Abstract

Background/Objectives: The ongoing challenges posed by COVID-19 have highlighted the need for multi-target therapeutic strategies addressing both acute immune responses and systemic complications. Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino, a traditional herbal medicine rich in flavonoids and saponins, exhibits diverse pharmacological activities, including immunomodulatory and cardiovascular effects. In this study, we investigated the potential of G. pentaphyllum as a complementary treatment for COVID-19 using a network pharmacology approach combined with molecular docking analysis. Methods: To delve into the therapeutic mechanisms of G. pentaphyllum, we identified 59 active compounds and predicted 408 protein targets, of which 19 overlapped with COVID-19-associated genes, including IL1B, IL6, TNF, ACE, and REN. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were conducted to determine relevant biological processes and pathways, focusing on cytokine signaling, inflammatory responses, and the renin–angiotensin system. Network analyses evaluated interactions of flavonoids and triterpenoid saponins with immunological, inflammatory, renin–angiotensin system, and host entry pathways. Molecular docking was performed to validate the binding affinities of key compounds to their predicted targets. Results: The compound–target–pathway network revealed class-specific patterns: flavonoids primarily mapped to immuno-inflammatory nodes, whereas triterpenoid saponins were enriched for renin–angiotensin system/host-entry–related targets. Docking energies spanned −6.1 to −11.9 kcal/mol, with six compound–target pairs ≤ −10.0 kcal/mol. Notably, NOS2–rutin (−11.9 kcal/mol), NOS2–gypenoside LI (−11.6 kcal/mol), and ACE–gypenoside LI (−11.3 kcal/mol) showed the strongest affinities. Conclusions: These findings provide evidence that G. pentaphyllum exerts therapeutic effects through the complementary actions of flavonoid and saponin components, each modulating distinct molecular pathways. This dual mechanistic potential underscores the value of G. pentaphyllum as a versatile therapeutic for COVID-19 therapy.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), continues to pose a major threat to global public health [1]. While vaccines and antiviral agents have mitigated the severity of acute infection in many regions, the emergence of viral variants and the growing incidence of post-acute sequelae—collectively referred to as long COVID—highlight the limitations of current therapeutic options [2,3]. Long COVID, characterized by persistent symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive impairment, and inflammation-related disorders, presents a new clinical challenge that requires novel and integrative treatment approaches [4]. In this context, traditional herbal medicine—long used in the management of respiratory and systemic inflammatory conditions—offers a valuable reservoir of bioactive compounds with potential antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties [5].

Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino, a widely used herb in East Asian traditional medicine, has been reported to exhibit a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, hepatoprotective, and immunomodulatory effects [6]. These therapeutic properties are primarily attributed to two major classes of bioactive compounds: flavonoids and saponins [7]. Among these, specific compounds such as quercetin, ombuin, kaempferol, and gypenoside XVII have been shown in previous studies to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines, regulate immune responses, and interfere with viral replication pathways—activities that are particularly relevant to the treatment of COVID-19 [8,9,10,11]. Based on these characteristics, G. pentaphyllum extracts may hold potential as a complementary therapeutic agent against COVID-19. However, to date, no studies have systematically examined the efficacy or underlying mechanisms of G. pentaphyllum in this context.

Network pharmacology has emerged as a powerful in silico strategy for investigating the multi-component, multi-target nature of herbal medicines [12]. By integrating bioinformatics tools, chemical-target prediction, disease gene annotation, pathway enrichment analysis, and protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks, network pharmacology enables researchers to comprehensively map the complex interactions between natural compounds and disease-related targets [13]. This approach has been increasingly adopted in natural product research to uncover molecular mechanisms, identify therapeutic targets, and guide rational drug development [14].

Despite extensive pharmacological investigations into G. pentaphyllum, prior network-pharmacology studies have predominantly addressed non-viral indications without directly interrogating coronavirus-related processes or the renin–angiotensin system (RAS). As summarized in previous G. pentaphyllum network-pharmacology reports, these works mapped G. pentaphyllum constituents to PI3K–Akt, NF-κB, MAPK, JAK–STAT, and cancer-associated modules across liver, metabolic, inflammatory, and oncologic settings but did not evaluate COVID-19-specific immune dysregulation. To our knowledge, no in silico systems study has systematically examined G. pentaphyllum against COVID-19 pathophysiology using an integrated network-pharmacology-docking workflow.

In this study, we aimed to explore the therapeutic potential of G. pentaphyllum extract as a candidate treatment for COVID-19. To support this, we investigated the putative molecular targets and pathways associated with its bioactive compounds using a network pharmacology approach. Furthermore, molecular docking analysis was employed to assess the binding affinities between representative G. pentaphyllum-derived compounds and key COVID-19-related target proteins, thereby providing mechanistic insights into its possible mode of action. Through this integrative approach, we aim to provide a scientific rationale for the potential development of G. pentaphyllum extract as a complementary therapeutic agent for COVID-19.

2. Results

2.1. Network Pharmacology Analysis

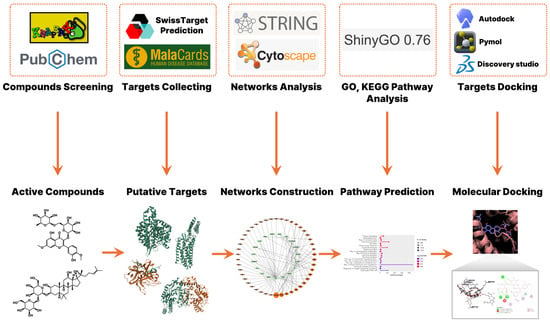

To investigate the potential therapeutic mechanisms of G. pentaphyllum in the treatment of COVID-19, we performed a network pharmacology analysis comprising compound screening, target prediction, disease-related gene identification, and network construction (Figure 1). A total of 59 active compounds were initially identified from G. pentaphyllum using the KNApSAcK and PubChem databases. Oral bioavailability and drug-likeness of these compounds were calculated using the SwissADME platform (Table S3). From these compounds, 408 putative protein targets were predicted. In parallel, 143 COVID-19-related targets were retrieved from the MalaCards database, which aggregates disease-related genes from multiple biomedical sources. A set of 19 overlapping targets between G. pentaphyllum-derived compounds and COVID-19-associated genes was identified, suggesting potential therapeutic relevance.

Figure 1.

Network pharmacology for identifying mechanisms of G. pentaphyllum in treating COVID-19.

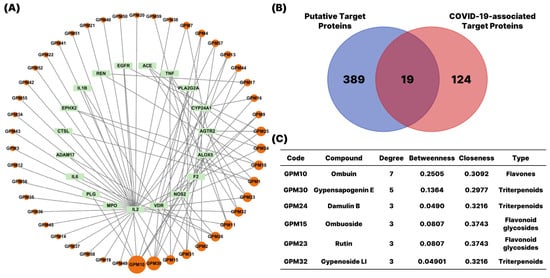

To visualize these interactions, we constructed a compound–target (CT) network using Cytoscape 3.10.1 (Figure 2). The network consisted of two types of nodes: orange circular nodes representing active compounds, and green rectangular nodes representing their corresponding protein targets. The size of each compound node reflected the number of targets associated with that compound. Notably, three flavonoids—ombuin, ombuoside, rutin—and three triterpenoids—damulin B, gypensapogenin E, gypenoside LI—demonstrated high degrees of connectivity in the compound–target network. These compounds interacted with multiple key target proteins, suggesting their central roles in mediating the pharmacological effects of G. pentaphyllum.

