Abstract

The name Green Chemistry was coined in 1996 to point out the development of chemical substances and sustainable processes that reduce the formation of toxic products for the environment and humans. The urgent need to bring down the negative effects of the chemical industry to safeguard human health has been the driving force behind green chemistry and the need to respect the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. This approach allows to increase the effectiveness of synthetic methods, to develop safer, less toxic, and environmentally sustainable chemicals. In this context, microwave-assisted organic reactions revolutionized the chemical synthesis; as a matter of fact, microwave chemistry led to a low environmental impact of the used solvents, and, over the years this overture has become the method of choice in synthetic chemistry. This review highlights in detail the main features of microwaves.

1. Fundamentals Principles of Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis

Microwave-assisted organic synthesis (MAOS) is the part of organic chemistry which applies microwave radiation to chemical reactions, where MAOS was firstly developed in 1986. In the last 30 years, microwaves represented a fundamental turning point in synthetic chemistry with the aim to increase the reaction rate and yields and reduce by-products formation. MAOS was first reported in 1986 in two independent studies. Gedye and co-workers in Canada, and Giguere, Majetich, and colleagues in the United States, demonstrated that organic reactions performed in domestic microwave ovens could be dramatically accelerated, often with higher yields and cleaner profiles compared to conventional heating methods [1,2].

These pioneering reports marked the birth of MAOS, although early adoption was limited due to safety concerns, poor reproducibility, and the lack of equipment specifically designed for chemical applications.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, further investigations highlighted both the promise and the limitations of the technique [3].

A major breakthrough came in the mid-1990s with the introduction of dedicated microwave reactors, which provided precise control over temperature, pressure, and power. This technological advancement enabled systematic studies of microwave effects and expanded the scope of transformations that could be reliably performed under microwave irradiation.

By the early 2000s, MAOS matured into a widely accepted methodology, with comprehensive reviews and mechanistic discussions consolidating its theoretical foundations and practical advantages [4].

Since then, the technique has been applied across diverse areas of chemistry, including heterocyclic synthesis, peptide chemistry, polymer science, materials chemistry and is now recognized as an important tool for green and sustainable synthesis due to its reduced reaction times, energy efficiency and lower solvent consumption [5].

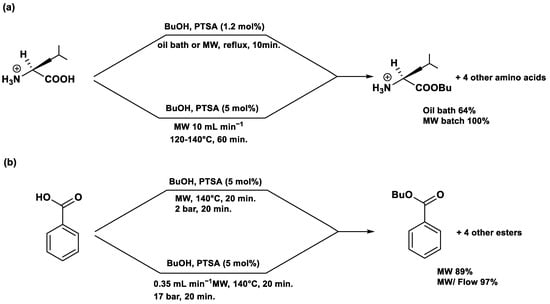

This methodology is included in the field of green chemistry because there is an urgent need to pay attention to the environment, in fact, solvents that are normally used are less polluting such as water, which is an excellent solvent to carry out microwave assisted reactions [6]. Microwave (MW) irradiation is widely recognized as a green and sustainable method in organic synthesis because it addresses multiple principles of green chemistry. MW heating delivers energy directly and volumetrically to reactants, dramatically reducing reaction times and lowering energy consumption. Reactions often proceed under milder conditions with improved yields and selectivity, minimizing by-products and chemical waste. MW-assisted processes are compatible with solvent-free or low-toxicity solvent systems, reducing the use of hazardous solvents and aligning with the use of safer reaction media. The rapid and uniform heating allows for precise temperature control, decreasing risks of decomposition or thermal runaway and promoting inherently safer chemistry. Additionally, MW synthesis can facilitate catalytic or multi-component reactions, further enhance atom efficiency and reduce reagent consumption. Its high efficiency and selectivity reduce the need for extensive purification steps, cutting down on energy and resource use. By integrating energy savings, waste reduction, safer reaction conditions, atom efficiency, and minimal solvent use, MW-assisted organic synthesis exemplifies a holistic application of green chemistry principles, offering a practical, environmentally friendly, and sustainable alternative to conventional thermal methods [7,8].

While it is correct to state that MAOS falls within the scope of green chemistry due to its reduced environmental footprint, this statement can be strengthened by illustrating concrete cases in which MAOS provides measurable ecological benefits compared to conventional heating methods. For instance, Kappe et al. demonstrated that microwave irradiation significantly reduces reaction times from hours to minutes in heterocyclic synthesis, thereby lowering overall energy consumption and minimizing waste generation [9].

Similarly, Varma et al. reported solvent-free or aqueous-based microwave protocols for a variety of organic transformations, highlighting a clear reduction in the use of toxic organic solvents and improved atom economy [10,11].

Another illustrative case is found in peptide chemistry, where microwave-assisted solid-phase synthesis affords higher yields and shorter cycle times with reduced solvent consumption compared to conventional methods [12].

These examples underscore how MAOS not only accelerates reactions but also concretely contributes to greener processes through lower energy demand, reduced solvent usage and enhanced efficiency, aligning with the principles of sustainable chemistry.

The term green chemistry has received widespread attention and describes the development of chemical products and processes that reduce the use of toxic and carcinogenic substances for human health [13,14]. Green chemistry, as delineated by Anastas and Warner, encompasses twelve principles aimed at reducing or eliminating the use and generation of hazardous substances in the design, manufacture, and application of chemical products. Recent literature underscores the continuous evolution of this field, highlighting innovations such as the development of green solvents, renewable feedstocks, and energy-efficient processes [15].

These advancements are pivotal in steering the chemical industry towards more sustainable practices. MAOS has emerged as a significant technique within green chemistry, offering several advantages over conventional heating methods. The application of microwave irradiation facilitates rapid and uniform heating of reaction mixtures, leading to enhanced reaction rates, higher yields, and improved selectivity. These benefits are particularly pertinent in the context of green chemistry, where efficiency and sustainability are paramount. From a green chemistry perspective, MAOS offers several environmental benefits. By facilitating solvent-free reactions or enabling the use of safer solvents like water or ionic liquids, MAOS reduces the reliance on hazardous and toxic solvents. Moreover, MAOS often enables solvent-free reactions, thereby reducing the environmental impact associated with solvent use and disposal. The technique also allows for precise control over reaction conditions, which can be crucial in minimizing by-products formation and reducing energy consumption. Recent advancements in MAOS further expanded its applicability and sustainability. For instance, the development of microwave-transparent reaction vessels has enabled the design of continuous-flow microwave reactors, allowing for scalable and reproducible synthesis under controlled conditions. Moreover, the integration of microwave irradiation with other green methodologies, such as biocatalysis and photocatalysis, has led to the development of hybrid systems that offer enhanced selectivity and efficiency [16].

By aligning with the principles of green chemistry, MAOS not only enhances the efficiency and selectivity of chemical reactions but also contributes to the overarching goal of reducing the environmental footprint of chemical processes.

Consequently, microwaves (MW) are considered as an important approach toward green chemistry because MW-assisted chemical syntheses are more eco-friendly with a low environmental impact.

MW-assisted chemical reactions are based on the dielectric heating of molecules, but, unfortunately, not all reactions can be carried out under microwave irradiation, and its successful application depends on the nature of the reactants, solvents, and reaction conditions. MAOS is particularly effective for reactions that involve polar solvents or reagents with high dielectric constants, which efficiently absorb microwave energy and convert it into heat; this allows for rapid and uniform heating, often resulting in shorter reaction times, higher yields, and improved selectivity [17].

Examples of reactions suitable for MAOS include the following: (i) cyclization reactions, e.g., the synthesis of quinolines via the Friedländer reaction can be completed in 5–10 min with yields above 85% under microwave conditions; (ii) heterocyclic syntheses, e.g., coumarins, pyrazolopyrimidines, and imidazole are efficiently prepared under microwave irradiation.

Examples of reactions less suitable for MAOS include the following: (i) reactions in non-polar solvents, e.g., reactions in hexane or toluene often proceed inefficiently because these solvents poorly absorb microwave energy; (ii) highly exothermic reactions or those with sensitive functional groups, e.g., pericyclic reactions or reactions involving diazonium salts can be unsafe under microwave heating.

Microwave heating is a form of dielectric heating that utilizes electromagnetic waves within the frequency range of 0.3 GHz to 300 GHz [18].

The primary mechanism of microwave heating involves the interaction between oscillating electric fields and polar molecules. Polar molecules possess a permanent dipole moment, allowing them to align with alternating electric fields. As the frequency of the applied electric field matches the relaxation time of the dipoles, efficient energy absorption occurs, leading to rapid molecular rotation and subsequent heat generation.

The frequency range of microwaves is particularly effective for inducing dielectric heating in polar substances. Within this spectrum, frequencies between 0.3 GHz and 300 GHz are used, with common industrial applications operating at specific frequencies such as 2.45 GHz, which balances penetration depth and heating efficiency.

Incorporating these theoretical insights into the discussion would provide a more robust understanding of the principles governing microwave-induced dielectric heating, thereby enriching the content for readers seeking a deeper comprehension of the subject.

The essential requirement is that the molecules that react are polar, therefore, either the reagents are polar, or the solvent is polar, or better, all reagents and solvents. Microwaves have wavelength λ ranging from 1 mm to 1 m, corresponding to the frequencies between 0.3 GHz and 300 GHz, so they are located between the infrared and the TV waves. Microwave energy in chemical reactors is primarily generated by a magnetron tube, a vacuum device that converts high-voltage electrical energy into coherent electromagnetic radiation at a nominal frequency of 2.45 GHz, which is commonly used for laboratory and industrial applications due to regulatory allocations and optimal penetration depth in polar solvents. The magnetron emits microwaves into a resonant cavity, which serves as a reaction chamber and acts to confine and distribute the electromagnetic field around the sample. The cavity design is critical: its geometry, dimensions, and reflective surfaces determine the formation of standing waves, which affect the uniformity of microwave energy absorption and heating within the reaction vessel [19,20].

Modern microwave reactors incorporate an autotuning cavity system, which continuously monitors the reflected power from the reaction vessel and dynamically adjusts impedance-matching elements, such as movable plungers, variable capacitors, or dielectric tuners to maximize energy transfer from the magnetron to the sample. This prevents excessive reflected power that can damage the magnetron and ensures that the microwave field is efficiently coupled into the reaction medium.

In addition to autotuning, precise frequency control of the magnetron output is essential. Small deviations in frequency can shift the positions of nodes and antinodes within the cavity, leading to non-uniform energy distribution, localized hot spots, and variable reaction rates. Some advanced systems integrate frequency stabilization circuits or even variable-frequency magnetrons to optimize energy absorption for different solvent systems or reaction scales [21,22].

Together, these design elements, magnetron-based microwave generation, resonant cavity geometry, autotuning impedance matching, and frequency stabilization enable uniform volumetric heating, improved reaction kinetics, enhanced reproducibility, and safe scale-up of microwave-assisted chemical processes. Such careful engineering is particularly important for sensitive reactions, heterogeneous mixtures, or scale-up applications where precise control of energy input directly affects reaction selectivity and yield.

