Abstract

Palmitic acid (PA) is the most common dietary saturated fatty acid, and is abundant in palm and cottonseed oil, butter, and cheese, whereas oleic acid (OA) is a monounsaturated omega-9 fatty acid found in olive oil. The differences in the cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of PA and OA across endothelial cells (ECs) isolated from different vascular beds have not been investigated in detail. Here, we incubated primary human aortic valve (HAVEC), saphenous vein (HSaVEC), internal thoracic artery (HITAEC), and microvascular (HMVEC) ECs with albumin-bound PA or OA for 24 h and found that PA induced a considerable cytotoxic response, accompanied by an elevated expression of the genes encoding cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CSF2, CSF3, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), followed by an increased release of interleukin-6 and interleukin-8. HAVEC and HSaVEC were more susceptible to PA, whereas OA had mild-to-moderate cytotoxic effects on HAVEC and HMVEC but did not induce generalized EC activation. Compared with other EC types, HITAEC was the most resistant to PA and OA treatment. Collectively, these results indicate considerable heterogeneity across the ECs of distinct origin in response to PA.

1. Introduction

Fatty acids are critical components of the human diet, serving as essential sources of energy and being indispensable components of cell membranes and adipose tissue [1,2]. Among the numerous fatty acids, palmitic acid (PA) and oleic acid (OA) are highly prevalent in the human diet and are notable for different chemical structures, dietary sources, and health implications [1,2]. PA is the most common saturated fatty acid in the human body, abundantly found in animal and plant sources (especially in palm oil, butter, cheese, and lard), whereas OA is the most common monounsaturated fatty acid in the human diet, and is particularly plentiful in olive oil, avocados, nuts, and seeds [1,2,3,4]. An increased consumption of PA adversely affects vascular health, correlating with elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [4,5,6], insulin resistance [7,8,9,10,11,12], and pro-inflammatory states [11,12,13,14,15]. A lipid-rich Western-style diet, which is characterized by a high intake of processed foods, red meat, and dairy products with a significant amount of PA, has been linked to the augmenting rates of arterial hypertension and atherosclerotic vascular disease in the high-income and upper–middle-income countries [16,17,18,19,20,21]. On the contrary, dietary replacement of saturated fats with OA-rich oils, which exert anti-inflammatory action [22,23,24,25,26], is associated with reduced low-to-high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio [27,28,29,30], better insulin sensitivity [31,32], and lower blood pressure [33,34,35]. Likewise, the Mediterranean-style diet, rich in OA due to the high contents of olive oil, is well known for its beneficial metabolic [36,37,38] and cardioprotective effects [36,37,38,39,40] and decreased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events [41,42,43,44,45]. Therefore, balancing the consumption of PA and OA is of crucial importance for successfully managing cardiovascular risk, particularly in genetically predisposed individuals [46,47,48,49,50].

The integrity and quiescent state of the endothelial monolayer have a pivotal significance for maintaining vascular homeostasis, since the endothelium provides multiple physiological cues to vascular smooth muscle cells located in the tunica media, as well as to adventitial fibroblasts and macrophages in the tunica adventitia and to perivascular adipose cells through the vasa vasorum network [51,52,53,54,55,56]. Endothelial dysfunction [57,58,59,60], triggered by metabolic disorders such as dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, or uremia [61,62], contributes to a chronic low-grade inflammation [63,64], thus mediating the development of the inflammaging [65,66,67,68] and frailty syndrome [69,70]. Another consequence of pro-inflammatory endothelial dysfunction is pathological endothelial permeability, which promotes the retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in the tunica intima and the migration of monocytes which further transform into foam cells upon engulfing the lipid droplets [59,71,72,73]. Among the features of pro-inflammatory endothelial activation are the excessive secretion of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1/C-C motif ligand 2 (MCP-1/CCL2), regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES/CCL5), and macrophage inflammatory protein 3 alpha (MIP-3α/CCL20), and combined overexpression of the genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines, cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) [74,75,76,77,78]. The immediate upregulation of the latter transcripts reflects non-specific endothelial stress rather than the ongoing loss of endothelial markers and the acquisition of mesenchymal markers [75,76,77,78]. Pro-inflammatory stimuli also initiate the apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis of the most vulnerable endothelial cells (ECs), although laminar flow in the blood vessels generally ameliorates these sequelae [79,80,81,82,83]. Nevertheless, soluble EC markers are considered as sensitive and relatively specific markers of pro-inflammatory endothelial activation, which is typically observed in patients with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 [84,85,86,87,88], septic shock [89,90,91,92,93], and frailty syndrome [94,95]. The delineation of the widespread risk factors of endothelial dysfunction and the implementation of the corresponding lifestyle, dietary, or pharmacological interventions might improve vascular health in the population, leading to the better cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous reports indicated the detrimental effects of PA, as well as the neutral or protective role of OA, on EC function. Exposure to PA promotes reactive oxygen species production and oxidative stress [96,97,98,99,100,101], activates NLRP3 inflammasome [96,102], enhances the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-18) and cell adhesion molecules (ICAM-1) [96,102,103], accelerates lipid accumulation [102], reduces nitric oxide (NO) production [101,103], and impairs endothelial barrier integrity [103], ultimately leading to the pyroptosis [96,102] and apoptosis [100,101] of the ECs. However, most of the existing studies have been restricted to a single EC type and have not assessed the effects of PA on ECs from distinct vascular beds. To delineate common and EC type-specific effects of PA-induced endothelial dysfunction, here we prepared the conjugates of PA and OA with a fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (PA-BSA and OA-BSA, respectively), and compared the cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects of PA-BSA and OA-BSA on primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC), human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and human adipose tissue-derived microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) under identical cell culture conditions. We found that PA-BSA exerted significant cytotoxicity and caused pro-inflammatory activation in all the indicated EC types, primarily HAVEC and HSaVEC, whereas OA-BSA had mild-to-moderate cytotoxic effects on HAVEC and HMVEC but did not induce generalized EC activation. Across the four EC types studied, HITAEC was the most resistant to PA-BSA exposure and was also not affected by OA-BSA. Taken together, these results indicate considerable heterogeneity across the ECs of distinct origin in response to PA-BSA.

