Abstract

Human schistosomiasis is a neglected tropical disease caused by six Schistosoma species, the most widespread of which is S. mansoni. Despite its high prevalence in Africa, molecular data on the parasite remain scarce in many regions, including the Republic of Guinea. This study presents the first molecular characterization of S. mansoni from naturally infected Biomphalaria pfeifferi snails in Guinea. Eight cox1 and four nd5 mitochondrial gene fragments, 353–425 bp and 259–271 bp in length, respectively, were sequenced. A new cox1 haplotype of S. mansoni was identified in this study. High genetic diversity was observed in our samples for both cox1 (Hd = 0.75) and nd5 (Hd = 0.84). Phylogeographic analysis revealed that the dominant Guinean cox1 haplotypes are shared with other West African populations, and that one haplotype is globally dispersed, linking West Africa to South America and the Middle East. Phylogenetic reconstructions confirmed the divergence between West and Southeast African populations and supported the hypothesis of a Southeast African origin for S. mansoni, with a subsequent expansion to West Africa and the New World. These results highlight the importance of expanding molecular surveillance to improve our understanding of the spread and population structure of this human pathogen.

1. Introduction

Trematodes of the genus Schistosoma (Weinland, 1858), known as blood flukes, are the causative agents of human schistosomiasis. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers this disease to be one of the most serious neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) [1]. Infection occurs when the free-living cercariae, generated asexually in the mollusks, penetrate the skin when humans are exposed to water with the infective stage. The adult trematodes then parasitize the blood capillaries of the intestinal and urogenital systems, disrupting their function. Species S. mansoni Sambon, 1907 is the most common cause of intestinal schistosomiasis [2].

Approximately 93% of schistosomiasis cases occur in Africa [3], with a significant increase in the infection rate in recent decades [4]. Migrations from Africa to Eurasia, climate change, and the potential for schistosome intermediate hosts (snails) to colonize new areas all increase the risk of the pathogen expanding its geographical range. For example, cases of human schistosomiasis have been reported in Spain, Portugal, and France, even among patients who had never travelled to regions where schistosomes are endemic [5].

Furthermore, human schistosome species can parasitize other mammals [6], meaning that animal reservoirs can independently maintain the parasite’s circulation in nature, irrespective of human involvement. Therefore, detecting and treating the infection in humans alone is insufficient to control the spread of schistosomiasis. It is also necessary to monitor the presence of parasites in the environment in both water bodies and snails.

Trematodes of the genus Schistosoma are of great medical importance and have consequently been the subject of numerous studies in various fields, including morphology, biology, ecology, genomics, transcriptomics, and PCR diagnostics [7,8,9]. However, more data on the morphological, ecological and molecular genetic characteristics of these parasites from various habitats are needed, given the diversity of climatic conditions in the regions where these helminths are found, the variability of their mollusk hosts, the possible inclusion of various definitive and intermediate, reservoir and accidental hosts in the parasitic systems of ‘human’ schistosomes in different areas [6], as well as the emergence of interspecific hybrids [10,11,12].

Two species of Schistosoma that are pathogenic to humans are currently known to be present among people in the Republic of Guinea: S. mansoni and S. haematobium (Bilharz, 1852) [6]. According to an analysis of human surveys conducted between 1989 and 2019, the average prevalence of S. mansoni infection in different regions of Guinea ranges from 1 to 15% [13]. In some areas, such as Forest Guinea, the prevalence of S. mansoni infection among schoolchildren has reached 86% [14]. However, no data are available on the infection of snails with these trematodes in the region. Information on the occurrence of these parasites in mollusks in Guinea is based solely on human surveys and the confirmed presence of their main intermediate hosts, the mollusks Biomphalaria pfeifferi (Krauss, 1848) and Bulinus globosus (Morelet, 1866) [15]. Furthermore, the only available molecular genetic data on S. mansoni, most likely originating from this country, comprise 12 sequences of the mtDNA cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) gene obtained from trematode eggs in the feces of a patient who had migrated from Guinea to Spain [16].

At the same time, molecular genetic data are important for correctly identifying Schistosoma species and detecting their potential interspecific hybrids, as well as analyzing parasite distribution patterns. Mitochondrial genes are well suited to these purposes and can be used as genetic markers to differentiate between Schistosoma species [12], as well as to reconstruct phylogenetic relationships within the genus and with closely related taxa [17]. Due to their maternal inheritance and relatively high mutation rate compared to nuclear DNA, mtDNA genes can be used to track the origin, dispersal patterns, and genetic diversity of these parasites on both global and local scales [10,18,19,20,21,22]. However, most phylogeographic studies of S. mansoni are based on the analysis of the cox1 gene sequences, with only one study conducted using the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 (nd5) gene of mtDNA sequences obtained from Malawi, Africa [23].

This study aims to obtain the first data on the mitochondrial gene sequences of S. mansoni from naturally infected snails in water bodies in the Republic of Guinea and to analyze the genetic diversity, phylogeographic relationships, and phylogeny of the parasite populations in this region of Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

