1. Introduction

Soybeans (Glycine max) represent one of the world’s most economically significant crops, serving as a primary source of protein and oil for global food and feed systems. Soybean oil accounts for over 25% of global vegetable oil production, ranking as the second-largest vegetable oil globally after palm oil [

1]. The crop’s global importance stems from its unique nutritional composition, containing 40–41% protein and 8.1% to 24.0% oil content, making it particularly valuable for both human consumption and animal feed applications [

2]. Soybeans are processed into numerous products across food, feed, and industrial sectors, with traditional and modern applications ranging from industrial applications to functional foods with cardiovascular health benefits [

3]. The major producing countries—the United States, Brazil, and Argentina—collectively account for approximately 82% of global soybean production, with approximately 98% of globally produced soybean meal utilized for animal nutrition [

4].

In the United States, soybeans represent the second-largest row crop by area and economic value, with significant agricultural and economic impact. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (2024) reports that in 2023, 33.8 million hectares of soybeans were planted, producing 4.16 billion bushels with a total crop value exceeding USD 60.7 billion, with projections for record-high production of 4.6 billion bushels in 2024/25 [

5,

6,

7]. More than 80% of U.S. soybeans are grown in the northern Midwest region, with Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, and Indiana as the top four producing states—collectively accounting for over 49% of the annual U.S. supply [

4]. The economic significance is further demonstrated by the 2023 production of 48 million metric tons of soybean meal valued at USD 498.14 per metric ton and 11.9 million metric tons of soybean oil at USD 1,439 per metric ton [

4].

Soybean growth is divided into two main stages: vegetative (V) and reproductive (R) [

8]. The vegetative stage covers early plant development (VE - VN), starting from seedling emergence (VE) through the formation of successive nodes and leaves. In the VE (emergence) stage, soybean development begins by breaking through the soil (Germinating) under three adequate conditions: soil moisture, temperature, and oxygen [

8]. By VC (cotyledon stage), the first unifoliolate leaves are fully open, marking the start of true leaf growth. At each subsequent stage, V1, V2, V3, VN (N number of nodes on the main stem), and so on, correspond to the number of fully expanded and unrolled trifoliolate leaves on the main stem. This continues until the plant reaches its final vegetative stage.

The reproductive stage starts at R1 (beginning bloom) when the first flower appears on the main stem, followed by R2 (full bloom) when the flowers are visible at the upper nodes. The plant then transitions to R3 (beginning pod) with pods of 3/16 inch long, and R4 (full pod), where small green pods of 3/4 inch long form and grow to full size [

8]. At R5 (beginning seed), seeds of 1/8 inch long start to develop inside the pods, and by R6 (full seed), they fill the pod cavity, where the pods appear plump with fully filled green seeds [

8]. When the plant reaches R7 (beginning maturity), at least one pod turns yellow-brown, signaling the start of drying and physiological maturity. The leaves may start yellowing and dropping at this stage. Finally, at R8 (full maturity), nearly all pods have reached their mature color, and the plant is ready for harvest. Usually, 5 to 10 days of good drying weather after R8 are needed before harvest, when seeds have less than 15% moisture.

The accurate identification of soybean growth stages is critical for optimizing pesticide and herbicide applications, as mistimed treatments can result in yield losses ranging from 2.5% to 40% and economic penalties of USD 5–80 per acre, depending on weed density and timing [

9]. Research demonstrates that herbicides must be applied at V3–V4 stages to achieve effective weed control, with delays beyond V4 causing exponential yield losses—particularly under high weed pressure, where applications at V4 already result in up to 25% yield loss [

9]. For insecticides, the optimal windows are equally narrow: soybean aphid control is most effective when applied at the R2–R3 growth stages once populations reach the economic threshold of 250 aphids per plant [

10], while stink bug management requires applications during the reproductive growth stages—when adults and nymphs colonize pods and developing seeds—which are key to preventing pod loss, seed deformation, and yield decline [

11]. These precise intervention windows underscore that growth stage identification is not merely a best practice but an essential skill for profitable and sustainable soybean production.

Deep learning has emerged as a transformative tool in agricultural phenotyping, particularly for recognizing plant growth stages. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown strong performance when applied to RGB images captured by UAVs, smartphones, and stationary cameras. These models can learn stage-specific visual cues—such as changes in leaf texture, shape, and canopy structure—and have been used to detect and classify growth stages ranging from seedling emergence to reproductive development. As the cost of aerial imaging and computing continues to decrease, the deployment of such models in real-world settings has become increasingly feasible across multiple crops.

