Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is neuropathologically characterized by tau-immunopositive neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and amyloid-β (Aβ)-immunopositive senile plaques. According to the widely accepted amyloid cascade hypothesis, Aβ pathology represents the upstream event in AD pathophysiology and induces tau aggregation. However, numerous studies have suggested that tau aggregates correlate more closely with neuronal loss and regional brain atrophy than with Aβ depositions. Tau aggregation in AD demonstrates a hierarchical spreading pattern beginning in the transentorhinal cortex, but the mechanisms underlying this spreading manner of lesions remain to be elucidated. This review aims to address current controversies regarding tau pathology in AD from the perspectives of both the ‘amyloid cascade’ and ‘tauopathy’ hypotheses. From the ‘amyloid cascade’ viewpoint, Aβ deposition prominently involves distal axon and axon terminals, and in some regions, there are anatomical correspondences between axonal Aβ pathology and cytoplasmic tau aggregations (e.g., a close relationship between senile plaques in the molecular layer of the hippocampal dentate gyrus and NFTs in the transentorhinal cortex). Nevertheless, this model cannot explain the whole body of hierarchical spreading of tau aggregation because notable spaciotemporal discrepancies also exist in many regions. From the ‘tauopathy’ perspective, the distribution of tau aggregates in AD involves key nodes within the memory circuits. Also, experimental studies have suggested that patient-derived tau exhibits seeding and neuron-to-neuron propagation properties. Interestingly, tau aggregation in AD appears to spread laterally in a proximity-dependent, cortico-cortical fashion rather than along long-range memory circuits. This contrasts with the system-selective, poly-nodal degenerations seen in four-repeat tauopathies, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or spinocerebellar degenerations. Moreover, the proportions of three-repeat and four-repeat isoforms shift during the maturation of NFTs in AD. Overall, spreading patterns of tau-pathology in AD cannot be fully explained by Aβ pathology and also differ from the system degeneration seen in other tauopathies.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) encompasses a clinical and neuropathological entity that corresponds to the syndrome of Alzheimer’s type dementia. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that Alzheimer’s disease contributes to 60–70% of dementia cases, and a world-wide surveillance effort revealed an increased prevalence of Alzheimer’s type dementia for the last 30 years even when the ages are standardized [1]. Following clinical studies from the US, Alzheimer’s type dementia and related cognitive impairment occur in 10% or more among the population > 65 years; the burden is estimated at USD 627 billion in aggregate [2]. The social impact of this disease is severe and growing.

In 1907, Alois Alzheimer first reported the clinical and postmortem findings of a 51-year-old female patient who presented with delusional jealousy and progressive dementia, and who was autopsied four and half years after syndrome onset [3]. His work addressed the two essential neuropathological hallmarks of AD: neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the neurons, identified by Bielschowsky silver impregnation, and senile plaques in the neuropil, of which he particularly emphasized the former. Around the same time, neuritic plaques associated with abnormal neurites were clearly described by Oskar Fischer [4]. Although senile plaques had been already described earlier by Blocq and Marinesco and by Redlich, their pathogenic significance remained uncertain [5,6].

Today, NFTs are known to consist of intraneuronal aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau, while senile plaques are extracellular deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ) that are surrounded by dystrophic neurites. The widely accepted ‘amyloid cascade’ hypothesis positions Aβ as the initiating event of AD-pathogenesis, acting as the upstream driver of tau aggregation and subsequent neurodegeneration [7,8]. Biomarkers that reflect dynamics of these pathologic proteins, including tracing of tau and Aβ with positron emission tomography (PET) and measurement of phosphorylated tau (e.g., p-tau 181, p-tau 217) and Aβ levels in plasma or cerebrospinal fluid [9,10,11], demonstrate reliable correlations with disease progression.

Postmortem studies have clarified that the spreading of tau aggregates follows a stereotyped hierarchical progression, starting in the transentorhinal cortex and advancing through the hippocampus to widespread neocortical regions [12]. Aβ deposits also exhibit a characteristic spreading manner, which is thought to originate in various cortical areas [13]. From the perspective of the amyloid cascade, the spatial distribution of tau aggregates would therefore be expected to follow that of Aβ deposition, based on the anatomical relationships between cytoplasm (tau) and neuritic (Aβ) pathology. Otherwise, a tau-autonomous mechanism may also contribute to the spreading of tau-aggregates, independent of Aβ. Neuronal loss and the spread of tau aggregates preferentially involve specific nodes of memory-related circuits, suggesting that AD may represent a form of ‘system degeneration’ involving memory networks. The selective vulnerability of certain neuroanatomical systems may reflect the propagation of neurotoxic protein aggregates, excitotoxicity associated with system-specific neurotransmitters, or intrinsic cellular vulnerabilities [14,15].

Nevertheless, critical gaps remain in our understanding of AD pathogenesis. In particular, the following two points are unresolved: (1) the nature and cause of the spaciotemporal discrepancies between Aβ and tau pathologies; and (2) whether the spreading manner of tau aggregation really reflects a system degeneration of memory circuits. This review first provides an overview of the neuropathological findings of AD and then discusses the controversies about tau pathology in AD from the perspectives of ‘amyloid cascade’ and ‘tauopathy’.

List of chapters:

- Introduction

- Aβ and Tau Pathology in AD

- 2.2

- Neuropathology of AD

- 2.3

- Is Tau a Bystander of Aβ in AD Pathology?

- Controversies of Tau Pathology in AD

- 3.1

- Spatiotemporal Discrepancy Between Senile Plaque and NFTs in the Human Brain, from the Viewpoint of the ‘Amyloid Cascade’

- 3.2

- Is AD a System Degeneration of Memory Circuits? From the Viewpoint of ‘Tauopathy’

- Conclusions

2. Aβ and Tau Pathology in AD

2.1. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease

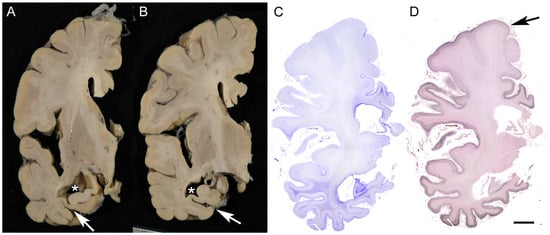

Brains of AD patients exhibit characteristic atrophy of the parahippocampal gyrus (including the entorhinal and transentorhinal areas) and of the hippocampus. In advanced stages, diffuse cortical atrophy becomes evident (Figure 1). Microscopically, AD pathology is characterized by a combination of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and senile plaques. The current diagnostic criteria require the severity of both NFTs and Aβ deposits to be above cutoff, and for Aβ, the presence of neuritic plaques on silver impregnation or thioflavin is mandatory [16]. This combined assessment of NFT and senile plaques arises from the fact that neither NFTs nor senile plaques alone can reliably distinguish AD from normal aging. Although Braak and colleagues established immunohistochemical staging of NFTs on the basis of a large autopsy sample size, their study did not include clinicopathological correlations [17]. Similarly, while the burden of senile plaques correlates with AD pathology, it often lacks a distinct boundary separating AD from age-related changes [18].

Figure 1.

Macroscopic finding of AD brain. The panels show an AD case with a clinical duration of 8 years; the patient died at the age of 79. (A,B) The parahippocampal gyrus and hippocampus exhibit marked atrophy in association with dilatation of the lateral ventricle (*) and collateral sulcus (arrows). The atrophy is prominent in the posterior portion (B). (C,D) Pronounced astrogliosis is observed on Holzer staining (C), and strong argyrophilicity is evident on Gallyas silver impregnation (D) in the medial temporal areas and limbic cortices, showing decreasing gradient toward the frontal cortices with relative preservation of the precentral gyrus (arrow). Scale bar = 1 cm.

