Exercise-Induced Molecular Adaptations in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases—Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

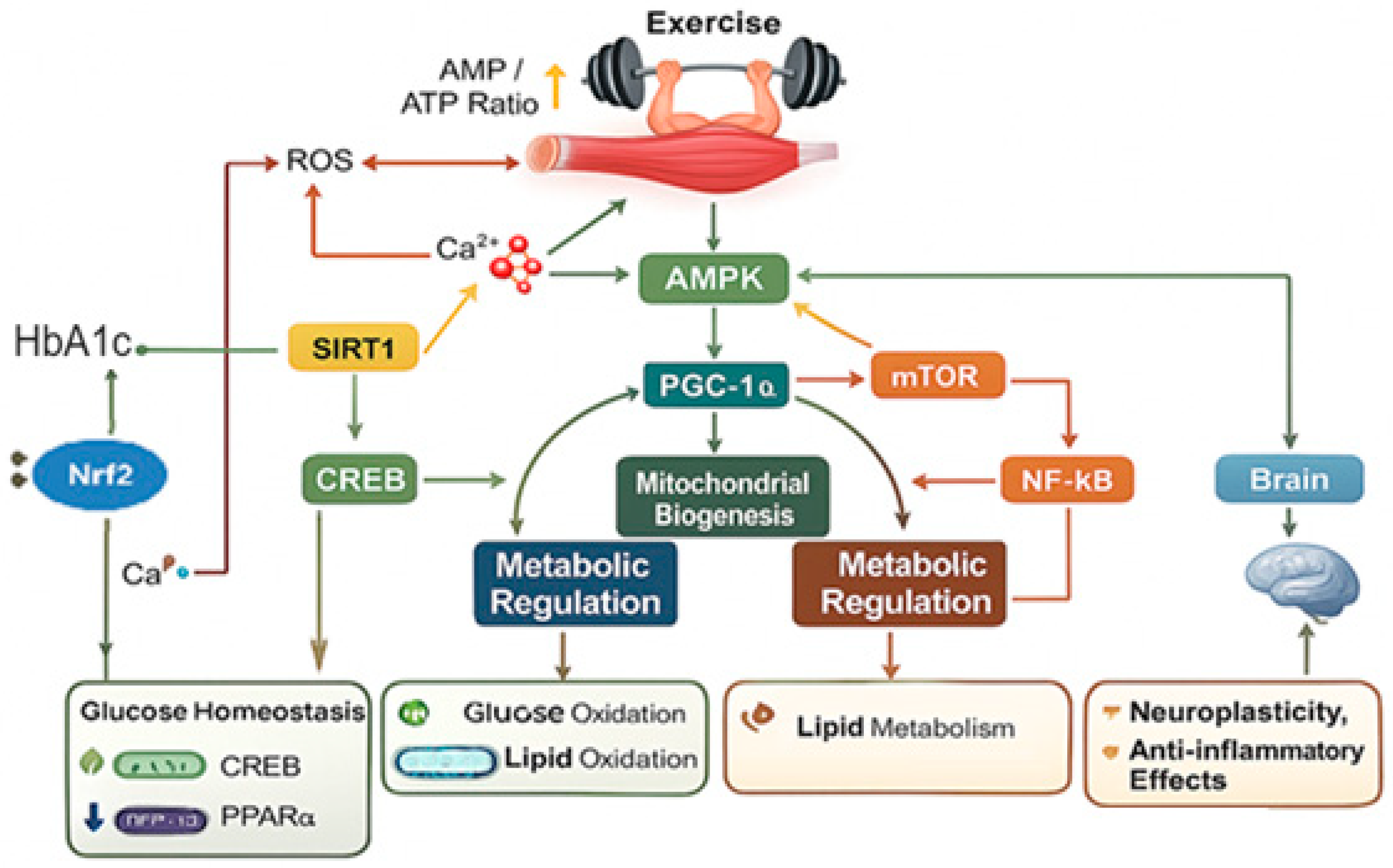

2. Physiological and Molecular Adaptations to Exercise

3. Cellular Signaling Pathways Involved in Exercise Adaptations

3.1. AMPK Pathway: Energy Sensing and Metabolic Regulation

3.2. PGC-1α Signaling: Master Regulator of Oxidative and Mitochondrial Adaptation

3.3. mTOR Pathway: Protein Synthesis, Muscle Hypertrophy, and AMPK Interplay

3.4. MAPK and NF-κB Pathways: Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Regulation

3.5. Epigenetic and microRNA Modulation: Post-Transcriptional and Chromatin-Level Control

4. Exercise-Induced Myokines and Inter-Organ Crosstalk

4.1. Major Exercise-Induced Myokines

4.2. Endocrine and Paracrine Signaling Mechanisms

4.3. Inter-Organ Communication: Muscle–Liver, Muscle–Pancreas, Muscle–Adipose, and Muscle–Brain Axes

4.4. Integrative Role of Myokines in Metabolism and Homeostasis

5. Translational and Clinical Perspectives: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Applications

6. Limitations and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walzik, D.; Wences Chirino, T.Y.; Zimmer, P.; Joisten, N. Molecular insights of exercise therapy in disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggin, J. What Is Physical Activity? A Holistic Definition for Teachers, Researchers and Policy Makers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhay, H.W.; Derseh, N.M.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Gyawali, P.; Yenit, M.K. Prevalence of physical inactivity and associated factors among adults in Eastern African countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e084073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, T.; Flaxman, S.; Guthold, R.; Semenova, E.; Cowan, M.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C.; Stevens, G.A.; Country Data Author Group. National, regional, and global trends in insufficient physical activity among adults from 2000 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 507 population-based surveys with 5·7 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e1232–e1243, Erratum in Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Fu, Y.; Chen, D.; Zhang, H.; Xue, E.; Shao, J.; Tang, L.; Zhao, B.; Lai, C.; Ye, Z. Sedentary behavior patterns and the risk of non-communicable diseases and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 146, 104563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallo, F.R.; Golden, C.; Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Falconer, C.; Toumazou, C. The association between sedentary behaviour, physical activity and type 2 diabetes markers: A systematic review of mixed analytic approaches. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.Z.; Yuan, Y.; Liang, J.H. Association between sedentary behavior, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease-related outcomes in adults-A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1018460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, E.A.; Mendonça, C.R.; Delpino, F.M.; Elias Souza, G.V.; Pereira de Souza Rosa, L.; de Oliveira, C.; Noll, M. Sedentary behavior, physical inactivity, abdominal obesity and obesity in adults and older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 50, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermelink, R.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Markozannes, G.; Tsilidis, K.; Pukrop, T.; Berger, F.; Baurecht, H.; Jochem, C. Sedentary behavior and cancer-an umbrella review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 37, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairag, M.; Alzahrani, S.A.; Alshehri, N.; Alamoudi, A.O.; Alkheriji, Y.; Alzahrani, O.A.; Alomari, A.M.; Alzahrani, Y.A.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Fayraq, A. Exercise as a Therapeutic Intervention for Chronic Disease Management: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e74165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Friedenreich, C.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lee, I.M. Physical inactivity and non-communicable disease burden in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, K.; Fuentes, J.; Márquez, J.L. Physical Inactivity, Sedentary Behavior and Chronic Diseases. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2017, 38, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Durstine, J.L. Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2019, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, E.M. Physical activity, tool for the prevention and management of chronic diseases. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2018, 40, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furrer, R.; Hawley, J.A.; Handschin, C. The molecular athlete: Exercise physiology from mechanisms to medals. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1693–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.L.; Yeo, D.; Kang, C.; Zhang, T. The role of mitochondria in redox signaling of muscle homeostasis. J. Sport. Health Sci. 2020, 9, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, S.; Napolitano, G.; Venditti, P. Mediators of Physical Activity Protection against ROS-Linked Skeletal Muscle Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, S.K.; Schrager, M. Redox signaling regulates skeletal muscle remodeling in response to exercise and prolonged inactivity. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Baker, J.S.; Davison, G.W.; Yan, X. Redox signaling and skeletal muscle adaptation during aerobic exercise. iScience 2024, 27, 109643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, P.A.; Duan, J.; Gaffrey, M.J.; Shukla, A.K.; Wang, L.; Bammler, T.K.; Qian, W.J.; Marcinek, D.J. Fatiguing contractions increase protein S-glutathionylation occupancy in mouse skeletal muscle. Redox Biol. 2018, 17, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furrer, R.; Handschin, C. Molecular aspects of the exercise response and training adaptation in skeletal muscle. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, E.G.; Hawley, J.A.; Hoffman, N.J. Exercise-Regulated Mitochondrial and Nuclear Signalling Networks in Skeletal Muscle. Sports Med. 2024, 54, 1097–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppeler, H. Molecular networks in skeletal muscle plasticity. J. Exp. Biol. 2016, 219, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, I.Y.; Ehrlich, B.E. Signaling in muscle contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a006023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Casas, M.; Jaimovich, E. Energy (and Reactive Oxygen Species Generation) Saving Distribution of Mitochondria for the Activation of ATP Production in Skeletal Muscle. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glancy, B.; Willis, W.T.; Chess, D.J.; Balaban, R.S. Effect of calcium on the oxidative phosphorylation cascade in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 2793–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rius-Pérez, S.; Pérez, S.; Martí-Andrés, P.; Monsalve, M.; Sastre, J. Nuclear Factor Kappa B Signaling Complexes in Acute Inflammation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 33, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gureev, A.P.; Shaforostova, E.A.; Popov, V.N. Regulation of Mitochondrial Biogenesis as a Way for Active Longevity: Interaction Between the Nrf2 and PGC-1α Signaling Pathways. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Shelbayeh, O.; Arroum, T.; Morris, S.; Busch, K.B. PGC-1α Is a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Lifecycle and ROS Stress Response. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogan, J.S. Ubiquitin-like processing of TUG proteins as a mechanism to regulate glucose uptake and energy metabolism in fat and muscle. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1019405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, X.D.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Qu, H.; Zhao, Q.S.; Leng, Y.; Huang, S. Activation of SIK1 by phanginin A regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake by phosphorylating HADC4/5/7 and enhancing GLUT4 expression and translocation. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2025, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaida, S.; Sato, M.; Öberg, A.I.; Dehvari, N.; Olsen, J.M.; Kocan, M.; Halls, M.L.; Merlin, J.; Sandström, A.L.; Csikasz, R.I.; et al. BRL37344 stimulates GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle via β2-adrenoceptors without causing classical receptor desensitization. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2019, 316, R666–R677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, M.; Meng, Z.; Peng, Z.; Liao, Y.; Yang, X.; Nüssler, A.K.; Liu, L.; et al. Gouqi-derived nanovesicles (GqDNVs) inhibited dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy associating with AMPK/SIRT1/PGC1α signaling pathway. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Qian, H.; Tian, D.; Yang, M.; Li, D.; Xu, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Hao, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Linggui Zhugan Decoction activates the SIRT1-AMPK-PGC1α signaling pathway to improve mitochondrial and oxidative damage in rats with chronic heart failure caused by myocardial infarction. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1074837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, P.; Wu, D.; Shi, H. Exercise and exerkines: Mechanisms and roles in anti-aging and disease prevention. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 200, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Gong, L.; Zhang, E.; Wang, X. Exploring exercise-driven exerkines: Unraveling the regulation of metabolism and inflammation. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.T.; Weng, Z.X.; Lin, J.D.; Meng, Z.X. Myokines: Metabolic regulation in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Life Metab. 2024, 3, loae006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Niu, X.; Li, X.; Sun, J.; Ji, Y.; Shang, T.; Gong, L.; et al. Myokine-mediated muscle-organ interactions: Molecular mechanisms and clinical significance. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 242, 117326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, P. Muscle in Endocrinology: From Skeletal Muscle Hormone Regulation to Myokine Secretion and Its Implications in Endocrine-Metabolic Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas, J.R.; Ruiz-Ojeda, F.J.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Nordsborg, N.B.; Martín-Albo, J.; Rueda-Robles, A.; Casuso, R.A. Human muscular mitochondrial fusion in athletes during exercise. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 12087–12098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Rao, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, X.; Jiang, Z.; Xiao, W. Resistance Exercise Improves Glycolipid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle of T2DM Mice via miR-30d-5p/SIRT1/PGC-1α Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Qiu, T.; Wei, G.; Que, Y.; Wang, W.; Kong, Y.; Xie, T.; Chen, X. Role of Histone Post-Translational Modifications in Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 852272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Miao, C. Epigenetic mechanisms of Immune remodeling in sepsis: Targeting histone modification. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorkman, K.K.; Guess, M.G.; Harrison, B.C.; Polmear, M.M.; Peter, A.K.; Leinwand, L.A. miR-206 enforces a slow muscle phenotype. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs243162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townley-Tilson, W.H.; Callis, T.E.; Wang, D. MicroRNAs 1, 133, and 206: Critical factors of skeletal and cardiac muscle development, function, and disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1252–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingzheng, X.; You, W. AMPK/mTOR balance during exercise: Implications for insulin resistance in aging muscle. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2025, 480, 5941–5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouviere, J.; Fortunato, R.S.; Dupuy, C.; Werneck-de-Castro, J.P.; Carvalho, D.P.; Louzada, R.A. Exercise-Stimulated ROS Sensitive Signaling Pathways in Skeletal Muscle. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G. AMPK: A key regulator of energy balance in the single cell and the whole organism. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, S7–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, C.; Ke, C.; Huang, C.; Pan, B.; Wan, C. The activation of AMPK/PGC-1α/GLUT4 signaling pathway through early exercise improves mitochondrial function and mitigates ischemic brain damage. Neuroreport 2024, 35, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odongo, K.; Abe, A.; Kawasaki, R.; Kawabata, K.; Ashida, H. Two Prenylated Chalcones, 4-Hydroxyderricin, and Xanthoangelol Prevent Postprandial Hyperglycemia by Promoting GLUT4 Translocation via the LKB1/AMPK Signaling Pathway in Skeletal Muscle Cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.S.B.; Patil, K.N. trans-ferulic acid attenuates hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and modulates glucose metabolism by activating AMPK signaling pathway in vitro. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, M.M.; Lim, C.Y.; Bi, X.; Robinson, R.C.; Han, W. Tmod3 Phosphorylation Mediates AMPK-Dependent GLUT4 Plasma Membrane Insertion in Myoblasts. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 653557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, M.D. AMP-activated protein kinase and its multifaceted regulation of hepatic metabolism. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2016, 27, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.M.; Xie, Z.F.; Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, X.W.; Zhou, C.D.; Yin, J.P.; Yu, Y.Y.; Cui, S.C.; Jiang, H.W.; Li, T.T.; et al. AMPK activator C24 inhibits hepatic lipogenesis and ameliorates dyslipidemia in HFHC diet-induced animal models. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, J.; Liu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. The New Role of AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Regulating Fat Metabolism and Energy Expenditure in Adipose Tissue. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruas, J.L.; White, J.P.; Rao, R.R.; Kleiner, S.; Brannan, K.T.; Harrison, B.C.; Greene, N.P.; Wu, J.; Estall, J.L.; Irving, B.A.; et al. A PGC-1α isoform induced by resistance training regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell 2012, 151, 1319–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsan, M.; Markworth, J.F.; Watson, G.; Choo, H.C.; Govus, A.; Pham, T.; Hickey, A.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Abbiss, C.R. Regular postexercise cooling enhances mitochondrial biogenesis through AMPK and p38 MAPK in human skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2015, 309, R286–R294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Li, J.L. Role of PGC-1α signaling in skeletal muscle health and disease. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2012, 1271, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, Z.; Zhang, L.F.; Cui, Y.J.; Chang, Y.M.; Jiang, C.W.; Meng, Z.Z.; Xu, P.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Cao, X.B. The Protective Effects of Salidroside from Exhaustive Exercise-Induced Heart Injury by Enhancing the PGC-1 α -NRF1/NRF2 Pathway and Mitochondrial Respiratory Function in Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 876825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theilen, N.T.; Kunkel, G.H.; Tyagi, S.C. The Role of Exercise and TFAM in Preventing Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. J. Cell Physiol. 2017, 232, 2348–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navazani, P.; Vaseghi, S.; Hashemi, M.; Shafaati, M.R.; Nasehi, M. Effects of Treadmill Exercise on the Expression Level of BAX, BAD, BCL-2, BCL-XL, TFAM, and PGC-1α in the Hippocampus of Thimerosal-Treated Rats. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Ward, W.F. PGC-1alpha: A key regulator of energy metabolism. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2006, 30, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Lu, C. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid Mitigates Oxidative Stress and Promotes Differentiation in High Salt-Stimulated Osteoblasts via NOX1 Mediated by PGC-1α. Discov. Med. 2024, 36, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Jia, S.; Yang, Y.; Piao, L.; Wang, Z.; Jin, Z.; Bai, L. Exercise induced meteorin-like protects chondrocytes against inflammation and pyroptosis in osteoarthritis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.W.; Ingham, S.A.; Hunt, J.E.; Martin, N.R.; Pringle, J.S.; Ferguson, R.A. Exercise duration-matched interval and continuous sprint cycling induce similar increases in AMPK phosphorylation, PGC-1α and VEGF mRNA expression in trained individuals. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shad, B.J.; Smeuninx, B.; Atherton, P.J.; Breen, L. The mechanistic and ergogenic effects of phosphatidic acid in skeletal muscle. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hulst, G.; Masschelein, E.; De Bock, K. Resistance exercise enhances long-term mTORC1 sensitivity to leucine. Mol. Metab. 2022, 66, 101615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buel, G.R.; Dang, H.Q.; Asara, J.M.; Blenis, J.; Mutvei, A.P. Prolonged deprivation of arginine or leucine induces PI3K/Akt-dependent reactivation of mTORC1. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maracci, C.; Motta, S.; Romagnoli, A.; Costantino, M.; Perego, P.; Di Marino, D. The mTOR/4E-BP1/eIF4E Signalling Pathway as a Source of Cancer Drug Targets. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3501–3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, A.; Aashaq, S.; Andrabi, K.I. Reappraisal to the study of 4E-BP1 as an mTOR substrate—A normative critique. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 96, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Liang, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Lv, J.; Chen, N. Exercise-Induced Autophagy Suppresses Sarcopenia Through Akt/mTOR and Akt/FoxO3a Signal Pathways and AMPK-Mediated Mitochondrial Quality Control. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 583478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, N.X.Y.; Kaczmarek, A.; Hoque, A.; Davie, E.; Ngoei, K.R.W.; Morrison, K.R.; Smiles, W.J.; Forte, G.M.; Wang, T.; Lie, S.; et al. mTORC1 directly inhibits AMPK to promote cell proliferation under nutrient stress. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayo, A.; Segovia, R.; Venturini, W.; Moore-Carrasco, R.; Valenzuela, C.; Brown, N. mTOR Activity and Autophagy in Senescent Cells, a Complex Partnership. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Lu, C.; Sang, K. Exercise as a Metabolic Regulator: Targeting AMPK/mTOR-Autophagy Crosstalk to Counteract Sarcopenic Obesity. Aging Dis. 2025, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, P.K.; Mahapatra, K.K.; Singh, A.; Bhutia, S.K. mTOR inhibitors in targeting autophagy and autophagy-associated signaling for cancer cell death and therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden-Foncea, H.; Raymackers, J.M.; Deldicque, L.; Renard, P.; Francaux, M. TLR2 and TLR4 activate p38 MAPK and JNK during endurance exercise in skeletal muscle. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.W.; Wilborn, C.D.; Kreider, R.B.; Willoughby, D.S. Effects of resistance exercise intensity on extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chang, F.; Li, F.; Fu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Yin, D. Palmitate promotes autophagy and apoptosis through ROS-dependent JNK and p38 MAPK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 463, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.E.; Bhagwan Bhosale, P.; Kim, H.H.; Park, M.Y.; Abusaliya, A.; Kim, G.S.; Kim, J.A. Apigetrin Abrogates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation in L6 Skeletal Muscle Cells through NF-κB/MAPK Signaling Pathways. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Lei, X.; Zhang, Q. Moderate activation of IKK2-NF-kB in unstressed adult mouse liver induces cytoprotective genes and lipogenesis without apparent signs of inflammation or fibrosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, F.; Lu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Zhong, J.; Li, Q.; Shao, X. Polydatin inhibited TNF-α-induced apoptosis of skeletal muscle cells through AKT-mediated p38 MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2023, 42, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, T.; Takei, M.; Ogasawara, J.; Watanabe, N.; Sanpei, M.; Yoshida, M.; Nakae, D.; Sakurai, T.; Nakano, N.; Kizaki, T.; et al. Exercise training enhances tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced expressions of anti-apoptotic genes without alterations in caspase-3 activity in rat epididymal adipocytes. Jpn. J. Physiol. 2005, 55, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.A.C.; Veras, A.S.C.; Batista, V.R.G.; Tavares, M.E.A.; Correia, R.R.; Suggett, C.B.; Teixeira, G.R. Physical exercise and the functions of microRNAs. Life Sci. 2022, 304, 120723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharples, A.P.; Turner, D.C. Skeletal muscle memory. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 324, C1274–C1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrón-Cabrera, E.; Ramos-Lopez, O.; González-Becerra, K.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Milagro, F.I.; Martínez-López, E.; Martínez, J.A. Epigenetic Modifications as Outcomes of Exercise Interventions Related to Specific Metabolic Alterations: A Systematic Review. Lifestyle Genom. 2019, 12, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Pinilla, F.; Thapak, P. Exercise epigenetics is fueled by cell bioenergetics: Supporting role on brain plasticity and cognition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 220, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bo, H.; Zhang, Y. Endurance exercise-induced histone methylation modification involved in skeletal muscle fiber type transition and mitochondrial biogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, B.I.; Ismaeel, A.; Long, D.E.; Depa, L.A.; Coburn, P.T.; Goh, J.; Saliu, T.P.; Walton, B.J.; Vechetti, I.J.; Peck, B.D.; et al. Extracellular vesicle transfer of miR-1 to adipose tissue modifies lipolytic pathways following resistance exercise. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e182589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Cheing, G.L.Y.; Cheung, A.K.K. Role of exosomes and exosomal microRNA in muscle-Kidney crosstalk in chronic kidney disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 951837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Júnior, J.M.; Ferreira, S.M.; Kurauti, M.A.; Bernstein, D.L.; Ruano, E.G.; Kameswaran, V.; Schug, J.; Freitas-Dias, R.; Zoppi, C.C.; Boschero, A.C.; et al. Paternal Exercise Improves the Metabolic Health of Offspring via Epigenetic Modulation of the Germline. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axsom, J.E.; Libonati, J.R. Impact of parental exercise on epigenetic modifications inherited by offspring: A systematic review. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, H.R.; Yan, Z. AMPK and the Adaptation to Exercise. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2022, 84, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjøbsted, R.; Hingst, J.R.; Fentz, J.; Foretz, M.; Sanz, M.N.; Pehmøller, C.; Shum, M.; Marette, A.; Mounier, R.; Treebak, J.T.; et al. AMPK in skeletal muscle function and metabolism. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1741–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, V.A.; Benton, C.R.; Yan, Z.; Bonen, A. PGC-1alpha regulation by exercise training and its influences on muscle function and insulin sensitivity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E145–E161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, J.; Kiilerich, K.; Pilegaard, H. PGC-1alpha-mediated adaptations in skeletal muscle. Pflugers Arch. 2010, 460, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.; Kim, K. Exercise-induced PGC-1α transcriptional factors in skeletal muscle. Integr. Med. Res. 2014, 3, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, D.A.; Lessard, S.J.; Coffey, V.G. mTOR function in skeletal muscle: A focal point for overnutrition and exercise. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, M.S. mTOR as a Key Regulator in Maintaining Skeletal Muscle Mass. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, H.F.; Goodyear, L.J. Exercise, MAPK, and NF-kappaB signaling in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007, 103, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.L. Nuclear factor κB signaling revisited: Its role in skeletal muscle and exercise. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 232, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W.; Chang, S.J. Moderate Exercise Suppresses NF-κB Signaling and Activates the SIRT1-AMPK-PGC1α Axis to Attenuate Muscle Loss in Diabetic db/db Mice. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Yin, X.; Cao, Q.; Huang, K.; Deng, Z.; Cao, J. miRNAs involved in the regulation of exercise fatigue. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1614942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, C.; Zonefrati, R.; Sharma, P.; Innocenti, M.; Cianferotti, L.; Brandi, M.L. Characterization of Skeletal Muscle Endocrine Control in an In Vitro Model of Myogenesis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2020, 107, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle-Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 594–609, Erratum in Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, C.A.Z.; Sierra, A.P.R.; Martínez Galán, B.S.; Maciel, J.F.S.; Manoel, R.; Barbeiro, H.V.; de Souza, H.P.; Cury-Boaventura, M.F. Time Course and Role of Exercise-Induced Cytokines in Muscle Damage and Repair After a Marathon Race. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 752144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ibraheem, A.M.T.; Hameed, A.A.Z.; Marsool, M.D.M.; Jain, H.; Prajjwal, P.; Khazmi, I.; Nazzal, R.S.; Al-Najati, H.M.H.; Al-Zuhairi, B.H.Y.K.; Razzaq, M.; et al. Exercise-Induced cytokines, diet, and inflammation and their role in adipose tissue metabolism. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, D.; Hughes, M.G.; Butcher, L.; Aicheler, R.; Smith, P.; Cullen, T.; Webb, R. IL-6 signaling in acute exercise and chronic training: Potential consequences for health and athletic performance. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023, 33, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringleb, M.; Javelle, F.; Haunhorst, S.; Bloch, W.; Fennen, L.; Baumgart, S.; Drube, S.; Reuken, P.A.; Pletz, M.W.; Wagner, H.; et al. Beyond muscles: Investigating immunoregulatory myokines in acute resistance exercise—A systematic review and meta-analysis. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazeminasab, F.; Marandi, S.M.; Ghaedi, K.; Safaeinejad, Z.; Esfarjani, F.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H. A comparative study on the effects of high-fat diet and endurance training on the PGC-1α-FNDC5/irisin pathway in obese and nonobese male C57BL/6 mice. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrann, C.D.; White, J.P.; Salogiannnis, J.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; Wu, J.; Ma, D.; Lin, J.D.; Greenberg, M.E.; Spiegelman, B.M. Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1α/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenmoehl, J.; Ohde, D.; Albrecht, E.; Walz, C.; Tuchscherer, A.; Hoeflich, A. Browning of subcutaneous fat and higher surface temperature in response to phenotype selection for advanced endurance exercise performance in male DUhTP mice. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2017, 187, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gil, A.M.; Elizondo-Montemayor, L. The Role of Exercise in the Interplay between Myokines, Hepatokines, Osteokines, Adipokines, and Modulation of Inflammation for Energy Substrate Redistribution and Fat Mass Loss: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikooie, R.; Jafari-Sardoie, S.; Sheibani, V.; Nejadvaziri Chatroudi, A. Resistance training-induced muscle hypertrophy is mediated by TGF-β1-Smad signaling pathway in male Wistar rats. