Multi-Marker Evaluation of Creatinine, Cystatin C and β2-Microglobulin for GFR Estimation in Stage 3–4 CKD Using the 2021 CKD-EPI Equations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

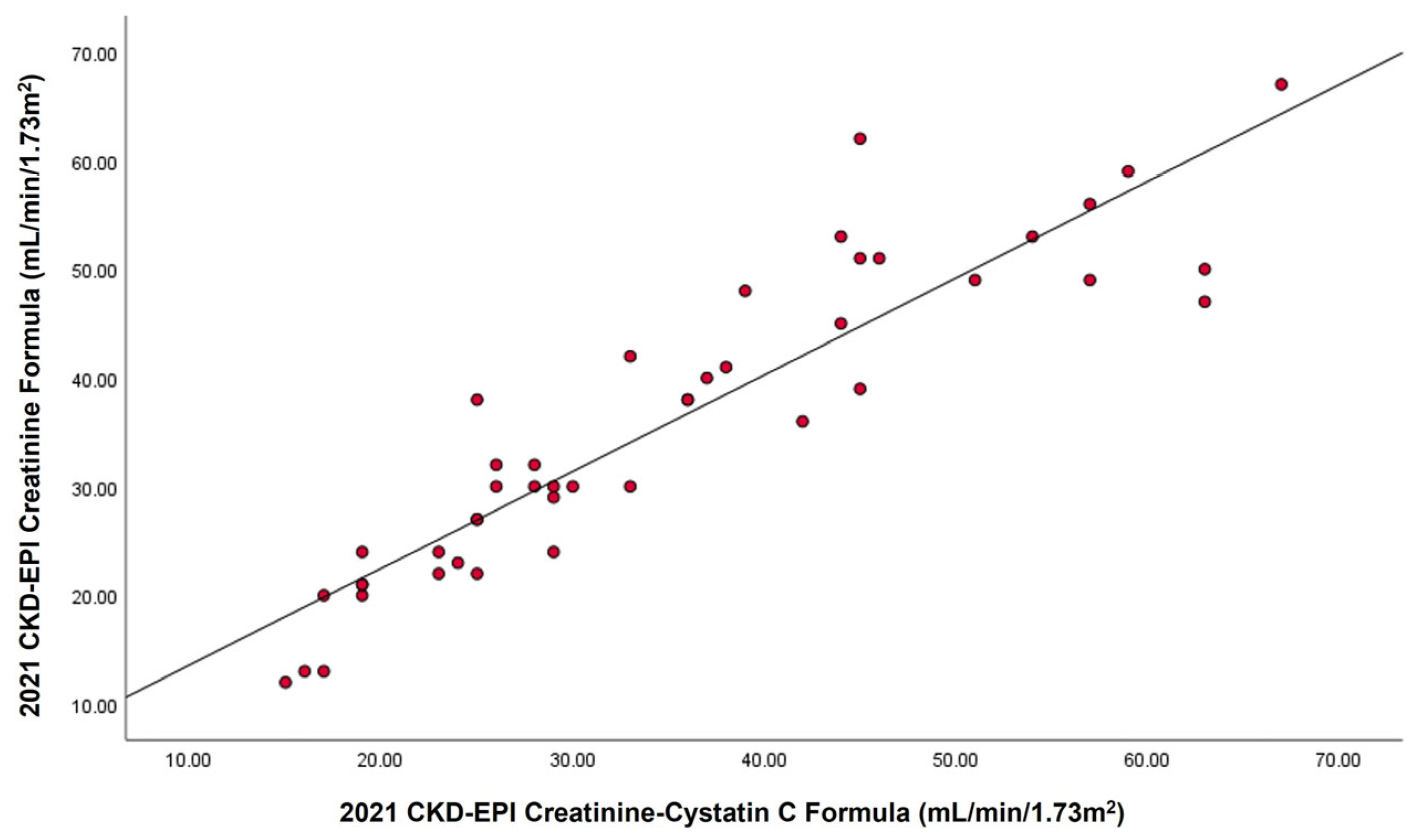

2.1. Relationship Between Serum Cystatin C, Creatinine, and β2M with GFR