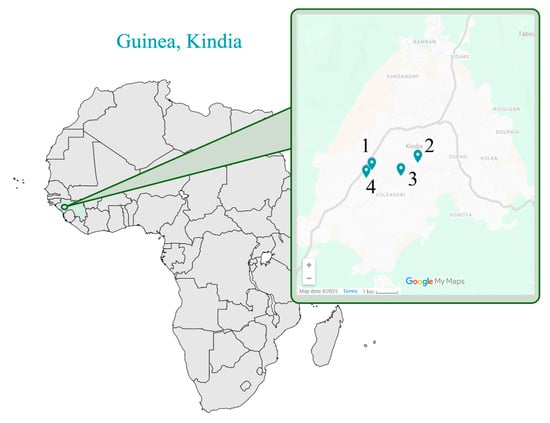

Cercariae and sporocysts of the trematode S. mansoni were obtained from 10 naturally infected specimens of B. pfeifferi (Table 1). Mollusk samples were collected between 28 October and 1 November 2024 at four locations (Figure 1) in three isolated water bodies in Kindia, the Republic of Guinea. The mollusks were delivered alive to the laboratory of the Centre for Marine and Coastal Research of Guinea (Conakry), placed individually into pots of fresh water, and exposed to light to stimulate cercarial shedding from any infected snails. The cercariae shed by the mollusks were examined under a stereo microscope. Those that were morphologically consistent with representatives of the genus Schistosoma were placed individually into Eppendorf tubes and fixed in 96% ethanol for subsequent molecular genetic analysis. Infected mollusks were euthanized in accordance with the AVMA’s recommendations for the euthanasia of animals [24]. The snails were first anesthetized by immersion in a magnesium chloride solution (50 g/L) until they ceased to move completely. Then, ethanol was gradually added, after which the mollusks were rapidly and thoroughly destroyed. The mature sporocysts found inside the mollusks (in the hepatopancreas region), along with a small amount of host tissue, were carefully removed and fixed in 96% ethanol for subsequent molecular genetic analysis.

Table 1.

Characterization of the samples of S. mansoni infected with B. pfeifferi in Guinea, GenBank accession numbers, and lengths of obtained sequences.

Figure 1.

Sampling localities (map data © 2025 Google). Keys: 1–4—numbers of the sites according to Table 1.

Further information on the characteristics of the samples, the prevalence of infection, and the morphology of the mollusks and cercariae can be found in publication [25].

Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs) was calculated to analyze the relationship between the number of detected haplotypes and haplotype diversity, and the number of sequences included in the analysis, for cases where there were at least five sequences. The significance level was taken as p ≤ 0.05.

2.2. DNA Isolation, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from one specimen of S. mansoni (either cercaria or sporocyst) from each mollusk with the QIAamp® Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Venlo, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The elution volume was reduced to 50 μL. The concentration of the isolated DNA was measured using a Qubit 4.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The DNA extracts were stored at −20 °C.

Amplification of the cox1 mtDNA fragment was performed with the PCR primers CO1800F (5′-CATCATATGTTTATGGTTGG-3′) and Cox1_schist_3k (5′-TAATGCATMGGAAAAAAACA-3′) [17] under the following conditions: initial denaturing at 94 °C for 2 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Reactions were carried out in a total volume of 25 μL containing ~1 ng of total genomic DNA, 0.25 µL PhusionTM Plus Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM dNTP, and 0.4 mM of each primer.

The nd5 mtDNA fragment was amplified with the PCR primers ND5-F (5′-ATT AGA GGC AAT GCG TGC TC-3′) and ND5-R (5′-ATT GAA CCA ACC CCA AAT CA-3′) [23] under the following conditions: initial denaturing at 94 °C for 5 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 58 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. Reactions were carried out in a total volume of 25 μL containing ~1 ng of total genomic DNA, 5x Screen Mix (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia), 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.4 mM of each primer.

All PCR products were detected on 1% agarose gels. The Sanger reaction mix was prepared using a BigDyeTM Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit 4336917 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer. Sequencing was performed using a Nanophor-05 genetic analyzer (IAI RAS, St. Petersburg, Russia).

2.3. Genetic Diversity, Phylogeographic and Phylogenetic Analysis

All obtained nucleotide sequences, which were sequenced in both directions, were aligned in BioEdit [26] using reference sequences of S. mansoni from GenBank (accession numbers MN593404 and NC_002545 for cox1 and nd5, respectively). The alignment was then refined manually; then, the final sequences were submitted to the NCBI database. A multiple sequence alignment with sequences available in the NCBI database was conducted for the haplotype network and phylogenetic analysis using the CLUSTAL W algorithm within the Unipro UGENE 52.0 software [27,28].

Nucleotide diversity (π), the number of haplotypes (h), and haplotype diversity (Hd) were calculated for the obtained partial cox1 and nd5 gene sequences of S. mansoni using DnaSP 6 software [29]. For comparison, these genetic diversity indices were calculated for similar gene regions using sequences retrieved from the GenBank database. The corresponding accession numbers and sampling localities are provided in Table 1 (for newly generated sequences) and Supplementary Table S1 (for sequences obtained from GenBank) [10,12,16,18,20,22,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42].

Haplotype networks were constructed separately for the cox1 gene (320 sequences) and the nd5 gene (27 sequences) of S. mansoni. The analysis included sequences obtained in this study, as well as those retrieved from the GenBank database (Table S1). The networks were built using the TCS method [43] implemented in PopArt 1.7 software [44].

The phylogenetic analysis based on the cox1 fragment was performed using 123 unique sequences of 320, representing distinct haplotypes, to visualize the intraspecific relationships of S. mansoni. The best substitution model, K3Pu + F + G4, according to BIC and AIC, was estimated with ModelFinder [45] as implemented in IQ-TREE version 2. The nd5-based phylogenetic analysis included all 27 available sequences. A phylogenetic tree was inferred using the maximum likelihood (ML) method and the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano model [46]. Schistosoma rodhaini Brumpt, 1931, was used as the outgroup for rooting the phylogenetic trees, given its close evolutionary relationship with S. mansoni. The consistency of the maximum likelihood (ML) tree was validated by an ultrafast bootstrap value of 1000 using IQ-TREE version 2 [47,48]. The final phylogenetic tree was visualized with FigTree version 1.4.4.

