Abstract

The current study investigates the modulatory effects of gallic acid (GA), 3-hydroxytyrosol (3-HT), and quercetin (QUE) on key cholinesterase enzymes using Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) head homogenates as a source of central cholinesterases following in vivo larval exposure. The choice of these plant phenolics was predicated on their cholinesterase (ChE) inhibitory effect reported recently by our group. The study utilized D. melanogaster larvae subjected to varying doses of GA, 3-HT, and QUE, subsequently evaluating enzymatic activity of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). Galanthamine HBr was used as a positive control. All three phenolic compounds exhibited elevated ΔOD/min values for BChE inhibition compared to the negative control (ethanol). GA and QUE inhibited AChE, though with lower potency than galanthamine; at 1 mM, GA and QUE achieved 79.23% and 80.98% inhibition, respectively, compared to 98.34% for galanthamine. Interestingly, the effect of 3-HT on AChE was inversely related to the dose. The results indicate that GA and QUE modulate cholinesterase activity in vivo, consistent with our prior in vitro reports. This study also provides the first in vivo evidence of 3-HT’s ChE-modulating activity in Drosophila within a whole-organism model.

1. Introduction

Cholinesterase (ChE) enzyme family, consisting of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), play a significant role in the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) due to their involvement in acetylcholine (ACh) breakdown, a crucial neurotransmitter for memory and learning. In AD, there is a marked loss of cholinergic neurons and a decrease in overall AChE activity in the cortex, contributing to cognitive decline [1,2]. Interestingly, AChE activity is observed to increase around amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the pathological hallmarks of AD, suggesting potential non-cholinergic functions in disease progression, such as involvement in amyloid-beta (Aβ) fibrillogenesis [3]. The inhibition of AChE is a cornerstone of current symptomatic treatment for AD [4]. This therapeutic strategy is directly rooted in the ‘cholinergic hypothesis’, which posits that the progressive loss of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and the consequent decline in ACh levels are critical contributors to the cognitive deficits observed in AD. Mechanistically, ChE inhibitors (ChEIs) function by reversibly binding to the active site of the AChE enzyme in the synaptic cleft. Under normal conditions, AChE rapidly hydrolyzes the neurotransmitter ACh, terminating its signal. By blocking this breakdown, ChEIs increase the concentration and prolong the duration of action of ACh in the synaptic cleft [5]. This enhanced cholinergic transmission facilitates improved communication between neurons, particularly in brain regions vital for memory (hippocampus) and executive function (cortex). The resulting boost in neurochemical signaling can lead to the temporary alleviation or stabilization of core cognitive symptoms, including memory impairments, deficits in attention, and difficulties with activities of daily living [6].

It is crucial to note, however, that ChEIs such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galanthamine are not disease-modifying agents. They do not halt the underlying neurodegeneration driven by pathologies like Aβ plaque accumulation or neurofibrillary tangle formation. Instead, they act as a pharmacological scaffold, providing symptomatic relief and improving the quality of life for many patients, often for a period of 6 to 12 months on average, before the disease’s progression overtakes the drug’s benefits [7]. This fundamental limitation underscores the pressing need for novel therapeutic agents that not only manage symptoms but also address the root causes of neuronal death.

In this context, naturally occurring polyphenols have attracted increasing attention due to their multifaceted biological properties relevant to brain health, including antioxidant capacity, modulation of neuronal signaling pathways, attenuation of neuroinflammation, and inhibition of key enzymes such as AChE and BChE [8,9,10]. Polyphenols such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, and catechols are particularly notable for their ability to cross the blood–brain barrier and interact with molecular targets implicated in neurodegenerative cascades, making them interesting candidates for screening in AD-related research.

Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, occupies a pivotal role in modern biomedical research. Its status was cemented when it became the first complex organism to have its genome fully sequenced in 2000, a landmark achievement that revealed a remarkable genetic conservation with humans. Approximately 75% of genes known to be associated with human diseases have a recognizable homolog in the Drosophila genome [11,12]. This profound genetic similarity means that fundamental cellular processes—such as neuronal signaling, oxidative stress response, and programmed cell death—are highly conserved between flies and humans. This, combined with a suite of practical experimental advantages, establishes Drosophila as an ideal model organism for studying human biology and disease processes, particularly neurodegenerative diseases. Its short lifespan, typically 70–90 days, allows for the rapid assessment of age-related phenomena and compound effects over an entire life cycle within a feasible experimental timeline. Furthermore, its simple anatomy, well-characterized development, and powerful, versatile genetic tools enable researchers to manipulate specific genes with high precision to model human diseases. The ability to produce a large number of offspring from a single cross facilitates robust statistical analysis and high-throughput screening of therapeutic compounds. Critically for neuropharmacology, the brain of D. melanogaster, while simpler, shares core architectural and functional features with the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), including the use of analogous neurotransmitters and the presence of a blood–brain barrier. It has been instrumental in elucidating cellular processes central to neurodegeneration, such as protein aggregation and synaptic dysfunction. Most relevant to this study, D. melanogaster possesses a well-characterized cholinergic system, including an AChE enzyme that is structurally and functionally analogous to its vertebrate counterparts, serving the same essential role in terminating cholinergic transmission. Consequently, Drosophila has emerged as a pre-eminent and efficient in vivo system for the primary screening of natural molecules as potential ChE inhibitors, bridging the gap between simple in vitro assays and complex, costly mammalian models, thus accelerating discovery in neurobiological research [13,14,15]. Moreover, D. melanogaster is a model organism that offers promising advantages in preclinical studies of nutrigenomics research, which lies at the intersection of diet, health, and genomics [16,17]. Researchers routinely use D. melanogaster to evaluate the anti-aging effects of natural molecules and plant extracts and their utility for human application by incorporating them into the flies’ food [18,19,20]. Within this nutrigenomic framework, polyphenolic compounds are of particular interest because dietary exposure can directly modulate neuronal resilience, stress response pathways, and enzymatic systems involved in neurodegeneration [21,22,23]. For this purpose, we aimed to test the ChE-modulating potential of three selected plant phenolics, i.e., gallic acid (GA), 3-hydroxytyrosol (3-HT), and quercetin (QUE). Their selection was based on their strong ChE inhibitory activity that we recently reported [24].

