Abstract

Measurement of real-world physical activity (PA) data using accelerometry in older adults is informative and clinically relevant, but not without challenges. This review appraises the reliability and validity of accelerometry-based PA measures of older adults collected in real-world conditions. Eight electronic databases were systematically searched, with 13 manuscripts included. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for inter-rater reliability were: walking duration (0.94 to 0.95), lying duration (0.98 to 0.99), sitting duration (0.78 to 0.99) and standing duration (0.98 to 0.99). ICCs for relative reliability ranged from 0.24 to 0.82 for step counts and 0.48 to 0.86 for active calories. Absolute reliability ranged from 5864 to 10,832 steps and for active calories from 289 to 597 kcal. ICCs for responsiveness for step count were 0.02 to 0.41, and for active calories 0.07 to 0.93. Criterion validity for step count ranged from 0.83 to 0.98. Percentage of agreement for walking ranged from 63.6% to 94.5%; for lying 35.6% to 100%, sitting 79.2% to 100%, and standing 38.6% to 96.1%. Construct validity between step count and criteria for moderate-to-vigorous PA was rs = 0.68 and 0.72. Inter-rater reliability and criterion validity for walking, lying, sitting and standing duration are established. Criterion validity of step count is also established. Clinicians and researchers may use these measures with a limited degree of confidence. Further work is required to establish these properties and to extend the repertoire of PA measures beyond “volume” counts to include more nuanced outcomes such as intensity of movement and duration of postural transitions.

1. Introduction

Physical activity (PA) has been defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure” [1]. An increase in PA in older adults is associated with improved muscular strength [2], lower risk of disability [3], and may also protect against cognitive decline [4]. The beneficial effects of PA on functional tasks such as walking in older adults have also been reported [5,6], which is important given that loss of functional ability is associated with functional dependence [7,8] and can lead to social isolation [9] and malnutrition among older adults [10].

Measurement of physical activity in older adults is therefore informative and relevant. The use of body-worn sensors (wearables) to objectively quantify PA is a welcome advancement in the field, given the potential for inaccuracy and bias inherent in self-reported data from questionnaires which are most commonly used [11]. Wearables are defined as devices that can be worn on the skin or attached to clothing to continuously and closely monitor an individual’s activities, without interrupting or limiting the user’s motions (adapted from [12]). Wearables typically incorporate accelerometers to enable continuous (usually seven days), unobtrusive monitoring in real-world environments [13]. Real-world environments generally include the home (which could be retirement villages) and other free-living environments such as parks and cafes, etc. This confers an advantage over data collected in controlled or simulated environments which may have observational bias and other influences [13,14] and are not reflective of real-world conditions [15,16]. Data collected and processed in a controlled laboratory environment, which is usually shorter than those collected in real-world settings, is not reflective of the data collected and processed in real-world environments, especially for older adults [17].

Associated with this advance is the development of novel outcomes from accelerometry data. Frequency counts (e.g., number of sit-to-stand transitions in a day), intensity (e.g., stroll versus run), pattern (accumulation of bouts of walking), and within-person variability give more information than simple volume measures (e.g., total amount of walking time) and therefore provide a greater understanding of the composition of physical activity and the association between it and functional tasks [18].

Several challenges to capturing real-world PA data have been identified. Measurement accuracy in older adults is compromised by the use of walking aids, slower gait, lower level of physical activity intensity, reduced cognitive ability and reduced adherence with research instructions, thus posing technical challenges to detection and capture of movement and analysis [13,19]. Moreover, hardware-related costs and technical competency in dealing with interpretation of accelerometry data, could further add to these challenges [20].

Despite these constraints, there has been a marked increase in accelerometry-based PA research including large-scale, population-based studies (e.g., [21,22]) which in turn has led to issues related to the robustness of these metrics—how reliable, valid and responsive are they? Few studies have examined these questions in-depth (e.g., [23,24]). A recent review update reported that consumer-grade activity trackers tend to overestimate step count (167.6 to 2690.3 steps per day), with slower and impaired gait reducing the level of agreement (<10% at gait speeds of 0.4–0.9 m/s for ankle placement) with reference methods (e.g., ActiGraph) [25]. However, that review included both laboratory and real-world environments, which limits generalizability. Wearables need to be validated under conditions representative of their intended use, that is, in real-world environments [15,16].

In view of the questions that arise from this rapidly expanding field, a synthesis of current research concerning accelerometry-based PA measurement using wearables is required. We posit three key questions: (a) Which PA movements (e.g., sitting, standing, walking) are reliably and validly measured using accelerometers in community-dwelling older adults in real-world conditions? (b) Is the measurement of these PA movements able to show change? (c) How were these PA movements quantified in terms of the type, number, and location of the accelerometers, and duration (time spent) of monitoring? We also report on adherence, usability, and acceptability for wearables where reported.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [26] and was registered with the National Health Service PROSPERO database under the registration number: CRD42021228010.

2.1. Search Strategy

Systematic searches were conducted across the following eight databases: AMED, CINAHL, Embase, IEEE, Medline, PsycINFO, Web of Science and Scopus. In addition to the above databases, reference lists of review articles and included studies were hand searched to identify additional relevant studies. The search criteria were limited to studies conducted in the English language. An initial search included articles published between 1 January 2010 and 18 January 2021. A follow-up search was conducted on 25 November 2022. A lower limit of 2010 was chosen given the rapid technological advancement in the design and development of accelerometers which are not comparable to those currently used.

The search terms were grouped into four categories and searched in the following sequence: (a) accelerometry/wearable devices (MESH term used—“Fitness Trackers”, “Accelerometry or Actigraphy”, “Wearable Electronic Devices”) (b) physical activity (MESH term used—“exercise”, “running”, “swimming”, “walking”, “motor activity”, “freezing reaction”, “cataleptic”) (c) older adults (MESH term used—“aged”, “aged, 65 and over”) (d) clinimetric properties (MESH term used—“reproducibility of results”, “sensitivity and specificity”). Further details of the search strategy are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Table 1 shows the eligibility criteria that were employed in this review.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for article selection in this review.

