1. Introduction

Cellular repair mechanisms are fundamental biological processes that restore tissue integrity following injury through coordinated migration, proliferation, and matrix remodeling. In epithelial tissues, keratinocytes play a central role in re-establishing barrier function by migrating from wound edges to cover denuded areas—a process termed re-epithelialization [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This cellular response involves complex signaling cascades regulated by growth factors, cytokines, and interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

1,

7,

8,

9]. Fibroblasts contribute to repair by synthesizing and remodeling ECM constituents, including collagens and proteoglycans, concurrently influencing keratinocyte growth and maturation via release of bioactive molecules including interleukin-1 (IL-1), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [

10,

11]. The equilibrium among these reparative mechanisms dictates the trajectory of healing, either toward normal tissue architecture or fibrotic pathology. Understanding the molecular pathways regulating keratinocyte migration and proliferation is thus critical for designing interventions that promote tissue repair in aesthetic and reconstructive medicine.

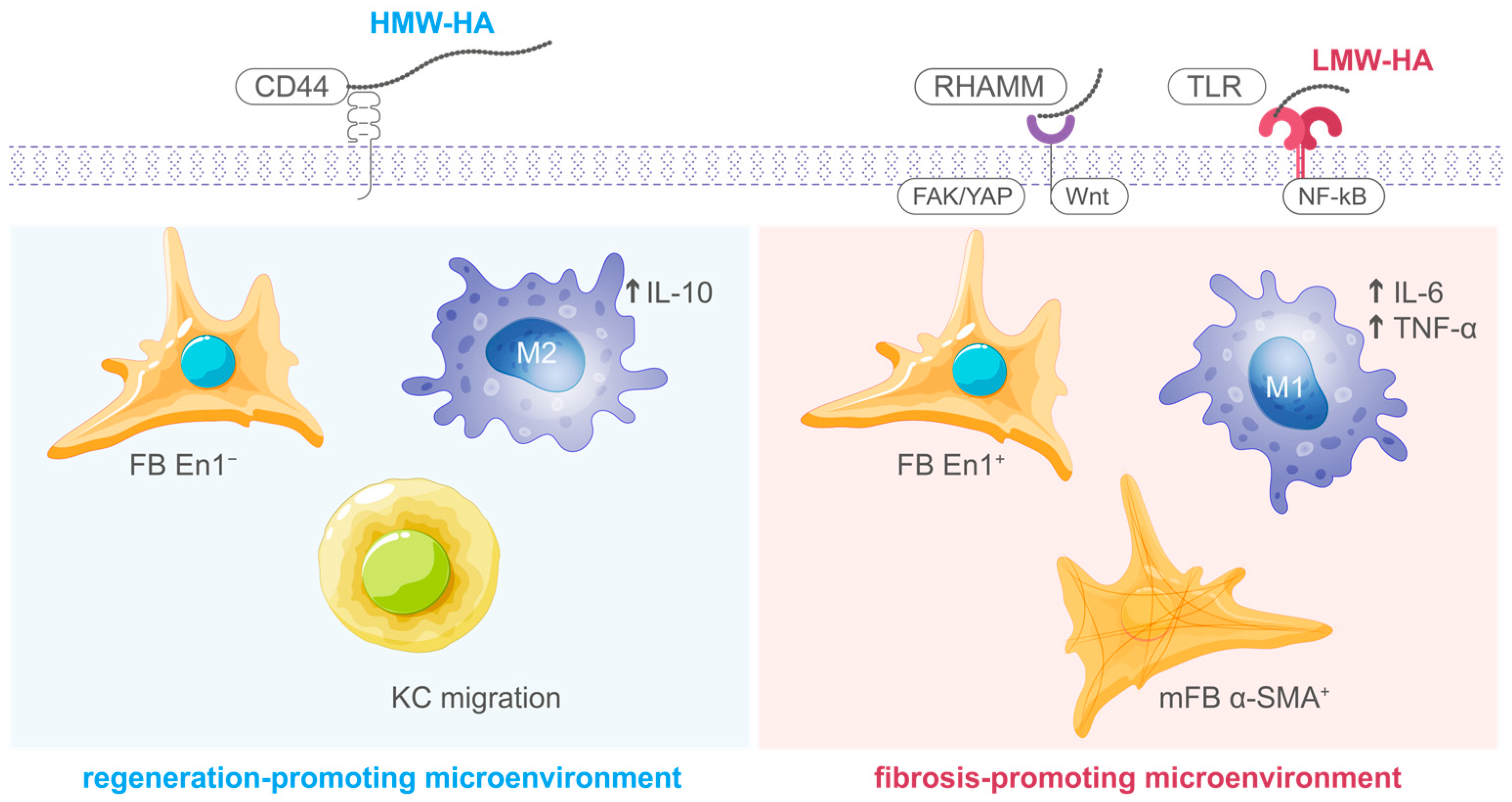

Hyaluronic acid (HA) represents a non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan consisting of repetitive disaccharide moieties containing D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine [

12]. This ubiquitous extracellular matrix constituent exerts essential regulatory functions during cellular repair. HA exhibits molecular weight-dependent bioactivity, whereby high-molecular-weight (HMW-HA; >1000 kDa) and low-molecular-weight (LMW-HA; <500 kDa) variants demonstrate divergent functional characteristics [

13]. HMW-HA, which predominates in physiologically normal tissues, exerts anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective actions by preserving ECM water content, supporting cell–matrix interactions through CD44 receptor binding, and inhibiting excessive inflammatory responses [

9,

14]. In contrast, LMW-HA fragments generated during tissue injury or enzymatic degradation function as endogenous danger signals that activate innate immune receptors, particularly Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR2/4), thereby initiating pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic responses essential for the early phases of tissue repair [

13,

15]. This molecular weight-dependent duality allows HA to function as a dynamic regulator that modulates the transition from injury-induced inflammation to matrix remodeling and tissue stabilization (

Figure 1) [

9,

12].

Trehalose, a non-reducing disaccharide formed by two glucose units linked by an α,α-1,1-glycosidic bond, is recognized as a potent bioprotective agent exhibiting diverse functions in cellular stress response and tissue repair [

19]. Beyond its well-established function as a chemical chaperone that stabilizes proteins and membranes under oxidative stress conditions, trehalose actively modulates cellular repair mechanisms through several distinct pathways [

20,

21,

22]. Trehalose promotes autophagy—a critical cellular quality control process that removes damaged organelles and protein aggregates—thereby supporting the metabolic adaptation required for sustained repair activity [

23,

24]. Furthermore, trehalose exerts protective effects against advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which accumulate during oxidative stress and aging, disrupting normal ECM architecture and impairing cellular migration [

19]. Recent evidence indicates that trehalose is capable of inducing fibroblasts to establish a prohealing senescence-like phenotype defined by cell cycle arrest and enhanced growth factor secretion, thereby promoting tissue regeneration by creating a favorable paracrine environment for keratinocyte proliferation and migration [

25]. When combined with hyaluronic acid, trehalose demonstrates synergistic effects that enhance both the stability of HA within the ECM and its bioactivity, creating an optimal microenvironment for keratinocyte migration and proliferation while simultaneously mitigating oxidative damage and glycation-induced tissue dysfunction [

19,

26,

27].

Although the distinct biological functions of HMW-HA and LMW-HA in tissue repair are established, the relative impacts of formulations combining different molecular weight ranges of HA with trehalose on keratinocyte repair mechanisms are not yet fully defined. Therefore, the present study aimed to provide preliminary characterization comparing the effects of two distinct hyaluronic acid-based formulations—one containing low- and medium-high-molecular-weight range HA combined with trehalose, and another containing high-molecular-weight HA—on cellular repair processes in human keratinocytes using an in vitro scratch wound model. While these formulations differ in both molecular weight composition and the presence of trehalose, the findings may provide insights into their distinct mechanisms of action and potential applications in aesthetic and regenerative medicine.

