and Arab medicine dates back thousands of years and is a well-known form of treatment in many of these nations. In order to remedy, diagnose, and prevent illnesses as well as preserve overall health, this traditional medicine refers to healing practices and philosophy that integrate herbal medications, spiritual therapies, and dietary practices [2,3]. Acute respiratory distress syndrome is the outcome of immunological dysregulation and cytokine storm brought on by the release of inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 patients. COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and is an ongoing public health emergency [4].

Adopting natural products (NPs) may enhance immunity and offer protection against negative effects safely, often resulting in fewer side effects compared to synthetic medications. The research that is currently available supports the use of NPs against SARS-CoV-2 because of their immune-supportive, antioxidant, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and preventative properties. Natural products regulate immune function by controlling adaptive immunity in a multidirectional fashion, as stated by Boozari and Hosseinzadeh [4].

4. Artemisia Annua

4.1. Morphology and Distribution

The Artemisia L. genus includes annual or perennial flowering herbs and small shrubs from the Asteraceae family. These plants are known locally as wormwood, sagewort, and sagebrush, and there are approximately 500 species distributed across Asia, Africa, Australia, Central and South America, and Europe [22]. These plants demonstrated noteworthy economic and ecological benefits due to their valuable ethnobotanical uses, such as medicinal herbs, food sources in many areas of the world, and livestock feed [23]. Artemisia annua (Figure 2) is one of the most important plants of the genus Artemisia, which is a fragrant flowering herb with an erect stem. The leaves, which measure 3–5 cm in length, are entirely divided into two or three leaflets. The blooms are small, greenish-yellow, and approximately 2–2.5 mm in diameter, arranged in loose panicles. It is widely used as a culinary spice, herbal tea, and medicinal plant around the world [24]. In addition to A. annua, four additional species of Artemisia grow in Saudi Arabia, namely A. monosperma, A. sieberi, A. Judaica, and A. scoparia [25].

Figure 2.

Artemisia annua, stems, leaves, and flowers. (https://www.laboiteagraines.com/boutique/fleurs/graines-fleurs-annuelles/artemisia-annua-bio/ (accessed on 2 December 2025); https://www.heistek-mht.nl/onze-praktijk/diverse-%28medische%29-artikelen/artemisia-annua/ (accessed on 2 December 2025)).

