Synthetic Data Generation for AI-Based Quality Inspection of Laser Welds in Lithium-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methods

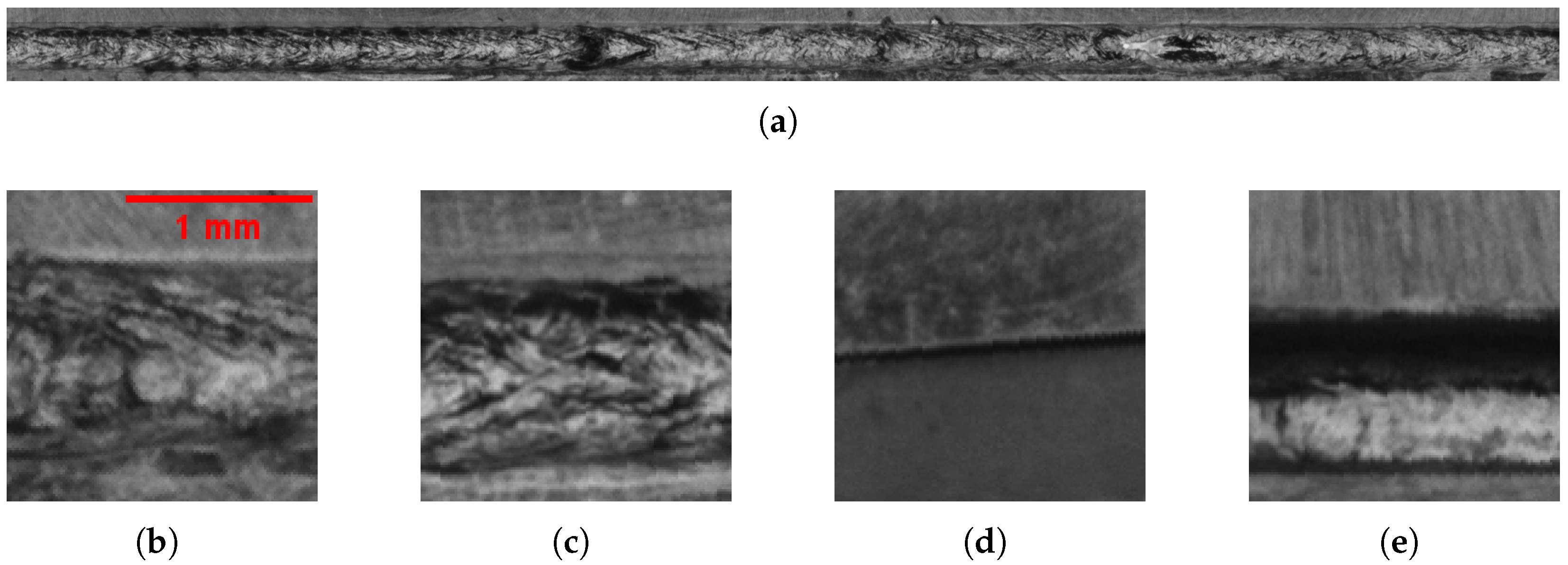

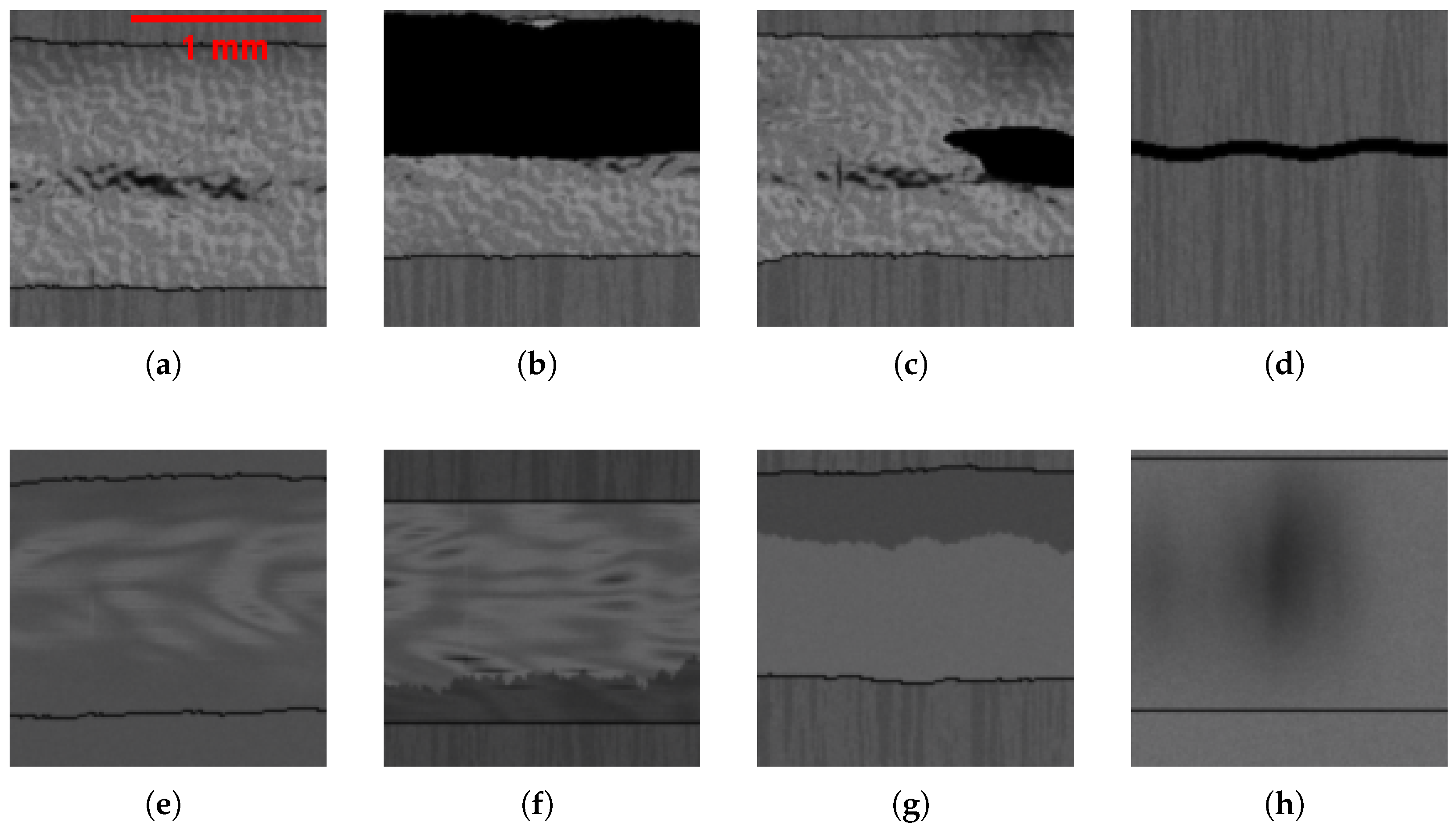

3.1. Real Image Recording Setup

3.2. Real Dataset

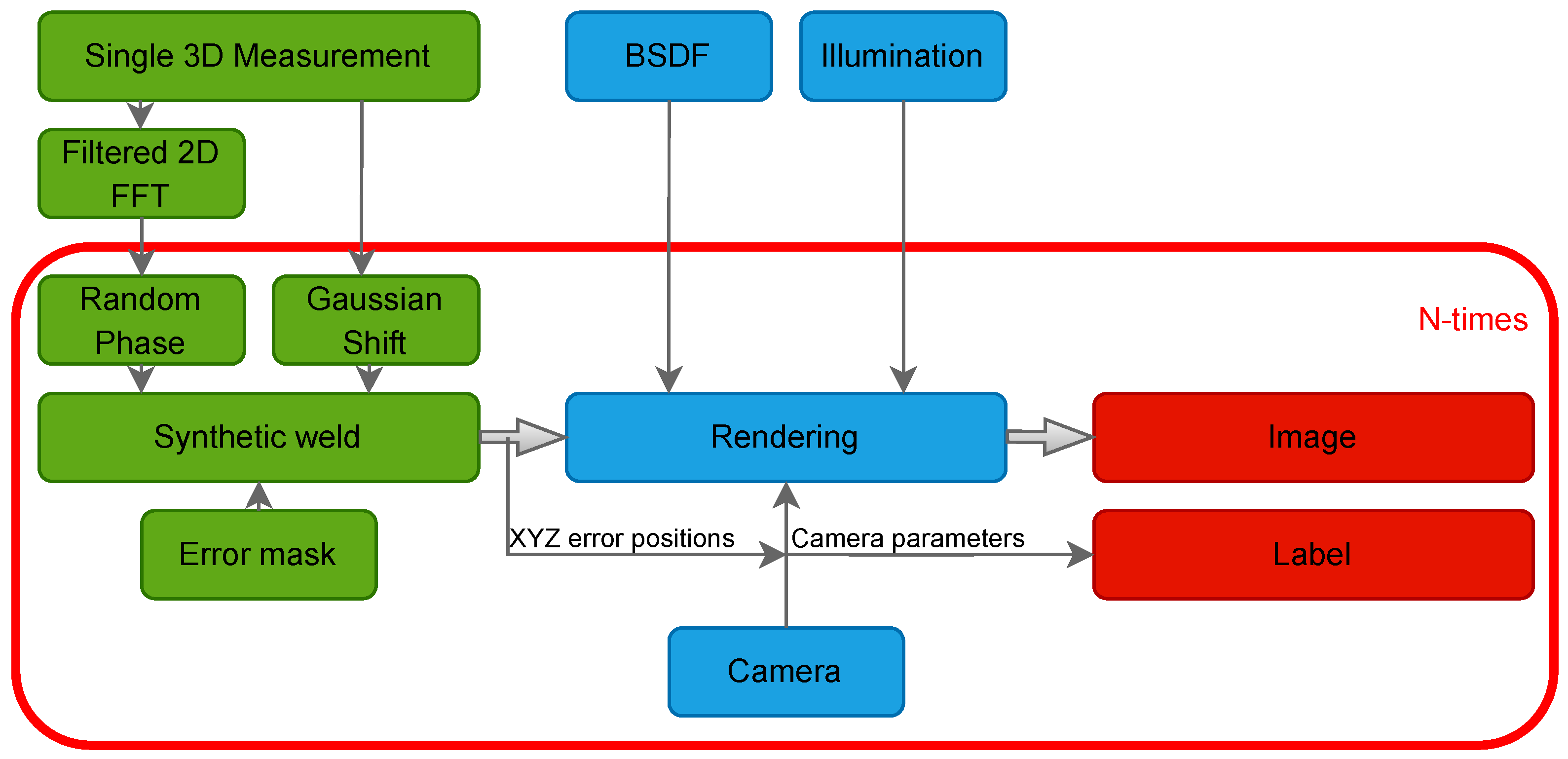

3.3. Generation of Synthetic Welds

3.4. Insert Variance into the Weld Images

- modeled weld topography

- reduced weld edge heights

- random border contour

- Perlin noise

- weld partner surface variances

- modeled soot on weld

- modeled soot at edges of weld

- modeled illumination

3.4.1. Geometry Based

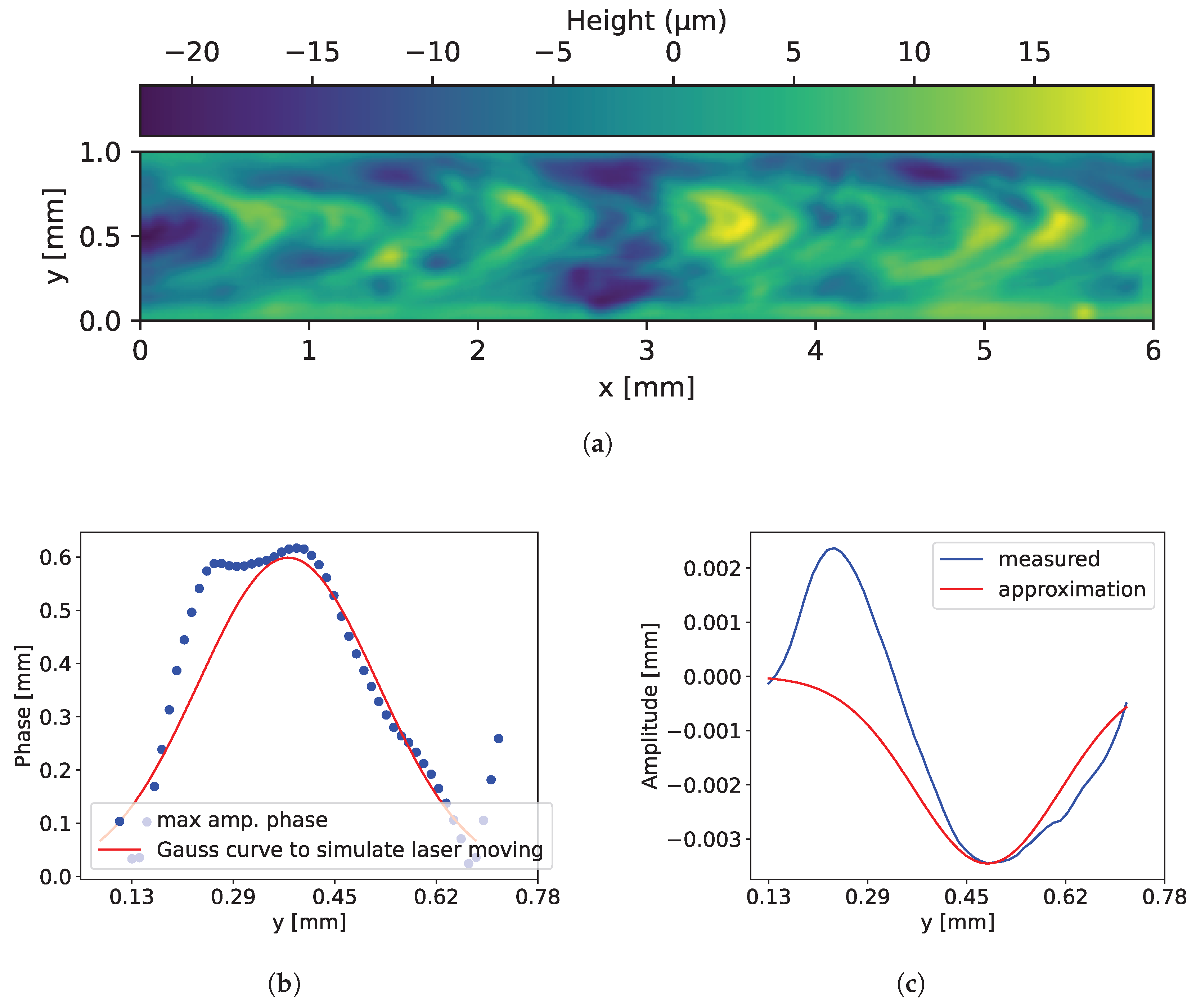

Modeled Weld Topography

Reduced Weld Edge Heights

Random Border Contour

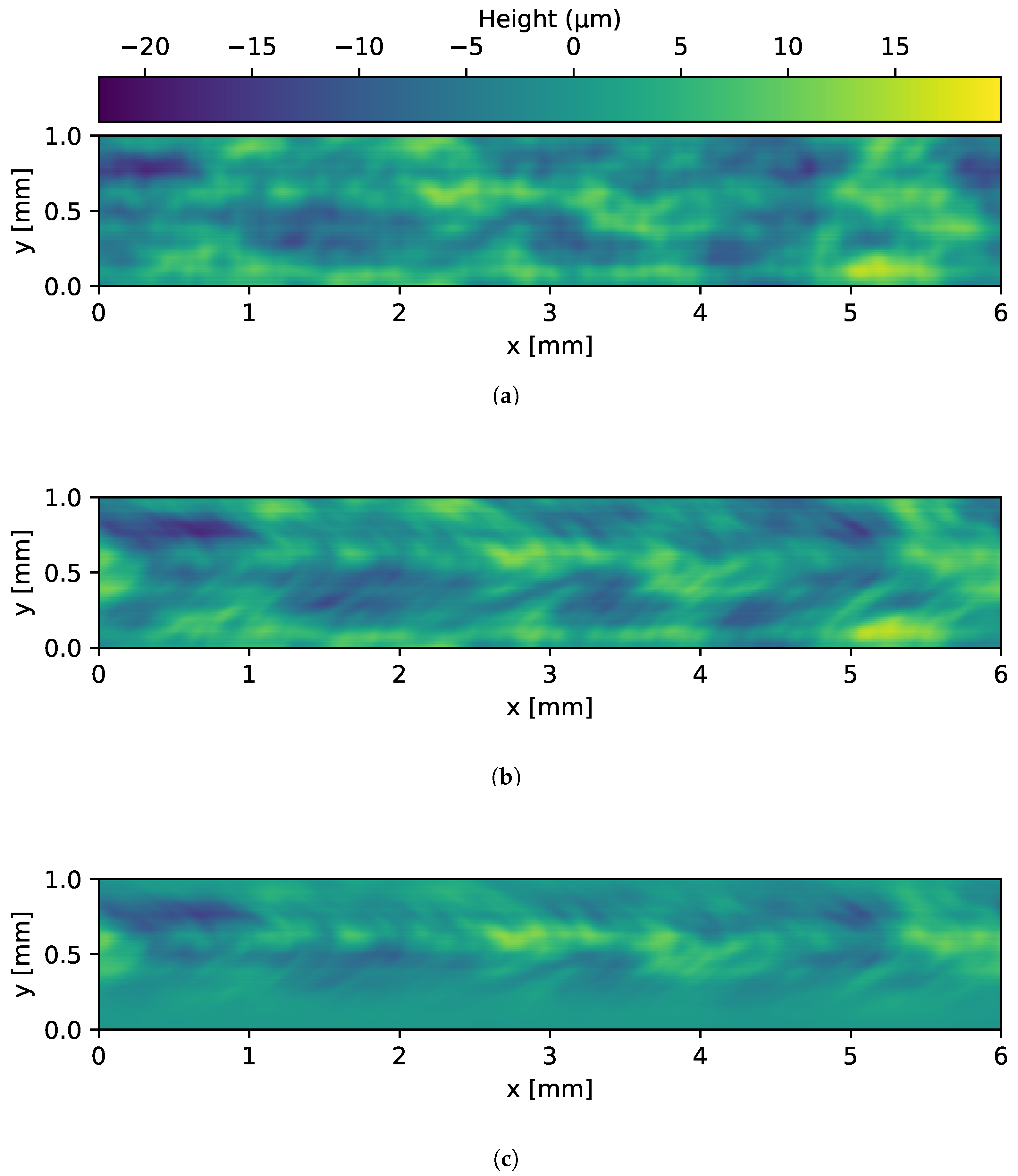

Perlin Noise

3.4.2. BSDF-Based

