Abstract

Integrated photoacoustic and ultrasound (PAUS) imaging is a promising technology for both preclinical and clinical applications, as it exploits both advantages of photoacoustic (PA) and ultrasound (US) imaging in high resolutions and acoustic penetration depth, respectively. Using a shared US transducer, data acquisition (DAQ), and signal processing framework, the PAUS system provides simultaneous functional and anatomical information. To date, numerous studies have been reported to demonstrate the capabilities and proposed innovative approaches for the development of the PAUS probes and systems. Key performance parameters, including probe resolution, extending the region of interest (ROI), and increasing the scanning speed, play critical roles in improving image quality, expanding the scanning area, and reducing the scanning time, respectively. This review aims to summarize recent advances in PAUS probes and systems designed for rapid image acquisition. The principles and signal processing are introduced as the fundamentals for designing the PAUS probes and systems. The summaries of the PAUS probe and system design are presented and compared systematically. Furthermore, new approaches in the development of PAUS probes and systems are proposed to enhance their proficiencies in preclinical and clinical applications.

1. Introduction

PA imaging is an emerging, non-invasive technology capable of visualizing molecular functional information of tissue [1,2,3,4,5,6]. When pulsed laser light illuminates tissue, optical absorption induces thermoelastic expansion, generating ultrasound (US) waves that are subsequently detected by US transducers to reconstruct high-resolution PA images. According to the PA principles, this modality has enabled numerous applications ranging from preclinical animal [7,8,9,10,11,12] to clinical human studies [13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, PA relies on optical absorption in tissue, which limits its ability to provide structural information.

US imaging techniques have been widely adopted in clinical applications due to their capability in non-invasive, deep penetration, high spatial resolution, and real-time imaging [19,20]. Based on the different mechanical characteristics of tissue, US imaging visualizes the general structural information that is usually not visible in PA imaging [21,22]. One of the main drawbacks of US imaging is its difficulty in distinguishing tissues that have similar acoustic properties, thereby leading to diagnostic inaccuracies [23].

Using the same US transducer and DAQ, the PAUS technique synergistically combines the advantages of both PA and US imaging modalities [24,25]. Consequently, PAUS imaging offers concurrent functional and anatomical information by acquiring PA and US signals simultaneously at each lateral resolution [26]. Several studies have been published, which show the PAUS’s effectiveness in preclinical animal applications [23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Utilizing the PAUS technique, accurate data are obtained, which are used for clinical diagnostic and therapy-monitoring purposes [42]. Extensive research has highlighted the broad clinical potential of PAUS imaging, and these applications have been comprehensively reviewed [43,44]. They are categorized into some groups, including healthy tissue [45,46,47], tumor and metastasis [48,49,50,51,52,53], bones and joints [54,55], cardiovascular [56,57,58,59], thyroid [60], breast [61,62,63], skin [64,65], extremities [66], large blood vessels [67], prostate [68,69], placenta [70,71], bowels [72,73,74], periodontal health [75], and spine in human cadavers [76].

Despite these promising applications, developing PAUS systems remains challenging for both research and commercial deployment. Several commercial PAUS systems have been used for preclinical purposes, such as the iU22 Philips Healthcare [77], VevoLAZR series—FujiFilm VisualSonics [78], MSOT Acuity series—iThera Medical [79], and Vantage series—Verasonics [69]. These systems enable PAUS imaging without the need for additional hardware or software modifications. However, their widespread adoption is limited by high system costs.

In academic research, PAUS system development has focused on improving image quality, extending the ROI, and reducing scanning time. Image quality depends on the spatial resolution of the PAUS probe, which is optimized through the integration of optical and acoustic components. Probes are typically designed using single elements, linear arrays, or customized US transducers. In addition, advanced image processing algorithms are required to further enhance image quality. Accordingly, this review categorizes PAUS probe designs based on single-focused elements, linear arrays, and customized transducers.

To extend the ROI and reduce scanning time, the PAUS system was developed by exploiting the motions of some mechanisms. The PAUS probe is attached to the movement part of the PAUS system, which is controlled to perform the motion in one-dimensional (1D) or two-dimensional (2D) directions. Linear array-based PAUS systems can achieve B-scan imaging without mechanical motion, whereas systems employing single focused element transducers require 1D scanning. Consequently, 3D imaging is obtained through 1D motion for linear arrays and 2D motion for single-element transducers. The ROI can be expanded by increasing the scanning range, while scanning time is minimized by maximizing the scanning speed. Technically, the scanning speed is determined by the pulse repetition rate (PRR) of the laser function generator, pulser/receiver (P/R), and motion speed of the PAUS system. In that case, PAUS systems are typically designed to operate at the highest feasible scanning speed.

This review will focus on the current development of PAUS probes and systems that can provide an acceptable image quality with a suitable ROI in a short time. These specifications need to be optimized for diagnostic decision-making. The PAUS principle and signal processing are presented, which are used to address the design technologies of PAUS probes and systems. These design technologies are shown comprehensively and summarized systematically. The pros and cons of each design version are discussed. Based on the discussion, future work for developing PAUS probes and systems is proposed to enhance their performance in both preclinical and clinical applications.

The review is organized as follows. The PAUS principle and signal processing are expressed in Section 2. The design of the PAUS probe and scanning mechanism of the PAUS system are summarized in Section 3 and Section 4, respectively. Section 5 presents the summary and future perspectives for the development of the PAUS probe and system.

2. PAUS Principle and Signal Processing

2.1. PAUS Principle

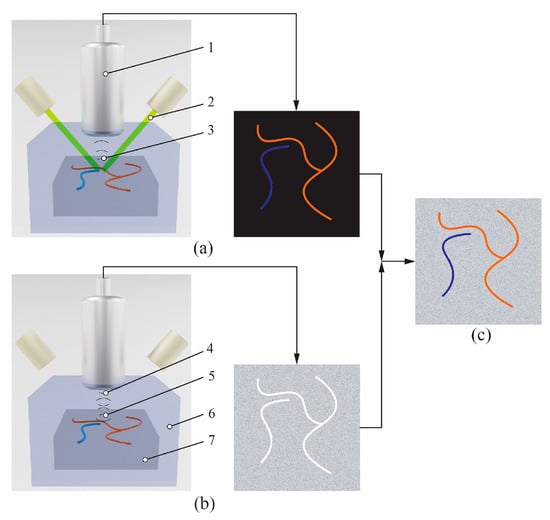

PAUS imaging is a hybrid modality that integrates the principles of PA and US imaging to provide complementary functional and anatomical information of tissue. Figure 1 shows the PAUS principle. A laser beam generated by a laser source propagates to the tissue sample, where specific tissue components such as hemoglobin, melanin, lipids, and other chromophores absorb the light [50,80]. The absorbance process causes the temperature increase, which leads to thermoelastic expansion, resulting in US wave generation. A US transducer is used to collect these US waves to draw a PA image, as shown in Figure 1a. Based on the probe characteristics, such as transducer bandwidth, PA imaging offers high spatial resolution, which can illustrate the functional and molecular information [57,81].

Figure 1.

PAUS principle: (a) PA image, (b) US image, (c) overlaid PAUS image. 1—US transducer, 2—laser beam, 3—US waves generated by the PA effect, 4—US waves emitted from the transducer, 5—reflected US waves, 6—US propagation environment, 7—tissue sample.

Simultaneously, the same US transducer and pulsed radio frequency (P/R) are employed to emit and receive ultrasound waves that propagate through the tissue. According to the different properties of the sample structure, there are several US waves reflected off that are echo signals. The transducer captures these echo signals to generate a conventional US image, as shown in Figure 1b. The US image illustrates the structure information of the tissue based on the difference magnitude of reflected signals and the coherence summation during the image reconstruction [82,83]. During the scanning process, a coupling medium, such as US gel or deionized water, is employed between the transducer and tissue to reduce reflection, which enables better resolution of the resulting images [84].

The combined PA and US images are overlaid to produce the PAUS image, enabling co-registered visualization of optical absorption and acoustic properties, as shown in Figure 1c [85]. During the scanning process, both PA and US data are collected alternatively at each lateral position using the same data acquisition system (DAQ). This integrated approach allows for the concurrent visualization of vascular structures and tissue composition, providing both composition and structural insights [85,86].