Figure 2.

Network pharmacology-based identification of candidate targets and active components of G. pentaphyllum against COVID-19. (A) Construction of Compound-Target network. Different active compounds (orange circular nodes) are displayed around the periphery, with node size reflecting the number of predicted targets. Putative target proteins (green rectangular nodes) are positioned inside the circle defined by the active compounds. (B) Venn diagram showed the overlap between the putative target proteins of G. pentaphyllum and COVID-19-associated targets. (C) Major active compounds of G. pentaphyllum related to COVID-19.

2.2. Protein–Protein Interaction

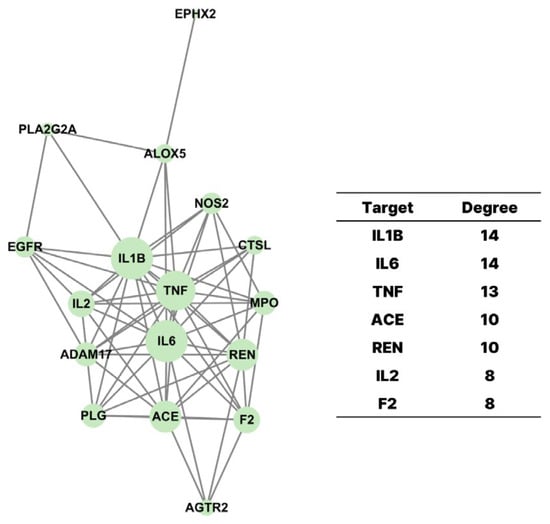

To further investigate the biological relevance of the 19 overlapping targets between G. pentaphyllum compounds and COVID-19-associated genes, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING database and visualized through Cytoscape 3.10.1 (Figure 3). The resulting network revealed several highly connected hub proteins, including IL1B, IL6, TNF, ACE, and REN, which are central regulators of inflammatory and cardiovascular pathways known to play key roles in COVID-19 pathogenesis. The size of each node represented its degree of connectivity, with IL6 and TNF exhibiting the highest degrees, highlighting their importance within the interaction network.

Figure 3.

The Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) network. The top 17 intersecting target proteins were shown in circular nodes with different sizes. The size of the nodes expressed the interaction degree on the network.

2.3. GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

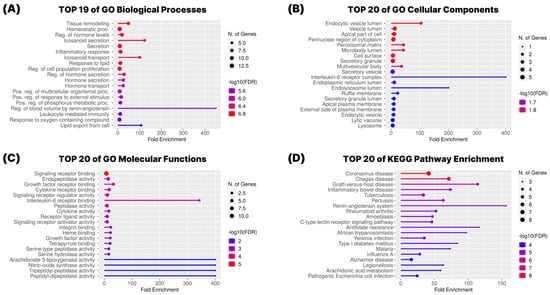

To elucidate the biological functions and signaling pathways associated with the 19 overlapping targets between G. pentaphyllum compounds and COVID-19-related genes, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses using the ShinyGO 0.77 platform (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis. (A) Biological process, (B) cellular components, and (C) molecular functions of Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. (D) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis.

The GO enrichment analysis was conducted across three functional categories: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). In the biological process category (Figure 4A), the targets were mainly associated with immune and inflammatory regulation, with significant enrichment in terms such as inflammatory response, regulation of cytokine production, response to lipopolysaccharide, and immune effector process. These findings indicate that G. pentaphyllum-related targets play crucial roles in modulating host defense mechanisms relevant to COVID-19. In the cellular component category (Figure 4B), enriched terms included external side of plasma membrane, membrane raft, and secretory granule membrane, suggesting that many of these targets are membrane-associated or secreted proteins, consistent with their involvement in cytokine signaling and immune cell interactions. Regarding molecular function (Figure 4C), the most prominent terms included cytokine activity, receptor binding, and enzyme binding, reinforcing the targets’ involvement in immune signaling pathways.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis further revealed that the 19 targets are significantly involved in pathways central to COVID-19 pathology (Figure 4D). These included the cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, TNF signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, NF-κB signaling pathway, and the renin–angiotensin system. These pathways are closely associated with hyperinflammation, cytokine storm, and cardiovascular complications frequently observed in severe COVID-19 cases. The enrichment of these pathways suggests that G. pentaphyllum may act through the modulation of both inflammatory signaling and the renin–angiotensin axis to exert potential therapeutic effects.

2.4. Compound–Target–Pathway (CTP) Network

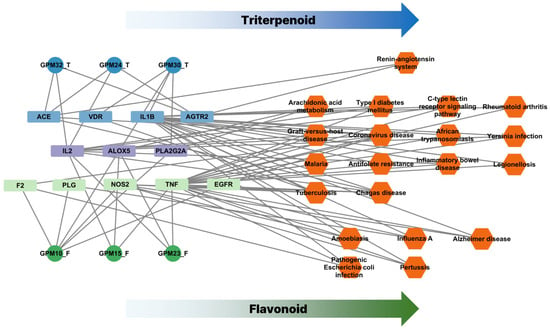

To further elucidate the mechanistic landscape of G. pentaphyllum, a compound–target–pathway (CTP) network was constructed, as illustrated in Figure 5. This network visually demonstrates the multi-level interactions among active compounds, their predicted protein targets, and the associated biological pathways. Notably, the bioactive compounds identified from G. pentaphyllum clustered into two major phytochemical classes: flavonoids and triterpenoids. These two classes showed distinct interaction profiles within the network, suggesting different modes of action. Flavonoid-type compounds (e.g., GPM10, GPM15, GPM23) were predominantly associated with inflammation-related targets such as TNF, NOS2, EGFR, and IL2, and enriched in signaling pathways related to immune modulation and infection control, including cytokine signaling, tuberculosis, and influenza pathways. In contrast, triterpenoid-type compounds (e.g., GPM24, GPM30, GPM32) interacted with a separate subset of targets including ACE, AGTR2, VDR, and were more involved in cardiovascular and renin–angiotensin system-related pathways, as well as metabolic and viral disease modules. This division of target specificity highlights a dual mechanism of action: flavonoids may primarily exert immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, while triterpenoids appear to contribute to cardiovascular regulation and viral entry interference. The presence of both compound classes in G. pentaphyllum underscores its potential as a broad-spectrum therapeutic candidate that targets COVID-19 pathophysiology through complementary mechanisms.

Figure 5.

The compound-target-pathway (CTP) network. The compound–target–pathway (CTP) network constructed for G. pentaphyllum. Circular nodes represent active compounds, rectangular nodes represent predicted protein targets, and hexagonal nodes represent KEGG pathways. Targets predominantly linked to triterpenoid compounds are shown in blue, flavonoid-related targets in green, and shared targets in purple.