2. Results

2.1. Low- and Medium-High-Molecular-Weight Range HA Formulation (Resteem X)

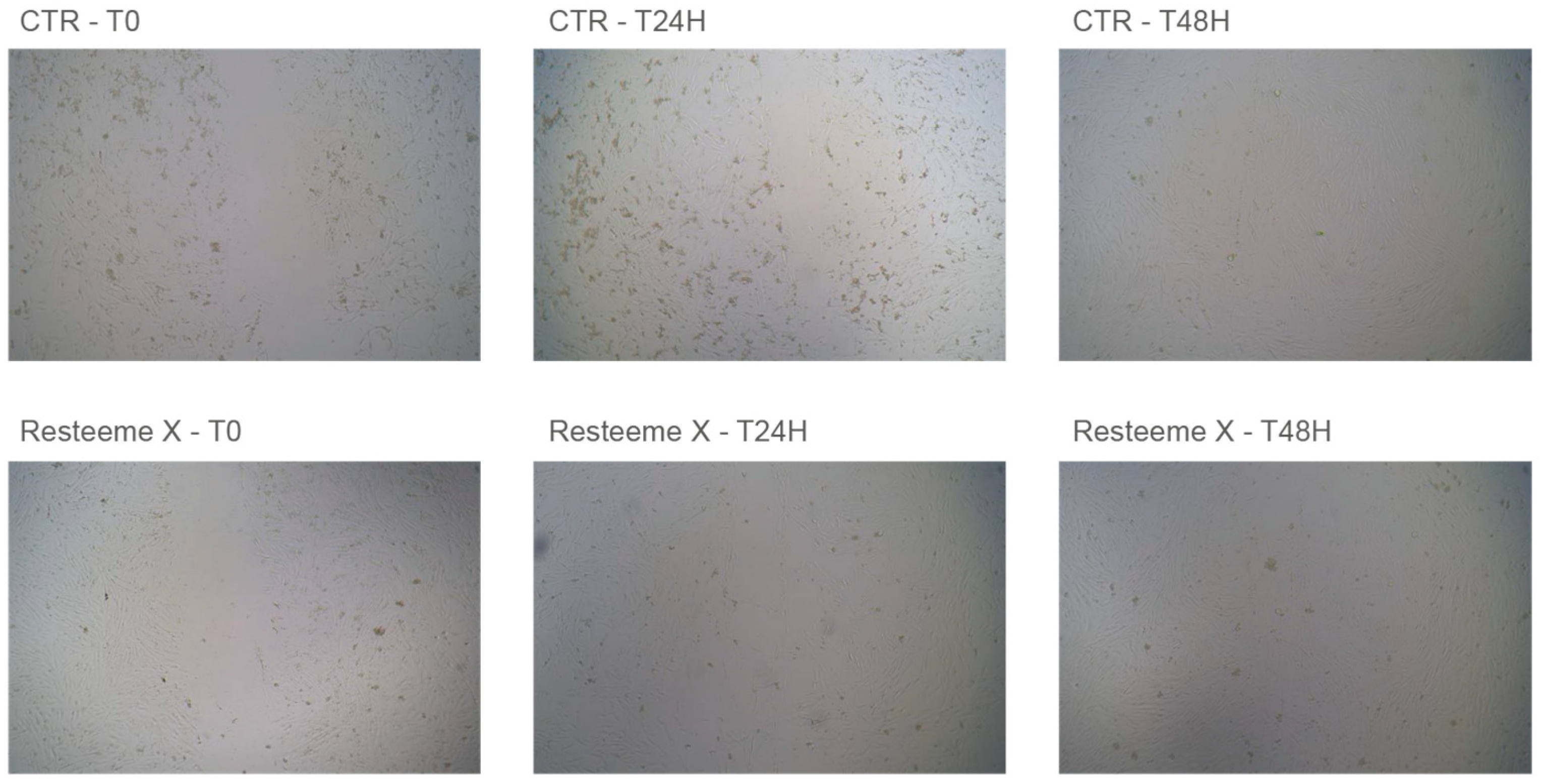

Application of the low- and medium-high-molecular-weight range hyaluronic acid formulation containing trehalose (Resteem X; hereafter referred to as the LMHMW-HA formulation with trehalose) promoted visible keratinocyte migration and proliferation in the cellular repair model. All measurements represent mean values ± standard deviation (SD) derived from three separate experiments (

n = 3). Representative micrographs (

Figure 2) illustrate control (CTR−) and treated cultures at baseline (T0), 24 h, and 48 h. Progressive closure of the acellular gap was observed from lesion borders toward the center, and at 48 h the treated monolayers exhibited complete closure with a visibly higher cell density compared with controls.