3. Results

Eight nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cox1 gene fragment (353 to 425 bp) and four sequences of the mitochondrial nd5 gene locus (259 to 271 bp) were obtained from S. mansoni cercariae and sporocysts from B. pfeifferi in the Republic of Guinea. All sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (Table 1).

3.1. Genetic Diversity

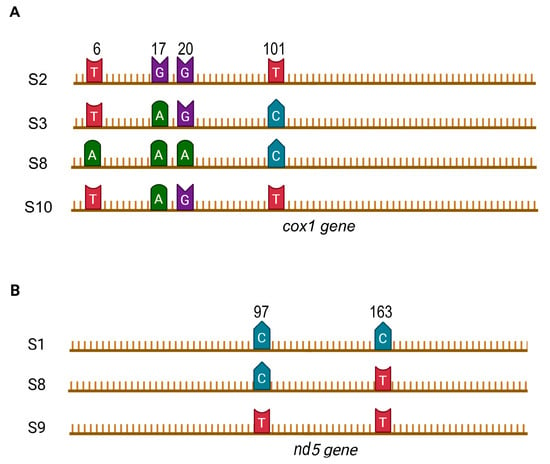

The sequences obtained for the cox1 gene fragment of S. mansoni were represented by four haplotypes. The mutations that distinguish them are shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

The position of the mutation in the mtDNA sequences obtained from S. mansoni infecting B. pfeifferi in Guinea: (A)—cox1 gene fragment 290 bp in length; (B)—nd5 gene fragment 209 bp in length.

The haplotype diversity (Hd) of S. mansoni samples collected from naturally infected mollusks in Guinea was similar to the Hd calculated for sequences of the same cox1 gene region obtained from trematodes parasitizing a human who had migrated from this country to Europe (Table 2). Five haplotypes of this gene fragment have been identified in Guinea in total, with the Hd for the Guinean dataset as a whole being comparable to that for samples from mollusks and humans separately (0.74–0.75).

Table 2.

Characterization of S. mansoni genetic diversity across different countries and regions based on partial cox1 (290 bp) and nd5 (209 bp) gene fragments.

The value of Hd generally corresponds to the haplotype diversity of S. mansoni local groups calculated for the analyzed gene fragment in most countries and across entire West Africa (0.82), with the exception of the Hd value recorded for Mali (0.48), which is significantly lower. Schistosoma mansoni populations in Southeast Africa exhibit a higher level of diversity (0.96), while populations in South America show diversity that is almost twice as low (Table 2).

A significant correlation was found between the number of sequences analyzed and the number of haplotypes identified in each country and region (rs = 0.96, p < 0.01). In contrast, no correlation was observed between the sample sizes and haplotype diversity (Hd) (rs = 0.17, p = 0.45). Therefore, the lower Hd in S. mansoni populations from West Africa compared to Southeast Africa is not an artifact of sampling effort but likely reflects greater isolation among local populations in the latter region.

The nucleotide diversity (π) of the analyzed cox1 gene fragment shows significant variation. The highest values were recorded in Zambia (π = 0.04) and Kenya (π = 0.03), corresponding to a high level of Hd in these populations. In contrast, extremely low π values were observed in Brazil, Puerto Rico, and certain West African populations, including those in Guinea (Table 2).

The sequences obtained for the nd5 gene fragment are represented by three haplotypes characterized by the mutations shown in Figure 2B. Despite the small number of sequences obtained, the haplotype diversity (Hd) calculated for Guinea for this gene was high, comparable to that calculated for Malawi, the only other African country for which similar data are available (Table 2).

3.2. Phylogeography

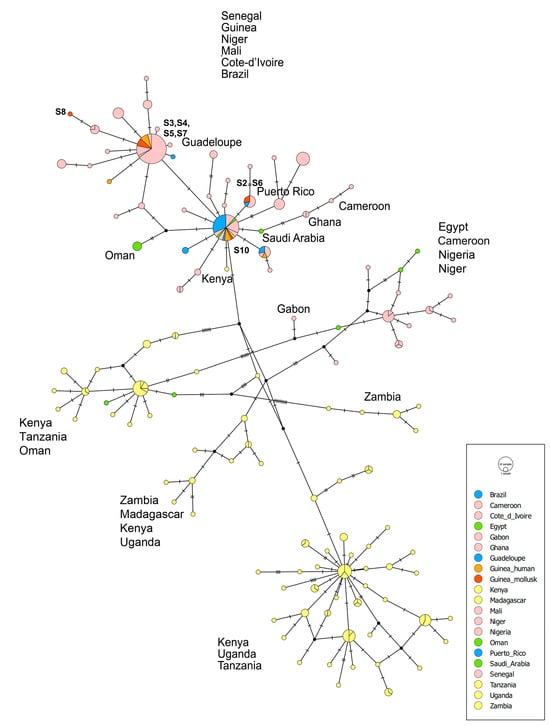

Two haplotypes of the cox1 gene fragment were found in five S. mansoni specimens (S3–S5, S7, and S10) parasitizing mollusks in Guinea (Table 1). These haplotypes were identical to those previously identified in samples of S. mansoni infecting a migrant from the Republic of Guinea [16] (Figure 3). The first haplotype (samples S3–S5, S7) is common in West African countries (Senegal, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, and Niger) and accounts for half of the sequences obtained from both mollusks (4 out of 8) and humans (4 out of 9), and overall sequences in Guinea (8 out of 17). The second haplotype, found alone (S10) in our samples and in four sequences from a patient in Spain, is the most geographically widespread, occurring not only in West Africa but also in South America, the Middle East, and Kenya. The third haplotype (S2 and S6) was identified for the first time in S. mansoni from Guinea and had previously been reported in Senegal. Finally, the fourth haplotype (S8) was unique and had not been recorded before.

