Abstract

Artemisinin (ART) production faces bottlenecks due to low and variable yields from its natural source, Artemisia annua. This limitation, coupled with expanding therapeutic potential beyond malaria, highlights the need for innovative production solutions. This systematic review aims to synthesize the evidence on alternative production platforms for ART. We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for studies published primarily between 2020 and 2025. Some search terms included “Artemisinin”, “Artemisia annua”, “biosynthesis”, “in vitro culture”, and “artificial intelligence”. We included primary research articles reporting on strategies for ART production. We narratively synthesized data by production theme. Our review of 30 studies identified four frontiers for ART production: (1) Enhancement in A. annua ART content; (2) In vitro platforms focusing on callus and cell suspension cultures, which offer precise control but face scale-up bottlenecks; (3) Heterologous expression in non-Artemisia plants; and (4) Scalable semi-synthetic routes using microbially fermented precursors and chemical conversion. Furthermore, the review highlights the emerging role of AI-driven predictive modeling in source discovery and process optimization. By integrating these innovations, a robust roadmap exists for sustainable ART production.

1. Introduction

Artemisinin (ART) and its derivatives were first isolated from Artemisia annua L. in the 1970s [1]. They are now indispensable in combating malaria and are at the forefront of global malaria control strategies [2,3]. Recognized for their efficacy against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites, ART-based Combination Therapies (ACTs) have become a cornerstone of global efforts to control and eliminate malaria [4]. More recently, the WHO has endorsed RTS, S, and R21 malaria vaccines, particularly in Africa and other regions with moderate to high malaria transmission. Although these vaccines along with ACTs have strengthened the global response, this life-threatening disease remains a significant health challenge [3]. About 3.3 billion people are at risk, with over 100 countries experiencing ongoing malaria transmission. This widespread burden has driven the market for ACTs, valued at USD 600 million in 2023, with projections indicating a compound annual growth rate of 8% from 2024 to 2030 [5].

Despite advances in ART research [6], production remains a major challenge, both in natural and synthetic contexts [7]. ART yield from A. annua cultivation is inherently low [8], accounting for only 0.01% to 1.5% of the plant’s dry weight [9]. Moreover, the molecule’s structural complexity makes chemical synthesis inefficient and economically unviable [10]. Collectively, these challenges highlight the critical need for robust biotechnological innovations to secure a stable ART supply [11], moving production beyond the limitations of the plant itself.

While several reviews have summarized progress in ART production [12,13,14], a systematic synthesis of the evidence across all alternative platforms is lacking. To address this gap, we performed this systematic review to answer the following research questions: 1. What are the primary biotechnological strategies currently being explored for ART production outside of conventional A. annua cultivation? 2. What is the reported efficacy, scalability, and commercial viability of each strategy? 3. What is the emerging role of artificial intelligence in optimizing these production systems? By systematically collating and synthesizing the available literature, this analysis identifies four key production frontiers, including enhancement in A. annua ART content; in vitro callus and suspension cultures; heterologous expression in non-Artemisia plants; and semi-synthetic routes. Overall, this review provides a comprehensive evidence base to guide future research, funding, and industrial strategy for sustainable ART production.

2. Methods

We conducted and reported this systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [15].

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We performed a comprehensive literature search across the following electronic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search strategy combined keywords and subject headings related to ART and various production methods.

The search string for Google Scholar is as follows: (“artemisinin” OR “artemisinic acid” OR “Artemisia annua”) AND (“biosynthesis” OR “metabolic engineering” OR “heterologous expression” OR “synthetic biology” OR “in vitro culture” OR “semi-synthetic” OR “bioreactor” OR “endophyte” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”).

The search string for PubMed is as follows: (“artemisinin” [Title/Abstract] OR “artemisinic acid” [Title/Abstract] OR “Artemisia annua” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“biosynthesis” [Title/Abstract] OR “metabolic engineering” [Title/Abstract] OR “heterologous expression” [Title/Abstract] OR “synthetic biology” [Title/Abstract] OR “in vitro culture” [Title/Abstract] OR “semi-synthetic” [Title/Abstract] OR “bioreactor” [Title/Abstract] OR “endophyte” [Title/Abstract] OR “artificial intelligence” [Title/Abstract] OR “machine learning” [Title/Abstract]).

The search string for Scopus is as follows: (TITLE-ABS (“artemisinin” OR “artemisinic acid” OR “Artemisia annua”)) AND (TITLE-ABS (“biosynthesis” OR “metabolic engineering” OR “heterologous expression” OR “synthetic biology” OR “in vitro culture” OR “semi-synthetic” OR “bioreactor” OR “endophyte” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”)).

The search string for Web of Science is as follows: TS = ((artemisinin* OR “artemisinic acid” OR “Artemisia annua”) AND (biosynthesis* OR “metabolic engineering” OR “heterologous expression” OR “synthetic biology” OR “in vitro culture” OR semi-synthetic* OR bioreactor* OR endophyt* OR “artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning”)).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Included studies met the following criteria: (1) Publication Type: Peer-reviewed original research articles. (2) Content: Studies developing of testing a method for producing ART or its direct precursors (e.g., artemisinic acid) using biotechnological, semi-synthetic, or synthetic methods. This included metabolic engineering, heterologous expression, in vitro culture, microbial fermentation, and chemical synthesis. (3) Language: Publications were restricted to English. (4) Timeframe: Studies published from January 2020 to October 2025 were included to capture the evolution of the field from field cultivation to synthetic biology. We excluded reviews, patents, editorials, opinion pieces, conference abstracts, and studies with insufficient data.

2.3. Study Selection

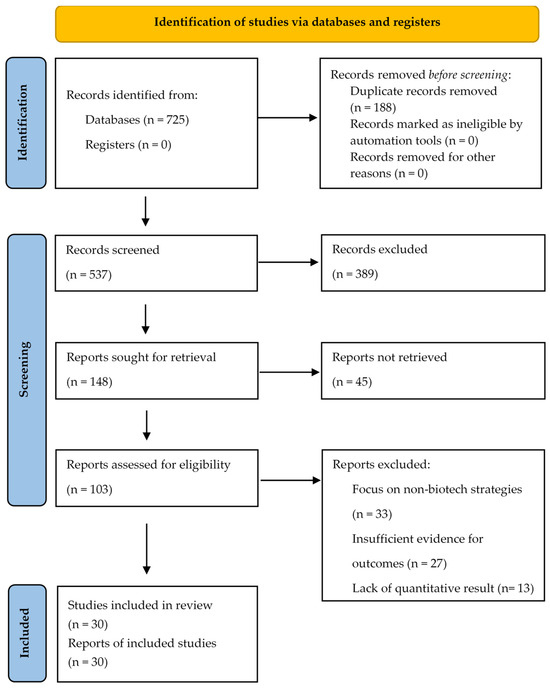

We imported all retrieved citations into the reference manager EndNote, and removed duplicates. Two reviewers (M.Z., M.S.) independently screened titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were then retrieved and assessed for final inclusion by the same two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (D.M.) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the selection process.2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis.