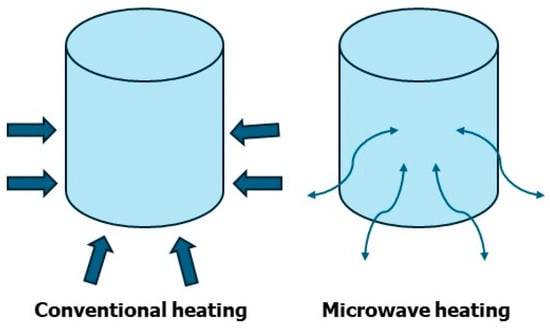

Normally, conventional synthesis, also known as batch synthesis, are carried out by heating the flask with a heating mantle; in this situation the heating starts from the outside of the reaction flask and reaches the center only in a sequential manner (Figure 1). This traditional heating is not homogenous, on the contrary, in the MAOS the heating is simultaneous in each part of the reaction mixture; this means that it occurs at the same time in all parts of the reaction mixture (Figure 1). MAOS offers distinct advantages over other alternative synthesis techniques, such as ultrasonication and mechanochemistry, primarily in terms of reaction efficiency and energy transfer. Unlike conventional heating, MAOS provides direct internal heating through the interaction of microwaves with polar molecules or ions, resulting in rapid and uniform temperature elevation that significantly accelerates reaction rates. In contrast, ultrasonication relies on acoustic cavitation, wherein the formation and collapse of microbubbles generate localized high temperatures and pressures, producing mechanical effects that enhance mass transfer and facilitate certain chemical transformations. While ultrasonication is particularly effective for heterogeneous reactions and nanoparticle synthesis, it generally requires longer reaction times and often produces less uniform heating compared to MAOS. Mechanochemistry, which employs mechanical forces such as grinding or milling to drive chemical reactions, offers solvent-free conditions and excellent environmental benefits, aligning closely with green chemistry principles. However, mechanochemical reactions are typically limited by scalability issues and require precise control of mechanical energy input. Overall, MAOS uniquely combines rapid, volumetric heating with compatibility for both homogeneous and heterogeneous systems, often resulting in higher yields, shorter reaction times, and broader substrate scope compared to ultrasonication and mechanochemistry. Nonetheless, the choice of method depends on the specific reaction type, substrate properties, and sustainability considerations, highlighting the complementary roles of these alternative synthetic strategies in modern organic chemistry.

Figure 1.

Microwave heating vs. conventional heating.

Microwave chemistry is based on electromagnetic waves at a low frequency of 2.45 GHz, and it was initially hypothesized that, taking into account a simple reaction: A + B = C, that the irradiation could influence the breaking of the chemical bonds of the reactants by promoting the formation of the product. However, this hypothesis has been later excluded; in fact, the microwaves emission frequency of 2.45 GHz is not sufficient to break the chemical bonds existing at the reagent level. Therefore, the heat transmission mechanism is completely different. As previously mentioned, the fundamental requirement for the molecules to be used in microwaves is that they must be polar, i.e., equipped with an electric dipole moment, so that as soon as the emission of the electromagnetic radiation arrives from the magnetron tubes inside the microwave reactor, the molecules immediately polarize into dipoles. In this situation, the dipoles try to align themselves with the oscillating electric field; when this happens, they produce friction, and during this time there is the emission of thermal energy, i.e., heat. This event can explain what generates homogeneous heating, also called indirect heating [19,21].

It is also important to evaluate the potential role of non-thermal effects, including the influence of electromagnetic fields on reaction kinetics and molecular orientation. While some early reports suggested that microwaves might enhance reaction rates beyond what could be explained by bulk heating alone, the majority of contemporary evidence indicates that thermal effects, rapid, localized heating, and selective energy absorption by polar solvents or reagents are the dominant contributors to rate acceleration. Experimental studies comparing microwave and conventional heating under isothermal conditions have consistently shown that, when the temperature is controlled accurately, reaction outcomes are largely equivalent, supporting the notion that the observed acceleration in MAOS is primarily a result of efficient dielectric heating. Nevertheless, subtle non-thermal contributions cannot be entirely excluded, particularly in reactions involving highly polar transition states, oriented dipoles, or solid-phase reactants in heterogeneous systems, where localized electric fields could influence molecular alignment or energy barriers. Techniques such as in situ temperature mapping, fiber-optic thermometry, and computational modeling have provided quantitative support for the predominance of thermal mechanisms, while highlighting that any non-thermal effects, if present, are typically secondary and context-dependent. This evidence underscores the importance of carefully distinguishing between true microwave-specific phenomena and conventional thermal effects when interpreting MAOS outcomes.

This chemical method shows advantages including:

- Higher reaction speeds compared to those in conventional heating, which occurs for example by heating the mixture in batch with the heating mantle and a bubble condenser. In MW conditions the heating speed is 4–8 °C per second [23]. For instance, the synthesis of bioactive heterocycles such as pyrroles, pyrazoles, and imidazoles has been significantly accelerated using microwave irradiation, reducing reaction times from several hours to just minutes while maintaining high yields [24].

- High reaction temperatures; in fact, the reactors work up to 300 °C. However, this is a limit temperature because if we set the reaction temperature at 300 °C we must consider many factors, like whether the reagents could degrade at those temperatures. Thus, generally, reaction temperatures are set until 150–160 °C, due to the instability of the reagents. Since microwave reactors work at high pressures (up to 30 bar), the increase in pressure inside the reactor allows to use much higher temperatures for each solvent, with respect to its normal boiling point (at 760 mmHg). However, the law that regulates the increase in temperature as a function of the increase of pressure is the Clausius–Clapeyron Equation (1) [23].

- High yields. The yields are always improved than in batch synthesis, due precisely to homogeneous heating; thereafter, reactions proceed with high reaction speeds, and obviously, if the yield is improved, the by-products are lower [23]. In peptide chemistry, MAOS methods facilitate rapid peptide bond formation under milder conditions, minimizing side reactions and the use of large volumes of solvents. For instance, a study demonstrated that MAOS peptide synthesis could achieve 68% crude purity of a complex peptide in under four hours, compared to traditional methods requiring 20 h [25].

- Minimization of the quantities of solvents. This problem is due to an economic point of view because the vials used in this apparatus are small, the sizes are 10, 35, and at most 100 mL, and so, the amount of solvent used is very small compared to traditional synthesis [23].

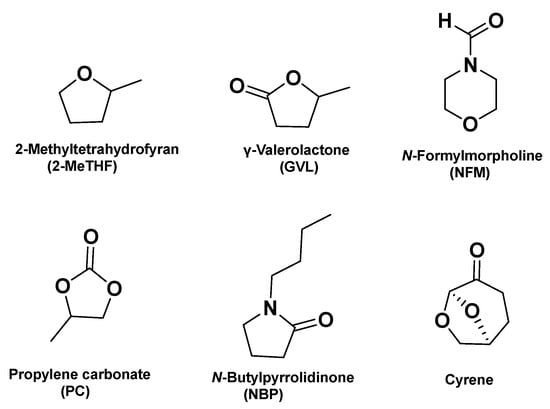

- Green solvents are used, solvents that have very low polluting potential, such as water, ethanol, methanol or ethylene glycol, which is why MW-assisted reactions move in the field of green chemistry. Common green solvents in MAOS include water, ethanol, glycerol, and polyethylene glycol (PEG). Water, being non-toxic and abundantly available, minimizes hazardous waste and reduces the reliance on volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Ethanol, derived from renewable biomass, offers low toxicity and biodegradability, making it an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional organic solvents. Glycerol and PEG are non-volatile, biodegradable, and reusable, contributing to lower environmental impact and enhanced process sustainability. Including such details would underscore the environmental benefits of these solvents, such as reduced toxicity, decreased flammability, and improved energy efficiency, thereby reinforcing the green chemistry principles applied in MAOS [23].

Other advantages of microwave-assisted reactions include the following:

- (1)

- Safer working conditions, because since the system is automated, if an over pressure occurs, the reaction is stopped and the system subjected to venting [23].

- (2)

- Reproducibility of the reactions carried out under microwave irradiation, for example, repeating a synthesis in which it seems that there is a variation in yield from one researcher to another. This problem is due to the operator variability, naturally, in the microwave reactor the processes are more reproducible, and the yields will certainly be much more comparable, because the automated procedures reduce human error and improve reproducibility by providing rapid, uniform heating, and precise control over reaction conditions. The incorporation of automated systems into MAOS further enhances these advantages by allowing for the precise programming of temperature profiles, irradiation power, and reaction times, which are critical parameters influencing reaction outcomes. Modern automated MAOS platforms, such as automated microwave reactors equipped with robotic sample handling and in-line analytical monitoring (e.g., IR, NMR, or mass spectrometry), enable high-throughput screening and parallel synthesis with minimal operator intervention. This not only standardizes reactions across multiple experiments but also facilitates the rapid optimization of reaction conditions, reducing trial and error approaches typical of manual synthesis. Moreover, automated data acquisition and process logging improve reproducibility and allow for better reaction tracking and troubleshooting. The synergy between microwave irradiation and automation thus provides a highly efficient, scalable, and reliable approach for both routine and exploratory organic synthesis, making MAOS a valuable tool in medicinal chemistry, heterocyclic synthesis, and materials science.

- (3)

- This technique allows to work on both small or large scales; accordingly, there are both classic reactors specifically for synthesis in academies and then there are reactors for scale-up, which are those used at an industrial level [23]. MAOS has demonstrated significant advantages in enhancing reaction rates, improving yields, and reducing energy consumption at the laboratory scale. However, translating these benefits to industrial-scale synthesis requires careful consideration of several factors. The scalability of MAOS is influenced by the uniformity of microwave energy distribution, the thermal conductivity of the reaction mixture, and the ability to maintain consistent reaction conditions over extended periods. To address these challenges, continuous-flow microwave reactors have been developed, offering improved heat and mass transfer characteristics compared to traditional batch systems. These reactors facilitate the efficient processing of larger volumes, enabling the application of MAOS in industrial settings. For instance, a study demonstrated the successful scale-up of a continuous-flow microwave reactor operating at high temperatures and pressures, achieving throughput rates suitable for industrial applications. Additionally, the integration of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) with microwave systems allows for real-time monitoring and control of reaction parameters, ensuring consistent product quality and facilitating regulatory compliance [26].

Despite these advancements, challenges remain in the uniformity of microwave energy distribution and the design of reactors capable of handling the specific requirements of industrial-scale operations. Continued research and development are essential to optimize reactor designs, enhance scalability, and fully realize the potential of MAOS in industrial synthesis.