The advancement of affordable imaging sensors has played a key role in enabling automated phenological monitoring and transforming smart agriculture globally [

12,

13]. Modern RGB camera sensors, including those integrated in smartphones and UAV-mounted cameras, provide high-resolution imagery suitable for growth stage detection at costs that are orders of magnitude lower than specialized agricultural sensors [

14]. Recent AI-powered aerial imaging systems utilizing these RGB sensors have achieved over 90% accuracy in identifying crop diseases and developmental stages [

15]. When combined with edge computing platforms equipped with GPUs and AI processing capabilities, these imaging sensors enable distributed monitoring networks that can operate autonomously in field conditions, supporting precision monitoring, early crop health diagnostics, yield forecasting, and data-driven decision support [

13].

The integration of RGB imaging sensors with complementary sensor modalities represents a transformative direction for comprehensive crop monitoring systems. Hyperspectral sensors, capturing hundreds of narrow spectral bands beyond visible light, enable AI models to detect subtle biochemical stress indicators such as water stress or nitrogen deficiencies that RGB imagery cannot discern, greatly improving crop health assessments and yield prediction accuracy [

15,

16]. Thermal imaging sensors provide canopy temperature measurements for water stress monitoring and irrigation optimization [

17,

18]. Networks of environmental IoT sensors measuring soil moisture, temperature, and humidity feed real-time data to AI platforms that predict optimal irrigation timing, forecast yields, and provide decision support for fertilizer and pest control measures [

19,

20,

21]. By fusing multi-source data from optical cameras, spectral sensors, and IoT devices, modern AI-driven farming systems deliver real-time, site-specific insights and recommendations, enabling early interventions that improve productivity and resource-use efficiency while promoting sustainability [

15,

21].

Object detection models based on CNNs have been used to identify growth stages in field and greenhouse settings across various crops and weeds [

22,

23]. An enhanced YOLOv4 model integrating DenseNet achieved high accuracy and speed in detecting different developmental stages of fruit in orchard environments, reaching a mean average precision (mAP) of 96.2% and F1-score of 93.6% at 44.2 FPS [

24]. UAV imagery of weed phenology was also processed using a suite of object detectors, where lightweight YOLOv5 models offered real-time performance, and RetinaNet attained an AP of 87.5% for stage-specific weed presence [

22]. In rice fields, an improved YOLOv8 model with a MobileNetv3 backbone and coordinate attention modules achieved a mAP of 84% on high-resolution UAV images [

25]. For horticultural crops such as strawberries, a YOLOX-based lightweight detector demonstrated near-perfect performance in identifying ripening stages using greenhouse images [

26]. These results confirm that state-of-the-art CNN detectors can localize and classify plant development stages with high accuracy and, in many cases, real-time speed.

Beyond object detection, CNN-based classifiers and segmentation models have been used for pixel-level labeling and sequence-based stage prediction. High-performing architectures such as VGG19 and DenseNet have been employed for general crop growth classification from field and time-lapse imagery, yielding consistently high accuracy [

27,

28]. A hybrid model combining ResNet34 with attention mechanisms was developed for maize and achieved over 98% classification accuracy on UAV orthophotos, further deployed as a web-based tool for field use [

29]. For finer pixel-level recognition, a U-Net-based segmentation model was enhanced to identify maize stages in the field, achieving a mean Intersection over Union (IoU) of 94.51% and pixel-level accuracy of 96.93% [

30]. Temporal models have also been integrated with CNNs; for instance, a ResNet50 + LSTM fusion model was used to classify wheat growth stages from time-series camera data, reaching 93.5% accuracy [

31]. These hybrid models illustrate the potential of combining spatial and temporal information for phenological classification.

Modern CNN-based models have been applied to soybean growth stage recognition, with a focus on optimizing both inference speed and accuracy. Lightweight variants of YOLOv5 have been trained to detect flowering and reproductive stages, often using UAV imagery with real-time performance targets. Pruned YOLOv5 architectures and attention-augmented backbones have demonstrated strong results for both in-field and edge-deployed phenology applications. In another line of research, over 44,000 strawberry images were used to train CNN classifiers for fine-grained seven-stage classification, achieving over 83% test accuracy with EfficientNet and similar models [

32]. These applications demonstrate the feasibility of deploying accurate and efficient CNNs across diverse environments, including field, greenhouse, and mobile platforms.

