Abstract

Cyanobacteria of the genus Tychonema are common inhabitants of freshwater bodies in a temperate zones. In Lake Baikal, Tychonema sp. was first reported in 2014. It grows excessively on the bottom on almost all substrates types, forming epiphytic and epizoic biofilms, and its role in the mass mortality events affecting of endemic Baikal sponges is discussed. The cyanobacterial strain BBK16 (=IPPAS B-2063T), isolated from a biofilm on a log pier in the Bolshiye Koty settlement in 2016, was used for further taxonomic characterization. Key morphological features of strain BBK16 include its growth as a creeping mat, highly motile trichomes that are sometimes narrowed and hooked at the ends, and the presence of rounded-conical apical cells with a calyptra. Strain ultrastructure (fascicular parietal thylakoids and type D cell division) differs from Tychonema species with radial thylakoids but aligns with other genera in the Microcoleaceae family. A comprehensive analysis, including 16S rRNA gene phylogeny, conserved protein phylogeny, and whole-genome comparisons, confirmed its placement within the genus Tychonema. The average nucleotide identity, average amino acid identity and digital DNA–DNA hybridization values between strain BBK16 and T. bourrellyi FEM GT703 were 90.7%, 91.1% and 43.3%, respectively, indicating values below the standard thresholds for species delineation. Based on combined morphological, genomic, and ecological evidence, we propose the name Tychonema litorale sp. nov. for strain BBK16, a novel species described in accordance with the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants.

1. Introduction

The genus Tychonema was separated from Oscillatoria by Anagnostidis and Komárek in 1988 based on a specific morphological feature: net-like structures in cells with a loose arrangement of thylakoids (known as keritomy) [1]. Currently, the genus includes only seven species [2]. Species of Tychonema exhibit planktic, tychoplanktic, or benthic lifestyles and are primarily known from North European oligotrophic, mesotrophic, or slightly eutrophic water bodies. These are mainly cold-stenothermic species distributed across the colder parts of the temperate zone [3,4]. Although typically associated with temperate and arctic environments, Tychonema has also been found in subtropical regions of Australia, China, and India [5,6,7], as well as in the subequatorial zones of Iran and Brazil [8,9]. In Russia, previous records are largely limited to water bodies within the Arctic Circle (http://kpabg.ru/cyanopro/, accessed on 1 December 2025) [10].

Recent revisions of the Microcoleaceae, based on a large dataset of 16S rDNA and genomes, demonstrate a monophyletic relationship between Tychonema and Microcoleus, proposing the merging of these morphologically and genetically similar genera [11,12]. However, taxonomic revision of Tychonema is hampered by the absence of an epitype strain, leading to uncertainty regarding the genus’s phylogenetic position. T. tenue, originally described as Oscillatoria bornetii f. tenuis by the Latvian botanist Heinrich Leonhards Skuja [13], was designated the lectotype species upon the segregation of Tychonema from the genus Oscillatoria [1]. A type strain, CCAP 1459/11B, was defined for T. bourrellyi during a revision of planktonic bloom-forming oscillatorioid cyanobacteria [14]. To date, no type strain has been defined for the tychoplanktic T. tenue, despite the availability of its 16S rRNA sequence (strain SAG 4.82) in the GenBank database. Formal typification of T. tenue is therefore critically important for resolving the taxonomic ambiguity surrounding the genus Tychonema.

More recently, reports concerning harmful blooms of Tychonema have increased. For instance, T. bourrellyi was recorded as abundant in Italian lake plankton, while Tychonema sp. proliferated in the benthos of water bodies across Germany and Canada [15,16,17]. Strains isolated from these blooms have been shown to produce anatoxin-a and homoanatoxin-a, leading to documented cases of dog poisoning and death [15,16,17,18,19]. Furthermore, extensive fouling of T. bornetii on macrophytes in Lake Sanabria, Spain, degraded benthic communities and was equated to an ecological disaster [20]. In China, isolates of T. bourrellyi from a Lake Erhai bloom produced volatile geosmin and β-ionone which imparted off-odours to the water; this led to the classification of the species as harmful and required monitoring [6]. Additionally, benthic Microcoleus species from rivers and streams in New Zealand, Canada, and the USA are known as producers of anatoxin-a [21,22,23].

Another critical environmental issue of the 21st century is the mass mortality of sponges and corals in marine ecosystems [24,25]. Diseased sponges and corals lose their endosymbionts, leading to bleaching, and are often overgrown by various filamentous cyanobacteria. Experimental studies of sponge diseases have revealed this cyanobacterial growth to be a secondary phenomenon. The cyanobacteria were unable to infect healthy sponges, colonizing only already affected, dying organisms [26,27,28]. The role of the cyanobacterial mat in coral black band disease (BBD) is more direct. This mat, which produces toxic compounds such as sulfides and microcystins, migrates across the coral colony as a distinct dark red band, resulting in coral death [29].

Researchers have speculated on the sources of these catastrophic events. For instance, publications on the Great Barrier Reef were long dominated by the idea of global climate warming. However, P.R.F. Bell et al. [25] argued that the origin of the mass coral mortality was a latent, persistent eutrophication of these oligotrophic ecosystems. Eutrophication causes coral depletion, making reefs more sensitive to pathogens. Furthermore, it directly stimulates cyanobacterial proliferation. Such phenomena have not been widely reported in freshwater bodies, presumably because sponges are far more diverse in marine environments.

Lake Baikal is a notable exception. It is one of the most ancient (~25 Ma) and deepest freshwater lakes on Earth, exhibiting a unique sponge fauna represented by 15 endemic and 5 cosmopolitan species [30,31]. The most familiar are representatives of the endemic family Lubomirskiidae. Until the 2010s, they were regarded as the most abundant benthic invertebrates and shaped the communities of the stony littoral zone. Since 2010, however, mass disease and mortality of these unique endemic sponges have been reported across all three basins of Lake Baikal. Concurrently, first records of littoral eutrophication appeared, alongside changes in the zonality of the benthic algal flora, displacement of endemic Chlorophyta species by charophytes like Spirogyra, and other negative events. This combination of factors has been defined as an “ecological crisis.” As in marine systems, the bodies of diseased Baikal sponges are often covered by bright purple biofilms of filamentous Phormidium-like cyanobacteria [32]. In 2014, this cyanobacterium was identified as Tychonema sp. using microscopy and 16S rRNA metabarcoding [33,34].

In situ observations in Lake Baikal revealed Tychonema sp. fouling not only on diseased sponges, but also on decaying macrophyte thalli and plant detrital mats, suggesting a saprophytic ecology for this species [35]. It has been hypothesized that Tychonema’s high tropism for sponges is due to its mixotrophic ability—combining autotrophic and heterotrophic nutrition. This would allow it to consume organic substances and nutrients released during sponge decomposition [36]. A strain of Tychonema sp., BBK16, was isolated from benthic fouling. Its genome was found to contain a number of mixotrophy-related genes, confirming this physiological assumption [37]. In a subsequent co-culture experiment with sponge primmorphs, strain BBK16 colonized and completely destroyed the primmorphs it invaded [38]. Genomic examination of BBK16 left no doubt that the strain represented a new species [37]. Following the polyphasic approach to cyanobacterial taxonomy [39], we have complemented the previously obtained data on this strain. Based on a comprehensive analysis of cell morphology, ultrastructure, 16S and ITS sequences, and whole-genome data, we describe here a new species of the family Microcoleaceae: Tychonema litorale sp. nov.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling, Cultivation and Morphology

Samples were collected by scientific divers at depths of 1–20 m along the entire coast of Lake Baikal between 2014 and 2023, encompassing all seasons. Prior to sampling, the biofouling was photographed in situ using either a Sony A7 camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) or a GoPro HERO 7 video camera (GoPro Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA). Subsequently, on board the research vessel, subsamples intended for microscopic examination were preserved with 4% formaldehyde (final concentration). For cultivation, pieces of biofilm were placed in containers filled with Baikal water and maintained at +8 °C until delivery to the laboratory.