Hence, the microwave vials, which are called vessels, have a size of 10 mL (which can be filled up to half, up to 5 mL to leave space to increase pressure within the system) or 35 mL. The vial septum is hermetic with the aim of preventing opening during the reaction. The internal part of the vial cap is covered with a silicone septum internally coated with Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), a synthetic fluoropolymer of tetrafluoroethylene [23]. Therefore, it is essential to highlight the specificity of microwave heating in organic synthesis, as its unique interaction with reactants supports the acceleration of chemical transformations. Microwave energy couples directly with polar molecules and ionic species through dipolar polarization and ionic conduction mechanisms, leading to rapid and homogeneous volumetric heating within the reaction medium. Unlike conventional thermal methods, which rely on slow conductive or convective heat transfer, microwaves induce molecular rotation and ion oscillation, thereby generating heat internally and selectively in regions with higher dielectric loss. This localized and efficient energy transfer not only shortens reaction times but can also promote reaction pathways that are less accessible under traditional heating conditions. Moreover, the enhanced kinetics often observed in microwave-assisted processes arise from the combination of precise temperature control, minimization of thermal gradients, and, in some cases, specific non-thermal microwave effects that remain a subject of scientific debate. Collectively, these mechanisms contribute to improved yields, cleaner reaction profiles, and the development of more sustainable synthetic protocols.

Despite the numerous advantages of MAOS, the technique is not without limitations and challenges that warrant critical consideration. One primary constraint is the scalability of MAOS, as uniform heating becomes increasingly difficult in larger reaction volumes, potentially leading to inconsistent yields or selectivity. Additionally, the high initial cost of specialized microwave reactors and the need for microwave-transparent or pressure-resistant vessels may limit accessibility for some laboratories. Certain reactions, particularly those involving non-polar or poorly microwave-absorbing substrates, may exhibit reduced efficiency, necessitating the use of additives or alternative solvents. Safety concerns, including the management of high pressures and rapid heating, also require careful protocol optimization. Future research should focus on the development of continuous-flow microwave systems, improved reactor design for large-scale synthesis and hybrid techniques that combine microwaves with other green methodologies, such as photochemistry or biocatalysis. Moreover, mechanistic studies aimed at elucidating the effects of microwave irradiation on reaction pathways could provide fundamental insights to expand the applicability of MAOS across diverse chemical transformations. Addressing these challenges will be essential to fully realize the potential of MAOS as a sustainable and versatile tool in modern organic synthesis.

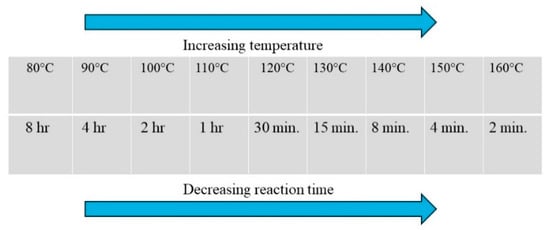

The theoretical basis to convert a batch reaction to a microwave-assisted synthesis is explained by Thumb rule (Figure 2) [27]. In MAOS, a widely acknowledged empirical guideline suggests that microwave irradiation can reduce reaction times by approximately an order of magnitude compared to conventional heating methods, while maintaining comparable yields and selectivity. This heuristic is grounded in the principles of dielectric heating, where microwave energy couples directly with polar molecules or ions in the reaction medium, resulting in rapid and volumetric heating. Unlike conventional conduction or convection heating, which relies on heat transfer from the vessel walls, microwave energy can produce localized superheating and non-equilibrium temperature distributions at the molecular level, thereby accelerating reaction kinetics.

Figure 2.

Thumb rule.

However, the applicability of this “thumb rule” is constrained by several factors. The efficiency of microwave heating is influenced by the solvent’s dielectric properties, the geometry of the reaction vessel, and the scale of the reaction. For instance, solvents with low dielectric constants may not absorb microwave energy effectively, leading to inefficient heating. Additionally, the microwaves penetration depth is limited, which can result in uneven heating, especially in larger reaction volumes.

Furthermore, not all reactions uniformly respond to microwave irradiation. Some reactions may exhibit enhanced rates, while others may show no significant difference or even decreased yields under microwave conditions. This variability underscores the importance of empirical optimization and mechanistic studies when adapting traditional reactions to microwave-assisted methods [28].

Therefore, while the “thumb rule” serves as a useful starting point, it is essential to consider the specific characteristics of each reaction system. Systematic experimentation and a thorough understanding of the underlying principles of microwave heating are crucial for successfully translating batch reactions to microwave-assisted synthesis.

This guideline helps the researcher to understand how to set up a microwave reaction starting from a traditional heating reaction; thus, considering a batch reaction conducted at 80 °C for 8 h if we apply an increase of 10 °C to the reaction time (i.e., 90 °C), the reaction will work in 4 h. If the reaction will be conducted at 100 °C it will take 2 h. Clearly, this principle is useful to understand how to translate a batch synthesis reaction into a microwave-assisted reaction. Generally, microwave-assisted reactions are never carried out below 100 °C to take advantage of high-temperature effect.

Several case studies demonstrated its applicability and effectiveness across diverse reaction classes. For instance, the synthesis of nitrogen- and oxygen-containing heterocyclic scaffolds under microwave conditions has consistently shown significant reductions in reaction times, often by an order of magnitude, while maintaining comparable yields and selectivities relative to conventional heating [29].

This example highlights not only the practical utility of the thumb rule but also its versatility across different solvents, catalysts, and reaction scales. Nevertheless, the outcomes of microwave-assisted reactions remain sensitive to factors such as solvent polarity, vessel geometry, and reaction concentration, underscoring the importance of empirical optimization in each case. By providing concrete examples and case studies, researchers can better understand the scope and limitations of the thumb rule, thereby enhancing its reliability in the design of efficient MAOS protocols. Furthermore, thumb rule can also provide guidance in more complex reaction systems, such as multi-step syntheses or reactions involving multiple reagents. In these contexts, the rule is applied iteratively, with each individual step evaluated according to established principles such as kinetic favorability, thermodynamic stability, or functional group compatibility. While the rule does not replace detailed mechanistic analysis or computational modeling, it serves as a practical tool for prioritizing reaction pathways, selecting suitable reagents, and anticipating potential side reactions. Furthermore, in multi-step syntheses, the cumulative effect of successive transformations can be approximated using the thumb rule, enabling chemists to identify sequences that are likely to proceed efficiently while minimizing undesired byproducts. Nonetheless, the predictive power of the rule diminishes as system complexity increases, necessitating complementary approaches such as experimental screening or theoretical calculations.

In the microwave, a key role is played by the type of solvent used to conduct the reaction and clearly, not all solvents are suitable to be used in a microwave system. Until some years ago the most important parameter to be considered for solvents was the dielectric constant ε′, that indicates the ability of a solvent to polarize in the presence of electromagnetic radiation. Referring exclusively to the dielectric constant, the best solvent was water with a dielectric constant of 78.3 (Table 1), while ethanol shows a dielectric constant of 24.3 and methanol of 32.6; thus, from a first examination water seems to be the best solvent to use in MAOS.

Table 1.

Dielectric constant of solvents.

Currently, the primary parameter to select a solvent to be used in MAOS is not the dielectric constant, but the tangent δ, that is the ratio of ε″/ε′, where ε″ is the dielectric loss and essentially indicates the ability of a solvent to dissipate the electromagnetic energy under heating. The tangent δ, also called dissipation factor, indicates the capacity of a solvent to convert the electromagnetic energy in the form of heat because it incorporates both the dielectric loss and the dielectric constant [30,31]. The table below (Table 2) classifies values of tan δ for solvents as high (tan δ > 0.5), medium (0.1 > tan δ < 0.5), and low microwave absorbing solvents (tan δ < 0.1), and within solvents with tan δ >0.5 and the absolute best solvent is ethylene glycol (tan δ = 1.350), followed by ethanol (tan δ = 0.941) and methanol δ (tan δ = 0.659), while water show a medium tan δ = 0.123.

Table 2.

Tangent δ scale.

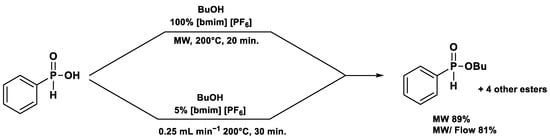

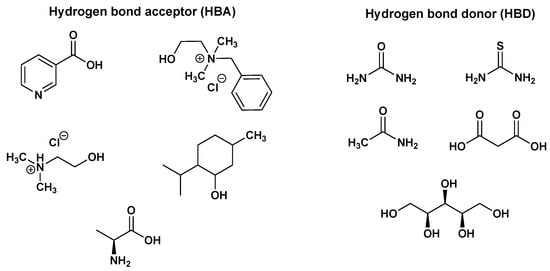

Ethylene glycol (EG) is a high-boiling, polar diol that has been extensively utilized as a solvent in MAOS due to its exceptional dielectric properties. With a dielectric constant of approximately 37 at 25 °C and a high dielectric loss tangent (tan δ ≈ 1.35 at 2.45 GHz), EG efficiently absorbs microwave energy, converting it into rapid and uniform thermal heating. This property enables accelerated reaction kinetics, often reducing reaction times from hours to minutes compared to conventional heating methods. In addition to its dielectric characteristics, EG exhibits a strong hydrogen-bonding capability, which can stabilize polar transition states and reactive intermediates, thus influencing reaction selectivity and yield. However, its chemical reactivity must be carefully considered; the hydroxyl groups of EG can act as nucleophiles or reducing agents under certain conditions, potentially leading to side reactions such as ether formation, esterification, or oxidation products. To minimize these risks, reaction parameters including temperature, microwave power, reaction time and stoichiometry are carefully optimized, and inert atmospheres or stabilizing additives may be employed. Analytical monitoring using NMR, HPLC, or mass spectrometry is essential to detect trace byproducts and confirm that EG functions primarily as an inert solvent. The high boiling point of EG also allows reactions to be conducted at high temperatures under microwave irradiation without significant solvent loss, making it particularly suitable for high-temperature transformations, cyclizations, or condensations in organic synthesis. Overall, EG combines excellent microwave absorption with thermal stability, offering both kinetic and mechanistic advantages, provided that its potential reactivity is carefully controlled. Clearly, reactions could be carried out in water, which is why MAOS is considered a part of green chemistry, but ethanol and methanol are also green solvents with a low environmental pollution. Instead, the solvents that have a low delta tangent (less than 0.1) are all non-polar solvents, such as chloroform, dichloromethane, toluene, and hexane, which are those that did not polarize. For example, olefin metathesis reactions can be carried in a microwave reactor; however, these reactions are 2 + 2 cycloadditions and could occur if the metallo-cyclobutane is well solvated, and this happens with dichloromethane (DCM). However, this will imply a longer run time, due to poor polarization of DCM, and thus the heating of the mixture can be obtained only if reagents are polar. As previously mentioned, the way with which a material will be heated by microwaves depends on its polarity, dielectric constant, and by the nature of the microwave tools used. In microwave irradiation, the main mechanism for dielectric heating is dipolar loss, also known as the re-orientation loss mechanism. When material containing permanent dipoles is subject to a variable electromagnetic field, the dipoles are unable to follow the rapid reversals in the field. As a result of this phase, power is dissipated in the material under form of heat [32,33]. In MAOS, the dielectric constant of a solvent is a key parameter influencing microwave absorption and heating efficiency; however, it is not the sole factor determining reaction outcomes. Solvent polarity and hydrogen bonding are critical factors influencing reaction mechanisms and outcomes. While the dielectric constant of a solvent determines its microwave absorption efficiency, solvent polarity affects the stabilization of transition states and intermediates, thereby influencing reaction rates and selectivity. For instance, in nucleophilic substitution reactions and polar aprotic solvents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) enhance the nucleophilicity of anions by solvating cations, leading to increased reaction rates compared to polar protic solvents such as ethanol, which can form hydrogen bonds with nucleophiles, reducing their reactivity.

