Balancing Cost and Precision: An Experimental Evaluation of Sensors for Monitoring in Electrical Generation Systems

Highlights

- The comparison demonstrates that low-cost devices are suitable only for general trend visualization, while high-precision sensors are required for accurate voltage and current measurements.

- Low-cost sensors exhibit deviations greater than 5%, whereas high-precision sensors maintain errors below 1% when monitoring generation systems.

- Accurate monitoring of generation systems depends on the use of high-precision sensors, particularly for performance assessment and operational decision-making.

- As PV adoption continues to grow, reliable sensing becomes critical for scalable, long-term monitoring solutions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup and Sensor Characterization Methodology

2.1. Sensor Comparison and Selection

2.2. Monitoring Board Design

2.2.1. Low-Cost Sensor Configuration

2.2.2. High-Precision Sensor Configuration

2.3. Signal-Processing Algorithm

2.3.1. RMS Calculation and Filtering

2.3.2. Data Transmission to the Database

2.4. Sensor Characterization

2.4.1. High-Precision Sensors Characterization

2.4.2. Extended Error Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Operation Under Cloudy Conditions

3.2. Operation Under Sunny Day Conditions

3.3. Operation Under Rainy Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, C.K.; Sahoo, S.K.; Yanine, F.F. A Literature Review on an IoT-Based Intelligent Smart Energy Management Systems for PV Power Generation. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 5, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwanrit, R.; Kittipiyakul, S.; Kudtonagngam, J.; Fujita, H. Accuracy Comparison of Present Low-Cost Current Sensors for Building Energy Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Embedded Systems and Intelligent Technology and International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Embedded Systems (ICESIT-ICICTES), Khon Kaen, Thailand, 7–9 May 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khozondar, H.J.; Mtair, S.Y.; Qoffa, K.O.; Qasem, O.I.; Munyarawi, A.H.; Nassar, Y.F.; Bayoumi, E.H.; Halim, A.A.E.B.A.E. A Smart Energy Monitoring System Using ESP32 Microcontroller. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 9, 100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, A.; Wester, M.; Lazarevic, D.; Brandt, N. Smart Homes, Home Energy Management Systems and Real-Time Feedback: Lessons for Influencing Household Energy Consumption from a Swedish Field Study. Energy Build. 2018, 179, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badar, A.Q.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Smart Home Energy Management System—A Review. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2022, 16, 118–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.O.; Elmarghany, M.R.; Hamed, A.M.; Sabry, M.N.; Abdelsalam, M.M. Optimized Smart Home Energy Management System: Reducing Grid Consumption and Costs through Real-Time Pricing and Hybrid Architecture. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64, 105410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, D.A.V.; Laureano, E.V.; Betancourt, R.O.J.; Alvarez, E.N. An Open Source IoT Edge-Computing System for Monitoring Energy Consumption in Buildings. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, N.; Farinango, P.; Estrada, R. Energy Consumption Monitoring and Prediction System for IT Equipment. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 241, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsigiannis, M.; Pantelidakis, M.; Mykoniatis, K.; Purdy, G. Current Monitoring for a Fused Filament Fabrication Additive Manufacturing Process Using an Internet of Things System. Manuf. Lett. 2023, 35, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Chowdhury, I.A. DATAEMS: Design and Development of a Data Analysis-Based Energy Monitoring System. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2023, 6, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Nunez, J.A.; Garcia-Barajas, L.M.; Hernandez-Gomez, J.D.J.; Serrano-Rubio, J.P.; Herrera-Guzman, R. Energy Monitoring Consumption at IoT-Edge. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Autumn Meeting on Power, Electronics and Computing (ROPEC), Ixtapa, Mexico, 13–15 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failing, J.M.; Abellan-Nebot, J.V.; Nacher, S.B.; Castellano, P.R.; Subiron, F.R. A Tool Condition Monitoring System Based on Low-Cost Sensors and an IoT Platform for Rapid Deployment. Processes 2023, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Sharma, H.; Haque, A. IoT Enabled Real-Time Energy Monitoring for Photovoltaic Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data, Cloud and Parallel Computing (COMITCon), Faridabad, India, 14–16 February 2019; pp. 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, A.N.; Hafeez, K.; Mnati, M.J.; Khan, S.A. Design and Implementation of New Battery Monitoring System for Photovoltaic Application. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM), Cappadocia, Turkey, 14–17 June 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescentini, M.; Syeda, S.F.; Gibiino, G.P. Hall-Effect Current Sensors: Principles of Operation and Implementation Techniques. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 10137–10151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H. Measuring Electronics and Sensors: Basics of Measurement Technology, Sensors, Analog and Digital Signal Processing; Springer Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; ISBN 978-3-658-35067-3. [Google Scholar]