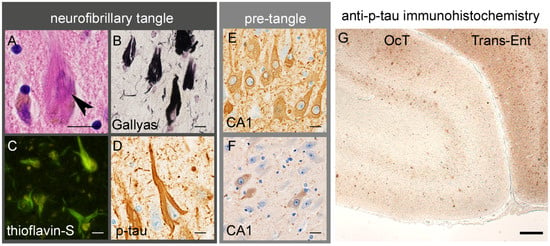

NFTs are flame-shaped, filamentous intraneuronal inclusions which are strongly labeled with silver impregnation and thioflavin (Figure 2). NFTs are dense aggregations of hyperphosphorylated tau that are composed of fibrils, ultrastructurally termed paired-helical filaments [19]. Early-stage lesions often exhibit diffuse and amorphous tau immunopositivity in the neuronal cytoplasm but lack a defined tangle structure or argyrophilicity, known as “pre-tangles”. Pre-tangles are considered to represent the early phase of tau aggregation, dominated by tau oligomers rather than mature fibrils [20,21] (Figure 2). Tau also aggregates within the neurites, forming neuropil threads, which can be identified in macroscopic observations of tau-immunostained preparations in severely affected regions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Tau aggregation in AD. (A–D) Neurofibrillary tangles (A, arrowhead) are argyrophilic and thioflavin-positive cytoplasmic inclusions, mainly composed of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau). (E) Pretangles are diffuse cytoplasmic tau aggregates, often showing strong immunoreactivity along the nuclear membrane. (F) Anti-tau-oligomer-specific immunohistochemistry recognizes pretangles. (G) In AD, dense tau aggregation in the neuronal cytoplasm and neurites results in a layer-specific pattern of immunostaining in the transentorhinal (Trans-Ent) cortex, one of the earliest sites of cerebral lesions, and to a lesser extent in the occipitotemporal (OCT) cortex. Scale bars: (A–F) 10 μm and (G) 100 μm. (D,E,G) Anti-p-tau (clone AT8, mouse monoclonal, 1:3000, Waltham, MA, USA) and (F) anti-tau oligomer (clone 2D6-2C6, rat monoclonal, 1:100 [20]) antibodies.

Tau is encoded by the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene, and alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10 yields six isoforms of tau [22]. These tau isoforms are largely classified into two groups: three-repeat (3R) isoforms lacking exon 10, and four-repeat (4R) isoforms containing exon 10 [23]. Both 3R and 4R isoforms are present in the NFTs of AD; pure 4R aggregates are observed in progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration (CBD), whereas pure three-repeat aggregates are typical of Pick body disease [24,25]. The hierarchical distribution of tau pathology progression, as shown by Braak et al., demonstrates initial involvement of the transentorhinal area of the parahippocampal gyrus, and spreads to the entorhinal area and hippocampus (Braak stages I–II), then lateral and superior temporal gyri (stages III–IV), followed by widespread neocortices (stages V–VI) [12,17].

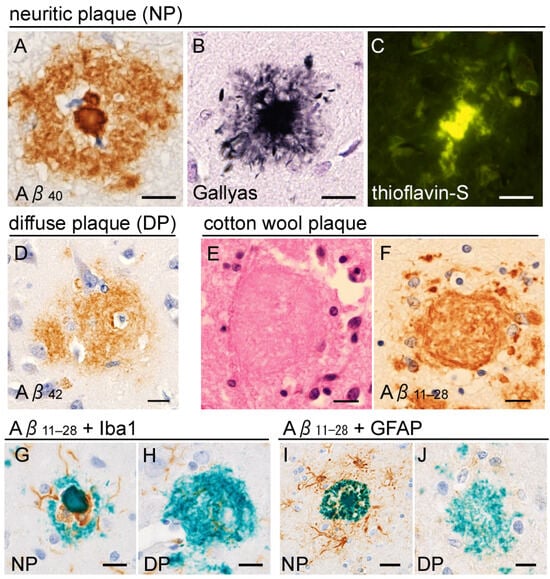

Senile plaque is characterized by the deposition of Aβ in the neuropil, in the form of extracellular deposits that presumably interact closely with the neuronal and glial membranes [26]. Although the classification of senile plaques has been complicated because of methodological differences (e.g., anti-Aβ immunohistochemistry, thioflavin, or silver impregnations), anti-Aβ immunostaining is largely classified into two major types: neuritic plaques and diffuse plaques (Figure 3). Neuritic plaques comprise a dense amyloid core surrounded by a fuzzy halo. Argyrophilic and thioflavin-positive dystrophic neurites form a crown around the amyloid core, and some of them contain tau aggregates. The core and crown can be identified by hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining. In contrast, diffuse plaques are fuzzy deposits, lacking distinct core and crown structures. Diffuse plaques are hardly detectable on H&E staining and show weak or no positivity on silver impregnation, although the Campbell–Switzer method recognizes diffuse plaques well. Familial AD associated with presenilin-1 (PSEN1) or amyloid precursor protein (APP) mutations may also contain cotton wool plaques that are characterized with a clear boundary but lack core/crown structures. Cotton wool plaques are quite exceptional among sporadic cases [27]. APP is cleaved by β-secretase at its N-terminus and by γ-secretase (which includes PSEN1) at its C-terminus, generating several Aβ species of different molecular weights. Aβ40 predominates in neuritic plaques, particularly within the amyloid core, whereas Aβ42 is enriched in diffuse plaques [28].

Figure 3.

Senile plaques. (A–D) Neuritic plaques (NPs) are Aβ deposits within the neuropil, characterized by a dense core and peripheral halo (A). Anti-Aβ40 immunohistochemistry clearly labels the plaque core (A). The core is surrounded by strongly argyrophilic (B) and thioflavin-S-positive (C) crowns, composed of dystrophic neurites. (D) Diffuse plaques (DPs) are Aβ42-rich and lack the distinct core and crown structures. (E,F) Cotton wool plaques observed in a PSEN1-mutated case are shown (mutated site is not available in this case). They lack a core and crown but display a well-defined boundary, different from diffuse plaques. (G,H) Anti-Iba1 immunohistochemistry reveals microglial infiltration within the space between the core and halo (G), which is not observed in diffuse plaque (H). (I,J) Anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunohistochemistry shows that astroglia are prominent around the neuritic plaques, rather than inside. Scale bars (A–J) 10 μm. (A) Anti-Aβ40 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:500, IBL, Gunma, Japan), (D) anti-Aβ42 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:500, IBL), and (F–J) anti-Aβ11–28 (clone 12B2, mouse monoclonal, 1:1000, IBL) antibodies.

There is a hypothesis that diffuse and neuritic plaques are on a pathological continuum, corresponding to disease progression in AD. Neuropathological studies have reported that preclinical or early AD cases are associated with a diffuse plaque-dominant state, whereas advanced AD cases are associated with a neuritic plaque-dominant state [29,30]. Supportively, a basic study using APP-transgenic (tg) mice has clarified that Aβ deposition precedes neuritic swelling, and the neuritic changes were ameliorated after anti-Aβ immunotherapy [31]. However, controversies may exist in the interpretation of plaque subtypes; an exogeneous Aβ-injection into APP-tg models has revealed that the morphological subtypes of Aβ deposits depend on both the host and source of the agent, suggesting the presence of distinct Aβ strains with variable biological activities [32].

It is also known that neuritic plaques often attract glial cells, particularly microglia, whereas diffuse plaques do not [33] (Figure 3). These findings emphasize the importance of neuroinflammation in Aβ-related pathology in AD. Disease-associated microglia may act as sensors of neuronal damage, initiating inflammatory cascades [34]. Nevertheless, the question of whether plaque-associated microglia are merely reactive or actively drive plaque-induced neurodegeneration remains controversial [35].

The severity and distribution of tau pathology are more strongly correlated with brain atrophy and the clinical presentation of AD than Aβ deposition, though Aβ pathology may have synergistic effects with tau-derived neuronal damage [5,32,36,37]. Tau and Aβ PET scan studies have confirmed that tau pathology has a higher correlation than Aβ pathology with cognitive status and its evolution [38]. Basic studies also revealed that a reduction in endogenous tau resulted in rescuing neurodegenerative phenotypes in an APP-mutant model, highlighting the pivotal role of tau in AD pathophysiology [39,40].

