Abstract

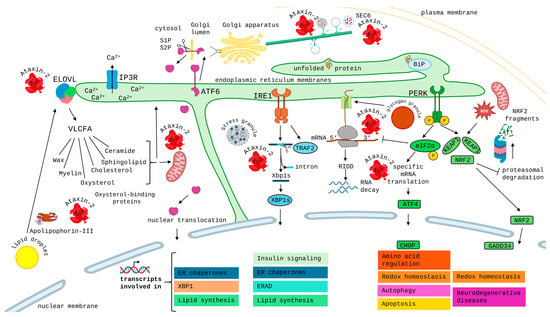

Polyglutamine expansion in Ataxin-2 (ATXN2) is responsible for rare, dominantly inherited Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 2 (SCA2). Together with its paralog Ataxin-2-like (ATXN2L), both proteins have received much interest, since the deletion of their yeast and fly orthologs alleviates TDP-43-triggered neurotoxicity in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis models. Their typical structure across evolution combines LSm with LSm-Associated Domains and a PAM2 motif. To understand the physiological regulation and functions of Ataxin-2 homologs, the phylogenesis of sequences was analyzed. Human ATXN2 harbors multiple alternative start codons, e.g., from an intrinsically disordered sequence (IDR) present since armadillo, or from the polyQ sequence that arose since amphibians, or from the LSm domain since primitive eukaryotes. Multiple smaller isoforms also exist across the C-terminus. Therapeutic knockdown of polyQ expansions in human ATXN2 should selectively target exon 1B. PolyQ repeats developed repeatedly, usually framed and often interrupted by (poly)Pro, originally near PAM2. The LSmAD sequence appeared in algae as the characteristic Ataxin-2 feature with strong conservation. Frequently, Ataxin-2 has added domains, likely due to transcriptional readthrough of neighbor genes during cell stress. These chimerisms show enrichment of rRNA processing; nutrient store mobilization; membrane strengthening via lipid, protein, and glycosylated components; and cell protrusions. Thus, any mutation of Ataxin-2 has complex effects, also affecting membrane resilience.

1. Introduction

Ataxin-2 (human gene symbol ATXN2, protein symbol ATXN2) was discovered as the disease protein responsible for Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 2 (SCA2) [1,2,3] and became widely known because its deletion mitigates the disease progression of TDP-43-triggered Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) or Fronto-Temporal Dementia (FTD) [4,5] and perhaps also a Tau-triggered form of Parkinson-plus syndrome that was named Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) [6,7,8,9]. SCA2 is a rare neurodegenerative process with autosomal dominant inheritance, starting in the spinal cord, brainstem, and cerebellum and leading to a typical combination of muscle cramps, deficient locomotor coordination, intention tremor, and slowed saccadic eye movements, so that patients over the course of 6–25 years become wheelchair-bound, bedridden, and die (usually from swallowing problems) [10,11,12,13,14]. The ages of clinical manifestation occur earlier in successive generations of a pedigree, and the molecular cause of this “anticipation of onset age” is the expansion of a polyglutamine (polyQ) repeat domain near the N-terminus of ATXN2 [15,16,17]. In most healthy individuals worldwide, this domain would contain 22Q, normally encoded by (CAG)8-CAA-(CAG)4-CAA-(CAG)8 [18]. The CAA interruptions in this repeat stabilize the length during genome replication [19], and once they are lost, the DNA polymerase will have difficulty copying the exact length, leading to somatic mosaicism, anticipation over generations, and eventually the appearance of a pure CAG repeat of excessive size that causes neurotoxicity with accumulation of the encoded polyQ expansion [20,21,22,23]. It is reasonable to assume that any expansion beyond 23Q contributes to disease risk, but a controversy exists as to whether this can be formally proven for sizes > 24 or >27. Clearly, at intermediate sizes of 31Q to 33Q, this neurotoxicity becomes relevant in a polygenic manner, affecting only the most vulnerable neurons (spinal and cortical motor neurons in ALS and FTD, respectively, or the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway in Parkinson’s disease and PSP) [4,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. From the threshold of 34Q upward, the neurotoxicity is strong enough to act in a monogenic manner with increasing severity in the multi-system neurodegeneration known as SCA2, either with spinocerebellar deficits upon adult onset [32,33,34] or with developmental delay and seizures upon pediatric onset caused by very long polyQ domains [35]. Expansions where one CAA interruption is still present have been reported several times to be associated with a clinical picture of Parkinson’s disease or ALS [36,37,38,39,40]. Preliminary data, mainly from animal models, also suggest that ATXN2 modifies the disease course of other spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA1/SCA3), adult motor neuron disease (ALS/FTD), and tauopathy-associated Parkinsonism [4,5,6,7,9,16,28,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

However, it is completely unclear how ATXN2 exerts this role as an important modifier protein for neurodegenerative processes. ATXN2 localizes normally to the cytoplasm. A minor quantity of ATXN2 associates with the Golgi apparatus [48,49,50], modulates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) dynamics [51], and associates with the endocytosis complex at the plasma membrane [52,53], where it mediates the fast recycling of the Notch receptor [54]. Thus, the role of ATXN2 in membrane dynamics was documented early on but was not investigated intensely, while an additional role of ATXN2 for RNA has caught most of the attention. The main quantity of ATXN2 is present at the rough ER, where translation of membrane proteins and secreted proteins occurs [55], and associates with polyribosomes [56]. Some ATXN2 was reported to interact with actin and fimbrin [57,58,59], and furthermore, some evidence in favor of microtubule association was published [8,60,61,62,63], so a role of ATXN2 for cell protrusions is apparent. The diffuse distribution of ATXN2 throughout the cytoplasm changes dramatically in periods of cell stress, when it relocalizes with damaged RNA to the cytoplasmic stress granules, where RNA surveillance and triage occur [64,65,66]. Oxidative stress, in particular, is known to cause the maximal recruitment of RNA and translation machinery to stress granules, and one report suggested that ATXN2 influences the fate of superfluous mitochondria as the main source of oxidative stress [67], a notion that is strengthened by evidence that ATXN2 controls the expression levels of PINK1 as the protein kinase, which phosphorylates PARKIN to initiate the autophagic elimination of mitochondria, and that ATXN2 associates with PARKIN as the ubiquitin ligase, which tags mitochondrial outer membrane proteins as targets of removal [68,69,70].

It is still unclear how these localizations reflect ATXN2 functions and interactions in specific pathways. As novel insights, this study analyzes Ataxin-2 orthologs (for brevity, this review will use the term Ataxin-2 as a generic term to include all homologs with similar structure throughout evolution) to document isoforms and the evolution of different domains and regions, thus elucidating their regulation and functional context. The discovery of extra domains that were integrated with Ataxin-2 orthologs into chimeric proteins during evolution, and their explanation as transcriptional readthrough across neighbor genes, triggers the notion that mutations in Ataxin-2 have complex effects on its isoforms and also on the function of genomic neighbors.

The bioinformatic efforts in the current manuscript must take into account how multi-domain proteins such as Ataxin-2 became necessary, and how extra-domains are still getting added even in vertebrates. Recent studies in Euglena gracilis microalgae observed that cells with additional energy from endosymbionts can increase their cytoplasmic volume and show highly flexible cell shapes [71]. However, the diffusion of substrates, cofactors, and proteins becomes insufficient for efficient metabolism in such larger cells. This causes selection pressure that favors assembling multi-component complexes non-covalently, or even better, placing several domains from single pathways within one protein, rather than relying on diffusion. In this manner, the assembly of the LSm domain, LSmAD, PAM2 motif, and IDRs into one large protein would maximize the throughput in a chain of reactions that are important for eukaryotic life. The classical domain combination that constitutes Ataxin-2 is clearly able to respond to oxidative stress and to manage some form of damage control, for RNAs and possibly other vulnerable compounds.

Importantly, diverse eukaryotic species live in different niches, so they had to adapt their metabolic processes further. Therefore, additional domains were appended to the core features of Ataxin-2 in a minority of organisms. The spectrum of variation between these additional domains and functions reflects changes in stressors, as well as alternative stress responses among eukaryotic phyla. In our view, available data on this “tinkering of nature” [72,73] can be exploited to understand the core and accessory mutation effects not only for Ataxin-2 but for any poorly understood protein. The compilation of such additional domains and the analysis of statistically enriched features among them might contribute to understanding how nature modifies and optimizes the core role of an enigmatic protein like Ataxin-2. This approach could elucidate how Ataxin-2 impacts several overlapping pathways. The wealth of sequencing data on species from all kingdoms of life, which is available in databases such as UniProt/UniParc, NCBI/GenBank, and EMBL, can provide many novel insights into physiological connections between metabolic responses and the specific abiotic stressors in each habitat. This approach consumes an enormous amount of time when performed manually but should be amenable to automation and is applicable to many scientific questions.

Overall, this study aimed to understand the modular composition of Ataxin-2 and derive recommendations on which parts are optimal targets for therapy.

