Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become one of the most important medical challenges today, affecting approximately 850 million people worldwide [1,2,3]. Furthermore, CKD is responsible for a disproportionate morbidity (cardiovascular disease and frailty) and premature mortality compared with other diseases. Despite improvements in patient care and risk factor management, many patients with CKD still progress to kidney failure [3,4,5,6]. CKD is complex due to the interaction of molecular, metabolic, inflammatory, and genetic factors. The purpose of this Special Issue, titled “Molecular Mechanisms and Regulation of Chronic Kidney Diseases,” was to gather high-quality articles that explore the pathogenesis of CKD from intracellular signaling to systemic metabolic crosstalk and genetic susceptibility, while also identifying opportunities for the early identification and treatment of CKD. The articles published in this Special Issue demonstrate that nephrology is currently moving from a descriptive pathology approach to a more mechanistically based precision- or target-oriented approach.

In current CKD research, dysregulation of intracellular signaling pathways has been identified as a major contributor to renal cell fate, their ability to adapt to stress, and their capacity for maladaptive repair. A key example is the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway. Delrue et al. provided a comprehensive overview of how compartmentalized cAMP signaling regulates renal epithelial transport, mitochondrial dynamics, inflammatory signaling, and fibrotic responses [7]. The cAMP pathway is now recognized as an intricate signaling network that requires precise spatial organization to optimize biochemical effects on target cells. Otherwise, the activity of these signaling molecules may be significantly attenuated or functionally ineffective. Recent developments suggest that localized phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity and anchoring proteins (AKAPs) exist within each microdomain, determining cAMP distribution within the cell. These two factors work together to produce a range of downstream signaling effects that can lead to physiologically relevant changes through both protein kinase A (PKA) and Epac [8,9,10]. Emerging evidence suggests that disruption of the microdomain structure can lead to tubulointerstitial fibrosis, polycystic kidney disease, and reduced stress response capability in tubular epithelial cells [11,12]. The authors’ view reflects a general shift in our understanding of newer methodologies in signal transduction. It demonstrates that therapeutics acting on second messengers must be both spatially and pathway-specific to prevent possible adverse systemic effects, a consideration that is becoming increasingly relevant for CKD drug development [7].

Other ways to integrate CKD etiology with metabolism, mitochondria, and oxidative stress have been described. Reduced mitochondrial biogenesis, altered oxidative phosphorylation, and excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) production contribute to tubular injury, endothelial dysfunction, and fibrogenesis [13,14,15]. Pro-inflammatory signaling pathways have metabolic and mitochondrial stress as their components. Both the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and the inflammasome pathways leading to interleukin-1β (IL-1β) production are tightly interconnected signaling cascades that form self-reinforcing inflammatory feedback loops that promote CKD. Even when the initial injury is resolved, maladaptive repair may create a continued state of inflammation [16,17,18,19,20]. In this context, the gut–kidney axis has emerged as a critical amplifier of metabolic and inflammatory stress. According to Młynarska et al. [21], many other studies have confirmed that changes to the microbial environment within the intestines of patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis can cause an increase in the levels of many uremic toxins. High levels of the two forms of sulfonated indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate activate the hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), which causes increased ROS and decreased function of tubular epithelial and endothelial cells in the kidney. This indicates that changes in the gut microbiome composition may directly impact the factors that contribute to kidney damage related to CKD [22]. Furthermore, Młynarska et al. [21] proposed various methods to modulate the gut microbiome using medications that enhance the bioavailability of dietary substrates and methods to improve the function of the intestinal barrier. Although significant barriers must still be overcome to implement such therapies in clinical practice, they may have favorable clinical outcomes when used in conjunction with nephroprotective therapies and may be important for the overall systemic regulation of the metabolism of patients with CKD.

