Abstract

Non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate (ns-CL/P) is one of the most common craniofacial anomalies with a multifactorial etiology. To investigate the contribution of rare variants to disease risk, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) in 58 patients with ns-CL/P from a homogeneous Polish population, excluding from analysis 423 previously investigated cleft candidate genes. After stringent filtering, prioritization, and segregation analysis, we identified 31 likely pathogenic (LP) variants across 30 genes, significantly enriched in categories related to developmental processes. Notably, 29% of variants occurred in genes not previously linked to clefting, including AGO1, ARID1A, ATP1A1, FOXA2, GDF7, HOXB3, LRP5, MAML1, and ZNF319. Three were de novo: FOXA2_p.Arg260Pro, MAML1_p.Gln65Ter, and ZNF319_p.Gln64Ter. Most of the remaining variants were inherited from unaffected parents, suggesting incomplete penetrance and possible modifier effects consistent with the heterogeneous etiology of ns-CL/P. Additionally, analysis of common variants in the 30 loci harboring rare LP variants revealed nominal associations with ns-CL/P for NXN, EXT1, MAML1, and TP53BP2 loci. These results support the candidacy of these genes and suggest contributions from both rare and common variants. In conclusion, we report novel LP variants expanding the spectrum of candidate genes and providing new insights into the genetic landscape of orofacial clefts.

1. Introduction

Non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate (ns-CL/P) is the most frequent type of orofacial clefting, affecting approximately 1 in 1000 live births in European populations [1,2]. The condition is clinically heterogeneous and is usually subdivided into cleft lip (ns-CL) and cleft lip with cleft palate (ns-CLP). Evidence from embryology and epidemiology indicates that these subtypes are not identical in origin and may involve distinct genetic mechanisms [2,3]. Beyond the structural defect, ns-CL/P is accompanied by a wide range of medical and psychosocial problems. Affected individuals may experience feeding difficulties, recurrent ear infections, impaired speech, and malocclusion, while concerns about facial appearance and treatment burden add further challenges. Families, in turn, often face substantial psychological stress and financial strain [1,4]. Lifelong multidisciplinary care is typically required, beginning with surgical repair and extending through orthodontic, speech, and psychological interventions. For these reasons, ns-CL/P is not only a congenital malformation but also a public health concern with lasting consequences for quality of life and healthcare systems.

The etiology of ns-CL/P is widely recognized as multifactorial, involving the interplay of genetic and environmental factors [5,6]. In recent years, attention has also turned to epigenetic influences and non-coding RNAs. DNA methylation and histone modifications can alter the expression of key developmental genes, thereby influencing specific cleft subtypes [7,8,9,10]. Genes under such epigenetic control include those encoding transcription factors and signaling molecules [11]. MicroRNAs, such as miR-140, miR-149, and miR-300, have been implicated in fine-tuning gene expression programs required for craniofacial morphogenesis, and variants in miRNA genes have also been linked to ns-CL/P [12,13]. Together, these findings emphasize that epigenetic regulation is an important modifier of both genetic susceptibility and the observed phenotype.

Family and twin studies provide strong evidence for the heritability of ns-CL/P. Estimates suggest that 50–80% of liability is genetically determined [5,14]. First-degree relatives of affected individuals carry a substantially higher recurrence risk; for example, an up to 32-fold increase has been reported compared with the general population [15]. Concordance rates of 40–60% in monozygotic twins, compared with only 3–5% in dizygotic twins, further support a strong genetic influence, although not the sole determinant [16]. These data indicate an important hereditary component, but also suggest that incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity are shaped by genetic modifiers and environmental exposures.

Over the past two decades, numerous loci and candidate genes have been proposed as contributors to ns-CL/P based on linkage studies, candidate-gene analyses, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [2,6]. However, results are often inconsistent between populations, reflecting the disorder’s heterogeneity. The most reproducible findings across diverse populations involve IRF6 (OMIM *607199) and the non-coding region of chromosome 8q24, both consistently confirmed as major risk loci [17,18,19]. Beyond these well-established signals, many additional genes and pathways have been implicated, but their effects often appear population-specific, underscoring the complexity of unraveling the genetic architecture of this malformation.

More recently, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has substantially expanded our understanding of the genetic basis of ns-CL/P, particularly by uncovering the contribution of rare variants with potentially large effects. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and targeted multigene panels have revealed numerous rare and ultra-rare pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants in both established candidate genes and previously unsuspected loci [20,21,22,23,24]. These findings highlight the marked heterogeneity of ns-CL/P, with reported variants including de novo variants (DNVs), alleles inherited from affected parents, and variants transmitted by unaffected carriers. Rare variants with moderate or high penetrance are thought to act either as significant contributors and major drivers of the phenotype [25,26] or as genetic modifiers that may interact with environmental influences, contributing to phenotypic variability and expressivity. While common variants explain part of the heritability, rare coding and splicing variants constitute an equally important, though incompletely defined, source of genetic risk. Recent sequencing efforts also point to DNVs as a reservoir of novel candidate genes, adding another layer of complexity [27].

Despite substantial progress, the full genetic background of ns-CL/P remains unresolved. Many of the rare P/LP variants described so far are private to single patients or families, and numerous candidate genes have been reported only once without independent replication. Combined with strong population-specific effects, this heterogeneity hampers the establishment of a definitive catalog of ns-CL/P genes. To help address this gap, we previously analyzed 423 cleft genes in a Polish cohort using WES and detected rare coding and splicing variants in both established and novel loci, such as EFTUD2 (OMIM *603892), JAG1 (OMIM *601920), and SHH (*OMIM 600725), among others [21]. In the present study, we extend this analysis to all remaining coding genes captured by WES, with the aim of identifying additional rare variants that may influence susceptibility to ns-CL/P.

2. Results

2.1. Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) Results

After initial variant selection and prioritization, 263 heterozygous single nucleotide variants (SNVs; 3–8 per patient) were designated for confirmation and segregation analyses. Based on the obtained results and annotation data for each variant and its gene, a final set of 31 LP variants in 30 genes was established. Detailed characteristics and in silico pathogenicity scores of all identified variants are provided in Table 1 and Table 2, while Tables S1 and S2 summarize the characteristics of the affected genes.

Table 1.

Rare likely pathogenic nucleotide variants identified in ns-CL/P patients.

Table 2.

Pathogenicity predictions of rare likely pathogenic nucleotide variants identified in ns-CL/P patients.

One of the identified variants, VWA8 p.Arg668Gln (rs138075452), had previously been classified as LP for non-syndromic cleft lip and palate in the ClinVar database and was also reported in a previous study [28]. This variant, with a Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score of 27.9, was detected in a patient with ns-CLP and his affected father. Two other variants transmitted from affected parents were novel and located in GDF7 (p.Leu361Phe; CADD = 27) and FAT1 (p.Ile895AspfsTer2; MutPred-LOF = 0.54). Variants in these genes have not previously been associated with orofacial clefts in either humans or mice. A novel splicing variant in LRP5 (c.3638-1G>A; adaptive boosting: ADA score 0.999) was detected in both siblings with ns-CLP but was inherited from their healthy mother.