2. Results

2.1. Overall Structure of Ataxin-2 Family Members Across Evolution

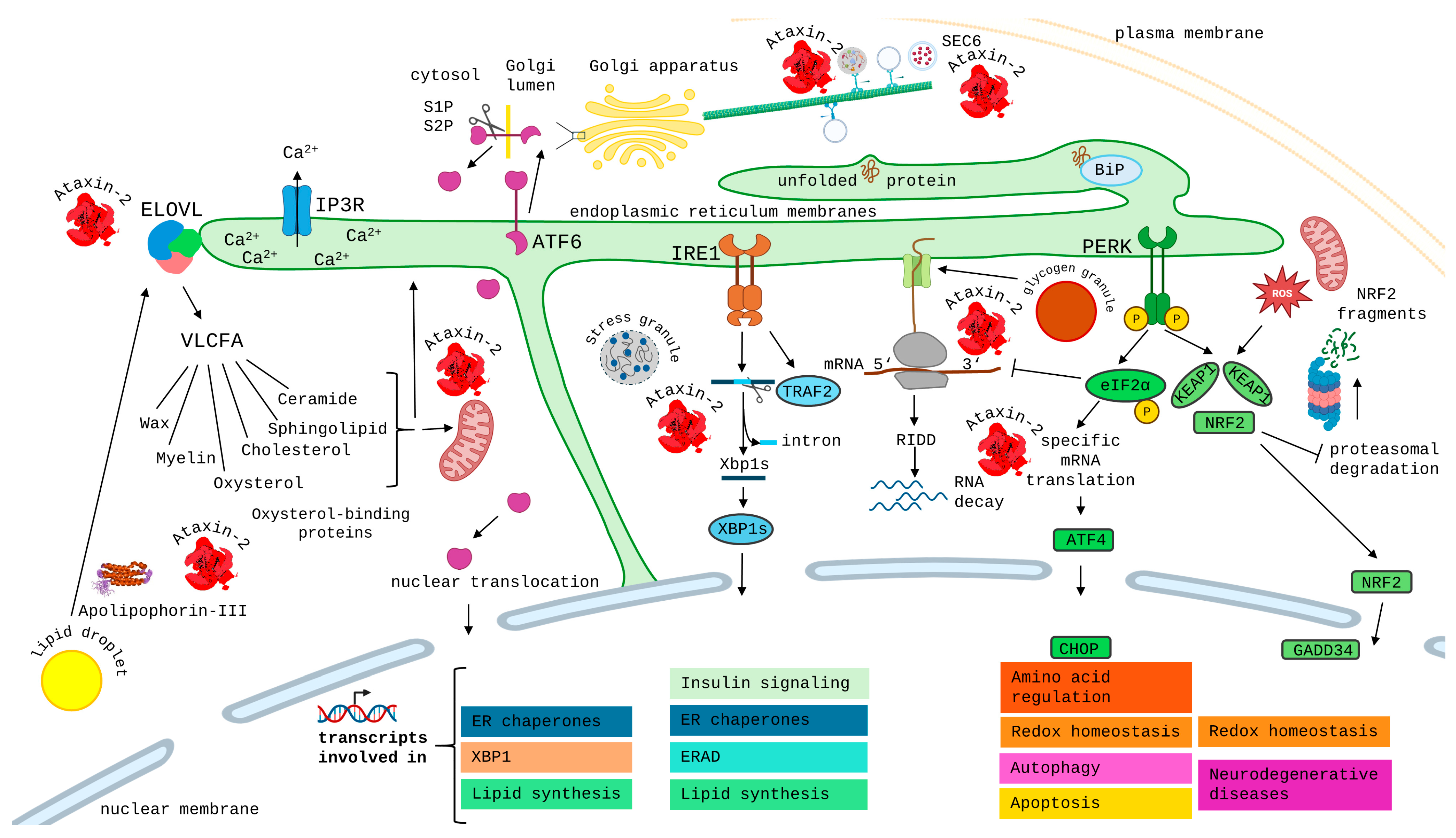

The multi-domain protein Ataxin-2 family has three conserved sequence motifs in a defined order [74,75,76]. Their structures are dominated by the conspicuous LSm fold (see https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/entry/A0A370Q1D4, (accessed on 1 December 2025) or https://www.rcsb.org/structure/AF_AFA0A044URM1F1 (accessed on 1 December 2025), with the LSm-associated domain (LSmAD) also standing out in alpha-fold predictions, while most remaining Ataxin-2 is characterized by intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), where the linear PAM2 motif is usually embedded within the C-terminal half. The three successive domains—surrounded by IDRs and, in less than 5% of species, by extra domains of known function—are shown schematically in Figure 1a and are meticulously assessed in text paragraphs below.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the evolution of the Ataxin-2 protein family. (a) The structure of all members of the Ataxin-2 protein family contains an intrinsically disordered region 1 (IDR1, in yellow color) near the N-terminus, which may contain a polyQ domain, e.g., in primates, then an LSm domain with 5 beta-barrels flanked by an alpha-helix on each side (in blue color), after a spacer sequence followed by an LSm-Associated-Domain (LSmAD, in green color) with some alpha-helix structures, then IDR2 sometimes containing a polyQ domain, e.g., in insects, a linear PAM2 motif (purple color), IDR3 sometimes containing a polyQ domain, e.g., in mucorales fungi, and variant C-terminal sequences. The IDRs show poor sequence conservation across evolution (illustrated by hatched color). In less than 5% of Ataxin-2 orthologs, there are extra domains at the N-terminus or C-terminus (grey symbols) that are mostly functioning in membrane stress resistance or rRNA processing. (b) Ataxin-2 orthologs are not present in eubacteria, archebacteria, or glaucophytes that evolved before the great oxidation event in the atmosphere. Ataxin-2 orthologs are documented in their typical and complete structure since rhodophytes that exploited rising oxygen levels via endosymbiotic mitochondria and chloroplasts, while defending against oxidative stress by carotenoid pigments. (c) Whereas one gene copy of Ataxin-2 is sufficient in insects and nematodes, and is again sufficient for flying birds, during the process of terrestrialization two independent gene duplications were conserved: from conifers to mosses and flowering plants (named as CID3/CID4) on the one hand, and from chordate fish to ray-finned fish, amphibia, reptiles until mammals (named as ATXN2/ATXN2L) on the other hand. PolyQ domains near the N-terminus or near the C-terminus already existed in algae, are found frequently upstream from the PAM2 motif in insects, and have expanded steadily in the unusually long N-terminus of ATXN2 since amphibians. Created in BioRender. Key, J. (https://BioRender.com/8073e0f) (accessed on 8 December 2025) is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Many functional insights are known for two of the three highly conserved domains, but the third, least-studied domain was found to be characteristic of Ataxin-2:

- (1)

- Firstly, just after the ancestral N-terminus, the Like-SM (LSm) fold has a typical structure of small five-strand anti-parallel beta sheets (β1, β2, β3, β4, β5), with SH3-type barrel tertiary structure. The ancestral quaternary structure is characterized by assembly into an LSm hexameric or heptameric ring, with U-rich RNA oligonucleotides binding inside the LSm torus lumen. Overall, the LSm domain in human ATXN2 and ATXN2L (synthetic full-length entries UniProt Q99700 and Q8WWM7) comprises 78 amino acid residues. LSm domains have descended from bacterial proteins like Escherichia coli Hfq and YlxS, as well as archaeal Sm1/Sm2, which serve as RNA chaperones and in ribosomal pathways [77,78]. In eukaryotes, various Sm proteins in the nucleus form a heteroheptameric ring that is crucial for intron splicing [79]. Like-Sm proteins were subsequently also described in the cytoplasm, where LSM2-16 combine the RNA-binding sequence with a methyl-transferase domain [80,81], whereas Ataxin-2 combines the RNA-binding sequence with the LSmAD and the PAM2 motif [76,82]. Our datamining effort confirmed that the LSm sequence of Ataxin-2 has relevant similarity to the LSm domains of LSM2-16, so BlastP searches frequently confuse different families, and the sequence variability of the LSm domain is so strong in low organisms that current InterPro and Pfam algorithms fail to detect it in approximately one third of Ataxin-2 orthologs. The LSm/LSmAD region in Ataxin-2 binds to the RNA helicase DDX6 [64]. Together with the RNA helicase DDX6 and the LSm-containing factor LSM12, Ataxin-2 was found to influence circadian post-transcriptional regulation and olfactory habituation in fly neurons [83,84]. It is therefore important to note that an RNA helicase domain was chimerically added to Ataxin-2 orthologs in several species (see below for individual protein database entries).

- (2)

- Secondly, after a disordered bridge region of, usually, 50–60 amino acids, the LSmAD sequence stands out with a predicted alpha-fold structure. However, experimental analysis showed only a modest presence of α-helical structural elements, with a considerable degree of flexibility, devoid of tertiary structure and without RNA binding capacity [77]. Human Ataxin-2 LSmAD sequence (amino acids 409–477 in the synthetic full-length UniProt entry Q99700) contains a putative clathrin-mediated trans-Golgi signal (residues 414–416) and an ER exit signal (residues 426–428). Indeed, experimental analysis confirmed that the deletion of 42 residues within LSmAD causes Golgi dispersion [50]. Overall, the ancient protein module comprising LSm and LSmAD with their connecting bridge sequences extends across some 250 amino acid residues in a very stable size across evolution, while most length variability of Ataxin-2 orthologs is due to IDR composition and length across the C-terminal half and sometimes in short N-terminal regions. Here, it is important to note that our datamining effort found practically all LSmAD-containing sequences to represent Ataxin-2 orthologs, so the extremely well-conserved LSmAD domain is the unique characteristic feature of the Ataxin-2 family and is perfectly suited for the BlastP search for orthologs.

- (3)

- Thirdly, the 14-residues short linear motif known as PAM2 was named Poly(A)-binding protein interacting Motif 2. It connects to an MLLE sequence in the PABP C-terminus (also known as CTC, short for carboxy-terminal conserved domain), in dependence on nearby phosphorylation sites [62,78,79,80,81]. In plants, the PAM2 motif extends over 19 residues that contain a tandem duplicate of the core sequence [76]. Interestingly, its location is always outside globular domains [82], at approximately three-fifths of the protein length. It clearly functions to interact with mRNA 3′ tails, and it exists as a component of over a dozen different eukaryotic proteins [82], several of which are known for their regulation of mRNA translation versus decay [79]. These protein families include PAIP1/2, LARP4, eRF3/GSPT1/2, TTC3, USP10, PAN3, GW182, Tob1/2, and other factors, so our datamining effort found its usefulness for Ataxin-2 ortholog searches to be limited. Particularly in low organisms, the sequence variability of this motif makes its automated recognition by current InterPro and Pfam algorithms doubtful. The PAM2 motif was shown to prevent the phase separation of Ataxin-2 in cellular growth periods, while it localizes to the translation apparatus at the rough ER, promoting the relocation of Ataxin-2 to stress granules after cellular damage [55,56,83].

2.2. Compilation of Ataxin-2 Family Protein Sequences Until Excavata, Amoebozoa, and Algae

Conservation of Ataxin-2 sequences across evolution was used to judge the relevance of each domain and feature for physiology and pathology. Using the BlastP algorithm to search UniProt–UniParc, NCBI, and EMBL databases for ATXN2 homologs, the longest or otherwise relevant isoforms for many organisms are compiled in Table S1, but it was impossible in the current study to compile all isoforms and assess their genomic coding sequences. Separate tabs in this table show either an overview of the longest orthologs (Table S1A), or specifically the N-terminal intrinsically disordered domain 1 (IDR1) before the polyQ domain (Table S1B); sequences across the polyQ domain with its flanking residues and interrupting residues (Table S1C); the IDR1 sequences around and after the polyQ domain (Table S1D); structured sequences around and after the LSm motif (Table S1E); structured sequences around the LSmAD motif (Table S1F); the intrinsically disordered domain 2 (IDR2, Table S1G); sequences across the PAM2 motif within IDR2 (Table S1H); and ordered sequences before and after IDR3 with C-terminal variability (Table S1I). Some ATXN2L orthologs are compiled in Table S2. While this compilation cannot be exhaustive, it covers the main classes of eukaryotic organisms.

It is difficult to pinpoint the origin of Ataxin-2, given that precursors of Ataxin-2 in the databases cannot reliably be distinguished from fragmented Ataxin-2 due to sequencing problems, proteolysis, or isoforms. Furthermore, the absence of Ataxin-2 orthologs from species or organism classes may simply be due to incomplete sequence documentation, so only crude conclusions are possible. But as the prime result, Ataxin-2 orthologs were clearly identified in all eukaryotic kingdoms until amoebozoa, protozoa, and algae, but not in archaebacteria or eubacteria. Details are provided in the following paragraphs of this chapter.

Figure 1b depicts the evolution and domain structure of Ataxin-2 proteins in all kingdoms of life. Among amorphea–amoebozoa, Ataxin-2 homologs as in UniProt entries A0A151ZGE7 and Q55DE7 with 900–1100 aa in Dictyostelium are already complete with N-terminal polyQ stretches, LSm, LsmAD, and a typical PAM2 motif recognized by the InterPro or Pfam algorithms.