2. Results

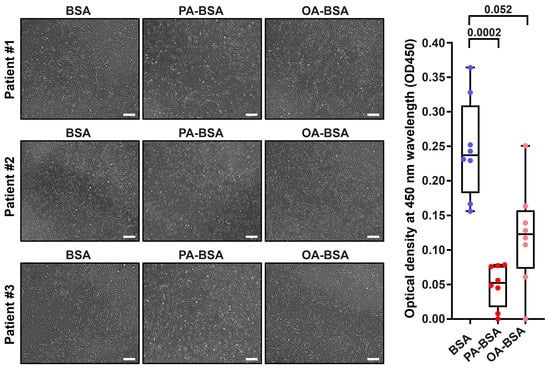

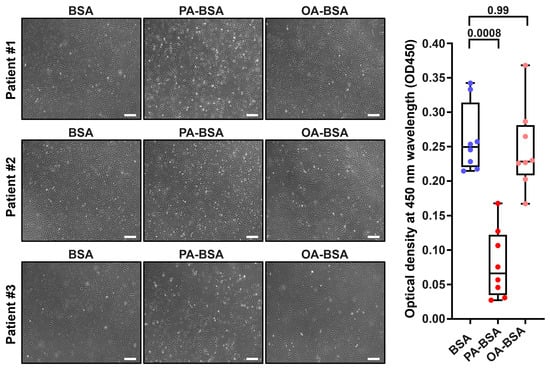

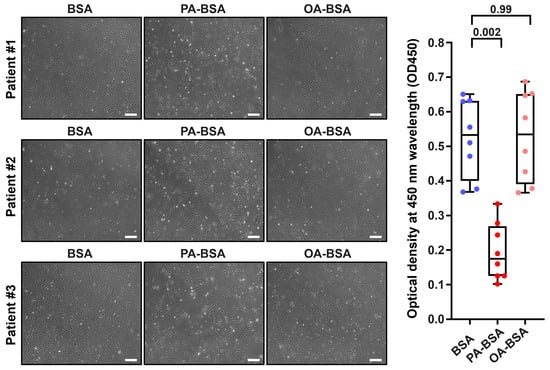

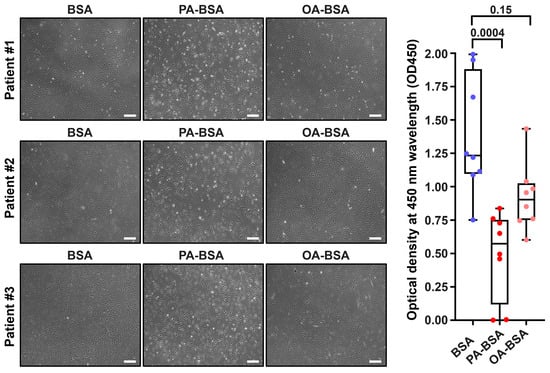

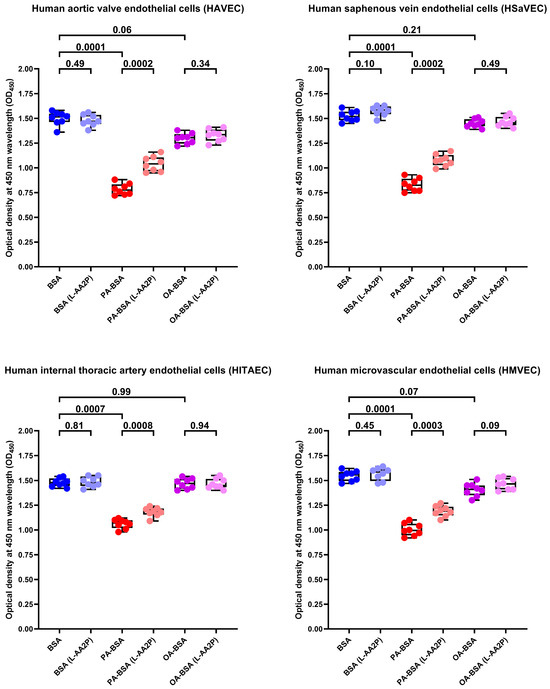

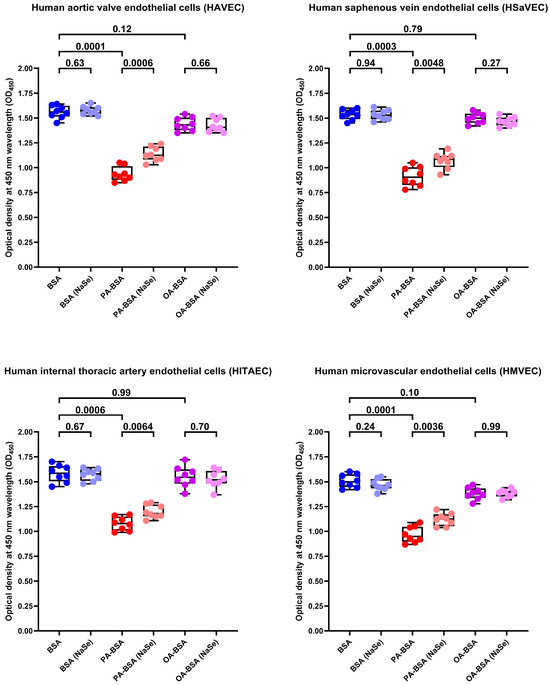

We first asked whether the treatment with control fatty acid-free BSA, PA-BSA (0.8 mmol/L), or OA-BSA (0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h induces cytotoxic effects in HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, or HMVEC. BSA was selected as a carrier protein for PA and OA to ensure their internalization by the ECs. The cytotoxicity of PA-BSA and OA-BSA was assessed by cell visualization and a microplate colorimetric assay evaluating the reduction in a water-soluble tetrazolium salt (WST-8) by the intracellular dehydrogenases into a water-soluble orange–yellow formazan compound with a maximum absorption at a 450 nm wavelength. Upon phase contrast microscopy, cytotoxic effects were defined as loss of the typical cobblestone morphology, EC detachment and rounding, and the presence of floating and fragmented cells, collectively indicating the disruption of endothelial monolayer integrity if supported by the reduction in cell proliferation and viability at the WST-8 assay.

Treatment with PA-BSA induced the demise and detachment of HAVEC (Figure 1), HSaVEC (Figure 2), HITAEC (Figure 3), and HMVEC (Figure 4), ultimately leading to the loss of the cobblestone appearance and impairment of the EC monolayer, whilst ECs incubated with OA-BSA resembled the control ECs at visual inspection (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). The colorimetric WST-8 assay revealed that PA-BSA exhibited pronounced cytotoxicity in all EC types, resulting in a significant reduction in cell viability (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). The most pronounced decrease in metabolic activity was observed in HAVEC (Figure 1) and HSaVEC (Figure 2), which appeared to be the most sensitive to PA-BSA treatment. The effects of OA-BSA were more variable and cell type-dependent, with HAVEC (Figure 1) and HMVEC (Figure 4) showing a mild-to-moderate decline in viability, whereas HSaVEC (Figure 2) and HITAEC (Figure 3) remained unaffected. These findings highlight the heterogeneity of the responses between distinct EC types, suggesting that the extent of fatty acid-induced cytotoxicity is largely determined by the EC origin.

Figure 1.

Cytotoxic effects of conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) on primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC) after the 24 h incubation. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a control group. (Left): Phase contrast microscopy, representative images. Magnification: ×200. Scale bar: 100 µm. (Right): Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay). Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate) for each patient (n = 12 patients, n = 3 per each of the indicated EC types). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above the boxes, via a Kruskal–Wallis test with a subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 2.

Cytotoxic effects of conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) on primary human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC) after the 24 h incubation. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a control group. (Left): Phase contrast microscopy; representative images. Magnification: ×200. Scale bar: 100 µm. (Right): Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay). Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate) for each patient (n = 12 patients, n = 3 per each of the indicated EC types). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above the boxes, via a Kruskal–Wallis test with a subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 3.

Cytotoxic effects of conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) on primary human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC) after the 24 h incubation. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a control group. (Left): Phase contrast microscopy; representative images. Magnification: ×200. Scale bar: 100 µm. (Right): Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay). Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate) for each patient (n = 12 patients, n = 3 per each of the indicated EC types). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above boxes, via Kruskal–Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxic effects of conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) on primary human adipose tissue-derived microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) after the 24 h incubation. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a control group. (Left): Phase contrast microscopy; representative images. Magnification: ×200. Scale bar: 100 µm. (Right): Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay). Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate) for each patient (n = 12 patients, n = 3 per each of the indicated EC types). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above the boxes, via the Kruskal–Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

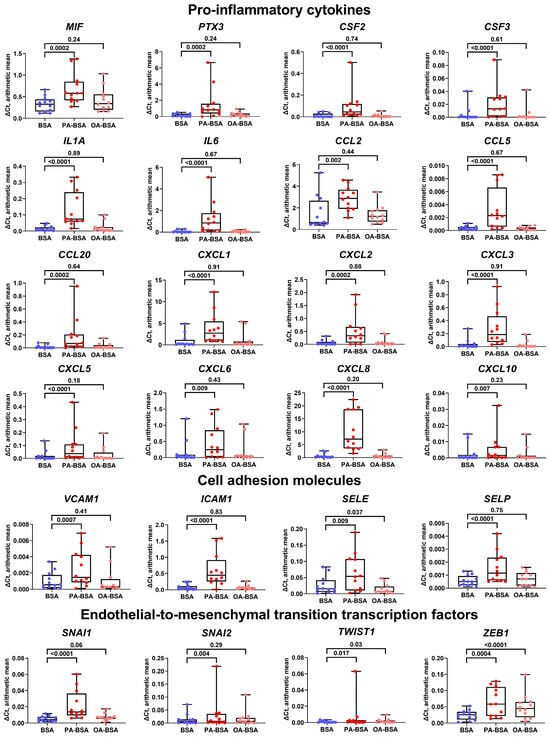

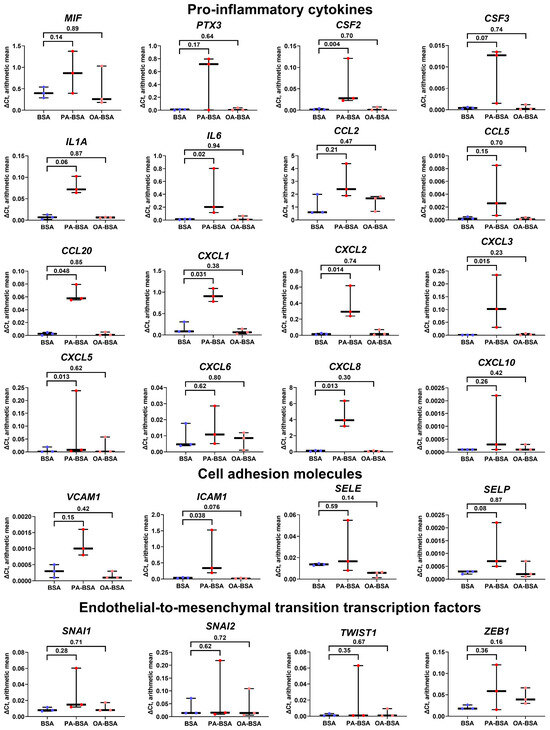

We next aimed to explore the molecular consequences of PA-BSA and OA-BSA treatment of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC. Reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) profiling revealed a ≥2.5-fold increase in the expression of all genes encoding cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), whereas OA-BSA did not cause such effects (Figure 5). Across these pro-inflammatory receptors, the ICAM1 gene was the most upregulated (≈7.5-fold), whereas the VCAM1, SELE, and SELP genes exhibited lower (≈2.5-fold) overexpressions (Figure 5). The expression of all 16 genes encoding core endothelial pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CSF2, CSF3, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10) was significantly (≥2-fold) increased in PA-BSA-treated ECs, whilst none of them were upregulated in ECs incubated with OA-BSA (Figure 5). Among the indicated genes, the highest overexpression was detected for the IL6 (≈18-fold), CXCL8 (≈16-fold), CCL20 (≈11-fold), CXCL2 (≈9-fold), PTX3 (≈9-fold), IL1A (≈9-fold), CCL5 (≈9-fold), and CSF2 (≈8-fold) genes (Figure 5). The lowest overexpression was shown by CCL2 gene (1.9-fold, Figure 5). The expression of the genes encoding EndoMT transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1), which are generally upregulated at endothelial dysfunction, also showed ≥2-fold increase after PA-BSA treatment, in particular the TWIST1 (≈eight-fold increase) and SNAI1 genes (≈four-fold increase, Figure 5). The TWIST1 and ZEB1 genes also demonstrated a ≥two-fold increase following the incubation of ECs with OA-BSA (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Relative levels of gene expression (arithmetic mean) in genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), pro-inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) in primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC), primary human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), primary human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and primary human adipose tissue-derived microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range; p-values are provided above the boxes, via a ratio paired t-test (i.e., ratios of paired values but not absolute differences between paired values were compared).