Among the LP variants, three were confirmed de novo mutations with verified maternity and paternity. All three occurred in patients with ns-CLP. These included a missense variant in FOXA2 (p.Arg260Pro, CADD = 35), predicted as pathogenic or deleterious by all applied tools, and two nonsense variants: MAML1 (p.Gln65Ter; MutPred-LOF = 0.50) and ZNF319 (p.Gln64Ter; MutPred-LOF = 0.45). All three genes were classified as likely or very likely dominant and had not been previously implicated in clefting.

The remaining LP variants consisted of novel or ultra-rare missense variants (minor allele frequency: MAF ranging from 0.00 to 2.20 × 10−5) and one frameshift variant, all inherited from healthy parents. The missense variants with the highest CADD scores (≥32) included ARID1A p.Arg2143His (rs2124148967), CTNNA1 p.Ser810Phe, and MYH3 p.Arg18Trp (rs750940457). In total, nine missense variants were identified in genes previously implicated in ns-CL/P: CTNNA1, EFNB2, HIF1A, LAMA5, IFT172, MYH3, RYR1 (two variants), and TENM4 [22,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. The two RYR1 variants (p.Leu3046Val, rs2145659189; p.Asn3066Lys, rs201863144) occurred in cis in the same patient. Five genes harboring missense variants (ATN1, IFT172, MYH3, NXN, and RYR1) had previously been associated with syndromic forms of clefts, and 13 (EFNB2, EXT1, HAND1, IFT172, KRT17, MEN1, NCOR2, NXN, ROBO1, RPGRIP1L, RYR1, SLC32A1, and TP53BP2) were reported to cause orofacial clefts in knockout mouse models.

Among the 30 genes identified in the present study, the only genes previously associated with both syndromic and non-syndromic clefts in humans and mice were RYR1 and IFT172. In the latter, a missense variant, p.Asp1366Tyr (rs776240963), was detected in a patient with CLP and a bifid left renal pelvis. This SNV was predicted to be pathogenic by most in silico tools (CADD = 26.3).

Among the genes harboring LP variants, 22 were predicted to follow a dominant inheritance pattern (classified as likely or very likely dominant by the machine learning tool DOMINO) [38]. Of the remaining genes, seven were predicted to follow an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, while three could be consistent with either dominant or recessive inheritance (Table 2).

Analysis of protein structures using the UniProt knowledgebase (https://www.uniprot.org/, accessed on 1 July 2025) revealed that 11 out of 26 missense variants were located within functional domains or domain superfamilies of the corresponding proteins (Table S3).

2.2. Results of Common Variants Analysis—GWAS Data

Analysis of 2151 common SNVs located within the 30 gene loci identified in the present study revealed four variants significantly associated with the risk of ns-CL/P (Table 3, Figures S1–S4). The strongest signal was observed for an intronic variant in the NXN gene (rs8081951), with a ptrend-value of 2.52 × 10−4 (odds ratio: OR = 1.62). Three additional variants were: an intergenic SNV (rs28564876) located ~81.8 kb upstream of MAML1 (ptrend = 9.34 × 10−4), synonymous variant in EXT1 (ptrend = 9.56 × 10−4), and an intergenic SNV upstream of TP53BP2 (ptrend = 1.16 × 10−3). The allelic ORs for these variants ranged from 0.70 to 1.80. All four variants remained statistically significant after Bonferroni correction for the number of tested genes (0.05/30), but none reached the stricter threshold accounting for the total number of tested SNVs (ptrend < 2.32 × 10−5). Analysis of the remaining SNVs within these gene loci did not show any additional variants significantly associated with ns-CL/P risk. However, the linkage disequilibrium (LD) block encompassing the TP53BP2 gene is relatively broad, consistent with a region of low recombination, and contains several variants that approach statistical significance. This LD structure suggests that the observed signal may reflect a true association driven by multiple correlated SNVs within the locus.

Table 3.

Associations of common variants within loci for genes carrying rare likely pathogenic variants identified in ns-CL/P patients.

2.3. Enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) Categories

Over representation analysis (ORA) identified 24 GO biological process categories significantly enriched among the tested genes (padj < 0.05). The top five enriched terms were “tissue morphogenesis”, “embryonic morphogenesis”, “animal organ morphogenesis”, “morphogenesis of an epithelium”, and “circulatory system development” (all padj-values ≤ 8.52 × 10−6; Table 4). No GO molecular function categories were enriched among analyzed cleft genes (Table S4). Although the majority of genes were annotated with broad molecular function terms such as “protein binding”, these categories were not statistically enriched in ORA due to their high prevalence in the genome-wide background. A graphical overview of GO Slim terms and the hierarchical relationships of significantly enriched biological process categories is provided in Figures S5 and S6.

Table 4.

Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process enrichment analysis of ns-CL/P associated genes.

3. Discussion

It is well established that genetic factors, including both common and rare nucleotide variants, play a significant role in the complex etiology of ns-CL/P. In this study, we applied WES combined with GWAS data to investigate genetic determinants of this common craniofacial anomaly in a cohort from the genetically homogenous Polish population. Through a stringent, multistage filtering strategy, we identified 31 novel and ultra-rare LP coding and splicing variants in 30 genes that may potentially be involved in the pathogenesis of ns-CL/P. While the contribution of these variants remains to be functionally validated, our findings suggest the involvement of both previously implicated genes and novel candidates, supporting the heterogeneity and polygenic nature of this condition.

One of the most noteworthy observations from our study was the detection of three DNVs in patients with ns-CLP: a highly deleterious missense variant in FOXA2 and two nonsense mutations in MAML1 and ZNF319. All three genes are predicted to act in an autosomal dominant manner and have not previously been associated with either syndromic or non-syndromic forms of clefting. FOXA2 encodes a transcription factor essential for early embryogenesis and endodermal organogenesis [40,41]; its interaction with the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) pathway provides a plausible link to craniofacial development [42,43,44]. While no defined human syndrome has yet been attributed to FOXA2 mutations in OMIM, variants in this gene have been associated with hypopituitarism, hyperinsulinism, craniofacial abnormalities, and midline defects, including a reported case of paramedian cleft lip and palate in a patient carrying a ~5.4 Mb deletion at 20p11.2 encompassing 35 genes, among them FOXA2 [45,46]. MAML1 functions as a transcriptional coactivator in Notch and other pathways, including p53, β-catenin, and Shh signaling, all of which are essential for craniofacial morphogenesis and palatogenesis [47,48,49,50,51]. In addition, Maml1 has been shown to enhance Runx2-dependent osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation in mice, a process relevant to secondary palatal ossification rather than primary lip fusion [52]. Thus, while the precise mechanism by which MAML1 variants contribute to cleft lip and palate remains uncertain, its involvement in multiple signaling pathways critical for craniofacial development makes it a plausible candidate gene. ZNF319, although less well characterized, has been implicated in transcriptional regulation and Wnt signaling, another pathway central to craniofacial morphogenesis [43,44]. This zinc finger transcription factor has been proposed to act as a tumor suppressor regulating cell cycle progression and proliferation [53].