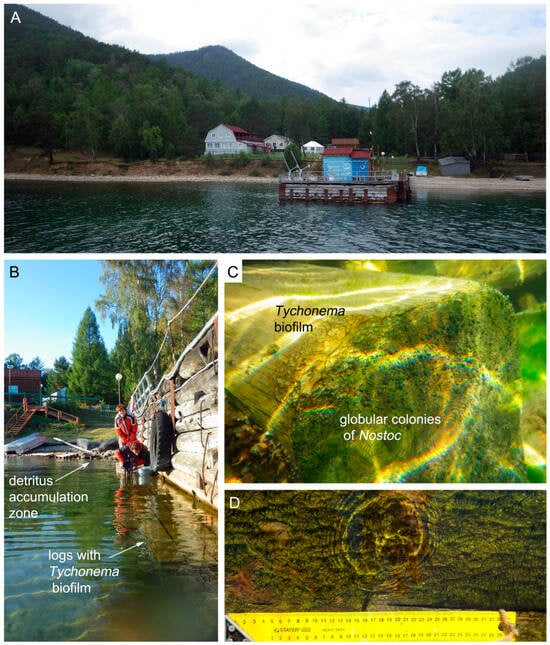

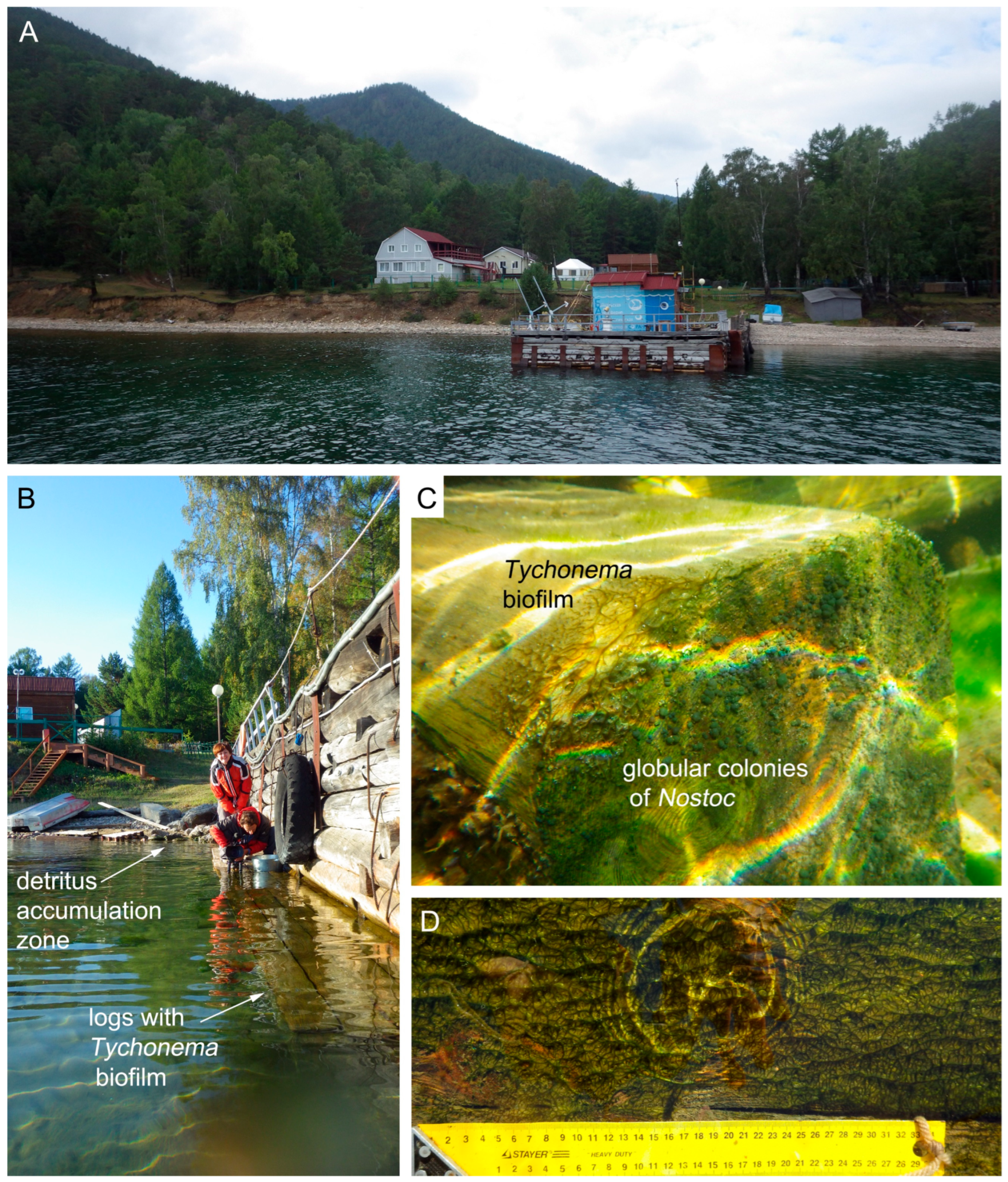

The strain was isolated from a giant biofilm (ca. 0.75 m2) developed on the underwater part of the wooden pier in Bolshiye Koty settlement in September 2015 (51°53′57.5″ N, 105°03′52.2″ E) (Figure A1). The isolation procedure and growth conditions for the resulting unialgal strain, designated BBK16, have been described previously [37]. Strain BBK16 is maintained in the culture collection of the Laboratory of Aquatic Microbiology, Limnological Institute, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk, Russia. Moreover, BBK16 was deposited in the collection of microalgae and cyanobacteria at the K.A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia (=IPPAS B-2063T).

A herbarium specimen of strain BBK16 was prepared by drying a subsample on a 0.2 µm membrane filter (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The filter containing the cyanobacterial biofilm was deposited in the IRKU Herbarium at Irkutsk State University (Irkutsk, Russia) under accession number IRKU 092122.

The morphological variability of the population was assessed using both cultured samples and field material preserved in 4% formaldehyde. Observations were made using a fluorescence microscope (Axio Imager, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). For the natural biofilm and the cultured strain, key taxonomic characteristics—including trichome width and cell length—were measured from 200 cells using Image-Pro Plus v6.0 software. Taxonomic identification of the strain was conducted following the system of Komárek and Anagnostidis [3]. A macroscopic image of the biofilm was obtained using a Coolpix S6800 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Natural samples collected from various substrates and locations across the lake were analyzed. The projective cover of Tychonema refers to the percentage of the bottom surface covered by cyanobacteria. This was measured in situ using digital imaging of photo-quadrats along transect lines. Calibration and area measurements were performed using Image-Pro Plus v6.0 software.

Sample preparation for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) followed the protocol of [40]. Ultrathin sections were examined using a LEO 906E transmission electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.2. DNA Extraction and Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from the culture by enzymatic lysis using lysozyme (1 mg mL−1; Roche, Basel, Switzerland), proteinase K (1 mg mL−1; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (1% w/v; VWR Life Science, Radnor, PA, USA), followed by phenol-chloroform extraction (Medigen LLC, Moscow, Russia) [41]. Library preparation was performed using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA)). Sequencing was carried out on an Illumina MiSeq platform, generating 300 bp paired-end reads.

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

De novo genome assembly was performed using SPAdes v3.15.3 [42], and assembly quality was assessed with CheckM2 v1.0.2 [43]. Average nucleotide identity (ANI) calculations and neighbor-joining (NJ) clustering were performed using ANIclustermap v1.4.0 [44] under default settings. Average amino acid identity (AAI) values were estimated with EzAAI v1.2.3 [45]. Digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) was calculated using the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator v3.0 [46].

For phylogenetic analysis, 16S rRNA gene sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.48 [47] with the L-INS-i algorithm and default parameters. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed from this alignment using IQ-TREE v2.2.5 [48] with the options --alrt 1000 -B 1000 to assess branch support; the best-fit nucleotide substitution model was also determined by IQ-TREE. A second phylogenetic tree was inferred from a concatenated alignment of conserved protein amino acid sequences using PhyloPhlAn v3.1.1 [49] with the parameters -d phylophlan-diversity medium -f supermatrix_aa.cfg. The same trees were additionally inferred by Bayesian inference using the MrBayes v3.2.6 [50] plugin in Geneious Prime v2024.0.2 (Biomaters Inc., Auckland, New Zealand) (16S rRNA: substitution model GTR, rate variation invgamma, 4 gamma categories, chain length 1,100,000, heated chains 4, heated chain temperature 0.2, subsampling frequency 200, burn-in length 100,000; concatenated proteins: GTR rate matrix, rate variation invgamma, chain length 110,000, heated chains 4, heated chain temperature 0.2, subsampling frequency 200, burn-in length 10,000; priors in both analyses: unconstrained branch lengths GammaDir(1, 0.1, 1, 1) and shape parameter Exponential(10). All phylogenetic trees were visualized using iTOL v6 [51].

For the ITS analysis, secondary structures of the 16S–23S internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region were predicted and visualized using Geneious Prime v2024.0.2. Folding prediction was performed using the RNAfold web server from the ViennaRNA Package (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/, accessed on 1 May 2025) under the Turner 2004 energy model at 25 °C [52,53].All reference genomic and nucleotide sequences were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database. Biosynthetic gene clusters within the studied genome were annotated using antiSMASH v7.0 [54]. The final genome assembly has been deposited in GenBank under accession number JAKJHX000000000.2.

2.4. Carotenoid Analysis

Pigment-rich extracts were obtained by classical extraction with acetone [55]. Sample analysis was performed using aluminum-backed 100 mm × 150 mm thin layer chromatography (TLC) silica gel CTX-1A-254 plates (Sorbfil, Krasnodar, Russia). Plates were developed in an ethyl acetate/acetone (5:4, v/v) solvent mixture. Pigments were detected directly by their natural coloration under visible light. Authentic standards of zeaxanthin, lutein, and β-carotene (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used for comparison.

For MALDI-TOF-MS detection, each colored spot was excised and extracted with methanol. Each methanolic extract was then mixed with a saturated solution of 2,5-dihydroxyacetophenone matrix in acetone. Mass spectra were acquired using an ultrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) operated in reflection mode. Measurements were taken in the positive ion mode over a mass range of 200–1000 Da using an AnchorChip target (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany).

3. Results

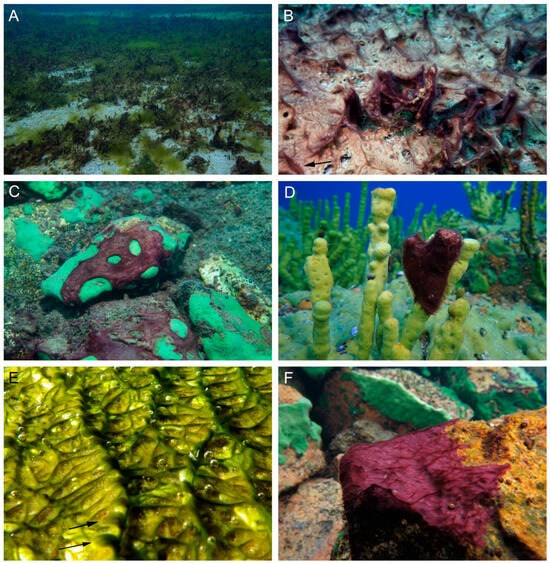

3.1. Distribution

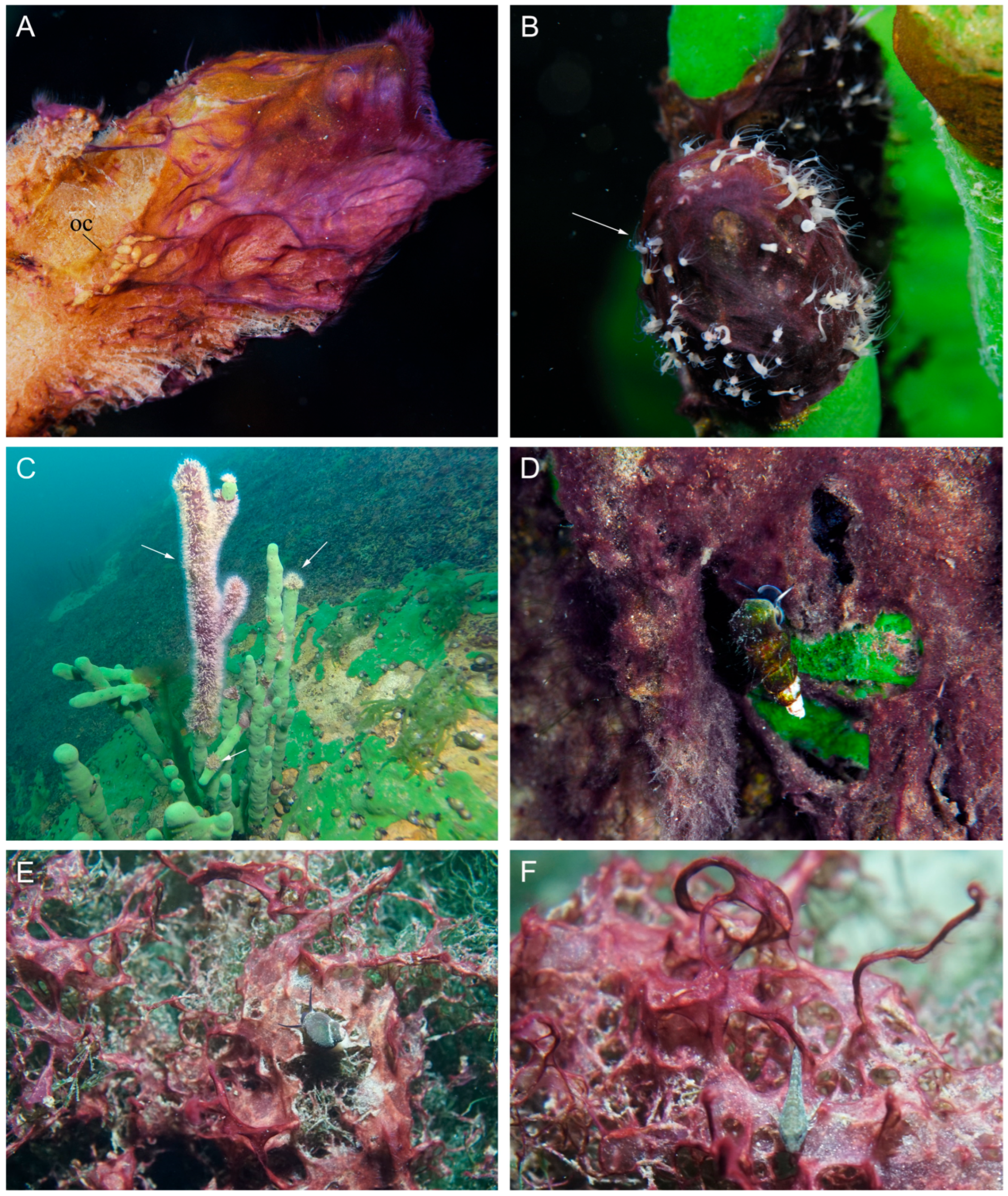

The proliferation of Tychonema sp. has been observed in Lake Baikal since approximately 2010. The species has been found at depths ranging from 0.2 to 15 m (exceptionally to 20 m) along the entire shoreline, persisting year-round. It occurs on various substrates, including stony and sandy surfaces, diseased encrusting and branching sponges, decaying macrophytes, as well as on submerged objects such as wood, steel, glass and plastic (Figure 1A–F).

