Abstract

Breast cancer remains one of the most prevalent and lethal malignancies affecting women worldwide, underscoring the need for safer and more effective therapeutic strategies. This study investigated the phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity, and antiproliferative potential of POW9™, a proprietary botanical blend formulated from nine medicinal plant extracts. Comprehensive phytochemical profiling was performed using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS) in both positive and negative ionization modes. A total of 34 compounds were identified in negative mode and 27 compounds in positive mode, comprising flavonoids, terpenoids, steroids, organic acids, peptides, glycosides, and lipids. POW9™ exhibited high total phenolic content (190.3 ± 3.5 mg gallic acid equivalents/g) and total flavonoid content (115.2 ± 1.5 mg quercetin equivalents/g), along with strong antioxidant activity, demonstrated by a 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 1.66 mg/mL (33.73 mg Trolox equivalents/g). Cytotoxicity assessment revealed minimal toxicity toward normal Vero cells. In contrast, POW9™ significantly inhibited the proliferation of human breast cancer cell lines in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The IC50 values were 6.75 mg/mL for MCF-7 cells and 18.08 mg/mL for MDA-MB-231 cells after 72 h of treatment, while prolonged exposure (96 h) further enhanced antiproliferative efficacy, reducing the IC50 to 2.34 mg/mL. These findings demonstrate that POW9™ is a chemically diverse herbal formulation with potent antioxidant and selective anti-breast cancer activities, supporting its potential development as a complementary therapeutic or nutraceutical agent for breast cancer management.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies and a leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide, representing a major global health burden [1,2,3,4]. However, advances in early detection and treatment have improved survival rates, significant clinical challenges remain, including disease recurrence, therapeutic resistance, systemic toxicity, and limited treatment options for aggressive subtypes such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [5,6,7,8,9]. Current treatment strategies include surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted agents. For example, endocrine therapies for estrogen receptor (ER)-positive tumors, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-directed agents (such as trastuzumab and related monoclonal antibodies) for HER2-overexpressing breast cancers, and other molecularly targeted approaches aim at specific signaling pathways involved in tumor growth and survival. While ER-positive and HER2-positive breast cancers benefit from targeted therapies, TNBC lacks specific molecular targets and is associated with poor prognosis and limited therapeutic options [7,10]. These limitations underscore the need for safer, more effective, and complementary therapeutic strategies with improved clinical relevance. Medicinal plants and natural products have long been recognized as rich sources of bioactive compounds, including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and fatty acids, many of which exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Increasing attention has been toward multi-component botanical formulations, which may offer enhanced therapeutic efficacy through multi-targets and potentially synergistic mechanisms while minimizing toxicity toward normal cells. Such formulations are particularly attractive as adjunct or nutraceutical approaches, supporting long-term disease management and improving patient quality of life. From a sustainability perspective, plant-based products represent renewable and accessible resources that align with current trends in integrative, preventive, and personalized medicine.

Despite growing interest in botanical formulations, many products remain insufficiently characterized with respect to their chemical composition and biological activity, limiting their translational value and clinical applicability. Advanced analytical platforms, particularly ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography coupled with UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS enable comprehensive, untargeted profiling of complex botanical products, facilitating the identification of diverse phytochemical constituents [19,20]. Such analytical strategies are essential for ensuring quality control, reproducibility, and mechanistic insight—key requirements for translational research and future clinical development of botanical-based interventions.

POW9™ is a proprietary botanical blend formulation developed by G&B Enzymes Company Limited (Bangkok, Thailand), composed of extracts derived from nine medicinal plants traditionally associated with antioxidant and health-promoting properties. The formulation was designed as an antioxidant-rich nutraceutical intended to support general health and wellness, with potential complementary relevance to oxidative stress–related conditions, including cancer. The biological rationale for POW9™ is based on the complementary and potentially synergistic actions of its constituent plant extracts, which are rich in phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, fatty acids, and other bioactive metabolites known to modulate redox balance, inflammatory processes, and cancer-related cellular pathways. Despite its commercial availability, the detailed phytochemical composition and anticancer-related biological activities of POW9™ have not been systematically characterized, underscoring the need for comprehensive chemical profiling and biological evaluation. This study integrates untargeted UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS profiling with antioxidant evaluation and comparative antiproliferative assessment of POW9™ in hormone-dependent (MCF-7) and hormone-independent (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer cell lines, along with selectivity toward normal Vero cells. This combined approach provides clinically relevant insight and highlights the translational value of POW9™ as a complementary or nutraceutical candidate for breast cancer management.

