Abstract

Background: Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a common immunological disorder characterized by nasal symptoms and impaired quality of life. Despite advances in pharmacotherapy, symptom control often remains inadequate. Herbal medicine atomized inhalation (HMAI), a modern adaptation of traditional East Asian fumigation, may offer an effective adjunct or alternative therapy. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of HMAI, emphasizing its role as a localized drug delivery system. Methods: Six databases were searched through 28 April 2025, for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing HMAI for AR. Outcomes were pooled with random-effects meta-analysis; risk of bias and certainty of evidence were evaluated using Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 and GRADE. Results: Fourteen RCTs (n = 1606) met the inclusion criteria. HMAI significantly improved total effective rate compared with Western medicine (risk ratio = 1.20, 95% CI 1.09–1.32) and enhanced symptom relief when combined with Western or herbal treatments. However, the overall certainty of evidence ranged from moderate to very low due to methodological limitations across trials. Conclusions: HMAI may offer symptomatic benefits for patients with AR, particularly when used as an adjunct to existing therapies. Given the substantial variability and high risk of bias among included studies, these findings should be interpreted cautiously. Rigorous, placebo-controlled trials with standardized protocols are required to clarify the therapeutic role of HMAI in AR management.

1. Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is an immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated allergic inflammatory disease, characterized by rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, sneezing, and nasal itching [1]. Clinically, AR manifests as rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, sneezing, and nasal itching. This significantly impairs sleep quality and overall quality of life (QoL) [1,2,3]. AR affects an estimated 10–30% of adults and up to 40% of children worldwide [4]. Moreover, its prevalence has risen steadily in recent decades, along with a substantial socioeconomic burden [1,2,3]. Standard pharmacotherapies for AR, including oral H1-antihistamines, intranasal corticosteroids (INS), and leukotriene receptor antagonists, can provide symptomatic relief but often yield incomplete control and have notable adverse effects [5,6]. Antihistamines commonly induce sedation and xerostomia. Prolonged INS use can lead to nasal irritation or, rarely, systemic effects such as growth delay because of systemic absorption [7]. Allergen immunotherapy offers a disease-modifying approach but carries the risk of local or systemic allergic reactions and does not guarantee symptom resolution [8,9]. Moreover, conventional treatments generally do not address the underlying immune imbalances, and symptoms frequently recur after the cessation of therapy. This underscores the need for novel adjunct therapies that safely improve symptom control and target mucosal inflammation at its source [7].

Traditional East Asian medicine has long used herbal interventions for AR to correct presumed constitutional imbalances. Classical herbal formulations such as Xiao Qing Long Tang, Yu Ping Feng San, and Bu Zhong Yi Qi Tang have demonstrated effectiveness for AR in prior studies [10,11,12]. Fumigation therapy is an ancient treatment modality in which patients inhale warm vapors from heated or burned herbal preparations to alleviate respiratory and other ailments [13]. Historical records of herbal fumigation for nasal and airway conditions date back more than a millennium, and this practice is considered a precursor to modern intranasal herbal therapies [13,14]. Herbal fumigation can be viewed as a form of localized drug delivery that lays the foundation for modern herbal medicine atomized inhalation (HMAI). HMAI refers to the nebulization or vaporization of herbal decoctions such that patients can inhale the aerosolized extract directly through the nose [15]. By delivering therapeutic phytochemical compounds directly to the respiratory mucosa, HMAI concentrates the treatment effects at the disease site while minimizing systemic exposure. As a form of localized mucosal therapy, HMAI aligns with modern principles of targeted drug delivery for respiratory conditions. The intranasal inhalation route bypasses first-pass hepatic metabolism and reduces systemic drug distribution, thereby potentially lowering the risk of systemic side effects while achieving rapid and direct relief at the nasal mucosa [16]. Given the drawbacks of existing AR treatments, there is a growing clinical interest in whether this modernized inhalation therapy, derived from traditional fumigation, can enhance AR management outcomes. Early clinical reports, mostly from East Asia, suggest that HMAI, used either alone or as an add-on to conventional medicine, can improve nasal symptoms and modulate immune markers of AR, with few adverse events [17,18]. For example, certain herbal inhalation treatments have been associated with reductions in serum IgE and interleukin (IL)-5 levels along with symptom improvement, indicating potential immunomodulatory effects [17]. These preliminary findings are encouraging, but there remains an evidence gap regarding HMAI’s efficacy and safety according to rigorous international standards. To date, many studies on HMAI for AR have been small or lacked placebo controls. Furthermore, there is heterogeneity in the herbal formulations and outcome measures.

In light of this promising yet inconclusive evidence, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of HMAI in patients diagnosed with allergic rhinitis. To our knowledge, no prior review has specifically synthesized randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of herbal medicine HMAI as an inhaled, mucosa-targeted intervention for AR, nor comprehensively appraised the certainty of evidence—including immunological biomarkers and safety—using the risk of bias (RoB) 2 and The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). Our review was therefore designed to address this evidence gap. The experimental groups included regimens in which HMAI was used as monotherapy or in combination with other medicine, whereas the control groups included regimens with Western pharmacotherapy alone or in combination with other medicine for AR, excluding HMAI treatment. We focused on patient-important outcomes, primarily the total effective rate (TER, a composite measure of symptom improvement as defined in the trials), objective immunological indices (e.g., total IgE and inflammatory cytokines), and reported adverse events. By synthesizing the current evidence, we aimed to clarify the therapeutic value of HMAI, examine its potential immunomodulatory effects, and assess whether this intervention could be integrated into conventional AR management. This review also aimed to identify the limitations of existing research and guide future studies on standardized HMAI protocols for allergic rhinitis.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis conformed to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [19], with the completed PRISMA checklist provided in Supplementary File S1. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD42023476037).