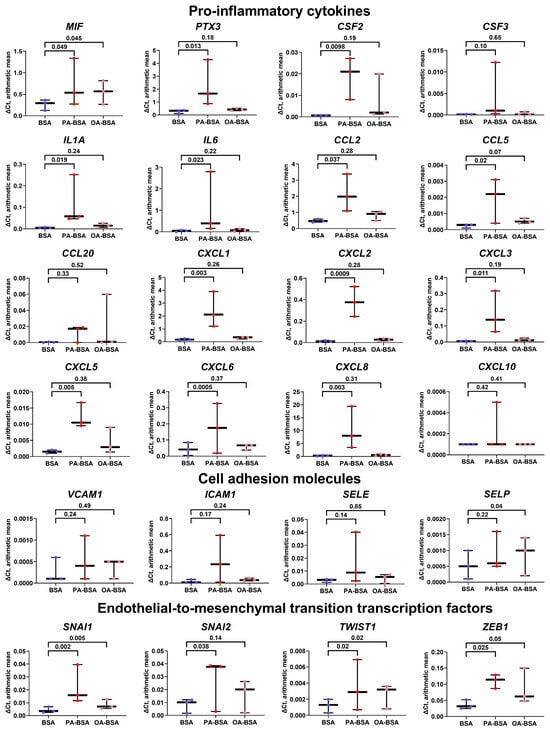

We then evaluated the heterogeneity of endothelial transcriptional response to PA-BSA and OA-BSA. The treatment of HAVEC with PA-BSA led to the significant increase in the expression of genes encoding 13 pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, and CXCL8), whilst only MIF gene expression was elevated upon the incubation with OA-BSA (Figure 6). The expression of the genes encoding cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP) did not show statistically significant alterations, though the VCAM1, ICAM1, and SELE genes were overexpressed in HAVEC after PA-BSA treatment (Figure 6). The treatment of HAVEC with either PA-BSA or OA-BSA induced the expression of the genes encoding EndoMT transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1, Figure 6), indicating the development of endothelial stress in keeping with the reduced viability of HAVEC in the WST-8 assay (Figure 1).

Figure 6.

Relative levels of gene expression (arithmetic mean) in genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), pro-inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) in primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range; p-values are provided above the boxes, via a ratio paired t-test (i.e., ratios of paired values but not absolute differences between paired values were compared).

Similarly to HAVEC the treatment of HSaVEC with PA-BSA elevated the expression of 13 genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, and CXCL8), whereas OA-BSA stimulated the expression of only four genes in this category (PTX3, CCL20, CXCL3, and CXCL10, Figure 7). The expression of the genes encoding cell adhesion molecules in HSaVEC also tended to increase upon PA-BSA exposure, albeit only ICAM1 and SELP genes were significantly overexpressed (Figure 7). Notably, PA-BSA induced the expression of the genes encoding EndoMT transcription factors (SNAI1 and ZEB1, Figure 7). The treatment of HSaVEC with OA-BSA did not reveal a consistent increase in the expression of genes within these categories (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Relative levels of gene expression (arithmetic mean) in genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), pro-inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) in primary human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range; p-values are provided above the boxes, via a ratio paired t-test (i.e., ratios of paired values but not absolute differences between paired values were compared).

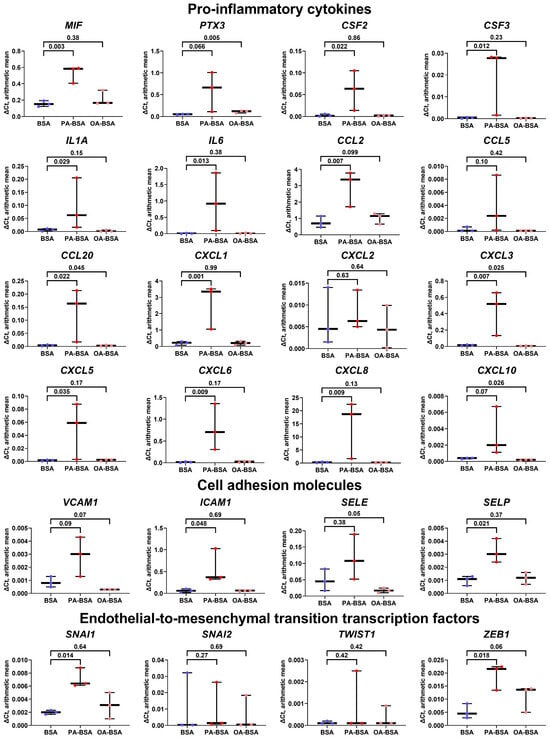

In concert with the results of the WST-8 assay, the incubation of HITAEC with PA-BSA led to a lower endothelial response as compared with HAVEC and HSaVEC, resulting in the significant increase in only one gene (CCL5), although the expression of eleven cytokine genes (PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCL8) also tended to be augmented (Figure 8). OA-BSA did not cause such alterations in the cytokine gene expression in HITAEC (Figure 8). Along similar lines, the expression of the genes encoding cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP) and EndoMT transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) in HITAEC showed a notable but statistically insignificant increase upon PA-BSA but not upon OA-BSA treatment (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Relative levels of gene expression (arithmetic mean) in genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), pro-inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) in primary human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range; p-values are provided above boxes, via a ratio paired t-test (i.e., ratios of paired values but not absolute differences between paired values were compared).

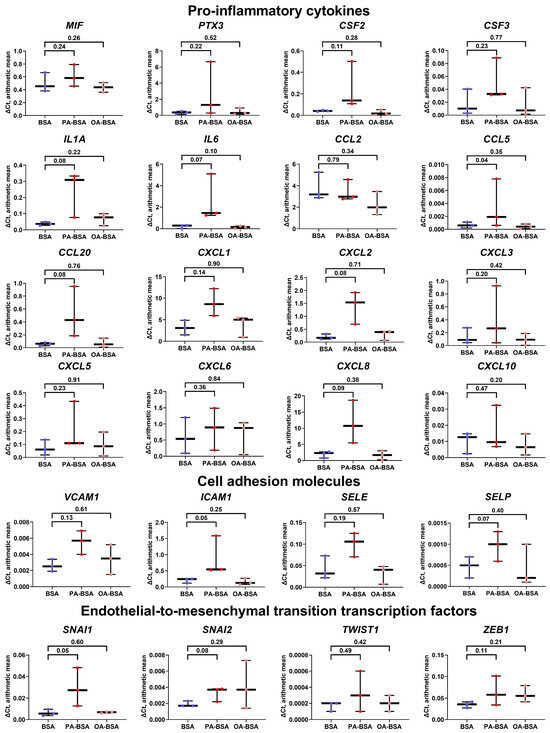

The treatment of HMVEC with PA-BSA led to the increased expression of eight of the sixteen genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (CSF2, IL6, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, and CXCL8); however, the expression of other genes (MIF, PTX3, CSF3, IL1A, CCL2, CCL5, CXCL6, and CXCL10) also showed insignificant increment (Figure 9). The expression of the VCAM1, ICAM1, and SELP genes tended to be elevated after PA-BSA treatment, although only the ICAM1 gene demonstrated a statistically significant increase (Figure 9). The expression of the genes encoding EndoMT transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1) remained unchanged upon PA-BSA exposure (Figure 9). None of the indicated genes were stimulated by OA-BSA (Figure 9). In summary, the results of RT-qPCR profiling were in concord with those obtained by phase contrast microscopy and the WST-8 cell proliferation and viability assay, showing the higher susceptibility of HAVEC and HSaVEC to PA-BSA.

Figure 9.

Relative levels of gene expression (arithmetic mean) in genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), pro-inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, and TWIST1, ZEB1) in primary human adipose tissue-derived microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range; p-values are provided above boxes, via a ratio paired t-test (i.e., ratios of paired values but not absolute differences between paired values were compared).

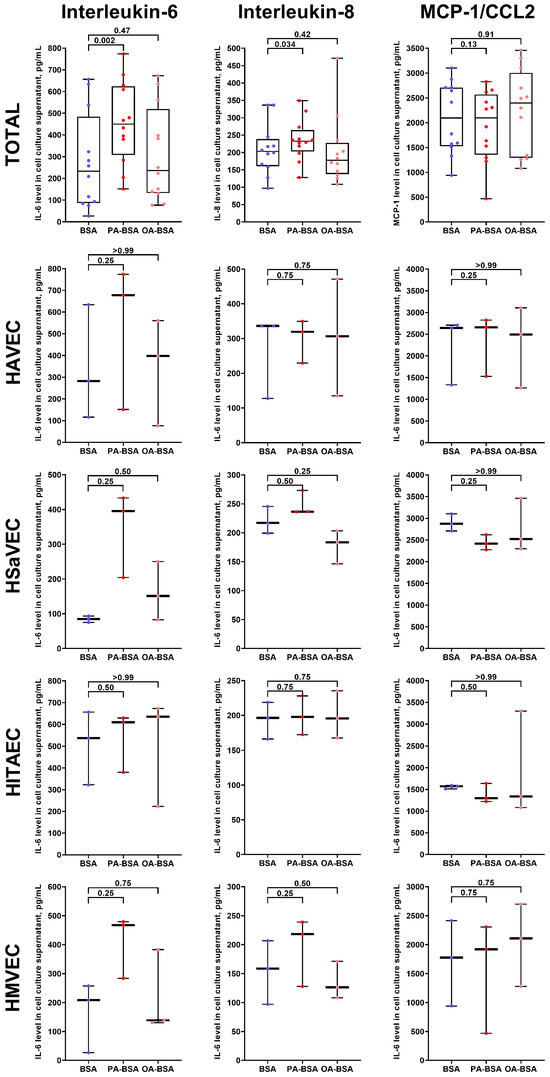

For the verification of the RT-qPCR results, we conducted an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure the cytokines with which genes demonstrated the highest average (IL-6 and IL-8) and lowest average (MCP-1/CCL2) overexpression after the incubation of ECs with PA-BSA (Figure 5). The PA-BSA treatment induced the release of IL-6 and IL-8, whilst the level of MCP-1/CCL2 remained unchanged (Figure 10), confirming the results of RT-qPCR profiling (Figure 5). Exposure to OA-BSA did not alter the production of IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1/CCL2 (Figure 10). Across the studied EC types, the increase in IL-6 after PA-BSA treatment was the highest in HAVEC, HSaVEC, and HMVEC (Figure 10), confirming the greater pro-inflammatory effects of PA-BSA on HAVEC and HSaVEC in comparison with HITAEC.

