Abstract

The integration of oil-degrading microorganisms with phytoremediation has the potential to generate a synergistic effect in the removal of petroleum pollutants. This study analyzed the influence of two aquatic plant species (Eichhornia crassipes and Pistia stratiotes) and hydrocarbon-oxidizing bacterial strains (Rhodococcus erythropolis and Pseudomonas brenneri), as well as a microbial preparation, on the formation of bacterial consortia under oil-polluted conditions. The study assessed the losses of petroleum alkanes, the rheological properties of water, and the structure of emerging rhizospheric microbial communities by high-throughput sequencing. E. crassipes demonstrated a higher potential for stimulating the development of an oil-oxidizing microbial community. However, the introduced bacterial strains did not establish themselves within the formed microbial community, indicating the complexity of selecting compatible plant–microbe combinations for efficient bioremediation. Nevertheless, this approach remains a promising direction for enhancing the efficiency of hydrocarbon degradation in aquatic ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Oil spills and petroleum hydrocarbon pollution remain some of the most serious environmental problems today, causing significant damage to aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity [1,2]. Petroleum hydrocarbons are highly resistant to natural breakdown, can accumulate in sediments, and are toxic to organisms at different levels of the food chain [3]. For this reason, finding effective and environmentally safe methods to clean contaminated water bodies is a key priority.

One promising method is bioremediation—the use of microorganisms and plants to degrade petroleum hydrocarbons. Recently, phytoremediation has gained special attention. It relies on aquatic plants’ ability to accumulate, transform, or break down pollutants and to stimulate the activity of microorganisms around their roots [4,5,6]. The root systems of aquatic plants create unique microbial communities (rhizobiomes) rich in bacteria that can oxidize hydrocarbons [7]. Organic compounds and oxygen released by plant roots activate the metabolic pathways in these microorganisms responsible for hydrocarbon degradation [8].

Among aquatic plants, Eichhornia crassipes and Pistia stratiotes are especially interesting. These free-floating species have well-developed root systems that provide a large surface area for microbial colonization, which improves biodegradation [9,10]. Studies have shown that E. crassipes is effective for cleaning water contaminated with heavy metals, organic pollutants, and petroleum [11], while P. stratiotes shows strong potential for wastewater treatment and good tolerance to environmental changes [12].

An additional approach to enhance the efficiency of bioremediation is bioaugmentation—the introduction of specially selected strains of petroleum-degrading bacteria, such as members of the genera Rhodococcus and Pseudomonas, which are well known for their ability to oxidize a wide range of hydrocarbons [13,14,15]. Combining bioaugmentation with phytoremediation can produce a synergistic effect, accelerate the cleanup process, and increase the resilience of microbial communities to toxic stress [16].

However, the influence of different aquatic plant species on the formation of microbial communities and their role in petroleum degradation is not yet fully understood. In particular, there are limited data on the comparative roles of E. crassipes and P. stratiotes in shaping the rhizobiome structure under petroleum contamination and when used in combination with bacterial consortia.

The aim of this study was to investigate the processes of petroleum biodegradation under laboratory-simulated aquatic ecosystem conditions using two aquatic plant species (E. crassipes and P. stratiotes), hydrocarbon-oxidizing bacterial strains (R. erythropolis and P. brenneri), and the bioproduct DOP UNI (Laboratorija Mikrobnyh Tehnologij, Ltd., Moscow, Russia). Particular attention was paid to analyzing the microbial communities of the plant rhizosphere and assessing their contribution to petroleum degradation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plants

In this work, the rhizobiome of the root system of two water plants was analyzed. There were Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms (also known as Pontederia crassipes Mart. and water hyacinth) and Pistia stratiotes L. (water cabbage). Plant samples were kindly provided by the K.A. Timiryazev Institute of Plant Physiology, RAS, Moscow, Russia.

E. crassipes (water hyacinth) and P. stratiotes (water lettuce) are both free-floating perennial aquatic plants native to tropical and subtropical regions [17]. They inhabit freshwater bodies, floating on the surface through specialized anatomical adaptations. The two species exhibit the same growth form despite their distant phylogenetic relationship. In addition, they have an extensive branched root system, which promotes the development of a diverse rhizosphere microbiota and determines the phytoremediation potential of plants.

Plants were grown at the Skryabin Institute of Bioengineering (FRC “Fundamentals of Biotechnology” of the RAS) experimental climate control facility. Grow conditions followed the approach described in our previous study (Zhilkina et al., 2024) [18].

2.2. Characteristics of Oil

Crude oil from well No. 669 of the Cheremukhinskoye field (RITEK LLC, Republic of Tatarstan, Russia) was used as a source of pollution [19]. The density of oil under surface conditions is 932 kg/m3, which allows it to be classified as heavy oil. Oil viscosity under reservoir conditions is 72.6 mm2/s; water content 27.1–50.1%; reservoir temperature 20.2–21.3 °C.

2.3. Hydrocarbon-Oxidizing Bacteria Strains

The study used previously isolated pure cultures of Rhodococcus erythropolis and Pseudomonas brenneri obtained from soil samples in the coastal–littoral zone of the Kola Bay, Barents Sea [20]. The R. erythropolis strain M7-8 (GenBank accession number MW853833) was isolated from sample 7_M21 of non-flooded soil from Belokamenka settlement in the Murmansk region. The P. brenneri strain M6-6 (GenBank accession number MW853771) was obtained from sample 6_M21 of flood-prone coastal soil from the same area.