Hydrogen bonding further modulates reaction pathways by stabilizing specific conformations or transition states. For example, in the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds, solvents capable of hydrogen bonding can stabilize polar transition states, leading to higher regio- and stereo-selectivity. Conversely, in reactions where hydrogen bonding could lead to side reactions or decomposition, selecting a solvent with minimal hydrogen bonding capability is advantageous.

Additionally, the solvent’s ability to engage in hydrogen bonding can influence the solvation of reactants and intermediates, affecting the overall reaction mechanism. For example, in the synthesis of organophosphorus compounds, the choice of solvent can impact the formation and stability of reactive intermediates, thereby affecting the reaction’s efficiency and product distribution [33].

These examples underscore the importance of considering solvent polarity and hydrogen bonding in the design and optimization of MAOS processes. A comprehensive understanding of these factors enables chemists to tailor reaction conditions for desired outcomes, enhancing the efficiency and selectivity of microwave-assisted reactions.

Microwave reactions can be conducted in the following:

- (a)

- In solution, where the reagents go into solution in the solvent.

- (b)

- Supported reagents could be used; indeed, these are particularly frequent both in these types of reactors and especially in flow chemistry ones. In this case, reagents are anchored to support, which can usually be of polymeric nature, or composed by silica or an alumina matrix. The advantage is that if there is a supported reagent A and reagent B in solution the product will remain linked to the support and will be recovered by filtration. So, it is clear that the use of supported reagents will make the purification processes easier, both in microwave and flow chemistry reactors [33]. The use of supported reagents represents a valuable strategy to enhance reaction efficiency, facilitate product isolation, and minimize solvent usage. Ensuring uniform distribution of the reagent on the support material is critical in achieving reproducible and selective outcomes and this is typically accomplished through controlled impregnation, co-precipitation, or deposition techniques that maximize surface area exposure. Characterization methods such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and infrared spectroscopy are often employed to verify homogeneity and chemical integrity of the supported systems. Equally important is the selection of an inert support, such as silica, alumina, or polymeric matrices, to prevent undesired interactions with the reagents or substrates; in cases where the support possesses catalytic properties, it must be carefully matched to the target transformation to avoid competing pathways. Despite these advantages, the use of supported reagents does present limitations, not all reaction types are compatible, particularly those requiring homogeneous conditions or involving bulky substrates with limited access to the reactive sites. Additionally, reusability of the supported system may decrease over successive cycles due to leaching or degradation of the active species. These considerations highlight both the opportunities and the challenges of integrating supported reagents into MAOS, underscoring the need for tailored design of both reagents and supports for each specific application.

- (c)

- If one reagent is used in excess, specific scavengers can be used to selectively capture the reagents in excess. Considering a 1 equivalent of reagent A and 1.5 of reagent B, the scavenger is used for the half equivalent in excess of reagent B; therefore, in the subsequent filtration the scavenger linked to the excess of the reagent B will remain on the filter, while the reaction product will be recovered solution [33].

- (d)

- Atmosphere: Reactions can be carried out under gaseous atmosphere, using hydrogen rather than inert gas and others. The vials, that will be appropriately inserted into the reactor, are hermetically closed with a PTFE septum, if a reaction under gaseous atmosphere has to be carried out a “gas addiction kit”, will allow to first perform the vacuum into the vial and then to flow the gas of interest directly into the reaction mixture in absolute safe conditions [33].

- (e)

- Temperature: the reactors start from 60 °C and reach up to 300 °C, even if the real working range of activity is between 100 °C and 150° C to avoid reagent decomposition.

- (f)

- Pressure: In terms of pressure, the maximum that can be reached is 30 bar; obviously, the pressure control systems are automated, so that the reactors that are based on artificial intelligence (AI) normally calculate applying Clausius Clapeyron Equation (1) the real pressure required to avoid solvent evaporation at the selected temperature. If, during the reaction time, an overpressure occurs, the reactor stops immediately and vents, so systems are very safe compared to batch synthesis. As an example, if we consider acetone, which has a boiling point of 56 °C at atmospheric pressure, i.e., 1.01 bar that corresponds to 1 atm or 760 mmHg, setting the reaction in the MW reactor at 30 bar, the temperature can be selected until 183.5 °C without solvent evaporation. This law regulates the increase in temperature with the pressure of the solvents inside the reactor and describes that the logarithm of P1/P2 (P1 is 1.01 bar, P2 is 30 bar) is equal to the ratio between the enthalpy of vaporization and the gas constant (R = 8.314 J/(K mol)) multiplied for the difference of the ratios 1/T2−1/T1, where T1 is 56 °C, and T2 is the unknown parameter to find. Thus, solving this equation T2 results in 183.5 °C. Therefore, this calculation allows us to know what is the maximum ceiling beyond which the solvent evaporates even in the microwave reactor [31]. The advancement of MAOS has been closely linked to the integration of sophisticated monitoring and control systems that ensure reproducibility, safety, and scalability. Conventional thermocouple-based monitoring is often inadequate under microwave conditions due to electromagnetic interference and slow response times; consequently, fiber-optic sensors, infrared (IR) pyrometry, and sapphire-crystal probes have become the standard for real-time, non-invasive temperature measurements with high accuracy. Pressure monitoring is achieved through piezoelectric or strain-gauge transducers, enabling precise control of sealed-vessel systems operating at elevated temperatures, thus extending the accessible reaction window. These sensor inputs are processed by advanced control algorithms, typically employing proportional-integral-derivative (PID) regulation to continuously modulate microwave power output and maintain isothermal or ramped profiles. Beyond PID, model predictive control and machine learning (ML) based approaches are increasingly being explored to predict solvent-specific absorption, reaction kinetics and thermal inertia, thereby allowing pre-emptive adjustments rather than reactive corrections. In parallel, the incorporation of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) has transformed MAOS into a data-rich process: in situ Raman, NIR, and UV–Vis spectroscopic probes permit continuous monitoring of chemical transformations, providing mechanistic insights and enabling real-time feedback loops between reaction progress and power modulation. Such integrated sensor-algorithm frameworks not only minimize risks of thermal runaway and by-product formation but also facilitate scale-up from laboratory to industrial applications, aligning MAOS with modern principles of process intensification and quality-by-design.

- (g)

- Concentration of the reaction. Another condition that has to be considered is the concentration of the reaction mixture, that is not specifically relevant if the reaction is unimolecular, while if the reactions are bi- or tri-molecular, the concentration of the reagents is very important for the yield and the speediness of the reaction [33].

- (h)

- Volume of the vials. Another important factor in MAOS is the volume because we should never fill the vials more than half of their capacity, otherwise, there will be no space necessary for the pressure increase [33].

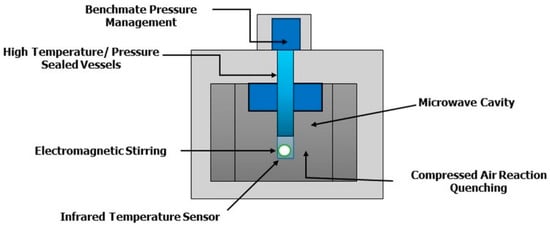

The microwave reactors are made up of magnetron tubes that are positioned in the autotuning cavity which irradiate the sample at 2.45 GHz. These are frequencies that did not allow to break the bonds of the reagents; therefore, they are simply promoters of the polarization of the molecules to ensure that these, in the attempt to align themselves with the oscillating electric field, produce frictions and disperse energy under form of heat. Obviously, the internal parts of these reactors must be made of materials that do not absorb themselves in the microwave’s energy, otherwise this emission will arrive in reduced manner on the sample. The most used materials are quartz, aluminium oxide, and then pyrex glass [33]. The precise overview of the temperature variation during reaction is due to specific sensors; the temperature is measured by optical fibers or infrared sensors. However, these sensors were present in the first generations of reactors. On the contrary, more recent reactors show i-wave sensors that use the new “light emitting technology” (LET), which is able to detect the temperature of the sample and not the temperature of the reaction container. MW reactors normally conduct reactions at pressures up to 30 bar in a closed-vessel or atmospheric pressure in an open vessel [34,35]. Closed-vessel reactions mean that the vial in which the reaction takes place is closed, and the system is under pressure. On the other hand, it is possible to conduct microwave reactions under atmospheric pressure; in this case reactions are in an open vessel, with the vial connected to a refrigerant. In this case, instead of using the heating mantle the mixture is heated by microwave irradiation. The microwave reactors are also equipped with a cooling system, which allows, once the run time of the chemical reaction is finished, to cool the system before releasing the vial, generally not before reaching 40 °C. Cooling occurs automatically for about 20 min; however, if the reactor is connected to a compressed air cylinder, the air is flowed into the autotuning cavity and cooling occurs quickly. Reactions can be performed by introducing into the vial a stirring bar to carry out the reactions under stirring, with the possibility to set the stirring speed as low, medium, or high. The first-generation reactors essentially did not have a touch screen on the reactor itself, but usually are connected with a scart socket to a computer on which there is installed the related software, thus allowing to see the variation of pressure, temperature, and power during the reaction time [34]. Differently, unlike the first-generation reactors, which used infrared or optic fibers as sensors, the latest generation reactors use the i-wave sensors based on the LET, which allows to measure the temperature directly inside the sample. This last generation of reactors also possess an integrated video camera, thus establishing visual contact between the internal cavity of the instrument and the operator. This modern technology allows us to shoot videos during the reaction time and take photos, which can then be found at the end of the run time in a specific section of the reactor. Different types of methods can be set with the latest generation reactors, the most used when we work in closed vessel is the dynamic method, which allows us to set the three main parameters of the reactor, i.e., pressure, temperature, and power. The pressure in these types of apparatus can be set to a maximum of 30 bar, but these artificial intelligences regulate the pressure according to the type of solvent in which the reaction was carried and its δ tangent, or by considering Clausius–Clapeyron equation. Regarding the power, if the solvent is polar (such as ethanol or methanol) it can be set to 70 W–100 W, while if the solvent is non-polar (e.g., dichloromethane) the power must be set in the range 150 W–200 W [34]. The reaction containers can be of 10 mL, 35 mL, or 125 mL for closed-vessel reactions, while 125 mL flasks are used for open-vessel reactions. The novelty of these latest generation reactors is that, without the need to indicate the capacity of the vials, the reactor recognizes the capacity of the reaction container from the type of adapter located in the microwave cavity. Differently, regarding the open-vessel reactions, in this case the method used for the run time is at fixed power; in this case, the microwave irradiation will allow the polarization of the molecules and to convert the kinetic energy under heating; however, the boiling points of the solvents remain those normal at atmospheric pressure [34].