We used a standardized data extraction form to collect relevant information from each included study, including: production platform, author, year, brief method, outcomes (e.g., yield), key findings, limitations, and study quality assessment. Due to the heterogeneity of the study designs and reported outcomes, a meta-analysis was not feasible. Therefore, we narratively synthesized findings, organized thematically based on the identified production frontiers. To assess the quality of the included literature, we performed a qualitative evaluation of experimental rigor based on three key criteria: the presence of appropriate negative/positive controls, the use of biological replicates (n ≥ 3) and the application of statistical analysis to verify yield differences.

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

The initial database search yielded 725 records. After removing 188 duplicates, we screened 537 records based on title and abstract, of which 389 were excluded. We evaluated the full texts of the remaining 103 articles for eligibility. A total of 30 articles were ultimately included in the narrative synthesis after excluding studies focused on non-biotech strategies or lacking quantitative data. The PRISMA diagram is available in Figure 1.

3.2. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

A qualitative assessment of the 30 included studies revealed a generally high level of experimental rigor. The majority of studies utilized appropriate controls (e.g., wild-type A. annua or empty-vector controls in metabolic engineering), biological replicates, and statistical methods. However, Table 1 highlights that one study was of moderate quality due to lacks a distinct positive control group [16].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies along with their quality assessment. Abbreviation: RQ *, research quality; TF, transcription factor.

3.3. Synthesis of Findings

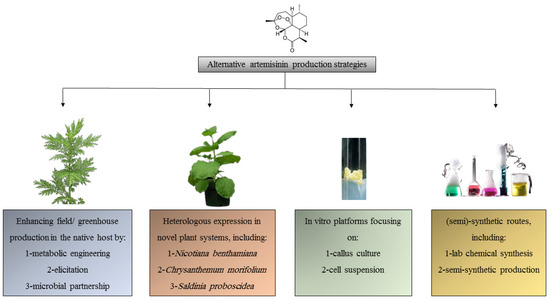

The included studies reveal a landscape of innovation focused on moving ART production beyond agricultural constraints. According to Table 1, the research focus was as follows: ART enhancement in A. annua (n = 18, 60%), In vitro cultures (n = 6, 20%), Heterologous expression in non-Artemisia species (n = 4, 13%), and Semi-synthetic routes (n = 2, 7%). Noting one study overlapped categories, we synthesized the findings into four interconnected themes reflecting the major research frontiers (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Alternative artemisinin production strategies.

3.4. Theme 1: Enhancing Production in the Native Host, Artemisia sp.

3.4.1. Decoding the ART Biosynthetic Pathway: A Prerequisite for ART Content Enhancement

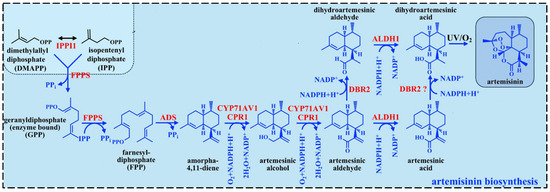

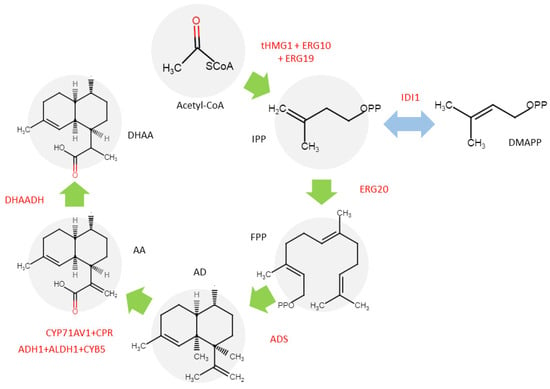

Much of the literature focuses on understanding the ART biosynthetic pathway and its regulation, which are fundamental to all engineering efforts. Understanding this intricate pathway is vital to enhancing ART production, whether by optimizing the native plant system or transferring the ART production machinery to alternative hosts. A tightly regulated cascade of enzymatic reactions and genetic controls orchestrates ART biosynthesis. Central to this process is the amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (ADS), which catalyzes the cyclization of farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) into amorpha-4,11-diene as the essential backbone of ART. This initial step sets the stage for a series of oxidative modifications catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP71AV1) and its redox partner cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR), which sequentially hydroxylate and oxidize amorpha-4,11-diene to yield artemisinic alcohol, aldehyde, and ultimately artemisinic acid [1] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The ART biosynthetic pathway in A. annua. The FPP, which is originates from the activity of the mevalonate (MVA) and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways, generates the sesquiterpene backbone, amorpha-4,11-diene. This intermediate undergoes enzymatic oxidation, mediated by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and other redox enzymes, to yield DHAA. Finally, ART is synthesized via a sequence of enzyme-catalyzed reactions followed by non-enzymatic oxidative modifications, including light-dependent peroxidation. Abbreviations: FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1; DBR2, double bond reductase 2; CYP, cytochrome P 450 CYP71AV1; ADS, amorpha-4,11-diene synthase.

A pivotal branch in the pathway is governed by artemisinic aldehyde Δ11 (13) reductase (DBR2), which redirects artemisinic aldehyde toward dihydroartemisinic aldehyde, the precursor for dihydroartemisinic acid (DHAA). Under oxidative conditions, DHAA undergoes non-enzymatic conversion to ART, a reaction finely tuned by the plant’s glandular trichome microenvironment. Another key enzyme, ALDH1, oxidizes DHAA to dihydroartemisinic acid [1].

The pathway’s regulation is a symphony of genetic interplay. Transcription factors such as WRKY, MYB, and AP2/ERF families act as molecular conductors, binding to promoters of key genes (ADS, CYP71AV1, and DBR2) to amplify expression under stimuli signaling [12]. Conversely, microRNAs like miR858 and miR159 fine-tune this orchestra, silencing competing pathways to channel metabolic flux toward ART biosynthesis [45]. By dissecting these molecular intricacies, researchers are not only decoding nature’s blueprint but also reengineering it via metabolic engineering and synthetic biology to increase ART yields. The discussion of ART genetic modifications is beyond the scope of this article, so readers can refer to relevant reviews [46].