While recent advances in deep learning have improved the detection of certain soybean growth stages, most studies remain limited in scope, often targeting isolated phases such as early vegetative development. For example, early-stage detection efforts have utilized classical CNN architectures like AlexNet and its improved variants to classify VE (emergence), VC (cotyledon), and V1 (first trifoliolate) stages [

33]. However, these approaches do not leverage the capabilities of more recent and efficient architectures, such as transformer-based models or hybrid attention-enhanced CNNs, which offer greater accuracy and robustness in real-world applications.

In parallel, other research has focused on broader agronomic outcomes, including yield prediction based on pod detection [

34] or overall maturity estimation using aerial imagery and conventional machine learning classifiers such as random forests [

35]. While valuable, these studies do not provide stage-specific granularity across the full phenological timeline. As a result, there remains a significant gap in the literature for models that can comprehensively detect and classify all key soybean growth stages—from emergence and vegetative development to flowering, podding, and maturation—under varying environmental and imaging conditions. Addressing this gap is essential for advancing phenological monitoring, precision agriculture, and decision support systems in soybean production.

In prior work, a transformer-based model—SoyStageNet—was developed for the real-time classification of six early soybean growth stages (VE to VN) using RGB imagery captured in greenhouse conditions [

36]. While this approach demonstrated strong accuracy and efficiency in early-stage detection, it was limited in scope and did not address later developmental phases such as flowering, podding, and maturity. The present study extends this line of research by expanding the stage coverage to nine classes representing the full phenological cycle, and by designing a new lightweight architecture aimed at achieving state-of-the-art accuracy while preserving real-time inference performance in practical deployment scenarios.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

We present a comprehensive dataset of 17,204 labeled RGB images spanning nine complete soybean growth stages from emergence (VE) through full maturity (R8), addressing the limitation of existing datasets that focus only on isolated developmental phases.

We introduce DELTA-SoyStage, a novel object detection architecture combining an EfficientNet backbone with a lightweight ChannelMapper neck and the newly proposed DELTA (Denoising Enhanced Lightweight Task Alignment) detection head, achieving 73.9% AP with only 24.4 GFLOPs—4.2× fewer FLOPs than state-of-the-art baselines while maintaining competitive accuracy.

We conduct extensive ablation studies systematically evaluating task alignment mechanisms, multi-scale feature extraction strategies, and encoder–decoder depth configurations, providing insights into optimal architectural choices for agricultural detection applications.

Through computational analysis, we show that our architecture’s reduced FLOP requirements and compact parameter count position it for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices, potentially enabling timely agricultural decision-making without reliance on cloud infrastructure.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes our comprehensive soybean growth stage dataset collection methodology and annotation process.

Section 3 presents the proposed DELTA-SoyStage architecture, detailing the EfficientNet backbone, lightweight ChannelMapper neck, and novel DELTA detection head.

Section 4 provides implementation details and evaluation metrics.

Section 5 presents quantitative comparisons with state-of-the-art methods, extensive ablation studies validating our design choices, and qualitative analysis of detection results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with a discussion of limitations and future research directions.

2. Dataset

A total of 160 soybean seeds, comprising 20 seeds from each of eight different wild-type species, were planted in a controlled greenhouse environment. The seeds were specifically selected for their diverse phenotypic characteristics, including flower color, plant height, leaf shape and pod color. The greenhouse was maintained at a constant temperature of 27 °C to ensure optimal growth and germination conditions.

At the VC stage (cotyledon stage), seedlings were transplanted into individual pots. Irrigation was conducted every two to five days, adjusting frequency based on the plants’ growth phase. Slow-release fertilizers were applied at the R1 stage (beginning bloom) to promote healthy development. Simultaneously, image acquisition was performed using the RGB camera sensor of a Samsung Galaxy S20FE smartphone (Samsung Electronics, Suwon, Republic of Korea). Photos were taken from multiple angles in an orbiting pattern from the top, ensuring varied lighting conditions, backgrounds, and plant orientations to create a diverse and representative dataset.

Among the various species, PI567516C displayed notably accelerated growth, reaching late reproductive stages earlier than other accessions. During critical reproductive stages, irrigation frequency was increased to promote healthy pod development and seed filling. Once plants reached the R6 stage (full seed), watering was discontinued to prevent excessive moisture and facilitate proper seed drying and maturation.

