Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal Physiological and Hepatic Metabolic Responses of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) to Subacute Saline–Alkaline Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

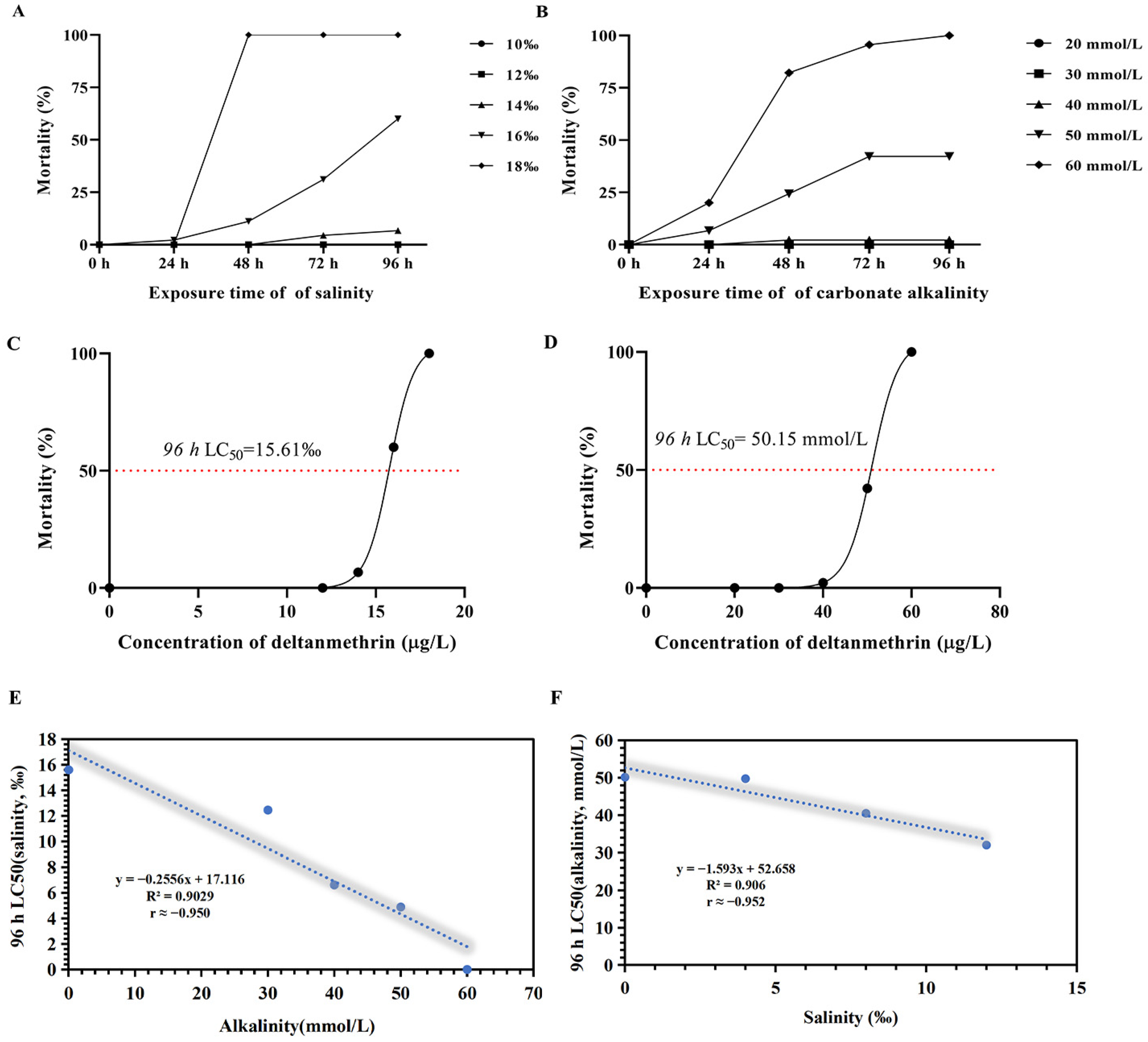

2.1. Median Lethal Concentration (96 h LC50) for Salinity and Alkalinity

2.2. Effects of Salinity and Alkalinity Treatment on Growth Efficiency

2.3. Tissue Section Observation