DNVs are an important category of genetic variation that may contribute to multifactorial disorders, including ns-CL/P [54]. Since these variants are not inherited and therefore not subject to purifying selection, they have a greater probability of exerting strong functional effects [55]. Evidence supporting a contribution of DNVs to ns-CL/P comes from trio-based sequencing studies. In the first large-scale WGS study of orofacial clefts, Bishop et al. reported a significant enrichment of loss-of-function DNVs in genes highly expressed in craniofacial tissues across multi-ethnic case–parent trios [26]. More recently, Ishorst et al. showed that integrating DNV detection with polygenic risk score analysis is a powerful approach to gene discovery in ns-CL/P, highlighting recurrent DNVs in MDN1 and PAXIP1 [27]. In line with these findings, previous studies in the Polish population have identified LP DNVs in CTNND1, NOTCH2, FGFR1, and KMT2D in patients with non-syndromic clefts [21]. Together, these observations suggest that DNVs represent one of several mechanisms contributing to ns-CL/P susceptibility. In our cohort, three LP DNVs (FOXA2, MAML1, ZNF319) emerged as preliminary candidate variants; however, each was observed only once and is classified as likely pathogenic or variants of uncertain significance under ACMG criteria [56] (Table 2). Robust gene–disease associations require recurrent independent findings across multiple studies. Therefore, the DNVs identified here should be considered exploratory, and validation in larger cohorts with functional follow-up will be essential to clarify their pathogenic relevance.

Another noteworthy finding was a missense variant in the VWA8 gene. The p.Arg668Gln substitution (rs138075452) has previously been reported as likely pathogenic for ns-CL/P and is cataloged in ClinVar [28]. Aylward et al. identified five candidate variants in VWA8, each present in a single family, but none showed complete segregation with ns-CL/P [28]. The recurrence of the VWA8 p.Arg668Gln variant in our cohort, together with its inheritance from an affected father, supports its potential role as a risk factor. In addition, we identified two other LP variants transmitted from affected parents, including GDF7 p.Leu361Phe and FAT1 p.Ile895AspfsTer2. Although these SNVs, classified as variants of uncertain significance, occur in genes not previously linked to orofacial clefts, their inheritance from affected parents is of particular interest. Additional lines of evidence, such as epigenetic and expression data, provide supportive but not conclusive indications of a possible role of these candidate genes in craniofacial development. Importantly, differential methylation of FAT1 has been implicated in ns-CL/P [7], pointing to epigenetic dysregulation of this gene as one of the potential disease mechanisms. These results align with emerging evidence that epigenetic regulation of craniofacial genes, including altered methylation patterns, may contribute to ns-CL/P risk. FAT1 encodes an atypical cadherin that participates in the planar cell polarity pathway, known to play a role in craniofacial morphogenesis [57]. Moreover, FAT1 can activate multiple signaling cascades, such as Wnt/β-catenin, Hippo, and MAPK/ERK, which regulate essential cellular processes such as proliferation, migration, and invasion [58]. Support for GDF7 involvement comes from mouse studies, where transcriptomic analyses of upper lip and primary palate development revealed Gdf7 expression in craniofacial structures [59].

The remaining novel and ultra-rare LP variants identified in this study were inherited from healthy parents. Nine of them occurred in genes previously associated, or suspected to be associated with ns-CL/P risk based on human genetic studies (CTNNA1, EFNB2, HIF1A, LAMA5, IFT172, MYH3, RYR1 and TENM4) [22,29,30,31,32,33,34,37], further supporting their candidacy for this anomaly. Notably, MYH3 has also been implicated in syndromic forms of clefting (OMIM #178110, #618469), while both RYR1 and IFT172 have been linked to syndromic and non-syndromic clefts in humans and mice. Among these, IFT172 appears particularly noteworthy, as we identified a missense variant, p.Asp1366Tyr (rs776240963), located in the tetratricopeptide-like helical domain of the protein, in a patient with CLP and a bifid left renal pelvis but no other congenital malformations. IFT172 encodes a key component of the intraflagellar transport complex, which is critical for cilia formation and maintenance [60]. Defects in this process underlie a group of disorders known as ciliopathies, many of which present with overlapping craniofacial, renal, and skeletal anomalies [61,62]. Indeed, pathogenic IFT172 variants have been reported in syndromic conditions such as Mainzer–Saldino and Bardet–Biedl syndromes, which can include clefting and renal malformations as part of the clinical spectrum [62]. Mouse knockout studies further confirm its role, as Ift172-deficient embryos display a broad spectrum of developmental abnormalities, including craniofacial defects (abnormal craniofacial morphology and cleft secondary palate) and kidney malformations. Overall, our findings provide additional evidence that disruption of ciliary function, through genes such as IFT172, may represent a shared developmental mechanism underlying both craniofacial and renal anomalies.

Among other variants inherited from unaffected parents were those in genes previously associated with syndromic forms of clefting in humans (ATN1), genes whose involvement in clefting has been demonstrated in knockout mouse models (EXT1, HAND1, KRT17, MEN1, NCOR2, ROBO1, SLC32A1, and TP53BP2), as well as genes included in both categories (NXN and RPGRIP1L). In this group, variants were also detected in genes for which, to our knowledge, no direct association with orofacial clefts has been reported so far. These include AGO1, ARID1A, ATP1A1, HOXB3 and LRP5. Notably, in AGO1, which encodes an Argonaute protein essential for miRNA processing and RNA-mediated gene silencing [63], an amino acid substitution p.Ser608Phe (rs1353927503) was identified within the functional PIWI domain. Recently, pathogenic variants and gross deletions involving AGO1 have been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders in humans, including autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, intellectual disability, and dysmorphic facial features [64]. Some affected individuals also presented with high-arched palate and dental crowding [65]. Given that microRNAs play a critical role in regulating gene expression during craniofacial development, and that SNVs in miRNA genes have been implicated in ns-CL/P risk, AGO1 emerges as a strong novel candidate for clefting. Other noteworthy findings include LRP5, which encodes a component of the Wnt-Fzd-LRP5-LRP6 complex that activates β-catenin signaling [66], and HOXB3, a sequence-specific transcription factor that provides positional identity along the anterior–posterior axis during development [67]. In a regulatory network analysis of cleft genes, Li et al. reported HOXB3 enrichment in pathways related to positive regulation of cell division [68]. Notably during upper lip formation the lateral nasal process undergoes a peak of cell proliferation, and perturbations in growth at this critical stage may impair fusion [69]. Experimental studies have also demonstrated that Hoxb3 directly regulates Jag1 expression in the pharyngeal epithelium, thereby affecting neural crest cell migration and pharyngeal arch morphogenesis, further supporting a possible role in craniofacial development [70]. While these observations suggest a potential indirect involvement of HOX3B, direct evidence of its role in craniofacial regions relevant to lip development is lacking, and its contribution to CLP pathogenesis therefore remains speculative.

Inheritance of LP variants from clinically unaffected parents, as observed for the majority of variants in this study, suggests incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Such variants may also act as genetic modifiers that influence individual risk, supporting the multifactorial model of ns-CL/P etiology in which multiple genetic variants, in combination with epigenetic and environmental exposures, collectively determine the likelihood of disease manifestation [71]. Environmental factors implicated in ns-CL/P include both unmodifiable factors (e.g., ancestry, sex, family history) and modifiable maternal exposures during the periconceptional period [72]. Maternal health and lifestyle factors, such as tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, nutritional deficiencies, obesity, febrile maternal illness, and certain medications, may alter the intrauterine environment and potentiate the phenotypic effects of inherited variants [73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. Environmental toxicants, including disinfection byproducts or nitrates in drinking water [80], have also been linked to an increased risk in epidemiological studies. Within this framework, LP variants may not be restricted to affected individuals. They can also be present in unaffected family members, highlighting the complex gene-gene and gene-environment interactions underlying cleft pathogenesis. Unfortunately, our study did not account for environmental exposures.