In this study, the measurement of ChE activity was conducted using adult Drosophila head homogenate after larval feeding. This approach constitutes a standard biochemical method widely used in both classical and contemporary Drosophila neurotoxicology studies [13,25,26,27]. Additionally, these compounds represent three distinct classes of polyphenols—phenolic acids (GA), catecholic alcohols (3-HT), and flavonoids (QUE)—each of which has been previously associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other biological effects in various model systems [28,29,30,31]. Their evaluation in an in vivo Drosophila model may thus provide valuable insights into their potential as ChE-targeting nutraceutical candidates.

2. Results

Galanthamine, which was used as a reference drug in D. melanogaster model and antiamnesic activity determination studies by passive avoidance test in mice, is an alkaloid-type of a clinical drug initially obtained from several medicinal plants such as Galanthus nivalis L., Narcissus spp., and Lycoris radiata Herb. in the Amaryllidaceae family. Furthermore, galanthamine is a competitive and selective AChE inhibitor having brain-selective properties like rivastigmine and donepezil, used in the clinical treatment of AD and is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme.

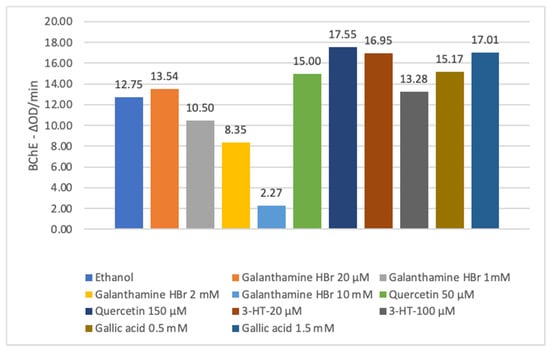

In D. melanogaster model, GA, 3-HT, and QUE, identified as active inhibitors based on in vitro AChE and BChE inhibition assays, and the positive control were used at concentrations selected according to the literature data, as given in Table 1. The results of AChE and BChE activity measurement (ΔOD/min) of the phenolic compounds, positive and negative controls are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Galanthamine HBr, which was used as the positive control, for AChE and BChE inhibition, showed a higher ΔOD/min value than ethanol at doses as low as 20 μM; when the flies were fed with higher concentrations, such as 1 mM and 2 mM, it was found that the activity compared to ethanol and the effect increased in direct proportion to the dose. At a concentration of 10 mM, the activity increased significantly. Among the phenolic compounds tested, QUE and GA inhibited AChE, though with lower efficacy compared to galanthamine. At 1 mM, QUE and GA inhibited AChE by 80.98% and 79.23%, respectively, whereas galanthamine achieved 98.34% inhibition. In contrast, 3-HT exhibited an unexpected effect on AChE that was inversely proportional to the dose. In the BChE inhibition assay, all phenolic compounds tested displayed higher ΔOD/min values than that of ethanol (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1.

ChE inhibitory activity of gallic acid (GA), 3-hydroxytyrosol (3-HT), and quercetin (QUE).

Figure 1.

ΔOD/min values of selected phenolic compounds, positive and negative controls for AChE activity measurement in D. melanogaster model.

Figure 2.

ΔOD/min values of selected phenolic compounds, positive and negative controls for BChE activity measurement in D. melanogaster model.

Experiments with different doses of galanthamine, used as a reference drug in D. melanogaster, concluded that the effect and consistency were observed when the dose used was kept above a certain threshold. It is noted that, when studies are conducted with higher doses of phenolic compounds, their efficacy can be measured, and the results are compared.

Statistical Results

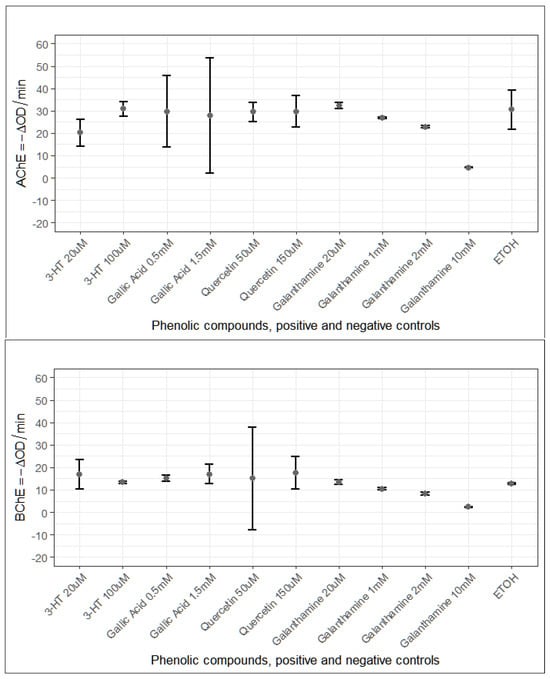

Evaluation of both enzymes showed that the compounds did not affect AChE and BChE in the same manner. For AChE, the ΔOD/min measurements were largely similar across the different compound–dose groups, and only a few comparisons produced low p-values (roughly between 0.01 and 0.04) (Figure 3). These scattered signals do not form a convincing trend, yet they leave room for the possibility of minor or early-stage influences that may not be fully captured under the present experimental conditions. Overall, AChE activity appeared stable at the concentrations tested. In contrast, BChE responded more distinctly. Several doses of 3-HT, GA, and QUE exhibited lower ΔOD/min values, when compared with 10 mM galanthamine, and these reductions repeatedly yielded low p-values. Although the small number of samples warrants a cautious interpretation, the fact that similar patterns emerged across different compounds suggests that BChE may be more sensitive to the treatments than AChE, showing a reproducible tendency toward reduced activity.

Figure 3.

Summary of AChE and BChE activities (ΔOD/min) in response to phenolic compounds and control treatments. Each panel shows the mean ± 95% confidence intervals for two doses of 3-HT (20 µM, 100 µM), GA (0.5 mM, 1.5 mM) and QUE (50 µM, 150 µM), together with the galanthamine positive controls tested at 20 µM, 1 mM, 2 mM, and 10 mM. EtOH served as the negative control. Panel A illustrates the responses of AChE, while Panel B displays the corresponding BChE measurements. In both enzymes, data points represent group means, and vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals, enabling direct comparison of treatment-related changes across compounds and concentrations.