| Sensor | Type | Range | Current Type | Accuracy | Galvanic Isolation | Output Signal | Cost (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZMPT101B | Voltage | 0–250 V | AC | 1% | No | Analog voltage (Proportional to input) | $5 |

| SCT-013 | Current | 0–20 A | AC | 1% | Yes | Analog voltage (Proportional to current) | $10 |

| HCPL-7800&OP127GSZ | Voltage | 0–180 V | DC/AC | 0.1% | Yes | Analog voltage (High linearity) | $18 |

| HXS20-NP | Current | ±20 A | DC/AC | 0.01% | Yes | Analog voltage | $25 |

| # | Current (IRMS) | Voltage (VRMS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | S1 | S2 | S3 | O | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| 1 | 4.92 | 4.49 | 4.43 | 4.42 | 91.85 | 112.00 | 99.67 | 91.49 |

| 2 | 4.61 | 4.31 | 4.25 | 4.23 | 87.22 | 88.84 | 86.71 | 83.11 |

| 3 | 4.51 | 4.24 | 4.17 | 4.16 | 84.62 | 86.27 | 85.50 | 84.11 |

| 4 | 4.14 | 4.02 | 3.95 | 3.94 | 78.31 | 76.38 | 81.43 | 76.89 |

| 5 | 3.95 | 3.91 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 74.17 | 73.66 | 78.55 | 74.28 |

| 6 | 3.66 | 3.73 | 3.64 | 3.65 | 69.27 | 68.65 | 78.73 | 66.83 |

| 7 | 3.46 | 3.59 | 3.50 | 3.52 | 64.99 | 71.41 | 71.30 | 62.31 |

| 8 | 3.17 | 3.38 | 3.27 | 3.31 | 60.08 | 61.59 | 68.14 | 57.86 |

| 9 | 2.96 | 3.19 | 3.04 | 3.13 | 55.62 | 53.56 | 65.52 | 52.85 |

| 10 | 2.68 | 2.84 | 2.70 | 2.82 | 50.87 | 48.82 | 61.17 | 47.98 |

| Sensor | MAE (A) | RMSE (A) | R2 | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.196 | 0.225 | 0.899 | 5.12 |

| S2 | 0.176 | 0.235 | 0.890 | 4.12 |

| S3 | 0.207 | 0.254 | 0.873 | 5.14 |

| Sensor | MAE (V) | RMSE (V) | R2 | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 3.852 | 6.839 | 0.732 | 4.99 |

| S2 | 6.074 | 6.996 | 0.719 | 9.49 |

| S3 | 1.951 | 2.311 | 0.969 | 2.97 |

| # | Current (IRMS) | Voltage (VRMS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | S1 | S2 | S3 | O | S1 | S2 | S3 | |