2. Results

2.1. UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS Based Phytochemical Profiling

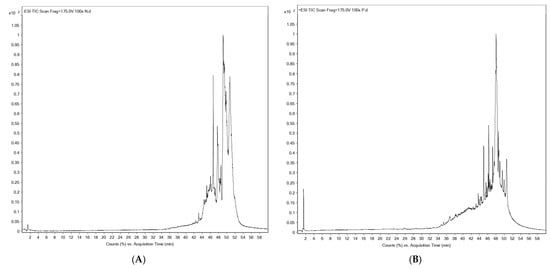

The phytochemical composition of POW9™ was analyzed using UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS in both negative and positive ionization modes. The base peak chromatograms demonstrated well-resolved peaks across a 60-minute elution period. In the negative ion mode (Figure 1A and Table 1A), a total of 34 compounds were identified, predominantly consisting of esters and carboxylic acids. Notable compounds included butyl butyryl lactate, ricinoleic acid, glyceryl monoleate, octadecadienoic acid, and eicosanedioic acid.

Figure 1.

Profiles of phenolic compounds from POW9TM analyzed with UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS using negative mode (A) and positive mode (B).

Table 1.

Polar phenolic compounds detected in POW9TM product by UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS.

Positive ion mode analysis (Figure 1B and Table 1B) resulted in the identification of 27 compounds, mainly phospholipids, peptides, glycosides, and bioactive secondary metabolites. Key compounds included phosphatidic acid, phosphoethanolamine derivatives, Trp-His-Val, Thr-Thr, ceramide glycosides, and tafluprost. The combined ionization approaches provided a comprehensive phytochemical profile of POW9™, highlighting its chemical diversity and complexity.

2.2. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity

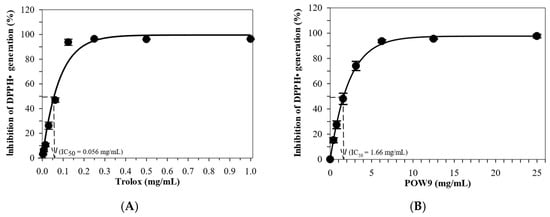

The antioxidant properties of POW9™ were assessed through the determination of total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and DPPH radical scavenging activity. POW9™ exhibited a TPC of 190.3 ± 3.5 mg GAE/g and a TFC of 115.2 ± 1.5 mg quercetin equivalent (QE)/g (Table 2). The DPPH assay demonstrated that both POW9™ and Trolox inhibited free radical generation in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2). The IC50 values were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis: 1.66 mg/mL for POW9™ and 0.056 mg/mL for Trolox. The antioxidant capacity of POW9™ was equivalent to 33.73 mg Trolox per gram, corresponding to 20.24 mg Trolox-equivalent antioxidant activity (TEAC) per 600 mg capsule, indicating its substantial antioxidant activity under the tested conditions.

Table 2.

TPC, TFC and antioxidant activity of POW9TM product. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent analyses.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of DPPH radical (DPPH•) generation by Trolox (A) and POW9TM (B). Data are expressed in mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments.

2.3. Effect of POW9TM on Vero Cell Viability

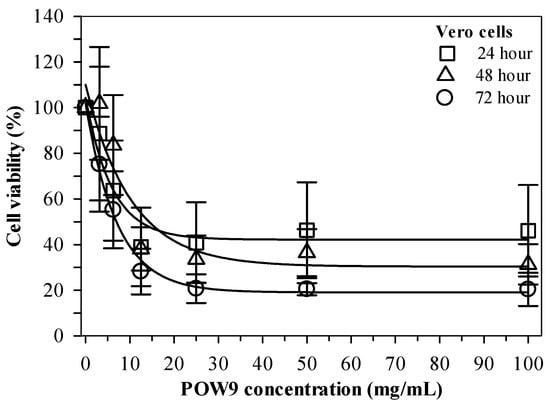

The cytotoxic potential of POW9™ was assessed using a cell viability assay in Vero cells treated with concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 mg/mL for 24, 48, and 72 h. Microscopic examination did not reveal overt morphological disruption of Vero cells at low to moderate concentrations of POW9™. At higher concentrations, although changes in culture medium appearance were observed, quantitative 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) analysis indicated that overall cell viability remained above 50% under the experimental conditions (Figure S1). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that POW9™ maintained high cell viability across all tested time points (Figure 3). These results indicate that POW9™ exhibits relatively low cytotoxicity toward Vero cells compared with its effect on breast cancer cell lines under the experimental conditions.

Figure 3.

Viability of Vera cells treated with POW9TM (0–100 mg/mL) for 24, 48 and 72 h. Data obtained from three independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SD.