Weld Partner Surface Variance

Modeled Soot on Weld

Modeled Soot at Edges of Weld

3.5. Weld Error Generation

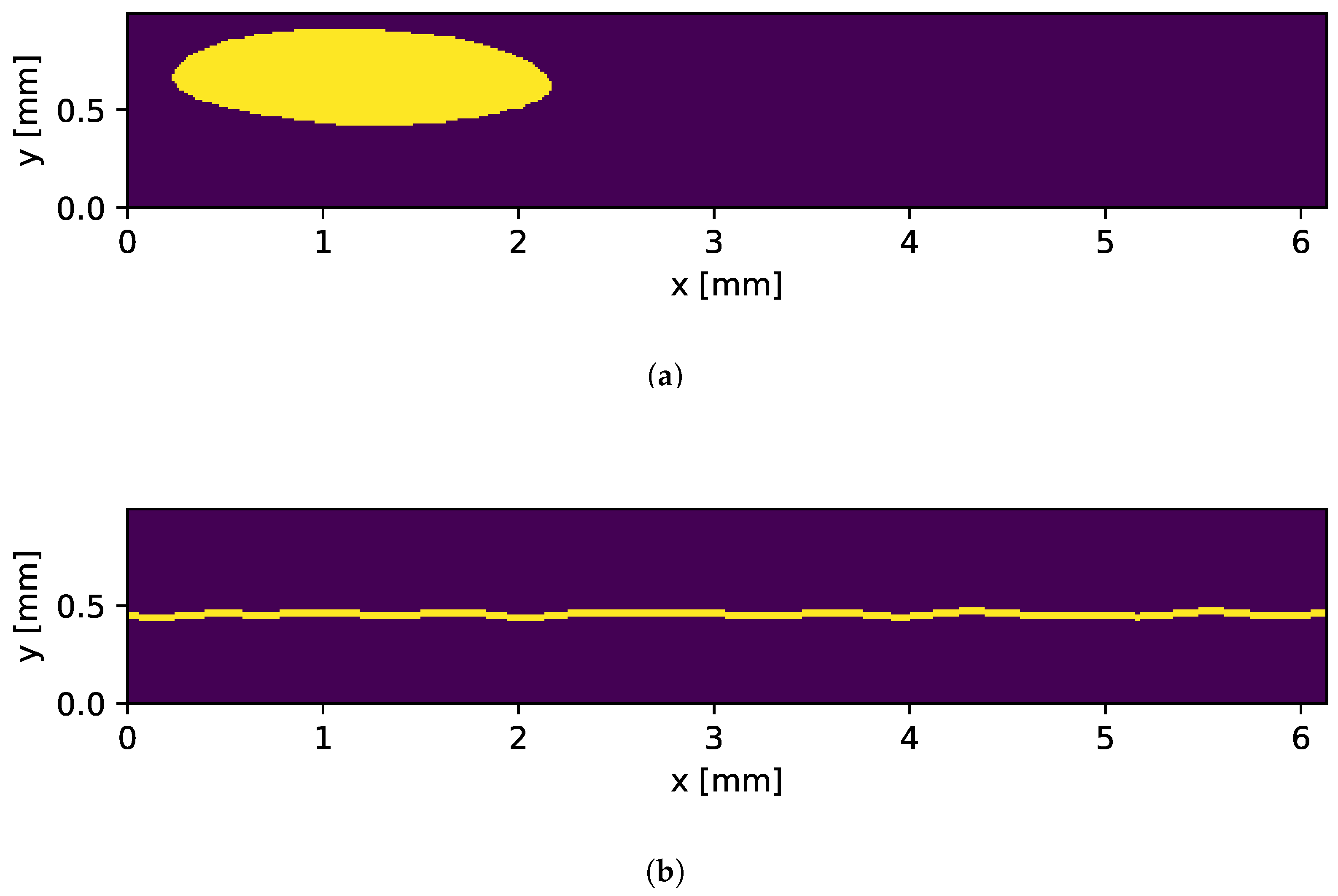

3.5.1. Hole

3.5.2. Missing Weld

4. Rendering

4.1. Bsdf Parametrization

4.2. Illumination Condition

4.3. Automated Labeling

5. Neural Network

6. Synthetic Dataset

7. Training

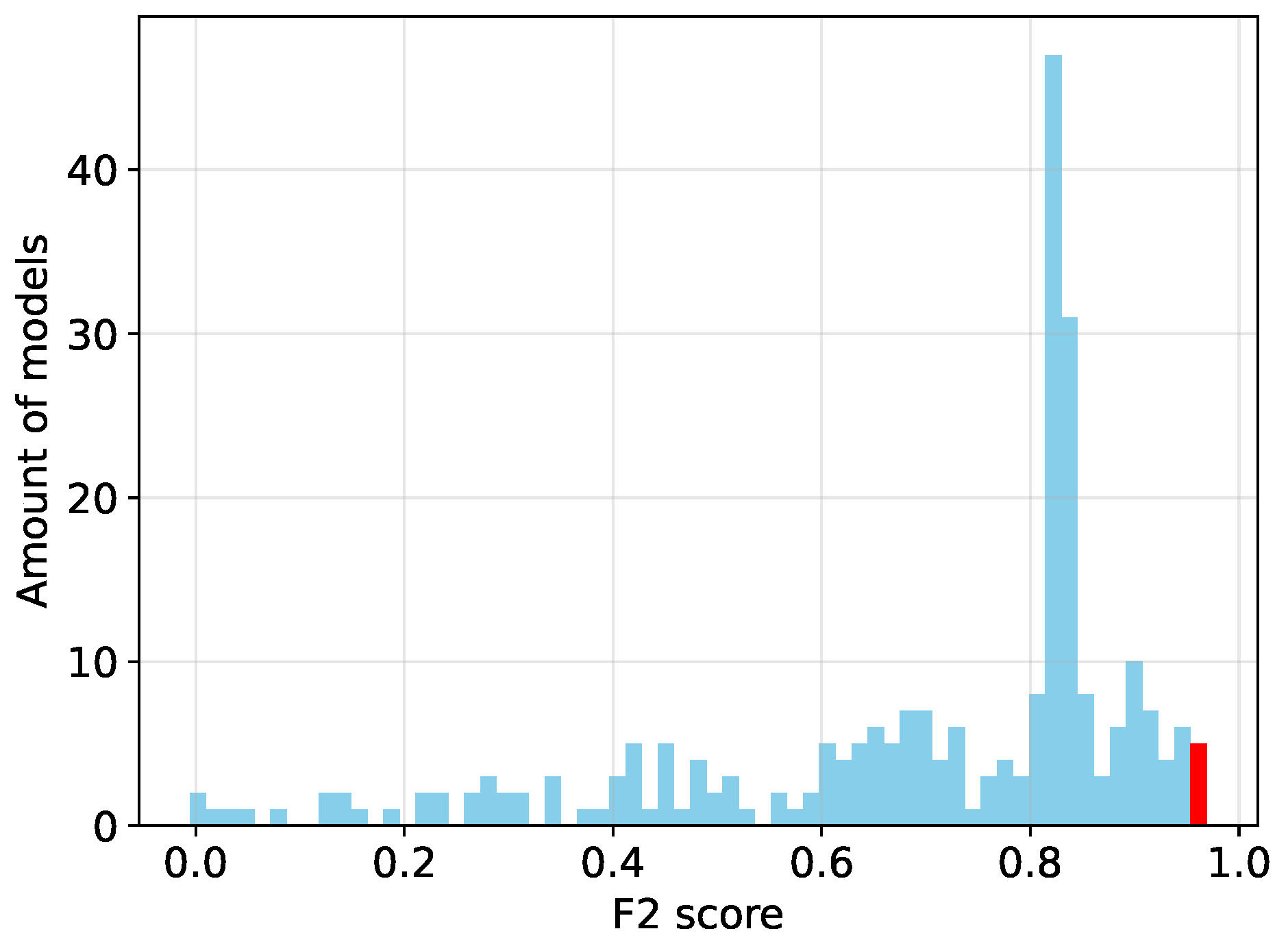

8. Results

8.1. Desired Test Metrics

8.2. Test Metrics of Trained Networks

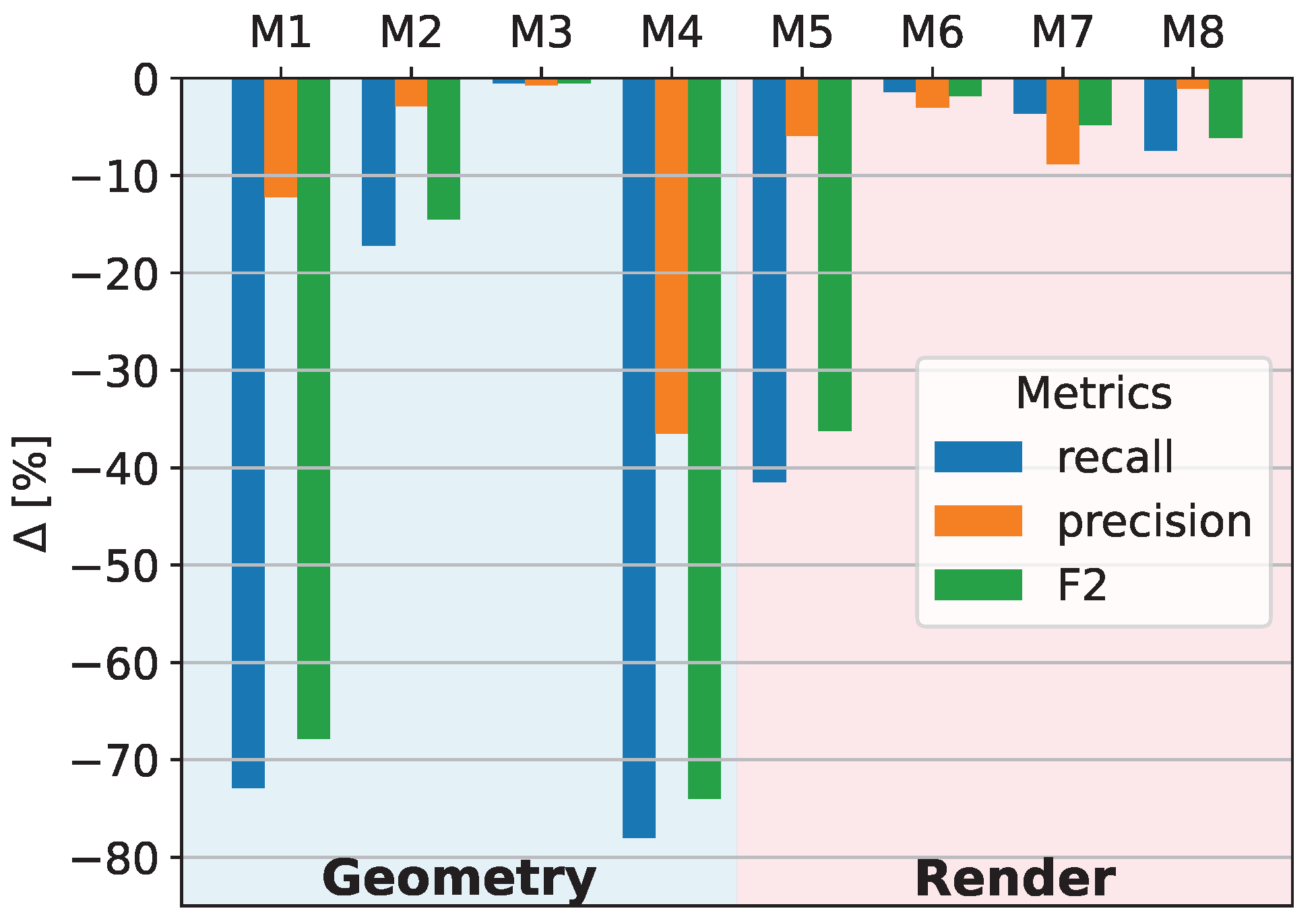

8.3. Sensitivity Study on Modeling and Rendering Parameters

- Accurate modeling of weld topography with high variance;

- Inclusion of Perlin noise to simulate weld discontinuities;

- Correct simulation of illumination conditions.