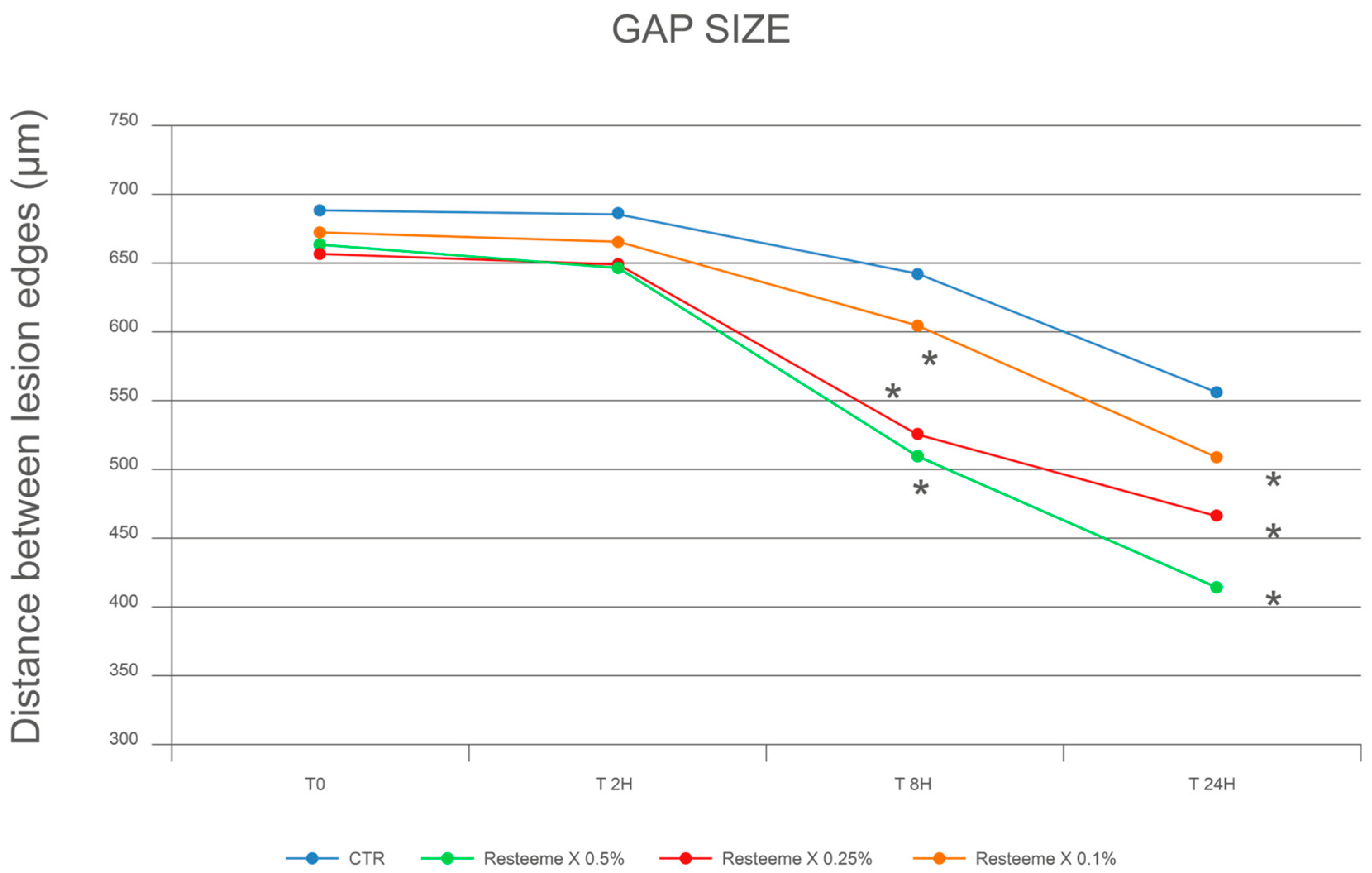

At baseline (T0), the inter-edge distance averaged 691.4 ± 66.7 µm in controls.

After 2 h, distances were 685.9 ± 56.2 µm (−0.8%) in controls and 646.8 ± 81.5 µm (−2.5%), 649.4 ± 84.5 µm (−1.5%), and 665.6 ± 56.1 µm (−1.0%) for 0.5%, 0.25%, and 0.1% Resteem X, respectively.

After 8 h, controls measured 643.4 ± 31.4 µm (−6.9%), while the corresponding values for treated cultures were 512.9 ± 80.2 µm (−22.7%), 527.3 ± 33.9 µm (−20.0%), and 605.0 ± 31.3 µm (−10.0%) for 0.5%, 0.25%, and 0.1%.

After 24 h, controls were 556.3 ± 37.2 µm (−19.5%), compared with 416.4 ± 69.3 µm (−37.2%), 467.4 ± 83.2 µm (−29.1%), and 510.7 ± 47.2 µm (−24.1%) for the three concentrations (

Figure 3;

Table 1 and

Table 2).

No cytotoxic alterations (e.g., vacuolization or detachment) were observed at any concentration. Complete gap closure was observed at approximately 48 h for all tested concentrations of Resteem X. Visual inspection confirmed full gap closure at this time point, although photographic documentation was limited to baseline, 2 h, 8 h, 24 h, and 48 h intervals. At the highest concentration, a slight tightening of the monolayer edges was visible, consistent with a more condensed alignment and enhanced cellular density.