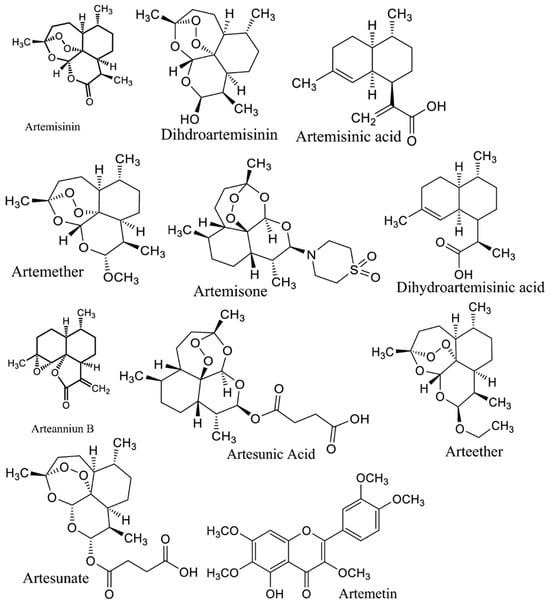

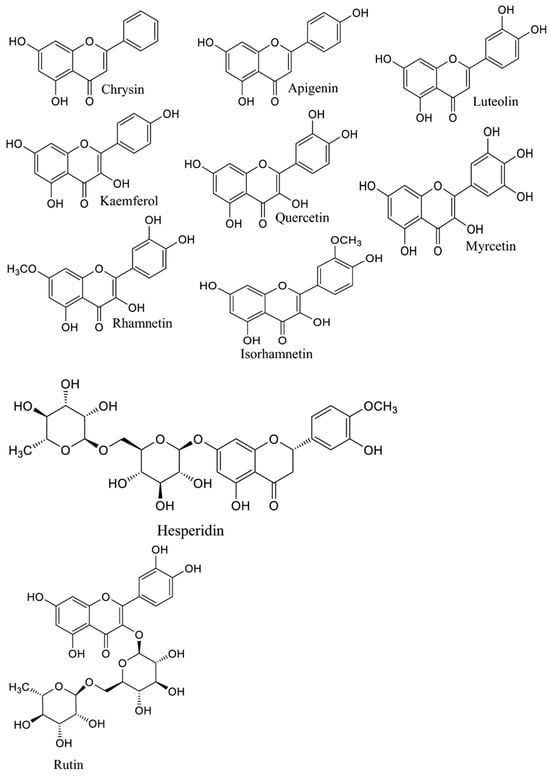

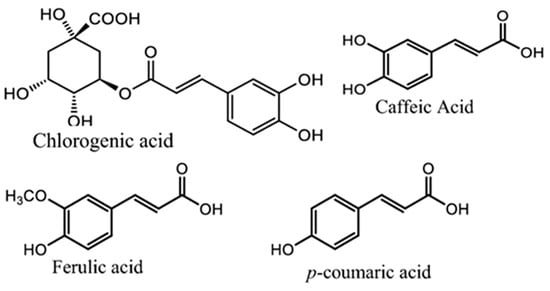

4.2. Phytochemical Constituents

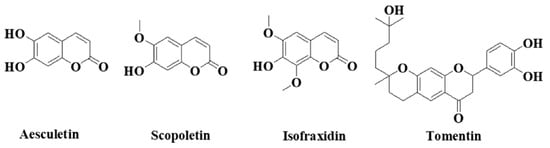

A. annua contains abundant bioactive molecules. Artemisinin and its derivatives, the antimalarial bioactive lactone sesquiterpenes isolated from A. annua, are the most extensively studied. Moreover, many bioactive ingredients of various categories, which are presented in Table 1, including sesquiterpenoid lactones (Figure 3), flavonoids (Figure 4), phenolic acids (Figure 5), and coumarins (Figure 6), have been identified in the different extracts of A. annua [25,26,27]. In addition, many bioactive terpenes have been identified in the essential oil of A. annua [28,29]. Moreover, Brisibe et al. [30] demonstrated that A. annua is a rich source of nutritious phytochemicals, such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and other essentials for good health. Various sesquiterpene lactones have been identified in the aerial parts of A. annua; the major ones are artemisinin, artemisinic acid, and arteannuin B [31]. Quercetin, luteolin, apigenin, rutin, kaempferol, isorhamnetin, and casticin represent the major flavonoids in the aqueous and alcoholic extracts of A. annua, in addition to the phenolic acids of quinic acid, chlorogenic acid, and caffeic acid [31]. The alcoholic extracts of A. annua contain various bioactive coumarins, the main ones being scopoletin and scopoline [31]. 1, 8-Cineole, camphene, borneol, α-pinene, camphor, limonene, α-terpinene, carvone, and myrtenol represent the major terpenes found in the A. annua essential oils [28,29].

Table 1.

Major bioactive molecules identified in A. annua.

Figure 3.

Major sesquiterpene lactones in A. annua.

Figure 4.

Major flavonoids in A. annua.

Figure 5.

Major phenolic acids in A. annua.

Figure 6.

Major coumarins in A. annua.

4.3. Therapeutic Potential of A. annua

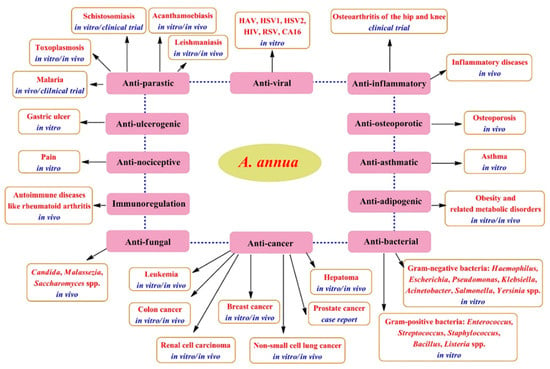

Artemisia species have been greatly utilized in traditional medicine to effectively remedy various illnesses, for example, malaria, typhoid fever, intestinal disorders, pneumonia, morning sickness, kidney problems, and epilepsy [3]. A. annua is significantly utilized in traditional Asian medicine to remedy wounds, jaundice, hemorrhoids, and bacterial dysentery. Moreover, it serves as a potent antipyretic drug for tuberculosis and malaria, as well as other bacterial, viral, and autoimmune illnesses [27]. Various pharmacological investigations have shown the medicinal benefits of A. annua extracts and essential oils (Figure 7), including their outstanding ability to promote the immune system and exert strong antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antiparasitic effects, as extensively reviewed by Feng et al. [31], Septembre-Malaterre et al. [36], and Ekiert et al. [27].

Figure 7.

Therapeutic potentials of A. annua [31].

4.4. Antioxidant Potentials of A. annua

Numerous investigations have revealed the potent antioxidant potential of A. annua essential oils and extracts, which might be caused by its abundance of bioactive ingredients of flavonoids, coumarins, and terpenes [37]. The crude ethanolic extract of A. annua and its fractions showed potent antioxidant potential using in vitro tests of iron (II) chelating, ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), cupric reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC), DPPH, and ABTS; the superior effects were for the crude extract compared to its fractions [37]. A. annua extracts and essential oils from different countries showed antioxidant effects in in vitro assays, including DPPH, ABTS, Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC), and metal chelation [38,39].

4.5. Anti-Inflammatory Potentials of A. annua

A. annua extracts and their major bioactive artemisinin demonstrated strong anti-inflammatory potentials in both in vitro and in vivo models. A. annua tea solution lowered inflammation in Caco-2 cells by suppressing IL-6 and IL-8 generation, probably thanks to the presence of rosmarinic acid, a major phenolic molecule identified in the extract [40]. The aqueous, methanolic, ethanolic, and acetone extracts of A. annua effectively reduced inflammation in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages at a concentration of 100 µg/mL [41]. The acetone extract with the highest artemisinin concentration had the maximum inhibitory impact on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and IL-10), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and nitric oxide (NO) [41]. In LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages, the ethanol extract of A. annua and its isolated compounds: scopoletin, artemisinin, chrysosplenetin, 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside of sitosterol, and eupatin, effectively inhibited inflammation by preventing the release of NO [42]. In croton oil-induced edema and LPS-induced inflammation in mice, casticin and chrysosplenol D, two major flavonoids isolated from A. annua, revealed dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effects. They successfully suppressed the generation of inflammatory mediators by regulating NF-κB and c-JUN, verifying their effective role in inhibiting inflammation [43]. The bioactive sesquiterpenes lactone artemisinin and its derivatives, which are extensively isolated from A. annua, have established strong anti-inflammatory potentials in numerous inflammatory disease models, including allergic inflammation, septic inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. These effects arise through the downregulation of various pathways: the PI3K/Akt signalling cascade, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, the expression of Toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4) and 9 (TLR9), and NF-κB activation [44].

4.6. Immunomodulatory Potentials of A. annua

A. annua has a long history of utilization in ancient China for efficiently treating various autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, revealing its effective immunoregulatory properties [43]. A. annua ethanol extract efficiently suppressed immunological responses by inducing lymphocyte proliferation in mouse splenocytes initiated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and concanavalin A. Additionally, when administered intraperitoneally, the A. annua extract significantly reduced blood levels of IgG, IgG1, and IgG2b antibodies in mice that had been immunized with ovalbumen. It also prevented splenic enlargement [45]. The aqueous extract of A. annua showed substantial immunomodulatory ability by actively modulating essential components of the innate immune system, particularly Toll-like receptors TLR2 and TLR4 in the lungs and brains of mice infected with Acanthamoeba [46]. Numerous pharmacological studies demonstrated the substantial immunomodulatory potentials of artemisinin and its derivatives, dihydroartemisinin, artesunate, and artemether, extensively isolated from A. annua [44,47]. These compounds effectively influence the responses of various innate and adaptive immune cells. They significantly inhibit cytokine release and related signaling pathways, reduce neutrophils, suppress macrophage functionality, inhibit lymphocyte production and conservation, and influence various signaling paths, such as TLRs, Akt, PLCγ, MAPK, PKC, STATs, Wnt, Nrf2/ARE, and NF-κB [36,47].

