Abstract

Biodiversity records are recognized as important for both diversity conservation and ecological studies under the light of global threats faced by aquatic ecosystems. Here, the checklist of Greek rotifer species is presented based on a literature review, as well as current data from 38 inland water bodies. A total of 172 Monogononta rotifer species were recorded to belong to 21 families and 44 genera. The most diverse genera were Lecane, Brachionus, and Trichocerca, accounting for 34% of the recorded species. Trichocerca similis, Brachionus angularis, Filinia longiseta, Asplanchna priodonta, Keratella tecta, Keratella quadrata, and Keratella cochlearis were the most frequent species with a high frequency of occurrence over 60%, with K. cochlearis being the most frequently recorded (86%). Furthermore, we used rarefaction indices, and the potential richness was estimated at 264 taxa. More sampling efforts aiming at littoral species, as well as different habitats such as temporary pools, ponds, and rivers, are expected to increase the known rotifer fauna in Greece. We expect that additional molecular analyses will be needed to clarify the members of species complexes, likely providing additional species.

1. Introduction

Biodiversity is globally recognized as an important component to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems [1,2]. Because molecular approaches are widely used in constructing a genome atlas of biodiversity, including the description of cryptic species complexes from the phylum Rotifera [3,4,5,6,7,8], the importance of taxonomic lists that accurately note the biogeographic distribution of species has become critical. This is of great importance in areas where taxonomic studies are scarce and ecological studies rely on poorly known community assemblages. Moreover, with the global increase in invasive species [9,10] and the concomitant threat faced by aquatic ecosystems due to changes in species composition and food web relationships [11,12,13], the knowledge of the fauna of an area seems more imperative than ever.

Phylum Rotifera (sensu stricto) is a large phylum of microscopic animals found mainly in freshwaters [14,15] containing two major groups: Subclass Monogononta and Subclass Bdelloidea [16,17]. As components of the base of the food web, rotifers shape community energy flow linking the classical food web with the microbial loop; as a result, these micrometazoans are very import in the functioning of aquatic ecosystems [18,19]. However, their study is hindered by several features, and their taxonomic identification requires a level of taxonomical qualification possessed by a few specialists around the world. (1) The phylum possesses a large number of cryptic species complexes [20]. Thus, the identification of a species in two distant regions may actually represent two distinct populations. (2) Nevertheless, rotifers possess a remarkable ability to disperse via anemochory, hydrochory and zoochory [21]. (3) Proper taxonomic identification of rotifer species is difficult because of their microscopic size and the morphological traits are difficult to examine, especially in species that contract when preserved [22]. (4) The keys that exist for species identification are often regional in nature, out of print, and are written in languages unavailable to many. Thus, rotifer taxonomy has been confusing, with names of species that are no longer recognized being used. Recently, taking advantage of the possibilities provided by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), the List of Available Names (LAN) partim Phylum Rotifera has established a list of names of species that clears up many long-standing misconceptions such as incorrect spelling and the same species identified with two names (e.g., Trichocerca birostris and Trichocerca similis) [22,23,24,25]. Still, it is important for everybody to have access to all up-to-date information, including nomenclature or taxonomic changes and new species (re)description [26] for all studies to be based on the most accurate knowledge regarding the species composition of an ecosystem.

As part of the Balkan Peninsula, Greece contains many ancient lakes that are recognized globally for their ecological importance. Studies concerning zooplankton in Greece date back to the end of the 19th century [27,28], but studies on rotifers began much later [29,30]. Τhese studies focused on subclass Monogononta, while Donner [31] later studied rotifers (Bdelloidea and Monogononta) from soil ecosystems. The majority of ecological studies overlook Bdelloidea due to difficulties in the identification of preserved individuals. A compilation of the historic data from 1956 up to 1987 only from inland aquatic water bodies, including mainly lakes, was presented in a checklist for Rotifera from Greece published by Zarfdjian and Economidis [32]. In this checklist, only 3 species of Bdelloidea (Philodina citrina, P. megalotropha, and P. roseola) and 76 species of Monogononta were reported [32]. Since then, several studies reporting species lists of Monogononta species have been published. Herein, we present an up-to-date checklist of Monogononta rotifer species that extends the checklist with both published and current data.

