Abstract

We report the synthesis and molecular structure as determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction of P,P,P′,P′-tetraisopropyl(1,4-phenylenebis(hydroxymethylene))bis(phosphonate). The compound was fully characterized by 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy, and Mass Spectrometry.

1. Introduction

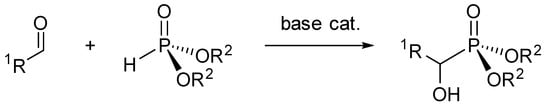

The chemistry of α-hydroxyphosphonates has been widely explored as they find uses in drug design [1,2] and in many other industries for their biological properties [3,4,5]. They are easily produced from the reaction of an aldehyde with a phosphonate under basic conditions [6,7,8] (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

General syntheses of α-hydroxyphosphonates.

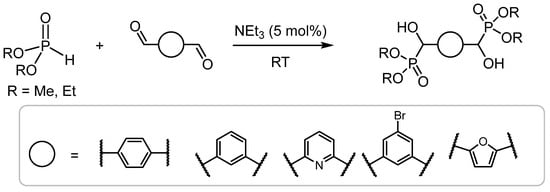

In comparison, bis-α-hydroxyphosphonates (prepared using dialdehydes) are less prevalent in the literature; however, they have been reported to serve as useful precursors for phosphorus-containing polyurethanes, which have excellent flame-retardant properties [9,10]. Hydoxy-functionalised bisphosphonic acids have recently been employed in the preparation of fluorescent MOFs, the detection of nitroaromatic explosives, and drug-delivery systems for cancer-induced osteolytic metastasis [11,12,13]. Recently, Mou et al. reported the synthesis of a series of 1,4- and 1,3- bis-substituted phosphonates using dimethyl or diethyl phosphonate from the corresponding aromatic dialdehyde catalyzed by triethylamine [14] (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

The synthesis of bis-substituted aromatic phosphonates reported by Mou.

These products were characterized by NMR (1H, 13C, and 31P) and HRMS; however, the crystal structures of these materials were not elucidated. Herein, we report the synthesis of P,P,P′,P′-tetraisopropyl(1,4-phenylenebis(hydroxymethylene))bis(phosphonate) (1) using the same method as Mou [10].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Spectroscopy

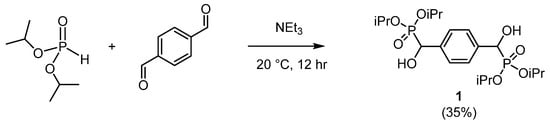

Compound 1 was synthesized by the Pudovik reaction [15] adapted by Mou [10]. Diisopropyl phosphonate was reacted with terephthalaldehyde in a 2:1 molar ratio in the presence of catalytic triethylamine (Scheme 3). The product was isolated by aqueous work-up, and the crude material recrystallised from methanol to afford 1 as colourless crystals.

Scheme 3.

The synthesis of 1.

As 1 has two chiral carbon atoms, it can exist as two diastereoisomers (meso- and rac-); therefore some of the peaks in the 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum (in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6) appear slightly broadened or with ‘shoulders’ (Supporting Information Figure S4). In DMSO-d6 the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum shows a sharp singlet at δP 20.2 ppm, which is shifted slightly downfield from δP 4.5 ppm in diisopropyl phosphonate. This suggests both phosphonate groups are identical chemically and magnetically. The methyl groups in diisopropyl phosphonate are magnetically inequivalent, showing overlapping doublets at δH 1.38 and 1.37 ppm with a shared 3JHH of 6.2 Hz with the CH group. However, in 1, the methyl groups appear as three distinct doublets between δH 1.21 and 1.08 ppm, again with a 3JHH of 6.2 Hz with the CH group of the isopropyl. Significant NMR parameters are provided in Table 1. The hydroxyl hydrogen atom appears as a doublet of doublets at δH 6.07 ppm with a 3JHP coupling of 15.6 Hz, and a 3JHH coupling of 6.0 Hz to the CH group at δH 4.81 ppm, which is also a doublet of doublets with a 2JHP of 12.7 Hz. In the 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum the P–CH–OH peak appears at δC 69.6 ppm with a 1JCP of 165.6 Hz. These NMR parameters are closely related to the ethoxy phosphonate previously reported [10].

Table 1.

Significant NMR parameters of 1 recorded in DMSO-d6 in ambient conditions (1H, 400 MHz, 13C 101 MHz, 31P, 162 MHz).