2.2. PAUS Signal Processing

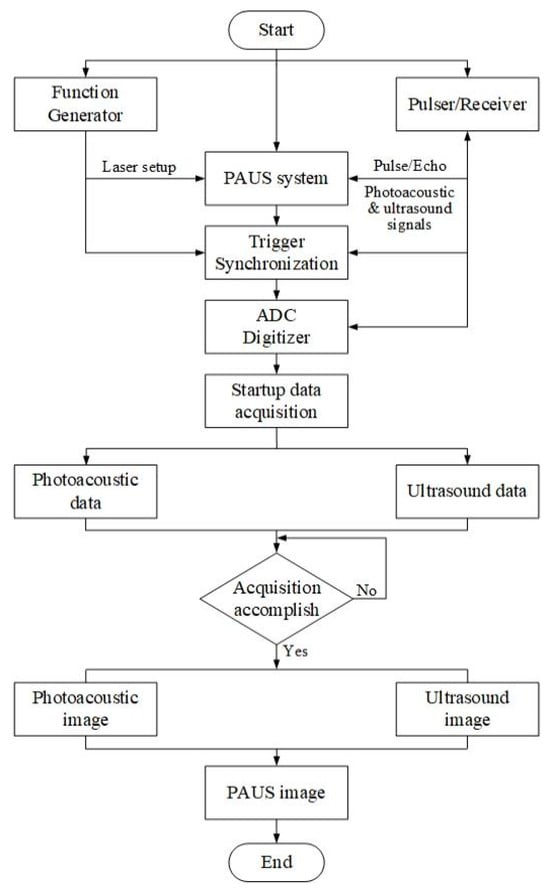

Figure 2 shows the flowchart of PAUS signal processing that uses a DAQ system to collect data and generate an image using image algorithm reconstruction. A function generator is used to create a trigger pulse for a short-pulsed laser that is connected to the PAUS probe and trigger synchronization. In US mode, a P/R is implemented to send an electric signal to the US transducer, thereby emitting US waves to the sample. Both PA and US signals are gathered by the same P/R that is connected to an analog–digital converter (ADC) digitizer. The trigger signals from the function generator and the P/R are synchronized with the encoder of the PAUS scanning system, allowing data acquisition at each lateral scanning position. Data collection is initiated simultaneously with probe scanning, and the PA and US signals are sequentially stored as separate datasets according to their time-of-flight responses until the acquisition is completed. The PA and US images are reconstructed using algorithms such as time domain, delay and sum, and time reversal [87,88,89,90]. Finally, the PAUS image is generated by co-registering and fusing the reconstructed PA and US images.

Figure 2.

The flowchart of PAUS signal processing.

3. Design of PAUS Probe

According to the PAUS principle, a probe is designed by integrating optical and acoustic components to simultaneously acquire PA and US signals. Optical fibers and focusing lenses are employed to deliver pulsed laser illumination to the target tissue, while ultrasound (US) transducers and, in some designs, acoustic mirrors are used for signal detection and propagation [26,78,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. These components are arranged and fixed within a dedicated housing, whose geometry and dimensions are primarily determined by the size and configuration of the US transducer. The US transducer can be either a single element [26,99,100,102,103,105] or an array transducer [78,91,92,93,94,95,97,98,101,104]. The locations of the lens and US transducer in the housing part can be adjusted to make the focal zone, thereby improving the resolution of the PAUS probe. Axial resolution is primarily determined by the US transducer’s bandwidth, while lateral resolution depends on the transducer receiver aperture [44,106,107,108]. Based on the data collection arrangement, it can be operated in either optical resolution (OR) or acoustic resolution (AR) modes. In OR mode, the excitation light was focused to define the lateral resolution. In contrast, AR mode relied on acoustic focusing, achieved through either focused or diffused optics, to determine the image resolution. The OR mode is only possible at a relative shallow depth, whereas the AR mode is appropriate for deeper penetration.

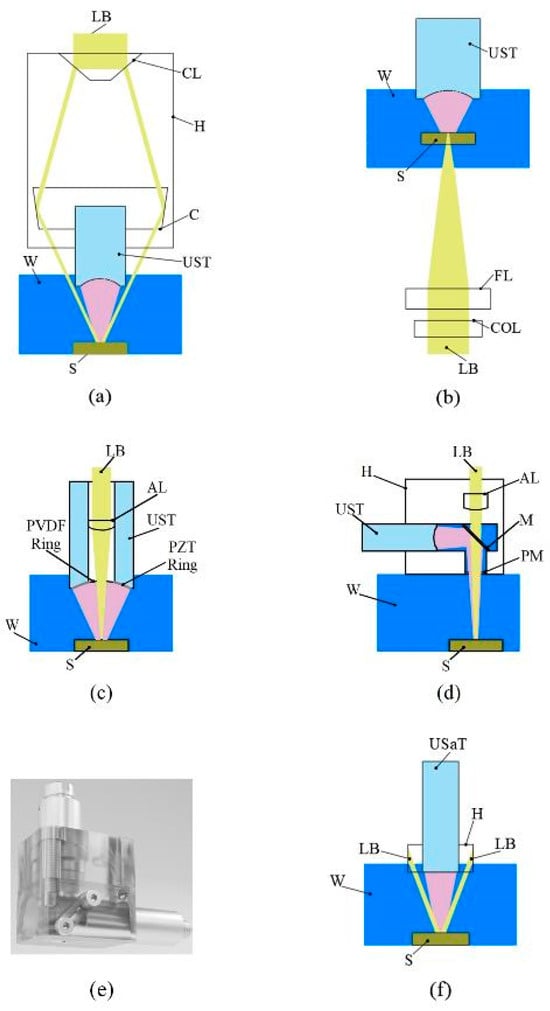

The optical and acoustic components of a PAUS probe can be arranged on either the same side or opposite sides of the sample. Figure 3a shows a schematic of the PAUS probe in reflection type, in which both optical and acoustic components are located on the same side of the tissue. In this concept, the US transducer is put inside the optical condenser [105]. The condenser angle is calculated based on the measured focal length of the US transducer and the acoustic properties of the sample [109], while its size is determined by the transducer dimensions and the selected condenser angle. The housing part of this design is simple and practical for manufacturing and assembly. However, the probe is bulky because of the large size of the condenser component. In transmission type, the optical acoustic components are placed on the opposite side of the sample [92], as shown in Figure 3b. This concept uses the housing part without a condenser, thereby reducing the probe size, but it introduces challenges in achieving precise alignment between the laser beam and the US transducer.

Figure 3.

Schematic of PAUS probes: (a) reflection type, (b) transmission type, (c) customized US transducer type, (d) diagonal reflection type, (e) 3D-rendered design of diagonal reflection type, (f) US array transducer type. AL: aspheric lens, C: condenser, CL: conical lens, COL: correction lens, FL: focusing lens, H: housing part, LB: laser beam, M: mirror, PM: polyethylene membrane, S: sample, USaT: US array transducer, UST: US transducer, W: water.

To overcome the aforementioned limitations, two approaches are presented in published works. First, the US transducer is customized to incorporate optical components directly. A through-hole is created at the center of the transducer, allowing optical elements to be mounted within the backing layer [99]. Two coaxial rings of piezoelectric (PZT) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) materials are fixed on the external housing, as shown in Figure 3c. The PZT ring connects to a pulser/receiver (P/R) for US pulse emission, while the PVDF ring is used to detect both PA and US signals. This probe is very compact, with a length and diameter of 15 mm and 10 mm, respectively. Although this concept is small in size, modifying the transducer structure may adversely affect US performance. The second approach involves developing a housing part, where the laser beam incident and the US transducer are arranged in vertical and horizontal directions, respectively [26,110,111,112,113]. A diagonal prism or mirror slab is implemented in this concept to reflect the PA and US signals to the US transducer that is the diagonal reflection type. Figure 3d shows the schematic of this design, where the housing part is fabricated from acrylic material [26]. An open hole is created on bottom of the housing part to ensure that the laser beam propagates straight without diffraction. This hole is sealed with a polyethylene membrane to maintain the water in the US transducer chamber. The dimension of this probe is 40 mm × 20 mm × 45 mm, as shown in Figure 3e. This configuration simplifies focal alignment but requires high manufacturing precision, particularly in the placement of the focusing lens and US transducer.