2.5. Molecular Docking Analysis

To validate the interaction between bioactive compounds of G. pentaphyllum and key protein targets related to COVID-19, molecular docking simulations were performed against 12 representative host or viral proteins. Docking results for seven major compounds are summarized in Table 1. Docking simulations revealed binding energies ranging from −6.1 to −11.9 kcal/mol, supporting that the majority of key compounds and protein targets identified through network pharmacology exhibit substantial mutual binding potential relevant to COVID-19 pathophysiology. The docking protocol was validated, as the heavy-atom root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values between the redocked and crystallographic poses were ≤2.0 Å (or within a comparable range).

Table 1.

Docking affinities between major compounds and targets associated with active compounds of G. pentaphyllum and COVID-19. All docking simulations were performed in duplicate (n = 2), and RMSD values between runs were calculated.

Notably, flavonoid-type compounds such as rutin (GPM23), ombuin (GPM10), and ombuoside (GPM15) generally exhibited strong affinities toward immune-related targets including NOS2, PLG, and TNF, with docking scores often exceeding −9.0 kcal/mol. On the other hand, triterpenoid-type compounds such as gypensapogenin E (GPM30), damulin B (GPM24), and gypenoside LI (GPM32) preferentially targeted host cell entry and cardiovascular-related proteins such as ACE, AGTR2, and VDR, with several docking scores below −10.0 kcal/mol.

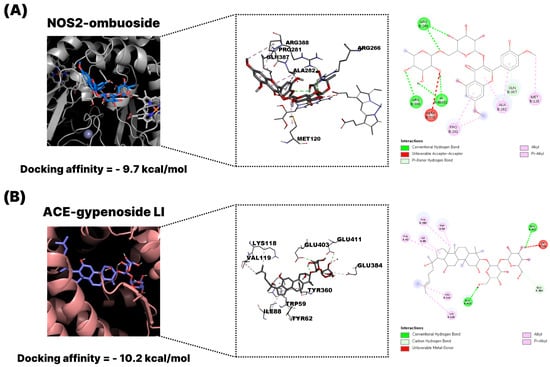

To visually represent the docking interactions, representative binding models of ombuoside (GPM15, flavonoid) and gypenoside LI (GPM32, triterpenoid) were selected and illustrated. As shown in Figure 6A, ombuoside demonstrated a strong binding affinity to NOS2 (−11.0 kcal/mol), a key enzyme in pro-inflammatory signaling. The docking pose revealed multiple conventional hydrogen bonds and π–π stacking interactions with residues such as GLY202, CYS200, TYR489, and TRP194. These interactions stabilize the ligand within the active site pocket, supporting its potential role in immunomodulation and inflammation suppression. Docking and inhibition studies on diverse iNOS ligands have repeatedly shown that Cys200, Gly202, Trp194 and Tyr489 make key contacts stabilizing inhibitors in the substrate access channel and are associated with reduced NO production [15,16,17]. Thus, the engagement of these residues by ombuoside supports a plausible mechanism in which tight binding in the heme-proximal pocket hinders L-arginine oxidation and thereby attenuates NO-mediated inflammatory responses. Figure 6B presents the docking of gypenoside LI with ACE (−11.3 kcal/mol), a central component of the renin–angiotensin system and viral entry mechanism. The triterpenoid scaffold of gypenoside LI formed extensive hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts with residues such as ARG124, PHE570, MET223, and PRO407, suggesting interference with ACE activity and possible inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein binding. Met223 and Phe570 belong to the S1/S2 subsites that line the substrate-binding channel around the catalytic HEXXH zinc-binding motif, whereas Arg124 and Pro407 are positioned along the neighboring substrate-access channel; residues in these regions are known to govern the binding and potency of ACE inhibitors [18,19,20,21]. In particular, Pro407 lies in the hinge region between the two subdomains, where ligand-induced interactions can modulate active-site geometry and catalytic efficiency [22], while Phe570 provides an aromatic platform that frequently participates in π–π/π–alkyl contacts with high-affinity inhibitors [19,21]. Therefore, the observed interactions of gypenoside LI with these functionally important residues support its potential to interfere with ACE activity and reduce downstream angiotensin II–mediated signaling.

Figure 6.

Representative molecular docking diagrams of G. pentaphyllum active compounds and key targets associated with COVID-19 using AutoDock Vina (version 1.1.2). (A) Docking model of ombuoside (GPM15, flavonoid) with NOS2. (B) Docking model of gypenoside LI (GPM32, triterpenoid) with ACE. The visualization includes the overall protein–ligand complex, binding site interactions (3D), and 2D interaction mapping.

2.6. Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) Analysis

To further validate the predictive accuracy of the molecular docking results, a three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) study was conducted using 24 triterpenoids with known ACE inhibitory activities. All molecules were successfully aligned using the O3A algorithm with coherent aglycone scaffold superposition (Figure S1A). The CoMFA model with three principal components (PC = 3) achieved r2 = 0.943 on the training set and q2 = 0.582 (SDEP = 0.463) under leave-one-out cross-validation (Figure S1B). Y-scrambling validation with 100 permutations yielded a q2 distribution centered at −0.389 (maximum = 0.299), with 0 out of 100 permutations exceeding the observed q2 value (p < 0.01), confirming the statistical robustness of the model (Figure S1C). Using this validated model, gypenoside LI was predicted to have pIC50 = 4.98 (IC50 ≈ 10.5 μM). The CoMFA stdev×coeff contour maps revealed key structural features associated with ACE inhibitory activity (Figure S1D). In the steric field, green contours (favorable bulk regions) were predominantly located near the aglycone lateral face and central ring junction, while yellow contours (unfavorable bulk regions) flanked the sugar termini. In the electrostatic field, blue contours (regions where positive potential is favorable) aligned with glycosidic oxygen atoms, whereas red contours (regions where negative potential is favorable) appeared in opposing positions, suggesting a polarized binding environment. When gypenoside LI was overlaid onto these contour maps, its aglycone core occupied green steric regions while its hydroxyl-rich sugar chains were positioned near red electrostatic regions, consistent with the predicted moderate-to-good potency.

2.7. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Analysis

To assess the structural stability of the docked protein-ligand complexes over physiologically relevant timescales, 50 ns molecular dynamics simulations were performed for ACE-gypenoside LI and NOS2-ombuoside complexes. For the ACE-gypenoside LI complex, the protein backbone RMSD stabilized at 0.16–0.22 nm after initial equilibration, while the ligand RMSD plateaued at 0.25–0.30 nm without large fluctuations, indicating a stable binding mode (Figure S2A). RMSF analysis revealed that most residues exhibited low positional fluctuations (<0.15 nm), with elevated fluctuations observed only in flexible loop regions and the C-terminus (Figure S2B). The radius of gyration remained constant at 2.38–2.40 nm throughout the trajectory, confirming that the overall protein structure was preserved (Figure S2C). Similarly, the NOS2-ombuoside complex displayed stable protein backbone dynamics, although the ligand RMSD stabilized at a higher value of 0.7–0.9 nm, suggesting greater conformational flexibility within the binding pocket (Figure S3). MM-GBSA binding free energy calculations yielded ΔG_bind = −32.56 ± 6.84 kcal/mol for the ACE-gypenoside LI complex and ΔG_bind = −26.57 ± 4.90 kcal/mol for the NOS2-ombuoside complex, both indicating thermodynamically favorable binding (Figures S2 and S3). The ACE complex exhibited approximately 6 kcal/mol stronger binding affinity compared to the NOS2 complex, primarily attributable to more favorable van der Waals interactions (−61.69 vs. −41.47 kcal/mol) and non-polar solvation contributions (−9.20 vs. −4.97 kcal/mol). Binding free energy values converged to stable means after the equilibration phase in both systems.