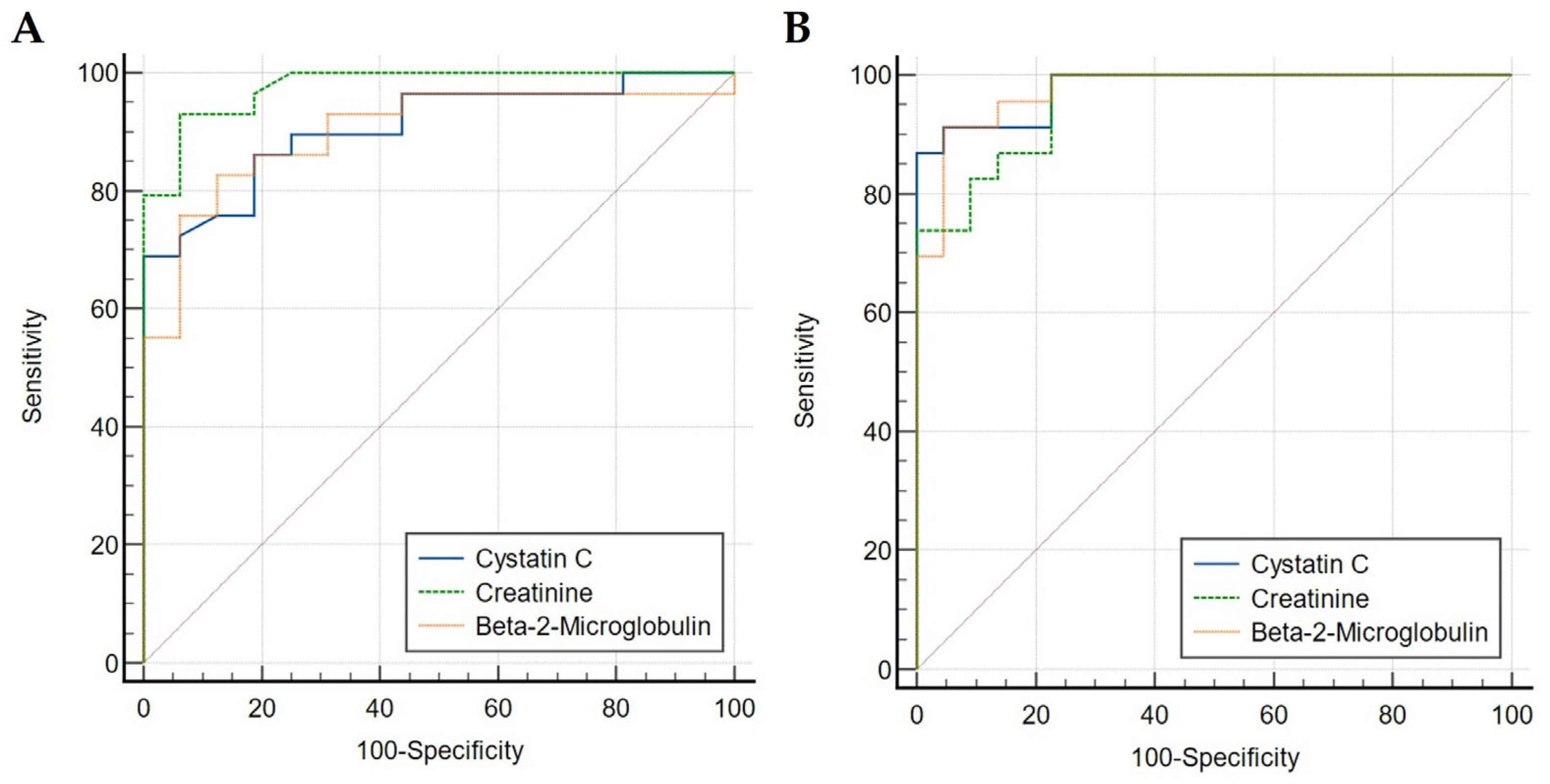

2.2. Diagnostic Accuracy Comparison Between Serum Creatinine, Cystatin C and β2M

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients’ Samples

4.2. Cystatin C, Beta-2 Microglobulin (β2M) and Creatinine Assays

4.3. GFR Estimation

4.3.1. 2021 CKD-EPI Creatinine Formula (eGFRcr)