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 5649–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichtel, L.E.; Kimball, A.; Bollinger, B.; Scarff, G.; Gerweck, A.V.; Bredella, M.A.; Haines, M.S. Higher serum myostatin levels are associated with lower insulin sensitivity in adults with overweight/obesity. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e16169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Liang, B. Different Fasting Methods Combined With Running Exercise Regulate Glucose Metabolism via AMPK/SIRT1/BDNF Pathway in Mice. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15, e70031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K. Physical activity and muscle-brain crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawliuk, T.; Thrones, M.; Cordingley, D.M.; Cornish, S.M.; Greening, S.G. Promoting brain health and resilience: The effect of three types of acute exercise on affect, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and heart rate variability. Behav. Brain Res. 2025, 493, 115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Sherrier, M.; Li, H. Skeletal Muscle and Bone—Emerging Targets of Fibroblast Growth Factor-21. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 625287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.A.; Du, M.; Son, J.S.; Zhu, M.J. Exercise improves homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium by activation of apelin receptor-AMP-activated protein kinase signalling. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 2371–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpiö, T.; Skarp, S.; Perjés, Á.; Swan, J.; Kaikkonen, L.; Saarimäki, S.; Szokodi, I.; Penninger, J.M.; Szabó, Z.; Magga, J.; et al. Apelin regulates skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise in a high-intensity interval training model. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2024, 326, C1437–C1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, F.; Lachinani, L.; Ghaedi, S.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H.; Megraw, T.L.; Ghaedi, K. New insights into the cellular activities of Fndc5/Irisin and its signaling pathways. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Deng, K.Q.; Lu, C.; Fu, X.; Zhu, Q.; Wan, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Nie, L.; Cai, H.; et al. Interleukin-6 classic and trans-signaling utilize glucose metabolism reprogramming to achieve anti- or pro-inflammatory effects. Metabolism 2024, 155, 155832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymochko-Voloshyn, R.; Hashchyshyn, V.; Paraniak, N.; Boretsky, V.; Reshetylo, S.; Boretsky, Y. Myokines are one of the key elements of interaction between skeletal muscles and other systems of human body necessary for adaptation to physical loads. Visnyk Lviv. Univ. 2023, 88, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, A.; Zhou, M.; Croucher, P.I. ADAM-9 (MDC-9/meltrin-gamma), a member of the a disintegrin and metalloproteinase family, regulates myeloma-cell-induced interleukin-6 production in osteoblasts by direct interaction with the alpha(v)beta5 integrin. Blood 2006, 107, 3271–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safdar, A.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Exosomes as Mediators of the Systemic Adaptations to Endurance Exercise. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 8, a029827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabaratnam, R.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.P.; Højlund, K. Factors mediating exercise-induced organ crosstalk. Acta Physiol. 2022, 234, e13766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudice, J.; Taylor, J.M. Muscle as a paracrine and endocrine organ. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2017, 34, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughey, C.C.; Bracy, D.P.; Rome, F.I.; Goelzer, M.; Donahue, E.P.; Viollet, B.; Foretz, M.; Wasserman, D.H. Exercise training adaptations in liver glycogen and glycerolipids require hepatic AMP-activated protein kinase in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E14–E28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.R.; Habibi, M.; Ferguson, D.; Brookheart, R.T.; Thyfault, J.P.; Meyer, G.A.; Lantier, L.; Hughey, C.C.; Finck, B.N. Disruption of Hepatic Mitochondrial Pyruvate and Amino Acid Metabolism Impairs Gluconeogenesis and Endurance Exercise Capacity in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 326, E515–E527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arad, A.D.; DiMenna, F.J.; Kittrell, H.D.; Kissileff, H.R.; Albu, J.B. Whole body lipid oxidation during exercise is impaired with poor insulin sensitivity but not with obesity per se. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 323, E366–E377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekeres, R.; Priksz, D.; Bombicz, M.; Pelles-Tasko, B.; Szilagyi, A.; Bernat, B.; Posa, A.; Varga, B.; Gesztelyi, R.; Somodi, S.; et al. Exercise Types: Physical Activity Mitigates Cardiac Aging and Enhances Mitochondrial Function via PKG-STAT3-Opa1 Axis. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 3040–3054. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, T.; Yu, J.; Li, S.; Gong, L.; Zhang, Y. FGF21: A Sharp Weapon in the Process of Exercise to Improve NAFLD. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2023, 28, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa Maheshvare, M.; Raha, S.; König, M.; Pal, D. A pathway model of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the pancreatic β-cell. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1185656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Khan, D.; Dubey, V.; Tarasov, A.I.; Flatt, P.R.; Irwin, N. Comparative Effects of GLP-1 and GLP-2 on Beta-Cell Function, Glucose Homeostasis and Appetite Regulation. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.S.; Ng, C.F.; Pang, B.P.S.; Hang, M.; Tse, M.C.L.; Iu, E.C.Y.; Ooi, X.C.; Yang, X.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, C.W.; et al. Exercise-induced BDNF promotes PPARδ-dependent reprogramming of lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle during exercise recovery. Sci. Signal. 2024, 17, eadh2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.Y. Aerobic Exercise Increases Meteorin-like Protein in Muscle and Adipose Tissue of Chronic High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 6283932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.D.; Boström, P.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Schinzel, R.T.; Lewis, G.D.; Dejam, A.; Lee, Y.K.; Palma, M.J.; Calhoun, S.; Georgiadi, A.; et al. β-Aminoisobutyric acid induces browning of white fat and hepatic β-oxidation and is inversely correlated with cardiometabolic risk factors. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, H.; Ge, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, H.; Dong, Y. Irisin promotes the browning of white adipocytes tissue by AMPKα1 signaling pathway. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza-Salinas, A.; González-Jurado, J.; Molina-Sotomayor, E.; Fuentes-Barría, H.; Farías Valenzuela, C.; Arenas-Sánchez, G. Mobilization, transport and oxidation of fatty acids: Physiological mechanisms associated with weight loss. J. Sport Health Res. 2020, 12, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Herold, F.; Ludyga, S.; Kuang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Erickson, K.I.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Cheval, B.; et al. Physical activity, cathepsin B, and cognitive health. Trends Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henselmans, M.; Bjørnsen, T.; Hedderman, R.; Vårvik, F.T. The Effect of Carbohydrate Intake on Strength and Resistance Training Performance: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandova, T.; Buendía-Romero, A.; Polanska, H.; Hola, V.; Rihova, M.; Vetrovsky, T.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Steffl, M. Long-Term Effect of Exercise on Irisin Blood Levels-Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettariga, F.; Taaffe, D.R.; Galvão, D.A.; Lopez, P.; Bishop, C.; Markarian, A.M.; Natalucci, V.; Kim, J.S.; Newton, R.U. Exercise training mode effects on myokine expression in healthy adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Sport. Health Sci. 2024, 13, 764–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminasab, F.; Sadeghi, E.; Afshari-Safavi, A. Comparative Impact of Various Exercises on Circulating Irisin in Healthy Subjects: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 8235809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vints, W.A.J.; Gökçe, E.; Langeard, A.; Pavlova, I.; Çevik, Ö.S.; Ziaaldini, M.M.; Todri, J.; Lena, O.; Shalom, S.B.; Jak, S.; et al. Investigating the mediating effect of myokines on exercise-induced cognitive changes in older adults: A living systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 178, 106381, Erratum in Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 179, 106405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, M.; Maleki, A.H.; Symonds, M.E.; Sakhaei, M.H.; Rosenkranz, S.K.; Ehsanifar, M.; Korivi, M.; Liu, Y. Interleukin-15 responses to acute and chronic exercise in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1288537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torabi, A.; Reisi, J.; Kargarfard, M.; Mansourian, M. Differences in the Impact of Various Types of Exercise on Irisin Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 15, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.F.; Thyfault, J.P. Exercise-Pharmacology Interactions: Metformin, Statins, and Healthspan. Physiology 2020, 35, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P.L.; Castillo-García, A.; Saco-Ledo, G.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Lucia, A. Physical exercise: A polypill against chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2024, 39, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cento, A.S.; Leigheb, M.; Caretti, G.; Penna, F. Exercise and Exercise Mimetics for the Treatment of Musculoskeletal Disorders. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2022, 20, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokrywka, A.; Cholbinski, P.; Kaliszewski, P.; Kowalczyk, K.; Konczak, D.; Zembron-Lacny, A. Metabolic modulators of the exercise response: Doping control analysis of an agonist of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor δ (GW501516) and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR). J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 65, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misquitta, N.S.; Ravel-Chapuis, A.; Jasmin, B.J. Combinatorial treatment with exercise and AICAR potentiates the rescue of myotonic dystrophy type 1 mouse muscles in a sex-specific manner. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ref. | Pathway | Primary Activators During Exercise | Key Molecular Targets | Molecular and Physiological Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [94,95] | AMPK | Increased AMP/ATP ratio, calcium flux and ROS | LKB1, CaMKKβ, ACC, CPT1, GLUT4, PGC-1α | Energy, oxidation and biogenesis |