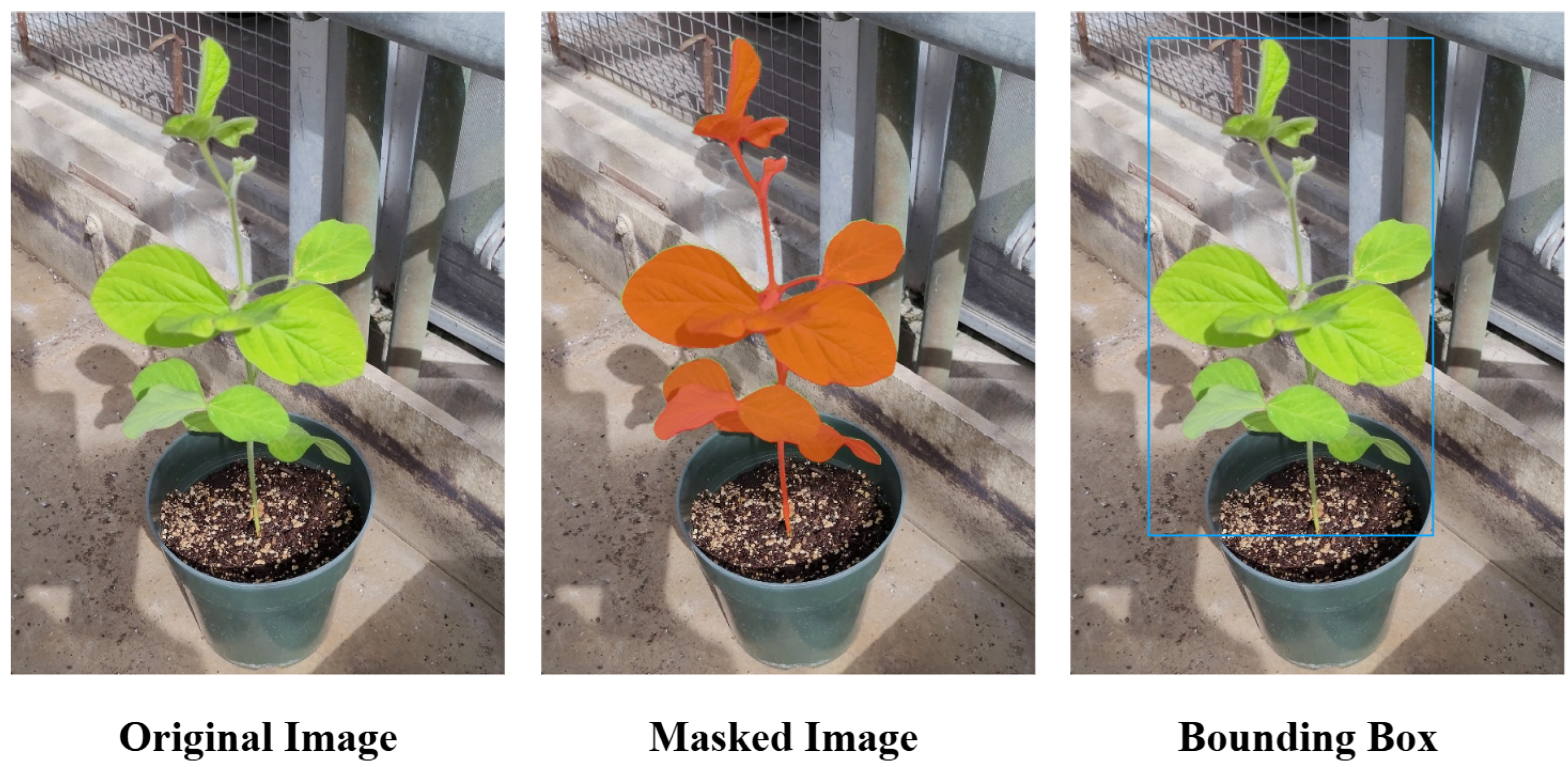

To ensure accurate and efficient annotations, we initially employed SAM2 (Segment Anything Model 2) [

37] for plant segmentation. However, SAM2 encountered challenges with precise segmentation due to varying backgrounds, inconsistent lighting conditions, and light reflections on leaf surfaces. Following initial segmentation, manual inspection and classification were conducted using LabelImg [

38] to ensure precise bounding boxes and correct class assignments for all images (

Figure 1).

Twenty-five soybean seeds from each of eight different wild-type species (200 plants total) were planted in a controlled greenhouse environment. Plants were monitored throughout their growth cycle, with video frames extracted every 40 frames to ensure temporal diversity and prevent data leakage from consecutive frames. The final dataset comprised 17,204 labeled images, with class distribution detailed in

Table 1. We used an 80/10/10 split—13,763 images for training, 1720 for validation, and 1721 for testing—ensuring a well-balanced learning process for effective generalization across different growth stages and background conditions.