2.3. Data Extraction and Abstraction

All searches were imported and screened for duplicates in EndNote X9 (Version 3.3). The titles were initially screened by KAJ in EndNote X9, then the selected titles and their respective abstracts were exported as a CSV file and imported into a web-based systematic review software—Rayyan [27]. Thereafter, the remaining abstracts were screened by two reviewers (RMA & KAJ) in a blinded process. Disagreements over inclusion were adjudicated and resolved by a third reviewer (SL). Reasons for exclusion were recorded for abstracts based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Following the abstract screening, the remaining full texts were independently reviewed by two reviewers (RMA & KAJ).

A data extraction form was used to standardize the information extracted from each article. KAJ extracted the data which were verified by RMA.

2.4. Clinimetric Properties

Inter-rater reliability was established as the degree of agreement between two independent observers of duration of activities from videos and reported as intra-class correlation (ICC, 95% CI). Relative reliability was established as the degree of agreement in terms of ranks or position of individuals within a group and reported as intra-class correlation (ICC, 95% CI). Absolute reliability was established as the degree of agreement in terms of precision of the individual measurements and reported as minimal detectable changes (that was calculated using standard error of measurement). Responsiveness was established as the ratio between minimally clinically important change on the measure and mean squared error of the response obtained from an analysis of variance model and reported as Guyatt’s responsiveness (GR) coefficient [28].

Criterion validity was established either as agreement between a gold standard reference and accelerometry or as percentage of agreement between video observation and accelerometry and was reported as ICC or as F-Score (for comparison between different algorithms) or as sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, precision, or positive predictive values.

Bland–Altman plots [28,29,30,31] or modified Bland–Altman plots [32,33] described limits of agreement and systemic errors. Construct validity was tested between step counts and moderate-to-vigorous PA and was reported as correlation, rs (Spearman’s Rho).

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) checklist was used to evaluate the risk of bias for all studies included in this review [34]. Two reviewers (RMA and KAJ) independently assessed the quality of the studies, with a third reviewer (SL) settling any disagreements.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

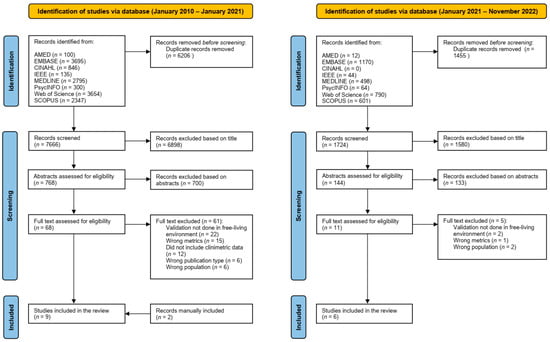

The initial search identified 13,872 records, of which 6206 duplicates were removed. The remaining 7666 titles were screened, resulting in 768 records carried through to abstract review. The updated search conducted on the 25th of November 2022 identified 3179 records, of which 1455 duplicates were removed. The remaining 1724 titles were screened by KAJ resulting in 144 records for the abstract stage (Figure 1). Two reviewers (RMA and KAJ) screened the abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and identified 79 records for full-text review. Thirteen records passed through to the final full-text review stage. Two further publications were retrieved from reference lists, one of which was classified as a Research Letter. Reasons for exclusion included study setting other than “real-world” such as a semi-structured or simulated real-world environment (n = 24); PA metrics relevant to the review were not reported (n = 16); or the study did not report any clinimetric data (n = 12). EndNote was used to index all records.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study design.

3.2. Quality of Studies

Thirteen studies included in this review achieved a minimum score of 70% (i.e., 12 out of a possible 17) based on the AXIS toolkit (Table 2). Thus, two studies were excluded from the review due to methodological weaknesses [35,36].

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment of selected articles based on AXIS checklist [34].

Table 2.

Methodological quality assessment of selected articles based on AXIS checklist [34].

| Ref. | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 1 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 1 | Q14 1 | Q15 | Q16 | Q17 | Q18 | Q19 2 | Q20 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [37] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| [36] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| [38] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| [31] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| [39] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| [32] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| [40] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| [29] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| [41] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| [28] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| [30] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| [42] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| [35] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| [33] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| [43] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

Note: “Q” refers to question. So “Q1” implies “Question 1”. Each 1’s, which are in green fonts, represents an affirmative appraisal score for that question, while each 0’s, which are in red fonts, represents a negative appraisal score for that question. Please see Downes et al. [34] for more details. 1 These questions related to non-responders were not included in the tabulation of the scores. 2 A negative response to this question “Were there any funding sources or conflicts of interest that may affect the authors’ interpretation of the results?” is taken as a score of “1” and vice versa.