3.4.2. Artemisia Species as Native Hosts

Evidence from multiple studies indicates that while the ultimate goal may be fully ex planta production, significant biotechnological innovations focus on enhancing ART synthesis within plant systems themselves (Table 1). Artemisia plants are the primary natural source of ART and the potential target for engineering. The ART biosynthesis pathway is thought to be an ancestral trait shared by plants within the genus Artemisia [47]. This theory is partially supported by studies reporting the expression of ART biosynthesis-related genes in several Artemisia species, including A. vulgaris, A. absinthium and A. verlotiorum [48]. Recent evidence has further strengthened this hypothesis with the detection of ART intermediates in A. alba for the first time [49]. Interestingly, ART accumulation does not peak at the same growth stage in all Artemisia species. In A. absinthium, ART levels are highest during flowering, whereas in A. vulgaris and A. annua, the peak occurs during the budding stage [1]. This variability explains why some studies fail to detect ART or report it at undetectable levels, as these investigations often focus on specific growth stages when ART synthesis is minimal.

3.4.3. ART Content Enhancement by Metabolic Engineering

Table 1 identified transcription factor (TF)/key enzyme overexpression technique as the most used genetic engineering approach. For example, Yuan et al. [17] engineered A. annua via overexpression of the TF MYC3, resulting in a 1.4 to 1.8-fold increase in ART content. Similarly, Hu et al. [18] overexpressed PDF2, increasing GST density by up to 82% and ART content by 55–73%. Other related studies focused on transcription factors such as YABBY5 [50], MYB108 [51], and ABI5 [24]. Notably, Li et al. [16] employed a synthetic biology multigene construct to reconstruct the ART pathway, achieving ART content up to 24.7 mg g−1 DW (a 2.4 to 3.4-fold increase compared to the control). However, limitations persist; for example, Yuan et al. [17] noted that yield increases from MYC3 were less than those from ART-specific regulators, suggesting internal metabolic feedback limits.

The unstable and low accumulation of ART in A. annua (1–10 mg g−1 dry weight) results primarily from its biosynthesis, which occurs almost exclusively in the glandular secretory trichomes (GSTs) located on the leaf and flower epidermis. These specialized 10-cell structures are highly fragile and are often lost from A. annua tissues during harvest, posing a main challenge for traditional field-based approaches [9]. In addition to their role in ART production, GSTs also regulate the biosynthetic pathway through various mechanisms. For example, several transcription factors and GST developmental transporters have been identified as critical modulators of ART accumulation. One such modulator is the transporter ABCG40, which its overexpression in GSTs increases ART levels [31]. Transcription factors such as WRKY and MYB also influence ART biosynthesis through complex regulatory mechanisms [22,51]. Therefore, regulatory networks are crucial in controlling GST-localized ART biosynthesis [52,53]. ART biosynthetic genes also show different expression patterns depending on the developmental stage of the GSTs. In young leaves, GSTs prominently express ART synthesis genes, whereas in older leaves this expression is almost negligible [54]. This observation highlights that efficient ART biosynthesis is predominantly associated with immature GSTs [16].

Until recently, GSTs were believed to be the sole cellular structures capable of producing ART. This assumption remained unchallenged until researchers discovered that non-GST cells also possess the ability to synthesize ART [38]. Emerging evidence indicates that GST and non-GST cells utilize distinct mechanisms in the final steps of ART synthesis. In GSTs, ART is formed through the autoxidation of DHAA, whereas in non-GST cells, enzymatic reactions mediate the conversion of DHAA to ART [9]. This discovery opens new avenues for manipulating ART production in different cell types or potentially in non-specialized cells in culture.

3.4.4. Elicitation Strategies in Field/Greenhouse Systems

Elicitation strategies were prominent in the reviewed studies. Tripathi et al. [19] demonstrated that co-exposure of 0.5 mg L−1 AgNPs and 3 h of UV-B irradiation resulted in a ~4.27-fold increase in ART content, though higher concentrations (5.0 mg L−1) proved toxic. Foliar elicitation with Menadione Sodium Bisulphite (MSB) increased ART by 62.37% [20]. Soil application of Graphene increased GST density by 30–80% and ART content by 5% per unit weight, though high concentrations (>100 mg/L) were toxic [21]. Phytohormones also played a key role; exogenous Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) increased ART 1.9-fold [25], while Strigolactone increased GST density by 21% [27]. Under stress conditions, Nitric Oxide (NO) enhanced ART under cadmium stress [26], and ABA enhanced ART under Copper stress [30].

Elicitation by Phytohormones

A major advantage of field/greenhouse platforms is the ability to apply phytohormone elicitors to boost ART biosynthesis. Phytohormones, such as abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellins (GA), jasmonic acid (JA), MeJA, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and salicylic acid are potent modulators of secondary metabolite biosynthesis in A. annua (Table 1). These compounds enhance ART accumulation by upregulating genes and transcription factors associated with its biosynthetic pathway [46] when applied under controlled in vitro conditions.

Jasmonic Acid (JA) induces the expression of key transcription factors, including SPL2, TCP15/14, ERF1/2, WRKY17/9, GSW1, bHLH113, and MYC2 [55]. Transcriptomic studies have also identified genes such as TUBBY, Ulp1, AATL1, BAMT, and ORA as critical hubs in the MeJA-induced ART biosynthetic network [56,57]. Abscisic acid (ABA) signaling involves the transcription factor bZIP1. When phosphorylated by the ABA-responsive kinase APK1, bZIP1 forms a complex with bH113 and GSW1. This complex positively regulates ART biosynthesis [16]. ABA also plays a role in the GST development and reactive oxygen species homeostasis [30]. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) increases ART content by upregulating the expression of DBR2, ALDH1, CYP71AV1, and ADS. Additionally, IAA enhances GST density, although the precise mechanisms underlying these effects remain unclear [25]. Gibberellins (GAs) regulate GST development and ART production by increasing trichome density and the transcript levels of CYP71AV1, ADS, and FPS [53]. Salicylic acid (SA) also induces ART biosynthesis by activating transcriptional factors such as WRKY17 and the TGA6-NAC1 complex, which upregulate the expression of ERF1 and other ART biosynthetic genes [29].

