Abstract

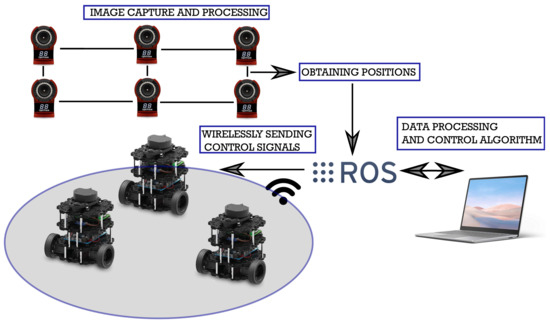

This paper presents a navigation strategy for a platoon of n non-holonomic mobile robots with a time-varying spacing policy between each pair of successive robots at the platoon, such that a safe trailing distance is maintained at any speed, avoiding the robots getting too close to each other. It is intended that all the vehicles in the formation follow the trajectory described by the leader robot, which is generated by bounded input velocities. To establish a chain formation among the vehicles, it is required that, for each pair of successive vehicles, the ()-th one follows the trajectory executed by the former i-th one, with a delay of units of time. An observer is proposed to estimate the trajectory, velocities, and positions of the i-th vehicle, delayed units of time, consequently generating the desired path for the ()-th vehicle, avoiding numerical approximations of the velocities, rendering robustness against noise and corrupted or missing data as well as to external disturbances. Besides the time-varying gap, a constant-time gap is used to get a secure trailing distance between each two successive robots. The presented platoon formation strategy is analyzed and proven by using Lyapunov theory, concluding asymptotic convergence for the posture tracking between the ()-th robot and the virtual reference provided by the observer that corresponds to the i-th robot. The strategy is evaluated by numerical simulations and real-time experiments.

1. Introduction

There are several mobile robot applications that take advantage of platooning strategies to improve performance or because of safety issues. Either at street vehicles or small mobile robot applications, a platoon is formed by a leading vehicle and a known group of follower vehicles that may not be aware of all the members that make up the squad, or all the information that comes from them, but usually each robot has information only from its predecessor.

The control of vehicle platoons has led to several approaches to deal with this problem, highlighting the follower vehicle scheme and the cooperative adaptive cruise control (CACC) [1,2]. Although, the control actions for a dynamic model of a vehicle (acceleration and steering) are different from a kinematic perspective (linear and rotational velocities), the strategies to render platoon formation are basically the same, and can be extrapolated to any type of mobile robot. The main goal is to ensure that the vehicles form a chain, maintaining a separation between them, dictated by a spacing policy, either distance or time based [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. In addition, string stability has to be guaranteed by assuring the attenuation of the effects of disturbances, caused by initial conditions, speed variations, or external disturbances, along the vehicle string [5,11,12,13].

As mentioned, platoon formation can be seen as a leader–follower problem considering pairs of successive vehicles at the chain, such as the framework presented in [14], where the leader–follower formation is converted into a trajectory tracking control problem, with the aim to keep a desired constant distance and a bearing angle between the follower and leader robots; the proposed control strategy considers both, the kinematic and dynamic models of a differential mobile robot, particularly of the TurtleBot. Simulation and experimental results show tracking of a desired trajectory for a triangle formation, however, it is observed that keeping a distance and bearing angle between leader and follower robots prevents the follower from performing exactly the same path of the leader, which is more obvious when moving into a curve, since the follower would develop a parallel curve with respect to the leader, or even an over steer or under steer curve depending on whether the follower is in the inner or outer side of the curve. Similar results are shown in [15], where a dispersed structure is forced as a formation to a group of non-holonomic mobile robots, such virtual structure is kept by defining relative distances and angles between the robots in the group. The aforementioned works are a type of constant spacing policy since they enforced constant distance and bearing angles between the robots in the formation. Other works based on the constant spacing policy are for instance [3,4,16,17,18,19]. As mentioned before, among vehicle platooning, there is a large number of works devoted to solving the longitudinal control of vehicles, without considering the lateral control [18,20,21], furthermore, either a punctual mass system or double integrator dynamics is commonly assumed, such as in [17,19,20], where platoon control is proposed to ensure a prescribed performance.

Several works under a time spacing scheme have been carried out in the past few years, see for instance [3,4,5,12,20,22]. A constant distance and time spacing policy are considered in [3] for platoons of differential drive mobile robots by using odometry information. In [12], a constant headway time is designed to obtain a graceful degradation of one-vehicle look-ahead CACC based on estimating the preceding vehicle’s acceleration. A delay-based spacing policy has been designed in [5] for the control of vehicle platoons considering disturbances and the string stability of the approximated model of the vehicles. Another delay-based spacing policy can be seen in [23,24], where an approach based on an input-delay observer to obtain a fixed time-gap separation is used for the differential drive of a mobile robot platoon.

It has been pointed out that a time spacing policy improves traffic efficiency compared to constant distance separations [12], because if the platoon moves at a slow speed, it will not be necessary to maintain a large distance between vehicles, which makes the string inefficient. For this reason, the use of variable separations as a function of the speed of the platoon is a method to improve performance. In a time spacing policy, most approaches consider that the velocity of the platoon should not approach zero, since if it is reduced, the vehicle separation will also approach zero and there could be a collision between the vehicles. For this reason, the present paper proposes an extension of the work developed in [23,24] where a fixed time-delay spacing policy is proposed, broadening the work to a time-varying spacing policy inspired by artificial potential fields, which ensures a safe distance between the members of the string, avoiding robots from getting too close to each other. Under these conditions, the work considers a squad of non-holonomic mobile robots, where each robot is intended to follow the position and orientation of its precedent vehicle in the formation, while maintaining a time-varying gap that avoids collisions when the robots approach each other. To accomplish this task, the ()-th robot will follow the path of the i-th robot, delayed by a time-varying gap, so an input-delay observer that estimates the trajectory to be executed by each ()-th robot is proposed, rendering robustness to the platoon against external disturbances. The presented scheme is proven by Lyapunov stability theory. The performance of the strategy was evaluated by numerical simulations and real-time experiments.

The rest of the document continues in Section 2, presenting the problem formulation associated with a set of n mobile robots type (2,0), represented by kinematic models. Further, the proposal of the time-varying spacing policy is analyzed. In Section 3, the design of an input-delayed observer to generate desired trajectories is presented, and in Section 4, the proposed navigation strategy is described in detail. Section 5 is devoted to the evaluation of the presented time-varying spacing policy through numerical evaluation and real-time experiments. A discussion of the performance of the proposed strategy based on the numerical simulation and experimental results is presented in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 presents the conclusions of the work.

2. Problem Formulation

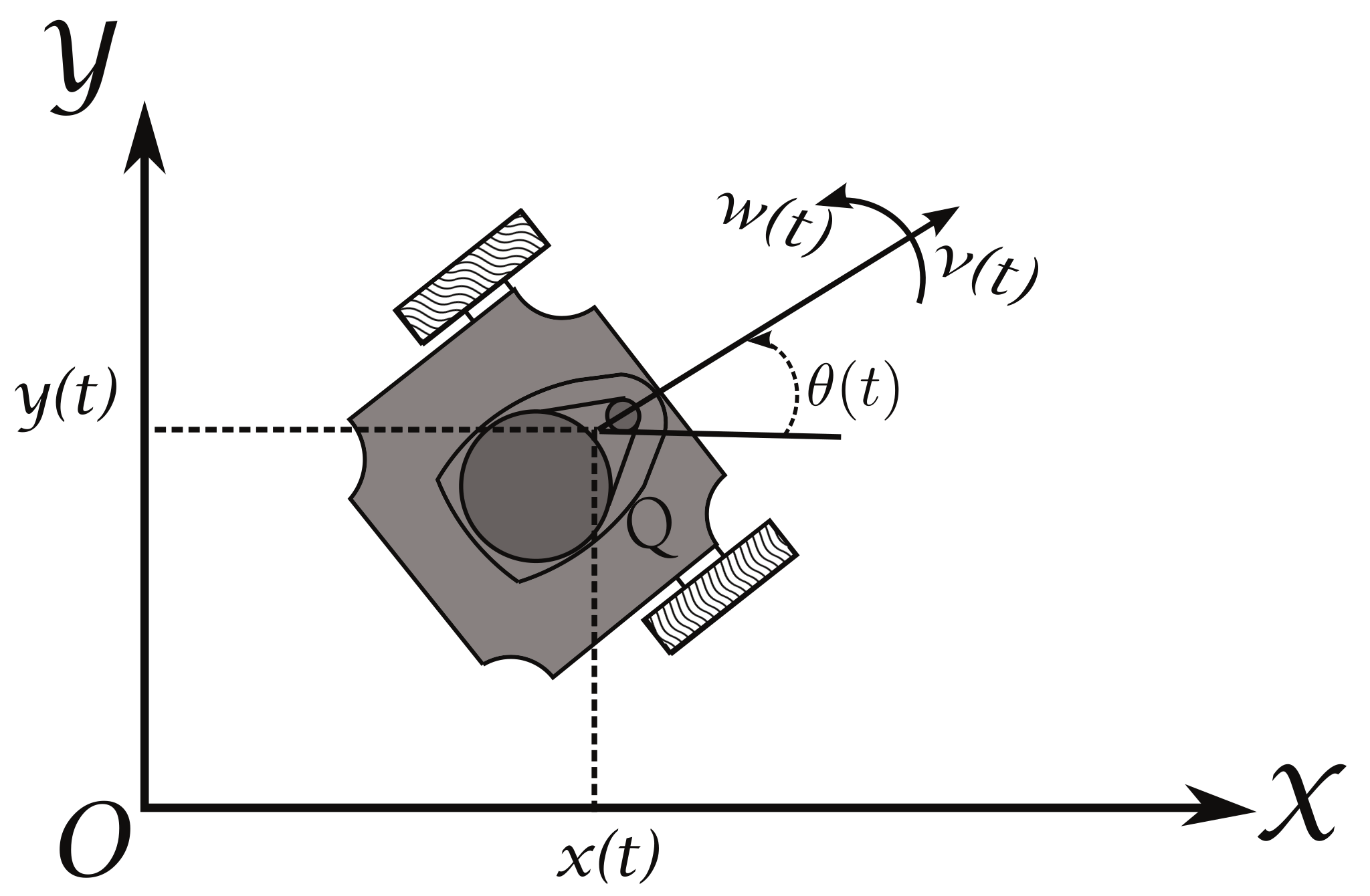

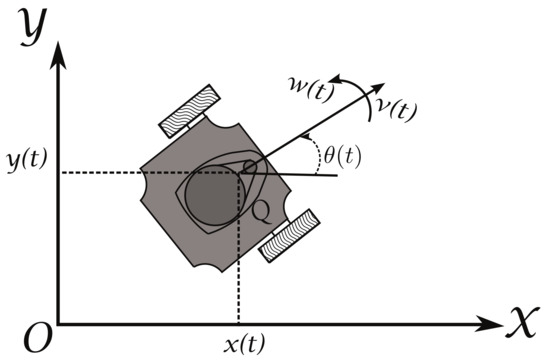

Take into account a set of n differential driven mobile robots that have two actuated wheels and move on the plane, as the one shown in Figure 1. The position, at time t, of the point Q, located at the midpoint of the robot’s wheels axis with respect to the global coordinate frame is denoted by the coordinates and , while the orientation is denoted by . The kinematic model of this robot can be obtained by the geometric interrelations shown in Figure 1 [25]; obtaining for the i-th robot,

where is the state vector of the system and are the input signals, in which, is the linear or translational velocity and is the angular velocity, with . It is assumed that the robot is a rigid mechanism that ideally moves on a flat surface, without friction, and must move only by the velocities exerted by the wheels, the vertical axes of the wheels are perpendicular to the ground where it moves, and the non-holonomic constraint,

is satisfied at all times.

Figure 1.

Differential driven mobile robot.

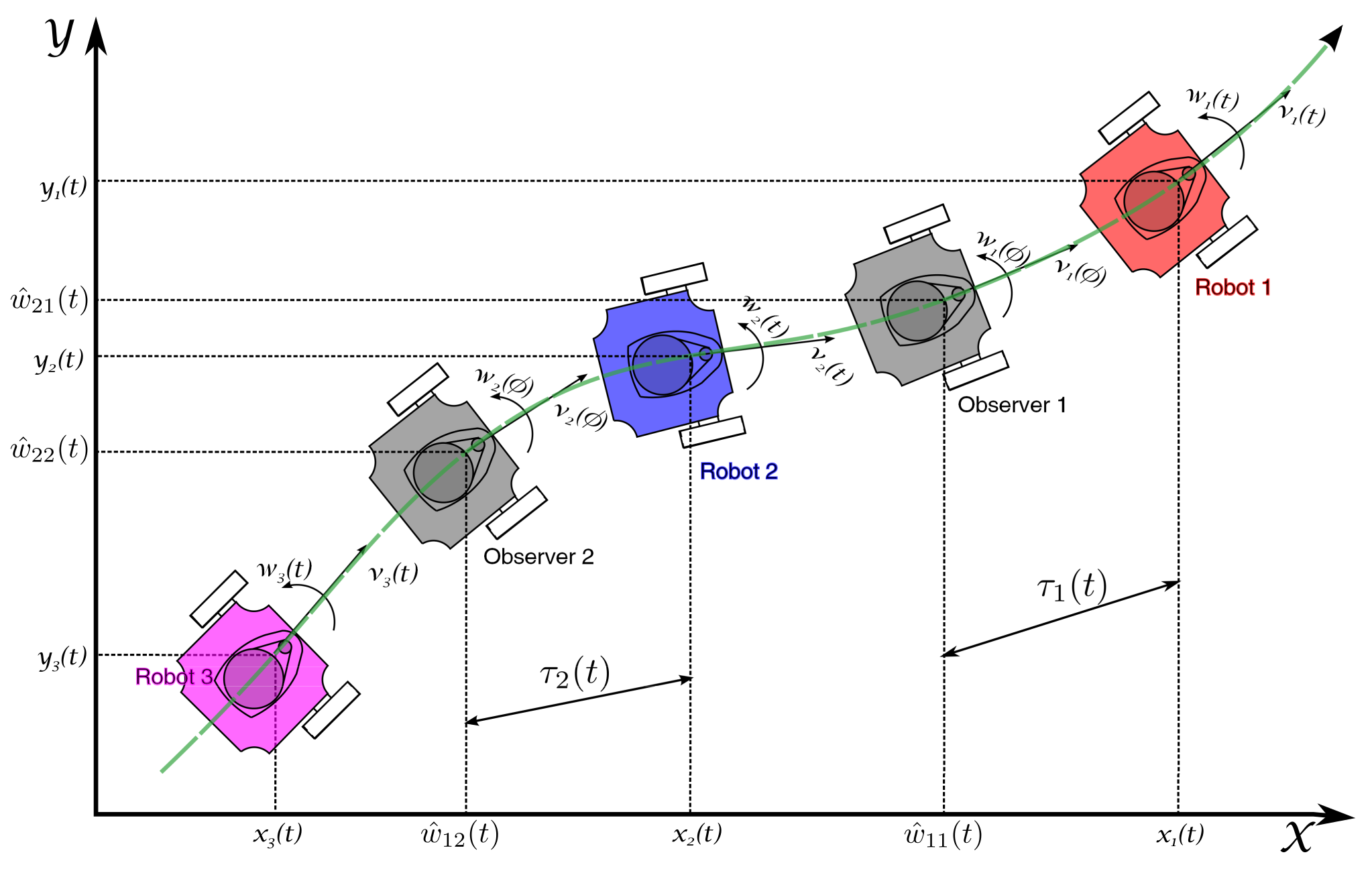

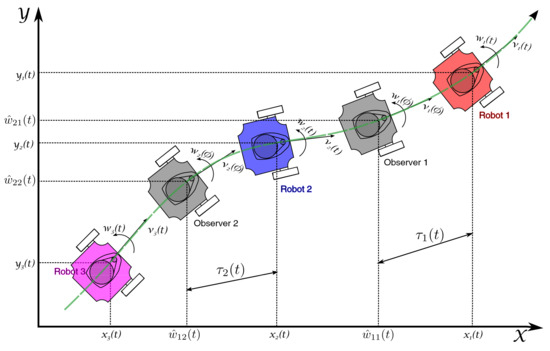

2.1. Platoon Formation

For the set of n wheeled mobile robots, a platoon formation problem is taken into consideration in which the first robot (, leader of the formation), performs any trajectory produced by bounded input velocities , , this is, only the leader knows the path to be performed by the platoon. Note that in the case of a vehicle car platoon, this assumption is satisfied by considering that the leader vehicle is driven by a human operator, who sets the traveling route. The platoon consists of a string formation topology, where the ()-th robot, for , will perform the trajectory of the i-th robot that is delayed by a specific time-varying gap , to maintain a time-varying spacing policy between successive robots. To obtain the delayed trajectory of the i-th robot in the formation, an input-delay observer is designed based on the position measurements of the i-th robot. The considered time-varying strategy is shown in Figure 2, where a convoy of three robots and two observers is presented. It is intended that the -th robot tracks the path provided by the i-th observer, for , maintaining the formation, while avoiding getting too close to each other.