Figure 10.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measurements of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and MCP-1/CCL2 in pre-centrifuged (2000× g) serum-free cell culture supernatant from primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC), human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of two replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate) for each patient (n = 12 patients, n = 3 per each of the indicated EC types). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above the boxes, via Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test.

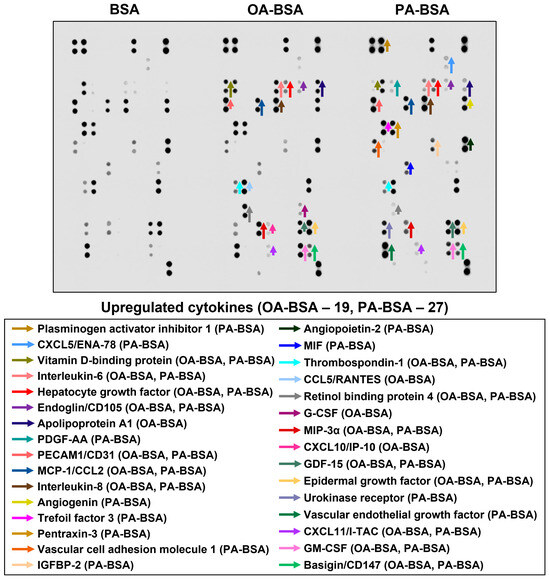

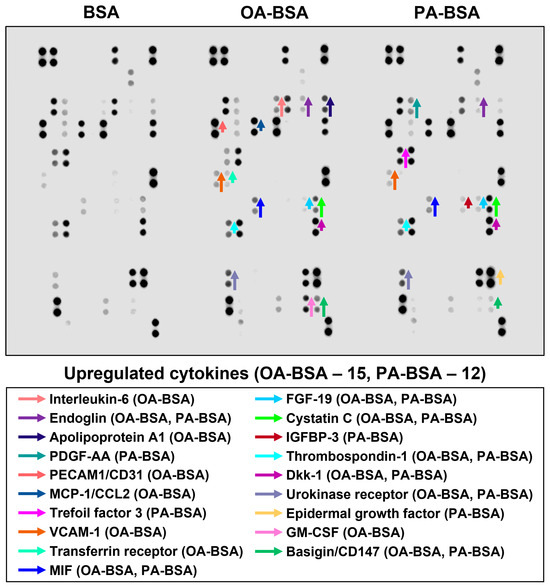

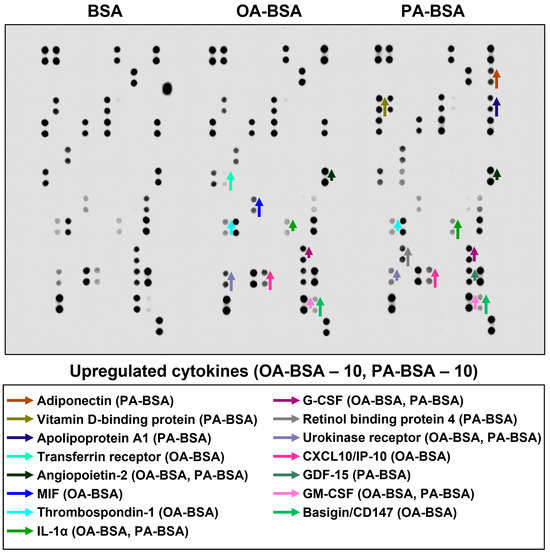

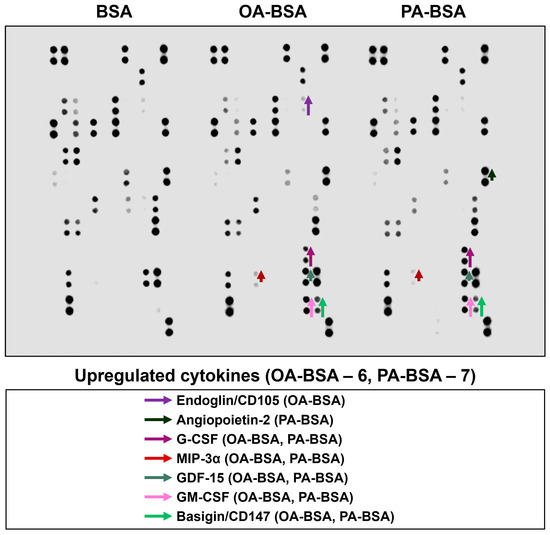

In order to perform a systematic analysis of EC type-specific responses, we carried out a dot blot profiling of 109 pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the cell culture supernatant withdrawn from HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC treated with OA-BSA or PA-BSA (Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, Table 1). Similarly to RT-qPCR results, dot blotting measurements identified that HSaVEC showed the most pronounced response to PA-BSA (27 upregulated cytokines, Figure 11) in comparison with HMVEC (12 overexpressed cytokines, Figure 12), HITAEC (10 overrepresented cytokines, Figure 13), and HAVEC (7 upregulated cytokines, Figure 14). HSaVEC exposed to PA-BSA exhibited a greater pro-inflammatory response than that treated with OA-BSA (27 and 19 upregulated cytokines, respectively, Figure 11), whereas HMVEC was slightly more sensitive to OA-BSA than to PA-BSA (15 and 12 overexpressed cytokines, respectively, Figure 12). The indicated susceptibility of HMVEC to the OA-BSA treatment at dot blot profiling (Figure 12) also corresponded to the findings revealed at RT-qPCR analysis. In concert with RT-qPCR and ELISA, dot blot profiling demonstrated the notable resistance of HITAEC to both PA-BSA and OA-BSA (ten overexpressed cytokines after both treatments, Figure 13).

Figure 11.

Semi-quantitative dot blot assessment of pro-inflammatory cytokines in pre-centrifuged (2000× g), tenfold-enriched serum-free cell culture supernatant withdrawn from primary human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. The intensity of colored black dots directly reflects the expression level of the corresponding protein. The list of cytokines overrepresented in the cell culture supernatant (with the corresponding color-coded arrows) is shown below the figure. Arrow length represents the fold change upon densitometric analysis of chemiluminescent images, performed in the ImageJ software (version 1.54k). Short, medium, and long arrows represent fold changes of 1.20–1.34, 1.35–1.49, and ≥1.50, respectively, relative to densitometric values in the BSA group. In cases where protein was not expressed in the BSA group but was detected in OA-BSA or PA-BSA groups, densitometric values ≤ 4999, from 5000 to 9999, and ≥10,000 arbitrary units were denoted with short, medium, and long arrows, respectively.

Figure 12.

Semi-quantitative dot blot assessment of pro-inflammatory cytokines in pre-centrifuged (2000× g), tenfold-enriched serum-free cell culture supernatant withdrawn from primary human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. The intensity of colored black dots directly reflects the expression level of the corresponding protein. The list of cytokines overrepresented in the cell culture supernatant (with the corresponding color-coded arrows) is shown below the figure. Arrow length represents the fold change upon densitometric analysis of chemiluminescent images, performed in the ImageJ software (version 1.54k). Short, medium, and long arrows represent fold changes of 1.20–1.34, 1.35–1.49, and ≥1.50, respectively, relative to densitometric values in the BSA group. In cases where protein was not expressed in the BSA group but was detected in OA-BSA or PA-BSA groups, densitometric values ≤ 4999, from 5000 to 9999, and ≥10,000 arbitrary units were denoted with short, medium, and long arrows, respectively.

Figure 13.

Semi-quantitative dot blot assessment of pro-inflammatory cytokines in pre-centrifuged (2000× g), tenfold-enriched serum-free cell culture supernatant withdrawn from primary human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. The intensity of colored black dots directly reflects the expression level of the corresponding protein. The list of cytokines overrepresented in the cell culture supernatant (with the corresponding color-coded arrows) is shown below the figure. Arrow length represents the fold change upon densitometric analysis of chemiluminescent images, performed in the ImageJ software (version 1.54k). Short, medium, and long arrows represent fold changes of 1.20–1.34, 1.35–1.49, and ≥1.50, respectively, relative to densitometric values in the BSA group. In cases where protein was not expressed in the BSA group but was detected in OA-BSA or PA-BSA groups, densitometric values ≤ 4999, from 5000 to 9999, and ≥10,000 arbitrary units were denoted with short, medium, and long arrows, respectively.

Figure 14.

Semi-quantitative dot blot assessment of pro-inflammatory cytokines in pre-centrifuged (2000× g), tenfold-enriched serum-free cell culture supernatant withdrawn from primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. The intensity of colored black dots directly reflects the expression level of the corresponding protein. The list of cytokines overrepresented in the cell culture supernatant (with the corresponding color-coded arrows) is shown below the figure. Arrow length represents the fold change upon densitometric analysis of chemiluminescent images, performed in the ImageJ software (version 1.54k). Short, medium, and long arrows represent fold changes of 1.20–1.34, 1.35–1.49, and ≥1.50, respectively, relative to densitometric values in the BSA group. In cases where protein was not expressed in the BSA group but was detected in OA-BSA or PA-BSA groups, densitometric values ≤ 4999, from 5000 to 9999, and ≥10,000 arbitrary units were denoted with short, medium, and long arrows, respectively.

Table 1.