4.7. Antimicrobial Potential of A. annua

Many research studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial abilities of A. annua essential oils and extracts against a variety of bacteria and fungi, including Gram-positive species of Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Enterococcus, Listeria, Staphylococcus, and Bacillus; Gram-negative species of Escherichia, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Haemophilus, Salmonella, and Yersinia; and fungi species of Candida, Saccharomyces, and Malassezia [26,27,28]. The essential oil of A. annua demonstrated remarkable antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranging from 0.51 to 16.33 mg/mL. It excellently combated a range of clinical microbes, including the Gram-negative bacteria P. aeruginosa, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii; Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus, B. subtilis, and E. faecalis; and yeasts C. famata, C. utilis, and C. albicans. Camphor, α-pinene, germacrene D, 1,8-cineole, trans-β-caryophyllene, and artemisia ketone represented the major constituents of A. annua essential oil and might be associated with its antibacterial properties [28]. The essential oil of A. annua demonstrated remarkable abilities to combat a variety of Malassezia fungi, including M. globosa, M. furfur, M. pachydermatis, M. sloffiae, and M. sympodialis, as well as Candida fungi, including C. krusei, C. dubliniensis, C. parapsilosis, C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. norvegensis. The major components of A. annua essential oil, camphor, 1,8-cineole, and artemisia ketone are responsible for its antifungal properties [48].

4.8. Anti-Malarial Potential of A. annua

Various reports have highlighted the anti-malarial properties of A. annua, leading to different herbal medications made from A. annua that are proposed for the inhibition and treatment of malaria [49,50,51]. Various clinical trials have verified that A. annua tea preparations efficiently alleviate malaria symptoms, with the cure rate directly associated with the dosage administered [49]. Artemisinin concentrations as low as 9 ng/mL have been established to suppress the growth and development of P. falciparum. Pharmacokinetic findings indicate that plasma artemisinin levels after drinking A. annua tea reach 9 ng/mL and continue at that level for at least four hours. This suggests that A. annua tea may contain abundant artemisinin to have effective therapeutic antimalarial properties [50]. Because of the high efficiency of artemisinin against P. falciparum, the World Health Organization (WHO) advises using artemisinin-based combination treatment (ACT) for treating uncomplicated malaria [51].

4.9. Antiviral Potentials of A. annua

Massive studies have confirmed the strong antiviral effectiveness of A. annua extracts and bioactive artemisinin derivatives against a range of DNA and RNA viruses [26,36]. Various extracts of A. annua have been evaluated against herpes simplex viruses (HSV), which are responsible for a range of human ailments, from severe encephalitis to herpes labialis. In HeLa cells, the methanol extract of A. annua displayed promising antiviral efficacy against HSV-1, superior to the effectiveness of acyclovir even at a low dose of 3.125 µg/mL [52]. Even though extracts such as petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol did not affect HSV-2, the aqueous extract of A. annua showed potent antiviral efficiency against HSV-2 in Vero cells, similar to that of acyclovir [53]. The main compounds identified in the aqueous extract were polyphenols and condensed tannins, which are supposed to be responsible for its anti-HSV properties [53]. A study by Lubbe et al. [54] established that an infusion of A. annua tea successfully inhibited human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vitro with an IC50 value of 2.0 µg/mL. Furthermore, A. annua extract and essential oil have established potent antiviral efficiency against Hepatitis A virus (HAV), coxsackievirus type A16 (CA16), and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) [26,55]. Numerous studies have displayed the significant antiviral efficiency of artemisinin and its derivatives, the major bioactive constituents in A. annua, against various viruses, including HSV-1, HSV-2, human herpesvirus 6, bovine viral diarrhea, and hepatitis B virus [56].