Among protozoa, Ataxin-2 homologs like A0A1Z5KDA2 and A0A9N8E681 with 700–900 aa in stramenopiles have this multi-domain structure and C-terminal polyQ stretches. It is noteworthy that the most ancient among them have chloroplasts surrounded by four membranes as a testimony to secondary endosymbiosis [84]. In phaeophytes (brown algae), as a photosynthetic class among stramenopiles, UniProt–UniParc entries A0A6H5L901, D7FVW6, and D7G1N4 in Ectocarpus species represent typical Ataxin-2 orthologs with short polyQ stretches upstream from LSm.

Interestingly, A0A0G4IZN6 with 400 aa in rhizaria contains a structured sequence not recognized as LSm by current algorithms, then LSmAD, IDRs with PAM2 embedded (PAM2 sequence takpkLNANAKTFT-MSAAAKEFV), but no polyQ stretch.

In naegleria from the excavata/discoba-schizopyrenida branch (that alternates between amoeboid and flagellate stages, having mitochondria with discoid cristae similar to Euglenozoa [85]), the UniProt entries A0A6A5CC11, A0AA88H5V6, and D2V0R5 with about 900 aa represent complete Ataxin-2 orthologs with N-terminal polyQ stretches.

In the closely related euglenozoan branch (the only photosynthetic branch among the excavata), smaller complete orthologs are documented. A0A0L1KIJ6 with >800 aa in Perkinsela shows a potential LSm coexisting with LSmAD and a primitive PAM2 motif (LNPNATAFLP) without polyQ stretches; A4H699 or A4HUM3 or Q4QHA3 in Leishmania (potential PAM2 precursor core sequence PNPSATPFVP), A0A1X0NQC5 in Trypanosoma (potential PAM2 core FNPAATPYTP), W6KMY5 in Phytomonas (potential PAM2 core PNPAAAPFVP), A0A0M9FU89 in Leptomonas (potential PAM2 core PNPSATPFVP), all with >500 aa, show an LSm and LSmAD coexisting with a C-terminus that contains several polyQ stretches. Trypanosomal A0A061J3B7 with 279 aa, and A0A0S4IS39 with 213 amino acids, show LSm and LSmAD coexisting without further elements. Given that trypanosomes were reported to have exchanged genetic material with green algae and other archaeplastida [86,87], orthologs of Ataxin-2 were studied in detail among algae.

Ataxin-2 orthologs are also documented among alveolata (A0A813ABV5 with >1100 aa that contain an extra 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase domain, with homology to bacterial SerA protein, which is essential for the biosynthesis of L-serine as precursor of phospholipids and sphingolipids). Among cryptista, one protein with significant LSmAD homology is documented (L1I7C3 with 522 aa).

In contrast, Ataxin-2 homologs appeared absent from the diplomonad and parabasalid–metamonad branches of excavata protists, which lack mitochondria, so these protists depend on nutrients and energy from hosts. In the monocercomonoides species from excavata, endosymbiont mitochondria were completely lost again [88], and an Ataxin-2 homolog could not be detected, while the microsporidia that lost mitochondria but retained mitosomes with FeS-metabolism-dependent oxidative stress [89] did preserve the presence of Ataxin-2 orthologs (e.g., A0A4Q9L9Z0 and A0A086J3B3). These findings support the concept that Ataxin-2 is needed to protect cells from the oxidative stress emanating from endosymbionts.

Among algae, many entries for Ataxin-2 orthologs exist from chlorophytes (green algae) with well above 1000 aa (e.g., A0A8J4CZB7 or A0A383VPF7) that contain LSm, LSmAD, polyQ stretches shortly after LSmAD, and typical PAM2 motifs embedded in the long C-terminal IDRs, as well as a short N-terminal IDR, in close structural and length similarity to human ATXN2L and ATXN2. In the particularly interesting green algae Cymbomonas tetramitiformis, whose ancestors are thought to have played a crucial role in the primary endosymbiosis of plastids [90], A0AAE0L4G1 is documented as a typical Ataxin-2 ortholog of 668 aa without polyQ stretch. Similarly, among archaeplastida–rhodophytes (red algae), the three entries A0A1X6NXA5, A0A5J4YT85, and A0A2V3IVX2 (noteworthy for a C-terminal uninterrupted 30Q repeat) represent Ataxin-2 orthologs.

However, no Ataxin-2 homologs were detected in glaucophytes (green-blue algae, which have plastids surrounded by an inner membrane containing a remaining peptidoglycan layer, suggesting they are still synthesized by plastids as by ancestral cyanobacteria; glaucophytes have mitochondria with the typical eukaryotic flat cristae surrounded by a double membrane and use asexual reproduction). They are considered the basal archaeplastida that engulfed cyanobacteria in an act of primary endosymbiosis within a terrestrial freshwater ecosystem [91,92,93,94,95]. Therefore, Ataxin-2 orthologs apparently were not needed for the engulfment of mitochondria or plastids. Instead, the appearance of Ataxin-2 might be associated with the gained ability to synthesize robust inner membranes by eukaryotes rather than by plastids. Apparent absence of Ataxin-2 homologs was also observed in the mesostigma branch of green algae, which contains primitive plate-like chloroplasts, lacking a periplastidal ER [96,97], and was therefore placed at the basis of divergence between chlorophyta (green algae) and streptophyta (land plants). This finding agrees with the notion that Ataxin-2 presence correlates with eukaryotic synthesis of organellar membranes.

Overall, the appearance of Ataxin-2 ancestors occurred only after glaucophytes had developed the endosymbiosis of mitochondria and after primary endosymbiosis of plastids (Figure 1b). Ataxin-2 ancestors are only documented since rhodophytes learnt to cope with the oxidative stress due to sun exposure and mitochondria/chloroplast presence [98]. Rhodophytes still have chloroplasts without external ER or unstacked (stroma) thylakoids, but developed α- and β-carotene (provitamin-A), lutein, and zeaxanthin as new antioxidative pigments [99], reproducing sexually, while lacking centrioles and flagella. Carotenoids play a basic role as membrane reinforcers in view of their rigid conjugated double-bond backbone as phylogenetic precursors of sterols [100,101]. When marine life forms subsequently moved to freshwater habitats and underwent terrestrialization, duplications of the Ataxin-2 gene occurred (Figure 1c).

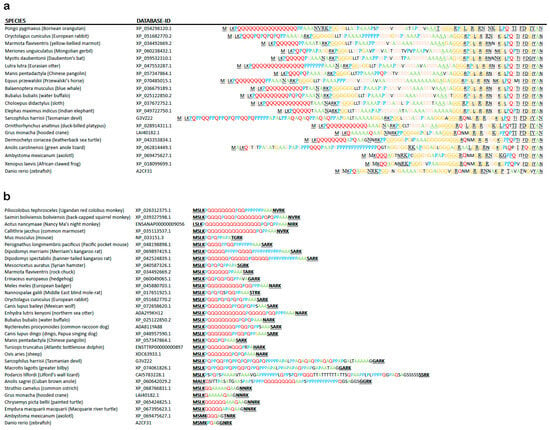

2.3. Gene Duplication ATXN2/ATXN2L in Animals, and CID3/CID4 in Plants, upon Entering Freshwater and Land

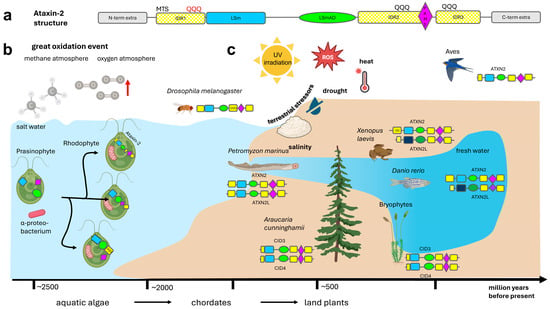

Datamining with STRING homology searches revealed that the gene duplication giving rise to two copies encoding land animal ATXN2 versus ATXN2L proteins is not only documented from mammals via Xenopus laevis to Danio rerio but is documented during earlier evolution until lampreys (UPI0014023775 vs. UPI001403D160 in Petromyzon marinus, UPI002AB6496F vs. UPI002AB6167E in Lethenteron reissneri) (Supplementary Material S1). Lampreys start life as larvae in freshwater, irrespective of whether they later live in coastal sea areas, rivers, or lakes. ATXN2 orthologs among fish species share more similarity with each other than with ATXN2L orthologs (Figure 2a), with specific residues being characteristic of ATXN2 versus ATXN2L (Figure 2b). The Pro vs. Ser difference at the beginning of the L3 sequence within the LSm fold would cause a bend in the peptide chain and possibly result in a beta-turn only in ATXN2 orthologs, whereas the Ser/Ala vs. Pro difference in the center of L5 may cause such a bend or beta-turn only in ATXN2L orthologs (Figure 2b). This suggests that different interactors and functions for ATXN2 versus ATXN2L have evolved. Thus, two copies of Ataxin-2 with differing point mutations are first detected in chordate lampreys as jawless fish that derive from the Devonian period, some 360 million years ago [102]. The gene duplication without distinguishing sequence variants may also be present in other chordates, like hagfish. Indeed, three rounds of genome duplication events are known to have occurred during fish evolution, one of them during the Devonian [103]. With many genes duplicated, chordates were enabled to develop notochords and neural tubes with dorsal versus ventral specifications, which are established via signaling with retinoic acid (a carotenoid vitamin-A derivative) to control homeobox expression and somite formation [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111], a pathway that establishes anterior–posterior gradients and is particularly a pathway for the development of the hindbrain, cerebellum, and spinal cord, which are affected most strongly in SCA2 and ALS [112].

Figure 2.

Duplication of the Ataxin-2 gene resulted in animal transcripts encoding ATXN2 versus ATXN2L, with characteristic differences in sequence and structure, while an independent duplication resulted in plant transcripts encoding CIDa versus CIDb, which co-evolved without consistent distinguishing features. (a) Guide tree of LSm domain evolution in fish generated by CLUSTAL Omega 1.2.4 Multiple Sequence Alignment software (accessed on 24 October 2025) shows single copy Ataxin-2 protein sequences (always with species name and database entry ID) in sea urchins, acorn worms, hagfish and early chordates (Branchiostoma), while other chordates (Petromyzon marinus, Lethenteron reissneri) already have two copies documented with point mutations, which remain typical and lead to the divergence of ATXN2 from ATXN2L in all descended species into two separate groups. We use the term Ataxin-2 when an organism has only one copy or to refer to the gene family, while ATXN2 or ATXN2L are used to distinguish between the two copies of a species that are encoded by the duplicated genes. (b) Fish ATXN2 versus ATXN2L sequence specificities, in red color if invariable, in italics if conserved in ATXN2 until human, showing the invariable sequences to correspond to linker regions between predicted alpha and beta structures, whereas the 5 beta sheets typical for LSm folds (depicted as arrows) and the surrounding alpha-helices (as zigzag lines) exhibit characteristic signature residues that differentiate ATXN2 vs. ATXN2L. (c) The guide tree of LSm sequences during plant terrestrialization shows single-copy Ataxin-2 orthologs, named CIDx, in green algae, mosses, liverworts, and duckweed, while double-copy Ataxin-2 orthologs (randomly dubbed CIDa or CIDb when there were no criteria to assign them to the CID3 group or the CID4 group) are documented since evergreen conifer trees and the earliest flowering plants that still bear tracheids. While the two copies in each species usually localize together or nearby, a big exception was observed for Amborella, which had one primitive copy closely related to Closterium algae and one sophisticated copy that exhibited sequences akin to flowering Rhododendron.