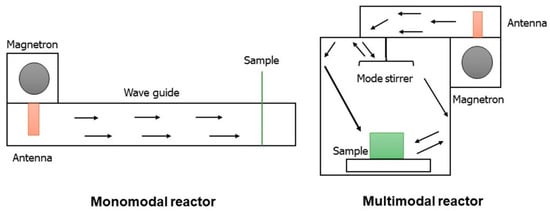

Microwave reactors are divided into two categories: single-mode and multi-mode reactors [35,36]. Single-mode reactors are the most common, and more than 99% of reactors are all single-mode; these reactors are made up of a single magnetron tube emitting an electromagnetic radiation that arrive directly on the sample via this “wave guide”, clearly depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Single-mode and multi-mode reactors.

The multi-mode apparatus [35,36] is widely used for parallel synthesis in which scale-up occurs. These reactors contain more than one magnetron tube because in the parallel synthesis we can put to react up to 32 vessels at the same time, and clearly, a single magnetron tube is not enough to irradiate all vials. From a geometric point of view, these radiations are partially reflected by the walls of the reactor. Inside this reactor there is a “mode stirrer”, which allows the radiation to reach the sample. That is why, in most cases the single-mode reactors are preferred. The power of the reactor reaches up to 1800 W, as we have multiple magnetron tubes to irradiate all these vessels. The stirring speed is eight rotations per minute. The cavity, in the single-mode reactors, is compact, while in the multi-mode reactor the cavities are roomy to accommodate up to 32 vials, in fact, there is a carousel with 32 vials and therefore the auto-tuning cavity is very large. In a closed-vessel, but also in an open vessel, in the single-mode reactors the maximum capacity of the reactor container is 125 mL, and in multi-modal reactors even up to 1 L. That is why it is used for scale-up synthesis. The single-mode reactor has lower emission power because it uses only one magnetron tube, while the multi-mode ones show a higher emission power [35,36]. However, the field density is greater in single-mode apparatus because the radiation arrives directly on the sample while in multimode reactor, as it is partially reflected by the walls of the reactor, the field density will be, all in all, lower. This is the reason why, except for parallel or scale-up synthesis, that the reactors are preferentially all in single-mode. Figure 4 shows the microwave cavity.

Figure 4.

Microwave cavity.

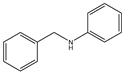

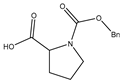

A balanced evaluation of single-mode and multi-mode microwave reactors is essential, as each design offers distinct advantages and disadvantages that directly impact reaction performance and product yields. Single-mode reactors deliver focused and uniform microwave irradiation, ensuring precise temperature control and reproducibility, which is particularly advantageous for mechanistic studies, optimization of sensitive reactions, and cases where selectivity is crucial. Their main limitations, however, lie in the restricted reaction volume and the challenges associated with scaling up, which limit their applicability in preparative or industrial contexts. On the other hand, multi-mode reactors enable the simultaneous processing of larger volumes and multiple samples, making them more suitable for high-throughput synthesis and scale-up experiments. Yet, the broader distribution of microwave energy in multi-mode systems often results in less homogeneous heating, the formation of hot spots and reduced control over reaction parameters, which may compromise reproducibility and selectivity [33]. The choice of reactor design therefore depends on the specific goals of the experiment; when high precision, control, and reproducibility are required, single-mode systems are generally preferred, whereas multi-mode systems are advantageous when throughput and scalability are prioritized. Ultimately, these differences have important implications for reaction outcomes, since single-mode reactors tend to provide higher consistency and selectivity, while multi-mode reactors offer efficiency in processing but may require additional optimization to achieve comparable yields and reproducibility. After the insertion in the microwave cavity of vials closed with the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) septum, the pressurizer called benchmate pressure management closes automatically. Clearly, Figure 4 shows the microwave cavity where there is a magnetron tube that irradiates the reaction mixture and on the bottom of the apparatus, an infrared sensor is localized. Eventually, the connection with a compressed air cylinder on the back of the reactor, allows a faster cooling of the reaction mixture in 10 min instead of 20 min. The modern reactors have the possibility to add various modules, such as the autosampler with the aim to carry out multiple reactions in sequence, e.g., if we perform 12 metathesis reactions, each with a run time of 1 h, it is possible to put all the 12 reactions in the autosampler, where each reaction will be put to react one at a time [33]. At the same time, it is possible to insert several modules to carry out reactions under inert gas or simply hydrogenations. In this case it is necessary a “gas addition kit” which shows a pressure regulator for the gas pressure. Through one of the valves, it is possible to connect the gas addition kit with the hydrogen cylinder, by conducting the hydrogenation in absolute safe conditions. Alternatively, if we want to perform a reaction under inert gas, the gas addition kit has to be connected with a nitrogen or with a helium cylinder; of course, before flowing the gas into the vial, the vacuum is applied into the vial. In Table 3 a few examples are depicted, like the formation of an imine which is then hydrogenated or the reduction of nitro groups to amino groups. The integration of additional modules such as autosamplers, gas addition kits, and other auxiliary components into MAOS systems represents an important strategy for expanding functionality and enhancing experimental flexibility. Ensuring compatibility with existing reactor designs and control systems typically requires standardized hardware interfaces, robust communication protocols, and software integration that allows seamless synchronization of operational parameters, such as temperature, pressure, and microwave power. However, this process is not without challenges. Differences in reactor geometries, vessel configurations, and control architectures may restrict the straightforward incorporation of external modules, while maintaining reliable safety features, such as pressure release mechanisms and temperature cutoffs, can further complicate integration. Additionally, the addition of modules may increase system complexity, raising concerns related to calibration, maintenance, and potential sources of error. Limitations may also arise in terms of cost, as advanced modular systems can substantially increase the investment required, which may not be feasible in all laboratory contexts. Thus, while modular integration significantly broadens the scope of MAOS, it requires careful attention to system compatibility, reliability, and safety to ensure that the benefits outweigh the potential drawbacks.

Table 3.

Hydrogenation of various substrates.

It is also possible to carry out a reaction at sub-ambient temperature [37]. To perform a reaction at −78 °C the reactor is normally equipped with a cool-mate kit, which consists of a reservoir where liquid nitrogen or a perfluorinated liquid can be loaded, in addition there is an “in” and an “out” valve that allows the entry of the cryogenic liquid in the system, exactly in the external portion of the reaction container, cool the reaction and then return to the reservoir. Since this dissipation of energy in the form of heat is reduced by contact with the cryogenic liquid, therefore, microwave heating is used to increase the kinetic energy of the molecules, thus letting the reagents react quickly with an increase of the reaction yield. In addition, modern reactors are equipped to perform microwave-assisted solid phase synthesis, in this case the reactors no longer work at room temperature at 25 °C, but at very high temperatures.

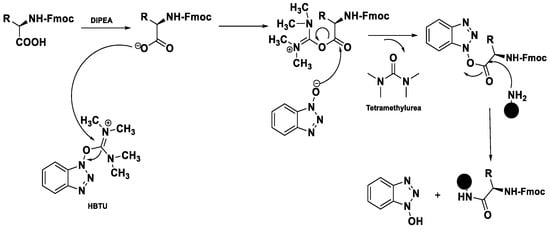

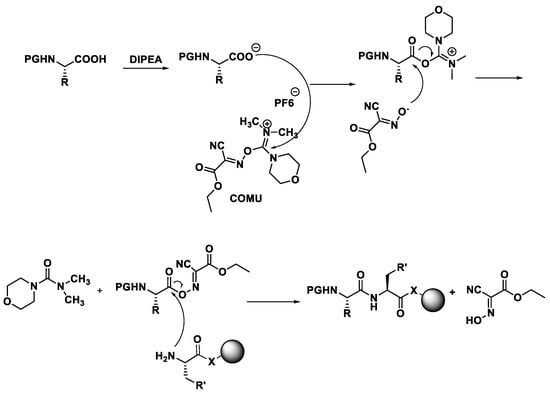

These modern reactors perform a coupling cycle in 2.5 min, with respect to batch synthesis in which coupling can be performed in 12 h, because of the low kinetic of this type of reaction. These efficient reactors present 27 working stations to load the amino acids, the 20 natural aminoacids (L-configuration) and in addition it is possible to load unnatural aminoacids (D-configuration), which give greater enzymatic stability to proteolysis to the synthesized peptide. There are additionally two stations where it is possible to load the DIPEA and then coupling reagents, like HBTU or similar.

The most recent reactors show a 24-station autosampler, and in addition a five-channel pump system which even allows to inject four or five different external reagents within the reaction run time. This system is connected to software, because based on the positions of the amino acids, we have to set the exact sequence of the polypeptide chain that have to be synthesized.