Figure 3.

TCS haplotype network based on the S. mansoni cox1 mtDNA dataset. Haplotypes are colored according to their geographic origin. Key: red and orange—Guinea; pink—West Africa; yellow—Southeast Africa and Madagascar; green—Egypt and the Arabian Peninsula; blue—South America and the Caribbean. The total number of sequences is 312. Of these, 304 were retrieved from GenBank and are detailed in Table S1. The alignment length is 290 bp. Mutational steps between haplotypes are represented by perpendicular lines.

All haplotypes of the cox1 gene fragment of S. mansoni found in Guinea, both in the present (from mollusks) and previous (from humans) studies, fell into two haplogroups associated with the dominant and subdominant S. mansoni haplotypes in West Africa and South America. At the same time, the haplotypes from Guinea are distanced from the haplotypes found in East Africa (Figure 3).

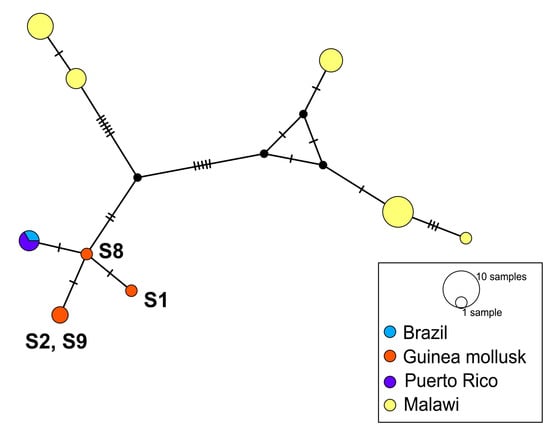

All three nd5 haplotypes identified in S. mansoni samples from Guinea were unique and closely related to the haplotype recorded in South America (Figure 4). At the same time, they are significantly distant from the haplotypes spread in S. mansoni populations from Malawi, located in Southeast Africa.

Figure 4.

TCS network based on the S. mansoni nd5 mtDNA dataset with sequences colored according to samples. The total number of sequences is 27. Of these, 23 were retrieved from GenBank and are detailed in Table S1. Alignment length is 209 bp. Mutational steps between haplotypes are represented by perpendicular lines.

3.3. Phylogenetic Relationships

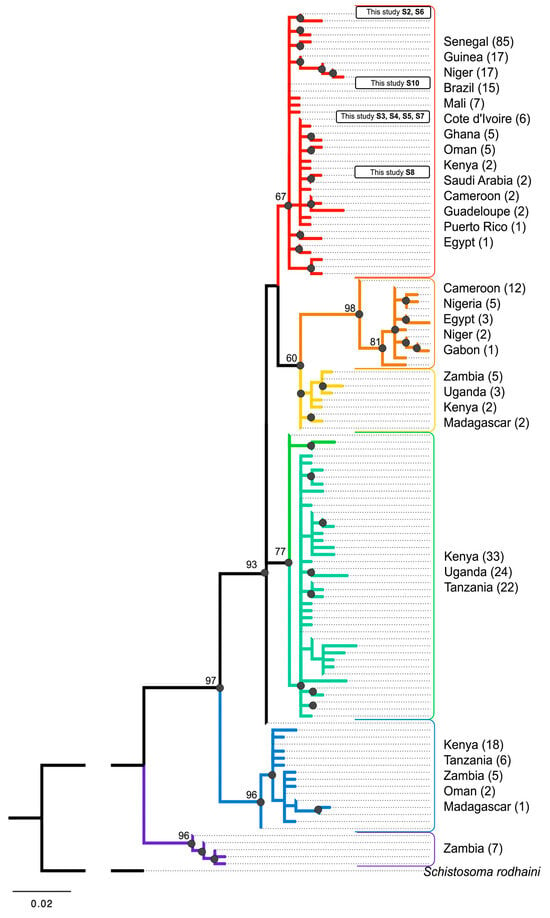

Reconstruction of the phylogenetic relationships among S. mansoni populations based on the cox1 gene fragment revealed a close relationship between trematode samples from the Republic of Guinea and those from other countries in West Africa and South America. These samples form a rather homogeneous group with slight internal differentiation (Figure 5: red clade). This subclade also includes several S. mansoni cox1 gene sequences from the Middle East and Kenya.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationships of S. mansoni from different geographic regions based on partial cox1. The bootstrap support for maximum likelihood > 60 marked by black dots. The number of S. mansoni sequences from different countries is indicated in brackets (312 in total). The total number of unique S. mansoni sequences in the alignment is 122. The alignment length is 290 bp. The colors indicate different clades.

The subclade containing the Guinean samples belongs to a larger clade uniting four groups, two of which comprise solely populations from Southeast Africa (Kenya, Zambia, Uganda, and Tanzania) and Madagascar (Figure 5: yellow and green clades).

The two basal clades are also mainly represented by populations from Southeast Africa, with the most derived branch including only isolates of S. mansoni from Zambia (Figure 5: purple clade).