| Weld Topography | Reduced Weld Edges | Random Contour | Perlin Noise | Modeled Illumination | Partner Variances | Soot on Weld | Soot at Edges | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| best model | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ◦ |

| M1 | ◦ | • | • | • | • | • | • | ◦ |

| M2 | • | ◦ | • | • | • | • | • | ◦ |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

| M8 | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

9. Conclusions

10. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSDF | Bidirectional Scattering Distribution Function |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| PBR | Physically Based Rendering |

References

- Yang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Dong, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, S. Using deep learning to detect defects in manufacturing: A comprehensive survey and current challenges. Materials 2020, 13, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Heinzel, S.; von Bischhoffshausen, J.K.; Kühl, N. Deep learning strategies for industrial surface defect detection systems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.11304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähler, F.; Schmedemann, O.; Schüppstuhl, T. Anomaly detection for industrial surface inspection: Application in maintenance of aircraft components. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoepflin, D.; Holst, D.; Gomse, M.; Schüppstuhl, T. Synthetic training data generation for visual object identification on load carriers. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaidon, A.; Lopez, A.; Perronnin, F. The reasonable effectiveness of synthetic visual data. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2018, 126, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Ramirez, D.; Baez-Lopez, Y.; Limon-Romero, J.; Tortorella, G.; Tlapa, D. An assessment of human inspection and deep learning for defect identification in floral wreaths. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, J.E. Visual inspection reliability for precision manufactured parts. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 1427–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütten, N.; Alves Gomes, M.; Hölken, F.; Andricevic, K.; Meyes, R.; Meisen, T. Deep learning for automated visual inspection in manufacturing and maintenance: A survey of open-access papers. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožanec, J.M.; Trajkova, E.; Dam, P.; Fortuna, B.; Mladenić, D. Streaming Machine Learning and Online Active Learning for Automated Visual Inspection. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimpel, A. Review and analysis of modern laser beam welding processes. Materials 2024, 17, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Luo, J.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Veiko, V.P.; Duan, J. Ultrafast laser welding of transparent materials: From principles to applications. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, N.U.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y. Laser welding defects detection in lithium-ion battery poles. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 46, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, W.; Tang, D.; Peng, Y. Deep network-assisted quality inspection of laser welding on power Battery. Sensors 2023, 23, 8894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.; Yan, Z.; Xu, T.; Li, S.; Duan, R.; Peng, M. Rapid visual detection of laser welding defects in bright stainless steel thin plates. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 035203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Din, N.U.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, L. An improved YOLOv5 model for detecting laser welding defects of lithium battery pole. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boikov, A.; Payor, V.; Savelev, R.; Kolesnikov, A. Synthetic data generation for steel defect detection and classification using deep learning. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulir, J.; Bosnar, L.; Hagen, H.; Gospodnetić, P. Synthetic data for defect segmentation on complex metal surfaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 4424–4434. [Google Scholar]

