Dnmt3b Deficiency in Adipocyte Progenitor Cells Ameliorates Obesity in Female Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

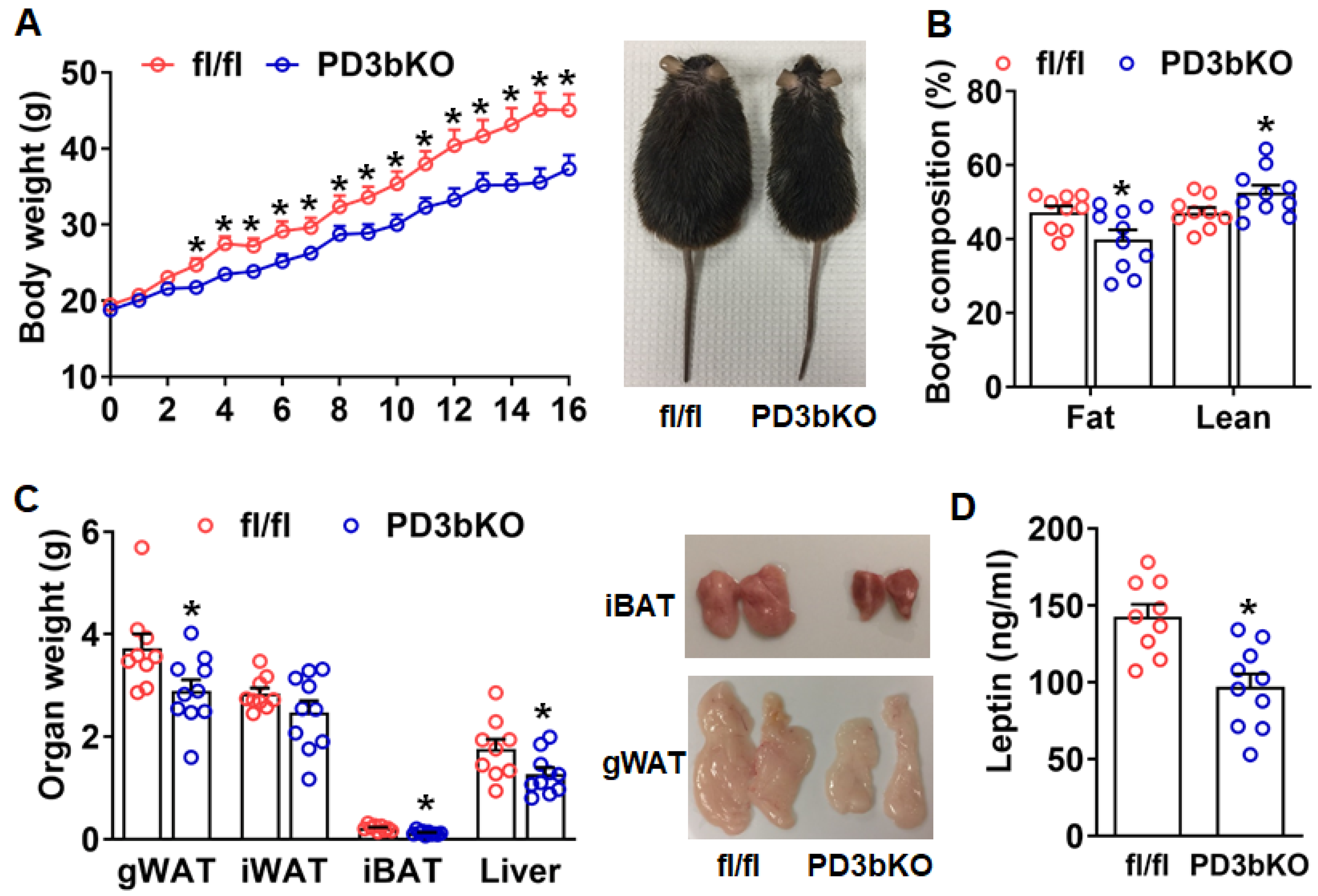

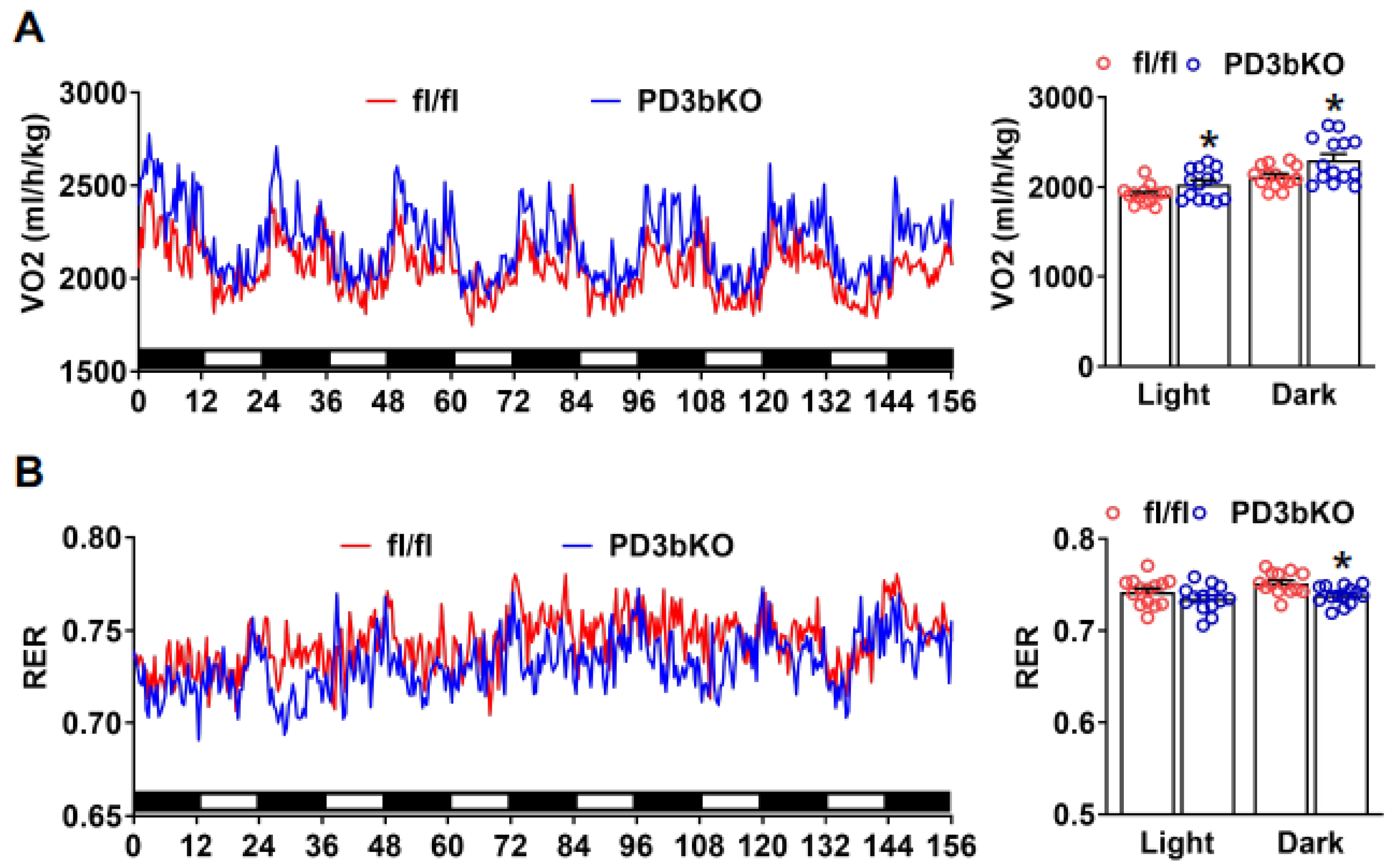

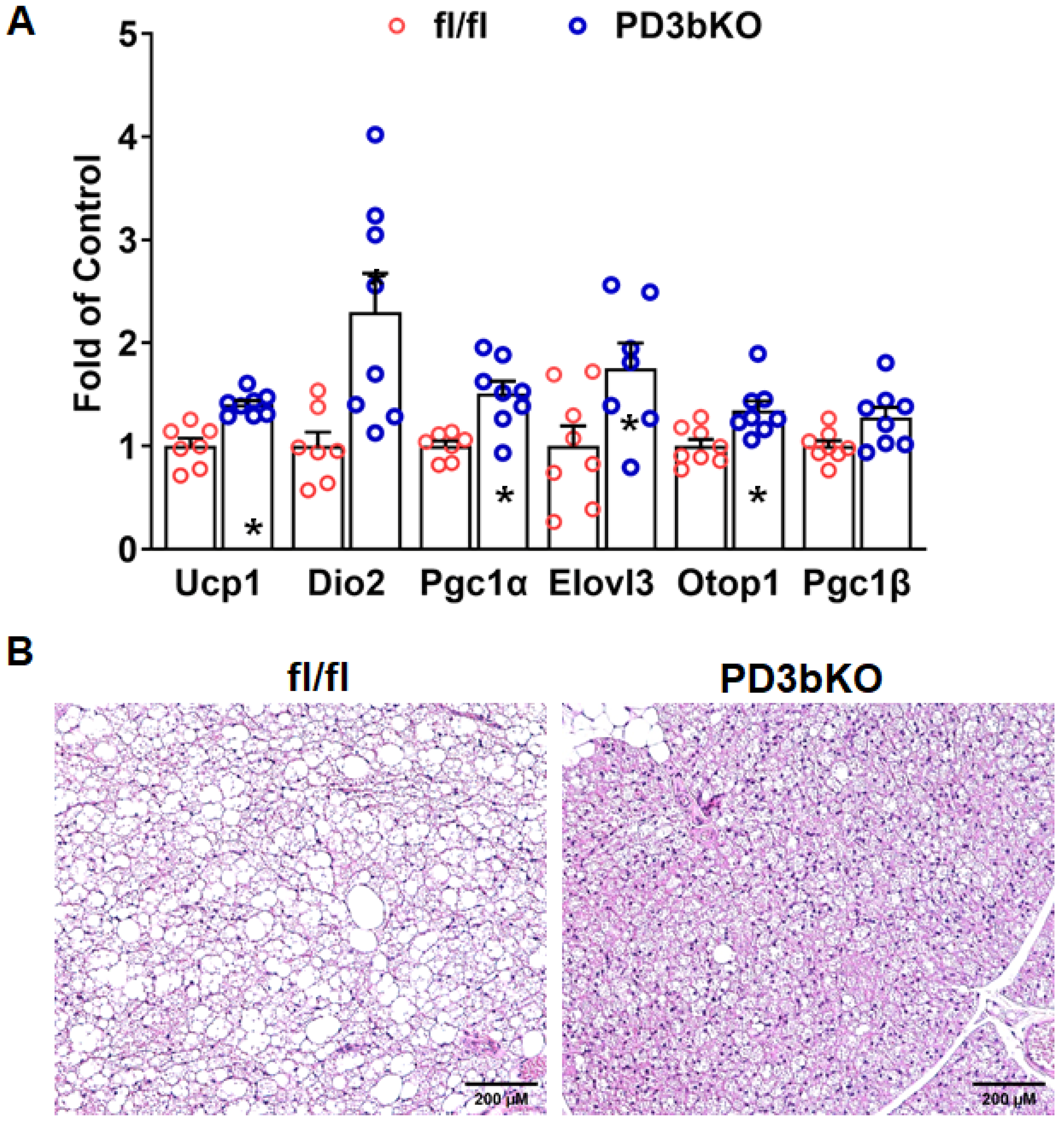

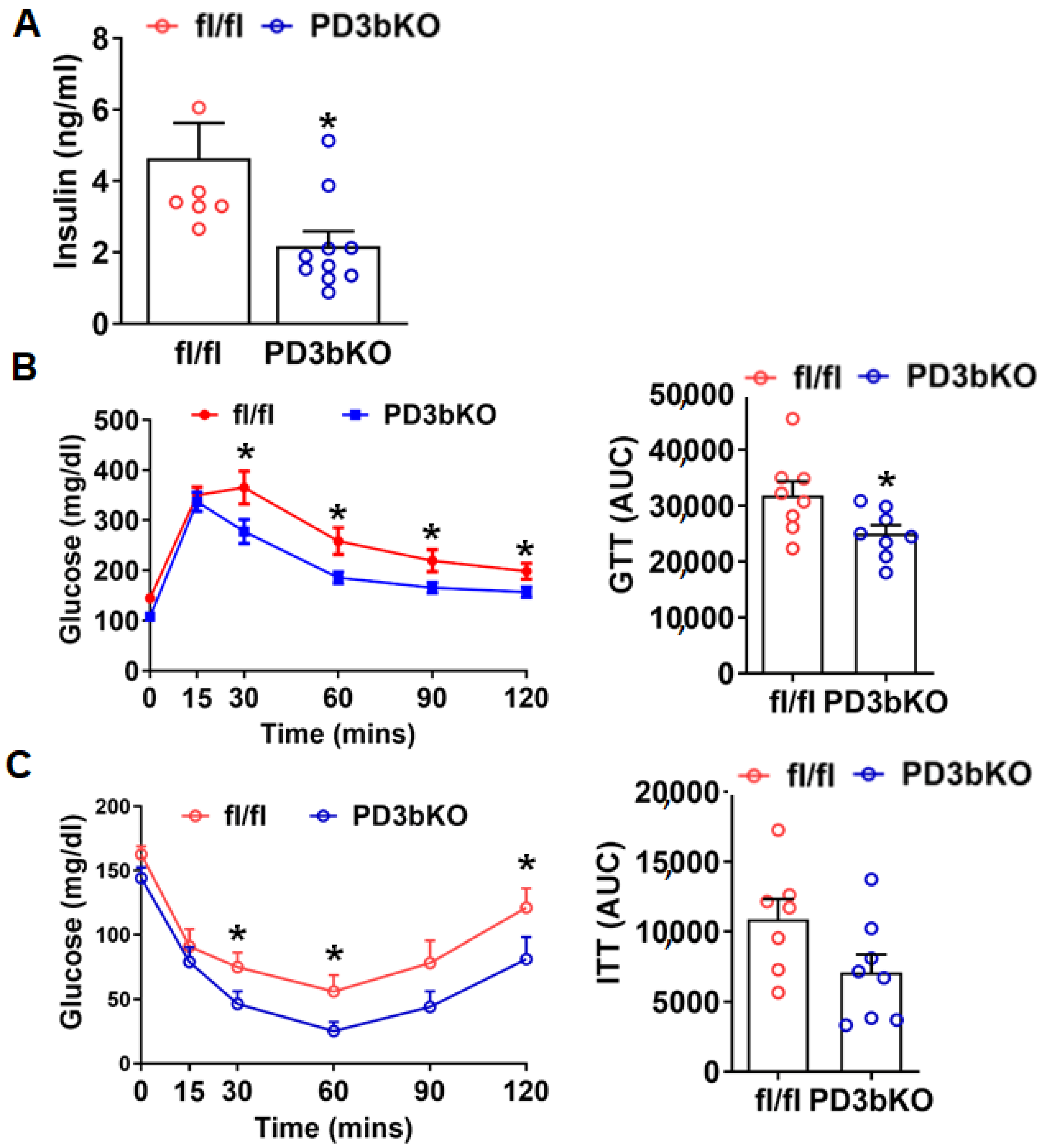

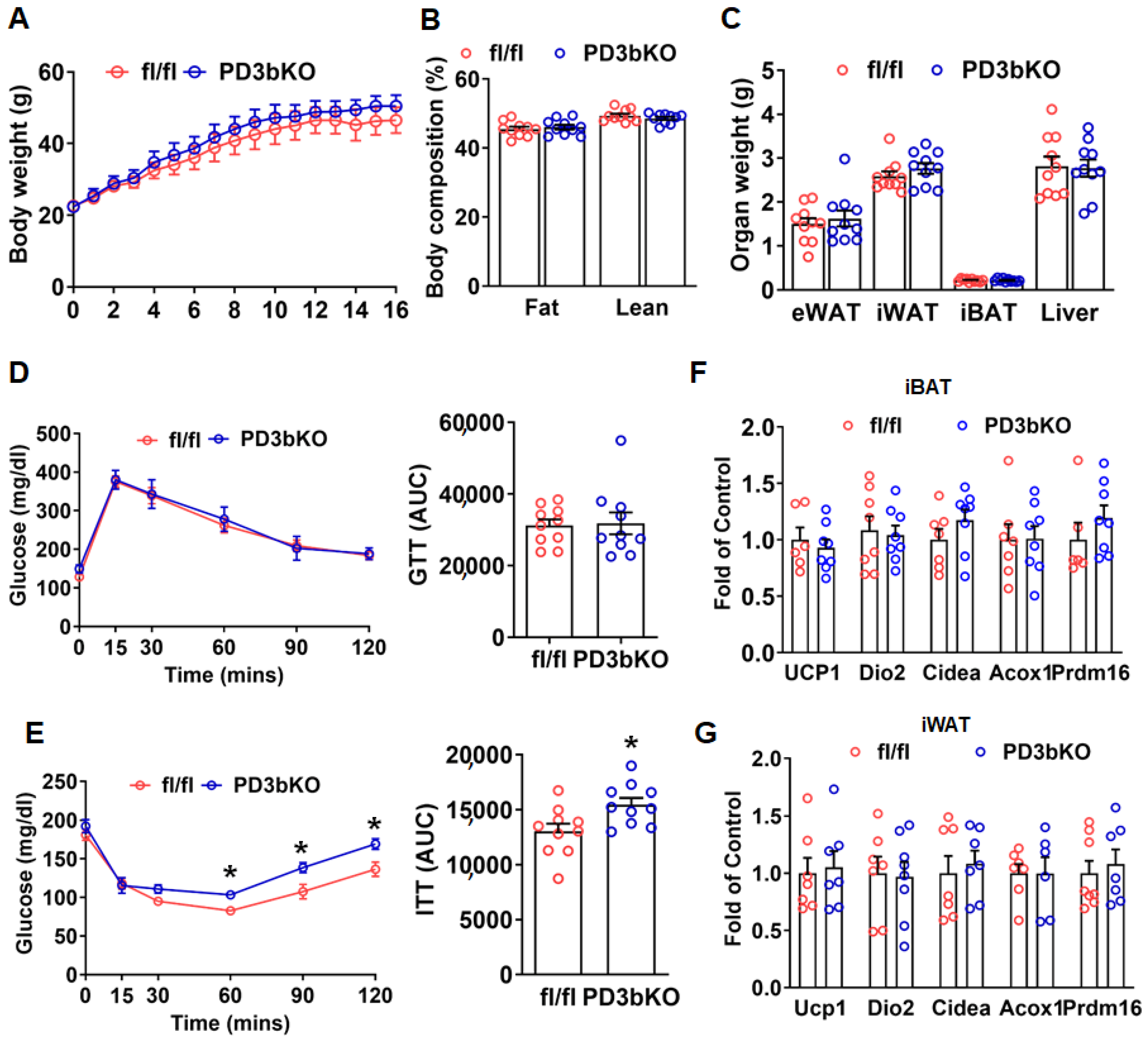

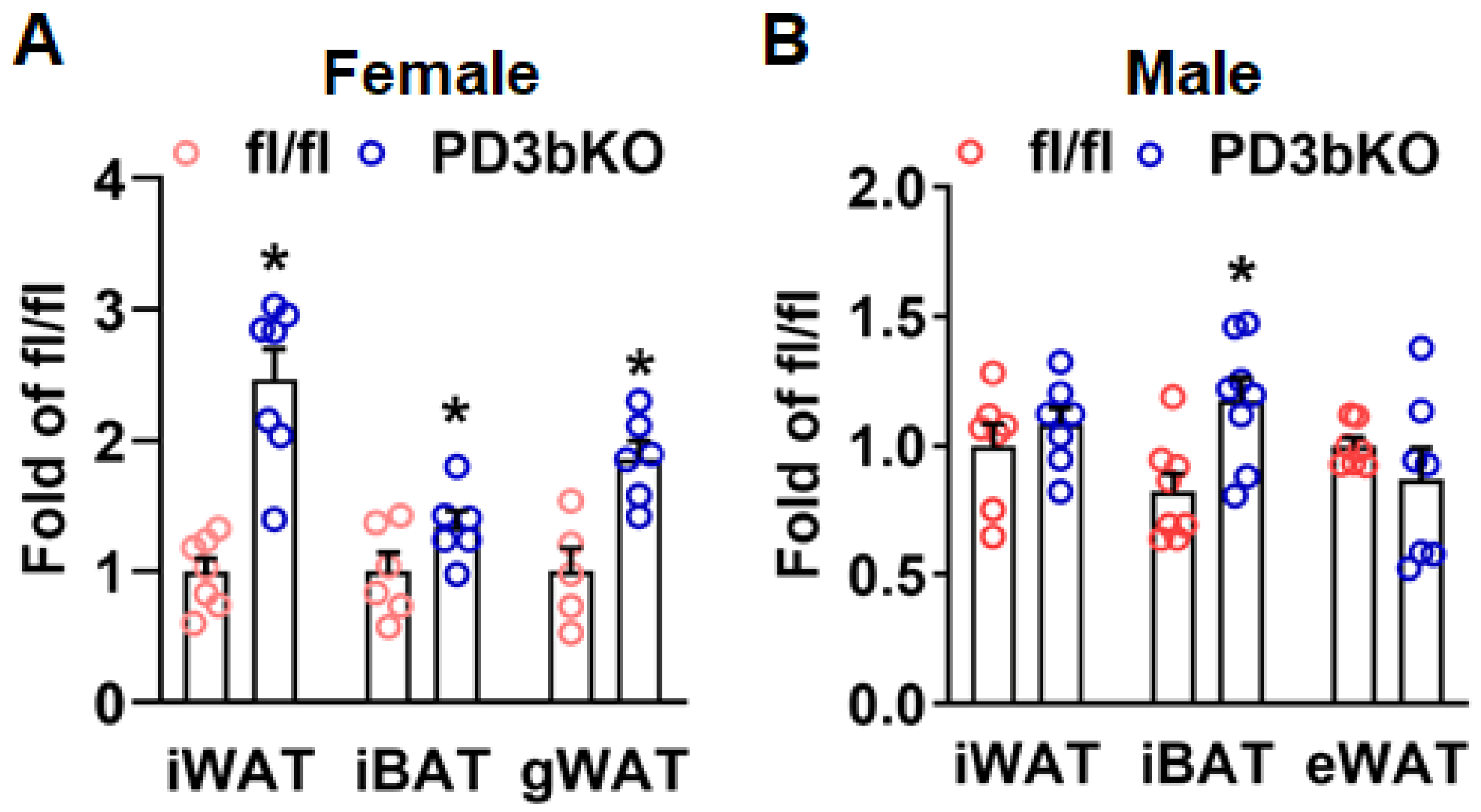

Dnmt3b Deficiency in Adipose Progenitor Cells Ameliorates Diet-Induced Obesity in Female Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mice

4.2. Metabolic Analysis

4.3. Quantitative RT-PCR

4.4. Histology

4.5. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hill, J.O.; Wyatt, H.R.; Peters, J.C. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation 2012, 126, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.D.; Gress, R.E.; Smith, S.C.; Halverson, R.C.; Simper, S.C.; Rosamond, W.D.; Lamonte, M.J.; Stroup, A.M.; Hunt, S.C. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J. The biochemistry of an inefficient tissue: Brown adipose tissue. Essays Biochem. 1985, 20, 110–164. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, D.G.; Locke, R.M. Thermogenic mechanisms in brown fat. Physiol. Rev. 1984, 64, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, L.; Chouchani, E.T.