2.2. Is Tau a Bystander of Aβ in AD Pathology?

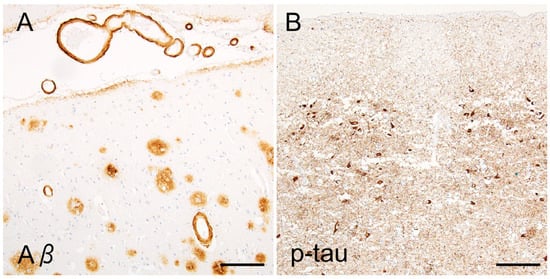

The concept of the amyloid cascade is widely accepted as an explanation of AD pathogenesis. In brief, it proposes that an increased Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and subsequent plaque formation are crucial for AD pathogenesis. In this theory, tau aggregation is considered to be a downstream event of Aβ deposition. Indeed, clinical and neuropathological findings support this hypothesis. Mutations in PSEN and APP are causative of familial AD, and importantly, these mutations are associated not only with Aβ deposits but also with severe NFT pathology. Actually, the original case described by Alzheimer also had a mutation in PSEN1 [41]. Moreover, APP is located on chromosome 21, and Down syndrome (21 trisomy) is linked to a high prevalence and early onset of AD; both Aβ and tau aggregation are facilitated in this setting [42] (Figure 4). The extent of Aβ deposition is correlated with that of tau aggregates among AD cases and an aged population [13] or in AD model mice with APP/MAPT-tg [43]. By contrast, mutations of the MAPT gene, encoding tau, are causative of frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism (FTDP), demonstrating marked tau aggregation but little or no Aβ deposition [44].

Figure 4.

AD pathology in a Down syndrome case. The patient had Down syndrome (21 trisomy) and died at the age of 48. Down syndrome cases demonstrate not only senile plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy ((A), temporal neocortex, Aβ11–28) but also severe tau aggregates ((B), entorhinal cortex, AT8). Scale bars = 100 μm.

However, the direct pathway from Aβ-deposition to tau-aggregation remains largely unknown and has proven difficult to reproduce experimentally. The iatrogenic transmission of Aβ pathology does not induce a tau pathology. It has been reported that patient-derived Aβ has a prion-like property of transmission, whose aggregative seed demonstrates transmission across individuals or species [45]. However, when Aβ is transmitted in vivo, Aβ deposition alone does not seem to cause AD-type tau pathology (3R and 4R mixed tauopathy and formation of NFTs). An example is the human transmission of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, often associated with parenchymal Aβ deposits, through grafts of dura mater, without or with minimal development of a tauopathy, even after decades [46]. Another example is the iatrogenic transmission of Aβ via the injection of cadaver-extracted human growth hormone (crGH). These batches of crGH were contaminated with prions, Aβ, and tau. Postmortem studies of the recipients revealed Aβ deposits, including senile plaques and CAA, in combination with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD). Tau aggregates were occasionally detected in these cases, mainly showing dots or neuritic patterns near the plaques and very occasional NFTs; the prevalence, morphology, severity, and distribution of tau pathology differed from and was far smaller than those in AD [47,48,49]. Intracerebral injection of patient-derived Aβ into APP-tg mice did not result in tau aggregation [50]. Another study reported that the induction of patient-derived Aβ dimers in primary hippocampal neurons produced neuritic dystrophy and facilitated the phosphorylation of tau within dystrophic neurites, but did not lead to the formation of NFTs [51]. Although injection of Aβ in wild-type mice does not induce the formation of NFT, the injection of Aβ in mutant-MAPT Tg mice (which develop NFTs) increases the formation of tau aggregates [52] and crossing APP mice with mutant MAPT-Tg mice also greatly increases the formation of tau aggregates [53,54]. The injection of human tau seeds also induces more neuritic tau pathology in the presence of amyloid plaque [55,56]. These facts highlight the accelerating role of Aβ in the induction of more NFT, when NFTs are already present.

Neuropathological studies have revealed that NFT can arise in the absence of or with sparse Aβ deposition among older people, termed primary aging-related tauopathy (PART). The morphology and topographic distribution of NFTs in PART do not differ from those in early AD [57]; a subset of PART may be symptomatic, termed senile dementia with NFT (SDNFT) [58]. As mentioned above, MAPT mutations cause FTDP; however, certain variants such as V337M and R406W yield AD-type tau filaments containing both 3R- and 4R-tau isoforms even in the absence of Aβ deposition [59,60]. Collectively, these findings indicate that tau aggregation can occur without Aβ deposits. Tau aggregates in AD might be regulated by multiple facilitating or preventive factors [61], even though Aβ deposition is a powerful driver of tau accumulation in AD.

Two questions, however, remain unresolved in this theory. First, it is highly controversial whether PART is really on a continuum of tau aggregation of AD or a distinct entity from AD. It has been described that conformation-dependent tau antibodies distinguish pathological tau in AD from other tauopathies but do not distinguish AD from PART [62], and tau seeding activity from the transentorhinal/entorhinal cortices (where tau pathology starts early) does not differ between AD and PART [63]. PART filaments are identical to those of AD and made of 3R and 4R tau isoforms [64]. However, the opposite findings are also reported; the seeding activity of neocortical tau in PART differs from that of early AD brains containing frequent neuritic plaques [65]. This result indicates that biochemical properties of insoluble tau in NFTs differ between AD and PART in the neocortex. Second, NFTs never progress beyond Braak stage IV in the absence of Aβ [16], arguing against a simple pathological continuum between PART and AD. At least, these findings suggest that Aβ deposition is necessary for the full progression of tau pathology characteristic of definite AD and that PART might play a role in the initiation of AD-related tau pathology, leading to its Aβ-induced progression. However, the precise molecular mechanisms linking Aβ to tau aggregation and the factors modulating this relationship remain incompletely understood.

3. Controversies of Tau Pathology in AD

3.1. Spatiotemporal Discrepancy Between Senile Plaque and NFTs in the Human Brain, from the Viewpoint of the ‘Amyloid Cascade’

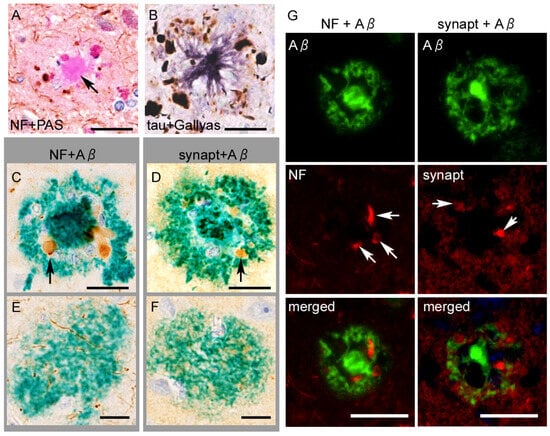

The spaces between the amyloid core and halo contain the crown, composed of swollen neurites, which are usually negative according to Aβ immunostaining. Neuropathological studies have revealed that the swollen neurites involved in neuritic plaques fundamentally express epitopes of axons and axon terminals rather than dendritic epitopes [66,67]. This finding, together with the sparse presentation of senile plaques in white matter, indicates that neuritic plaques prominently involve the distal portion of the axon (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Neuroaxonal or tau epitopes on senile plaques. (A) Anti-neurofilament (NF) immunohistochemistry combined with PAS-staining shows swollen axons surrounding the plaque core. The core itself (arrow) is immunonegative. (B) Anti-p-tau (AT8) immunohistochemistry combined with silver impregnation reveals neuritic tau aggregates surrounding an amyloid core. (C–F) Neuritic plaques contain epitopes of NF and synaptophysin (synapt) ((C,D), arrows) around the plaque core, whereas diffuse plaques do not (E,F). (G) Double immunofluorescence shows dystrophic axons (arrows in the left column) or swollen terminals (arrows in the right column) are engulfed by Aβ11–28, without a clear co-localization. Scale bars = (A–F) 10 μm and (G) 20 μm.