2. Materials and Methods

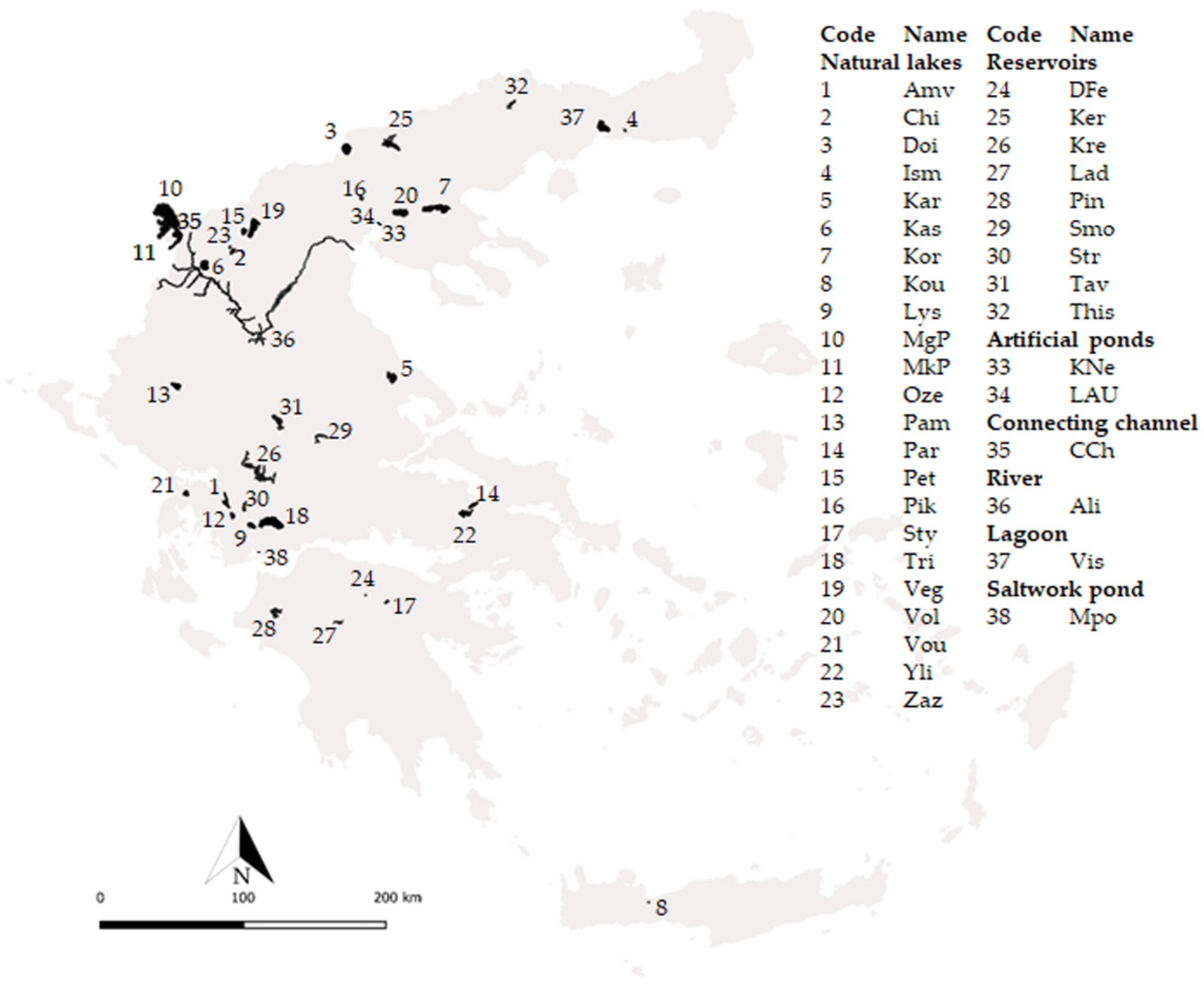

Here, we provide data from 38 inland water bodies: 23 natural lakes, 9 reservoirs, 2 artificial urban ponds, a man-made water channel connecting lakes Mikri Prespa and Megali Prespa, a river, a lagoon, and a saltwork pond (Figure 1). Morphometric characteristics, trophic state, and salinity for each water body are presented in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Map of Greece showing the locations of the 38 water bodies included in the study. Abbreviations: Amv: Amvrakia; Chi: Chimaditida; Doi: Doirani; Ism: Ismarida; Kar: Karla; Kas: Kastoria; Kor: Koronia; Kou: Kournas; Lys: Lysimaxeia; MgP: Megali Prespa; MkP: Mikri Prespa; Oze: Ozeros; Pam: Pamvotis; Par: Paralimni; Pet: Petron; Pik: Pikrolimni; Sty: Stymfalia; Tri: Trichonis; Veg: Vegoritis; Vol: Volvi; Vou: Voulkaria; Yli: Yliki; Zaz: Zazari; DFe: Doxa-Feneou; Ker: Kerkini; Kre: Kremasta; Lad: Ladona; Pin: Pineiou; Smo: Smokovo; Str: Stratos; Tav: Tavropou; This: Thisavros; KNe: Kipos nerou pond; LAU: Limnoula auth; CCh: Connecting Channel (between the Megali and Mikri Prespa); Ali: Aliakmon; Vis: Vistonis; Mpo: Messolonghi pond.