In addition, the PAUS probe can be developed using a commercial US array transducer, which is designed for both hand-held and system scanning processes [94,98,114]. In these systems, the optical components are mounted on a housing part fixed to the US array transducer, as shown in Figure 3f. The US array transducers consist of 64 [95], 128 [96], or 256 [78,91] elements, which enable extending the scanning area. Recently, transparent ultrasound transducers have been developed to enable precise coalignment of acoustic and optical pathways while maintaining minimal acoustic coupling. This advancement facilitates real-time multimodal imaging of deep biological tissues [115]. Technically, the frequency of the US array transducer is low, thereby resulting in low resolution of the probe. For instance, the PAUS probe using a 128-element linear array transducer with a frequency of 10 MHz produces US lateral and axial resolutions of 600 μm and 400 μm, respectively [96]. When using a 25 MHz single-focused transducer, these resolutions are about 136 μm and 76 μm [26]. To enhance the spatial resolution of the PAUS probe based on an array transducer, the combination of PA with advanced US methods has been proposed, enabling super-resolution in the reconstructed images [116,117,118]. Furthermore, the image quality depends on the uniformity across various elements of the US array transducer, which leads to a reduction in image quality due to hardware limitations [119].

4. Design the Scanning Mechanism of the PAUS System

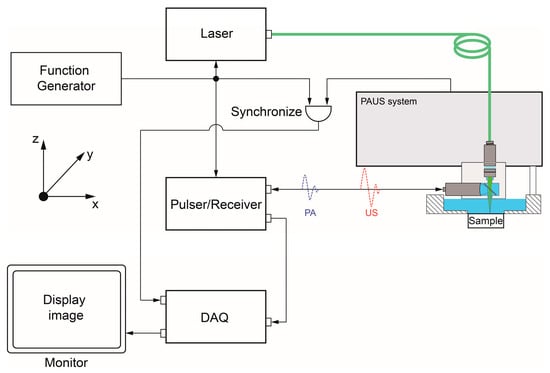

The PAUS probe is attached to the scanning mechanism of the PAUS system that moves in sequence to draw the images. Figure 4 presents the schematic of the PAUS system. The signals of the laser function generator, P/R, and PAUS system are triggered simultaneously to record both PA and US data. Depending on the defined ROI, the PAUS system is configured and controlled to perform the scanning process following three steps. First, the PAUS probe and sample are arranged along the z-axis to align the focal zone. Second, the ROI parameters are specified to determine the data acquisition strategy. Third, the PAUS system conducts a motion to cover the whole ROI. Based on the PAUS probe, the motion of the PAUS system can be implemented in 1D or 2D directions. To conduct these movements, the scanning mechanism of the PAUS system is developed by exploiting the motion of some mechanisms, such as a motion stage, a voice coil, a combination of a slider crank and a ball screw, and a galvo.

Figure 4.

The schematic of the PAUS system.

4.1. PAUS System Motion Based on Motion Stage

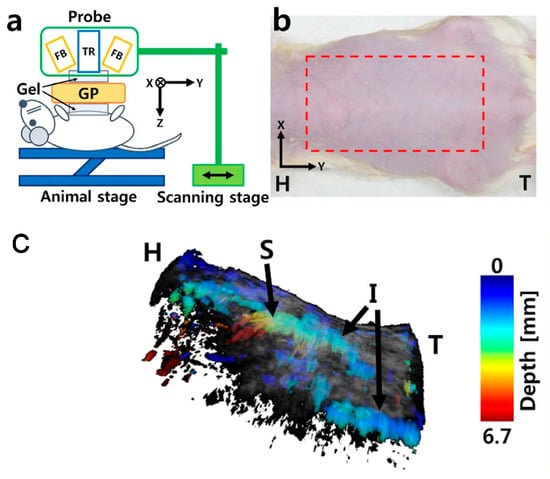

The motion stage is designed to meet the stringent requirements of high precision and compactness, both of which are particularly critical for integration into PAUS systems. The stage facilitates linear movement along one or multiple axes, driven by either traditional motors or brushless linear direct current motors (BLDCMs). The traditional motors can be stepper or servo and are connected to the ball screw mechanism to convert rotational motion to linear motion [101,104,105,120,121,122]. Due to the advantages of simplicity, low-cost, and versatility, this concept is commercialized by McMASTER-Carr [101], Velmex [122], and THORLABS [123]. Figure 5a shows the schematic of the PAUS system using a scanning stage and a probe with an array transducer. During the scanning process, this PAUS system moves in one direction to record a suitable ROI, as shown in Figure 5b. Figure 5c shows the depth-resolved volumetric PAUS image of the rat [104]. The ROI along the x-axis is covered by the PAUS probe equipped with a 128-element ultrasound array, while the scanning stage provides mechanical translation along the y-axis. Using this PAUS system, the human forearm is successfully captured in vivo, as shown in Figure 6. To achieve movement in two directions (x- and y-axes), the system can utilize either two ball screw mechanisms or a combination of a ball screw and a timing belt. Based on the features of the ball screw mechanism, the PAUS system can easily extend the ROI. However, the scanning speed of this design is relatively slow, which results in longer scanning times. For instance, to cover the scanning range of 75 mm, the scanning speed is 2.5 mm/s [104]. The scanning time is around 30 min to image an ROI of 60 mm × 40 mm [105].

Figure 5.

PAUS system using the motion stage: (a) schematic of the PAUS system, (b) photograph of the rat and ROI (the red dashed rectangle), (c) depth-resolved volumetric PAUS image of the rat. H: head, I: intestine, S: stomach, T: tail, FB: fiber bundle, TR: US array transducer, GP: gelatin pad [104].

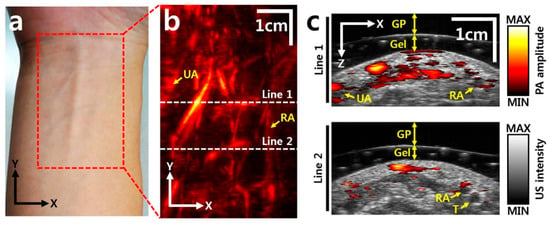

Figure 6.

In vivo images of a human forearm: (a) photograph of a human right forearm, (b) PA image, (c) cross-sectional overlaid PAUS images at the two white dashed lines in (b). UA: ulnar artery, RA: radial artery, T: tendon, Gel: gelatin, GP: gelatin pad [104].

Nowadays, to address the speed limitations, the motion stage is designed by exploiting the BLDCM. In contrast to traditional motor-driven systems, BLDCMs directly convert electrical energy into linear motion, thereby minimizing mechanical transmission components. Technically, this motor contains fixed permanent magnets and windings mounted on the guideway, enabling smooth, quiet, and high-speed motion based on electromagnetic actuation principles. High-resolution encoders are used to precisely control movement. THORLAB has developed a commercial type of this motion stage (model: M150XY/M) that provides 150 mm of travel in both the x- and y-axes at maximum speeds of 170 mm/s and 230 mm/s, respectively [124]. This type of motion stage provides significant advantages in terms of precision, speed, reliability, and reduced maintenance requirements; however, its major limitation remains the high cost, which is approximately USD 10,000 for the M150XY/M model.

4.2. PAUS System Motion Based on a Voice Coil Mechanism

The voice coil mechanism is a commonly used electromechanical device that operates based on the fundamental principles of electromagnetism. The key component is a wire cylinder (voice coil) that is assembled to a permanent magnet with a defined magnetic gap. When an electrical current passes through the coil, it generates a magnetic field that interacts with the static magnetic field of the permanent magnet, producing a force that drives the coil in a linear motion. Owing to its fast response, high precision, and friction-free operation, the voice coil actuator is particularly suitable for implementing fast-scanning modules in PAUS systems. In this concept, the PAUS probe is attached to the voice coil to enable rapid scanning along one axis, while the orthogonal axis is driven more slowly using a ball screw or timing belt mechanism.