To further contextualize our findings, we analyzed common variants within the 30 gene loci harboring rare LP variants. At the gene level, four SNVs showed nominal associations with ns-CL/P, including intronic and synonymous variants in NXN and EXT1, as well as intergenic variants in the MAML1 and TP53BP2 loci. These results should be interpreted with caution, as none of these associations remained statistically significant after correction for multiple testing across the total number of variants analyzed. Nevertheless, they support the candidacy of these four genes and suggest that both common and rare variants within them may contribute to ns-CL/P risk. The strongest signal was observed for an intronic variant in NXN, which encodes a redox-dependent negative regulator of the Wnt signaling pathway [81]. Notably, the detection of a rare LP in the thioredoxin domain of the NXN protein (p.Lys168Thr) in our cohort provides converging lines of evidence suggesting a potential role of this gene in ns-CL/P pathogenesis. Validation of these associations and clarification of their biological relevance will require larger, well-powered studies conducted across diverse populations.

Finally, we performed over-representation analysis of GO categories to better understand the biological significance of the identified genes. This analysis revealed several biological process terms that were significantly enriched, with the strongest signals observed for categories broadly related to developmental processes. The top enriched categories included tissue morphogenesis, embryonic morphogenesis, animal organ morphogenesis, morphogenesis of an epithelium, and circulatory system development. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have linked cleft-associated genes to key developmental processes and signaling pathways [23,30]. Nevertheless, it should be noted that our analysis excluded the 423 cleft candidate genes examined in our previous study [21]. Thus, the enrichment patterns presented here should be interpreted as complementary to, rather than directly comparable with, those reported for cleft genes in earlier analyses.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although WES is effective for detecting coding variants, it does not capture non-coding regions, structural rearrangements, or copy number variants that are known to contribute to orofacial clefting [82,83]. Second, the identified variants were assessed only through in silico prediction tools, and no functional assays were carried out to confirm their pathogenicity. Third, our findings were not replicated in an independent cohort from a different population, which limits their generalizability. Although the genetic homogeneity of the Polish population may have facilitated rare variant discovery, replication in larger and ethnically diverse cohorts or through cross-population meta-analyses will be required to confirm the broader relevance of the identified variants. Fourth, parental data were restricted to targeted resequencing of selected variants for segregation analysis, rather than trio-based WES, which precluded comprehensive detection of DNVs and Mendelian errors—an approach recognized to be effective for identifying indels [83]. Fifth, our filtering and prioritization strategy may not fully reflect the true biological impact of variants and could have resulted in the omission of clinically relevant changes. Sixth, the statistical power of the GWAS-based analysis was limited, as the applied multiple testing correction considered only the number of tested genes rather than the total number of SNVs, thereby increasing the risk of false-positive findings. Finally, the overall sample size of our study was relatively small, which reduced the power to detect rare variants.

In addition, the present study analyzed ns-CL and ns-CLP as a combined group, in line with previous genetic investigations, to maximize power given the limited sample size. We acknowledge, however, that cleft lip only and cleft lip with palate are clinically and embryologically distinct subtypes that may involve partially different genetic mechanisms [2,3]. Epidemiological studies indicate that ns-CL and ns-CLP differ in sex distribution, laterality, and recurrence risk, while embryological evidence suggests that lip and palate closure may involve distinct morphogenetic processes and signaling pathways [5,43,84]. Notably, most rare variants identified in our cohort occurred in ns-CLP patients, with only four variants detected in ns-CL cases. Larger studies will be required to clarify whether the genetic risk factors observed here are specific to ns-CLP or also extend to ns-CL.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Workflow of the Study

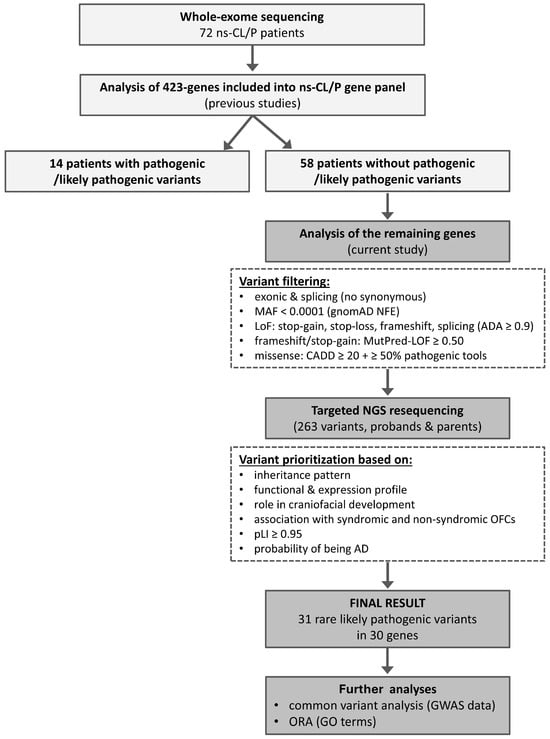

WES was performed for 72 patients with ns-CL/P. Parental DNA samples were available for all patients and were used for targeted NGS resequencing of selected variants to assess segregation, but not for trio-based WES. In the first step, variants were analyzed exclusively in 423 genes included in a previously established hypothesis-driven ns-CL/P multigene panel. Importantly, in our earlier publication, this panel was interrogated in two ways: the selected 423 genes’ coding exons and exon–intron boundaries were screened using either an NGS-based multigene panel (in 56 patients) or WES (in 72 patients), although only variants within this targeted gene set were analyzed and reported [21]. Briefly, among the 72 patients tested by WES, rare P/LP variants were identified in 14 individuals, whereas the remaining 58 carried no such variants. In the present study, we focused on these 58 patients and extended the analysis to all other coding genes captured by WES. After variant filtering and prioritization, 263 SNVs were confirmed and tested for segregation in probands and their parents by targeted NGS resequencing. Further prioritization yielded a final dataset of 31 LP variants in 30 genes. In the next stage, common variants in genes carrying rare LP variants were examined using data from our previously published GWAS of ns-CL/P [39,85]. This GWAS was performed in a completely independent Polish cohort comprising 269 ns-CL/P patients and 569 controls, genotyped using the HumanOmniExpressExome-8 v1 array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Finally, ORA was conducted for Gene Ontology categories (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow of variant detection and prioritization in the current study.

The detailed selection and characterization of the 423 genes included in the ns-CL/P multigene panel have been described previously [21,86]. In brief, the panel encompassed: established ns-CL/P candidate genes, genes associated with syndromic clefts, genes whose knockout in mice results in orofacial clefts, genes encoding proteins involved in signaling pathways critical for craniofacial development, and genes with high expression in embryonic craniofacial tissues (Table S5).