2.2. Structural Study

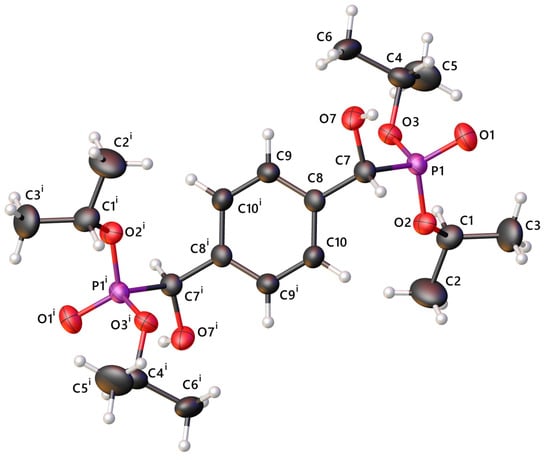

Crystals of 1 that were of suitable quality for single-crystal X-ray diffraction were grown from vapour diffusion of petroleum ether into a solution of 1 in methanol. The structure of racemic 1 was confirmed from these crystals, which adopt the centrosymmetric space group P (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The molecular structure of 1. The anisotropic displacement ellipsoids of non-hydrogen atoms are set at the 50% probability level. Minor components of disorder are omitted for clarity.

The molecule is centrosymmetric around the centroid of the aromatic ring. The bonds are all of typical length with P1–O1 showing clear double-bond character at 1.474(1) Å, and the other P–O bonds at 1.568(1) Å [16]. The phosphorus adopts a distorted tetrahedral geometry with angles ranging from 102.98(7)° to 116.00(7)° (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å), angles (°), torsion angles (°) and displacements (Å) for 1.

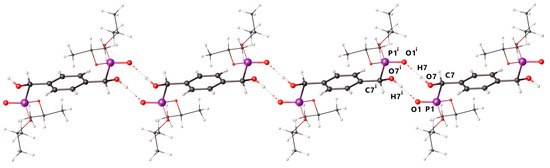

The structure has three points of disorder; two are rocking of the isopropyl groups around their C–O bonds, and the third is positional disorder of the hydroxyl group (O7) as an inversion of the chiral carbon (C7) (Supporting Information Figure S1). In both disordered positions, the hydroxyl group forms hydrogen bonds to P1–O1 of adjacent molecules, forming C(10) chains containing (10) dimers along [0 0 1] (H···O 1.72(3) Å and 1.65(2) Å, O–H···O 176(2) and 177(2)°, for H7 and H7A, respectively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The hydrogen bonding dimer chains in 1 showing running along [0 0 1] (viewed down [1 1 0]). The isopropoxy groups are shown as wireframe, and minor components of distorder are omitted for clarity.

The HRMS spectrum shows two major peaks. The molecular ion with sodium (M + Na+) is visible at 489.1771 amu (calcd. 489.1783), confirming that the identity of 1 matches the expected formula (Supporting Information Figure S9), and the ‘dimer’ with an incorporated sodium ion (2M+Na+) is visible at 955.3650 amu (calcd. 955.3668).

3. Materials and Methods

All synthetic manipulations were performed in air. Glassware was dried in an oven (ca. 110 °C) prior to use. Diisopropyl phosphonate was purchased from ThermoFisher (Birmingham, UK) and used as received. All other chemicals were used as provided from the laboratory inventory without further purification. The IR spectrum was recorded on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum Two instrument with a Deuterated Triglycine Sulfate (DTGS) detector and diamond Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) attachment (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HMRS) data were acquired from the University of St Andrews Mass Spectrometry Service. All NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Avance III 400 MHz spectrometer at 20 °C (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The 13C spectrum was recorded using the DEPTQ-135 pulse sequence with broadband proton decoupling. Tetramethylsilane was used as external standard for 1H and 13C NMR (δH/δC 0.00 ppm), and 85% aqueous H3PO4 was used as the external standard for 31P NMR (δP 0.00 ppm). Where possible, the residual solvent signal was used as a secondary reference (d6-DMSO, δH 2.50, δC 39.52 ppm). Spectra were analyzed using the MestReNova software package (Santiago de Compostela, Spain) (version 14).

