Abstract

The use of inertial measurement unit (IMU) has become popular in sports assessment. In the case of velocity-based training (VBT), there is a need to measure barbell velocity in each repetition. The use of IMUs may make the monitoring process easier; however, its validity and reliability should be established. Thus, this systematic review aimed to (1) identify and summarize studies that have examined the validity of wearable wireless IMUs for measuring barbell velocity and (2) identify and summarize studies that have examined the reliability of IMUs for measuring barbell velocity. A systematic review of Cochrane Library, EBSCO, PubMed, Scielo, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, and Web of Science databases was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. From the 161 studies initially identified, 22 were fully reviewed, and their outcome measures were extracted and analyzed. Among the eight different IMU models, seven can be considered valid and reliable for measuring barbell velocity. The great majority of IMUs used for measuring barbell velocity in linear trajectories are valid and reliable, and thus can be used by coaches for external load monitoring.

1. Introduction

Velocity-based training (VBT) is a resistance training method consisting of monitoring the velocity of movement displacement to support the regulation of load imposed on athletes [1,2,3,4,5]. Therefore, a proper measurement of bar displacement velocity is critical to implement an auto-regulation process of sports training [6,7,8,9,10]. Three reasons can be cited for using velocity as the main outcome [11,12,13]. First, there is a relationship between velocity and the amount of external mass lifted, by which a reduction in lifting velocity occurs as load increases until a terminal velocity is achieved at the maximal load [14]. Second, a nearly perfect linear relationship between velocity and intensity can be observed in many exercises and movements performed at different loads [15,16,17]. Third, reductions in voluntary exercise velocity are strictly related to neuromuscular fatigue induced by the exercise [18,19,20].

If an athlete is to benefit from VBT, certain instruments should be used to ensure that the velocity of movements is accurately and precisely measured [21,22]. For this purpose, different commercial devices can be used to quantify velocity [23]. Among the available options, solutions can be grouped as follows [24]: (i) isoinertial dynamometers consisting of a cable-extension linear velocity transducer attached to the barbell [25,26,27], (ii) optical motion sensing systems or optoelectronic systems [28,29,30,31], (iii) smartphone applications involving frame-by-frame manual inspections [29,32,33], and (iv) inertial measurement units (IMUs) [34]. Since these different technologies offer different possibilities, it can be considered that IMUs represent the most easy-to-use solution because no cable-extension is needed—the sensor simply needs to be attached to the barbell. Compared with video-based solutions, IMUs are also easier and quicker since no operations need to be made [35,36].

IMU solutions use fusion sensing to estimate velocity [37]. Thus, despite their practical benefits, some issues related to accuracy and precision should be considered. IMUs combine accelerometers (usually triaxial), a gyroscope (usually triaxial), and magnetic sensors to provide information about velocity, orientation, and gravitational force [35,38]. Despite the combination of sensors, there is always a margin of error related to the accuracy and precision of the estimations [39]. This margin of error should be understood so that better inferences can be made about human performance variability [40]. In fact, if validity or reliability is neglected, the results can be misunderstood, possibly affecting the judgments of coaches about their athletes [41,42,43,44,45].

On the basis of the importance of confirming the validity and reliability of IMU devices, different original studies have reported the results for different models in the sports sciences community [46,47,48,49]. Naturally, different experimental protocols have led to different results, and not all of the models are covered in the same conditions. Therefore, there is a need for a systematic review summarizing the validity and reliability levels of different IMU models during barbell movements. This will help us to understand whether coaches and athletes can use this technology to monitor resistance training that considers variations in human performance as opposed to in the devices [50].

While several systematic reviews have been published about the use of IMUs [50,51,52,53], no systematic review has summarized the validity and reliability levels of different IMU models for measuring barbell velocity. Considering the importance of the accuracy and precision level of determining barbell velocity in providing adequate prescriptions of resistance training, the aim of the present systematic review was twofold: (1) to identify and summarize studies that have examined the validity of wearable wireless IMU for measuring barbell velocity, and (2) to identify and summarize studies that have examined the reliability of IMUs for measuring barbell velocity.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review strategy was conducted according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [54]. The protocol was registered with the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols with the number 2020120135 and the DOI number 10.37766/inplasy2020.12.0135.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria.

The screening of the title, abstract, and reference list of each study to locate potentially relevant studies was independently performed by 2 of the authors (F.M.C. and M.R.G.). Additionally, they reviewed the full version of the included papers in detail to identify articles that met the selection criteria. An additional search within the reference lists of the included records was conducted to retrieve additional relevant studies. A discussion was made in the cases of discrepancies regarding the selection process with a third author (Z.A.). Possible errata for the included articles were considered.

2.2. Information Sources and Search

Electronic databases (Cochrane Library, EBSCO, PubMed, SPORTDiscus, and Web of Science) were searched for relevant publications prior to 1 January 2021. Keywords and synonyms were entered in various combinations in the title, abstract, or keywords: (sport* OR exercise* OR “physical activit*” OR movement*) AND (“inertial measurement unit” OR IMU OR acceleromet* OR “inertial sensor” OR wearable OR MEMS OR magnetometer) AND (Validity OR Accuracy OR Reliability OR Precision OR Varia* OR Repeatability OR Reproducibility OR Consistency OR noise) AND (barbell OR bar). Additionally, the reference lists of the studies retrieved were manually searched to identify potentially eligible studies not captured by the electronic searches. Finally, an external expert was contacted in order to verify the final list of references included in this scoping review in order to understand if there was any study that was not detected through our research. Possible errata were searched for each included study.