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Results

Table 4 presents a comprehensive performance comparison across baseline detection methods and our proposed DELTA-SoyStage variants, encompassing multiple evaluation metrics for 12 model-backbone combinations. The baseline results demonstrate significant variations in both accuracy and computational efficiency across different architectural choices. DINO with Swin Transformer achieves strong performance with an AP of 74.7%, followed closely by DINO with ResNet-101 (74.4%). Among single-stage detectors, TOOD with ResNet-101 shows competitive performance (72.5% AP), while TOOD with Swin Transformer achieves 68.1% AP. Faster R-CNN, despite being a two-stage detector, shows moderate performance with the best result of 69.9% AP using the Swin Transformer backbone.

Regarding computational efficiency among baseline methods, the results reveal a clear trade-off between accuracy and model size. ResNet-based models maintain relatively compact parameter counts (32–60 M parameters), while Swin Transformer configurations require slightly more parameters (56–66 M) with substantially higher computational costs. The FLOP counts reflect this efficiency-accuracy trade-off, with lighter models requiring 28–52 GFLOPs compared to 44–102 GFLOPs for Swin Transformer configurations.

Our proposed DELTA-SoyStage variants, shown in the lower section of

Table 4, demonstrate exceptional computational efficiency while achieving highly competitive detection accuracy. DELTA-SoyStage with EfficientNet-B7 achieves 73.9% AP using only 24.4 GFLOPs, representing a 14% reduction in computational cost compared to the most efficient baseline (TOOD-ResNet-50: 28.5 GFLOPs) while delivering substantially superior accuracy (73.9% vs. 66.2%). More significantly, when compared to the best-performing baseline, DSS-B7 (DELTA-SoyStage B7) requires 4.2× fewer FLOPs than DINO-Swin (102.5 GFLOPs) for only 0.8% accuracy difference (74.7% vs. 73.9%), demonstrating that our architecture achieves near-state-of-the-art accuracy with dramatically reduced computational overhead.

The efficiency advantages extend across all model variants as demonstrated quantitatively in

Table 5. Our comprehensive efficiency analysis reveals that DSS-L achieves an exceptional 2.79× efficiency score compared to the high-accuracy baseline (DINO-Swin), while maintaining highly competitive accuracy within 0.8% of the best-performing model. When compared to methods of similar accuracy, DSS-L demonstrates 1.04× better efficiency than DINO-ResNet-50 and 1.27× better efficiency than TOOD-ResNet-101, validating our approach’s superior computational optimization. DSS-M achieves 70.3% AP with merely 15.2 GFLOPs, demonstrating an outstanding 4.76× efficiency score that outperforms all baseline methods while requiring 1.9× fewer FLOPs than the most efficient ResNet-based approaches. Most remarkably, our lightest variant DSS-S operates at an exceptional 8.7 GFLOPs while maintaining 65.7% AP, achieving an unprecedented 8.44× efficiency score that establishes a new efficiency frontier for agricultural detection applications.

The efficiency gains stem from our strategic focus on FLOP optimization rather than parameters reduction as evidenced by the 20/80 parameter/FLOP weighting used in our efficiency calculation. While DSS-L requires 70.5 M parameters compared to 41.5 M for DINO-ResNet-50, the dramatic FLOP reduction (24.4 G vs. 32.6 G) dominates the efficiency calculation, resulting in superior overall performance for edge deployment scenarios. This validates our architectural design choices, particularly the lightweight ChannelMapper neck and efficient encoder–decoder scaling in the DELTA head. The combination of EfficientNet’s compound scaling with our streamlined detection framework enables deployment on resource-constrained agricultural platforms without compromising detection quality essential for precision farming applications.

5.2. Ablation Study

To validate our architectural design choices and understand the contribution of individual components to overall performance, we conduct comprehensive ablation studies on our DELTA-SoyStage model variants. These experiments systematically isolate and evaluate specific design decisions to provide insights into the optimal configuration for agricultural edge deployment. Our ablation analysis focuses on three critical aspects of the DELTA-SoyStage architecture: the effectiveness of task alignment and adaptive noise mechanisms in the detection head, the impact of multi-scale feature extraction depth from the EfficientNet backbone, and the optimal encoder–decoder architecture scaling for transformer-based processing. Each study is conducted across all three DELTA-SoyStage variants (Small, Medium, Large) to ensure findings generalize across different model complexities and computational budgets. These ablations provide empirical justification for our design choices while identifying opportunities for further optimization in resource-constrained agricultural scenarios.