While the effects on AChE were modest, the consistent and dose-responsive inhibition of BChE by all three phenolics suggests a preferential interaction with this enzyme in vivo. The inverse dose–response observed for 3-HT on AChE highlights a complex, possibly hormetic or metabolically mediated regulation unique to this catechol-containing phenolic.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates that GA, 3-HT, and QUE modulate ChE activity in a D. melanogaster model following larval exposure. While the model does not incorporate genetic or induced neurodegenerative pathology, the observed enzymatic modulation may inform future research into the potential application of these compounds in neurodegenerative disease models, where ChE activity is a key therapeutic target. As indicated by earlier studies in the scientific literature on D. melanogaster, chemical or nutritional interventions during the larval stage have been demonstrated to produce enduring effects on adult neurophysiology, behavior, and metabolism. In line with this perspective, whole-head homogenates were used to capture the integrated effect of phenolic exposure on ChE activity [13,17,32,33]. While our study demonstrates the in vivo ChE modulatory effects of GA, 3-HT, and QUE in a whole-organism model, it is important to consider the role of pharmacokinetics. The observed enzymatic activities in head homogenates represent the net outcome of direct enzyme inhibition, potential compensatory mechanisms, and the complex processes of compound absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). Without direct measurement of the parent compounds and their metabolites within the Drosophila brain, it is challenging to definitively ascertain whether the biological activity stems from the original phenolics or their bioactive derivatives. Our following interpretation of these enzymatic data is based on the analysis of whole-head homogenates, which reflect the total ChE activity in the Drosophila brain. While this approach provides a valuable integrated measure, it is a foundational step that justifies further mechanistic inquiry.

The effective inhibition at the low dose (20 µM) might trigger a compensatory upregulation of AChE gene expression or protein synthesis. At the higher dose (100 µM), this compensatory mechanism might be fully realized, resulting in a net AChE activity level similar to the control. The fly’s nervous system may perceive 3-HT as a cholinergic stressor and react by increasing AChE production to counteract it. Previously, GA, QUE, and limonene were assessed for their antigenotoxic and antioxidant effects in adult male flies of D. melanogaster Oregon-K (ORK) strain, which received a 10% sucrose solution containing urethane (20 mM), GA, QC, and limonene for 72 hours [34]. Adult and larval feeding experiments revealed a significant decrease in the frequencies of sex-linked recessive lethal (SLRL) mutations across all germ cell stages when flies were co-treated with urethane and test phytochemicals, compared to flies treated with urethane alone. Moreover, GA, QUE, and limonene also caused a reduction in malondialdehyde levels in the larvae of D. melanogaster. In another study with D. melanogaster, a number of phenolic compounds including GA, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, coumaric acid, propyl gallate, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, and epigallocatechin gallate effectively counter paraquat toxicity, successfully protecting and rescuing flies, while significantly restoring impaired climbing capability [35]. The authors concluded that these polyphenols show promise as natural agents capable of mitigating the effects of stressful stimuli, suggesting potential relevance for conditions like Parkinson’s disease (PD).

It was also reported that a dual therapeutic strategy combining gene silencing of neuronal death pathways with antioxidant intervention in the D. melanogaster model, such as GA, holds a significant promise for ameliorating PD by protecting dopaminergic neurons from oxidative stress [36]. The study by Ogunsuyi et al. strongly supported the potential of GA as a promising natural compound for the management of AD, effectively mitigating Aβ-induced oxidative stress and modulating key enzyme activities within a transgenic D. melanogaster model [37], which was in accordance with our data.

AChE activity can be modulated by the cellular redox environment. 3-HT is a well-known polyphenol particularly present in Olea aeuropea L. (olive tree) and is considered among olive oil biophenols. It is a potent antioxidant, but like many polyphenols, it can act as a prooxidant under specific conditions (e.g., high concentrations, presence of metal ions). Although a few studies reported the neurobiological effects of 3-HT, it has not been tested so far in the D. melanogaster model according to our literature survey. However, 3-HT has been reported to suppress age-linked rise in mitochondrial levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [38]. A particularly notable finding was the inverse dose–response relationship of 3-HT on AChE activity. In contrast to the relatively stable effects of GA and QUE, the inhibitory potential of 3-HT diminished at the higher concentration. This paradoxical behavior suggests a complex, system-level interaction distinct from the direct enzyme inhibition typically associated with phenolic compounds. We herein hypothesize that this may be due to several non-exclusive mechanisms: (1) a hormetic or biphasic response, where the low dose induces an adaptive beneficial effect that is lost at a higher dose; (2) differential metabolism, where the low dose yields an active metabolite while the high dose saturates this pathway or promotes the formation of an inactive product; or (3) a compensatory upregulation of AChE expression by the fly in response to the initial inhibition. The catechol structure of 3-HT, which renders it a dopamine analog and a substrate for specific metabolic enzymes, may underpin this unique behavior, which is not observed with GA or QUE. This finding underscores the importance of comprehensive dose-ranging studies for plant phenolics, as their effects may not be linear and could reveal narrow, optimal therapeutic windows. On the other hand, at 20 µM, 3-HT may act as an antioxidant, creating a reducing environment that subtly inhibits AChE, which contains critical cysteine residues. At 100 µM, it might generate low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which could oxidize and slightly activate AChE or oxidize other cellular components that indirectly affect AChE activity, thereby counteracting its own inhibitory effect. Thus, we may hypothesize that, at the lower dose (20 µM), the parent 3-HT may exert a direct inhibitory effect or induce a beneficial hormetic response. However, at the higher dose (100 µM), metabolic pathways may become saturated or shift towards the production of methylated or conjugated metabolites (e.g., homovanillyl alcohol) which could possess significantly reduced AChE inhibitory activity or even opposing effects. This differential metabolism could elegantly explain the loss of inhibitory effect at the higher concentration, a phenomenon not observed with the other tested phenolics. While the precise mechanism remains to be fully elucidated, we also propose several non-exclusive hypotheses that could explain this effect. First, the catechol structure of 3-HT renders it a potent antioxidant, but it can also exhibit prooxidant activity under specific conditions, such as at higher concentrations or in the presence of metal ions. It is plausible that at 20 µM, 3-HT acts as an antioxidant, creating a reducing environment that subtly inhibits AChE. In contrast, at 100 µM, it might generate low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that could oxidize and slightly activate AChE or oxidize other cellular components that indirectly affect AChE activity, thereby counteracting its own inhibitory effect. Alternatively, effective inhibition at the low dose might trigger a compensatory feedback mechanism, leading to an upregulation of AChE gene expression or protein synthesis. For this part, we should underline that these proposed mechanisms—a redox-mediated biphasic effect, compensatory gene upregulation, and differential metabolism—are not mutually exclusive and provide a framework for future studies. Direct experimental validation through quantification of ROS, AChE transcript levels, and 3-HT metabolite profiling in the Drosophila brain is essential to distinguish between these possibilities.

