Abstract

The current Covid-19 pandemic has pointed out some major deficiencies of the even most advanced societies to fight against viral RNA infections. Once more, it has been demonstrated that there is a lack of efficient drugs to control RNA viruses. Aptamers are efficient ligands of a great variety of molecules including proteins and nucleic acids. Their specificity and mechanism of action make them very promising molecules for interfering with the function encoded in viral RNA genomes. RNA viruses store essential information in conserved structural genomic RNA elements that promote important steps for the consecution of the infective cycle. This work describes two well documented examples of RNA aptamers with antiviral activity against highly conserved structural domains of the HIV-1 and HCV RNA genome, respectively, performed in our laboratory. They are two good examples that illustrate the potential of the aptamers to fill the therapeutic gaps in the fight against RNA viruses.

1. Introduction

The current global pandemic caused by SARS-Cov-2 has revealed the fragility of our global health security system. Researchers have been warning governments about the risk of different heath threats we face today, and this outbreak has clearly shown that no country, not even the so called first world, is safe and protected against a sanitary emergency. Among other deficiencies, one of the major limitations to fight against the current viral infection has been the lack of specific therapeutic agents, which is a common fact for many other infections caused by RNA viruses (HIV, HCV, SARS, Ebola, Dengue, and Zika viruses are just few examples of modern viral RNA outbreaks). Researchers have traditionally devoted many efforts to searching for the magic molecule or therapeutic strategy that would allow fighting efficiently against these tiny organisms that so easily put the most evolved living being in check.

RNA viruses store all the required information for the completion of the infectious cycle in their RNA genome. In addition to the information that encodes the viral proteins, the genome includes the information required to efficiently sequester and utilize the cellular machinery and all the information involved in the regulation of the viral processes. RNA viruses have developed different molecular strategies to bear all the information, compacting it in different hierarchical levels of coding within the RNA genome [1,2,3]. Thus, the nucleotide sequence stores essential information in highly conserved structural domains composed of discrete structural units (Figure 1) [1]. This information storage system overlaps and complements the protein coding information. RNA genomes are multifunctional molecules: they act as a replication template, they act as mRNAs, and behave as true non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), playing several essential functions for the viral cycle and the regulation of viral processes [1]. Elucidating the function of each RNA domain and their modus operandi would provide an excellent scenario to address the control of infections caused by RNA viruses, broadening beyond proteins the repertoire of potential target candidates to fight viral diseases. Interfering with the structure of the functional genomic RNA domains or compromising their mechanisms of action should challenge their proper functioning and therefore the completion of the viral propagation cycle. This report shows how aptamers can exploit the structural features of viral genomic RNAs as therapeutic targets, while allowing the implementation of therapeutic tools, which may be developed against a variety of RNA viruses.

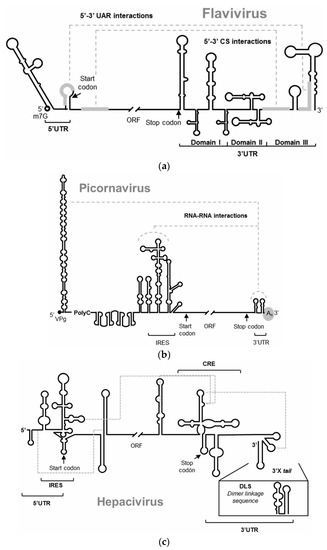

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the 5′ and 3′ ends of the RNA genomes of (a) Flavivirus, represented by the WNV, (b) Picornavirus, (c) Hepacivirus, represented by the HCV. The figures depict the main highly conserved structural RNA elements within their two genomic ends. Defined functional RNA–RNA interactions are indicated with broken gray lines. Translation start and stop codons are indicated by arrows.

2. Aptamers, Selection Procedure, and Features

It was in 1990 that two independent publications from the groups of Jack Szostack and Larry Gold set the basis for the development of the currently known aptamer technology [4,5]. The group of Jack Szostak described the isolation of short RNA oligonucleotides that were able to efficiently bind to organic dyes. They coined the term aptamer to name these binder molecules [4]. On the other hand, the principles of the general strategy for the selection of aptamers that is known as SELEX were defined by the Larry Gold’s group. SELEX stands for systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment [5]. Aptamers are defined as short oligonucleotides, DNA and RNA, that exhibit extraordinary binding efficiency to a specific target molecule [4]. Since then, numerous reports have described the successful identification of aptamers targeting from single molecules like ions, amino acids, nucleotides, antibiotics, etc., to macromolecules like peptides, proteins, or nucleic acids, and even targeting viruses and full cells [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

The potential of this technology was envisioned quite early, and the therapeutic application of aptamers for a wide variety of diseases was proposed. It was in 2004 that the FDA approved the first aptamer to be used as a specific drug. This aptamer, which was named Pegaptanib and commercialized as MACUGEN, was meant for the treatment of the wet age-related macular degeneration [15,16,17]. Nevertheless, the full therapeutic potential of the aptamers is still to be developed.