| [61,96,97,98] | PGC-1α | AMPK, SIRT1, p38 MAPK Activation and endurance exercise | NRF1/2, ERRα, TFAM, VEGF | Mitochondria, oxidation and angiogenesis |

| [99,100] | mTOR | Mechanical overload, amino acids (leucine) and insulin/Akt signaling | S6K1, 4E-BP1, Raptor, PI3K/Akt | Synthesis, hypertrophy and anabolism |

| [80,83,101] | MAPK | Mechanical stress, cytokines and ROS | ERK1/2, JNK, p38 MAPK | Stress, cytokines and remodeling |

| [66,83,102,103] | NF-κB | ROS, cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and metabolic stress | IKK complex, IκB degradation | Inflammation, redox and modulation |

| [87,89,90] | Epigenetic Regulation | Repeated muscle contraction and metabolic flux | DNA methyltransferases, histone acetyltransferases (HATs), SIRT1 | Hypomethylation, acetylation and gene expression |

| [46,47,104] | microRNA | Muscle contraction, calcium signaling and oxidative stress | MyomiRs (miR-1, miR-133a/b, miR-206) | Myogenesis and mitochondria signaling |

| Author (Ref.) | Population | Exercise Type | Outcomes (95% CI) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ringleb [110] | Healthy adults | Resistance | IL-6: 0.45 (0.29 to 0.61) IL-10: 0.14 (−0.09 to 0.36) | Acute inflammatory response |

| Jandová [144] | Healthy adults | Aerobics + resistance | Irisin: 0.39 (0.27 to 0.52) | Irisin increases |

| Bettariga [145] | Healthy adults | Aerobics + resistance | IL-15: 0.95 (−0.23 to 2.13) Irisin: 0.44 (−0.04 to 0.91) Secreted Acidic Protein and Rich in Cysteine 0.32 (−0.06 to 0.69) Oncostatin M: 0.08 (−2.40 to 2.56) Decorin: 0.99 (−11.14 to 13.12) | Evidence limited |

| Kazeminasab [146] | Adults | Aerobics and Anaerobic | Irisin overall: 0.15 (−0.35 to 0.65) | Irisin changes minimally |

| Vints [147] | Healthy adults | Chronic exercise | Neurotrophic factors: 0.427 (0.127–0.728) Pro-inflammatory factors: −0.013 (−0.316 to 0.290) Anti-inflammatory factors: 0.009 (−0.551–0.569) BDNF: 0.427 (0.127 to 0.728) Neurotrophin-3: 1.221 (0.213–2.228) | Exercise increases neurotrophins |

| Khalafi [148] | Healthy trained adults | Acute And chronic | Acute exercise IL-15: 0.90 (0.47 to 1.32) Chronic exercise IL-15: 0.002 (−0.51 to 0.51) | IL-15 shows variability |

| Torabi [149] | Adults with Overweight and obesity | Exercise Combined | Irisin: 0.957 (0.535–1.379) | Obesity modulates irisin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fuentes-Barría, H.; Aguilera-Eguía, R.; Alarcón-Rivera, M.; López-Soto, O.; Aristizabal-Hoyos, J.A.; Roco-Videla, Á.; Caviedes-Olmos, M.; Rojas-Gómez, D. Exercise-Induced Molecular Adaptations in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases—Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12096. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412096

Fuentes-Barría H, Aguilera-Eguía R, Alarcón-Rivera M, López-Soto O, Aristizabal-Hoyos JA, Roco-Videla Á, Caviedes-Olmos M, Rojas-Gómez D. Exercise-Induced Molecular Adaptations in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases—Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12096. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412096

Chicago/Turabian StyleFuentes-Barría, Héctor, Raúl Aguilera-Eguía, Miguel Alarcón-Rivera, Olga López-Soto, Juan Alberto Aristizabal-Hoyos, Ángel Roco-Videla, Marcela Caviedes-Olmos, and Diana Rojas-Gómez. 2025. "Exercise-Induced Molecular Adaptations in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases—Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12096. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412096

APA StyleFuentes-Barría, H., Aguilera-Eguía, R., Alarcón-Rivera, M., López-Soto, O., Aristizabal-Hoyos, J. A., Roco-Videla, Á., Caviedes-Olmos, M., & Rojas-Gómez, D. (2025). Exercise-Induced Molecular Adaptations in Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases—Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12096. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412096