Cultures were grown in a mineral medium containing: K2HPO4 1.5 g/L, KH2PO4 0.75 g/L, NH4Cl 1.0 g/L, NaCl 20.0 g/L, KCl 0.1 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O 0.1 g/L, CaCl2·2H2O 0.02 g/L, pH 7.0. Carbon sources added to the medium included a mixture of C14-C17 n-alkanes, crude oil, or diesel fuel (0.2% v/v). Cultures were incubated at temperatures ranging from 5 to 30 °C. These bacteria can be classified as psychrotolerant microorganisms, as their maximum growth rate was observed at temperatures below 20 °C. A sodium chloride concentration of 0.5% was optimal for the growth of the selected strains. When grown on crude oil, the R. erythropolis M7-8 strain significantly reduced the surface and interfacial tension of the culture fluid, indicating the production of biosurfactants.

2.4. Characteristic of Bioaugmentation Product for Oil Degradation DOP-UNI

In order to compare the efficiency of oil biodegradation, we purchased DOP-UNI product (Laboratorija Mikrobnyh Tehnologij, Ltd., Moscow, Russia). This universal bioaugmentation product developed by LLC (Laboratory of Microbial Technologies) is designed for the biodegradation of oil and petroleum products in case of contamination of soils, water bodies, and hard surfaces with residues of petroleum products (pipes, tanks). It is a powder consisting of dry aggregates of viable cells of a specially selected consortium of microorganisms growing on hydrocarbons of different classes and some of their derivatives.

The manufacturer states that the product has 5 groups of microorganisms targeting different types of hydrocarbons; information about the strains is not disclosed. The consortium includes microorganisms of Candida, Dietzia, Rhodococcus, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter genera. The product also includes a mineral complex of nutritional supplements.

2.5. Experimental Design

For modeling the wetlands of the experiment, tanks filled with clean tap water to the same level were prepared. The volume of the tanks for plants was 100 L, while the volume of the tanks without plants was 50 L. The depth of the tanks was the same. The tanks were randomly placed in the experimental climate control facility.

The scheme of the experiment is given in Table 1. The experiment variants included tanks with ‘clean water’ and containing crude oil (o) at a concentration of 1 mL per 1 L of water. The tanks were divided into three groups: plant-free (W), with E. crassipes plants (E), and with P. stratiotes plants (P). Each group had tanks in which the performance of oil-degrading microorganisms was analyzed individually (st1 and st2) and in a consortium (mix). The performance of DOP UNI in tanks with and without plants was also studied (uni).

Table 1.

Description of experimental variants (tanks compound).

At the beginning of the experiment, six plants were placed in each tank (where provided). For the experiment, plants were selected according to morphological features in favor of the largest and brightly colored specimens. Figure 1 shows an example of tanks with plants and oil at the start of the experiment.

Figure 1.

(a) E2o tank—E. crassipes plants and crude oil; (b) P12o tank—P. stratiotes plants and crude oil.

Microorganisms were added as follows: an overnight bacterial culture was prepared and added to the tanks at a ratio of 1 mL of suspension per 1 L of water. The concentration of bacteria in the initial suspension was 1 × 106 CFU/mL. Bacterial suspensions were added to tanks with both strains (mix) at a ratio of 0.5 mL per 1 L of water. DOP UNI preparation was applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions: 1 g of dry powder per 1 L of water.

The experimental setup and general design followed the approach described in our previous study (Zhilkina et al., 2024) [18]. The experiment was conducted for 28 days, with plant abundance recorded every 14 days. Water samples for physicochemical analyses were collected on days 14 and 28.

Samples for microbial community analysis were collected at the end of the experiment (day 28). Root-associated microbiota were analyzed using pooled root material from six plants per tank, selected to account for spatial heterogeneity. In tanks without plants, microbial biomass was obtained from 100 mL of water per tank.

2.6. Analytical Methods

Chemical and physicochemical analyses were performed according to previously described protocols (Zhilkina et al., 2024) [18]. Briefly, water samples from the upper layer of each tank were collected at multiple points to ensure representative sampling.

Aliphatic hydrocarbons in water samples were quantified using gas chromatography after n-hexane extraction and fractionation on silica gel, following the approach described by Borzenkov [21].

Emulsification activity (E24) was assessed using a modified Zajic method with hexadecane [22]. Surface and interfacial tension were measured using a semi-static ring method on a Surface Tensiomat 21 tensiometer at 22 °C. All measurements were performed in three replicates per tank. Data processing and visualization were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

2.7. Analysis of Microbial Community Composition

2.7.1. DNA Isolation, 16S rRNA Gene Fragment Amplification and Sequencing

DNA extraction, amplification of the V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene, library preparation, and Illumina sequencing were performed following the protocol described in our previous study (Zhilkina et al., 2024) [18]. Overlapping paired illumina reads were merged into longer reads by FLASH v1.2.11 [23]. Sequence processing, quality filtering, chimera removal, and OTU clustering at a 97% similarity threshold were conducted using USEARCH [24] and VSEARCH [25] as described previously. Taxonomic assignment was performed using the SINTAX classifier implemented in VSEARCH v2.28.1.

The raw data generated from 16S rRNA gene sequencing were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and are available via the BioProject PRJNA1354817.

2.7.2. Data Analysis Methods

Taxonomic classification was based on the Silva v138.1 database. Taxons with significant change between different conditions were identified by calculating multiple paired t-tests in R v4.2.1 programming language on the natural logarithm of taxon relative abundance data, and p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini & Hochberg method. Changes in taxon abundances with adjusted p-value < 0.05 were considered significant. R v4.2.1 programming language functions t.test with paired = T parameter and p.adjust with method = ‘fdr’ parameter were used; zero values were replaced by half of the minimum value in the dataset for logarithm calculation.

The same R functions were used to calculate multiple paired t-tests to determine significant changes in relative oil removal efficiency between different conditions, and p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini & Hochberg method.