2.2. High-Molecular-Weight Range HA Formulation (Resteem L)

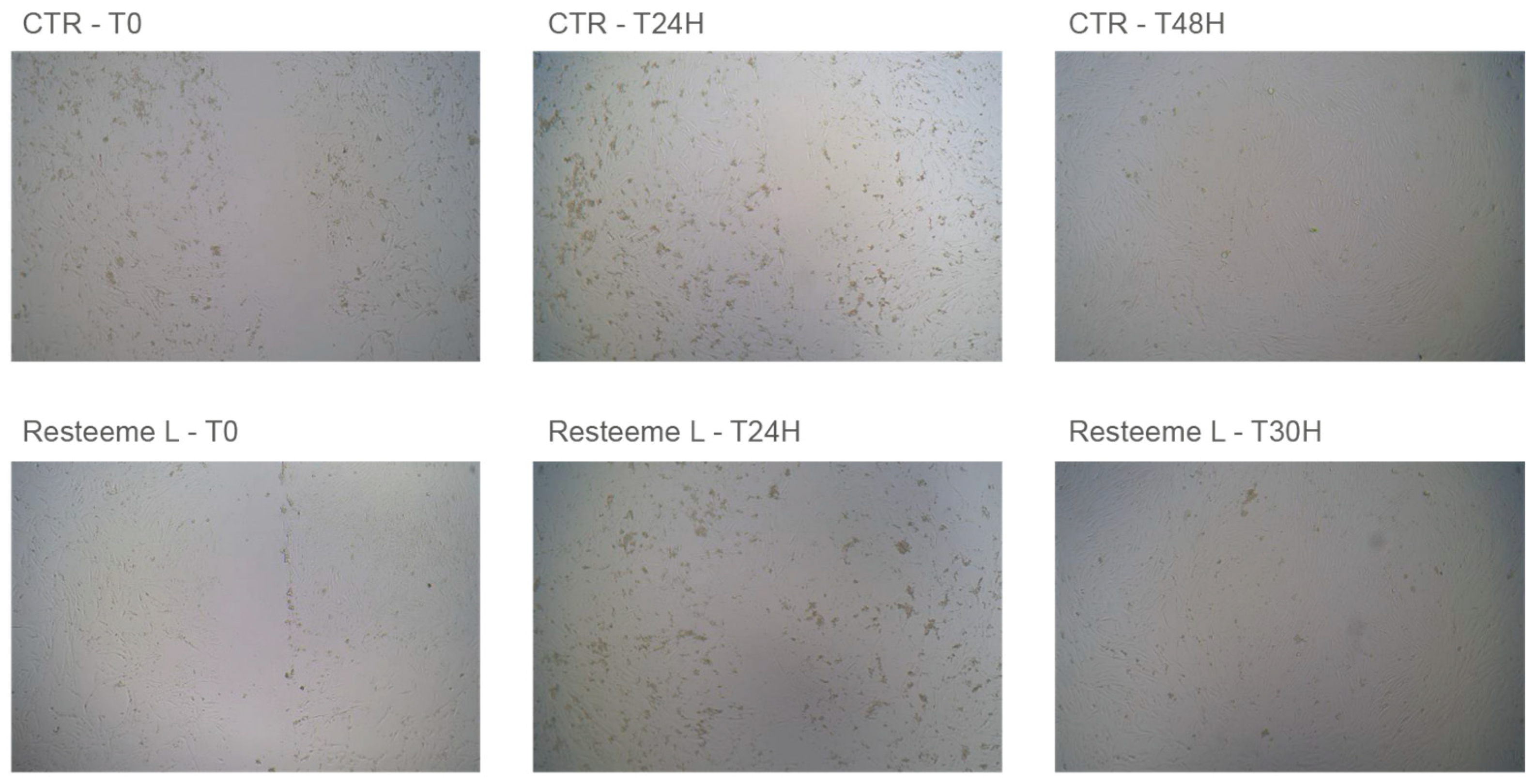

Application of the high-molecular-weight range hyaluronic acid formulation (Resteem L; hereafter referred to as the HMW-HA formulation) induced a faster and morphologically distinct repair response in keratinocyte monolayers.

Figure 4 presents representative micrographs of control (CTR−) and treated cultures at baseline (T0), 24 h, and 30 h, showing complete closure of the acellular gap in treated cultures.

During the first few hours, localized pericellular swelling was observed in treated wells, followed by compact, continuous monolayer formation and uniform cellular alignment.

At baseline (T0), the inter-edge distance averaged 691.4 ± 66.7 µm in controls.

After 2 h, distances were 685.9 ± 56.2 µm (−0.8%) in controls and 649.0 ± 38.9 µm (−0.9%), 653.9 ± 90.8 µm (−0.7%), and 661.7 ± 51.9 µm (−0.2%) for 0.25%, 0.1%, and 0.05% Resteem L, respectively.

After 8 h, controls measured 643.4 ± 31.4 µm (−6.9%), while treated cultures reached 515.9 ± 44.5 µm (−21.3%), 555.0 ± 49.6 µm (−15.8%), and 619.7 ± 77.6 µm (−6.5%), respectively.

After 24 h, controls were 556.3 ± 37.2 µm (−19.5%), compared with 407.8 ± 40.0 µm (−37.8%), 456.1 ± 35.7 µm (−30.8%), and 525.0 ± 18.0 µm (−20.8%) for the three concentrations (

Figure 5;

Table 3 and

Table 4).

No cytotoxic alterations or detachment were noted at any concentration. Complete gap closure was observed at approximately 30 h for all tested concentrations of Resteem L, earlier than observed for Resteem X. The exact time point between 24 h and 30 h was determined by visual inspection, as photographic documentation was performed at baseline, 2 h, 8 h, 24 h, and 30 h intervals. At higher concentrations, the pericellular edema observed initially was transient and corresponded with faster closure and increased cellular cohesion after 24 h.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates two principal findings regarding hyaluronic acid formulations in keratinocyte repair. First, the LMHMW-HA formulation with trehalose (Resteem X, 200–400 and 1200–1500 kDa) significantly accelerated gap closure compared to untreated controls, achieving 37.2% reduction in inter-edge distance at 24 h (p < 0.001) and complete closure at 48 h with visibly increased cellular density. Second, the HMW-HA formulation (Resteem L, 1800–2600 kDa) induced even faster initial closure, reaching 37.8% reduction at 24 h (p < 0.001) and complete closure at approximately 30 h, accompanied by transient pericellular swelling. These findings address a critical knowledge gap in understanding how commercially available HA formulations with different molecular weight profiles and compositions promote cellular repair through distinct patterns—LMHMW-HA associated with gradual closure and increased cellular density consistent with proliferation-driven repair, while HMW-HA induced rapid closure with transient pericellular swelling consistent with hydration-mediated effects—with implications for indication-specific selection in aesthetic and regenerative medicine.