Figure 2.

Time-varying gap formation strategy.

2.2. Spacing Policy

When considering a time spacing policy in a string formation, the platoon performance is improved with respect to fixed distance spacing policies [12], since in a time-gap strategy, the distance between any pair of successive robots is varying depending on the velocity of the members of the chain, decreasing for slow velocities and increasing otherwise. This strategy is intuitively applied by most human drivers when the speed of the vehicles decreases, for instance when vehicles approach a pedestrian crossing line or a red traffic light, where it is not necessary to keep a large inter-vehicle distance. Notice that in a fixed time-gap strategy reducing the traveling velocity may produce a collision situation, since the inter-vehicle distance also decreases. To avoid such a collision scenario, in this work, a time-varying spacing policy, inversely proportional to the distance between vehicles, is proposed based on the fixed-time spacing policy presented in [24]. It is considered a time-varying gap that increases its magnitude when the distance between vehicles reaches a threshold, which implies that the velocity of the formation is too slow. For this time-varying gap, the following assumption is taken into account.

The time-varying gap is proposed as,

where is a fixed time-gap, which keeps a distance among each pair of successive vehicles at the platoon, which also varies according to the velocity; is a time-varying gap that increases when the i-th and the -th robot approximate each other, rendering a safe distance. That is, adds a varying distance to the one induced by , and this varying distance is activated when slow velocities render a separation distance smaller than a desired magnitude.

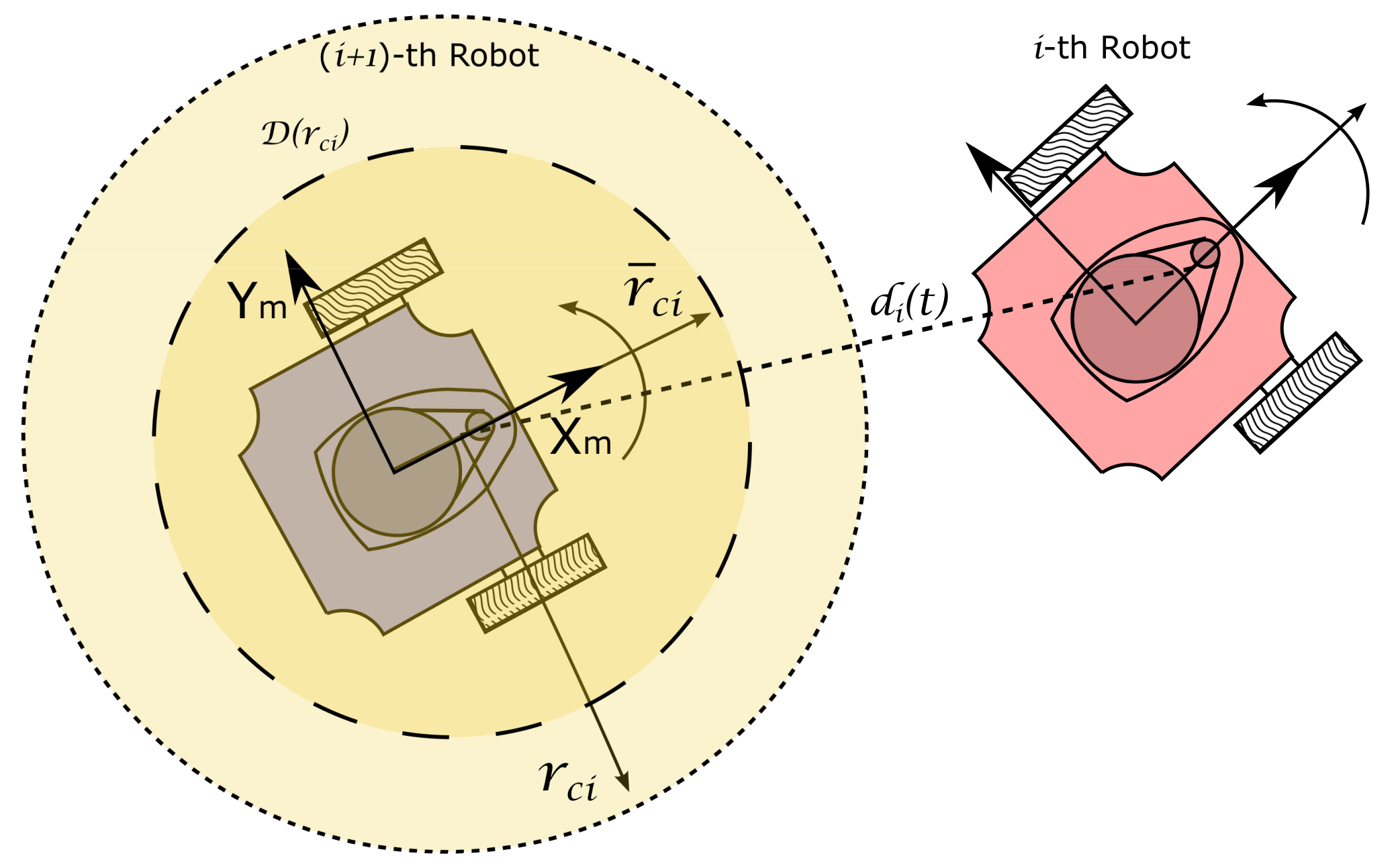

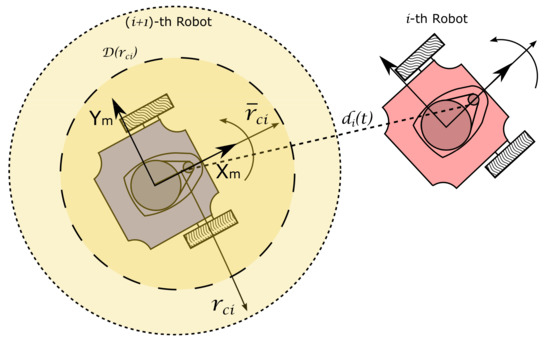

The time-varying gap should be a bounded non-negative differentiable function, whose value tends to increase as the -th robot approaches to the i-th robot. Inspired by [26], the time-varying component is proposed as,

where and are positive, non-zero constants that determine the zone where is defined, around the -th robot, see Figure 3. The parameter is a constant of proportionality and is the Euclidean distance between the position of the i-th and -th robot, this is,

Figure 3.

Time-varying gap configuration between two successive robots.

Using the Euclidean distance is conservative with respect to the distance between two successive vehicles along the path, nevertheless is rather easier to be determined by using onboard sensors, as well as by transmitted positions between the vehicles. Meanwhile, safe trailing distance and assured clear distance ahead (ACDA) are implicitly satisfied when considering standard distance between vehicles.

Note that the definition of , implies that it is bounded by below by zero. Thus, when the distance between vehicles is bigger than the desired safe distance, , the separation distance is the only function of the constant-time gap . Otherwise, when the separation distance between vehicles becomes smaller than the safe distance, the time-varying component tends to increase its magnitude to produce the desired safe distance. As a matter of fact, the behavior of the time-varying component increases and decreases the distance separation gap generated by the positive limits of , this is, .

The time derivative of the time-varying gap is given by , this is,

with,

where and .

Notice that the time-varying gap will increase its magnitude affecting the behavior of the ()-th robot, only when the i-th robot gets inside the influence zone defined over the mobile robot frame as,

of the ()-th robot, avoiding collisions between them, as depicted in Figure 3. The values of and of the constant time-gap must be chosen according to the size of the robot and the desired working conditions, particularly according to the desired safe distance, and the maximum rejection action, settled by the inner radio , which for zero value would imply an infinite action.

Remark 1.

It is important to point out that , in (3), is a bounded function independently of the position of the i-th and -th robots, this is, will be bounded since,

where the upper bound of could increase to infinity in the case that tends to zero. Notice also that by the definition of , from (6), will be also a bounded function. Therefore, the time-varying gap and its time derivative are bounded , in its region of definition, this is, and with .

Remark 2.

To determine the parameters involved in the influence zone , the following simple heuristic steps are proposed:

- (i)

- Determine depending on the physical structure of the robots.

- (ii)

- Propose the size of the influence zone by setting such that .

- (iii)

- Determine such that the increment produced on avoids a possible collision between involved successive robots. This parameter depends on the possible velocity of the robots.

3. Input-Delayed Observer

With the aim of estimating the delayed trajectory accomplished by the i-th robot, an input-delay observer is designed to provide the delayed position, orientation, and velocities of the i-th robot based on current measurements. The following assumptions are taken into account.

Assumption 1.

The posture of the i-th robot is available for measurement .

Assumption 2.

The input signals of the leader robot of the platoon (), are bounded , this is and with . Thus, a feasible trajectory to be followed by the robots at the platoon is generated.

Associated to the i-th robot, it is possible to define a time-varying function,

and the set of units of time delayed variables,

where it is assumed that .

Considering the kinematic model of the i-th robot (1), the time derivatives of the delayed states (9) are,

where,

Since the time-varying delayed dynamics (11) is a free delayed system, it is possible now to propose a nonlinear Luenberger-type observer with the intention that the estimated state converges to the one of the delayed dynamics (11). The proposed observer takes the form,

where and y are the observation errors defined as,

Note that the observation errors depend on the delayed variable that has to be injected to the observer. Due to the fact that the i-th robot state (1) can be measured (Assumption 1), the injection error in (12) is obtained by storing a segment of the trajectory of the i-th robot (1).

Convergence of the Observation Errors

In order to facilitate the analysis of the convergence properties of the observation errors (13), instead of considering the original inertial representation of the observer (12), the body frame representation is obtained by means of a rotation of the observation error in the form,

this is,

Taking the time derivative of the observation errors (15), it is obtained,

The convergence properties of the observation errors are formally presented in the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

Consider that the i-th robot satisfies Assumptions 1 and 2. Then, if , the states and their time derivatives , for , given by the observer (12), present exponentially convergence to the trajectory of the i-th robot delayed units of time.

Proof.

Suppose that leader of the platoon, robot (), satisfies Assumption 1 and 2, and assume that the second robot () follows the delayed trajectory of the leader robot, provided by the state of the time-varying delayed observer (12).

If robot 2 follows the delayed trajectory of robot 1, it is evident that robot 2 must have a set of bounded inputs that allows it to follow the desired trajectory. Assuming that the preceding arguments are valid until the ()-th robot, it is possible to consider that for the i-th robot, taking into consideration that for ,

exponentially converges to zero, then, the proof is reduced to demonstrate the convergence of errors and .

Defining,

it is possible to write,

where,

Notice that by Assumption 1, we obtain,

for . Therefore, is a fading exogenous signal for system (19) and tends to zero as approaches the origin, despite the evolution of and . Then, errors and converge to the origin according to the evolution of the disturbance-free system,

For the time-varying system (20) consider a candidate Lyapunov function given as,

The time derivative of (21) produces,

that establishes global exponential stability of the errors and . □

Remark 3.

Note that the provided observer (12) exponentially converge depending on the values , no matter what time delay is considered. Further, note that the convergence of the observer state to the delayed state of the i-th robot renders the delayed values of the desired velocities, that all together, provide the desired delayed path for the corresponding ()-th robot.

Remark 4.

It should be pointed out that observer (12) prevents using an approximate estimation of the velocities of the i-th robot, for example, by means of the so-called dirty derivative, that could be an obstacle for the observer-based closed loop stability analysis, which is presented in the next section. Furthermore, the use of the observer does not require storing a large amount of data, while rendering robustness against noise and corrupted or missing data as the observer acts as a natural filter.

Remark 5.

Notice that Assumption 2 corresponds to a physical constraint for the leader robot in the formation, which allows having a feasible trajectory for the entire platoon that will satisfy the non-holonomic constraint, (2), as soon as convergence of the observation errors is achieved.

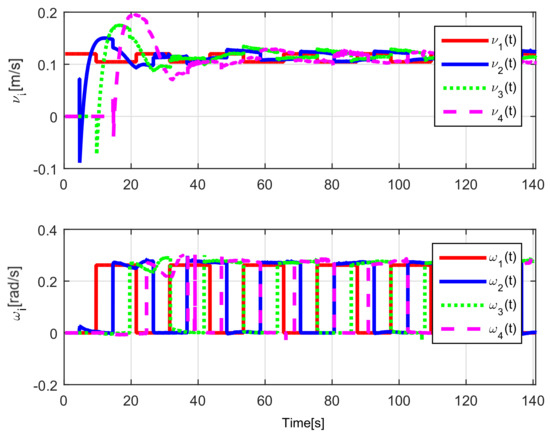

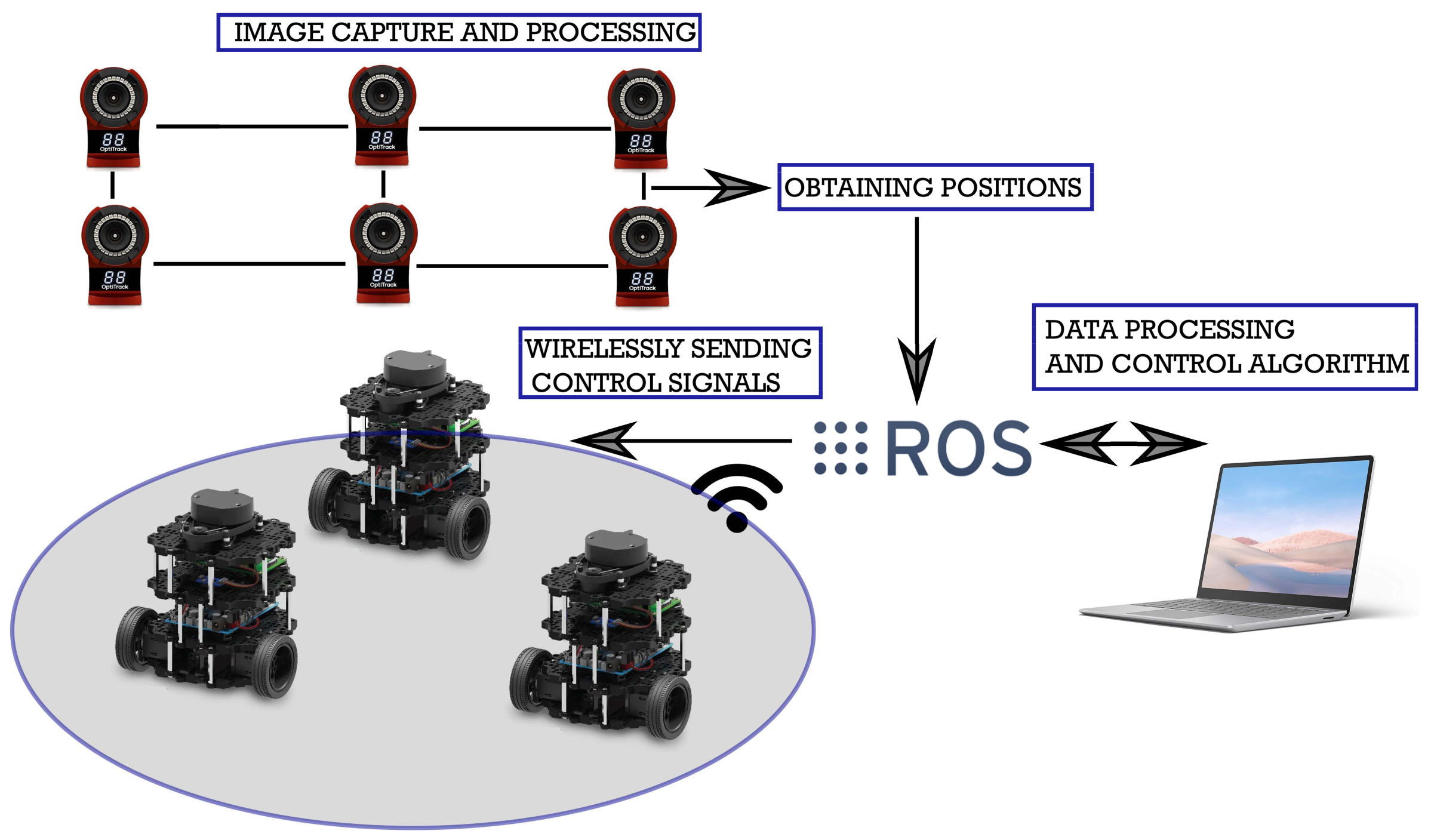

6. Results Discussion

At the introduction of the article, the state-of-the-art approaches were established for platoon formation strategies, as well as, for leader–follower setups. While designing the proposed time-varying spacing policy, a comparison to constant spacing policy was carried out, concluding that keeping constant distance and bearing angle between each pair of successive vehicles hinders the follower robots’ ability to perform the same path as described by the leader robot, mainly at curves. From these comparisons, it was evident that a varying distance and bearing angle are required at a curve. A similar comparison was performed with respect to time-based spacing policies, concluding that the space headway created by the separation time may render collisions when the translational velocity is small or tends to zero. However, for the sake of space, these comparison studies are not presented.