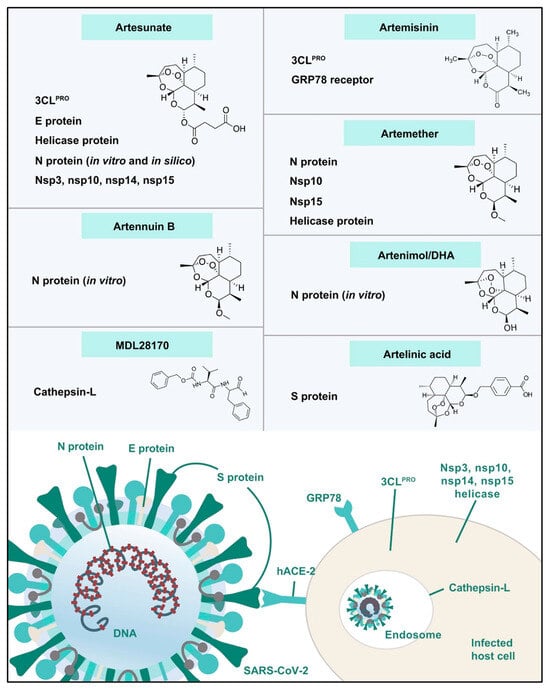

4.10. A. annua Potential in Combating SARS-CoV-2

Many studies have found that Artemisia spp. contains enough bioactive phytochemicals, especially polyphenols and artemisinin derivatives, which effectively combat viruses [26,36]. A growing body of research emphasizes the powerful efficiency of A. annua extracts and their bioactive ingredients, especially artemisinin, in combating coronaviruses. This promising indication shows the potential of these natural components in treating viral challenges. Lin et al. [57] first reported the effectiveness of A. annua against the SARS coronavirus that emerged in 2002. A. annua showed high efficiency to combat SARS-CoV-2 through inhibiting its replication and penetration with a EC50 of 1053.0 µg/mL and EC50 of 34.5 µg/mL [58]. In a recent in silico study, Sehailia and Chemat [59] reported that artemisinin and its derivatives demonstrate superior antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2 when compared to hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). This is due to their potent capacity to combine with the Lys353 and Lys31 hotspots of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The study found that artenilic acid achieved a better Vina docking score of −7.1 kcal/mol, while hydroxychloroquine had a score of −5.5 kcal/mol. The treatment with A. annua extract, plus artemisinin, artemether, and artesunate, significantly reduced SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro infection in Vero E6 cells, human lung cancer A549-hACE2 cells, and human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells. The efficiency of these treatments against COVID-19 was arranged as follows: artesunate > artemether > A. annua extract > artemisinin [60]. The hot aqueous extracts of five cultivars of A. annua exhibited effective in vitro antiviral potentials against various COVID-19 variants, including alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and kappa. The IC50 values ranged from 0.3 to 8.4 µM, while the IC90 values ranged from 1.4 to 25 µM. These results were compared to the positive control, artemisinin [61]. Extracts from Artemisia exhibited a potent ability to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro and Feline coronavirus (FCoV) at lower concentrations that did not affect cell efficacy and viability [62]. Abundant studies reported the potent antiviral efficiency of artemisinin and artemisinin-based compounds, including arteannuin B, artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin, against various COVID-19 variants [63,64]. Extracts of A. annua, artemisinin, and artemisinin-based compounds demonstrate various mechanisms that are responsible for their prospective anti-COVID-19 effects. These mechanisms include preventing the binding of COVID-19 spike proteins to host cell surfaces, thus inhibiting both the endocytosis of the virus and the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [59,65]. Artemisinin-based compounds demonstrated strong efficacy in binding to various COVID-19-host proteins, including the E protein, 3CLPRO, helicase protein, S protein, N protein, nonstructural protein 3 (nsp3), nsp10, nsp14, nsp15, the glucose-regulated protein 78 receptor, and cathepsin L, as illustrated in Figure 8 [66]. A. annua and its bioactive phyto-components have the potential to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) by promoting the host’s adaptive immunity. They do this by producing CD8 and CD4 lymphocytes, which are responsible for generating antibodies that target the virus. Additionally, these components help to suppress the generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and interleukins (IL-6) and (IL-10). This process can lead to an increased CD4 count and a higher CD4/CD8 ratio [23]. Moreover, artemisinin-based compounds may also help combat COVID-19 by mitigating cytokine storms in severe COVID-19. They achieve this by inhibiting IκB kinase (IKK) and, therefore, reducing intense NF-κB signaling. Alternatively, these compounds may prevent the transcriptional action of the p50/p65 dimer that is released during NF-κB signaling [65].

Figure 8.

Artemisinin-based compounds as potential COVID-19/host protein inhibitors [66].

4.11. Some Clinical Trials of Artemisia annua and Its Products

Various in vivo findings demonstrated that A. annua extract and its isolation, artemisinin, can decrease inflammatory reactions of cytokines like Tumor Necrosis Factor- alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6). These cytokines are of key cytokines that have been reported in “cytokine storm” caused harsh problems in SARS-CoV-2 patients experience. Additionally, artemisinin can reduce fibrosis, a severe condition that SARS-CoV-2 patients face, and can cause organs damages [67]. Consequently, Latarissa et al. [67], concluded that A. annua extract and its isolation, artemisinin, can combat SARS-CoV-2 through preventing the progress of cytokine storm and organs fibrosis. Moreover, the clinical trials assessing by Li et al. [68] found that antimalarial drugs, including Artemisinin–Piperaquine (AP), for COVID-19 were designed as randomized controlled trials focusing on evaluating the efficacy and safety of single antimalarial agents without combination therapies. These trials involved COVID-19 patients confirmed by PCR testing, mostly adults aged 18 years and older, with varying disease severities from mild to moderate. The studies compared the antimalarial interventions such as Quinine Sulfate (QS), Atovaquone (AQ), and Artemisinin–Piperaquine (AP), against control groups receiving either standard of care plus placebo or other comparators [68].

The primary outcomes typically focused on viral clearance measured by time to reach undetectable levels of SARS-CoV-2, while secondary outcomes included clinical status scales, oxygen supplementation incidence and duration, mechanical ventilation need, length of hospital stay, and safety indicators such as QT interval prolongation on electrocardiograms and adverse events. Among the drugs evaluated, Artemisinin–Piperaquine significantly shortened the time to viral clearance compared to the control group (10.6 days versus 19.3 days). However, it was also associated with a notable increase in the QT interval, underscoring the need for vigilant cardiac monitoring. In contrast, trials involving Quinine Sulfate and Atovaquone did not demonstrate statistically significant improvements in both primary and secondary outcomes, although some descriptive findings suggested possible benefits.

It is important to note that the primary outcomes in the clinical study were the primary endpoints that assessed the drug’s efficacy directly. Although they were not the primary focus of the trial, secondary outcomes comprised further measurements that provided additional information about the medication’s effects and safety.

In vivo studies by Xu et al. [69] investigated the enhanced therapeutic effects of whole-plant extracts of A. annua compared to pure artemisinin. The researchers prepared natural artemisinin-based combination therapies (nACTs) and tested their biological activity in two murine malaria models, where nACTs showed a roughly tenfold greater antimalarial effect than artemisinin alone at equivalent doses. Pharmacokinetic studies in rats revealed that oral administered nACTs prolonged half-life, and extended mean residence time, indicating slower drug elimination and better systemic absorption. Cellular assays using Caco-2 cells demonstrated that the extracts modulated P-glycoprotein activity and reduced artemisinin efflux, primarily through components such as deoxyartemisinin, artemisinic acid, and dihydroartemisinic acid [69].