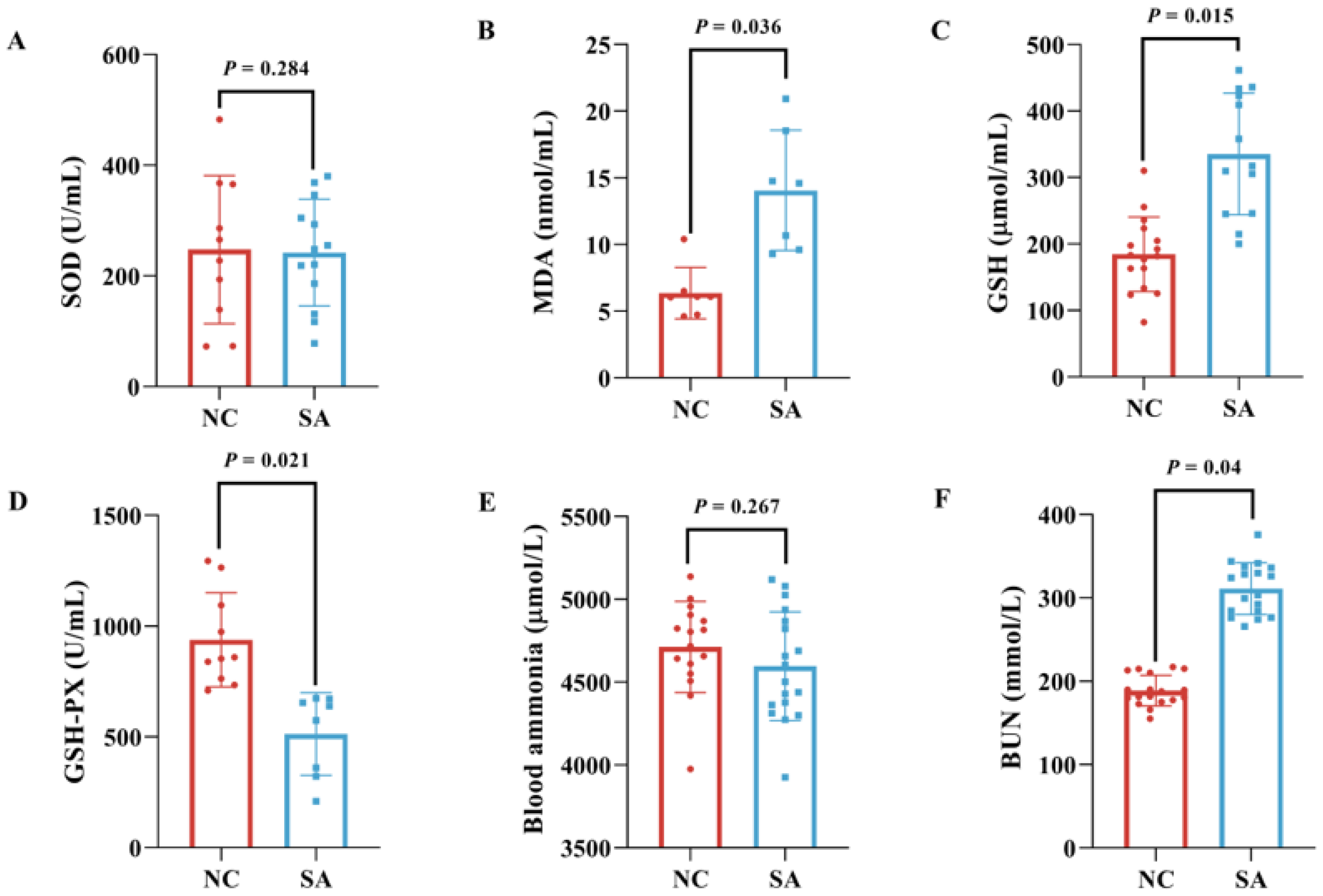

2.4. Analysis of Serum Physiological Parameters

2.5. Transcriptomic Analysis

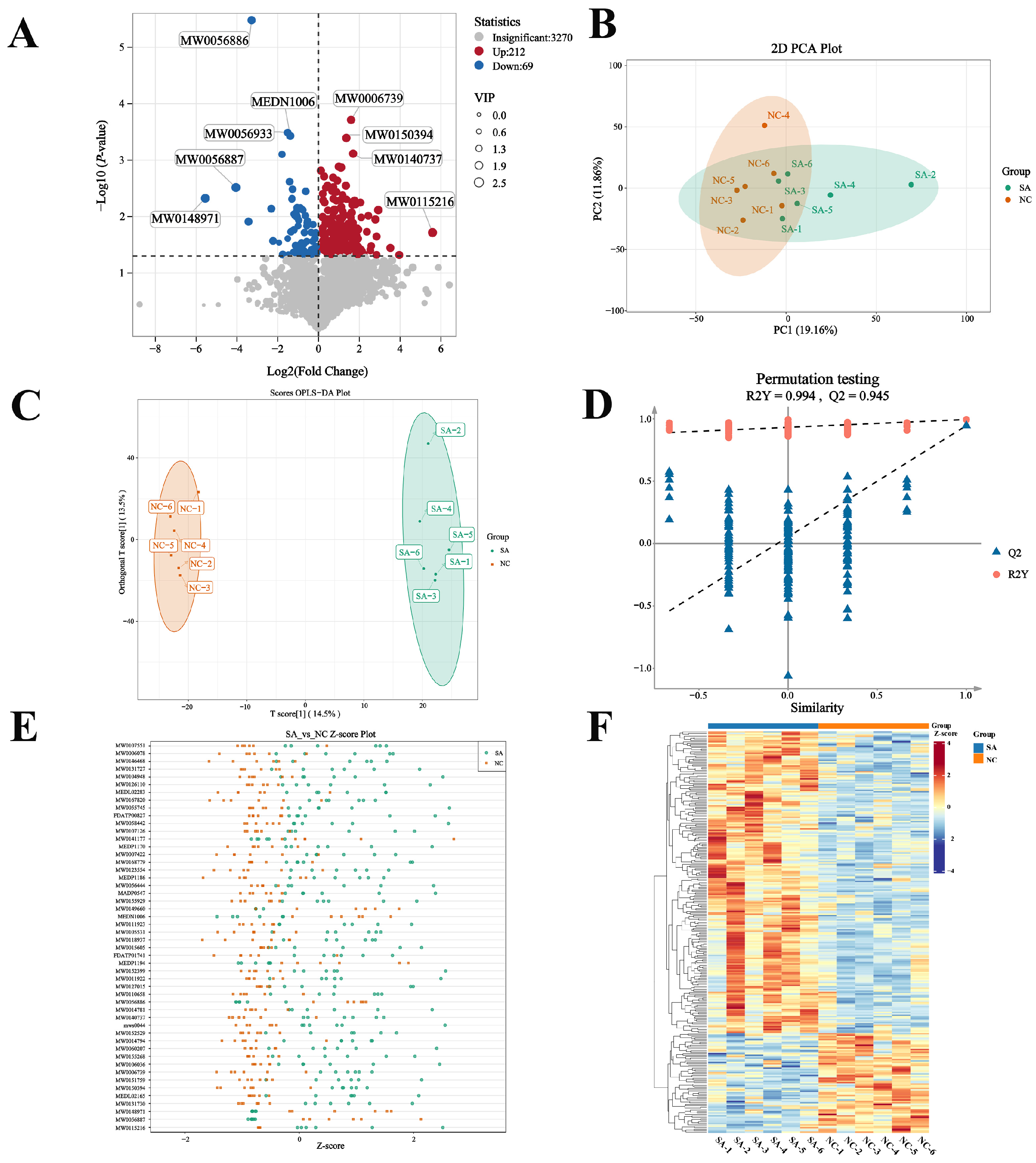

2.6. Metabolomic Analysis

2.6.1. Principal Component and Clustering in DMs

