Resensitizing the Untreatable: Zidovudine and Polymyxin Combinations to Combat Pan-Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Synergy Testing

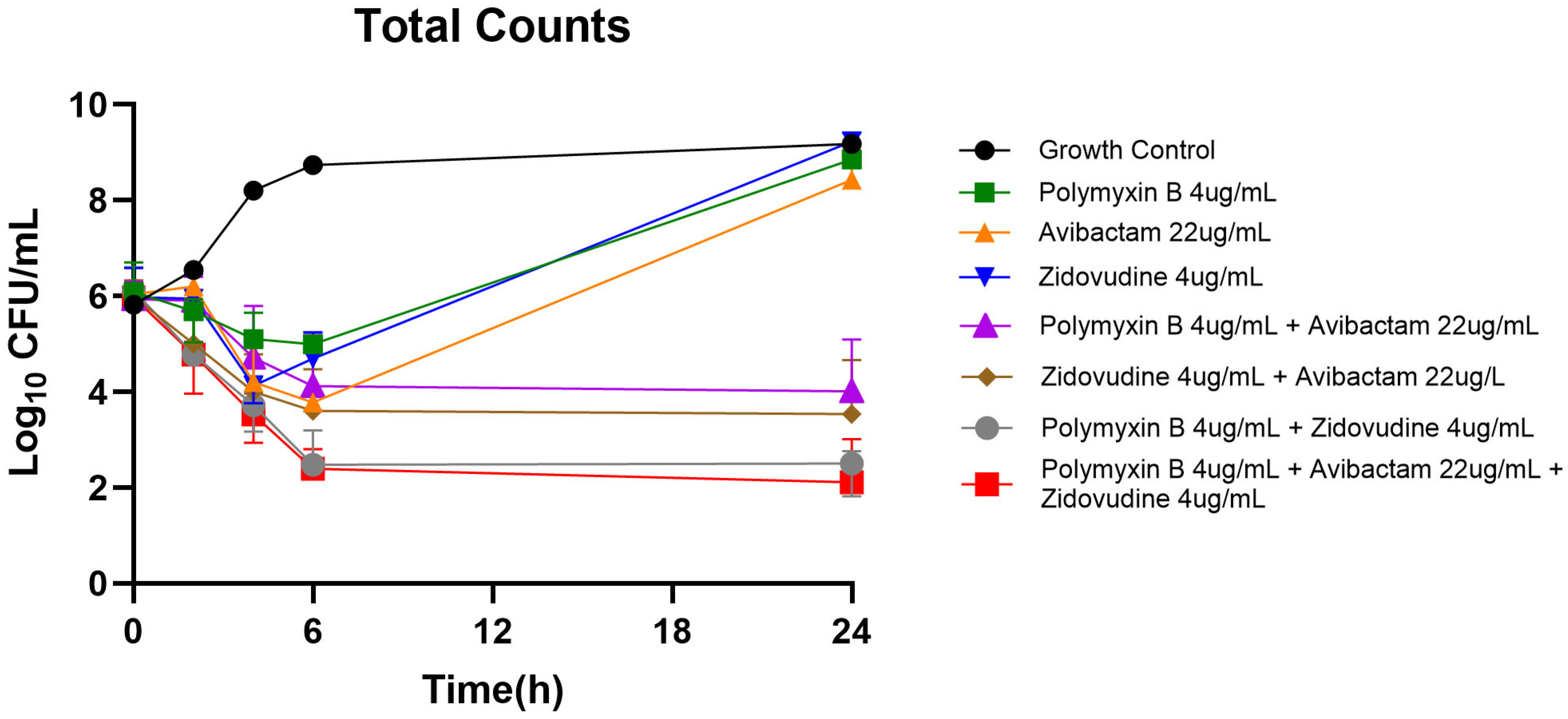

2.2. Static Time-Kill Analysis

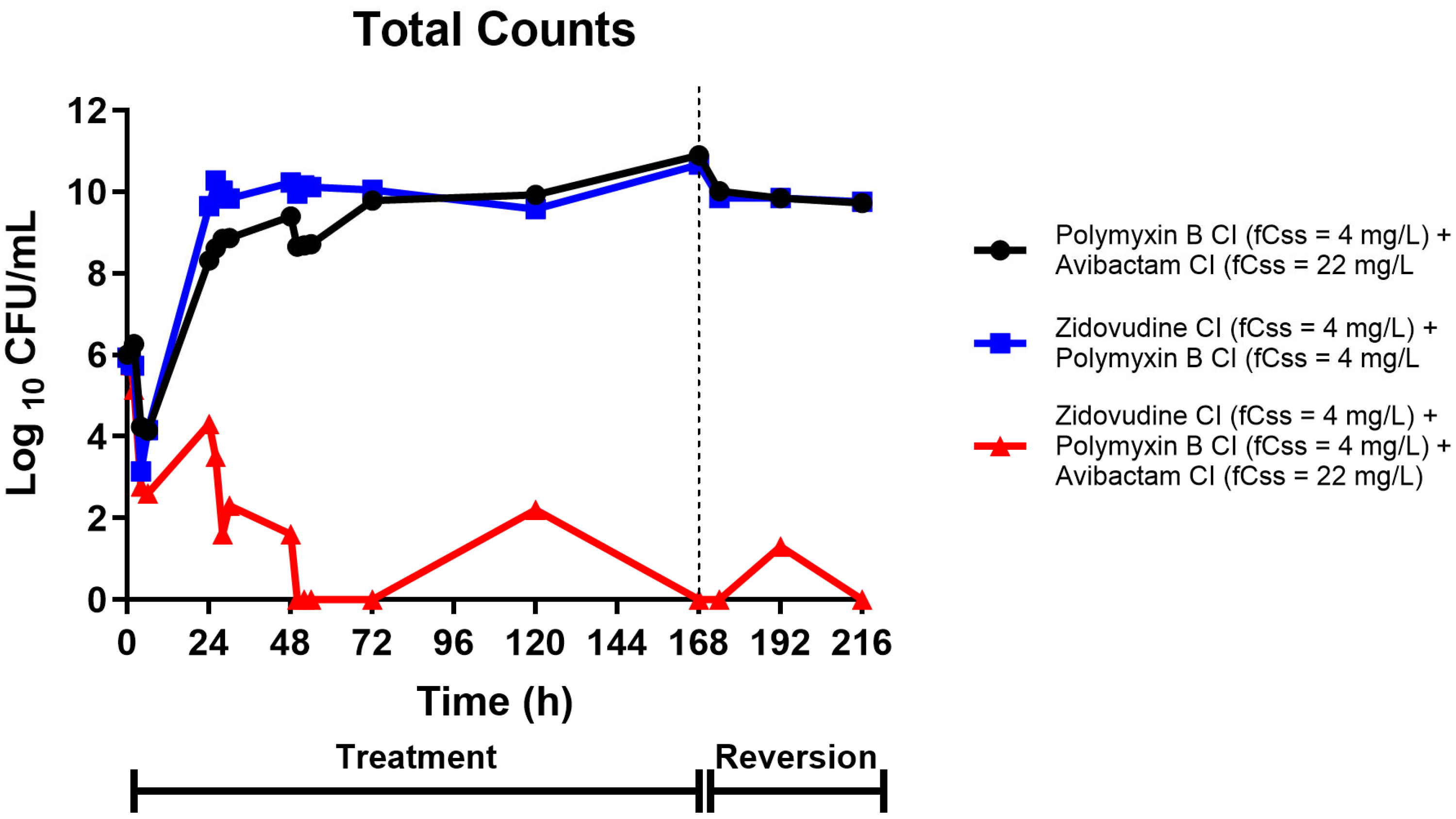

2.3. Hollow-Fiber Infection Model Pharmacodynamics

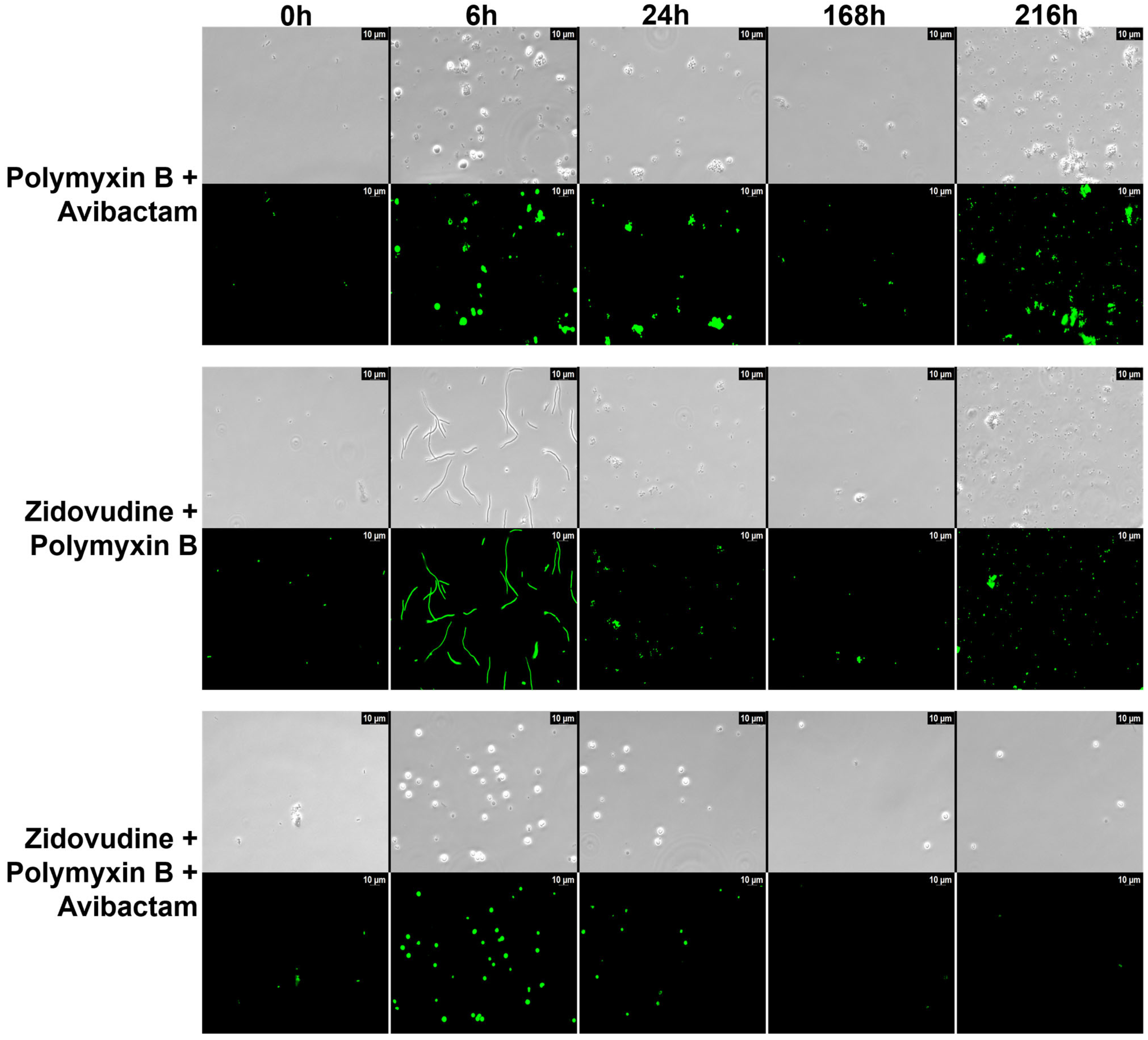

2.4. Microscopic Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

4.2. Static Time-Kill Assays

4.3. Pharmacokinetics and Treatment Regimen Simulations

4.4. Hollow Fiber Infection Model

4.5. Microscopic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duffy, N.; Li, R.; A Czaja, C.; Johnston, H.; Janelle, S.J.; Jacob, J.T.; Smith, G.; Wilson, L.E.; Vaeth, E.; Lynfield, R.; et al. Trends in Incidence of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in 7 US Sites, 2016–2020. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019; US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Tuhamize, B.; Bazira, J. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the livestock, humans and environmental samples around the globe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5873–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, S.; Unali, I.; Bertoncelli, A.; Cecchetto, R.; Mazzariol, A. Ceftazidime/avibactam resistance is associated with different mechanisms in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2021, 68, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, A.S.; Smith, R.D.; Hudson, A.W.; Hernandez, G.E.; Young, T.M.; George, H.E.; Ernst, R.K.; Zafar, M.A. MgrB-Dependent Colistin Resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae Is Associated with an Increase in Host-to-Host Transmission. mBio 2022, 13, e0359521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Jing, N.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Hu, D.