Task Alignment and Adaptive Noise Components: We ablate two DELTA head components—(i) task alignment, which reduces the classification–localization gap via task-specific feature decomposition, and (ii) adaptive noise, which modulates training noise to improve robustness. We systematically evaluate four configurations: both components enabled (True, True), task alignment only (True, False), adaptive noise only (False, True), and both disabled (False, False). This isolates their individual and joint effects, showing whether they are complementary or if one dominates, and clarifies the accuracy–complexity trade-off for resource-constrained agricultural deployments.

The task alignment and adaptive noise ablation reveals model size-dependent optimization patterns that provide important insights into component effectiveness across different architectural complexities. For the smallest variant (DSS-S), counterintuitively, disabling both components yields the best performance (65.9% AP) as shown in

Table 6, suggesting that the limited model capacity benefits from simplified training dynamics rather than sophisticated alignment mechanisms. This indicates potential overfitting or optimization difficulties when complex training strategies are applied to lightweight architectures.

The medium variant (DSS-M) demonstrates the most robust behavior, with both the full configuration (task alignment + adaptive noise) and adaptive noise alone achieving optimal 69.5% AP. This suggests that DSS-M represents a sweet spot where the model has sufficient capacity to benefit from training enhancements without suffering from optimization complexity. The consistent performance across configurations indicates stable training dynamics at this scale.

For the largest variant (DSS-L), the full configuration with both components enabled clearly outperforms all alternatives (72.3% AP vs. 70.8–71.9% for partial configurations), demonstrating that high-capacity models can effectively leverage sophisticated training mechanisms. The substantial performance degradation when both components are disabled (69.5% AP, a 2.8 percentage point drop) confirms that large models require advanced training strategies to reach their full potential.

These findings suggest an optimal component selection strategy based on deployment requirements: lightweight models (B3) benefit from simplified training, medium models (B5) show flexibility across configurations, and large models (B7) require full training enhancement for optimal performance. This has practical implications for agricultural deployment where different computational budgets may favor different DELTA-SoyStage variants with correspondingly adjusted training strategies.

Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Depth: This ablation examines the impact of incorporating additional shallow features from the EfficientNet backbone by expanding from three feature levels (stages 3, 4, 5) to four levels (stages 2, 3, 4, 5). The inclusion of stage 2 features provides finer spatial resolution (H/8 × W/8) that potentially benefits detection of small soybean plants in early growth stages, though at the cost of increased computational overhead and memory usage. Shallow features typically contain more spatial detail but less semantic information, making this trade-off particularly relevant for agricultural applications where plant size varies dramatically across growth stages. The four-level configuration increases the number of feature pyramid levels in the ChannelMapper neck, requiring additional channel normalization and processing. This study determines whether the enhanced spatial detail from stage 2 features justifies the computational cost increase, providing insights into the optimal balance between detection sensitivity for small objects and overall system efficiency.

The multi-scale feature extraction depth ablation definitively validates our design choice of using three feature levels (stages 3, 4, 5) over four levels (stages 2, 3, 4, 5) from the EfficientNet backbone. Across all DELTA-SoyStage variants, the inclusion of stage 2 features consistently degrades detection performance, with particularly severe impact on smaller models. DSS-S experiences the most dramatic performance loss (11.3 percentage points: 65.7% → 54.4% AP) as shown in

Table 7, indicating that lightweight architectures are especially sensitive to noisy shallow features that lack sufficient semantic content for effective object detection. The medium variant DSS-M shows moderate degradation (5.7 percentage points: 69.5% → 63.8% AP), while the large variant DSS-L demonstrates relative resilience with minimal performance loss (1.5 percentage points: 72.3% → 70.8% AP), suggesting that higher-capacity models can better handle suboptimal feature inputs but still benefit from the streamlined approach. The consistent performance degradation across all scale-specific metrics (AP

S, AP

M, AP

L) confirms that stage 2 features provide insufficient semantic information to justify their computational overhead and potential optimization difficulties. These results align with established computer vision principles that shallow features, while containing fine spatial detail, often introduce noise and computational burden without corresponding accuracy benefits in object detection tasks. This ablation empirically justifies our architectural decision to exclude stage 2 features, supporting our efficiency-focused design philosophy while maintaining optimal detection accuracy for agricultural applications.