3. Discussion

This study identified G. pentaphyllum as a potential multi-target agent for the treatment of COVID-19. Among the active compounds in G. pentaphyllum, ombuin and quercetin were highlighted for their strong associations with key inflammatory and cardiovascular targets. Five core targets—IL1B, IL6, TNF, ACE, and REN—were identified as central to G. pentaphyllum’s potential therapeutic action. These targets are critically involved in immune dysregulation and the renin–angiotensin system, both of which are central to COVID-19 pathophysiology [23,24]. Enrichment analyses confirmed that G. pentaphyllum’s predicted targets are involved in cytokine signaling and inflammatory pathways. Additionally, molecular docking supported the potential of ombuin to interact strongly with all five targets. Collectively, these findings suggest that G. pentaphyllum may exert therapeutic effects in COVID-19 through coordinated modulation of immune and cardiovascular pathways. Previous network pharmacology studies on G. pentaphyllum have primarily focused on metabolic, inflammatory, and oncological diseases [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], and, to date, coronavirus-related signaling or RAS-associated pathways have not been analyzed. In particular, our analysis newly identified targets such as NOS2, F2, and REN, which are mechanistically relevant to COVID-19 pathogenesis (Table 2).

Table 2.

KEGG pathways of diseases associated with G. pentaphyllum analyzed through network pharmacology.

Among the 19 intersecting targets identified between G. pentaphyllum compounds and COVID-19-associated genes, several key nodes—IL1B, IL6, TNF, ACE, and REN—emerged as central in both the protein–protein interaction and compound–target networks. These targets are well-recognized mediators in COVID-19 pathophysiology [60]. IL1B, IL6, and TNF are pro-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to the cytokine storm observed in severe COVID-19 cases, leading to acute respiratory distress and systemic inflammation [23]. On the other hand, ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme) and REN (renin) are components of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which plays a dual role in both viral entry and vascular homeostasis [24,61]. SARS-CoV-2 is known to use ACE2 as a receptor, and dysregulation of the RAS has been linked to increased disease severity [62]. The convergence of these two mechanistic axes—cytokine regulation and RAS modulation—supports the rationale for developing G. pentaphyllum as a multi-target therapeutic candidate for COVID-19.

An important feature of G. pentaphyllum is its distinctive phytochemical profile, comprising both flavonoids and triterpenoid saponins—two classes of compounds that are rarely co-enriched in a single medicinal plant [10]. In this study, flavonoids and triterpenoid saponins emerged as the representative active compounds based on network topology and docking affinity. These two compound types exhibited clearly differentiated target profiles and functional pathways. Flavonoids were primarily associated with immunological targets (e.g., NOS2, TNF, IL2), suggesting roles in anti-inflammatory and cytokine-modulating activities [63]. In contrast, triterpenoids interacted more strongly with targets related to the renin–angiotensin system (e.g., ACE, AGTR2), implicating its potential in regulating vascular homeostasis and interfering with viral entry processes [64]. This dual engagement of immune and cardiovascular axes supports a multi-faceted pharmacological action, whereby G. pentaphyllum may simultaneously modulate systemic inflammation and protect vascular integrity—two hallmarks of COVID-19 severity [65]. The presence of both compound types within a single extract positions G. pentaphyllum as a unique candidate for broad-spectrum antiviral intervention. However, the therapeutic relevance of these compounds is contingent upon their actual concentrations in G. pentaphyllum preparations and their bioavailability in vivo. A summary of available quantitative data on major phytochemical components and published pharmacokinetic profiles is provided in Supplementary Information to support further dose-feasibility assessment [66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80] (Tables S1 and S2). Additionally, the co-occurrence of flavonoids and triterpenoids in G. pentaphyllum may provide synergistic therapeutic benefits, as recent studies have demonstrated that these phytochemical classes can produce enhanced anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects when combined [64,81].

While this study focused on the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the identified pharmacological actions of G. pentaphyllum may also have relevance for post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, often referred to as long COVID. Persistent inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and renin–angiotensin system imbalance are key features shared between acute COVID-19 and long-term complications [2]. Persistent endothelial dysfunction and elevated inflammatory markers (IL-6, TNF-α) have been documented in long COVID patients for at least 6 months post-infection [82,83]. Importantly, natural polyphenol-rich compounds have shown clinical efficacy in reducing these inflammatory biomarkers and improving vascular function in post-COVID patients [84,85,86]. The dual-targeting capacity of G. pentaphyllum, via flavonoid-mediated cytokine regulation and triterpenoid-mediated vascular and hormonal modulation, offers a potentially valuable therapeutic strategy for addressing both acute symptoms and longer-term pathological changes. Additionally, the multi-target nature of G. pentaphyllum could prove beneficial in the face of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants or related respiratory viral infections, where treatment approaches that act on host-based pathways rather than viral proteins may retain efficacy [87]. These findings support further preclinical validation and provide a rationale for considering G. pentaphyllum in broader antiviral and immunoregulatory contexts.

The reliability of our molecular docking predictions was further supported by complementary in silico validation approaches. 3D-QSAR analysis of 24 triterpenoid saponins demonstrated robust predictive performance (q2 = 0.58, r2 = 0.94), with gypenoside LI occupying sterically and electrostatically favorable regions around the ACE active site, consistent with strong inhibitory activity (Figure S1 and Table S4). Additionally, 100 ns MD simulations demonstrated stable protein-ligand interactions for both ACE–gypenoside LI and NOS2–ombuoside complexes, with minimal conformational drift (protein RMSD < 0.2 nm, ligand RMSD < 0.15 nm). MM-GBSA free energy calculations confirmed thermodynamically favorable binding throughout the trajectory, with ΔG_bind values of −32.6 ± 6.8 kcal/mol for ACE–gypenoside LI and −26.6 ± 4.9 kcal/mol for NOS2–ombuoside (Figures S2 and S3). These multi-layered computational validations strengthen confidence in the predicted interactions as plausible therapeutic targets worthy of experimental validation.