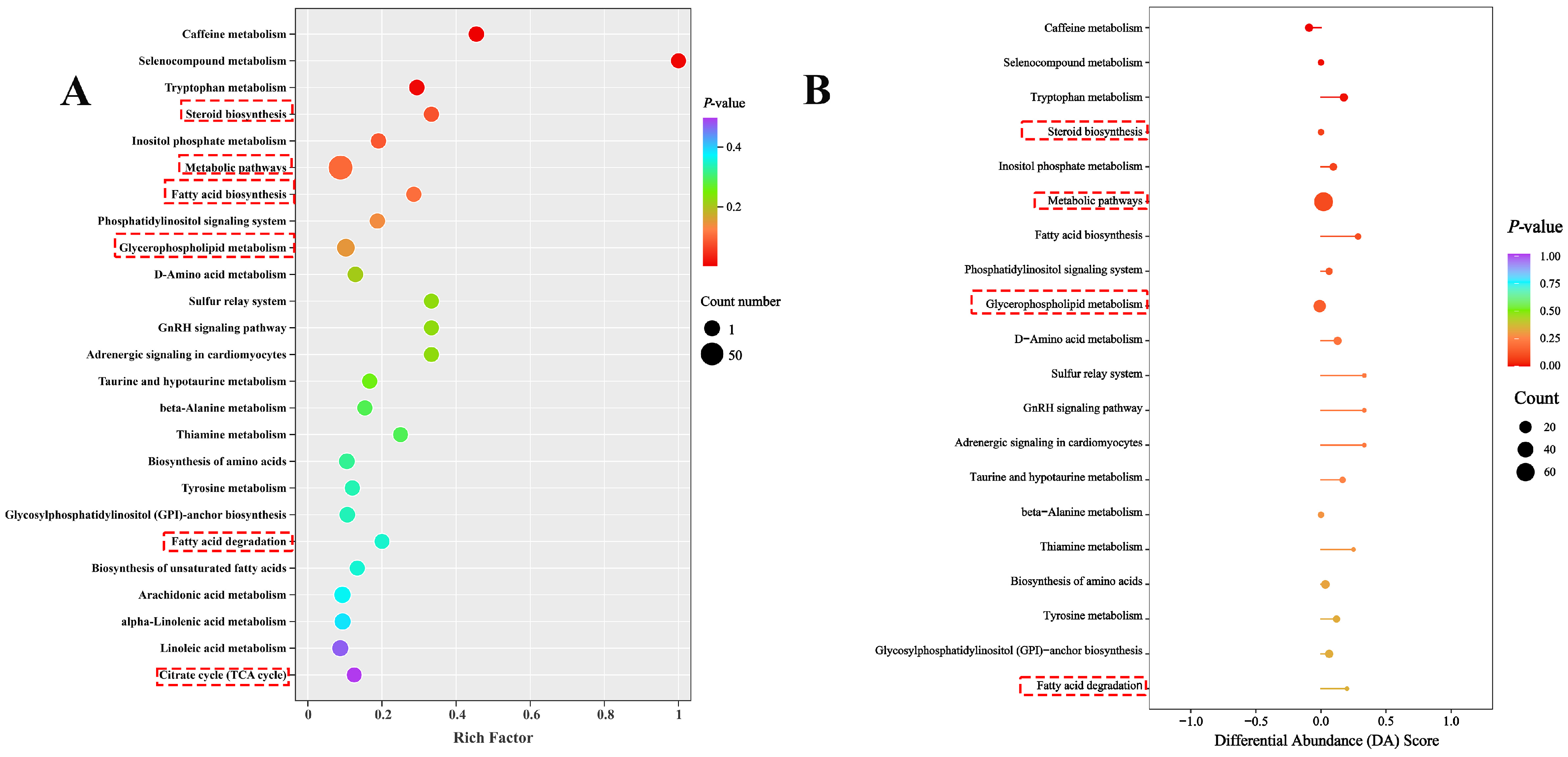

2.6.2. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DMs

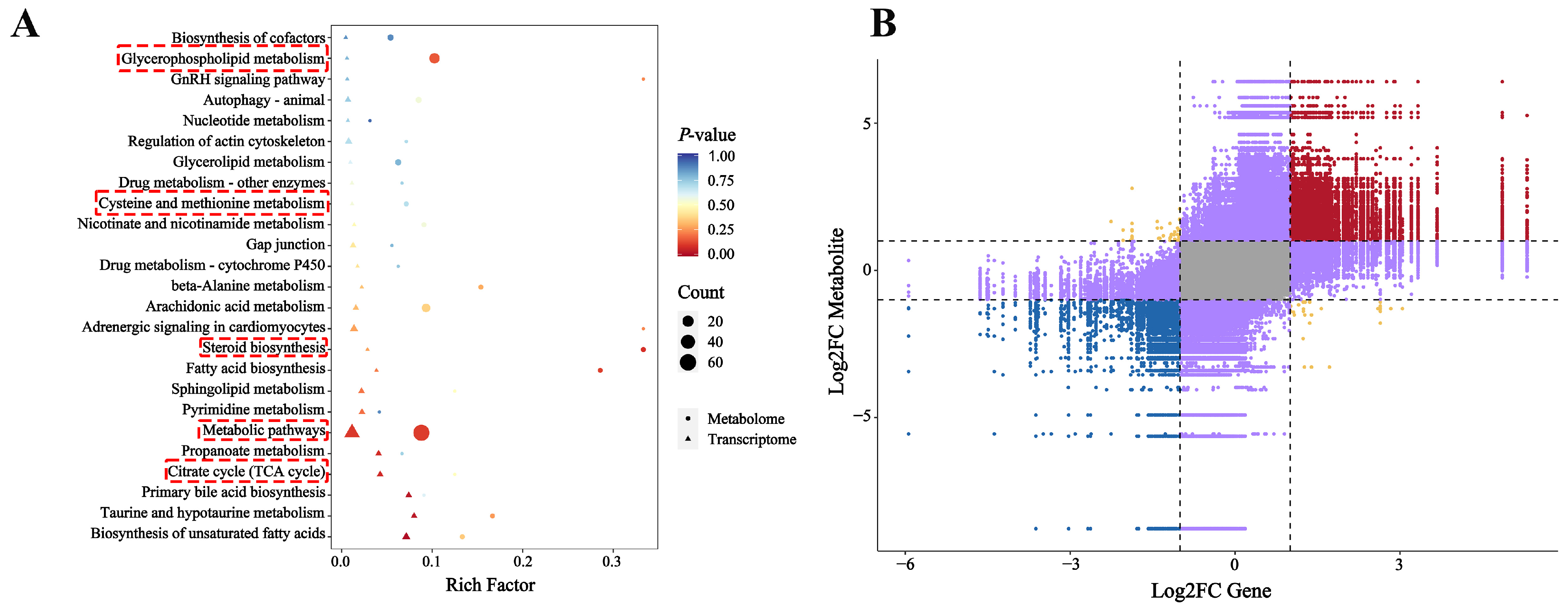

2.7. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptomics and Metabolomics