Encoder–Decoder Architecture Scaling: This ablation investigates the optimal depth configuration for the transformer-based encoder and decoder components within our DELTA head. The encoder processes multi-scale features through self-attention mechanisms to capture global dependencies and enhance feature representations, while the decoder generates final detection predictions through cross-attention between learned queries and encoded features. We systematically vary the number of encoder and decoder layers to understand the trade-off between model capacity and computational efficiency. Deeper architectures typically provide enhanced representational power and improved handling of complex spatial relationships, but at the cost of increased parameters, computational load, and potential overfitting risk. For agricultural edge deployment, this balance is particularly critical as the model must achieve sufficient accuracy to distinguish subtle morphological differences between growth stages while maintaining real-time inference capabilities on resource-constrained hardware. This analysis identifies the minimal architecture depth required to achieve optimal performance, informing deployment decisions for various computational budget scenarios.

The encoder–decoder architecture depth ablation reveals distinct optimal configurations across DELTA-SoyStage variants, with our final selections prioritizing maximum detection accuracy essential for agricultural applications (

Table 8). For the small variant, DSS-S with 2 encoders and 1 decoder achieves optimal performance with 65.7% AP and the highest efficiency score of 8.45×, demonstrating that lightweight models benefit from streamlined architectures that avoid optimization difficulties associated with deeper transformer layers. The medium variant (DSS-M) shows nuanced behavior where DSS-M with 3 encoders and 1 decoder achieves the highest accuracy (70.3% AP) compared to the 2 encoder, 1 decoder configuration (69.5% AP), and we select this configuration for our final model despite slightly lower efficiency (4.76× vs. 5.29×), as the 0.8% accuracy improvement is significant for agricultural detection tasks. For the large variant, DSS-L with 3 encoders and 3 decoders delivers peak accuracy (73.9% AP), substantially outperforming the minimal 2-encoder, 1-decoder setup (72.3% AP), and we adopt this as our final configuration prioritizing the 1.6% accuracy gain over the efficiency difference (2.79× vs. 3.01×). Notably, 4-encoder configurations consistently underperform across all variants, with DSS-L with 4 encoders and 1 decoder showing catastrophic accuracy degradation (56.2% AP), indicating that excessive encoder depth leads to optimization instability.

Final Architectural Configuration and Deployment Recommendations Based on our comprehensive ablation studies, we establish variant-specific optimal configurations that integrate encoder–decoder depth, training strategy, and feature extraction findings. Our accuracy-optimized selections are: DSS-S with 2 encoders, 1 decoder, simplified training (no task alignment/adaptive noise), and three-stage features (stages 3–5) achieving 65.7% AP; DSS-M with 3 encoders, 1 decoder, full training enhancement, and three-stage features achieving 70.3% AP; DSS-L with 3 encoders, 3 decoders, full training enhancement, and three-stage features achieving 73.9% AP.

For deployment scenarios prioritizing computational efficiency—such as edge devices, agricultural robots, or real-time monitoring systems with limited processing capabilities—we recommend alternative configurations. DSS-M can adopt 2 encoders and 1 decoder, achieving 69.5% AP with 5.29× efficiency (versus 70.3% AP and 4.76× efficiency), trading only 0.8% AP for 11.1% improved efficiency. DSS-L with 2 encoders and 1 decoder achieves 72.3% AP with 3.01× efficiency (versus 73.9% AP and 2.79× efficiency), sacrificing 1.6% AP for 7.9% efficiency gain. These efficiency-focused configurations maintain competitive performance while enabling deployment in resource-constrained environments where accuracy-optimized variants would be impractical. The choice between configurations depends on specific application requirements, with both thoroughly validated through our ablation studies.