Figure 1.

Ecology of cyanobacteria Tychonema litorale sp. nov. in Lake Baikal: substrate diversity. (A,B) Sand and macrophytes. (C) Encrusting sponge Baikalospongia sp. (D) Branched sponge Lubomirskia baikalensis. (E) Wood (log from a pier in Bolshiye Koty settlement, the type locality). (F) Stone. Arrows indicate tufts at the tops of the creeping mat ridges.

Particularly dense fouling was documented in Shunte Bay, south of Cape Shunte-Levy (the northern tip of the seaward margin of Olkhon Island). Here, the sandy bottom was completely overgrown by Tychonema biofilm, reaching up to 100% projective cover in some areas (Figure 1A,B).

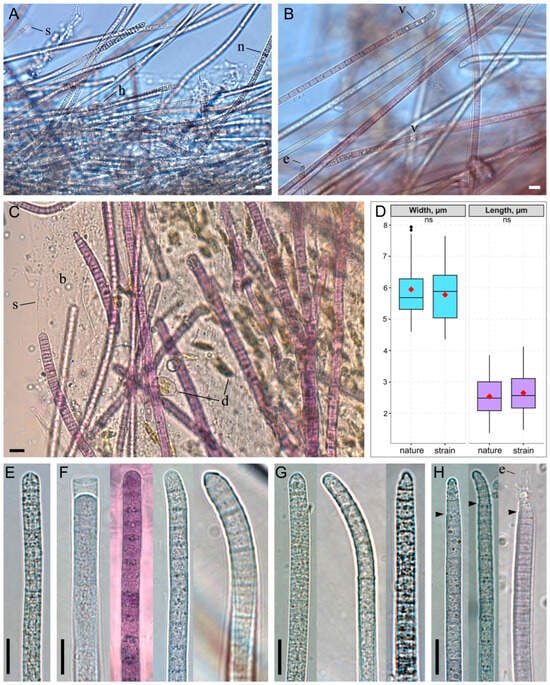

3.2. Morphological Investigation of Natural Samples

The thallus formed a thin, “creeping mat”—a biofilm with localized thickenings forming ridges, each bearing a tuft at its top (Figure 1B,E,F). The biofilm color was most frequently purple to red-brown, and more rarely gray or olive-green. Trichomes were pink or grayish-green, cylindrical or gradually narrowed, and not constricted at the cross-walls; they were rarely abruptly narrowed and occasionally hooked at the ends (Figure 2A–H). Trichomes embedded within the biofilm were enclosed in a thin, colorless sheath, while free ends typically lacked a sheath. Cell dimensions varied: width ranged from 4.6 to 7.9 µm (mean = 5.9 µm, SD = 0.9), and length ranged from 1.4 to 3.9 µm (mean = 2.5 µm, SD = 0.6) (Figure 2D). Apical cells were rounded, sometimes with a thickened outer cell wall, or rounded-conical (up to 1.3 µm narrower than the trichome) and capped by a calyptra (Figure 2E–H). The cell content was typically finely granulated throughout, with large yellowish granules, or appeared granular specifically at the cross-walls. Less commonly, trichomes contained prominent keritomized cells or large vacuoles (Figure 2A,B). Trichomes exhibited pronounced gliding and oscillatory motility, complicating microscopic observation of live samples (Supplementary Video S1). Rarely, biofilms were observed in which many trichomes carried a bundle of epiphytic bacteria on their apical cells (Figure 2B,H).

Figure 2.

Morphology of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. in benthic biofilms. (A–C) Biofilm diversity showing different trichome types: (A) keritomized, (B) vacuolated, (C) finely granulated. (D) Box plot of cell dimensions (width and length) measured from microphotographs of natural samples and cultured strain. The red rhombus represents the mean; the line, the median; the box, the interquartile range (Q1–Q3); and the whiskers, the variability outside Q1 and Q3 (n = 200). Statistical differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test (ns: not significant). (E–H) Different types of trichome morphology: (E) cylindrical and straight, (F) cylindrical with a thickened outer cell wall or calyptra, occasionally hooked, (G) gradually narrowed towards the end, with a thickened outer cell wall or calyptra, often hooked, (H) abruptly narrowed towards the end and calyptrate. Designations: arrows—abrupt trichome narrowing, b—biofilm polysaccharide matrix, d—diatom algae cells, e—epiphytic bacteria, h—hormogonium, n—necridic cells, s—sheath, v—vacuoles. Scale bars: (A–C,E–H) 10 μm.

3.3. Morphological Investigation of Strain

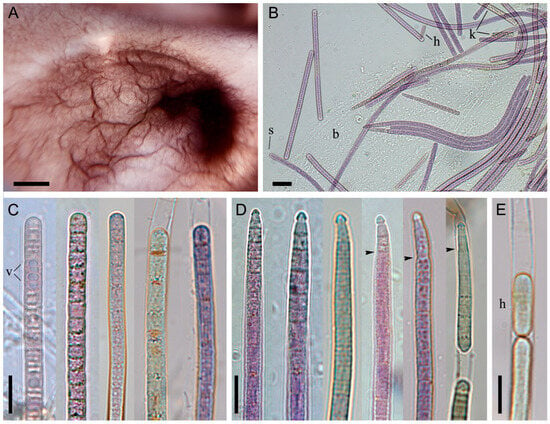

Strain BBK16 was isolated from biofouling on the submerged logs of a wooden pier in the Bolshiye Koty settlement. While the maternal biofilm was olive green in situ (Figure 1E and Figure A1), the strain in culture exhibited a red-brown coloration (Figure 3A), confirming chromatic adaptation characteristic of the genus Tychonema. However, the strain retained its native biofilm morphology, forming a creeping mat attached to the bottom of the culture flask in liquid medium (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Morphology of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. strain BBK16. (A) Creeping mat-type biofilm at the bottom of a culture flask in liquid medium, showing characteristic ridge-like thickenings. (B) Light microscopy of the biofilm. (C) Cylindrical, straight trichomes, some with a thickened outer cell wall. (D) Trichomes narrowed towards the end, bearing a calyptra. (E) Hormogonium formation. Designations: arrows—abrupt trichome narrowing, b—biofilm polysaccharide matrix, h—hormogonium, k—trichomes with keritomized cells, s—sheath, v—vacuoles. Scale bars: (A) 0.5 cm; (B) 20 μm; (C–E) 10 μm.

Sheaths were thin or absent (Figure 3B). Trichomes were straight, without constrictions at the cross-walls (which were scarcely visible), and were sometimes narrowed and hooked towards the end. Apical cells were rounded or obtusely conical, often bearing a calyptra (Figure 3C–E). Abruptly narrowed and calyptrate trichomes were more frequently observed in culture than in natural samples. Trichome width ranged from 4.4 to 7.7 µm (mean = 5.8 µm, SD = 0.8), and cell length ranged from 1.5 to 4.0 µm (mean = 2.7 µm, SD = 0.6). These cell dimensions did not differ significantly between cultured and natural samples according to the Mann–Whitney U test (Figure 2D). Reproduction occurred via trichome disintegration into small fragments, the hormogonia (Figure 3E).

3.4. Differentiation from Similar Species

Tychonema litorale sp. nov. fits well within the morphological description of the genus Tychonema, as it exhibits fine benthic, tychoplanktonic mats; cylindrical trichomes that are facultatively with thin sheaths; cells often with granulated, keritomized, or vacuolized chromatoplasm; apical cells with a thickened cell wall or calyptra; and the ability for chromatic adaptation (Figure 2B–H and Figure 3A–E).

However, Tychonema litorale sp. nov. displays several unique autapomorphies that support its designation as a new species. These diagnostic features include: (1) the characteristic “creeping” biofilm morphology with ridged undulations bearing terminal tufts (Figure 1B,E,F and Figure 3A); (2) its dimensions, with trichomes being wider or narrower than those of other Tychonema species; and (3) diverse trichome end configurations, such as narrowed or sharply narrowed and sometimes curved ends, featuring either a rounded apical cell with a thickened cell wall or a conical apical cell with a calyptra (Figure 2E–H and Figure 3C–E).

The morphologically closest taxon to Tychonema litorale sp. nov. is T. tenue, from which it differs by the presence of narrowed trichomes with a conical, calyptrate apical cell, a smaller minimum trichome width, and its distinct ecology (Table 1). As described, T. tenue is typically found in swamps, growing epiphytically on plants, and is frequently observed as secondarily free-floating, primarily in tychoplanktonic communities [3]. In contrast, Tychonema litorale sp. nov. was collected from a variety of substrates, including sponges, in the littoral zone of a cold lake environment (Table 1). Both T. bourellyi (planktonic) and T. bornetii (benthic, periphytic) have been reported from cold lakes. However, they differ from Tychonema litorale sp. nov. by having thinner and thicker trichomes, respectively, and by lacking both narrowed trichomes and sheaths (Table 1). A previously described Baikal morphospecies, Oscillatoria sp. 1, was considered by us to be highly similar to Tychonema litorale sp. nov. Nevertheless, it differs slightly in trichome width, the absence of sheaths, its occurrence, and thallus color (Table 1).

Table 1.

Morphological comparison of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. with related species. Designations: (+) present; (−) absent.

Key differences between Tychonema litorale sp. nov. and unrevised Tychonema species (T. ingricum, T. rhodonema, T. sequanum) include its planktonic occurrence in rivers, non-colonial habit, the absence of sheaths and calyptras, and its cylindrical trichomes (Table 1). Conversely, the benthic species T. decoloratum has significantly broader trichomes than T. litorale sp. nov., and also lacks sheaths and calyptras.

In light of the close genetic affinity between Tychonema and Microcoleus, particularly M. anatoxicus, we considered the morphological features of the latter (Table 1). Although Tychonema litorale sp. nov. exhibits comparable cell widths and trichome morphology to M. anatoxicus, it is distinguished by the following features: (1) trichomes with curved ends and cells displaying keritomy and vacuolization; (2) the absence of capitate apical cells and lamellate sheaths; and (3) its occurrence on various substrates, avoiding silty ones, in contrast to M. anatoxicus, which is reported exclusively from muddy substrates [22].