The swollen axons within the neuritic plaques abundantly contain hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates (Figure 5). Studies using multiple dissections of autopsied AD tissues cleared with the CLARITY protocol revealed that intra-axonal tau aggregates of the fornix were continuously extended to the mamillary body and made direct contact with senile plaques in the mammillary body [68,69]. Dystrophic neurites in senile plaques in the neocortex contain tau aggregates when NFTs are present in the same areas but not when NFTs are absent, indicating a close spatial relation between local neurons containing NFTs and plaque-associated tau aggregates [70], although the intra-axonal tau aggregates do not always connect to NFTs [71]. Interestingly, for PART, a recent study suggested an opposite sequence, in which tau aggregation in the entorhinal neurons (pre-α) starts from the dendrites and then spreads to the cytoplasm and axons [72]. Overall, neuritic tau aggregation in the senile plaque is strongly correlated with cytoplasmic NFTs, although it remains unclear whether the former always retrogradely develop the latter.

If we resort to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, it can be expected that NFTs should be enriched in neurons whose distal axons are involved in neuritic plaques. This speculation seems to be partially reasonable because Aβ-vulnerable regions often receive innervation from areas that develop early NFT pathology. For example, the upper molecular layer of the hippocampal dentate gyrus preferentially exhibits Aβ deposition and receives abundant glutamatergic innervation from the entorhinal cortex, one of the early regions affected by NFTs. Correlations between senile plaque burden in the dentate gyrus and NFT burden in the entorhinal cortex have been reported [73,74]. Similarly, early Aβ deposition in the cerebral neocortices corresponds to cholinergic innervation from the basal forebrain, which also develops NFTs during the early phase of AD [75].

However, mismatches between the Aβ and tau pathologies are also noted despite these anatomical correspondences. As discussed in the next chapter, tau aggregation in AD spreads laterally through adjacent cortical areas in a cortico-cortical manner with a smooth gradient, starting from the transentorhinal cortex. It is questionable whether such a highly hierarchical, lateral spreading of tau aggregation arises from distant effects by Aβ deposition, whose spread may start from any cerebral cortices varying among individuals. Moreover, certain regions show discordant pathology: the locus ceruleus is one of the earliest sites of NFT formation and abundantly projects to the cerebellum. Nevertheless, the cerebellum shows Aβ deposition at the latest stage of AD pathology. Similarly, the mamillary bodies and thalamus, which receive abundant innervation from the hippocampus, show relatively sparse Aβ accumulation. A recent study on a large sample size has addressed a mismatch between the Aβ and tau pathologies in subsets of AD cases that display severe Aβ deposition (including extensive neuritic plaques) but unexpectedly sparse NFTs [76].

Overall, Aβ seems to be a powerful facilitator of tau aggregates at a cellular level. However, spatial distribution and temporal spreading of tau aggregates demonstrate some discrepancies from what is expected from Aβ deposits in the context of cytoplasm–axon relationships.

3.2. Is AD a System Degeneration of Memory Circuits? From the Viewpoint of ‘Tauopathy’

From the viewpoint of tauopathy, AD can be defined as a form of selective ‘system degeneration’ primarily affecting the memory network [77,78]. This notion arises from the observation that tau aggregation begins in the transentorhinal cortex and extends to the hippocampus and associative neocortices [79], and this spreading course contains some critical nodes of the limbic memory system, including the parahippocampal–hippocampal loop and Papez circuit [80], in AD brains. The selective and highly hierarchical spreading of tau aggregates proposes a tau-autonomous mechanism for tau pathology in AD.

Neuropathological studies of various neurodegenerative disorders have revealed that atrophy, neuronal loss, and accumulation of neuron-aggregative proteins tend to develop along specific neuroanatomical systems that are distantly connected with long tracts beyond the white matter, a process termed ‘system degeneration’. Representative examples include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). In TAR DNA-binding protein 43kDa (TDP-43)-related ALS (ALS-TDP), upper and lower motor neurons that are distantly connected by the pyramidal tract are affected, showing neuronal loss and TDP-43 aggregation in both areas, resulting in a system degeneration of motor neurons [81,82]. In addition, TDP-43-related FTLD (FTLD-TDP) demonstrates system degeneration along corticostriatal circuits, which are critical for executive functions, mood regulation, and language generation [83,84]. A loss of projection neurons and their axon terminals, combined with TDP-43 aggregates, has been observed across the cerebral cortex, neostriatum, and globus pallidus or substantia nigra [85,86].

In addition to ALS/FTLD, various neurodegenerative disorders including PSP (dentato-rubral or pallido-nigral/luysian degeneration), CBD (cortico-striato-nigral degeneration), and multiple system atrophy (MSA) (olivo/ponto-cerebellar or striato-nigral degeneration) demonstrate system degeneration, showing selective, longitudinal, and poly-nodal impairment along these functional systems [87].

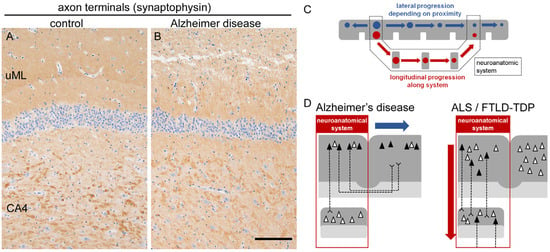

Importantly, the extension pattern of AD-related tau aggregation depends on spatial proximity, with lateral spreading toward adjacent areas resembling the ‘spreading of stain’. When the concept of a ‘system’ is considered, the propagation of tau aggregates in AD tends to terminate in a mono-nodal manner (Figure 6). For example, the Papez circuit, a classical memory system comprising the hippocampus, fornix, mammillary body, anterior nucleus of thalamus, cingulate gyrus, and parahippocampal gyrus, is known to be impaired in AD [80]. Indeed, this system contains AD-vulnerable nodes such as the hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus. However, the gradients of tau aggregates and neuronal loss do not necessarily follow the anatomical connection of the circuit; for example, the mammillary body, the next node after the hippocampus, is not preferentially involved in NFTs and neuronal loss [88].

Figure 6.

Synaptic loss and schematic of system degeneration. (A,B) In AD, axon terminals are depleted in the upper molecular layer (uML) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus, indicating loss of projection from the parahippocampal gyrus. Note the preservation of large synaptic boutons in CA4 projected from the dentate gyrus. Anti-synaptophysin immunohistochemistry. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) Schematic illustration of lateral (blue) and longitudinal (red) modes of system degeneration. Lateral degeneration depends on spatial proximity and occurs in a mono-nodal manner when the system is considered. Longitudinal degeneration is poly-nodal and continuous along the system. Gray matter is depicted in gray, and circles indicate neuronal loss and protein aggregation at each node. (D) Simplified illustration of lateral spreading of AD-related tau pathology and longitudinal spreading of ALS/FTLD-related changes. Gray matter is shown as dense gray, white matter as light gray, and red frames indicate the neuroanatomical system. The filled triangles indicate neurons containing protein aggregates, whereas blank ones are not affected.

A similar phenomenon is observed in the hippocampal loop [89]. The glutamatergic memory circuit originating from the entorhinal cortex mainly innervates the granule cells of the hippocampal dentate gyrus via the perforant path, followed by CA3 and CA4 via mossy fibers, and finally reaches CA1 via Schaffer collaterals. In this system, the entorhinal cortex is highly vulnerable to tau aggregation, whereas the dentate gyrus and CA3/CA4 are relatively spared; subsequently, CA1 and the subiculum are again vulnerable (Figure 6). Thus, although the memory circuits contain tau-vulnerable regions, neuronal loss and tau aggregation cannot be aligned along a single gradient within these systems. These findings support the view that tau aggregates in AD may spread along short-range neural connections, such as cortico-cortical projections, rather than long tract-dependent circuits [90].