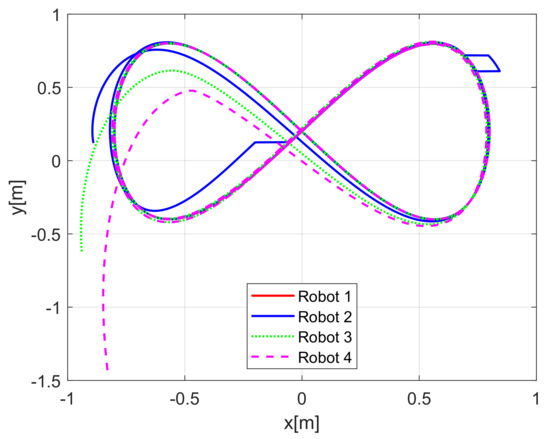

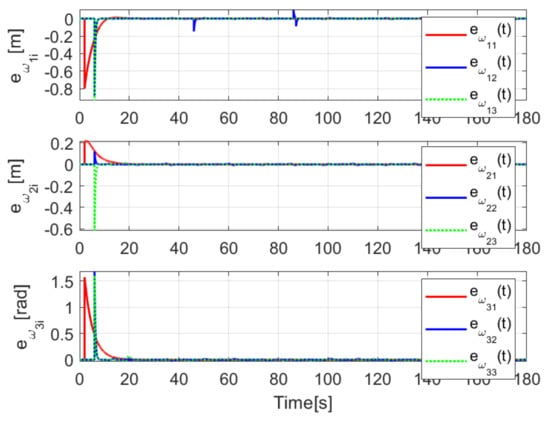

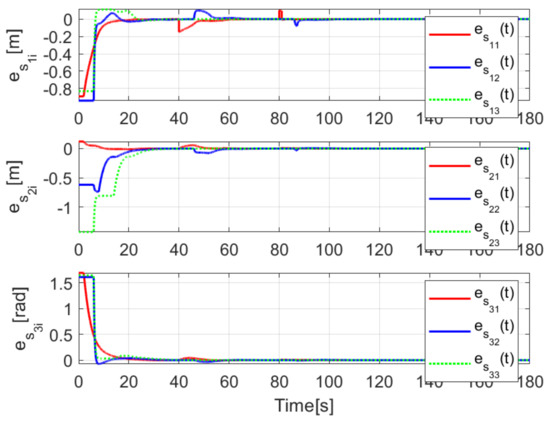

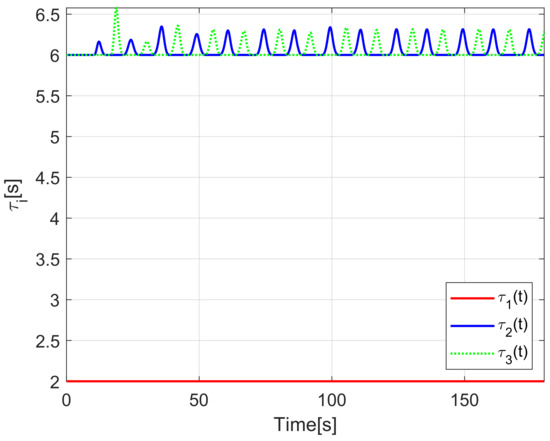

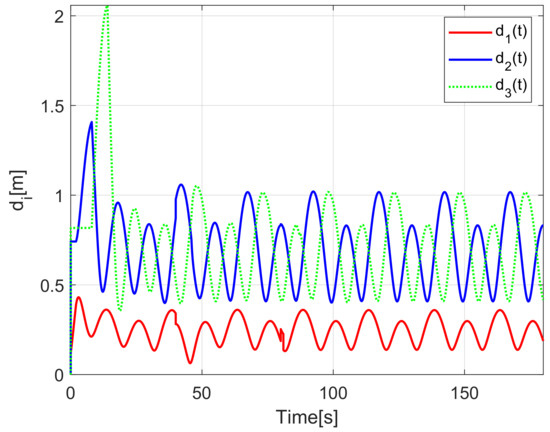

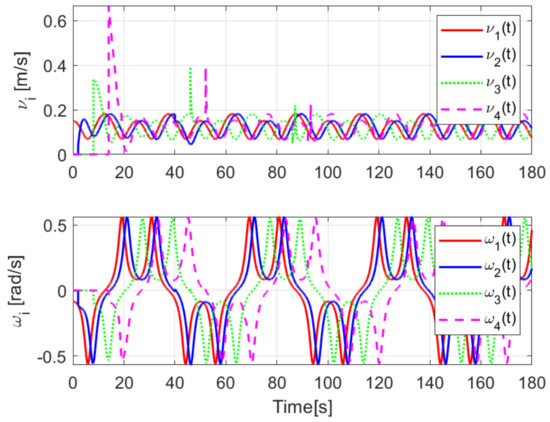

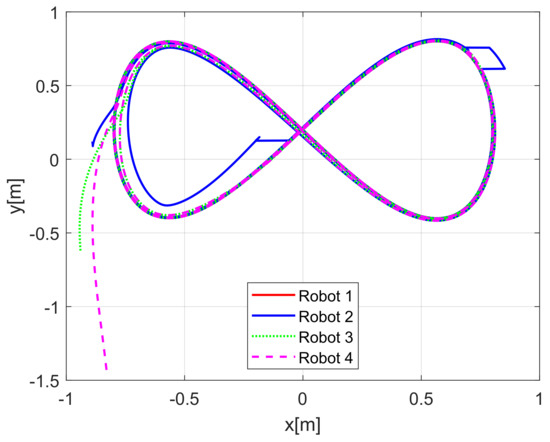

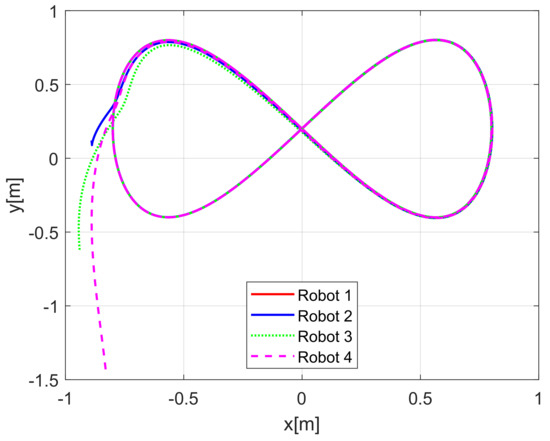

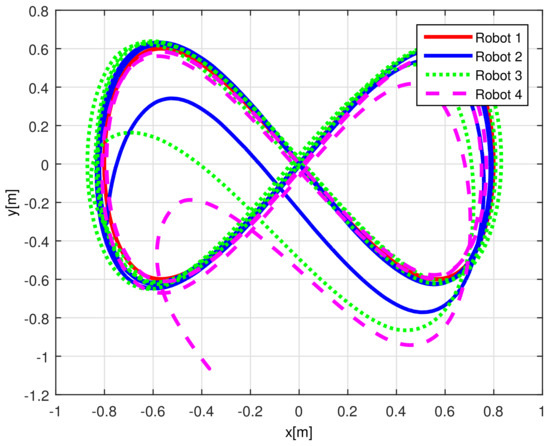

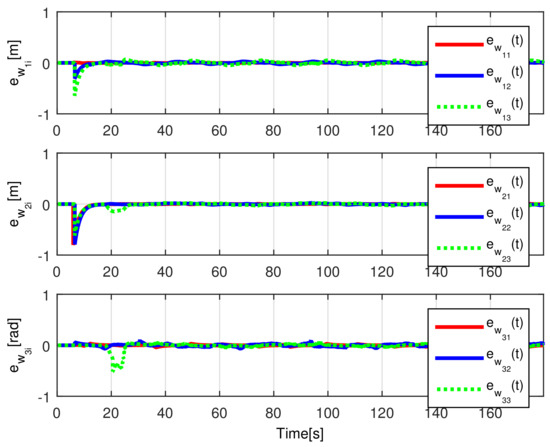

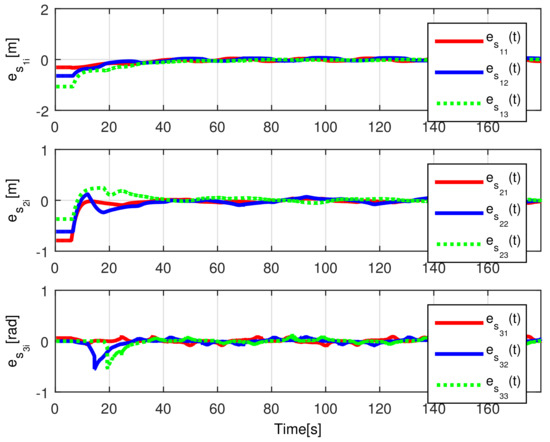

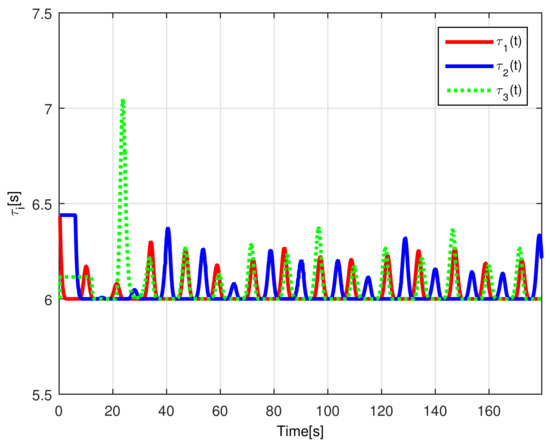

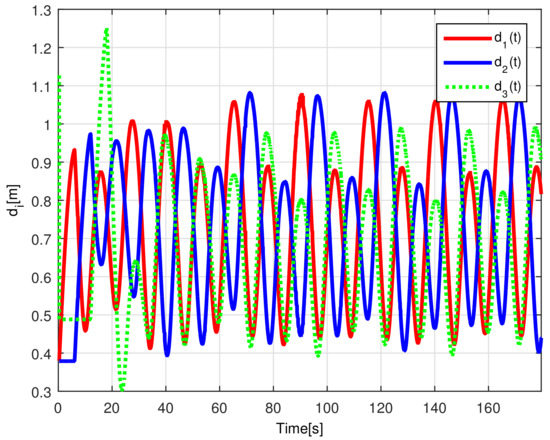

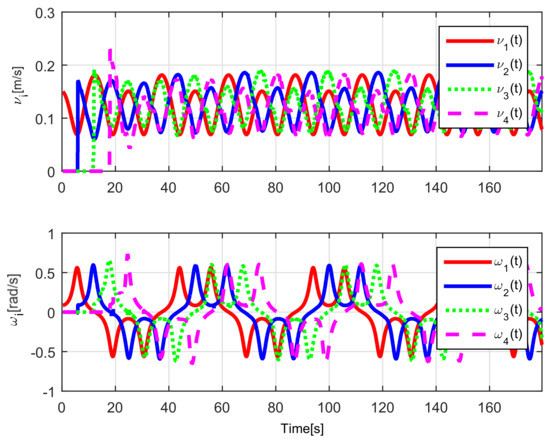

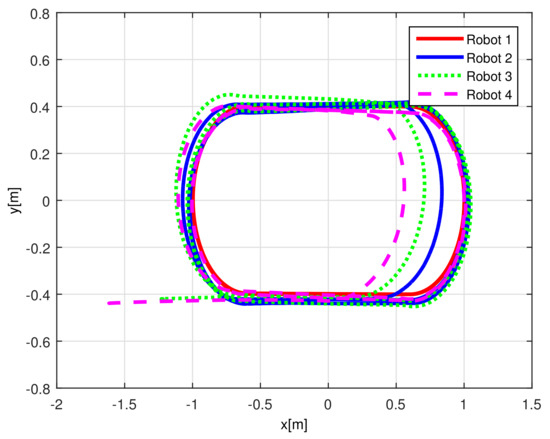

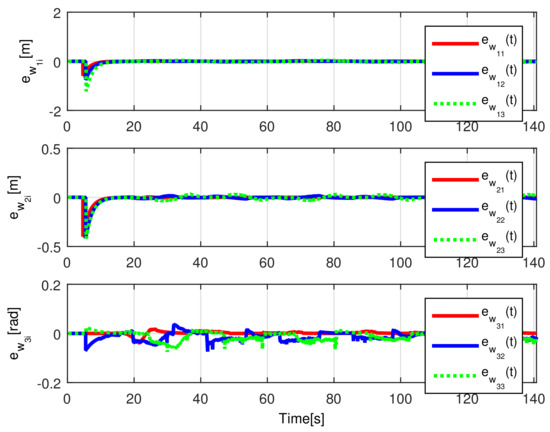

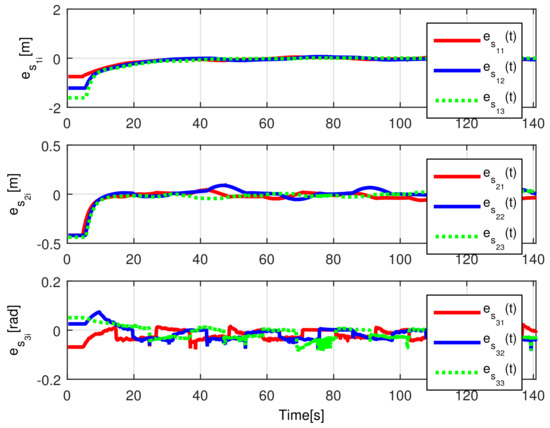

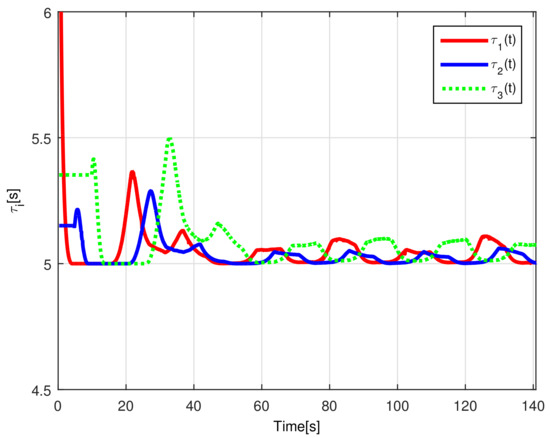

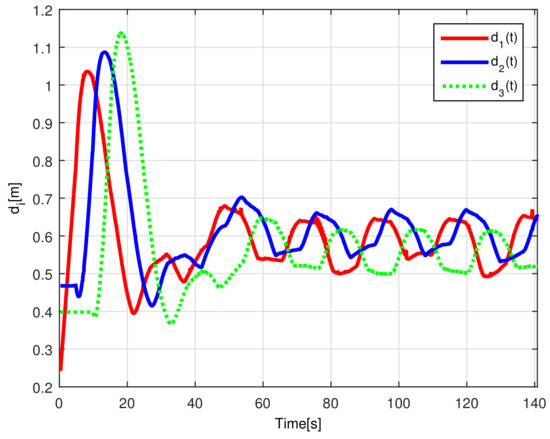

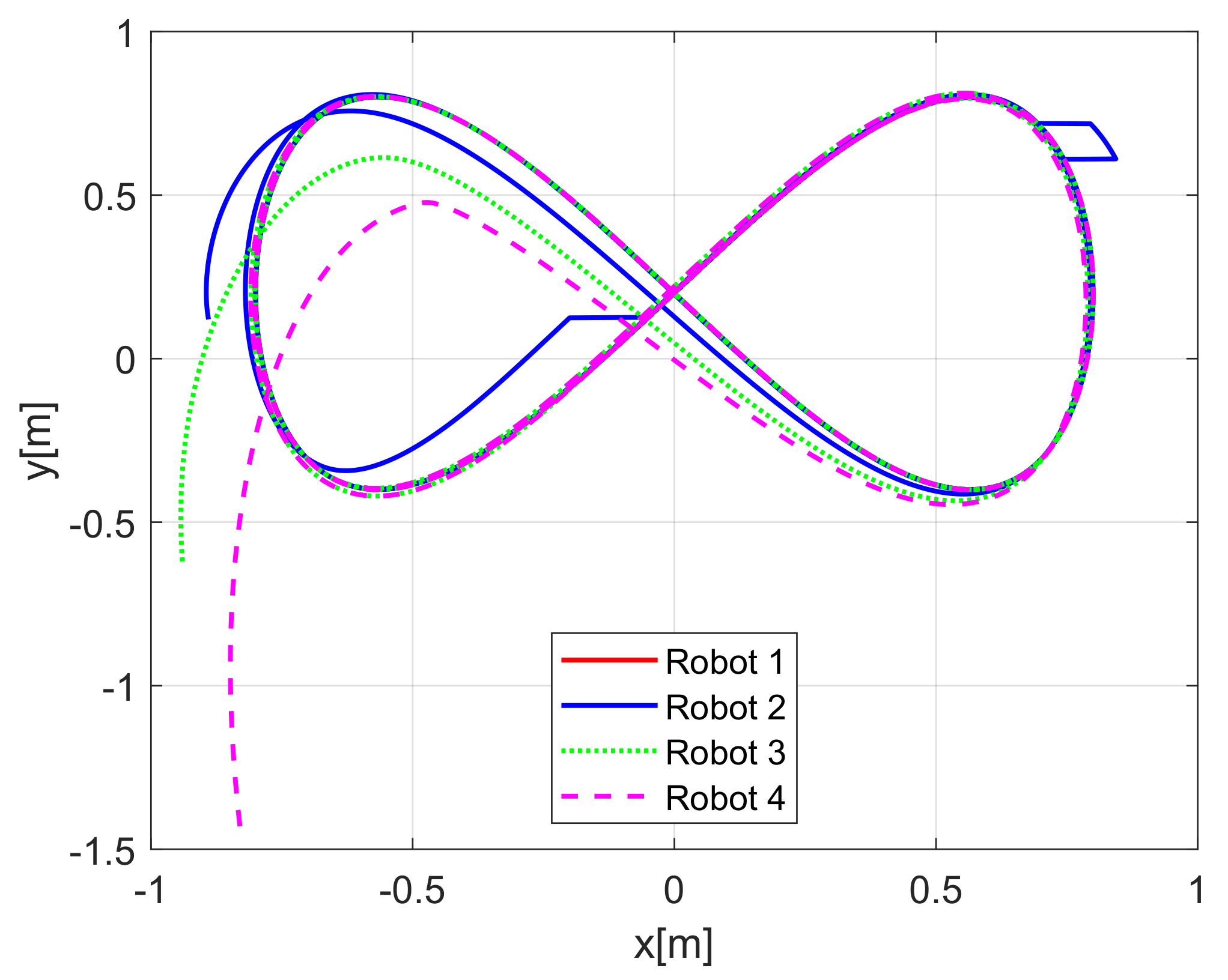

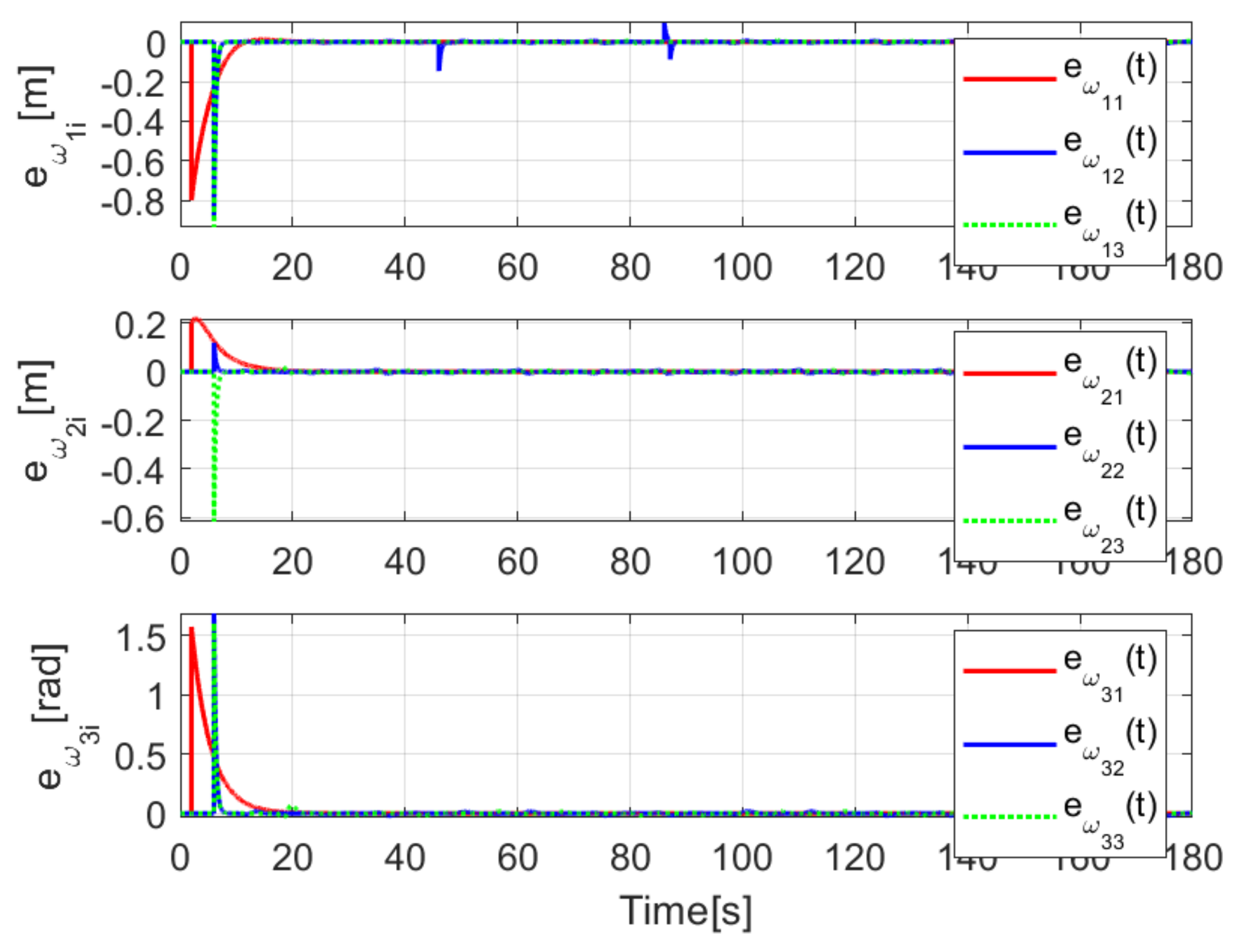

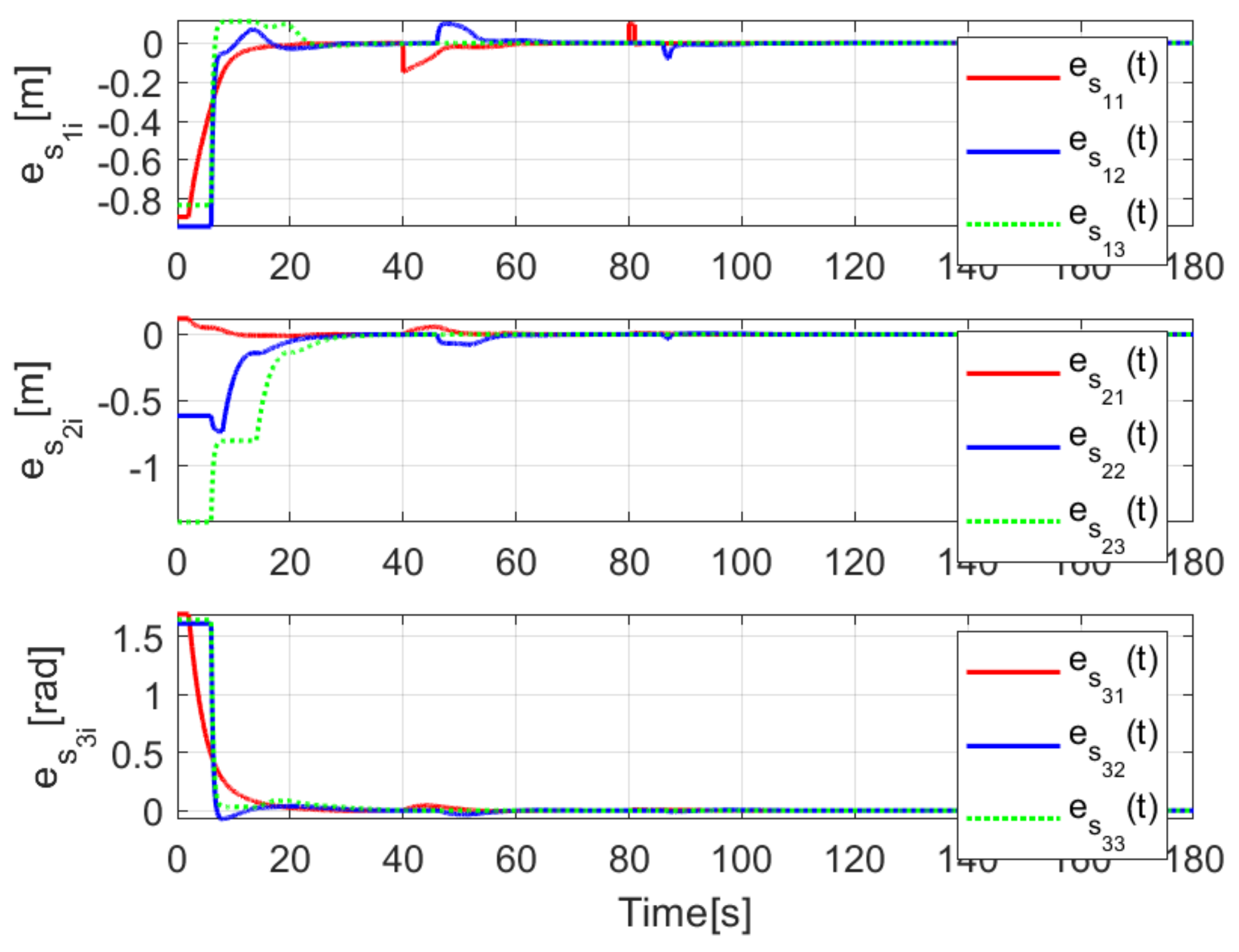

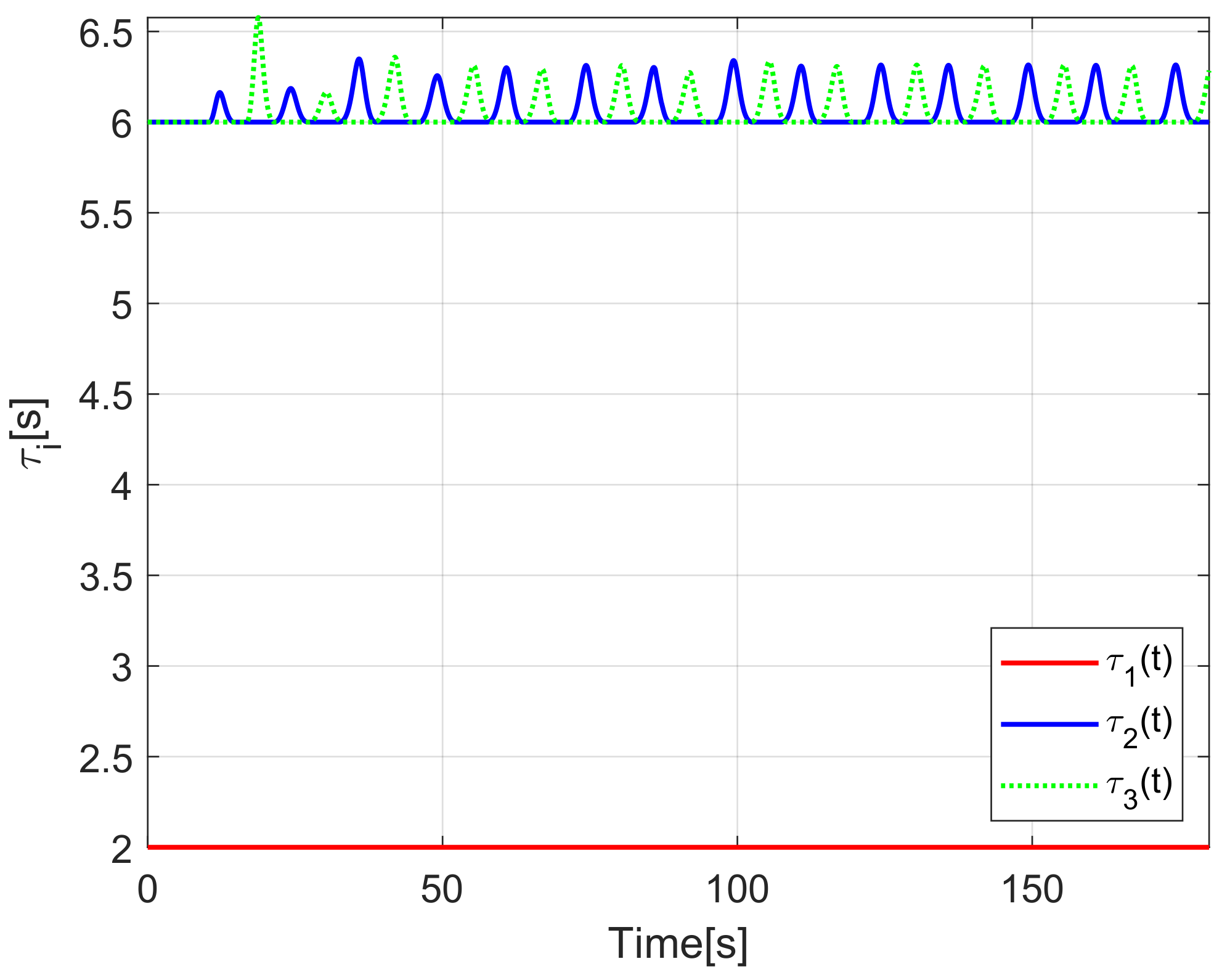

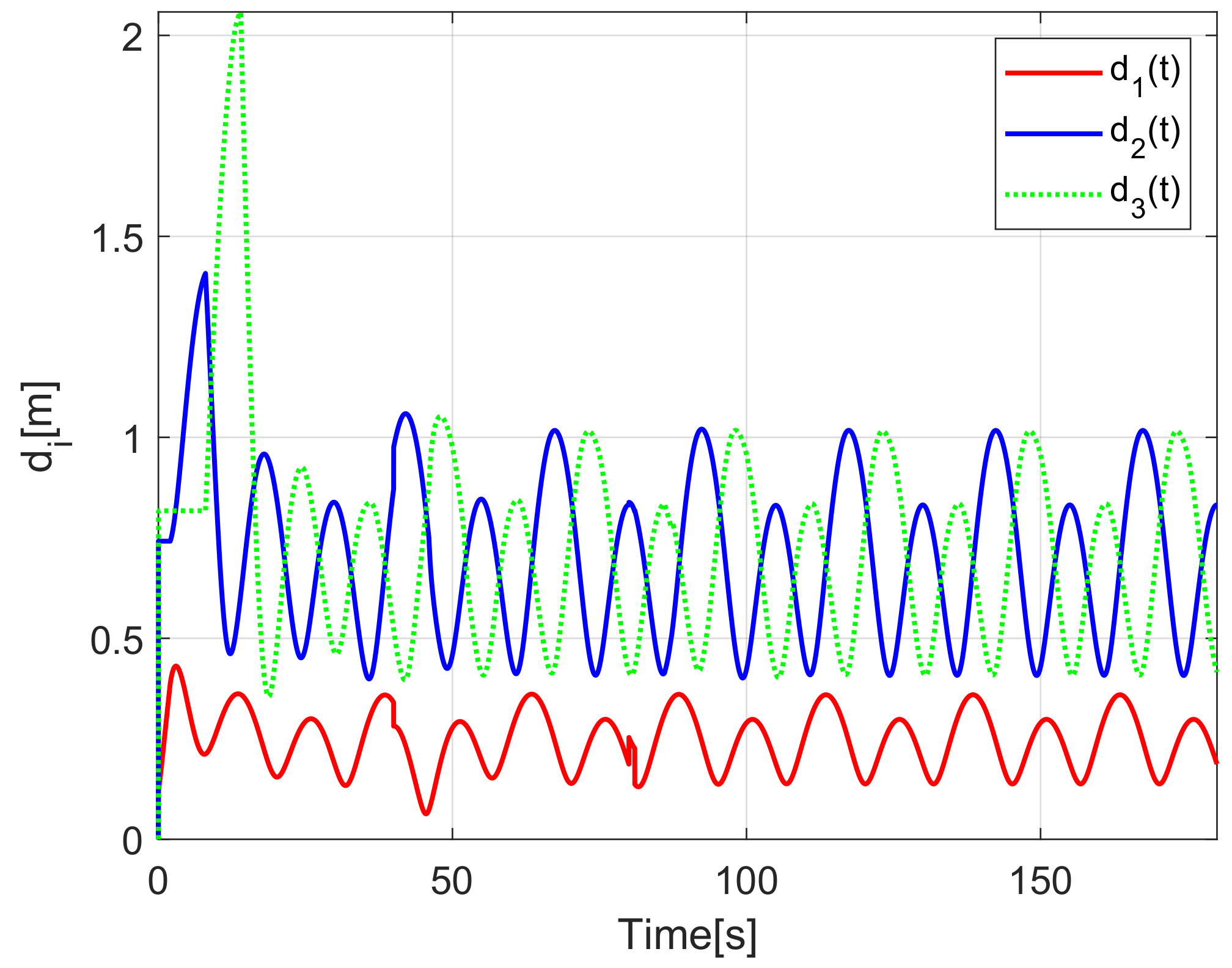

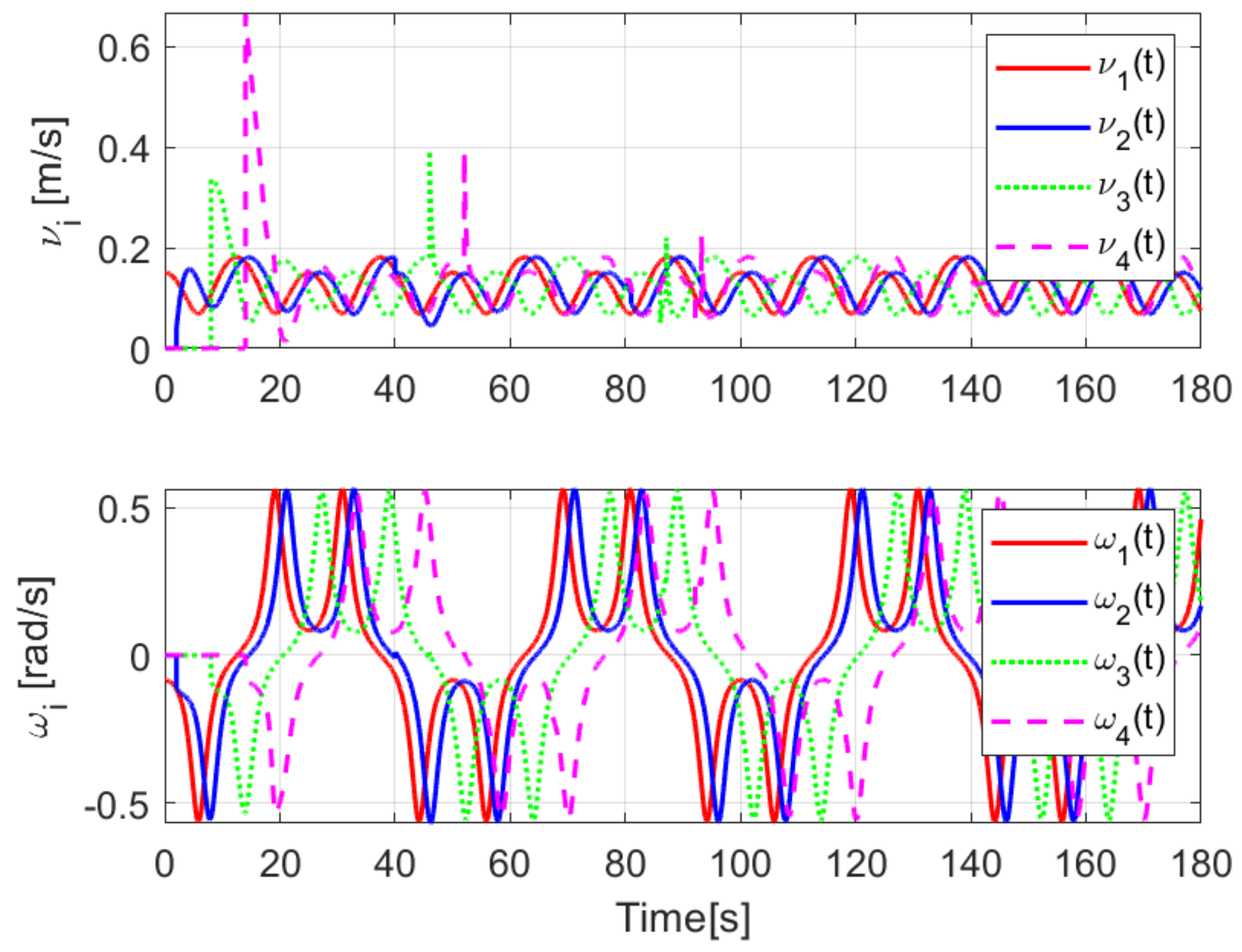

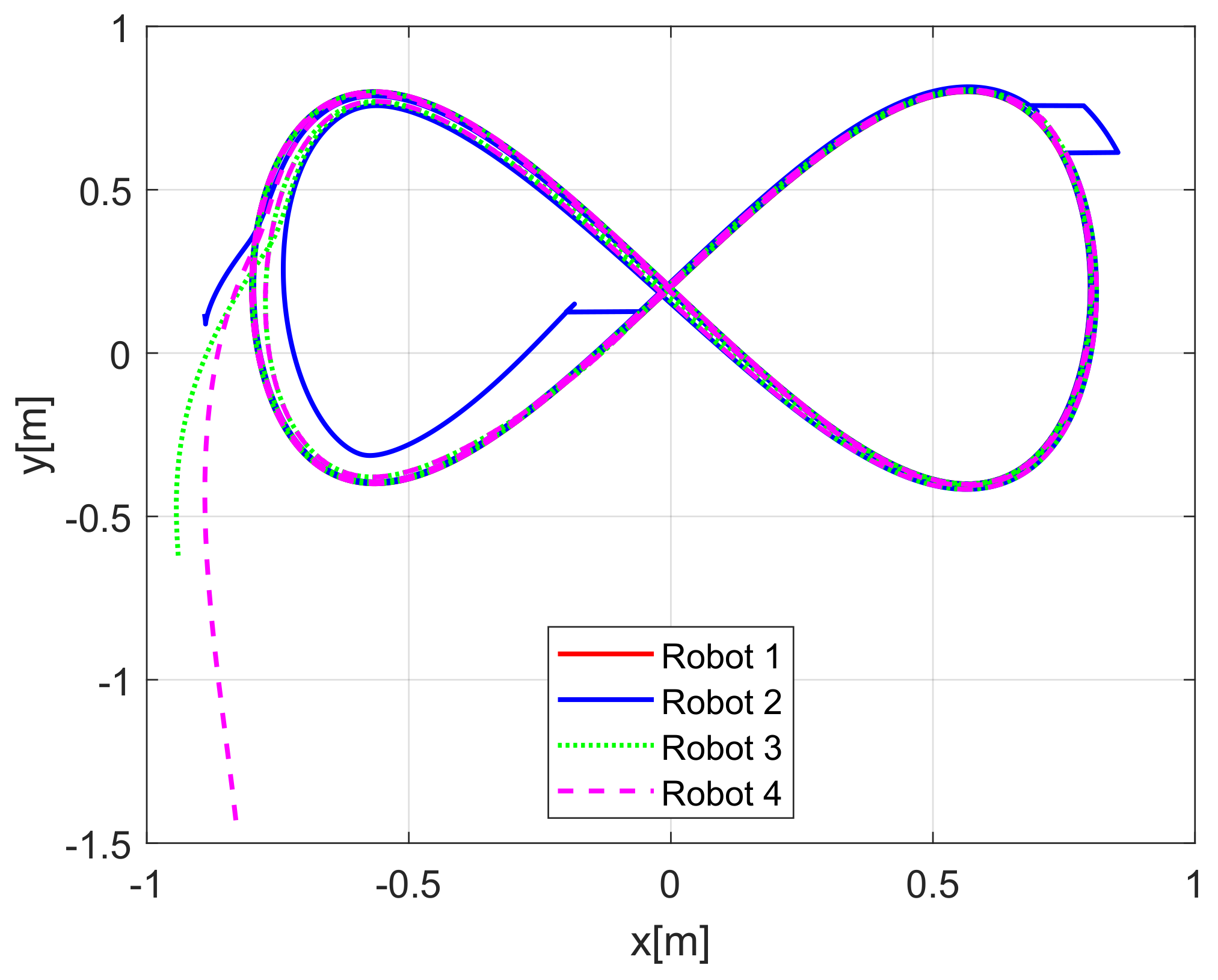

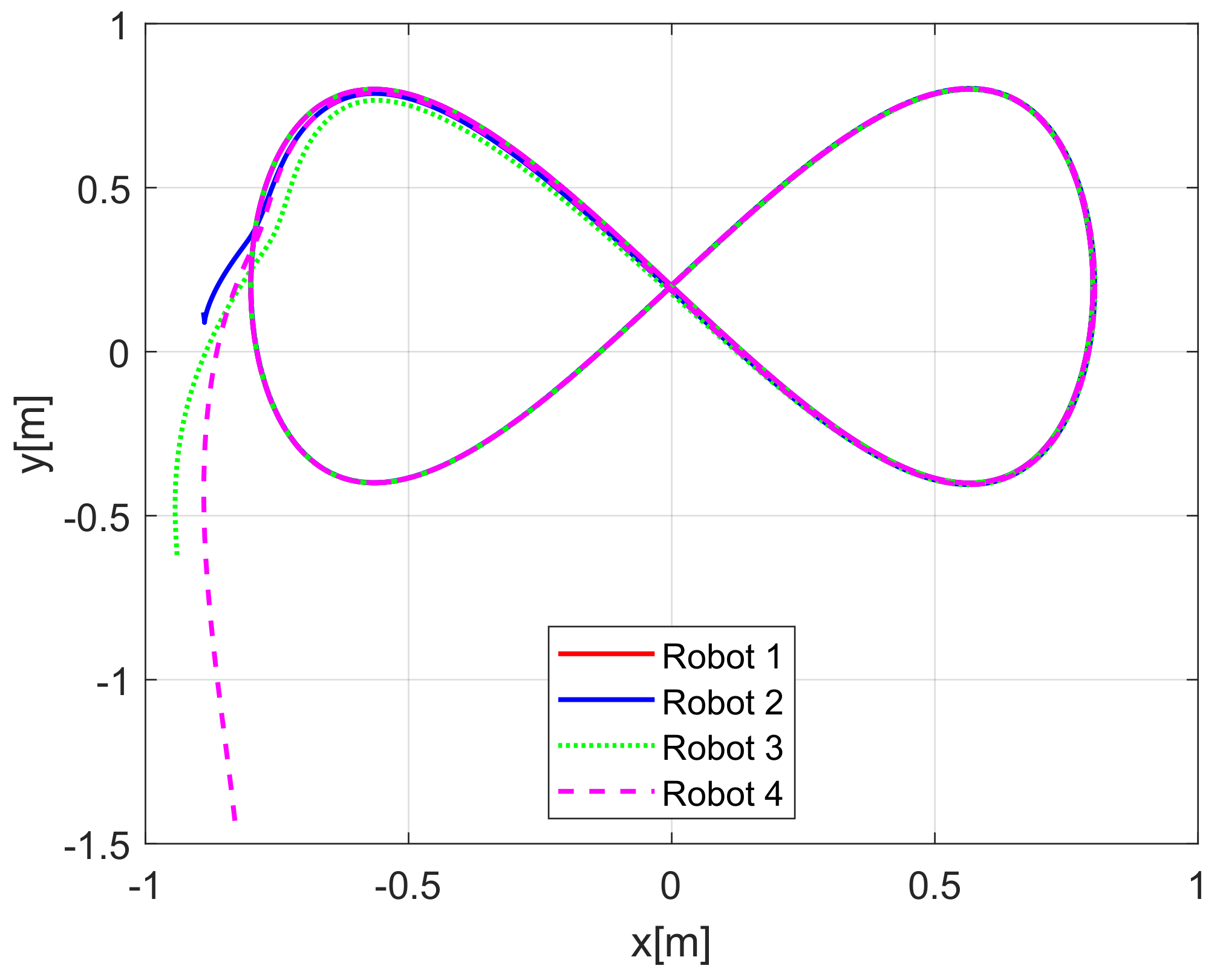

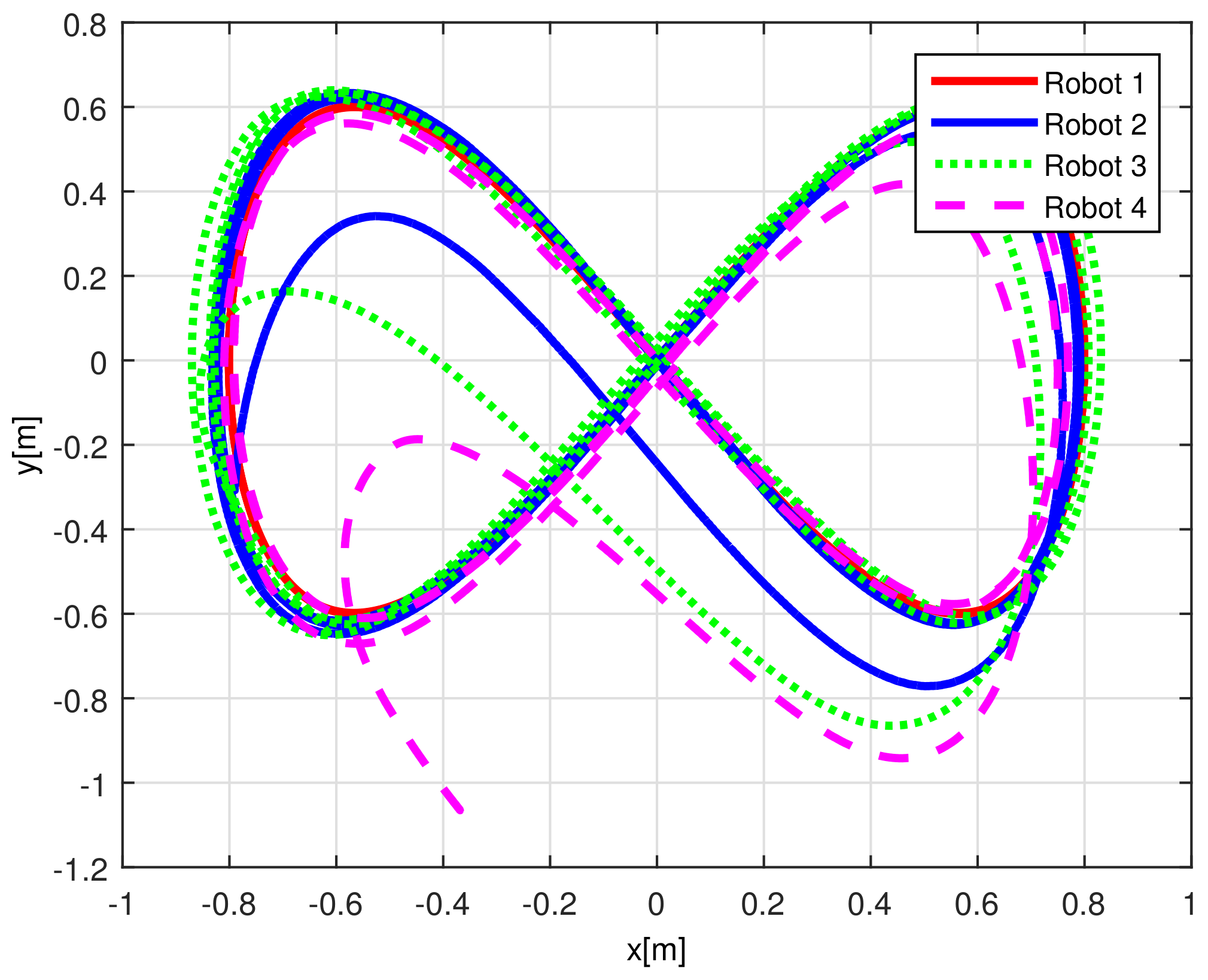

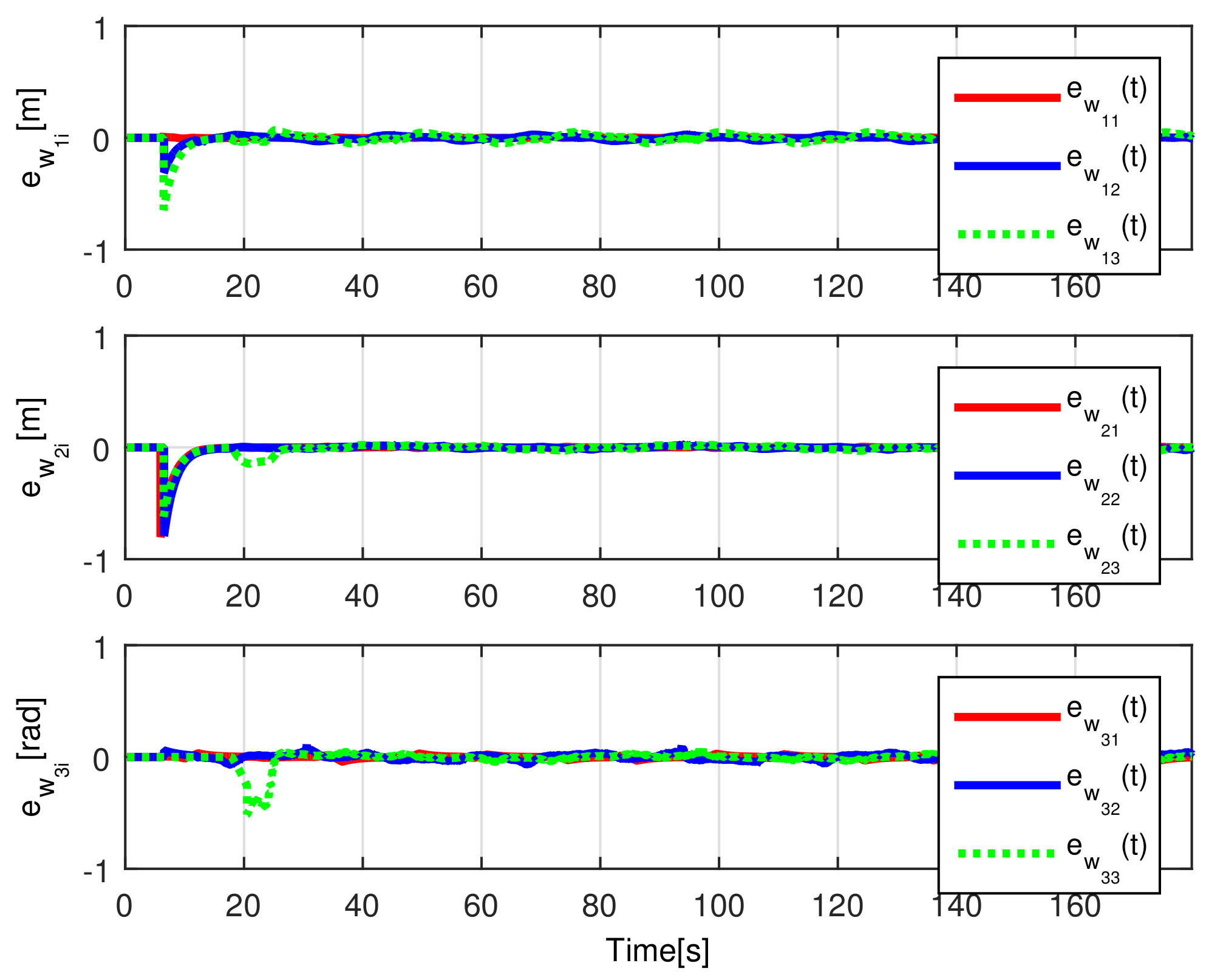

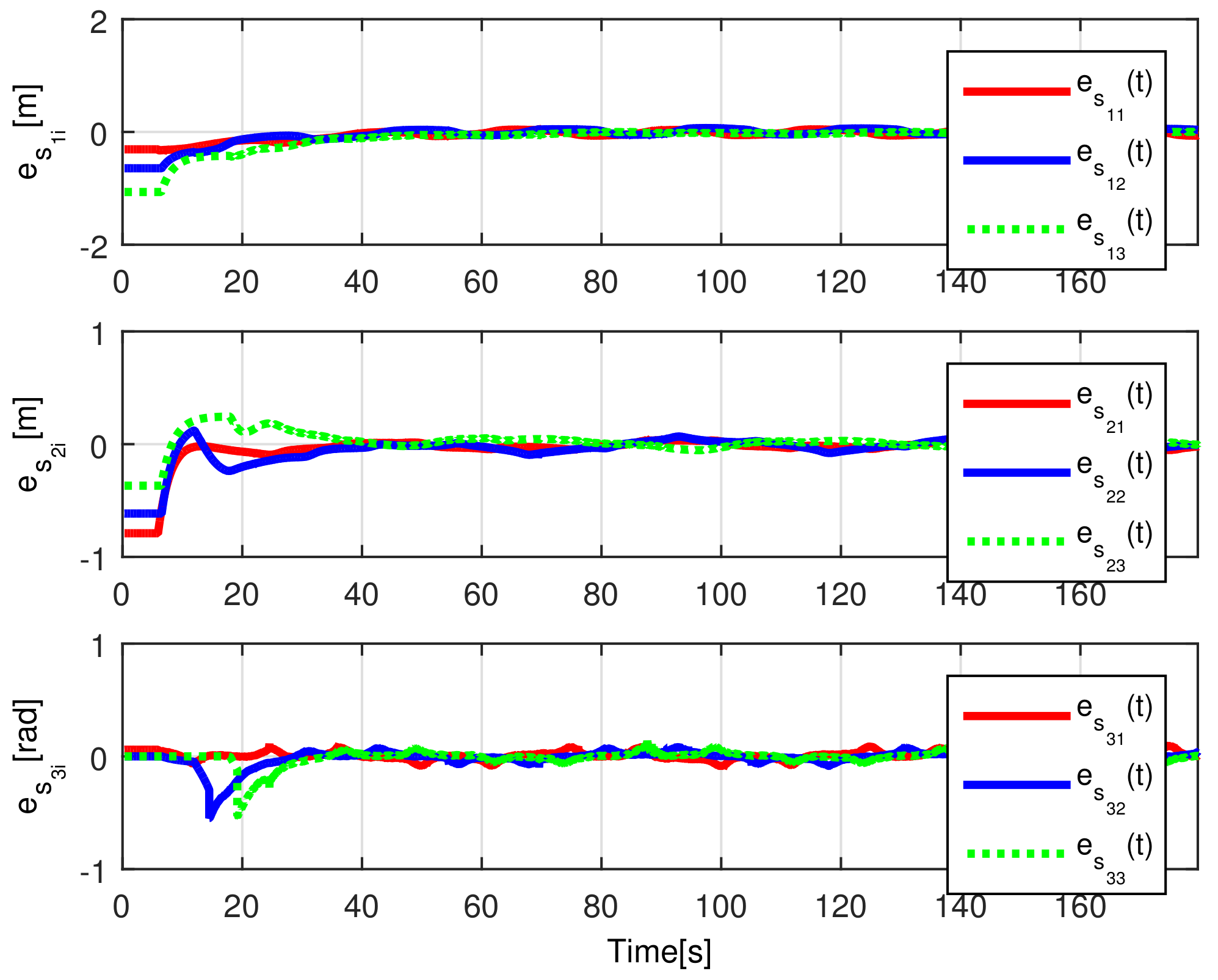

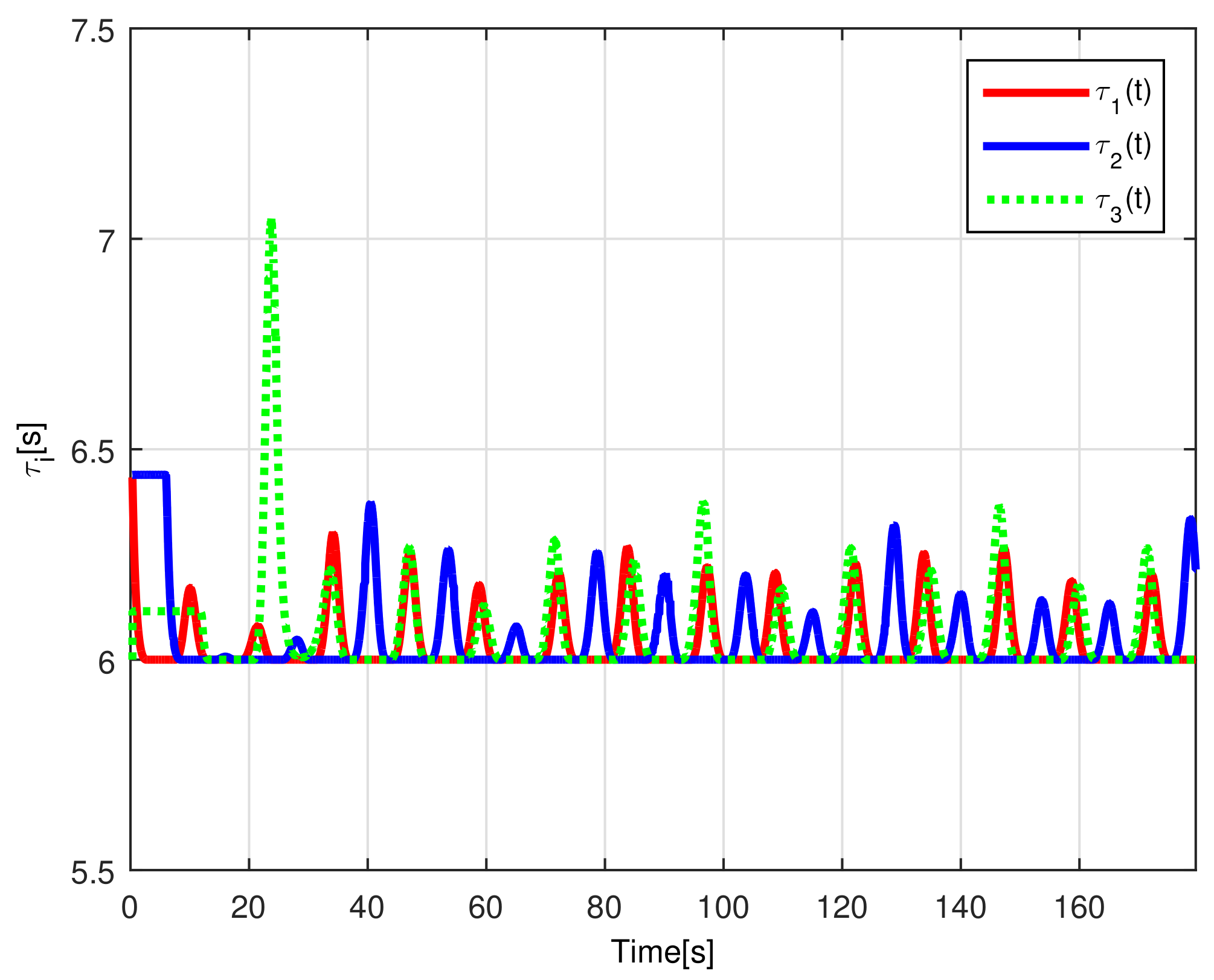

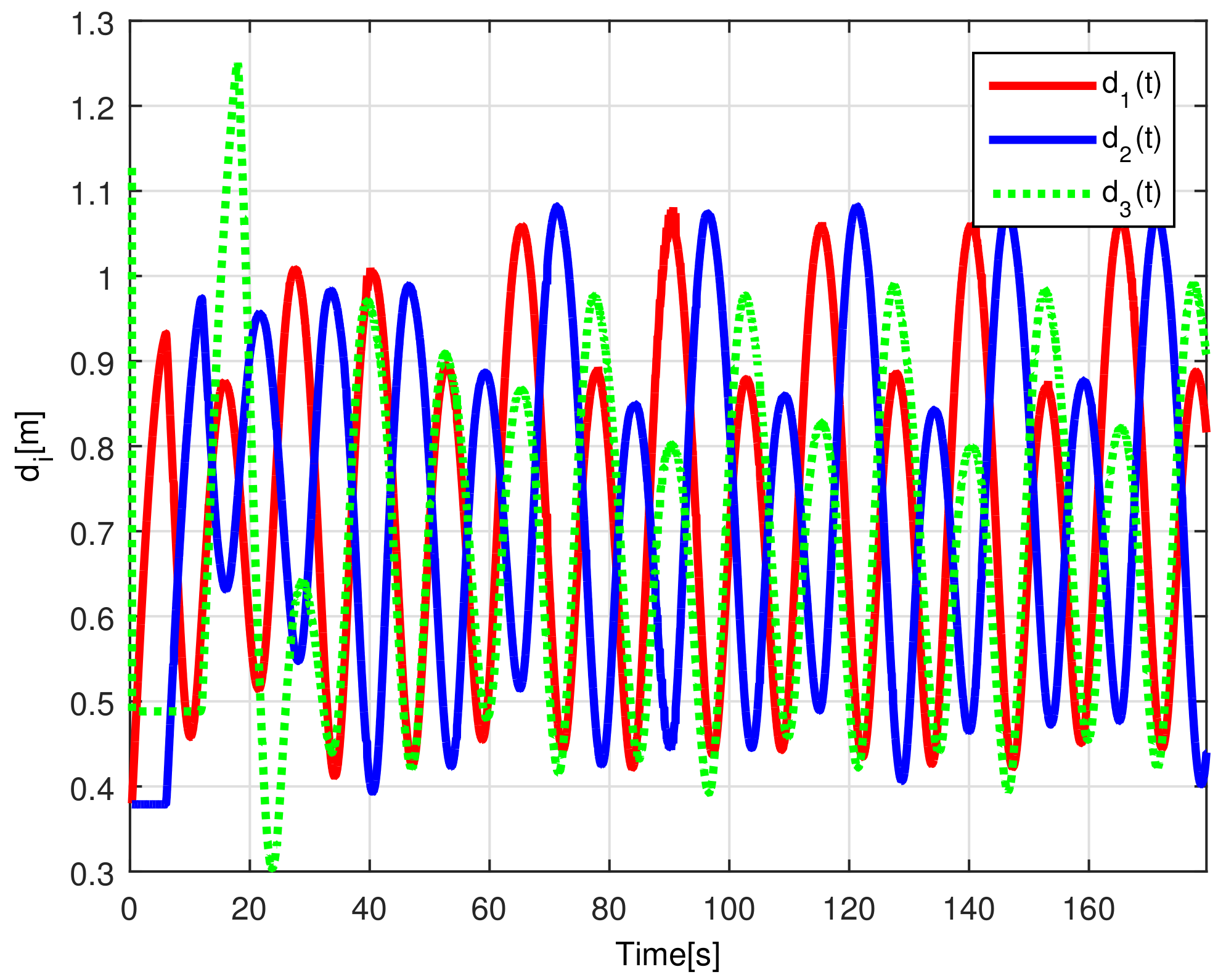

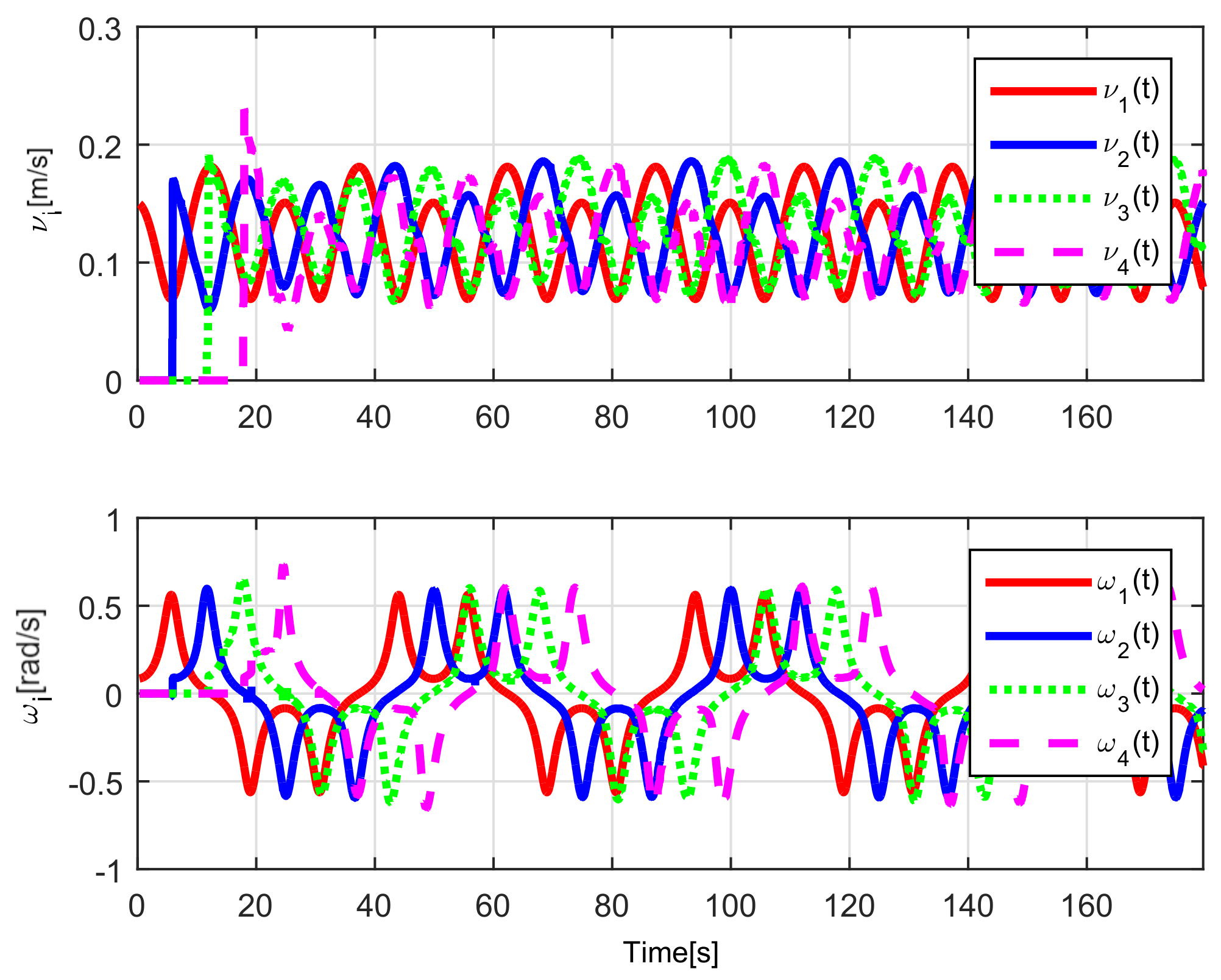

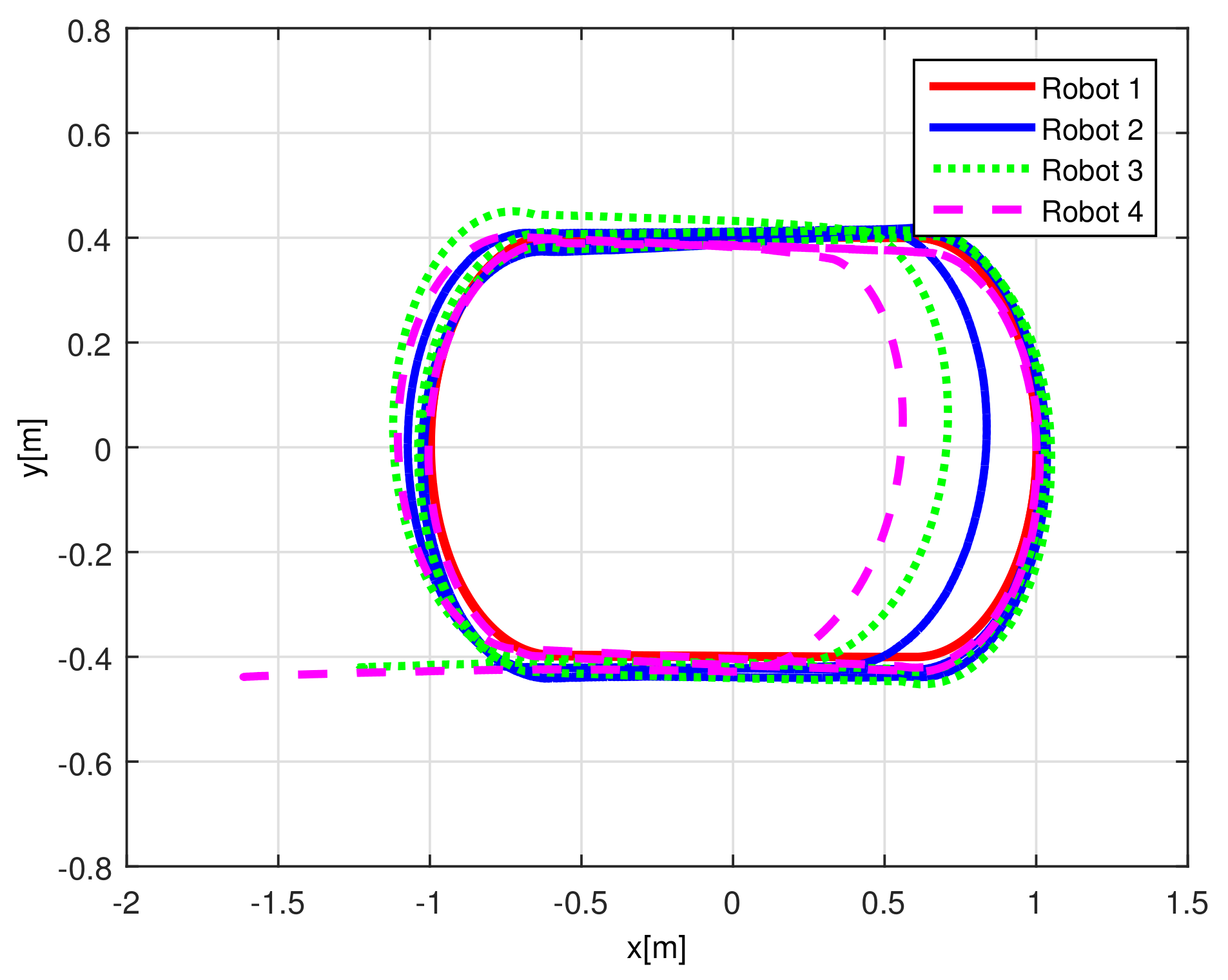

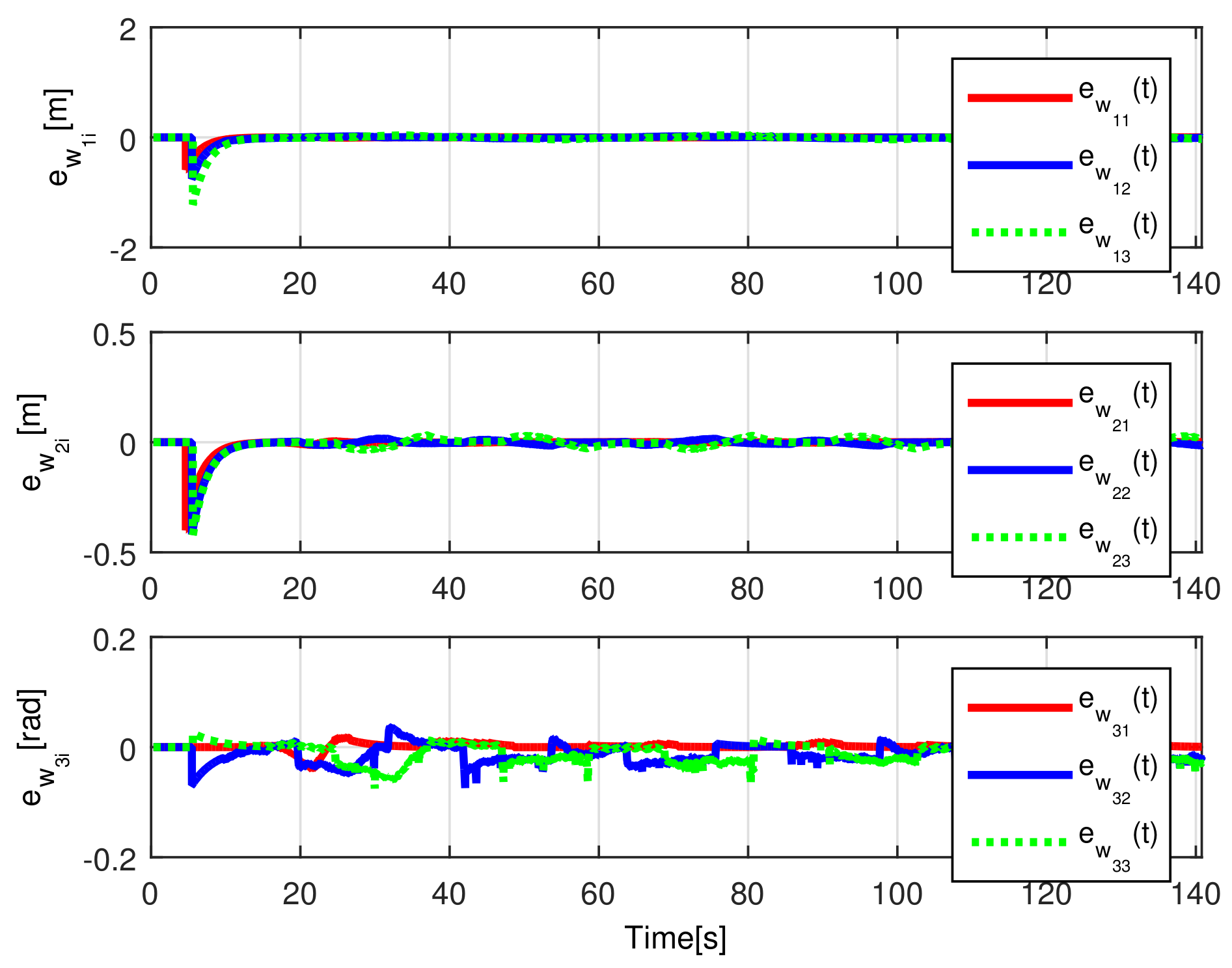

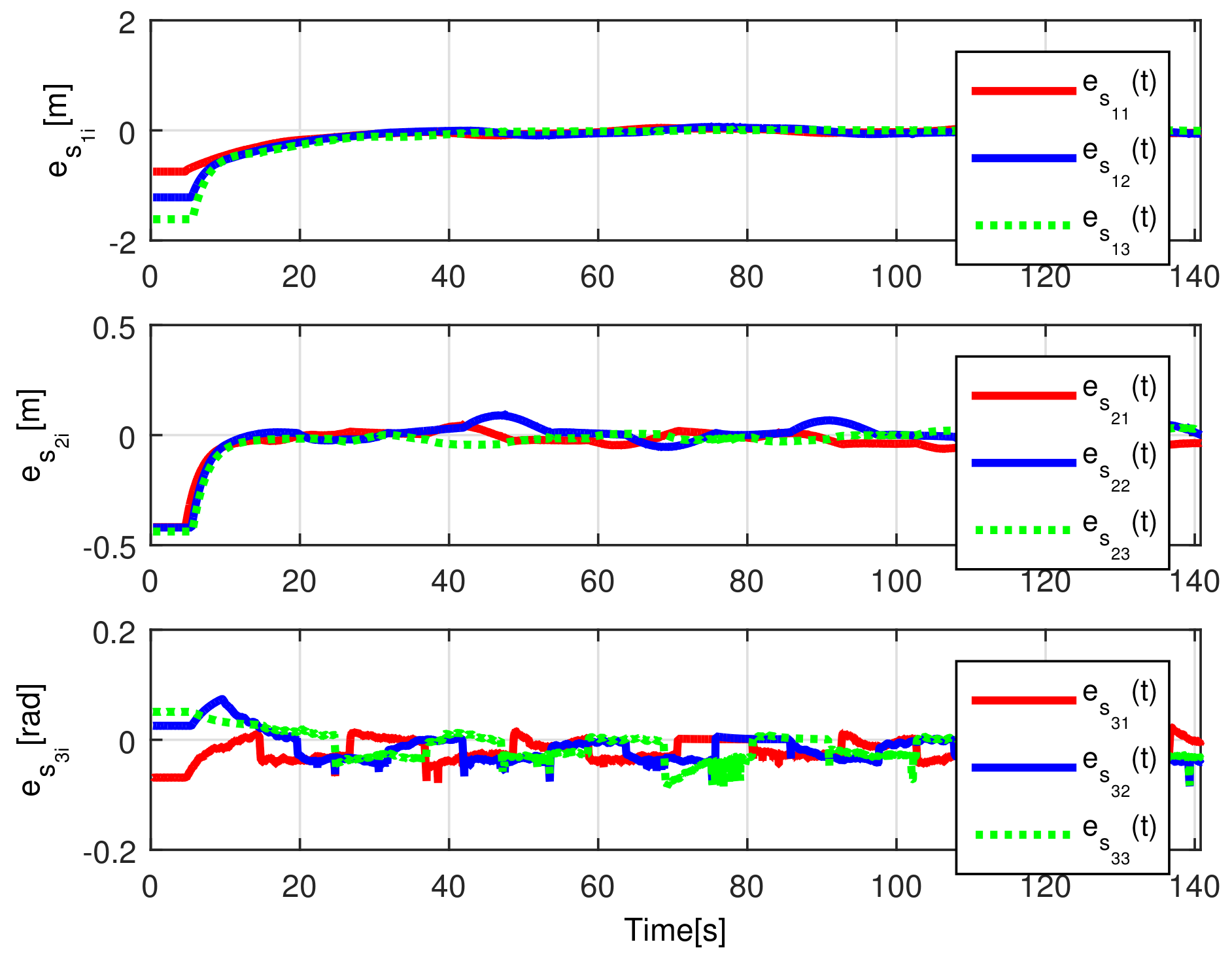

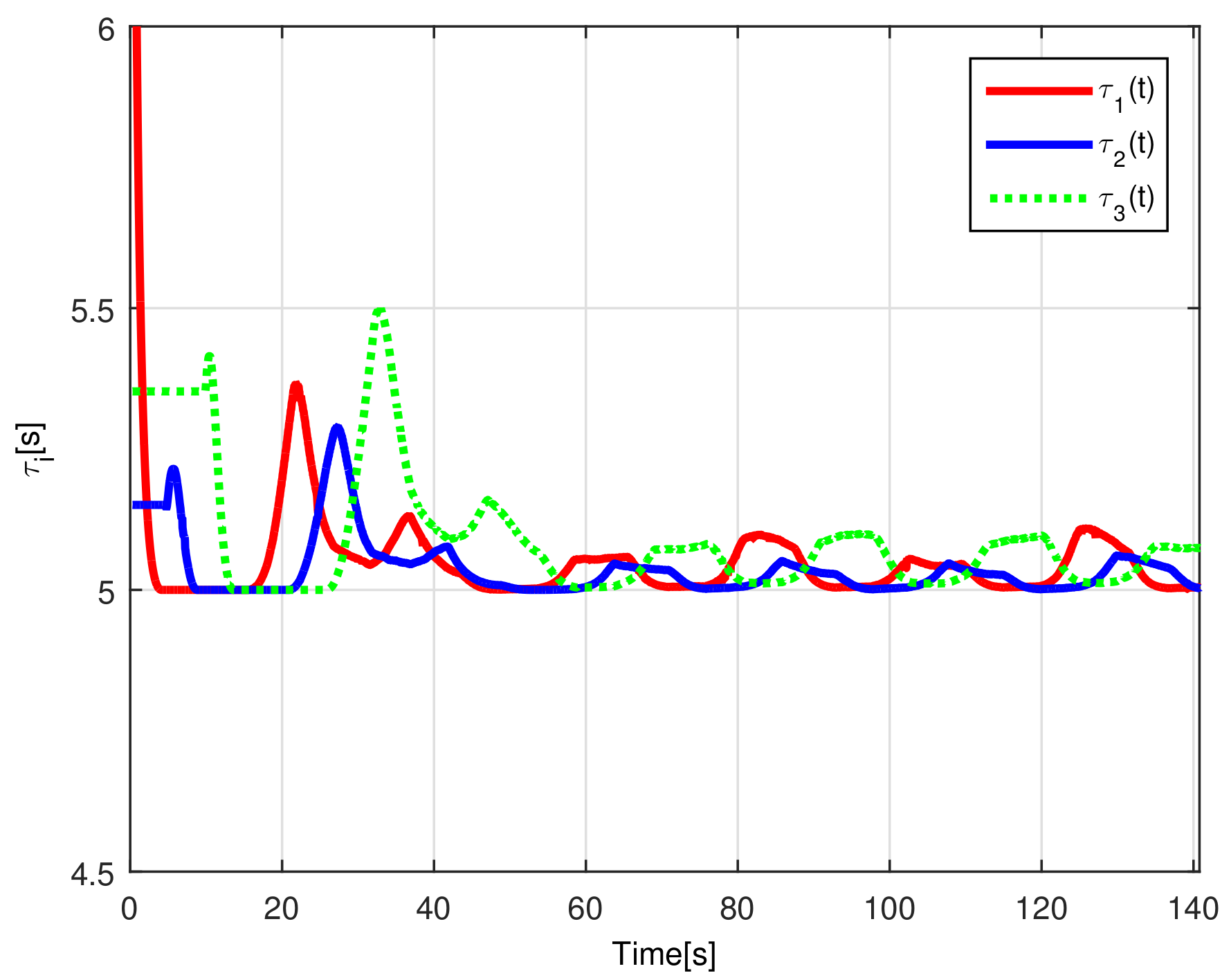

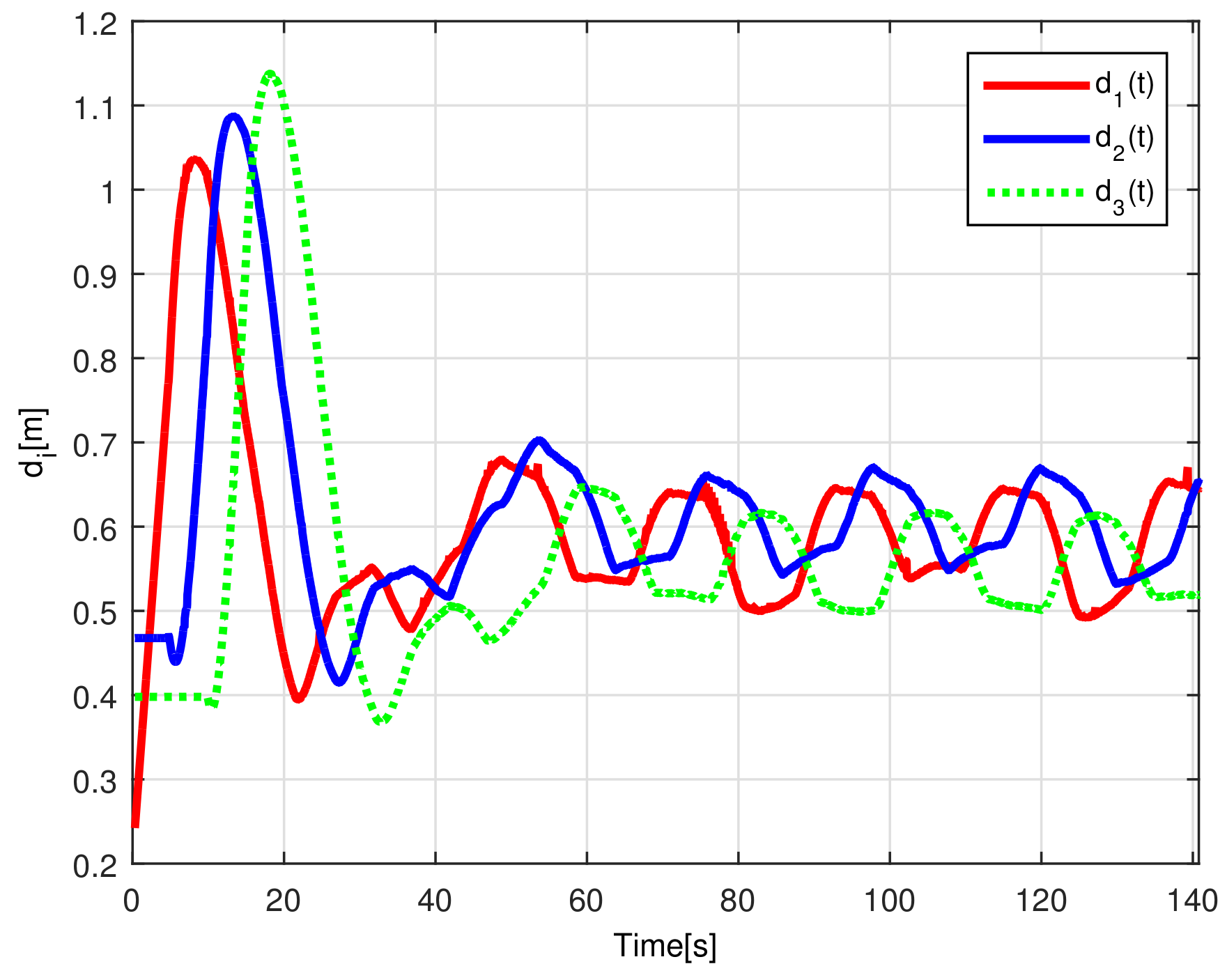

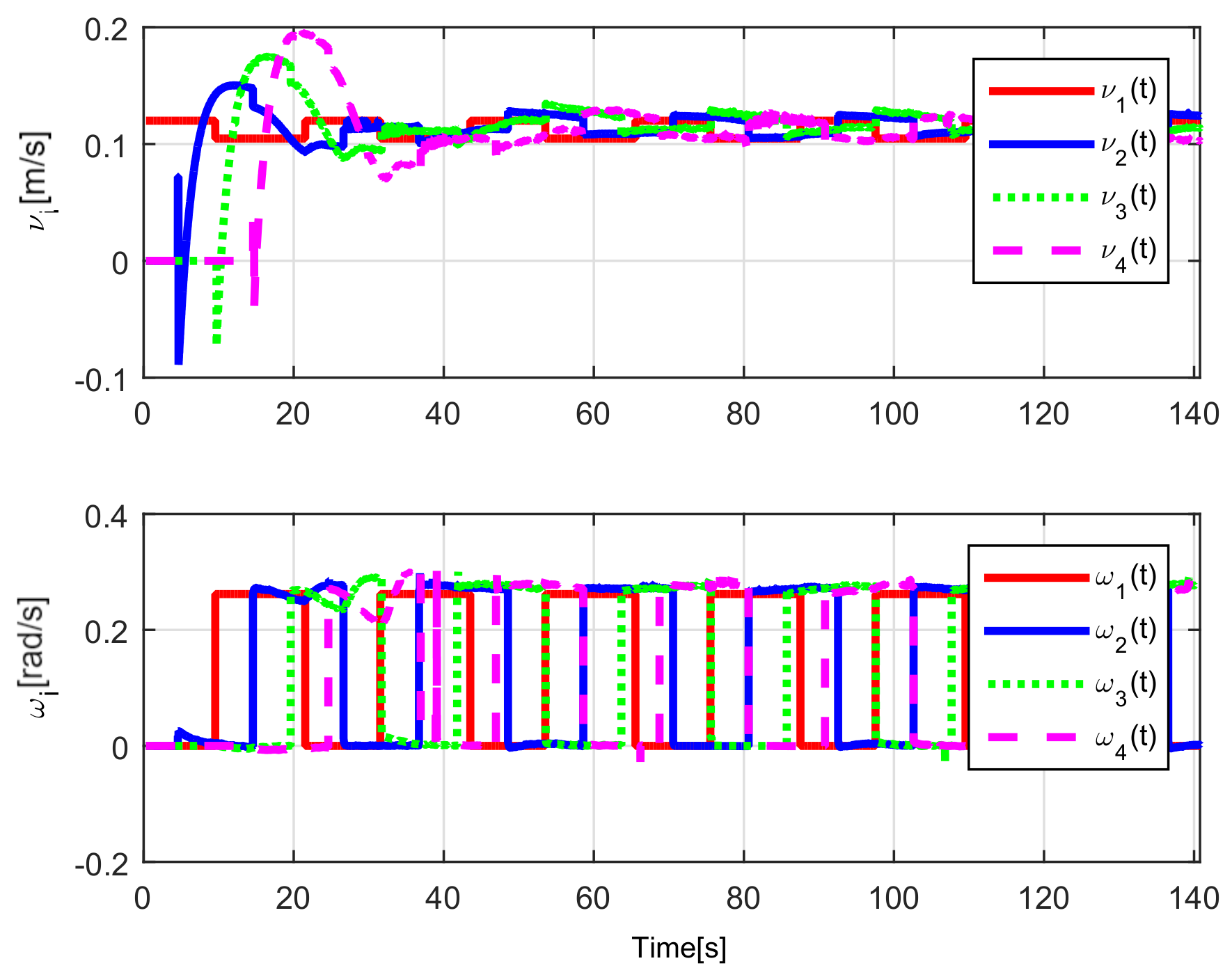

When comparing the simulated (NE) results, Section 5.1, and real-time experiments for the Lemniscate path (RTE-a), Section 5.3.1, we note that convergence of the observation errors is rather faster than the tracking errors, as established from the stability analysis, since the observations errors present exponential convergence, Lemma 1, while the tracking errors converge asymptotically, Lemma 2. In contrast, it can be seen that the time-varying gap and the associated relative distance ensures no collision between the mobile robots, preserving a minimum safe distance. Finally, as to show robustness, when sudden perturbations at positions and orientation are introduced, simulating lost or failure of sensors measurements, or communication channel problems, it can be seen that the observers filtered the peak changes on measurements values, and smoothness of the signals is propagated through the mobile robots chain.