Elicitation by Stressful Factors

Moderate levels of environmental stress can act as elicitors, enhancing secondary metabolite production in controlled in vitro environments. Heavy elements, for instance, promote ART accumulation, potentially through non-enzymatic conversion of ART precursors under oxidative stress [26,30]. While the mechanisms underlying these effects remain unclear, oxidative stress appears to play a significant role. The variability in stress responses across studies highlights the need for standardized experimental conditions (Table 1). Combining multiple stressors in a controlled manner may activate synergistic signaling pathways, further enhancing ART production.

Elicitation by Microbial Partnerships

Strategies using microbial consortia showed promise. Endophytes are plant-associated microorganisms that inhabit internal plant tissues without causing harm. Their presence often confers numerous benefits to the host plant, including increased tolerance to stressful conditions, growth, and secondary metabolite production [58]. Notably, A. annua endophytes have been shown to synergistically increase both biomass and ART accumulation. When a combination of endophytes—including Acinetobacter pittii, Burkholderia sp., Bacillus subtilis, and B. licheniformis—was applied as a bio-inoculant, ART yields surpassed those achieved with any of these bacteria in monocultures [33]. Recently, it has been found that a plant growth-promoting endophytic consortium including B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, Burkholderia sp., and Acinetobacter pittii improved ART biosynthesis via up-regulating ISPH, SQC, ADH1&2, HMGS, HMGR, DXR1, DXS1, FPS, ADS, and CYP7AV1 [32]. These findings suggest that employing an endophytic consortium offers a promising and sustainable biotechnological strategy to enhance ART production. This approach not only increases ART yield but also aligns with eco-friendly and cost-effective agricultural practices [59].

3.5. Theme 2: ART Production by In Vitro Systems

Plants exhibit rapid responses to even minor changes in their chemical and physical environments. This characteristic makes tissue and cell culture an effective platform for controlling environmental factors to optimize the production of secondary metabolites [60,61,62]. Achieving this requires two critical steps: first, the cultivation of plant cells or tissues in vitro, and second, the application of effective elicitors using precise protocols to enhance the production of the target metabolite.

Table 1 primarily highlights callus and cell suspension in the included timeframe. Nabi et al. [59] achieved a maximum ART yield of 780 ng g−1 DW in A. maritima callus cultures using MeJA elicitation. Mosoh and Vendram [60] utilized in vitro callus culture with PGRs and AgNO3, but noted that ART content remained lower than in control plants. Lim et al. [61] explored in vitro cell suspension cultures with LED lighting, identifying a trade-off where optimal biomass conditions were suboptimal for ART accumulation. Other in vitro approaches included foliar application of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles [62] and cultivation under monochromatic blue light, which upregulated ADS expression [27].

Light also plays a critical role in regulating ART biosynthesis by modulating GST density, allowing precise control over this factor. The COP1-HY5-BBX21 module is central to this light-mediated control. In darkness, COP1 interacts with BBX21 and AaHY5, targeting them for degradation via the ubiquitin-26S proteasome pathway, which suppresses ART biosynthesis. Conversely, light inhibits COP1 activity, allowing HY5 and BBX21 to accumulate. HY5, either independently or as part of the HY5-BBX21 complex, activates genes such as MYB108, ORA, and GSW1, driving ART biosynthesis and GST development [63]. Different light spectra also influence ART production in specific ways when applied to cultures: red light stimulates the mevalonate (MVA) pathway; yellow light increases secretory trichome density; green light enhances volatile compound variations; and blue light thickens the leaf epidermis, increases cell size, promotes ADS expression, and boosting ART levels [38]. Therefore, optimizing light conditions is a key strategy in vitro.

3.6. Theme 3: Heterologous Expression in Novel Plant Systems

Table 1 lists four key studies in this domain. Guo et al. [40] reported transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana, producing DHAA (0.51 mg g−1 DW) and ART (0.041 mg g−1 DW) after UV treatment. Firsov et al. [43] explored Chrysanthemum morifolium with A. annua genes, but notably, ART was not detected via GC-MS, highlighting the biochemical limits of the host. In a separate study, Firsov et al. [41] successfully transferred the entire biochemical pathway into Chrysanthemum, but transformation efficiency was low (0.33%). Additionally, Randrianarivo et al. [42] isolated a natural stereoisomer, (−)-6-epi-artemisinin, from Saldinia proboscidea, though yields were low (2.5 mg from 500 g DW).

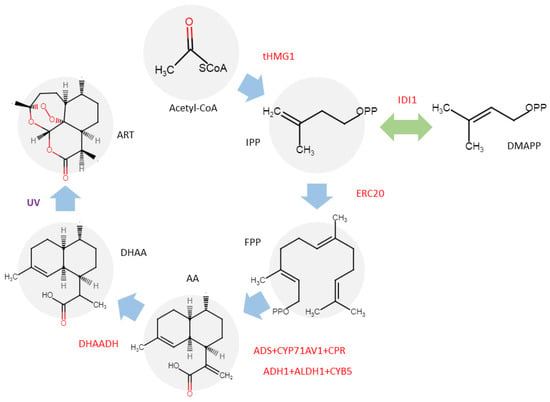

A significant step ‘beyond the Artemisia’ involves transferring the ART biosynthetic pathway into alternative hosts. The biochemical evaluation of Saldinia proboscidea has led to the discovery of an isomer of ART, specifically (−)-6-epi-artemisinin [42]. This finding represents the inaugural report of an ART-related compound isolated from a non-Artemisia genus, signifying a pivotal milestone in the expansion of potential ART sources beyond the traditional genus. Subsequently, Chrysanthemum morifolium has attracted the attention of biotechnologists due to its high content of sesquiterpenoids, terpenoids, and their precursors. This species has been successfully transformed with key genes from the ART biosynthetic pathway, including the HMGR gene from yeast and the DBR2, CPR, CYP71AV1, and ADS genes from A. annua [41,43]. Recently, researchers successfully reconstructed the ART biosynthetic pathway in Nicotiana benthamiana by transiently expressing eight proteins alongside the targeted optimized enzyme DHAADH. While this system enabled the production of the precursor DHAA at a concentration of 0.5 mg g−1 DW, ART was not initially detected within the plant tissue. To overcome this, the researchers irradiated the N. benthamiana leaves with UV light to accelerate the specific auto-oxidation of DHAA, ultimately achieving an ART content of 0.04 mg g−1 DW (Figure 4) [40]. These advancements highlight the feasibility of transplanting the ART biosynthetic pathway into non-Artemisia plants, offering a promising avenue for diversifying and enhancing ART production in alternative plant chassis.

Figure 4.

Reconstruction ART biosynthesis pathway in N. benthamiana. The transferred genes are shown in red [40].