The question of whether ATXN2 or ATXN2L is the duplicated copy was assessed by genomics. The relevant human chromosome locus on 12q contains the gene order PPP1CC–CCDC63–MYL2–VHRT–CUX2–PHETA1–SH2B3–ATXN2–U7–BRAP–ACAD10–ALDH2–MAPKAPK5–TMEM116–ERP29–NAA25 (underlined genes share the same transcriptional direction; U7 refers to the 63 bp uridine-rich non-coding snRNA ENST00000607576.1, a potential binding target of Sm domains, which is positioned on the opposite strand downstream from polyQ-encoding exon 1 and upstream from exon 2 of human ATXN2 as the start of the LSm sequence encoding exon cluster), whereas the locus on 16p contains the gene order SULT1A1–NPIPB8–EIF3C–NPIPB9–ATXN2L–TUFM–SH2B1–ATP2A1–RABEP2–CD19, according to the human genome annotation in the UCSC genome browser. The synteny of ATXN2 with SH2B3, and of ATXN2L with SH2B1, is conserved since Nile tilapia fish. Before the gene duplication event, in fish such as Callorhinchus milii (elephant shark) or Oryzias latipes (medaka), the genome contains only the SH2B3–ATXN2–BRAP locus. It is tempting to speculate about a functional interaction of ATXN2 with SH2B3 and ATXN2L with SH2B1, given that all these proteins contain proline-rich motifs and associate with GRB2 during PI3K/AKT growth signaling at neuronal membranes [53,113,114,115,116]. Such a potential competition for GRB2 would be a relatively recent development during evolution, given that SH2B3 is not a neighbor gene of ATXN2 in the genomes of lancelet fish, D. melanogaster flies, or C. elegans nematodes, and is therefore not crucial for the ancient functions of Ataxin-2. However, it is conceivable that SH2B3, ATXN2, and BRAP are jointly relevant for human diseases such as SCA2, ALS, cancer, and longevity, either via their gene variants in linkage disequilibrium or via protein interactions [29,117,118]. Overall, ATXN2 clearly evolved from ancient Ataxin-2 in its original genomic context, while ATXN2L represents the duplicated copy in a new genomic environment.

ATXN2L is thought to be missing in birds. However, non-flying but feather-bearing kiwi birds in northern New Zealand have ATXN2 and ATXN2L entries in UniProt (Apteryx mantelli A0ABM4FEG3 and A0ABM4G1B9). Apparently, ATXN2L got lost before the evolution of flight, because ostriches, emu, and other kiwi species do not record ATXN2L sequences. It is known that large segmental deletions occurred when the macroevolution of avian genomes favored constrained size and became relatively static [119].

Among plants, two Ataxin-2 homologous gene copy translation products are not only documented in eudicot brassicales such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Q94AM9 vs. Q8L793) and Capsella rubella (R0HKF4 vs. R0GVL5) and other flowering land plants but also in paleodicots/ANA-grade angiosperms such as amborellales (U5D2G8 vs. U5D208 in Amborella trichopoda) and in gymnosperms such as conifers–araucariales (UPI0005EA7401 vs. UPI0005EA70B3 in Araucaria cunninghamii) (Supplementary Material S2). The ancestral angiosperms, like amborellales as well as gymnosperms, underwent enormous diversification after two whole genome duplication events since 319 million years ago during the late carboniferous period [120], which was possibly the ancestral event where CID3/CID4 appeared. While the Ataxin-2 orthologs in conifers still have >800 amino acids, similar to chlorophyte Ataxin-2 orthologs, CID3 and CID4 in flowering plants show a length of around 600 residues, consistent with the notion that some of their stress resistance properties were lost during evolution to flowering plants due to unusually short IDRs at either end of the proteins.

Conifers were the first trees among land plants. They are still the dominating plant species, e.g., in the taiga of Siberia, where they show exceptional resilience to winters with temperatures below the freezing point, managing to stay evergreen. Their cold hardiness involves the sensing of low temperatures and a short photoperiod to trigger molecular adaptations, such as (i) improved membrane fluidity, with the development of epicuticular wax (composed mainly of nonacosane, which is used as a component of paraffin, as a 29-carbon straight-chain alkane that is derived from very-long-chain fatty acids [121]); (ii) the mobilization of solutes such as glycogen to lower the freezing point and minimize cold shock of vulnerable RNA; and (iii) the downregulation of photosynthesis and cell growth in parallel to upregulated expression of cold-induced proteins [122].

Importantly, there are no specific residues that are characteristic of either CID3 or CID4. Instead, both proteins encoded by duplicated gene copies in each organism were more similar to each other than to the orthologs in other species (Figure 2c). Thus, they appear to have co-evolved in different organisms, adapting similarly to the changes of interactor molecules in dependence on various ecological niches. Apparently, both were conserved and remain expressed because a higher gene dosage was beneficial, but they did not assume different roles.

A curious exception to the high similarity of both Ataxin-2 orthologs within each species is observed in amborellales, where the protein encoded by one gene copy has a sequence with homology to flowering land plants. Amborellales are known to undergo extensive horizontal gene transfer from neighboring plants [123], and this might provide an explanation.

Overall, events that duplicated the Ataxin-2 gene occurred twice during macroevolution while moving out of marine life, with both duplications becoming conserved with independent fates. On the one hand, one event among chordates of shallow waters was inherited by land animals, resulting in ATXN2 versus ATXN2L proteins acquiring separate functions reflected by different protein lengths. On the other hand, another Ataxin-2 gene duplication occurred among conifers as early tree forms with unusual stress resilience, resulting in CID3 versus CID4, which lost some protein length and did not develop consistent distinguishing features. This is compatible with the notion that mechanical stress due to gravitational forces, more sunlight intensity, heat and cold exposure, and oxidative stress made it advantageous to have two gene copies when marine life forms underwent terrestrialization. The fact that flying birds lost the Ataxin-2 gene duplication might suggest that the higher weights of organismal bodies on land and the mechanical force of waves in shallow water require strengthened cell membranes. In contrast, life-forms that are suspended by buoyant forces in deep ocean water or in the air have less demand on membrane stability.

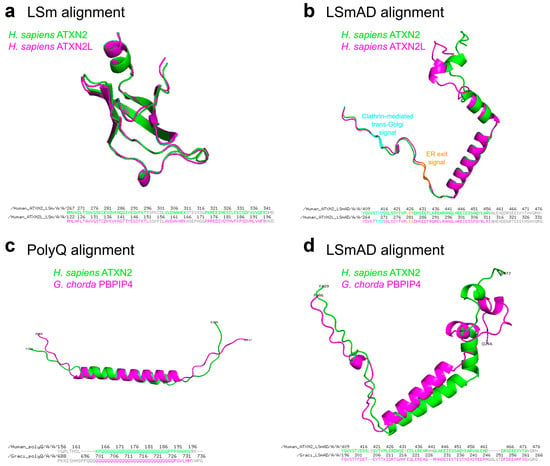

A comparison of the LSm and LSmAD sequences in human ATXN2 versus ATXN2L reveals very similar predicted structures, while pinpointing the putative crucial differences (Figure 3a,b). Additional comparison of the polyQ domain and the LSm domain in the human species versus their first appearance in the red alga Gracilariopsis chorda underlines the strong conservation of predicted structures and presumably also their functions (Figure 3c,d).

Figure 3.

(a,b) Structural alignment of LSm and LSmAD domains of human ATXN2 and ATXN2L. (a) LSm domains of ATXN2 (aa267–344) and ATXN2L (aa122–199) were extracted from the AlphaFold predicted structures (AF-Q99700-F1-v6 and AF-Q8WWM7-F1-v6, respectively) and aligned using PyMOL, version 3.1.0 (accessed on December 9, 2025). The amino acid sequences of the domains and aligned residues are presented below. (b) LSmAD domains of ATXN2 (aa409–477) and ATXN2L (aa264–333) were extracted from the AlphaFold predicted structures (AF-Q99700-F1-v6 and AF-Q8WWM7-F1-v6, respectively) and aligned using PyMOL. Clathrin-mediated trans-Golgi signal and ER exit signal within the LSmAD domain are marked in cyan and orange, respectively. The amino acid sequences of the domains and aligned residues are presented below. (c,d) Structural alignment of polyQ and LSmAD domains of human ATXN2 and its Gracilariopsis chorda ortholog, previously named polyadenylate-binding protein-interacting protein 4 (PBPIP4). (c) PolyQ domains of human ATXN2 (aa166–188) and G. chorda PBPIP4 (aa698–727) were extracted from the AlphaFold predicted structures (AF-Q99700-F1-v6 and AF-A0A2V3IVX2-F1-v6, respectively) and aligned using PyMOL. The amino acid sequences of the domains and aligned residues are presented below. (d) LSmAD domains of human ATXN2 (aa409–477) and G. chorda PBPIP4 (aa196–266) were extracted from the AlphaFold predicted structures (AF-Q99700-F1-v6 and AF-A0A2V3IVX2-F1-v6, respectively) and aligned using PyMOL. The amino acid sequences of the domains and aligned residues are presented below.

2.4. Genomic Comparison of Exon–Intron Structure for Human and Murine Ataxin-2 Versus Ataxin-2-like

Mapping of the individual exons within genomic sequences (as documented at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/6311, accessed on 15 August 2025) shows that human ATXN2L exons on chromosome 16 (Supplementary Material S3) stretch across 13,823 bp, with large blocks of non-coding sequences after exon 1, then (with the LSm domain encoded by exons 3–5) large non-coding blocks again after exon 6, then (with LSmAD encoded by exons 7–8) after exon 10, and again (with PAM2 motif encoded by exon 15) after the final exon 24B.

Human ATXN2 exons on chromosome 12 (previously studied in [124]) have a similar distribution overall (as shown at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/11273, accessed on 15 August 2025), but they are found across a >10-fold larger genomic area with 146,713 bp (Supplementary Material S4), suggesting that much more sophisticated control over expression and splicing of exon clusters has become possible. Massive blocks of non-coding sequences are found after exon 1 (where the polyQ repeat is encoded), then (with the LSm domain encoded by exons 3B–5) again after exon 5, a smaller block after exon 6, then (with LSmAD encoded by exons 7–8) smaller blocks each after constitutive exon 9, alternative exon 10, constitutive exon 11, and massive blocks again after exon 14 (encoding IDR2, with the PAM2 motif encoded by exon 16), exon 18A, exon 18B, exon 20, exon 21, and the final exon 25.