M. baikalensis, present in Lake Baikal, is characterized by trichomes that are significantly narrower than those of Tychonema litorale sp. nov., whereas M. subtorulosus exhibits wider trichomes (Table 1). Both Baikal Microcoleus species are further differentiated by their trichomes, which lack calyptras and are arranged into thick bundles within a common, widened sheath. Moreover, these Microcoleus species demonstrate a distinct preference for silty substrates. This stands in stark contrast to T. litorale sp. nov., which was documented on a variety of substrates within Lake Baikal but was never found on silt (Table 1).

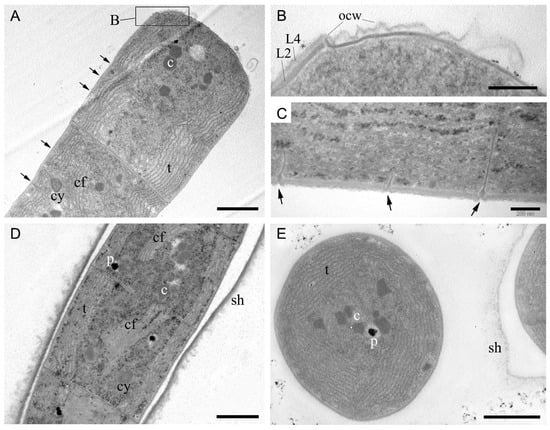

3.5. Cell Ultrastructure

In non-keritomized cells, the thylakoids were arranged in fascicles, typically parietal, or with a central fascicle traversing the cell interior (Figure 4A,D,E). Whilst radial thylakoids are specified in the description of the genus Tychonema, a fascicular arrangement of thylakoids is equally characteristic of representatives of the family Microcoleaceae [3,11]. The cell wall comprised four layers, with the peptidoglycan layer of equal thickness to the outer membrane (Figure 4B). Figure 4B shows the initial stage of calyptra formation, where the outer apical cell wall has not yet thickened but has already separated. Strain BBK16 exhibited type D cell division [1], in which cross walls for subsequent divisions are initiated before cell division is complete (Figure 4A,C,D). Some trichomes were enclosed in fine sheaths with a fibrillar, loose outer border (Figure 4D,E); this feature likely facilitates the formation of the biofilm matrix. Cytoplasmic inclusions were represented by carboxysomes, which were either grouped or solitary, as well as polyphosphate and cyanophycin granules (Figure 4A,D,E).

Figure 4.

Ultrastructure of cells of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. strain BBK16 based on transmission electron microscopy. (A) Fascicular thylakoids and type D cell division. (B) Cell wall structure showing a peptidoglycan layer (L2) of equal thickness to the outer membrane (L4). The initial stage of calyptra formation is visible at the top. (C) Absence of constrictions and type D cell division. (D) Longitudinal section of a trichome within a polysaccharide sheath, showing various inclusions and central fascicles of thylakoids. (E) Transverse section of trichomes with parietal fascicular thylakoids and a fine sheath. Designations: arrow—transverse septum of a dividing cell, c—carboxysome, cf—central fascicle of thylakoids, cy—cyanophycin granule, L2—peptidoglycan layer of cell wall, L4—outer membrane, ocw—outer cell wall of apical cell, p—polyphosphate granule, sh—sheath, t—thylakoids. Scale bars: (A,D,E) 1 μm; (B,C) 200 nm.

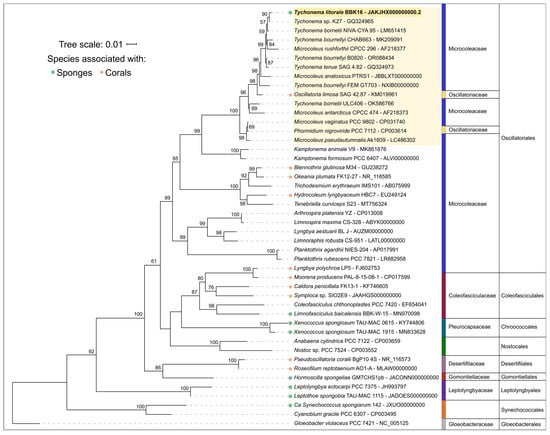

3.6. Molecular and Phylogenetic 16S rRNA Gene Analyses

A search against the NCBI GenBank database using BLASTN (version 2.17.0+) revealed that the closest relative of the 16S rRNA gene sequence from Tychonema litorale sp. nov. strain BBK16 is Tychonema sp. strain K27, with 99.8% pairwise identity. This strain was isolated from a tufa-forming biofilm in a freshwater stream in Germany (GenBank accession GQ324965). Other close relatives, with sequence similarities of 99.3–99.5%, included strains of T. bourrellyi, T. bornetii, and T. tenue isolated from lakes and rivers in Norway, Italy, and China. Furthermore, the 16S rRNA gene sequence of T. litorale sp. nov. showed 99.6–100% similarity to previously obtained sequences from uncultured clones associated with sponge fouling communities in Lake Baikal (GenBank accessions KX348285–KX348287 [36]).

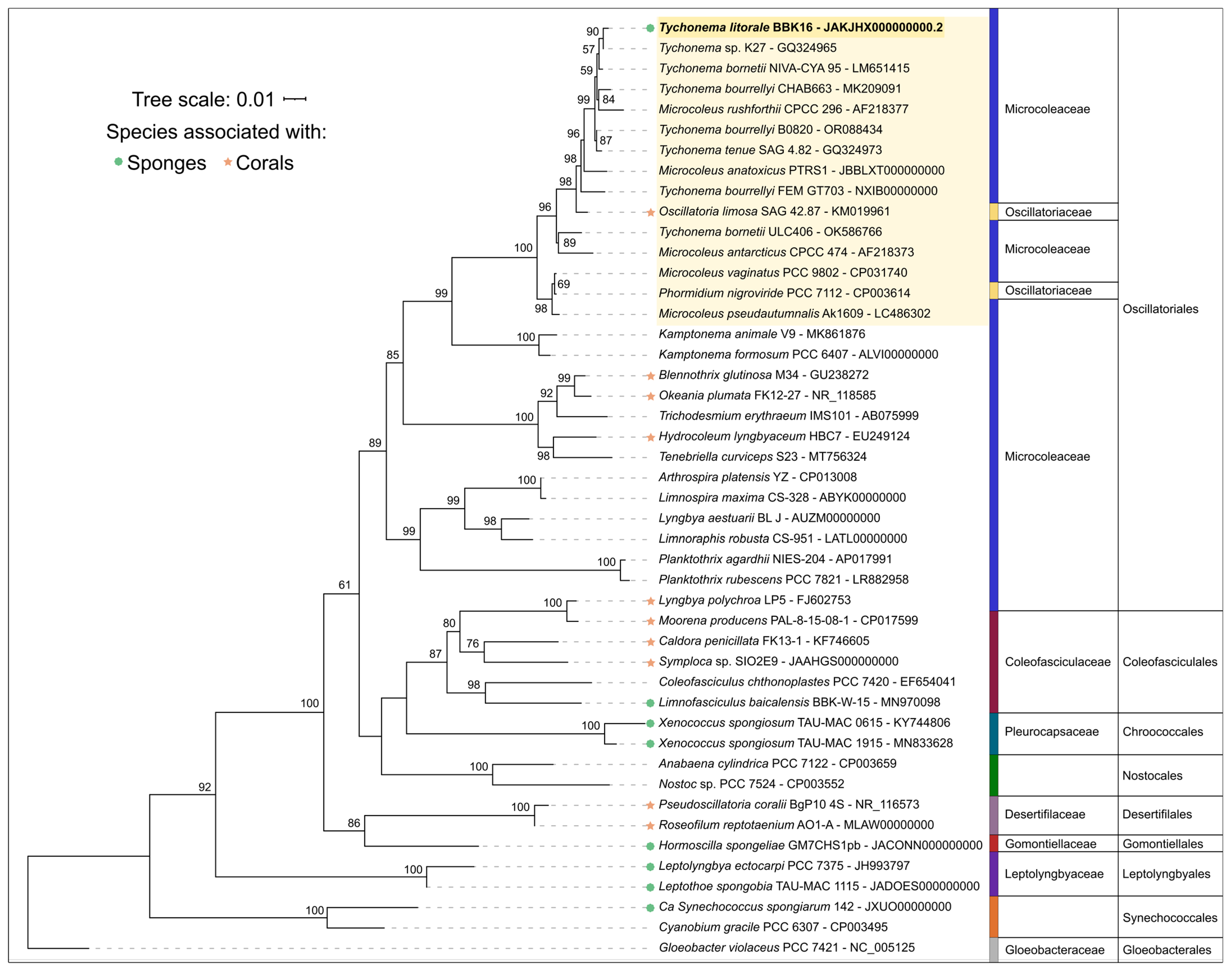

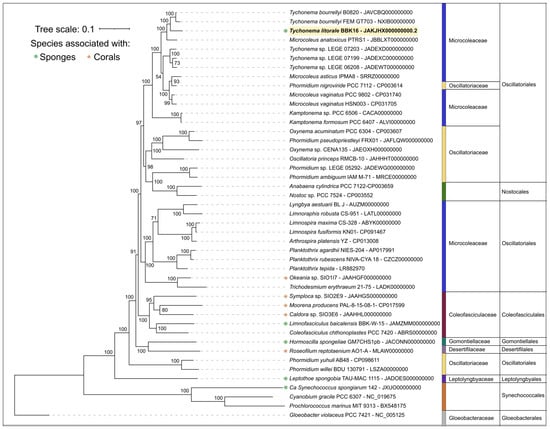

The 16S rDNA phylogenetic tree placed all the Tychonema strains and several Microcoleus, Phormidium and Oscillatoria strains into a clade with 100% bootstrap support (Figure 5); this placement was also supported by Bayesian inference with posterior probability 1.00 (Supplementary Figure S1). Strains BBK16 and K27 formed a separate branch of benthic biofilm-forming Tychonema species in this clade. Tychonema litorale sp. nov. is the only species in this clade associated with sponge fouling and disease. It is noteworthy that Oscillatoria limosa, also in this clade, has been previously implicated in coral fouling [58].

Figure 5.

Best-scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences for 46 taxa. Numbers at branches indicate bootstrap support values as a percentage of 1000 replicates. The sequence of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 is in bold, the Tychonema/Microcoleus/Phormidium clade is highlighted in yellow. Taxonomic assignments to family and order follow the revisions of Strunecký et al. [59].