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.1.1. Study Types

Only RCTs mentioning “randomization” were included. No restrictions were applied regarding the treatment duration or clinical settings. Non-RCTs in humans (e.g., case reports and review articles) and animal experimental studies were excluded.

2.1.2. Participants

Patients diagnosed with AR were included in the study. No restrictions were applied regarding disease stage, age, sex, race, country, hospitalization, or outpatient status.

2.1.3. Intervention Types and Controls

The treatment group included patients who received HMAI, defined as the inhalation of steam generated by the application of heat or ultrasonic energy to single or multiple herbal decoctions using a specialized device, as the primary intervention. The control group included patients who received the standard treatment for AR, excluding HMAI treatment.

2.1.4. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the TER. TER is expressed using the four categories “cured”, “markedly effective”, “effective”, and “ineffective”, and was dichotomized into effective and ineffective. Secondary outcomes included immune factors and adverse events.

2.2. Literature Searches

Six electronic databases (English, Korean, and Chinese), MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE (via Elsevier), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS), Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System (OASIS), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), were searched up to 28 April 2025. To increase search sensitivity in the literature search process, the following HMAI-related terms were used: “rhinitis,” “fumigation,” “aromatherapy,” “nebulizer,” “inhalation,” and “atomization.” No country or language restrictions were imposed. Additionally, when translating “fumigation therapy” into English, it was noted that “fumigation” may include the commonly understood concept of disinfection, and that “aromatherapy” may be confused with traditional aromatherapy, whereas “nebulizer” could limit the method of fumigation therapy to the use of conventional nebulizers. Therefore, the term “herbal medicine atomization inhalation” was consistently used. The detailed search terms and strategies for each database are provided in Supplementary File S2.

2.3. Study Selection

Two authors (SSS and JEK) independently screened the relevant literature. The search results were compared to ensure that no studies were omitted. Disagreements were resolved consensually, or a third author (JL or KIK) was consulted to decide on the final inclusion. The selected literature was organized and managed using EndNote software (version 20.3; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), which facilitated deduplication and streamlined the reference organization. Titles and abstracts were first reviewed, to exclude studies irrelevant to the study design, intervention, or target population. The full texts of the resulting studies were assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. After reviewing titles, abstracts, and full texts, only studies that included HMAI treatments were selected.

2.4. Data Extraction

Two independent researchers (SSS and JEK) extracted the data, which were organized using Microsoft Excel (version 2019; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). The following information was extracted: author, title, publication year, language, study type, number of participants, age, intervention (method, medicine composition, dosage, and formulation), treatment duration, frequency, outcome measures, and results.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

RoB in the included RCTs was assessed using the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool [20]. This tool evaluates five bias domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process, (2) bias because of deviations from intended interventions, (3) bias because of missing outcome data, (4) bias in the measurement of the outcome, and (5) bias in the selection of reported results. Each domain was judged as having a “low RoB,” “some concerns,” or a “high risk of bias.” Based on domain-level judgments, an overall risk of bias judgment was derived for each study. Two independent reviewers (SSS and JEK) assessed RoB. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and a third reviewer (JL or KIK) was consulted when necessary.

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Synthesis

Data were synthesized using Review Manager software (RevMan version 5.4.1; Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). An analytical framework was developed to ascertain suitable studies for each synthesis. This involved tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing them with the planned groups for each synthesis. To reduce between-study heterogeneity, the analyses were grouped based on study design. Owing to the inherent heterogeneity of fumigation therapy, which is typical in Traditional East Asian Medicine treatments, and the design characteristics of the included studies, a random-effects model (REM) rather than a fixed-effects model (FEM) was primarily applied in the meta-analysis. Meta-analyses were performed within groups when two or more studies reported the same outcome measure and were visualized using forest plots.

Considering the clinical heterogeneity caused by variations in interventions across studies, effect sizes were calculated using the REM and classified as small (0.20–0.50), medium (0.50–0.80), or large (>0.80), based on Cohen’s d. Dichotomous data (effective rate) were presented as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity within the individual analyses was assessed using the I2 statistic. The statistical significance of effect sizes was determined using overall effect testing or a 95% CI. The statistical significance level set at 5%. Adverse effects were reported by frequency without statistical analysis.

2.6.2. Sensitivity, Subgroup, and Publication Bias Analyses

Sensitivity analysis was conducted when a sufficient number of studies (at least 10 per study design) were available. Studies with high RoB were excluded to assess whether low-quality studies influenced the overall results. Additionally, a subgroup analysis was conducted by excluding studies from specific countries to evaluate whether geographical variations influenced the results. Publication bias was assessed when a sufficient number of studies (at least 10 per study design) were available, qualitatively and visually using a funnel plot and quantitatively using Egger’s test. If the p-value of the Egger’s test was <0.10, publication bias was considered to be present.