Note that by Assumptions 2, 3, and Remark 6, some properties are required for the translation and rotation leader velocities, these constraints are used to prove stability and convergence properties of the observation and tracking errors. However, in real practice scenarios, rotational velocity can be zero, as when moving in a straight line; however, connecting a straight path with a curved one implies discontinuities at the rotational velocity. Thus, in order to show that, even in these scenarios, the proposed controller behaves appropriately and convergence properties are kept, the oval path experiment of Section 5.3.2 was tested. Note that although the mobile robots presents discontinuities, see Figure 24, the stability and convergence properties of the observation and tracking errors is preserved, thus, it can be concluded that the observers help filtering such discontinuities and render smooth tracking trajectories for the platoon formation, and this filter behavior is propagated through the mobile robot chain.

Remark 8.

It is important to point out some drawbacks of the proposed time-varying gap formation strategy. First of all, it should be pointed out that the present chain strategy does not consider a specific obstacle avoidance strategy since at the transient response, when the tracking errors have not converged, there is a possibility of collision among the vehicles at the platoon; this risk is eliminated when the agents have converged to the desired trajectories due to the time-varying strategy. We also note that, even when the individual control of each robot allows the possibility to move backwards, the chain formation does not allow this situation since the leader trajectory has to be followed by all members of the formation. Backward movements could be possible in the case of a time-varying topology, allowing the last robot to become the new leader of the formation.