The checklist of rotifers recorded in inland water bodies from Greece compiled herein is based on already published data and data of the present study. A bibliographic review of rotifers’ diversity was conducted using the databases Google Scholar and Web of Science using the search words “rotifer”, “Greece”, and “diversity” during the entire period available in each database (retrieved during January 2022) and the National Archive of PhD Theses of Greece. Grey literature including bachelor and master theses and technical reports conducted by members of the Department of Zoology of School of Biology of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki are also presented. Moreover, historic data from 1956 to 1987 included in the previous checklist [32] not available in the databases are cited as Zarfdjian and Economidis (1989) in Table S1. In compiling our dataset, we did not include studies that provided only genus-level identifications or did not mention the sampled water body. The list of consulted works per water body is available in Table S1.

Data were sorted into an Excel file according to the water body (Table S2). The checklist provided here does not contain a listing of the infraspecific taxa in order to avoid subjectivity in species diversity estimation since we do not know which of the ‘subspecies’ are proper species and which ones are cyclomorphs. Currently valid species names, authorships, synonyms, and spelling were verified and updated using the Rotifer World Catalog [17] according to the recent List of Available Names (LAN) of International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature for rotifer species [22,23,24,25]. When necessary, we checked the species identifications based on available samples and pictures and we updated the species complexes of Brachionus calyciflorus and Brachionus plicatilis based on the literature [5,33,34]. The species checklist was not arranged based on the phylogeny of Monogononta, but rotifers genera and species were arranged in alphabetic order.

The relative frequency of occurrence (i.e., the number of times a certain species occurred in all examined water bodies) was calculated for all species. Two estimators of species richness Chao2 and 2nd-order jackknife (Jackknife2) were calculated using EstimateS 9 [35]. From the diversity estimators, we derived the efficiency percentage of each estimator with the following formula:

where Sobserved is the number of the observed species, and Sestimated is the number of the estimated species.

3. Results and Discussion

The total number of rotifer species reported from Greece was 172 (Table 1). These species have been classified into 1 class of Eurotatoria, 2 superorders, 3 orders, 21 families, and 44 genera (Table 2). The most diverse genera were Lecane (24 species) and Brachionus (20 species) followed by Trichocerca (15 species) (Table 2). For the remaining genera, less than 10 species were recorded, while for 13 of them only 1 species was recorded in Greece.

Table 1.

List of rotifer species recorded in the 38 water bodies of Greece (abbreviations according to Figure 1).

Table 2.

Number of species per genus.

Βased on the so-called “Rotiferologist Effect”, our knowledge of rotifer biodiversity across the globe is highly biased toward the areas where taxonomists live and work or go on holiday or for fieldwork [36,37]. At a regional scale, Fontaneto et al. [37] compiled a database of Monogononta up to 1992, highlighting the low diversity in the South Balkan region. This low diversity is a misestimation based on the lack of knowledge for species from this area due to low sampling intensity. Specifically for Greece, Zarfdjian and Economidis [32] published the first checklist for rotifers, reporting 76 Monogononta based on published and grey literature up to 1987. The number of studies on rotifers has increased, and currently, updated checklists are being published around the world (e.g., [38,39,40,41]). According to the updated checklists of neighboring countries, Italy has 362 Monogononta [41], followed by Greece (172 species) and Albania with 132 species [38]. Greece and Albania share a high number of common species, which was expected because they are located within the same geographical region and because they share freshwater ecosystems: Lake Mikri Prespa and Lake Megali Prespa (Figure 1).

Rotifer taxonomy has been used in index development for the assessment of water bodies. Rotifers are known to be useful indicators of trophic states in oligotrophic and hypertrophic lakes and have been used for the development of indices using various metrics, including the use of indicator species [42]. Even though rotifer-based indices have also been developed in the Mediterranean region, indicator species were not found to be applicable [43,44]. The indicator species proposed by Karabin [42] for oligotrophic or hypertrophic waters dominating only in either low or high trophic state have been recorded in water bodies of all trophic types in Greece. Only rotifers known to have salinity tolerance [17,45] (i.e., Brachionus asplanchnoidis, B ibericus, B. plicatilis, B. rubens, Filinia cornuta, Hexarthra oxyure, H. polyodonta, Lecane lamellate, Macrochaetus collinsii, and Notholca salina) were indicative of the water bodies with increased salinity (oligohaline to hyperhaline).