The extraordinary similarity of translation starts, aligned exon boundaries (Supplementary Material S5, employing CLUSTAL Omega 1.2.4), and the genomic clustering of several exons around the LSm, around the LSmAD, around the PAM2 motif, and the C-terminal intrinsically disordered sequences may reflect a joint regulation of these exon clusters and separate functions in common for each cluster.

In addition to the ancient conserved and aligned exons, human ATXN2 has developed alternative splicing at least for exons 1A, 1B, 2, 3A, 10, 21, 23B, and 25 ([124,125,126], UCSC genome browser, accessed on August 8, 2025). Clearly, the regulation of human ATXN2 appears much more sophisticated than ATXN2L, given that it shows many more genomic non-coding control sequences between exons, at least three alternative translation starts ([127], UniProt, NCBI protein database) within the extended N-terminus containing the expanded polyQ stretch, many options for alternative splicing, longer sequences encoded by exons 11 and 13, and a much more variable C-terminus. Further analysis of murine Atxn2 versus Atxn2l confirmed the strong adherence to exon boundaries but also documented several alternatively spliced exons for Atxn2l (Supplementary Material S5 [128,129]). The fact that Ataxin-2-like remained relatively unchanged during evolution, while Ataxin-2 underwent numerous adaptations to fine-tune its functions, indicates that human Ataxin-2 has acquired additional features and that SCA2/ALS pathogenesis involves diverse mechanisms, which are not necessarily modelled in lower organisms.

Importantly, the human ATXN2 sequence shows two methionine residues as potential start codons at the initial LSm sequence, and database entries confirm that corresponding isoforms are translated. Similarly, the initial LSm sequence of ATXN2L orthologs contains one or two methionine residues. While such an Ataxin-2 translation start right at LSm was normal in ancient species like Trypanosoma, Perkinsela, and other protists, and was still producing the main isoforms among reptiles (Table S1A), a short intrinsically disordered N-terminal extension with IDR1 became usual already among protists, fungi, worms, and insects. An extension of the N-terminal IDR1 occurred progressively for ATXN2 homologs since fish, with one methionine at the LSm start being lost. However, there is database evidence that a minor isoform that starts from the LSm domain has always existed from zebrafish to primates (Table S1D).

2.5. C-Terminal Fragment Isoforms Are Prominent According to Exon Expression Analyses, and C-Terminal Epitopes Are the Target of Most Current Commercial Antibodies

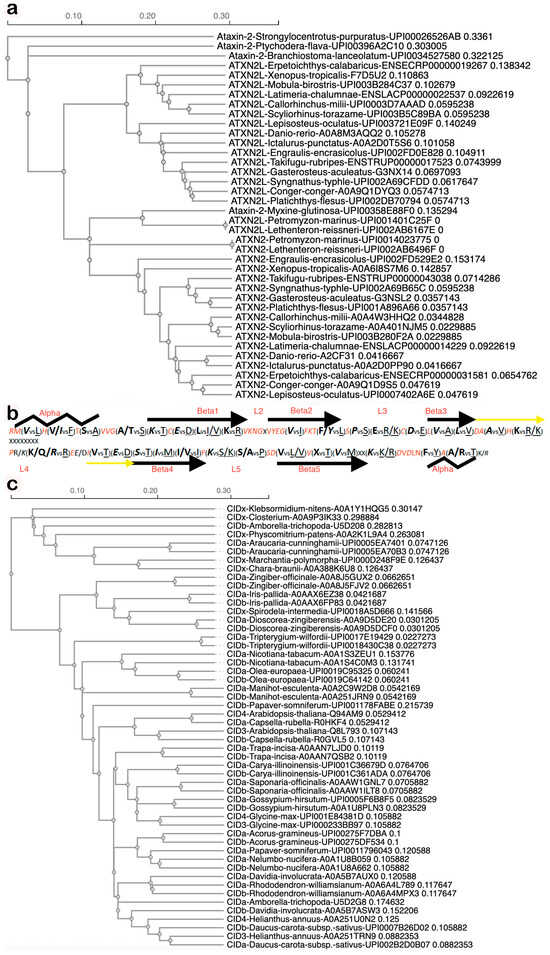

Interestingly, RNAseq-based analyses of individual exon expression strength in central nervous tissue (as documented at https://www.gtexportal.org/home/gene/ATXN2, accessed on 8 October 2025) reveal that the exons named 22, 23, 24A, and the C-term alternatively spliced final exon in Supplementary Material S6 have the highest scores (in spinal cord, 1.48 and 1.26, respectively, encoding C-terminal intrinsically disordered sequences with seven Met residues). Only about half of these maximum expression levels are observed for exon 15 (containing one Met), with scores at 0.644, and exons 16 (encoding PAM2), 17 (three Met), 18 (two Met), and 19 (three Met), with scores above 0.8. Less than a quarter of these maximum expression levels are found for exons 5–12 (around the LSmAD sequence, including one Met in exon 5 and six Met in exons 9–12), with scores above 0.407. Around a sixth of the maximum expression levels are apparent for exons 2–4 (encoding the LSm fold start, including two Met), with scores between 0.174 and 0.252. Particularly low expression at 3% of maximum levels is seen for exons 1A and 1B (encoding the N-terminal intrinsically disordered sequence and the polyQ domain, including two Met residues), with scores at 0.04.

Also, the GTEx Gene Model based on ENSEMBL-documented transcripts of human ATXN2 (as documented at https://www.gtexportal.org/home/gene/ATXN2, accessed on 8 October 2025) indicates the existence of many transcripts that comprise only the C-term disordered sequences or begin at sequences downstream from PAM2, from LSmAD, and from LSm. Transcripts encoding only the LSm domain are always combined with LSmAD, but transcripts encoding only the LSmAD domain (entry ENST00000471866.5) or the sequences between LSmAD and PAM2 (ENST00000546483.1) are documented. Overall, only half of the transcripts, including all alternatively spliced transcripts, span the length of the ATXN2 gene, a tenth spans only the N-terminal parts, while some 40% span across the C-terminal parts. The N-terminal parts seem less relevant than models of 3D-structure around the conspicuous LSm-fold would suggest, while the C-terminal intrinsically disordered sequences have a little-appreciated importance. Therefore, despite the notion of synthetic full-length Ataxin-2 being a multi-domain protein of >1300 residues, cells appear to have retained during evolution a great ability to use most of its modules selectively.

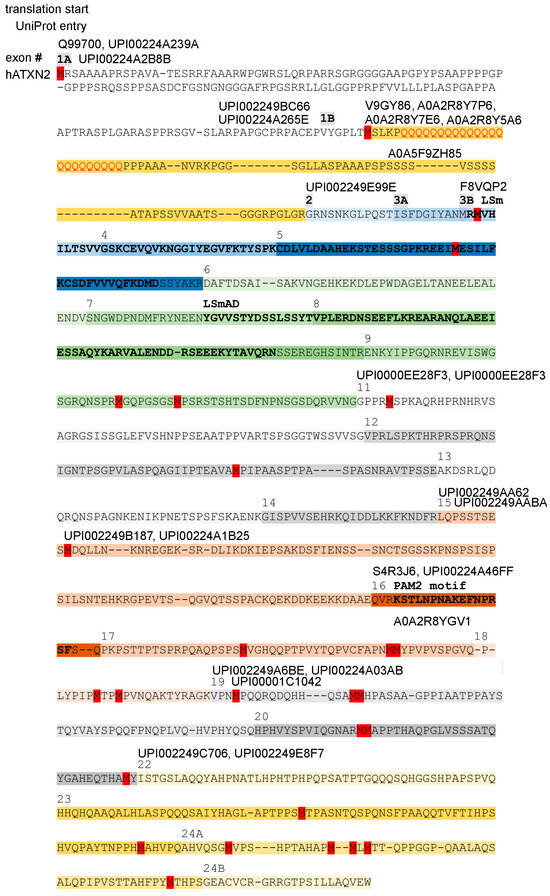

These transcript findings suggest that short protein isoforms may exist with a Met start codon in the center or towards the C-terminal end of human ATXN2, which were previously considered as partial sequence fragments. Indeed, database entry Q99700.2 reflects a translation start from the N-term disordered sequence, NP_002964.4 reflects a start from the polyQ-repeat, and NP_001297052.1 reflects a start from the LSm domain, but there are also entries like XP_059732367.1, where the start lies upstream from LSmAD; EAW97959.1-EAW97960.1-A0A2K6UG79-A0A8C5XNX2-A0A811ZS54-A0A8C4TUK8-A0A3S2PRM8-A0A3Q3N8E0-A0A3Q3FSG1-A0A672RDQ6, where the start lies downstream from LSmAD; A0A2K5CKD3, where the start occurs downstream from LSmAD but the PAM2 motif is selectively excluded; A0A7J8EWQ7/A0A7J7R7F2, where the start lies just upstream from PAM2; or A0A7J7S175-A0A7J8BWL6-A0A5F5Y0Q1-A0A212D9N5-A0A5N4C9F7-A0A5N4C9H8-A0A401TLV8, where the start is located downstream from PAM2. A schematic depiction of the human ATXN2 protein sequence with potential methionine start codons, isoform candidates with UniProt–UniParc database entries, and the encoding exon structure is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Multiple translation starts (methionine residues in red color), resulting in many long and short isoforms, are documented in protein databases. The scheme shows a version of human ATXN2 without the sequences encoded by alternatively spliced exons 10 and 21, corresponding to the alignment of human ATXN2 versus ATXN2L and murine ATXN2 versus ATXN2L in Supplementary Material S5. The coding of amino acids by individual exons is illustrated by different background color hues, with the exon number (#) indicated above the starting amino acid, highlighting the LSm and LSmAD domain as well as the PAM2 motif above the residues that stand out in bold letters. UniProt–UniParc database entry IDs are placed at different positions above the amino acid thread to indicate where each isoform of ATXN2 converges with the consensus sequence, while ignoring any isoform-specific start codon and downstream divergent amino acids that precede the constitutive ATXN2 fragments. The existence of multiple large and short isoforms of ATXN2 protein is supported by the analysis of mRNA isoforms (Figure S1) and by the molecular weight of bands detected in immunoblots by antibodies that target epitopes in the C-terminal half.

Commercial antibodies were often raised against full-length overexpressed Ataxin-2. However, in those cases where the companies used a fragment of Ataxin-2 as an immunogen and revealed the epitope residues, a bias towards the more abundantly expressed epitopes downstream from LSmAD is obvious. Few commercial antibodies exist against the expanded polyQ domain, against IDR1 sequences, against the region across LSm or LSmAD, and against the sequences between LSm and LSmAD, while most targeted antibodies detect immunogens downstream from LSmAD (Figure S1 depicts the relevant immunogens relative to the exon structure of isoforms according to GTEx database data). Reporting bias selects figures that represent the 120–130 kDa isoforms, while bands with smaller molecular weight are usually interpreted as unspecific cross-reactivity or are ignored. Thus, there is an important unmet need to study the C-terminal isoforms of ATXN2.