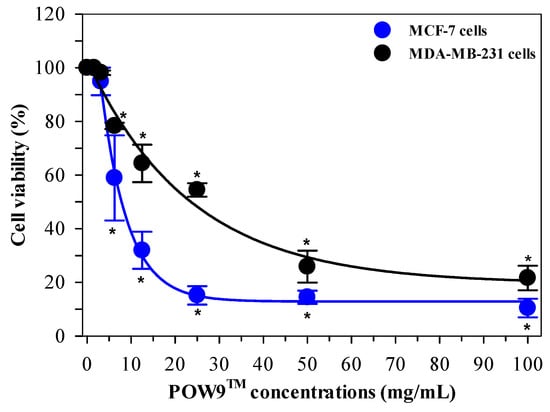

2.4. Antiproliferative Effect of POW9™ on Breast Cancer Cells

The antiproliferative activity of POW9™ was evaluated using MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines treated with concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 mg/mL for 72 h. Microscopic examination revealed a marked reduction in cell density at higher concentrations, accompanied by visible morphological alterations (Figure S2). MTT assay results demonstrated that POW9™ significantly reduced cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner in both cell lines. In this study, the IC50 value represents the primary measure of antiproliferative potency. POW9™ was more effective against MCF-7 cells, with an IC50 value of 7.81 mg/mL, compared to 23.6 mg/mL for MDA-MB-231 cells. At 100 mg/mL, POW9™ inhibited approximately 90% of MCF-7 cell growth and 70% of MDA-MB-231 cell growth, indicating pronounced antiproliferative effects in vitro (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dose-dependent antiproliferative effects of POW9TM on breast cancer cell lines. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with POW9TM (0–100 mg/mL) for 72 h. Cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay and expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05 versus untreated control.

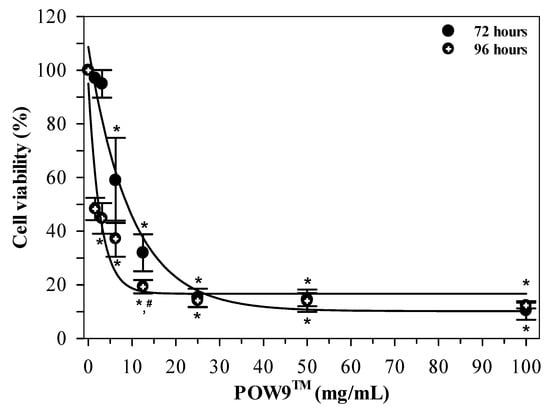

To assess the effect of prolonged exposure, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with POW9™ (0–100 mg/mL) for 72 and 96 h. Microscopic analysis revealed a progressive reduction in cell density with increasing concentrations (Figure S3). As shown in Figure 5, POW9™ treatment resulted in a concentration-dependent reduction in cell viability at both time points. Notably, extended exposure for 96 h led to a more pronounced decrease in cell viability compared to 72 h at corresponding concentrations. A significant decrease in cell viability was found at low concentrations (1.56–3.12 mg/mL), yielding IC50 values of 2.34 mg/mL for 96 h treatment, whereas no substantial additional reduction in viability was observed at higher concentrations, suggesting no further reduction in viability at higher concentrations under the tested conditions. Thus, extended treatment duration was associated with enhanced antiproliferative activity of POW9™, as reflected by reduced IC50 values at 96 h compared with 72 h.

Figure 5.

Time-dependent effects of POW9TM on MDA-MB-231 cell viability. Cells were treated with POW9TM (0–100 mg/mL) for 72 and 96 h. Cell viability was determined using the MTT assay and expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Statistical significance between durations at the same concentration was assessed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. * p < 0.05 versus untreated control (same time), # p < 0.05 versus 72 h at same concentration.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the anticancer efficacy of POW9™ is both dose- and time-dependent.

3. Discussion

The present study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity, and antiproliferative potential of POW9™, a multi-component botanical formulation. Using UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS operated in both negative and positive ionization modes, POW9™ was shown to possess a chemically diverse profile comprising fatty acids, organic acids, terpenoids, glycosides, peptides, phospholipids, and other secondary metabolites [19,20,21,22,23]. The higher number of compounds detected in negative ionization mode is consistent with the prevalence of acidic, phenolic, and lipid-associated constituents commonly found in plant-derived extracts and complex botanical matrices [19,21]. Several identified compounds associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities, including hydroxy- and dihydroxy-octadecenoic acids, ricinoleic acid, and octadecadienoic acid have been reported to modulate oxidative stress and inhibit cancer cell proliferation [24,25,26,27]. Terpenoid- and phenolic-related constituents, such as blumenol derivatives and citronellol acetate, are also known for their radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties [28,29]. Although the contribution of individual compounds cannot be conclusively delineated due to the complexity of the formulation, the observed biological effects are likely mediated through additive or synergistic interactions among these constituents.

The antioxidant assays performed in this study (TPC, TFC, and TEAC) were conducted on the crude POW9™ formulation and were intended solely to provide general compositional and chemical characterization. These assays were not designed to assess intracellular antioxidant effects or to establish a mechanistic link between redox modulation and antiproliferative activity. As such, the antioxidant measurements should not be interpreted as evidence of anticancer mechanisms, nor should they be directly comparable to reference compounds with established anticancer efficacy. Consistent with its phytochemical richness, POW9™ exhibited strong antioxidant capacity, as evidenced by high total phenolic and flavonoid contents and potent DPPH radical scavenging activity. The relationship between phenolic and flavonoid abundance and antioxidant efficacy has been widely documented for botanical extracts [29,30,31,32]. Importantly, the antioxidant-effective concentration was substantially lower than the concentration required to inhibit cancer cell proliferation, suggesting that POW9™ may exert protective antioxidant effects without impairing normal cellular viability.