3.7. Theme 4: Chemical and Semi-Synthetic Frontiers

Table 1 includes two studies representing this frontier. Guo et al. [40] described a metabolic engineering approach in S. cerevisiae using a bioreactor, producing 3.97 g L−1 of DHAA (Figure 5). Moreover, Chen et al. [44] achieved a 41% yield of ART from DHAA using “Dark” Singlet Oxygen, providing a scalable method. However, limitations were noted, such as long reaction times for chemical conversion.

Figure 5.

Synthetic biology of ART biosynthesis pathway in S. cerevisiae. The transferred genes are shown in red [40].

The included literature covers purely chemical and hybrid biochemical routes. Research into the chemistry of ART expanded rapidly between 1985 and 2015. While the total synthesis of ART has been achieved, the evidence consistently shows that it remains commercially impractical due to the molecule’s complexity and high costs. Consequently, research has pivoted to semi-synthesis, where genetically engineered yeast produce artemisinic acid, which is then chemically converted to ART. This method is a key ‘beyond the plant’ innovation that provides a scalable alternative source [40].

The first semi-synthesis of ART was successfully reported by Chen et al. [44]. This method, which involves the conversion of artemisinic acid to ART, is technically straightforward, scalable and eliminates the need for intermediate purification. By using singlet oxygen resources, the process also avoids the need for specialized photochemical tools. Semi-synthesis represents a practical approach to ART production that decouples the final steps from the plant source. However, further research is essential to optimize this method and achieve a cost-effective solution for large-scale applications [64].

As a commercial alternative, biochemical processes have been developed to produce ART on an industrial scale. One such approach involves genetically engineered yeast-mediated fermentation to produce artemisinic acid. After conversion, artemisinic acid is then converted to ART in a semi-synthetic reaction. This method utilizes microbial cell factories, a key ‘beyond the plant’ innovation, providing a scalable alternative source of ART and has the potential to make a significant contribution to meeting global demand [65].

3.8. A Trend: The Role of AI in Discovery and Optimization

Artificial intelligence (AI) represents a set of tools to improve ART production beyond plant systems in future research. AI, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), offers a revolutionary avenue in natural product discovery within medicinal plants and microbial systems. By streamlining the analysis of vast biological datasets, ML and DL are becoming indispensable in the search for new ART sources or pathways [66]. Machine learning can effectively handle large-scale data from plant genomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics, and phenomics, identifying patterns that correlate ART production with various stimuli. Predictive models can estimate the likelihood of ART production in plants or microbes with genetic or chemical profiles similar to A. annua. Subtle patterns detected by ML and DL tools may reveal the existence of ART biosynthetic pathways in previously unstudied species. By analyzing environmental factors affecting ART yield, ML/DL facilitates recommendations for optimal growth conditions, ensuring maximum production in bioreactors or other controlled systems. Algorithms can also pinpoint the key features, such as genes, enzymes, and pathways linked to ART biosynthesis, aiding in the selection of promising candidate hosts or engineering targets [67]. For instance, the integration of ML frameworks with multi-omics data has shown promise in resolving complex biosynthetic pathways. Bai et al. [68] utilized the AutoGluon-Tabular framework to analyze data from Arabidopsis, successfully predicting genes encoding enzymes for three major categories of plant secondary metabolites, including terpenoids. Their analysis identified that genomic and proteomic features were the most critical predictors of model performance, surpassing transcriptomic or epigenomic data. Furthermore, the model demonstrated robust cross-species applicability, achieving high predictive accuracy when validated in poppy, grape, maize, and tomato. Applying such ML strategies to Artemisia could accelerate the identification of novel candidates involved in ART biosynthesis, overcoming the limitations of traditional analysis approaches. These strategies accelerate research efforts, offering time-efficient and cost-effective methods to identify new ART sources and optimize biotechnological production processes.

4. Discussion

This systematic review synthesizes the evidence from 30 studies on biotechnological strategies for ART production. This review directly addressed the core questions guiding the inquiry into alternative ART production. Addressing our first question regarding the primary biotechnological strategies being explored, this review identified four major frontiers: (1) Enhancement in A. annua ART content; (2) In vitro callus and suspension cultures; (3) Heterologous expression in plants like Nicotiana and Chrysanthemum; and (4) Semi-synthetic production combining yeast fermentation and chemical synthesis.

Answering our second question on efficacy and scalability, the evidence shows that the semi-synthetic pathway remains the most scalable alternative, though it faces challenges such as catalyst stability and reaction times [40]. Table 1 highlights some challenges in in vitro callus and suspension systems, such as trade-offs between biomass and ART accumulation [35] and lower yields compared to the field context [28]. Finally, heterologous expression in non-Artemisia plants is currently suited for novel plant chassis [40].

Finally, addressing our third question, the role of computational tools has evolved into a critical enabler across all frontiers; AI and machine learning are no longer just theoretical but are actively being used to mine genomic data for novel biosynthetic pathways, predict optimal hosts, and dynamically optimize growth conditions to maximize metabolic flux and final yield.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

The primary strength of this review is its systematic and comprehensive methodology, which provides a transparent and reproducible synthesis of the available evidence across multiple production frontiers. However, several limitations should be noted. First, our search was restricted to English-language publications, potentially introducing language bias. Second, the heterogeneity of the methodologies prevents a quantitative meta-analysis. While our quality assessment indicates that the majority of studies utilized sufficient biological replicates and controls, the variability in extraction methods and yield reporting units (e.g., % dry weight vs. mg/L) limits direct quantitative comparison. Finally, as with any field, there is a risk of publication bias, where studies with positive or significant results are more likely to be published than those with null findings.

4.2. Implications for Future Research and Policy

Based on the synthesized evidence, we recommend the following directions for future research: (1) Head-to-head comparisons: There is a need for studies that directly compare the economic and environmental lifecycle costs of the leading alternative platforms. (2) AI integration: Research should focus on integrating AI not just for discovery but for real-time process control in bioreactors to maximize metabolite flux. (3) Regulatory pathways: As these technologies mature, research into the regulatory and quality control frameworks necessary for pharmaceutical-grade ART from non-traditional sources is critical. (4) For policymakers and funding bodies, our review highlights the need for continued investment in these diverse biotechnological platforms to create a resilient and stable supply chain for this essential medicine.