3.3. Characteristics of the Studies

All studies bar one recruited a Caucasian population [43]. The mean age of the total sample was 74.9 ± 6.1 years, and 62.4 ± 20.2% were females. Participants over 80 years of age who were included (n = 45), were mainly frail but ambulant [32,33,41,43]. Participants were recruited either through ongoing studies or advertisement (letter, flyer, word-of-mouth, etc.) or through convenience sampling from senior citizen centers. The sample sizes ranged from 5 to 50 participants. All 13 studies used wearable sensors incorporating a tri-axial accelerometer with an average duration of 108.2 ± 128.8 h of data. Four studies investigated duration of physical activities such as sitting, standing, walking and lying [33,37,40,41], three investigated only walking (gait) bouts [32,38,42], and six studies focused mainly on step counts as their key outcome measures [28,29,30,31,39,43]. Two studies used only proprietary accelerometers [32,41], one included both proprietary and commercially available accelerometers [37], and ten studies used commercially available accelerometers. Four studies reported inter-rater reliability (n = 63) [33,37,40,41] and one study reported relative reliability, absolute reliability and responsiveness (n = 50) [28]. Twelve studies reported criterion validity (n = 321) with one study reporting construct validity (n = 30) [39]. All 13 studies (total n = 351) were cross-sectional validation studies and were from Australia (n = 62) [30,39], Israel (n = 12) [38], Japan (n = 44) [43], The Netherlands (n = 25) [40,41], New Zealand (n = 38) [32,33], Norway (n = 16) [37], Slovenia (n = 50) [28], Switzerland (n = 37) [42], UK (n = 25) [29] and USA (n = 35) [31] (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Sample size and basic demographic information of each population from the studies included in the systematic review.

Table 4.

Design, settings and aims of studies included in the systematic review.

3.4. Study Protocol

Study protocols for validity testing varied with respect to the reference standard, the outcome of interest, environment and duration of testing, as well as the location of sensors.

3.5. Reference Standard

Six studies validated consumer-grade wearables with research-grade reference accelerometers [28,29,31,38,39,42]. Five of the studies used the video/visual method as their “gold standard” for their validation reference [32,33,37,40,41]. One study used both video as well as research-grade reference accelerometers [30]. One study used the doubly labelled water (DLW) method as their reference for their validation [43] (Table 5). The DLW method is an established technique for measuring energy expenditure. This method is based on the estimation of the rate of CO2 elimination from the body [46].

Table 5.

Clinimetric properties and methods of studies included in the systematic review.

3.6. Outcomes

Step count was reported as the main outcome in six studies [28,29,30,31,39,43]. Three studies focused on gait bouts [32,38,42], whilst the duration of walking, sitting, standing and lying was reported in the remaining four studies [33,37,40,41] (Table 5).

3.7. Environment

Nine studies collected and validated real-world accelerometry data exclusively within the participants’ home/retirement village environment [29,30,31,32,37,38,41,42,43]. One study investigated criterion validity in a controlled setting within a retirement village as well as in participants’ home environment [33]. Dijkstra and colleagues investigated criterion validity in the laboratory environment with 20 participants and also carried out further validation in a real-world home environment with five participants [40]. Burton and colleagues investigated intra-rater reliability using the two-minute-walk test (2MWT) in a laboratory environment, but construct validity in the home [39]. Kastelic and colleagues conducted a test battery that included common real-life tasks, within the laboratory environment as well as an uncontrolled free-living study [28]. For the purposes of this review, we have included only the home or free-living environment data in our analysis.

3.8. Duration of Wear

Duration of wear was mixed among the studies and ranged from 14 days duration to under 10 min: <10 min (n = 45) [32,33]; 30 min (n = 25) [40,41]; 100 min (n = 16) [37]; 12 h (n = 37) [42]; two days (n = 35) [31]; four days (n = 50) [28]; seven days (n = 57) [29,30]; ten days (n = 12) [31] and 14 days (n = 74) [39,43]. None of the studies exceed the 14-day duration. Duration of wear was influenced by the choice of criterion in the sense that studies relying on research-grade accelerometers [28,29,30,31,39,42] and DLW method [43] as their reference standard captured un-instructed daily activities (excluding water activities) during waking hours and exceeded a 12 h period. By contrast, studies that employed video or direct observation as reference [32,33,37,40,41] limited their duration of real-world observation to a maximum of 100 min, with two studies capturing less than 10 min of activities [32,33] (Supplementary Table S2).

3.9. Sensor Location

The most common location of wear was the wrist (n = 205) [28,29,31,37,39,42] followed by the back (lower back or back of the waist) (n = 104) [32,33,40,43]. One study also extended the validation for the Misfit Shine accelerometer to the waist as an additional location of wear because this device was designed to be worn in both places [29]. One study used the wearable on the right hip (n = 32) [30] and another used the wearable as a necklace (n = 20) [41]. Awais and colleagues investigated data from participants who wore four accelerometers concurrently—on the wrist, chest, lower back and thigh (n = 16) [37] (Supplementary Table S2).

The location of sensors appeared to influence accuracy. Studies that use a single sensor close to the participant’s center of gravity such as the waist [29], hip [30] or lower back [32,33,40] reported higher sensitivities than those placed on the wrist or around the neck, supporting the findings of a recent review [25].

3.10. Reliability

Inter-rater reliability conducted within real-world conditions was reported in four studies (n = 63) [33,37,40,41]. Dijkstra et al. [40] reported inter-rater reliability of activity durations of ten participants by two independent observers (via video analysis)—walking (0.95), sitting (0.78), standing (0.99) and lying (0.98). Taylor et al. [33] also reported excellent inter-rater reliability between two independent observers on ten randomly selected video footage—walking (0.94), sitting (0.99), standing (0.98) and lying (0.99). Geraedts et al. [41] reported ICC for inter-rater agreement of the video observation was 0.91 in the free movement protocol. Awais et al. [37] reported that the overall level of agreement of out-of-lab activities was above 0.90 for one randomly selected video that was chosen to be rated by five independent raters.

Intra-rater reliability conducted within real-world conditions was reported as relative and absolute reliability. Relative reliability of step counts from commercial accelerometers ranged from poor to good for both single-day averages as well as three-day averages. The results were similar for average active calories (which was based on the differences between total calories computed by the accelerometers and estimated basal metabolic rate based on Harris and Benedict [51]). Absolute reliability was generally better (i.e., lower) for averaged measures—step count and active calories—of three days compared to single-day measures [28].