QUE, stated to be among the strongest geroprotectors of plant origin, has been tested for various purposes in D. melanogaster [39]. For instance, Proshkina et al. (2016) [40] studied long-term and short-term effects of QUE, (-)-epicatechin, and ibuprofen consumption on the lifespan, resistance to stress factors (i.e., paraquat, hyperthermia, γ-radiation, and starvation), along with age-dependent physiological parameters (locomotor activity and fecundity) of the male and female individuals of D. melanogaster. Although QUE and (-)-epicatechin did not display any effect on its long-term lifespan, QUE, (-)-epicatechin, and ibuprofen lessened the spontaneous locomotor movement of males, but were not effective on stimulated the physical activity and fecundity of the females. The authors suggested that these three compounds possessed geroprotective activity by motivating stress responses via pro-longevity mechanisms. In another study in D. melanogaster, decreased mesor values of negative geotaxis, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione S-transferase (GST) and glutathione (GSH) were observed in H2O2, while increased mesor values of oxidative stress indicators, e.g., thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and protein carbonyl content and reversibility of rhythmic characteristics were evident after QUE treatment. The way in which QUE may be able to balance oxidant and antioxidant levels during periods of oxidative stress could be linked to its effect on the body’s rhythmic processes. QUE has been reported to be able to intervene in the pathogenesis of AD by reducing the toxicity of Aβ in the AD model of D. melanogaster [41]. The study revealed it could also restore genes perturbed by Aβ accumulation. Exposure to paraquat was followed by an increase in lifespan and enhancement of motor activities in D. melanogaster flies that had been fed a diet containing curcumin, QUE, Sanguisorba officinalis, and Curcuma zedoaria extracts [42]. The expression levels of several genes associated with antioxidant and anti-aging effects, including SOD1, SOD2, CAT, GSTD1 and MTH, were modulated by these compounds. Likewise, the same treatments of phytochemicals to flies had a positive effect on other oxidative stress index factors, such as ROS levels and SOD. Conversely, no substantial impacts on CAT activity were detected. While all three phenolics are well-known antioxidants, their redox potentials and metal-chelating properties differ. GA and QUE might maintain their antioxidant capacity across the tested doses without tipping into a prooxidant role in this specific model, leading to their more stable, albeit weak, inhibitory profile. It might also be ventured that GA and QUE are known to be metabolized, but their primary inhibitory activity likely comes from the parent compounds themselves. Their metabolism might be more linear and less likely to produce metabolites with opposing activities compared to the catechol-containing 3-HT, which is highly susceptible to modifications like methylation (e.g., by COMT).

The ChE-modulating effects observed in this study for QUE, GA, and 3-HT can be further contextualized by examining structurally related phenolic compounds reported in the literature. Notably, QUE isomers and various isocoumarin derivatives have been extensively documented for their strong antioxidant and neuroprotective properties, offering valuable mechanistic parallels [43,44]. For instance, similar to our findings with QUE, certain isocoumarins have demonstrated significant ChE inhibitory activity, suggesting a shared capacity among polyphenolic structures to interact with these enzymatic targets. Furthermore, the potent free-radical scavenging and anti-apoptotic effects reported for these compound classes align closely with the known antioxidant mechanisms of GA, 3-HT, and QUE, which are believed to mitigate oxidative stress—a key contributor to neurodegenerative pathogenesis. The common theme across these studies, including our own, is the ability of such phenolic compounds to engage in multi-target actions. This includes not only direct enzyme inhibition and radical quenching but also the modulation of critical signaling pathways, such as the Nrf2/ARE and PI3K/Akt cascades. Therefore, the effects we report herein for QUE, GA, and 3-HT are consistent with a broader pattern of bioactivity exhibited by plant-derived phenolics. This comparative insight reinforces the mechanistic plausibility of our findings and underscores the research interest in this chemical class in targeting the complex pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases.

Finally, despite the valuable insights provided by our study, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the use of whole-head homogenates, while informative for measuring overall enzymatic activity, does not allow for the spatial resolution of effects within specific brain regions or neuronal circuits, which may exhibit differential responses to the phenolic treatments. It is acknowledged that the adult head homogenate method is not capable of resolving region-specific modulation. It is recommended that future studies address this issue by conducting assays specifically designed to target brain tissue [27,45,46].

Secondly, the exclusive focus on ChE inhibition, although well-justified, means that other potentially neurobiologically relevant mechanisms—such as anti-apoptotic effects, modulation of Aβ or tau pathology, and impacts on neuroinflammation—remain unexplored in this model. Furthermore, the observed effects are the net result of the compounds and their potential metabolites; without pharmacokinetic data on the absorption and distribution of these phenolics in the Drosophila brain, it is difficult to ascertain whether the activity is due to the parent compounds or their bioactive derivatives. Actually, we should summarize that a key limitation is the lack of pharmacokinetic data on the absorption and distribution of these phenolics in the Drosophila brain. Although the measured activities are due to the parent compounds or their bioactive metabolites, future studies employing advanced analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to quantify the levels of these phenolics and identify their major metabolites in the fly head homogenates are crucial. This would directly clarify the relationship between compound exposure, metabolism, and the observed pharmacological effects, moving from correlation to causation. Finally, while the D. melanogaster model is accepted as a powerful tool for initial screening, the translational relevance of these findings ultimately requires validation in mammalian models of neurodegeneration. Addressing these limitations in future work will be crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic potential of these plant phenolics. Therefore, despite these constraints, our findings offer the first direct evidence for the in vivo ChE-inhibiting effects of 3-HT in a whole-organism model and firmly establish a groundwork for subsequent mechanistic and translational investigations.

Expanding the translational relevance, studies conducted in Drosophila have demonstrated that QUE supplementation reverses shortened lifespan and impaired locomotor activity in an AD model [41] and that QUE, GA, and limonene exerted antioxidant and antigenotoxic effects against urethane-induced genotoxicity [34]. Consistent with these findings, extensive research in mammalian models also supports the neuroprotective role of this class of phytochemicals. For instance, QUE, donepezil, and their combination improved cognitive performance in rats in tests such as the Morris water maze, passive avoidance, and elevated plus maze [47]. Additional studies have reported that QUE improved memory, learning, and cognitive performance and exhibits neuroprotective properties in various mouse and rat AD models [48,49,50,51]. GA has similarly been shown to inhibit Aβ oligomerization, improve cognitive function in a rat model of AD [52], reverse scopolamine-induced amnesia in mice [53], and enhance passive avoidance memory alone or in combination with physical exercise [54].