7. Conclusions

In this work, a control scheme for a platoon of mobile robots with a time-varying spacing policy, based on an input-varying-delay observer that estimates the delayed trajectory of the (i)-th robot, which should be considered as a desired path for the ()-th robot, was developed. The time-varying gap between each pair of successive robots is computed by means of a smooth function activated on an influence zone that depends on the distance between robots (i)-th and ()-th.

It is formally shown, based on a Lyapunov stability analysis, how the estimation and the tracking errors associated with the chain formation of the vehicles converge to the origin, preserving the formation of the vehicles along any trajectory described by the leader robot in the workspace, due to bounded input velocity signals. The proposed formation strategy shows that when the robots approach each other in a slowdown velocity scenario, the time-varying gap raises its magnitude to increase the distance between each pair of successive robots at the platoon, avoiding collisions among them, rendering an efficient collision-free formation strategy.

Real-time experiments are in line with the simulation results, supporting the convergence properties that were obtained by the stability analysis over the estimation and tracking errors. The robustness benefits of the considered observer are shown by numerical and experimental results on a Lemniscate-path type and an oval track race example, showing good performance of the proposed formation strategy, allowing us to conclude some robustness properties of the platooning strategy.

It should be highlighted that the present strategy considers the complete kinematic model of the vehicles and not only a reduction model in one dimension or a punctual mass robot, as is usual in the literature. It is also important to mention that all the robots in the formation converge to the same trajectory generated by the platoon leader robot, and the fact that the considered delay observer acts as a natural filter for possible external or measurement disturbances. Finally, it is important to mention that the real-time experiments were carried out in a controlled environment; in a