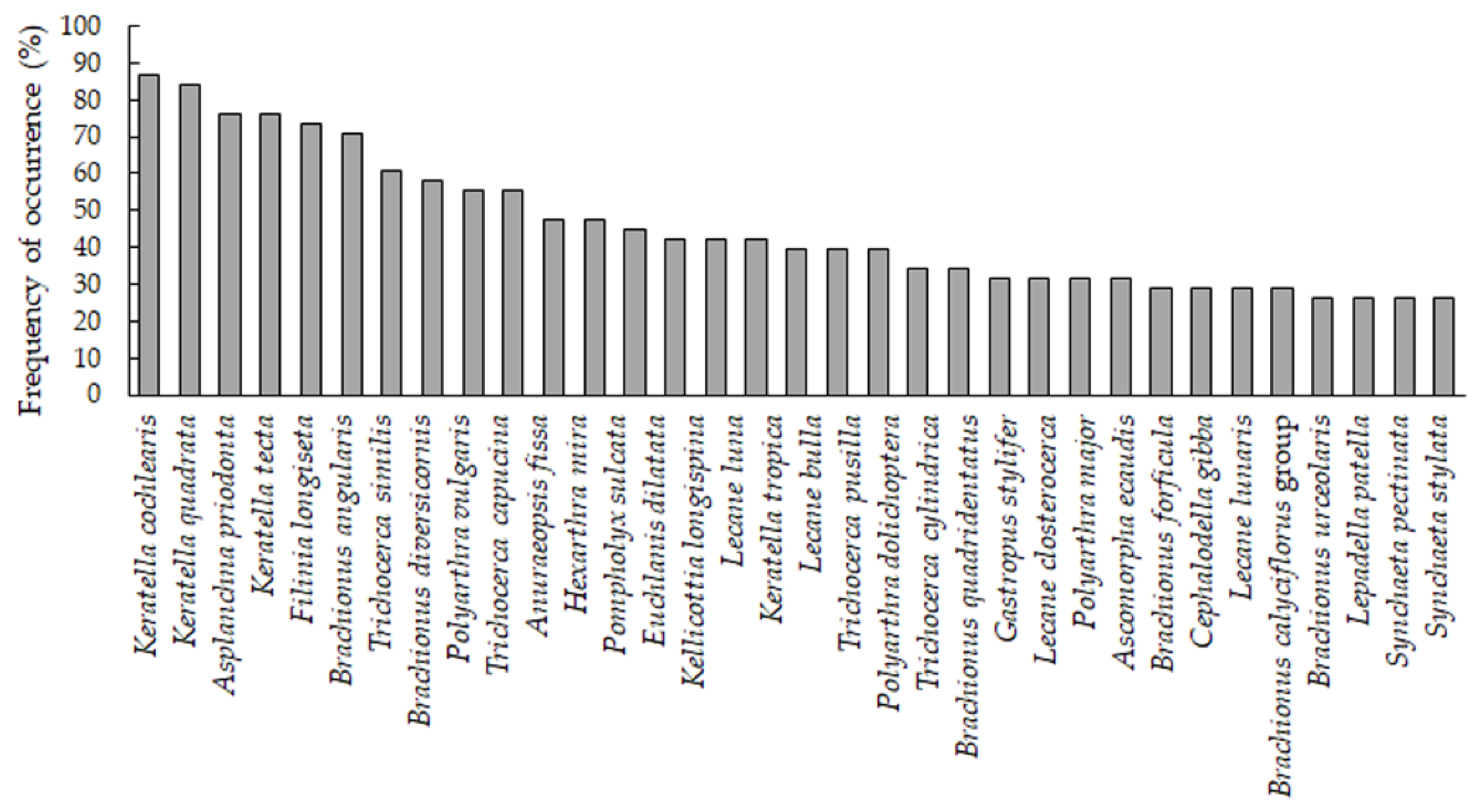

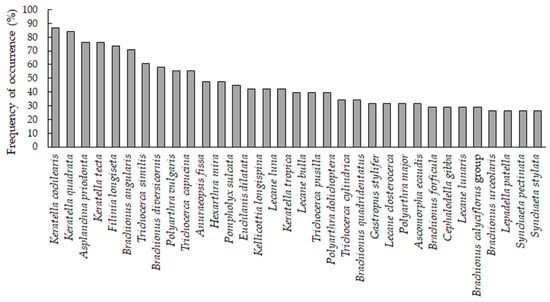

The frequency of occurrence varied from 2.6% (for 58 species recorded only from one water body) to 86.84% (for Keratella cochlearis recorded from 33 water bodies). Asplanchna priodonta, Brachionus angularis, Filinia longiseta, Keratella cochlearis, K. quadrata, K. tecta, and Trichocerca similis were the most frequent species, with a frequency of occurrence over 60% (Figure 2). These seven species are known to be cosmopolitan, common in freshwater lakes, reservoirs, ponds, and in potamoplankton and can be encountered both in littoral habitats and in open water [17]. Molecular studies from different regions have shown that the above-mentioned Keratella species may possibly be species complexes [8,20,46]. Therefore, the further investigation of cryptic species in the studied water bodies is recommended. Of course, it is being generally accepted that cosmopolitan species may actually represent cryptic species complexes [3,4,47], and their delineation will eventually further diversify the world’s Rotifera fauna.