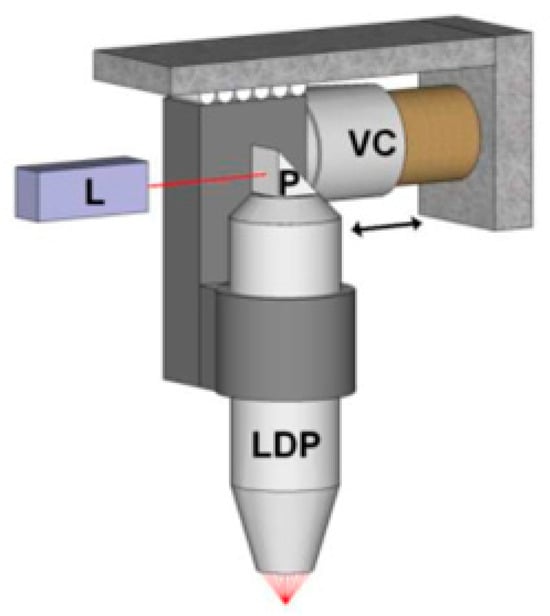

Figure 7 shows the PAUS system using the voice coil stage (VSC-10-023-BS-01, from H2W Technologies, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) that is driven by the motor controller (Elmo Harmonica HAR 5/60) [103]. The system achieves a scanning range of 9 mm at a frame rate of 20 fps, corresponding to an average scanning speed of approximately 1800 mm/s. The higher speed can be achieved by reducing the scanning ranges. Using the PAUS system with the voice coil stage, a human finger is successfully captured with in vivo imaging, as shown in Figure 8 [103].

Figure 7.

PAUS system using a voice coil mechanism. L: incident light from a laser, P: prism, VC: voice coil, LDP: light delivery probe. Reprinted with permission from [103]; © Optical Society of America.

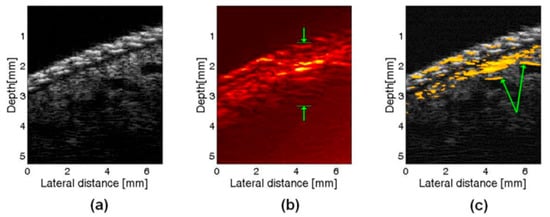

Figure 8.

In vivo images of a a human finger: (a) US image, (b) PA image, (c) PAUS image, arrows indicate where large vessels are seen only in part in PA data. Reprinted with permission from [103]; © Optical Society of America.

The key advantages of the voice coil mechanism are simple and high accuracy because it operates without complex linkages and friction. However, expanding the scanning range and managing the vibration problem remain challenging. Key design parameters include the number of coil turns, coil geometry and material, force generation capability, and thermal performance. Increasing the coil length or diameter to expand the scanning range inevitably raises the coil mass, which can adversely affect force generation and dynamic response. During the scanning process, the coil undergoes a reciprocating motion, which produces a shaking force that causes the vibration problem. Consequently, the PAUS probe and coil are designed to minimize their masses to reduce the shaking force. Additionally, the heat dissipation requirements are essential for maintaining the system’s efficiency. Therefore, the overall system design requires a careful balance among thermal management, mechanical stability, and actuation performance through optimized material selection and dimensional design.

4.3. PAUS System Motion Based on a Combination of Slider Crank and Ball Screw Mechanisms

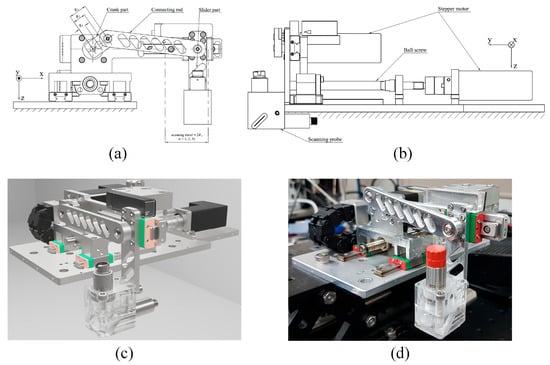

In this design, the PAUS system is developed by a combination of slider crank and ball screw mechanisms, which implement two linear motions along the x- and y-axes, respectively. By converting pure rotational motion from the crank part to pure linear motion of the slider part, the slider crank mechanism conducts a fast linear motion along the x-axis. Meanwhile, the ball screw mechanism provides a comparatively slow and precise linear motion along the y-axis for stepwise raster scanning. Figure 9 shows the PAUS system using a combination of slider crank and ball screw mechanisms. The slider crank mechanism consists of three main parts: a crank, a connecting rod, and a slider. The crank is directly coupled to the motor shaft to generate rotational motion, which is transmitted through the connecting rod to drive the linear motion of the slider. One complete revolution of the crank produces a full reciprocating cycle of the slider, corresponding to two linear strokes along the x-axis. The PAUS probe is attached to the slider part. The travel and velocity of the system along the x-axis are fixed by crank radius and crank rotational speed, respectively. Although this configuration offers a simple, high-speed, and cost-effective solution, it is limited to imaging a specific ROI. Adjusting the scanning characteristics for a different ROI requires redesigning the slider crank mechanism with new geometric parameters.

Figure 9.

PAUS system using a combination of slider crank and ball screw mechanisms: (a) 2D front view, (b) 2D left side view, (c) 3D rendered design, (d) photograph of the entire system [26].

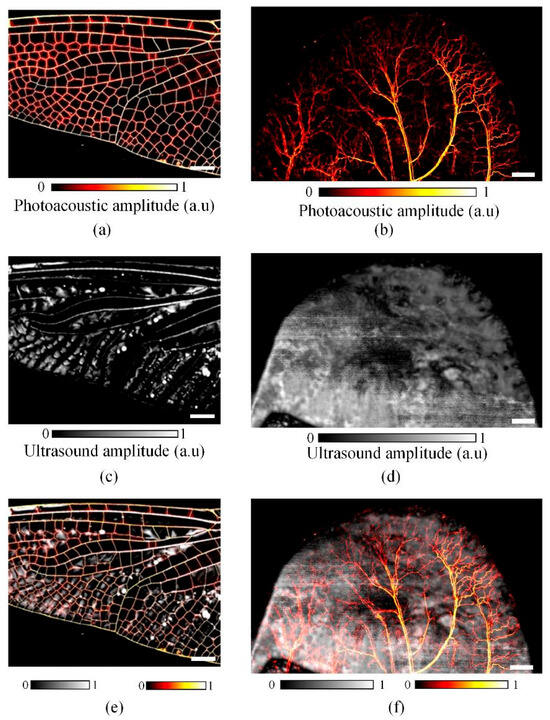

Figure 10 presents the result images of dragonfly wings and mouse ear samples that are obtained using this PAUS system. The ROIs for the dragonfly wing and mouse ear were 18 mm × 14 mm and 26 mm × 16 mm, respectively. For the dragonfly wing, the crank radius and speed were set to 9 mm and 780 rpm (revolutions per minute), whereas for the larger mouse ear ROI, a crank radius of 13 mm and a rotational speed of 540 rpm were used. With a step size of 10 μm, the scanning times were 54 s and 89 s for acquiring the US images of the dragonfly wing and mouse ear, respectively [26]. Figure 10a,b show the PA images of the two samples, while Figure 10c,d illustrate the corresponding US images. The final PAUS images were generated by spatially co-registering and merging the PA and US images at each lateral scanning position, as shown in Figure 10e,f. Due to the inherent characteristics of the slider crank mechanism, increasing the crank radius to enlarge the ROI necessitates a reduction in rotational speed, which in turn decreases scanning speed and increases total acquisition time. To maintain a high scanning speed while expanding the ROI, two identical PAUS probes can be mounted on a single slider with a spacing equal to twice the crank radius [125]. Alternatively, a double slider crank mechanism has been introduced, in which two slider assemblies are arranged to achieve a total travel distance twice that of a conventional single mechanism [126]. In addition, high-speed operation may induce mechanical vibrations that degrade image quality. In that case, a counterweight is attached to the crank part to solve the vibration problem [127].

Figure 10.

Dragonfly wing and mouse ear imaging: (a,b) PA images; (c,d) US images; (e,f) PAUS images [26].