The LMHMW-HA formulation with trehalose (Resteem X) promoted gradual gap closure over 48 h with visibly increased cellular density in the final monolayer. These observations suggest sustained cellular proliferation and migration throughout the observation period. This pattern differs markedly from passive wound contraction and suggests active cellular engagement in the repair process. The intermediate closure time (~48 h) and increased cell density are consistent with LMHMW-HA’s capacity to stimulate both migratory and proliferative programs in keratinocytes, as previously demonstrated in studies showing enhanced expression of matrix metalloproteinases and growth factors following LMHMW-HA exposure [

6,

28]. Unlike formulations that primarily induce mechanical edge approximation, Resteem X appears to promote biologically active repair characterized by cellular recruitment and matrix remodeling, supporting its potential application in scenarios requiring enhanced tissue regeneration rather than rapid closure alone.

In contrast to the gradual repair pattern observed with LMHMW-HA, the HMW-HA formulation (Resteem L) induced faster gap closure with complete coverage achieved at approximately 30 h. The observed transient pericellular swelling during early time points is consistent with the high water retention capacity of HMW-HA, which creates localized hydration that facilitates mechanical approximation of lesion edges [

12,

14]. This rapid edge contraction represents a distinct mechanism from the proliferation-driven closure observed with LMHMW-HA, suggesting that HMW-HA primarily functions through matrix-mediated physical effects rather than direct cellular activation [

9,

14]. The faster closure time and absence of prolonged inflammatory-like activation are consistent with HMW-HA’s role in stabilizing repair processes and creating conditions favorable for physiological tissue remodeling [

19,

26].

The observed effects align with established molecular weight-dependent patterns in keratinocyte repair. Kawano et al. demonstrated that HMW-HA (2290 kDa) promoted keratinocyte wound closure with sustained effects observable from 6 to 48 h [

6]. Our observation that HMW-HA (1800–2600 kDa) induced closure by approximately 30 h demonstrates a similar pattern of sustained closure, though the faster kinetics in our study may reflect differences in molecular weight range or experimental conditions. However, the transient pericellular swelling observed in our study suggests that closure mechanisms may vary with specific molecular weight ranges and formulation contexts. Similarly, Liu et al. showed that LMW-HA (~18 kDa) enhanced keratinocyte migration through HIF-1α/VEGF pathway activation [

18], supporting the interpretation that the LMHMW-HA formulation (200–400 and 1200–1500 kDa) promotes biologically active repair involving cellular proliferation and migration. The inclusion of trehalose in the LMHMW-HA formulation may provide additional metabolic protection that sustains these repair processes under conditions of cellular stress.

The inclusion of trehalose in the LMHMW-HA formulation likely contributed to the observed repair-promoting effects by providing metabolic protection during the cellular stress associated with injury and repair. The combination of trehalose with low and medium-high molecular-weight range HA may enhance both the biological (migration, proliferation) components of keratinocyte repair while protecting cells from oxidative and glycation-related damage [

19,

25,

26,

27]. In contrast, the HMW-HA formulation without trehalose demonstrated effective repair promotion primarily through matrix-mediated physical effects, suggesting that high-molecular-weight HA alone is sufficient to induce rapid hydration-mediated closure. The complementary nature of these mechanisms—LMHMW-HA with trehalose providing biologically active repair and metabolic protection, versus HMW-HA providing structural stabilization—is consistent with recent findings demonstrating that different molecular weight HA formulations can address distinct phases of tissue repair [

13,

14,

28].

An important consideration in interpreting these findings is that the two formulations were evaluated in separate experimental series using different concentration ranges (0.5–0.1% for Resteem X vs. 0.25–0.05% for Resteem L), reflecting empirically determined optimal non-cytotoxic doses for each molecular weight range. Consequently, direct quantitative comparison of efficacy between formulations was not the primary goal of this study; rather, the aim was to characterize the distinct mechanisms by which each formulation promotes cellular repair. Additionally, since Resteem X contains trehalose while Resteem L does not, the observed mechanistic differences may reflect both molecular weight effects and the bioprotective contribution of trehalose. A critical limitation of this study is that the mechanistic interpretation is based on morphological and kinetic observations from a scratch assay model, without direct molecular characterization of the underlying cellular pathways. While the observed patterns—increased cellular density with LMHMW-HA versus transient pericellular swelling with HMW-HA—are consistent with proliferation-driven and hydration-mediated mechanisms, respectively, definitive mechanistic conclusions would require additional experiments including proliferation assays (e.g., Ki-67 immunostaining, BrdU incorporation), migration-specific assays, analysis of matrix metalloproteinase expression and extracellular matrix remodeling, and evaluation of receptor engagement and signaling pathways. The present study therefore provides a preliminary characterization that establishes a foundation for future mechanistic investigations. The observed differences—gradual closure with increased cellular density for LMHMW-HA versus rapid edge contraction with transient pericellular swelling for HMW-HA—suggest complementary rather than competing mechanisms. This interpretation aligns with recent findings demonstrating that combined molecular weight HA formulations can address multiple phases of tissue repair sequentially: LMW-HA fragments initiate controlled inflammatory activation and cellular recruitment during early repair phases, while HMW-HA subsequently stabilizes the matrix and suppresses excessive inflammation during remodeling phases [

13,

14,

28]. The complementary nature of these mechanisms has been previously demonstrated in ex vivo human skin models, where dual molecular weight HA formulations combined with trehalose exhibited superior anti-glycation protection and enhanced barrier function compared to single molecular weight preparations [

26,

27].