3.7. 16S–23S ITS Secondary Folding Structure Analysis

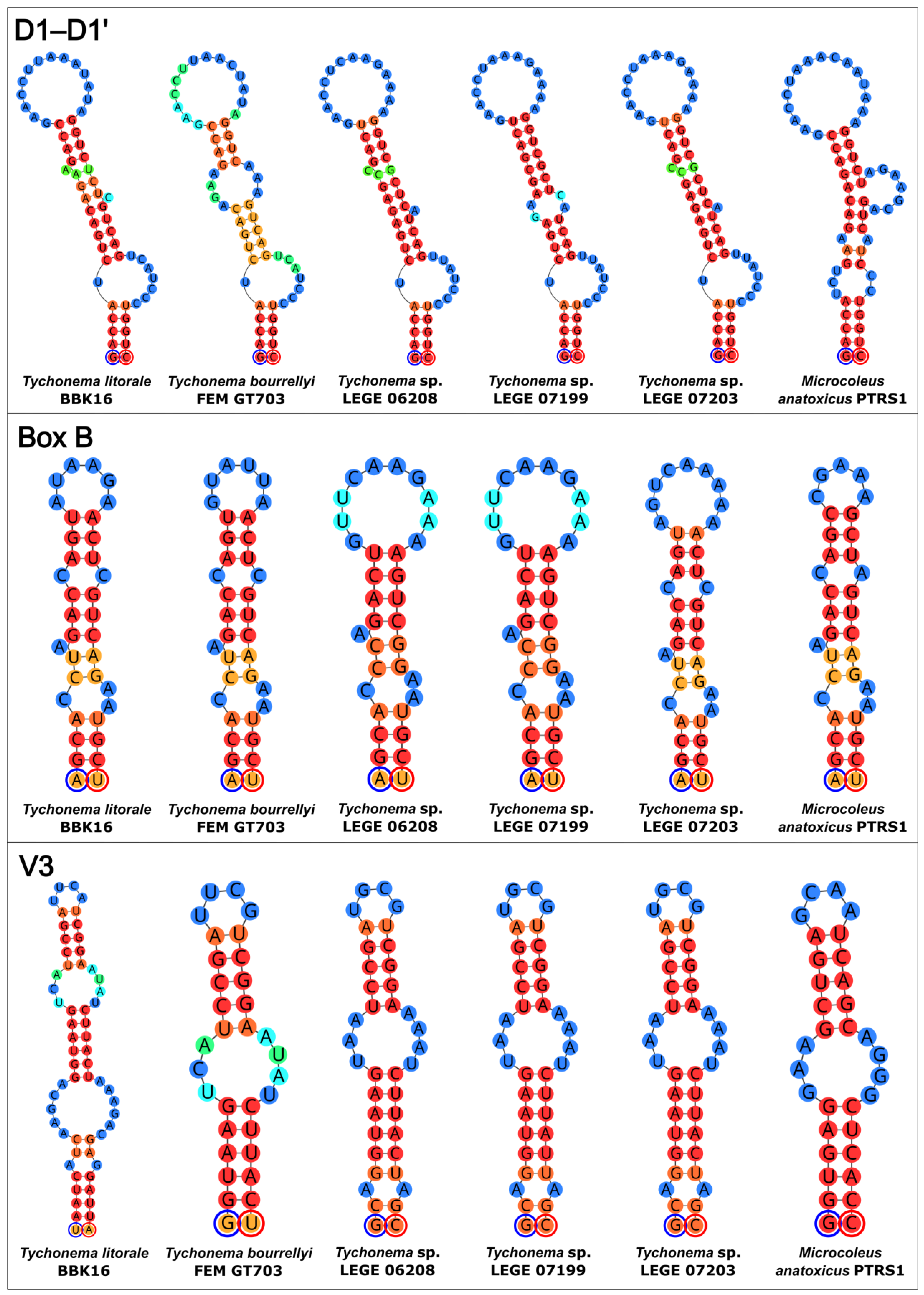

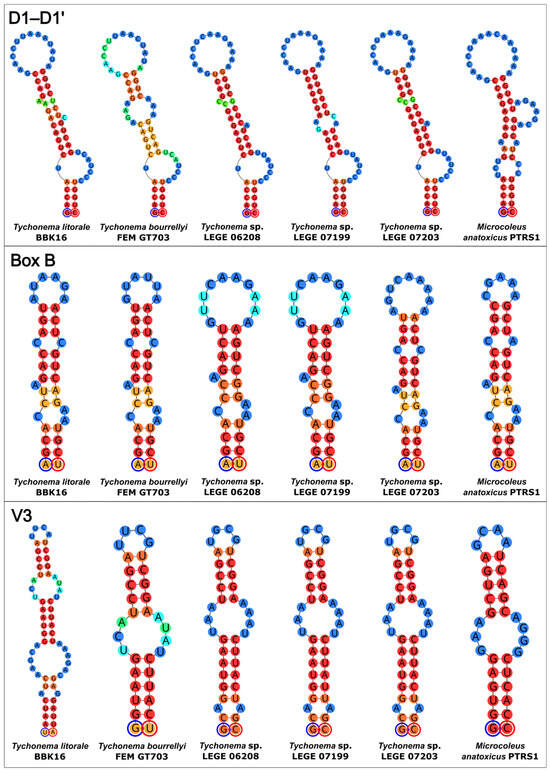

The secondary structures of the 16S–23S ITS regions were predicted for key strains identified by sequence comparison and phylogeny (Figure 6). The analyzed strains included Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16, the closely related T. bourrellyi FEM GT703, three Tychonema sp. strains from a Portuguese wastewater treatment plant (LEGE 06208, 07199, 07203), and the most similar Microcoleus sequence (M. anatoxicus PTRS1). The Tychonema structures of the ITS regions displayed common features that were absent in M. anatoxicus.

Figure 6.

Predicted secondary structures of the D1–D1′, Box B, and V3 helices within the 16S–23S rRNA ITS regions of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 and its most closely related taxa. Each circle represents a nucleotide. The color gradient indicates base-pairing probability, ranging from blue (0%) to red (100%). The 5′-end of each helix is marked with a blue circle and the 3′-end with a red circle.

The D1–D1′ helix of M. anatoxicus was distinct, featuring an additional one-sided bulge, a loop, and a prominent bulge near the base of the hairpin. It also differed from all Tychonema D1–D1′ helices in the size of its central loop. Among the Tychonema helices themselves, variations were observed; the D1–D1′ helix of T. bourrellyi was characterized by a larger central bilateral bulge compared to other Tychonema spp. The helix of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 was most similar to those of Tychonema sp. LEGE 06208 and LEGE 07203.

The Box B helices of all analyzed strains shared similar basal regions but showed variation in the secondary structure of their central parts. Notably, the Box B helix of strain BBK16 retained common structural features with those of M. anatoxicus, T. bourrellyi, and Tychonema sp. LEGE 07203.

The most distinctive helix was the V3 of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16. It differed from its counterparts in both size and overall architecture. While its central part shared sequence and structural similarity with that of T. bourrellyi, the BBK16 V3 helix appeared to possess an additional basal region (Figure 6).

3.8. Genome-Based Comparisons: ANI, AAI, dDDH, Phylogenomics, and Statistics

ANI calculations were performed using the genomic sequences of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 and all available genomes of Tychonema and other closely related Oscillatoriales strains deposited in GenBank as of June 2024. The highest ANI value of 90.7% was found for the genomic sequences of T. bourrellyi B0820 and T. bourrellyi FEM GT703 strains (Supplementary Figure S2 and Table S1). The next highest ANI value, 86.2%, corresponded to Microcoleus anatoxicus PTRS1. ANI values with other members of the Tychonema/Microcoleus/Phormidium clade were approximately 83%. All these values are below the standard 95–96% ANI cutoff for prokaryotic species demarcation when using complete or nearly complete genomes [60].

Consistent with the ANI results, the closest available genomes (T. bourrellyi B0820 and T. bourrellyi FEM GT703) showed AAI values of 91.1–91.2% and dDDH (f2) values of 43.3% to strain BBK16 (Supplementary Table S1). These AAI and dDDH values are well below established species delineation thresholds (approximately 95–96% AAI and 70% dDDH) [61,62], providing additional genomic support for delimiting strain BBK16 as a novel species.

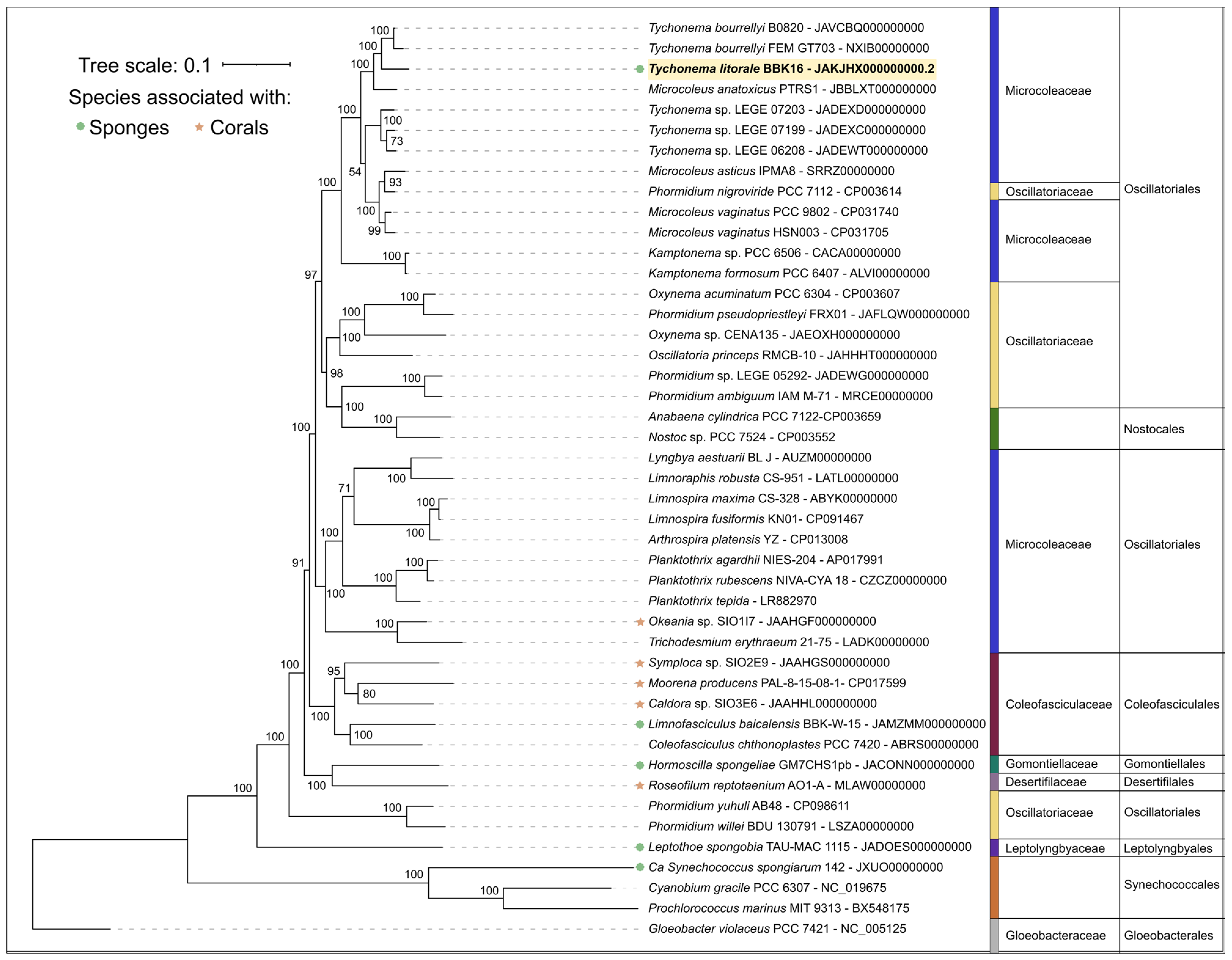

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the PhyloPhlAn pipeline, which employs 400 most conserved proteins and is able to provide a better resolution and statistical support than the 16S rDNA-based tree, ML and Bayesian inference (Figure 7 and Supplementary Figure S3). This phylogenomic tree, constructed sequences representing most available Tychonema, Microcoleus, Phormidium strains as well as other cyanobacterial groups, placed Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 together with T. bourrellyi strains B0820 and FEM GT703 into a distinct clade. The Tychonema LEGE strains formed a paraphyletic group.