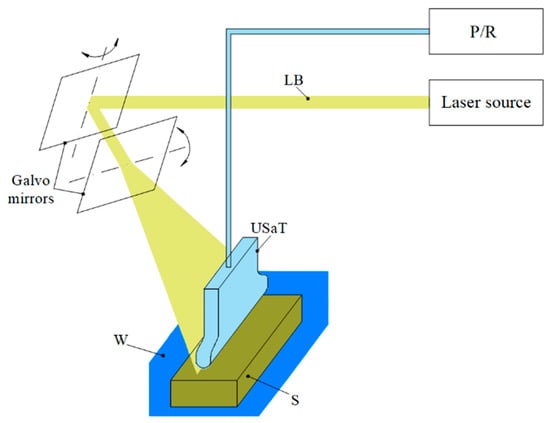

4.4. PAUS System Motion Based on the Galvo Mechanism

The galvo mechanism uses lightweight mirrors mounted on the galvanometers, which are controlled to rotate around a pivot point. The main components are the motor and detector. The mirror is affixed to the motor shaft, and its rotational motion is governed by electromagnetic principles. During its operation, the electric current passes through the coil, thereby generating the magnetic field. The rotation motion of the mirror is produced by the interaction between the magnetic field and the magnetic assembly. The detector is used to provide feedback on the mirror angular position, enabling closed-loop control for smooth and precise operation. By regulating the mirror motion, the galvo mechanism facilitates movement in 1D and 2D directions.

In the PAUS application, the galvo system is implemented to steer the laser beam [128,129]. Figure 11 shows the schematic of the PAUS system using the galvo mechanism. The laser beam is propagated to the mirror, which is adjusted through its angular movement to scan the ROI. In this version, the PAUS probe developed based on a US linear array transducer is used to receive the PA signal produced at a high frame rate. Using the galvo PAUS system, an ROI of 28 mm × 28 mm has been successfully imaged at 30 fps [128]. The advantages of the galvo mechanism include low inertial mass and the absence of mechanical contact between moving components, which make it particularly suitable for high-speed and high-precision imaging applications with enhanced durability and reliability. However, there are some limitations that need to be addressed in future studies. First, achievable ROI is relatively small and difficult to expand due to the limited angular range of the mirror. Second, the mirror steers the laser beam to various axial depths, resulting in misalignment between laser and ultrasound, which affects image quality. Third, the captured images must be reconstructed to correct the distortions caused by the scanning patterns, which necessitates the optimization of the image processing algorithm, particularly in real-time scanning process.

Figure 11.

PAUS system using the galvo mechanism.

5. Summary and Future Perspectives

In this review, the design of dual-modal PAUS probes and systems is systematically presented and discussed. Numerous studies have demonstrated the potential of PAUS technology in both preclinical small-animal imaging and clinical human applications. This review aims to present the current development of PAUS technology in order to enhance its capabilities. Critical parameters such as scanning time, ROI, and image quality require continued improvement to support diagnostic decision-making. The fundamental principles of PAUS imaging and associated signal processing techniques are first introduced, as they form the basis for the design of PAUS probes and systems. The PAUS probe is developed using either a single-element or a linear array US transducer, each offering distinct spatial resolutions and thus influencing overall image quality. The characteristics of the existing PAUS probe are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of various PAUS probes.

To extend the ROI and increase the scanning speed, the PAUS system is developed by leveraging the advantage motion of some mechanisms. Current systems support 1D and 2D movements enabled by motion stages, voice coils, slider crank and ball screw combinations, and galvo mechanisms. A comparative overview of the advantages and limitations of these PAUS system designs is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of various PAUS systems.

According to the summary of the PAUS probes and systems, several approaches for improvement should be addressed in future studies as follows:

- (1)

- Improve image reconstruction tools to achieve uniform contrast across elements of linear array PAUS probes and synchronize signal-to-noise ratios of all elements to enhance overall image quality, which can be achieved by enabling the signal amplitude adjustment for each element of the linear array transducer.

- (2)

- Optimize image processing algorithms to handle the distortion problems when using the linear array PAUS probe to record images in real-time, thereby facilitating its broader adoption in clinical diagnosis and interventional applications. The distortion problems can be solved by adding the artificial intelligence (AI) module to the image processing framework.

- (3)

- Develop a linear array PAUS probe applied to the PAUS system utilizing a combination of slider crank and ball screw mechanisms to significantly reduce the scanning time that supports timely decision-making in both preclinical and clinical studies.

- (4)

- Design a PAUS system capable of simultaneous three-axis motion to scan the 3D sample without requiring a tillable, such as the foot and forearms. These movements can be controlled by a combination of motions of some mechanisms, such as a ball screw, a timing belt, and a slider crank.

- (5)

- Develop portable, compact, and high-performance PAUS systems suitable for widespread use in educational and scientific purposes by customizing the shape, size, and functional capabilities of all PAUS system components.

- (6)