A persistent limitation in CKD care is the reliance on late functional markers, including serum creatinine and albuminuria, which often increase only after substantial nephron loss [23]. Rhode et al. [24] closed this gap in the literature by creating urinary proteins that serve as a marker for “early stage” glomerular injury, before any evidence of albuminuria or inflammatory changes. These findings support ongoing efforts to create a new category of “mechanism-based” biomarkers that will enable the detection of reversible renal impairment. These methods have become increasingly parallel to the rapid expansion of proteomics, metabolomics, and single-cell transcriptomics, which have generated disease-specific molecular signatures before overt clinical manifestations of the disease become apparent [25]. The ability to detect diseases early is especially important for children and individuals with genetically inherited kidney diseases, as timely intervention can significantly affect their long-term health trajectory.

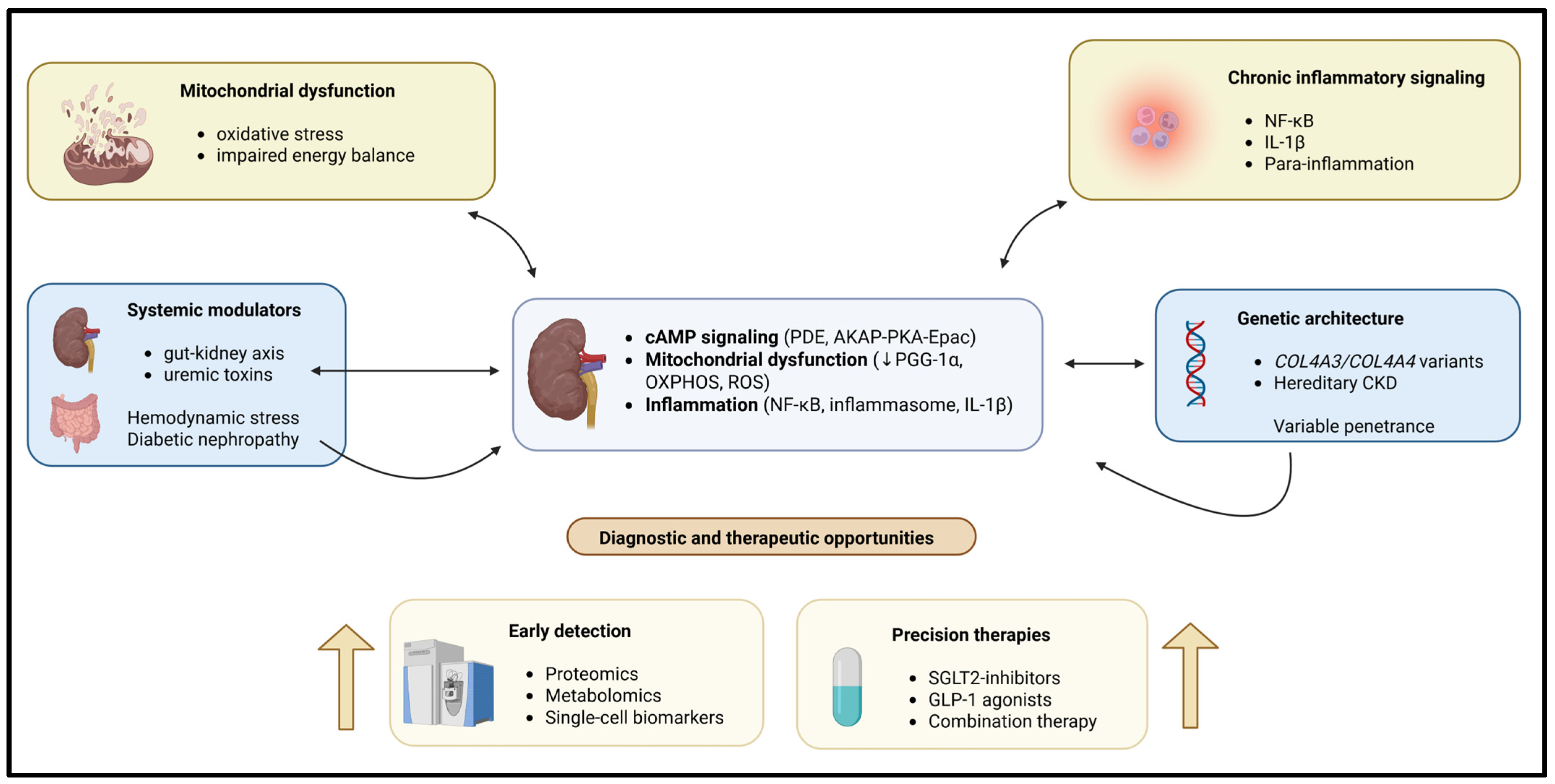

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a major cause of CKD driven by multiple converging pathogenic mechanisms, including oxidative stress, inflammation, and hemodynamic changes. As a result, if treatment only targets one type of injury, it will not be sufficient to treat patients with DN [26,27,28,29]. Morones-Gamboa et al. [30] demonstrated that combined pharmacological modulation using α-adrenergic antagonists, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists, and incretin-based pathways exerted additive renoprotective effects in a mouse model of DN. In addition, new clinical findings illustrate that combination treatment with sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors combined with glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) agonism offers additional renal and cardiovascular safety compared to each drug alone [31,32,33]. Aguilera-Martínez et al. [34] demonstrated the cellular mechanisms by which tamsulosin and pioglitazone inhibit hyperglycemia-mediated mesangial cell activation, oxidative stress, and extracellular matrix accumulation. Thus, these studies highlight drug repurposing and multi-pathway targeting as practical strategies for treating the complexity of CKD. A schematic representation of these interconnected mechanistic pathways is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is caused by multiple interacting molecular and systemic mechanisms leading to CKD. Intracellular signaling is disrupted, causing the dysregulation of normal mitochondrial and metabolic functions. Chronic inflammation, genetic susceptibility, and environmental influences combine to produce pathological changes in the kidney. Pathways exist within the kidney cells that may form self-reinforcing feedback loops leading to CKD, resulting in increased renal injury and fibrosis. The development of omics-type diagnostic tools, as well as the development of combination therapies, creates excellent opportunities for the recognition and earliest use of precision treatment before irreversible deterioration of renal function occurs.