A. annua extracts (nACTs) demonstrated approximately ten times greater in vivo antimalarial activity than pure artemisinin at the same dose, according to the findings published by Xu et al. [69]. Since the extracts contain other bioactive components such deoxyartemisinin, artemisinic acid, and dihydroartemisinic acid, this improvement is thought to be the result of several causes acting together. These bioactive substances are known to improve the absorption and retention of artemisinin by blocking P-glycoprotein (P-gp), a protein that pumps medications out of cells. Additionally, the extracts increase artemisinin’s half-life and oral bioavailability, extending its duration in the bloodstream.

In addition, A. annua contains also a wide range of bioactive compounds, which include flavonoids, phenolic acids, monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, coumarins, and essential oils which are considered to have powerful antimalarial activities [70]. Preclinical and experimental evidence reported that these compounds contribute to a broad spectrum of pharmacological effects such as antimicrobial, antiviral, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antihypertensive, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, and insect-repellent activities [70]. The mechanisms underlying these activities involve oxidative stress modulation, disruption of microbial and parasitic pathways, and effects on cellular signaling pathways (e.g., nuclear factor kappa B, cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase enzymes, and the Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway, NF-κB, COX/LOX, JAK-STAT).

A randomized controlled clinical trial by involving 159 patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was conducted, dividing participants into two groups: 80 in the control group and 79 in the A. annua extract (EAA) group. Over 48 weeks, the control group received standard treatment with methotrexate and leflunomide, while the EAA group received the same drugs supplemented with 30 g/day of EAA. Significant improvements in pain scores, number of tender joints, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were observed in the EAA group as early as 12 weeks. By 24 and 48 weeks, the EAA group demonstrated statistically significantly greater overall treatment efficacy compared to controls. Additionally, corticosteroid discontinuation rates were higher, and adverse events were reduced within 12 weeks in the EAA group. These findings indicate that combining EAA with methotrexate and leflunomide enhances therapeutic outcomes in active RA patients [71].

Artemisinin derivatives from A. annua also help regulate immune balance by modulating the ratio of T helper 17 (Th17) cells to regulatory T (Treg) cells, which plays a central role in autoimmune arthritis. These compounds interfere with the migration and invasiveness of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) by targeting signaling pathways such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/AKT/mTOR) and AKT/ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (AKT/RSK2), lowering inflammatory responses. Furthermore, antioxidant defenses are enhanced through activation of the p62/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (p62/Nrf2) pathway, reducing oxidative stress and protecting joint tissues [71,72].

5. Future Research Directions: Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Bioactive Compounds from A. annua in COVID-19 Recovery

The integration of (AI) into natural product research is rapidly transforming the search for new drugs, especially regarding bioactive compounds from A. annua and their potential roles in COVID-19 recovery. AI-driven approaches now enable researchers to analyze vast datasets, predict compound-target interactions, and accelerate the identification of promising therapeutic agents, which is particularly valuable in the urgent context of emerging infectious diseases like COVID-19 [73]. Recent research shows that AI techniques, such as virtual screening and machine learning models, are being actively applied to compounds from A. annua. For instance, various studies [74,75] have utilized AI-driven molecular docking to evaluate phytochemicals in A. annua, specifically artemisinin derivatives and flavonoids, for their binding affinities against the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. This approach significantly accelerates the prioritization of drug candidates for laboratory testing. Additionally, advancements in machine learning in 2024, integrated with metabolomics and chemometrics, have enhanced the extraction and quality control of bioactive compounds from A. annua. This optimization allows for more efficient isolation of antiviral compounds with consistent potency [76]. These AI tools facilitate better formulation and standardization for therapeutic applications.

5.1. Recent Advances Have Demonstrated That AI Can

- ▪

- Predict and rank bioactivity: Machine learning models can rapidly screen and rank the antiviral potential of A. annua compounds against SARS-CoV-2 molecular targets, such as the main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [77].

- ▪

- Accelerate virtual screening: In silico (computer-aided) methods, including molecular docking and dynamics simulations, are increasingly used to evaluate how A. annua-derived flavonoids and terpenoids interact with viral proteins, significantly reducing the time and resources needed for experimental validation [78].

- ▪

- Optimize extraction and formulation: AI tools help optimize extraction parameters for maximizing the yield and efficacy of bioactive compounds, ensuring that products are both potent and scalable for clinical use [73].

5.2. Recent Advances and Clinical Implications

- In Silico and in vitro studies: Multiple studies have used AI to identify lead compounds from A. annua with strong binding affinities to SARS-CoV-2 targets, supporting their further evaluation in laboratory and clinical settings [79].

- Clinical trials: Ongoing clinical trials are incorporating rapid AI-based assessment protocols to evaluate the efficacy of A. annua extracts and derivatives in COVID-19 patients, allowing for real-time data analysis and adaptive trial designs [80].

- Database integration: The establishment of large, AI-powered natural product databases is facilitating the sharing and analysis of global research findings, accelerating the translation of A. annua research into practical therapies [73].

5.3. Opportunities and Challenges Ahead

While AI has already begun to revolutionize the assessment and development of A. annua-based products for COVID-19 recovery, several challenges remain. These include the need for standardized data, improved interpretability of AI models, and the integration of multi-omics datasets to fully understand the mechanisms of action of complex herbal extracts. Nevertheless, the future is promising, with AI poised to further enhance the discovery, optimization, and clinical evaluation of bioactive compounds from A. annua and other medicinal plants [81].