- Integrate PAUS systems with deep learning and artificial intelligence frameworks to significantly enhance image processing capabilities and expand diagnostic potential for human diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.H.P.; methodology, V.H.P.; investigation, V.H.P.; data curation, V.H.P. and T.N.V.; writing—original draft preparation, V.H.P.; writing—review and editing, V.H.P. and T.N.V.; visualization, V.H.P.; supervision, V.H.P. and T.N.V.; project administration, V.H.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding support for this study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ntziachristos, V. Going deeper than microscopy: The optical imaging frontier in biology. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Huang, P. Recent advances in photoacoustic imaging for deep-tissue biomedical applications. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Luo, D.; Chitgupi, U.; Geng, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Lovell, J.F.; Xia, J. Deep tissue photoacoustic computed tomography with a fast and compact laser system. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 8, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic tomography: Principles and advances. Electromagn. Waves 2014, 147, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Favazza, C.; Wang, L.V. In vivo photoacoustic tomography of chemicals: High-resolution functional and molecular optical imaging at new depths. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2756–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic microscopy. Laser Photonics Rev. 2013, 7, 758–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmacharya, M.B.; Sultan, L.R.; Sehgal, C.M. Photoacoustic monitoring of oxygenation changes induced by therapeutic ultrasound in murine hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Qian, W.; Yang, L.; Xie, H.; Jiang, H. In vivo evaluation of a miniaturized fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) endoscope for breast cancer detection using targeted Nanoprobes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, L.V. Small-animal whole-body photoacoustic tomography: A review. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 61, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, L.; Ma, C.; Lin, L.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.; Maslov, K.; Zhang, R.; Chen, W.; Shi, J. Single-impulse panoramic photoacoustic computed tomography of small-animal whole-body dynamics at high spatiotemporal resolution. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalva, S.K.; Dean-Ben, X.L.; Razansky, D. Single-sweep volumetric optoacoustic tomography of whole mice. Photonics Res. 2021, 9, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kye, H.; Song, Y.; Ninjbadgar, T.; Kim, C.; Kim, J. Whole-body photoacoustic imaging techniques for preclinical small animal studies. Sensors 2022, 22, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Ntziachristos, V. In-vivo handheld optoacoustic tomography of the human thyroid. Photoacoustics 2016, 4, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H. Convolutional neural network for breast cancer diagnosis using diffuse optical tomography. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2019, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, A.; Masthoff, M.; Claussen, J.; Ford, S.J.; Roll, W.; Burg, M.; Barth, P.J.; Heindel, W.; Schäfers, M.; Eisenblätter, M. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography of the human breast: Characterisation of healthy tissue and malignant lesions using a hybrid ultrasound-optoacoustic approach. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, C.; Kim, J. Review on multispectral photoacoustic analysis of cancer: Thyroid and breast. Metabolites 2022, 12, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, A.B.E.; Balasundaram, G.; Moothanchery, M.; Dinish, U.; Bi, R.; Ntziachristos, V.; Olivo, M. A review of clinical photoacoustic imaging: Current and future trends. Photoacoustics 2019, 16, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, I.; Kim, J.; Schneider, M.K.; Hyun, D.; Zlitni, A.; Hopper, S.M.; Klap, T.; Sonn, G.A.; Dahl, J.J.; Kim, C. Superiorized photo-acoustic non-negative reconstruction (SPANNER) for clinical photoacoustic imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 40, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, V.; Mazzotta, G.; Pignatelli, V.; Bufi, E.; D’Angelo, A.; Conti, M.; Panico, C.; Fiorentino, V.; Pierconti, F.; Kilburn-Toppin, F. Beyond N staging in breast cancer: Importance of MRI and ultrasound-based imaging. Cancers 2022, 14, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, I.; Ciurea, A.I.; Ciortea, C.A.; Ștefan, P.A.; Ciule, L.D.; Lupean, R.A.; Dudea, S.M. Radiomic signatures Derived from hybrid contrast-enhanced ultrasound images (CEUS) for the assessment of Histological characteristics of breast cancer: A pilot study. Cancers 2022, 14, 3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Huang, S.-W.; Jin, Y.; Seo, C.H.; Huang, L.; Eary, J.F.; Gao, X.; O’Donnell, M. Integration of photoacoustic, ultrasound, and magnetomotive system. In Proceedings of the Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2010, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–26 January 2010; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, P.N. Ultrasound imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, R83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choi, W.; Kim, C.; Park, B.; Kim, J. Review on ultrasound-guided photoacoustic imaging for complementary analyses of biological systems in vivo. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, R.; Sahin, O.; Emelianov, S. Ultrasound-guided photoacoustic imaging: Current state and future development. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2014, 61, 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Sharma, A.; Rajendran, P.; Pramanik, M. Another decade of photoacoustic imaging. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 05TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.H.; Nguyen, V.T.; Ly, C.D.; Choi, J.; Park, S.; Mondal, S.; Vo, T.H.; Lim, H.G.; Oh, J. Development of fast photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging system based on slider-crank scanner for small animals and humans study. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 206, 117939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Koehler, R.C.; Graham, E.M.; Boctor, E.M. Photoacoustic assessment of the fetal brain and placenta as a method of non-invasive antepartum and intrapartum monitoring. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 347, 113898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadkhah, A.; Jiao, S. Integrating photoacoustic microscopy with other imaging technologies for multimodal imaging. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R.K.; Hallam, K.A.; Donnelly, E.M.; Emelianov, S.Y. Photoacoustic imaging of gold nanorods in the brain delivered via microbubble-assisted focused ultrasound: A tool for in vivo molecular neuroimaging. Laser Phys. Lett. 2019, 16, 025603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumani, D.S.; Sun, I.-C.; Emelianov, S.Y. Ultrasound-guided immunofunctional photoacoustic imaging for diagnosis of lymph node metastases. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 11649–11659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaleyeva, L.M.; Brosnihan, K.B.; Smith, L.M.; Sun, Y. Preclinical Ultrasound-Guided Photoacoustic Imaging of the Placenta in Normal and Pathologic Pregnancy. Mol. Imaging 2018, 17, 1536012118802721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Chang, J.H.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.; Wilson, B.C.; Song, T.-K. Real-time sentinel lymph node biopsy guidance using combined ultrasound, photoacoustic, fluorescence imaging: In vivo proof-of-principle and validation with nodal obstruction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Li, H.; Merkulov, A.; Kumavor, P.; Vavadi, H.; Sanders, M.; Kueck, A.; Brewer, M.; Zhu, Q. Coregistered photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging and classification of ovarian cancer: Ex vivo and in vivo studies. J. Biomed. Opt. 2016, 21, 046006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallidi, S.; Kim, S.; Karpiouk, A.; Joshi, P.P.; Sokolov, K.; Emelianov, S. Visualization of molecular composition and functionality of cancer cells using nanoparticle-augmented ultrasound-guided photoacoustics. Photoacoustics 2015, 3, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, G.P.; Emelianov, S.Y. Label-free detection of lymph node metastases with US-guided functional photoacoustic imaging. Radiology 2015, 277, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luke, G.P.; Myers, J.N.; Emelianov, S.Y.; Sokolov, K.V. Sentinel lymph node biopsy revisited: Ultrasound-guided photoacoustic detection of micrometastases using molecularly targeted plasmonic nanosensors. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5397–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, M.; Zhao, Y.; Nania, S.; Norberg, K.J.; Verbeke, C.S.; Englert, B.; Kuiper, R.V.; Bergström, Å.; Hassan, M.; Neesse, A. Real-time assessment of tissue hypoxia in vivo with combined photoacoustics and high-frequency ultrasound. Theranostics 2014, 4, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpiouk, A.B.; Wang, B.; Amirian, J.; Smalling, R.W.; Emelianov, S.Y. Feasibility of in vivo intravascular photoacoustic imaging using integrated ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging catheter. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 096008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizinga, P.; Mastik, F.; Koeze, D.; Jong, N.D.; Van Der Steen, A.F.; Soest, G.V. Ultrasound-guided photoacoustic image reconstruction: Image completion and boundary suppression. J. Biomed. Opt. 2013, 18, 096017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.Y.; Ricles, L.M.; Suggs, L.J.; Emelianov, S.Y. In vivo ultrasound and photoacoustic monitoring of mesenchymal stem cells labeled with gold nanotracers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Guo, P.; Gamelin, J.; Yan, S.; Sanders, M.M.; Brewer, M.; Zhu, Q. Coregistered three-dimensional ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging system for ovarian tissue characterization. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009, 14, 054014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallidi, S.; Watanabe, K.; Timerman, D.; Schoenfeld, D.; Hasan, T. Prediction of tumor recurrence and therapy monitoring using ultrasound-guided photoacoustic imaging. Theranostics 2015, 5, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Guo, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Jiang, S.; Wu, D.; Jiang, H. Clinical photoacoustic/ultrasound dual-modal imaging: Current status and future trends. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1036621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, T.; Qiu, H.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zuo, C.; Ma, H. Simultaneous photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging: A review. Ultrasonics 2024, 139, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennes, O.A.; van Netten, J.J.; Slart, R.H.; Steenbergen, W. Novel optical techniques for imaging microcirculation in the diabetic foot. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 1304–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Chang, J.H. Multimodal photoacoustic imaging as a tool for sentinel lymph node identification and biopsy guidance. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2018, 8, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Zhou, W.; Matthews, T.P.; Appleton, C.M.; Anastasio, M.A. Generation of anatomically realistic numerical phantoms for photoacoustic and ultrasonic breast imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 041015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavierselvan, M.; Singh, M.K.A.; Mallidi, S. Preclinical cancer imaging using a multispectral LED-based photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging system. In Proceedings of the Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2021, Online, 6–11 March 2021; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; p. 116422G. [Google Scholar]