Weighted unifrac distances for OTU data were calculated using Usearch. Principal coordinate analysis was performed on a unifrac matrix in the R programming language by applying the cmdscale function. Constrained correspondence analysis (CCA) between OTU data and different conditions was calculated via the vegan 2.6-4 R library, and the significance of the CCA analysis was assessed by an ANOVA-like permutation test in vegan (anova.cca function).

3. Results

3.1. Rheological Changes During Oil Bioremediation

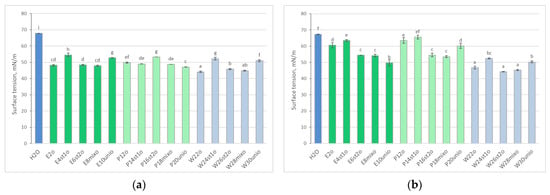

During the experiment, water samples from tanks were collected twice for analysis of rheological parameters. In samples from oil-contaminated tanks, surface tension was reduced compared to the control at the 2-week sampling point (Figure 2a). After 4 weeks, surface tension in samples with E. crassipes (E2o and E4st1o) and P. stratiotes (P12o and P14st1o) approached the values of the control sample (Figure 2b). Meanwhile, surface tension remained reduced in all plant-free tanks.

Figure 2.

Surface tension of the experimental samples after 2 (a) and 4 (b) weeks of cultivation following oil addition, compared to the control sample (tap water). Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among groups according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05.

As expected, oil addition significantly reduced interfacial tension, as shown in Figure 3. However, in tanks with P. stratiotes, interfacial tension values were higher than in other samples. This may indicate the release of root exudates by the plant that affect environmental parameters. Notably, by week 4 of cultivation, an increase in interfacial tension occurred in the tanks with the added microbial consortium (P20unio).

Figure 3.

Interfacial tension of the experimental samples after 2 (a) and 4 (b) weeks of cultivation following oil addition, compared to the control sample (tap water). Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among groups according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05.

Surface and interfacial tension were also measured in oil-free tanks’ water samples at 2 weeks of cultivation. The surface tension of the medium did not change compared to the control in all samples (Supplementary Table S1). Interfacial tension was slightly reduced, which may be related to a higher abundance of microorganisms and trace elements in the medium compared to the control (tap water).

No stable emulsion formation was observed in all oil-free tanks when water samples were mixed with hexadecane (E24 = 0). In samples from oil- and plant-containing tanks, the emulsification index was around 5% after 2 weeks from the start of the experiment (except for E4st1o). For samples from tanks without plants (W22o, W28mixo, and W30unio), the emulsification index was 10%.

3.2. Efficiency of Oil Biodegradation

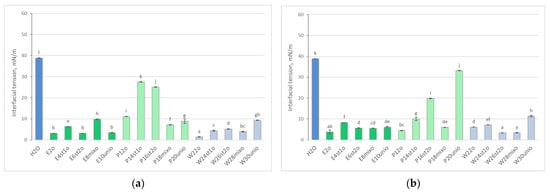

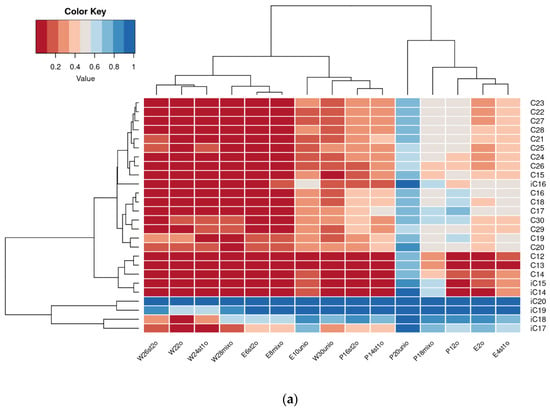

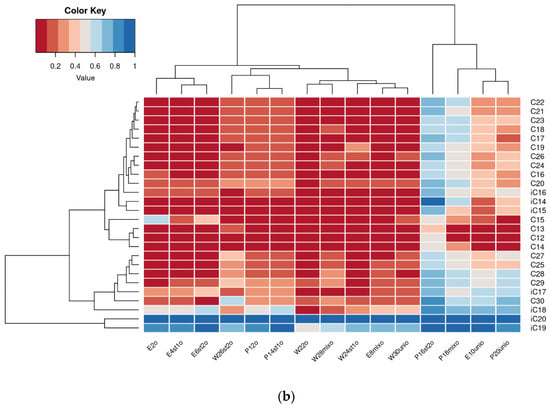

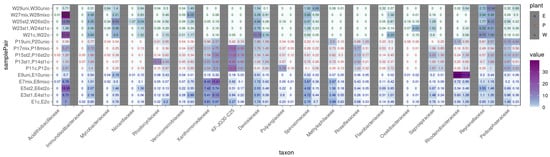

Chromatographic analysis results for residual petroleum alkane content in samples were visualized as heatmaps (Figure 4). To identify significant changes in residual alkane levels, multiple pairwise t-tests were performed (see Section 2.7.2), with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. The p-values are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of residual content of alkanes in degraded crude oil after 2 (a) and 4 (b) weeks of cultivation.

In the second week of cultivation, the highest alkane removal was observed in plant-free samples (W22o, W24st1o, and W26st2o). In tanks with plants, oil degradation was less efficient; however, among these, the highest rates occurred in E. crassipes samples inoculated with petroleum-degrading microbial strains (E6st2o, E8mixo).

By the fourth week of cultivation, the residual alkane content in reservoirs with E. crassipes and petroleum-degrading strains approached that in plant-free samples (except E10unio). P. stratiotes treatments showed consistently low removal efficiency, with the highest rates in the uninoculated reservoir (P12o) and the one inoculated with P. brenneri M6-6 (P14st1o). Notably, DOP UNI showed low oil removal efficiency in the presence of both plant species (E10unio and P20unio).