Despite the promising findings, this study has several limitations. First, all predictions were derived from in silico analyses, including network pharmacology and molecular docking, without experimental validation. Although these computational methods provide valuable insights into compound–target interactions and pathway associations, their predictions must be interpreted with caution until confirmed by in vitro and in vivo studies and supported by gene or protein expression analyses to verify coordinated modulation of immune and cardiovascular signaling. Second, the pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, and synergistic interactions of the active compounds within the complex G. pentaphyllum extract remain to be experimentally characterized, and the therapeutic feasibility in relation to effective dose ranges has not been evaluated. Moreover, variability in extraction solvents and plant parts across previous studies may influence phytochemical composition and affect translational relevance. Third, the study focused on molecular targets broadly associated with COVID-19 but did not distinguish between different clinical stages or viral variants, which may involve distinct pathological processes. Therefore, direct experimental evidence confirming the COVID-19-specific relevance of the identified targets is still needed. Future research should focus on experimental validation in relevant cellular and animal models, and assess the therapeutic efficacy of G. pentaphyllum in both acute and long-term manifestations of COVID-19 [88]. These efforts will be essential for translating computational predictions into clinically meaningful outcomes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Screening for Active Compounds, Putative Target Proteins and COVID-19 Associated Genes

In this study, the active compounds of G. pentaphyllum Makino and their putative target proteins were retrieved from the KNApSAcK and PubChem databases [89]. To identify the chemical constituents of the herb, the keyword “Gynostemma pentaphyllum” was used in the KNApSAcK search interface, which serves as a unique repository encompassing a wide range of medicinal plants and their bioactive components. Putative target proteins for each active compound were predicted using the SwissTargetPrediction web tool (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/, accessed on 2 February 2024) [90], which utilizes the SMILES notation of chemical structures to estimate target affinity. Predicted targets with a probability score of zero were excluded from further analysis. Genes associated with COVID-19 were obtained from the MalaCards database (https://www.malacards.org/, accessed on 22 March 2024), a comprehensive disease-centric resource modeled after the GeneCards platform [91]. The keywords employed for gene retrieval included: “COVID-19,” “Severe COVID-19,” “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome,” “Critical COVID-19,” “Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome,” and “Long COVID.”

4.2. Network Construction

The overlapping targets were identified by intersecting putative compound-related target proteins with COVID-19-associated genes. These common targets were considered potential therapeutic targets for COVID-19. The compound–target interaction network was visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.10.1) [92], and key bioactive compounds were identified based on network topology parameters, such as degree, betweenness, and closeness centrality. Additionally, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of the common targets was identified using the STRING web tool (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 29 March 2024) and filtered with an interaction score of less than 0.5 [92]. Targets were prioritized based on their degree values, which indicate their relative importance within the network.

4.3. Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis

To further elucidate the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and clarify the underlying mechanism of action of G. pentaphyllum, the intersecting genes were subjected to functional enrichment analysis using ShinyGO web tool (https://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go77/, accessed on 30 March 2024) [93]. This analysis included Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment, which encompasses biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions, as well as Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment.

4.4. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking studies were performed to evaluate the binding affinity and interaction patterns between the bioactive compounds of G. pentaphyllum and their key protein targets associated with COVID-19. SDF files of the compounds were obtained from the PubChem database and converted to PDB files using PyMOL, and subsequently to PDBQT files using AutoDockTools 1.5.7. The grid box size was defined as 60 × 60 × 60 Å for all targets with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å. The x, y, and z coordinates for each protein are summarized in Table S5. It was run at a ‘num_modes’ of 10 and an ‘energy_range’ of 4. Energy minimization was performed using ChemBio3D Ultra 12.0 with the MMFF94 force field until the root-mean-square (RMS) gradient reached a value of 0.01 kcal/mol·Å. The compounds without 3D structures were converted using Avogadro2 (version 1.102.1) [94]. The three-dimensional (3D) structure of the major proteins was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with the following PDB IDs: ACE (1O86), AGTR2 (5UNG), ALOX5 (3V99), EGFR (2ITX), F2 (1PPB), IL1β (8C3U), IL2 (1M48), NOS2 (2NSI), PLA2G2A (3U8I), PLG (1CEB), TNF (2AZ5), VDR (1DB1), Mpro (6LU7), RdRp (6M71), and Spike protein (6WPT). Selected proteins had water molecules removed, hydrogen atoms added, and Kollman charges assigned using AutoDockTools [95]. Molecular docking was performed using AutoDock Vina, and the results were visualized using Discovery Studio Client [95]. The docking protocol was validated by re-docking the co-crystallized ligands into their native binding sites, and comparing the resulting poses with the corresponding experimental structures using RMSD analysis calculated with Discovery Studio Client.

4.5. Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR)

Twenty-four triterpenoids with known ACE inhibitory activity were collected from literature sources [96], and their IC50 values were converted to pIC50 (−log10 IC50). Three-dimensional structures were generated, energy-minimized using the MMFF94 force field, and aligned to Protopanaxatriol using RDKit’s O3A algorithm. Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) was performed using Open3DQSAR v2.3 with a 2.0 Å grid (23 × 18 × 16 nodes) to calculate steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Gasteiger charges) fields. After field processing (cutoff ± 30, zero level 0.05, sdcut 2.0) and Block Unscaled Weighting, partial least squares (PLS) regression was performed with three principal components (PC = 3) determined by leave-one-out cross-validation (LOO-CV). Model robustness was validated by Y-scrambling (100 permutations). Standard-deviation × coefficient contour maps were visualized in PyMOL 3.1.6 with green/yellow (steric favorable/unfavorable) and blue/red (electrostatic positive/negative favorable) isosurfaces.