6. Conclusions

A. annua and its bioactive compounds, particularly artemisinin and flavonoids, are promising therapeutic agents that support human health by combating oxidative stress-related complications such as inflammation and immune disorders. Additionally, artemisinin and its derivatives from A. annua are highly effective against microbial, malaria, and viral infections. AI-driven molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations have identified artemisinin and its derivatives as promising candidates for fighting SARS-CoV-2 due to their strong and stable binding interactions with key SARS-CoV-2 proteins, including the main protease (Mpro) and spike protein. These compounds exhibit mechanisms that involve scavenging reactive oxygen species and modulating the immune response, both of which contribute to inhibiting viral replication and reducing inflammation. The synergistic effects of multiple phytochemicals in Artemisia enhance their broad-spectrum antiviral potential. Although initial in vitro and preclinical studies are promising, clinical evidence remains limited, highlighting the need for rigorous trials to determine effective dosages and long-term safety. Advances in extraction and formulation technologies are making Artemisia-based therapies more accessible, safe, and affordable. Moving forward, it will be critical to integrate clinical validation with ongoing biochemical and pharmacological research to fully realize Artemisia’s potential as a complementary or alternative treatment for COVID-19 and related viral infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.M. and N.A.S.; software, A.A.M. and N.A.S.; validation A.A.M. and N.A.S.; investigation, A.A.M. and N.A.S.; resources, A.A.M. and N.A.S.; data curation, A.A.M. and N.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.M., N.A.S. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, A.A.M. and N.A.S.; visualization, A.A.M. and N.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported through the annual funding track by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work under grant number: 25UQU4361052GSSR01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through grant number: 25UQU4361052GSSR01.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Harvey, A.L.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Quinn, R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Noman, O.M.; Alqahtani, A.M.; Ibenmoussa, S.; Bourhia, M. A review on ethno-medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 2706–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jamal, H.; Idriss, S.; Roufayel, R.; Abi Khattar, Z.; Fajloun, Z.; Sabatier, J.M. Treating COVID-19 with medicinal plants: Is it even conceivable? A comprehensive review. Viruses 2024, 16, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boozari, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Natural products for COVID-19 prevention and treatment regarding to previous coronavirus infections and novel studies. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeri, N.C.; Shrestha, N.; Rahman, M.S.; Zaki, R.; Tan, Z.; Bibi, S.; Baghbanzadeh, M.; Aghamohammadi, N.; Zhang, W.; Haque, U. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: What lessons have we learned? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titanji, V.P. Biology and molecular basis of the pathogenesis and control of Corona viruses with a focus of the COVID-19: Mini Review. J. Camero. Acad. Sci. 2022, 18, 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Kanimozhi, G.; Pradhapsingh, B.; Singh Pawar, C.; Khan, H.A.; Alrokayan, S.H.; Prasad, N.R. SARS-CoV-2: Pathogenesis, molecular targets and experimental models. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 638334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirtipal, N.; Bharadwaj, S.; Kang, S.G. From SARS to SARS-CoV-2, insights on structure, pathogenicity and immunity aspects of pandemic human coronaviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 85, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V’kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus biology and replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Ali, S.I.; Kabiel, H.F.; Hegazy, A.K.; Kord, M.A.; EL-Baz, F.K. Assessment of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of Boswellia carteri resin. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 2015, 7, 502–509. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Ali, S.I.; Sameeh, M.Y.; El-Razik, T.M.A. Effect of solvents extraction on HPLC profile of phenolic compounds, antioxidant and anticoagulant properties of Origanum vulgare. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2016, 9, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhan, N.; Miladi, I.; Ali, S.I.; Poupon, E.; Mohamed, A.A.; Beniddir, M.A. Chemical constituents of Nitraria retusa grown in Egypt. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2017, 53, 994–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaafar, A.A.; Ali, S.I.; Kutkat, O.; Kandeil, A.M.; El-Hallouty, S.M. Bioactive Ingredients and Anti-influenza (H5N1), Anticancer, and Antioxidant Properties of Urtica urens L. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 13, 647–657. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.I.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Abdelsattar, M.; Bayomi, K.M. Salvia multicaulis X Salvia officinalis hybridization: Changes in the phenolic and essential oil profiles, gene expression and biological activity under Saint Catherine conditions—Egypt. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 173, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Sharma, B.; Kanwar, S.S. Antiviral phytochemicals: An overview. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 6, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalik, K.A.; El-Sheikh, M.; El-Aidarous, A. Floristic diversity and vegetation analysis of wadi Al-Noman, Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Turk. J. Bot. 2013, 37, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.K.; Al-Ghamdi, F.; Bawadekji, A. Floristic diversity and vegetation analysis of Wadi Arar: A typical desert Wadi of the Northern Border region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 21, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, Q.M.S. Antiviral potential of plants against COVID-19 during outbreaks—An update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şener, B. Antiviral activity of natural products and herbal extracts. Gazi Med. J. 2020, 31, 474–477. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-W.; Lee, Y.-Z.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Shih, C.; Chao, Y.-S.; Chang, H.-Y.; Lee, S.-J. Targeting coronaviral replication and cellular JAK2 mediated dominant NF-κB activation for comprehensive and ultimate inhibition of coronaviral activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, J.; Torrell, M.; Korobkov, A.A.; Vallès, J. Palynological features as a systematic marker in Artemisia L. and related genera (Asteraceae, Anthemideae)—II: Implications for subtribe Artemisiinae Delimitation. Plant Biol. 2003, 5, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orege, J.I.; Adeyemi, S.B.; Tiamiyu, B.B.; Akinyemi, T.O.; Ibrahim, Y.A.; Orege, O.B. Artemisia and Artemisia-based products for COVID-19 management: Current state and future perspective. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2023, 23, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesaeidi, S.; Miraj, S. A systematic review of anti-malarial properties, immunosuppressive properties, anti-inflammatory properties, and anti-cancer properties of Artemisia annua. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 3150–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetat, A.; Al-Ghamdi, F.A.; Osman, A.K. The genus Artemisia L. in the northern region of Saudi Arabia: Essential oil variability and antibacterial activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Cao, S.; Qiu, F.; Zhang, B. Traditional application and modern pharmacological research of Artemisia annua L. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 216, 107650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekiert, H.; Świątkowska, J.; Klin, P.; Rzepiela, A.; Szopa, A. Artemisia annua—Importance in traditional medicine and current state of knowledge on the chemistry, biological activity and possible applications. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinas, I.C.; Oprea, E.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Badea, I.A.; Buleandra, M.; Lazar, V. Chemical composition and antipathogenic activity of Artemisia annua essential oil from Romania. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.I.; Won, K.J.; Kim, D.Y.; Yoon, S.W.; Park, J.H.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.M. Anti-adipocyte differentiation activity and chemical composition of essential oil from Artemisia annua. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1934578X1601100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisibe, E.A.; Umoren, E.E.; Brisibe, F.; Magalhäes, P.M.; Ferreira, J.F.; Luthria, D.; Wu, X.; Prior, R.L. Nutritional characterisation and antioxidant capacity of different tissues of Artemisia annua L. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Yu, P.; Wang, M.; Qiu, F. Phytochemical analysis and geographic assessment of flavonoids, coumarins and sesquiterpenes in Artemisia annua L. based on HPLC-DAD quantification and LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS confirmation. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.F.; Luthria, D.L.; Sasaki, T.; Heyerick, A. Flavonoids from Artemisia annua L. as antioxidants and their potential synergism with artemisinin against malaria and cancer. Molecules 2010, 15, 3135–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonara, T.; Pascale, R.; Argentieri, M.P.; Papadia, P.; Fanizzi, F.P.; Villanova, L.; Avato, P. Phytochemical analysis of a herbal tea from Artemisia annua L. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2012, 62, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.S.; Lee, W.S.; Panchanathan, R.; Joo, Y.N.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, G.S.; Jung, J.M.; Ryu, C.H.; Shin, S.C.; Kim, H.J. Polyphenols from Artemisia annua L inhibit adhesion and EMT of highly metastatic breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231: Inhibitory effect of polyphenols on breast cancer invasion. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1180–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, S.; Jin, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Zheng, J.; Shi, D. Influence of Artemisia annua extract derivatives on proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 28, 773–778. [Google Scholar]