Differences in tank volume (50 L vs. 100 L) may affect oil degradation through surface-to-volume ratio variations, potentially enhancing initial mass transfer in smaller tanks. However, the observed pattern in our results mirrors our previous work (Zhilkina et al., 2024) [18] with uniform 100 L tanks, where plant-free treatments also outperformed in biodegradation rate, indicating that volume was not the primary factor.

3.3. Microbial Community Analysis

3.3.1. Alpha and Beta Diversity Analysis

Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene fragments revealed that the proportion of Bacteria in all analyzed samples exceeded 99%, while Archaea accounted for less than 1%. The analysis of alpha diversity across samples enabled the identification of patterns in microbial richness under different experimental conditions. Comprehensive alpha-diversity data are provided in the Supplementary (Table S3).

Tanks without plants exhibited lower species diversity compared to those containing E. crassipes and P. stratiotes. In these samples, the Chao1 richness estimator ranged from 96.4 to 143.4, the Shannon index from 1.24 to 1.63, and the Simpson index from 0.04 to 0.18. Notably low diversity was also observed for tanks with the UNI for both plant species, with Chao1 values of 176.7 for E9uni and 241.2 for P19uni. Significant variations were detected under the influence of oil: Chao1 values were 162.3 for E10unio and 409.1 for P20unio.

The presence of P. stratiotes generally had a positive effect on microbiome diversity, regardless of oil contamination. Except for P19uni, tanks with this plant displayed the highest values for the assessed diversity indices: Chao1 ranged from 393.8 to 445.3. The introduction of E. crassipes similarly enhanced microbial community diversity. However, in tanks containing both oil and E. crassipes, microbial richness was reduced—a trend observed exclusively in tanks with E. crassipes.

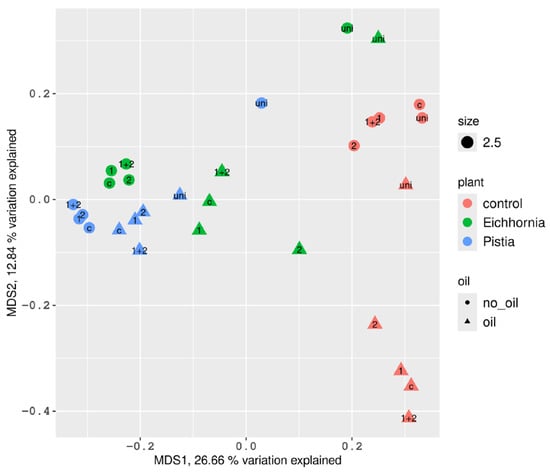

MDS analysis based on weighted Unifrac distances demonstrated the compositional similarity of microbial communities between the two investigated plant species (Figure 5). However, samples from the UNI group were notably separated from the main cluster. A similar pattern was observed in plant-free controls, where the W30unio sample was clearly distinct from other oil-contaminated samples. At the same time, tanks without plants and oil formed a group characterized by similar species diversity, divided from oil-exposed plant-free tanks.

Figure 5.

Principal coordinate analysis of microbial communities associated with different aquatic plants based on β-diversity (weighted Unifrac distance matrix). 1 is P. brenneri M6-6, 2 is R. erythropolis M7-8, 1 + 2 is a mix of P. brenneri M6-6 and R. erythropolis M7-8, uni is DOP UNI bioaugmentation.

3.3.2. Analysis of Microbial Communities

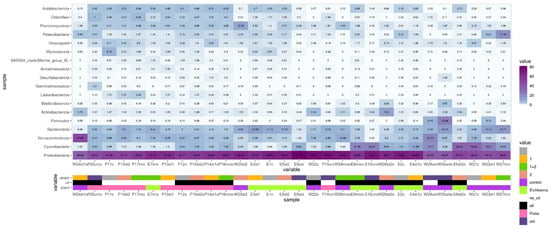

High-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA gene fragments identified 18 phyla with relative abundances exceeding 1% in the analyzed samples (Figure 6). Proteobacteria constituted a substantial fraction in all samples, averaging 58%. In all tanks containing plants, except for P19uni, the dominant class was Gammaproteobacteria, accounting for 55–73% of the Proteobacteria present. In tanks without plants (W21c, W23st1, W25st2, and W27mix), Alphaproteobacteria predominated. The sample W24st1o also exhibited a high proportion of Verrucomicrobiota representatives (47.6%).

Figure 6.

Heatmap of bacterial phylum representation in microbial communities of the studied samples based on 16S rRNA gene fragment analysis. 1 is P. brenneri M6-6, 2 is R. erythropolis M7-8, 1 + 2 is a mix of P. brenneri M6-6 and R. erythropolis M7-8, uni is DOP UNI bioaugmentation.

Other phyla with significant representation across the samples included Cyanobacteria, Verrucomicrobiota, Actinobacteriota, Firmicutes, and Patescibacteria. Notably, high proportions of Cyanobacteria were not observed in tanks with P. stratiotes. In contrast, the phylum Acidobacteriota was predominantly detected in tanks containing this plant, as well as those with E. crassipes. Actinobacteriota were primarily present in oil-exposed tanks without plants, with relative abundances of 6.2% in W22o, 5.8% in W24st1o, 13.2% in W26st2o, and 3.1% in W28mixo.