A remarkable supporting finding comes from an autopsied AD patient who had undergone brain surgery 27 years earlier [91]. During surgery, a portion of the frontal cortex was dissected together with a tumor. At autopsy, an island-like cortical area was found to be isolated from the surrounding frontal cortex due to the surgical dissection, remaining connected only through long tracts in the deep white matter. Interestingly, the isolated cortex demonstrated diffuse plaques but not NFTs and neuritic plaques, although these were abundant in other cortical areas. This finding suggests that AD-related tau aggregation preferentially involves cortico-cortical tracts and their associated neurons rather than long-tract projections.

Experimental studies have clarified the propagative properties of tau aggregates derived from patients with AD, PSP, or CBD. Prion-like mechanisms of extracellular release and the propagation of tau aggregates along neuroanatomically connected areas might be central to this process [92,93,94]. Neuronal uptake of induced tau and seed-dependent aggregation have been reported using both in vitro and in vivo models expressing mutant [95,96] or wild-type [97,98] human tau. The hypothesis that tau seeds propagate via short cortico-cortical tracts in the AD brain, resulting in lateral spreading of tau aggregates, is therefore compelling.

However, questions remain regarding tau pathology in AD. As addressed at the beginning of this article, tau aggregates may mature from pretangles to NFTs and ultimately remain as ghost tangles, which lack recognizable cellular structures of the cytoplasm and nucleus. Importantly, it has been reported that tau isoforms change from a 4R-tau-rich state (pretangles and early NFTs) toward a 3R-tau-rich state (mature NFTs and ghost tangles) during the maturation of tau aggregates [24]. Upon a cross-sectional observation, the 3R-tau/4R-tau ratio correlates with the severity of tau aggregation, showing an increasing gradient from mildly affected to severely affected areas [24].

The tau-propagation theory may be compatible with the spread of 4R-tau in PSP and CBD but hardly explains the isoform shift observed in AD, because these isoforms are produced through alternative splicing of the MAPT gene. Moreover, events related to MAPT-splicing may not explain the isoform shift in tau aggregates in AD. Although several factors, including RNA-binding proteins [99], ribonucleoproteins [100], and splicing factors [101,102,103], have been reported to influence MAPT splicing, their roles remain mostly unknown in AD brains. It is known that mRNA levels of total or isoform-specific MAPT vary across studies and may not be in line with the isoform shift in tau in AD [104]. Indeed, a study reported that the 3R/4R mRNA ratio tended to be lower in advanced AD cases compared with normal controls or those with mild cognitive impairment [105]. While the intracellular growth of tau aggregates can be explained by seeding ability or post-translational events, the mechanisms underlying the 3R/4R isoform shift remain to be elucidated in AD.

4. Conclusions

According to the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’, Aβ deposition represents the upstream event that drives tau aggregation, leading to neuronal loss. However, neuropathological and experimental evidence indicates that the spaciotemporal relationship between tau and Aβ depositions is only partial and cannot fully explain the hierarchical pattern of tau propagation observed in AD.

Tau aggregation correlates more closely than Aβ deposition with neuronal loss, regional brain atrophy, and clinical severity. The stereotyped progression of tau pathology follows a proximity-dependent cortico-cortical pattern, beginning in the transentorhinal cortex and extending to the hippocampus and associative neocortex. This pattern does not strictly align with the connectivity of long-range memory circuits. In this respect, AD differs from the system-selective, poly-nodal degeneration observed in other 4R-tauopathies (PSP or CBD), ALS, and spinocerebellar degenerations. The exact determinants of the differential spreading manner of the tau aggregation (proximity-depending or systematic) between AD and 4R tauopathies remain largely elusive. In addition, our current understanding is limited for the dynamic isoform shift from 4R-tau-dominant to 3R-tau-dominant during NFT maturation in AD brains. Overall, tau pathology in AD is still enigmatic even more than 100 years after the first description of this disease. The pathogenesis of tau aggregation in AD cannot be explained simply by ‘amyloid cascade’ or ‘tau propagation along memory system’ alone, suggesting that there are missing pieces to fill the gaps between Aβ and tau pathologies or between AD and other tauopathies.

The emerging evidence indicates that while Aβ may facilitate tau aggregation, tau propagation in AD follows unique molecular and anatomical patterns that cannot be explained simply by the amyloid cascade. AD may thus represent a distinct tauopathy which is characterized by degeneration of local interactions among vulnerable neuronal populations, rather than global network degeneration, and the tauopathy powerfully leads disease progression of AD. Future research is necessary to identify the molecular triggers that initiate tau misfolding in early stages and to clarify how Aβ and tau pathologies interact to produce synaptic and neuronal loss.

The nature of tauopathy of AD might be related to the fact that treatment with anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) demonstrates significant but partial improvement for clinical progression of AD despite successful reduction in Aβ deposits [106]. When considering that tau aggregation is facilitated by Aβ, the suppression of Aβ deposition seems to be a reasonable strategy to slow down the spreading of tau pathology during the early disease stages. In fact, studies revealed an improvement in tau-markers, including plasma p-tau181 and p-tau217 and tau-PET, after anti-Aβ treatment [107,108,109,110]. However, as discussed in Chapter 3, the tau-autonomous pathway may also exist in the spreading of tau pathology in AD, meaning that anti-Aβ mAbs does not completely halt the progression of tau aggregation. In this context, dual therapy targeting Aβ and tau [111] may become a feasible approach, although the essential questions, ‘what initiates tau aggregation?’ and ‘how does Aβ deposition facilitate tau aggregation?’, remain to be elucidated.

As evidenced by these results, neuropathology had and still has a pivotal role in research on AD and other neurodegenerative diseases in order for us to understand these interactions [112].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing—original draft preparation, Y.R.; resources, Y.I.; supervision, K.A., T.U. and J.-P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by MHLW Research on rare and intractable diseases Program Grant Number JPMH23FC1008 (Y.I. and Y.R.), JSPS-KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP23K06935, JP25K22597, and JP25K10781 (Y.R.).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients, their families, and laboratory members for providing research sources and technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| Aβ | amyloid-β |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| ALS | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| CAA | cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

| CBD | corticobasal degeneration |

| FTDP | frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism |

| FTLD | frontotemporal lobar degeneration |

| MAPT | microtubule-associated protein tau |

| MSA | multiple system atrophy |

| NFT | neurofibrillary tangle |

| PART | primary aging-related tauopathy |

| PSP | progressive supranuclear palsy |

| PSEN1 | presenilin-1 |

| SDNFT | senile dementia with NFT |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43kDa |