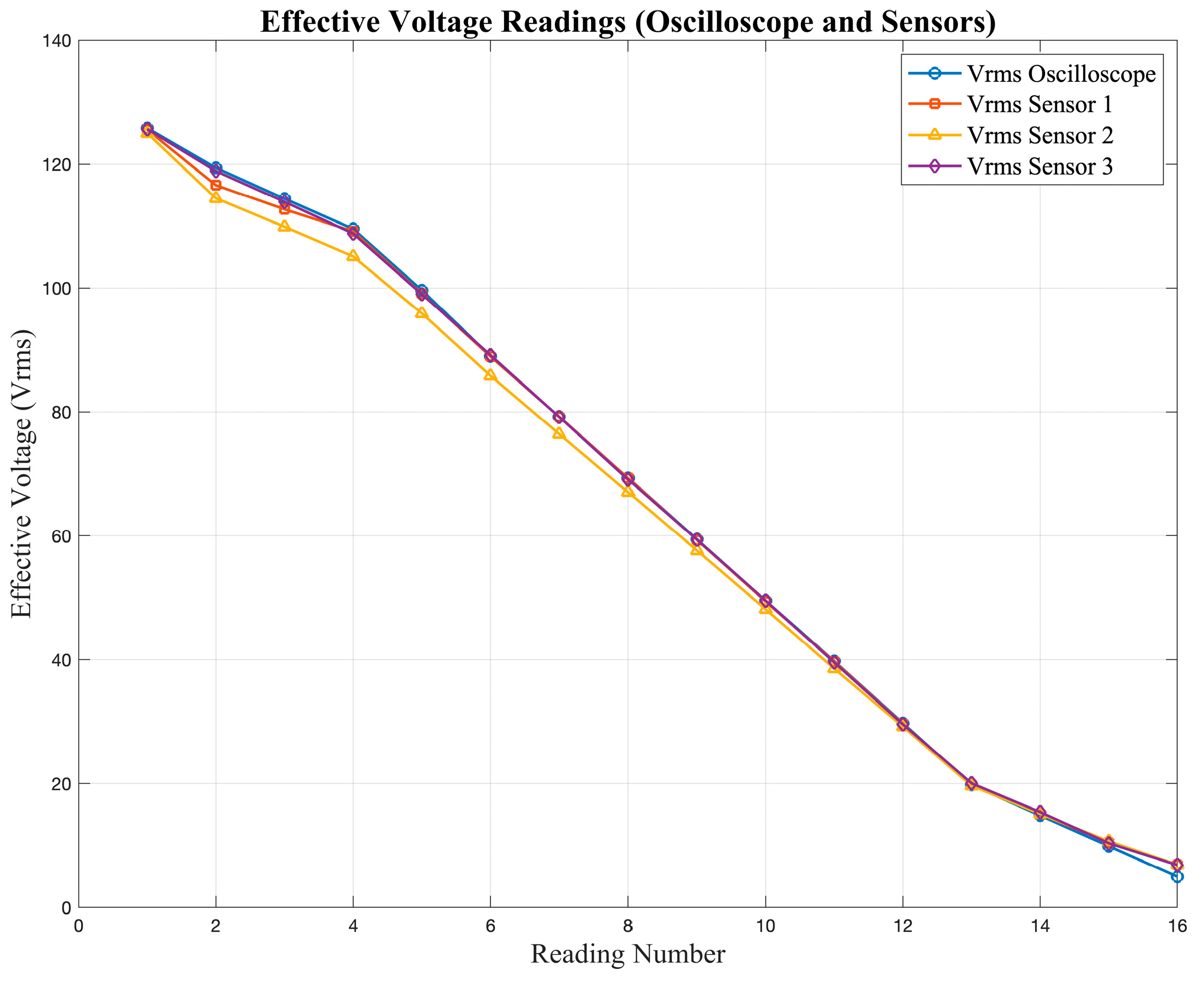

| 1 | 6.28 | 6.84 | 6.88 | 6.86 | 125.80 | 125.54 | 124.99 | 125.63 |

| 2 | 5.97 | 6.03 | 6.54 | 6.61 | 119.40 | 116.59 | 114.47 | 118.88 |

| 3 | 5.48 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 5.93 | 109.50 | 109.10 | 105.09 | 108.76 |