4.3. Critical Barriers to Translation

Despite the biological efficacy of these platforms, several major challenges remain. First, significant knowledge gaps persist regarding non-glandular synthesis. While the enzymatic capability of non-GST cells has been identified, the specific transport mechanisms and storage compartments preventing autotoxicity in these cells are unknown, limiting our ability to engineer high-yield non-glandular chassis. Second, regulatory challenges for non-traditional sources are distinct from natural ART. ART derived from genetically modified microbial consortia or novel plant hosts requires rigorous GMP validation to ensure that host-specific metabolites do not contaminate the final pharmaceutical product, a regulatory pathway far more complex than standard botanical extraction.

Technically, plant systems frequently encounter metabolic bottlenecks; redirecting carbon flux toward the ART pathway often compromises host fitness by depleting the common precursor FPP, which is essential for sterol biosynthesis. Furthermore, the accumulation of intermediates like artemisinic aldehyde can be cytotoxic to microbial hosts, necessitating pathway balancing and transport engineering. Economically, the barrier is equally steep. While in vitro systems offer control, the capital expenditure (CAPEX) for large-scale bioreactors and the operational costs (OPEX) for energy, media, and sterile maintenance significantly exceed the costs of open-field farming, where solar energy and soil are free inputs. Moreover, downstream processing (DSP) and purification from complex biomass remains a major cost driver, often accounting for 60–80% of total production costs. Consequently, biotechnological ART must not only match but exceed the yield efficiency of A. annua to compete with the fluctuating but generally low cost of natural ART.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Alternative Platforms of ART Production

To systematically evaluate the commercial viability of these diverse biotechnological approaches, it is essential to contrast their performance against the current agricultural standard. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of the identified production frontiers, analyzing them based on yield potential, scalability, and Technology Readiness Level (TRL). While semi-synthetic routes via yeast fermentation have achieved industrial maturity (TRL 9) comparable to field cultivation, other platforms such as in vitro cultures and heterologous expression in non-Artemisia hosts currently occupy distinct developmental niches. This comparison highlights that while in vitro methods offer superior biological control, their widespread adoption is currently limited by the economic constraints compared to the established efficacy of field cropping.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Alternative ART Production Platforms.

Building on these findings, we propose a criteria-based framework for selecting the optimal production platform based on specific end-use requirements and resource constraints. Evidence suggests that semi-synthetic production via yeast fermentation remains the superior choice for industrial-scale pharmaceutical supply chains requiring high purity, consistency, and total independence from climatic variables. In contrast, for sustainable agricultural improvement in regions with existing cultivation infrastructure, the application of microbial consortia provides a cost-effective, eco-friendly strategy to enhance biomass and ART content without the regulatory complexities of genetic modification. In vitro cultures emerge as the preferred platform for controlled laboratory production and metabolic engineering. Finally, heterologous expression in non-Artemisia plants is currently best suited for experimental pathway elucidation and exploring novel biological chassis.

5. Conclusions

The vital need for a scalable supply of ART, hindered by the inherent limitations of A. annua cultivation, necessitates a paradigm shift towards biotechnological production systems. Beyond scientific feasibility, these strategies offer industrial and socioeconomic benefits. Industrially, moving production from the field to controlled bioreactors (via semi-synthesis) ensures a year-round supply chain that is resilient to climate variability. While in vitro cultures show potential, optimization of trade-offs between growth and secondary metabolism is still required. Economically, AI-driven process optimization promises to lower production costs, thereby stabilizing the historically volatile market prices of ACTs. Socially, securing a consistent supply of pharmaceutical-grade ART is an ethical imperative; it ensures equitable access to life-saving therapies in high-burden regions, directly supporting the WHO’s malaria elimination goals. By integrating these innovations, researchers can chart a robust roadmap toward sustainable ART production, reshaping it from a variable botanical extract into a reliable cornerstone of global health.

Author Contributions

M.S. conceptualization; M.S. and M.Z. writing and preparation of the initial draft; M.Z. visualization, D.M. supervision; D.M. writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Institut Universitaire de France (IUF) under the Senior Chair program (2024–2029). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ACT | Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies |

| ADS | Amorpha-4,11-diene synthase |

| ALDH1 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 |

| ART | Artemisinin |

| BFS | β-farnesene synthase |

| CPS | β-caryophyllene synthase |

| CYP | Cytochrome P 450 CYP71AV1 |

| DBR2 | Double bond reductase 2 |

| DHAA | Dihydroartemisinic acid |

| DL | Deep learning |

| DW | Dry Weight |

| DXR | 1-deoxyxylulouse 5-phosphate reductoisomerase |

| DXS | 1-deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate synthase |

| FPP | Farnesyl pyrophosphate |

| FPS | Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| GST | Glandular secretory trichomes |

| HMGR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase |

| HMGS | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| MeJA | Methyl jasmonate |

| ML | Machine learning |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| SL | Strigolactone |