Densitometric semi-quantitative analysis of cytokine levels (dot blot profiling with chemiluminescent detection) was performed in the pre-centrifuged (2000× g), tenfold-enriched, serum-free culture medium derived from primary human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC), human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Densitometric analysis was performed using the ImageJ software (version 1.54k). Fold changes of 1.20–1.34, 1.35–1.49, and ≥1.50 (relative to densitometric values in the BSA group, respectively) correspond to short, medium, and long arrows in Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. In cases where protein was not expressed in the control group but was detected in OA-BSA or PA-BSA groups, densitometric values ≤ 4999, from 5000 to 9999, and ≥10,000 arbitrary units, respectively, correspond to short, medium, and long arrows in Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Among the cytokines overrepresented in the cell culture supernatant from HSaVEC after the PA-BSA treatment were IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1/CCL2, pentraxin-3, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), macrophage inflammatory protein-3α (MIP-3α), granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), as well as chemokines CXCL5 and CXCL11 (Figure 11). The exposure of HSaVEC to PA-BSA stimulated the production of pro-angiogenic molecules—hepatocyte growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, angiogenin, trefoil factor 3, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2, angiopoietin-2, and growth differentiation factor 15—and promoted the release of soluble endothelial cell receptors endoglin/CD105, PECAM1/CD31, VCAM1/CD106, and basigin/CD147, together suggesting a development of endothelial dysfunction (Figure 11). In contrast, the pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic response of HITAEC to PA-BSA was limited to the increased release of interleukin-1α, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), GM-CSF, angiopoietin-2, and growth differentiation factor 15 (Figure 13). Collectively, the results of dot blot profiling corroborated those of RT-qPCR, indicating the notable heterogeneity regarding the response of different EC types to PA-BSA and OA-BSA.

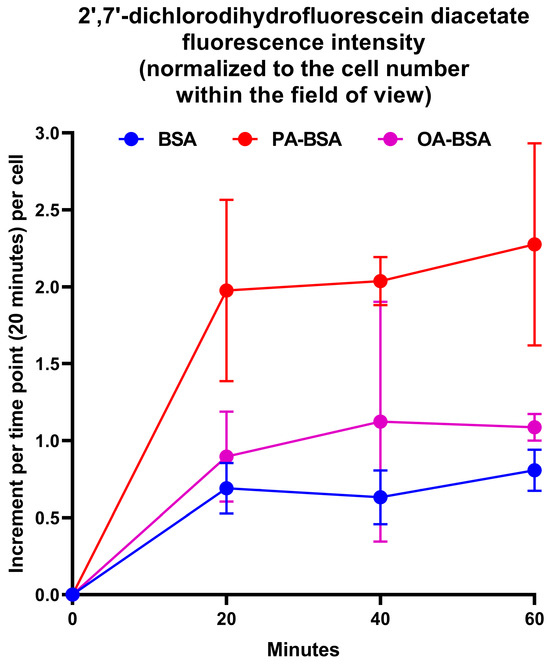

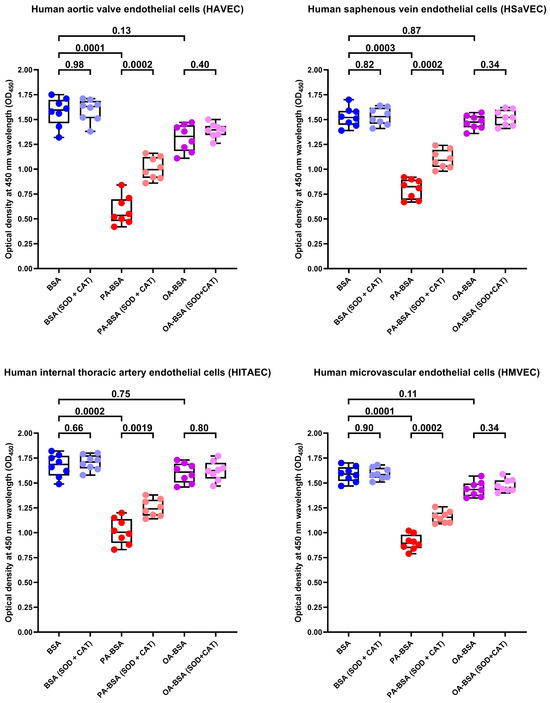

As pro-inflammatory endothelial activation is intimately connected with oxidative stress, we further tested whether PA-BSA or OA-BSA induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Treatment with PA-BSA significantly increased ROS formation, and ROS levels were from 2- to 3-fold higher in PA-BSA-treated than in BSA- or OA-BSA-treated cells (Figure 15). Exposure to OA-BSA led to the minor and insignificant ROS increase in OA-BSA-treated cells as compared to control (i.e., BSA-treated) cells (Figure 15). We then asked whether the treatment with antioxidant enzymes—i.e., superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT)—enables the rescue of ECs from PA-induced death. The co-incubation of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC with SOD (250 U/mL), and CAT (500 U/mL) for 24 h partially prevented loss of their viability during the PA-BSA treatment (Figure 16). HAVEC and HSaVEC were particularly sensitive to PA-BSA, and the rescuing effect of SOD and CAT was highest in these EC types (≈73% for HAVEC and 37% for HSaVEC as compared to 23% in HITAEC and 28% in HMVEC after the PA-BSA treatment and combined addition of SOD and CAT to the cell culture medium, Figure 16). As compared with HSaVEC and HITAEC, HAVEC and HMVEC were slightly yet insignificantly affected by OA-BSA (Figure 16). The addition of SOD and CAT did not improve the viability of OA-BSA-treated ECs that concurred with the absence of ROS generation upon the exposure to OA-BSA (Figure 16). Hence, PA-BSA-induced endothelial dysfunction was accompanied by elevated ROS generation and was ameliorated by treatment with antioxidant enzymes (SOD and CAT).

Figure 15.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS)’s generation in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 120 h. ROS generation in the ECs was detected by 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) staining after PA-BSA or OA-BSA challenge. DCF fluorescence was recorded from the same positions in wells every 20 min for a total period of 1 h (i.e., three times) with fixed exposure settings, and was normalized to the cell number within the field of view. Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of three replicates (i.e., three wells of a 96-well plate), while whiskers indicate the standard deviation.

Figure 16.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, 250 U/mL) and catalase (CAT, 500 U/mL) rescue endothelial cells (ECs) from palmitic acid (PA)-induced death. Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay) of primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC), human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above boxes. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze the pairwise comparisons with and without superoxide dismutase and catalase treatment, and the Kruskal–Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test were used for analyzing the comparisons of BSA with PA-BSA and OA-BSA.

To further examine whether the antioxidants can rescue ECs from PA-induced death, we tested the effects of L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (L-AA2P, 50 µg/mL) and sodium selenite (NaSe, 7 µg/mL), two common antioxidant additives to EC culture medium, on HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC treated with PA-BSA or OA-BSA. The addition of L-AA2P significantly increased the viability in all EC types (Figure 17). Similarly to SOD and CAT, the L-AA2P rescuing effect was higher in HAVEC and HSaVEC, which were more affected by PA-BSA (≈33% increment in viability in HAVEC, ≈30% in HSaVEC, ≈11% in HITAEC, and ≈18% in HMVEC after the PA-BSA treatment and L-AA2P supplementation as compared to PA-BSA-treated ECs without L-AA2P, Figure 17). In keeping with these findings, the addition of NaSe significantly elevated the viability of ECs regardless of their specification, although with a lower efficiency than SOD/CAT and L-AA2P (≈21% increment in viability in HAVEC, ≈17% in HSaVEC, ≈11% in HITAEC, and ≈15% in HMVEC after the PA-BSA treatment and NaSe supplementation as compared to PA-BSA-treated ECs without NaSe, Figure 18). Collectively, these results indicated the considerable role of oxidative stress in defining PA-specific endothelial toxicity and suggested the efficiency of antioxidant interventions in mitigating these detrimental effects.

Figure 17.

L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (L-AA2P, 50 µg/mL) rescues endothelial cells (ECs) from palmitic acid (PA)-induced death. Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay) of primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC), human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above the boxes. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze the pairwise comparisons with and without L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate treatment, and the Kruskal–Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test were used for analyzing the comparisons of BSA with PA-BSA and OA-BSA.

Figure 18.

Sodium selenite (NaSe, 7 µg/mL) rescues endothelial cells (ECs) from palmitic acid (PA)-induced death. Microplate colorimetric analysis of proliferation and viability (WST-8 assay) of primary human aortic valve endothelial cells (HAVEC), human saphenous vein endothelial cells (HSaVEC), human internal thoracic artery endothelial cells (HITAEC), and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC) incubated with control fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA), conjugates of palmitic acid (PA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (PA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L), or conjugates of oleic acid (OA) with a fatty acid-free BSA (OA-BSA, 0.8 mmol/L) for 24 h. Each dot on the plots represents an arithmetic mean of eight replicates (i.e., 8 wells of a 96-well plate). Box-and-whisker plot. Whiskers indicate the range, box bounds indicate the 25th–75th percentiles, and center lines indicate the median. p-Values are provided above boxes. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to analyze the pairwise comparisons with and without sodium selenite treatment, and the Kruskal–Wallis test with subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test were used for analyzing the comparisons of BSA with PA-BSA and OA-BSA.