Figure 7.

Maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 (highlighted in bold and yellow in the tree) and related cyanobacterial taxa, inferred from 45 concatenated amino acid sequences of 400 conserved proteins. Taxonomic ranks are indicated to the right of the organism names. Bootstrap support values from 1000 replicates are shown at the nodes.

Based on phylogenetic and genomic (ANI) evidence, it can be concluded that Tychonema litorale sp. nov. is a new species of the genus Tychonema, family Microcoleaceae. Notably, the genus Tychonema was not monophyletic in either the 16S rDNA tree or the phylogenomic tree based on conserved proteins.

The complete genome of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 was assembled into 5,813,203 bp, with high estimated completeness (CheckM2: 98.94%) and low contamination (0.01%). Its size and G+C content (44.2%) fall within the ranges reported for other Tychonema species (genome size: 5.08–6.70 Mbp; G+C: 44.7–46.0%) in the NCBI Genome database.

3.9. Biosynthetic Potential of Tychonema litorale sp. nov.

Analysis with AntiSmash did not detect any known toxin biosynthesis gene clusters in the genome of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16. However, biosynthetic gene clusters were identified for the synthesis of carotenoids, non-ribosomal cyclic peptide trichamide, and amino acid shinorine.

TLC separation of the BBK16 extract revealed four intensely yellow spots. MALDI-MS analysis identified lutein in one of these spots based on an intense radical cation signal at m/z 568.4. The other three spots likely contain carotenoid derivatives, which could not be definitively identified. Zeaxanthin and β-carotene were not detected in the extract.

4. Discussion

Cyanobacteria, the most common symbionts of healthy marine sponges, are generally members of the orders Chroococcales and Synechococcales (Figure 5) [63]. Numerous Oscillatoriales, including an unidentified Tychonema sp., have been reported as biofilm formers on coral reefs [64,65]. Of particular note are filamentous cyanobacteria associated with sponge and coral diseases. Many of these species were first identified and described during investigations of the disease cases themselves. For example, mats of Pseudoscillatoria coralli and Roseofilum reptotaenium can encircle coral colonies, causing black band disease and death of coral polyps [66,67]. In Okinawa, Japan, a bloom of the cyanobacterium Moorena bouillonii on gorgonian corals caused significant mortality [68]. Similarly, the filamentous cyanobacterium Hormoscilla spongeliae was identified within the bleached parts of diseased sponges [28].

In Lake Baikal, a six-year observational study (2015–2021) documented a twofold decrease in the benthic area covered by sponges. Five distinct types of sponge damage were recorded, with ‘cyanobacterial biofilm’ being the second most frequent type, occurring in 29% of cases [31]. By describing Tychonema litorale sp. nov., we contribute new data on epizoic cyanobacteria potentially associated with sponge diseases. This species represents the second novel cyanobacterium recently described from the Lake Baikal benthos. The first, Limnofasciculus baicalensis, forms bushy biofouling on the bottom and is also found on sponges, though it is less abundant than Tychonema [69].

Our previous in situ studies indicated that Tychonema litorale sp. nov. is a native Lake Baikal organism that was historically not abundant. Its biofilms were rarely observed on diseased sponges or decaying macrophytes, and never exceeded 1–3 cm2 in size [35]. The proliferation of Tychonema observed on the lake bottom since 2010 is likely directly related to ongoing ecological disturbances in the Baikal littoral zone. These include algal blooms and subsequent decomposition, as well as the mass mortality of sponges [32]. Furthermore, the excessive organic matter and nutrients released during the death and decay of these organisms are critical factors promoting the proliferative growth of Tychonema. Interestingly, related Tychonema sp. strains from the LEGE collection, which are phylogenetically close to Baikal species, were isolated from biofilm on the wall of a secondary decanter tank in a wastewater treatment plant [70]. This suggests that Tychonema likely plays a sanitary role in Lake Baikal, though its ecological function is not limited to nutrient processing.

For instance, biofilms on sponges harbor a rich infauna of nematodes—up to 16,000 individuals per dm2 [71]. Findings of oligochaete cocoons confirm the diversity of worms inhabiting Tychonema biofilms (Figure A2A). The biofilm surface is regularly densely populated by hydras (Hydra, Cnidaria, Hydrozoa), which selectively attach only to Tychonema-covered areas of the sponge [72]. This suggests that bacterial abundance associated with sponge decomposition attracts zooplankton, which in turn draws predatory hydras, forming a unique consortium (Figure A2B,C). Additionally, endemic Baikal gastropods graze on Tychonema [73]. Based on our extensive observations of sandy substrates, we conclude that juvenile sculpins use Tychonema biofilms as their primary refuge from predators (Figure A2F).

The cyanobacterium Oscillatoria sp. 1, previously described in Lake Baikal [56], shares key morphological and distributional features with Tychonema litorale sp. nov. Key differences include the blue-green color of its trichomes—a trait not characteristic of Tychonema—and its lack of sheaths. Olive-green biofilms dominated by sharply constricted trichomes with bundles of epiphytic bacteria on their calyptra can be identified as Phormidium autumnale. Conversely, formalin-fixed, bleached biofilms dominated by trichomes with briefly attenuated, rounded-conical, and bent ends are characteristic of Phormidium breve or Kamptonema spp. We have included numerous images of various trichomes and biofilms to illustrate the morphological variability of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. in the lake. Although identifying such samples can be challenging, careful examination reveals diagnostic features: distinct keritomy, cellular vacuolization, thickened outer cell walls, and solitary trichomes with well-developed calyptra. The frequency of trichomes with modified apical cells varies considerably, likely due to environmental factors. As calyptrated trichomes are rare in most field samples, a minimum of 20 trichomes should be examined for reliable specimen identification [74].

The genus Tychonema is polyphyletic, and its taxonomic revision has long been recognized as necessary, yet a resolution remains elusive [39]. A recent large-scale 16S rDNA metabarcoding survey of alpine lakes and rivers found Tychonema phylotypes to be among the dominant lineages in these ecosystems [75]. On the resulting phylogenetic tree, these phylotypes formed three distinct clades. Only one of these clades appears to represent the core of this problematic genus [75]. Furthermore, phylogenomic analyses suggest that Tychonema and Microcoleus form a monophyletic group, indicating that their generic boundaries may need to be revisited [59].

The morphology and ultrastructure of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. (strain BBK16) show several traits also reported for Microcoleus, including narrowed trichome ends with calyptras, fascicular organization of thylakoids, and the cell division type [11]. Nevertheless, our ML phylogeny recovers the Tychonema clade with strong bootstrap support (99%), and genome-wide similarity of BBK16 is higher to Tychonema bourrellyi than to Microcoleus anatoxicus (ANI 91% vs. 86%, respectively). Together with the qualitative differences observed in the predicted 16S–23S ITS secondary structures, these data support the taxonomic placement of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. within the genus Tychonema, pending further clarification of the taxonomy of the Tychonema/Microcoleus group.

The genomic search using AntiSmash revealed only three biosynthetic gene clusters in Tychonema litorale. This is a minimal number for a benthic species associated with sponges and corals, and is comparable to that of non-toxic planktonic cyanobacteria [69]. One cluster encodes shinorine, a rare natural mycosporine-like amino acid with high UV-absorption potential. Due to its good water solubility, shinorine is well-suited for use in sunscreen cosmetic formulations [76]. Carotenoid diversity in the studied strain was limited compared to Tychonema sp. LEGE 07196, as determined by TLC–MS and supported by the identified biosynthesis genes. The LEGE 07196 strain contains zeaxanthin, canthaxanthin, and a lutein derivative, and shows high antioxidant activity with potential for cosmetic applications [77]. In contrast, we detected only lutein and three unidentified carotenoid derivatives in Tychonema litorale.

Previously, specific carotenoid sugar moieties—myxol-2″-O-methyl-methylpentoside (C47H68O7) and oscillol-2,2′-di-(O-methylmethylpentoside) (C54H80O16)—were reported as characteristic for the genus Tychonema [1]. These were identified in Oscillatoria bourrellyi f. tenue (=Tychonema tenueT). However, corresponding m/z values for these carotenoids were not detected in the MALDI mass spectra of strain BBK16. This implies that these sugar moieties might not be exclusive chemotaxonomic markers for the genus.

5. Taxonomic Description

- Thallus forming purple to red-brown, rarely gray or olive-green fine creeping mats with ridge-like thickenings and tufts of free trichomes on the tops. In nature, mats are attached to sponges, macrophytes, stones, sand, submerged wood, and other objects (Figure 1). Sheaths absent or thin, colorless, and merging into a common matrix within the biofilm (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Trichomes straight, not constricted at the cross-walls, cylindrical or gradually narrowed, rarely abruptly narrowed, and sometimes hooked at the ends, with gliding and oscillating motility, 4.4–7.9 µm wide. Cells are shorter than wide, 1.4–4.0 µm long, with granulation in the centroplasm or at cross-walls, sometimes with 1–2 large vacuoles or keritomized. Apical cell rounded or rounded-conical, sometimes with a thickened outer cell wall or a calyptra. Cell division is Type D; thylakoids are fascicular and parietal (Figure 4). Reproduction occurs via motile hormogonia formed by fragmentation of the trichome (Figure 3E).

- HOLOTYPE: IRKU 092122, deposited in the Herbarium of Irkutsk State University (IRKU), Department of Botany and Genetics, Irkutsk State University, Irkutsk, Russia.

- TYPE STRAIN: IPPAS B-2063 (BBK16).

- AVAILABLE SEQUENCE: JAKJHX000000000.2 (genome assembly).

- HABITAT: Freshwater.

- TYPE LOCALITY: Lake Baikal, near Bolshiye Koty settlement, Russia, 51°53′57.5″ N, 105°03′52.2″ E (Figure A1).

- DISTRIBUTION: Lake Baikal, Russia.

- ETYMOLOGY: Li.to.ra’le. L. neut. adj. The specific epithet ‘litorale’ means ‘coastal’ referring to the distribution of this species in the littoral zone of the deep-water Lake Baikal.

