Abstract

The rising demand for real-time perception in aerial platforms has intensified the need for lightweight, hardware-efficient object detectors capable of reliable onboard operation. This survey provides a focused examination of real-time aerial object detection, emphasizing algorithms designed for edge devices and UAV onboard processors, where computation, memory, and power resources are severely constrained. We first review the major aerial and remote-sensing datasets and analyze the unique challenges they introduce, such as small objects, fine-grained variation, multiscale variation, and complex backgrounds, which directly shape detector design. Recent studies addressing these challenges are then grouped, covering advances in lightweight backbones, fine-grained feature representation, multi-scale fusion, and optimized Transformer modules adapted for embedded environments. The review further highlights hardware-aware optimization techniques, including quantization, pruning, and TensorRT acceleration, as well as emerging trends in automated NAS tailored to UAV constraints. We discuss the adaptation of large pretrained models, such as CLIP-based embeddings and compressed Transformers, to meet onboard real-time requirements. By unifying architectural strategies, model compression, and deployment-level optimization, this survey offers a comprehensive perspective on designing next-generation detectors that achieve both high accuracy and true real-time performance in aerial applications.

Keywords:

UAV; aerialobject detection; edge; real time; efficient; lightweight; onboard; optimization 1. Introduction

A growing trend in the advancement of autonomous Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) is their use for real-time mapping, alongside the implementation of deep learning techniques for the semantic analysis of data collected by UAVs [1]. Developing autonomous Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs) primarily depends on their detection ability of static and moving objects [2], which makes UAV object detection essential during navigation for the aid of autonomous ground vehicle path planning [3,4]. UAVs have a broad range of applications that rely on object detection beyond navigation. They are employed in security and surveillance, including border patrol and the efficient monitoring of significant areas. UAVs provide valuable visual data to help responders plan rescues and locate survivors [3]. In the industry, UAVs play a vital role in inspecting infrastructure and monitoring environmental health. For example, UAVs are used for asphalt pavement cracking [5], wildlife conservation [6], and forest health checking (detecting dead trees or the incidence of disease) [7]. Similarly, UAVs are useful for mining exploration because they can provide relevant information on geological features, mineral deposits, and surface topography. In the same sense, UAVs are valuable tools in the construction industry. They help construction sites monitor safety regulations and compliance, as well as track construction progress.

RGB images are extensively used in aerial detection due to their rich colour and texture features. However, aerial detection poses various challenges. The distant areas of UAV aerial images frequently include numerous densely clustered small objects with few pixels of representation, making them difficult for standard detection algorithms to identify [8]. As a result, Information can be lost during the convolution process in feature extraction [9,10]. Previous studies have proposed several approaches to enhance the detection of small objects. One common strategy is replication augmentation, in which small objects are copied and randomly placed at different locations within the image, thereby increasing the number of small-object samples available for training [11]. Another approach involves scaling and splicing, in which larger objects in the original image are resized to generate additional small object instances. In addition, some methods focus on loss function adjustment, giving higher weight to the losses associated with small objects to encourage the model to pay more attention to them during training [11]. And some recent studies add an extra detection head to shallower layers for small object detection. However, improving the detection of small objects generally comes with an increase in model complexity and computational requirements, making it increasingly difficult to satisfy the requirements for real-time applications on memory- and processing-constrained platforms [12].

Fine-grained discrimination remains a major challenge in aerial detection, where visually similar classes often appear with only a few pixels and minimal texture. Although attention mechanisms, transformer-based feature alignment, and contrastive learning can significantly enhance fine-grained representations, feature map is another solution, in addition to spatial attention; these strategies typically increase computational burden and require more complex pipelines, limiting their suitability for real-time onboard deployment [13]. In low resolution, Spatially-adaptive Convolution SPDConv combined with Efficient Channel Attention ECA is used for fine-grained downsampling, and swin transformers for long-range dependancies [14]. This offers real-time performance but not on edge device.

High-resolution images facilitate the detection of small objects and the extraction of fine-grained features. However, increasing the resolution increases complexity. High-resolution feature extraction networks [15] for small object detection are complex; however, some emerging solutions include adding a super-resolution module that learns high-resolution features from low-resolution input, and this module is applied only during training to enhance detection while removed in inference for faster detection [16]. In [17] Fine-grained Information extraction module based on SPDConv with a multiscale feature fusion module based on BiFPN with skip connections to enhance fine-grained feature representation.

Another challenge is the scale and perspective differences: Objects may appear at different sizes and orientations depending on their distance from the camera and the angle of view. This challenge is addressed by using strategies such as Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs), which have been widely applied to new detection tasks. These approaches advocate improved detection of small objects by leveraging features from multiple model layers. Nevertheless, they involve considerable computational requirements, potentially affecting real-time performance, especially on devices with limited resources [18].

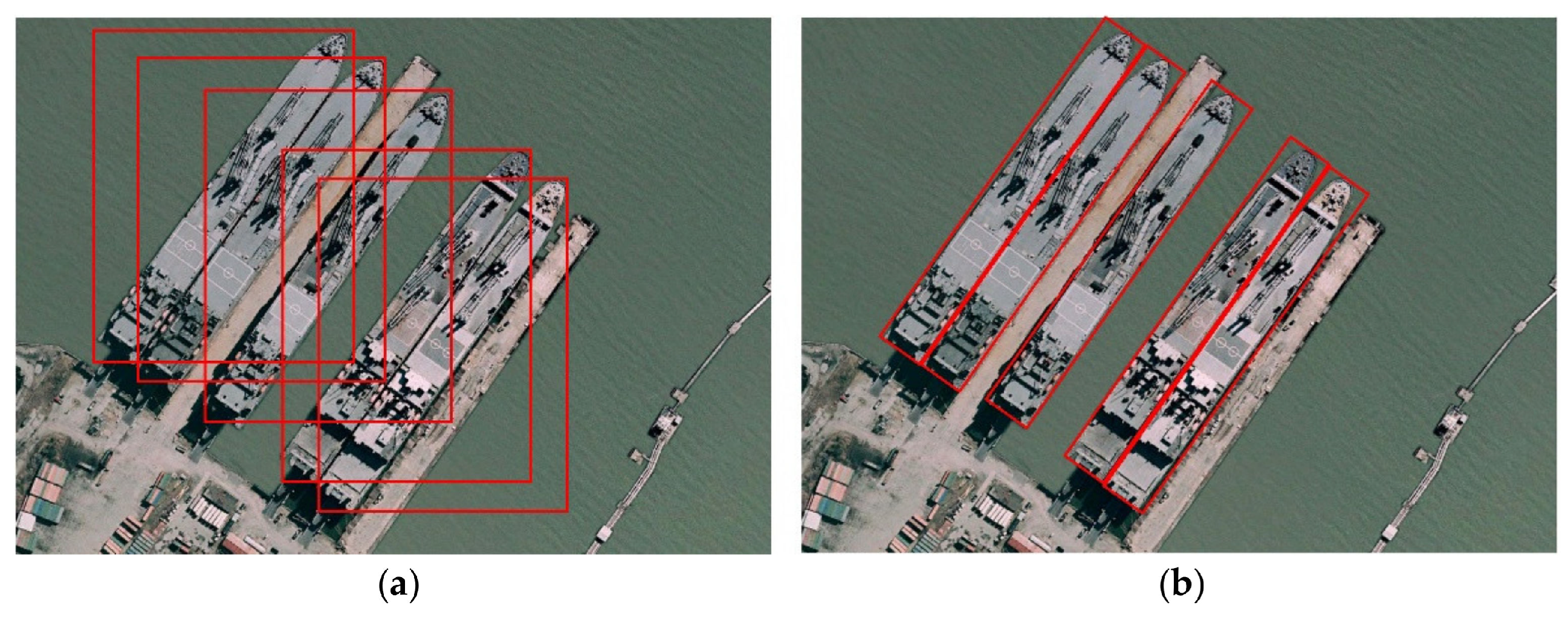

Moreover, the orientation of objects presents another challenge [19]. Earlier datasets feature horizontal boundary boxes that are suitable for ground platforms. This can lead to inaccuracies in aerial detection, especially in detecting dense scenes. Addressing this issue depends on the algorithm; many studies adopt single-stage anchor-based algorithms with Horizontal Boundary Box (HBB) detections. Additionally, some studies employ Oriented Boundary Box (OBB) detections to handle objects at various angles. OBB detection can start with predefined anchors of different sizes and angles, or use horizontal anchors. After the initial detection, the model applies additional algorithms or layers to refine these anchors. This refinement process involves predicting offsets or adjustments to the position, size, and orientation of the anchors [20]. In anchor-free methods, the orientation is solved by different strategies, including regressing width, height, and angle at each center point using anchor-free feature maps [21]. Gaussian centerness and pseudo-domain angle encoding are used for OBB regression in [22], while ref. [23] uses channel expansion and dynamic label assignment is implemented to regress rotated boxes efficiently for real-time UAV imagery. These solutions increase the complexity of the models, affecting real-time inference.

In aerial remote sensing, a complex environment refers to a variety of scene conditions that make accurate object detection more difficult. Such conditions include background clutter, where targets are easily confused with surrounding structures, partial occlusions, in which objects are obscured by other elements in the scene, and changes in illumination, including shadows, bright sunlight, and low-light scenarios that alter visual appearance. Complex environments often contain unusual or previously unseen objects, which can significantly degrade object detection performance [19,24]. Context-Aware Compositional Networks address this challenge by modeling the relationships between object parts and their surrounding context, supplemented by additional contextual enhancements [25]. A solution to this includes self-attention in transformer models and dilated and cross-convolutions, which expand the receptive field but do not offer a lightweight solution for the process. Although methods such as attention mechanisms, Transformer-based feature alignment, and contrastive learning improve the representation of fine-grained local features, they are typically computationally demanding and rely on more complex processing pipelines [26].