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

Terephthalaldehyde (0.67 g, 5 mmol) and diisopropyl phosphonate (1.66 g, 10 mmol) were dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (10 mL). To this, triethylamine (0.36 g, 0.5 mL, 3.6 mmol) was added with stirring. Stirring was maintained for a further 12 h in ambient conditions. After this time, the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure to afford a pale-yellow oil. This was dissolved in diethyl ether (20 mL), washed with distilled water (2 × 5 mL) and dried over magnesium sulfate. The residue was recrystallised from methanol to afford 1 (0.82 g, 35%) (Mp. 195–197 °C).

1H NMR (400.3 MHz, d6-DMSO) δH 7.37 (4H, s, ArC-H), 6.07 (2H, dd, 3JHP 15.6, 3JHH 6.0 Hz, C(H)OH), 4.81 (2H, dd, 3JHP 12.7, 3JHH 6.0 Hz, C(H)OH), 4.56–4.37 (2H, m, CH(CH3)2), 1.19 (12H, d, 3JHH 6.3 Hz, 4 × CH(CH3)2), 1.17 (6H, 3JHH 6.2 Hz, 2 × CH(CH3)2), 1.07 (6H, 3JHH, 6.2 Hz, 2 × CH(CH3)2). 13C DEPTQ NMR (101.7 MHz, d6-DMSO) δC 137.7 (Ar-qC), 126.8 (Ar-CH), 70.3–70.0 (m~d 2JCP 17.1 Hz, P-CH(CH3)2), 69.6 (m~d, 1JCP 165.6 Hz, C(H)OH), 23.9 (s, 2 × CH(CH3)2), 23.6 (s, 1 × CH(CH3)2), 23.5 (s, 1 × CH(CH3)2). 31P{1H} NMR (162.0 MHz, d6-DMSO) δP 20.2 (s). HRMS (ESI+) m/z (%) Calcd. for C20H36O8P2Na 489.1783, found 489.1771 [M+Na] (100); Calcd. for C40H72O16P4Na 955.3668, found 955.3650 [2M+Na] (52). IR: νmax (ATR/cm−1) 3226b (νOH), 2980w (νCH), 1378w, 1209m, 993vs (νP=O), 576s.

3.2. X-Ray Crystallography

X-ray diffraction data for 1 were collected at 173 K using a Rigaku FR-X Ultrahigh Brilliance Microfocus RA generator/confocal optics with XtaLAB P200 diffractometer [Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å)]. Data were collected (using a calculated strategy) and processed (including correction for Lorentz, polarization and absorption) using CrysAlisPro [17]. The structure was solved by dual-space methods (SHELXT) [18] and refined by full-matrix least-squares against F2 (SHELXL-2019/3) [19]. Both isopropyl groups in the asymmetric unit showed rocking disorder and were each refined in two parts with restrained geometry. The hydroxyl oxygen (O7) showed positional disorder as an inversion of chirality at C7 and was refined in two parts with C−O bonds restrained to be the same distance. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and hydrogen atoms were refined using a riding model except for the hydrogen atom on the major component of the hydroxide (O7), which was located from the difference Fourier map and refined isotropically subject to a distance restraint. All calculations were performed using the Olex2 interface [20]. Selected crystallographic data: C20H36O8P2, M = 466.43, triclinic, a = 7.8428(3), b = 7.9556(3), c = 10.5700(4) Å, α = 98.678(3), β = 98.247(3), γ = 105.917(4) °, U = 614.99(4) Å3, T = 173 K, space group P (no. 2), Z = 1, 13327 reflections measured, 2908 unique (Rint = 0.0384), which were used in all calculations. The final R1 [I > 2σ(I)] was 0.0394 and wR2 (all data) was 0.1094.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online: Figure S1: View of the structure of 1 showing the disorder; Figure S2: The 1H NMR spectrum of 1. Acquired in d6-DMSO at 400.3 MHz at ambient conditions; Figure S3: Expansion of the 1H NMR spectrum of 1 between δH 6.25 and 4.20 ppm; Figure S4: The 13C DEPTQ NMR spectrum of 1. Acquired in d6-DMSO at 100.6 MHz at ambient conditions with expansion between 71 and 67 ppm; Figure S5: The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 1 acquired in d6-DMSO at 162.0 MHz at ambient conditions; Figure S6: The H-H COSY NMR spectrum of 1 acquired in d6-DMSO at ambient conditions; Figure S7: The HC HSQC NMR spectrum of 1 acquired in d6-DMSO at ambient conditions; Figure S8: IR spectrum of 1; Figure S9: HRMS spectrum of 1.