Genetic kidney diseases provide critical insights into the pathogenesis of CKD and illustrate the importance of molecular diagnosis. Cerkauskaite-Kerpauskiene et al. [35] characterized COL4A3 and COL4A4 variants in a Lithuanian cohort with Alport syndrome, revealing substantial genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity. Their findings reinforce emerging evidence that the Alport syndrome is more prevalent than previously appreciated and is often underdiagnosed due to variable clinical expression [36,37,38]. This study [35] exemplifies the growing impact of genomic medicine in nephrology. It uses a genetic diagnosis early in the treatment process to establish the prognosis, assist with follow-up decisions, aid with familial counseling, and ultimately provide therapies based on each patient’s genotype. This is an example of the transition to precision nephrology, in which the molecular cause of a disease determines how it is classified and treated, instead of relying solely on histopathologic patterns.

The collective contributions of this Special Issue support the view that CKD is a network condition developed by several factors working together: intracellular signaling dysregulation, metabolic and mitochondrial stress, immune activation, genetic susceptibility, and systemic crosstalk. Advances in the use of various omics technologies, experimental models, and systems biology for research and development have greatly enhanced our understanding of these networks and the ability to provide new diagnostic and treatment options beyond those currently used [39,40,41]. For the future, success will be built upon translating molecular knowledge into detection methods based on the molecular mechanisms of the condition, the identification of biomarkers for the condition, and the development of conventionally based precision treatment of the conditions. The studies discussed in this Special Issue add significant conceptual and experimental bases for this approach and demonstrate the value of interdisciplinary collaboration in advancing CKD-related research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D., J.R.D. and M.M.S.; writing—review and editing, C.D., J.R.D. and M.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AhR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| AKAP | A-kinase anchoring protein |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| DN | Diabetic nephropathy |

| Epac | Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PDE | Phosphodiesterase |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SGLT2 | Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 |