2.1. SELEX

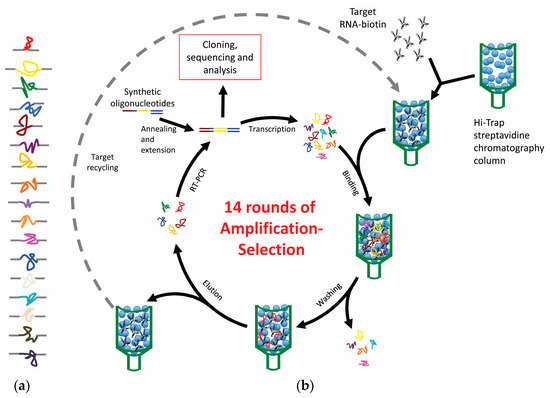

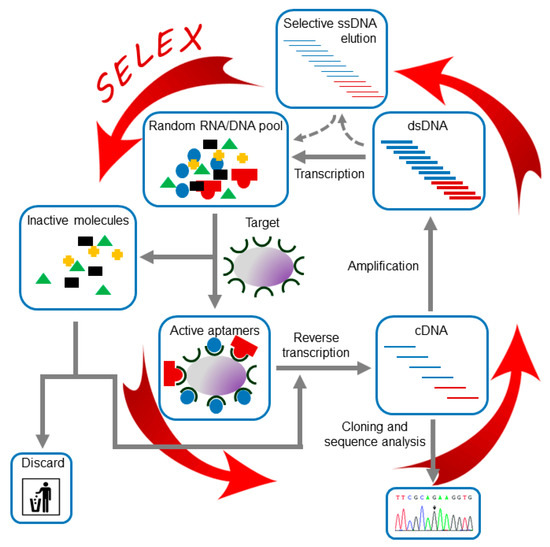

Independently of the application of the aptamers and the nature of their target, all reported aptamers have been identified following a common experimental strategy known as SELEX [5,18], which is outlined in Figure 2. Briefly, a large in vitro synthesized population of variable sequence oligonucleotides, typically ranging from 1012 to 1016 variants, is subjected to the SELEX procedure, which consists of iterative cycles of exposition to the target molecule to allow their binding to the target, separation of those molecules capable of binding and their further amplification. This procedure allows the progressive enrichment of the population in winner molecules for specific binding to the desired target. Those winner molecules are named aptamers.

Figure 2.

SELEX procedure. The figure shows a general scheme of the RNA aptamer in vitro selection process. Broken lines indicate the alternative steps required for the selection of DNA aptamers.

The researcher can control at any time the conditions of the selection and recovery steps during the process. Usually, the main goal is to identify the selection to yield aptamers that exhibit high affinity by a desired target, but the researcher can also pursue the selection of aptamers that achieve stable binding by the imposed conditions. It has been shown that aptamers may bind the ligand molecule with efficiencies that even may exceed that of antibodies for their antigens [19].

2.2. Aptamer Features

Aptamers show some important advantages [19], including that the use of experimental animals is not required for their production, as opposed to antibodies. They can be chemically modified to increase their stability or resistance to nuclease degradation, by means of the addition of certain chemical groups (fluoro, methyl, or methoxy among them) at different positions of the nucleotide, or by replacing specific nucleotides by nucleotide analogs (e.g., locked nucleic acids-LNAs, peptide nucleic acids-PNAs). Thus, in no case the specificity of the nucleotide sequence of the aptamer is altered. Modifications can be also added to improve specific aptamer delivery to the target. Aptamers can also be modified by incorporating different types of labeling (e.g., radioactive, fluorescent) and various functional groups, as well as to conjugate with other molecules (PEG, sugar residues, siRNAs, among others) to achieve many other different functionalities [20].