| 3R/4R-tau | 3-repeat/4-repeat tau |

References

- GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–381, Correction in Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, e9. Correction in Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracner, T.; Chaturvedi, R.; Nguyen, P.; Heun-Johnson, H.; Tysinger, B.; Goldman, D.; Lakdawalla, D. The burden of cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer, A.; Stelzmann, R.A.; Schnitzlein, H.N.; Murtagh, F.R. An English translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 paper, “Uber eine eigenartige Erkankung der Hirnrinde”. Clin. Anat. 1995, 8, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, O. Miliare Nekrosen mit drusingen Wucherungen der Neurofibrillen, eine regelmässige Veränderung der Hirnrinde bei seniler Demenz. Monattsschrift Psychiatr. Neurol. 1907, 22, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, T.G. A History of Senile Plaques: From Alzheimer to Amyloid Imaging. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocq, F.; Marinesco, C. Sur les lésions et la pathogénie de l’épilepsie dite essentielle. Sem. Med. 1892, 12, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J.A.; Higgins, G.A. Alzheimer’s disease: The amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, R.; Head, D.; Allison, S.; Buckles, V.; Fagan, A.M.; Ladenson, J.H.; Morris, J.C.; Holtzman, D.M. Cerebrospinal Fluid Markers of Neurodegeneration and Rates of Brain Atrophy in Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therriault, J.; Janelidze, S.; Benedet, A.L.; Ashton, N.J.; Arranz Martínez, J.; Gonzalez-Escalante, A.; Bellaver, B.; Alcolea, D.; Vrillon, A.; Karim, H.; et al. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease using plasma biomarkers adjusted to clinical probability. Nat. Aging 2024, 4, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, W.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Huang, D.; Cheng, W.; Tian, J.; Luan, P. Advance and Prospect of Positron Emission Tomography in Alzheimer’s disease research. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 4899–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Alafuzoff, I.; Arzberger, T.; Kretzschmar, H.; Del Tredici, K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006, 112, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thal, D.R.; Rüb, U.; Orantes, M.; Braak, H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002, 58, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Tredici, K.; Braak, H. Neuropathology and neuroanatomy of TDP-43 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2022, 35, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, F.J.; Putka, A.F.; Raychaudhuri, U.; Hsu, S.; Bedlack, R.S.; Bennett, C.L.; La Spada, A.R. Revisiting Glutamate Excitotoxicity in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Age-Related Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montine, T.J.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Mirra, S.S.; et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16, 271–278; discussion 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirra, S.S.; Heyman, A.; McKeel, D.; Sumi, S.M.; Crain, B.J.; Brownlee, L.M.; Vogel, F.S.; Hughes, J.P.; van Belle, G.; Berg, L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of A45Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1991, 41, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brion, J.P. Immunological demonstration of tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2006, 9, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soeda, Y.; Hayashi, E.; Nakatani, N.; Ishigaki, S.; Takaichi, Y.; Tachibana, T.; Riku, Y.; Chambers, J.K.; Koike, R.; Mohammad, M.; et al. A novel monoclonal antibody generated by immunization with granular tau oligomers binds to tau aggregates at 423-430 amino acid sequence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, S.; Uchihara, T.; Aiba, I.; Iwasaki, Y.; Mimuro, M.; Takahashi, R.; Yoshida, M. Ultrastructural differences in pretangles between Alzheimer disease and corticobasal degeneration revealed by comparative light and electron microscopy. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mandelkow, E. Tau in physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, R.; Lashley, T.; Gibb, G.; Hanger, D.; Hope, A.; Reid, A.; Bandopadhyay, R.; Utton, M.; Strand, C.; Jowett, T.; et al. Pathological inclusion bodies in tauopathies contain distinct complements of tau with three or four microtubule-binding repeat domains as demonstrated by new specific monoclonal antibodies. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2003, 29, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Hirokawa, K.; Kamei, S.; Uchihara, T. Isoform transition from four-repeat to three-repeat tau underlies dendrosomatic and regional progression of neurofibrillary pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buée, L.; Bussière, T.; Buée-Scherrer, V.; Delacourte, A.; Hof, P.R. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2000, 33, 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Maat-Schieman, M.L.; van Duinen, S.G.; Prins, F.A.; Neeskens, P.; Natté, R.; Roos, R.A. Amyloid beta protein (Abeta) starts to deposit as plasma membrane-bound form in diffuse plaques of brains from hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis-Dutch type, Alzheimer disease and nondemented aged subjects. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000, 59, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.V.; Crook, R.; Hardy, J.; Dickson, D.W. Cotton wool plaques in non-familial late-onset Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 60, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, B.D.C.; Bulk, M.; Jonker, A.J.; Morrema, T.H.J.; van den Berg, E.; Popovic, M.; Walter, J.; Kumar, S.; van der Lee, S.J.; Holstege, H.; et al. The coarse-grained plaque: A divergent Aβ plaque-type in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 140, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, T.C.; Vickers, J.C. The morphological phenotype of beta-amyloid plaques and associated neuritic changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 2001, 105, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, P.T.; Alafuzoff, I.; Bigio, E.H.; Bouras, C.; Braak, H.; Cairns, N.J.; Castellani, R.J.; Crain, B.J.; Davies, P.; Del Tredici, K.; et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: A review of the literature. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 71, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brendza, R.P.; Bacskai, B.J.; Cirrito, J.R.; Simmons, K.A.; Skoch, J.M.; Klunk, W.E.; Mathis, C.A.; Bales, K.R.; Paul, S.M.; Hyman, B.T.; et al. Anti-Abeta antibody treatment promotes the rapid recovery of amyloid-associated neuritic dystrophy in PDAPP transgenic mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Luehmann, M.; Coomaraswamy, J.; Bolmont, T.; Kaeser, S.; Schaefer, C.; Kilger, E.; Neuenschwander, A.; Abramowski, D.; Frey, P.; Jaton, A.L.; et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science 2006, 313, 1781–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsering, W.; Prokop, S. Neuritic Plaques—Gateways to Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 61, 2808–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deczkowska, A.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Weiner, A.; Colonna, M.; Schwartz, M.; Amit, I. Disease-Associated Microglia: A Universal Immune Sensor of Neurodegeneration. Cell 2018, 173, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baligács, N.; Albertini, G.; Borrie, S.C.; Serneels, L.; Pridans, C.; Balusu, S.; De Strooper, B. Homeostatic microglia initially seed and activated microglia later reshape amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brier, M.R.; Gordon, B.; Friedrichsen, K.; McCarthy, J.; Stern, A.; Christensen, J.; Owen, C.; Aldea, P.; Su, Y.; Hassenstab, J.; et al. Tau and Aβ imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 338ra66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.E.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Ross, O.A.; Petersen, R.C.; Duara, R.; Dickson, D.W. Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease with distinct clinical characteristics: A retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossenkoppele, R.; Salvadó, G.; Janelidze, S.; Pichet Binette, A.; Bali, D.; Karlsson, L.; Palmqvist, S.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Stomrud, E.; Therriault, J.; et al. Plasma p-tau217 and tau-PET predict future cognitive decline among cognitively unimpaired individuals: Implications for clinical trials. Nat. Aging 2025, 5, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, E.D.; Scearce-Levie, K.; Palop, J.J.; Yan, F.; Cheng, I.H.; Wu, T.; Gerstein, H.; Yu, G.Q.; Mucke, L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science 2007, 316, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, K.; Ando, K.; Laporte, V.; Dedecker, R.; Suain, V.; Authelet, M.; Héraud, C.; Pierrot, N.; Yilmaz, Z.; Octave, J.N.; et al. Lack of tau proteins rescues neuronal cell death and decreases amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1 mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, U.; Winter, P.; Graeber, M.B. A presenilin 1 mutation in the first case of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanger, D.P.; Brion, J.P.; Gallo, J.M.; Cairns, N.J.; Luthert, P.J.; Anderton, B.H. Tau in Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome is insoluble and abnormally phosphorylated. Biochem. J. 1991, 275, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurtado, D.E.; Molina-Porcel, L.; Iba, M.; Aboagye, A.K.; Paul, S.