3.11. Validity of Accelerometers

The overall sample size for testing criterion validity was n = 321 including diverse populations and incorporating a range of study protocols. Criterion validity between research-grade wearables and consumer-grade wearables was excellent for step counts measured at the right hip: ICC = 0.94 (95%CI [0.88, 0.97]) (FitBit One/Zip versus ActiGraph GT3X+) [30] and the waist: ICC = 0.96 (95%CI [0.91, 0.99]) (Misfit Shine versus ActiGraph GT3X+) [29] and ICC = 0.91 (95%CI [0.79, 0.97]) (NL2000i) [29], but lower on the wrist: ICC ranged from ICC = 0.83 (95%CI [0.59, 0.93]) (Misfit Shine versus NL2000i) to ICC = 0.86 (95%CI [0.67, 0.94]) (Misfit Shine versus ActiGraph GT3X+) [29]. The average daily step count between consumer-grade wearables and reference devices was overestimated in two studies [28,30]. Results were mixed in another, which employed two different locations of wear (wrist and waist) as well as two different research-grade reference devices (ActiGraph and NL2000i) [29]. Garmin Vivosport and Garmin Vivoactive 4s performed much better than Polar Vantage M for step counts—0.98 versus 0.37 and 0.95 versus 0.37, respectively [28]. Briggs et al. [31] found no significant difference (p = 0.22) between the daily step count from wrist-worn Garmin Vivosmart HR and the reference, hip-worn ActiGraph GTX3X+: ICC = 0.94 (95%CI [0.88, 0.97]). This study also reported that the differences due to step counts derived MVPA were reduced using age-specific cut-offs [31]. Kastelic et al. [28] reported that computed measures such as activity calories, which were derived from accelerometry and heart rate data, did not perform as well as step counts from the accelerometry. The agreement between activity calories for all three devices was lower than the agreement between steps counts: Garmin Vivosport—0.58, Garmin Vivoactive 4s—0.55 and Polar Vantage M—0.15. Two studies validated algorithms developed to detect the duration of gait bouts estimated from a single wrist worn consumer-grade wearable. Brand et al. collected ten days of data from 12 older adults, and reported that the new algorithm had 76.2% accuracy, 29.9% precision, 67.6% sensitivity and 78.1% specificity for detecting gait bouts. Soltani et al. collected 12 h of data from 37 older adults, and reported even better scores—accuracy was 95.2%, precision was 71.8%, sensitivity was 87.1% and specificity was 96.7% for detecting gait bouts. They also compared their method with previously published algorithms. Their algorithm’s F1-score was 74.9%, which was better or close to earlier studies which utilized multiple accelerometers. [42,47].

Studies that used the observer/visual/video method to validate their data with accelerometer-based algorithms mainly reported their results using sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive values. Chigateri et al. [32] reported agreement between uSense algorithm classification compared to video labelling (frame-by-frame analysis) for walking and non-walking during unscripted activities (real-world) as 88.7% (74.9–96.4) and 92.2% (89.5–95.7), respectively; however, the algorithm systematically overestimated walking behaviour. The mean difference between the algorithm and video categorization was 26.5 s. Dijkstra et al. [40] reported sensitivity for walking—93.5%, lying—98.7%, sitting—83.2% and standing—80.1%, between the output of DynaPort MoveMonitor and video analysis values (durations). Similarly, Taylor et al. [33] reported sensitivity of walking (locomotion)—92.2%, lying—100%, sitting—94.5% and standing—38.6% when comparing the output from DynaPort MoveMonitor and the video analysis values (durations). Median absolute percentage error was reported as: walking, 0.2% (inter quartile range (IQR), −4.3% to 14.0%); lying, 0.3% (IQR, −4.2% to 21.4%); sitting, −22.3% (IQR, −62.8% to 10.7%); and standing, 24.7% (IQR, −7.3% to 39.6%). The authors noted that 45.6% of the unscripted standing time was misclassified as sitting and 5.3% of the unscripted sitting time as standing [33]. Geraedts et al. [41], who used the accelerometer as a necklace instead of attaching it to the lower back [32,33,40], reported lower sensitivities: walking—63.6%, lying—35.6%, sitting—79.2% and standing—61.3%. One study compared the classical machine learning-based physical activity classification algorithms and deep-learning based physical activity classification algorithms with previous studies in detecting various activities [37]. The F-Score for: walking—94.5%, lying—98.5%, sitting—99.9% and standing—96.1%. The F-score computed based on various sensor configurations (lower back; wrist; thigh; chest; lower back and thigh; lower back, chest, and thigh; lower back, wrist, chest, and thigh) for sitting [range: 99.7% to 100.0%], lying [84.7% to 98.5%], standing [91.6% to 96.1%] and walking [86.9% to 94.5%] activities. Combining more sensors produced better scores.

Construct validity of step counts and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MPVA) between GENEactiv accelerometer and consumer-grade wearables—Fitbit Flex and Fitbit ChargeHR—was reported as a moderate level of agreement between the devices (ICCFlex: 0.68; ICCChargeHR: 0.72) [39].

In summary, these results suggest that step counts and duration of walking, lying, sitting and standing can be measured robustly to a certain degree using a single accelerometer. However, further work is required to understand better how the location of wear and type of reference standard affect accuracy.

One study [43] investigated the validity of a triaxial accelerometer against the doubly labelled water method (DLW) for total energy expenditure reported that the 24 h average metabolic equivalent (MET) of Actimarker was significantly correlated with the PA level assessed by DLW but significantly underestimated it (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the correlation between daily step counts and PA level of DLW was moderate: R2 = 0.248 (p < 0.001).