2.6.3. Certainty of Evidence

GRADE method was used to assess the certainty of evidence. It was classified as “high,” “moderate,” “low,” or “very low” using the online version of GRADEpro GDT software (https://www.gradepro.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2025)). “High” certainty indicated strong confidence that the estimated effect closely resembled the actual effect, whereas “very low” certainty suggested substantial discrepancy between the estimated and actual effects.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

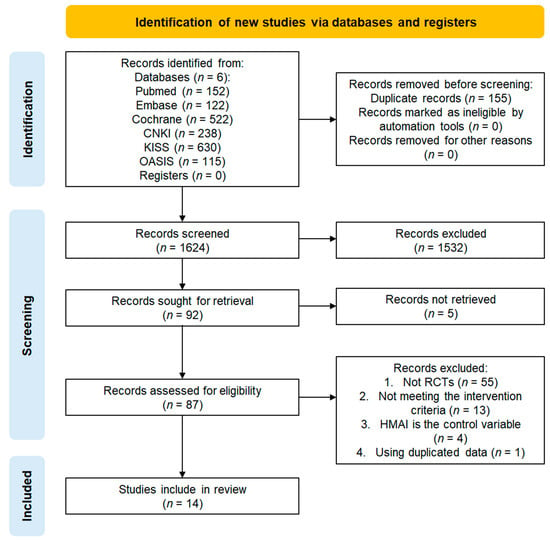

A total of 1779 studies were identified on MEDLINE (n = 152), EMBASE (n = 122), CENTRAL (n = 522), CNKI (n = 238), KISS (n = 630), and OASIS (n = 115). After deduplicating 155 studies, 532 studies that did not meet the selection criteria after title and abstract screening and five studies that could not be accessed for full-text review were excluded. Among the 87 studies selected for full-text evaluation, 73 were excluded for the following reasons: they were not RCTs (n = 55), did not meet the intervention criteria (n = 13), and inclusion of HMAI in the control group (n = 4), and duplicates (n = 1). Consequently, 14 studies were included in the final analysis, all of which were meta-analyzed. The study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) [21].

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

All included studies were conducted between 2001 and 2022 and were published in Chinese. Their detailed characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 1606 participants (patients diagnosed with AR) were enrolled, with 60–120 participants per study, and no dropouts reported. The participants’ ages, disease durations, and treatment periods ranged from 1 to 74 years, 1 month to 17 years, and 6 days to 2 months, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

The treatment and control groups were broadly categorized into four groups. The interventions in Groups 1 and 2 were designed as add-on therapies, whereas those in Group 3 included only the HMAI treatment. Five studies [22,23,24,25,26] compared a treatment group that received both Western medicine (WM) and HMAI, with a control group that received only WM (Group 1, WM + HMAI vs. WM). Three studies [27,28,29] compared a treatment group that received HM combined with HMAI to a control group that received only HM (Group 2, HM + HMAI vs. HM). Five studies [30,31,32,33,34] compared a treatment group that received HMAI with a control group that received WM (group 3, HMAI vs. WM). One study [35] compared a treatment group that received comprehensive HM, including HMAI, with a control group that received comprehensive WM (Group 4, comprehensive HM treatment vs. comprehensive WM treatment).

Fourteen studies evaluated the effectiveness of HMAI treatment. Five of these studies assessed clinical symptom scores, two evaluated immune indicators, two assessed Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) syndrome scores, and one evaluated QoL using the Rhinoconjunctivitis QoL Questionnaire (RQLQ). Additionally, one study examined the relationship between treatment effectiveness and TCM syndrome type, one assessed physical sign scores, one evaluated complications, and one assessed the recurrence rate (Table 2).

Table 2.

Herbal medicine composition and atomization inhalation methods.

The most frequently used herbs in the HMAI treatment group were Xanthium strumarium L. (Xanthii Fructus, 10 times) and Magnolia denudate Desr. (Magnoliae Flos; 10×), followed by Angelica dahurica (Hoffm.) Benth. & Hook.f. ex Franch. & Sav. (Angelicae Dahuricae Radix; 9 times), Mentha canadensis L. (Menthae Herba; six times), Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. (Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma; six times), and Astragalus mongholicus Bunge (Astragali Radix; five times). The volume of the liquid used in HMAI was 10–500 mL. The duration of HMAI treatment sessions was 10–30 min, either once or twice daily, or once every 2 days. The formulations, Latin names of the herbs, and methods of HMAI treatment used in each study are presented in Table 3, and the frequently used herbs are listed in Table 4.

Table 3.

Frequency of herbal medicines used in the included studies.

Table 4.

GRADE assessment for the meta-analysis of the included studies.