Furthermore, studies in zebrafish, an intermediate vertebrate model, also demonstrate comparable beneficial effects. QUE improved behavioral outcomes in streptozotocin-induced dementia [55] and reversed LPS-induced neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. HT ameliorated high-fat-diet-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [56], and GA prevented ethanol-induced oxidative stress in the zebrafish brain [57]. Additionally, QUE and rutin prevented scopolamine-induced memory impairment without affecting locomotor activity [58]. Moreover, findings from a 2024 thesis titled “Investigation on anti-Alzheimer’s effect of several phenolic compounds of plant origin using in vitro, in vivo and in silico experimental models” further support the cross-species neuroprotective effects of these phytochemicals [59].

Taken together, these findings across Drosophila, rodents, and zebrafish consistently demonstrate the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimutagenic activities, along with effects on neurobiological mechanisms of QUE, GA, HT, and related compounds. We have incorporated these comparative insights into the revised manuscript to enhance the translational relevance and to underscore the cross-species applicability of our findings.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phenolic Compounds

GA, 3-HT, and QUE, as well as galanthamine HBr, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) with a purity of over 95%.

4.2. AChE and BChE Inhibitory Activity Measurements in Drosophila melanogaster

The adult head homogenates were used as the enzyme source, reflecting total cholinesterase activity in the Drosophila central nervous system (CNS). This approach is a standard in vivo biochemical model for assessing neuroactive compounds in D. melanogaster. For this aim, AChE and BChE inhibitory activity measurements were performed by a modified spectrophotometric method developed by Ellman et al. (1961) [26]. The head homogenates of adult D. melanogaster individuals fed on a medium containing the samples were used as the enzyme source. Acetylthiocholine iodide (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and butyrylthiocholine chloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as substrates for the determination of AChE and BChE inhibition, respectively, and DTNB (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the coloring agent. Briefly, 110 μL of distilled water, 20 μL of 1M tris-HCl (5 mM EDTA, pH: 8) and 10 μL of 0.5 mM DTNB (prepared in 1% sodium citrate) were added to the 96-well microplate well. Ten μL of fly head homogenate as enzyme source and 50 μL of acetylthiocholine iodide (10 mM) used as substrate for AChE inhibition measurement were added to the wells, and absorbance changes in the microplates were read on a 96-well ELISA microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x microplate reader, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 412 nm for 5 min. For BChE activity measurement, the solutions were added to the wells in the same manner, and butyrylthiocholine chloride was used as substrate. Each sample was run in three parallel experiments, and the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the ΔOD/min values obtained from these experiments were reported at the end of the period.

4.3. Data Processing for Enzyme Inhibition Assays

The measurements and calculations were evaluated using Softmax PRO 4.3.2.LS software (https://www.moleculardevices.com/products/microplate-readers/acquisition-and-analysis-software/softmax-pro-software, accessed on 6 January 2026). The percentage of inhibition of AChE and BChE was determined by comparison of the rates of reaction of test samples relative to blank samples. The extent of the enzymatic reaction was calculated using the following equation: I% = (C − T)/C × 100, where I% represents the enzyme activity as a percentage of inhibition. C value is the absorbance of the control solvent (blank) in the presence of an enzyme, where T is the absorbance of the tested sample or positive control/reference inhibitor (i.e., galanthamine HBr) in the solvent in the presence of the enzyme. Data are expressed as average inhibition ± SD, and the results were taken from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

4.4. Drosophila melanogaster Model

4.4.1. Drosophila melanogaster Strain

All experiments in this study were performed using the wild-type Berlin-K strain of Drosophila melanogaster. Neurodegenerative mutants were not used at this stage because disease-related alterations in ChE activity could interfere with the detection of compound-specific effects. Berlin-K is a widely utilized wild-type strain in laboratory research [60] and is particularly notable for its low copy number (five copies) of the heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) genes. This characteristic renders it a valuable model for studies addressing stress tolerance and environmental adaptation [61]. Furthermore, Berlin-K has been utilized in transcriptomic analyses investigating alterations in gene expression under diverse environmental conditions [62]. It is evident that, when considered as a whole, these characteristics establish Berlin-K as a noteworthy exemplar for elucidating the functional consequences of genetic variation, as well as the mechanisms that underpin aging and adaptation biology. In the present study, this strain was maintained in the collection of the Functional and Evolutionary Genetics Laboratory, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Hacettepe University (Ankara, Türkiye). The application of the aforementioned phenolic compounds has been used to evaluate AChE and BChE phenotypes.

4.4.2. Maintenance of Flies and Head Homogenate Preparation

Inbred stocks of Berlin-K and sets of experimental crosses were maintained in a climate chamber with constant temperature at 25 ± 1 °C, average relative humidity of 65% and a 12 h day–night cycle, with transfers at 16-day intervals. Stocks and experimental crosses were performed in tubes and bottles containing standard Drosophila medium [63]. The tested phenolic compounds, i.e., GA, 3-HT, and QUE, which were found to be active by in vitro AChE and BChE inhibition assays, as well as galanthamine HBr (positive control) and ethanol (negative control), were proceeded to larval feeding. The application of phenolic compounds was conducted during the third larval stage, a period of critical neurodevelopment that has been shown to have persistent effects on adult physiology and neurobiology. During this stage, the CNS undergoes significant reorganization [17,32,33].