2.7.1. KEGG Enrichment and Expression Trend Analysis

2.7.2. Correlation Analysis of DEGs and DMs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

4.1.1. Experimental Condition

4.1.2. Acute Stress Experiment

4.1.3. Subacute Saline–Alkaline Stress Experiment

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. Histological Processing

4.3.1. HE-Staining Observation

4.3.2. TUNEL Detection

4.4. Serum Enzyme Activity

4.5. Transcriptomics

4.5.1. Transcriptome Sequencing of Largemouth Bass Liver Samples

4.5.2. Data Analysis

4.5.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.6. Metabolomic

4.6.1. Sample Processing

4.6.2. LC-MS Conditions

4.6.3. Data Processing and Analysis

4.7. Integrated Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis

4.8. Statistics and Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hua, J.X.; Tao, Y.F.; Lu, S.Q.; Li, Y.; Dong, Y.L.; Jiang, B.J.; Xi, B.W.; Qiang, J. Integration of transcriptome, histopathology, and physiological indicators reveals regulatory mechanisms of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) in response to carbonate alkalinity stress. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.L.; Lai, Q.F.; Zhou, K.; Rizalita, R.E.; Wang, H. Developmental biology of medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) exposed to alkalinity stress. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 26, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, H.; Liu, Y.; Qi, X.; Sun, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Gill histological and transcriptomic analysis provides insights into the response of spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus) to alkalinity stress. Aquaculture 2023, 563, 738945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrasek, G.; Rengel, Z. Environmental salinization processes: Detection, implications & solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, S.F.; Gilmour, K.M. Acid-base balance and CO2 excretion in fish: Unanswered questions and emerging models. Respirat Physiol. Neurobiol. 2006, 154, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.S.; Yao, T.H.; Zhang, T.X.; Sun, M.Y.; Ning, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Mu, W.J. Effects of chronic saline-alkaline stress on gill, liver and intestinal histology, biochemical, and immune indexes in Amur minnow (Phoxinus lagowskii). Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Shen, Y.D.; Bao, Y.G.; Wu, Z.X.; Yang, B.Q.; Jiao, L.F.; Zhang, C.D.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q.C.; Zhou, Q.C.; et al. Physiological responses and adaptive strategies to acute low-salinity environmental stress of the euryhaline marine fish black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii). Aquaculture 2022, 554, 738117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, F.Y.; Yan, Z.H.; Guo, Z.Y.; Lu, Y.Q.; Yao, B.L.; Li, Y.H.; Lv, W.F. Effects of prolonged NaHCO3 exposure on the serum immune function, antioxidant capacity, intestinal tight junctions, microbiota, mitochondria, and autophagy in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Yao, M.Z.; Li, S.W.; Wei, X.F.; Ding, L.; Han, S.C.; Wang, P.; Lv, B.C.; Chen, Z.X.; Sun, Y.C. Integrated application of multi-omics approach and biochemical assays provides insights into physiological responses to saline-alkaline stress in the gills of crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.P.; Saqib, H.S.A.; Lin, Z.Y.; Zheng, R.P.; Qiu, Y.T.; Xie, Y.T.; Ma, D.N.; Shen, Y.J. RNA-seq analyses of Marine Medaka (Oryzias melastigma) reveals salinity responsive transcriptomes in the gills and livers. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 240, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linlin, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Liang, J.; Zhou, W.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, H. Comprehensive analyses of annexins in naked carp (Gymnocypris przewalskii) unveil their roles in saline-alkaline stress. Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, P.C.; Zhou, K.; Yao, Z.L.; Sun, Z.; Qin, H.C.; Lai, Q.F. Effects of saline and alkaline stresses on the survival, growth, and physiological responses in juvenile mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Aquaculture 2024, 591, 741143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.X.; Song, H.R.; Song, H.M.; Zhu, T.; Du, J.X.; Li, S.J. RNA-seq and whole-genome re-sequencing reveal Micropterus salmoides growth-linked gene and selection signatures under carbohydrate-rich diet and varying temperature. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.C.; Han, S.C.; Yao, M.Z.; Liu, H.B.; Wang, Y.M. Exploring the metabolic biomarkers and pathway changes in crucian under carbonate alkalinity exposure using high-throughput metabolomics analysis based on UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 1552–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Fan, Z.; Li, J.; Tang, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X. Comprehensive assessment of detoxification mechanisms of hydrolysis fish peptides in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) under copper exposure: Tracing from bioaccumulation, oxidative stress, lipid deposition to metabolomics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Huang, W.Q.; Wang, S.; Shan, X.J.; Ji, C.L.; Wu, H.F. Liver transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular responses to low-salinity in large yellow croaker Larimichthys crocea. Aquaculture 2020, 517, 734827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.R.; Zhang, F.; Li, R.N.; Li, E.C.