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed for 72 patients with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate (ns-CL/P). Variants in 423 genes included in a previously published ns-CL/P multigene panel were analyzed first, identifying pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants in 14 patients. The remaining 58 patients underwent extended analysis of all other coding genes captured by WES. After variant filtering, 263 single-nucleotide variants were confirmed and tested for segregation in probands and their parents using targeted resequencing. Subsequent prioritization yielded 31 LP variants in 30 genes. In the next stage, common variants in genes carrying rare LP variants were examined using data from our previously published Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS) of ns-CL/P, followed by overrepresentation enrichment analysis (ORA). Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; CADD, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; GO, gene ontology; LoF, loss of function; MAF, minor allele frequency; NFE, European non-Finnish; pLI, probability of being loss-of-function intolerant.

4.2. Study Population

The study cohort comprised 56 unrelated patients and one sibling pair (total n = 58) diagnosed with ns-CL/P, aged 1–15 years. All participants were enrolled in the Comprehensive Therapy Programme for Craniofacial Anomalies at Poznan University of Medical Sciences. The cohort consisted of 48 individuals with ns-CLP (82.8%), and 10 individuals had ns-CL (17.2%). The overall male-to-female ratio was 1.64:1 (Table 5). Minor associated anomalies were observed in two patients (3.5%), specifically kidney malformations such as a bifid left renal pelvis or horseshoe kidney. These patients were retained in the cohort, as no known syndromes were diagnosed after a detailed review of their medical records. A positive family history of ns-CL/P was reported in 19 cases (32.8%).

Table 5.

Clinical characteristics of patients with ns-CL/P.

Peripheral blood samples were collected from patients and their parents. All participants were Caucasians of Polish origin. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes using the salting-out method. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland (approval number 1115/18, approval date: 7 November 2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and from the parents or legal guardians of underage patients, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [87].

4.3. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES)

Library preparation for WES was performed using the TruSeq DNA Exome kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was conducted on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform with paired-end reads (2 × 100 bp). Raw data were processed following a previously described pipeline [21,84]. The mean on-target sequencing depth was 95.6x, with an average of 97.6% (range: 94.6–99.2%) of target bases covered at ≥20x. Raw sequencing data were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ format using bcl2fastq (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). After adapter trimming and removal of low-quality reads, sequences were aligned to the GRCh38/hg38 reference genome using the Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/, accessed on 1 February 2017). The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/, accessed on 1 February 2017) was used for calling SNVs and short insertions/deletions (indels). Variants were annotated with functional information, in silico pathogenicity predictions, population allele frequency (gnomAD European non-Finnish population, http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/, accessed on 1 June 2025), and clinical significance based on ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/, accessed on 1 June 2025), the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk, accessed on 1 June 2025), and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM, https://omim.org/, accessed on 1 June 2025). Phenotypic information from knockout mouse models was retrieved from the Mouse Genome Informatics database (https://www.informatics.jax.org/, accessed on 1 June 2025).

Predicted variant effects were evaluated using 22 in silico tools. These included individual predictors: SIFT, SIFT4G, PolyPhen-2_HDIV, PolyPhen-2_HVAR, MutationTaster, MutationAssessor, PROVEAN, M-CAP, MutPred2, PrimateAI, DEOGEN2, ClinPred, LIST-S2, ESM1b, AlphaMissense, fathmm-XF, as well as meta-predictors: MetaSVM, MetaLR, MetaRNN, REVEL, BayesDel_addAF, BayesDel_noAF. All scores were retrieved from the dbNSFP database (https://www.dbnsfp.org/home, accessed on 1 July 2025). Additionally, CADD, Deleterious Annotation of genetic variants using Neural Networks (DANN), and ADA scores were used to assess missense and potentially splice-altering variants. The pathogenicity and functional impact of frameshift and stop-gain variants were predicted using the MutPred-LOF application (http://mutpred.mutdb.org/, accessed on 1 July 2025). Finally, gene-level metrics, including the probability of being loss-of-function intolerant (pLI) and the likelihood of autosomal dominant disease association, were obtained from gnomAD v4.1.0 and the DOMINO tool (https://domino.iob.ch/index.php, accessed on 1 July 2025).

4.4. Variant Selection and Prioritizing

Only exonic and splicing variants (excluding synonymous substitutions) with MAF < 0.0001 in the gnomAD European non-Finnish population were considered. Likely gene-disrupting variants included stop-gain, stop-loss, frameshift, splicing variants with an ADA score ≥ 0.9, as well as missense variants with a CADD score ≥ 20 that were classified as pathogenic by at least half of the applied in silico prediction tools. For frameshift and stop-gain variants, a MutPred-LOF score ≥ 0.50 was used as the threshold for likely pathogenicity.

After confirmation and segregation analysis, the final set of variants was selected based on inheritance patterns and the functional and expression profiles of the corresponding genes. Priority was given to variants identified in genes previously associated with non-syndromic or syndromic orofacial clefts, genes with a documented role in lip and palate development, and genes with pLI ≥ 0.95 and classified as likely and very likely dominant.

4.5. Confirmation and Segregation Analyses

Rare LP variants identified in the initial filtering step were validated and tested for co-segregation by targeted NGS resequencing in probands and their parents. Amplicon-based deep sequencing was carried out using the Nextera XT Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), followed by paired-end sequencing (2 × 100 bp) on an Illumina platform.

4.6. Common Variants Analysis—GWAS Data

Data on common SNVs within genes identified in the current study (n = 30) were extracted from our previously published GWAS of ns-CL/P in the Polish population [83,84]. Importantly, the GWAS was conducted in an independent ns-CL/P patient cohort, distinct from the WES cohort analyzed here; a detailed description of the patient and control groups is provided in the original publications. For each gene locus (gene ± 100 kb), associations of common SNVs with MAF ≥ 0.05 were tested with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. The strength of association was expressed as allelic OR. To correct for multiple testing, Bonferroni correction was applied, and ptrend-values < 1.67 × 10−3 (0.05/30 genes) were considered statistically significant. Regional association plots for tested SNVs were generated using LocusZoom v1.1 tool (http://locuszoom.org/, accessed on 1 July 2025).

4.7. Over Representation Analysis (ORA)

For genes harboring rare LP variants, ORA of GO terms was performed using the WebGestalt tool (WEB-based Gene SeT AnaLysis Toolkit, http://www.webgestalt.org/, accessed on 1 June 2025), with all protein-coding genes in the genome as the reference set. GO categories, including biological process and molecular function, were considered significantly enriched at a Bonferroni-adjusted padj-value < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we report novel and rare LP variants that may contribute to ns-CL/P, including three DNVs in genes not previously associated with cleft risk. By integrating evidence from both rare and common variant analyses, our results support the multifactorial etiology of ns-CL/P, in which genetic and environmental factors may interact. These findings expand the list of candidate genes and suggest new directions that may explain the molecular basis of orofacial clefting. Future studies in larger patient cohorts from diverse populations and functional validation will be crucial to confirm our findings and to fully characterize the genetic landscape of ns-CL/P.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262412111/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., J.D., A.B., K.K. and A.M.; methodology, J.D. and A.M.; validation, J.D. and A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, B.B., A.B., K.K. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M.; funding acquisition, B.B. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Comprehensive Therapy Program for Craniofacial Anomalies (RPWP.07.02.02-30-0037/16) was supported by European Social Fund and Wielkopolska Voivodeship (Regional Operational Programme for Wielkopolskie Voivodeship 2014-2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [87] and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poland (approval number 1115/18) approval date on 7 November 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants or their legal guardians.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified datasets generated through this study can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the patient and her family for their participation and cooperation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Autosomal Dominant |