- Shiina, T.; Toi, M.; Yagi, T. Development and clinical translation of photoacoustic mammography. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2018, 8, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tang, Y.; Yao, J. Photoacoustic tomography of blood oxygenation: A mini review. Photoacoustics 2018, 10, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhao, L.; He, X.; Su, N.; Zhao, C.; Tang, H.; Hong, T.; Li, W.; Yang, F.; Lin, L. Photoacoustic/ultrasound dual imaging of human thyroid cancers: An initial clinical study. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 3449–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuschler, E.I.; Butler, R.; Young, C.A.; Barke, L.D.; Bertrand, M.L.; Böhm-Vélez, M.; Destounis, S.; Donlan, P.; Grobmyer, S.R.; Katzen, J. A pivotal study of optoacoustic imaging to diagnose benign and malignant breast masses: A new evaluation tool for radiologists. Radiology 2018, 287, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Uribe, A.; Erpelding, T.N.; Krumholz, A.; Ke, H.; Maslov, K.; Appleton, C.; Margenthaler, J.A.; Wang, L.V. Dual-modality photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging system for noninvasive sentinel lymph node detection in patients with breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Du, S.; Ta, D.; Cheng, Q.; Yuan, J. Ultrasound-guided detection and segmentation of photoacoustic signals from bone tissue in vivo. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, P.J.; Daoudi, K.; Moens, H.J.B.; Steenbergen, W. Feasibility of photoacoustic/ultrasound imaging of synovitis in finger joints using a point-of-care system. Photoacoustics 2017, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zeng, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, S. Emerging contrast agents for multispectral optoacoustic imaging and their biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 7924–7940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Awasthi, N.; Rad, N.M.; Pluim, J.P.; Lopata, R.G. Advanced ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging in cardiology. Sensors 2021, 21, 7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlas, A.; Masthoff, M.; Kallmayer, M.; Helfen, A.; Bariotakis, M.; Fasoula, N.A.; Schäfers, M.; Seidensticker, M.; Eckstein, H.-H.; Ntziachristos, V. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography of peripheral arterial disease based on muscle hemoglobin gradients—A pilot clinical study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlas, A.; Kallmayer, M.; Bariotakis, M.; Fasoula, N.-A.; Liapis, E.; Hyafil, F.; Pelisek, J.; Wildgruber, M.; Eckstein, H.-H.; Ntziachristos, V. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography of lipid and hemoglobin contrast in human carotid atherosclerosis. Photoacoustics 2021, 23, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, B.; Ha, J.; Steinberg, I.; Hooper, S.M.; Jeong, C.; Park, E.-Y.; Choi, W.; Liang, T.; Bae, J.S. Multiparametric photoacoustic analysis of human thyroid cancers in vivo. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 4849–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalev, J.; Herzog, D.; Clingman, B.; Miller, T.; Kist, K.; Dornbluth, N.C.; McCorvey, B.M.; Otto, P.; Ermilov, S.; Nadvoretsky, V. Clinical feasibility study of combined optoacoustic and ultrasonic imaging modality providing coregistered functional and anatomical maps of breast tumors. In Proceedings of the Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2012, San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–24 January 2012; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2012; pp. 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, Y.; Balasundaram, G.; Moothanchery, M.; Attia, A.; Li, X.; Lim, H.Q.; Burton, N.C.; Qiu, Y.; Putti, T.C.; Chan, C.W. Ultrasound guided optoacoustic tomography in assessment of tumor margins for lumpectomies. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 13, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraevsky, A.; Clingman, B.; Zalev, J.; Stavros, A.; Yang, W.; Parikh, J. Clinical optoacoustic imaging combined with ultrasound for coregistered functional and anatomical mapping of breast tumors. Photoacoustics 2018, 12, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Bang, C.; Lee, C.; Han, J.; Choi, W.; Kim, J.; Park, G.; Rhie, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, C. 3D wide-field multispectral photoacoustic imaging of human melanomas in vivo: A pilot study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 35, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J.; He, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, S. A tumor microenvironment–induced absorption red-shifted polymer nanoparticle for simultaneously activated photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabe3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeri, M.; Bost, W.; Sénégond, N.; Tretbar, S.; Fournelle, M. Hybrid photoacoustic/ultrasound tomograph for real-time finger imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 2200–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Jansen, K.; van der Steen, A.F.; van Soest, G. Specific imaging of atherosclerotic plaque lipids with two-wavelength intravascular photoacoustics. Biomed. Opt. Express 2015, 6, 3276–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Johnstonbaugh, K.; Clark, J.Y.; Raman, J.D.; Wang, X.; Kothapalli, S.-R. Design, development, and multi-characterization of an integrated clinical transrectal ultrasound and photoacoustic device for human prostate imaging. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothapalli, S.-R.; Sonn, G.A.; Choe, J.W.; Nikoozadeh, A.; Bhuyan, A.; Park, K.K.; Cristman, P.; Fan, R.; Moini, A.; Lee, B.C. Simultaneous transrectal ultrasound and photoacoustic human prostate imaging. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneas, E.; Aughwane, R.; Huynh, N.; Xia, W.; Ansari, R.; Kuniyil Ajith Singh, M.; Hutchinson, J.C.; Sebire, N.J.; Arthurs, O.J.; Deprest, J. Photoacoustic imaging of the human placental vasculature. J. Biophotonics 2020, 13, e201900167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Maneas, E.; Huynh, N.T.; Singh, M.K.A.; Brown, N.M.; Ourselin, S.; Gilbert-Kawai, E.; West, S.J.; Desjardins, A.E. Imaging of human peripheral blood vessels during cuff occlusion with a compact LED-based photoacoustic and ultrasound system. In Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2019; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Amidi, E.; Chapman, W.C., Jr.; Nandy, S.; Mostafa, A.; Abdelal, H.; Alipour, Z.; Chatterjee, D.; Mutch, M.; Zhu, Q. Co-registered photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging of human colorectal cancer. J. Biomed. Opt. 2019, 24, 121913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Chapman, W., Jr.; Rao, B.; Nandy, S.; Chen, R.; Rais, R.; Gonzalez, I.; Zhou, Q.; Chatterjee, D.; Mutch, M. Feasibility of co-registered ultrasound and acoustic-resolution photoacoustic imaging of human colorectal cancer. Biomed. Opt. Express 2018, 9, 5159–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knieling, F.; Neufert, C.; Hartmann, A.; Claussen, J.; Urich, A.; Egger, C.; Vetter, M.; Fischer, S.; Pfeifer, L.; Hagel, A. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography for assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1292–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarzadeh, M.; Moore, C.; Golmoghani, E.B.; Mantri, Y.; Hariri, A.; Jorns, A.; Fu, L.; Verweij, M.D.; Orooji, M.; de Jong, N. Motion-compensated noninvasive periodontal health monitoring using handheld and motor-based photoacoustic-ultrasound imaging systems. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 1543–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, E.A.; Jain, A.; Bell, M.A.L. Combined ultrasound and photoacoustic image guidance of spinal pedicle cannulation demonstrated with intact ex vivo specimens. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 68, 2479–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Erpelding, T.N.; Jankovic, L.; Pashley, M.D.; Wang, L.V. Deeply penetrating in vivo photoacoustic imaging using a clinical ultrasound array system. Biomed. Opt. Express 2010, 1, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needles, A.; Heinmiller, A.; Sun, J.; Theodoropoulos, C.; Bates, D.; Hirson, D.; Yin, M.; Foster, F.S. Development and initial application of a fully integrated photoacoustic micro-ultrasound system. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2013, 60, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, J.; Sathirachinda, A.; Gambhir, S.S. A high-affinity, high-stability photoacoustic agent for imaging gastrin-releasing peptide receptor in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3721–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, C.L.; Joshi, P.P.; Emelianov, S.Y. Photoacoustic imaging: A potential tool to detect early indicators of metastasis. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2013, 10, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Wang, L.V. Recent progress in photoacoustic molecular imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2018, 45, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, P.; Martin, K.; Thrush, A. Diagnostic Ultrasound: Physics and Equipment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, T.L. Diagnostic Ultrasound Imaging: Inside Out; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Q.; Wu, M.; Yang, J.; Pan, T.; Zhang, G.; Wu, D.; Jiang, H. A comparative study on water and dry coupling in photoacoustic tomography of the finger joints. J. Innov. Opt. Health Sci. 2020, 13, 2050008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, P. Biomedical photoacoustic imaging. Interface Focus 2011, 1, 602–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, L.V. Photoacoustic imaging in biomedicine. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2006, 77, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ding, L.; Ben, X.L.D.; Razansky, D.; Prakash, J.; Ntziachristos, V. Three-dimensional optoacoustic reconstruction using fast sparse representation. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 979–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paridar, R.; Mozaffarzadeh, M.; Mehrmohammadi, M.; Orooji, M. Photoacoustic image formation based on sparse regularization of minimum variance beamformer. Biomed. Opt. Express 2018, 9, 2544–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matrone, G.; Savoia, A.S.; Caliano, G.; Magenes, G. The delay multiply and sum beamforming algorithm in ultrasound B-mode medical imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2014, 34, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarzadeh, M.; Mahloojifar, A.; Orooji, M.; Adabi, S.; Nasiriavanaki, M. Double-stage delay multiply and sum beamforming algorithm: Application to linear-array photoacoustic imaging. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 65, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merčep, E.; Deán-Ben, X.L.; Razansky, D. Combined pulse-echo ultrasound and multispectral optoacoustic tomography with a multi-segment detector array. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2017, 36, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Erpelding, T.N.; Jankovic, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.V. Performance characterization of an integrated ultrasound, photoacoustic, and thermoacoustic imaging system. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 056010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Kuniyil Ajith Singh, M.; Johnstonbaugh, K.; Han, D.C.; Pameijer, C.R.; Kothapalli, S.-R. Photoacoustic imaging of human vasculature using LED versus laser illumination: A comparison study on tissue phantoms and in vivo humans. Sensors 2021, 21, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlöv, T.; Sheikh, R.; Dahlstrand, U.; Albinsson, J.; Malmsjö, M.; Cinthio, M. Regional motion correction for in vivo photoacoustic imaging in humans using interleaved ultrasound images. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 3312–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederhauser, J.J.; Jaeger, M.; Lemor, R.; Weber, P.; Frenz, M. Combined ultrasound and optoacoustic system for real-time high-contrast vascular imaging in vivo. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2005, 24, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Yang, S. Real-time interleaved photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging for guiding interventional procedures. Appl. Acoust. 2019, 156, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, K.; Van Den Berg, P.; Rabot, O.; Kohl, A.; Tisserand, S.; Brands, P.; Steenbergen, W. Handheld probe integrating laser diode and ultrasound transducer array for ultrasound/photoacoustic dual modality imaging. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 26365–26374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montilla, L.G.; Olafsson, R.; Bauer, D.R.; Witte, R.S. Real-time photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging: A simple solution for clinical ultrasound systems with linear arrays. Phys. Med. Biol. 2012, 58, N1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Ma, H.; Cheng, Z.; Yang, S. Photoacoustic and ultrasound (PAUS) dermoscope with high sensitivity and penetration depth by using a bimorph transducer. J. Biophotonics 2020, 13, e202000145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Shung, K.K.; Chen, Z. Integrated ultrasound and photoacoustic probe for co-registered intravascular imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 106001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyayapathi, N.; Lim, R.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Tiao, M.; Oh, K.W.; Fan, X.C.; Bonaccio, E.; Takabe, K. Dual scan mammoscope (DSM)—A new portable photoacoustic breast imaging system with scanning in craniocaudal plane. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 67, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Hu, D.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Ma, L. 3D photoacoustic tomography system based on full-view illumination and ultrasound detection. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T.; Ranasinghesagara, J.C.; Lu, H.; Mathewson, K.; Walsh, A.; Zemp, R.J. Combined photoacoustic and ultrasound biomicroscopy. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 22041–22046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.; Jung, Y.; Chang, S.; Park, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lovell, J.F.; Kim, C. Programmable real-time clinical photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging system. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-Y.; Park, S.; Lee, H.; Kang, M.; Kim, C.; Kim, J. Simultaneous dual-modal multispectral photoacoustic and ultrasound macroscopy for three-dimensional whole-body imaging of small animals. Photonics 2021, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.V. Effects of light scattering on optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 126014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Hu, H.; Zou, J. A focused optically transparent PVDF transducer for photoacoustic microscopy. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 20, 2313–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Jiang, L.; Cook, C.; Zeng, Y.; Vu, T.; Chen, R.; Lu, G.; Yang, W.; Hoffmann, U.; Zhou, Q. High-speed wide-field photoacoustic microscopy using a cylindrically focused transparent high-frequency ultrasound transducer. Photoacoustics 2022, 28, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, V.H.; Tran, L.H.; Choi, J.; Truong, H.-S.; Vo, T.H.; Vu, D.D.; Park, S.; Oh, J. Novel Water Probe for High-Frequency Focused Transducer Applied to Scanning Acoustic Microscopy System: Simulation and Experimental Investigation. Sensors 2024, 24, 5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Kerr, S.; Utkin, I.; Ranasinghesagara, J.; Pan, L.; Godwal, Y.; Zemp, R.J.; Fedosejevs, R. Optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy using novel high-repetition-rate passively Q-switched microchip and fiber lasers. J. Biomed. Opt. 2010, 15, 056017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslov, K.; Zhang, H.F.; Hu, S.; Wang, L.V. Optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy for in vivo imaging of single capillaries. Opt. Lett. 2008, 33, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, B.; Li, L.; Maslov, K.; Wang, L. Hybrid-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy for in vivo vasculature imaging. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 1521–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghesagara, J.C.; Jian, Y.; Chen, X.; Mathewson, K.; Zemp, R.J. Photoacoustic technique for assessing optical scattering properties of turbid media. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009, 14, 040504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, R.; Cinthio, M.; Dahlstrand, U.; Erlöv, T.; Naumovska, M.; Hammar, B.; Zackrisson, S.; Jansson, T.; Reistad, N.; Malmsjö, M. Clinical translation of a novel photoacoustic imaging system for examining the temporal artery. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2018, 66, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Agrawal, S.; Osman, M.; Minotto, J.; Mirg, S.; Liu, J.; Dangi, A.; Tran, Q.; Jackson, T.; Kothapalli, S.-R. A transparent ultrasound array for real-time optical, ultrasound, and photoacoustic imaging. BME Front. 2022, 2022, 9871098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Mirg, S.; Gaddale, P.; Agrawal, S.; Li, M.; Nguyen, V.; Xu, T.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Tu, W. Multiparametric brain hemodynamics imaging using a combined ultrafast ultrasound and photoacoustic system. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2401467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, N.; Dong, Z.; Lowerison, M.; Del Aguila, A.; Johnston, N.; Vu, T.; Ma, C.; Xu, Y.; Yang, W. Non-invasive deep-brain imaging with 3D integrated photoacoustic tomography and ultrasound localization microscopy (3D-PAULM). IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 44, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Hartanto, J.; Joseph, R.; Wu, C.-H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.-S. Hybrid photoacoustic and fast super-resolution ultrasound imaging. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Maslov, K.; Xing, W.; Garcia-Uribe, A.; Wang, L.V. Video-rate functional photoacoustic microscopy at depths. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, B.; Kim, T.Y.; Jung, S.; Choi, W.J.; Ahn, J.; Yoon, D.H.; Kim, J.; Jeon, S.; Lee, D. Quadruple ultrasound, photoacoustic, optical coherence, and fluorescence fusion imaging with a transparent ultrasound transducer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e1920879118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Song, W.; Huynh, E.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Helfield, B.L.; Leung, B.Y.; Goertz, D.E.; Zheng, G.; Oh, J. Methylene blue microbubbles as a model dual-modality contrast agent for ultrasound and activatable photoacoustic imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 016005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpiouk, A.B.; Aglyamov, S.R.; Mallidi, S.; Shah, J.; Scott, W.G.; Rubin, J.M.; Emelianov, S.Y. Combined ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging to detect and stage deep vein thrombosis: Phantom and ex vivo studies. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008, 13, 054061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- THORLAB Translation Stage. Available online: https://www.thorlabs.com/newgrouppage9.cfm?objectgroup_id=3002 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- THORLAB Brushless DC Motor Driven XY Stage. Available online: https://www.thorlabs.com/newgrouppage9.cfm?objectgroup_id=16022 (accessed on 18 January 2026).