| Sex | Creatinine Level | A | B |

| Female | ≤0.7 mg/dL | 0.7 | −0.241 |

| Female | >0.7 mg/dL | 0.7 | −1.200 |

| Male | ≤0.9 mg/dL | 0.9 | −0.302 |

| Male | >0.9 mg/dL | 0.9 | −1.200 |

4.3.2. 2021 CKD-EPI Creatinine–Cystatin C Formula (eGFRcr–cys)

| Sex | Creatinine Level | Cystatin C Level | A | B | C | D |

| Female | ≤0.7 mg/dL | ≤0.8 mg/L | 0.7 | −0.219 | 0.8 | −0.323 |

| Female | ≤0.7 mg/dL | >0.8 mg/L | 0.7 | −0.219 | 0.8 | −0.778 |

| Female | >0.7 mg/dL | ≤0.8 mg/L | 0.7 | −0.544 | 0.8 | −0.323 |

| Female | >0.7 mg/dL | >0.8 mg/L | 0.7 | −0.544 | 0.8 | −0.778 |

| Male | ≤0.9 mg/dL | ≤0.8 mg/L | 0.9 | −0.144 | 0.8 | −0.323 |

| Male | ≤0.9 mg/dL | >0.8 mg/L | 0.9 | −0.144 | 0.8 | −0.778 |

| Male | >0.9 mg/dL | ≤0.8 mg/L | 0.9 | −0.544 | 0.8 | −0.323 |

| Male | >0.9 mg/dL | >0.8 mg/L | 0.9 | −0.544 | 0.8 | −0.778 |

4.4. Statistical Methods

4.4.1. Correlation Analysis

4.4.2. Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CI | confidence intervals |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| CKD-EPI | Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| eGFRcr | The 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine equation |

| eGFRcr–cys | The 2021 CKD-EPI creatinine–cystatin C equation |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| KDIGO | The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| KDOQI | The National Kidney Foundation–Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative |

| MDRD | Modification of Diet in Renal Disease |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| p | p-value |

| PENIA | particle-enhanced nephelometric assay |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| r | Pearson correlation coefficients |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| β2M | Beta-2 microglobulin |

Appendix A

| Patient ID | Age | Sex | 1/Cystatin C | 1/Creatinine | 1/β2M | eGFRcr | eGFRcr–cys |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 75 | Male | 0.35461 | 0.00369 | 0.135869565 | 20 | 19 |