Specificity of aptamers is determined by both their sequence and their three-dimensional folding. Further, aptamers recognize specific functional groups of the target molecule in a precise spatial distribution. Therefore, aptamers are good candidates to target complexly folded targets. Consequently, in contrast to other nucleic acid based strategies (ribozymes, antisense oligonucleotides, siRNA, among others), aptamers are postulated as excellent candidates to directly interfere with the functioning of essential structural domains of viral RNA genomes.

4. Conclusions

Aptamers offer a potential means for the development of efficient antiviral drugs. Their mechanism resides in the recognition of functional groups in a specific structural context in the target molecule, similar to antigens recognition by antibodies. Viral RNA genomes store essential information for the completion of the viral propagation cycle in structural RNA elements. These elements are grouped in structurally complex domains and regions that coincide with the highest conserved regions of the highly variable viral genome among different viral isolates. The preservation of their structure is essential for the proper functioning of each of these elements, offering an excellent scenario for fighting infections caused by RNA viruses. Aptamers have proven to be capable of interfering with the activity of these essential domains by competing with the interactions they are involved in or by modifying their structure. Different groups have already reported aptamers that induce potent inhibition rates of a variety of RNA viruses by targeting conserved genomic RNA domains. Therefore, aptamers emerge as real molecular tools to fight viral infections.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Unmasking the information encoded as structural motifs of viral RNA genomes: A potential antiviral target. Rev. Med. Virol. 2013, 23, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moomau, C.; Musalgaonkar, S.; Khan, Y.A.; Jones, J.E.; Dinman, J.D. Structural and functional characterization of programmed ribosomal frameshift signals in west nile virus strains reveals high structural plasticity among cis-acting RNA elements. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15788–15795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendra, J.A.; Advani, V.M.; Chen, B.; Briggs, J.W.; Zhu, J.; Bress, H.J.; Pathy, S.M.; Dinman, J.D. Functional and structural characterization of the chikungunya virus translational recoding signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 17536–17545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. Selection in vitro of single-stranded DNA molecules that fold into specific ligand-binding structures. Nature 1992, 355, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Selection of high affinity RNA ligands to the bacteriophage R17 coat protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 228, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.S.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of functional nucleic acids. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999, 68, 611–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, M.; Ellington, A.D. Selection of fluorescent aptamer beacons that light up in the presence of zinc. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008, 390, 1067–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddatz, M.S.; Dolf, A.; Endl, E.; Knolle, P.; Famulok, M.; Mayer, G. Enrichment of cell-targeting and population-specific aptamers by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47, 5190–5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Chavolla, E.; Alocilja, E.C. Aptasensors for detection of microbial and viral pathogens. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 3175–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton, S.; Reyes-Darias, J.A.; Sánchez-Luque, F.J.; Romero-Lopez, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. In vitro and ex vivo selection procedures for identifying potentially therapeutic DNA and RNA molecules. Molecules 2010, 15, 4610–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, T.H.; Zhang, T.; Luo, H.; Yen, T.M.; Chen, P.W.; Han, Y.; Lo, Y.H. Nucleic acid aptamers: An emerging tool for biotechnology and biomedical sensing. Sensors 2015, 15, 16281–16313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.K. Monitoring intact viruses using aptamers. Biosensors 2016, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.W.; Adamis, A.P. Anti-VEGF aptamer (pegaptanib) therapy for ocular vascular diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1082, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, E.W.; Shima, D.T.; Calias, P.; Cunningham, E.T., Jr.; Guyer, D.R.; Adamis, A.P. Pegaptanib, a targeted anti-VEGF aptamer for ocular vascular disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, T.A.; Rosenfeld, P.J. Antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2009, 20, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, S.C. Methods developed for SELEX. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombelli, S.; Minunni, M.; Mascini, M. Analytical applications of aptamers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2005, 20, 2424–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeh, F.; Nsairat, H.; Alshaer, W.; Ismail, M.A.; Esawi, E.; Qaqish, B.; Bawab, A.A.; Ismail, S.I. Aptamers chemistry: Chemical modifications and conjugation strategies. Molecules 2019, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzal-Herranz, A.; Romero-Lopez, C. RNA Aptamers: Antiviral Drugs of the Future. In Proceedings of the 5th International Electronic Conference in Medicinal Chemistry, MDPI AG: Sciforum. 12 November 2019. Available online: https://ecmc2019.sciforum.net/ (accessed on 22 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Theissen, G.; Richter, A.; Lukacs, N. Degree of biotinylation in nucleic acids estimated by a gel retardation assay. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 179, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-López, C.; Barroso-delJesus, A.; Puerta-Fernández, E.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Interfering with hepatitis C virus IRES activity using RNA molecules identified by a novel in vitro selection method. Biol. Chem. 2005, 386, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton, S.; Berzal-Herranz, B.; Garmendia, E.; Cueto, F.J.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Anti-HCV RNA aptamers targeting the genomic cis-acting replication element. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