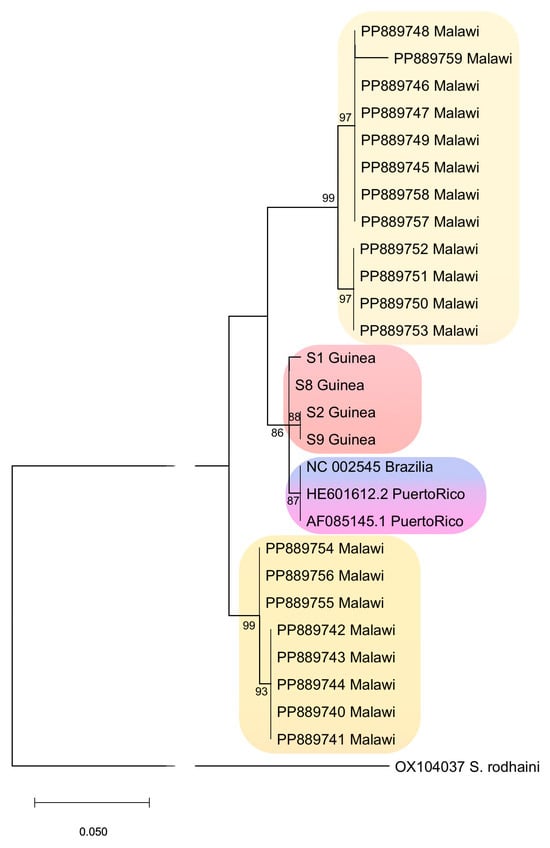

Phylogenetic analysis based on the nd5 gene fragment confirmed the relatedness of S. mansoni populations from West Africa (represented by isolates from Guinea) to populations from Brazil and the Caribbean region (Figure 6). Moreover, it revealed that S. mansoni isolates from Malawi (South East Africa) are represented by two distinct phylogenetic lines.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic relationships of S. mansoni from different geographic regions based on the partial nd5 gene. Nodal numbers indicate bootstrap support for maximum likelihood. The total number of S. mansoni sequences is 27. The alignment length is 290 bp. The colors indicate different clades.

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Diversity

Previous studies of S. mansoni genetic diversity based on the cox1 gene sequences have utilized different fragments of this gene of varying lengths and quantities of data [10,16,18,20,30]. The largest dataset analyzed included 657 cox1 fragments from 25 locations across nine countries, with a focus on Senegal [20]. This analysis revealed that haplotype diversity (Hd) varies widely in West African regions: from 0.85 in northwestern Senegal to 0.54 in Niger. In contrast, a higher overall level of Hd (0.72–0.93) was found in Southeast African countries (Coastal Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, and Zambia). Similar results were obtained earlier [10] based on the analysis of 556 sequences of the cox1 fragment of S. mansoni from the same African countries. The present study used 289 sequences of this gene from 14 African countries, including the Republic of Guinea. The analysis confirmed greater haplotype diversity in the trematode populations in Southeast Africa compared to other regions of the continent. The Hd of S. mansoni in Guinea was found to be 0.74, whereas it was found to be between 0.96 and 1.0 in Southeast African countries. These data are consistent with the previously proposed hypothesis of a Southeast African origin of the parasite [18].

The genetic diversity indices calculated for the African S. mansoni populations in this study are comparable to previously obtained data, despite the differences in the analyzed cox1 fragment datasets. For example, Van den Broeck et al. [20] revealed 103 haplotypes across the continent, Webster et al. [10] found 115 haplotypes, and the present study identified 122 haplotypes. Furthermore, our investigation found that haplotype diversity was 0.89, 0.98, and 0.96 for West African, Southeast African, and all African populations, respectively. These values are comparable to those reported in [10]: 0.84–0.92, 0.96, and 0.94, respectively. The consistency of the results obtained from the analysis of different datasets confirms their representativeness.

As previously observed [10,20], the nucleotide diversity (π) of S. mansoni generally corresponds to the level of haplotype diversity (Hd), being higher among populations of this trematode in Southeast Africa than in West Africa. In the present study, nucleotide diversity was found to be 0.010, 0.026, and 0.024 for West African, Southeast African, and all African populations, respectively, and similarly 0.009, 0.031, and 0.025 according to [10].

Despite the nd5 gene being proposed as a more suitable marker than cox1 for studying schistosome populations [49], data on S. mansoni nd5 gene sequences remain limited in terms of both quantity and geographical coverage. Meanwhile, the genetic diversity established for this gene in our samples from the Republic of Guinea was considerably higher than that observed for cox1 (0.84 vs. 0.74), and, interestingly, notably higher than in samples from Malawi, a region of Southeast Africa (0.84 vs. 0.79).

4.2. Phylogeography

Haplotype network analysis based on a cox1 mtDNA fragment from 14 countries across Africa, along with samples from the Middle East and South America, revealed two main haplotypes accounting for 15% and 11% of the 312 analyzed sequences. The dominant haplotype is only found in West Africa, and most of the sequences obtained from Guinea in this study are represented by it. The second (sub-dominant) haplotype is widespread, occurring not only in West Africa but also in other regions, particularly the Middle East and South America. In contrast, a more branched network was formed by 71 haplotypes from Southeast Africa, where dominant haplotypes are not distinctly distinguished. At the same time, 69 haplotypes form several closely related haplogroups that are not found in other African regions.

Such a distribution of haplotypes is consistent with the theory that the center of origin of S. mansoni is Southeast Africa, with the parasite expanding into South America from West Africa [10]. The presence of dominant haplotypes in West Africa is the result of the founder effect and the relatively recent spread of the trematode in this area. The formation of a widely distributed haplotype in this region may also be due to the greater connectivity of local S. mansoni populations compared to those in Southeast Africa. The freshwater basins of West Africa are more interconnected, whereas the basins of Southeast Africa are more isolated. This is due to the higher mountain ranges, which separate individual basins in the east, while West Africa is characterized by more continuous lowland basins, having extensive floodplains and deltas that allow for greater species dispersal between basins [50].