Author Contributions

All the required synthetic steps and analysis of NMR, IR, and HRMS data were carried out by J.K.J. with assistance from B.A.C. The X-ray data were obtained and solved by A.P.M. and D.B.C. The study was designed by B.A.C. The manuscript was written by B.A.C. with contributions from all other authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

CCDC 2502673 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the University of St Andrews School of Chemistry for the use of their laboratory facilities and provision of materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| MOF | Metal Organic Framework |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| HRMS | High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| IR | Infrared |

References

- Milen, M.; John, T.M.; Kis, A.S.; Garádi, Z.; Szalai, Z.; Takács, A.; Kőhidai, L.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Activity of a New Family of α-Hydroxyphosphonates with the Benzothiophene Scaffold. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodiazhnyi, O.I. Chrial hydroxy phosphonates: Synthesis, configuration and biological properties. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2006, 75, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboudin, B.; Daliri, P.; Faghih, S.; Esfandiari, H. Hydroxy- and Amino-Phosphonates and -Bisphosphonates: Synthetic Methods and Their Biological Applications. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 890696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedov, A.N.; Davletshin, R.R.; Davletshina, N.V.; Ivshin, K.A.; Fedonin, A.P.; Osogostok, A.R.; Shulaeva, M.P. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Biological Activity of α-Hydroxyphosphonates. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 59, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rádai, Z. α-Hydroxyphosphonates as versatile starting materials. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2019, 194, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, N.Z.; Rádai, Z.; Keglevich, G. Green syntheses of potentially bioactive α-hydroxyphosphonates and related derivatives. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2019, 194, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalla, R.M.N.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, I. Highly efficient green synthesis of α-hydroxyphosphonates using a recyclable choline hydroxide catalyst. New J. Chem. 2017, 14, 5373–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulska, P.; Legrand, Y.-M.; Leśniewicz, A.; Oliviero, E.; Bert, V.; Boulanger, C.; Grison, C.; Olszewski, T.K. Green and Effective Preparation of α-Hydroxyphosphonates by Ecocatalysis. Molecules 2022, 27, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikroyannidis, J.A. Flame Retardation of Polyurethanes by Means of 1,4-Bis(Dialkoxyphosphinyl)HydroxymethylBenzene. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 1988, 26, 855–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Schäfer, A.; Lohstroh, W.; Walter, O.; Döring, M. Phosphorus-Containing Terephthaldialdehyde Addcuts—Structure Determination and their Applications as Flame Retardants in Epoxy Resins. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 108, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, W.-P.; Wang, L.-W.; Yu, H.; Tang, S.-F.; Xu, X. Syntheses, crystal structures, and fluorescence properties of two new copper phosphonates from hydroxy-functionalized bisphosphonic acid ligand. J. Coord. Chem. 2024, 77, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Hu, S.; Wu, X. Rapid and sensitive detection of nitroaromatic explosives by using new 3D lanthanide phosphonates. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 1952–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Sarabia, L.; Quiñones Vélez, G.; Escalera-Joy, A.M.; Mojica-Vázquez, D.; Esteves-Vega, S.; Peterson-Peguero, E.A.; López-Mejías, V. Design of Extended Bisphosphonate-Based Coordination Polymers as Bone-Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Breast Cancer-Induced Osteolytic Metastasis and Other Bone Therapies. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 9440–9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Man, X. An efficient and green method to prepare bis-α-hydroxyphosphonates using triethylamine as catalyst. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2020, 196, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudovik, A.N. Addition of dialkyl phosphites to unsaturated compounds. A new method of synthesis of β-keto phosphonic and unsaturated α-hydroxyphosphonic esters. Doklady Akad. Nauk. SSSR 1950, 73, 449. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, F.; Porayoubi, M.; Sabbaghi, F.; Dušek, M.; Baniyaghoob, S.; Skořepová, E. Database Survey of Single-and-Half-Phosphorus-Oxygen Bonds in Salts with the C2PO2 Segment: Crystal Structure of [NH2C5H4NH][(C6H5)2P(O)(O)]·2H2O. Crystallogr. Rep. 2022, 67, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro, v1 v1.171.43.142a and 44.117a. Rigaku Oxford Diffraction. Rigaku Corporation: Tokyo, Japan, 2024–2025.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2015, 714, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crys. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).