ATXN2 was reported to homo-dimerize or multimerize, and it is important to consider the fact that LSm-containing proteins assemble in homo-hexameric or homo-heptameric rings around RNA. Thus, these expression data would be compatible with a scenario where Ataxin-2 isoforms integrate into assemblies that are dominated by intrinsically disordered domains that promote RNP granule formation during microtubular transport. One sixth of the components would bear the LSm head that can be activated to bind a specific single-stranded AU-rich RNA sequence directly, and then mediate the association of a helicase to linearize the RNA, presumably in a stimulus-dependent manner at the end of transport, e.g., in a synapse before stimulus-dependent translation.

Given that the polyQ-encoding exon accounts for only 3% of maximum expression in the spinal cord, it seems plausible that there is a long temporal delay before polyQ-triggered accumulation and aggregation of N-terminal ATXN2 sequences become prominent in postmitotic neuronal tissue. In a mouse mutant with an ATXN2-Q100 expansion KnockIn, the levels of phosphopeptides from LSm to C-term in non-neuronal tissue are around 10% compared to WT [130], confirming that the expansion can lead to partial loss-of-function effects. However, in postmitotic neural tissue (the spinal cord) at 14 months of age, selectively, a phosphopeptide close to the polyQ-repeat before the LSm domain accumulates > 110-fold relative to WT, and a phosphopeptide in the isoform that starts 160 residues even further upstream at the N-terminus accumulates > 30-fold [131]. This suggests that either alternatively spliced expression of small isoforms or partial degradation via proteolysis is employed by cells, and the disease mechanisms in SCA2 and ALS do not necessarily concern the full-length protein. ATXN2-fragment-specific disease mechanisms should also be taken into account.

2.6. Most N-Terminal Start Codon with Subsequent Fragment Appears in Armadillo Only for ATXN2

As mentioned above, the analysis of the ATXN2 start codons in humans and closely related primates shows at least three different translation starts across the N-terminus for isoforms in Homo sapiens and four different isoforms in Pongo abelii, as well as Macaca nemestrina (Table S1A). The most N-terminal alternatively spliced sequence starts with M(X)R(PX)S/T(XX)A… and is clearly conserved with quite constant length from primates until artiodactyla, and according to one database entry, even in armadillos (Table S1B), suggesting that it has functional relevance. This N-terminal extension is not observed for ATXN2L, so its function is specific to ATXN2. It starts with a sequence that has a strong likelihood to act as a mitochondrial targeting signal (score of 0.9937 in MitoProt v1.101, with predicted cleavage site at residue 144; score of 0.75 at TPpred3 for residues 1–38), and then contains three proline-rich motifs (PRMs) at amino acid residues 55–71, 117–123, and 142–148 in human ATXN2 (Uni-Prot Q99700).

It is highly interesting that a duplication event of 21 base pairs was observed at the end of this exon 1A-encoded fragment, where human ATXN2 amino acid residues 145–151 get repeated in tandem (ARPA PGCPRPA PGCPRPA CEPV). This dup21 variant affects the last of the PRMs mentioned above. It was observed in a Japanese patient with a clinical, imaging, and electrophysiological phenotype of SCA2 who carried no CAG-repeat expansion in ATXN2, suggesting that this variant plays a pathogenic role. Recombinant ATXN2 protein with the dup21 variant showed clear aggregation tendency and caused reduced cellular viability upon transient transfection of a Schwann cell line. Even more interestingly, it triggered recognition of the normal polyQ domain length by the monoclonal 1C2 antibody as if it had the abnormal epitope characteristics of an expanded polyQ domain, so apparently, the proximity between the duplicated PRM and the polyQ domain leads to conformational changes in the ATXN2 N-terminus that seem pathognomonic [132].

Another duplication event of nine bases was reported more towards the N-terminus in this exon 1A-encoded fragment, where human ATXN2 amino acid residues 38–40 get repeated in tandem (PARR SGR SGR GGGG). This dup9 variant was observed in a small Swedish family where a father and his daughter were diagnosed with Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 3 (SCA3) due to polyQ-expansions in the ATXN3 disease protein. In both cases, the additional presence of the ATXN2 dup9 mutation was accompanied by unusually early disease manifestations and a Parkinsonian phenotype upon clinical, neuroimaging and neuropathology studies. Furthermore, this dup9 variant was also present in two patients diagnosed with the C9ORF72 type of ALS, appearing again to be associated with an unusually early age at onset and with Parkinsonian features. A bidirectional study of expression (ATXN2-S/AS) revealed significantly higher expression of this dup9 variant [133]. This potential impact of the dup9 variant on expression levels seems credible, given that a CpG island for promoter activity is situated within exon 1 of human ATXN2 [134].

Sequences with significant homology (BlastP score < 5 × 10−7) to this fragment are not found in ATXN2 orthologs among paenungulata and marsupialia but instead are contained in the SKI family transcriptional corepressor 1 (SKOR1), actin nucleation-promoting factor (WAS), and Splicing Factor 3B subunit (SF3B4) from Vombatus ursinus, Phasolarctos cinereus, and Monodelphis domestica. In humans, close homologies exist with sequences within Transcription initiation factor TFIID subunit 4 (TAF4, 1.1 × 10−9) and the Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich (SFPQ, 7.8 × 10−8), and also with proline-rich protein 36 (PRR36, 4.6 × 10−8), Formin-2 (FMN2, 2.1 × 10−7), and actin-binding protein WASF2 (8.5 × 10−7).

Structural prediction software in InterPro characterizes this sequence as an intrinsically disordered region (IDR) with low complexity and proline-rich stretches, and the previous literature has named all sequences upstream from the LSm domain as IDR1 of ATXN2 [62]. Thus, the above observations are in agreement with a genome-wide survey concluding that Pro-rich sequences are involved in actin/cytoskeletal-associated functions, RNA splicing/turnover, DNA binding/transcription, and cell signaling [135,136]. At the N-terminus, this proline-rich sequence may influence the folding of nascent ATXN2. Its presence in recombinant full-length ATXN2 constructs for in vitro experiments, as well as the absence of such N-terminal sequences from ATXN2-null organisms, may have contributed to reports that ATXN2 is involved in actin–plastin pathways and in actin–endocytosis pathways [52,53,57,58,137]. However, the effects of Ataxin-2 on mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, and oxidative stress responses cannot be attributed only to this IDR1, given that such an impact is already documented in the yeast ortholog Pbp1p (subsequently referred to as PBP1) [67,68,69,70,138,139,140,141].

2.7. The Usual Start Codon in Human ATXN2/ATXN2L Is Followed by polyQ and a Repeat-Rich Fragment, Which Elongates Since Yeast/Insects