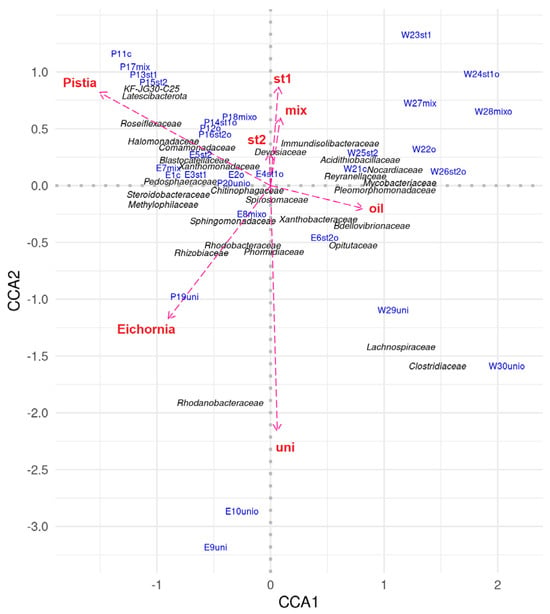

Canonical-correlation analysis of the microbial community at the family level allowed identification of taxa associated with various cultivation conditions: presence or absence of oil, presence or absence of aquatic plants, and introduction of microorganisms and consortia (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Results of canonical correlation analysis of the microbial community.

Notably, there were pronounced differences in the composition of microbial communities in tanks with DOP UNI. Significant variation was observed both among tanks with this bioaugmentation and between this group of tanks and all other experimental variants.

The addition of oil had little effect on the composition and diversity of the microbiome in the presence of E. crassipes (variants E9uni and E10unio). These communities were dominated by representatives of the families Rhodanobacteraceae (39.8% and 32.3%), Phormidiaceae (8.3% and 21.8%), Sphingomonadaceae (8.8% and 10.2%), and Rhodobacteraceae (5.7% and 6.8%). These groups include both aerobic organotrophs and phototrophic cyanobacteria, indicating a stable community with the potential for both hydrocarbon biodegradation (Sphingomonadaceae, Rhodanobacteraceae) and primary production (Phormidiaceae) [26]. Representatives of Xanthobacteraceae, Rhizobiaceae, and Comamonadaceae (2–5%) were also detected, associated with the decomposition of organic substrates and nitrogen fixation [27].

In contrast, reservoirs with P. stratiotes (P19uni) were dominated by Rhizobiaceae (33.6%) and Chitinophagaceae (7.3%), known as plant symbionts and degraders of chitin and polysaccharides, respectively [28]. Both Pistia variants (P19uni, P20unio) also contained Pedosphaeraceae and Phormidiaceae (~5%). In P20unio, no single family dominated; ten families were present in roughly equal proportions (2–5%). Notably, only in this reservoir was the bacterium Gemmatimonadetes SCN 70-22 (phylum Gemmatimonadota), capable of anoxygenic photosynthesis, detected [29].

In the W29uni reservoir and the control W21c, Opitutaceae representatives dominated, typical for tap water systems [30]. In W29uni, this group accounted for up to 20% of the microbiome. Other significant taxa included Phormidiaceae (16.2%), Xanthobacteraceae (6.9%), and Lachnospiraceae (6.1%). Clostridiaceae dominated in W30unio (16.8%), likely related to the decomposition of cyanobacterial biomass along with Lachnospiraceae (3.4%) [31]. These two families were exclusive to W29uni and W30unio. The same reservoir also contained Reyranellaceae (10.4%), Pleomorphomonadaceae (8.5%), the marine NS11-12 group, and Bdellovibrionaceae, known as predatory bacteria [31,32].

In the following results, less attention will be given to samples containing UNI, as the emphasis shifts toward other bioaugmentation variants.

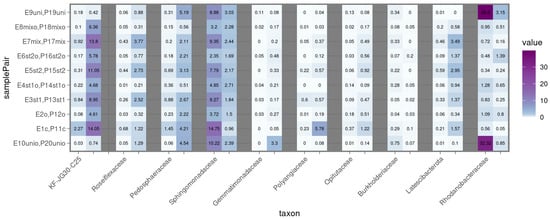

Figure 8 presents families for which clear associations were observed when comparing tanks that differed only in the presence or absence of oil contamination. These families are grouped into three categories: tanks with E. crassipes, tanks with P. stratiotes, and tanks without plants.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of oil-associated bacterial family representation in microbial communities of the studied samples based on 16S rRNA gene fragment analysis. 1 is P. brenneri M6-6, 2 is R. erythropolis M7-8, 1 + 2 is a mix is a mix of P. brenneri M6-6 and R. erythropolis M7-8, uni is DOP UNI bioaugmentation. Only taxons with a significant adjusted p-value < 0.05 of the paired t-test are displayed.

In most tanks containing oil, the family Acidithiobacillaceae was detected. Moreover, the relative abundance of this family was higher in tanks with E. crassipes than in those with P. stratiotes. The highest abundances were found in tanks W22o (25.8%) and W28mixo (38.9%), which also exhibited high oil removal efficiency. Notably, in the absence of oil, members of Acidithiobacillaceae were not detected. A similar pattern was observed for the family Immunodisolibacteraceae, suggesting a contribution of these families to oil biodegradation [33].

The family Xanthomonadaceae was found only in tanks with either of the two plant species. Importantly, the proportion of this family increased in samples containing oil. Conversely, the Reyranellaceae family showed higher relative abundances in plant-free tanks, both with and without oil contamination. The families Mycobacteriaceae and Verrucomicrobiaceae were also associated with tanks without plants but containing oil, consistent with the known role of Mycobacterium in the biodegradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [34]. The introduced strain Rhodococcus erythropolis M7-8 (Nocardiaceae) was detected in a number of samples (E6st2o—1.4%, W22o—1.3%, W24st1o—1.2%, W25st2—1.1%, and W26st2o—3%). Despite the known ability of the genus Rhodococcus to degrade oil, its proportion remained relatively low, indicating weak competitiveness in complex consortia [35]. Meanwhile, representatives of the family Pseudomonadaceae (st1 P. brenneri M6-6) were not detected above 1% in any of the samples.