Additionally, class imbalance in training datasets poses a problem. Some object classes are overrepresented, while others have limited samples, leading to models that perform well on common classes but poorly on rare ones. To mitigate this in aerial object detection, researchers adopt a variety of strategies, spanning data augmentation, loss design, feature representation, and learning paradigms. At the data level, techniques like K-means SMOTE generate synthetic minority class samples, while augmentation methods such as object copy paste and aggregated-mosaic increase the occurrence and contextual variation of rare objects [27]. For the algorithm loss, reweighting mechanisms, including Class Balanced Loss, based on the effective number of samples [28], focus training on difficult examples. For feature-level improvements, modules like Discriminative Feature Learning and Imbalanced Feature Semantic Enrichment [29], promote both semantic richness and better separation of rare classes. Finally, improved training protocols, such as duplicating rare-class objects (Auto Target Duplication) and ensuring that every augmentation patch contains at least one object (Assigned Stitch), help ensure that minority categories are sampled more effectively, thereby helping models learn from rare instances more reliably [30]. In [31], a hard chip mining strategy is designed to balance class distribution and produce challenging training examples. The approach begins by creating multi-scale image chips for training the detector. In parallel, object patches are extracted from the dataset to form an object pool, which is then used for data augmentation to alleviate class imbalance. The detector trained on this augmented data is subsequently run on the modified images to identify misclassified regions, from which hard chips are generated. The final detector is trained using a combination of regular chips and these hard examples. Altogether, these combined methods reduce sample scarcity, sharpen feature discrimination, and strengthen detection performance on long-tailed aerial datasets. Addressing these challenges is essential to improving the reliability and accuracy of object detection systems across diverse and complex settings.

Ultimately, real-time processing requirements for applications such as surveillance demand fast yet accurate object detection models, a difficult combination that researchers must balance to achieve both accuracy and speed [32]. Deep learning models for detecting small objects at low altitudes can be quite complex and computationally intensive. This complexity can be challenging to implement with edge computing systems that have limited processing and memory resources available [33].

For applications that demand faster detection, such as military operations and search-and-rescue missions, there is a need for onboard processing directly on the UAV. They make extensive use of object detection for secure navigation, to identify both dynamic and stationary objects, and for real-time decision making [3,4]. This is particularly relevant for applications such as path planning for unmanned autonomous ground vehicles, where UAVs assist with mapping and obstacle avoidance This enables real-time decision making without reliance on external networks, reducing communication delays and ensuring secure of information and rapid response in time sensitive situations.

Achieving real-time object detection processing on UAV platforms remains a significant challenge, particularly due to the limited computational resources. While improvements in GPU computing power have made object detection more accessible, optimizing performance while maintaining accuracy and efficiency remains an ongoing area of research. In object detection, Real-time processing initially relied on cloud-based computing, in which data is transmitted to remote servers for analysis. However, the need for lower latency and faster decision-making in various applications has led to the development of edge computing, making processing closer to the platform itself. In many applications, a hybrid approach, combining cloud and edge computing, is used, where edge processing is prioritized for speed-critical tasks, while cloud resources handle more complex computations and long-term data storage [34].

Real-time performance on UAVs with limited computational resources requires specialized algorithmic and architectural optimizations. Many approaches focus on designing efficient lightweight detection models to reduce computational overhead [33,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. In addition to architectural improvements, various optimization techniques are applied to enhance efficiency further. One of these approaches is quantization, which reduces numerical precision, lowering computational complexity and memory usage, making the model more suitable for edge devices [21,45,51,53,54,55,56,57]. Also, Pruning is another optimization method that eliminates low-importance weights, reducing model size while maintaining performance [5,45,58,59,60,61,62]. In addition to knowledge distillation, which allows a smaller model to learn from a larger, more complex model, retaining essential knowledge while significantly reducing computational demands [63,64]. These optimization approaches, whether used separately or together, play a critical role in achieving real-time object detection on UAVs.

Several recent surveys have examined object detection from different perspectives. For example, ref. [65] provides a broad 20-year overview of object detection algorithms and their evolution, while ref. [66] systematically categorizes detectors into traditional and deep learning pipelines, covering one-stage, two-stage, transformer-based, and lightweight methods. Their analysis highlights the strengths and weaknesses of classical approaches, summarizes performance gains achieved through architectural design and feature learning, and identifies gaps related to lightweight models through comparative experiments and evaluation metrics. However, although lightweight networks are mentioned, these works do not explain how such models are integrated and developed specifically for aerial object detection, as they have different challenges compared to general natural scene detectors, nor do they address real-time processing, compression techniques, edge deployment requirements, or suitable algorithms for embedded platforms.

Only a limited number of studies focus directly on aerial detection. Among them, ref. [9] summarizes the main challenges and recent advances in deep learning for aerial imagery and reviews frequently used datasets; however, it lacks a deeper discussion on how to handle these challenges effectively and does not address lightweight or real-time methods. Similarly, ref. [67] reviews techniques for small object localization in aerial images, and [68] surveys object-oriented detection, but both remain limited in scope. Real-time detection is considered in only a few works; for instance, ref. [69] focuses on FPGA-based implementations but does not cover other commonly used devices, nor does it discuss the unique challenges of aerial imagery that increase detection complexity.

The review in [39] provides a detailed analysis of real-time processing strategies, algorithm speed, and sensor usage in UAV-based object recognition. However, most of these studies primarily report overall performance metrics without examining architectural design, the evolution of each detector component, or the requirements for real-time onboard processing. They discuss lightweight network architectures used as full networks, without discussing the developed modules from these networks, which are integrated into the general detector’s design and structure to enable aerial detection and achieve real-time performance. Furthermore, they lack a detailed examination of quantization strategies and pruning methods, which are not detailed in those reviews. Deployment frameworks, lightweight design principles, and emerging trends in convolution methods, edge-transformers, efficient attention mechanisms, head design, and end-to-end lightweight pipelines suitable for real-time and edge-level deployment. And a lack of more details about emerging trends, including the emerging edge transformers, hardware-aware NAS, adapting large vision-language models or CLIP embeddings for aerial detection, or integrating NAS and compression methods with these models to improve performance, and emerging trends in this area towards real-time and edge performance for such models.

Although several surveys have examined aerial object detection, see Table 1, they exhibit important limitations that restrict their relevance to real-time UAV deployment. Existing reviews focus primarily on high-level algorithmic families and overlook the end-to-end onboard pipeline, including preprocessing, postprocessing, quantization, pruning, TensorRT acceleration, and cloud–edge latency. They also provide limited coverage, hardware-aware design, trained quantization rather than post-training quantization, and structured pruning methods. Transformer refinements are now essential for achieving fast and accurate models on edge devices. Critically, earlier surveys rarely analyze Neural Architecture Search (NAS) frameworks tailored for UAV constraints or the emerging use of CLIP-style semantic embeddings for domain adaptation, despite their growing role in improving robustness and cross-scene generalization. Dataset discussions also lack emphasis on fine-grained benchmarks and high-resolution scenarios, small-object definitions, and specific datasets for small objects. Finally, most reviews fail to provide quantitative comparisons mAP, FPS, parameter count, on real embedded devices such as Jetson Nano, Xavier NX, Orin, NPUs, or Raspberry Pi, and tarde offs with typical use of detectors.

Table 1.

Summary of recent reviews and surveys on object detection.

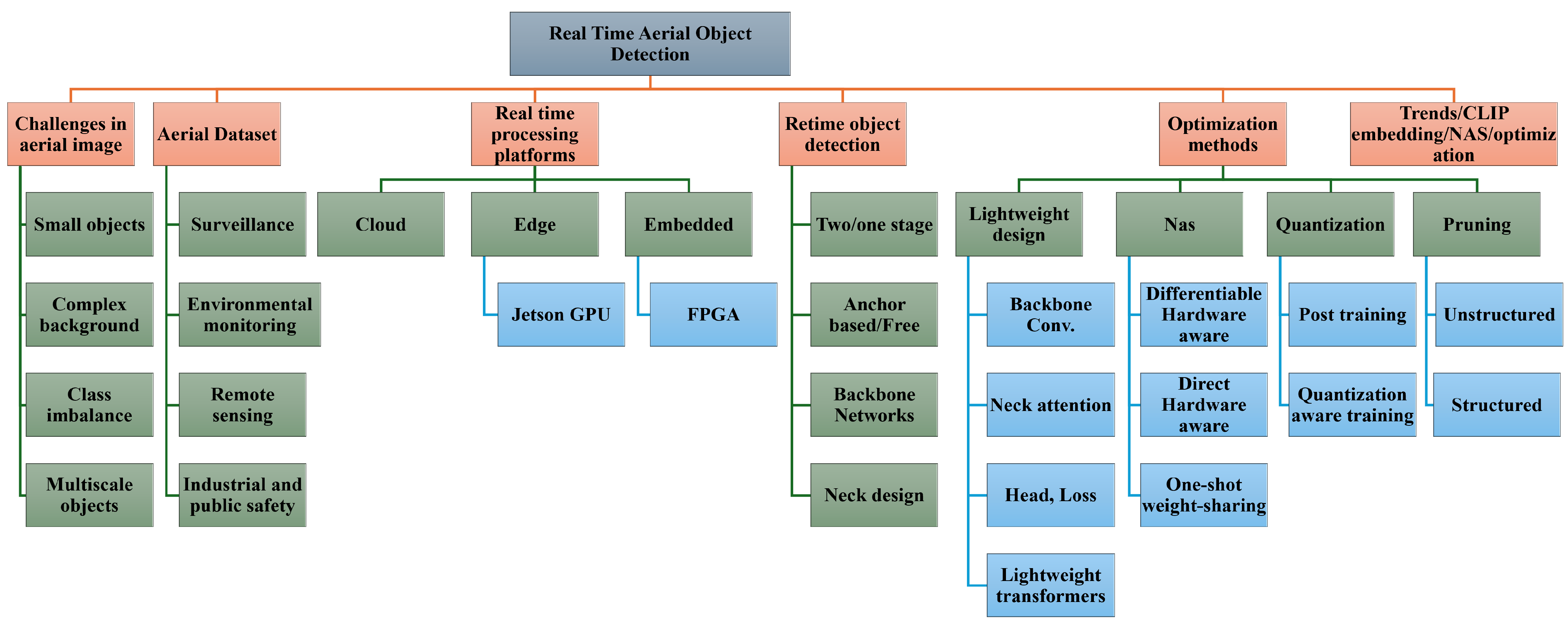

By these gaps, this review concentrates on the architectural components of modern detectors, along with hardware-oriented considerations and adaptive strategies essential for achieving real-time aerial object detection. Our survey integrates lightweight architectural advances with the practical constraints of embedded UAV platforms, connecting efficient backbone design, small-object enhancement, and multi-scale fusion with deployment strategies such as quantization post-training and trained quantization, pruning types, re-parameterization, TensorRT optimization, and federated edge learning. By incorporating recent progress in UAV-oriented NAS, we highlight how automated architecture exploration produces models that better balance accuracy and latency under strict power budgets, which can be further integrated with other methods, such as pruning for further efficiency. Additionally, we address the emerging role of CLIP-based semantic and visual embeddings in domain adaptation, a role that prior reviews do not discuss. Figure 1 gives insight into the review structure and topics.