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Erickson, B.K.; Shinoda, K.; Cohen, P.; Vetrivelan, R.; Lu, G.Z.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Hasenfuss, S.C.; et al. A creatine-driven substrate cycle enhances energy expenditure and thermogenesis in beige fat. Cell 2015, 163, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K.; Kang, Q.; Yoneshiro, T.; Camporez, J.P.; Maki, H.; Homma, M.; Shinoda, K.; Chen, Y.; Lu, X.; Maretich, P.; et al. UCP1-independent signaling involving SERCA2b-mediated calcium cycling regulates beige fat thermogenesis and systemic glucose homeostasis. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, K.; Maretich, P.; Kajimura, S. The Common and Distinct Features of Brown and Beige Adipocytes. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.M.; Myers, J.P. Environmental exposures and gene regulation in disease etiology. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, M.K.; Manikkam, M.; Guerrero-Bosagna, C. Epigenetic transgenerational actions of environmental factors in disease etiology. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczak, M.W.; Jagodzinski, P.P. The role of DNA methylation in cancer development. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2006, 44, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M.M.; Bird, A. DNA methylation landscapes: Provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunakea, A.K.; Chepelev, I.; Zhao, K. Epigenome mapping in normal and disease States. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeltsch, A.; Jurkowska, R.Z. New concepts in DNA methylation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, R.; Shan, W.; Yu, L.; Xue, B.; Shi, H. DNA Methylation Biphasically Regulates 3T3-L1 Preadipocyte Differentiation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2016, 30, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jing, J.; Movahed, M.; Cui, X.; Cao, Q.; Wu, R.; Chen, Z.; Yu, L.; Pan, Y.; Shi, H.; et al. Epigenetic interaction between UTX and DNMT1 regulates diet-induced myogenic remodeling in brown fat. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Sakashita, H.; Kim, J.; Tang, Z.; Upchurch, G.M.; Yao, L.; Berry, W.L.; Griffin, T.M.; Olson, L.E. Mosaic Mutant Analysis Identifies PDGFRalpha/PDGFRbeta as Negative Regulators of Adipogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 707–721.