Evaluation of cytotoxicity demonstrated that POW9™ exhibited minimal toxicity toward normal Vero cells across all tested concentrations and time points, supporting a favorable in vitro selectivity profile. In contrast, POW9™ significantly inhibited the proliferation of both MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. The formulation was more potent against estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 cells than against the more aggressive, hormone-independent MDA-MB-231 cells, a pattern that has been commonly reported and may reflect differences in hormone signaling, redox regulation, and metabolic sensitivity between these cells [9,33].

Notably, prolonged exposure markedly enhanced the antiproliferative efficacy of POW9™, particularly in MDA-MB-231 cells [9,34]. As demonstrated by comparative viability analysis, treatment for 96 h resulted in significantly greater growth inhibition than 72 h at equivalent concentrations, corresponding to a reduction in the IC50 value from 18.08 mg/mL to 2.34 mg/mL. Time-dependent responses of this nature are frequently observed for phytochemical-rich formulations and are often attributed to cumulative oxidative stress, delayed activation of apoptotic signaling pathways, and progressive disruption of cellular metabolic homeostasis [16,35]. The pronounced enhancement of activity in the estrogen-independent MDA-MB-231 model is particularly noteworthy given the limited therapeutic options available for triple-negative breast cancer.

The present study did not investigate molecular mechanisms of action, and no direct comparisons were made with isolated plant extracts or reference bioactive compounds. Hence, the observed antiproliferative effects should be interpreted strictly as phenomenological outcomes of exposure to a complex botanical formulation rather than as evidence of specific biochemical or signaling pathways [36]. This study combines untargeted high-resolution mass spectrometric profiling with in vitro cell viability assays to provide a descriptive characterization of a multi-component botanical formulation and its comparative antiproliferative effects in breast cancer cell models. The use of both hormone-dependent and hormone-independent breast cancer models provides broader relevance to heterogeneous breast cancer subtypes. These findings support further investigation of POW9 as a phytochemical-rich formulation with selective antiproliferative activity in vitro, while emphasizing the need for mechanistic, in vivo, and safety studies to establish translational relevance.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study was conducted exclusively in vitro, and therefore, the observed biological effects may not fully reflect in vivo pharmacokinetics, bioavailability, or metabolic interactions. Second, antioxidant activity was assessed only at the formulation level and outside a cellular context, limiting its biological interpretability. Third, the antiproliferative effects were assessed using a single viability assay, and specific molecular mechanisms such as apoptosis induction, cell cycle arrest, or oxidative stress modulation were not directly investigated. Fourth, no benchmarking against isolated compounds or clinically relevant anticancer agents was performed. Consequently, the findings should be viewed as preliminary and descriptive, providing a basis for future mechanistic and comparative investigations rather than definitive evidence of anticancer mechanisms. Future studies should include formal physicochemical stability assessments to further characterize POW9™ under extended incubation conditions.

Finally, as POW9™ is a complex botanical blend, the individual contribution of specific compounds or potential synergistic interactions could not be definitively delineated. Future studies should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying the anticancer effects of POW9™, including the involvement of apoptotic pathways, oxidative stress regulation, and hormone-related signaling. In vivo studies and pharmacokinetic evaluations are warranted to confirm efficacy, safety, and bioavailability. Additionally, fractionation studies or combination analyses may help identify key bioactive constituents and synergistic interactions, thereby facilitating optimization of the formulation for therapeutic or nutraceutical applications.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals, Reagents and Labware

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), DPPH, MTT, Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, aluminum chloride, potassium acetate, sodium carbonate, Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid), Tween 20, quercetin (Q) and gallic acid (GA) standard were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals Company Limited, Saint Louis, MO, USA. Phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.4 (PBS) solution, trypsin-ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid (T-EDTA), RPMI 1640 medium, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin were purchased from HycloneTM (Global Life Sciences Solutions USA LLC, Wilmington, DE, USA). Organic solvents including acetonitrile and formic acid (HPLC-grade or highest pure grade) were supplied by BDH Chemicals Company Limited, Poole, Dorset, UK. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane filters (13 mm diameter with 0.45 µm pore size, 13 mm diameter with 0.22 µm pore size, and 33 mm diameter with 0.22 μm pore size) were purchased from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany.