Figure 1.

Overview of the survey’s main topics.

The survey contributions are summarized below:

- Small object definition in aerial datasets and fine-grained datasets.

- Specify the real-time processing approaches and analyses covering performance and the platforms used, general detectors, typical applications for each model, how to modify them to mitigate aerial detection challenges, and keep efficient, with more focus on real-time studies with limited resources.

- Systematically review real-time aerial processing approaches, including platform-level constraints, performance analyses, and the typical adaptations required to modify general-purpose detectors for aerial challenges while maintaining efficiency on resource-limited hardware.

- Analyze lightweight design strategies across the detection pipeline, covering backbone, neck, and attention mechanisms, and new research for the developed RT-DETR design for edge deployment.

- Performance evaluation of recent edge research.

- Explain additional optimization techniques, such as pruning and quantization, with details about the new method, including quantization-aware training.

- Present emerging compression and hardware-aware optimization methods, including their integration with large vision–language models and multimodal distillation, to enable efficient deployment on UAV and edge devices.

- We identify the key limitations in current real-time aerial object detection research and discuss open challenges, offering insights and future research directions to advance onboard, real-time UAV perception.

The remaining is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the commonly used datasets referenced in the surveyed studies, highlighting their characteristics and relevance to aerial detection tasks. Section 3 reviews real-time processing techniques and summarizes the performance of existing edge and onboard systems. Section 4 explains general object detection paradigms and general lightweight networks. Section 5 This section reviews lightweight optimization strategies for aerial object detection, covering efficient backbone and detector design, model compression techniques, and emerging hardware-aware methods. It also highlights recent trends in integrating large language models with compressed architectures to enhance aerial detection under real-time and resource-constrained conditions. Section 6 presents limitations in the current research, open challenges, and future directions. Finally, Section 7 presents the overall conclusions of this survey and summarizes the key insights derived from the reviewed literature.

2. Datasets and Recent Real-Time Research Applications

Aerial and remote-sensing datasets are collected from platforms such as UAVs, manned aircraft, and satellites. Therefore, they differ from natural-scene datasets, including COCO and Pascal VOC, in several measurable ways. UAV imaging is commonly grouped into three altitude bands: close-range eye-level flights at 0–5 m, low-to-medium operations between 5 and 120 m, and high-altitude aerial imaging conducted at heights exceeding 120 m [9]. Aerial imaging also includes remote sensing images collected from multiple sensors and platforms (e.g., Google Earth), including satellite images with multiple resolutions [70].

Aerial Images and natural scene ground-level images do not use the same definition of object scale. In the natural scene images, where objects appear at consistent scales, the term small object refers to objects measuring fewer than 32 × 32 pixels [71], medium objects 32 × 32 to 96 × 96 and large objects above 96 × 96 [72], while in aerial and UAV imagery, the height of the horizontal bounding box, referred to as the pixel size, is used as the measure of object scale. Based on this criterion, instances in the dataset are categorized into three groups: small (10–50 pixels), medium (50–300 pixels), and large (greater than 300 pixels) [70].

In aerial scenes, Fine-grained discrimination refers to the challenge of distinguishing visually similar classes that often occupy only a few pixels and exhibit minimal texture. Although several studies attempt to address this problem, they generally rely on aerial datasets not explicitly designed for fine-grained detection [14,15,17,18,19]. Among these, only ref. [50] employs a dataset explicitly created for fine-grained tasks, with the Mar-20 dataset [73] and SeaDronesee [74] serve as a benchmark curated specifically for this purpose. These datasets serve different applications, as described in Table 2, which offers a comprehensive overview of datasets commonly employed in aerial object detection, illustrating their practical applications across domains and corresponding references.

These datasets’ images are captured by different satellite and UAV platforms, which are commonly classified into three types: fixed-wing, rotary-wing, and hybrid designs. Fixed-wing drones operate at higher altitudes, cover large areas quickly, and offer long endurance due to their simple structure and efficient gliding capability, though they require runways for takeoff. Rotary-wing UAVs can hover, take off, and land vertically, and fly at low altitudes to capture detailed, high-resolution data, making them well-suited for close-range inspection and sensing tasks. Hybrid platforms combine the strengths of both systems [75].

Table 2.

Summary of commonly used datasets in aerial object detection, including statistics and key attributes.

Table 2.

Summary of commonly used datasets in aerial object detection, including statistics and key attributes.

| Dataset | Description | Images | Instances/Objects | Classes | Size/Resolution | Annotation Type/Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VisDrone [76,77] | Drone-captured images and videos | 263 video clips with 179,264 frames and additional 10,209 static images | 540k | 10 | 765 × 1360 to 1050 × 1400 | HBB; high proportion of small, occluded and truncated objects | [11,12,33,34,35,36,39,41,44,45,46,47,51,52,57,61,62,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| DOTA [70,99] | Aerial/satellite images | 2806 images (v1) | 188,282 instances (v1) | 15 | From 800 × 800 to about 4k × 4k | OBB; rotated and multi-scale objects | [14,38,40,82,84,100] |

| UAVDT [101] | UAV-based vehicle detection, | 80k images (Video) | 841.5k vehicles | 4 | 1080 × 540 | HBB; low-altitude, high density, small object | [79,87,88,95,102] |

| CARPK [103] | Parking lot vehicle counting | 1448 images | 89,777 vehicles | 1 | 1280 × 720 | HBB; small-to-medium vehicles | [6,91,104,105] |

| DroneVehicle [106] | RGB-Infrared vehicle detection | 28,439 RGB-Infrared pairs | 953,087 both modalities | 5 Vehicles | 840 × 712 | OBB; multimodal RGB-IR | [40,46,85] |

| NWPU VHR-10 [107] | High-resolution remote sensing | 715 from google earth images 85 images from Vaihingen data set | 2.934k instances | 10 | from 533 × 597 px up to 1728 × 1028 | HBB; planes, ships, vehicles | [46,105] |

| DIOR [108] | Optical remote sensing images | 23,463 images | 192,472 instances | 20 | 800 × 800, 0.5–3 0 m | HBB; large-scale, cross-sensor variety | [14,33,84] |

| UA-DETRAC | Vehicle detection | 10 h of video (140,000 frames) | 1.21 million vehicles | 4 | 960 × 540 | HBB; traffic videos | [45] |

| UCAS-AOD | Aerial vehicle detection | 1510 images | 2500 instances | 2 | 1000 × 1000 | HBB | [84] |

| SODA-A [109] | Small object detection in aerial images | 24,000 images | 338,000 small instances | 10 | 800 × 800 | HBB; tiny objects | [38] |

| SEVE [110] | Small object detection | 17,992 pairs of images and labels | - | 10 | 1920 × 1080 | HBB; Special vehicles in construction sites | [110] |

| FSD | small target scenes of fire and smoke | 7534 images | N/A | N/A | N/A | HBB; 3 Fire hazard scenario, 3 non-hazard scenario | [42] |

| PVD | Photovolatic point defects (PDs) and line defects (LDs) | 1581 images | 2721 | 1 | N/A | HBB | [79] |

| SAR-SD | Ship Detection dataset | 1160 images | 2456 | 1 | resolutions (1 to 15 m). | HBB | [111] |

| AU-Air | Low altitude traffic survellance | 32,823 images | 132,034 | 8 | 1920 × 1080 | HBB | [6] |

| Traffic-Net [112] | Traffic sign detection | 4400 images | 15,000 signs | 1 | 512 × 512 | HBB | [52] |

| Rail-FOD23 | Railway infrastructure detection | 2000 images | 10,000 instances | 1 | 512 × 512 | HBB | [43] |

| Dead Trees | Forest dead tree detection | 3000 images | 15,000 instances | 1 | 512 × 512 | HBB | [7] |

| Mar-20 | Remote-sensing image dataset for fine-grained military aircraft recognition | 3842 images | 22,341 instances | 20 | 800 × 800 | HBB; Fine grained | [50] |

| VEDAI [113] | Vehicle detection in parking lots | 1210 images | 3640 vehicles | 9 | (12.5 cm × 12.5 cm per pixel, 1024 × 1024 | HBB, multimodal, visible and Near infrared | [114] |

| UAV Image | UAV-based detection | 10,000–50,000 images | 50,000+ instances | Various | 1024 × 1024 | HBB | [115] |

| PVEL-AD | Photovoltaic panel defect detection | 5000 images | 20,000 defects | 1 | 512 × 512 | HBB; defect-focused | [116] |

| RSOD | Remote sensing small object detection | 886 images | 5000 instances | 4 | 600 × 600 | HBB; small objects | [105] |

| SeaDronesSee [74] | maritime search and rescue | 54,000 | 400,000 | 6 | 1280 × 960 to 5456 × 3632 | HBB; 91% small objects, finegrained | [117] |

| AFOs | maritime search and rescue | 3647 images | 39,991 | 1 | 1280 × 720 to 3840 × 2160 | HBB; small objects in open water | [117] |

- Aerial Object Detection Applications

2.1. Surveillance and General Object Detection

One of the most prominent application areas is surveillance and general object detection from UAVs, where datasets like VisDrone [5,46,57,93] are extensively utilized due to their rich annotations, high scene variability, and suitability for real-time, low-altitude aerial scenarios. Another dataset used in surveillance is CARPK [91], which focuses on UAV-based vehicle detection and parking lot vehicle counting. Typical platforms are DJI Mavic, Phantom series (3, 3A, 3SE, 3P, 4, 4A, 4P) (DJI, Shenzhen, China), used in the VisDrone dataset and DJI M200 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) used in the DroneVehicle dataset, both of which are rotary UAVs.