- Hermens, F. Automatic object detection for behavioural research using YOLOv8. Behav. Res. Methods 2024, 56, 7307–7330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, J.W.; Tukey, J.W. An Algorithm for the Machine Calculation of Complex Fourier Series. Math. Comput. 1965, 19, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.S.; Musgrave, F.K.; Peachey, D.; Perlin, K.; Worley, S. Texturing and Modeling: A Procedural Approach; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.W.; Gao, X.D.; Gao, P.P.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.X. Laser welding monitoring techniques based on optical diagnosis and artificial intelligence: A review. Adv. Manuf. 2025, 13, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharr, M.; Jakob, W.; Humphreys, G. Physically Based Rendering: From Theory to Implementation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolenko, S.I. Synthetic Data for Deep Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 174. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfiqar, A.; Muhammad Daudpota, S.; Shariq Imran, A.; Kastrati, Z.; Ullah, M.; Sadhwani, S. Synthetic Image Generation Using Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Comput. Intell. 2024, 40, e70002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Mahmoud, Q.H. A systematic review of synthetic data generation techniques using generative AI. Electronics 2024, 13, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Hellsten, J.; Laine, S.; Lehtinen, J.; Aila, T. Training generative adversarial networks with limited data. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 12104–12114. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, B.; Marschner, S.R.; Li, H.; Torrance, K.E. Microfacet Models for Refraction through Rough Surfaces. Render. Tech. 2007, 2007, 18th. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Xu, L.; Chen, X.; Zheng, F.; Liu, Y. Chi-Squared Distance Metric Learning for Histogram Data. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 352849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, R.; Raja, K.; Ramachandra, R. A Likelihood Ratio Classifier for Histogram Features. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Biometrics Theory, Applications and Systems (BTAS), Redondo Beach, CA, USA, 22–25 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Asha, V.; Bhajantri, N.U.; Nagabhushan, P. GLCM–based chi–square histogram distance for automatic detection of defects on patterned textures. Int. J. Comput. Vis. Robot. 2011, 2, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Deboeverie, F.; Slembrouck, M.; Van Haerenborgh, D.; Van Cauwelaert, D.; Veelaert, P.; Philips, W. Extrinsic calibration of camera networks using a sphere. Sensors 2015, 15, 18985–19005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, S.; Louis-Dupont; Masad, O.; Yurkova, K.; Fridman, L.; Lkdci; Khvedchenya, E.; Rubin, R.; Bagrov, N.; Tymchenko, B.; et al. Super-Gradients. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.7789328 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Glenn Jocher and Jing Qiu YOLO by Ultralytics. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Roth, K.; Pemula, L.; Zepeda, J.; Schölkopf, B.; Brox, T.; Gehler, P. Towards total recall in industrial anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14318–14328. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Yin, J.; Huang, F.; Li, Q. Surface defect inspection of industrial products with object detection deep networks: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L. Metal surface defect detection using modified YOLO. Algorithms 2021, 14, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edna, C.T.; Li, Y.; Sam, N.; Liu, Y. A comparative study of fine-tuning deep learning models for plant disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 161, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosinski, J.; Clune, J.; Bengio, Y.; Lipson, H. How transferable are features in deep neural networks? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 3320–3328. [Google Scholar]

| # | Model Name | Train | P | R | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | YOLO NAS S | Synth | 0.487 | 0.833 | 0.729 |

| 2 | YOLO NAS S | Real | 0.955 | 0.958 | 0.956 |

| 3 | YOLOv11 Class. | Synth | 0.939 | 0.987 | 0.977 |

| 4 | YOLOv11 Class. | Real | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Weld Topography | Reduced Weld Edges | Random Contour | Perlin Noise | Modeled Illumination | Partner Variances | Soot on Weld | Soot at Edges | R | P | F2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) best model | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | ◦ | 0.987 | 0.939 | 0.977 |

| (2) core model | • | ◦ | ◦ | • | • | ◦ | ◦ | ◦ | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.976 |

| (3) topography model | • | ◦ | ◦ | ◦ | • | ◦ | ◦ | ◦ | 0.557 | 0.943 | 0.607 |

| (4) Perlin model | ◦ | ◦ | ◦ | • | • | ◦ | ◦ | ◦ | 0.898 | 0.561 | 0.802 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zender, J.; Maier, S.; Herkommer, A.; Layh, M. Synthetic Data Generation for AI-Based Quality Inspection of Laser Welds in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sensors 2025, 25, 7301. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237301

Zender J, Maier S, Herkommer A, Layh M. Synthetic Data Generation for AI-Based Quality Inspection of Laser Welds in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7301. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237301

Chicago/Turabian StyleZender, Jonathan, Stefan Maier, Alois Herkommer, and Michael Layh. 2025. "Synthetic Data Generation for AI-Based Quality Inspection of Laser Welds in Lithium-Ion Batteries" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7301. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237301

APA StyleZender, J., Maier, S., Herkommer, A., & Layh, M. (2025). Synthetic Data Generation for AI-Based Quality Inspection of Laser Welds in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sensors, 25(23), 7301. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237301