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, R.; Rodeheffer, M.S. Characterization of the adipocyte cellular lineage in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Daquinag, A.C.; Su, F.; Snyder, B.; Kolonin, M.G. PDGFRalpha/PDGFRbeta signaling balance modulates progenitor cell differentiation into white and beige adipocytes. Development 2018, 145, dev155861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, K.C.; Costa, M.J.; Du, H.; Feldman, B.J. Characterization of Cre recombinase activity for in vivo targeting of adipocyte precursor cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 3, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwayama, T.; Steele, C.; Yao, L.; Dozmorov, M.G.; Karamichos, D.; Wren, J.D.; Olson, L.E. PDGFRalpha signaling drives adipose tissue fibrosis by targeting progenitor cell plasticity. Genes. Dev. 2015, 29, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Jing, J.; Cui, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Carrillo, J.A.; Ding, Z.; Song, J.; et al. Epigenetic programming of estrogen receptor in adipocytes by high-fat diet regulates obesity-induced inflammation. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e173423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campion, J.; Milagro, F.I.; Martinez, J.A. Individuality and epigenetics in obesity. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holness, M.J.; Sugden, M.C. Epigenetic regulation of metabolism in children born small for gestational age. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2006, 9, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Groop, L. Epigenetics: A molecular link between environmental factors and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2718–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.; Olek, A. Diabetes: A candidate disease for efficient DNA methylation profiling. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2440S–2443S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Szarc vel Szic, K.; Ndlovu, M.N.; Haegeman, G.; Vanden Berghe, W. Nature or nurture: Let food be your epigenetic medicine in chronic inflammatory disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 1816–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, A.; Karamitri, A.; Kemp, P.; Speakman, J.R.; Lomax, M.A. Role of Ucp1 enhancer methylation and chromatin remodelling in the control of Ucp1 expression in murine adipose tissue. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barres, R.; Yan, J.; Egan, B.; Treebak, J.T.; Rasmussen, M.; Fritz, T.; Caidahl, K.; Krook, A.; O’Gorman, D.J.; Zierath, J.R. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barres, R.; Osler, M.E.; Yan, J.; Rune, A.; Fritz, T.; Caidahl, K.; Krook, A.; Zierath, J.R. Non-CpG methylation of the PGC-1alpha promoter through DNMT3B controls mitochondrial density. Cell Metab. 2009, 10, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noer, A.; Boquest, A.C.; Collas, P. Dynamics of adipogenic promoter DNA methylation during clonal culture of human adipose stem cells to senescence. BMC Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milagro, F.I.; Campion, J.; Garcia-Diaz, D.F.; Goyenechea, E.; Paternain, L.; Martinez, J.A. High fat diet-induced obesity modifies the methylation pattern of leptin promoter in rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Q.; Yu, L.; Shi, H.; Xue, B.; Shi, H. Epigenetic regulation of macrophage polarization and inflammation by DNA methylation in obesity. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e87748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algire, C.; Medrikova, D.; Herzig, S. White and brown adipose stem cells: From signaling to clinical implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1831, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Cui, X.; Jing, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, H.; Xue, B.; Shi, H. Brown Fat Dnmt3b Deficiency Ameliorates Obesity in Female Mice. Life 2021, 11, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, D.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Heo, M.; Jebb, S.A.; Murgatroyd, P.R.; Sakamoto, Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: An approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, B.F.; Clegg, D.J. The sexual dimorphism of obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 402, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.L.; Bessesen, D.H.; Stotz, S.; Peelor, F.F., 3rd; Miller, B.F.; Horton, T.J. Adrenergic control of lipolysis in women compared with men. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 117, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.; Teixeira, D.; Calhau, C. Estrogen signaling in metabolic inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 615917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, J.E.; Okano, M.; Dick, F.; Tsujimoto, N.; Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Ueda, Y.; Dyson, N.; Li, E. Inactivation of Dnmt3b in mouse embryonic fibroblasts results in DNA hypomethylation, chromosomal instability, and spontaneous immortalization. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 17986–17991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.; Yu, S.; Cao, Q.; Tang, W.; Jing, J.; Xue, B.; Shi, H. Dnmt3b Deficiency in Adipocyte Progenitor Cells Ameliorates Obesity in Female Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020861

Huang Y, Yu S, Cao Q, Tang W, Jing J, Xue B, Shi H. Dnmt3b Deficiency in Adipocyte Progenitor Cells Ameliorates Obesity in Female Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020861

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yifei, Sean Yu, Qiang Cao, Weiqing Tang, Jia Jing, Bingzhong Xue, and Hang Shi. 2026. "Dnmt3b Deficiency in Adipocyte Progenitor Cells Ameliorates Obesity in Female Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020861

APA StyleHuang, Y., Yu, S., Cao, Q., Tang, W., Jing, J., Xue, B., & Shi, H. (2026). Dnmt3b Deficiency in Adipocyte Progenitor Cells Ameliorates Obesity in Female Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27020861