2.2. Environmental Monitoring

Also, another vital domain of application is environmental monitoring. For example, outfall structure detection is conducted with tailored datasets created for certain environmental compliance cases [118]. Wildlife detection, which typically requires efficient models on UAV platforms, has datasets available, like WAID and AU-AIR [6], with annotations on aerial imagery of wildlife capturing various animal species and natural environments. Emergency response systems, such as UAV fire monitoring, use thermal and RGB imagery during and after fire events that have been annotated for real-time detection [119]. In addition to applications like dead tree detection in forestry, it enables health monitoring of vegetation through spectral analysis.

2.3. Remote Sensing and High-Resolution Geospatial Object Detection

An emerging area of research is focused on remote sensing and high-resolution geospatial object detection. For example, multi-class object detection in satellite imagery relies on datasets like DOTA, DOTA-CD and AIR-CD [100], which allow for object detection in different orientations and with multi-scale sizes, in both complex urban and rural settings. These datasets are important for accommodating scale and rotation variability prevalent in remote sensing images. The AERO system [34] likewise demonstrates an AI-enabled UAV observational platform that is trained on private aerial data as well as the VisDrone dataset. AERO seamlessly provides high-level object detection and detailed tracking of detected objects across its UAV deployments in real-world scenarios. Lastly, methods developed for ultra-high-resolution (UHR) imagery have employed frame-tiling approaches in conjunction with parallel YOLO processing [120], allowing for real-time inference without sacrificing detection accuracy. Remote sensing platforms include satellites and airborne digital monitoring systems.

2.4. Industrial and Public Safety

The applications of real-time aerial object detection are crucial for industrial and public safety monitoring and inspection across a variety of industries. For example, in the coal mining industry, the CMUOD dataset [48] is designed to replicate the visual conditions found in underground mining environments, such as low-light conditions and small spaces, when detecting objects. In urban mobility and traffic analysis, MultEYE has been developed for vehicle detection and tracking and uses a custom-built UAV-based traffic monitoring dataset to allow for real-time monitoring of crowded streets and flow analysis [120]. When considering industrial infrastructure monitoring more broadly, railway infrastructure inspection represents another key application. The use of the Rail-FOD23 dataset [43] is an example of how inspection is performed using high-resolution aerial images annotated to detect faults and foreign object debris along railway tracks to support the operational safety of trains. Likewise, in the energy space, UAV-based systems for aerial defect detection in photovoltaic (PV) panels have been used, as in [116], and can be utilized to identify surface defects, shading, and damage across large solar farms with minimal human interaction during inspection.

2.5. Search and Rescue (SAR) Operations

The use of UAV-based object detection has also been explored in search and rescue (SAR) operations. These tasks generally relate to spotting humans or objects in rough terrain, and researchers have evaluated algorithms with datasets such as DIVERSE TERRAIN, RIT QUADRANGLE, and AUVSI SUAS [121] that represent various environmental settings, such as urban, rural, and wooded. At the same time, the demand for real-time pedestrian detection in videos from UAVs has resulted in the development of lightweight detection models, which have been evaluated on a custom UAV-based pedestrian dataset [56]. In addition to marins SAR operations [117]. In SAR missions, fixed-wing UAVs are used for their long-range search [122].

3. Real-Time Processing Platforms

Numerous real-time object detection algorithms have been executed on desktop GPUs [33,38,39,40,41,42,45,46,47,78,79,81,82,83,84,86,87,89,91,105,110,123]. But for real-world applications, cloud computing, edge processing, or embedded processing are the most common. While cloud computing may provide substantial computational resources, it introduces latency when running methods such as UAV-based object detection or autonomous navigation in real time. Some studies have proposed a hybrid cloud-edge processor to optimize speed and cost effectiveness [124]. Real-time onboard performance is crucial, yet only a few studies have achieved near-real-time performance (<30 FPS), and fewer have successfully implemented real-time onboard detection at speed (≥30) FPS [125]. The standard video processing benchmark of object detection is 30 frames per second [126]. However, other studies record lower detection rates that are less than this level [47]. Despite the ability of high-performance desktop graphics cards, such as the GeForce GTX1080 Ti, GeForce RTX3090, and GeForce RTX4080, to achieve real-time performance [127], other computational systems remain difficult to match. Maintaining similar speeds across diverse computing environments, such as edge devices, remains challenging due to the computational demands of these algorithms, often resulting in severe speed degradation [49,50,90,115]. Table 3, which shows the performance of recent real-time studies on the VisDrone dataset with corresponding desktop platforms used.

Table 3.

Real- time aerial studies tested on VisDrone2019/2021 with their corresponding performance and platforms used.

YOLOv8 models are evaluated across various versions, including YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv5, on platforms such as NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090. YOLOv8s achieves mAP50 of 42% at a speed of 126 FPS and an inference time of 7.8 ms evaluated on the VisDrone2019 dataset [123]. In contrast, YOLOv5 models (e.g., YOLOv5m and YOLOv5l) on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080Ti show similar performances but with varying speeds and inference times. YOLOv5 achieved 94.6% precision, with an inference speed of 17.8 FPS and an inference time of 70 ms on a TITAN RTX [84], while YOLOv8s achieved 45.8% precision with 77.6 FPS at 9.9 ms inference time on an A30 platform on the UAVDT dataset [119]. Other datasets, such as VisDrone2021-DET and DOTA, showcase similar trends, with the YOLO models offering varying trade-offs among precision, inference speed, and model size across different hardware platforms. In terms of real-time performance, YOLOv5s and YOLOv8s demonstrate competitive inference speeds, with YOLOv5s-obb showing higher mAP values and faster inference times on specific datasets such as DOTA and CARPK [86].

Despite these limitations, research on RGB-based object detection using edge computing has shown promising results on the NVIDIA Jetson family of devices, achieving speeds between 14 FPS and 47 FPS [6,39,49,50,51,57,102,115,119,128]. These findings highlight the potential of optimizing object detection models for real-time performance on resource-constrained platforms. Most studies report performance on desktop GPUs, whereas real-world applications employ three processing approaches: cloud, edge, and embedded computing. The following sections highlight key studies within each of these categories.

3.1. Cloud Computing

Cloud computing is a model in which end devices, such as mobile phones, autonomous vehicles, and sensors, are connected to central servers for data processing across a large network. Central servers provide computing, storage, and digital services to users through the internet. The main drawbacks of this method are the increasing volume of edge data (collected data from drones that is transferred to ground station for processing), which is restricted by network bandwidth, and the time required to transfer data to the server, along with the need for an internet connection [129]. To overcome these issues, edge computing is used. To evaluate the trade-offs between computational capacity and latency in edge and cloud settings, experiments in [130] were performed using the YOLOv8s (FP16) model on the Orin Nano. The assessment focused on round-trip time, inference latency, and communication delay to characterize real-time performance across both environments, see Table 4. Round-Trip Time (RTT) (ms) represents the total duration required for a complete inference loop, covering both network transmission delays and model processing time. It provides an overall evaluation of the system’s performance in real time.

Table 4.

Latency results in the two different deployment scenarios, edge and cloud [130].

The cloud latency shows a low value of 6.82 ms compared to the edge at 32.59 ms; however, the cloud communication latency reduces its efficiency by 341.41 ms compared to the edge, 2.5 ms only.

3.2. Edge AI Object Detection

Edge AI applies AI processing near end users at the network’s edge. In edge computing data processing is performed directly on the device or node where the data is generated [131,132]. Devices capable of supporting edge computing include System-on-Chip (SoC), Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA), Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC), Central Processing Unit (CPU), and Graphics Processing Unit (GPU). FPGAs have been initially viewed as one of the most promising platforms for deploying AI models due to their low power consumption. However, their limitations in inference speed and the lack of broad support for deep-learning frameworks make them less competitive today. ASICs can deliver excellent performance for specialized applications, but their long development time and high cost restrict their ability to keep pace with the fast evolution of object detection methods. In contrast, ongoing advances in semiconductor manufacturing have significantly improved the performance of GPUs, CPUs, and memory. These developments have expanded the edge-level computational resources available for neural networks, making the deployment of AI models on edge devices increasingly practical [11]. GPU-based edge platforms are closely linked to the development of deep learning and have become widely adopted for object detection due to their enhanced computational power. Typical computing platforms designed for embedded applications generally consume no more than 15W when operating under load [102]. In video detection, the NVIDIA Jetson family are frequently combined with portable devices to facilitate online detection [133,134]. Four types of edge GPU-based platforms are commonly used in the literature: NVIDIA Jetson Nano [135], NVIDIA Jetson TX2 [115], and NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX [136,137] NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier [127]. It is worth mentioning that GPUs have been first introduced for real-time aerial detection in 2019 [138].

These embedded GPU platforms have higher energy efficiency compared to laptop and desktop GPUs [139], where NVIDIA Jetson TX2 and Jetson Xavier NX models are mostly used due to their moderate power consumption compared to the other series [140]. Few studies adopt a cloud-edge collaborative framework, in which the cloud provides scalability with virtually unlimited resources for large-scale data or complex tasks. At the same time, edge devices can independently scale using lightweight models optimized for specific UAV tasks. In [124], It integrates an Edge-Embedded Lightweight (E2L) object detection algorithm with an attention mechanism that helps a model focus on the most relevant parts of the input when making decisions, enabling efficient detection on edge devices without sacrificing accuracy. A fuzzy neural network-based decision-making mechanism dynamically allocates tasks between edge and cloud systems. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework outperforms YOLOv4 in edge-side processing speed (NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX) and provides better overall performance than traditional edge or cloud computing methods in both speed and accuracy.

3.3. Embedded-Onboard Object Detection

Embedded systems such as FPGA and Raspberry Pi 4B are used in a few studies research [141,142]. These systems are typically deployed directly on the UAV, using embedded or edge GPUs to perform all processing, including object detection, onboard the platform itself [138]. Table 5 shows the performance of onboard detection algorithms on edge GPUs and embedded devices.

Table 5.

Embedded/Edge Platforms with onboard aerial studies references.