4.6. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using GROMACS 2025.3 with CUDA support. Two protein-ligand complexes (ACE-Gypenoside LI and NOS2-Ombuoside) were prepared with complete protein coordinates, cofactors (heme and tetrahydrobiopterin for NOS2), and explicit hydrogens. Systems were parameterized using a biomolecular force field, solvated in periodic cubic boxes with explicit water, and neutralized with counterions. After energy minimization (steepest descent with positional restraints) and equilibration (NVT pre-equilibration and restrained thermalization/pressure equilibration), production simulations were conducted for 50 ns using the Verlet cutoff scheme, PME for long-range electrostatics, LINCS constraints for hydrogen bonds, and a 2-fs time step. Binding free energies were estimated using MM-GBSA (gmx_MMPBSA, igb = 5, gbsa = 2) on 200 snapshots from the final 50 ns, calculating gas-phase van der Waals (ΔE_vdW) and electrostatic (ΔE_elec) interactions, as well as polar (ΔG_polar) and non-polar (ΔG_non-polar) solvation contributions.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the potential of G. pentaphyllum extract as a complementary therapeutic candidate for COVID-19 through an integrative in silico approach. Through network pharmacology and molecular docking, 59 curated compounds and 19 COVID-19–overlapping targets were identified. Furthermore, we found six flavonoids and triterpenoid saponins as key active compounds, each exhibiting distinct target profiles—flavonoids being primarily linked to immunological and inflammatory pathways (IL1B, IL6, TNF, NOS2), and triterpenoids to the renin–angiotensin system and host entry regulation (ACE, REN, AGTR2). These dual mechanistic pathways reflect the multi-target nature of the extract and its relevance to COVID-19 pathogenesis. To translate these findings, future studies should validate target engagement experimentally and assess whether representative flavonoid and saponin fractions show complementary or synergistic effects. Establishing exposure–activity relationships through quantitative profiling and pharmacokinetic evaluation will also be essential. Overall, the findings in this study provide a preliminary mechanistic basis that supports a hypothesis for further experimental validation of G. pentaphyllum as a multi-target herbal candidate with potential relevance to both acute and persistent manifestations of COVID-19 by modulating immuno-inflammatory signaling and RAS/host-entry–related proteins.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ph18121851/s1, Figure S1. Validation of 3D-QSAR CoMFA model and contour analysis for ACE inhibitors. Figure S2. Molecular dynamics simulation validation of ACE-Gypenoside LI complexes. Figure S3. Molecular dynamics simulation validation of NOS2-Ombuoside complexes. Table S1. Content of components determined in G. pentaphyllum from literature. Table S2. Pharmacokinetic parameters of G. pentaphyllum extracts and major components following oral administration in animal models. Table S3. The oral bioavailability (OB) and drug-likeness (DL) of major components from G. pentaphyllum extracts. Table S4. Statistical parameters and computational settings for 3D-QSAR and molecular dynamics validation. Table S5. The grid box centers of target proteins used in molecular docking simulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.Y., X.-L.P. and H.H.Y.; Methodology, M.H.K., J.A.W. and J.S.Y.; Validation, J.S.Y.; Formal Analysis, M.H.K., J.A.W., S.M.K. and D.K.L.; Investigation, M.H.K., J.A.W. and S.M.K.; Data Curation, M.H.K. and J.A.W.; Writing—Original Draft, M.H.K. and J.A.W.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.A.W., J.S.Y., X.-L.P. and H.H.Y.; Visualization, M.H.K. and J.A.W.; Supervision, X.-L.P. and H.H.Y.; Funding Acquisition, H.H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00217123).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major Findings, Mechanisms and Recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parotto, M.; Gyöngyösi, M.; Howe, K.; Myatra, S.N.; Ranzani, O.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Herridge, M.S. Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19: Understanding and Addressing the Burden of Multisystem Manifestations. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Choi, T.; Al-Aly, Z. Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in the Pre-Delta, Delta, and Omicron Eras. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Xie, Y.; Topol, E.J.; Al-Aly, Z. Three-Year Outcomes of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1564–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Xue, T.; Wang, B.; Guo, H.; Liu, Q. Application of Network Pharmacology in the Study of the Mechanism of Action of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Treatment of COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 926901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Saleem, M.A.; Saeed, F.; Afzaal, M.; Imran, A.; Nadeem, M.; Ambreen, S.; Imran, M.; Hussain, M.; Al Jbawi, E. Gynostemma pentaphyllum an Immortal Herb with Promising Therapeutic Potential: A Comprehensive Review on Its Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Perspective. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 808–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, M.; Gao, H.; Sun, X.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L. Chemical Composition of Tetraploid Gynostemma pentaphyllum Gypenosides and Their Suppression on Inflammatory Response by NF-κB/MAPKs/AP-1 Signaling Pathways. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, M.; Yu, S. Production of Gypenoside XVII from Ginsenoside Rb1 by Enzymatic Transformation and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecules 2023, 28, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi-Boroujeni, A.; Mahmoudian-Sani, M.-R. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Quercetin in COVID-19 Treatment. J. Inflamm. 2021, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lin, W.; Huang, J.; Xie, Y.; Ma, W. Anti-Cancer Effects of Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino (Jiaogulan). Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazdair, M.R.; Anaeigoudari, A.; Agbor, G.A. Anti-Viral and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Kaempferol and Quercetin and COVID-2019: A Scoping Review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2021, 11, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, L.; Yang, L.; He, C.; He, Y.; Chen, L.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, P. Network Pharmacology: A Bright Guiding Light on the Way to Explore the Personalized Precise Medication of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Chen, P.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, N.; Ma, Q.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, P. Network Pharmacology Integrated Molecular Docking Reveals the Potential of Hypericum Japonicum Thunb. Ex Murray against COVID-19. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2021, 35, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Tailang, M.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Khazaleh, N.; Thangavel, N.; Makeen, H.A.; Albratty, M.; Najmi, A.; Alhazmi, H.A.; Zoghebi, K.; et al. Integrating Network Pharmacology with Molecular Docking to Rationalize the Ethnomedicinal Use of Alchornea laxiflora (Benth.) Pax & K. Hoffm. for Efficient Treatment of Depression. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1290398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrari, F.; Ortiz-Flores, R.-M.; Lhamyani, S.; Garcia-Fuentes, E.; Jabri, M.-A.; Sebai, H.; Bermudez-Silva, F.-J. Protective Effects of Spirulina Against Lipid Micelles and Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Intestinal Epithelium Disruption in Caco-2 Cells: In Silico Molecular Docking Analysis of Phycocyanobilin. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.S.; Azam, F.; Eldarrat, H.A.; Alkskas, I.; Mayoof, J.A.; Dammona, J.M.; Ismail, H.; Ali, M.; Arif, M.; Haque, A. Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic and Molecular Docking Studies of Lanostanoic Acid 3-O-α-D-Glycopyranoside Isolated from Helichrysum stoechas. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 9196–9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Dai, V.V.; Meervelt, L.V.; Thao, D.T.; Thong, N.M. 4-(1-Methylamino)Ethylidene-1,5-Disubstituted Pyrrolidine-2,3-Diones: Synthesis, Anti-Inflammatory Effect and in Silico Approaches. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, C.; Acharya, K.R. ACE for All—A Molecular Perspective. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2014, 8, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadahunsi, O.S.; Olorunnisola, O.S.; Adegbola, P.I.; Subair, T.I.; Elegbeleye, O.E. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors from Medicinal Plants: A Molecular Docking and Dynamic Simulation Approach. Silico Pharmacol. 2022, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.-Y.; Kang, N.; Kim, E.-A.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.-H.; Ahn, G.; Oh, J.H.; Shin, A.Y.; Kim, D.; Heo, S.-J. Purification and Molecular Docking Study on the Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE)-Inhibitory Peptide Isolated from Hydrolysates of the Deep-Sea Mussel Gigantidas Vrijenhoeki. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebamiji, A.K.; Akintelu, S.A.; Akintayo, E.T.; Akintayo, C.O.; Aworinde, H.O.; Adekunle, O.D. Dataset on Substituents Effect on Biological Activities of Linear RGD-Containing Peptides as Potential Anti-Angiotensin Converting Enzyme. Data Brief 2023, 50, 109478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, J.L.; Jackson, R.M.; Jensen, H.A.; Hooper, N.M.; Turner, A.J. Identification of Critical Active-Site Residues in Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE2) by Site-Directed Mutagenesis. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 3512–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiß, C.; Willscher, E.; Paschold, L.; Gottschick, C.; Klee, B.; Henkes, S.-S.; Bosurgi, L.; Dutzmann, J.; Sedding, D.; Frese, T.; et al. The IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF Cytokine Triad Is Associated with Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Yang, X.; Yang, D.; Bao, J.; Li, R.; Xiao, Y.; Hou, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.; et al. Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, P.; Chen, W.; Bai, Y. Mechanisms of Gynostemma pentaphyllum against Non-Alcoholic Fibre Liver Disease Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 3760–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, G.; Luo, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Activity Components from Gynostemma pentaphyllum for Preventing Hepatic Fibrosis and of Its Molecular Targets by Network Pharmacology Approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Ping, D.; Sun, X.; Huang, K.; Peng, Y.; Liu, C. A Herbal Product Inhibits Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis by Suppressing the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 311, 116419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhao, X.; He, X.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, H.; Chen, S.; Zhou, G.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y. Gynostemma pentaphyllum Ameliorates CCl4-Induced Liver Injury via PDK1/Bcl-2 Pathway with Comprehensive Analysis of Network Pharmacology and Transcriptomics. Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, S.-L.; Liu, J.-K.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, P.-P. Mechanism of Gynostemma pentaphyllum in treatment of metabolism associated fatty liver disease based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2021, 46, 5080–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lai, H.; Wang, X. Integrating Transcriptomics, Network Analysis, and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing to Identify and Validate Key Target Genes of Gynostemma in the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 212, 107214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Cai, Z.; Song, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Feng, X. Gynostemma pentaphyllum Attenuates the Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice: A Biomedical Investigation Integrated with In Silico Assay. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2018, 2018, 8384631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Wei, Y.; Gao, S. Gypenosides Exert Cardioprotective Effects by Promoting Mitophagy and Activating PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/Mcl-1 Signaling. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Wu, J.; Lin, R.; Ran, L.; Shu, B.; Deng, H. Molecular Mechanisms of Gynostemma pentaphyllum in Prevention and Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. ECAM 2022, 2022, 9938936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.-S.; Xie, J.-B.; Xie, P.; Duan, Y.; Ling, Y.-Q.; Gu, Y.-L.; Piao, X.-L. Uncovering the Anti-NSCLC Effects and Mechanisms of Gypenosides by Metabolomics and Network Pharmacology Analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 281, 114506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, L.; Yao, L.; Zou, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, F. Gypenosides Inhibit Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis of Endothelial and Epithelial Cells in LPS-Induced ALI: A Study Based on Bioinformatic Analysis and in Vivo/Vitro Experiments. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.-S.; Xiao, M.-Y.; Xie, P.; Xie, J.-B.; Guo, M.; Li, F.-F.; Piao, X.-L. Comprehensive Serum Metabolomics and Network Analysis to Reveal the Mechanism of Gypenosides in Treating Lung Cancer and Enhancing the Pharmacological Effects of Cisplatin. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1070948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Jia, N.; Sun, Q. Network Pharmacology Analysis Reveals Neuroprotection of Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino in Alzheimer’ Disease. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Rao, H.; Sun, J.; Xiu, J.; Wu, N. Gypenosides Alleviate Oxidative Stress in the Hippocampus, Promote Mitophagy, and Mitigate Depressive-like Behaviors Induced by CUMS via SIRT1. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 337, 118823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Ji, Y.-L.; Du, H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wang, D.-P.; Lv, Q.-L. Bacoside a Inhibits the Growth of Glioma by Promoting Apoptosis and Autophagy in U251 and U87 Cells. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 2105–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-X.; He, X.-Y.; Yi, D.-Y.; Tan, X.-Y.; Wu, L.-J.; Li, N.; Feng, B.-B. Uncovering the Molecular Mechanism of Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino against Breast Cancer Using Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Medicine 2022, 101, e32165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, P.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J.; Wan, Z.; Cao, H.; Kong, L.; Jin, Y. Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulations Shed Light on the Mechanism behind Gynostemma pentaphyllum’s Efficacy against Osteosarcoma. Medicine 2024, 103, e39454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wu, Z.; Chang, X.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, J. Network Pharmacology Analysis and In Vitro Validation of the Active Ingredients and Potential Mechanisms of Gynostemma pentaphyllum Against Esophageal Cancer. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2025, 28, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Lin, T. Based on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Technology to Explore the Pharmacodynamic Components and Mechanism of Gynostemmae Pentaphylli Herba Reversing Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.; Duan, Y.; Xie, J.-B.; Piao, X.-L. Mechanism of Gypenosides of Gynostemma pentaphyllum Inducing Apoptosis of Renal Cell Carcinoma by PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 271, 113907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, X.; Xie, J.; Lv, C.; Lian, F.; Zhang, S.; Duan, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Piao, X. Gypenoside L and Gypenoside LI Inhibit Proliferation in Renal Cell Carcinoma via Regulation of the MAPK and Arachidonic Acid Metabolism Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 820639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liao, H.; Peng, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, W.; Dai, M.; Li, Z.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; Ying, Y.; et al. Comprehensive Network Pharmacology and Experimentation to Unveil the Therapeutic Efficacy and Mechanisms of Gypenoside LI in Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Lv, C.; Du, J.; Lian, F.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, Y. Gypenoside-Induced Apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Bladder Cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 9304552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Lan, B.; Li, S.; Jin, Y.; Cui, M.; Xia, Y.; Wei, S.; Huang, H. Gypenoside Inhibits Gastric Cancer Proliferation by Suppressing Glycolysis via the Hippo Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Lai, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y. Gypenoside Induces Apoptosis by Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway and Enhances T-Cell Antitumor Immunity by Inhibiting PD-L1 in Gastric Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1243353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Li, H.; Xu, W.; Liu, W.; Du, Y.; He, J.-F.; Ma, C. Research on the Potential Mechanism of Gypenosides on Treating Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy Based on Network Pharmacology. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2019, 25, 4923–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Alhasani, R.H.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, X.; He, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Strang, N.; Shu, X. Gypenosides Alleviate Cone Cell Death in a Zebrafish Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Xu, P.; Cheng, C.; Jiao, J.; Wu, Y.; Dong, S.; Xie, J.; Zhu, X. Integrating Network Pharmacology and Experimental Models to Investigate the Efficacy of QYHJ on Pancreatic Cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 297, 115516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, M.; Lu, M.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Jiang, W. Network Pharmacology Analysis, Molecular Docking Integrated Experimental Verification Reveal the Mechanism of Gynostemma pentaphyllum in the Treatment of Type II Diabetes by Regulating the IRS1/PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5561–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Gao, X.; Huang, D.; Xu, X.; Shen, J. The Potential of Gynostemma pentaphyllum in the Treatment of Hyperlipidemia and Its Interaction with the LOX1-PI3K-AKT-eNOS Pathway. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 8000–8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, A.; Ma, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Q. Protective Efficacy and Mechanism of Gypenosides against Diabetic Cataracts via the Ferroptosis Pathway: A Study Based on Network Pharmacology. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1007, 178175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.-B.; Xie, P.; Guo, M.; Li, F.-F.; Xiao, M.-Y.; Qi, Y.-S.; Pei, W.-J.; Luo, H.-T.; Gu, Y.-L.; Piao, X.-L. Protective Effect of Heat-Processed Gynostemma pentaphyllum on High Fat Diet-Induced Glucose Metabolic Disorders Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1215150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Guo, M.; Xie, J.-B.; Xiao, M.-Y.; Qi, Y.-S.; Duan, Y.; Li, F.-F.; Piao, X.