2.3. Data Extraction

A specific Excel spreadsheet was prepared for data extraction (Microsoft Corporation, Readmon, WA, USA) following the guidelines of Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Groups [55]. The spreadsheet was used to identify the accomplishment of inclusion or exclusion criteria and to support the selection of the articles. The process was made by 2 of the authors (F.M.C. and M.R.G.) in an independent way. After that, they compared the results, and any disagreement regarding the eligibility was discussed until a decision was made in agreement.

2.4. Data Items

The following information was extracted from the included original articles: (i) validity measure (e.g., typical error, absolute mean error) and (ii) reliability measure (e.g., intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and/or typical error of measurement (TEM) (%) and/or coefficient of variation (CV) (%) and/or standard error of measurement (SEM)). Additionally, the following data items were extracted: (i) type of study design, number of participants (n), age-group (youth, adults, or both), sex (men, women, or both), training level (untrained, trained); (ii) characteristics of the wearable wireless IMU and comparator (isoinertial dynamometer consisting in cable-extension linear position transducer or optoelectronic system); (iii) characteristics of the experimental approach to the problem, procedures, and settings of each study.

2.5. Methodological Assessment

The STROBE assessment was applied by 2 of the authors (J.P.O. and M.R.G.) to assess the methodological bias of eligible articles following the adaptation of O’Reilly et al. [51]. Each of the included articles was scored for 10 items [51]. In cases of disagreement, it was discussed and solved by consensus decision. The assessment process was made in an independent way. After that, both authors compared the results, and any disagreement regarding the scores were discussed and made a decision in agreement. The study rating was qualitatively interpreted following O’Reilly et al. [51]—from 0 to 7 scores, the study was considered as risk of bias (low quality), whereas, if the study was rated from 7 to 10 points, it was considered as a low risk of bias (high quality).