| P2 | 51 | Male | 0.757576 | 0.0075758 | 0.395256917 | 56 | 57 |

| P3 | 47 | Female | 0.383142 | 0.0027701 | 0.132802125 | 13 | 17 |

| P4 | 53 | Male | 0.934579 | 0.0068966 | 0.396825397 | 50 | 63 |

| P5 | 56 | Male | 0.389105 | 0.0038023 | 0.18115942 | 24 | 23 |

| P6 | 68 | Male | 0.44843 | 0.0065359 | 0.235849057 | 42 | 33 |

| P7 | 59 | Female | 0.350877 | 0.0027855 | 0.10940919 | 12 | 15 |

| P8 | 40 | Male | 0.332226 | 0.0030864 | 0.149476831 | 21 | 19 |

| P9 | 42 | Female | 0.47619 | 0.0042553 | 0.191204589 | 22 | 25 |

| P10 | 56 | Male | 0.395257 | 0.0045662 | 0.182481752 | 30 | 26 |

| P11 | 50 | Female | 0.460829 | 0.0056497 | 0.199203187 | 30 | 30 |

| P12 | 61 | Male | 0.471698 | 0.0046948 | 0.240963855 | 30 | 29 |

| P13 | 50 | Male | 0.409836 | 0.0034722 | 0.129366106 | 22 | 23 |

| P14 | 70 | Female | 0.332226 | 0.0052632 | 0.104166667 | 24 | 19 |

| P15 | 45 | Male | 0.952381 | 0.0063694 | 0.469483568 | 47 | 63 |

| P16 | 67 | Male | 0.485437 | 0.0047393 | 0.273972603 | 29 | 29 |

| P17 | 45 | Male | 0.502513 | 0.0064103 | 0.244498778 | 48 | 39 |

| P18 | 51 | Female | 0.649351 | 0.008 | 0.334448161 | 45 | 44 |

| P19 | 60 | Male | 0.355872 | 0.0023585 | 0.130718954 | 13 | 16 |

| P20 | 27 | Female | 0.421941 | 0.0045662 | 0.17452007 | 27 | 25 |

| P21 | 54 | Female | 0.561798 | 0.0073529 | 0.280898876 | 40 | 37 |

| P22 | 65 | Female | 0.793651 | 0.009901 | 0.41322314 | 53 | 54 |

| P23 | 25 | Female | 0.340136 | 0.0060241 | 0.082644628 | 38 | 25 |

| P24 | 74 | Female | 0.485437 | 0.0064516 | 0.183823529 | 30 | 28 |

| P25 | 56 | Female | 0.558659 | 0.0071942 | 0.275482094 | 38 | 36 |

| P26 | 59 | Male | 0.60241 | 0.0072993 | 0.3003003 | 51 | 45 |

| P27 | 31 | Female | 0.442478 | 0.0040816 | 0.192307692 | 23 | 24 |

| P28 | 50 | Male | 0.609756 | 0.0068966 | 0.421940928 | 51 | 46 |

| P29 | 32 | Female | 0.552486 | 0.009434 | 0.354609929 | 62 | 45 |

| P30 | 70 | Female | 0.4329 | 0.0057143 | 0.207900208 | 27 | 25 |

| P31 | 27 | Male | 0.740741 | 0.006993 | 0.381679389 | 59 | 59 |

| P32 | 50 | Male | 0.714286 | 0.0066667 | 0.338983051 | 49 | 51 |

| P33 | 38 | Female | 0.869565 | 0.0104167 | 0.487804878 | 67 | 67 |

| P34 | 33 | Female | 0.299401 | 0.0037594 | 0.149700599 | 20 | 17 |

| P35 | 47 | Male | 0.526316 | 0.0053191 | 0.25974026 | 38 | 36 |

| P36 | 50 | Male | 0.571429 | 0.0071429 | 0.256410256 | 53 | 44 |

| P37 | 46 | Female | 0.564972 | 0.0071942 | 0.249376559 | 41 | 38 |

| P38 | 65 | Female | 0.746269 | 0.0076923 | 0.272479564 | 39 | 45 |

| P39 | 57 | Female | 0.581395 | 0.005848 | 0.289017341 | 30 | 33 |

| P40 | 66 | Female | 0.408163 | 0.0064935 | 0.160771704 | 32 | 26 |

| P41 | 66 | Male | 0.847458 | 0.0072464 | 0.46728972 | 49 | 57 |

| P42 | 60 | Male | 0.52356 | 0.0039526 | 0.236966825 | 24 | 29 |

| P43 | 38 | Female | 0.440529 | 0.0056818 | 0.215053763 | 32 | 28 |

| P44 | 58 | Male | 0.671141 | 0.0054054 | 0.318471338 | 36 | 42 |

| P45 | 56 | Female | 0.357143 | 0.0044248 | 0.154083205 | 21 | 19 |

References

- Saminathan, T.A.; Hooi, L.S.; Mohd Yusoff, M.F.; Ong, L.M.; Bavanandan, S.; Rodzlan Hasani, W.S.; Tan, E.Z.Z.; Wong, I.; Rifin, H.M.; Robert, T.G.; et al. Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease and Its Associated Factors in Malaysia; Findings from a Nationwide Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nephrol. 2020, 21, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, A.; Tonelli, M.; Bonventre, J.; Coresh, J.; Donner, J.-A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fox, C.S.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Jardine, M.; et al. Global Kidney Health 2017 and beyond: A Roadmap for Closing Gaps in Care, Research, and Policy. Lancet 2017, 390, 1888–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porrini, E.; Ruggenenti, P.; Luis-Lima, S.; Carrara, F.; Jiménez, A.; de Vries, A.P.J.; Torres, A.; Gaspari, F.; Remuzzi, G. Estimated GFR: Time for a Critical Appraisal. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 177–190, Correction in Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-018-0105-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seegmiller, J.C.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Lieske, J.C. Challenges in Measuring Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Clinical Laboratory Perspective. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018, 25, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Coresh, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Wang, D.; Sang, Y.; Crews, D.C.; Doria, A.; Estrella, M.M.; Froissart, M.; et al. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C–Based Equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, F.J.; Kemperman, F.A.W.; Krediet, R.T. A Comparison between Cystatin C, Plasma Creatinine and the Cockcroft and Gault Formula for the Estimation of Glomerular Filtration Rate. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003, 18, 2024–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Tighiouart, H.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Feldman, H.I.; Greene, T.; Kusek, J.W.; Manzi, J.; Van Lente, F.; Zhang, Y.L.; et al. Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate from Serum Creatinine and Cystatin C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 20–29, Correction in N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 681. Correction in N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2060. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMx120062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Couture, S.J.; Tighiouart, H.; Abraham, A.G.; Beck, G.J.; Feldman, H.I.; Greene, T.; Gudnason, V.; Karger, A.B.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; et al. A New Panel-Estimated GFR, Including Β2-Microglobulin and β-Trace Protein and Not Including Race, Developed in a Diverse Population. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021, 77, 673–683.e1, Correction in Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 83, 840. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2024.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, K.T.; Kakajiwala, A.; Dietzen, D.J.; Goss, C.W.; Gu, H.; Dharnidharka, V.R. Using the Newer Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Criteria, Beta-2-Microglobulin Levels Associate with Severity of Acute Kidney Injury. Clin. Kidney J. 2018, 11, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Tighiouart, H.; Coresh, J.; Foster, M.C.; Anderson, A.H.; Beck, G.J.; Contreras, G.; Greene, T.; Karger, A.B.; Kusek, J.W.; et al. GFR Estimation Using β-Trace Protein and Β2-Microglobulin in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalalonmuhali, M.; Lim, S.K.; Md Shah, M.N.; Ng, K.P. MDRD vs. CKD-EPI in Comparison to 51Chromium EDTA: A Cross Sectional Study of Malaysian CKD Cohort. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlipak, M.G.; Matsushita, K.; Ärnlöv, J.; Inker, L.A.; Katz, R.; Polkinghorne, K.R.; Rothenbacher, D.; Sarnak, M.J.; Astor, B.C.; Coresh, J.; et al. Cystatin C versus Creatinine in Determining Risk Based on Kidney Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shardlow, A.; McIntyre, N.J.; Fraser, S.D.S.; Roderick, P.; Raftery, J.; Fluck, R.J.; McIntyre, C.W.; Taal, M.W. The Clinical Utility and Cost Impact of Cystatin C Measurement in the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease: A Primary Care Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyropoulos, C.P.; Chen, S.S.; Ng, Y.-H.; Roumelioti, M.-E.; Shaffi, K.; Singh, P.P.; Tzamaloukas, A.H. Rediscovering Beta-2 Microglobulin as a Biomarker across the Spectrum of Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Foster, M.C.; Tighiouart, H.; Anderson, A.H.; Beck, G.J.; Contreras, G.; Coresh, J.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Feldman, H.I.; Greene, T.; et al. Non-GFR Determinants of Low-Molecular-Weight Serum Protein Filtration Markers in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 892–900, Correction in Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 83, 840. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2024.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safdar, A.; Akram, W.; Khan, M.A.; Tahir, D.; Butt, M.H. Comparison of EKFC, Pakistani CKD-EPI and 2021 Race-Free CKD-EPI Creatinine Equations in South Asian CKD Population: A Study from Pakistani CKD Community Cohort. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kang, M.; Kang, E.; Ryu, H.; Jeong, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, S.K.; Jeong, J.C.; Yoo, T.-H.; Kim, Y.; et al. Comparison of Cardiovascular Event Predictability between the 2009 and 2021 Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Equations in a Korean Chronic Kidney Disease Cohort: The KoreaN Cohort Study for Outcome in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 42, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, L.; Pan, B.; Shi, X.; Du, X. Comparison between the Beta-2 Microglobulin-Based Equation and the CKD-EPI Equation for Estimating GFR in CKD Patients in China: ES-CKD Study. Kidney Dis. 2020, 6, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betzler, B.K.; Sultana, R.; He, F.; Tham, Y.C.; Lim, C.C.; Wang, Y.X.; Nangia, V.; Tai, E.S.; Rim, T.H.; Bikbov, M.M.; et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) GFR Estimating Equations on CKD Prevalence and Classification Among Asians. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 957437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | |||