Regarding the influence of plants on the microbiome composition, in addition to the families mentioned above, the family Methylophilaceae was more prominently present in tanks with E. crassipes. Additionally, the families Spirosomaceae and Devosiaceae were detected exclusively in tanks containing water and E. crassipes without oil contamination.

Plants also had a noticeable effect on the structure of microbial communities (Figure 9). In reservoirs with E. crassipes, the relative abundance of Methylophilaceae, which specialize in utilizing methanol and methylamines, was higher [36]. The families Spirosomaceae and Devosiaceae were found exclusively in oil-free reservoirs with E. crassipes. Communities with P. stratiotes were characterized by Latescibacterota, Pedosphaeraceae, Roseiflexaceae, and KF-JG30-C25, with the latter group present in significant amounts in both samples with and without oil, indicating broad ecological versatility.

Figure 9.

Heatmap of plant-associated bacterial family representation in microbial communities of the studied samples based on 16S rRNA gene fragment analysis. 1 is P. brenneri M6-6, 2 is R. erythropolis M7-8, 1 + 2 is a mix of P. brenneri M6-6 and R. erythropolis M7-8, uni is DOP UNI bioaugmentation. Only taxons with a significant adjusted p-value < 0.05 of the paired t-test are displayed.

4. Discussion

The conducted study demonstrated that the efficiency of petroleum biodegradation and the dynamics of microbial communities depend on the combination of aquatic plants, petroleum-degrading bacterial strains, and bioaugmentation agents. Analysis of physicochemical parameters of the environment showed a significant effect from the presence of E. crassipes and P. stratiotes in the system, which can be explained by the release of organic acids and polysaccharides by root exudates capable of altering the physicochemical characteristics of the environment and/or stimulating the activity of petroleum degraders [7,8]. P. stratiotes notably influenced the interfacial tension, consistent with its known ability to release biologically active compounds into the rhizosphere [10].

Chromatographic analysis revealed that at an early stage (2 weeks), the highest rate of alkane degradation was observed in systems without plants but inoculated with Rhodococcus erythropolis and Pseudomonas brenneri strains. These microorganisms are well known as effective petroleum degraders with broad metabolic capabilities [20,35,37]. However, by the fourth week, the degradation efficiency in setups with E. crassipes approached that of plant-free systems, indicating the formation of a stable plant–microbe consortium. Similar effects have been previously observed when combining phytoremediation and bioaugmentation, where plants create favorable conditions for the establishment of petroleum degraders. Meanwhile, P. stratiotes showed lower efficiency in oil removal despite higher microbial diversity [38]. Its exudates likely stimulate the growth of saprotrophic and phototrophic bacteria not directly involved in hydrocarbon degradation [39]. This result may confirm that high species diversity does not necessarily equate to functional efficiency of the microbial community.

Metagenomic analysis revealed clear differences in community structure: in the presence of plants, Gammaproteobacteria dominated, including families Rhodanobacteraceae, Sphingomonadaceae, and Xanthomonadaceae, associated with aromatic hydrocarbon degradation [40]. In plant-free variants, Alphaproteobacteria and Verrucomicrobiota predominated, which are not specialized in oil degradation. Interestingly, in E. crassipes variants, an increase in Acidithiobacillaceae and Immunodisolibacteraceae correlated with high degradation levels, consistent with their known roles in oxidizing hydrocarbons and sulfur-containing compounds [10]. Meanwhile, P. stratiotes was linked to Acidobacteriota and Pedosphaeraceae, indicating its influence on forming communities with broader ecological amplitude but lower specialization in petroleum degradation [18]. While our metagenomic data show correlations between E. crassipes presence and increased abundance of known petroleum-degrading taxa, we acknowledge this represents compositional rather than functional evidence, lacking direct quantification of degradation genes or enzyme activities. Future studies incorporating metagenomics with functional assays (e.g., gene expression profiling or substrate-specific degradation rates normalized to microbial biomass) would be needed to establish causality.

The effectiveness of the introduced strains was mixed: R. erythropolis and P. brenneri provided a rapid start to aliphatic hydrocarbon degradation, but their presence in the developed communities was small. The low abundance of the Nocardiaceae family confirms that the long-term establishment of artificially introduced strains in complex microbial consortia is limited [41,42]. The commercial product DOP UNI was least effective in the presence of plants, likely due to competition with native rhizospheric communities. Similar results have been reported in other studies where industrial bioproducts showed high in vitro activity but limited effectiveness in complex ecosystems [43].

These findings suggest plant–microbe combinations yield more stable, long-term remediation than microbes or bioproducts alone. E. crassipes proved superior by fostering petroleum-degrading taxa in its rhizobiome, while P. stratiotes exhibited lower hydrocarbon removal despite enhanced diversity. Plant species selection, based on physiology and specific rhizobiome formation, thus emerges as critical for effective aquatic oil remediation technologies.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that the efficiency of petroleum hydrocarbon biodegradation in model aquatic ecosystems is shaped by the combined action of aquatic plants, introduced hydrocarbon-oxidizing microorganisms, and bioaugmentation products. Among the plant species examined, E. crassipes was associated with the formation of microbial communities enriched in taxa commonly linked to hydrocarbon degradation, whereas P. stratiotes primarily promoted higher overall microbial diversity without a corresponding increase in oil removal efficiency. Similar trends have been reported in previous studies, indicating that enhanced microbial richness alone does not necessarily result in more effective biodegradation processes [7,38,39].

The introduction of R. erythropolis and P. brenneri facilitated a rapid initial phase of alkane degradation, in agreement with the well-established metabolic versatility of these genera in hydrocarbon oxidation [13,14,15,35,37]. However, their consistently low relative abundance in the mature microbial communities suggests limited long-term competitiveness under complex rhizospheric conditions. This observation is consistent with earlier reports showing that artificially introduced strains often persist only transiently unless supported by favorable ecological interactions or niche availability [41,42]. The commercial bioaugmentation product DOP UNI showed the lowest remediation efficiency in plant-containing systems, most likely due to competition with indigenous rhizospheric microbiota, a constraint that has also been noted for non-specific microbial formulations in other studies [16,43]. These findings highlight the challenges of applying commercial consortia in plant–microbe interactions, though efficacy may vary in plant-free conditions or different environmental contexts.