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this study employed a monolayer scratch assay, which models cellular repair mechanisms in a simplified two-dimensional system lacking the complexity of three-dimensional tissue architecture, dermal-epidermal interactions, immune cell participation, and vascularization present in physiological wound healing. Therefore, while the observed effects demonstrate cellular repair capacity in keratinocytes, extrapolation to in vivo wound healing must be made cautiously. Second, the absence of direct side-by-side comparison at identical concentrations limits conclusions regarding relative potency. Third, the study focused exclusively on keratinocyte responses without evaluating potential effects on fibroblasts, endothelial cells, or immune cells that contribute to tissue repair in vivo. Despite these limitations, the in vitro model provides valuable mechanistic insights into molecular weight-dependent effects of HA formulations on keratinocyte behavior, which may inform rational design of therapeutic approaches in aesthetic and regenerative medicine.

These findings may have practical implications for aesthetic and regenerative medicine. The LMHMW-HA formulation with trehalose, which promotes sustained cellular proliferation and migration, may be particularly suitable for: biorevitalization procedures aimed at improving dermal cellular density and extracellular matrix quality; post-procedural healing support following ablative or non-ablative laser treatments, where cellular recruitment and tissue regeneration are required; and management of atrophic scars or photoaged skin, where stimulation of fibroblast activity and matrix remodeling are therapeutic goals. In contrast, the HMW-HA formulation, which induces rapid hydration-mediated tissue stabilization, may be advantageous for: immediate structural support in dermal filling applications; rapid restoration of skin barrier function following superficial injury or inflammation; and maintenance of tissue hydration in scenarios where anti-inflammatory effects and matrix stabilization are prioritized over cellular activation.

The distinct kinetic and morphological profiles of LMHMW-HA versus HMW-HA formulations suggest potential for indication-specific selection: formulations promoting sustained cellular proliferation and migration (LMHMW-HA) may be preferable in scenarios requiring tissue regeneration and cellular recruitment, while formulations inducing rapid matrix stabilization and hydration-mediated closure (HMW-HA) may be advantageous when immediate structural support is needed. The complementary nature of these mechanisms also supports rationale for dual molecular weight formulations that sequentially address multiple repair phases, as demonstrated in recent ex vivo studies showing enhanced outcomes with combined molecular weight approaches [

26,

27]. Future investigations should employ three-dimensional skin models and in vivo wound healing assays to validate these in vitro observations under physiological conditions, including evaluation of dermal-epidermal interactions, angiogenesis, and immune responses. Additionally, comparative studies using matched concentrations would enable direct assessment of relative efficacy. Understanding the molecular weight-dependent effects of HA formulations combined with bioprotective agents such as trehalose may facilitate development of next-generation biostimulatory products optimized for specific clinical indications in tissue repair and aesthetic medicine. Future studies should also investigate whether addition of trehalose to HMW-HA formulations would modulate the hydration-mediated closure mechanism or provide complementary metabolic protection during tissue stabilization phases.

While this study was conducted using an in vitro keratinocyte monolayer model to investigate cellular repair mechanisms, the observed molecular weight-dependent effects of HA formulations may have hypothetical implications for in vivo wound healing processes. The distinct repair patterns—gradual cellular proliferation and migration with LMHMW-HA versus rapid hydration-mediated edge approximation with HMW-HA—could potentially correspond to different functional requirements across wound healing phases, where early inflammatory activation and subsequent matrix stabilization are both necessary for successful tissue restoration. However, it must be emphasized that the present study does not directly demonstrate wound healing efficacy, and extrapolation from this in vitro cellular repair model to complex in vivo wound healing requires caution. Future studies employing three-dimensional tissue models and in vivo wound healing assays would be necessary to validate whether the cellular mechanisms identified here translate to enhanced clinical wound healing outcomes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cellular Procedures and Study Methodology

The study was conducted in an in vitro cellular repair model using Normal Human Epidermal Keratinocytes (NHEK), which are primary cells from adult donors. All experiments were performed at Complife Italia S. r. l. (San Martino Siccomario, Italy) under standardized laboratory conditions. The objective was to evaluate the ability of two hyaluronic acid-based formulations to promote cellular repair processes.

Two separate experiments were carried out independently:

- (1)

Resteem X—a formulation containing low- and medium-high-molecular-weight range hyaluronic acid (200–400 and 1200–1500 kDa) combined with trehalose;

- (2)

Resteem L—a formulation containing high-molecular-weight range hyaluronic acid (1800–2600 kDa).

Each test was performed in triplicate and included untreated control cultures (CTR−). All quantitative measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3) for each experimental condition, ensuring reproducibility and statistical validity.

Human keratinocytes were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 until full confluence was reached. After achieving confluence, an artificial linear lesion was mechanically introduced into the monolayer to simulate a controlled cellular injury (cell repair model). The formulations were applied immediately after injury, and cellular responses were monitored over 48 h.