References

- Jager, K.J.; Kovesdy, C.; Langham, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Jha, V.; Zoccali, C. A Single Number for Advocacy and Communication—Worldwide More than 850 Million Individuals Have Kidney Diseases. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.C.; Nagler, E.V.; Morton, R.L.; Masson, P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1238–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, A.S.; Chertow, G.M.; Fan, D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Hsu, C. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Risks of Death, Cardiovascular Events, and Hospitalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, K.; Coresh, J.; Sang, Y.; Chalmers, J.; Fox, C.; Guallar, E.; Jafar, T.; Jassal, S.K.; Landman, G.W.D.; Muntner, P.; et al. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate and Albuminuria for Prediction of Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Collaborative Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanravan, B.; Robinson-Cohen, C.; Patel, K.V.; Ayers, E.; Littman, A.J.; De Boer, I.H.; Ikizler, T.A.; Himmelfarb, J.; Katzel, L.I.; Kestenbaum, B.; et al. Association between Physical Performance and All-Cause Mortality in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delrue, C.; Speeckaert, R.; Moresco, R.N.; Speeckaert, M.M. Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate Signaling in Chronic Kidney Disease: Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Potentials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Beavo, J. Biochemistry and Physiology of Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases: Essential Components in Cyclic Nucleotide Signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 481–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccolo, M.; Magalhães, P.; Pozzan, T. Compartmentalisation of cAMP and Ca2+ Signals. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002, 14, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccolo, M.; Pozzan, T. Discrete Microdomains with High Concentration of cAMP in Stimulated Rat Neonatal Cardiac Myocytes. Science 2002, 295, 1711–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Xiang, F.; Lin, X.; Grajo, J.R.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Vyas, U.; Harisinghani, M.; Mahmood, U.; et al. The Role of Imaging in Prostate Cancer Care Pathway: Novel Approaches to Urologic Management Challenges Along 10 Imaging Touch Points. Urology 2018, 119, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloerich, M.; Bos, J.L. Epac: Defining a New Mechanism for cAMP Action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 50, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.M.; Ahn, S.H.; Choi, P.; Ko, Y.-A.; Han, S.H.; Chinga, F.; Park, A.S.D.; Tao, J.; Sharma, K.; Pullman, J.; et al. Defective Fatty Acid Oxidation in Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells Has a Key Role in Kidney Fibrosis Development. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, M.; Tam, D.; Bardia, A.; Bhasin, M.; Rowe, G.C.; Kher, A.; Zsengeller, Z.K.; Akhavan-Sharif, M.R.; Khankin, E.V.; Saintgeniez, M.; et al. PGC-1α Promotes Recovery after Acute Kidney Injury during Systemic Inflammation in Mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4003–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, D.L.; Green, N.H.; Danesh, F.R. The Hallmarks of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Boini, K.M.; Xia, M.; Abais, J.M.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, P.-L. Activation of Nod-Like Receptor Protein 3 Inflammasomes Turns on Podocyte Injury and Glomerular Sclerosis in Hyperhomocysteinemia. Hypertension 2012, 60, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, E.; Dixit, V.M. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Drive Proinflammatory Cytokine Production. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. The Nuclear Factor NF-kappaB Pathway in Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a001651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latz, E.; Xiao, T.S.; Stutz, A. Activation and Regulation of the Inflammasomes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Callaway, J.B.; Ting, J.P.-Y. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of Action, Role in Disease, and Therapeutics. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarska, E.; Budny, E.; Saar, M.; Wojtanowska, E.; Jankowska, J.; Marciszuk, S.; Mazur, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. Does the Composition of Gut Microbiota Affect Chronic Kidney Disease? Molecular Mechanisms Contributed to Decreasing Glomerular Filtration Rate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanholder, R.; Schepers, E.; Pletinck, A.; Nagler, E.V.; Glorieux, G. The Uremic Toxicity of Indoxyl Sulfate and P-Cresyl Sulfate: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 1897–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2012, 379, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhode, H.; Tautkus, B.; Weigel, F.; Schitke, J.; Metzing, O.; Boeckhaus, J.; Kiess, W.; Gross, O.; Dost, A.; John-Kroegel, U. Preclinical Detection of Early Glomerular Injury in Children with Kidney Diseases—Independently of Usual Markers of Kidney Impairment and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, W.; Greene, C.S.; Eichinger, F.; Nair, V.; Hodgin, J.B.; Bitzer, M.; Lee, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Kehata, M.; Li, M.; et al. Defining Cell-Type Specificity at the Transcriptional Level in Human Disease. Genome Res. 2013, 23, 1862–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alicic, R.Z.; Rooney, M.T.; Tuttle, K.R. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Bakris, G.L.; Bilous, R.W.; Chiang, J.L.; De Boer, I.H.; Goldstein-Fuchs, J.; Hirsch, I.B.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Narva, A.S.; Navaneethan, S.D.; et al. Diabetic Kidney Disease: A Report From an ADA Consensus Conference. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 64, 510–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-González, J.F.; Mora-Fernández, C. The Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.M.; Cooper, M.E.; De Zeeuw, D.; Keane, W.F.; Mitch, W.E.; Parving, H.-H.; Remuzzi, G.; Snapinn, S.M.; Zhang, Z.; Shahinfar, S. Effects of Losartan on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morones, J.; Pérez, M.; Muñoz, M.; Sánchez, E.; Ávila, M.; Topete, J.; Ventura, J.; Martínez, S. Evaluation of the Effect of an α-Adrenergic Blocker, a PPAR-γ Receptor Agonist, and a Glycemic Regulator on Chronic Kidney Disease in Diabetic Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.-F.; Mann, J.F.E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lindberg, M.; Rossing, P.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.F.E.; Ørsted, D.D.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Marso, S.P.; Poulter, N.R.; Rasmussen, S.; Tornøe, K.; Zinman, B.; Buse, J.B. Liraglutide and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, N.; Deanfield, J.E.; Mann, J.F.E.; Arechavaleta, R.; Bain, S.C.; Bajaj, H.S.; Bayer Tanggaard, K.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Buse, J.B.; Davicevic-Elez, Z.; et al. Oral Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in People With Type 2 Diabetes, According to SGLT2i Use: Prespecified Analyses of the SOUL Randomized Trial. Circulation 2025, 151, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Martínez, S.L.; Muñoz-Ortega, M.H.; Martínez-Hernández, S.L.; Morones-Gamboa, J.C.; Ventura-Juárez, J. Modulation of Mesangial Cells by Tamsulosin and Pioglitazone Under Hyperglycemic Conditions: An In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerkauskaite-Kerpauskiene, A.; Navickaite, M.; Savige, J.; Mazur, G.; Brazdziunaite, D.; Azukaitis, K.; Slazaite, G.; Laurinavicius, A.; Miglinas, M.; Vainutiene, V.; et al. Lithuanian Study on COL4A3 and COL4A4 Genetic Variants in Alport Syndrome: Clinical Characterization of 52 Individuals from 38 Families. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekheirnia, M.R.; Reed, B.; Gregory, M.C.; McFann, K.; Shamshirsaz, A.A.; Masoumi, A.; Schrier, R.W. Genotype–Phenotype Correlation in X-Linked Alport Syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtan, C.E.; Ding, J.; Gregory, M.; Gross, O.; Heidet, L.; Knebelmann, B.; Rheault, M.; Licht, C. Clinical Practice Recommendations for the Treatment of Alport Syndrome: A Statement of the Alport Syndrome Research Collaborative. Pediatr Nephrol 2013, 28, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savige, J.; Gregory, M.; Gross, O.; Kashtan, C.; Ding, J.; Flinter, F. Expert Guidelines for the Management of Alport Syndrome and Thin Basement Membrane Nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasin, Y.; Seldin, M.; Lusis, A. Multi-Omics Approaches to Disease. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinu, F.R.; Beale, D.J.; Paten, A.M.; Kouremenos, K.; Swarup, S.; Schirra, H.J.; Wishart, D. Systems Biology and Multi-Omics Integration: Viewpoints from the Metabolomics Research Community. Metabolites 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, I.; Verma, S.; Kumar, S.; Jere, A.; Anamika, K. Multi-Omics Data Integration, Interpretation, and Its Application. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2020, 14, 117793221989905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.