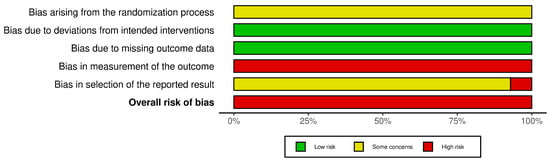

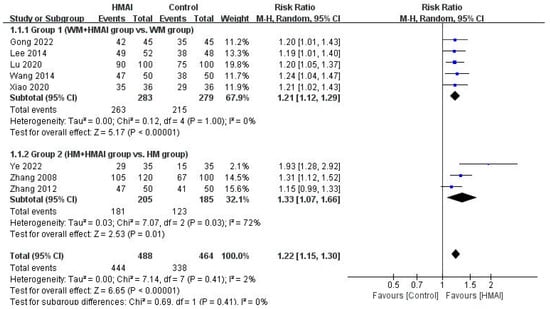

3.3. RoB of Included Studies

The Cochrane RoB 2.0 assessment revealed methodological concerns across all 14 included RCTs (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Most studies demonstrated concerns or high risks across multiple domains. For the randomization process, all studies reported random allocation and balanced baselines but failed to adequately describe the allocation concealment procedures. Deviations from intended interventions presented a low risk across all trials, as no protocol deviations or withdrawals were reported, despite the inability to blind participants owing to the inherent characteristics of the HMAI intervention. The missing outcome data showed a consistently low risk with complete reporting in all studies. However, measurement of outcomes represented the most significant limitation, with all trials receiving high risk ratings because of the impossibility of blinded outcome assessment. This was due to the inherent characteristics of HMAI, which make it difficult to establish credible placebo controls, and most reported outcomes were effectiveness rates evaluated based on patient symptom reports. For the selection of reported results, no studies provided publicly available protocols or pre-specified analysis plans. This resulted in some concerns for 13 studies and a high risk for one study [28] because of insufficient statistical methodology details. Overall, all 14 trials were classified as having a high risk of bias, primarily driven by unblinded outcome assessments, necessitating a cautious interpretation of the pooled efficacy estimates.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment results: Risk of bias summary.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias assessment results: Risk of bias graph [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

3.4. Effects of Interventions by Group and Outcome Measures

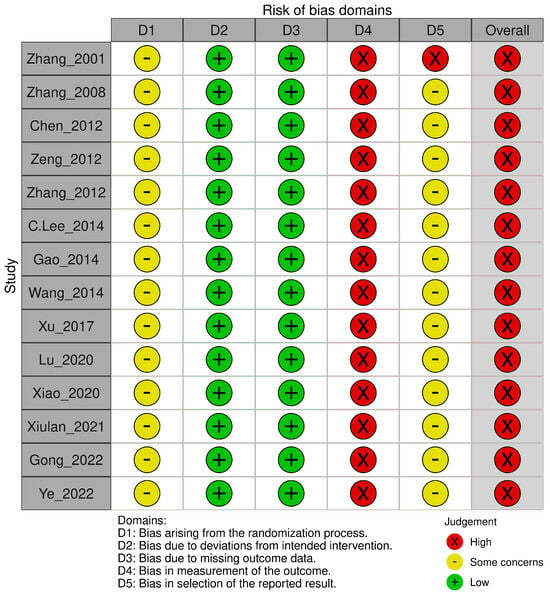

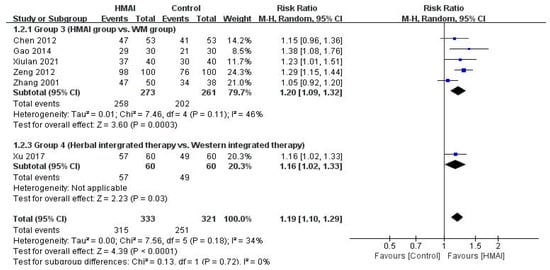

The effectiveness of the interventions in the four groups, compared by quantitatively synthesizing studies using similar intervention methods and outcome measurements, is presented in a forest plot (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Sensitivity, subgroup, and publication bias analyses were not performed because of the insufficient number of available studies.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the total effective rate of HMAI as add-on therapy [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of the total effective rate of HMAI versus [30,31,32,33,34,35].

3.4.1. Add-On Therapy Design

Group 1 (WM + HMAI vs. WM)

Regarding TER, the meta-analysis of the five studies in Group 1 revealed a significant improvement in the WM + HMAI group (RR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.12–1.29), with no observed heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 4). Other secondary outcome measures and immune indicators varied considerably in the interval and measurement tools used for the meta-analysis and were qualitatively described. One study [23] reported immune markers, revealing significantly lower IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels in the treatment group than in the control group (p < 0.05).

Group 2 (HM + HMAI vs. HM)

Regarding TER, the meta-analysis of three studies in Group 2 revealed a significant improvement in the HM + HMAI group (RR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.07–1.66), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 72%) (Figure 4). None of the studies in the HM + HMAI group assessed immune indicators or adverse events.

3.4.2. Monotherapy Design

Group 3 (HMAI vs. WM)

Regarding TER, the meta-analysis of the five studies in Group 3 revealed significant benefits in the HMAI group (RR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.09–1.32), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 46%) (Figure 5). Only one study [31] assessed immune indicators and reported significantly lower IL-4 and sIgE levels in the HMAI group than in the WM group (p < 0.05).

Group 4 (Herbal Integrated Therapy Group vs. Western Integrated Therapy Group)

The herbal integrated therapy group had significantly higher TER (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.02–1.33, n = 120) (Figure 5), significantly higher IL-12 and TNF-γ levels, and significantly lower IgE levels than the Western integrated therapy group (p < 0.05) [35].

3.5. Adverse Events and Safety

Only one study [24] in Group 1 reported adverse events such as general fatigue, localized infections, nausea, and allergic skin reactions. While 13 cases were reported in the control group, only 5 cases were reported in the treatment group, indicating significantly fewer adverse events in the treatment group compared with the control group (p < 0.05).

3.6. Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence across all groups was downgraded because of high RoB. The certainty of evidence was rated as “moderate” for TER in Group 1, “low” in Group 2, and “very low” in Group 3. Inconsistencies were noted in Groups 2 and 3, as the meta-analysis results suggested potential heterogeneity. In Group 3, the certainty of evidence in the treatment group was rated as “serious” for indirectness owing to variations in specific methods, such as consuming the HMAI solution after inhalation (Table 4).