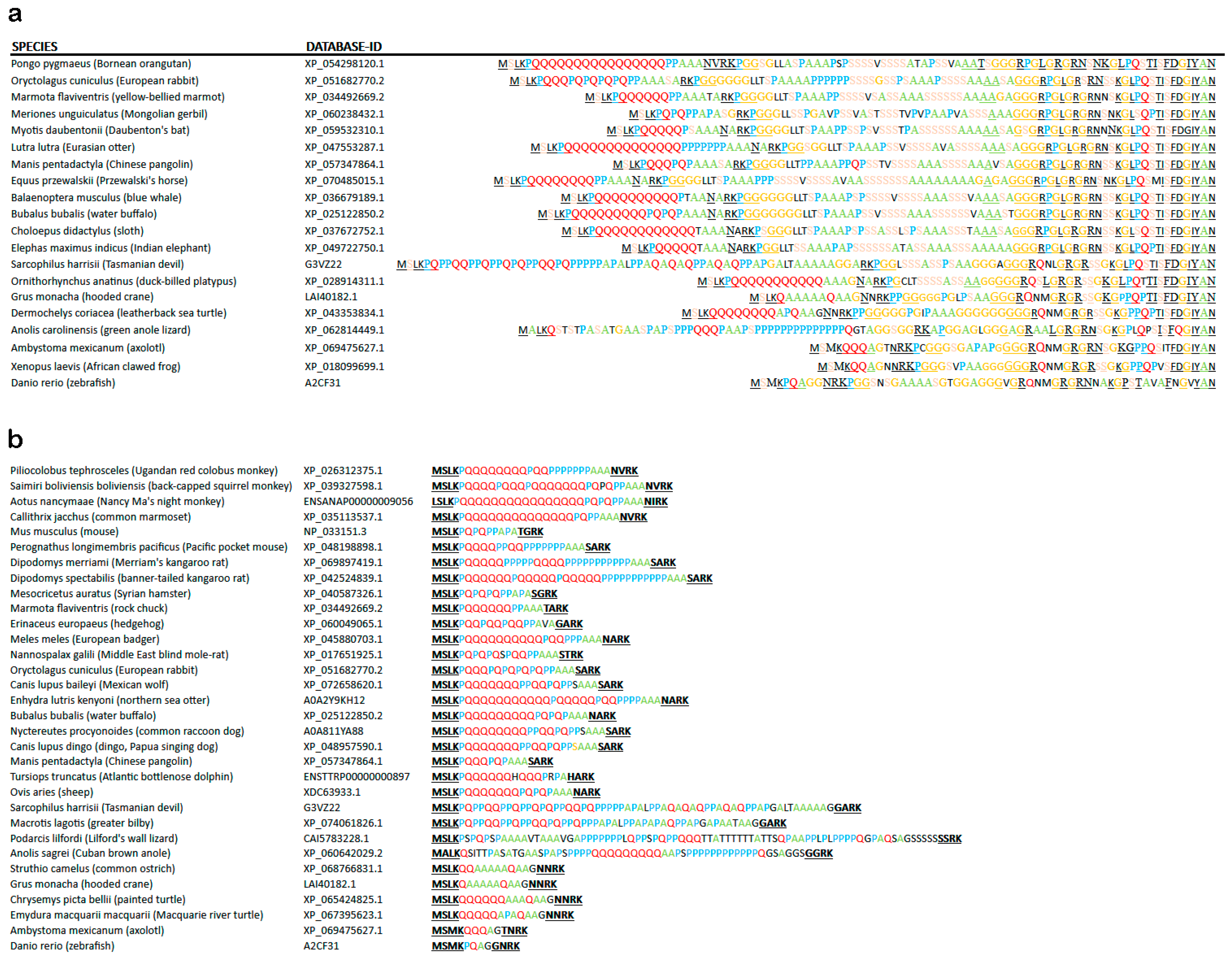

The second alternatively spliced exon in ATXN2 encodes the highly conserved translation start sequence MS(L/M)K(P)n(Q)n(P)n to produce an additional N-terminal fragment of up to 50–120 aa that contains several repeats, namely polyQ, polyPro, polyAla, polyGly and polySer, with one or several prolines usually at each side of the polyQ repeat. Within this sequence downstream from the polyQ repeat and before the polySer repeat, 17 amino acid residues enable N-terminal proteolysis of mammalian ATXN2 [142]. The entry A0A2K5X824 in Macaca nemestrina suggests that an alternative start sequence MGPHHVAEAP(A)nT(A)n can also be used, producing a fragment that contains a polyA repeat instead of the polyQ repeat. This fragment immediately before the LSm domain start does not show a relatively constant length, in contrast to the previous paragraph, but instead shows a massive extension across phylogenesis. A close inspection of the sequences compiled in Table S1D reveals the repeated appearance of polyQ repeats in testudines, again in monotremata, in proboscidea, and in primates. Instead of an N-terminal mammalian polyQ-repeat (MSLKPQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQPPAAA), which is found in primate monkeys (XP_054298120.1), birds and reptiles show polyAla (MSLKQAAAAAQAA in Struthio camelus, see entry XP_068766831.1), which seems to fulfil an analogous function [143] (Figure 5a). Both repeat types are known for their pathogenic expansion in patients [144,145]. PolyAla and polyGly repeats are found at each side of the fragment. In the center, a polySer repeat without or with interruptions has appeared with increasing size since monotremata. Around the first 100 amino acid residues of the human sequence are predicted to have an intrinsically disordered structure. The fact that this fragment extends in length since yeast/insects together with its poor conservation of individual amino acid residues may suggest that several repeats function as spacers between domains that interact, e.g., during autoregulation.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the N-terminal IDR1 of ATXN2 (encoded by exons 1B, 2, and 3) with multiple repeat structures since ray-finned fish. (a) Noticeable length extension is documented, with the human sequence being too long to be included. While the sequences encoded by exons 2 and 3A were quite conserved, and the MS(M/L)K(P/Q) motif downstream from the translation start remained stable, a lengthening of polyQ (in red letters), polyP (blue letters), polyA (green), polyG (orange), and polyS (pink) domains is apparent since turtles, reptiles, and marsupials (see also Table S1A). The polyQ repeat, whose expansion is pathogenic in the human disorders SCA2 and ALS13, has sizes of n ≥ 3 since axolotl amphibia, n ≥ 5 since turtles and other reptiles, n ≥ 10 since Platypus and Dasypus (armadillo) mammals, n ≥ 15 since carnivores and bats, and n ≥ 20 since primates. Conserved sequence patterns were underlined for easy visibility. (b) Non-random preference for Pro and Ala as interrupting residues or flanking residues across the polyQ domain. PolyA repeats arose next to polyQ in turtles, and substituted for polyQ in flying birds, while polyP repeats were intermingled with polyQ and polyA in lizards. Pro residues came to flank the polyQ repeat and to replace residues within the polyQ repeat since marsupials like the Tasmanian devil or the greater bilby. Thus, Pro and Ala residues appear to be exchangeable with Glu residues, with the physiological function of this IDR1 within ATXN2 remaining intact.

The N-terminal fragment before the LSm domain in ATXN2L, in comparison, has only doubled in length since Danio rerio and contains only short repeats without much variation. It starts since Xenopus with the conserved sequence M(L/S)(K/M)(P/Q/K)(Q/P)(P/Q). About the first fifty amino acids of human ATXN2L are predicted to show an intrinsically disordered structure. The total length of IDR1 sequences upstream from the LSm domain reaches 250 aa residues in human ATXN2L.

In contrast to previous assertions that long polyQ domains in N-terminal ATXN2 are exclusively found in primates, this datamining effort also observed ATXN2 orthologs with a Q > 5 domain in flying lemur, pika, rodents such as hamster/beaver/kangaroo rat, bats, carnivores, horses, unpaired and paired ungulates, armadillo, sloth, aardvark, duck-billed platypus, alligator, and leatherback sea turtle.

In human ATXN2 (UniProt Q99700), the InterPro sequence analysis shows the polyQ repeat at residues 166–188 to have a high alpha-fold confidence, and the aa residues 156–202 (YGPLTMSLKPQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQQPPPAAANVRKPGGS), especially the residues downstream from the polyQ repeat, to display significant homology with the beta-sandwich domain in Sec23/24. The Sec23/24 heterodimer regulates the trafficking of membrane proteins, phospholipids, sphingolipids, and sterols via COPII-coated vesicles from the ER to the Golgi apparatus and to elongating cell protrusions [146]. This homology is not detected by the InterPro algorithm in other species. A fly dATX2 isoform indeed colocalizes with Sec23, but this was reported for isoform C, which starts from the LSm domain, similar to isoform A, but no Sec23 colocalization was found for isoform B, which starts 60 aa before the LSm domain begins [147]. While it remains unclear if Sec23 is relevant in this context, human ATXN2 indeed associates with the ER, the disruption of Ataxin-2 in flies and nematodes disrupts ER dynamics, and the polyQ-expansion in human and mouse ATXN2, as well as the deletion of mouse ATXN2, leads to disturbed sterol and sphingolipid homeostasis [51,54,55,137,147,148,149,150]. To what degree N-terminal sequences of Ataxin-2 contribute to these effects remains to be elucidated.

The pathogenic expansion of the polyQ repeat within this translation start sequence to sizes ≥ 33Q is the monogenic cause of autosomal dominant SCA2, and at sizes 31 < (Q)n < 33, it contributes in a polygenic manner to the risk of sporadic ALS. It is interesting to note here that despite this long-term neurotoxicity of >31Q stretches, long polyQ repeats appear among ATXN2 orthologs initially towards the C-terminus already in single-cell organisms like red algae (UniProt A0A2V3IVX2), amoebozoa (Q55DE7), and dinoflagellates (A0A813ABV5, where an extremely long 73Q repeat is interrupted at three positions by single Met residues, or A0AA36IYW2, where a 41Q repeat is interrupted at 11 positions by single or double Ala residues), as well as insects like Hymenoptera (A0A158NW33, A0A836FT30, F4X2F6, A0A834JVP6, A0A834JR87), so they seem to play a relevant role for the functions of Ataxin-2 but are not documented for ATXN2L orthologs so far. Smaller polyQ repeat sizes 5 < (Q)n ≤ 31 are frequent among Ataxin-2 homologs towards the C-terminus (e.g., in chlorophytes such as A0A835VQM0, A0A9W6BKV0, nematodes such as MCP9264076.1, or insects such as Q8SWR8).

After this repeat-rich fragment but before the LSm domain, a connecting sequence is encoded by exons 2 and 3A in ATXN2 (for ATXN2L encoded by exon 2 and the first nine residues from exon 3), which appears in isoforms initiated from the first or second translation start codon and should therefore be regulated with exon 1B. However, their respective exons are separated genomically from exon 1, clustering instead with the subsequent exons that encode the LSm domain, possibly suggesting that this sequence may be regulated as an LSm modifier.

2.8. The Role of Proline Flanking Residues and Interrupting Residues for the polyQ Repeat

The observation that the pathogenic N-terminal polyQ repeat of ATXN2-IDR1 is adjacent to, or framed by, polyPro repeats or Pro residues (Figure 5b) is also documented for the pathogenic polyQ expansions in Huntington’s disease [151]. Whereas PRMs are thought to require the presence of an Arg residue for their interactions with actin and endocytosis apparatus, the polyPro residues or Pro residues at the flanks or within polyQ repeats may play different roles. Pro residues are thought to modulate the poorly solvent polyQ stretch towards an α-helix secondary structure [152] as well as mediating interactions, e.g., with SH3 domains [153,154] and with membrane lipid bilayers [155]. The presence of polyPro helices in the intrinsically disordered N-terminal domain of human CPEB3 was shown to modulate solubility, acting as an amyloid breaker [156]. Importantly, proline- or glutamine-rich activation domains are a common feature of transcription factors [157], so in the case of cytoplasmic Ataxin-2 orthologs, it is plausible that these sequences influence the binding to RNA.

Prolines not only serve a role in flanking the polyQ repeat. They are also frequently used to interrupt the polyQ domain. The interspersion of prolines or polyPro sequences within the polyQ repeat is observed not only in primates and some rodentia but also in lagomorpha, pholidota, artiodactyla, marsupiala, and squamata (Table S1C). Detailed studies of Ataxin-2 orthologs with amino acid residues interrupting its polyQ domain indicate that Pro >>> His >> Ala > Met = Arg = Ser = Gly are most used to interrupt polyQ stretches. The flanking residue on the left side is most frequently Pro >> His > Met = Lys = Gly = Val = Ala = Arg, while the flanking residue on the right side is more often Pro >>> Met = Arg = His > Ala = Asp = Glu = Gly. Overall, the amino acid residues that flank and interrupt the polyQ domain are non-random. Flanking (poly)Pro or interrupting Pro was the most frequent feature throughout the evolution of Ataxin-2 orthologs.

2.9. Ancient Start Codon Preceding LSm Domain as an Optional Third Start in Human ATXN2

The optional third translation starting immediately upstream from LSm was in very frequent use during evolution until reptiles and is still documented in primates. The first of two methionine residues that may serve as a start codon in exon 3B was lost in muridae and cricetidae among rodentia, together with insectivora (VRMVHILTSVV… instead of MRMVHILTSVV…), but lagomorpha, dermoptera, and primates still have this first methionine (see Table S1E). Here, an isoform with abundant expression in spinocerebellar tissue can be produced that corresponds to Ataxin-2 from LSm until the C-terminus, without the appended N-terminus. This very ancient translation start codon produces an isoform with all core ATXN2 sequences (e.g., in XP_067991570.1). Deletion experiments in Drosophila melanogaster indicated that the LSm domain stimulates mRNA translation. At the same time, it antagonizes the assembly of ribonucleoprotein granules [83]. Via RNA binding, the LSm domain influences the assembly and stability of microtubules in Drosophila melanogaster neurites [63].

The crucial residues, with high conservation rate in the LSm domain of ATXN2 from mammals to insects, versus ATXN2L from mammals to amphibians, are compiled in Figure 2a,b. The LSm sequence variation in Ataxin-2 orthologs from nematodes to single-cell organisms is extensive, with insertions at various sites, so that multiple sequence alignments have difficulty defining core amino acids. It is worth noting again that the LSm sequence has limited usefulness in identifying Ataxin-2 orthologs, while the consensus LSmAD across evolution (and IDR2/IDR3 within organism phyla) is much more powerful. Indeed, BlastP searches with the latter consensus sequences among fungi identify more than half of Ataxin-2 orthologs that have no recognized LSm domain, suggesting that the algorithms employed by InterPro and Pfam to identify LSm-folds need to be optimized. It is unlikely that the LSm-fold acts as a commodity rather than a necessity for Ataxin-2 functions, given that interference with this LSm domain is embryonically lethal.