Figure 2.

Species of rotifers recorded in Greek waterbodies having a frequency of occurrence over 25%.

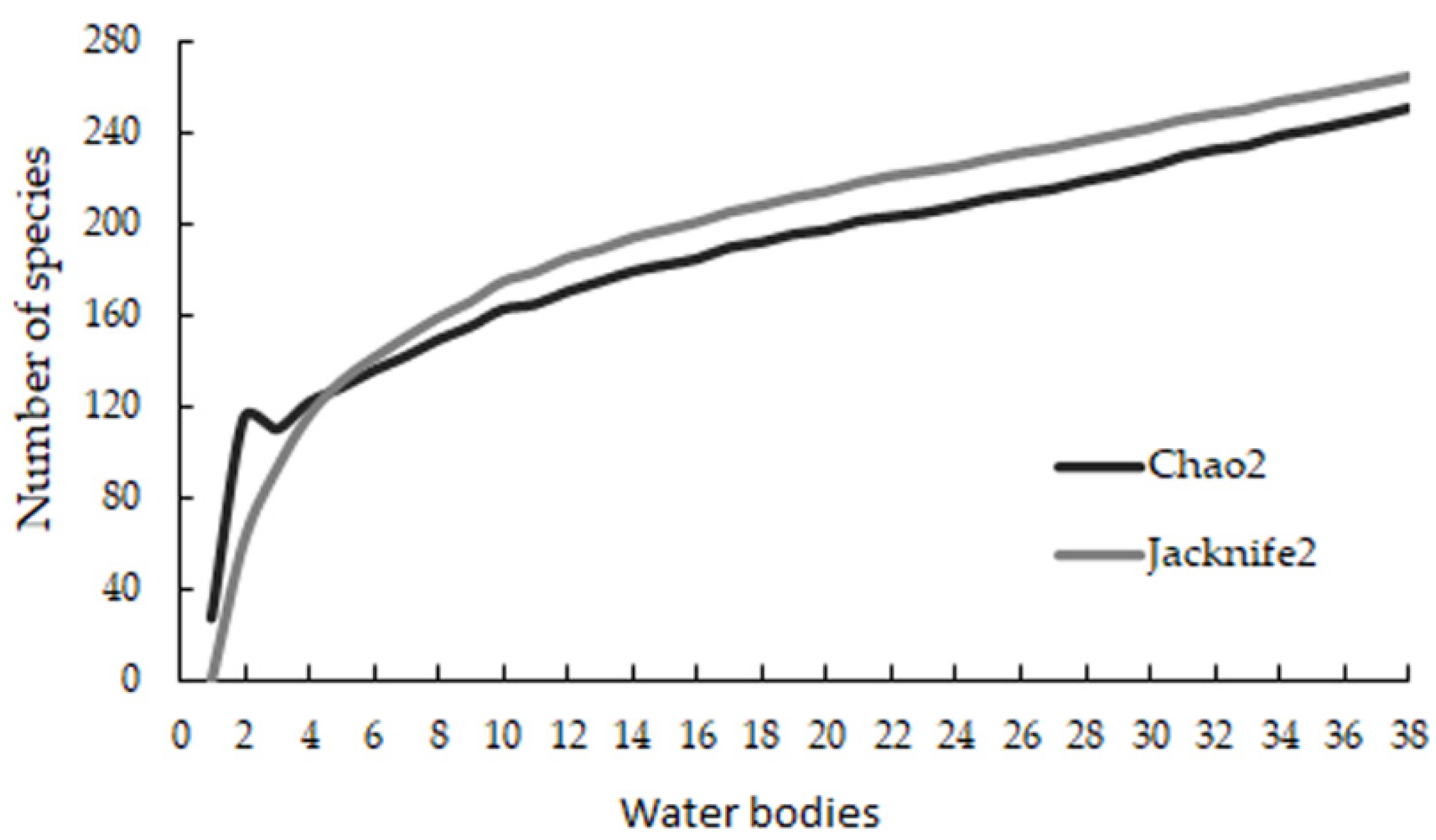

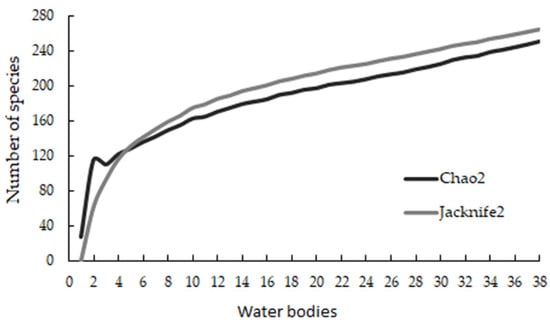

Acknowledging that sampling effort can strongly influence species numbers, we evaluated our dataset with the two estimates of species richness Chao2 and Jackknife2. These two estimates of total species richness showed that the potential species richness should account for 250 species based on the classic Chao2 estimator or even 264 species based on Jacknife2 (Figure 3). Therefore, the efficiency percentage of species estimated varied from 65 to 69% (Jackknife2 and Chao2, respectively).

Figure 3.

Estimation of diversity of rotifers in Greek waterbodies using the estimators Chao2 and Jackknife2.

Our underestimation of species diversity can be justified by various factors. First, the sampling effort is not the same for all water bodies. Studies with long timeseries are missing, while many studies have sparce samplings, usually limited to the summer-autumn season (e.g., [44]). In addition, not all habitats have been evenly sampled in the studied water bodies; normally, samplings are conducted at the deepest part of the lakes [44,48], so littoral species and sessile rotifers have been underestimated. Other important habitats for rotifer biodiversity, such as littoral zones, temporary pools, swamps, ditches, and puddles or even marine water bodies, have not been explored while rivers and ponds are not well studied so far; thus, additional species are expected to be found in future studies.

Moreover, the identification skills of the personnel and the preservation of the samples in formalin solution have led to the identification of specimens down to the genus level (Table 3). Thus, one extra family Flosculariidae and two extra genera Ptygura and Sinatherina have been recorded for the Greek fauna based on Table 3. Seven more species, namely Collotheca ornata, Colurella hindenburgi, Enteroplea lacustris, Floscularia ringens, Keratella testudo, Lecane cornuta, and Ptygura brevis, are reported from the islands [31,32]; however, the specific water body was not mentioned. Thus, they were not included in the present checklist.

Table 3.

List of taxa identified down to the genus level.