2. Applications of Microwave Reactions

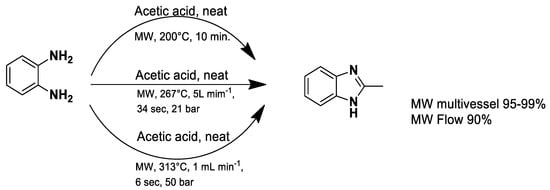

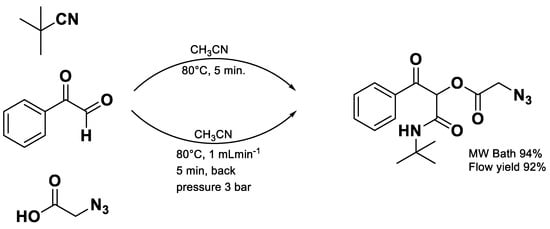

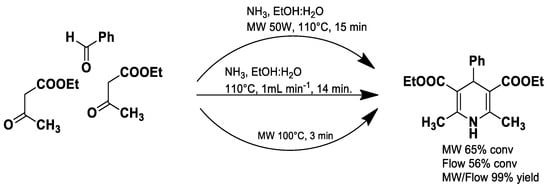

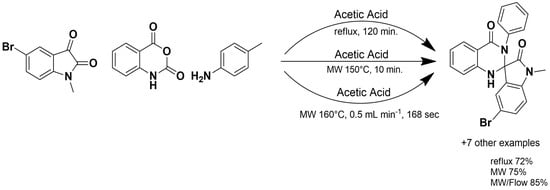

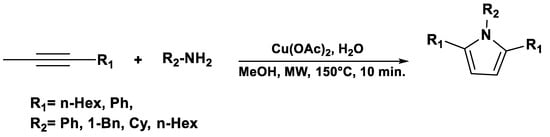

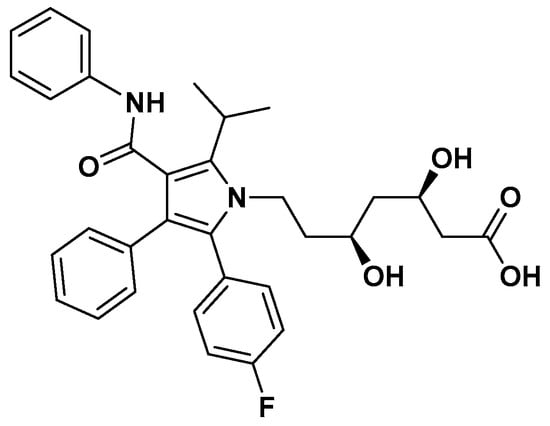

Microwave heating, widely known for cooking, has been successfully employed in various industrial and therapeutic applications, including nanomaterial synthesis [38,39,40,41], nanotechnology [42], and organic chemistry [43]. Notably, MAOS is primarily focused on pharmaceutical research and the development of new potential drugs, also known as drug discovery. The microwave-assisted synthesis of heterocyclic compounds offers several advantages in the pharmaceutical field compared to traditional synthetic protocols [44,45,46]. The construction of N-heterocycles [47] using microwave technology represents a sustainable approach to design novel molecules [48]. In MAOS of N-heterocycles, scalability and safety are crucial challenges. Industrial implementation requires optimized reactor design, with continuous-flow microwave systems offering improved heat transfer, reproducibility and safer operation compared to batch processes. In addition, strict safety protocols and the use of greener solvents help to minimize risks for operators and reduce environmental impact, making large-scale applications both feasible and sustainable. While significant progress has been made in the synthesis of pyridines, pyrazoles, indoles, and related frameworks, this methodology can in principle be extended to a broader range of N-heterocycles, including quinazolines, imidazoles, benzimidazoles, triazoles, and fused polycyclic systems. However, the applicability of microwave irradiation is not universal and strongly depends on the polarity of the solvents, the dielectric properties of the reagents, and the stability of the intermediates formed under high-energy conditions. Reactions involving non-polar substrates or thermally labile functionalities may be less amenable to microwave activation and scale-up can pose additional challenges due to limitations in microwave penetration depth. Thus, although microwave-assisted methodologies offer a versatile platform for N-heterocycle synthesis, careful consideration of substrate compatibility, reaction conditions, and scalability is required to fully exploit their potential. Clearly, microwave irradiation often leads to significantly reduced reaction times, in some cases decreasing from several hours to only a few minutes, which is attributed to rapid and uniform dielectric heating. Yields are frequently reported to be comparable or higher than those obtained under traditional conditions, particularly in reactions that benefit from localized superheating and enhanced molecular mobility. Selectivity outcomes, however, appear to be more context-dependent; while certain transformations demonstrate improved regio- or stereo-selectivity under microwave conditions, others show no marked difference compared to classical heating. These variations may arise from differences in the thermal profiles of the systems and the possible involvement of non-thermal microwave effects, although the latter remains a subject of ongoing debate. Overall, the emerging consensus is that microwave-assisted synthesis provides a powerful tool for improving efficiency and sustainability in organic chemistry, but more systematic studies directly contrasting it with conventional approaches are required to clarify its full advantages and limitations.

In applications of microwave reactions, solvents and catalysts play a crucial role in determining the efficiency and selectivity of MAOS, particularly in the synthesis of N-heterocycles. The choice of solvent is especially important, as its dielectric properties govern the extent to which microwave energy is absorbed and converted into heat. Polar solvents such as ethanol, methanol, or dimethylformamide (DMF) are generally more effective under microwave conditions because they couple efficiently with the electromagnetic field, leading to rapid and homogeneous heating. In contrast, non-polar solvents absorb microwave energy poorly, which may reduce the reaction rate or necessitate the use of co-solvents. Catalysts, both homogeneous and heterogeneous, further enhance the outcome of microwave-assisted transformations by lowering activation barriers and enabling milder conditions, often leading to higher yields and improved regio- or chemo-selectivity. Additionally, solid-supported catalysts and ionic liquids can act as microwave absorbers, creating localized “hot spots” that promote reaction efficiency. The synergistic interplay between solvent and catalyst selection therefore not only dictates the feasibility of microwave-assisted synthesis but also strongly influences product distribution, reaction kinetics and overall sustainability of the process.

2.1. Synthesis of N-Heterocycles

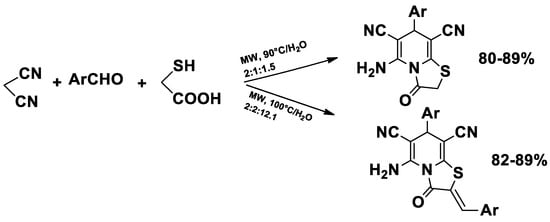

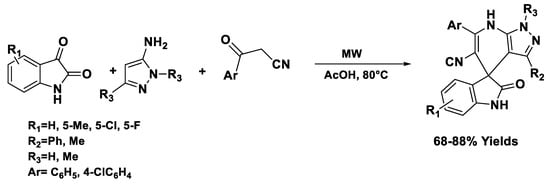

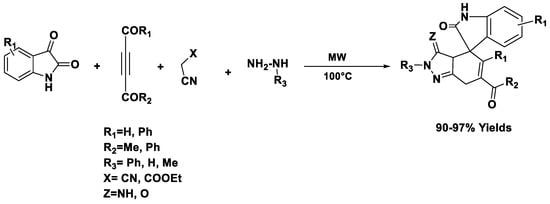

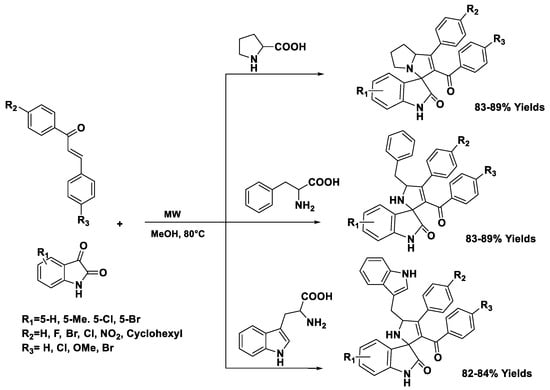

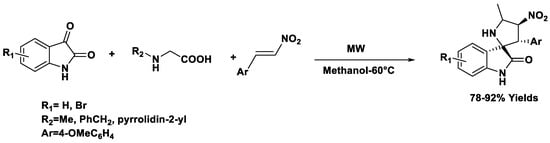

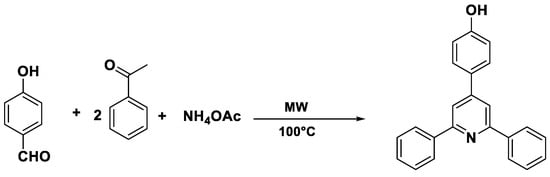

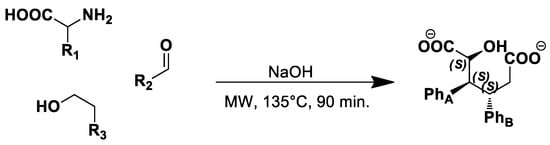

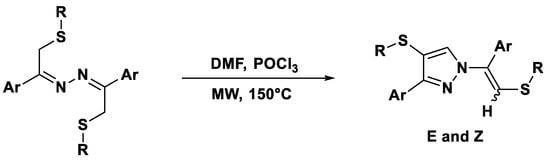

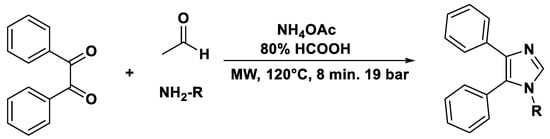

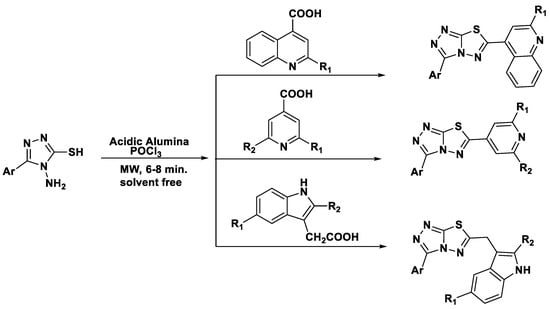

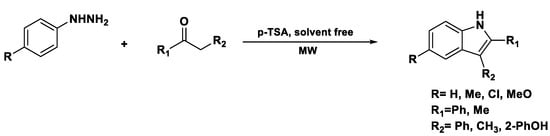

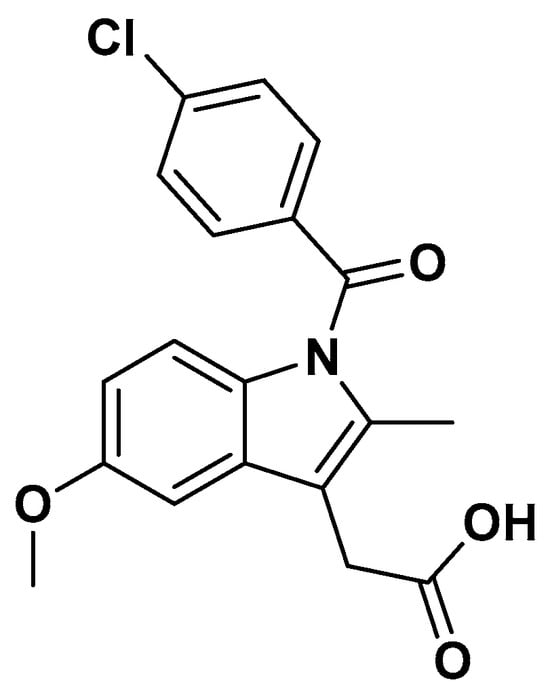

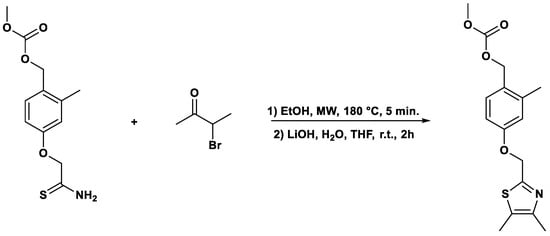

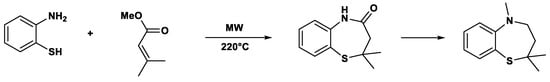

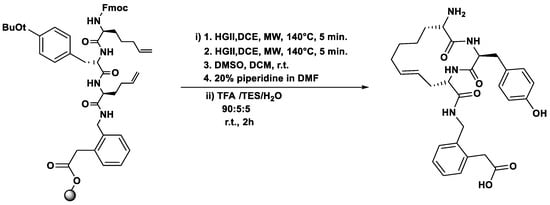

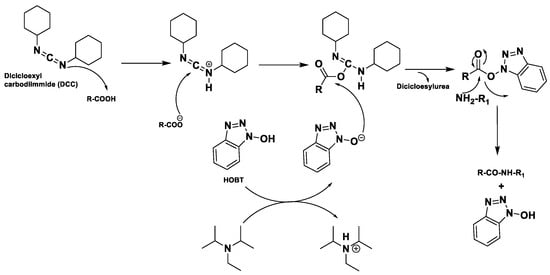

Thiazolopyridines and related fused heterocyclic compounds exhibit significant biological activity [49], and their chemical synthesis has been achieved via microwave-assisted reactions using malononitrile, aromatic aldehydes, and 2-mercaptoacetic acid in water (Scheme 1) [50].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of thiazolopyridines.