4.2. Preparation of Hyaluronic Acid Formulations

The tested formulations were supplied by URGO Sp. z o.o. (Warsaw, Poland) as sterile, ready-to-use medical devices designed for intradermal injection in aesthetic medicine.

Resteem X contained a combination of low- and medium-high-molecular-weight range hyaluronic acid at a total concentration of 25 mg/mL, with a weight ratio of 20:80 between the low-molecular-weight fraction (200–400 kDa) and the medium-high-molecular-weight fraction (1200–1500 kDa). Trehalose was present at a concentration of 1% (w/v, equivalent to 10 mg/mL). The complete composition included: sodium hyaluronate (1200–1500 kDa and 200–400 kDa), trehalose, sodium chloride, sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate, dibasic sodium phosphate dodecahydrate, and water for injection.

Resteem L contained high-molecular-weight range hyaluronic acid at a total concentration of 20 mg/mL. The complete composition included: sodium hyaluronate (1800–2600 kDa), sodium chloride, sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate, dibasic sodium phosphate dodecahydrate, dodecahydrate, and water for injection.

For in vitro testing, both formulations were diluted in cell-culture medium to obtain final concentrations established as non-cytotoxic in preliminary assays. For Resteem X, concentrations of 0.5%, 0.25% and 0.1% were used, corresponding to final hyaluronic acid concentrations of 125 µg/mL, 62.5 µg/mL, and 25 µg/mL, respectively. For Resteem L, concentrations of 0.25%, 0.1% and 0.05% were tested, corresponding to final hyaluronic acid concentrations of 50 µg/mL, 20 µg/mL, and 10 µg/mL, respectively. The concentration ranges for each formulation were determined empirically through preliminary cytotoxicity screening, starting from 10% and performing serial 1:2 dilutions until non-cytotoxic concentrations were identified. The different concentration ranges between Resteem X and Resteem L reflect the distinct tolerability profiles of low- and medium-high ranges versus high range molecular weight hyaluronic acid in keratinocyte cultures, with higher concentrations of HMW-HA requiring lower dilutions to maintain cell viability. This approach ensured that each formulation was tested at its optimal non-cytotoxic range, allowing for accurate assessment of repair-promoting activity without confounding cytotoxic effects.

4.3. Cytotoxicity Assessment (MTT Assay)

A preliminary cytotoxicity evaluation was performed to determine non-toxic concentration ranges suitable for subsequent efficacy testing. The MTT assay (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was used following standard ISO 10993-5 guidelines [

29].

Keratinocytes underwent exposure to serial dilutions of each formulation for 24 h. Following incubation, cells underwent washing with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS, pH 7.1–7.7) followed by incubation with 1 mg/mL MTT solution for 3 h at 37 °C, and the produced formazan crystals were solubilized in isopropanol. The absorbance was quantified at 540 nm utilizing a microplate reader, and cell viability was presented as a percentage relative to untreated control groups.

4.4. Induction of Controlled Cellular Injury (Cell Repair Model)

Following cytotoxicity testing, confluent keratinocyte monolayers were scratched using a sterile pipette tip to create a defined acellular gap representing a mechanical injury. Immediately after wounding, culture media containing each formulation at the selected concentrations were added. Untreated wells served as negative controls.

Cellular repair dynamics were observed at baseline (T0), 2 h (T2 h), 8 h (T8 h), and 24 h (T24 h) post-injury. Additional monitoring continued up to 48 h to document complete closure of the cellular gap. Each condition was performed in triplicate.

4.5. Imaging and Quantitative Analysis

At each observation point, cultures were examined using an optical microscope (Nexcope NIB620, Ningbo, China) equipped with a MIChrome camera (Tucsen, Fuzhou, China). Micrographs were captured at 4× magnification. The inter-edge distances were quantified by measuring the inter-edge distance at three equidistant points along the scratch using ImageJ software (version 1.53, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA). For each replicate, three measurements were taken at distinct locations along the lesion to ensure representative sampling of the entire wound area. Mean values ± standard deviation were determined for every time interval and formulation concentration.

The progression of cellular repair was expressed as the percentage reduction in inter-edge distance relative to baseline (T0). Representative images illustrating the morphological changes during repair were obtained for each experimental condition.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) derived from three separate experiments (n = 3). Differences between the treated cultures and untreated controls were evaluated at corresponding time points using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Furthermore, differences between the initial baseline (T0) and later time points within each experimental group were assessed using the paired t-test. Significance was established at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were executed utilizing Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) employing the software’s inherent statistical functions.

4.7. Ethical Statement

This study did not involve human participants or animal subjects. Normal Human Epidermal Keratinocytes (NHEK) used in this research were commercially obtained primary cells from certified biological material suppliers. According to European Union Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and international guidelines for in vitro research, the use of commercially available de-identified primary cell cultures does not require additional ethical approval. All experimental procedures were conducted exclusively on in vitro cell cultures at Complife Italia S. r. l. (San Martino Siccomario, Italy) in accordance with Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) guidelines. No personal or identifiable human data were collected or processed in this study.