- Malaterre, A.; Lalarizo Rakoto, M.; Marodon, C.; Bedoui, Y.; Nakab, J.; Simon, E.; Hoarau, L.; Savriama, S.; Strasberg, D.; Guiraud, P. Artemisia annua, a traditional plant brought to light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaili, S.; Colas, C.; Fougère, L.; Destandau, E. Combination of molecular network and centrifugal partition chromatography fractionation for targeting and identifying Artemisia annua L. antioxidant compounds. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1615, 460785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulović, N.S.; Randjelović, P.J.; Stojanović, N.M.; Blagojević, P.D.; Stojanović-Radić, Z.Z.; Ilić, I.R.; Djordjević, V.B. Toxic essential oils. Part II: Chemical, toxicological, pharmacological and microbiological profiles of Artemisia annua L. volatiles. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 58, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nageeb, A.; Al-Tawashi, A.; Mohammad Emwas, A.-H.; Abdel-Halim Al-Talla, Z.; Al-Rifai, N. Comparison of Artemisia annua bioactivities between traditional medicine and chemical extracts. Curr. Bioact. Compd. 2013, 9, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Magalhães, P.M.; Dupont, I.; Hendrickx, A.; Joly, A.; Raas, T.; Dessy, S.; Sergent, T.; Schneider, Y.J. Anti-inflammatory effect and modulation of cytochrome P450 activities by Artemisia annua tea infusions in human intestinal Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-S.; Choi, W.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, D.C.; Sohn, U.D.; Shin, H.-S.; Kim, W. Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of artemisinin extracts from Artemisia annua L. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougouo, R.D.K.; Nguekeu, Y.M.M.; Dzoyem, J.P.; Awouafack, M.D.; Kouamouo, J.; Tane, P.; McGaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. Anti-inflammatory and acetylcholinesterase activity of extract, fractions and five compounds isolated from the leaves and twigs of Artemisia annua growing in Cameroon. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Weng, X.-G.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q.; Liu, X.-C. Flavonoids casticin and chrysosplenol D from Artemisia annua L. inhibit inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015, 286, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.S.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Mi, C.; Ma, J.; Piao, L.X.; Xu, G.H.; Li, X.; Jin, X. Artemisinin inhibits inflammatory response via regulating NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2017, 39, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, H. Immunosuppressive effect of ethanol extract of Artemisia annua on specific antibody and cellular responses of mice against ovalbumin. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2009, 31, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wojtkowiak-Giera, A.; Derda, M.; Kosik-Bogacka, D.; Kolasa-Wołosiuk, A.; Wandurska-Nowak, E.; Jagodziński, P.P.; Hadaś, E. The modulatory effect of Artemisia annua L. on toll-like receptor expression in Acanthamoeba infected mouse lungs. Exp. Parasitol. 2019, 199, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Wang, F.; Wang, H. Immunomodulation of artemisinin and its derivatives. Sci. Bull. 2016, 61, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, F.; Donato, R.; Pini, G.; Sacco, C.; Ascrizzi, R.; Bilia, A.R. Liquid and vapor-phase activity of Artemisia annua essential oil against pathogenic Malassezia spp. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogwang, P.E.; Ogwal, J.O.; Kasasa, S.; Olila, D.; Ejobi, F.; Kabasa, D.; Obua, C. Artemisia annua L. infusion consumed once a week reduces risk of multiple episodes of malaria: A randomised trial in a Ugandan community. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2012, 11, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxis, K.; Li, S.-M.; Heide, L. Pharmacokinetic study of artemisinin after oral intake of a traditional preparation of artemisinin Annua L. (Annua Wormwood). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 70, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddy, N.B.; Kalisya, L.M.; Bagire, P.G.; Watt, R.L.; Towler, M.J.; Weathers, P.J. Artemisia annua dried leaf tablets treated malaria resistant to ACT and iv artesunate. Phytomedicine 2017, 32, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamoddini, M.K.; Emami, S.A.; Ghannad, M.S.; Sani, E.A.; Sahebkar, A. Antiviral activities of aerial subsets of Artemisia species against Herpes Simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) in vitro. Asian Biomed. 2011, 5, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-F.; Tan, J.; Pu, Q. Study on the antiviral activities of condensed tannin of Artemisia annua L. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2004, 16, 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Lubbe, A.; Seibert, I.; Klimkait, T.; van der Kooy, F. Ethnopharmacology in overdrive: The remarkable anti-HIV activity of Artemisia annua. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 141, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.J.; Lee, M.; Jeon, S.B.; Park, H.; Jeong, S.; Lee, B.-H.; Choi, C. Antiviral activity of herbal extracts against the hepatitis A virus. Food Control 2017, 72, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T. Beyond malaria: The inhibition of viruses by artemisinin-type compounds. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Han, Y.; Yang, Z.M. Clinical observation on 103 patients of severe acute respiratory syndrome treated by integrative traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. Chin. J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med. 2003, 23, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, C.; Zhang, H.; Guo, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Hua, S.; Yu, J.; Xiao, P. Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antiviral Res. 2005, 67, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehailia, M.; Chemat, S. Antimalarial-agent artemisinin and derivatives portray more potent binding to Lys353 and Lys31-binding hotspots of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein than hydroxychloroquine: Potential repurposing of artenimol for COVID-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 6184–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Gilmore, K.; Ramirez, S.; Settels, E.; Gammeltoft, K.A.; Pham, L.V.; Fahnøe, U.; Feng, S.; Offersgaard, A.; Trimpert, J. In vitro efficacy of artemisinin-based treatments against SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.S.; Huang, Y.; Fidock, D.A.; Towler, M.J.; Weathers, P.J. Artemisia annua L. hot-water extracts show potent activity in vitro against COVID-19 variants including delta. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 284, 114797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Trimpert, J.; Moon, S.; Haag, R.; Gilmore, K.; Kaufer, B.B.; Seeberger, P.H. In vitro efficacy of Artemisia extracts against SARS-CoV-2. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, M.; Qin, H.; Lin, H.; An, X.; Shi, Z.; Song, L.; Yang, X.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y. Artemether, artesunate, arteannuin B, echinatin, licochalcone B and andrographolide effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses in vitro. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 680127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, T.M.; Oyewole, O.O.; Reid, S.P.; Ng, C.L. Repurposing quinoline and artemisinin antimalarials as therapeutics for SARS-CoV-2: Rationale and implications. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmanpour-Kalalagh, K.; Beyraghdar Kashkooli, A.; Babaei, A.; Rezaei, A.; Van Der Krol, A.R. Artemisinins in combating viral infections like SARS-CoV-2, inflammation and cancers and options to meet increased global demand. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 780257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzimoto, A.D. An overview of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties of Artemisia annua, its antiviral action, protein-associated mechanisms, and repurposing for COVID-19 treatment. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 19, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latarissa, I.R.; Khairinisa, M.A.; Iftinan, G.N.; Meiliana, A.; Sormin, I.P.; Barliana, M.I.; Lestari, K. Efficacy and safety of antimalarial as repurposing drug for COVID-19 following retraction of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. Clin. Pharmacol. Adv. Appl. 2025, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yuan, M.; Li, H.; Deng, C.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, W.; Xu, Q.; Zou, Y.; et al. Safety and efficacy of artemisinin-piperaquine for treatment of COVID-19: An open-label, non-randomised and controlled trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 57, 106216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Shan, X.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Zou, D.; Wang, M. The plant matrix of Artemisia annua L. for the treatment of malaria: Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic studies. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, V.S.; Padmavathi, Y.S. Artemisia annua: Illuminating the spectrum of pharmacological wonders. Food Drug Saf. 2025, 2, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliana, Y. The possible role of annual mugwort (Artemisia Annua) in arthritis. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Medical Sciences and Health, Antalya, Turkey, 16–19 November 2023; Volume 1, No. 1. pp. 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Swamikannu, B.; Umapathy, V.R.; Natarajan, P.M.; Nandini, M.S.; Stylin, A.G.Q.; Vimalarani, V.; Rajinikanth, S. Unlocking the therapeutic benefits of Artemisia Annua: A comprehensive overview of its medicinal properties. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, S4248–S4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.S.; Tsai, S.C.; Hsu, Y.M.; Bau, D.T.; Tsai, C.W.; Chang, W.S.; Tsai, F.J. Integrating natural product research laboratory with artificial intelligence: Advancements and breakthroughs in traditional medicine. BioMedicine 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitete Mulongo, E.; Matondo, A.; Ngbolua, K.T.N.; Mpiana Tshimankinda, P. Evaluation of antiviral potential of Artemisia Annua derived compounds against COVID-19 and Human Hepatitis B: An in silico molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation study. SSRN 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miandad, K.; Ullah, A.; Bashir, K.; Khan, S.; Abideen, S.A.; Shaker, B.; Alharbi, M.; Alshammari, A.; Ali, M.; Haleem, A.; et al. Virtual screening of Artemisia annua phytochemicals as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease enzyme. Molecules 2022, 27, 8103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, E.; Dilshad, E.; Ahmad, F.; Almajhdi, F.N.; Hussain, T.; Abdi, G.; Waheed, Y. Phytoconstituents of Artemisia Annua as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 main protease: An in silico study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, W.; Alimujiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, W. A multi-omics approach combining GC-MS, LC-MS, and FT-NIR with chemometrics and machine learning for metabolites systematic profiling and geographical origin tracing of Artemisia argyi Folium. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1757, 466138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwal, A.; Lavecchia, A. Artificial Intelligence in natural product drug discovery: Current applications and future perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 3948–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, R.K.; He, X.; Chopra, H.; Tsagkaris, C.; Shen, L.; Kamal, M.A.; Shen, B. Natural products for the prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic: Sustainable bioresources. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 758159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, F.U.; Roman, M.; Ahmad, K.; Rahman, S.U.; Shah, S.M.A.; Suleman, N.; Ullah, W. Artemisia annua: Trials are needed for COVID-19. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2423–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sowayan, N.S.; Al-Harbi, F.; Alrobaish, S.A. Artemisia: A comprehensive review of phytochemistry, medicinal properties, and biological activities. J. Biosci. Med. 2024, 12, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).