These compounds exhibit several pharmacological activities, including antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects, making microwave-assisted strategies particularly valuable for rapidly generating libraries of bioactive derivatives for drug discovery.

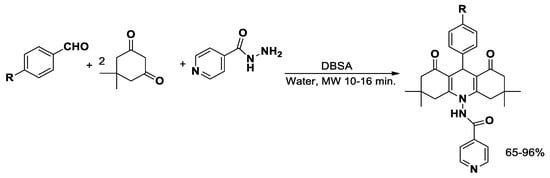

p-Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (DBSA) is an acidic catalyst with surfactant properties that facilitate the dissolution of organic materials. It is widely used to synthesize novel isoniazid (INH) analogues [51] via microwave irradiation using benzaldehydes and dimedone in water as reagents with 80–90% of yields (Scheme 2). Isoniazid analogues, derivatives of the well-known antitubercular agent, have been extensively investigated for their enhanced activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, including drug-resistant strains. In addition to their primary anti-tubercular effects, several analogues exhibit broader antibacterial properties, and some have demonstrated anticancer and enzyme inhibitory activities, highlighting their potential as versatile bioactive compounds. MAOS has proven particularly useful in the rapid and efficient generation of diverse isoniazid derivatives, facilitating the exploration of structure–activity relationships and the development of novel therapeutic candidates [52].

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of isoniazid analogues.

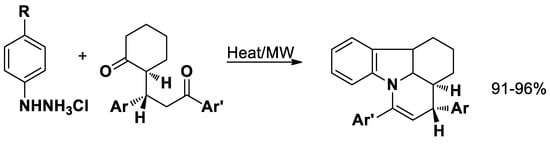

The reaction between 2-(3-oxo-1,3-diarylpropyl)-1-cyclohexanones and phenylhydrazine hydrochloride in water results in the formation of pyridocarbazoles with excellent yield (Scheme 3) [53].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of pyridocarbazoles.

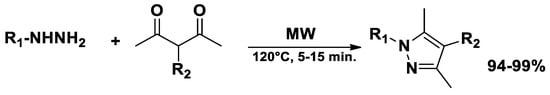

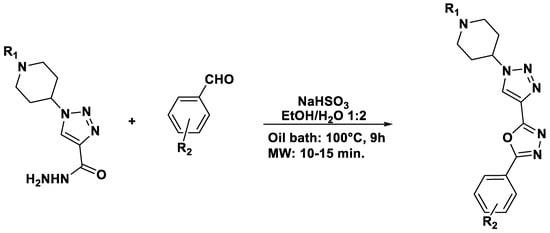

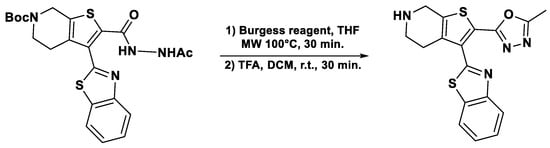

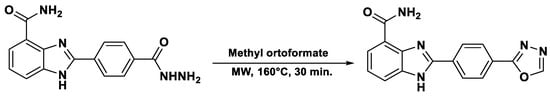

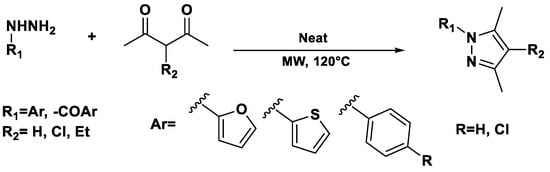

Pyrazoles and diazepines have been successfully synthesized under solvent- and catalyst-free conditions through microwave-assisted chemical synthesis, [54] achieving complete conversion at 120 °C in 5−15 min with 90% of yield (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of pyrazoles.

2.2. Cross-Coupling Reactions for Modifying Heterocycles

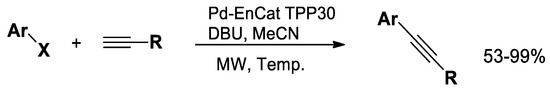

Additionally, C−C coupling reactions, such as the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction, can be efficiently conducted under microwave irradiation [55,56,57]. Cross-coupling reactions, such as Suzuki and Sonogashira, enable the rapid functionalization of heterocycles, providing access to derivatives with enhanced antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory and antiviral activities. When combined with microwave-assisted synthesis, these reactions offer shorter reaction times, higher yields, and efficient generation of pharmacologically relevant heterocyclic libraries for drug discovery. In particular, the Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction is typically performed using aryl iodides and bromides with terminal alkynes, utilizing reusable Pd-EnCatTM TPP30 (encapsulated Pd with PPh3) catalysts to obtain excellent yields (Scheme 5) [58].

Scheme 5.

Cross−coupling reaction.

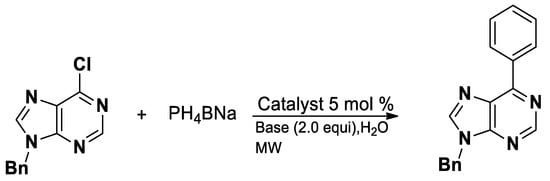

The synthesis of nucleosides from 6-chloropurines is enabled using an arylation reagent and sodium tetraarylborate in water under microwave irradiation (Scheme 6) [59].

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of 6-arylpurines.

These compounds demonstrated a wide range of pharmacological activities, including anticancer, antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects, often through modulation of kinases, nucleic acid synthesis, or enzyme inhibition. The introduction of diverse aryl groups at the C6 position enables fine-tuning of target specificity and potency, making 6-arylpurines valuable scaffolds in medicinal chemistry [60].

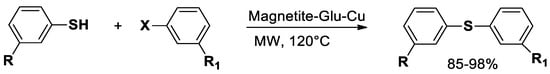

Furthermore, the formation of C−S bonds in several drug intermediates and pharmaceutical compounds (Scheme 7) [61] is achievable using magnetite-Glu-Cu as a catalyst for the reaction between aryl halide and thiophenol under microwave irradiation 90% of yield [55].

Scheme 7.

Coupling of thiophenols with aryl halides.

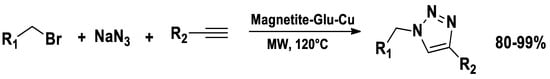

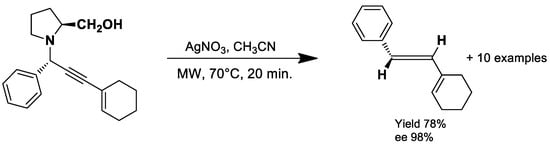

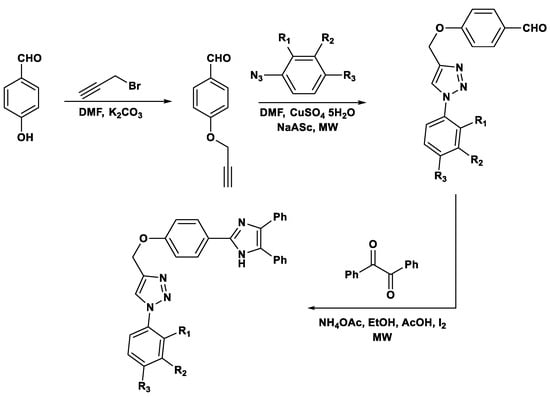

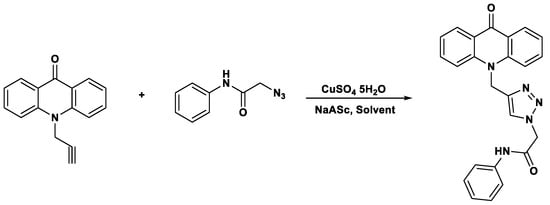

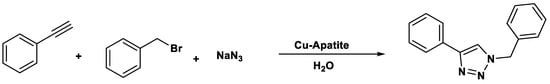

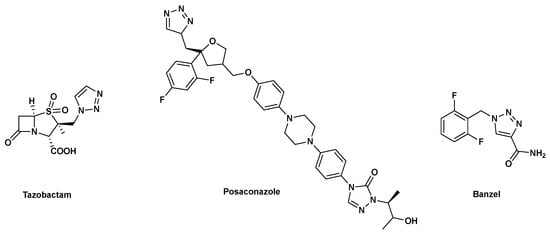

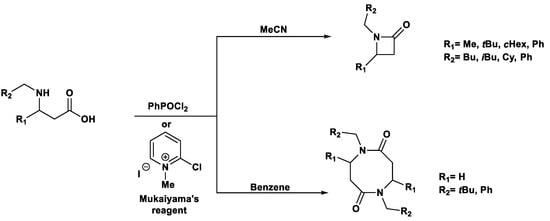

2.3. Click Chemistry: 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions

In the case of click chemistry, microwave-assisted protocols have proven to be highly efficient at the laboratory scale; however, their translation to industrial settings requires careful attention to scalability and safety. Continuous-flow microwave reactors provide a practical solution, as they ensure controlled energy input, efficient heat dissipation and reproducible reaction outcomes while minimizing the risks associated with batch processing. Moreover, the inherently high selectivity and mild conditions of click reactions align well with green chemistry principles, facilitating safer operations and reducing environmental impact. Thus, the integration of advanced reactor technologies with microwave-assisted click chemistry offers a viable route toward sustainable large-scale applications. For instance, they can be utilized to perform 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions, commonly known as click chemistry, in which an alkyne reacts with an azide to form 1,2,3-triazoles. These triazoles can be selectively substituted at position four or five using magnetite-Glu-Cu as the reaction catalyst (Scheme 8). The underlying mechanism is generally attributed not to a change in the fundamental reaction pathway of the copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), but rather to the unique mode of energy transfer provided by microwave irradiation. Microwaves interact directly with polar molecules and ionic species in the reaction medium, leading to rapid and homogeneous volumetric heating that minimizes thermal gradients. This results in a higher effective concentration of reactive species at the catalytic sites and a reduction in activation energy barriers through efficient vibrational excitation. In contrast, traditional click chemistry relies on conventional convective and conductive heating, which is slower and often less uniform. Additionally, microwave irradiation has been proposed to promote catalyst activation and improve solubility of reagents, thereby increasing turnover frequency and selectivity. While no evidence supports a fundamentally different mechanistic pathway under microwave conditions, the enhanced kinetics and improved reaction environment provide significant advantages in terms of reaction efficiency, sustainability, and scalability.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles.