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Molecular Mechanism of Polymyxin Resistance in Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli Isolates from Henan Province, China: A Multicenter Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Zheng, W.; Sun, Q.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J.; Ruan, Z. In vivo Emergence of Colistin Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Mediated by Premature Termination of the mgrB Gene Regulator. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 656610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zafer, M.M.; El-Mahallawy, H.A.; Abdulhak, A.; Amin, M.A.; Al-Agamy, M.H.; Radwan, H.H. Emergence of colistin resistance in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli strains isolated from cancer patients. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2019, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Poirel, L.; Jayol, A.; Nordmann, P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial Activity, Susceptibility Testing, and Resistance Mechanisms Encoded by Plasmids or Chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 557–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DeSarno, A.E.; Parcell, B.J.; Coote, P.J. Repurposing the anti-viral drug zidovudine (AZT) in combination with meropenem as an effective treatment for infections with multi-drug resistant, carbapenemase-producing strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pathog. Dis. 2020, 78, ftaa063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonello, R.M.; Di Bella, S.; Betts, J.; La Ragione, R.; Bressan, R.; Principe, L.; Morabito, S.; Gigliucci, F.; Tozzoli, R.; Busetti, M.; et al. Zidovudine in synergistic combination with fosfomycin: An in vitro and in vivo evaluation against multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-W.; Rahim, N.A.; Zhao, J.; Han, M.