To obtain larvae of the same age to be fed with these compounds, pre-stocks were made in standard Drosophila medium by modifying the method developed by Graf et al. (1984) [64]. The 5–7-day-old male and female individuals from Berlin-K stock were placed together in new culture bottles and allowed to lay eggs for 8 h. Third-stage larvae were obtained by washing these flasks in a fine mesh metal sieve after 72 h. When the 72 ± 4 h old larvae were ready, two concentrations of selected three phenolic compounds and four concentrations of galanthamine HBr (Table 2) were prepared as compatibly determined from the literature. All compounds were dissolved in 96% ethanol at a concentration of 1%. One part (4.5 g) of Drosophila instant medium (Carolina-Formula 4-24-Drosophila Instant Medium) was placed in 2.5 × 9.5 cm polystyrene tubes and soaked with different concentrations of phenolic compounds and galanthamine HBr (9 mL each). One small spatula full of larvae separated on metal sieves (approximately 50 larvae) was placed in each tube prepared in this way, and the mouths of the tubes were closed with sponge stoppers. All tubes were removed to a constant temperature cabinet at 25 ± 1 °C. Third-instar larvae were fed on media prepared with phenolic compounds and galanthamine HBr for approximately 48 h, until pupation, and then chronically exposed to the applied compounds. Third-instar larvae, approximately 72 h old, were exposed to phenolic compounds for feeding, and the pupae were then allowed to develop. Subsequent to the completion of pupation, the emergence of adults was monitored; immediately after eclosion, the flies were anaesthetised with CO2, transferred into 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes in groups of 15 individuals per concentration, and stored at −80 °C until homogenate preparation. Adult head homogenates were utilized as an enzyme source. This method facilitates a comprehensive assessment of total ChE activity in Drosophila, which is consistent with recent studies applying the Ellman method to determine AChE/BChE levels. The method has been recognized in the relevant literature as a reliable analytical technique [27,47].

Table 2.

Phenolic compounds and positive control concentrations were fed to 72 h/age D. melanogaster larvae.

For D. melanogaster Berlin-K strain, a total of 120 D. melanogaster adult heads were obtained in the treatment group (3 phenolic compounds × 2 different concentrations × 15 individuals: 90 individuals), negative control (ethanol: 15 individuals), and reference (galanthamine HBr: 15 individuals). Drosophila heads frozen at 80 °C were dissected on ice, transferred to a mortar containing liquid nitrogen, and crushed. Then, 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH: 7.4) containing 10 mL of 0.5% Triton X-100 per gram of heads was added and centrifuged at +4 °C for 15 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatants obtained were used for in vitro AChE and BChE inhibitory activity assay.

4.5. Statistical Evaluation

All statistical analyses were performed in R [72]. QUE, 3-HT, and GA were administered at two concentrations, and each dose was evaluated independently. For both AChE and BChE, ΔOD/min values from each compound–dose group were compared with all corresponding Galanthamine concentrations and with the EtOH control to assess potential shifts in enzymatic activity. Because the data did not satisfy normality assumptions and several groups had limited sample sizes, pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test [73,74,75]. Each dose was tested separately against the Galanthamine panel and, in a second step, against EtOH. To account for repeated testing within each comparison set, p-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure [73]. Statistical conclusions were based on the adjusted p-values, and each ΔOD/min measurement was treated as an independent observation.

While this study establishes the in vivo cholinesterase inhibitory activity of GA, 3-HT, and QUE, several limitations should be noted. The use of whole-head homogenates, though informative, does not resolve region-specific effects within the Drosophila brain. Future studies should employ immunohistochemical or region-specific enzymatic assays to address this. Additionally, behavioral readouts such as climbing performance, learning, and memory tests would strengthen the functional relevance of the observed enzymatic changes. Further, pharmacokinetic profiling using advanced analytical techniques could clarify whether the parent compounds or their metabolites are responsible for the observed activities.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that GA, 3-HT, and QUE modulate ChE activity in a Drosophila model, with notable inhibition of BChE and a complex, non-linear effect of 3-HT on AChE. These findings validate prior in vitro results and provide a foundational rationale for further mechanistic investigation. The results indicate that while these compounds do not inhibit AChE as potently as galanthamine, they still exhibit measurable effects on key ChE enzymes. Specifically, all three phenolic compounds demonstrated higher ΔOD/min values for BChE inhibition compared to the negative control. However, their effects on AChE were less pronounced, with GA and QUE showing ΔOD/min values close to the negative control. An interesting finding was that 3-HT’s effect on AChE was inversely proportional to the dose. We suggest that conducting future studies with higher doses of these phenolic compounds may be necessary to fully assess their efficacy. This research contributes to the existing literature by confirming the cholinesterase-modulating properties of GA and QUE within a living organism model. Additionally, the study pioneers the assessment of 3-HT’s activity in the D. melanogaster model, opening a new avenue for research on this compound. Ultimately, our findings suggest that these plant phenolics warrant further investigation in models of neurodegenerative disease, where ChE modulation is relevant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.E.O. and G.E.; methodology, T.U.A., F.S.S.D., I.E.O., M.G., G.I.E. and G.E.; investigation, T.U.A., F.S.S.D., M.G., G.I.E. and G.E.; writing—original draft preparation, I.E.O. and G.E.; writing—review and editing, T.U.A., F.S.S.D., I.E.O., M.G., G.I.E. and G.E.; supervision, I.E.O.; project administration, I.E.O.; funding acquisition, I.E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Project Unit of Gazi University (Ankara, Türkiye) under the grant number: 02/2019-31.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Ergi Deniz Özsoy and Murat Yılmaz from the Functional and Evolutionary Genetics Laboratory at Hacettepe University for their valuable contributions to this study. The authors would like to thank the Scientific Research Project Unit of Gazi University (Ankara, Türkiye) for the project grant provided for this work. This study is a part of the Ph.D. thesis of Tugba Ucar Akyurek completed in May 2024 at the Department of Pharmacognosy, Institute of Health Sciences, Gazi University, Ankara, Türkiye.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with Inovabella Biotechnology and R&D Industry and Trade Limited Company.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| BChE | Butyrylcholinesterase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| ChE | Cholinesterase |

| ChEI | Cholinesterase inhibitor |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DTNB | 5,5-Dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) |

| GA | Gallic acid |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| 3-HT | 3-Hydroxytyrosol |

| HBr | Hydrobromide |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| QUE | Quercetin |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