The scope of microwave-assisted synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles is extensive, offering a highly efficient and versatile approach for constructing these nitrogen-rich heterocycles. Microwave irradiation significantly accelerates the copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition and other click chemistry reactions, often reducing reaction times from hours to minutes while improving yields and selectivity. This methodology has been successfully applied to a wide range of substrates, including aromatic, aliphatic, and functionalized azides and alkynes, enabling the rapid generation of diverse 1,2,3-triazole libraries for applications in medicinal chemistry, materials science, and chemical biology. Moreover, microwave-assisted protocols frequently allow solvent-free or green chemistry conditions, enhancing sustainability and operational simplicity. However, several limitations persist. The need for specialized microwave reactors can pose an accessibility barrier, and scale-up of microwave reactions remains challenging due to issues with uniform energy distribution in larger reaction volumes. Additionally, some sensitive functional groups may undergo degradation under high-energy microwave irradiation, and precise control over temperature and pressure is essential to avoid side reactions. Despite these challenges, microwave-assisted click chemistry remains a powerful and rapidly evolving tool in modern synthetic chemistry [62,63,64,65].

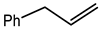

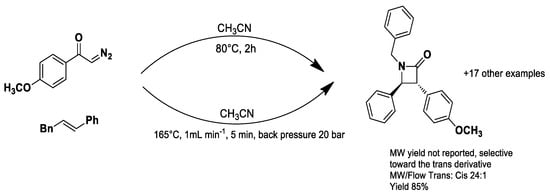

2.4. Cross and Ring-Closing Metathesis

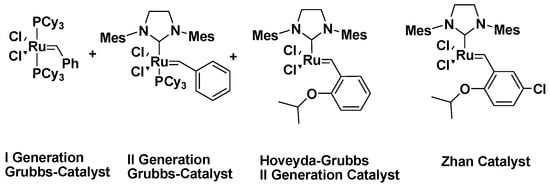

A significant application of microwave reactions is in facilitating cross and ring-closing metathesis with high product yields using appropriate catalysts. For cross and ring-closing metathesis, microwave-assisted protocols have demonstrated significant advantages in terms of reaction rate and selectivity at the laboratory scale, yet their scalability and safety must be carefully addressed for industrial adoption. The use of continuous-flow microwave reactors allows for efficient temperature control, uniform energy distribution and improved catalyst performance, while also reducing the risks associated with pressure build-up in batch systems. In addition, the development of robust catalysts, solvent minimization, and strict adherence to safety protocols contribute to safer operation and lower environmental impact, thus enabling the sustainable large-scale application of microwave-assisted metathesis reactions. Metathesis is a specialized chemical reaction involving several olefins. Before discussing its microwave applications, it is essential to briefly analyze the catalysts developed for these reactions.

Schrock was the first to synthesize metathesis catalysts, producing a molybdenum-based catalyst that was unstable in air and required a nitrogen atmosphere for reactions. Grubbs later developed a ruthenium-based catalyst that was air-stable and yielded high product efficiency. The first-generation Grubbs catalyst contained two phosphine groups but exhibited low reactivity with polar-functionalized olefins. To address this, the second-generation catalyst replaced one phosphine group with an imidazolidinylidene core, which increased the electron density on ruthenium and improved the reactivity with polar functional groups. Further improvements led to the Hoveyda catalyst, a phosphine-free variant with an ortho-isopropoxy group that protected ruthenium from oxidative degradation during storage (Figure 5) [66,67].

Figure 5.

Ruthenium-based catalysts.

Metathesis catalysts, particularly those based on ruthenium and molybdenum, exhibit distinct reactivity profiles and practical considerations that influence their selection for specific transformations. Ruthenium-based catalysts, such as the Grubbs first- and second-generation catalysts, are highly tolerant of functional groups, air, and moisture, making them versatile and user-friendly for a wide range of substrates in both laboratory and industrial settings. However, they generally exhibit lower activity in challenging sterically hindered or electron-deficient olefins compared to molybdenum-based catalysts. In contrast, molybdenum and tungsten alkylidene catalysts often demonstrate higher reactivity and selectivity, particularly in stereoselective and ring-closing metathesis reactions, but they are highly sensitive to air, moisture, and certain functional groups, requiring strictly inert conditions and careful handling. Newer ruthenium catalysts, including Hoveyda-Grubbs derivatives, attempt to balance these traits by combining enhanced stability with improved reactivity, though cost and catalyst loading remain considerations. Overall, the choice of catalyst involves a trade-off between stability, functional group tolerance, activity, and stereoselectivity, highlighting the importance of tailoring catalyst selection to the specific substrate and reaction conditions [68,69,70].

Microwave irradiation offers several distinct advantages in metathesis reactions compared to conventional thermal heating, primarily through rapid and uniform energy transfer that accelerates reaction rates. Enhanced heating efficiency allows reactions to reach the desired temperature in a fraction of the time required by traditional oil-bath or convective heating, often leading to significantly reduced reaction times and improved product yields. Additionally, microwave-assisted metathesis can promote more selective transformations by minimizing thermal gradients and localized overheating, which are common in conventional methods, thereby reducing side reactions and decomposition of sensitive substrates. The technique also facilitates solvent-free or green chemistry approaches, as polar solvents efficiently absorb microwave energy, further increasing reaction efficiency. However, while microwave irradiation provides clear operational advantages, its application is sometimes limited by the scale of the reaction, as uniform microwave penetration in larger volumes can be challenging, and specialized equipment is required. Overall, microwave-assisted metathesis represents a powerful tool for accelerating synthetic protocols and enhancing reaction efficiency while maintaining high selectivity, particularly in small-scale or laboratory settings.

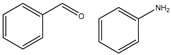

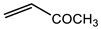

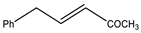

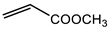

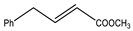

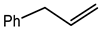

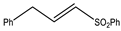

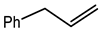

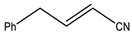

Microwave-assisted reactions between allylbenzene (2.5 equiv.), olefins, and ruthenium catalysts II generation Grubbs catalyst, Hoveyda-Grubbs II generation catalyst (HGII), or Zhan Catalyst (2.5 mol%) were conducted under argon in refluxing dry CH2Cl2 for 5–12 h. The use of microwave irradiation significantly accelerated the reaction, promoting both cross-metathesis (CM) and abb, yielding predominantly E-isomers (99%) (Table 4) [66,71].

Table 4.

Microwave-assisted CM and RCM reactions.

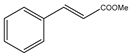

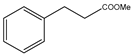

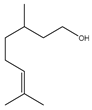

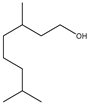

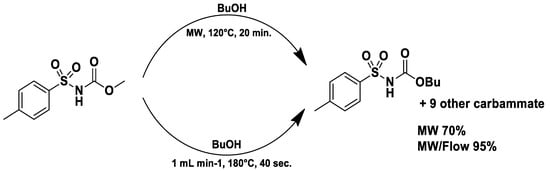

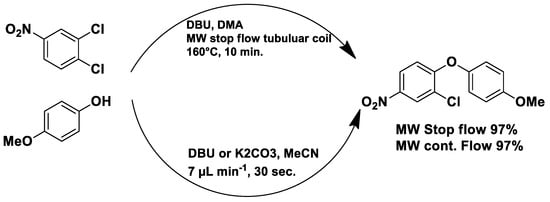

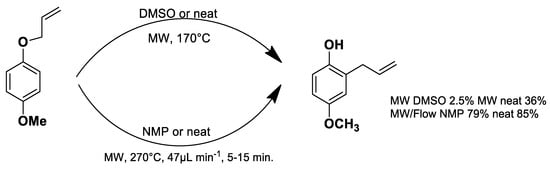

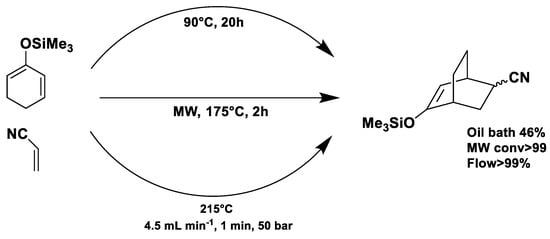

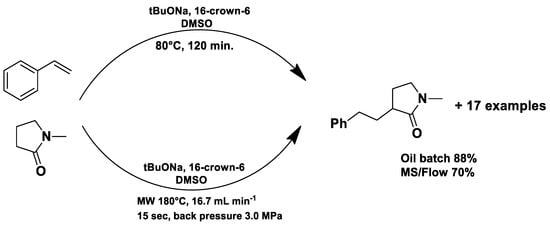

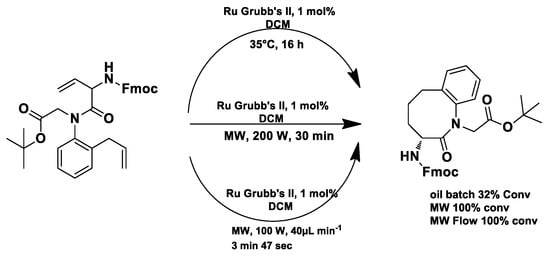

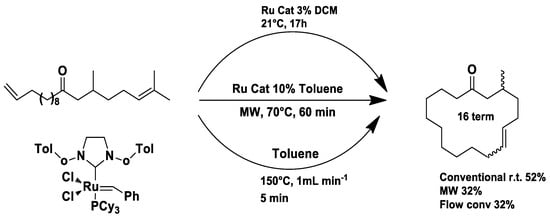

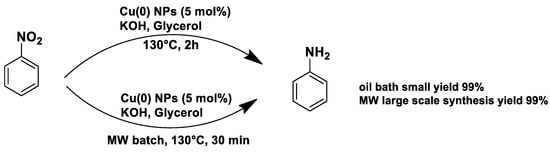

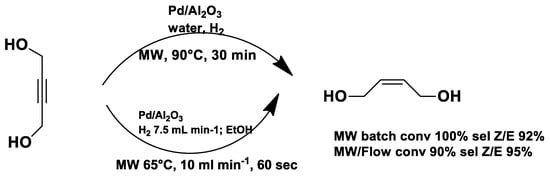

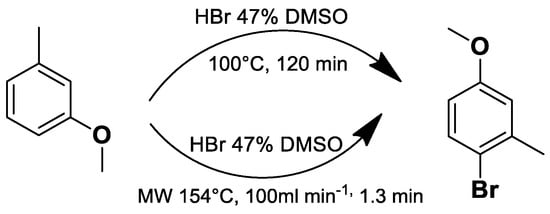

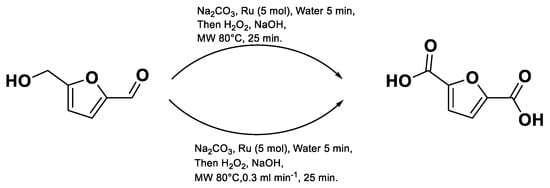

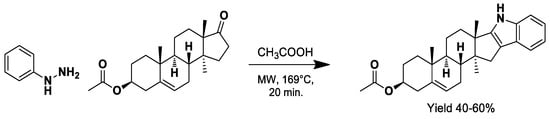

Under conventional conditions (batch synthesis), these reactions typically require 12 h with a heating mantle and reflux condenser. However, microwave reactors reduce reaction time substantially, making them more efficient.