| GFR Marker | r | R2 | Linear Equation |

| Serum creatinine | 0.906 | 0.821 | y = (1.48 × 10−3) + (1.21 × 10−4)x |

| Serum cystatin C | 0.775 | 0.601 | y = (0.2 × 10−3) + (9.5 × 10−3)x |

| Serum β2M | 0.836 | 0.699 | y = 0.02 + (6.38 × 10−3)x |

| (B) | |||

| GFR Marker | r | R2 | Linear Equation |

| Serum creatinine | 0.806 | 0.651 | y = (2.15 × 10−3) + (1.05 × 10−4)x |

| Serum cystatin C | 0.960 | 0.922 | y = 0.13 + (0.01)x |

| Serum β2M | 0.944 | 0.892 | y = (7.8 × 10−3) + 7.01 × (10−3)x |

| (A) | |||||

| GFR Marker | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Youden Index |

| Serum creatinine | 93.10 | 93.75 | 94.80 | 91.30 | 0.87 |

| Serum cystatin C | 68.97 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 78.60 | 0.69 |

| Serum β2M | 82.76 | 87.50 | 85.20 | 85.10 | 0.70 |

| (B) | |||||

| GFR Marker | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Youden Index |

| Serum creatinine | 100.00 | 77.27 | 80.60 | 100.00 | 0.77 |

| Serum cystatin C | 86.96 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 84.00 | 0.87 |

| Serum β2M | 91.30 | 95.45 | 95.20 | 91.70 | 0.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abu Bakar, N.; Hamzan, N.I.; Ahmad Ridzuan, S.N.; Taib, I.S.; Abdul Hamid, Z.; Habib, A.; Hassan, N.H. Multi-Marker Evaluation of Creatinine, Cystatin C and β2-Microglobulin for GFR Estimation in Stage 3–4 CKD Using the 2021 CKD-EPI Equations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020862

Abu Bakar N, Hamzan NI, Ahmad Ridzuan SN, Taib IS, Abdul Hamid Z, Habib A, Hassan NH. Multi-Marker Evaluation of Creatinine, Cystatin C and β2-Microglobulin for GFR Estimation in Stage 3–4 CKD Using the 2021 CKD-EPI Equations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020862

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbu Bakar, Nurulamin, Nurul Izzati Hamzan, Siti Nurwani Ahmad Ridzuan, Izatus Shima Taib, Zariyantey Abdul Hamid, Anasufiza Habib, and Noor Hafizah Hassan. 2026. "Multi-Marker Evaluation of Creatinine, Cystatin C and β2-Microglobulin for GFR Estimation in Stage 3–4 CKD Using the 2021 CKD-EPI Equations" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020862

APA StyleAbu Bakar, N., Hamzan, N. I., Ahmad Ridzuan, S. N., Taib, I. S., Abdul Hamid, Z., Habib, A., & Hassan, N. H. (2026). Multi-Marker Evaluation of Creatinine, Cystatin C and β2-Microglobulin for GFR Estimation in Stage 3–4 CKD Using the 2021 CKD-EPI Equations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020862