References

- Geula, C.; Darvesh, S. Butyrylcholinesterase, cholinergic neurotransmission and the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Today 2004, 40, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Sivaprakasam, P.; Vijendra, P.; Waseem, M.; Pandurangan, A.K. A Recent update on pathophysiology and therapeutic interventions of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 3428–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ayllón, M.S.; Small, D.H.; Avila, J.; Sáez-Valero, J. Revisiting the role of acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease: Cross-talk with P-tau and β-amyloid. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2011, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, G.D.; Luca, A.; Rusu, R.N.; Bild, V.; Beschea Chiriac, S.I.; Solcan, C.; Bild, W.; Ababei, D.C. Alzheimer’s disease pharmacotherapy in relation to cholinergic system involvement. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, K. Cholinesterase inhibitors as Alzheimer’s therapeutics. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, M.; Dubey, R. Target enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D.; Vafeiadou, K.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Rendeiro, C.; Spencer, J.P. The neuroprotective potential of flavonoids: A multiplicity of effects. Genes. Nutr. 2008, 3, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, J.P. The impact of fruit flavonoids on memory and cognition. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Menichini, F.; Menichini, F. Natural products and their derivatives as cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders: An update. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 1209–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, U.B.; Nichols, C.D. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011, 63, 411–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangler, M.F.; Yamamoto, S.; Bellen, H.J. Fruit flies in biomedical research. Genetics 2015, 199, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, P.E.; Batista, J.E.S.; Souza, L.R.; Dafre, A.L.; Farina, M.; Kuca, K.; Posser, T.; Pinto, P.M.; Boldo, J.T.; Franco, J.L. Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for screening acetylcholinesterase reactivators. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2024, 87, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, S.J.; Long, A.D. Discovery of malathion resistance QTL in Drosophila melanogaster using a bulked phenotyping approach. G3 2022, 12, jkac279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsintzas, E.; Niccoli, T. Using Drosophila amyloid toxicity models to study Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2024, 88, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruden, D.M.; Lu, X. Evolutionary conservation of metabolism explains how Drosophila nutrigenomics can help us understand human nutrigenomics. Genes. Nutr. 2006, 1, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baenas, N.; Wagner, A.E. Drosophila melanogaster as an alternative model organism in nutrigenomics. Genes. Nutr. 2019, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, K.; Tiwari, A.K. Drosophila melanogaster “a potential model organism” for identification of pharmacological properties of plants/plant-derived components. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 89, 1331–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Min, K.J. Betulinic acid increases the lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster via Sir2 and FoxO activation. Nutrients 2024, 16, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, E.; Du, D.; Ni, H.; Zhu, K.; Hu, F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, D. Regulation and mechanism of Bletilla striata polysaccharide on delaying ageing in Drosophila melanogaster. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310, 143382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D. Dietary polyphenols as modulators of brain functions: Biological actions and molecular mechanisms underpinning their beneficial effects. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2012, 2012, 914273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Carota, G.; Caruso, G.; Micek, A.; Frias-Toral, E.; Giampieri, F.; Brito-Ballester, J.; Velasco, C.L.; Quiles, J.L.; Battino, M.; et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of polyphenols: Implications for cognitive function. EXCLI J. 2025, 24, 1262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silva, R.F.; Pogačnik, L. Polyphenols from food and natural products: Neuroprotection and safety. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar Akyürek, T.; Şenol Deniz, F.S.; Süntar, I.; Eren, G.; Ulutaş, O.K.; Orhan, I.E. 3-Hydroxytyrosol as a phenolic cholinesterase inhibitor with antiamnesic activity: A multi-methodological study of selected plant phenolics. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1640034. [Google Scholar]