3. Results

3.1. Study Identification and Selection

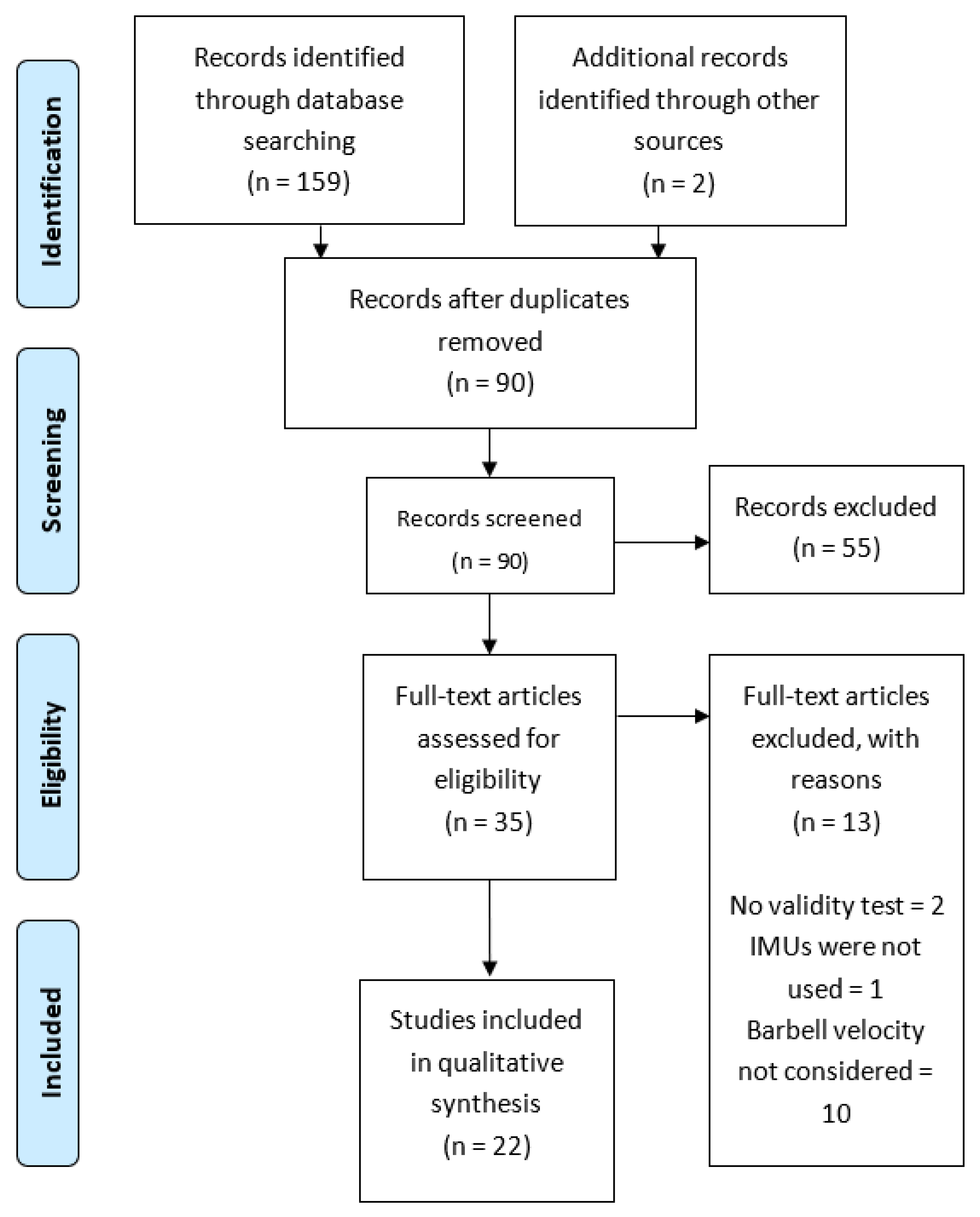

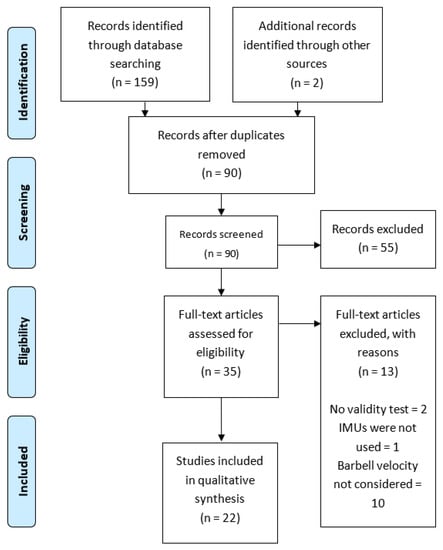

The searching of databases identified a total of 159 titles (Cochrane Library = 11; EBSCO = 59; PubMed = 31; SPORTDiscus = 31; Web of Science = 27). These studies, together with another two included from external sources, were then exported to reference manager software (EndNote X9, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Duplicates (71 references) were subsequently removed either automatically or manually. The remaining 90 articles were screened for their relevance on the basis of titles and abstracts, resulting in the removal of a further 55 studies. Following the screening procedure, 35 articles were selected for in-depth reading and analysis. After reading full texts, a further 13 studies were excluded due to not meeting the eligibility criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

3.2. Methodological Quality

The overall methodological quality of the cross-sectional studies can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methodological assessment of the included studies.

3.3. Characteristics of Individual Studies

Characteristics of the included studies can be found in Table 3. Twenty-one of the included articles tested validity of the IMU [23,24,27,34,46,48,49,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. Nineteen of the included articles tested the reliability of the IMU [23,24,27,34,46,48,49,56,57,58,60,61,62,64,65,66,67,68,69]. Six of the included articles compared the IMU with linear transducers [23,27,32,48,62,68]. Five of the articles compared the IMU with contact platform [56,58,59,60,67], while one of the articles [69] compared the IMU with field computation method. Finally, six of the articles compared the IMU with motion capture system [24,61,64,65,66,70].

Table 3.

Study characteristics.

Among the included studies, 10 tested the back squat [23,34,46,56,57,58,62,63,65,68]; 9 the bench press [1,23,24,34,49,58,64,66,69], 1 the hip thrust [34]; 1 the bench throw [58], 1 the prone bench pull [23]; 2 the counter movement jump [60,67]; 1 the power snatch, clean, jerk [61]; and 1 the hexagonal barbell deadlift [48].

Overall, eight different IMU models were tested, in which two studies were conducted using the Sensei Bar [27,46], one using the Gyko [49], six using the Myotest [56,58,59,65,67,69], six using the Push Band [23,24,48,54,64,66], four using the Wimu Real Track [6,60,62,68], two using the Pasco [61,70], and one using the Rehagait [63].

3.4. Results of Individual Studies: Validity of IMU for Estimation of Barbell Velocity

Information of the validity levels obtained in the included studies can be found in Table 4. Some of the studies listed in Table 4 were reported to be not valid (n = 4). Other studies were reported to be valid (n = 18). For the Barsensei model, the SEE values of validity were between 0.03 and 0.06 m•s−1 [46]. For the Gyko Sport model, the SEE values and Pearson’s r were 0.18 m•s−1 and r = 0.79, respectively [49]. For the Beast Sensor model, the SEE values were between 0.07 m•s−1 and 0.05 m•s−1 and Pearson’s r values were between 0.76 and 0.98 [24,34]. For the Myotest sensor model, the SEE values were between 0.01 m•s−1 and 26.6 m•s−1 and Pearson’s r values were between 0.38 and 0.92, and R2 values were between 0.59 and 0.97 [56,58,59,65,67,69]. For the PUSH Band sensor model, the SEE values were between 0.135 m•s−1 and 0.091 m•s−1 and Pearson’s r values were between 0.97 and 0.90, and R2 value was 0.85 [6,23,24,48,64,66]. For the Wimu RealTrack Systems sensor model, the SEE value was 0.030 m•s−1 and Pearson’s r values were between 0.009 and 0.60, and R2 values were between 0.95 and 0.77 [28,60,68]. For the PASCO sensor model, Pearson’s r values were between 0.84 and 0.93 [61,70].