-L.; Yu, H.H.; Wickremasinghe, H.; Chen, K.; Wang, J.; Paterson, D.L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Novel Polymyxin Combination with the Antiretroviral Zidovudine Exerts Synergistic Killing against NDM-Producing Multidrug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02176-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tian, P.; Li, Q.-Q.; Guo, M.-J.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Zhu, R.-Q.; Guo, Y.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Yu, L.; Li, Y.-S.; et al. Zidovudine in synergistic combination with nitrofurantoin or omadacycline: In vitro and in murine urinary tract or lung infection evaluation against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e0034424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lungu, I.-A.; Moldovan, O.-L.; Biriș, V.; Rusu, A. Fluoroquinolones Hybrid Molecules as Promising Antibacterial Agents in the Fight against Antibacterial Resistance. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, 10th ed.; Document M07-A10; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gómara-Lomero, M.; López-Calleja, A.I.; Rezusta, A.; Aínsa, J.A.; Ramón-García, S. In vitro synergy screens of FDA-approved drugs reveal novel zidovudine- and azithromycin-based combinations with last-line antibiotics against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwell, L.P.; Ferone, R.; Freeman, G.A.; Fyfe, J.A.; Hill, J.A.; Ray, P.H.; Richards, C.A.; Singer, S.C.; Knick, V.B.; Rideout, J.L.; et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (Bw-A509u). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1987, 31, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.M.; Lamont, I.L. Nucleoside Analogues as Antibacterial Agents. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hou, M.; Xu, Y.; Srinivas, S.; Huang, M.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y. Action and mechanism of the colistin resistance enzyme MCR-4. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nang, S.C.; Han, M.-L.; Yu, H.H.; Wang, J.; Torres, V.V.L.; Dai, C.; Velkov, T.; Harper, M.; Li, J. Polymyxin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae: Multifaceted mechanisms utilized in the presence and absence of the plasmid-encoded phosphoethanolamine transferase gene mcr-1. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3190–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryszkiewicz, P.; Malinowska, B.; Schlicker, E. Polypharmacology: Promises and new drugs in 2022. Pharmacol. Rep. 2023, 75, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, E.V.; Ma, C.-X.; Klepacki, D.; Alizadeh, F.; Vázquez-Laslop, N.; Liang, J.-H.; Polikanov, Y.S.; Mankin, A.S. Macrolones target bacterial ribosomes and DNA gyrase and can evade resistance mechanisms. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 1680–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.S.; Bulman, Z.P.; Bulitta, J.B.; Baron, C.; Rao, G.G.; Holden, P.N.; Li, J.; Sutton, M.D.; Tsuji, B.T. Optimization of Polymyxin B in Combination with Doripenem To Combat Mutator Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2870–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-J.; Sheiner, L.B.; D’aquila, R.T.; Hughes, M.D.; Hirsch, M.S.; Fischl, M.A.; Johnson, V.A.; Myers, M.; Sommadossi, J.-P.; The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 241 Investigators. Population pharmacokinetics of nevirapine, zidovudine, and didanosine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ViiV Healthcare. COMBIVIR (Lamivudine/Zidovudine) Tablets: Product Information; ViiV Healthcare Pty Ltd.: Abbotsford, VIC, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://viivhealthcare.com/content/dam/cf-viiv/viivhealthcare/en_AU/files/au-combivir-tablets-pi.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).[Green Version]