Haplotype network analysis based on the nd5 mtDNA fragment revealed a similar pattern of significant genetic divergence between S. mansoni populations from West Africa and South America, and those from Southeast Africa. Additionally, the analysis showed the presence of two well-distant haplogroups in Malawi, potentially resulting from the aforementioned segregation of freshwater basins in the Southeast African region.

4.3. Phylogenetic Relationships

Phylogenetic analysis of S. mansoni populations based on the cox1 mtDNA gene fragments revealed six clusters, four of which are geographically associated with Southeast Africa. The most ancient lineage comprises only sequences from Zambia, as previously reported by Webster et al. [10], supporting the hypothesis that S. mansoni expanded from Southeast Africa into other regions of the continent [18].

At the same time, West African populations of S. mansoni were paraphyletic and grouped into two terminal clusters, which may be associated with multiple introductions. Each of these subclades included samples from both Far West (Senegal, Guinea, Niger, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana) and Central West (Cameroon, Nigeria, Gabon) Africa, unlike previous reconstructions where these two West African regions were represented in different monophyletic groups [10,18]. Both clusters that include West African haplotypes also comprise sequences from South America, the Caribbean, and the Middle East, confirming the relatedness of all these populations. However, one sequence from Oman was found to be grouped within a clade containing only samples from Southeast Africa and Madagascar. This clade represents a distinct phylogenetic lineage that diverges significantly from the others. This fact indicates the possibility of another route of expansion of S. mansoni to the Middle East, not through West Africa.

For the first time, the reconstruction of the phylogenetic relationships of S. mansoni populations included sequences from the nd5 gene fragment from West Africa. This enabled the hypothesis of a West African origin for South American S. mansoni populations to be verified using an additional mtDNA locus.

In general, the phylogenetic analyses carried out in the present study using two mtDNA genes confirmed previously established phylogenetic relationships among S. mansoni populations. These include the most likely Southeast African origin of this trematode, the role of West African populations in its spread beyond the continent, and the greater influence of geographical factors than host factors on S. mansoni population structure [10,18,20,21]. However, the inclusion of cox1 sequences from a larger number of African countries, including those from Guinea, obtained in this study, indicated a stronger connection between populations from Far West and Central West Africa than previously assumed. Furthermore, analysis of the nd5 gene sequences revealed significant divergence of S. mansoni haplotypes, even within a single Southeast African region.

Thus, expanding the genomic dataset to include diverse mtDNA genes from a wider range of regions is important for detailing the dispersal routes of S. mansoni. This will improve our understanding of the factors that facilitated its past expansion and help forecast future changes in its geographic distribution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18010039/s1, Table S1: Sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) and nd5 genes of Schistosoma mansoni retrieved from NCBI GenBank and used in the phylogenetic analysis (n = 335).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V. and E.D.; Data curation, E.V.; Formal analysis, D.P., V.U. and E.B.; Funding acquisition, E.D.; Investigation, D.P., V.U. and E.B.; Methodology, E.V.; Project administration, E.D.; Resources, I.K.; Software, D.P.; Supervision, E.V. and E.D.; Validation, E.V. and E.D.; Visualization, E.V. and D.P.; Writing—original draft, E.V., D.P. and E.D.; Writing—review & editing, E.V., I.K. and E.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation: a grant in the form of subsidies in accordance with paragraph 4 of Article 78.1 of the Budget Code of the Russian Federation (Agreement № 075-15-2024-655 on the topic № 13.2251.21.0260).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Bioethics Commission of the Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Sevastopol, Russia (Protocol No. 4(9)/24, 9 October 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the GenBank database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank, accessed on 7 January 2026, under accession numbers PX447850–PX447857 (accessed on 12 October 2025), PX597104–PX597107 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, and Innovation of the Republic of Guinea for inviting them to carry out this study in the country. They would also like to thank the Marine and Coastal Research Centre of Guinea (CEREMAC-G) and, personally, A. I. P. Diallo, for his invaluable administrative and technical support. The authors are grateful for the opportunity to work on the equipment of the Scientific and Educational Research Equipment Sharing Centre “Phylogenomics and Transcriptomics” of the A.O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AN | Accession number |