| ADA | Adaptive Boosting |

| CADD | Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion |

| DANN | Deleterious Annotation of Genetic Variants Using Neural Networks |

| DNV | De Novo variant |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GWAS | Genome-Wide Association Study |

| LD | Linkage Disequilibrium |

| LoF | Loss of Function |

| MAF | Minor Allele Frequency |

| NFE | European non-Finnish |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| ns-CL | Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip |

| ns-CL/P | Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip with or without Cleft Palate |

| ns-CLP | Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip with Cleft Palate |

| ORA | Overrepresentation Enrichment Analysis |

| P/LP | Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic |

| pLI | Probability of Being Loss-of-Function Intolerant |

| SNV | Single Nucleotide Variants |

| VUS | Variant of Uncertain Significance |

| WES | Whole-Exome Sequencing |

| WGS | Whole-Genome Sequencing |

References

- Mossey, P.A.; Little, J.; Munger, R.G.; Dixon, M.J.; Shaw, W.C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet 2009, 374, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, G.; El Hajj, J.; Ghassibe-Sabbagh, M. Orofacial clefts embryology, classification, epidemiology, and genetics. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2021, 787, 108373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, K.U.; Ahmed, S.T.; Böhmer, A.C.; Sangani, N.B.; Varghese, S.; Klamt, J.; Schuenke, H.; Gültepe, P.; Hofmann, A.; Rubini, M.; et al. Meta-analysis Reveals Genome-Wide Significance at 15q13 for Nonsyndromic Clefting of Both the Lip and the Palate, and Functional Analyses Implicate GREM1 As a Plausible Causative Gene. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehby, G.L.; Cassell, C.H. The impact of orofacial clefts on quality of life and healthcare use and costs. Oral Dis. 2010, 16, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, M.J.; Marazita, M.L.; Beaty, T.H.; Murray, J.C. Cleft lip and palate: Understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babai, A.; Irving, M. Orofacial Clefts: Genetics of Cleft Lip and Palate. Genes 2023, 14, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvizi, L.; Ke, X.; Brito, L.A.; Seselgyte, R.; Moore, G.E.; Stanier, P.; Passos-Bueno, M.R. Differential methylation is associated with non-syndromic cleft lip and palate and contributes to penetrance effects. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, G.C.; Ho, K.; Davies, A.; Stergiakouli, E.; Humphries, K.; McArdle, W.; Sandy, J.; Davey Smith, G.; Lewis, S.J.; Relton, C.L. Distinct DNA methylation profiles in subtypes of orofacial cleft. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lie, R.T.; Wilcox, A.J.; Saugstad, O.D.; Taylor, J.A. A comparison of DNA methylation in newborn blood samples from infants with and without orofacial clefts. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.D.; Huang, Y.J.; Zhang, H.F.; Tang, W.; Zhang, M.F. Study on DNA methylation profiles in non-syndromic cleft lip/palate based on bioinformatics. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 2019, 28, 57–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Im, H.; Song, Y.; Kim, J.K.; Park, D.K.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, H.; Shin, J.O. Molecular Regulation of Palatogenesis and Clefting: An Integrative Analysis of Genetic, Epigenetic Networks, and Environmental Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Meng, T.; Jia, Z.; Zhu, G.; Shi, B. Single nucleotide polymorphism associated with nonsyndromic cleft palate influences the processing of miR-140. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2010, 152A, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stüssel, L.G.; Hollstein, R.; Laugsch, M.; Hochfeld, L.M.; Welzenbach, J.; Schröder, J.; Thieme, F.; Ishorst, N.; Romero, R.O.; Weinhold, L.; et al. MiRNA-149 as a Candidate for Facial Clefting and Neural Crest Cell Migration. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosen, D.; Bille, C.; Petersen, I.; Skytthe, A.; Hjelmborg, J.; Pedersen, J.K.; Murray, J.C.; Christensen, K. Risk of oral clefts in twins. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivertsen, A.; Wilcox, A.J.; Skjaerven, R.; Vindenes, H.A.; Abyholm, F.; Harville, E.; Lie, R.T. Familial risk of oral clefts by morphological type and severity: Population based cohort study of first degree relatives. BMJ 2008, 336, 432–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.; Bryan, E. Congenital anomalies in twins. Semin. Perinatol. 1986, 10, 50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimov, F.; Marazita, M.L.; Visel, A.; Cooper, M.E.; Hitchler, M.J.; Rubini, M.; Domann, F.E.; Govil, M.; Christensen, K.; Bille, C.; et al. Disruption of an AP-2alpha binding site in an IRF6 enhancer is associated with cleft lip. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, S.; Ludwig, K.U.; Reutter, H.; Herms, S.; Steffens, M.; Rubini, M.; Baluardo, C.; Ferrian, M.; Almeida de Assis, N.; Alblas, M.A.; et al. Key susceptibility locus for nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate on chromosome 8q24. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostowska, A.; Hozyasz, K.K.; Wojcicki, P.; Biedziak, B.; Paradowska, P.; Jagodzinski, P.P. Association between genetic variants of reported candidate genes or regions and risk of cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the polish population. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010, 88, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotoye, W.; Mossey, P.A.; Hetmanski, J.B.; Gowans, L.J.J.; Eshete, M.A.; Adeyemo, W.L.; Alade, A.; Zeng, E.; Adamson, O.; Naicker, T.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals de-novo mutations associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip/palate. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, J.; Biedziak, B.; Szponar-Żurowska, A.; Budner, M.; Jagodziński, P.P.; Płoski, R.; Mostowska, A. Identification of novel susceptibility genes for non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate using NGS-based multigene panel testing. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2022, 297, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Yue, J.; Xue, L.; Xu, Y.; Ding, Q.; Xiao, W. Using whole exome sequencing to identify susceptibility genes associated with nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 298, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, K.; Newbury, D.F.; Kini, U. Analysis of exome data in a UK cohort of 603 patients with syndromic orofacial clefting identifies causal molecular pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Y.; Chang, J.W.; Zhong, N.N.; Huang, Z.; Yue, H.; Cao, H.; Wu, Z.; He, M.; Bian, Z. Exome analyses unravel the genetic architecture of Mendelian dominant nonsyndromic orofacial clefts. Genomics 2025, 117, 111039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.L.; Cox, T.C.; Moreno Uribe, L.M.; Zhu, Y.; Richter, C.T.; Nidey, N.; Standley, J.M.; Deng, M.; Blue, E.; Chong, J.X.; et al. Mutations in the Epithelial Cadherin-p120-Catenin Complex Cause Mendelian Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip with or without Cleft Palate. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 1143–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.R.; Diaz Perez, K.K.; Sun, M.; Ho, S.; Chopra, P.; Mukhopadhyay, N.; Hetmanski, J.B.; Taub, M.A.; Moreno-Uribe, L.M.; Valencia-Ramirez, L.C.; et al. Genome-wide Enrichment of De Novo Coding Mutations in Orofacial Cleft Trios. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 107, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishorst, N.; Henschel, L.; Thieme, F.; Drichel, D.; Sivalingam, S.; Mehrem, S.L.; Fechtner, A.C.; Fazaal, J.; Welzenbach, J.; Heimbach, A.; et al. Identification of de novo variants in nonsyndromic cleft lip with/without cleft palate patients with low polygenic risk scores. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, A.; Cai, Y.; Lee, A.; Blue, E.; Rabinowitz, D.; Haddad, J., Jr.; University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics. Using Whole Exome Sequencing to Identify Candidate Genes with Rare Variants In Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip and Palate. Genet. Epidemiol. 2016, 40, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, H. Pathway analysis identified a significant association between cell-cell adherens junctions-related genes and non-syndromic cleft lip/palate in 895 Asian case-parent trios. Arch. Oral Biol. 2022, 136, 105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, T.; Yan, F.; Liu, A.; Dai, Y.; Iwaya, C.; Curtis, S.W.; Leslie, E.J.; Simon, L.M.; Jia, P.; Chen, X.; et al. Investigating gene functions and single-cell expression profiles of de novo variants in orofacial clefts. HGG Adv. 2024, 5, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Ma, L.; Kan, S.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhu, G.; Fan, L.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; et al. Association Study of Genetic Variants in Autophagy Pathway and Risk of Non-syndromic Cleft Lip With or Without Cleft Palate. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Cao, H.; Zuo, Y.; He, M. Functional Analysis of IFT172 Mutations in Families with Non-syndromic Cleft Lip with or without Palate. J. Oral Sci. Res. 2025, 41, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengelly, R.J.; Arias, L.; Martínez, J.; Upstill-Goddard, R.; Seaby, E.G.; Gibson, J.; Ennis, S.; Collins, A.; Briceño, I. Deleterious coding variants in multi-case families with non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate phenotypes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.D.; Lin, Y.S.; Shi, B.; Jia, Z.L. Identifying New Susceptibility Genes of Non-Syndromic Orofacial Cleft Based on Syndromes Accompanied With Craniosynostosis. Cleft. Palate Craniofac. J. 2025, 22, 10556656251313842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKie, A.B.; Alsaedi, A.; Vogt, J.; Stuurman, K.E.; Weiss, M.M.; Shakeel, H.; Tee, L.; Morgan, N.V.; Nikkels, P.G.; van Haaften, G.; et al. Germline mutations in RYR1 are associated with foetal akinesia deformation sequence/lethal multiple pterygium syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharucha-Goebel, D.X.; Santi, M.; Medne, L.; Zukosky, K.; Dastgir, J.; Shieh, P.B.; Winder, T.; Tennekoon, G.; Finkel, R.S.; Dowling, J.J.; et al. Severe congenital RYR1-associated myopathy: The expanding clinicopathologic and genetic spectrum. Neurology 2013, 80, 1584–1589, Erratum in Neurology 2013, 80, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladayo, A.; Gowans, L.J.J.; Awotoye, W.; Alade, A.; Busch, T.; Naicker, T.; Eshete, M.A.; Adeyemo, W.L.; Hetmanski, J.B.; Zeng, E.; et al. Clinically actionable secondary findings in 130 triads from sub-Saharan African families with non-syndromic orofacial clefts. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinodoz, M.; Royer-Bertrand, B.; Cisarova, K.; Di Gioia, S.A.; Superti-Furga, A.; Rivolta, C. DOMINO: Using Machine Learning to Predict Genes Associated with Dominant Disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 101, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostowska, A.; Gaczkowska, A.; Żukowski, K.; Ludwig, K.U.; Hozyasz, K.K.; Wójcicki, P.; Mangold, E.; Böhmer, A.C.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Knapp, M.; et al. Common variants in DLG1 locus are associated with non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Clin. Genet. 2018, 93, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.L.; Wierda, A.; Wong, D.; Stevens, K.A.; Cascio, S.; Rossant, J.; Zaret, K.S. The formation and maintenance of the definitive endoderm lineage in the mouse: Involvement of HNF3/forkhead proteins. Development 1993, 119, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, D.C.; Ruiz i Altaba, A.; Chen, W.S.; Hoodless, P.; Prezioso, V.R.; Jessell, T.M.; Darnell, J.E., Jr. The winged-helix transcription factor HNF-3 beta is required for notochord development in the mouse embryo. Cell 1994, 78, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatakis, Y.E.; Lin, W.; Metzakopian, E.; Ferri, A.L.; Yan, C.H.; Sasaki, H.; Whisett, J.; Ang, S.L. Foxa1 and Foxa2 positively and negatively regulate Shh signalling to specify ventral midbrain progenitor identity. Mech. Dev. 2011, 128, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, N.L.; Dixon, M.J. Revisiting the embryogenesis of lip and palate development. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 1306–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, H.J.; Kim, J.W.; Won, H.S.; Shin, J.O. Gene Regulatory Networks and Signaling Pathways in Palatogenesis and Cleft Palate: A Comprehensive Review. Cells 2023, 12, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.G.; Wetherbee, J.J.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Hersh, J.H. 20p11 deletion in a female child with panhypopituitarism, cleft lip and palate, dysmorphic facial features, global developmental delay and seizure disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2011, 155A, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, D.; Vignola, M.L.; Gualtieri, A.; Scagliotti, V.; McNamara, P.; Peak, M.; Didi, M.; Gaston-Massuet, C.; Senniappan, S. Novel FOXA2 mutation causes Hyperinsulinism, Hypopituitarism with Craniofacial and Endoderm-derived organ abnormalities. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 4315–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; McElhinny, A.S.; Cao, Y.; Gao, P.; Liu, J.; Bronson, R.; Griffin, J.D.; Wu, L. The Notch coactivator, MAML1, functions as a novel coactivator for MEF2C-mediated transcription and is required for normal myogenesis. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Guerra, M.C.; Ronchini, C.; Capobianco, A.J. Mastermind-like 1 Is a specific coactivator of beta-catenin transcription activation and is essential for colon carcinoma cell survival. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8690–8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Katzman, R.B.; Delmolino, L.M.; Bhat, I.; Zhang, Y.; Gurumurthy, C.B.; Germaniuk-Kurowska, A.; Reddi, H.V.; Solomon, A.; Zeng, M.S.; et al. The notch regulator MAML1 interacts with p53 and functions as a coactivator. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 11969–11981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Harigaya, K.; Sasaki, N.; Okamura, Y.; Kokubo, H.; Saga, Y.; Hozumi, K.; Suganami, A.; Tamura, Y.; Nagase, T.; et al. Mastermind-like 1 (MamL1) and mastermind-like 3 (MamL3) are essential for Notch signaling in vivo. Development 2011, 138, 5235–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, R.; Pelullo, M.; Zema, S.; Nardozza, F.; Checquolo, S.; Lauer, D.M.; Bufalieri, F.; Palermo, R.; Felli, M.P.; Vacca, A.; et al. Maml1 acts cooperatively with Gli proteins to regulate sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Oyama, T.; Asada, M.; Harada, D.; Ito, Y.; Inagawa, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugano, S.; Katsube, K.; Karsenty, G.; et al. MAML1 enhances the transcriptional activity of Runx2 and plays a role in bone development. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Li, M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qin, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Piao, Y.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screening uncovers ZNF319 as a novel tumor suppressor critical for breast cancer metastasis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 589, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, A. Pathogenicity of De Novo Rare Variants: Challenges and Opportunities. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e002013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K.R.; Curtis, S.W.; Paschall, J.E.; Beaty, T.H.; Butali, A.; Buxó, C.J.; Cutler, D.J.; Epstein, M.P.; Hecht, J.T.; Uribe, L.M.; et al. Distinguishing syndromic and nonsyndromic cleft palate through analysis of protein-altering de novo variants in 816 trios. medRxiv 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topczewski, J.; Dale, R.M.; Sisson, B.E. Planar cell polarity signaling in craniofacial development. Organogenesis 2011, 7, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Gong, Y.; Liang, X. Role of FAT1 in health and disease. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Si, N.; Wang, Y.; Yin, N. Transcriptomic analysis of the upper lip and primary palate development in mice. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1039850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorivodsky, M.; Mukhopadhyay, M.; Wilsch-Braeuninger, M.; Phillips, M.; Teufel, A.; Kim, C.; Malik, N.; Huttner, W.; Westphal, H. Intraflagellar transport protein 172 is essential for primary cilia formation and plays a vital role in patterning the mammalian brain. Dev. Biol. 2009, 325, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugmann, S.A.; Cordero, D.R.; Helms, J.A. Craniofacial ciliopathies: A new classification for craniofacial disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2010, 152A, 2995–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzarka, B.; Charnaya, O.; Gunay-Aygun, M. Diseases of the primary cilia: A clinical characteristics review. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025, 40, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, G. Argonaute proteins: Functional insights and emerging roles. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Y.; Qian, Q.; Li, J.; Gong, P.; Jiao, X.; Mao, X.; Xiao, B.; Long, L.; Yang, Z. De novo variants in AGO1 recapitulate a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder phenotype. Clin. Genet. 2022, 101, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, M.; Ono, S.; Kumaki, T.; Nishimura, N.; Murakami, H.; Enomoto, Y.; Naruto, T.; Ueda, H.; Kurosawa, K. Complex congenital cardiovascular anomaly in a patient with AGO1-associated disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2023, 191, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, B.T.; He, X. Frizzled and LRP5/6 receptors for Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a007880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, K.A.; Wellik, D.M. Hox genes in development and beyond. Development 2023, 150, dev192476, Correction in Development 2024, 151, dev202770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Qin, G.; Suzuki, A.; Gajera, M.; Iwata, J.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z. Network-based identification of critical regulators as putative drivers of human cleft lip. BMC Med. Genom. 2019, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, S.H.; Henry, R.R.; Yuan, Q.; Mulliken, J.B.; Stal, S.; Finnell, R.H.; Hecht, J.T. Folate pathway and nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2011, 91, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; So, K.K.H.; Tong, K.K.; Sae-Pang, J.J.; Wang, L.; Tsang, S.L.; Chan, W.Y.; Wong, E.Y.M.; Sham, M.H. Hoxb3 Regulates Jag1 Expression in Pharyngeal Epithelium and Affects Interaction with Neural Crest Cells. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 612230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Du, F.; Long, X.; Huang, J. Genetic Inheritance Models of Non-Syndromic Cleft Lip with or without Palate: From Monogenic to Polygenic. Genes 2023, 14, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inchingolo, A.M.; Fatone, M.C.; Malcangi, G.; Avantario, P.; Piras, F.; Patano, A.; Di Pede, C.; Netti, A.; Ciocia, A.M.; De Ruvo, E.; et al. Modifiable Risk Factors of Non-Syndromic Orofacial Clefts: A Systematic Review. Children 2022, 9, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbagh, H.J.; Hassan, M.H.; Innes, N.P.; Elkodary, H.M.; Little, J.; Mossey, P.A. Passive smoking in the etiology of non-syndromic orofacial clefts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zou, S. Maternal alcohol consumption and oral clefts: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 57, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Regil, L.M.; Pena-Rosas, J.P.; Fernandez-Gaxiola, A.C.; Rayco-Solon, P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 12, CD007950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, S.R.; Watkins, S.M.; Salemi, J.L.; Rutkowski, R.; Tanner, J.P.; Correia, J.A.; Kirby, R.S. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and risk of selected birth defects: Evidence of a dose-response relationship. Paediatr. Peri. Epidemiol. 2013, 27, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, L.; Banyai, D.; Nemes, B.; Nagy, K.; Acs, N.; Banhidy, F.; Rózsa, N. Maternal-related factors in the origin of isolated cleft palate-A population-based case-control study. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2020, 23, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, S.L.; Shaw, G.M. Maternal corticosteroid use and risk of selected congenital anomalies. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999, 86, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, K.F.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Straub, L.; Gray, K.J.; Zhu, Y.; Patorno, E.; Desai, R.J.; Mogun, H.; Bateman, B.T. Association of Maternal First-Trimester Ondansetron Use with Cardiac Malformations and Oral Clefts in Offspring. JAMA 2018, 320, 2429–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, M.; Palmieri, A.; Carinci, F.; Scapoli, L. Non-syndromic Cleft Palate: An Overview on Human Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 592271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idelfonso-García, O.G.; Alarcón-Sánchez, B.R.; Vásquez-Garzón, V.R.; Baltiérrez-Hoyos, R.; Villa-Treviño, S.; Muriel, P.; Serrano, H.; Pérez-Carreón, J.I.; Arellanes-Robledo, J. Is Nucleoredoxin a Master Regulator of Cellular Redox Homeostasis? Its Implication in Different Pathologies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapoli, L.; Carinci, F.; Palmieri, A.; Cura, F.; Baj, A.; Beltramini, G.; Docimo, R.; Martinelli, M. Copy number variation analysis of twin pairs discordant for cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 2058738419855873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieger, H.K.; Weinhold, L.; Schmidt, A.; Holtgrewe, M.; Juranek, S.A.; Siewert, A.; Scheer, A.B.; Thieme, F.; Mangold, E.; Ishorst, N.; et al. Prioritization of non-coding elements involved in non-syndromic cleft lip with/without cleft palate through genome-wide analysis of de novo mutations. HGG Adv. 2022, 4, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.J.; Marazita, M.L. Genetics of cleft lip and cleft palate. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2013, 163C, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaczkowska, A.; Żukowski, K.; Biedziak, B.; Hozyasz, K.K.; Wójcicki, P.; Zadurska, M.; Budner, M.; Lasota, A.; Szponar-Żurowska, A.; Jagodziński, P.P.; et al. Association of CDKAL1 nucleotide variants with the risk of non-syndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 63, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, J.; Biedziak, B.; Bogdanowicz, A.; Mostowska, A. Identification of Novel Risk Variants of Non-Syndromic Cleft Palate by Targeted Gene Panel Sequencing. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Gruszczyński, D.; Guzik, P.; Mostowska, A.; Walkowiak, J. Ethics of Human Studies in the Light of the Declaration of Helsinki—A Mini-Review. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 91, e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).