When molecular analysis is more widely used, more information will become available on which species actually comprise complexes of cryptic species. We expect that the numbers of species of any area will increase. Only three studies exist so far for the Greek rotifera fauna by identifying rotifer species using molecular tools: Proios et al. [49] for Brachionus sessilis, Michaloudi et al. [34] for B. asplanchnoidis, and Zhang [50] for B. calyciflorus. However, more species complexes have been identified worldwide accompanied by proper species descriptions, while others have yet to be described. One example is K. cochlearis, which has been proposed as a species complex of eight putative species based on molecular analysis; however, further morphological analysis is needed for those species to complete the proper taxonomical procedure to make already described morphological forms valid species and describe new ones [8]. From the known varieties Keratella cochlearis, var hispida has been recorded based on morphological characteristics in Greece (e.g., Lake Mikri Prespa [51]). Furthermore, phylum Rotifera is replete with species well known for their morphological plasticity. This characteristic has resulted in groups of species that have not yet been taxonomically or molecularly identified. Thus, the effort placed toward the integrative taxonomy, using molecular mapping of diversity combined with morphological analysis and classical taxonomy, will yield many more ‘new’ species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d14060451/s1, Table S1: Water bodies’ characteristics; Table S2: Rotifers raw data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and G.S.; formal analysis, G.S.; investigation, E.M., G.S., A.S. andM.D.; resources, E.M.; data curation, E.M. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, E.M., G.S., A.S. andM.D.; visualization, G.S.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We firmly thank all students who during their bachelor and master theses provided species lists about rotifer communities. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the anonymous reviewers whose valuable suggestions were extremely helpful to finally shape the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Benayas, J.M.R.; Newton, A.C.; Diaz, A.; Bullock, J.M. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: A meta-analysis. Science 2009, 325, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, J.M.; Aronson, J.; Newton, A.C.; Pywell, R.F.; Rey-Benayas, J.M. Restoration of ecosystem services and biodiversity: Conflicts and opportunities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.; Alcántara-Rodríguez, J.A.; Ciros-Pérez, J.; Gómez, A.; Hagiwara, A.; Galindo, K.H.; Jersabek, C.D.; Malekzadeh-Viayeh, R.; Leasi, F.; Lee, J.S.; et al. Fifteen species in one: Deciphering the Brachionus plicatilis species complex (Rotifera, Monogononta) through DNA taxonomy. Hydrobiologia 2017, 796, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papakostas, S.; Michaloudi, E.; Proios, K.; Brehm, M.; Verhage, L.; Rota, J.; Peña, C.; Stamou, G.; Pritchard, V.L.; Fontaneto, D.; et al. Integrative taxonomy recognizes evolutionary units despite widespread mitonuclear discordance: Evidence from a rotifer cryptic species complex. Syst. Biol. 2016, 65, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaloudi, E.; Papakostas, S.; Stamou, G.; Neděla, V.; Tihlaříková, E.; Zhang, W.; Declerck, S.A. Reverse taxonomy applied to the Brachionus calyciflorus cryptic species complex: Morphometric analysis confirms species delimitations revealed by molecular phylogenetic analysis and allows the (re) description of four species. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obertegger, U.; Fontaneto, D.; Flaim, G. Using DNA taxonomy to investigate the ecological determinants of plankton diversity: Explaining the occurrence of Synchaeta spp. (Rotifera, Monogononta) in mountain lakes. Freshw. Biol. 2012, 57, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obertegger, U.; Flaim, G.; Fontaneto, D. Cryptic diversity within the rotifer Polyarthra dolichoptera along an altitudinal gradient. Freshw. Biol. 2014, 59, 2413–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieplinski, A.; Weisse, T.; Obertegger, U. High diversity in Keratella cochlearis (Rotifera, Monogononta): Morphological and genetic evidence. Hydrobiologia 2017, 796, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallardo, B.; Clavero, M.; Sánchez, M.I.; Vilà, M. Global ecological impacts of invasive species in aquatic ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geburzi, J.C.; McCarthy, M.L. How do they do it?