Table 4.

Validity of IMU for estimation of barbell velocity.

3.5. Results of Individual Studies: Reliability of IMU for Estimation of Barbell Velocity

Information of the reliability levels obtained in the included studies can be found in Table 5. Generally, the Barsensei model was the only model not being considered reliable for more than one article [27,46]. The remaining models presented evidence of reliability.

Table 5.

Reliability of IMU for estimation of barbell velocity.

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify and summarize studies that have examined the validity of wearable wireless IMUs for measuring barbell velocity and identify and summarize studies that have examined the reliability of IMUs for measuring barbell velocity. The IMUs in this study were compared with gold standards and previously tested devices as reference systems (i.e., linear transducers [56,58,59,60,67], a contact platform [69], the field computation method [24,61,64,65,66,70], and a motion capture system).

IMUs were evaluated during movements generally geared toward strength training. The studies investigated in this review included the following movements: the back squat [1,23,24,34,49,58,64,66,69]; the bench press [34]; the hip thrust [58]; the bench throw [23]; the prone bench pull [60,67]; the countermovement jump [61]; the power snatch, clean, and jerk [48]; and the hexagonal barbell deadlift. Validity and reliability studies of IMUs during Olympic lifts are quite limited [61], and thus it is believed that IMUs should be tested for different parts of the Olympic lifts.

In total, eight IMU models were used in the studies examined in this systematic review. Some studies were conducted using the BarSensei [27,46], the Gyko [49], the Myotest [56,58,59,65,67,69], the PUSH Band [23,24,48,54,64,66], the Wimu Real Track [6,60,62,68], the PASCO [61,70], and the Rehagait [63].

4.1. Validity of IMU for Estimation of Barbell Velocity

Twenty-one of the studies in this systematic review investigated validity (see Table 4). Specifically, IMU were compared with linear transducers in seven studies, a contact platform in six studies, the field computation method in one study, and a motion capture system in six studies (see Table 4 to a detail information). Among the included studies, nine tested the back squat; nine the bench press; one the hip thrust; one the bench throw; one the prone bench pull; two the countermovement jump; one the power snatch, clean, and jerk; and one the hexagonal barbell deadlift.

Overall, eight different IMU models were tested for validity. The reviewed studies were conducted using the BarSensei [27,46], the Gyko [49], the Myotest [56,58,59,65,67,69], the PUSH Band [23,24,48,54,64,66], the Wimu Real Track [6,60,62,68], the PASCO [61,70], and the Rehagait [63]. Four studies [27,46,60,67] reported a lack of validity of IMU equipment.

Validity studies also compared the different pieces of equipment with which IMUs were compared. The most detailed investigations are those tested with 3D camera measurement systems and force platforms, which are the gold standard. The variety of equipment used for validity comparisons can lead to differences. Differences in diversity between devices may be due to different sampling methods and the way raw data signals are processed in the software. Therefore, practitioners of IMUs should avoid using different devices interchangeably during the long-term monitoring of athletes.

The statistical methods and working designs of the equipment tested for validity differed. According to brands and methods for the BarSensei model used to test the validity of the findings of IMUs, the SEE values of validity were between 0.03 and 0.06 m•s−1 [46]. For the Gyko Sport model, the SEE and Pearson’s r values were 0.18 m•s−1 and 0.79, respectively [49]. For the Beast Sensor model, the SEE values ranged between 0.07 and 0.05 m•s−1, and Pearson’s r values ranged between 0.76 and 0.98 [24,34]. For the Myotest sensor model, the SEE values ranged between 0.01 and 26.6 m•s−1, Pearson’s r values ranged between 0.38 and 0.92, and the R2 values ranged between 0.59 and 0.97 [56,58,59,65,67,69]. For the PUSH Band sensor model, the SEE values ranged between 0.135 and 0.091 m•s−1, Pearson’s r values ranged between 0.97 and 0.90, and the R2 values were around 0.85 [6,23,24,48,64,66]. For the Wimu RealTrack Systems sensor model, the SEE values were around 0.030 m•s−1, Pearson’s r values ranged between 0.009 and 0.60, and the R2 values ranged between 0.95 and 0.77 [28,60,68]. For the PASCO sensor model, Pearson’s r values ranged between 0.84 and 0.93 [61,70]. For the Barsensei model, the SEE values of validity were between 0.03 and 0.06 m•s−1 [46]. For the Gyko Sport model, the SEE values and Pearson’s r were 0.18 and 0.79, respecitvely [49]. For the Beast Sensor model, the SEE values were between 0.07 and 0.05 m•s−1 and Pearson’s r values were between 0.76 and 0.98 [24,34]. For the Myotest sensor model, the SEE values were between 0.01 and 26.6 m•s−1, Pearson’s r values were between 0.38 and 0.92, and R2 values were between 0.59 and 0.97 [56,58,59,65,67,69]. For the PUSH Band sensor model, the SEE values were between 0.135 m and 0.091 m•s−1, Pearson’s r values were between 0.97 and 0.90, and R2 value was 0.85 [6,23,24,48,64,66]. For the Wimu RealTrack Systems sensor model, the SEE value was 0.030 m•s−1, Pearson’s r values were between 0.009 and 0.60, and R2 values were between 0.95 and 0.77 [28,60,68]. For the PASCO sensor model, Pearson’s r values were between 0.84 and 0.93 [61,70].