| AVMA | American Veterinary Medical Association |

| cox1 | Cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 |

| Hd | Haplotype diversity |

| ML | Maximum likelihood |

| NTD | Neglected tropical disease |

| nd5 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 |

| rs | Spearman’s correlation coefficient |

| TCS | Templeton Crandall and Sing haplotype network |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Schistosomiasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Hotez, P.J.; Kamath, A. Neglected tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: Review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease burden. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onasanya, A.; Bengtson, M.; Oladepo, O.; Van Engelen, J.; Diehl, J.C. Rethinking the top-down approach to schistosomiasis control and elimination in sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 622809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, P.; Fürst, T.; Knopp, S.; Utzinger, J.; Tediosi, F. Cost of interventions to control schistosomiasis: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, A.F.; Garba Djirmay, A. Schistosomiasis in Europe. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2023, 10, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aula, O.P.; McManus, D.P.; Jones, M.K.; Gordon, C.A. Schistosomiasis with a focus on Africa. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandasegui, J.; Fernández-Soto, P.; Hernández-Goenaga, J.; López-Abán, J.; Vicente, B.; Muro, A. Biompha-LAMP: A new rapid loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for detecting Schistosoma mansoni in Biomphalaria glabrata snail host. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0005225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, M.O.; Rafalimanantsoa, A.; Ramarokoto, C.; Rahetilahy, A.M.; Ravoniarimbinina, P.; Kawai, S.; Minamoto, T.; Sato, M.; Kirinoki, M.; Rasolofo, V.; et al. Usefulness of environmental DNA for detecting Schistosoma mansoni occurrence sites in Madagascar. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 76, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaylaee, H.; Collins, R.A.; Shechonge, A.; Ngatunga, B.P.; Morgan, E.R.; Genner, M.J. Environmental DNA-based xenomonitoring for determining Schistosoma presence in tropical freshwaters. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, B.L.; Webster, J.P.; Gouvras, A.N.; Garba, A.; Lamine, M.S.; Diaw, O.T.; Seye, M.M.; Tchuem Tchuenté, L.A.; Simoonga, C.; Mubila, L.; et al. DNA ‘barcoding’ of Schistosoma mansoni across sub-Saharan Africa supports substantial within locality diversity and geographical separation of genotypes. Acta Trop. 2013, 128, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savassi, B.A.E.S.; Mouahid, G.; Lasica, C.; Mahaman, S.K.; Garcia, A.; Courtin, D.; Allienne, J.F.; Ibikounlé, M.; Moné, H. Cattle as natural host for Schistosoma haematobium (Bilharz, 1852) Weinland, 1858 × Schistosoma bovis Sonsino, 1876 interactions, with new cercarial emergence and genetic patterns. Parasitol. Res. 2020, 119, 2189–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Elías-Escribano, A.; Artigas, P.; Salas-Coronas, J.; Luzon-Garcia, M.P.; Reguera-Gomez, M.; Cabeza-Barrera, M.I.; Vázquez-Villegas, J.; Boissier, J.; Mas-Coma, S.; Bargues, M.D. Schistosoma mansoni × S. haematobium hybrids frequently infecting sub-Saharan migrants in southeastern Europe: Egg DNA genotyping assessed by RD-PCR, sequencing and cloning. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0012942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilavogui, T.; Verdun, S.; Koïvogui, A.; Viscogliosi, E.; Certad, G. Prevalence of intestinal parasitosis in Guinea: Systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Pathogens 2023, 12, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, M.; Koroma, M.M.; Baldé, M.S.; Turay, H.; Fofanah, I.; Divall, M.J.; Winkler, M.S.; Zhang, Y. Current status of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Beyla and Macenta Prefectures, Forest Guinea. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011, 105, 672–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.S. Freshwater Snails of Africa and Their Medical Importance, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2005; p. 642p. [Google Scholar]