4.2. POW9TM Product

POW9TM (Lot. Number G&B/L3/0004) is a proprietary botanical formulation developed by G&B Enzymes Company Limited, Bang Bon, Bangkok, Thailand. The product (600 mg per capsule) consisted of extracts derived from nine medicinal plants traditionally associated with antioxidant and health-promoting activities, including turmeric Curcuma longa L. rhizome powder, cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum) bark, emblica (Phyllanthus emblica L.) fruit, ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.) leaves, gotu kola (Centella asiatica) leaves, black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) fruit, tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves, mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) aril and roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) flowers. POW9TM is commercially available in Thailand as a nutraceutical dietary supplement.

4.3. Preparation of POW9TM Solution

POW9TM was prepared as a homogeneous suspension rather than a fully dissolved solution, reflecting the complex botanical nature of the formulation. The powder was dissolved in a culture medium containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 20, then vortexed thoroughly, and sonicated for 20 min to ensure uniform dispersion. The POW9TM stock solution, with a final concentration of 100 mg/mL, was filtered through the syringe PVDF membrane. Sterilization was performed after complete dispersion, and no visible residue remained on the membrane filter, indicating effective passage of suspended material under the applied conditions. The POW9TM working solution was freshly prepared immediately before each experiment by diluting the stock solution with 0.1% Tween 20 solution and was not stored for reuse. Although formal chemical stability studies were not conducted, the formulation was handled consistently across experiments, and treatment media were used within the same experimental timeframe as the in vitro assays.

4.4. UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS Profiling of Phytocompounds

Chemical constituents in POW9TM were analyzed using a powerful UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS technique as previously described by Hodgson and colleagues [22] with slight modifications [23]. The instrument system was composed of an HPLC machine (Agilent 1260 Infinity II LC, Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI)-QTOF-MS. In the MS system, nitrogen gas nebulization was set at 45 pounds per square inch (psi) with a flow rate of 5.0 L/min at 300 °C. The sheath gas was set at 11.0 L/min at 250 °C, and the capillary and nozzle voltage values were set at 3.5 kV and 500 V, respectively. A complete mass scan was conducted with mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) values ranging from 200 to 3200. All operations, acquisitions, and analyses of the data were monitored using Agilent UHPLC-QTOF-MS MassHunter Acquisition Software Version B.04.00, with the “Find by Be” algorithm, to generate a list of precise mass match compounds. Peak identification was performed in positive modes using the library database, and the identification scores were further selected for characterization and m/z verification.

In analysis, 500 mg of the POW9TM sample was reconstituted in 1% (v/v) DMSO (1.0 mL), ultrasonicated on an ice bath for 10 min, and then centrifuged at 17,000× g at room temperature for 10 min. Afterward, the supernatant was passed through a syringe filter (cellulose ester type, 13 mm diameter, 0.45 µm pore size, Merck Amicon filter, Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, Limited, Saint Louis, MO, USA). In the analysis, the filtrate (5 μL) was injected into the HPLC system using an autosampler and fractionated on a column (InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC octadecyl silane type, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 2.7 µm particle size, Agilent Technologies Company, Santa Clara, CA, USA) that had been thermally regulated at 40 °C and eluted in a linear gradient mode using mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in DI) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min for 60 min. The timing program employed for gradient elution was as follows: 0 ⟶ 15 min; %A/B (100/0 ⟶ 90/10), 15 ⟶ 30 min; %A/B (90/10 ⟶ 40/60); 30 ⟶ 45 min: A (40/60 ⟶ 10/90); and 45 ⟶ 60 min; A (10/90 ⟶ 0/100). Peak identification was performed in positive mode using the library database, and the identification scores were sorted for characterization and m/z verification purposes.

Mass error in parts per million (ppm) was calculated using the Formula (1):

Compound annotation was performed based on accurate mass matching with a tolerance threshold of ±10 ppm, in combination with isotopic pattern consistency and database/library comparisons.

4.5. Estimation of TPC and TFC

TPC was determined using a colorimetric method [30]. POW9TM solution (100 µL) was mixed with 10% (v/v) Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (200 µL) and 10% (w/v) sodium carbonate (800 µL). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 30 min, and the absorbance (A) value was measured at a wavelength of 700 nm against a reagent blank using a double-beam ultraviolet–visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer (Model UV-1800, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). TPC was determined from a standard curve of GA and reported in terms of mg GA/g.

TFC was determined using the colorimetric method based on the formation of a stable complex between aluminum ions and flavonoids [37]. The POW9TM solution (250 µL) was mixed with a chromogenic reagent containing 10% (w/v) aluminum chloride (50 µL), 1 M potassium acetate (50 µL), and DI (2.15 mL). The mixture was then incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 30 min, and the A value was measured at a wavelength of 415 nm against a reagent blank using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer [38]. TFC was determined from a standard curve of Q and reported as mg QE/g.