–Understanding the success of marine invasive species. In YOUMARES 8–Oceans Across Boundaries: Learning from Each Other; Jungblut, S., Liebich, V., Bode, M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, J.R.; Carpenter, S.R.; Zanden, M.J.V. Invasive species triggers a massive loss of ecosystem services through a trophic cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4081–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, P.; Thebault, E.; Anneville, O.; Duyck, P.F.; Chapuis, E.; Loeuille, N. Impacts of invasive species on food webs: A review of empirical data. Adv. Ecol Res. 2017, 56, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jeppesen, E.; Beklioğlu, M.; Özkan, K.; Akyürek, Z. Salinization increase due to climate change will have substantial negative effects on inland waters: A call for multifaceted research at the local and global scale. Innovation 2020, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, R.L. Rotifers: Exquisite metazoans. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002, 42, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Segers, H. Global diversity of rotifers (Rotifera) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2008, 595, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, H. The nomenclature of the Rotifera: Annotated checklist of valid familyand genus-group names. J. Nat. Hist. 2002, 36, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jersabek, C.D.; Leitner, M.F. The Rotifer World Catalog. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. 2013. Available online: http://www.rotifera.hausdernatur.at/ (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Allan, J.D. Life history patterns in zooplankton. Am. Nat. 1976, 110, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R.L.; Snell, T.W.; Smith, H.A. Chapter 13-Phylum Rotifera. In Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates, 4th ed.; Thorp, J.H., Rogers, D.C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 225–271. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morales, A.E.; Elías-Gutiérrez, M. DNA barcoding of freshwater Rotifera in Mexico: Evidence of cryptic speciation in common rotifers. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havel, J.E.; Shurin, J.B. Mechanisms, effects, and scales of dispersal in freshwater zooplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2004, 49, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segers, H.; De Smet, W.H.; Fischer, C.; Fontaneto, D.; Michaloudi, E.; Wallace, R.L.; Jersabek, C.D. Towards a list of available names in zoology, partim Phylum Rotifera. Zootaxa 2012, 3179, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jersabek, C.D.; De Smet, W.H.; Hinz, C.; Fontaneto, D.; Hussey, C.G.; Michaloudi, E.; Wallace, R.L.; Segers, H. List of Available Names in Zoology, Candidate Part Phylum Rotifera, genus-group names established before 1 January 2000. 2018a. Available online: https://archive.org/details/LANCandidatePartGeneraRotifera (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Jersabek, C.D.; De Smet, W.H.; Hinz, C.; Fontaneto, D.; Hussey, C.G.; Michaloudi, E.; Wallace, R.L.; Segers, H. List of Available Names in Zoology, Candidate Part Phylum Rotifera, species-group names established before 1 January 2000. 2018b. Available online: https://archive.org/details/LANCandidatePartSpeciesRotifera (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- ICZN (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature). Opinion 2430–Parts of the List of Available Names in Zoology for phylum Rotifera: Accepted. Bull. Zool. Nomencl. 2019, 76, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J. Challenges for taxonomy. Nature 2002, 417, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, J. Animaux inférieurs, notamment Entomostracés, recueillis par M. le Prof. Steindachner dans les lacs de la Macédoine. Ann. K. R. Nat. Hist. Hofmus. Wien. 1892, 7, 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, J. Entomostracés, recueillis par M. le Directeur Steindachner dans les lacs de Janina et de Scutari. Ann. Naturh. Mus. Wien. 1897, 12, 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Berzinš, B. Liste des Rotiféres provenant du lac Kourna, île de Crète (Grèce). Fragm. Balc. 1956, 1, 207–208. [Google Scholar]