The LSm domain, as an ancient RNA-binding motif with oligo(U)-specificity [158,159], is known to derive from Hfq protein homologs in bacteria/archaea, where it assembles in homoheptameric rings and performs RNA chaperone functions [160]. Hfq-binding RNAs were experimentally identified in Salmonella typhimurium bacteria, share a similar structure composed of three stem-loops, are enriched in the interacting sequence motif 5′-AAYAAYAA-3′, and show Hfq-association at AU-rich single-strand sequences adjacent to the loops, or the polyU end of sRNAs [161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171]. Hfq interacts with regulatory short RNAs, modulates RNA decay, acts in ribosome biogenesis, and influences mRNA translation, showing localizations in the cytoplasm, in the nucleoid, and at the bacterial cell membrane [172,173,174,175]. Importantly, the loss of Hfq causes increased membrane permeability and more sensitivity to oxidative stress, activating envelope stress responses via the sigma transcription factor RpoS for envelope stress [172,176,177,178,179,180,181], as well as leading to the activation of outer membrane proteins, enzymes, and transporters, which are involved in amino acid uptake and biosynthesis, sugar uptake / metabolism, and cell energetics [172,180,182].

Hfq homologs were adapted in eukaryotic nuclei as Sm modules in the heteroheptameric ring of splice proteins, and in eukaryotic cytoplasm in more than a dozen proteins implicated in RNA processing or decay, translation control, the telomerase RNA biogenesis, cell signaling, and gametogenesis [183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194]. Outside of ring structures, the LSm domain exists, e.g., in LSM11 as a factor associated with the methylosome [195] or LSM12 as a possible methyltransferase and/or NAADP receptor [192,196]. Thus, the LSm-fold sequence consensus is not specific for Ataxin-2 orthologs. However, the LSm domain still associates preferentially with AU-rich sequences, usually in the 3′ untranslated region of mRNAs [197].

2.10. RNA Processing Factors May Bind to the LSm-LSmAD Region, or Be Added to N/C-Termini of Ataxin-2 Orthologs, in Dependence on the Biochemical Needs of Different Ecological Niches

The region including the LSm and the LSmAD sequence contains around 250 residues, and in mammalian ATXN2, it was observed to mediate binding to the RNA helicase DDX6 [64,198] and to repress the illegitimate RAN translation of the CAG-repeat [199]. It is therefore interesting that Coptotermes formosanus termites show a N-terminal stable addition of a DEAD box RNA helicase domain (DDX52 homologous) to their Ataxin-2 ortholog (UniProt entry A0A6L2P9Q7), Trichogramma brassicae wasps have a C-terminal addition of a DEAD box helicase (A0A6H5ISX2), and Coemansia sp. fungi have a C-terminal addition of an RNA recognition motif (A0A9W7Z4B9) (see Table S3). These observations support the concept that eukaryotic organisms have optimized multi-domain proteins in order to concentrate all cofactors and substrates of a pathway in one place, thus maximizing throughput efficiency.

In analogy, further RNA processing functions that complement Ataxin-2 roles may have been integrated into its multi-domain structure, to ensure the maximal efficiency needed for different environmental stresses. Observations of various domains added at the N- or C-terminus of Ataxin-2 orthologs are therefore compiled in Table S3.

A C-terminal addition of a sequence with homology to HhH-GPD domains, like NTH1, occurred in Rhodotorula sp. CCFEE 5036 fungus (A0A4U0VMY8). HhH-GPD, like NTH1, recognizes and repairs 8-oxoguanine and other oxidative damage in DNA [200,201].

N-terminal addition of a tetratricopeptide domain plus a SAM-dependent 23S rRNA methyltransferase domain in Paramicrosporidium saccamoebae fungus (A0A2H9TMQ1), only an N-terminal 23S rRNA methyltransferase domain in Actinomortierella ambigua fungus (KAF9164688.1), or C-terminal addition of a 28S rRNA (cytosine-C5)-methyltransferase domain in Pseudozyma flocculosa fungus (A0A5C3F1S9) and a C-terminal SAM-dependent RNA (cytosine-C5)-methyltransferase domain in Wallemia ichthyophaga fungus (A0A4T0IZQ6) to the Ataxin-2 sequence provide further support for the relevance of this pathway. Tetratricopeptide repeat contacts bind RNA and assemble the splice apparatus [202], while eukaryotic 5-methylcytosine (m5C) RNA methyltransferases are crucial for responses to oxidative stress [203,204].

Similarly, the N-terminal addition of ribosomal protein L9 N-terminal and C-terminal domains to the Ataxin-2 sequence in Coemansia interrupta fungus (A0A9W8LDP4), Coemansia spiralis fungus (A0A9W8GBK0), Coemansia biformis fungus (A0A9W8CWC1), and Coemansia pectinata fungus (A0A9W8H1X6) underlines this concept.

A ribonuclease inhibitor LRR repeat was added to the Ataxin-2 ortholog of Rhizoctonia solani fungi (A0A074SQD8) and of Ceratobasidium sp. fungi (A0A8H8MCZ2). The ribonuclease inhibitor serves to constrain the cytotoxicity of RNase A [205].

Regulation of the RNA polymerase was achieved by the addition of a CBF-B/NF-YA transcription factor domain in Rhododendron giersonianum shrub (A0AAV6I6Y5), or by the addition of an ACID domain of the MED25 complex in Certonardoa semiregularis sea stars (UPI001FC18B4E) to their Ataxin-2 orthologs. The MED25 complex regulates RNA polymerase via transcription modulators such as MYC [206].

The chimeric C-terminal addition of a RIO2 kinase domain in the bony fish Anabarilius grahami to the Ataxin-2 ortholog (ROL51429.1) points to rRNA processing, given that yeast RIO2 is required for the final endonucleolytic cleavage of 20S pre-rRNA at site D in the cytoplasm, converting it into the mature 18S rRNA [207]. The human ortholog RIOK2 also modulates neurotoxicity in mitochondrial complex I deficiency. In addition, it modulates ageing via telomere shortening [208,209]. It is important to note here that the RIOK2 gene has been genomically localized next to the ATXN2 gene since bony fish.

As further evidence that Ataxin-2 acts in RNA surveillance pathways, an N-terminal addition of a BRAP2 signature with an RNA-binding RRM motif, followed by a C3H2C3-type RING-H2 finger and a UBP-type zinc finger, occurred in the Ataxin-2 ortholog from Pituophis catenifer snake (XP_070807217.1). BRAP2 regulates cell survival via the antioxidant transcription factor NRF2 (SKN-1 in nematodes) and via the DNA repair factor BRCA1 [210,211,212]. Again, it is noteworthy that the BRAP gene is the next neighbor of the ATXN2 gene upstream from its translation start on chromosome 12q in the human genome.

Only a HECT-type E3 ubiquitin transferase domain was added to the N-terminus of Ataxin-2 in Furculomyces boomerangus fungus (A0A2T9YUP5), implicating this ortholog in protein degradation pathways.

Despite current concepts that Ataxin-2 family members impact RNA processing mostly for mRNA transcript turnover with a poly(A)-tail via the PAM2 motif, the chimeric extra domains added to Ataxin-2 are clearly enriched for rRNA processing functions like methylation, rather than for mRNA decay versus repair management. Thus, this protein family appears to contribute to adaptations of the translation machinery after oxidative stress, with the LSm domain providing direct binding to RNA, while the variation in LSm sequences between orthologs and paralogs may relate to differences in the target sequence.

However, the structured Ataxin-2 sequences from LSm to LSmAD are not only important for RNA processing and quality control. Observations in Drosophila melanogaster show that Ataxin-2, but not its intrinsically disordered sequences, is crucial for the pathfinding of neurites in vivo [213], and, interestingly, these roles of Ataxin-2 were also fine-tuned by chimeric extra domains in some species.

2.11. LSmAD Became the Hallmark of Ataxin-2 in Rhodophytes and Protists

The LSmAD sequence of ATXN2 in Homo sapiens is encoded by exons 7 and 8, with genomic clustering suggesting that exons 6 and 9 are co-regulated with LSmAD.

The LSmAD sequence is unique and is the hallmark for the Ataxin-2 protein family, in contrast to the LSm domain that also exists in the LSM1-16 protein family for each species and in contrast to the PAM2 motif that also occurs in PAIP1/2, LARP4, eRF3/GSPT1/2, TTC3, USP10, PAN3, GW182, Tob1/2 and in other factors across the diverse species [214,215]. Since the presence of an LSmAD sequence defines the Ataxin-2 family, it is very unfortunate that there are no insights into the LSmAD functions or into the molecular interaction partners of LSmAD. Regarding the interaction of LSm with target mRNAs, the LSmAD sequence has an enhancing role in Drosophila melanogaster brains [216], and indeed, it was shown to modulate LSm conformation [77]. Interestingly, it was also reported that LSmAD mediates the localization of ATXN2 to the Golgi apparatus [50]. Luckily, LSmAD is highly conserved in sequence and length across evolution, so it is uniquely helpful to identify orthologs of Ataxin-2. Using BlastP to search for homologs of yeast PBP1-LSmAD (FGVKSTFDEHLYTTKINKDDPNYSKRLQEAERIAKEESQGTSGNIHIAE-DRGIIIDDSGLDEEDLYSGVDRR) among single-cell organisms, nothing significant was detected in bacteria and archaea. The LSmAD sequence was also not detected in ciliate/flagellate parasites except Trypanosoma and Plasmodium (both adapted to oxidative stress environments like blood cells), and already in rhodophytes and chlorophytes. However, among eukaryotic protists, plants, and animals, many orthologs were found with high significance (BlastP score < 1 × 10-10) and compiled in Table S1F. Thus, the LSmAD sequence appeared only in species with multi-domain proteins involved in stress responses that evolved to counteract oxidative damage due to the endosymbiosis of mitochondria and chloroplasts and due to exposure to sunlight.

Regarding crucial amino acids within this domain, it was reported that LSmAD contains a clathrin-mediated trans-Golgi signal (YDS, amino acid 414–416 in human ATXN2) and an endoplasmic reticulum exit signal (ERD, amino acid 426–428 in human ATXN2) [49]. However, the experimental evidence for their functional role was never unequivocal, with both not being well conserved in ATXN2, and ERD not being well conserved in ATXN2L either, despite the LSmAD sequence showing astonishing conservation since protists (Table S1F).

In view of this strong homology among LSmAD sequences throughout evolution (see Table S1F), we used them in extensive BlastP searches to define Ataxin-2 orthologs with unusual length (>1000 residues) that contain further protein domains of known function. The findings are reported in the last paragraphs of the Results text. It is relevant to know that many LSmAD-containing factors among chlorophytes were named CTC-interacting domain (CID) proteins, which refers to the presence of a PAM2 motif and its interaction with PAB1-binding protein (the MLLE domain of poly(A)-binding proteins was previously known as CTC domain) [217].

2.12. Sequence After LSmAD, Including the PAM2 Motif, Has a Polyampholytic Intrinsically Disordered Structure and Is Modified by Alternatively Spliced Exons Ante-10 and 10 in Human ATXN2