4. Discussion

HMAI is a modern adaptation of traditional herbal fumigation therapy that is analogous to conventional inhalation treatments for respiratory conditions. This review provides the first comprehensive evaluation of HMAI for allergic rhinitis across multiple studies. We included patients diagnosed with allergic rhinitis, with intervention groups receiving regimens that incorporated HMAI and control groups receiving standard treatments for allergic rhinitis that did not include HMAI. The primary outcome TER, and to reduce clinical heterogeneity, we stratified the meta-analysis by study design, separating trials in which HMAI was used as an add-on therapy from those in which it was used as monotherapy.

In this study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to assess the efficacy and safety of HMAI in AR management. Fourteen RCTs [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], including 1606 patients, were identified from six domestic and international databases, regardless of publication language, and grouped into four categories based on study design. After excluding Group 4, which included only one study, a meta-analysis was conducted for Groups 1–3, with TER as the primary outcome. The results revealed the positive effects of HMAI treatment on improving AR symptoms: Group 1 (WM + HMAI vs. WM) (RR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.12–1.29, I2 = 0%, REM, N = 5, n = 562), Group 2 (HM + HMAI vs. HM) (RR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.07–1.66, I2 = 72%, REM, N = 3, n = 390), and Group 3 (HMAI vs. WM) (RR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.09–1.16, I2 = 46%, REM, N = 5, n = 534). However, the overall RoB was rated as high, and the certainty of evidence ranged from “moderate” to “very low.” Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Importantly, our findings should not be interpreted as evidence that HMAI is superior to established pharmacotherapy; rather, the main clinical focus of this review is whether HMAI provides incremental benefit when used as an adjunct to standard Western or oral herbal regimens.

The results of Groups 1 and 2, in which HMAI was an add-on to either WM or HM, revealed that combining HMAI with conventional Western or herbal treatments was more effective for AR than these treatments alone. This suggests that incorporating HMAI into conventional therapeutic strategies may further improve AR symptoms.

In Group 3, HMAI monotherapy was more effective than WM alone. However, cautious interpretation is needed owing to the small number of included studies (N = 5) and the “very low” certainty of evidence. Nonetheless, for pediatric patients who are more susceptible to the adverse effects of WM, HMAI therapy could serve as a viable option, either as a stand-alone or add-on treatment. Notably, two studies in Group 3 [25,26] focused exclusively on pediatric patients and reported that HMAI was more effective than conventional WM nebulizer treatments.

A study on the effectiveness of HM for AR found that HM was more effective than loratadine (RR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.16–1.22, I2 = 30%, FEM, N = 11, n = 956) [36]. This effect size was comparable to that found in Group 3 (HMAI vs. WM) in the present study. Additionally, in Group 2 (HM + HMAI vs. WM), the effect size was large, suggesting that the combined approach of HM and HMAI may be even more effective for AR than HM alone. Although other studies addressing AR have evaluated additional outcomes, such as the total nasal symptom score or RQLQ, a meta-analysis across these measures could not be conducted in the present study because of the heterogeneity of the outcome measures in the included studies. Consequently, direct comparisons of the effect sizes with those of other studies are limited. Therefore, future RCTs should be conducted using objective and standardized evaluation tools.

In the included studies, the most frequently used herbs in the HMAI treatment of AR were Xanthii Fructus and Magnoliae Flos, followed by Angelicae Dahuricae Radix, Menthae Herba, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma, and Astragali Radix. Several studies have investigated the effects of these herbs. Xanthii Fructus inhibits histamine release from peritoneal mast cells and suppresses systemic anaphylaxis, in addition to IgE-mediated passive cutaneous anaphylaxis (PCA) reactions [37]. Magnoliae Flos exhibits anti-inflammatory properties [38], suppresses auricular edema responses, and IgE-induced PCA reactions, and inhibits histamine release from peritoneal mast cells [39]. Angelicae Dahuricae Radix reduces the total number of inflammatory cells more effectively than montelukast, a leukotriene antagonist used for AR, and demonstrates anti-asthmatic effects by significantly suppressing IL-4 and IL-5 production in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [40]. Menthae Herba exerts antimicrobial effects by inhibiting the growth of Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella dysenteriae, and Escherichia coli [41]. Additionally, it relaxes acetylcholine-induced vascular contractions [42]. Astragaloside IV, extracted from Astragali Radix, reduces histamine-induced inflammatory responses in animal models by partially blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway, rendering it potentially effective against AR [43]. Taken together, these findings indicate that the core herbs most frequently used in HMAI formulations for AR may exert anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic effects by inhibiting mast-cell degranulation and histamine release, modulating Th2-skewed immune responses, and suppressing NF-κB–related inflammatory signalling pathways, which is mechanistically consistent with the improvements in TER observed in our meta-analysis and with the direction of immunological changes (e.g., IgE and cytokines) reported in a limited subset of included trials [37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

In clinical practice, the most commonly prescribed herbs for AR are Xanthii Fructus, Magnoliae Flos, Angelicae Dahuricae Radix, Menthae Herba, Astragali Radix, and Saposhnikoviae Radix [44]. This prescription pattern closely mirrors the findings of the present study (see Additional File 4), indicating strong concordance between real-world clinical practice and the present study’s dataset. Pharmacognostic reviews further indicate that most of these herbs enter the Lung meridian and either dispel wind pathogens or tonify Lung qi [45].