5.1. Practical Implications for Field-Scale Remediation

From an applied perspective, the results indicate that combined phytoremediation–microbial strategies have clear potential for use in oil-contaminated aquatic environments, particularly in shallow water bodies, wetlands, and systems with limited water exchange. Free-floating macrophytes such as E. crassipes may function as ecosystem engineers, indirectly facilitating hydrocarbon degradation by creating physicochemical and biological conditions favorable for indigenous degraders. These effects may include alterations of surface and interfacial tension, increased hydrocarbon bioavailability, and the establishment of stable rhizospheric microbial consortia [6,7,8,18]. Such approaches are especially attractive for environmentally sensitive sites where intrusive mechanical or chemical remediation methods are impractical or undesirable [1,2,3].

At the same time, the study highlights several constraints relevant to field application. The limited persistence of introduced bacterial strains suggests that bioaugmentation alone is unlikely to ensure sustained remediation unless the introduced microorganisms are ecologically compatible with native communities and plant-associated niches [16,41]. In addition, the reduced performance of a universal commercial bioproduct in the presence of plants underscores that non-specific microbial consortia may be ineffective in biologically structured systems, where native microbial communities exert strong competitive pressure [43].

5.2. Directions for Future Optimization

Further development of combined remediation technologies should prioritize the selection of plant species that support functionally specialized hydrocarbon-degrading microbiomes rather than maximizing overall microbial diversity. Greater emphasis should also be placed on the use of indigenous or pre-adapted microbial consortia instead of single introduced strains, as well as on coupling phytoremediation with targeted biostimulation approaches rather than broad-spectrum bioaugmentation [7,16,40]. Long-term field-scale investigations are required to assess system stability, seasonal variability, and potential ecological risks, including uncontrolled plant proliferation or secondary contamination. Taken together, the results support the view that integrated phytoremediation–microbial strategies represent a promising, environmentally sound, and scalable option for mitigating oil pollution in aquatic ecosystems, provided that their implementation is guided by ecological principles and site-specific conditions rather than solely by laboratory performance indicators [1,5,18].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18020061/s1, Table S1: Surface and interfacial tension of the experimental samples after 2 weeks of cultivation in samples from tanks without oil addition; Table S2: Results of multiple pairwise t-tests; Table S3: Alpha diversity indices of samples based on 16S RNA sequencing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z. and A.K.; methodology, T.B. and A.K.; experiments, T.Z. and I.G.; rheology and oil biodegradation analysis of samples, T.B. and T.Z.; metagenomic data curation, I.G., A.B. and V.K.; visualization, A.B. and T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.Z. and V.K.; writing—review and editing, T.B. and A.K.; supervision and project administration, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in [NCBI] at [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/?term=PRJNA1354817, accessed on 30 October 2025], reference number [PRJNA1354817].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Atlas, R.M.; Hazen, T.C. Oil Biodegradation and Bioremediation: A Tale of the Two Worst Spills in U.S. History. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6709–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, R.C. Oil Spill Dispersants: Boon or Bane? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6376–6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, I.M.; Jones, D.M.; Röling, W.F.M. Marine Microorganisms Make a Meal of Oil. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (Ed.) Terrestrial Ecosystems and Biodiversity, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilon-Smits, E. Phytoremediation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Ponraj, M.; Talaiekhozani, A.; Mohamad, S.E.; Md Din, M.F.; Taib, S.M.; Sabbagh, F.; Sairan, F.M. Perspectives of Phytoremediation Using Water Hyacinth for Removal of Heavy Metals, Organic and Inorganic Pollutants in Wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 163, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, I.; Lagendijk, E.L.; Bloemberg, G.V.; Lugtenberg, B.J.J. Rhizoremediation: A Beneficial Plant-Microbe Interaction. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004, 17, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, S.L. Enhancing Phytoremediation through the Use of Transgenics and Endophytes. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A. Environmental Challenge Vis a Vis Opportunity: The Case of Water Hyacinth. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khilji, S.A.; Tariq, R.; Aziz, I.; Munir, N.; Javed, A.; Uppal, T.; Abideen, Z.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; Keblawy, A.E. Phytoremediation Potential and Ecophysiological Responses of Pistia stratiotes L. for Removal of Cadmium and Lead from Polluted Water: A Viable Option for Agricultural Resilience. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 8, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.L.; Quek, Y.Y.; Lim, S.; Shuit, S.H. Review on Phytoremediation Potential of Floating Aquatic Plants for Heavy Metals: A Promising Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Thakur, N.; Singh, A.K.; Gudade, B.A.; Ghimire, D.; Das, S. Aquatic Macrophytes for Environmental Pollution Control. In Phytoremediation Technology for the Removal of Heavy Metals and Other Contaminants from Soil and Water; Elsevier: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbunova, T.I.; Egorova, D.O.; Pervova, M.G.; Kir’yanova, T.D.; Plotnikova, E.G. Degradability of Commercial Mixtures of Polychlorobiphenyls by Three Rhodococcus Strains. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xiu, J.; Yu, L.; Huang, L.; Yi, L.; Ma, Y. Degradation of Crude Oil in a Co-Culture System of Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1132831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Das, A.; Das, S.; Bhatawadekar, V.; Pandey, P.; Choure, K.; Damare, S.; Pandey, P. Petroleum Hydrocarbon Catabolic Pathways as Targets for Metabolic Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Bioremediation of Crude-Oil-Contaminated Environments. Fermentation 2023, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muter, O. Current Trends in Bioaugmentation Tools for Bioremediation: A Critical Review of Advances and Knowledge Gaps. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet. 2025. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Zhilkina, T.; Gerasimova, I.; Babich, T.; Kanapatskiy, T.; Sokolova, D.; Kadnikov, V.; Kamionskaya, A. Evaluation of the Phytoremediation Potential of Aquatic Plants and Associated Microorganisms for the Cleaning of Aquatic Ecosystems from Oil Products. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazina, T.N.; Sokolova, D.S.; Babich, T.L.; Semenova, E.M.; Ershov, A.P.; Bidzhieva, S.K.; Borzenkov, I.A.; Poltaraus, A.B.; Khisametdinov, M.R.; Tourova, T.P. Microorganisms of Low-Temperature Heavy Oil Reservoirs (Russia) and Their Possible Application for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Microbiology 2017, 86, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.M.; Babich, T.L.; Sokolova, D.S.; Ershov, A.P.; Raievska, Y.I.; Bidzhieva, S.K.; Stepanov, A.L.; Korneykova, M.V.; Myazin, V.A.; Nazina, T.N. Microbial Communities of Seawater and Coastal Soil of Russian Arctic Region and Their Potential for Bioremediation from Hydrocarbon Pollutants. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzenkov, I.A.; Milekhina, E.I.; Gotoeva, M.T.; Rozanova, E.P.; Belyaev, S.S. The Properties of Hydrocarbon-Oxidizing Bacteria Isolated from the Oilfields of Tatarstan, Western Siberia, and Vietnam. Microbiology 2006, 75, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajic, J.E.; Guignard, H.; Gerson, D.F. Emulsifying and Surface Active Agents from Corynebacterium hydrocarboclastus. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1977, 19, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast Length Adjustment of Short Reads to Improve Genome Assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. Search and Clustering Orders of Magnitude Faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2460–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A Versatile Open Source Tool for Metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 2016, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazaimeh, M.D.; Ahmed, E.S. Bioremediation Perspectives and Progress in Petroleum Pollution in the Marine Environment: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54238–54259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, H.; Hosokawa, R.; Morikawa, M.; Okuyama, H. A Turbine Oil-Degrading Bacterial Consortium from Soils of Oil Fields and Its Characteristics. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2008, 61, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzuay, M.S.; Viso, N.P.; Ludueña, L.M.; Morla, F.D.; Angelini, J.G.; Taurian, T. Plant Beneficial Rhizobacteria Community Structure Changes through Developmental Stages of Peanut and Maize. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Feng, F.; Medová, H.; Dean, J.; Koblížek, M. Functional Type 2 Photosynthetic Reaction Centers Found in the Rare Bacterial Phylum Gemmatimonadetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7795–7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, R.J.; Jones, S.E.; Eiler, A.; McMahon, K.D.; Bertilsson, S. A Guide to the Natural History of Freshwater Lake Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 14–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Cao, X.; Huang, R.; Zeng, J.; Wu, Q.L. Variation of Bacterial Communities in Water and Sediments during the Decomposition of Microcystis Biomass. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockett, R.E.; Lambert, C. Bdellovibrio as Therapeutic Agents: A Predatory Renaissance? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Ke, W.J.; Sun, X.B.; Liu, J.F.; Gu, J.D.; Mu, B.Z. Comparison of Bacterial Community in Aqueous and Oil Phases of Water-Flooded Petroleum Reservoirs Using Pyrosequencing and Clone Library Approaches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 4209–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessee, C.T.; Li, Q.X. Effects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Mixtures on Degradation, Gene Expression, and Metabolite Production in Four Mycobacterium Species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 3357–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínková, L.; Uhnáková, B.; Pátek, M.; Nešvera, J.; Křen, V. Biodegradation Potential of the Genus Rhodococcus. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhnaya, M.G.; Bowerman, S.; Lara, J.C.; Lidstrom, M.E.; Chistoserdova, L. Methylotenera mobilis Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., an Obligately Methelamine-Utilizing Bacterium within the Family Methylophilaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 2819–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants: An Overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 941810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, M.; da Fonseca, M.M.R.; de Carvalho, C.C.C.R. Bioaugmentation and Biostimulation Strategies to Improve the Effectiveness of Bioremediation Processes. Biodegradation 2011, 22, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Taib, S.M.; Md Din, M.F.; Dahalan, F.A.; Kamyab, H. Comprehensive Review on Phytotechnology: Heavy Metals Removal by Diverse Aquatic Plants Species from Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 318, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacwa-Płociniczak, M.; Biniecka, P.; Bondarczuk, K.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Metagenomic Functional Profiling Reveals Differences in Bacterial Composition and Function During Bioaugmentation of Aged Petroleum-Contaminated Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zuo, Y.; Hou, Z.; Wang, B.; Xiong, S.; Ding, X.; Peng, B.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; et al. Effect of Rhodococcus Bioaugmentation and Biostimulation on Dibenzothiophene Biodegradation and Bacterial Community Interaction in Petroleum-Contaminated Soils. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1270599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dealtry, S.; Ghizelini, A.M.; Mendonça-Hagler, L.C.S.; Chaloub, R.M.; Reinert, F.; de Campos, T.M.P.; Gomes, N.C.M.; Smalla, K. Petroleum Contamination and Bioaugmentation in Bacterial Rhizosphere Communities from Avicennia schaueriana. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 757–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romantschuk, M.; Lahti-Leikas, K.; Kontro, M.; Galitskaya, P.; Talvenmäki, H.; Simpanen, S.; Allen, J.A.; Sinkkonen, A. Bioremediation of Contaminated Soil and Groundwater by in Situ Biostimulation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1258148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.