3.12. Responsiveness of Accelerometers

Only one study reported on the responsiveness of accelerometry (i.e., the capacity of an accelerometer to identify possible changes in PA outcomes associated with a clinical condition over time) [28]. Single day measure of step counts performed better than average three-day measures for Garmin Vivoactive 4s (GR—0.411 vs. 0.041) and Polar Vantage M (0.126 vs. 0.060), but not for Garmin Vivosport (0.022 vs. 0.288). However, all three devices showed relatively weak to moderate responsiveness for active calories (GR > 0.232) for both single-day as well as averaged-day measurements, except for Garmin Vivosport (Single day GR = 0.073) [28] (Table 5).

3.13. Acceptability and Adherence of Accelerometers

Only one study planned and purposefully measured adherence. Geraedts et al. [41] reported 100% adherence during daytime and 80% during sleep from a necklace sensor worn for seven days. The authors also collected information on the level of comfort, weight, size and usability of the sensor when worn during the daytime using a user-evaluation questionnaire on a scale of 1 to 5. They reported a high mean score of 4.4 ± 0.6 and concluded that user acceptance was high. Three studies reported adherence based on missing data [28,29,39]. Farina et al. [29] required participants to wear five devices (two on the wrist and three on the waist) over seven consecutive days and reported excluding three participants (12%) from their analysis due to receiving less than four days of data from the reference device, which indicated that adherence was low for longer durations of data capture. Burton et al. [39] reported that close to 50% of participants had some missing data from their wrist-based wearables over 14 days, also suggesting declining levels in adherence with increasing duration of data capture. Kastelic and colleagues reported the adherence of wearing three different accelerometers on the non-dominant wrist (together with a reference accelerometer on the waist) over 12 days, each device for four days, based on wear time. The wear time compliance with the Polar Vantage M, Garmin Vivoactive 4s and Garmin Vivosport was as high as 24.0 ± 0.1 h/day, 23.9 ± 0.5 h/day and 23.9 ± 0.5 h/day, respectively. None of the four studies reported age- or gender-related differences (Supplementary Table S2).

3.14. Summary of Results

Table 6. summarizes the clinimetric properties of accelerometry-based PA measures of older adults collected in real-world conditions.

Table 6.

Summary of clinimetric properties of PA measures in real-world conditions.

4. Discussion

This review is the first to our knowledge to examine the reliability and validity of accelerometry-based PA measures of older adults collected in real-world conditions. Moderate to strong ICCs for inter-rater reliability and criterion validity tentatively establish step count, duration of walking, sitting, standing and lying as robust outcomes. Variations in the methods such as location of sensors and duration of wear highlight differences in the strength of the validity and reliability of the outcome measures. This also points to a need for standardization of protocols of wearing accelerometers in future studies. However, this review identified limitations in the current literature, specifically that most of the outcomes are limited to volume metrics.

4.1. Reliability of PA Measures

Good to excellent inter-rater reliability was observed for the durations of sitting, standing, walking and lying activities. Inter-rater reliability of step counts in real-world environment was not reported. Intra-rater reliability differed by the brand and the type of measures. The Garmin Vivosport and Garmin Vivoactive 4s had better relative and absolute reliability than the Polar Vantage M for both step counts as well as active calories. Derived metrics from step counts, such as activity intensities (e.g., MVPA), were not as reliable as steps counts. None of the studies investigating duration of PA activities reported intra-rater reliability. The reasons for omitting reliability testing were not discussed by the authors. This omission limits our understanding as to whether accelerometry-based PA measures such the durations of sitting, standing, walking and lying activities are affected by the individual observers, when captured in real-world conditions.

4.2. Validity of PA Measures

The most common “gold-standard” reference for criterion validity was using research-grade accelerometers, followed by the use of video or direct observation. In all but one reported study, a single tri-axial accelerometer was sufficient to distinguish PA validly. However, there was a lack of homogeneity for real-world assessments with respect to sensor location and duration, the brand of accelerometer employed, and the instructions given to participants when carrying out uninstructed daily activities.

As noted above, the duration of wear varied amongst studies which is partially attributable to the level of intrusiveness of the reference devices used. There seems to be no consensus on the minimum length of duration for accelerometry-related validation studies, but a minimum of 30 min of semi-structured activities has been previously recommended for real-world settings [52]. Capturing, processing and annotating videos that are several days in length might be challenging, and the alternative seems to be to aim to capture as many commonly performed activities within a shorter timeframe [52]. Additionally, merging and synchronizing of data is challenging, although the use of platforms seems to offer some promise [53]. Intrinsic factors (motivation, personal preferences) and extrinsic factors (weather, environment) may affect habitual physical activity performance [15,54]. Although this seems to be a reasonable compromise between duration and practicality, it is questionable as to whether the variations in intrinsic and extrinsic factors within daily PA could be captured within such a timeframe.

Chigateri et al. [32] and Dijkstra et al. [40] provided limited instructions for unstructured real-world activities, e.g., “what they normally do during the day”, whereas others were more explicit. Taylor et al. [33] informed their participants to include common activities such as walking, lying, sitting, and standing, while Geraedts et al. [41] included common household chores such as vacuuming and clearing dishes. It is noteworthy that among these commonly reported four PA—walking, lying, sitting and, standing—the sensitivity for sitting and standing were relatively lower than the former two. The use of a single sensor on the lower back was not able to sufficiently distinguish sitting from standing, which could have misclassified these two activities in two studies [33,40]. However, Chigateri et al. [32] reported that walking duration was overestimated with the uSense wearable device and postulated that there was a higher likelihood for algorithms to overestimate walking duration since inactive durations such as ‘pauses during walking’ between walks could have been misclassified as walking time [32]. Awais et al. [37] dataset consisted of 15 common free-livings activities (see [44,45]) that were performed in an order that suited the participants’ preferences, but with no other instructions. This study compared the use of machine learning and deep-learning techniques to classify data from four accelerometers, concurrently worn on four different locations on the body, as walking, lying, sitting, and standing activities. Although the use of additional accelerometers to classify activities produced much better results than studies that used a single sensor, it was not conclusive as to which technique—machine learning versus deep-learning technique—was superior, since the results of both methods plateaued [37].