| TF | Transcription factor |

References

- Yin, Q.; Xiang, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lyn, R.; Yuan, L.; Chen, S. The evolutionary advantage of artemisinin production by Artemisia annua. Trends Plant Sci. 2025, 30, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, P.J.; Asua, V.; Conrad, M.D. Emergence, transmission dynamics and mechanisms of artemisinin partial resistance in malaria parasites in Africa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 373–384, Correction in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereje, N.; Fallah, M.P.; Shaweno, T.; Duga, A.; Mazaba, M.L.; Raji, T.; Folayan, M.O.; Ngongo, N.; Ndembi, N.; Kaseya, J. Resurgence of malaria and artemisinin resistance in Africa requires a concerted response. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 362–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwimana, A.; Legrand, E.; Stokes, B.H.; Ndikumana, J.-L.M.; Warsame, M.; Umulisa, N.; Ngamije, D.; Munyaneza, T.; Mazarati, J.-B.; Munguti, K. Emergence and clonal expansion of in vitro artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H mutant parasites in Rwanda. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1602–1608, Correction in Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, P. The 2023 WHO World malaria report. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liao, B.; Yuan, L.; Shen, X.; Liao, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, H.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, L.; Chen, S. 50th anniversary of artemisinin: From the discovery to allele-aware genome assembly of Artemisia annua. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1243–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Xu, M. New clinical application prospects of artemisinin and its derivatives: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 115, Correction in Infect. Dis. Poverty 2024, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, H.; Han, Y.; Zheng, X.; Wang, M.; Feng, W. From plant to yeast—Advances in biosynthesis of artemisinin. Molecules 2022, 27, 6888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisth, D.; Mishra, S. Unlocking the potential of Artemisia annua for artemisinin production: Current insights and emerging strategies. 3 Biotech 2025, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, N.J. Qinghaosu (artemisinin): The price of success. Science 2008, 320, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Xia, F.; Wang, Q.; Liao, F.; Guo, Q.; Xu, C.; Wang, J. Discovery and repurposing of artemisinin. Front. Med. 2022, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.I.; Choudhary, S.; Zehra, A.; Naeem, M.; Weathers, P.; Aftab, T. Enhancing artemisinin content in and delivery from Artemisia annua: A review of alternative, classical, and transgenic approaches. Planta 2021, 254, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.-Y.; Ma, D.-M.; Judd, R.; Jones, A.L. Artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua and metabolic engineering: Questions, challenges, and perspectives. Phytochem. Rev. 2016, 15, 1093–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, A.M.; Saiman, M.Z.; Simonsen, H.T.; Ikram, N.K.K. Current state, strategies, and perspectives in enhancing artemisinin production. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 23, 283–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qin, W.; Liu, H.; Chen, T.; Yan, X.; He, W.; Peng, B.; Shao, J.; Fu, X.; Li, L. Increased artemisinin production by promoting glandular secretory trichome formation and reconstructing the artemisinin biosynthetic pathway in Artemisia annua. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Sheng, Y.; Bao, J.; Wu, W.; Nie, G.; Wang, L.; Cao, J. AaMYC3 bridges the regulation of glandular trichome density and artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, T.; Ye, Y.; Shao, J.; Yan, X.; Peng, B.; Li, L.; Tang, K. AaPDF2 promotes glandular trichome formation in Artemisia annua through jasmonic acid signaling. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, D.; Goswami, N.K.; Pandey-Rai, S. Interactive effect of biogenic nanoparticles and UV-B exposure on physio-biochemical behavior and secondary metabolism of Artemisia annua L. Plant Nano Biology 2024, 10, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, A.L.; Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Borges, A.A.; Boto, A.; Jiménez-Arias, D. Foliar treatment with MSB (menadione sodium bisulphite) to increase artemisinin content in Artemisia annua plants. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Yan, N.; Lin, J.; Hou, L.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Wen, T.; Li, C. Graphene enhances artemisinin production in the traditional medicinal plant Artemisia annua via dynamic physiological processes and miRNA regulation. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, S.-I.; Yanan, M.; Fu, X.; Shen, Q.; Li, Y.; Rahman, S.-u.; Peng, B.; Huang, L.; Tang, K. JA-regulated AaGSW1–AaYABBY5/AaWRKY9 complex regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Plant Cell Physiol. 2023, 64, 771–785. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Du, Y.; Sun, Z.; Cheng, B.; Bi, Z.; Yao, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yao, R.; Kang, S. Manual correction of genome annotation improved alternative splicing identification of Artemisia annua. Planta 2023, 258, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, P.; Sheng, M.; Li, L.; Ma, X.; Du, Z.; Tang, K.; Hao, X.; Kai, G. AaABI5 transcription factor mediates light and abscisic acid signaling to promote anti-malarial drug artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, F.; Zhang, L.; Lu, R.; Pan, X.; Tan, H. Effects of exogenous indole-3-acetic acid on the density of trichomes, expression of artemisinin biosynthetic genes, and artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 70, 1870–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Aftab, T. Nitric oxide induces antioxidant machinery, PSII functioning and artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua under cadmium stress. Plant Sci. 2023, 334, 111754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, K.I.; Zehra, A.; Choudhary, S.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Khan, R.; Aftab, T. Exogenous strigolactone (GR24) positively regulates growth, photosynthesis, and improves glandular trichome attributes for enhanced artemisinin production in Artemisia annua. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 4606–4615. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, T.E.; Ahmed, E.-S.S. Improving artemisinin and essential oil production from Artemisia plant through in vivo elicitation with gamma irradiation nano-selenium and chitosan coupled with bio-organic fertilizers. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 996253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, Y.; Xie, L.; Hao, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, W.; Wang, C.; Yan, X.; Wu-Zhang, K.; Yao, X. AaWRKY17, a positive regulator of artemisinin biosynthesis, is involved in resistance to Pseudomonas syringae in Artemisia annua. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehra, A.; Choudhary, S.; Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Khan, M.M.A.; Aftab, T. Exogenous abscisic acid mediates ROS homeostasis and maintains glandular trichome to enhance artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua under copper toxicity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Liu, H.; Hassani, D.; Peng, B.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, L.; Liu, P.; Pan, Q. AaABCG40 enhances artemisinin content and modulates drought tolerance in Artemisia annua. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Pandey, P.; Tripathi, S.N.; Kalra, A. Plant growth-promoting endophytic consortium improved artemisinin biosynthesis via modulating antioxidants, gene expression, and transcriptional profile in Artemisia annua (L.) under stressed environments. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Awasthi, A.; Singh, S.; Sah, K.; Maji, D.; Patel, V.K.; Verma, R.K.; Kalra, A. Enhancing artemisinin yields through an ecologically functional community of endophytes in Artemisia annua. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 150, 112375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, N.; Singh, S.; Saffeullah, P. Methyl jasmonate elicitation improved growth, antioxidant enzymes, and artemisinin content in in vitro callus cultures of Artemisia maritima L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 177, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosoh, D.A.; Vendrame, W.A. Engineered elicitation in Artemisia annua L. callus cultures alters artemisinin biosynthesis, antioxidant responses, and bioactivity. npj Sci. Plants 2025, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.H.; Khaw, M.L.; Yungeree, O.; Hew, W.H.; Parab, A.R.; Chew, B.L.; Wahyuni, D.K.; Subramaniam, S. Effects of LEDs, macronutrients and culture conditions on biomass and artemisinin production using Artemisia annua L. suspension cultures. Biotechnol. Prog. 2025, 41, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoobi, A.; Saboora, A.; Asgarani, E.; Efferth, T. Iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NPs) elicited Artemisia annua L. in vitro, toward enhancing artemisinin production through overexpression of key genes in the terpenoids biosynthetic pathway and induction of oxidative stress. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2024, 156, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, E.M.; Guimarães-Dias, F.; Gama Td, S.; Macedo, A.L.; Valverde, A.L.; de Moraes, M.C.; de Aguiar-Dias, A.C.A.; Bizzo, H.R.; Alves-Ferreira, M.; Tavares, E.S. Artemisia annua L. and photoresponse: From artemisinin accumulation, volatile profile and anatomical modifications to gene expression. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Liu, R.; Long, C.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, C. Using β-ocimene to increase the artemisinin content in juvenile plants of Artemisia annua L. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, R.; Zhu, J. Dihydroartemisinic acid dehydrogenase-mediated alternative route for artemisinin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firsov, A.; Pushin, A.; Motyleva, S.; Pigoleva, S.; Shaloiko, L.; Vainstein, A.; Dolgov, S. Heterologous biosynthesis of artemisinin in Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. Separations 2021, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randrianarivo, S.; Rasolohery, C.; Rafanomezantsoa, S.; Randriamampionona, H.; Haramaty, L.; Rafanomezantsoa, R.M.; Andrianasolo, E.H. (−)-6-epi-Artemisinin, a Natural Stereoisomer of (+)-Artemisinin in the Opposite Enantiomeric Series, from the Endemic Madagascar Plant Saldinia proboscidea, an Atypical Source. Molecules 2021, 26, 5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firsov, A.; Mitiouchkina, T.; Shaloiko, L.; Pushin, A.; Vainstein, A.; Dolgov, S. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of chrysanthemum with artemisinin biosynthesis pathway genes. Plants 2020, 9, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Han, W.-B.; Hao, H.-D.; Wu, Y. A facile and scalable synthesis of qinghaosu (artemisinin). Tetrahedron 2023, 69, 1112–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Hao, K.; Lv, Z.; Yu, L.; Bu, Q.; Ren, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, R.; Zhang, L. Profiling of phytohormone-specific microRNAs and characterization of the miR160-ARF1 module involved in glandular trichome development and artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, L.; Tang, K.; Hao, X.; Kai, G. Advanced metabolic engineering strategies for increasing artemisinin yield in Artemisia annua L. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhad292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, J.; Saslis-Lagoudakis, C.H.; Carrió, E.; Ernst, M.; Garnatje, T.; Grace, O.M.; Gras, A.; Mumbrú, M.; Vallès, J.; Vitales, D. A phylogenetic road map to antimalarial Artemisia species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 225, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Bajpai, V.; Khandelwal, N.; Varshney, S.; Gaikwad, A.N.; Srivastava, M.; Singh, B.; Kumar, B. Determination of bioactive compounds of Artemisia Spp. plant extracts by LC–MS/MS technique and their in-vitro anti-adipogenic activity screening. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2021, 193, 113707. [Google Scholar]