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L.Q.; Wang, X.D. Growth performance, antioxidant capacity, intestinal microbiota, and metabolomics analysis of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under carbonate alkalinity stress. Aquaculture 2025, 595, 741675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Huang, Y.; Hong, Y.H.; Xu, D.Y.; Jiang, C.W.; Huang, Z.Q. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms of nitrite-induced physiological disruptions in largemouth bass. Aquaculture 2024, 580, 740320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Yu, H.R.; Chen, H.P.; Wang, X.X.; Tan, Y.F.; Sun, J.L.; Luo, J.; Song, F.B. Integrative transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal preliminary molecular mechanisms of gills response to salinity stress in Micropterus salmoides. Aquaculture 2025, 606, 742600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.C.; Geng, L.W.; Wei, H.J.; Liu, T.Q.; Che, X.H.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.H.; Shi, X.D.; Li, J.H.; Teng, X.H.; et al. Analysis revealed the molecular mechanism of oxidative stress-autophagy-induced liver injury caused by high alkalinity: Integrated whole hepatic transcriptome and metabolome. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1431224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Pu, D.C.; Zheng, J.S.; Li, P.Y.; Lü, H.J.; Wei, X.L.; Li, M.; Li, D.S.; Gao, L.H. Hypoxia-induced physiological responses in fish: From organism to tissue to molecular levels. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 267, 115609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Wang, G.X.; Zheng, X.Y.; Zheng, X.Y.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, Y.C.; Ren, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.T.; Liu, Y.F.; He, Z.W.; et al. Exposure to deltamethrin leads to gill liver damage, oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic disorders of Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Front. Toxicol. 2025, 16, 1560192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.Y.; Wang, F.; Song, J.L.; Li, F.X.; Wang, J.W.; Jia, Y.D. Sexual dimorphism in physiological responses of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus L.) under acute hypoxia and reoxygenation. Aquaculture 2024, 595, 741614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.X.; Deng, C.Y.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, H.P.; Yu, H.R.; Sun, S.K.; Sun, J.L.; Luo, J.; Song, F.B. Transcriptome analysis revealed that largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) may mobilize liver lipid metabolism to provide energy for adaptation to hypertonic stress. Aquaculture 2025, 607, 742646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, K.; Li, K.Z.; Olmos-Alonso, A.; Garcia-Moreno, F.; Liang, Y.J.; Richardson, P.; Tipton, T.; Chapman, M.A.; Riecken, K.; Beccari, S.; et al. Coupled proliferation and apoptosis maintain the rapid turnover of microglia in the adult brain. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.X.; Miao, J.J.; Tian, Y.M.; Pan, L.Q. Effects of benzo[a]pyrene exposure on oxidative stress and apoptosis of gill cells of Chlamys farreri in vitro. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 93, 103867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.H.; Zhang, L.P.; Li, Z.G.; Wei, A.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ma, H.H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.X.; Zhao, Y.Z.; et al. Associations between PRF1 Ala91Val polymorphism and risk of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A meta-analysis based on 1366 subjects. World J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttini, S.; Cappellano, G.; Ripellino, P.; Briani, C.; Cocito, D.; Osio, M.; Cantello, R.; Dianzani, U.; Comi, C. Variations of the perforin gene in patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Genes Immun. 2015, 16, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Tseng, L.C.; Chou, C.; Wang, L.; Souissi, S.; Hwang, J.S. Effects of cadmium exposure on antioxidant enzymes and histological changes in the mud shrimp Austinogebia edulis (Crustacea: Decapoda). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7752–7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Cárdenas, P.; Cruz-Moreno, D.G.; González-Ruiz, R.; Peregrino-Uriarte, A.B.; Leyva-Carrillo, L.; Camacho-Jiménez, L.; Quintero-Reyes, I.; Yepiz-Plascencia, G. Combined hypoxia and high temperature affect differentially the response of antioxidant enzymes, glutathione and hydrogen peroxide in the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A 2021, 254, 110909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeon, H.; Bai, S.C.; Hur, J.W.; Han, H. Effects of dietary supplementation with Arthrobacter bussei powder on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, and innate immunity of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 25, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, M.; Wang, Y.Q.; Xu, L.P. Andrographolide Derivative AL-1 Ameliorates Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Murine Colitis by Inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6138723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Rana, T.; Alotaibi, G.H.; Shamsuzzaman, M.; Naqvi, M.