4.6. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity Assay

The free radical scavenging activity of POW9TM was determined based on a DPPH colorimetric method [31]. In the assay, 40 μL of POW9TM solution (5, 10, and 20 mg/mL) was mixed with 160 μL of freshly prepared 200 μM DPPH solution and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Following incubation, the A value was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek Lonza ELx808LBS, BioTek Instruments, Saint Winooski, VT, USA) at 517 nm. Antioxidant activity was calculated using the Formula (2) [32] as follows:

where Ac = absorbance of controls and At = absorbance of treatments. Accordingly, IC50 values for POW9TM were calculated using GraphPad Prism software version 7.0 (Informer Technologies, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, USA).

4.7. Assessment for Effect of POW9TM on Vera and Breast Cancer Cells

4.7.1. Cell Culture

Vero cell line (ATCC-CCL-81™) obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM (high glucose and L-glutamine.) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. When reaching 80–90% cell confluency, the medium was discarded, the cell monolayer was gently washed once with sterile PBS without calcium and magnesium and detached from the plate by incubating with 0.25% (w/v) T-EDTA briefly until cell detachment was observed. The cell suspension was neutralized with complete growth medium and collected by gentle pipetting. Afterward, the cells were sedimented by centrifugation at 200× g for 5 min, resuspended in fresh complete medium and seeded into new culture vessels at the desired density. Medium was replaced every 2–3 days, and cell morphology and confluency were monitored regularly using phase-contrast microscopy. All cell culture procedures were performed under aseptic conditions in a Class II biosafety cabinet.

MCF-7 (ATCC HB-22™) and MDA-MB-231 (HTB-26™), obtained from the ATCC, were cultured according to the method established by Gest and coworkers [33]. RPMI 1640 medium was supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin while DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 4 mM glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and the media were sterilized by ultra-filtration through the membrane (33 mm diameter, 0.22 μm pore size). Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells (3 × 104/well) were grown in the RPMI 1640 medium and MCF-7 cells (3 × 104/well) were grown in the DMEM at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere till achieved 80% cell confluence was achieved.

4.7.2. Investigation of Antiproliferative Activity of POW9™

In the study, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell cultures were incubated with POW9TM solution (1.56–100 mg/mL) at 37 °C for 72 and 96 h. After incubation, the cells were washed two times with PBS and determined cell viability using the MTT method, as described below. The 0-concentration group represents the vehicle (untreated) control and consisted of complete culture medium containing the same final concentration of Tween 20 as used in POW9™-treated samples, but without POW9™. The concentration of Tween 20 used was low and did not induce detectable cytotoxic effects under the experimental conditions. All viability measurements were normalized to this vehicle control to exclude potential effects of the solvent. All cell-based experiments were performed using three independent biological replicates, defined as separate experiments conducted on different days with independently cultured cells and freshly prepared POW9™ solutions. Within each biological replicate, MTT measurements were performed in technical triplicate.

4.7.3. Assay of Cell Viability

Colorimetric MTT assay was performed to evaluate the cell toxicity of POW9TM, following the method described by Nguyen and coworkers [35]. The treated cells were incubated with 1 mg/mL MTT solution (20 μL) at 37 °C for 4 h. Following incubation, the produced blue-colored formazan crystal was solubilized with 1% DMSO solution (200 μL) with shaking for 1 h at room temperature [36]. The A was recorded at 570 nm using a BioTek 96-well microplate reader. The percentage of cell viability was calculated using the Formula (3) as follows:

where Ac = absorbance of untreated controls, At = absorbance of treatments. Accordingly, IC50 values for each extract were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software version 7.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

4.8. Statistical Analysis

The in vitro cell culture experiments were conducted in triplicate. The biochemical assays were also performed in triplicate. The data sets were statistically analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics for Windows version 22 Program (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and expressed as values of mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical differences were tested using the One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by the post hoc analysis via Tukey–Kramer test, which p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Prior to performing the ANOVA test, data were examined for approximate normality and homogeneity of variance to verify that ANOVA assumptions were met. Dose–response curves were fitted using nonlinear regression analysis based on a four-parameter logistic model, and IC50 (or LC50, where applicable) values were calculated using SigmaPlot version 15.0 Program (SYSTAT Software Inc., Grafiti, St. Palo Alto, CA, USA). These IC50 values served as the primary quantitative endpoint for cytotoxicity assessment.”

5. Conclusions

This study provides an untargeted UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS chemical profile of POW9™ and a comparative in vitro assessment of its effects on cell viability in Vero, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cells. POW9™ showed concentration- and time-dependent antiproliferative effects in breast cancer cell lines under the tested conditions, while exhibiting lower cytotoxic effects in Vero cells. The antioxidant assays (TPC, TFC, TEAC) are presented as formulation-level compositional characterization and do not establish an anticancer mechanism. Overall, the findings should be interpreted as exploratory and support further work, including mechanistic cellular assays, benchmarking against reference compounds, and in vivo evaluation to determine translational relevance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27031246/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T., P.T., P.K., D.D.P., S.S. and W.T.; methodology, P.K. and W.T.; formal analysis, P.K. and W.T.; investigation, C.T., P.K. and W.T.; resources, C.T. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and W.T.; writing—review and editing, S.S. and W.T.; supervision, P.K., D.D.P. and W.T.; project administration, P.K. and W.T.; funding acquisition, C.T., P.T., P.K. and W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by G&B Enzymes Company Limited, Bangkok, Thailand (Grant number: 01/2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Office of Research Administration at Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai and the School of Medical Science, University of Phayao, Phayao, Thailand for technical assistance and laboratory facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