3. Discussion

Here we report the differential effects of PA-BSA and OA-BSA on primary valvular and vascular ECs. The exposure of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC to PA-BSA caused significant cytotoxic effects, induced the expression of the genes encoding cell adhesion molecules (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, and SELP), pro-inflammatory cytokines (MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CSF2, CSF3, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, and CXCL10), and EndoMT transcription factors (SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, and ZEB1), and promoted the production of IL-6 and IL-8 into the cell culture milieu. Across the indicated EC types, PA-BSA induced the highest cytotoxicity and the strongest pro-inflammatory activation in HAVEC and HSaVEC. For instance, the treatment of HSaVEC with PA-BSA initiated a prominent release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, soluble EC receptors, and pro-angiogenic molecules into the cell culture supernatant. Although OA-BSA also showed mild-to-moderate cytotoxicity in HAVEC and HMVEC, it did not cause consistent activation in the ECs. Of all the EC types studied, HITAEC demonstrated the highest resistance to PA-BSA and did not respond to the OA-BSA treatment. The findings revealed upon the phase contrast microscopy, the colorimetric cell proliferation and viability assay (WST-8), RT-qPCR, ELISA, and dot blot profiling corresponded to each other, together suggesting considerable heterogeneity across the ECs from different vascular territories in response to PA.

Previous studies have highlighted the following hazardous effects of PA on ECs: (1) mitochondrial [104,105] and endoplasmic reticulum stress [104] resulting in the increased production of a reactive oxygen species [104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111] in a NADPH oxidase-dependent [107,110,111] and Ca2+-dependent [109] manner; (2) inhibition of cell proliferation [104], migration [105], and angiogenesis [109]; and (3) accelerated apoptosis [104,105,108], and ferroptosis [112]. The pathological effects of PA on endothelial metabolism are largely mediated by an endoplasmic reticulum stress [113] indicated by an increase in respective biomarkers (GRP78, CHOP, PERK, and ATF4) [114], impaired autophagy [115] and respiratory burst [116], and pyroptosis represents a major EC death subroutine after the exposure to PA [117]. Notably, the inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress ameliorated PA-induced endothelial dysfunction in diabetic mice [118], and the inhibition of lipolysis in the visceral adipose tissue mitigated the PA uptake by the ECs [119]. Recent studies have also shown the importance of epigenetic regulation in determining the endothelial toxicity of PA [120], which may be particularly important for senescent ECs which accumulated a significant number of epigenetic alterations [121]. Together, these findings underscore the role of endoplasmic stress and metabolic inflammation in PA-induced lipotoxicity and PA-mediated endothelial dysfunction [122,123,124].

The indicated pathological pattern was accompanied by an upregulation of the IL6, CCL2, VCAM1, ICAM1, and SELE genes [105,106,107,108], primarily via the TLR4 pathway and the activation of NF-κB transcription factor [107,108,125,126,127,128]. Among the pro-inflammatory molecules released into the extracellular milieu upon PA stimulation were IL-6 [105,107,108,126], IL-8 [126], MCP-1/CCL2 [105], and pentraxin-3 [129]. Taken together, these molecular alterations led to an increased adhesion of monocytes to ECs [105,106,130,131] via ICAM-1 [126,130] and E-selectin [132], induced EndoMT [128], and impaired insulin signaling [108,125,127,132]. In addition, PA induced the expression of endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor [108], diminished the production of a key vasodilator NO [108,109,111,125,127,128], and reduced acetylcholine-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation [110] but not vascular smooth muscle cell-dependent vasodilation [127]. In concert with the detrimental effects of PA on ECs, epidemiological studies have shown that elevated serum PA is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease [133,134], stroke [134], and cardiovascular death [135,136]. Our findings are consistent with these reports, as we also observed the enhanced transcription of multiple pro-inflammatory genes and the elevated secretion of IL-6 and IL-8 in ECs following PA treatment. However, a detailed investigation of specific signaling pathways involved in the EC response to PA requires further functional experiments (e.g., inhibition or rescue studies) in order to establish the causal conclusions.

In vitro experiments demonstrated a cell- and fatty acid-specific pattern of lipid deposition in liver sinusoidal ECs and hepatocytes, showing considerable chemical differences in PA- and OA-generated lipid droplets [137]. PA significantly inhibited the proliferation of ECs and caused an increase in caspase-3 expression [138]. Vice versa, OA slightly accelerated cell growth, although also leading to a mild elevation of caspase-3 [138]. The incubation of TNFα-stimulated ECs with palmitoleic acid and OA did not trigger an increase in IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1/CCL2, though exposure to PA led to an elevation of these cytokines in the cell culture supernatant [139]. Similarly to palmitoleic acid, the combination of PA and OA abrogated the adverse effects regardless of the EC type [140]. Furthermore, incubation with oleate even reduced VCAM-1 [141] and ICAM-1 expression [142] and NF-κB activation [141,142], and OA mitigated the hazardous effects of other endothelial dysfunction triggers [141]. Whilst PA induced insulin resistance, OA protected against it, also reducing the release of MCP-1/CCL2 and augmenting eNOS biosynthesis [142]. OA-enriched extracellular vesicles contributed to cell viability and proliferation, whereas PA-modified extracellular vesicles promoted cell death via necroptosis [143]. Yet, other studies have found a mitochondrial dysfunction, a dose-dependent increase in mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species, a reduction in basal and insulin-dependent eNOS biosynthesis, an increase in endothelin-1 release, an NF-κB activation, and a moderate cytotoxicity after the exposure of ECs to OA [144,145,146]. The effects of OA might be cell-dependent, as oleate reduced energy production, impaired mitochondrial respiration and triggered cell death in liver sinusoidal ECs but not human umbilical vein ECs [140]. This corresponds to the findings of our study, in which OA showed a mild-to-moderate cytotoxicity in HAVEC and HMVEC but not HSaVEC and HITAEC, suggesting that the effects of OA significantly depend on the EC type.

After the digestion of fat in the small intestinal lumen, non-esterified PA and OA associate with bile salt micelles, are absorbed by enterocytes through passive diffusion and fatty acid transporters, and undergo re-esterification into triglycerides, which are further incorporated into chylomicrons [1,4,8,10,11]. Via the lymphatic system, chylomicrons then enter the bloodstream where endothelial lipoprotein lipase hydrolyzes triglycerides and release free PA and OA, which are further internalized by ECs and peripheral tissues by the abovementioned mechanisms, or remain in circulation as bound to albumin [1,4,8,10,11]. However, the pathophysiological and clinical consequences of PA excess need further investigation. A randomized controlled trial in this regard found a negative correlation between the OA-to-PA ratio (i.e., monounsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio) and postprandial concentrations of tissue factor, fibrinogen, and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, supporting arguments declaring the benefits of diets rich in olive oil [147]. In addition, the PA-enriched diet disrupts biological rhythms (i.e., the circadian clock), leading to the pathological alterations of sleep architecture and the physiological parameters during sleep even in healthy individuals [148]. Monocytes isolated from Western style-fed cynomolgus macaques were characterized by a pro-inflammatory transcriptional phenotype as compared with Mediterranean style-fed macaques [149]. Such a phenotype, in turn, was associated with increased anxiety and deteriorated social integration [149], corresponding to the abovementioned sleep disorders [148].

Even after the large systematic review and meta-analysis, it remains unclear whether the Mediterranean-style diet positively affects cardiovascular outcomes [150]. Yet, a shift from the lipid-rich Western-style to Mediterranean-style diet in order to perform a PA-to-OA replacement might have benefits for the patients with a high risk of myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke, preventing a repeated major adverse cardiovascular event. Such a PA-deficient and OA-enriched dietary pattern has the potential to delay the development of endothelial dysfunction and its pathophysiological (i.e., arterial hypertension, chronic low-grade inflammation, or atherosclerosis) and clinical (i.e., coronary artery disease, chronic brain ischemia, deep vein thrombosis, or frailty syndrome) consequences. Taking together our and previous findings, we suggest the advantage of PA restriction for maintaining endothelial homeostasis and vascular health. As the proper fatty acid intake is indispensable for sustainable metabolism and cell membrane synthesis, the partial replacement of PA with relatively harmless OA in the diet might be considered as a promising cardioprotective nutritional intervention. Further prospective studies or meta-analyses are required to test this hypothesis, which relies on the specific endothelial toxicity of PA as compared with OA.

Although we cannot completely exclude that inherited variation or specific disease-associated epigenetic or transcriptional adaptations could affect the cellular responses to PA-BSA and OA-BSA exposure, we performed all treatments (BSA, PA-BSA, and OA-BSA) in parallel for all EC types in order to minimize the patient-dependent variability. Although the extent of cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects differed between HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC (i.e., HAVEC and HSaVEC were more susceptible to PA-BSA whilst HAVEC and HMVEC were also affected by OA-BSA), PA-BSA consistently exerted considerable pathological effects across EC types. Such reproducibility suggests that the observed effects are primarily attributable to fatty acid exposure rather than to intrinsic genetic or disease-related background. Earlier studies of the pro-inflammatory effects of PA and the neutral or anti-inflammatory behavior of OA on the ECs from healthy donors and immortalized EC lines [137,138,139,140,141,142] provide additional evidence that these effects are specific to PA or OA rather than to the patient predisposition. We should also note that our study was focused on the investigation of cytotoxic and transcriptional response to PA and OA in the context of endothelial heterogeneity and did not interrogate the molecular mechanisms behind these effects. The advantages of our study include use of the following: distinct EC types (HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC), several donors per each EC type, and broad gene expression profiling. The study’s shortcomings include its limited proteomic profiling because of its use of fatty acid-free albumin, which restricts the application of ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry but is necessary to carry PA and OA into ECs. Yet, the consistency of the results of phase contrast microscopy, colorimetric cell viability and proliferation assay, RT-qPCR, ELISA, and dot blotting suggests the considerable role of endothelial specification in defining the consequences of the exposure to PA or OA.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of PA-BSA and OA-BSA Conjugates