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; Almoshari, Y.; Abdellatif, A.A.H.; et al. Polyphenols inhibiting MAPK signalling pathway mediated oxidative stress and inflammation in depression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Huang, Z.Y.; Zhang, X.; Rao, Z.M.; Xu, M.J. The maintenance of redox homeostasis to regulate efficient glutathione metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Shi, X.; Guo, J.T.; Mao, X.; Fan, B.Y. Acute stress response in gill of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei to high alkalinity. Aquaculture 2024, 586, 740766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacila, I.A.; Elder, C.; Krone, N. Update on adrenal steroid hormone biosynthesis and clinical implications. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budin, I.; Szostak, J.W. Physical effects underlying the transition from primitive to modern cell membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5249–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.; Stovall, K.; Monian, P.; Franklin, J.L.; Cummings, B.S. Alterations in phos-pholipid and fatty acid lipid profiles in primary neocortical cells during oxidant-induced cell injury. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008, 174, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Y.; Zou, X.J.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y.R.; Li, Y.H.; Zhang, L.Q.; Huang, J.F.; Liang, B. The Evolutionary Pattern and the Regulation of Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase Genes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2023, 856521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crovetto, C.A.; Córdoba, O.L. Structural and biochemical characterization and evolutionary relationships of the fatty acid-binding protein 10 (Fabp10) of hake (Merluccius hubbsi). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 42, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouilloz, A.; Bourgeois, T.; Diedisheim, M.; Pilot, T.; Jalil, A.; Le Guern, N.; Bergas, V.; Rohmer, N.; Castelli, F.; Leleu, D.; et al. Impaired unsaturated fatty acid elongation alters mitochondrial function and accelerates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis progression. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2025, 162, 156051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Li, H.Y.; Dong, H.; Wang, P.P.; Li, Y.T.; Wu, K.G. Effect of cinnamon essential oil dietary supplementation on the growth, fatty acid composition, and meat quality of tilapia. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 5266–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Song, Z.; Qiang, J.; Tao, Y.F.; Zhu, H.J.; Ma, J.L.; Xu, P. Transport Stress Induces Skin Innate Immunity Response in Hybrid Yellow Catfish (Tachysurus fulvidraco♀ × P. vachellii♂) Through TLR/NLR Signaling Pathways and Regulation of Mucus Secretion. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 740359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, J.; Tao, Y.F.; Zhu, J.H.; Lu, S.Q.; Cao, Z.M.; Ma, J.L.; He, J.; Xu, P. Effects of heat stress on follicular development and atresia in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) during one reproductive cycle and its potential regulation byautophagy and apoptosis. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkhomchuk, D.; Borodina, T.; Amstislavskiy, V.; Banaru, M.; Hallen, L.; Krobitsch, S.; Lehrach, H.; Soldatov, A. Transcriptome analysis by strand-specific sequencing of complementary DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.W.; Bao, B.L.; Xie, Z.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Li, B.; Jia, X.D.; Yao, Q.L.; Ortí, G.; Li, W.H.; Li, X.H.; et al. The genome and transcriptome of Japanese flounder provide insights into flatfish asymmetry. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Li, S.L.; Liu, Y.J.; Han, Z.H.; Chen, N.S. The inclusion of fenugreek seed extract aggravated hepatic glycogen accumulation through reducing the expression of genes involved in insulin pathway and glycolysis in largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.C.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.Y.; He, Q.Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. Omics 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆CT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.G. Complex heatmap visualization. iMeta 2022, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunning, M.J.; Smith, M.L.; Ritchie, M.E.; Tavaré, S. Beadarray: R classes and methods for Illumina bead-based data. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 2183–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Project | Groups | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NC | SA | ||