Steps counts were generally overestimated by commercial-grade wearables, but the evidence was not conclusive since different brands of accelerometers elicited different results [28]. Although step count derived metrics generally did not perform as well as direct step counts, and the choice of age-specific cut-offs could improve the accuracy [31].

4.3. Study Protocol

Validity and accuracy of the metrics varied with the duration of data collection. Soltani et al. [42] achieved very high accuracy in identifying gait bouts from 12 h of data. Brand et al. [38], who also used the wrist but collected data up to ten days, reported worse results. However, both studies used different accelerometers, and the choice and location of wear of their references was also different—one used the Axivity AX3 on the lower back, while the other used the ActiGraph GT9X Link on the shank. Furthermore, the algorithms implemented by these two studies were also different [31,42].

These discrepancies highlight the need for standardization of the methodology used in validation studies to allow comparison between their results and findings. Future validation studies should aim to adopt recommended methods and protocols relevant for community-dwelling older adults [45,52].

Interestingly, only one study investigated whether wearables could detect change over time, but the findings were mixed, inconclusive and device-specific [28]. The responsiveness of single-day measures of step counts was generally better than the three-day average, but this needs to be cautiously interpreted. The lack of evidence on responsiveness from more studies may reflect the recruitment of generally healthier older adults. There is greater impetus to establish responsiveness for people with neuro-musculoskeletal conditions, for example those with age-related degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis [55].

4.4. Adherence to Study Protocol

The duration and location of wear of the sensor affected the level of adherence. Wrist-worn sensors yielded a high level of adherence, but increasing the duration of data capture could reduce the level of adherence and compliance [28,29,39]. Although wearing sensors on the wrist may be more natural than other locations such as the lower back and the ankle, there was a possibility that older adults might forget to put them back on after they had removed them, perhaps during sleep. There was a high level of adherence in wearing the sensors as a necklace, but at the expense of sensitivity, perhaps because there was no need to remove them during sleep and studies constituted a high proportion of females who may already be in the habit of wearing necklaces. Only one study investigated the level of acceptance of the wearables they tested, possibly because the investigators were developing a new wearable prototype [41].

Real-world validation studies of older adults for different intensities of PA, such as different speed or intensity of walking, are missing in the literature. We know that the accuracy of step counts was lower in participants who walked with a slower gait speed [25] or walked with lower intensity [56]. Also lacking are validation studies that test more nuanced metrics such as the duration of postural transition, including sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit, which are important indicators of functional mobility and lower limb strength. Real-world postural transitions, similar to other PA, are ecologically more valid when performed at home as they are executed in a familiar environment [52].

Despite this, there is a growing body of inference-based evidence from studies that use accelerometry to investigate associations between mortality, health and functioning in large populations. These studies indirectly examine aspects of validation such as construct validity [57] and predictive validity [58], thereby providing some assurances.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

This systematic review used a comprehensive search strategy of eight databases, included clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, utilized the AXIS checklist to access risk of bias, and followed the PRISMA guidelines. It also adopted the blinded adjudication process for the abstract and full-text review. The process followed in the review was designed to minimize bias and increase the transparency of the reporting.

Limitations included a focus on studies in the English language and exclusion of grey literature. Secondly, the sample size for most of the studies was small and predominantly female. Finally, not all the studies reported on the reliability of the wearables, and of those that did, all failed to report test–retest reliability. Both these latter limitations could have weakened the overall strength of the studies reported. In addition, larger-scale and longer-duration studies could better inform us on the level of adherence in wearing the accelerometers among older adults.

5. Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

Step counts, duration of walking, sitting, standing and lying are reliably and validly measured using accelerometers in community-dwelling older adults in real-world conditions. However, only step counts have been reported to show change over time.

Robust outcomes from accelerometry monitoring of PA are limited to ‘volume’ counts such as number of steps and duration of sitting, standing, walking and lying, which points to the need for further research on nuanced PA outcomes to provide more in-depth understanding on how PA affects functional tasks. Wrist-worn and neck-worn accelerometers are not as metrically robust as those worn at the waist, hip and lower back. Adherence and usability are negatively associated with duration of wear.

To extend the field of research, more real-world studies are needed, in particular, more studies that focus on generally healthy older adults, investigating more nuanced aspects of PA such as intensity of movement (e.g., slow walk versus running) and duration of postural transitions. Data from non-Caucasian populations are also needed. More longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the responsiveness of the metrics, for example, whether step counts are sensitive to detect fall risk in healthy community-dwelling older adults. Finally, future studies should also investigate wearability and acceptance of their wearables in larger sample cohorts. This will inform researchers on whether such wearables could be used in longer-term data collection processes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/s23177615/s1, Table S1: Search strategy, Table S2: Acceptability and adherence of tools/instruments of studies included in the systematic review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.J., R.M.A., S.L., N.K., S.D.D. and R.T.; methodology, K.A.J., R.M.A., S.L., N.K., S.D.D. and R.T.; data analysis, K.A.J. and R.M.A.; investigation, K.A.J. and R.M.A.; resources, N.K. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.J., R.M.A., S.L., N.K., S.D.D. and R.T.; writing—review and editing, K.A.J., R.M.A., S.L., N.K., S.D.D. and R.T.; supervision, N.K., S.D.D., S.L. and R.T.; project administration, N.K., S.D.D., S.L. and R.T.; funding acquisition, N.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ageing Well National Science Challenge, New Zealand. N.K. was supported as the Joyce Cook Chair in Ageing Well funded by the Joyce Cook Family Foundation. K.A.J. was financially supported by HOPE Foundation for Research on Ageing Scholarship. S.D.D. was supported by the Mobilise-D project that has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under grant agreement No. 820820. This JU receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). S.D.D. was also supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (IMI2 JU) project IDEA-FAST–Grant Agreement 853981. S.D.D. was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) based at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and Newcastle University, and by the NIHR/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility (CRF) infrastructure based at Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle University and the Cumbria, Northumberland and Tyne and Wear (CNTW) NHS Foundation Trust. All opinions are those of the authors and not the funders.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Derryl Hayman in her assistance with the search strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

S.D.D. reports consultancy activity with Hoffman La Roche Ltd. outside of this study.