future work, we should consider the same formation problem for an outdoor experiment by adding onboard cameras to the follower robots, which could provide the relative distance and angles between the robots. Further, an obstacle avoidance strategy should be considered in a general solution of this formation problem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.V.-V., A.R.-A.; Investigation, C.A.D.-O., R.D.C.-M., M.V.-V., A.R.-A.; Validation, C.A.D.-O., M.V.-V.; Writing-original draft, C.A.D.-O., R.D.C.-M., M.V.-V.; Literature Review, A.R.-A., R.D.C.-M.; Real time experiments, C.A.D.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Conacyt-Mexico under grant CB2017-2018-A1-S-26123.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Soni, A.; Hu, H. Formation control for a fleet of autonomous ground vehicles: A survey. Robotics 2018, 7, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caveney, D. Cooperative Vehicular Safety Applications. IEEE Control. Syst. 2010, 30, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klancar, G.; Matko, D.; Blazic, S. A control strategy for platoons of differential drive wheeled mobile robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2011, 59, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.E.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, L.Y.; Zhang, H. Platoon control of connected vehicles from a networked control perspective: Literature review, component modeling, and controller synthesis. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besselink, B.; Johansson, K.H. String Stability and a Delay-Based Spacing Policy for Vehicle Platoons Subject to Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2017, 62, 4376–4391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaroop, D.; Hedrick, J.K.; Chien, C.C.; Ioannou, P. A Comparision of Spacing and Headway Control Laws for Automatically Controlled Vehicles1. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 1994, 23, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, K.; Hu, M. Spacing Policies for Adaptive Cruise Control: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 50149–50162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latrech, C.; Chaibet, A.; Boukhnifer, M.; Glaser, S. Integrated Longitudinal and Lateral Networked Control System Design for Vehicle Platooning. Sensors 2018, 18, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samadi Gharajeh, M.; Jond, H.B. Speed Control for Leader-Follower Robot Formation Using Fuzzy System and Supervised Machine Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Gong, J.; Lv, C.; Chen, X.; Cao, D.; Chen, Y. A Personalized Behavior Learning System for Human-Like Longitudinal Speed Control of Autonomous Vehicles. Sensors 2019, 19, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.G.; Wang, J.L.; Liao, F.; Teo, R.S.H. String stability of heterogeneous leader-following vehicle platoons based on constant spacing policy. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Gothenburg, Sweden, 19–22 June 2016; pp. 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeg, J.; Semsar-Kazerooni, E.; Lijster, G.; van de Wouw, N.; Nijmeijer, H. Graceful Degradation of Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 16, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, P.; Pant, A.; Hedrick, K. Disturbance propagation in vehicle strings. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besseghieur, K.L.; Trebinski, R.; Kaczmarek, W.; Panasiuk, J. From Trajectory Tracking Control to Leader–Follower Formation Control. Cybern. Syst. 2020, 51, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwek, M.; Baranowski, L.; Panasiuk, J.; Kaczmarek, W. Modeling and simulation of movement of dispersed group of mobile robots using Simscape multibody software. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2078, p. 020045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; He, S.; Lin, H.; Wang, C. Platoon Formation Control With Prescribed Performance Guarantees for USVs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 4237–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, C.; Shang, W.; Feng, G. A Synchronization Approach to Trajectory Tracking of Multiple Mobile Robots While Maintaining Time-Varying Formations. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2009, 25, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, S.E.; Li, K.; Wang, L.Y. Stability Margin Improvement of Vehicular Platoon Considering Undirected Topology and Asymmetric Control. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2016, 24, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verginis, C.K.; Bechlioulis, C.P.; Dimarogonas, D.V.; Kyriakopoulos, K.J. Robust Distributed Control Protocols for Large Vehicular Platoons with Prescribed Transient and Steady-State Performance. IEEE Trans. Control. Syst. Technol. 2018, 26, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bernardo, M.; Salvi, A.; Santini, S. Distributed Consensus Strategy for Platooning of Vehicles in the Presence of Time-Varying Heterogeneous Communication Delays. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 16, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödönyi, G.; Szabó, Z. Adaptation of spacing policy of autonomous vehicles based on an unknown input and state observer for a virtual predecessor vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 1715–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naus, G.; Vugts, R.; Ploeg, J.; van de Molengraft, R.; Steinbuch, M. Cooperative adaptive cruise control, design and experiments. In Proceedings of the 2010 American Control Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 30 June–2 July 2010; pp. 6145–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Morales, R.D.; Velasco-Villa, M.; Rodríguez-Angeles, A.; Muro-Cuellar, B. Leader-follower formation based on time-gap separation. AMRob J. Robot. Theory Appl. 2016, 4, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Morales, R.D.; Velasco-Villa, M.; Rodriguez-Angeles, A. Chain formation control for a platoon of robots using time-gap separation. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canudas, C.; Siciliano, B.; Bastin, G. Theory of Robot Control; Springer: Saint-Martin, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Khatib, O. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, St. Louis, MO, USA, 25–28 March 1985; Volume 2, pp. 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, C. Velocity and torque feedback control of a nonholonomic cart. In Advanced Robot Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, H.K. Nonlinear Systems, 3rd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).