- Truong, N.T.P.; Choi, J.; Park, S.; Ly, C.D.; Cho, S.-W.; Mondal, S.; Lim, H.G.; Kim, C.-S.; Oh, J. Ultra-widefield photoacoustic microscopy with a dual-channel slider-crank laser-scanning apparatus for in vivo biomedical study. Photoacoustics 2021, 23, 100274. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, V.H.; Choi, J.; Vo, T.H.; Vu, D.D.; Park, S.; Lee, B.-i.; Oh, J. An innovative application of double slider-crank mechanism in efficient of the scanning acoustic microscopy system. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 52, 4066–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.H.; Nguyen Van, T.; Cong Hong Nguyen, P.; Anh Do, T.; Truong, H.-S.; Nguyen Dinh, T.; Le, X.L. A simple approach in balancing the slider-crank mechanisms applied to new systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.-W.; Nguyen, T.-M.; Xia, J.; Arnal, B.; Wong, E.Y.; Pelivanov, I.M.; O’Donnell, M. Real-time integrated photoacoustic and ultrasound (PAUS) imaging system to guide interventional procedures: Ex vivo study. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2015, 62, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.J.; Hsieh, B.-Y.; Wei, C.-w.; Nguyen, T.-M.; Arnal, B.; Pelivanov, I.; O’Donnell, M. Optimization of the laser irradiation pattern in a high frame rate integrated photoacoustic/ultrasound (PAUS) imaging system. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), Taipei, Taiwan, 21–24 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.