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) and Onboard Aerial Object Detection

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) have gained increasing attention in aerial object detection because they provide true hardware-level parallelism and extremely low latency. Their large arrays of programmable logic units and DSP slices allow convolution, activation, and pooling operations to run concurrently, enabling fast per-frame processing even under tight compute budgets, which is a requirement typical of UAV-based video streams (Directory of Open Access Journals; Propulsion Tech Journal). Unlike fixed accelerators, FPGAs also offer full reconfigurability, allowing neural network operations or classical vision pipelines to be mapped directly into hardware. This flexibility supports aggressive quantization, pipelined dataflows, and resource-aware custom designs, particularly suitable for embedded and UAV platforms [69]. Another major advantage is energy efficiency. FPGA-based detectors generally consume far less power than GPU systems because of their optimized dataflow and parallel execution, which is essential for battery-powered aerial vehicles operating in resource-constrained environments.

Lightweight versions such as Tiny-YOLOv3, YOLOv11-Nano, and YOLOv11-S illustrate how reducing depth, channel width, and detection heads directly lowers Look-Up Table (LUT), A Look-Up Table (LUT)BRAM, and Digital Signal Processing Slice DSP consumption. Recent FPGA implementations of YOLOv11 use techniques such as depthwise-separable convolutions, CSP-based blocks, memory-efficient routing, loop tiling, and multi-PE parallelism to achieve real-time performance despite limited on-chip resources. Other optimization strategies, such as convolution lowering, increase PE utilization and reduce DRAM traffic by converting k × k kernels into expanded 1 × 1 operations. Deployment on specialized FPGA DPUs further boosts performance, as demonstrated by LCAM-YOLOX running at 195 FPS on ZCU102 and YOLOv5 achieving over 240 FPS on Versal platforms with minor layer modifications. Additional FPGA-friendly designs, such as Tiny DarkNet, also achieve high throughput and low power through fixed-point quantization and spatial parallelism. Comparisons with SSD reveal that although SSD can achieve high throughput, its deeper backbones and multi-scale feature processing require significantly more memory and power, making real-time FPGA deployment less common. Overall, YOLO-based models remain the preferred choice for embedded detection due to their predictable dataflow, lower resource demands, and suitability for highly parallel FPGA architectures, while the optimal FPGA device ultimately depends on whether the application prioritizes power, speed, or resource efficiency [143].

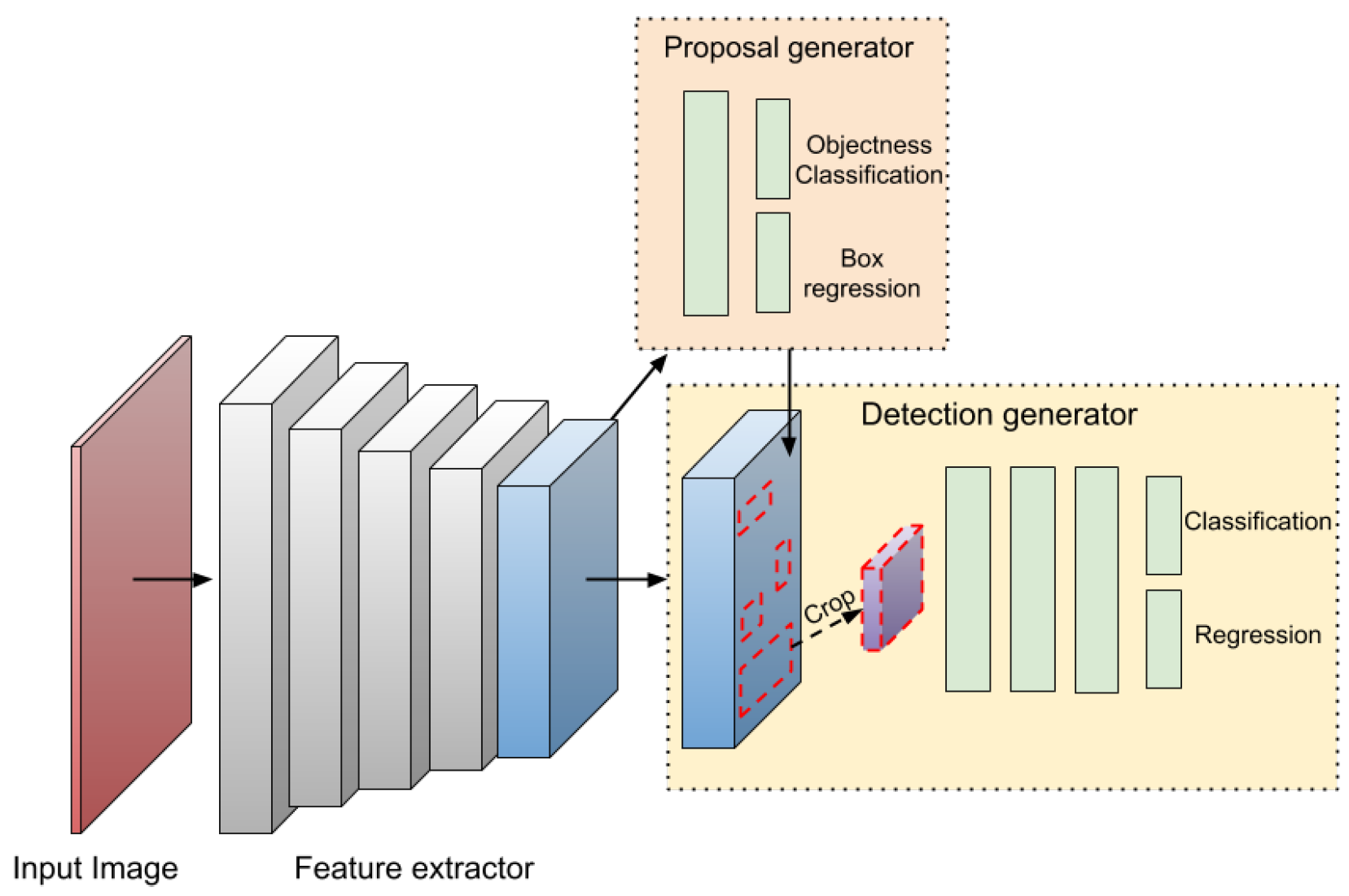

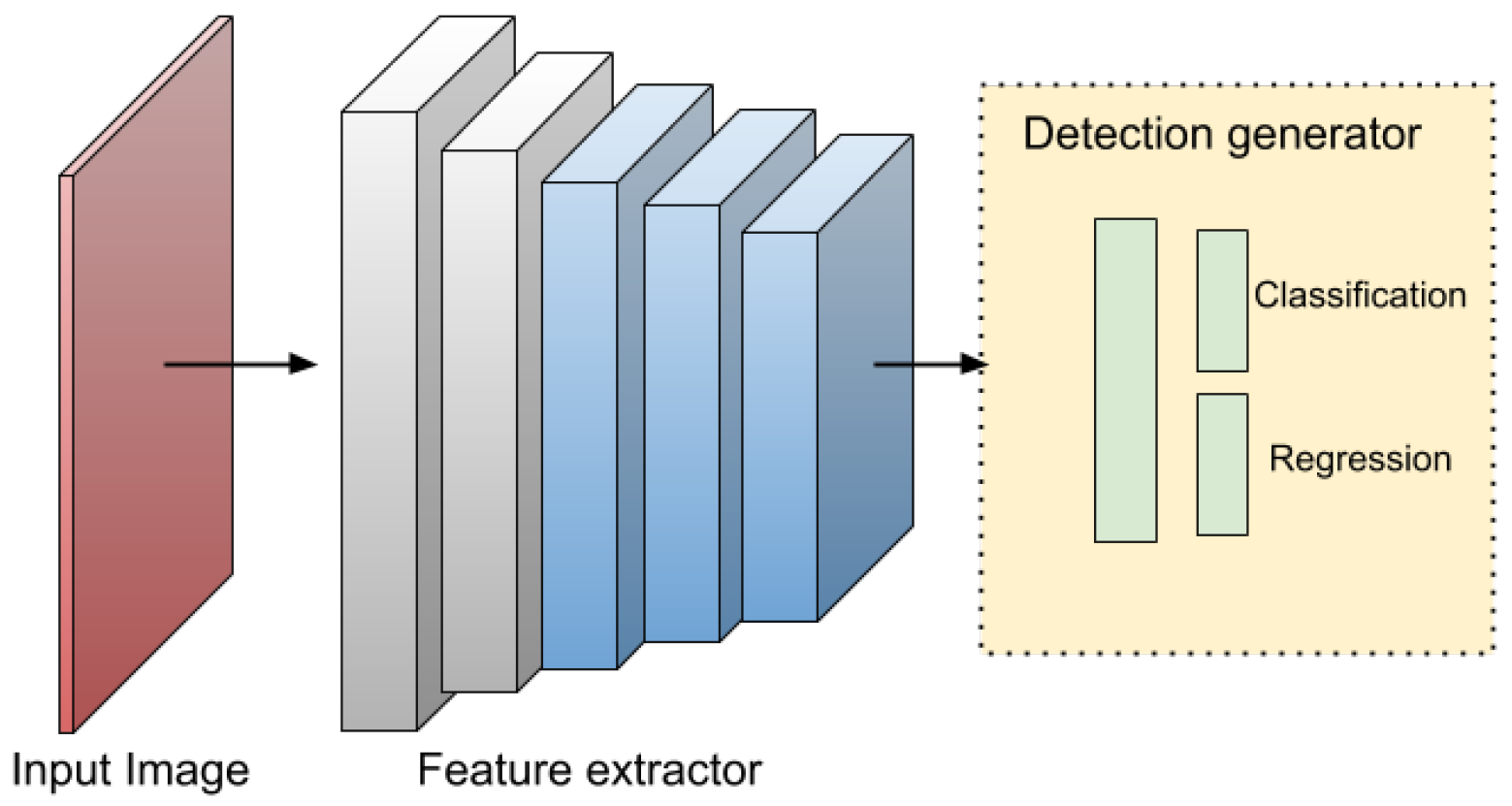

4. Aerial Real-Time Deep Learning Object Detection Algorithms

A typical object detector comprises two main components: a backbone for feature extraction and a head for making predictions about object categories and bounding boxes, see Figure 2 and Figure 3. The backbone, usually made up of convolutional layers, produces feature maps that capture key visual information such as edges, textures, and shapes from the input image. Common backbone architectures include the Visual Geometry Group (VGG), Residual Network (ResNet), its extended version ResNeXt, DenseNet, MobileNet, SqueezeNet, and ShuffleNet. Based on the configuration of the detection head, detectors are generally categorized as either two-stage or one-stage models [9]. In recent advancements, an intermediate component called the neck has been introduced to aggregate and enhance multi-scale feature maps from different backbone layers before passing them to the head.