Considering the scenarios in which instruments may not be recommended, we found that the Wimu and Myoset may not be appropriate for measuring countermovement jumps, while Barsensei is not recommended for measuring velocity in squat and back squat exercises. The Myotest, Push Bando, Wimu, and Pasco revealed validity for measuring the main weight-room exercises such as bench press, bench throw, squat (front and back), or deadlift. The experience or type of competitive level of the participants had no effect on the tests.

In light of the findings revealed in the systematic review, sports scientists and practitioners should question the validity of the IMUs they use during exercises. Even if they do not have appropriate conditions to validate UMIs, it is recommended that they use validated equipment as shown by the data discussed in this systematic review.

4.2. Reliability of IMU for Estimation of Barbell Velocity

Twenty-one of the studies in this systematic review investigated reliability (see Table 5). Overall, seven different IMU models were tested for reliability. The studies were conducted using the BarSensei [27,46], the Gyko [49], the Myotest [56,57,58,65,67,69], the PUSH Band [23,24,48,64,66], the Wimu Real Track [6,60,62,68], and the PASCO [61]. Four studies [24,27,46,67] reported a lack of reliability in IMU equipment. The movements in which the equipment was tested in these studies reporting low reliability, the participant group, and biological differences should also be considered.

Reliability findings of IMUs, according to the brands and methods for the BarSensei model, the ICC values of validity were between 0.273 and 0.451, and the CV values ranged between 10% and 30% [27,46]. For the Gyko Sport model, the ICC value of reliability was 0.774 [49]. For the Beast Sensor model, the ICC values of reliability were between 0.36 and 0.99, and the CV values were around 35% [24,32]. For the Myotest model, the ICC values of reliability were between 0.35 and 0.97, the CV values were between 2.1% and 36.5%, and the SEM values of reliability were between 3% and 990 [56,57,58,65,67]. For the PUSH Band model, the ICC values of reliability were between 0.58 and 0.97, the CV values were between 4.2% and 13.7%, and the SEM values of the reliability were between 0.008 and 9.34 m•s−1 [23,24,48,64,66]. Depending on the number of studies, the PUSH BAND appears to be the IMU-based device that provides the most reliable data. For the Wimu RealTrack Systems model, the ICC values of reliability were between 0.81 and 0.97, the CV values were between 2.60% and 17%, and the SEM values of the reliability were between 0.007 and 0.11 m•s−1 [60,62,68]. For the PASCO model, the ICC values of reliability were between 0.95 and 0.99, and the SEM values of the reliability were between 0.55 and 1.77 m•s−1 [61].

In brief, the Myotest did not reveal enough levels of precision (reliability) for measuring countermovement jump, while Barsensei was not precise for measuring velocity in squat and back squat exercises. The Myotest, Push Bando, Wimu, and Pasco revealed precision for measuring the main weight-room exercises such as bench press, bench throw, squat (front and back), or deadlift. This is extremely important since instruments must be as must precise as possible in order to provide useful and sensitive information about readiness monitoring in sports, particularly for VBT.

The studies discussed in this systematic review investigated the reliability of the devices in certain movement patterns in field conditions. According to the authors, it is thought that studies on the long-term use of investigations of the reliability of IMUs should be designed to minimize the variables that might arise as a result of biological differences in longer use. However, it is also thought that malfunctions in the software data flow originating from the manufacturer may occur, and the disruptions in this data flow may affect the data reliability in IMUs. It is thought that research should be conducted to examine whether software and mobile phone applications that reflect instant data of IMU models transmit data reliably in real time. Among the studies discussed in this systematic review, none considered this situation. At the same time, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no study in the literature that investigates the effects of software data flows on reliability.

4.3. Study Limitations, Future Research, and Practical Implications

Most of the research in this systematic review examined the validity and reliability of IMUs during movements performed in a single plane. This systematic review only tested the validity and reliability of the Flores et al. [61] Olympic lifts and IMUs. Practitioners, sports scientists, and strength and conditioning coaches often use multi-directional Olympic lifts as opposed to the limited movement patterns used in research. Future studies should examine the validity and reliability of IMUs during the Olympic lifts that appear as a dark zone.

The studies discussed in this systematic review generally consist of short-term research designs. Since IMUs are used by people with biological differences, it should be considered that long-term biological changes may affect the validity and reliability of IMUs in the long term. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no studies examining the validity and reliability of long-term IMUs. For this reason, future studies should examine the validity and reliability of data to uncover insights about the long-term use of IMUs.