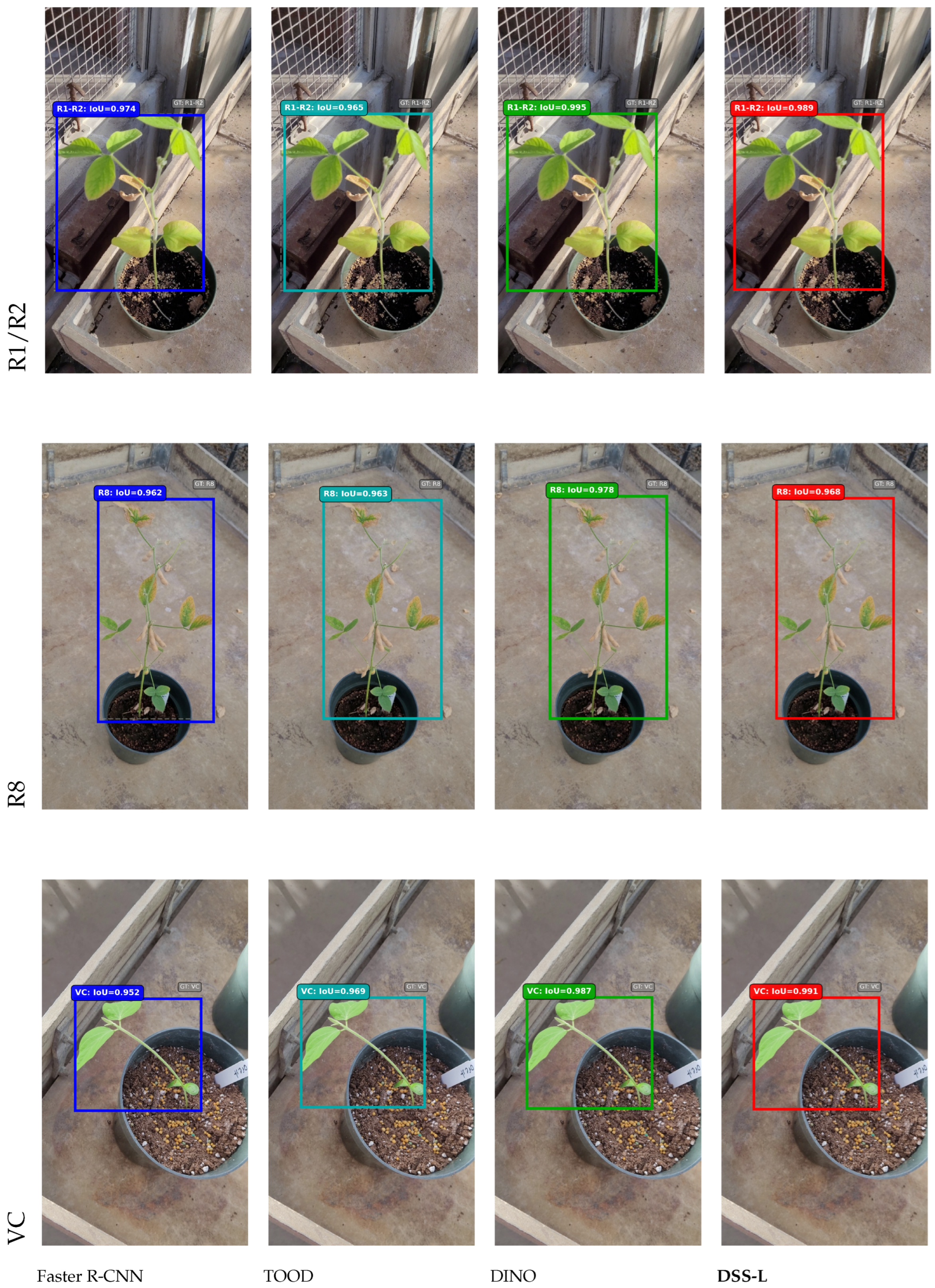

5.3. Qualitative Analysis

Figure 3 presents qualitative detection results comparing DSS-L with state-of-the-art models across three representative soybean growth stages (R1–R2, R8, and VC). Faster R-CNN consistently displays perfect confidence scores (1.00) across all stages, which may indicate calibration issues despite high IoU values. TOOD demonstrates strong performance on early and late stages but shows notably reduced confidence on the R1–R2 flowering stage (0.829), suggesting difficulties in distinguishing subtle morphological features during reproductive transitions. DINO achieves the most competitive performance with IoU values ranging from 0.978 to 0.995, representing the strongest baseline for comparison.

DSS-L achieves highly competitive detection quality with IoU values ranging from 0.968 to 0.991 and well-calibrated confidence scores (0.907–0.945) across all growth stages. Notably, DSS-L attains the highest IoU (0.991) on the VC vegetative stage, outperforming all baselines including DINO (0.987). On the challenging R1–R2 flowering stage, DSS-L achieves 0.989 IoU with 0.907 confidence, demonstrating robust performance on reproductive stages where precise detection timing is critical for agricultural interventions. These results demonstrate the ability of DSS-L to maintain detection quality comparable to substantially larger models while offering superior computational efficiency, making it well-suited for deployment in resource-constrained precision agriculture applications.