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, K.A.; Rojer, A.G.M.; D’Andrea, L.; Otten, R.H.J.; Heymans, M.W.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Verlaan, S.; Whittaker, A.C.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Maier, A.B. The association of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior with skeletal muscle strength and muscle power in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.; O’Sullivan, P.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engeroff, T.; Ingmann, T.; Banzer, W. Physical Activity Throughout the Adult Life Span and Domain-Specific Cognitive Function in Old Age: A Systematic Review of Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1405–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, F.; Onder, G.; Carpenter, I.; Cesari, M.; Soldato, M.; Bernabei, R. Physical activity prevented functional decline among frail community-living elderly subjects in an international observational study. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2007, 60, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, D.H.; Warburton, D.E. Physical activity and functional limitations in older adults: A systematic review related to Canada’s Physical Activity Guidelines. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, A.; Wohland, P.; Wittenberg, R.; Robinson, L.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Jagger, C.; Green, E.; Gao, L.; Barnes, R.; et al. Is late-life dependency increasing or not? A comparison of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS). Lancet 2017, 390, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, P.G.; Kingston, A.; Johnson, G.R.; Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Jagger, C. New horizons in the compression of functional decline. Age Ageing 2018, 47, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaltenstein, J.; Bula, C.; Santos-Eggimann, B.; Krief, H.; Seematter-Bagnoud, L. Factors associated with going outdoors frequently: A cross-sectional study among Swiss community-dwelling older adults. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ortuno, R.; Casey, A.-M.; Cunningham, C.U.; Squires, S.; Prendergast, D.; Kenny, R.A.; Lawlor, B.A. Psychosocial and functional correlates of nutrition among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2011, 15, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, K.P.; Szeklicki, R.; Minetto, M.A.; Murphy, M.H.; Polito, A.; Ghigo, E.; van der Ploeg, H.; Ekelund, U.; Maciaszek, J.; Stemplewski, R.; et al. A systematic literature review of reviews on techniques for physical activity measurement in adults: A DEDIPAC study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Emaminejad, S.; Nyein, H.Y.Y.; Challa, S.; Chen, K.; Peck, A.; Fahad, H.M.; Ota, H.; Shiraki, H.; Kiriya, D.; et al. Fully integrated wearable sensor arrays for multiplexed in situ perspiration analysis. Nature 2016, 529, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Michaud, M.; Oudre, L.; Dorveaux, E.; Gorintin, L.; Vayatis, N.; Ricard, D. The Use of Inertial Measurement Units for the Study of Free Living Environment Activity Assessment: A Literature Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCambridge, J.; Witton, J.; Elbourne, D.R. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S.; Wickström, N. Evaluation of the performance of accelerometer-based gait event detection algorithms in different real-world scenarios using the MAREA gait database. Gait Posture 2017, 51, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, M.A.; Coppens, M.J.; Lord, S.R.; Lovell, N.H.; Gschwind, Y.J.; Redmond, S.J.; Del Rosario, M.B.; Wang, K.; Sturnieks, D.L.; Persiani, M. Wearable pendant device monitoring using new wavelet-based methods shows daily life and laboratory gaits are different. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016, 54, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renggli, D.; Graf, C.; Tachatos, N.; Singh, N.; Meboldt, M.; Taylor, W.R.; Stieglitz, L.; Schmid Daners, M. Wearable inertial measurement units for assessing gait in real-world environments. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, T.F.; Liao, Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Huang, W.C.; Hsueh, M.C.; Chan, D.C. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity duration is more important than timing for physical function in older adults. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Lauderdale, D.S. Cognitive Function, Consent for Participation, and Compliance with Wearable Device Protocols in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Mciver, K.L.; Pate, R.R. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, S531–S543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.; Jackson, D.; Hammerla, N.; Plötz, T.; Olivier, P.; Granat, M.H.; White, T.; Van Hees, V.T.; Trenell, M.I.; Owen, C.G. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: The UK Biobank Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagelv, E.H.; Ekelund, U.; Pedersen, S.; Brage, S.; Hansen, B.H.; Johansson, J.; Grimsgaard, S.; Nordström, A.; Horsch, A.; Hopstock, L.A. Physical activity levels in adults and elderly from triaxial and uniaxial accelerometry. The Tromsø Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, F.; Lepetit, K.; Fradet, L.; Hansen, C.; Mansour, K.B. Using accelerations of single inertial measurement units to determine the intensity level of light-moderate-vigorous physical activities: Technical and mathematical considerations. J. Biomech. 2020, 107, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, D.S.; McLellan, G. Comparing physical activity estimates in children from hip-worn Actigraph GT3X+ accelerometers using raw and counts based processing methods. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straiton, N.; Alharbi, M.; Bauman, A.; Neubeck, L.; Gullick, J.; Bhindi, R.; Gallagher, R. The validity and reliability of consumer-grade activity trackers in older, community-dwelling adults: A systematic review. Maturitas 2018, 112, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastelic, K.; Dobnik, M.; Löfler, S.; Hofer, C.; Šarabon, N. Validity, reliability and sensitivity to change of three consumer-grade activity trackers in controlled and free-living conditions among older adults. Sensors 2021, 21, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, N.; Lowry, R.G. The Validity of Consumer-Level Activity Monitors in Healthy Older Adults in Free-Living Conditions. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2018, 26, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.S.; Tiedemann, A.; Hassett, L.M.; Ramsay, E.; Kirkham, C.; Chagpar, S.; Sherrington, C. Validity of the Fitbit activity tracker for measuring steps in community-dwelling older adults. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2015, 1, e000013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, B.C.; Hall, K.S.; Jain, C.; Macrea, M.; Morey, M.C.; Oursler, K.K. Assessing Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity in Older Adults: Validity of a Commercial Activity Tracker. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 3, 766317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chigateri, N.G.; Kerse, N.; Wheeler, L.; MacDonald, B.; Klenk, J. Validation of an accelerometer for measurement of activity in frail older people. Gait Posture 2018, 66, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.M.; Klenk, J.; Maney, A.J.; Kerse, N.; MacDonald, B.M.; Maddison, R. Validation of a body-worn accelerometer to measure activity patterns in octogenarians. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 930–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stack, E.; Agarwal, V.; King, R.; Burnett, M.; Tahavori, F.; Janko, B.; Harwin, W.; Ashburn, A.; Kunkel, D. Identifying balance impairments in people with Parkinson’s disease using video and wearable sensors. Gait Posture 2018, 62, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.; Petersen, C.L.; Kotz, D.; Fortuna, K.L.; Masutani, R.; Batsis, J.A. A Smartwatch Step-Counting App for Older Adults: Development and Evaluation Study. JMIR Aging 2022, 5, e33845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Chiari, L.; Ihlen, E.A.; Helbostad, J.L.; Palmerini, L. Classical machine learning versus deep learning for the older adults free-living activity classification. Sensors 2021, 21, 4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, Y.E.; Schwartz, D.; Gazit, E.; Buchman, A.S.; Gilad-Bachrach, R.; Hausdorff, J.M. Gait Detection from a Wrist-Worn Sensor Using Machine Learning Methods: A Daily Living Study in Older Adults and People with Parkinson’s Disease. Sensors 2022, 22, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Hill, K.D.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Thogersen-Ntoumani, C.; Lewin, G.; Boyle, E.; Howie, E. Reliability and validity of two fitness tracker devices in the laboratory and home environment for older community-dwelling people. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, B.; Kamsma, Y.; Zijlstra, W. Detection of gait and postures using a miniaturised triaxial accelerometer-based system: Accuracy in community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraedts, H.A.; Zijlstra, W.; Van Keeken, H.G.; Zhang, W.; Stevens, M. Validation and User Evaluation of a Sensor-Based Method for Detecting Mobility-Related Activities in Older Adults. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, A.; Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Dejnabadi, H.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Aminian, K. Real-world gait bout detection using a wrist sensor: An unsupervised real-life validation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 102883–102896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Hashii-Arishima, Y.; Yokoyama, K.; Itoi, A.; Adachi, T.; Kimura, M. Validity of a triaxial accelerometer and simplified physical activity record in older adults aged 64–96 years: A doubly labeled water study. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourke, A.K.; Ihlen, E.A.F.; Bergquist, R.; Wik, P.B.; Vereijken, B.; Helbostad, J.L. A physical activity reference data-set recorded from older adults using body-worn inertial sensors and video technology—The ADAPT study data-set. Sensors 2017, 17, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, A.K.; Ihlen, E.A.F.; Helbostad, J.L. Development of a gold-standard method for the identification of sedentary, light and moderate physical activities in older adults: Definitions for video annotation. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerterp, K.R. Doubly labelled water assessment of energy expenditure: Principle, practice, and promise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 117, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, M.; Chiari, L.; Ihlen, E.A.F.; Helbostad, J.L.; Palmerini, L. Physical activity classification for elderly people in free-living conditions. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2018, 23, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedson, P.S.; Melanson, E.; Sirard, J. Calibration of the computer science and applications, inc. accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1998, 30, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, B.; Aminian, K.; Loew, F.; Blanc, Y.; Robert, P.A. Measurement of stand-sit and sit-stand transitions using a miniature gyroscope and its application in fall risk evaluation in the elderly. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2002, 49, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency, I.A.E. IAEA Human Health Series No. 3. Int. At. Energy Agency 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.A.; Benedict, F.G. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1918, 4, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, U.; Zijlstra, W.; Aminian, K.; Chastin, S.F.; De Bruin, E.D.; Helbostad, J.L.; Bussmann, J.B. Recommendations for standardizing validation procedures assessing physical activity of older persons by monitoring body postures and movements. Sensors 2014, 14, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coviello, G.; Florio, A.; Avitabile, G.; Talarico, C.; Wang-Roveda, J.M. Distributed full synchronized system for global health monitoring based on flsa. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux-Fitzgerald, A.; Powell, R.; Dewhurst, A.; French, D.P. The acceptability of physical activity interventions to older adults: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 158, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.E.; Yang, H.Y.; Trentadue, T.P.; Gong, Y.; Losina, E. Validation of the Fitbit Charge 2 compared to the ActiGraph GT3X+ in older adults with knee osteoarthritis in free-living conditions. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Ishikawa-Takata, K.; Tanaka, S.; Bessyo, K.; Tanaka, S.; Kimura, T. Accuracy of estimating step counts and intensity using accelerometers in older people with or without assistive devices. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2017, 25, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Honda, T.; Chen, S.; Narazaki, K.; Kumagai, S. Dose–Response Association between Accelerometer-Assessed Physical Activity and Incidence of Functional Disability in Older Japanese Adults: A 6-Year Prospective Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 75, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroux, A.; Xu, S.; Kundu, P.; Muschelli, J.; Smirnova, E.; Chatterjee, N.; Crainiceanu, C. Quantifying the predictive performance of objectively measured physical activity on mortality in the UK Biobank. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2021, 76, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).