- De Ridder, M. Radierdieren vit Griekland. Biol. Jaarb. 1967, 85, 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, P.J. Rotatorien aus einigen Auböden der Donau, aus ostmediterranen Böden und aus Kiew. Veröffentlichungen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Donauforschung 1971, 4, 352–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarfdjian, M.H.; Economidis, P.S. Listes provisoires des Rotifères, Cladocéres et Copépodes des eaux continentals Grecques. Biologia Gallo-Hellenica 1989, 15, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ciros-Pérez, J.; Carmona, M.J.; Serra, M. Resource competition between sympatric sibling rotifer species. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2001, 46, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaloudi, E.; Mills, S.; Papakostas, S.; Stelzer, C.P.; Triantafyllidis, A.; Kappas, I.; Vasileiadou, K.; Proios, K.; Abatzopoulos, T.J. Morphological and taxonomic demarcation of Brachionus asplanchnoidis Charin within the Brachionus plicatilis cryptic species complex (Rotifera, Monogononta). Hydrobiologia 2017, 796, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K. EstimateS_9.1_Windows. Available online: https://osf.io/su57f/ (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Segers, H.; De Smet, W.H. Diversity and endemism in Rotifera: A review, and Keratella Bory de St Vincent. Biodivers Conserv. 2008, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaneto, D.; Barbosa, A.M.; Segers, H.; Pautasso, M. The ‘rotiferologist’effect and other global correlates of species richness in monogonont rotifers. Ecography 2012, 35, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumka, S. Checklist of rotifer species from Albania (phylum Rotifera). Opusc. Zool. Inst. Zoosyst. Oecol. Univ. Bp. 2021, 52, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.; Soto, L.M.; Lafuente, W.; Stamou, G.; Michaloudi, E.; Papakostas, S.; Fontaneto, D. Rotifers from inland water bodies of continental Ecuador and Galápagos Islands: An updated checklist. Zootaxa 2020, 4768, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarma, S.S.S.; Jiménez-Santos, M.A.; Nandini, S. Rotifer Species Diversity in Mexico: An Updated Checklist. Diversity 2021, 13, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaneto, D.; Bertani, I.; Cancellario, T.; Rossetti, G.; Obertegger, U. The new Checklist of the Italian Fauna: Rotifera. Biogeogr. –J. Integr. Biogeogr. 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont-Karabin, J. The usefulness of zooplankton as lake ecosystem indicators: Rotifer trophic state index. Pol. J. Ecol. 2012, 60, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- García-Chicote, J.; Armengol, X.; Rojo, C. Zooplankton species as indicators of trophic state in reservoirs from Mediterranean river basins. Inland Waters 2019, 9, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamou, G.; Katsiapi, M.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Michaloudi, E. Trophic state assessment based on zooplankton communities in Mediterranean lakes. Hydrobiologia 2019, 844, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaneto, D.; De Smet, W.H.; Ricci, C. Rotifers in saltwater environments, re-evaluation of an inconspicuous taxon. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2006, 86, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaneto, D. Molecular phylogenies as a tool to understand diversity in rotifers. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 2014, 99, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, T.; Walsh, E.J. Cryptic speciation in the cosmopolitan Epiphanes senta complex (Monogononta, Rotifera) with the description of new species. Hydrobiologia 2007, 593, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaris, A.D.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Michaloudi, E.; Bobori, D.C. Biogeographical patterns of freshwater micro-and macroorganisms: A comparison between phytoplankton, zooplankton and fish in the eastern Mediterranean. J. Biogeogr. 2010, 37, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proios, K.; Michaloudi, E.; Papakostas, S.; Kappas, I.; Vasileiadou, K.; Abatzopoulos, T.J. Updating the description and taxonomic status of Brachionus sessilis Varga, 1951 (Rotifera: Brachionidae) based on detailed morphological analysis and molecular data. Zootaxa 2014, 3873, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, W. Unraveling Hidden Biodiversity: An Example of Integrative Taxonomy Applied to the Hybridizing Brachionus calyciflorus Species Complex. Ph.D. Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Michaloudi, E.; Zarfdjian, M.; Economidis, P.S. The zooplankton of lake Mikri Prespa. Hydrobiologia 1997, 361, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).