Chirra Taworntawat and Pisit Tonkittirattanakul are employed by G&B Enzymes Company Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations/symbols are used in this manuscript:

| A | Absorbance |

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GA | Gallic acid |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalent |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| m/z | Mass-to-charge ratio |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| psi | pounds per square inch |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| Q | Quercetin |

| QE | Quercetin equivalent |

| TEAC | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity |

| T-EDTA | Trypsin-ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid |

| TFC | Total flavonoid content |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TPC | Total phenolic content |

| Trolox | 6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid |

| UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS | Ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer |

| v/v | Volume by volume |

| [M+H]+ | Protonated molecule |

| [M-H]− | Deprotonated molecule |

References

- Cannon, G.; Gupta, P.; Gomes, F.; Kerner, J.; Parra, W.; Weiderpass, E.; Kim, J.; Moore, M.; Sutcliffe, C.; Sutcliffe, S.; et al. Prevention of cancer and non-communicable diseases. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, M.; Iqbal, M.; Daniyal, M.; Khan, A.U. Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Gathani, T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolarz, B.; Nowak, A.Z.; Romanowicz, H. Breast cancer-epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis and treatment (Review of literature). Cancers 2022, 14, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaschler, M.M.; Hu, F.; Feng, H.; Linkermann, A.; Min, W.; Stockwell, B.R. Determination of the subcellular localization and mechanism of action of ferrostatins in suppressing ferroptosis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzaman, K.; Karami, J.; Zarei, Z.; Hosseinzadeh, A.; Kazemi, M.H.; Moradi-Kalbolandi, S.; Safari, E.; Farahmand, L. Breast cancer: Biology, biomarkers, and treatments. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 84, 106535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbeck, N.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Cortes, J.; Gnant, M.; Houssami, N.; Poortmans, P.; Ruddy, K.; Tsang, J.; Cardoso, F. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkali, S.; Saloustros, E.; Stefanou, D.; Makrantonakis, P.; Kentepozidis, N.; Boukovinas, I.; Xenidis, N.; Katsaounis, P.; Ardavanis, A.; Ziras, N.; et al. Front-line bevacizumab plus chemotherapy with or without maintenance therapy for metastatic breast cancer: An observational study by the Hellenic Oncology Research Group. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, M.; Bekele, F.; Fekadu, G. Treatment strategies against triple-negative breast cancer: An updated review. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press) 2022, 14, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, H.; Wang, F.; Fan, Q.X.; Wang, L.X. Curcumin inhibits metastatic progression of breast cancer cell through suppression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator by NF-kappa B signaling pathways. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 4803–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermansyah, D.; Anggia Paramita, D.; Paramita, D.A.; Amalina, N.D. Combination Curcuma longa and Phyllanthus niruri extract potentiate antiproliferative in triple negative breast cancer MDAMB-231 Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 1495–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, I.; Ahmad, R.; Chandra, A.; Raza, S.T.; Shukla, Y.; Mahdi, F. Phytochemical characterization and biological activity evaluation of ethanolic extract of Cinnamomum zeylanicum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 219, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Hwang, I.H.; Hong, C.E.; Lyu, S.Y.; Na, M. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase by ginkgolic acids from the leaves of Ginkgo biloba and their cytotoxic activity. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamkitidechakul, C.; Jaijoy, K.; Hansakul, P.; Soonthornchareonnon, N.; Sireeratawong, S. Antitumour effects of Phyllanthus emblica L.: Induction of cancer cell apoptosis and inhibition of in vivo tumour promotion and in vitro invasion of human cancer cells. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saeedi, F.J. Study of the cytotoxicity of asiaticoside on rats and tumour cells. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Grinevicius, V.M.; Kviecinski, M.R.; Santos Mota, N.S.; Ourique, F.; Porfirio Will Castro, L.S.; Andreguetti, R.R.; Gomes Correia, J.F.; Filho, D.W.; Pich, C.T.; Pedrosa, R.C. Piper nigrum ethanolic extract rich in piperamides causes ROS overproduction, oxidative damage in DNA leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 189, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.P.; Wang, A.; Ye, J.H.; Zheng, X.Q.; Polito, C.A.; Lu, J.L.; Li, Q.S.; Liang, Y.R. Suppressive effects of tea catechins on breast cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, N.; Rani, A.N.; Mahmud, R.; Yin, K.B. Antioxidant and cytotoxic effect of Barringtonia racemosa and Hibiscus sabdariffa fruit extracts in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Xiao, H.; Liu, J.; Liang, X. Identification of phenolic constituents in Radix Salvia miltiorrhizae by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 20, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.Y.; Avula, B.; Zhao, J.; Raman, V.; Wang, Y.H.; Wang, M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Feng, W.; Park, J.H.; Abe, N.; et al. Analysis of prenylflavonoids from aerial parts of Epimedium grandiflorum and dietary supplements using HPTLC, UHPLC-PDA and UHPLC-QToF along with chemometric tools to differentiate Epimedium species. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 177, 112843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Y.; Mujib, A.; Mamgain, J.; Syeed, R.; Mohsin, M.; Nafees, A.; Dewir, Y.H.; Mendler-Drienyovszki, N. Integrated GC-MS and UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS based untargeted metabolomics analysis of in vitro raised tissues of Digitalis purpurea L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1433634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A.B.; Randell, R.K.; Mahabir-Jagessar, T.K.; Lotito, S.; Mulder, T.; Mela, D.J.; Jeukendrup, A.E.; Jacobs, D.M. Acute effects of green tea extract intake on exogenous and endogenous metabolites in human plasma. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prommaban, A.; Utama-Ang, N.; Chaikitwattana, A.; Uthaipibull, C.; Porter, J.B.; Srichairatanakool, S. Phytosterol, lipid and phenolic composition, and biological activities of guava seed oil. Molecules 2020, 25, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Debnath, S.; Gajbhiye, R.L.; Saikia, R.; Gogoi, B.; Samanta, S.K.; Das, D.K.; Biswas, K.; Jaisankar, P.; Mukhopadhyay, R. Ricinus communis L. fruit extract inhibits migration/invasion, induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells and arrests tumor progression in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, P. Evaluation of fatty acid composition and antioxidant activity of wild-growing mushrooms from Southwest China. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2017, 19, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Bao, J.; Zhu, F.; Pan, M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, P. Ethnopharmacology of Rubus idaeus Linnaeus: A critical review on ethnobotany, processing methods, phytochemicals, pharmacology and quality control. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 302, 115870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.C.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.L.; Yun, B.S.; Lee, D.S. Coriolic acid (13-(S)-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid) from glasswort (Salicornia herbacea L.) suppresses breast cancer stem cell through the regulation of c-Myc. Molecules 2020, 25, 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.; Shibamoto, T. Antioxidant activities and volatile constituents of various essential oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marino, S.; Gala, F.; Zollo, F.; Vitalini, S.; Fico, G.; Visioli, F.; Iorizzi, M. Identification of minor secondary metabolites from the latex of Croton lechleri (Muell-Arg) and evaluation of their antioxidant activity. Molecules 2008, 13, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutachok, N.; Angkasith, P.; Chumpun, C.; Fucharoen, S.; Mackie, I.J.; Porter, J.B.; Srichairatanakool, S. Anti-platelet aggregation and anti-cyclooxygenase activities for a range of coffee extracts (Coffea arabica). Molecules 2020, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaraj, S.; Tikent, A.; Chebaibi, M.; Bouaouda, K.; Bouhrim, M.; Sweilam, S.H.; Herqash, R.N.; Shahat, A.A.; Addi, M.; Elfazazi, K. A Study of the bioactive compounds, antioxidant capabilities, antibacterial effectiveness, and cytotoxic effects on breast cancer cell lines using an ethanolic extract from the aerial parts of the indigenous plant Anabasis aretioides Coss. & Moq. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 12375–12396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Ediriweera, M.K.; Davaatseren, M.; Hyun, H.B.; Cho, S.K. Antioxidant activity of banana flesh and antiproliferative effect on breast and pancreatic cancer cells. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gest, C.; Joimel, U.; Huang, L.; Pritchard, L.L.; Petit, A.; Dulong, C.; Buquet, C.; Hu, C.Q.; Mirshahi, P.; Laurent, M.; et al. Rac3 induces a molecular pathway triggering breast cancer cell aggressiveness: Differences in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, M.A.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.C.; Farooqi, H.M.U.; Lee, D.S.; Kang, C.U. Cytotoxic and cellular response of doped Nb-NTO nanoparticles functionalized with Mentha arvensis and Mucuna pruriens extracts on MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 4332–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Thi, L.H.; Nguyen, S.T.; Tran, T.P.; Phan-Lu, C.N.; Van Pham, P.; The Van, T. Anti-cancer effect of Xao Tam Phan Paramignya trimera methanol root extract on human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 in 3D model. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1292, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- van Tonder, A.; Joubert, A.M.; Cromarty, A.D. Limitations of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay when compared to three commonly used cell enumeration assays. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J. Aoac Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petry, R.D.; Ortega, G.G.; Silva, W.B. Flavonoid content assay: Influence of the reagent concentration and reaction time on the spectrophotometric behavior of the aluminium chloride--flavonoid complex. Pharmazie 2001, 56, 465–470. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.