Specifically, Xanthii Fructus, Magnoliae Flos, and Angelicae Dahuricae Radix are pungent and warm exterior-releasing herbs that rapidly eliminate exogenous wind-cold and open nasal orifices. Moreover, these herbs are key components of traditional formulas such as Xinyi-San and Cang-er-Zi-San, recorded in the “Bang-yak Hap-pyeon”. While Menthae Herba disperses wind-heat and helps relieve sneezing and nasal congestion, Astragali Radix, a sweet-warm qi-tonifying herb, strengthens Lung and Spleen qi, reinforces the body’s defensive barrier, wei-qi, and modulates allergic responses [46]. Based on these pharmacological and traditional properties, pattern-based combinations of these herbs delivered via HMAI are expected to further enhance the therapeutic outcomes in AR management.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, all the included studies were conducted in China, presenting a geographical limitation. Second, the between-study heterogeneity due to the varied treatment types used in the control groups warrants cautious interpretation of the results. Additionally, none of the studies used a placebo control group, limiting their ability to provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of HMAI treatment alone. Third, although subgroup analyses based on study design reduced heterogeneity, the number of studies included in each meta-analysis was relatively small (3–5 studies per analysis). Fourth, only one study reported adverse events in which the intervention group received both HMAI treatment and acupoint herbal plaster therapy; hence, the safety of HMAI treatment alone could not be conclusively determined. In addition, safety and complications were not prospectively monitored or reported using standardized and validated definitions across trials, and most studies provided only brief statements (e.g., “no adverse events”) or no safety information at all; thus, the current evidence is insufficient to draw firm conclusions regarding the safety of HMAI (particularly for longer-term use). Fifth, the specific methods of HMAI treatment varied across the studies. In some cases, the herbal decoction was reheated to allow steam inhalation, whereas other methods involved ultrasonic nebulization. Sixth, the number of herbal medicines used per session and the duration, frequency, and time spent per treatment varied considerably across the studies. Seventh, the included trials encompassed patients across a broad age range. Children and adults differ in immune responses, nasal anatomy, and mucosal absorption characteristics, and their therapeutic responses may therefore also differ. In order to include all available RCTs, we did not impose age restrictions in the present review; however, this decision may have introduced additional clinical heterogeneity. Eighth, the lack of uniform outcome measures among the studies limited the comparison of effect sizes in the present study. TER is a composite outcome that is widely used in Chinese-language TCM clinical trials but is not globally standardized, and variability in how the categories (“cured”, “markedly effective”, “effective”) are operationalized across studies may introduce heterogeneity and limit the comparability and interpretability of our pooled estimates. Future clinical trials with consistent outcome measures, such as total nasal symptom score, RQLQ, and measures of adverse events for safety, are needed to robustly evaluate AR symptoms and QoL improvements with HMAI treatment. As HMAI is effective when added to conventional pharmacotherapy or other herbal treatments, further research on standardized HMAI protocols is essential to improve its practical application in AR treatment, in clinical settings.

Because HMAI delivers warmed vapor or aerosolized decoctions directly to the airway mucosa, inhalation-specific safety issues warrant explicit attention. In particular, steam-based delivery may pose a risk of thermal injury (scalds have been reported, especially in children), underscoring the need to control preparation temperature, inhalation distance, and supervision [47]. In addition, reusable nebulizer components can become microbially contaminated and may act as reservoirs delivering pathogens if cleaning and disinfection are inadequate; therefore, future HMAI trials should standardize device specifications and hygiene protocols and incorporate prospective monitoring of respiratory adverse events [48]. Given reported concerns regarding contaminants in herbal medicines (e.g., heavy metals) and potentially toxic constituents in certain botanical materials (e.g., aristolochic acids), chemical characterization, quality control, and inhalation-focused toxicological assessment should be incorporated to support a robust safety evaluation of aerosolized herbal preparations [49].

A notable strength of this study is that, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first systematic review to focus solely on the effects of HMAI treatment on AR. Moreover, it followed the PRISMA guidelines to provide more comprehensive and reliable conclusions on the effects of HMAI treatment for AR. Studies from both domestic and international databases, regardless of publication language or study design, were included to analyze as many studies as possible. This increased the external validity of the research and rendered the results more generalizable. These strengths also lead to discussions on future therapeutic applications. Furthermore, given the favorable efficacy and safety profiles of the herbal formulations used in the included HMAI interventions, these findings provide a valuable foundation for the future development of natural product-based nebulized therapies. Such formulations could serve as modernized inhalation agents for inflammatory airway diseases, such as allergic rhinitis and asthma, offering potential advantages in biocompatibility, localized delivery, and reduced systemic toxicity. This highlights the translational relevance of traditional fumigation therapies in modern pharmaceutical innovation.

5. Conclusions

HMAI demonstrated improvements in TER across several AR treatment comparisons in the included RCTs, suggesting potential symptomatic benefits, particularly when used as an adjunct to conventional therapy. However, because the overall risk of bias was high and the certainty of evidence ranged from moderate to very low, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The heterogeneity of interventions, limited reporting of safety outcomes, and lack of standardized evaluation tools further restrict the strength of the conclusions. Well-designed, placebo-controlled clinical trials using standardized HMAI protocols and validated outcome measures are needed to more definitively determine its efficacy and safety.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ph18121877/s1, File S1: PRISMA checklist; File S2: Search terms used in each database.