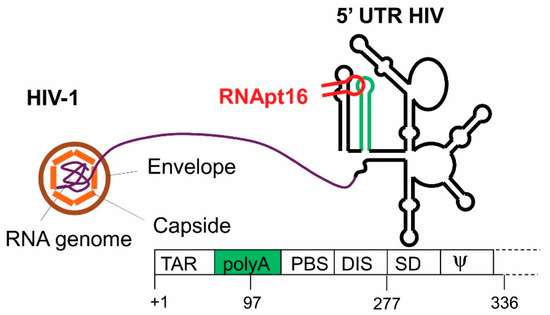

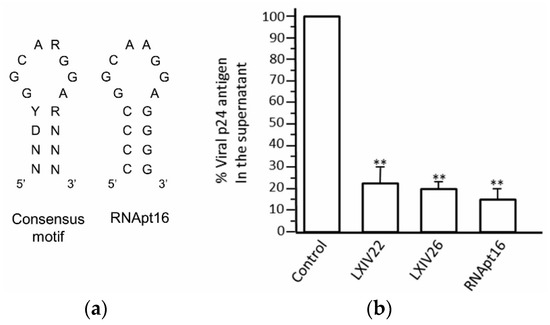

- Sánchez-Luque, F.J.; Stich, M.; Manrubia, S.; Briones, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Efficient HIV-1 inhibition by a 16 nt-long RNA aptamer designed by combining in vitro selection and in silico optimisation strategies. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkhout, B. HIV-1 as RNA evolution machine. RNA Biol. 2011, 8, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzal-Herranz, A.; Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, B.; Ramos-Lorente, S. Potential of the other genetic information coded by the viral RNA genomes as antiviral target. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. The role of the RNA-RNA interactome in the hepatitis C virus life cycle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. The 5BSL3.2 functional RNA domain connects distant regions in the hepatitis C virus genome. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

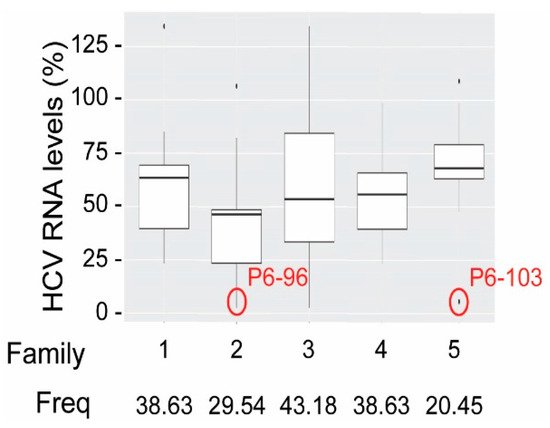

- Fernández-Sanlés, A.; Berzal-Herranz, B.; González-Matamala, R.; Ríos-Marco, P.; Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. RNA aptamers as molecular tools to study the functionality of the hepatitis C virus CRE region. Molecules 2015, 20, 16030–16047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, S.; Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, A. RNA aptamer-mediated interference of HCV replication by targeting the CRE-5BSL3.2 domain. J. Viral Hepat. 2013, 20, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-López, C.; Díaz-González, R.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation by an RNA targeting the conserved IIIf domain. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2994–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-López, C.; Díaz-González, R.; Barroso-delJesus, A.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication and internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation by an RNA molecule. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-López, C.; Berzal-Herranz, B.; Gómez, J.; Berzal-Herranz, A. An engineered inhibitor RNA that efficiently interferes with hepatitis C virus translation and replication. Antivir. Res. 2012, 94, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-López, C.; Lahlali, T.; Berzal-Herranz, B.; Berzal-Herranz, A. Development of optimized inhibitor RNAs allowing multisite-targeting of the HCV genome. Molecules 2017, 22, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).