- Posner, M.R.; Darnowski, J.W.; Weitberg, A.B.; Dudley, M.N.; Corvese, D.; Cummings, F.J.; Clark, J.; Murray, C.; Clendennin, N.; Bigley, J.; et al. High-dose intravenous zidovudine with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin. A phase I trial. Cancer 1992, 70, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuji, B.T.; Landersdorfer, C.B.; Lenhard, J.R.; Cheah, S.-E.; Thamlikitkul, V.; Rao, G.G.; Holden, P.N.; Forrest, A.; Bulitta, J.B.; Nation, R.L.; et al. Paradoxical effect of polymyxin B: High drug exposure amplifies resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3913–3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.N.; Singh, N.; Smith, N.M.; Klem, J.F.; Cha, R.; Lang, Y.; Chen, L.; Kreiswirth, B.; Holden, P.N.; Bulitta, J.B.; et al. Next generation antibiotic combinations to combat pan-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbo, T.; Louie, A.; Deziel, M.R.; Parsons, L.M.; Salfinger, M.; Drusano, G.L. Selection of a moxifloxacin dose that suppresses drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, by use of an in vitro pharmacodynamic infection model and mathematical modeling. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 190, 1642–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.N.; Klem, J.F.; Liu, Y.; Boissonneault, K.R.; Holden, P.N.; Kreiswirth, B.; Chen, L.; Smith, N.M.; Tsuji, B.T. Maximally precise combinations to overcome metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e0077024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klem, J.F.; Kaur, J.N.; Liu, Y.; Boissonneault, K.R.; Kapoor, S.; Holden, P.N.; Chen, A.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Smith, N.M.; et al. Combatting mobile colistin-resistant (MCR), metallo-β-lactamase (MBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae persisters. JAC-Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaur, J.N.; Klem, J.F.; Hailu, G.S.; Nasief, N.N.; Liu, Y.; Hanna, A.; Chen, A.; Holden, P.; Kapoor, S.; Smith, N.M.; et al. Resensitizing the Untreatable: Zidovudine and Polymyxin Combinations to Combat Pan-Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101531

Kaur JN, Klem JF, Hailu GS, Nasief NN, Liu Y, Hanna A, Chen A, Holden P, Kapoor S, Smith NM, et al. Resensitizing the Untreatable: Zidovudine and Polymyxin Combinations to Combat Pan-Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(10):1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101531

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaur, Jan Naseer, Jack F. Klem, Gebremedhin S. Hailu, Nader N. Nasief, Yang Liu, Allison Hanna, Albert Chen, Patricia Holden, Shivali Kapoor, Nicholas M. Smith, and et al. 2025. "Resensitizing the Untreatable: Zidovudine and Polymyxin Combinations to Combat Pan-Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 10: 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101531

APA StyleKaur, J. N., Klem, J. F., Hailu, G. S., Nasief, N. N., Liu, Y., Hanna, A., Chen, A., Holden, P., Kapoor, S., Smith, N. M., Sutton, M., Li, J., & Tsuji, B. T. (2025). Resensitizing the Untreatable: Zidovudine and Polymyxin Combinations to Combat Pan-Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmaceuticals, 18(10), 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18101531