- DIAGNOSIS: This species is morphologically similar to the cyanobacteria of the genus Tychonema. The main distinguishing morphological features are growth as a creeping mat, highly motile trichomes that are sometimes narrowed and hooked towards the ends, and the presence of rounded-conical apical cells with a calyptra. Key ecological characteristics include a benthic freshwater habitat and attachment to a variety of substrates, with high tropism for damaged and decomposed macrophytes and sponges. The cellular ultrastructure is characterized by a parietal, fascicular arrangement of thylakoids with a central bundle crossing the cell interior. Phylogenetically, conserved protein analysis demonstrates that strain BBK16 shares a paraphyletic branch with T. bourrellyi (Figure 7), with an ANI value of 91%, which is below the standard species threshold. Analysis of the secondary structures of the 16S–23S ITS region shows notable differences from other Tychonema spp. in the size and overall structure of the V3 helix (Figure 6).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18020084/s1, Figure S1: Bayesian inference phylogeny based on 16S rDNA sequences. Numbers at nodes indicate posterior probabilities. Scale bar indicates expected substitutions per site. The sequence of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 is boxed, the Tychonema/Microcoleus/Phormidium clade is highlighted in yellow. The average standard deviation of split frequencies was 0.013635; Figure S2: Heatmap and dendrogram based on pairwise average nucleotide identity values, reflecting genomic similarity; Figure S3: Phylogenetic tree inferred using Bayesian inference from a concatenated alignment of 400 conserved proteins. Numbers at nodes indicate posterior probabilities. Scale bar indicates expected substitutions per site. The sequence of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 is highlighted in yellow. The average standard deviation of split frequencies was 0.000163; Table S1: Average nucleotide identity (ANI), average amino acid identity (AAI), and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) values between the cyanobacterium Tychonema litorale sp. nov. BBK16 and representatives of other cyanobacterial taxa; Video S1: Active gliding motility of Tychonema trichomes in a living biofilm sample from a sponge, North Baikal, 10 m depth. Light microscopy (×200), recorded in real time with a digital camera (Meiji Techno, Japan).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.S., I.T. and P.E.; investigation, E.S., P.E., I.T., A.K., S.P., G.F., D.G. and A.G.; diving work, I.K. and I.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S., P.E., O.T. and I.K.; writing—review and editing, E.S., P.E., O.T. and O.B.; funding acquisition, O.B.; supervision, O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, Project No. 1023032700318-2-1.6.2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the divers, Yu. Yushchuk and V. Chernykh, for sampling and the crew of R/V Titov (from The Center for Collective Use “Research vessels Center of LIN SB RAS on Lake Baikal”) for their assistance. We also thank our colleagues from the Limnological Institute SB RAS: E.D. Bedoshvili for assistance with transmission electron microscopy; T.V. Naumova for interpreting photographs of the worms’ cocoons; T.Ya. Sitnikova for the identification of gastropods; and Ye.M. Timoshkina for assistance with text translation. We extend our thanks to K.S. Zariņa from the Museum of the University of Latvia, Botanical and Mycological Collection, for providing the photograph of the article by H.L. Skuja. Finally, we are grateful to M.A. Sinetova from the Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology RAS for the warm welcome and deposit of the strain to the IPPAS collection. This study was carried out at The Shared Research Facilities for Physical and Chemical Ultramicroanalysis LIN SB RAS and the Experimental Freshwater Aquarium Complex for Baikal Hydrobionts (http://www.lin.irk.ru/aqua accessed on 10 December 2025). English language editing was performed using DeepSeek-R1 reasoning model (https://www.chat.deepseek.com, accessed on 16 January 2026).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANI | Average nucleotide identity |

| AAI | Average amino acid identity |

| dDDH | Digital DNA–DNA hybridization |

| MALDI-TOF-MS | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry |

| TLC | Thin layer chromatography |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Type locality of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. (A) Lake Baikal. Wooden pier located in the area of the Scientific Research Station of the Limnological Institute in Bolshiye Koty settlement. View from the south. (B) The western wall of the pier. (C) Log end with cyanobacterial fouling. (D) The upper part of the log completely covered with Tychonema biofilm (September 2015).

Figure A1.

Type locality of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. (A) Lake Baikal. Wooden pier located in the area of the Scientific Research Station of the Limnological Institute in Bolshiye Koty settlement. View from the south. (B) The western wall of the pier. (C) Log end with cyanobacterial fouling. (D) The upper part of the log completely covered with Tychonema biofilm (September 2015).

Figure A2.

Ecological interactions of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. in the Lake Baikal littoral zone. (A) Oligochaete cocoons (oc) deposited within a Tychonema biofilm on a decaying sponge branch, indicating its role as a substrate for development and reproduction. (B,C) Aggregations of hydra on sponge surfaces overgrown by Tychonema biofilm (arrows), indicating a potential microhabitat association facilitated by the cyanobacterial mat. (D,E) The endemic gastropods Baicalia turriformis and Benedictia baicalensis grazing on the Tychonema biofilm, demonstrating its integration into the benthic food web. (F) A juvenile sculpin (Paracottus knerii) sheltering within macrophytes entangled with Tychonema fouling, highlighting the structural role of the biofilm in providing refuge for fish.

Figure A2.

Ecological interactions of Tychonema litorale sp. nov. in the Lake Baikal littoral zone. (A) Oligochaete cocoons (oc) deposited within a Tychonema biofilm on a decaying sponge branch, indicating its role as a substrate for development and reproduction. (B,C) Aggregations of hydra on sponge surfaces overgrown by Tychonema biofilm (arrows), indicating a potential microhabitat association facilitated by the cyanobacterial mat. (D,E) The endemic gastropods Baicalia turriformis and Benedictia baicalensis grazing on the Tychonema biofilm, demonstrating its integration into the benthic food web. (F) A juvenile sculpin (Paracottus knerii) sheltering within macrophytes entangled with Tychonema fouling, highlighting the structural role of the biofilm in providing refuge for fish.

References

- Anagnostidis, K.; Komárek, J. Modern approach to the classification system of the Cyanophytes 3: Oscillatoriales. Algol. Stud. 1988, 50, 327–472. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase; World-Wide Electronic Publication; National University of Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2009; Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Komárek, J.; Anagnostidis, K. Süβwasserflora von Mitteleuropa; Bd. 19(2). Cyanoprokaryota 2. Teil/Part 2: Oscillatoriales; Springer: Munchen, Germany, 2005; 759p. [Google Scholar]

- Hauer, T.; Komárek, J. CyanoDB 2.0—On-Line Database of Cyanobacterial Genera; World-Wide Electronic Publication; University of South Bohemia & Institute of Botany AS CR: 2022. Available online: http://www.cyanodb.cz (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Government, A.C.T. ACT Water Report 2003–2004; Australian Capital Territory: Canberra, Australia, 2014; p.24. Available online: https://www.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/2537993/act-water-report-2003-04.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Song, G.; Shao, J.; Xiang, X.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yang, P.; Yu, G. Dynamics and polyphasic characterization of odor-producing cyanobacterium Tychonema bourrellyi from Lake Erhai, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 5420–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Sarma, K.; Saini, A.; Kumar, S.; Kant, R. Certain commercially interesting taxa of Phormidioideae, Phormidiaceae (Oscillatoriales cyanoprokaryote) from polluted sites of Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India. Plant Arch. 2021, 21, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahy Mirzahasnlou, J.; Nejadsattari, T.; Ramezanpour, Z.; Imanpour Namin, J.; Asri, Y. Identification of filamentous algae of the Balikhli River in Ardabil province and recording four new species for algal flora of Iran. Nova Biol. Reper 2020, 7, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Pinheiro, M.M.; Temponi Santos, B.L.; Vieira Dantas Filho, J.; Perez Pedroti, V.; Cavali, J.; Brito dos Santos, R.; Oliveira Carreira Nishiyama, A.C.; Guedes, E.A.C.; de Vargas Schons, S. First monitoring of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in freshwater from fish farms in Rondonia state, Brazil. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melechin, A.V.; Davydov, D.A.; Shalygin, S.S.; Borovichev, E.A. Open information system on biodiversity cyanoprokaryotes and lichens CRIS (Cryptogamic Russian Information System). Bull. Mosc. Soc. Naturalists. Biol. Ser. 2013, 118, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Strunecký, O.; Komárek, J.; Johansen, J.; Lukešová, A.; Elster, J. Molecular and morphological criteria for revision of the genus Microcoleus (Oscillatoriales, Cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 2013, 49, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoupý, S.; Stanojković, A.; Casamatta, D.A.; McGovern, C.; Martinović, A.; Jaskowiec, J.; Konderlová, M.; Dodoková, V.; Mikesková, P.; Jahodářová, E.; et al. Population genomics and morphological data bridge the centuries of cyanobacterial taxonomy along the continuum of Microcoleus species. iScience 2024, 27, 109444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuja, H. Vorarbeiten zu einer Algenflora von Lettland 2. Acta Horti Bot. Univ. Latv. 1929, 4, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Suda, S.; Watanabe, M.M.; Otsuka, S.; Mahakahant, A.; Yongmanitchai, W.; Nopartnaraporn, N.; Liu, Y.; Day, J.G. Taxonomic revision of water-bloom-forming species of oscillatorioid cyanobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.; Capelli, C.; Cerasino, L.; Ballot, A.; Dietrich, D.R.; Sivonen, K.; Salmaso, N. Anatoxin-a producing Tychonema (Cyanobacteria) in European waterbodies. Water Res. 2015, 69, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Fastner, J.; Bartha-Dima, B.; Breuer, W.; Falkenau, A.; Mayer, C.; Raeder, U. Mass occurrence of anatoxin-a- and dihydroanatoxin-a-producing Tychonema sp. in mesotrophic reservoir Mandichosee (River Lech, Germany) as a cause of neurotoxicosis in dogs. Toxins 2020, 12, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, L.H.; Huang, Y.; Bermarija, T.D.; Rafuse, C.; Zamlynny, L.; Bruce, M.R.; Graham, C.; Comeau, A.M.; Valadez-Cano, C.; Lawrence, J.E.; et al. Proliferation and anatoxin production of benthic cyanobacteria associated with canine mortalities along a stream-lake continuum. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fastner, J.; Beulker, C.; Geiser, B.; Hoffmann, A.; Kröger, R.; Teske, K.; Hoppe, J.; Mundhenk, L.; Neurath, H.; Sagebiel, D.; et al. Fatal neurotoxicosis in dogs associated with tychoplanktic, anatoxin-a producing Tychonema sp. in mesotrophic Lake Tegel, Berlin. Toxins 2018, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, F.; Stix, M.; Bartha-Dima, B.; Geist, J.; Raeder, U. Spatio-temporal monitoring of benthic anatoxin-a-producing Tychonema sp. in the River Lech, Germany. Toxins 2022, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, A.O. Macrófitos. In Lago de Sanabria 2015. Presente y Futuro de un Ecosistema en Desequilibrio; Edición del Autor/Self-published: Zamora, Spain, 2015; pp. 117–119. Available online: https://duerodouro.org/area-de-investigacion/investigacion-lago-de-sanabria/06-macrofitos (accessed on 25 May 2025)ISBN 978-84-608-2818-1.