Figure 2.

Two-stage algorithm main diagram [144].

Figure 3.

One-stage algorithm main diagram [144].

4.1. Two-Stage and Single Stage Detectors

The following Two-stage algorithms, such as R-CNN, SPP-Net, Fast R-CNN, and Faster R-CNN, achieve high precision but at the cost of slower inference, making real-time detection challenging. In contrast, one-stage algorithms like SSD, YOLO, and RetinaNet prioritize speed, making them suitable for real-time applications, though they often exhibit lower accuracy compared to two-stage methods [9].

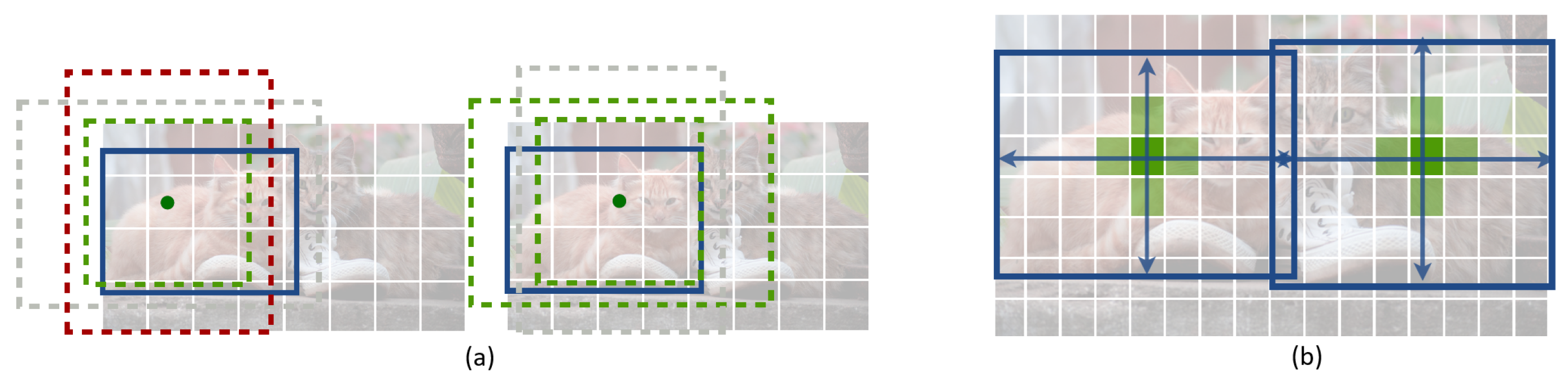

Whether a detector uses a single-stage or two-stage framework, it still must choose between two main ways of producing bounding boxes: anchor-based or anchor-free detection. This distinction is especially important in aerial scenarios because it directly affects efficiency, small-object performance, and suitability for onboard real-time UAV deployment. Anchor-based methods rely on predefined bounding boxes during training to predict objects, whereas anchor-free approaches eliminate the need for predefined anchor boxes and directly predict. object locations from feature maps, offering greater flexibility and reduced computational overhead, see Figure 4.

Figure 4.

(a) Standard Anchor assignment, the green anchor denotes a positive match (IoU > 0.7), the red anchor indicates a negative sample (IoU < 0.3), and the gray anchor represents an ignored case with an intermediate IoU. The blue box shows the ground-truth object, (b) anchor-free center-based detection, the center pixel is treated as the positive location, surrounding pixels receive reduced negative loss, and the object dimensions are predicted through regression [145].

4.1.1. Anchor Based Methods

In many object detection models, the image is split into a grid, and predefined anchor boxes of various sizes and shapes are placed at each grid cell. These anchors guide the model in predicting different objects in the image by providing a set of initial guesses for where objects could be. The model then learns to adjust the position, size, and shape of these anchor boxes to better match the actual objects, refining them into the final predicted bounding boxes. A process called Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) is used to remove overlapping boxes, keeping only the best one. The model uses Intersection over Union (IoU), a metric that measures the overlap between the detected bounding box and the ground truth, and confidence scores to decide which boxes to keep. The confidence score indicates how sure the model is that a box contains an object and what type of object it is. This process ensures accurate and non-redundant detections. A prediction is regarded as a true positive if the Intersection over Union (IoU) between the prediction and its closest ground-truth annotation exceeds 0.5. In the post-processing step called Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), these predictions are filtered to result in one bounding box for each object [146].

While these methods are effective, they present several challenges, including false positives, difficulties with varying aspect ratios, and high computational costs [147]. The reliance on anchor boxes increases redundancy and computational overhead, complicating Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), a technique that removes duplicate detections by retaining only the bounding box with the highest confidence score [146]. Additionally, anchor-based methods often suffer from poor generalization across different object shapes and create an imbalance between positive and negative samples, which complicates training, particularly for edge AI systems [22,148].

Within anchor-based detection, different bounding box strategies exist. The Horizontal Bounding Box (HBB) approach is computationally efficient and offers faster inference due to the lower number of anchors required. However, it frequently produces false positives, especially in dense scenes, where it may fail to distinguish among multiple objects or include non-object regions within the bounding box. In contrast, the Oriented Bounding Box (OBB) approach enhances detection accuracy by incorporating angle parameters, making it particularly beneficial for objects with large aspect ratios, such as vehicles and ships see Figure 5. Despite this advantage, OBB-based methods significantly increase computational complexity, requiring approximately six times as many anchors as HBB, making them considerably slower [149].

Figure 5.

(a) Horizontal Boundary Boxes (HBB) and (b) Oriented Boundary Boxes (OBB) [150].

For high recall rates, anchor-based detectors must densely place a large number of anchor boxes in the input image, such as over 180,000 anchor boxes in FPN networks for an image with a shorter side of 800 pixels [145]. Recall measures how well the model finds all the relevant objects in an image. It is the ratio between the number of actual objects that the model successfully detects-true positives-and the total number of actual objects, which is the sum of true positives and missed objects. A high recall means the model detects most of the objects but might include some false positives. Balancing recall with precision, which measures the accuracy of the detections, is essential for overall performance [151]. During training, the majority of these anchor boxes are marked as negative samples. The large quantity of negative samples exacerbates the imbalance between positive and negative samples in training. In addition, it can lead to potential latency bottlenecks when transferring predictions between devices in edge AI systems [152]. To address this issue, anchor-free methods have emerged.

4.1.2. Anchor Free Methods

Anchor-free detection eliminates the need for predefined anchor boxes and directly predicts object locations from feature maps. This approach improves adaptability to a range of object sizes and aspect ratios while significantly reducing computational complexity. Only a small number of anchor-free detectors are built on two-stage frameworks [21]. RepPoints [153] is a representative example that replaces anchors with learnable point sets that capture object extent and key semantic regions. SRAF-Net [154] also adopts an anchor-free strategy but embeds it within a Faster R-CNN structure, increasing complexity. Similarly, AOPG [152] introduces oriented proposals via feature alignment modules based on Faster R-CNN. Although these methods improve localization, especially for rotated objects, they remain computationally demanding and are not suitable for real-time UAV deployment. Popular anchor-free methods such as CenterNet [145], CornerNet [155], and FCOSR [21] adopt one-stage methods with different strategies, including predicting object centers, corners, or bounding box distances. Thereby avoiding the complexities associated with anchor box design and tuning [145]. These methods provide greater flexibility and efficiency in object detection by avoiding the constraints imposed by anchor boxes.

4.2. Lightweight Networks

In object detection models, the backbone is a critical component in lightweight design, often responsible for more than 50% of the total computational load during inference [156]. Many standard networks are too computationally heavy for real-time UAV or embedded applications, motivating the adoption of lightweight backbones in remote sensing image analysis [50]. Table 6 summarizes these backbones, highlighting their key convolution methods and structural strategies for efficient feature extraction.

Table 6.

Summary of lightweight network architectures.

The evolution of lightweight backbones begins with SqueezeNet (2016) [157], which introduces the Fire module to replace standard 3 × 3 convolutions with 1 × 1 kernels, reducing parameters while maintaining channel flexibility. MobileNetV1 (2017) [158] adopts depthwise separable convolutions, significantly improving computational efficiency compared to standard VGG-style convolutions. Its successor, MobileNetV2 (2018) [159], integrates residual connections and linear bottlenecks, combining expansion and compression of feature dimensions to enhance feature extraction.

ShuffleNet (2018) [160] focuses on channel-level operations, using pointwise group convolutions and channel shuffle to maintain information flow across groups. ShuffleNetV2 (2018) [161] refines this design by splitting the input channels into two branches, processing one while leaving the other unchanged, followed by concatenation and channel shuffle, thereby balancing computational cost and simplicity.

GhostNet (2020) [164] emphasizes redundancy reduction through cost-efficient linear operations to generate extra feature maps, and GhostNetV2 (2022) [166] extends this with Dynamic Feature Convolution (DFC) attention for better local-global feature extraction in mobile-friendly applications.

Finally, FasterNet (2023) [165] addresses inefficiencies in depthwise convolutions using Partial Convolution (PConv) to limit memory access and redundant computations. This enables FasterNet to achieve faster inference across GPU, CPU, and ARM platforms while maintaining competitive accuracy. For instance, FasterNet-T0 surpasses MobileViT-XXS with 2.8× faster inference on GPU, 3.3× on CPU, and 2.4× on ARM, while improving ImageNet-1k top-1 accuracy by 2.9%. Moreover, the FasterNet-L variant achieves an 83.5% accuracy, comparable to Swin-B, while delivering 36% higher GPU throughput and reducing CPU compute time by 37% [165].