Author Contributions

S.-S.S. was responsible for the study methodology and data curation, and for writing the original draft and reviewing and editing the manuscript. J.-E.K. was responsible for study conceptualization and methodology, writing the original draft, and reviewing and editing the manuscript. J.P. and T.K. was responsible for the formal analysis and investigation. J.L. was responsible for the formal analysis, investigation, review, and editing of the manuscript. B.-J.L. was responsible for the study methodology and investigation. H.-J.J. was responsible for study investigation and funding acquisition. K.-I.K. was responsible for study conceptualization, supervision, methodology, review and editing of the manuscript, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant numbers RS-2020-KH087748 and RS-2025-02309209).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This study is based on a master’s dissertation originally written in Korean by Jung-Eun Kil, the co-first author of this study. The dissertation has been modified, supplemented, condensed, and reorganized for this study. All individuals mentioned in this Acknowledgments section have provided their consent to be acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AR | Allergic Rhinitis |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| FEM | Fixed-effect Model |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| HM | Herbal Medicine |

| HMAI | Herbal medicine atomization inhalation |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| IL | Interleukin |

| INSs | Intranasal corticosteroids |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REM | Random-effect Model |

| RoB | Cochrane Risk of Bias tool |

| RQLQ | Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| RR | Risk Ratio |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| TER | Total Effective Rate |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| WM | Western medicine |

References

- Bousquet, J.; Khaltaev, N.; Cruz, A.A.; Denburg, J.; Fokkens, W.J.; Togias, A.; Zuberbier, T.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Canonica, G.W.; van Weel, C.; et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy 2008, 63 (Suppl. S86), 8–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, K.H.; Ahn, H.R.; Park, J.K.; Kim, J.W.; Nam, G.H.; Hong, S.K.; Kim, M.J.; Ghoshal, A.G.; Muttalif, A.R.B.A.; Lin, H.C.; et al. Burden of respiratory disease in Korea: An observational study on allergic rhinitis, asthma, COPD, and rhinosinusitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2016, 8, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brożek, J.L.; Bousquet, J.; Agache, I.; Agarwal, A.; Bachert, C.; Bosnic-Anticevich, S.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; Canonica, G.W.; Casale, T.; Chavannes, N.H.; et al. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma (ARIA) Guidelines-2016 revision. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katelaris, C.H.; Lee, B.W.; Potter, P.C.; Maspero, J.F.; Cingi, C.; Lopatin, A.; Saffer, M.; Xu, G.; Walters, R.D. Prevalence and diversity of allergic rhinitis in regions of the world beyond Europe and North America. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, M.D.; Gurgel, R.K.; Lin, S.Y.; Schwartz, S.R.; Baroody, F.M.; Bonner, J.R.; Dawson, D.E.; Dykewicz, M.S.; Hackell, J.M.; Han, J.K.; et al. Clinical practice guideline: Allergic rhinitis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 152, S1–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S.W.Y.; Wong, A.Y.S.; Anand, S.; Wong, I.C.K.; Chan, E.W. Neuropsychiatric events associated with leukotriene-modifying agents: A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2018, 41, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licari, A.; Marseglia, G.; Ciprandi, G. New pharmacologic strategies for allergic rhinitis. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2016, 3, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridolo, E.; Incorvaia, C.; Pucciarini, F.; Makri, E.; Paoletti, G.; Canonica, G.W. Current treatment strategies for seasonal allergic rhinitis: Where are we heading? Clin. Mol. Allergy 2022, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.S. Allergy immunotherapy: State of the art. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2023, 10, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Woo, S.C.; Lyu, Y.R.; Yang, W.K.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kang, W.; Jung, I.C.; Kim, T.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Bojungikgi-Tang for persistent allergic rhinitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, Phase II trial. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Zhang, C.S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, A.L.; Guo, X.; Xue, C.C.; Lu, C. Potential effectiveness of Chinese herbal medicine Yu Ping Feng San for adult allergic rhinitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, Z.; Luo, Q.; Li, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Zhou, S. Efficacy and safety of the Chinese herbal medicine Xiao-Qing-Long-Tang for allergic rhinitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-H.; Park, H.K.; Lee, B.-W. A study on the fumigation therapy in Waitai Miyao and aromatherapy. J. Korean Med. Class. 2005, 18, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, H.R.; Oh, S.; Kim, S.-H.; Sung, W.-S.; Seung-Ug, H.; Kim, E.J. Comparison of the effects of topical nasal application on allergic rhinitis between Korean and western medicine: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Korean Med. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. Dermatol. 2019, 32, 62–89. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Liao, Y.; Zheng, Y. Chinese medicine in inhalation therapy: A review of clinical application and formulation development. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 3917–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, A.; Luo, H.; Ramakrishna, S. An overview on atomization and its drug delivery and biomedical applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, Q.; Qian, W.; Fan, Y. Meta-analysis of clinical trials on traditional Chinese herbal medicine for treatment of persistent allergic rhinitis. Allergy 2012, 67, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Yu, C.L. Antiinflammatory effects of Bu-zhong-yi-qi-tang in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 115, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R package and Shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Hu, D. The efficacy of modified Cang Er Zi San combined with Ma Huang tang fumigation in treating cold syndrome of allergic rhinitis. Inn. Mong. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2020, 39, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wang, H. Clinical study of Xinyisan decoction through nasal nebulization inhalation in the treatment of allergic rhinitis in children with underlying heat in lung meridian. Smart Healthc. 2022, 8, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, R.; Wu, R.; Long, Y.; Zhu, X. Clinical efficacy of acupoint application combined with steam nasal inhalation in the treatment of allergic rhinitis. Chin. J. Clin. Ration. Drug Use 2020, 13, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ci, J.; Wang, C.; Guan, H. Clinical Observation on the Efficacy of Traditional Chinese Medicine Nasal Irrigation Combined with Ultrasonic Atomization in the Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis. Zhejiang J. Integr. Trad. Chin. West Med. 2014, 24, 458–459. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. Observation on the efficacy of Cang’er powder nasal fumigation combined with western medicine in the treatment of 52 cases of allergic rhinitis. Shanxi Med. J. 2014, 43, 2542–2543. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.R.; Chen, W.-Y. Clinical study of oral use of modified Wenfei Zhiliu pills combined with Fructus Xanthii powder fumigation in the treatment of allergic rhinitis of Lung-qi deficiency-cold syndrome. J. Guangzhou Univ. Trad. Chin. Med. 2022, 39, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, J. Clinical observation of treatment of children with allergic rhinitis with Xinju atomization. Jilin Med. J. 2012, 33, 2759–2760. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. Clinical observation of 120 cases of allergic rhinitis treated with combined internal Chinese medicine and nasal steam inhalation therapy. J. Pract. Trad. Chin. Med. 2008, 24, 349–350. [Google Scholar]