| 4 | 4.98 | 5.23 | 5.46 | 5.40 | 99.63 | 99.08 | 95.88 | 99.01 |

| 5 | 4.46 | 4.69 | 4.90 | 4.85 | 89.00 | 88.94 | 85.85 | 89.15 |

| 6 | 3.96 | 4.12 | 4.35 | 4.31 | 79.22 | 79.22 | 76.42 | 79.19 |

| 7 | 3.46 | 3.59 | 3.81 | 3.76 | 69.33 | 69.32 | 67.06 | 69.09 |

| 8 | 2.96 | 3.05 | 3.25 | 3.21 | 59.41 | 59.32 | 57.62 | 59.37 |

| 9 | 2.47 | 2.53 | 2.71 | 2.68 | 49.53 | 49.41 | 48.15 | 49.54 |

| 10 | 1.96 | 2.00 | 2.16 | 2.14 | 39.75 | 39.69 | 38.55 | 39.54 |

| Sensor | MAE (A) | RMSE (A) | R2 | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.185 | 0.237 | 0.972 | 4.03 |

| S2 | 0.408 | 0.408 | 0.908 | 9.78 |

| S3 | 0.377 | 0.404 | 0.918 | 8.90 |

| Sensor | MAE (V) | RMSE (V) | R2 | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 0.436 | 0.920 | 0.999 | 0.410 |

| S2 | 2.649 | 2.965 | 0.989 | 3.173 |

| S3 | 0.273 | 0.365 | 1.000 | 0.304 |

| Sensor | Measurement | MAE | RMSE | R2 | MAPE (%) | r | nRMSE(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Cost | Current (A) | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.89 | 4.8 | 0.94 | 6.5 |

| Voltage (V) | 3.96 | 5.38 | 0.81 | 5.8 | 0.90 | 7.2 | |

| High precision | Current (A) | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.93 | 7.6 | 0.97 | 4.2 |

| Voltage (V) | 1.12 | 1.42 | 0.996 | 1.3 | 0.998 | 2.0 |

| Aspect | Low-Cost Sensors | High-Precision Sensors |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy and linearity | Moderate accuracy: deviations increase at low voltages and currents due to limited linear response. | High accuracy and linearity maintained across the full measurement range. |

| Response stability | Susceptible to drift caused by temperature variations and aging. | Excellent short- and long-term stability under environmental variations. |

| Signal Conditioning | Requires external amplification, filtering, and frequent recalibration. | Integrated conditioning, factory calibration, and temperature compensation. |

| Sampling and Resolution | Limited ADC resolution (10–12 bits), reducing sensitivity to small variations. | High-resolution ADCs (16–24 bits) enabling fine measurement detail. |

| Noise Immunity | More sensitive to electromagnetic interference and ground loops. | Shielded design and higher common-mode rejection ratio ensure cleaner signals. |

| Cost and Availability | Low cost and easy to implement, ideal for prototypes or educational systems. | Higher cost, intended for professional or industrial-grade monitoring. |

| Integration Complexity | Simple wiring and configuration, but prone to offset and calibration errors. | Requires careful configuration and communication setup (e.g., I2C, SPI, or Modbus) but ensures reliable long-term operation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alcalá, J.; Juárez, J.A.; Cárdenas, V.; Charre-Ibarra, S.; González-Rivera, J.; Gudiño-Lau, J. Balancing Cost and Precision: An Experimental Evaluation of Sensors for Monitoring in Electrical Generation Systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 7052. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227052

Alcalá J, Juárez JA, Cárdenas V, Charre-Ibarra S, González-Rivera J, Gudiño-Lau J. Balancing Cost and Precision: An Experimental Evaluation of Sensors for Monitoring in Electrical Generation Systems. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):7052. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227052

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlcalá, Janeth, J. Antonio Juárez, Víctor Cárdenas, Saida Charre-Ibarra, Juan González-Rivera, and Jorge Gudiño-Lau. 2025. "Balancing Cost and Precision: An Experimental Evaluation of Sensors for Monitoring in Electrical Generation Systems" Sensors 25, no. 22: 7052. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227052

APA StyleAlcalá, J., Juárez, J. A., Cárdenas, V., Charre-Ibarra, S., González-Rivera, J., & Gudiño-Lau, J. (2025). Balancing Cost and Precision: An Experimental Evaluation of Sensors for Monitoring in Electrical Generation Systems. Sensors, 25(22), 7052. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25227052