| WGR (%) | 131.45 ± 8.277 | 105.29 ± 19.271 | 0.109 |

| SGR (%/d) | 1.50 ± 0.065 | 1.27 ± 0.161 | 0.098 |

| SR (%) | 88.89 ± 1.283 | 81.19 ± 1.960 | 0.442 |

| Primers | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| scd | TGACCTGTACGCCGACAAAG | ATGAAGTACGCCACCCACAG |

| fabp10a | CAGGGCCATGGGAATGAACA | CTTTCCAGGGGTCTTGGAGG |

| elovl5 | CCCTGTGGCCATTCGTACTT | TCTTCCACCAAAGGTACGGC |

| bmp3 | AAGCCCTCTAACCATGCCAC | ACCACGTTCTTGTCCTCGTC |

| agap2 | TGCTACTGATCCGGGAGGAA | TAAAGCTCCTGGAAGCTGGC |

| epha2a | TCGCCGTAGCGATTAAGACC | TGGCGTGCTTGAATTTGGTG |

| dhrs11a | TGCTCAGCGGAAAGACAGAG | AGTGGCGCAGTAGAAATGCT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, B.; Liu, M.; Wan, H.; Han, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Cao, W.; San, L.; Yang, Y.; Ren, Y.; et al. Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal Physiological and Hepatic Metabolic Responses of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) to Subacute Saline–Alkaline Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412091

Li B, Liu M, Wan H, Han Z, Zhang H, Wang G, Cao W, San L, Yang Y, Ren Y, et al. Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal Physiological and Hepatic Metabolic Responses of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) to Subacute Saline–Alkaline Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412091

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Bingbu, Mingyang Liu, Hailong Wan, Zengsheng Han, Heng Zhang, Guixing Wang, Wei Cao, Lize San, Yucong Yang, Yuqin Ren, and et al. 2025. "Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal Physiological and Hepatic Metabolic Responses of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) to Subacute Saline–Alkaline Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412091

APA StyleLi, B., Liu, M., Wan, H., Han, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, G., Cao, W., San, L., Yang, Y., Ren, Y., & Hou, J. (2025). Integrated Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses Reveal Physiological and Hepatic Metabolic Responses of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) to Subacute Saline–Alkaline Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412091