- De Elias-Escribano, A.; Artigas, P.; Salas-Coronas, J.; Luzon-Garcia, M.P.; Reguera-Gomez, M.; Sanchez-Marques, R.; Salvador, F.; Boissier, J.; Mas-Coma, S.; Bargues, M.D. Imported schistosomiasis in Southwestern Europe: Wide variation of pure and hybrid genotypes infecting sub-Saharan migrants. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2025, 2025, 6614509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, A.E.; Olson, P.D.; Østergaard, P.; Rollinson, D.; Johnston, D.A.; Attwood, S.W.; Southgate, V.R.; Horak, P.; Snyder, S.D.; Le, T.H.; et al. The phylogeny of the Schistosomatidae based on three genes with emphasis on the interrelationships of Schistosoma Weinland, 1858. Parasitology 2003, 126, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, J.A.T.; Dejong, R.J.; Adeoye, G.O.; Ansa, E.D.; Barbosa, C.S.; Brémond, P.; Cesari, I.M.; Charbonnel, N.; Corrêa, L.R.; Coulibaly, G.; et al. Origin and diversification of the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 3889–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standley, C.J.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Lange, C.N.; Lwambo, N.J.; Stothard, J.R. Molecular epidemiology and phylogeography of Schistosoma mansoni around Lake Victoria. Parasitology 2010, 137, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, F.; Maes, G.E.; Larmuseau, M.H.; Rollinson, D.; Sy, I.; Faye, D.; Volckaert, F.A.; Polman, K.; Huyse, T. Reconstructing colonization dynamics of the human parasite Schistosoma mansoni following anthropogenic environmental changes in Northwest Senegal. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, R.N., II; Le Clec’h, W.; Chevalier, F.D.; McDew-White, M.; LoVerde, P.T.; Ramiro de Assis, R.; Oliveira, G.; Kinung’hi, S.; Djirmay, A.G.; Steinauer, M.L.; et al. Genomic analysis of a parasite invasion: Colonization of the Americas by the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Mol. Ecol. 2022, 31, 2242–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J.; Cunningham, L.J.; Juhász, A.; Jones, S.; Reed, A.L.; Yeo, S.M.; Mainga, B.; Chammudzi, P.; Kapira, D.R.; Lally, D.; et al. Population genetics and molecular xenomonitoring of Biomphalaria freshwater snails along the southern shoreline of Lake Malawi, Malawi. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, S.M.; Mutuku, M.W.; Mkoji, G.M.; Loker, E.S. Relative compatibility of Schistosoma mansoni with Biomphalaria sudanica and B. pfeifferi from Kenya as assessed by PCR amplification of the S. mansoni ND5 gene in conjunction with traditional methods. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition. Available online: https://apcf-infosite-dev.hkust.edu.hk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/AMVA-Guideline-for-the-Euthanasia-of-Animals-2020-Edition.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Dmitrieva, E.V.; Diakité, S.; Koïvogui, P.; Pronkina, N.V.; Uppe, V.A.; Konate, L.; Sow, M.D.; Balde, A.M.; Camara, M.; Polevoy, D.M.; et al. Schistosoma mansoni (Trematoda: Schistosomatidae) occurrence in Biomphalaria pfeifferi (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) in water bodies of Kindia Prefecture (Republic of Guinea). Mar. Biol. J. 2025, 10, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; Ugene Team. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varella, K.; Gentile, R.; Vilela, R.D.V.; Thiengo, S.C.; dos Santos Moreira, A.; Machado-Silva, J.R.; dos Santos Cardoso, T.; da Costa-Neto, S.F.; de Lima Alessio Müller, B.; dos Santos, A.A.C.; et al. Genetic analysis of Schistosoma mansoni in a low-transmission area in Brazil suggests population sharing between wild-hosts and humans and geographical isolation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, G.S.; Rodrigues, J.G.M.; Resende, S.D.; Camelo, G.M.A.; Silva, J.K.A.O.; Dos Santos, J.C.R.; Silva-Souza, N.; Pereira, F.B.; Furtado, L.F.V.; Rabelo, É.M.L.; et al. From field to laboratory: Isolation, genetic assessment, and parasitological behavior of Schistosoma mansoni obtained from naturally infected wild rodent Holochilus sciureus (Rodentia, Cricetidae), collected in Northeastern Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 2023, 122, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, T.C.; Vilela, R.D.V.; Gentile, R.; Varella, K.; Garcia, J.S.; Cardoso, T.S.; Andrade-Silva, B.E.; Moreira, A.D.S.; Müller, B.L.A.; Santos, A.A.C.D.; et al. Praziquantel effect on genetic diversity of wild rodent-derived Schistosoma mansoni in experimentally infected mice. Exp. Parasitol. 2025, 274, 108963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Červená, B.; Brant, S.V.; Fairet, E.; Shirley, M.H.; Petrželková, K.J.; Modrý, D. Schistosoma mansoni in Gabon: Emerging or ignored? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 95, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, B.; Mwangi, I.N.; Kinuthia, J.M.; Maina, G.M.; Agola, L.E.; Mutuku, M.W.; Steinauer, M.L.; Agwanda, B.R.; Kigo, L.; Mungai, B.N.; et al. Schistosomes of small mammals from the Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya: New species, familiar species, and implications for schistosomiasis control. Parasitology 2010, 137, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidemitt, M.R.; Anderson, L.C.; Wearing, H.J.; Mutuku, M.W.; Mkoji, G.M.; Loker, E.S. Antagonism between parasites within snail hosts impacts the transmission of human schistosomiasis. Elife 2019, 8, e50095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouahid, G.; Mintsa Nguema, R.; Al Mashikhi, K.M.; Al Yafae, S.A.; Idris, M.A.; Moné, H. Host-parasite life-histories of the diurnal vs nocturnal chronotypes of Schistosoma mansoni: Adaptive significance. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.A.; Southgate, V.R.; Rollinson, D.; Littlewood, D.T.; Lockyer, A.E.; Pagès, J.R.; Tchuem Tchuentè, L.A.; Jourdane, J. A phylogeny based on three mitochondrial genes supports the division of Schistosoma intercalatum into two separate species. Parasitology 2003, 127, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, S.; Sène, M.; Diouf, N.D.; Fall, C.B.; Borlase, A.; Léger, E.; Bâ, K.; Webster, J.P. Rodents as natural hosts of zoonotic Schistosoma species and hybrids: An epidemiological and evolutionary perspective from West Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, S.; Léger, E.; Fall, C.B.; Borlase, A.; Diop, S.D.; Berger, D.; Webster, B.L.; Faye, B.; Diouf, N.D.; Rollinson, D.; et al. Multihost transmission of Schistosoma mansoni in Senegal, 2015-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stothard, J.R.; Webster, B.L.; Weber, T.; Nyakaana, S.; Webster, J.P.; Kazibwe, F.; Kabatereine, N.B.; Rollinson, D. Molecular epidemiology of Schistosoma mansoni in Uganda: DNA barcoding reveals substantial genetic diversity within Lake Albert and Lake Victoria populations. Parasitology 2009, 136, 1813–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, T.H.; Blair, D.; Agatsuma, T.; Humair, P.F.; Campbell, N.J.; Iwagami, M.; Littlewood, D.T.; Peacock, B.; Johnston, D.A.; Bartley, J.; et al. Phylogenies inferred from mitochondrial gene orders - a cautionary tale from the parasitic flatworms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 1123–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantappié, M.R.; Galina, A.; Luís de Mendonça, R.; Furtado, D.R.; Secor, W.E.; Colley, D.G.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; Freeman, G., Jr.; Tempone, A.J.; Lannes de Camargo, L.; et al. Molecular characterisation of a NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit 5 from Schistosoma mansoni and inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain function by testosterone. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1999, 202, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, A.R.; Crandall, K.A.; Sing, C.F. A cladistic analysis of phenotypic associations with haplotypes inferred from restriction endonuclease mapping and DNA sequence data. III. Cladogram estimation. Genetics 1992, 132, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D.; Nakagawa, S. POPART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Kishino, H.; Yano, T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 1985, 22, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarowiecki, M.; Huyse, T.; Littlewood, D.T. Making the most of mitochondrial genomes—Markers for phylogeny, molecular ecology and barcodes in Schistosoma Platyhelminthes: Digenea. Int. J. Parasitol. 2007, 37, 1401–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Steenberge, M.W.; Vanhove, M.P.M.; Manda, A.C.; Larmuseau, M.H.D.; Swart, B.L.; Khang’Mate, F.; Arndt, A.; Hellemans, B.; Van Houdt, J.; Micha, J.-C.; et al. Unravelling the evolution of Africa’s drainage basins through a widespread freshwater fish, the African sharptooth catfish Clarias gariepinus. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 1739–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.