- Gnagey, A.L.; Forte, M.; Rosenberry, T. Isolation and characterization of acetylcholinesterase from Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 13290–13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.; Courtney, K.; Andres, V.; Featherstone, R. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedayo, B.C.; Akinniyi, S.T.; Ogunsuyi, O.B.; Oboh, G. In the quest for the ideal sweetener: Aspartame exacerbates selected biomarkers in the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) model of Alzheimer’s disease more than sucrose. Aging Brain 2023, 4, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747, Erratum in Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuia, M.S.; Rahaman, M.M.; Islam, T.; Bappi, M.H.; Sikder, M.I.; Hossain, K.N.; Akter, F.; Al Shamsh Prottay, A.; Rokonuzzman, M.; Gürer, E.S.; et al. Neurobiological effects of gallic acid: Current perspectives. Chin. Med. 2023, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zamora, L. Novel ingredients: Hydroxytyrosol as a neuroprotective agent; what is new on the horizon? Foods 2025, 14, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Bardakci, F.; Surti, M.; Badraoui, R.; Patel, M. Neuroprotective potential of quercetin in Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and amyloid-β aggregation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1593264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Shaw, A.; Lambert, M.; Perry, H.H.; Lowenstein, E.; Valenzuela, D.; Velazquez-Ulloa, N.A. Developmental nicotine exposure affects larval brain size and the adult dopaminergic system of Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Dev. Biol. 2018, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekara, K.T.; Shakarad, M.N. Aloe vera or resveratrol supplementation in larval diet delays adult aging in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011, 66, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, I.; Abraham, S.K. Ameliorative effects of gallic acid, quercetin and limonene on urethane-induced genotoxicity and oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2017, 27, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Del-Rio, M.; Guzman-Martinez, C.; Velez-Pardo, C. The effects of polyphenols on survival and locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster exposed to iron and paraquat. Neurochem. Res. 2010, 35, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Arellano, H.F.; Jimenez-Del-Rio, M.; Velez-Pardo, C. Dmp53, basket and drICE gene knockdown and polyphenol gallic acid increase life span and locomotor activity in a Drosophila Parkinson’s disease model. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2013, 36, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsuyi, O.B.; Oboh, G.; Oluokun, O.O.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Ogunruku, O.O. Gallic acid protects against neurochemical alterations in transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Tradit. Med. 2020, 20, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsour, E.H.; Kumar, M.G.; Kalen, A.L.; Goswami, M.; Buettner, G.R.; Goswami, P.C. MnSOD activity regulates hydroxytyrosol-induced extension of chronological lifespan. Age 2012, 34, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshkina, E.; Koval, L.; Platonova, E.; Golubev, D.; Ulyasheva, N.; Babak, T.; Shaposhnikov, M.; Moskalev, A. Polyphenols as potential geroprotectors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2024, 40, 564–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshkina, E.; Lashmanova, E.; Dobrovolskaya, E.; Zemskaya, N.; Kudryavtseva, A.; Shaposhnikov, M.; Moskalev, A. Geroprotective and radioprotective activity of quercetin, (-)-epicatechin, and ibuprofen in Drosophila melanogaster. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, K.; Fu, T.; Wan, C.; Zhang, D.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Gan, Z.; Yuan, L. Quercetin ameliorates Aβ toxicity in a Drosophila AD model by modulating cell cycle-related protein expression. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 67716–67731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Jung, J.W.; Ahn, Y.J.; Kwon, H.W. Neuroprotective properties of phytochemicals against paraquat-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2012, 104, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minocha, T.; Birla, H.; Obaid, A.A.; Rai, V.; Sushma, P.; Shivamallu, C.; Moustafa, M.; Al-Shehri, M.; Al-Emam, A.; Tikhonova, M.A.; et al. Flavonoids as promising neuroprotectants and their therapeutic potential against Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 6038996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, S.; Piplani, P. Coumarin derivatives as potential inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase: Synthesis, molecular docking and biological studies. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 4587–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakya, B.; Siddique, Y.H. Exploring the neurotoxicity and changes in life cycle parameters of Drosophila melanogaster exposed to arecoline. J. Basic Appl. Zoo. 2018, 79, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, S.J.; Do, H.A.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, M.; Kim, K. The Drosophila model: Exploring novel therapeutic compounds against neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanashetti, L.A.; Taranalli, A.D.; Parvatrao, V.; Malabade, R.H.; Kumar, D. Evaluation of neuroprotective effect of quercetin with donepezil in scopolamine-induced amnesia in rats. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2017, 49, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, Q.; Li, Z.; Dang, M.; Lin, Y.; Hou, X. Activation of Nrf2 signaling by sitagliptin and quercetin combination against β-amyloid–induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Drug Dev. Res. 2019, 80, 837–845. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Munoz-Manco, J.I.; Ramírez-Pineda, J.R.; Lamprea-Rodriguez, M.; Osorio, E.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. The flavonoid quercetin ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease pathology and protects cognitive and emotional function in aged triple-transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Naidu, P.S.; Kulkarni, S.K. Reversal of aging and chronic ethanol-induced cognitive dysfunction by quercetin, a bioflavonoid. Free Radic. Res. 2003, 37, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.M.; Li, S.Q.; Wu, W.L.; Zhu, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.Y. Effects of long-term treatment with quercetin on cognition and mitochondrial function in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajipour, S.; Sarkaki, A.; Farbood, Y.; Eidi, A.; Mortazavi, P.; Valizadeh, Z. Effect of gallic acid on dementia type of Alzheimer disease in rats: Electrophysiological and histological studies. Basic. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, K.; Singh, S.; Mishra, D. Nanoparticle-mediated brain-targeted delivery of gallic acid: In vivo behavioral and biochemical studies for protection against scopolamine-induced amnesia. Drug Deliv. 2013, 20, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, A.; Rabiei, Z.; Setorki, M. Effects of gallic acid and physical exercise on passive avoidance memory in male rat. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 55, e18261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, R.; Ganguly, R.; Singh, A.K.; Rana, H.K.; Pandey, A.K. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective activities of Terminalia bellirica and its bioactive component ellagic acid against diclofenac-induced oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yu, M.; Wu, Y.; Xia, T.; Wang, L.; Song, K.; Zhang, C.; Lu, K.; Rahimnejad, S. Hydroxytyrosol promotes mitochondrial function through activating mitophagy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldin, S.L.; de Pieri Pickler, K.; de Farias, A.C.S.; Bernardo, H.T.; Scussel, R.; da Costa Pereira, B.; Pacheco, S.D.; Dondossola, E.R.; Machado-de-Ávila, R.A.; Wanderley, A.G. Gallic acid modulates purine metabolism and oxidative stress induced by ethanol exposure in zebrafish brain. Purinergic Signal. 2022, 18, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetti, S.; Blank, M.; Capiotti, K.; Piato, A.; Bogo, M.; Vianna, M.; Bonan, C. Quercetin and rutin prevent scopolamine-induced memory impairment in zebrafish. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 217, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar Akyürek, T. Investigation on Anti-Alzheimer’s Effect of Several Phenolic Compounds of Plant Origin Using In Vitro, In Vivo and In Silico Experimental Models. Doctoral Dissertation, Gazi University, Institute of Health Sciences, Department of Pharmacognosy, Ankara, Türkiye, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs, R.A.; Feder, M.E. Natural variation in the expression of the heat-shock proteins Hsp70 in a population of Drosophila melanogaster and its correlation with tolerance of ecologically relevant thermal stress. Evolution 1997, 51, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.G.; Nielsen, M.M.; Loeschcke, V. Evolutionary consequences of variation in expression of the heat shock protein Hsp70. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 5786–5793. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Nolte, V.; Schlötterer, C. Extensive transcriptome changes accompany the adaptation of Drosophila melanogaster to different climates. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015, 7, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Markow, T.A.; O’Grady, P. Drosophila: A Guide to Species Identification and Use; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 215–225. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, U.; Wurgler, F.; Katz, A.; Frei, H.; Juon, H.; Hall, C.; Kale, P. Somatic mutation and recombination test in Drosophila melanogaster. Environ. Mutagen. 1984, 6, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, K.K.; Macedo, G.E.; Rodrigues, N.R.; Ziech, C.C.; Martins, I.K.; Rodrigues, J.F.; de Brum Vieira, P.; Boligon, A.A.; de Brito Junior, F.E.; de Menezes, I.R. Croton campestris A. St.-Hill methanolic fraction in a chlorpyrifos-induced toxicity model in Drosophila melanogaster: Protective role of gallic acid. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 3960170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anter, J.; Tasset, I.; Demyda-Peyrás, S.; Ranchal, I.; Moreno-Millán, M.; Romero-Jimenez, M.; Muntané, J.; de Castro, M.D.L.; Muñoz-Serrano, A.; Alonso-Moraga, Á. Evaluation of potential antigenotoxic, cytotoxic and proapoptotic effects of the olive oil by-product “alperujo”, hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol and verbascoside. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2014, 772, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.P.; Mishra, M.; Sharma, A.; Shukla, A.; Mudiam, M.; Patel, D.; Ram, K.R.; Chowdhuri, D.K. Genotoxicity and apoptosis in Drosophila melanogaster exposed to benzene, toluene and xylene: Attenuation by quercetin and curcumin. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 253, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.C.; Siddique, H.R.; Mathur, N.; Vishwakarma, A.L.; Mishra, R.K.; Saxena, D.K.; Chowdhuri, D.K. Inducèon of hsp70, alteraèons in oxidaève stress markers and apoptosis against dichlorvos exposure in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster: Modulaèon by reacève oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gen. Subj. 2007, 1770, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Y.H.; Mantasha, I.; Shahid, M.; Jyoti, S.; Varshney, H. Effect of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on the cognitive impairments in transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Open Biol. J. 2023, 11, e187503622305290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, Y.H.; Naz, F.; Varshney, H. Comparative study of rivastigmine and galantamine on the transgenic Drosophila model of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2022, 3, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarotsky, V.; Sramek, J.J.; Cutler, N.R. Galantamine hydrobromide: An agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2003, 60, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.