- Wood, S.A.; Puddick, J.; Fleming, R.; Heussner, A.H. Detection of anatoxin-producing Phormidium in a New Zealand farm pond and an associated dog death. N. Zealand J. Bot. 2017, 55, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, K.Y.; Stancheva, R.; Otten, T.G.; Fadness, R.; Boyer, G.L.; Read, B.; Zhang, X.; Sheath, R.G. Molecular and morphological characterization of a novel dihydroanatoxin-a producing Microcoleus species (cyanobacteria) from the Russian River, California, USA. Harmful Algae 2020, 93, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadez-Cano, C.; Reyes-Prieto, A.; Beach, D.G.; Rafuse, C.; McCarron, P.; Lawrence, J. Genomic characterization of coexisting anatoxin-producing and non-toxigenic Microcoleus subspecies in benthic mats from the Wolastoq, New Brunswick, Canada. Harmful Algae 2023, 124, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellwood, D.R.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Nyström, M. Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature 2004, 429, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.R.F.; Elmetri, I.; Lapointe, B.E. Evidence of Large-Scale Chronic Eutrophication in the Great Barrier Reef: Quantification of Chlorophyll a Thresholds for Sustaining Coral Reef Communities. AMBIO 2014, 43, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.B.; Gochfeld, D.J.; Slattery, M. Aplysina red band syndrome: A new threat to Caribbean sponges. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2006, 71, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angermeier, H.; Kamke, J.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Krohne, G.; Pawlik, J.R.; Lindquist, N.L.; Hentschel, U. The pathology of sponge orange band disease affecting the Caribbean barrel sponge Xestospongia muta. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 75, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, M.; Bulling, M.; Cerrano, C. A novel sponge disease caused by a consortium of micro-organisms. Coral Reefs 2015, 34, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L.L.; Miller, A.W.; Broderick, E.; Kaczmarsky, L.; Gantar, M.; Stanic, D.; Sekar, R. Sulfide, microcystin, and the etiology of black band disease. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2009, 87, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galaziy, G.I. (Ed.) Baikal. Atlas; Publishing House of the Federal Service for Geodesy and Cartography of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 1993; 160p. [Google Scholar]

- Maikova, O.O.; Bukshuk, N.A.; Kravtsova, L.S.; Onishchuk, N.A.; Sakirko, M.V.; Nebesnykh, I.A.; Lipko, I.A.; Khanaev, I.V. Sponge Fauna of Lake Baikal in the Monitoring System: Six Years of Observations. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2023, 16, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshkin, O.A.; Samsonov, D.P.; Yamamuro, M.; Moore, M.V.; Belykh, O.I.; Malnik, V.V.; Sakirko, M.V.; Shirokaya, A.A.; Bondarenko, N.A.; Domysheva, V.M.; et al. Rapid ecological change in the coastal zone of Lake Baikal (East Siberia): Is the site of the world’s greatest freshwater biodiversity in danger? J. Great Lakes Res. 2016, 42, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belykh, O.I.; Fedorova, G.A.; Kuzmin, A.V.; Tikhonova, I.V.; Timoshkin, O.A.; Sorokovikova, E.G. Microcystins in cyanobacterial biofilms from the littoral zone of Lake Baikal. Mosc. Univ. Biol. Sci. Bull. 2017, 72, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belykh, O.I.; Tikhonova, I.V.; Kuzmin, A.V.; Sorokovikova, E.G.; Fedorova, G.A.; Khanaev, I.V.; Sherbakova, T.A.; Timoshkin, O.A. First detection of benthic cyanobacteria in Lake Baikal producing paralytic shellfish toxins. Toxicon 2016, 121, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshkin, O.A. Coastal zone of the world’s great lakes as a target field for interdisciplinary research and ecosystem monitoring: Lake Baikal (East Siberia). Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 1, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokovikova, E.; Belykh, O.; Krasnopeev, A.; Potapov, S.; Tikhonova, I.; Khanaev, I.; Kabilov, M.; Baturina, O.; Podlesnaya, G.; Timoshkin, O. First data on cyanobacterial biodiversity in benthic biofilms during mass mortality of endemic sponges in Lake Baikal. J. Great Lakes Res. 2020, 46, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evseev, P.; Tikhonova, I.; Krasnopeev, A.; Sorokovikova, E.; Gladkikh, A.; Timoshkin, O.; Miroshnikov, K.; Belykh, O. Tychonema sp. BBK16 characterisation: Lifestyle, phylogeny and related phages. Viruses 2023, 15, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidanova, Y.A.; Sorokovikova, E.G.; Tikhonova, I.V.; Khanaev, I.V.; Belykh, O.I. Investigation of Tychonema sp. tropism to the sponge body in the experiment of co-cultivation of cyanobacteria with primmorphs. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2024, 4, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komárek, J.; Kaštovský, J.; Mareš, J.; Johansen, J.R. Taxonomic classification of cyanoprokaryotes (cyanobacterial genera) 2014, using a polyphasic approach. Preslia 2014, 86, 295–335. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokovikova, E.G.; Tikhonova, I.V.; Belykh, O.I.; Klimenkov, I.V.; Likhoshwai, E.V. Identification of two cyanobacterial strains isolated from the Kotel’nikovskii hot spring of the Baikal rift. Microbiology 2008, 77, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.J. Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual by T. Maniatis, E.F. Fritsch and J. Sambrook. 545 p. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, New York. 1982. Biochem. Educ. 1983, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, Y. ANIclustermap: A Tool for Drawing ANI Clustermap Between All-vs-All Microbial Genomes. Available online: https://github.com/moshi4/ANIclustermap (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Kim, D.; Park, S.; Chun, J. Introducing EzAAI: A pipeline for high throughput calculations of prokaryotic average amino acid identity. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Carbasse, J.S.; Peinado-Olarte, R.L.; Göker, M. TYGS and LPSN: A database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D801–D807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnicar, F.; Thomas, A.M.; Beghini, F.; Mengoni, C.; Manara, S.; Manghi, P.; Zhu, Q.; Bolzan, M.; Cumbo, F.; May, U.; et al. Precise phylogenetic analysis of microbial isolates and genomes from metagenomes using PhyloPhlAn 3.0. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.H.; Mathews, D.H. NNDB: The nearest neighbor parameter database for predicting stability of nucleic acid secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D280–D282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Höner Zu Siederdissen, C.; Tafer, H.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2011, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J.N.; et al. antiSMASH 7.0: New and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagels, F.; Salvaterra, D.; Amaro, H.M.; Lopes, G.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Vasconcelos, V.; Guedes, A.C. Bioactive potential of Cyanobium sp. pigment-rich extracts. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 3031–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhboldina, L.A. Guide and Key to Benthonic and Periphyton Algae of Lake Baikal (Meio- and Macrophytes) with Short Notes of Their Ecology; Nauka-Center: Novosibirsk, Russia, 2007; 248p. [Google Scholar]

- Elenkin, A.A. Blue-Green Algae of the USSR; Special part II; AN SSSR: Moscow, USSR, 1949; 1908p. [Google Scholar]

- Sournia, A. Ecologie et productivité d’une Cyanophycée en milieu corallien: Oscillatoria limosa Agardh. Phycologia 1976, 15, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunecký, O.; Ivanova, A.P.; Mareš, J. An updated classification of cyanobacterial orders and families based on phylogenomic and polyphasic analysis. J. Phycol. 2023, 59, 12–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, A.; Woodhouse, J.N. Defining Cyanobacterial Species: Diversity and Description Through Genomics. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2020, 39, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, K.T.; Tiedje, J.M. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 2567–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.S.; Jung, Y.H.; Kwon, Y.M.; Chung, D.; Yu, W.J.; Kim, T.W.; Hwang, H.J. Agarivorans sediminis sp. nov., an alginate-degrading bacterium isolated from sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2025, 75, 006988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinou, D.; Voultsiadou, E.; Panteris, E.; Gkelis, S. Revealing new sponge-associated cyanobacterial diversity: Novel genera and species. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2021, 155, 106991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, V.J.; Thacker, R.W.; Banks, K.; Golubic, S. Benthic cyanobacterial bloom impacts the reefs of South Florida (Broward County, USA). Coral Reefs 2005, 24, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocke, H.J.; Piltz, B.; Herz, N.; Abed, R.M.M.; Palinska, K.A.; John, U.; Haan, J.d.; de Beer, D.; Nugues, M.M. Nitrogen fixation and diversity of benthic cyanobacterial mats on coral reefs in Curaçao. Coral Reefs 2018, 37, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoulouniriana, D.; Siboni, N.; Ben-Dov, E.; Kramarsky-Winter, E.; Loya, Y.; Kushmaro, A. Pseudoscillatoria coralii gen. nov., sp. nov., a cyanobacterium associated with coral black band disease (BBD). Dis. Aquat. Org. 2009, 87, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamatta, D.; Stanić, D.; Gantar, M.; Richardson, L.L. Characterization of Roseofilum reptotaenium (Oscillatoriales, Cyanobacteria) gen. et sp. nov. isolated from Caribbean black band disease. Phycologia 2012, 51, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, H.; Isomura, N.; Sakai, K. Bloom of the cyanobacterium Moorea bouillonii on the gorgonian coral Annella reticulata in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokovikova, E.; Tikhonova, I.; Evseev, P.; Krasnopeev, A.; Khanaev, I.; Potapov, S.; Gladkikh, A.; Nebesnykh, I.; Belykh, O. Limnofasciculus baicalensis gen. et sp. nov. (Coleofasciculaceae, Coleofasciculales): A new genus of cyanobacteria isolated from sponge fouling in Lake Baikal, Russia. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, V.; Morais, J.; Castelo-Branco, R.; Pinheiro, Â.; Martins, J.; Regueiras, A.; Pereira, A.L.; Lopes, V.R.; Frazão, B.; Gomes, D.; et al. Cyanobacterial diversity held in microbial biological resource centers as a biotechnological asset: The case study of the newly established LEGE culture collection. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 1437–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, Y.; Medvezhonkova, O.; Naumova, T.; Sheveleva, N.; Lukhnev, A.; Sorokovikova, E.; Evstigneeva, T.; Timoshkin, O. Variation of sponge-inhabiting infauna with the state of health of the sponge Lubomirskia baikalensis (Pallas, 1776) in Lake Baikal. Limnology 2019, 20, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretolchina, T.; Khanaev, I.; Kravtsova, L. The diversity of hydras (Cnidaria: Hydridae) in the Baikal region. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 2, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekhanikova, I.V.; Sitnikova, T.Y.; Khanaev, I.V. Composition and distribution of macroinvertebrates associated with the sponges Lubomirskia baikalensis (Spongillida, Lubomirskiidae) during the ecological crisis in Lake Baikal. Biol. Bull. 2024, 51, 1915–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, B.A. (Ed.) Ecology of Cyanobacteria II. Their Diversity in Space and Time; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; 760p. [Google Scholar]

- Salmaso, N.; Bernabei, S.; Boscaini, A.; Capelli, C.; Cerasino, L.; Domaizon, I.; Elersek, T.; Greco, C.; Krivograd Klemenčič, A.; Tomassetti, P.; et al. Biodiversity patterns of cyanobacterial oligotypes in lakes and rivers: Results of a large-scale metabarcoding survey in the Alpine region. Hydrobiologia 2024, 851, 1035–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, H.; Waditee-Sirisattha, R. Chapter 5—Mycosporine-like amino acids as multifunctional secondary metabolites in cyanobacteria: From biochemical to application aspects. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Rahman, A., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 59, pp. 153–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, J.; Lopes, G.; Preto, M.; Vasconcelos, V.; Martins, R. Exploitation of filamentous and picoplanktonic cyanobacteria for cosmetic applications: Potential to improve skin structure and preserve dermal matrix components. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.