- Negri, S.; Pietrolucci, F.; Andreatta, S.; Chinyere Njoku, R.; Antunes Silva Nogueira Ramos, C.; Crimi, M.; Commisso, M.; Guzzo, F.; Avesani, L. Bioprospecting of Artemisia genus: From artemisinin to other potentially bioactive compounds. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4791, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kayani, S.-I.; Shen, Q.; Ma, Y.; Fu, X.; Xie, L.; Zhong, Y.; Tiantian, C.; Pan, Q.; Li, L.; Rahman, S.-U. The YABBY family transcription factor AaYABBY5 directly targets cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP71AV1) and double-bond reductase 2 (DBR2) involved in artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia Annua. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Qin, W.; Yan, X.; Wu, Z.; Xie, L.; Kayani, S.L. AaMYB108 is the core factor integrating light and jasmonic acid signaling to regulate artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 2224–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Tan, H. Glandular trichomes: The factory of artemisinin biosynthesis. Med. Plant Biol. 2024, 3, e019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Bu, Y.; Ren, J.; Pelot, K.A.; Hu, X.; Diao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zerbe, P.; Zhang, L. Discovery and modulation of diterpenoid metabolism improves glandular trichome formation, artemisinin production and stress resilience in Artemisia annua. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 2387–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Qin, W.; Yan, X.; Wu-Zhang, K.; Peng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Fu, X. The truncated AaActin1 promoter is a candidate tool for metabolic engineering of artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua L. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 274, 153712. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sudheer, W.N.; Lakshmaiah, V.V.; Mukherjee, E.; Nizam, A.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Nagella, P.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Rezk, A.A. Biotechnological approaches for production of artemisinin, an anti-malarial drug from Artemisia annua L. Molecules 2022, 27, 3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Zhong, G.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, K.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, B. Trichome-Specific Analysis and Weighted Gene Co-Expression Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) Reveal Potential Regulation Mechanism of Artemisinin Biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8473. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.N.; Xu, D.B.; Yan, X.; Wu, Z.K.; Kayani, S.I.; Shen, Q.; Fu, X.Q.; Xie, L.H.; Hao, X.L.; Hassani, D. Jasmonate-and abscisic acid-activated AaGSW1-AaTCP15/AaORA transcriptional cascade promotes artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1412–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.P.; Li, X.P.; Zhou, L.L.; Wang, J.W. Endophytes in Artemisia annua L.: New potential regulators for plant growth and artemisinin biosynthesis. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 95, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Sharma, A.; Singh, S.K.; Sundaram, S. Bio Prospecting of Endophytes and PGPRs in Artemisinin Production for the Socio-economic Advancement. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 81, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.R.; Jariani, P.; Yang, J.-L.; Naghavi, M.R. A comprehensive review of the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying gum and resin synthesis in Ferula species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehzari, M.; Zeinali, M.; Naghavi, M.R. Alternative sources and metabolic engineering of Taxol: Advances and future perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehzari, M.; Zeinali, M.; Naghavi, M.R. CRISPR-based metabolic editing: Next-generation metabolic engineering in plants. Gene 2020, 759, 144993. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, Z.; Miao, Q.; Hu, X.; Yan, X.; Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Ren, L. The AaBBX21–AaHY5 module mediates light-regulated artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua L. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1735–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Amara, Z.; Bellamy, J.F.; Horvath, R.; Miller, S.J.; Beeby, A.; Burgard, A.; Rossen, K.; Poliakoff, M.; George, M.W. Applying green chemistry to the photochemical route to artemisinin. Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triemer, S.; Schulze, M.; Wriedt, B.; Schenkendorf, R.; Ziegenbalg, D.; Krewer, U.; Seidel-Morgenstern, A. Kinetic analysis of the partial synthesis of artemisinin: Photooxygenation to the intermediate hydroperoxide. J. Flow Chem. 2021, 11, 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullowney, M.W.; Duncan, K.R.; Elsayed, S.S.; Garg, N.; van der Hooft, J.J.; Martin, N.I.; Meijer, D.; Terlouw, B.R.; Biermann, F.; Blin, K. Artificial intelligence for natural product drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durand, M.; Besseau, S.; Papon, N.; Courdavault, V. Unlocking plant bioactive pathways: Omics data harnessing and machine learning assisting. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 87, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, W.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Han, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, L. Machine learning assists prediction of genes responsible for plant specialized metabolite biosynthesis by integrating multi-omics data. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).