- Xiulan, Y. Clinical observation on the treatment of allergic rhinitis with Mongolian medicine fumigation therapy. J. Med. Pharm. Chin. Minor. 2021, 27, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. Children’s allergic rhinitis treated with ultrasonic nebulization of Jiegen Yuanshen Decotion and Yupingfeng powder. Liaoning J. Trad. Chin. Med. 2014, 41, 2417–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Ye, S.; Han, Z. Children’s allergic rhinitis treated with ultrasonic nebulization of traditional Chinese medicine LXFMB. China Med. Pharm. 2012, 2, 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. 53 Cases of allergic rhinitis treated with Xiaoqinglong decoction combined with nasal fumigation. Henan Trad. Chin. Med. 2012, 32, 1433–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. Clinical observation on the efficacy of ultrasonic atomization inhalation of traditional Chinese medicine decoction in treating 50 cases of allergic rhinitis. Sichuan Trad. Chin. Med. 2001, 19, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, J.; Sun, D. Clinical observation of Xiangju capsules combined with ultrasonic nebulization of traditional Chinese medicine for treating allergic rhinitis of lung meridian wind-heat type in 60 cases. Zhejiang J. Trad. Chin. Med. 2017, 52, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Z. Efficacy of Chinese herbal medicine in treatment of allergic rhinitis in children: A meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 4006–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-H.; Jeong, H.-J.; Kim, H.-M. Inhibitory effects of Xanthii fructus extract on mast cell-mediated allergic reaction in murine model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 88, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Suzuki, J.; Yamada, T.; Yoshizaki, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Kadota, S.; Matsuda, S. Anti-inflammatory effect of neolignans newly isolated from the crude drug “Shin-i” (Flos Magnoliae). Planta Med. 1985, 51, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.M.; Yi, J.M.; Lim, K.S. Magnoliae Flos inhibits mast cell-dependent immediate-type allergic reactions. Pharmacol. Res. 1999, 39, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Seo, C.S.; Shin, H.K.; Lee, N.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H. A Composition Comprising the Angelica Dahurica Bentham et Hooker Extract There of Having Anti-Asthmatic Effect. Patent KR101165718B1, 18 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, H.; Osawa, K.; Yasuda, H.; Hamashima, H.; Arai, T.; Sasatsu, M. Inhibition by the essential oils of peppermint and spearmint of the growth of pathogenic bacteria. Microbios 2001, 106 (Suppl. S1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Runnie, I.; Salleh, M.N.; Mohamed, S.; Head, R.J.; Abeywardena, M.Y. Vasorelaxation induced by common edible tropical plant extracts in isolated rat aorta and mesenteric vascular bed. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 92, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Xie, L.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. New insights into mechanisms traditional Chinese medicine for allergic rhinitis by regulating inflammatory and oxidative stress pathways. J. Asthma Allergy 2024, 17, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.-T.; Kim, S.-G.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.N.; Park, H.-H.; Park, N.-Y.; Kim, K.-J.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, E. Anti-allergic effect of a Korean traditional medicine, Biyeom-Tang on mast cells and allergic rhinitis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.S. Ungok Herbology, 2nd ed.; Woosuk Press: Wanju County, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Medicine Standard Clinical Guidelines Development Project Group. Standard Clinical Practice Guidelines for Oriental Medicine Allergic Rhinitis; NICOM: Gyeongsan-si, Republic of Korea, 2021. Available online: https://nikom.or.kr/nckm/module/practiceGuide/view.do?guide_idx=202&menu_idx=14 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Baartmans, M.; Kerkhof, E.; Vloemans, J.; Dokter, J.; Nijman, S.; Tibboel, D.; Nieuwenhuis, M. Steam inhalation therapy: Severe scalds as an adverse side effect. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, e473–e477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, S.; Ind, P.W.; Thomas, C.; Goonesekera, S.; Haffenden, R.; Abdolrasouli, A.; Fiorentino, F.; Shiner, R.J. Microbial contamination of domiciliary nebulisers and clinical implications in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2014, 1, e000018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fitzgerald, M.; Huang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yang, C.; et al. Heavy Metal Contaminations in Herbal Medicines: Determination, Comprehensive Risk Assessments, and Solutions. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 595335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).