-L. Effects of Heat-Processed Gynostemma pentaphyllum on High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice of Obesity and Functional Analysis on Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Strategy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 294, 115335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Ge, Y.; Yang, Y.; Su, J.; Chu, X. Exploring the Effects of the Anti-Diarrheal Formula on Intestinal Oxidative Stress Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Microbiomics. Fitoterapia 2025, 185, 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, X.; Tu, Z.; Fu, J.; Xu, D.; Zhou, Y. The Signal Pathways and Treatment of Cytokine Storm in COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheblawi, M.; Wang, K.; Viveiros, A.; Nguyen, Q.; Zhong, J.-C.; Turner, A.J.; Raizada, M.K.; Grant, M.B.; Oudit, G.Y. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2: SARS-CoV-2 Receptor and Regulator of the Renin-Angiotensin System. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1456–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzaabi, M.M.; Hamdy, R.; Ashmawy, N.S.; Hamoda, A.M.; Alkhayat, F.; Khademi, N.N.; Al Joud, S.M.A.; El-Keblawy, A.A.; Soliman, S.S.M. Flavonoids Are Promising Safe Therapy against COVID-19. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Nehul, S.; Singh, A.; Panda, P.K.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, G.K.; Tomar, S. Unraveling Antiviral Efficacy of Multifunctional Immunomodulatory Triterpenoids against SARS-COV-2 Targeting Main Protease and Papain-like Protease. IUBMB Life 2024, 76, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Koklesova, L.; Samuel, S.M.; Zhai, K.; Al-Ishaq, R.K.; Abotaleb, M.; Nosal, V.; Kajo, K.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; et al. Flavonoids against the SARS-CoV-2 Induced Inflammatory Storm. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-C.; Li, F.-F.; Pei, W.-J.; Yang, J.; Gu, Y.-L.; Piao, X.-L. The Content and Principle of the Rare Ginsenosides Produced from Gynostemma pentaphyllum after Heat Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jang, M.; Piao, X.-L. Determination by UPLC-MS of Four Dammarane-Type Saponins from Heat-Processed Gynostemma pentaphyllum. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Xie, J.-B.; Xiao, M.-Y.; Guo, M.; Qi, Y.-S.; Li, F.-F.; Piao, X.-L. Liver Lipidomics Analysis Reveals the Anti-Obesity and Lipid-Lowering Effects of Gypnosides from Heat-Processed Gynostemma pentaphyllum in High-Fat Diet Fed Mice. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-R.; Xing, S.-F.; Lin, M.; Gu, Y.-L.; Piao, X.-L. Determination of Flavonoids from Gynostemma pentaphyllum Using Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Triple Quadrupole Tandem Mass Spectrometry and an Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity in Vitro. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2018, 41, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.-G.; Baek, C.Y.; Hwang, Y.; Baek, E.; Park, C.; Song, H.S.; Lee, D. Investigating the Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic, and Chondroprotective Effects of Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino in Osteoarthritis: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Xiao, G.; Li, D.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, Z. Gynostemma pentaphyllum Promotes Skeletal Muscle Recovery via Its Inhibition of PXR-IL-6 Expression. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.H.; Huang, S.C.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Chen, B.H. Determination of Flavonoids and Saponins in Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino by Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 626, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.C.; Hung, C.F.; Wu, W.B.; Chen, B.H. Determination of Chlorophylls and Their Derivatives in Gynostemma pentaphyllum Makino by Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 48, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Pan, K.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, G.; Yin, Z.; Sun, J. Simultaneous Determination of 13 Representative Saponins from the Total Saponins of Gynostemma pentaphyllum in Rat Plasma Using LC-MS/MS for Pharmacokinetic Study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2025, 264, 116970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Guan, H.; Hu, L.; Pan, G. Simultaneous Determination of Gypenoside LVI, Gypenoside XLVI, 2α-OH-Protopanaxadiol and Their Two Metabolites in Rat Plasma by LC–MS/MS and Its Application to Pharmacokinetic Studies. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 1005, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Sui, C.; Ma, Y. Development of a Targeted Method for Quantification of Gypenoside XLIX in Rat Plasma, Using SPE and LC–MS/MS. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2017, 31, e3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liang, Q.; Luo, L.; He, Y.; Huang, X.; Wen, C. Determination of Gypenoside A and Gypenoside XLIX in Rat Plasma by UPLC-MS/MS and Applied to the Pharmacokinetics and Bioavailability. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 2022, 6734408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, A.; Yang, M.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, X. Pharmacokinetic Studies of Gypenoside XLVI in Rat Plasma Using UPLC-MS/MS Method. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 20, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Xue, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Sun, B.; Wang, P.; Tong, X.; Yu, X.; Li, H.; et al. Identification and Mechanism of Hepatoprotective Saponins and Endogenous Metabolites in the Sweet Variant of Gynostemma pentaphyllum. Bioorganic Chem. 2025, 165, 108996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Zang, H.; Xing, T.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Hu, X.; Yu, J.; Wen, J.; et al. Gypenoside XLIX Protects against Acute Kidney Injury by Suppressing IGFBP7/IGF1R-Mediated Programmed Cell Death and Inflammation. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejani, N.N.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; da Silva Maia Bezerra Filho, C.; de Sousa, D.P. Anticoronavirus and Immunomodulatory Phenolic Compounds: Opportunities and Pharmacotherapeutic Perspectives. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrońska, N.; Szlaur, M.; Zawadzka, K.; Lisowska, K. The Synergistic Effect of Triterpenoids and Flavonoids—New Approaches for Treating Bacterial Infections? Molecules 2022, 27, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xiang, M.; Jing, H.; Wang, C.; Novakovic, V.A.; Shi, J. Damage to Endothelial Barriers and Its Contribution to Long COVID. Angiogenesis 2024, 27, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljadah, M.; Khan, N.; Beyer, A.M.; Chen, Y.; Blanker, A.; Widlansky, M.E. Clinical Implications of COVID-19-Related Endothelial Dysfunction. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 101070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarelli, F.; Graziano, G.; Gambacorta, N.; Graps, E.A.; Leonetti, F.; Nicolotti, O.; Altomare, C.D. Small Molecules for the Treatment of Long-COVID-Related Vascular Damage and Abnormal Blood Clotting: A Patent-Based Appraisal. Viruses 2024, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Di Lauro, M.; Vita, C.; Montalto, G.; Giorgino, G.; Chiaramonte, C.; D’Agostini, C.; Bernardini, S.; Pieri, M. Potential Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Fatigue Effects of an Oral Food Supplement in Long COVID Patients. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, D.; Maparu, K. Long COVID Syndrome: Exploring Therapies for Managing and Overcoming Persistent Symptoms. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 4097–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Deeks, S.G. Mechanisms of Long COVID and the Path toward Therapeutics. Cell 2024, 187, 5500–5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oktavianawati, I.; Santoso, M.; Bakar, M.F.A.; Kim, Y.-U.; Fatmawati, S. Recent Progress on Drugs Discovery Study for Treatment of COVID-19: Repurposing Existing Drugs and Current Natural Bioactive Molecules. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2023, 66, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afendi, F.M.; Okada, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Hirai-Morita, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Ikeda, S.; Takahashi, H.; Altaf-Ul-Amin, M.; Darusman, L.K.; et al. KNApSAcK Family Databases: Integrated Metabolite–Plant Species Databases for Multifaceted Plant Research. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyerstedt, S.; Casaro, E.B.; Rangel, É.B. COVID-19: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Expression and Tissue Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espe, S. Malacards: The Human Disease Database. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-López, N.; Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Ambriz-Perez, D.L.; Heredia, J.B. Flavonoids as Cytokine Modulators: A Possible Therapy for Inflammation-Related Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.X.; Jung, D.; Yao, R. ShinyGO: A Graphical Gene-Set Enrichment Tool for Animals and Plants. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2628–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. J. Cheminformatics 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.I.; Yu, J.S.; Zhang, Y.; Yoo, H.H. Evaluating Flavonoids as Potential Aromatase Inhibitors for Breast Cancer Treatment: In Vitro Studies and in Silico Predictions. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 392, 110927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Zaib, S.; Jannat, S.; Khan, I. Inhibition of Angiotensin-I Converting Enzyme by Ginsenosides: Structure–Activity Relationships and Inhibitory Mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 6073–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).