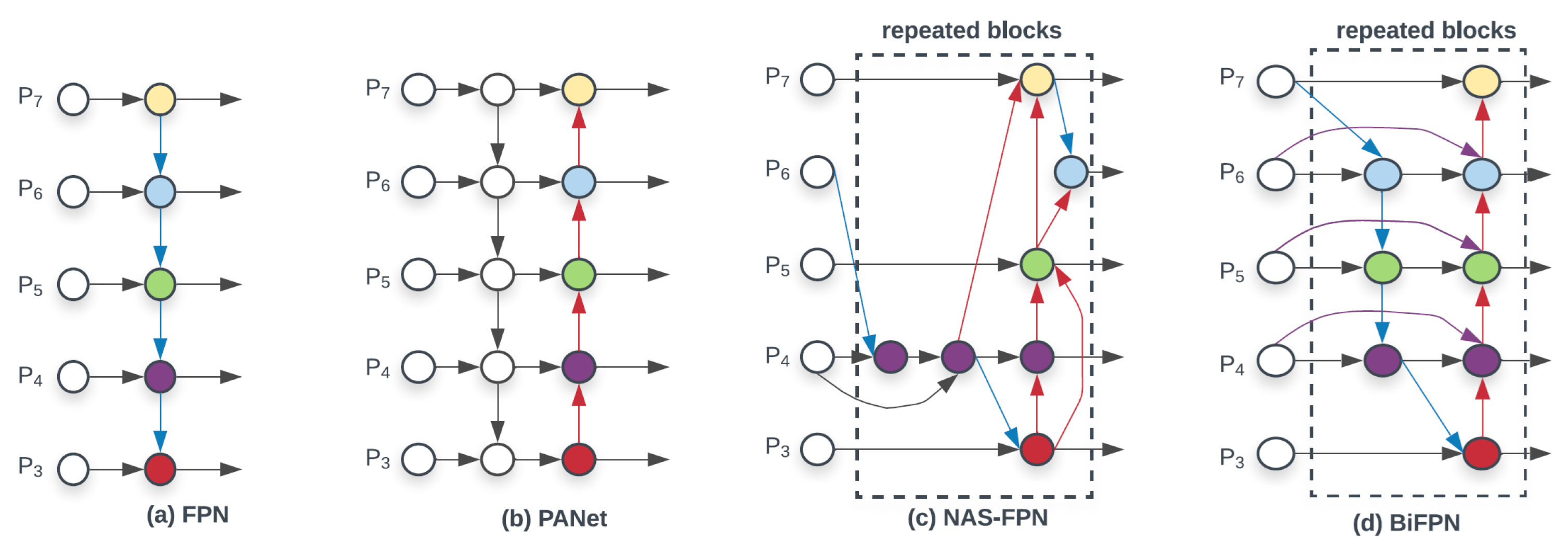

4.3. Neck Network

The neck in object detection models acts as a bridge between the backbone and the head, aggregating and refining multiscale features for final prediction. Early structures such as the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [167], enriched shallow features with deeper semantic information, but its top–down design struggled to preserve spatial detail. PANet [168], adopted in [43,47], addressed this by adding a bottom–up pathway to strengthen shallow feature representation. EfficientDet later introduced the Bi-Directional FPN (Bi-FPN) [169], used in [86], which employs weighted top–down and bottom-up fusion for improved efficiency. Fusion in FPN-style structures typically relies on element-wise addition for efficiency [167], although concatenation is sometimes used when a richer representation is required. Neural Architecture Search (NAS) further automated feature pyramid design in NAS-FPN [170], Figure 6 shows the general neck structures.

Figure 6.

Different feature fusion networks [169].

4.4. Attention Modules

Attention modules play a critical role in enhancing feature representations by directing the model’s attention to the most informative regions of an image. In computer vision, attention mechanisms are predominantly categorized into two types: channel attention and spatial attention. Both types enhance original feature representations by aggregating information across positions, though they differ in their strategies, transformations, and strengthening functions [171]. Fundamental attention mechanisms and their enhanced variants have been employed throughout the research. Table 7 shows these basic mechanisms and their key features and limitations.

Table 7.

Comparison of Attention Mechanisms.

When comparing attention modules in terms of computational overhead, ECA attention introduces less overhead than CBAM and SE. At the same time, SA has a similar overhead to ECA. The Triplet Attention mechanism also maintains lower overhead compared to both CBAM and SE. Similarly, NAM (Normalization-based Attention Module) and SimAM (Simple Attention Module) are also lightweight alternatives, with SimAM being parameter-free and NAM maintaining low complexity, both significantly lighter than the mentioned methods.

The Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE-2018) module [172] effectively strengthens channel-wise feature encoding but does not account for spatial dependencies.

To address this limitation, modules such as the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM-2018) [173], Bottleneck Attention Module (BAM-2018) [174], sequentially derive attention map in two dimensions, channel and spatial dimension; however, they attempt to utilize positional information by decreasing the channel dimension and then generating spatial attention by convolutions, but convolutions are limited to capturing local relationships and struggle to model long range, which are crucial for vision tasks.

Global context network (GCNet-2019) [175] incorporates spatial attention, though their reliance on convolutional operations constrains their capacity to model long-range dependencies. However, these integrated CBAM–GCNet designs often face challenges, including slow convergence and increased computational complexity.

Efficient Channel Attention (ECA-Net) [176] streamlines the channel attention mechanism of the SE block by employing a 1D convolution to compute channel weights more efficiently. Similarly, Spatial Group-wise Enhance (SGE) [177] divides the channel dimension into multiple sub-groups, each intended to capture distinct semantic representations, and applies spatial attention within each group using attention masks that scale feature vectors across spatial locations, adding minimal computational overhead and virtually no additional parameters. Despite these innovations, such models often underutilize the joint relationship between spatial and channel attention. Moreover, they typically do not incorporate identity-mapping branches, thereby limiting their overall efficiency and effectiveness.

Coordinate Attention (CA) [178] introduces positional encoding tailored for lightweight networks, improving localization while maintaining efficiency. Meanwhile, the Normalization-based Attention Module (NAM-2021) [179] selectively suppresses less relevant features, contributing to computational efficiency. Triple Attention [180] achieves a balance between cost and performance by modeling both spatial and channel-wise interactions without significant overhead. While transformer-based self-attention mechanisms offer strong global feature modeling capabilities, their high computational cost poses challenges for real-time applications on resource-constrained UAV platforms.

The Shuffle Attention (SA) [181] module provides an efficient solution by integrating two types of attention mechanisms through the use of Shuffle Units. It begins by dividing the channel dimension into several sub-features, which are then processed in parallel. Each sub-feature is passed through a Shuffle Unit to capture dependencies across both spatial and channel dimensions. Finally, the outputs from all sub-features are combined, and a channel shuffle operation is applied to facilitate information exchange among them.

Simple Attention Module (SimAM) [182] offers a unique approach compared to traditional channel-wise or spatial-wise attention mechanisms by directly generating 3D attention weights for each neuron in a feature map—without introducing additional parameters. SimAM formulates an energy function to assess neuron importance and derives a fast, closed-form solution that can be implemented efficiently. Its simplicity avoids the need for complex structural design or tuning. Recent research has demonstrated the strategic integration of attention modules across different stages of detection architectures.

4.5. Real-Time Aerial Object Detectors

All algorithms mentioned previously in Section 4 are general-purpose detectors, mainly trained and evaluated on natural-scene datasets. Because aerial imagery has distinct properties (e.g., small targets, dense object distributions, complex backgrounds), it faces specific challenges that require dedicated treatment. The majority of recent studies reviewed in this survey primarily adopt YOLO detectors, particularly YOLOv8, followed by YOLOv5, and then YOLOv7. New versions of YOLO have been released: YOLOv11 and YOLOv12, and YOLO-Gold. A summary of the specifications for each YOLO version and its typical use is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Summary of YOLO series models: architecture, features, and limitations.

Most aerial object detection studies develop YOLO algorithms to meet the requirements of aerial challenges or to make onboard detection more efficient. The new YOLO models (YOLOv5, YOLOv8) come in different sizes, each optimized for specific use cases, balancing speed, accuracy, and computational efficiency. The smallest version, YOLO nano version (YOLOvn) is designed for extreme efficiency, making it suitable for edge AI applications and low-power devices where real-time processing is essential with minimal hardware requirements used for lightweight aerial detection as in [35,36,39,48,50,51,89,90,116]. YOLO-Small (YOLOvs) provides a balance between speed and accuracy, making it an ideal choice for real-time applications on embedded systems and mobile devices like in [7,12,33,37,43,48,51,81,82,83,87,118]. YOLO-Medium (YOLOvm) provides a trade-off between computational cost and detection performance. YOLO-M is well-suited for applications that require improved accuracy while maintaining reasonable inference speeds. YOLO-Large (YOLOvl) is more performant, with more parameters and higher accuracy, but has higher computational requirements. YOLO-X-Large (YOLOvx) is more accurate but more rigorous in development, and most often operates in a high-performance computing environment where real-time requirements are less important [199].

Table 9 summarizes the developed aerial studies along with the basic models they employ. These models have been adapted to suit various aerial detection scenarios and different application requirements, with real-time performance on desktop GPUs.

Table 9.

Developed aerial studies and their base detection model.

As shown in Table 9, for real-time applications, the smaller versions, such as YOLOvn and YOLOvs, are preferred because they achieve high-speed inference with lower latency, making them well-suited for tasks such as autonomous navigation, robotics, and surveillance. The ability to select a model based on the specific needs of an application allows YOLO to remain a versatile and widely used object detection framework in both edge and cloud-based AI systems, mainly the small and Nano ones. The performance evaluation of the lightweight detectors, YOLOv9t, YOLOv7tiny, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv10s has been conducted in [201], This study evaluated YOLO models on a Jetson Xavier-equipped drone, emphasizing speed, accuracy, and resource efficiency under TinyML principles. Key metrics included inference time, mAP, GPU usage, and power consumption. YOLOv10n achieved the best balance (10.34 ms, 0.657 mAP), while YOLOv9-tiny also performed well (13.55 ms, 0.688 mAP) with slightly higher resource use. YOLOv10s achieved the highest accuracy (0.77 mAP) but demanded more power and GPU resources, favoring accuracy scenarios. However, fewer approaches apply another detector, as in [119], in which SSD detector is used.