The PA-BSA and OA-BSA conjugates were prepared according to the previously published protocols [151,152] with modifications. Fatty acid-free BSA (≥98.0% purity, <0.01% fatty acids, PM-T1727, Biosera, Cholet, France) was dissolved to 20% in serum-free EndoLife medium (EL1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) with the overnight rotation at 4 °C. The solution was then centrifuged for 40 min at 4500× g to remove any insoluble aggregates. The supernatant was sterilized by passing it through 0.22 μm syringe filters with a polyethersulfone membrane (Acrodisc, 4612, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). Sodium palmitate (≥98.5% purity, P9767, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) or sodium oleate (≥99% purity, O7501, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 50% ethanol at 60 °C, transferred to the laminar hood, and added dropwise under constant stirring into fatty acid-free BSA solution, which was pre-warmed to 60 °C to achieve the final fatty acid concentration of 8.0 mmol/L and the 2.7 (mol:mol) ratio of fatty acid to BSA. Special care was taken to avoid any foaming of the solution and clouding due to palmitate precipitation. The control fatty acid-free BSA solution was made in the same fashion but using 50% ethanol without sodium palmitate or sodium oleate. Both solutions were kept for 20 min at 45 °C in a water bath with occasional stirring and then left for 5 days at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator (MCO-18AIC, PHCbi, Tokyo, Japan) to ensure complete conjugation of sodium palmitate and sodium oleate with a fatty acid-free BSA and the absence of residual fatty acid micelles. Finally, the PA-BSA and OA-BSA conjugates were sterilized by 0.22 µm filtration before their addition to cultured cells. Selected batches of conjugates were subjected to gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis with fatty acid standards to confirm that the added and measured amounts of fatty acids were equal.

4.2. Isolation of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC

The study was conducted according to the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), and the donor study protocol was ap-proved by the Local Ethical Committee of the Research Institute for Complex Issues of Cardiovascular Diseases (Kemerovo, Russia, protocol code: 7/2024, date of approval: 16 September 2024). Written informed consent was provided by all the study participants after receiving a full explanation of the study’s purposes.

HAVEC were isolated from aortic valve leaflets which were excised from patients with calcific aortic valve disease in a cardiac surgery unit #1 of the Research Institute for Complex Issues of Cardiovascular Diseases. Upon the excision, the tissues were immediately transferred into the cell culture laboratory in 15 mL tubes (601002, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) filled with EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) to preserve EC viability. Following the delivery, aortic valve leaflets were extensively washed in DPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions (pH = 7.4, 1.2.4.7, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia) and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in 0.20% type IV collagenase solution (specific activity ≥ 160 U/mg, derived from Clostridium histolyticum, GC305015, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China). After vortexing the aortic valve for one minute to detach HAVEC, the flush was centrifuged at 300× g for five minutes, and HAVEC were seeded into T-25 cell culture flasks (07-9025, Biologix Plastic (Changzhou) Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) coated with 0.1% gelatin (1.4.6, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia) and filled with EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia). The next day, we replaced EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) with EndoBoost Plus medium (EB2, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia), and the cells were grown until reaching confluence.

HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC were isolated from saphenous vein (≈2 cm length) and internal thoracic artery segments (≈1 cm length) and fragments of subcutaneous fat (10 mL), which were excised from the patients who underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery because of coronary artery disease, in cardiac surgery unit #1 of the Research Institute for Complex Issues of Cardiovascular Diseases. Upon the excision, the tissues were immediately transferred into the cell culture laboratory in 15 mL tubes (601002, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) filled with EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) to preserve EC viability. Then, the tissues were extensively washed in DPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions (pH = 7.4, 1.2.4.7, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia). Saphenous vein and internal thoracic artery segments were dissected longitudinally whilst adipose tissue fragments were cut into equal and small pieces, with the subsequent incubation in 15 mL tubes (601002, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) with 0.15% type IV collagenase solution (specific activity ≥ 160 U/mg, derived from Clostridium histolyticum, GC305015, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 60 min at 37 °C. Following the incubation, the samples were slightly vortexed for 2 min for better shedding of ECs. Enzymatic digestion was halted by the addition of 5% fetal bovine serum (1.1.6.1, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia) dissolved in DPBS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions (pH = 7.4, 1.2.4.7, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia). The saphenous vein and internal thoracic artery segments were then discarded, whereas adipose tissue was removed by the cell strainers (70 µm pore diameter, 15-1070, Biologix Plastic (Changzhou) Co., Ltd., Jinan, China). The cells (HSaVEC, HITAEC, or HMVEC suspension) were centrifuged at 220× g for 5 min at room temperature and then seeded into T-25 cell culture flasks (07-9025, Biologix Plastic (Changzhou) Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) coated with fibronectin (10 µg/mL, 1.4.11, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia) and filled with EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia). The next day, we replaced EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) with EndoBoost Plus medium (EB2, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia), and the cells were grown until reaching confluence.

HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC were then purified using magnetic cell separation technique (EasySep magnet, STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and CD31+ microbeads (CD31 Dynabeads, 11155D, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC was evaluated by flow cytometry, employing mouse phycoerythrin-cyanine 7-labeled anti-human CD146 (361008, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-human CD31 (303104, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and mouse Alexa Fluor 700-labeled anti-human CD90 (328120, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) monoclonal antibodies as well as respective isotype controls (400126, 400108, and 400144, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Cell cultures with ≥99.5% CD146+ CD90− cells were treated as HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC and therefore were used for the subsequent experiments. The protocol for the isolation of these EC cultures has been described in detail in our previous papers [153,154]. Subculturing (i.e., passaging) was performed using EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia), and EndoBoost Plus medium (EB2, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) was then used to grow cells until confluence in each passage. For the subculturing, we used T-25 or T-75 cell culture flasks (07-9025 or 07-8075, respectively, Biologix Plastic (Changzhou) Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) coated with 0.1% gelatin (1.4.6, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia).

4.3. Phase Contrast Microscopy and Sample Collection

HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC were seeded into T-25 flasks (n = 3 cultures per EC type, n = 12 cell cultures in total, 708003, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) and grown using EndoBoost Plus medium (EB2, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) until reaching confluence. Immediately before the experiments, we removed serum-supplemented EndoBoost Plus medium (EB2, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia), washed the cells twice with warm (≈37 °C) DPBS, without Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions, (pH = 7.4, 1.2.4.7, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia) to remove the residual serum components, and then incubated the cells with serum-free EndoLife medium (EL1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) containing 0.8 mmol/L BSA, PA-BSA, or OA-BSA for 24 h. The plasma concentrations of PA and OA in healthy individuals vary from 0.1 to 0.4 mmol/L [155], and exposure to their excessive levels (i.e., from 0.8 to 1.0 mmol/L) for from 4 to 24 h is typically employed in cell culture studies [156,157,158,159].

Following 24 h of exposure, we examined cells by phase contrast microscopy (AxioObserver.Z1, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), withdrew the cell culture medium into 15 mL tubes (601002, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China), washed cells with ice-cold (4 °C) PBS (pH = 7.4, 2.1.1, BioLot, St. Petersburg, Russia), and lysed the cells in TRIzol reagent (15596018, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to extract RNA according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The cell culture medium was centrifuged at 220× g (5804R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) to sediment detached cells and at 2000× g (MiniSpin Plus, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) to sediment the cell debris. Then, the cell culture supernatant was transferred into the new low-protein binding tubes (Ac-ACT-017 L-B-S, Accumax Lab Devices Pvt. Ltd., Gujarat, India) and frozen at −80 °C (DW-86L486E, Haier Biomedical, Qingdao Haier Biomedical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China) for the subsequent ELISA measurements.

4.4. WST Assay for Cell Proliferation and Viability

Confluent cultures of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC were seeded into 96-well plates (701001, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) using serum-supplemented EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia). The day after the seeding, we replaced the EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) with a serum-free EndoLife medium (EL1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) containing 0.8 mmol/L BSA, PA-BSA, or OA-BSA for 24 h. Then, we replaced the medium with 100 µL of fresh serum-free EndoLife medium (EL1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia), added 10 µL of WST-8 reagent (G4103, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 2 h, and conducted a colorimetric detection using a spectrophotometer (Multiskan Sky, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a 450 nm wavelength.

4.5. Gene Expression Analysis

Gene expression analysis in BSA-, PA-BSA-, and OA-BSA-treated HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC was performed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR), as in our previous studies [56,160,161] (n = 3 patients per EC type, n = 12 patients in total). In each RT-qPCR measurement, we made three technical replicates for each patient in order to conduct an objective calculation of the arithmetic mean. Briefly, M-MuLV–RH First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (R01-250, Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) and reverse transcriptase M-MuLV–RH (R03-50, Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) was used for the reverse transcription, and RT-qPCR was carried out employing customized primers (500 nmol/L each, Evrogen, Moscow, Russia, Table 2), cDNA (20 ng), and BioMaster HS-qPCR Lo-ROX SYBR Master Mix (MHR031-2040, Biolabmix, Novosibirsk, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantification of the mRNA levels (VCAM1, ICAM1, SELE, SELP, MIF, PTX3, CSF2, CSF3, IL1A, IL6, CCL2, CCL5, CCL20, CSF2, CSF3, CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8, CXCL10, SNAI1, SNAI2, TWIST1, ZEB1, NOS3, VWF, SERPINE1, PLAU, and PLAT genes) was performed by calculation of ΔCt and by using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The relative transcript levels were expressed as a value relative to the average of PECAM1 gene and to the mock-treated group (2−ΔΔCt).

Table 2.

Primer sequences for reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

4.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Quantitative measurement of the IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1/CCL2 levels in the cell culture supernatant was performed using the respective ELISA kits (A-8768, A-8762, and A-8782, Vector-Best, Novosibirsk, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocols (n = 2 technical aliquotes per cell culture sample; n = 12 samples per group). For each ELISA measurement, we loaded 100 µL of cell culture supernatant across all samples. The colorimetric detection of ELISA results was conducted using a spectrophotometer (Multiskan Sky, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a 450 nm wavelength.