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M. A-beta accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Swieten, J.; Spillantini, M.G. Hereditary frontotemporal dementia caused by Tau gene mutations. Brain Pathol. 2007, 17, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaunmuktane, Z.; Mead, S.; Ellis, M.; Wadsworth, J.D.; Nicoll, A.J.; Kenny, J.; Launchbury, F.; Linehan, J.; Richard-Loendt, A.; Walker, A.S.; et al. Evidence for human transmission of amyloid-β pathology and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nature 2015, 525, 247–250, Erratum in Nature 2015, 526, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, D.; Porché, M.; Cabrejo, L.; Guidoux, C.; Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Nicolas, G.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Plu, I.; Chabriat, H.; Duyckaerts, C. Fatal Aβ cerebral amyloid angiopathy 4 decades after a dural graft at the age of 2 years. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 801–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, D.L.; Adlard, P.; Peden, A.H.; Lowrie, S.; Le Grice, M.; Burns, K.; Jackson, R.J.; Yull, H.; Keogh, M.J.; Wei, W.; et al. Amyloid-β accumulation in the CNS in human growth hormone recipients in the UK. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 221–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Sazdovitch, V.; Ando, K.; Seilhean, D.; Privat, N.; Yilmaz, Z.; Peckeu, L.; Amar, E.; Comoy, E.; Maceski, A.; et al. Neuropathology of iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and immunoassay of French cadaver-sourced growth hormone batches suggest possible transmission of tauopathy and long incubation periods for the transmission of Abeta pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, G.; Farmer, S.F.; Hyare, H.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; Mead, S.; Ryan, N.S.; Schott, J.M.; Werring, D.J.; Rudge, P.; Collinge, J. Iatrogenic Alzheimer’s disease in recipients of cadaveric pituitary-derived growth hormone. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, M.D.; Lipinski, W.J.; Callahan, M.J.; Bian, F.; Durham, R.A.; Schwarz, R.D.; Roher, A.E.; Walker, L.C. Evidence for seeding of beta -amyloid by intracerebral infusion of Alzheimer brain extracts in beta -amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 3606–3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Shepardson, N.; Yang, T.; Chen, G.; Walsh, D.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5819–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götz, J.; Chen, F.; van Dorpe, J.; Nitsch, R.M. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science 2001, 293, 1491–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.; Dickson, D.W.; Lin, W.L.; Chisholm, L.; Corral, A.; Jones, G.; Yen, S.H.; Sahara, N.; Skipper, L.; Yager, D.; et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science 2001, 293, 1487–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Héraud, C.; Goufak, D.; Ando, K.; Leroy, K.; Suain, V.; Yilmaz, Z.; De Decker, R.; Authelet, M.; Laporte, V.; Octave, J.N.; et al. Increased misfolding and truncation of tau in APP/PS1/tau transgenic mice compared to mutant tau mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 62, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Guo, J.L.; McBride, J.D.; Narasimhan, S.; Kim, H.; Changolkar, L.; Zhang, B.; Gathagan, R.J.; Yue, C.; Dengler, C.; et al. Amyloid-β plaques enhance Alzheimer’s brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C.; Houben, S.; Suain, V.; Yilmaz, Z.; De Decker, R.; Vanden Dries, V.; Boom, A.; Mansour, S.; Leroy, K.; Ando, K.; et al. Amyloid-β pathology enhances pathological fibrillary tau seeding induced by Alzheimer PHF in vivo. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Braak, H.; Brion, J.P.; Buée, L.; Del Tredici, K.; Goedert, M.; Halliday, G.; Neumann, M.; Spillantini, M.G.; Tolnay, M.; et al. PART is part of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M. Senile dementia of the neurofibrillary tangle type (tangle-only dementia): Neuropathological criteria and clinical guidelines for diagnosis. Neuropathology 2003, 23, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, S.; Schonhaut, D.R.; Boeve, B.F.; Seeley, W.W.; Ossenkoppele, R.; O’Neil, J.P.; Lazaris, A.; Rosen, H.J.; Boxer, A.L.; Perry, D.C.; et al. Frontotemporal dementia with the V337M MAPT mutation: Tau-PET and pathology correlations. Neurology 2017, 88, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Lövestam, S.; Murzin, A.G.; Peak-Chew, S.; Franco, C.; Bogdani, M.; Latimer, C.; Murrell, J.R.; Cullinane, P.W.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; et al. Tau filaments with the Alzheimer fold in human MAPT mutants V337M and R406W. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2025, 32, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda-Falla, D.; Sanchez, J.S.; Almeida, M.C.; Boassa, D.; Acosta-Uribe, J.; Vila-Castelar, C.; Ramirez-Gomez, L.; Baena, A.; Aguillon, D.; Villalba-Moreno, N.D.; et al. Distinct tau neuropathology and cellular profiles of an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote protected against autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2022, 144, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, G.S.; Banks, R.A.; Kim, B.; Changolkar, L.; Riddle, D.M.; Leight, S.N.; Irwin, D.J.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.Y. Detection of Alzheimer Disease (AD)-Specific Tau Pathology in AD and NonAD Tauopathies by Immunohistochemistry with Novel Conformation-Selective Tau Antibodies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 77, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, S.K.; Del Tredici, K.; Thomas, T.L.; Braak, H.; Diamond, M.I. Tau seeding activity begins in the transentorhinal/entorhinal regions and anticipates phospho-tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and PART. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Murzin, A.G.; Falcon, B.; Epstein, A.; Machin, J.; Tempest, P.; Newell, K.L.; Vidal, R.; Garringer, H.J.; Sahara, N.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease with PET ligand APN-1607. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, D.F.; Smirnov, D.S.; Coughlin, D.; Peng, I.; Standke, H.G.; Kim, Y.; Pizzo, D.P.; Unapanta, A.; Andreasson, T.; Hiniker, A.; et al. Early Alzheimer’s Disease with frequent neuritic plaques harbors neocortical tau seeds distinct from primary age-related tauopathy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masliah, E.; Mallory, M.; Deerinck, T.; DeTeresa, R.; Lamont, S.; Miller, A.; Terry, R.D.; Carragher, B.; Ellisman, M. Re-evaluation of the structural organization of neuritic plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1993, 52, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Comparative epitope analysis of neuronal cytoskeletal proteins in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaque neurites and neuropil threads. Lab. Investig. 1991, 64, 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Thierry, M.; Boluda, S.; Delatour, B.; Marty, S.; Seilhean, D.; Brainbank Neuro-CEB Neuropathology Network; Potier, M.C.; Duyckaerts, C. Human subiculo-fornico-mamillary system in Alzheimer’s disease: Tau seeding by the pillar of the fornix. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 139, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, K.; Laborde, Q.; Lazar, A.; Godefroy, D.; Youssef, I.; Amar, M.; Pooler, A.; Potier, M.C.; Delatour, B.; Duyckaerts, C. Inside Alzheimer brain with CLARITY: Senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and axons in 3-D. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 128, 457–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, A.; Anderton, B.H.; Brion, J.P.; Ulrich, J. Senile plaque neurites fail to demonstrate anti-paired helical filament and anti-microtubule-associated protein-tau immunoreactive proteins in the absence of neurofibrillary tangles in the neocortex. Acta Neuropathol. 1989, 77, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.L.; Murray, J.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Continuity of neuropil threads with tangle-bearing and tangle-free neurons in Alzheimer disease cortex. A confocal laser scanning microscopy study. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1993, 18, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Mayer, B.; Feldengut, S.; Schön, M.; Del Tredici, K. Sequence and trajectory of early Alzheimer’s disease-related tau inclusions in the hippocampal formation of cases without amyloid-β deposits. Acta Neuropathol. 2025, 149, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senut, M.C.; Roudier, M.; Davous, P.; Fallet-Bianco, C.; Lamour, Y. Senile dementia of the Alzheimer type: Is there a correlation between entorhinal cortex and dentate gyrus lesions? Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 82, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazer-Hanke, D.M.; Hanke, J. Progression of Alzheimer-related neuritic plaque pathology in the entorhinal region, perirhinal cortex and hippocampal formation. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 1999, 10, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.K.; Chang, R.C.; Pearce, R.K.; Gentleman, S.M. Nucleus basalis of Meynert revisited: Anatomy, history and differential involvement in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.G.; Katsumata, Y.; Wu, X.; Aung, K.Z.; Fardo, D.W.; Forrest, S.L.; Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium; Nelson, P.T. Amyloid-β predominant Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic change. Brain 2025, 148, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Christen, Y. Connections, Cognition and Alzheimer diseaseons, Cognition and Alzheimer disease. In Research and Perspective in Alzheimer’s Disease; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Delatour, B.; Potier, M.C. Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118, 5–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, B.T.; Van Hoesen, G.W.; Damasio, A.R.; Barnes, C.L. Alzheimer’s disease: Cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science 1984, 225, 1168–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, M.; Wong, S.; Tan, R.; Irish, M.; Piguet, O.; Kril, J.; Hodges, J.R.; Halliday, G. In vivo and post-mortem memory circuit integrity in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2012, 135, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ince, P.G.; Lowe, J.; Shaw, P.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Current issues in classification, pathogenesis and molecular pathology. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1998, 24, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riku, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Yoshida, M.; Tatsumi, S.; Mimuro, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Katsuno, M.; Iguchi, Y.; Masuda, M.; Senda, J.; et al. Lower motor neuron involvement in TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa-related frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeley, W.W. The Salience Network: A Neural System for Perceiving and Responding to Homeostatic Demands. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 9878–9882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Nakatani, H.; Ueno, K.; Asamizuya, T.; Cheng, K.; Tanaka, K. The neural basis of intuitive best next-move generation in board game experts. Science 2011, 331, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riku, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Yoshida, M.; Mimuro, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Masuda, M.; Ishigaki, S.; Katsuno, M.; Sobue, G. Marked Involvement of the Striatal Efferent System in TAR DNA-Binding Protein 43 kDa-Related Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 75, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riku, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Yoshida, M.; Mimuro, M.; Iwasaki, Y.; Masuda, M.; Ishigaki, S.; Katsuno, M.; Sobue, G. Pathologic Involvement of Glutamatergic Striatal Inputs from the Cortices in TAR DNA-Binding Protein 43 kDa-Related Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 76, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, K.; Koyano, S.; Yagishita, S. Simple and clear differentiation of spinocerebellar degenerations: Overview of macroscopic and low-power view findings. Neuropathology 2022, 42, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowey, E.D.; Ziskin, J.L. Hippocampal phospho-tau/MAPT neuropathology in the fornix in Alzheimer disease: An immunohistochemical autopsy study. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Uchihara, T.; Arai, N.; Mizutani, T.; Iwata, M. Progression of hippocampal degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with or without memory impairment: Distinction from Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 117, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, P.R.; Morrison, J.H. The cellular basis of cortical disconnection in Alzheimer disease and related dementing conditions. In Alzheimer Disease, 2nd ed.; Terry, R.D., Katzman, R., Bick, K.L., Sisodia, S.S., Eds.; Lipincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; pp. 210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Duyckaerts, C.; Uchihara, T.; Seilhean, D.; He, Y.; Hauw, J.J. Dissociation of Alzheimer type pathology in a disconnected piece of cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 1997, 93, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudher, A.; Colin, M.; Dujardin, S.; Medina, M.; Dewachter, I.; Alavi Naini, S.M.; Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E.; Buée, L.; Goedert, M.; et al. What is the evidence that tau pathology spreads through prion-like propagation? Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017, 5, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, E.; Bilousova, T.; Melnik, M.; Fakhrutdinov, D.; Poon, W.W.; Vinters, H.V.; Miller, C.A.; Corrada, M.; Kawas, C.; Bohannan, R.; et al. Exosomal tau with seeding activity is released from Alzheimer’s disease synapses, and seeding potential is associated with amyloid beta. Lab. Investig. 2021, 101, 1605–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Wegmann, S.; Cho, H.; DeVos, S.L.; Commins, C.; Roe, A.D.; Nicholls, S.B.; Carlson, G.A.; Pitstick, R.; Nobuhara, C.K.; et al. Neuronal uptake and propagation of a rare phosphorylated high-molecular-weight tau derived from Alzheimer’s disease brain. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluda, S.; Iba, M.; Zhang, B.; Raible, K.M.; Lee, V.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Differential induction and spread of tau pathology in young PS19 tau transgenic mice following intracerebral injections of pathological tau from Alzheimer’s disease or corticobasal degeneration brains. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 129, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavaguera, F.; Bolmont, T.; Crowther, R.A.; Abramowski, D.; Frank, S.; Probst, A.; Fraser, G.; Stalder, A.K.; Beibel, M.; Staufenbiel, M.; et al. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audouard, E.; Houben, S.; Masaracchia, C.; Yilmaz, Z.; Suain, V.; Authelet, M.; De Decker, R.; Buée, L.; Boom, A.; Leroy, K.; et al. High-Molecular-Weight Paired Helical Filaments from Alzheimer Brain Induces Seeding of Wild-Type Mouse Tau into an Argyrophilic 4R Tau Pathology in Vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 2709–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeachan, R.I.; Keavey, L.; Simzer, E.M.; Chang, Y.Y.; Rose, J.L.; Spires-Jones, M.P.; Gilmore, M.; Holt, K.; Meftah, S.; Ravingerova, N.; et al. Evidence for trans-synaptic propagation of oligomeric tau in human progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 1622–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Havlioglu, N.; Tarn, W.Y.; Wu, J.Y. RBM4 interacts with an intronic element and stimulates tau exon 10 inclusion. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 24479–24488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Tse, S.W.; Andreadis, A. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein E3 modestly activates splicing of tau exon 10 via its proximal downstream intron, a hotspot for frontotemporal dementia mutations. Gene 2010, 451, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storbeck, M.; Hupperich, K.; Gaspar, J.A.; Meganathan, K.; Martínez Carrera, L.; Wirth, R.; Sachinidis, A.; Wirth, B. Neuronal-specific deficiency of the splicing factor Tra2b causes apoptosis in neurogenic areas of the developing mouse brain. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riku, Y.; Iwasaki, Y.; Ishigaki, S.; Akagi, A.; Hasegawa, M.; Nishioka, K.; Li, Y.; Riku, M.; Ikeuchi, T.; Fujioka, Y.; et al. Motor neuron TDP-43 proteinopathy in progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. Brain 2022, 145, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishigaki, S.; Fujioka, Y.; Okada, Y.; Riku, Y.; Udagawa, T.; Honda, D.; Yokoi, S.; Endo, K.; Ikenaka, K.; Takagi, S.; et al. Altered Tau Isoform Ratio Caused by Loss of FUS and SFPQ Function Leads to FTLD-like Phenotypes. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Augustinack, J.C.; Ingelsson, M. Transcriptional and conformational changes of the tau molecule in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1739, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, S.D.; Che, S.; Counts, S.E.; Mufson, E.J. Shift in the ratio of three-repeat tau and four-repeat tau mRNAs in individual cholinergic basal forebrain neurons in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2006, 96, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Wang, R.Z.; Wang, Z.; Hu, H.; Xu, W.; Zhu, L.; Sun, Y.; Chen, K.L.; Chen, S.F.; He, X.Y.; et al. Safety and short-term outcomes of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease in China: A multicentre study. Brain 2025, epub ahead print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDade, E.; Cummings, J.L.; Dhadda, S.; Swanson, C.J.; Reyderman, L.; Kanekiyo, M.; Koyama, A.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L.D.; Bateman, R.J. Lecanemab in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease: Detailed results on biomarker, cognitive, and clinical effects from the randomized and open-label extension of the phase 2 proof-of-concept study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ou, R.; Wei, Q.; Li, C.; Song, W.; Zhao, B.; Yang, J.; Fu, J.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Lecanemab treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease of varying severities and associated plasma biomarkers monitoring: A multi-center real-world study in China. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhao, H.; Sun, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Zou, L. Combined 64-channel EEG and PET evaluation of lecanemab efficacy: Two case reports. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2025, 9, 25424823251395615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angioni, D.; Middleton, L.; Bateman, R.; Aisen, P.; Boxer, A.; Sha, S.; Zhou, J.; Gerlach, I.; Raman, R.; Fillit, H.; et al. Challenges and opportunities for novel combination therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: A report from the EU/US CTAD Task Force. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, D.L.; Grinberg, L.T.; Ahrendsen, J.T.; Beach, T.G.; Bieniek, K.F.; Castellani, R.J.; Chkheidze, R.; Cobos, I.; Cohen, M.; Crary, J.F.; et al. Celebrating neuropathology’s contributions to Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).