There may be some factors affecting the validity and reliability of IMUs beyond those that researchers have considered in their experimental designs. Some of these factors may be caused by the manufacturer. For example, it is believed that data transferred to software and mobile phone applications in real time result in errors in validity and reliability due to software malfunctions. In order for sports scientists, practitioners, and strength training coaches to use IMUs in a valid and reliable way, the effects of software factors on data quality should be investigated in future studies.

Table 6 presents a summary of the validity and reliability of different IMUs that may help coaches choose a model.

Table 6.

Summary of validity and reliability of different IMU models.

5. Conclusions

This present systematic review summarized evidence about the validity and reliability of IMUs for measuring barbell velocity. A total of eight models were tested across the 22 included articles. The Barsensei was not valid and reliable in the studies reports. The Gyko sport, Beast Sensor, and PASCO were valid and reliable in all reports. The Myotest, PUSH band, and Wimu RealTrack were valid and reliable in the majority of the reports. The Rehagait was valid. Therefore, from the eight included models, seven can be used with some evidence of being accurate and precise. This evidence provides important information for coaches who need accurate information about barbell velocity to control the external load imposed on athletes and to be sensitive to human variations without any meaningful bias generated by measurement instruments.

Author Contributions

F.M.C. lead the project, established the protocol, and wrote and revised the original manuscript. J.P.-O. and Z.A. wrote and revised the original manuscript. M.R.-G. ran the data search and methodological assessment and wrote and revised the original manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia/Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior, through national funds and when applicable co-funded EU funds under the project UIDB/50008/2020. No other specific sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mann, J.B.; Ivey, P.A.; Sayers, S.P. Velocity-based training in football. Strength Cond. J. 2015, 37, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, H.G.; Tufano, J.J.; Delgado, J.; Thompson, S.W.; Nosaka, K. Comparison of the effects of velocity-based training methods and traditional 1RM-percent-based training prescription on acute kinetic and kinematic variables. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2019, 14, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, A.; Varalda, C.; Piacentini, M. The role of velocity based training in the strength periodization for modern athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2018, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orange, S.T.; Metcalfe, J.W.; Robinson, A.; Applegarth, M.J.; Liefeith, A. Effects of in-season velocity versus percentage-based training in Academy Rugby League players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2020, 15, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Badillo, J.J.; Pareja-Blanco, F.; Rodríguez-Rosell, D.; Abad-Herencia, J.L.; del Ojo-López, J.J.; Sánchez-Medina, L. Effects of velocity-based resistance training on young soccer players of different ages. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, J. Autoregulated resistance training. Strength Cond. J. 2019, 41, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindiani, M.; Lazarus, A.; Iacono, A.D.; Halperin, I. Perception of changes in bar velocity in resistance training: Accuracy levels within and between exercises. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 224, 113025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; McLaren, S.; Ramirez-Lopez, C.; García-Ramos, A.; Dalton-Barron, N.; Banyard, H.; Mann, B.; Weaving, D.; Jones, B. Application of velocity loss thresholds during free-weight resistance training: Responses and reproducibility of perceptual, metabolic, and neuromuscular outcomes. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, A.; Doma, K.; Yamashita, D.; Hasegawa, H.; Mori, S. The effect of augmented feedback type and frequency on velocity-based training-induced adaptation and retention. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 3110–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, A.D.; Cronin, J.B.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Gill, N.D.; Pedersen, M.C. Effect of instantaneous performance feedback during 6 weeks of velocity-based resistance training on sport-specific performance tests. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; Mann, B.; Banyard, H.; McLaren, S.; Scott, T.; Garcia-Ramos, A. Velocity-based training. Strength Cond. J. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.M.; Núñez, V.M.; Lancho, C.; Poblador, M.S.; Lancho, J.L. Velocity-based training of lower limb to improve absolute and relative power outputs in concentric phase of half-squat in soccer players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 3084–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauch, J.; Loturco, I.; Cheesman, N.; Thiel, J.; Alvarez, M.; Miller, N.; Carpenter, N.; Barakat, C.; Velasquez, G.; Stanjones, A.; et al. Similar strength and power adaptations between two different velocity-based training regimens in collegiate female volleyball players. Sports 2018, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridis, L.; Pálinkás, G.; Tróznai, Z.; Béres, B.; Utczás, K. Determining strength training needs using the force-velocity profile of elite female handball and volleyball players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach 2021, 16, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, L.; Chéry, C.; Taylor, K.-L. Validity and reliability of the load-velocity relationship to predict the one-repetition maximum in deadlift. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loturco, I.; Suchomel, T.; Kobal, R.; Arruda, A.F.S.; Guerriero, A.; Pereira, L.A.; Pai, C.N. Force-velocity relationship in three different variations of prone row exercises. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, H.G.; Nosaka, K.; Haff, G.G. Reliability and validity of the load–velocity relationship to predict the 1RM back squat. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 1897–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Sakai, T.; Kato, S.; Hashizume, N.; Horii, N.; Yoshikawa, M.; Hasegawa, N.; Iemitsu, K.; Tsuji, K.; Uchida, M.; et al. Conduction velocity of muscle action potential of knee extensor muscle during evoked and voluntary contractions after exhaustive leg pedaling exercise. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twomey, R.; Aboodarda, S.J.; Kruger, R.; Culos-Reed, S.N.; Temesi, J.; Millet, G.Y. Neuromuscular fatigue during exercise: Methodological considerations, etiology and potential role in chronic fatigue. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 47, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Custodio, R.; Rodríguez-Rosell, D.; Yáñez-García, J.M.; Sánchez-Moreno, M.; Pareja-Blanco, F.; González-Badillo, J.J. Effect of different inter-repetition rest intervals across four load intensities on velocity loss and blood lactate concentration during full squat exercise. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 2856–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, H.G.; Nosaka, K.; Vernon, A.D.; Haff, G.G. The reliability of individualized load–velocity profiles. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, B.B.; Banyard, H.; Cormack, S.J.; Newton, R.U. Validity and reliability of methods to determine barbell displacement in heavy back squats: Implications for velocity-based training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 3118–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Morán-Navarro, R.; Escribano-Peñas, P.; Chavarren-Cabrero, J.; González-Badillo, J.J.; Pallarés, J.G. Reproducibility and repeatability of five different technologies for bar velocity measurement in resistance training. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 47, 1523–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Castilla, A.; Piepoli, A.; Delgado-García, G.; Garrido-Blanca, G.; García-Ramos, A. Reliability and concurrent validity of seven commercially available devices for the assessment of movement velocity at different intensities during the bench press. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orange, S.T.; Metcalfe, J.W.; Marshall, P.; Vince, R.V.; Madden, L.A.; Liefeith, A. Test-retest reliability of a commercial linear position transducer (GymAware PowerTool) to measure velocity and power in the back squat and bench press. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grgic, J.; Scapec, B.; Pedisic, Z.; Mikulic, P. Test-retest reliability of velocity and power in the deadlift and squat exercises assessed by the GymAware PowerTool system. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckham, G.K.; Layne, D.K.; Kim, S.B.; Martin, E.A.; Perez, B.G.; Adams, K.J. Reliability and criterion validity of the Assess2Perform bar sensei. Sports 2019, 7, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramos, A.; Pérez-Castilla, A.; Martín, F. Reliability and concurrent validity of the Velowin optoelectronic system to measure movement velocity during the free-weight back squat. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2018, 13, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueo, B.; Lopez, J.J.; Mossi, J.M.; Colomer, A.; Jimenez-Olmedo, J.M. Video-based system for automatic measurement of barbell velocity in back squat. Sensors 2021, 21, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Pay, A.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Conesa-Ros, E.; Morán-Navarro, R.; Pallarés, J.G. Is the high-speed camera-based method a plausible option for bar velocity assessment during resistance training? Measurement 2019, 137, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kruk, E.; Reijne, M.M. Accuracy of human motion capture systems for sport applications; state-of-the-art review. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2018, 18, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Marchante, D.; Baz-Valle, E.; Alonso-Molero, I.; Jiménez, S.L.; Muñóz-López, M. Analysis of wearable and smartphone-based technologies for the measurement of barbell velocity in different resistance training exercises. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peart, D.J.; Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Shaw, M.P. Use of mobile applications to collect data in sport, health, and exercise science. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Kuzdub, M.; Poveda-Ortiz, P.; Campo-Vecino, J. Validity and reliability of the push wearable device to measure movement velocity during the back squat exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 1968–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Ghazilla, R.A.R.; Khairi, N.M.; Kasi, V. Reviews on various Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) sensor applications. Int. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2013, 1, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroganam, G.; Manivannan, N.; Harrison, D. Review on wearable technology sensors used in consumer sport applications. Sensors 2019, 19, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, S.; Meyer, F.; Gremeaux, V.; Dadashi, F.; Aminian, K. A sensor fusion approach to the estimation of instantaneous velocity using single wearable sensor during sprint. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueberschär, O.; Fleckenstein, D.; Warschun, F.; Kränzler, S.; Walter, N.; Hoppe, M.W. Measuring biomechanical loads and asymmetries in junior elite long-distance runners through triaxial inertial sensors. Sport. Orthop. Traumatol. 2019, 35, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Fischer, E.; Tunca, C.; Brahms, C.M.; Ersoy, C.; Granacher, U.; Arnrich, B. How we found our IMU: Guidelines to IMU selection and a comparison of seven IMUs for pervasive healthcare applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesida, Y.; Papi, E.; McGregor, A.H. Exploring the role of wearable technology in sport kinematics and kinetics: A systematic review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crang, Z.L.; Duthie, G.; Cole, M.H.; Weakley, J.; Hewitt, A.; Johnston, R.D. The validity and reliability of wearable microtechnology for intermittent team sports: A systematic review. Sport. Med. 2021, 51, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noamani, A.; Nazarahari, M.; Lewicke, J.; Vette, A.H.; Rouhani, H. Validity of using wearable inertial sensors for assessing the dynamics of standing balance. Med. Eng. Phys. 2020, 77, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Magalhaes, F.A.; Vannozzi, G.; Gatta, G.; Fantozzi, S. Wearable inertial sensors in swimming motion analysis: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, M.; Beato, M.; McErlain-Naylor, S.A. Inter-unit reliability of IMU step metrics using IMeasureU blue trident inertial measurement units for running-based team sport tasks. J. Sports Sci. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Gago, J.M.; Ramos-Merino, M.; Vallarades-Rodriguez, S.; Álvarez-Sabucedo, L.M.; Fernández-Iglesias, M.J.; García-Soidán, J.L. Innovative use of wrist-worn wearable devices in the sports domain: A systematic review. Electronics 2019, 8, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, J.C.; Wagle, J.P.; Sato, K.; Painter, K.; Light, T.J.; Stone, M.H. Validation of inertial sensor to measure barbell kinematics across a spectrum of loading conditions. Sports 2020, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.W.; Rogerson, D.; Dorrell, H.F.; Ruddock, A.; Barnes, A. The reliability and validity of current technologies for measuring barbell velocity in the free-weight back squat and power clean. Sports 2020, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic, M.; Jukic, I. Within-unit reliability and between-units agreement of the commercially available linear position transducer and Barbell-mounted inertial sensor to measure movement velocity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arede, J.; Figueira, B.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Leite, N. Validity and reliability of Gyko sport for the measurement of barbell velocity on the bench-press exercise. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2019, 59, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camomilla, V.; Bergamini, E.; Fantozzi, S.; Vannozzi, G. Trends supporting the in-field use of wearable inertial sensors for sport performance evaluation: A systematic review. Sensors 2018, 18, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.; Caulfield, B.; Ward, T.; Johnston, W.; Doherty, C. Wearable inertial sensor systems for lower limb exercise detection and evaluation: A systematic review. Sport. Med. 2018, 48, 1221–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsey, M.; Espinosa, H.; Shepherd, J.; Thiel, D. Inertial sensors for performance analysis in combat sports: A systematic review. Sports 2019, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.; Neville, J.; Stewart, T.; Cronin, J. Upper body activity classification using an inertial measurement unit in court and field-based sports: A systematic review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part P J. Sport. Eng. Technol. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, C. Data Extraction Template for Included Studies. Available online: https://cccrg.cochrane.org/sites/cccrg.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/det_2015_revised_final_june_20_2016_nov_29_revised.doc (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Bampouras, T.M.; Relph, N.S.; Orme, D.; Esformes, J.I. Validity and reliability of the Myotest Pro wireless accelerometer in squat jumps. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2013, 21, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, J.F.; Olson, N.M.; Taylor, S.T.; McLagan, J.R.; Shepherd, C.M.; Borgsmiller, J.A.; Mason, M.L.; Riner, R.R.; Gilliland, L.; Grisewold, S. Front squat data reproducibility collected with a triple-axis accelerometer. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comstock, B.A.; Solomon-Hill, G.; Flanagan, S.D.; Earp, J.E.; Luk, H.-Y.; Dobbins, K.A.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Fragala, M.S.; Ho, J.-Y.; Hatfield, D.L.; et al. Validity of the Myotest® in measuring force and power production in the squat and bench press. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2293–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crewther, B.T.; Kilduff, L.P.; Cunningham, D.J.; Cook, C.; Owen, N.; Yang, G.-Z. Validating two systems for estimating force and power. Int. J. Sports Med. 2011, 32, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A.; Floría, P.; Villacieros, J.; Muñoz-López, A. Maximum velocity during loaded countermovement jumps obtained with an accelerometer, linear encoder and force platform: A comparison of technologies. J. Biomech. 2019, 95, 109281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, F.J.; Sedano, S.; de Benito, A.M.; Redondo, J.C. Validity and reliability of a 3-axis accelerometer for measuring weightlifting movements. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2016, 11, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pinillos, F.; Latorre-Román, P.A.; Valdivieso-Ruano, F.; Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Párraga-Montilla, J.A. Validity and reliability of the WIMU ® system to measure barbell velocity during the half-squat exercise. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part P J. Sport. Eng. Technol. 2019, 233, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, P.G. Measurement of a squat movement velocity: Comparison between a RehaGait accelerometer and the high-speed video recording method called MyLift. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, J.; Augustus, S.; Austin, K.; Comfort, P.; McMahon, J.; Mundy, P.; Haff, G.G. The reliability and validity of the bar-mounted PUSH Band TM 2.0 during bench press with moderate and heavy loads. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzetti, S.; Lamparter, T.; Lüthy, F. Validity and reliability of simple measurement device to assess the velocity of the barbell during squats. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, G.A.; Flanagan, E.P.; O’Donovan, P.; Collins, D.J.; Kenny, I.C. Velocity based training: Validity of monitoring devices to assess mean concentric velocity in the bench press exercise. J. Aus Strength Cond 2018, 26, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, D.T.W.; Gill, N.D.; Cronin, J.B.; McGuigan, M.R. Is wireless accelerometry a viable measurement system for assessing vertical jump performance? Sports Technol. 2013, 6, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyor, J. Validity and reliability of a new device (WIMU®) for measuring hamstring muscle extensibility. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.; Samozino, P.; Morin, J.-B.; Morel, B. A simple method for assessing upper-limb force–velocity profile in bench press. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018, 13, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Smith, S.L.; Sands, W.A. Validation of an accelerometer for measuring sport performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).