4.7. Dot Blot Profiling

The semi-quantitative analyses of 109 cytokines and chemokines in the cell culture supernatant were performed using Proteome Profiler Human XL Cytokine Array Kits (ARY022B, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In order to improve the sensitivity of dot blot profiling, all samples of cell culture supernatant were concentrated to equal volumes (tenfold, from 3330 μL to 333 μL per sample) utilizing a vacuum centrifugal concentrator (HyperVAC-LITE, Gyrozen, Gimpo, Republic of Korea). For each EC type, samples from three different patients were pooled into a single sample (i.e., 1 mL of concentrated cell culture supernatant per EC type) to obtain an average result. The chemiluminescent detection was conducted using the Odyssey XF imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The densitometric analysis of the chemiluminescent images was performed employing ImageJ software (version 1.54k, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.8. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species Generation

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) obtained from three healthy donors (passage three) were cultured in gelatin-coated 96-well plates (µClear, Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria) for 5 days with a daily change in human microvascular endothelial cell medium (111-500, Cell Applications, San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 0.8 mmol/L BSA, PA-BSA, or OA-BSA. Prior to the ROS measurements, the medium was replaced with a fresh medium containing 10 µmol/L 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h and then with a Hank’s balanced salt solution without phenol red (P020p, PanEco, Moscow, Russia) containing 10 mmol/L of 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, F134E-100, PanEco, Moscow, Russia). The microplates were placed on an automated coordinate stage of the Axiovert 200 M fluorescent microscope equipped with an on-stage incubator and AxioCamHR camera (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The DCF fluorescence was recorded from the same positions in wells every 20 min for a total period of 1 h (i.e., three times) using ×32 objective and fixed exposure settings. In parallel, phase contrast images of cells in the same fields of view were acquired to determine the number of cells producing the fluorescent signal. As PA-BSA reduced cell viability, ROS fluorescence was normalized by the number of survived cells. The data were expressed as an increase in DCF fluorescence over 1 h per cell.

4.9. Rescue Experiments

Confluent cultures of HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC were seeded into 96-well plates (701001, Wuxi NEST Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China) using serum-supplemented EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia). The day after the seeding, we replaced the EndoBoost medium (EB1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) with a serum-free EndoLife medium (EL1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia) and treated ECs with 0.8 mmol/L of BSA, PA-BSA, or OA-BSA for 24 h, with or without the following: (1) antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase (SOD, 250 U/mL, S5395, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and catalase (CAT, 500 U/mL, SRE0041, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA); (2) antioxidant cell culture supplement L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (L-AA2P, 50 µg/mL, A2521, TCI Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan); and (3) antioxidant cell culture additive sodium selenite (NaSe, 7 µg/mL, F080, PanEco, Moscow, Russia). The abovementioned antioxidants were added to ECs 3 h before their exposure to BSA, PA-BSA, or OA-BSA, to ensure their internalization through the plasma membrane. After 24 h of incubation, we replaced the medium with 100 µL of fresh serum-free EndoLife medium (EL1, AppScience Products, Moscow, Russia), added 10 µL WST-8 reagent (G4103, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 2 h, and conducted a colorimetric detection using a spectrophotometer (Multiskan Sky, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a 450 nm wavelength.

4.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For the WST-8 assay, data are presented as median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and range, and the groups were compared by the Mann–Whitney U-test (in the case of pairwise comparisons) or by the Kruskal–Wallis test with a subsequent Dunn’s multiple comparisons test to perform a respective adjustment. For RT-qPCR analysis, data are presented as an arithmetic mean and standard deviation, and groups were compared by a ratio paired t-test (i.e., ratios of paired values but not absolute differences between paired values were compared) because of the considerable between-sample variability in absolute values and selected metric (fold change). For the ELISA measurements, data are presented as median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and range, and groups were compared by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test because of the considerable between-sample variability in absolute values. p-Values ≤ 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

PA-BSA is detrimental for ECs and provokes an evident pro-inflammatory response in all EC types, primarily HAVEC and HSaVEC. Although OA-BSA exerts moderate cytotoxic effects on HAVEC and HMVEC, it does not induce generalized EC activation. Across the four studied EC types (HAVEC, HSaVEC, HITAEC, and HMVEC), HITAEC was the most resistant to PA-BSA exposure and was not affected by OA-BSA. Collectively, these results suggest significant heterogeneity in the response to PA-BSA in the ECs from different vascular beds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., A.M., A.V., V.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); data curation, D.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); formal analysis, D.S., V.M. (Victoria Markova), Y.Y., A.F., A.L., M.S., A.S. (Anna Sinitskaya), V.M. (Vera Matveeva), E.T., A.S. (Alexander Stepanov), A.K. (Asker Khapchaev), N.P. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); funding acquisition, D.S.; investigation, D.S., V.M. (Victoria Markova), Y.Y., A.F., A.L., M.S., A.S. (Anna Sinitskaya), V.M. (Vera Matveeva), E.T., A.S. (Alexander Stepanov), A.K. (Asker Khapchaev) and N.P.; methodology, D.S., V.M. (Victoria Markova), Y.Y., A.F., A.L., M.S., A.S. (Anna Sinitskaya), V.M. (Vera Matveeva), E.T., A.S. (Alexander Stepanov), A.K. (Asker Khapchaev), N.P., V.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); project administration, D.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); resources, A.M., A.K. (Asker Khapchaev), A.V., V.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); software, A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); supervision, D.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); validation, D.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); visualization, D.S., Y.Y. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); writing—original draft, A.K. (Anton Kutikhin); and writing—review and editing, A.K. (Asker Khapchaev), A.V., V.S. and A.K. (Anton Kutikhin). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the article processing charge were funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-65-00039 “Identification of circulating endothelial dysfunction marker in context of endothelial heterogeneity” (Daria Shishkova), https://rscf.ru/project/24-65-00039/ (accessed on 14 December 2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), and the donor study protocol was approved by the Local Ethical Committee of the Research Institute for Complex Issues of Cardiovascular Diseases (Kemerovo, Russia, protocol code: 7/2024, date of approval: 16 September 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Palomer, X.; Pizarro-Delgado, J.; Barroso, E.; Vázquez-Carrera, M. Palmitic and Oleic Acid: The Yin and Yang of Fatty Acids in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 29, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesga-Jiménez, D.J.; Martin, C.; Barreto, G.E.; Aristizábal-Pachón, A.F.; Pinzón, A.; González, J. Fatty Acids: An Insight into the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, G.; Murru, E.; Banni, S.; Manca, C. Palmitic Acid: Physiological Role, Metabolism and Nutritional Implications. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annevelink, C.E.; Sapp, P.A.; Petersen, K.S.; Shearer, G.C.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Diet-derived and diet-related endogenously produced palmitic acid: Effects on metabolic regulation and cardiovascular disease risk. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2023, 17, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shramko, V.S.; Polonskaya, Y.V.; Kashtanova, E.V.; Stakhneva, E.M.; Ragino, Y.I. The Short Overview on the Relevance of Fatty Acids for Human Cardiovascular Disorders. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattore, E.; Fanelli, R. Palm oil and palmitic acid: A review on cardiovascular effects and carcinogenicity. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Becerra, K.; Ramos-Lopez, O.; Barrón-Cabrera, E.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Milagro, F.I.; Martínez-López, E.; Martínez, J.A. Fatty acids, epigenetic mechanisms and chronic diseases: A systematic review. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiter, C.; Singha, S.K.; Khalili, R.; Shariat-Madar, Z. Free Fatty Acids: Circulating Contributors of Metabolic Syndrome. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 16, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zong, G.; Li, H.; Lin, X. Fatty acids and cardiometabolic health: A review of studies in Chinese populations. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Figueiredo, P.; Carla Inada, A.; Marcelino, G.; Maiara Lopes Cardozo, C.; de Cássia Freitas, K.; de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães, R.; Pereira de Castro, A.; Aragão do Nascimento, V.; Aiko Hiane, P. Fatty Acids Consumption: The Role Metabolic Aspects Involved in Obesity and Its Associated Disorders. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, A.M.; Lenighan, Y.M.; O’Reilly, M.E.; McGillicuddy, F.C.; Roche, H.M. Nutritional modulation of metabolic inflammation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A.; Martinez, K.; Chuang, C.C.; LaPoint, K.; McIntosh, M. Saturated fatty acid-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue: Mechanisms of action and implications. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbecki, J.; Bajdak-Rusinek, K. The effect of palmitic acid on inflammatory response in macrophages: An overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, T.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Pan, C.; Chu, X.; Xiong, J.; Xie, J.; Chang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Obesity-induced elevated palmitic acid promotes inflammation and glucose metabolism disorders through GPRs/NF-κB/KLF7 pathway. Nutr. Diabetes 2022, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Hu, X.; Gong, R.H.; Huang, C.; Chen, M.; Wong, H.L.X.; Bian, Z.; Kwan, H.Y. Palmitic acid is an intracellular signaling molecule involved in disease development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 2547–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global Impacts of Western Diet and Its Effects on Metabolism and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heindel, J.J.; Lustig, R.H.; Howard, S.; Corkey, B.E. Obesogens: A unifying theory for the global rise in obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2024, 48, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, I.; Sonestedt, E.; Ericson, U.; Wallström, P.; Orho-Melander, M. A Western dietary pattern is prospectively associated with cardio-metabolic traits and incidence of the metabolic syndrome. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odegaard, A.O.; Koh, W.P.; Yuan, J.M.; Gross, M.D.; Pereira, M.A. Western-style fast food intake and cardiometabolic risk in an Eastern country. Circulation 2012, 126, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]