To achieve real time time performance diffrent methods have been adapted targeting the design of lightweight models aiming to reduce size and computational complexity [163,203,204], most of them achieve this by replacing the backbone with lightweight networks [119], or by changing some module in the network [7,33,36,38,40,43,47,61,62,78,79,81,82,83,84,86,89,104,110,111,200], with fewer studies have explored other methods such as parameter pruning [57,62], quantization [5,7,39,42,46,49,56,57,115] and Knowledge distillation [63,64]. The one-stage object detector comprises three main components: The backbone for feature extraction, the neck for multiscale feature fusion, and the head, which locates objects in images and assigns classes. Various optimization and design modifications have been applied to enhance the efficiency and speed of models, with the majority of these changes focused on the backbone [7,33,38,43,81,84,110,111] and neck structure [89,104]. Fewer studies modify the head [40,91]. Studies that change backbone and neck [36,40,47,61,62,78,79,81,82,83,86,200].

The Refined Anchor-Free Rotated YOLOX detector (R2YOLOX) [205], which is an enhanced version of YOLOX [188] for aerial imagery, is an example of an anchor-free YOLO version in addition to YOLOv8 and later versions, which have also adopted an anchor-free approach and been used in many research, further advancing real-time object detection performance [35,48,92]. In recent real-time research, various algorithms have been used for aerial object detection.

5. Optimization Methods

Aerial object detection systems deployed on UAV platforms face resource constraints in terms of computation, energy, and latency, making optimization a core requirement rather than an optional enhancement. Unlike ground-based detectors that can rely on powerful servers or desktop GPUs, onboard aerial systems must operate under limited computational resources while still providing real-time, reliable detection. Therefore, optimization methods in the literature aim to either reduce the computational burden, enhance detection accuracy under resource limitations, or balance both goals to meet real-time performance requirements. In [206], Model compression for object detection is generally categorized into five main approaches: lightweight network design, pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, and neural architecture search (NAS), which are described in detail in the following subsections.

5.1. Lightweight Design for Real-Time Aerial Detection

The following subsections provide a detailed analysis of some studies, highlighting their contributions to onboard algorithm design and optimization. The following explains the design of the lightweight backbone, neck, and head.

5.1.1. Lightweight Backbone Networks

Since the backbone is the most computationally intensive component, most lightweight models focus on designing efficient backbone architectures, following optimization strategies commonly adopted in aerial detection algorithms.

- A.

- Convolution-Based Lightweight Designs

In real-time aerial detection, many studies replace the original backbone with lightweight architectures to improve efficiency under embedded constraints, as demonstrated in [40,41]. Recent backbone design trends focus on replacing standard convolutions with more efficient operators, particularly in YOLO-based models such as YOLOv5 and YOLOv8. Common approaches include Depthwise Separable Convolution (DWSeparableConv) [7,47,86], often coupled with channel shuffle operations [36,44], followed by broader adoption of Ghost Convolution [39,110], Partial Convolution (PConv) [38,43], and MobileNet Bottleneck Convolution (MBConv) [81,200]. Some models integrate hybrid dilated convolutions with partial convolutions to enrich receptive fields [38], while others employ advanced variants such as Omni-dimensional Dynamic Convolution (ODConv) [111] to introduce input-adaptive filtering.

Since the backbone is the most computationally demanding component of the YOLO architecture, it plays a central role in extracting multi-scale visual features before they are passed to the neck for further aggregation [207]. Therefore, optimizing the backbone directly affects both accuracy and inference speed. As illustrated in Table 10, which summarizes works achieving real-time performance on Jetson GPUs and embedded platforms, different studies target distinct architectural sections; however, nearly 85% apply lightweight modifications to the backbone, underscoring its dominant contribution to total computational cost.

Lightweight aerial detection backbones thus integrate a spectrum of strategies with efficient convolutions, compact attention modules, reparameterized multi-branch structures, and lightweight downsampling and fusion blocks to enable high-speed onboard inference.

A major category of these methods is convolution-based lightweight design, where computationally expensive operations are replaced with more efficient alternatives. ShuffleNetV2 is widely adopted in this context: YOLOv6 combines it with the Multi-Scale Dilated Attention (MSDA) module to enhance multi-scale processing [97]. At the same time, YOLOv5n incorporates ShuffleNetV2 together with Coordinate Attention to improve spatial sensitivity [50]. Rep-ShuffleNet continues this trend by removing the traditional 1 × 1 convolution used for dimensional alignment and introducing a depthwise convolution block (DwCB) within a dual-branch structure during training [48]. Ghost-based techniques are frequently used to reduce redundancy, as seen in WILD-YOLO, which replaces multiple YOLOv7 backbone modules with GhostConv [6]; MSGD-YOLO, which integrates Ghost and dynamic convolution for adaptive feature extraction [35]; and the MGC module, which merges MaxPooling, GhostConv, and PConv to minimize parameters [125]. A streamlined YOLOv8s variant similarly replaces parts of the C2f block with GhostBlockV2, reducing complexity while preserving representational capacity [90]. Complementing these approaches, the IRFM module combines multi-scale dilated convolutions with trainable weighted fusion to enhance contextual representation, especially for small-object detection in cluttered scenes [5].

- B.

- Attention-Enhanced Lightweight Modules

These methods maintain representational quality by integrating efficient channel- or coordinate-attention mechanisms. Coordinate Attention (CA) has been incorporated into the YOLOv5n backbone alongside ShuffleNetV2 to enhance spatial and orientation awareness [50]. Similarly, Rep-ShuffleNet integrates Efficient Channel Attention (ECANet), which employs adaptive k-nearest neighbor based kernel selection and a refined shortcut design to strengthen channel-wise feature interactions [48]. Beyond these explicit attention mechanisms, other models adopt attention implicitly. MSGD-YOLO utilizes dynamic convolution, which inherently provides input-adaptive attention [35], whereas the IRFM module introduces a trainable weighted fusion strategy that acts as a soft attention mechanism to emphasize multi-scale contextual responses [5].

- C.

- Reparameterization and Structural Re-Design

These approaches improve training expressiveness through multi-branch structures, then collapse them into efficient single-path inference architectures. RepVGG introduces a structural re-parameterization strategy in which multi-branch convolutional blocks used during training are merged into a single equivalent convolution at inference, enabling the model to maintain accuracy while substantially reducing MACs, an approach that forms the basis of the structural design used in Rep-ShuffleNet [48]. Building on this concept, Rep-ShuffleNet adopts a dual-branch architecture composed of a depthwise convolution branch (DwCB) and a shortcut pathway during training, which is then collapsed into a simplified structure for efficient inference [48]. Likewise, RTD-Net employs a Lightweight Feature Module (LFM) that distributes computation across homogeneous multi-branch pathways, reducing redundancy while preserving strong representational power [115].

- D.

- Lightweight Pooling, Downsampling and Feature Fusion Modules

These modules enhance feature hierarchy while reducing interpolation or element-wise overhead. Lightweight downsampling and fusion strategies are also employed to strengthen feature hierarchies with minimal computational overhead. The MGC module integrates MaxPooling with GhostConv to achieve efficient downsampling through a combination of pooling and lightweight convolution [125], while the DSDM block in Spatial Pyramid SOD-YOLO enhances deep–shallow hierarchical representation using a compact downsampling structure [46]. Additionally, the IRFM module incorporates a trainable weighted multi-scale fusion mechanism applied over dilated convolutions, improving contextual encoding and boosting small-object detection performance in complex environments [5].

5.1.2. Efficient Neck Networks

- A.

- Enhancements to Classical FPN Structures for UAV Detection

In UAV scenarios, where objects are small and spatially sparse, enhanced feature pyramids are widely adopted. Dense-FPN (D-FPN) [104], used in YOLOv8, improves shallow-feature extraction by repeatedly integrating shallow and deep features using downsampling, upsampling, and convolution. The SPPF module enhances multiscale perception by extracting deep semantic context before merging with shallow layers, while the Dense Attention Layer (DAL) strengthens channel- and spatial-wise focusing via average, max, and stochastic pooling.

YOLOv5’s neck is modified in [79] to include a Bidirectional FPN (BDFPN), which expands the FPN hierarchy and introduces skip connections for improved multi-scale fusion, particularly valuable in dense UAV scenes with large object-scale variation.

YOLOv8 adopts a lighter PAN-FPN variant that removes post-upsampling convolutions to reduce computational load. However, this limits small-object detection due to reduced high-resolution feature fusion. To improve this, [123] presents BSSI-FPN, extending the pyramid upward to preserve spatial detail and adding a micro-object detection head. Additional downsampling blocks between the backbone and the neck further enhance semantic–spatial integration.

- B.

- Attention- and Module-Based Feature Fusion Enhancements

Several designs enhance feature fusion via attention or cross-scale interactions. In [89], a PA-FPN is augmented with the Symmetric C2f (SCF) module for deep feature refinement and the Efficient Multiscale Attention (EMA) module for enhanced spatial–channel coupling. Its Feature Fusion (FF) block improves texture–semantic blending. Similarly, [12] integrates the AMCC module into PA-FPN to reduce redundancy and preserve small-object details via channel spatial attention.

The MLFF module in [62] merges shallow, middle, and deep features of identical spatial size but different channels to reduce computation while preserving multi-scale richness. The Scale Compensation Feature Pyramid Network (SCFPN) in [78] replaces the large-object detection layer with an ultra-small object layer to better target fine-scale features. Additional improvements include the C2f-EMBC module in [81], which replaces bottlenecks with EMBConv and adds SE-like attention for memory-efficient enhancement, and SCFPN’s adaptation in [82], which further strengthens the merging of low-level spatial cues with high-level semantics. Cross-layer and weighted fusion improvements also exist. CWFF [86] introduces cross-layer weighted integration while adding a high-resolution P2 layer to enhance micro-object detection.

- C.

- Lightweight Neck Variants for Embedded and UAV Platforms

To reduce computation on embedded platforms, Slim-FPN [36] replaces YOLOv5-N’s neck with depthwise separable designs (DSC, DSSconv, DSSCSP, SCSAconv, SCSACSP), combining efficient convolution and attention for lightweight fusion. In [89], the EMA and FF modules capture cross-scale dependencies for UAV imagery, while the SCF module optimizes bottleneck placement. The CSPPartialStage from [38] further strengthens spatial information aggregation in complex aerial contexts.

AFPN [61] mitigates feature degradation across scales by stabilizing hierarchical interactions, whereas [40] proposes Triple Cross-Criss FPN (TCFPN), introducing a bidirectional residual mechanism for richer multi-scale integration and a feature aggregation module that compresses and redistributes spatial features.

- D.

- Detection-Oriented Modifications for Small and Tiny Objects